Archive

Paul Johnsgard: A birder’s road less traveled

Paul Johnsgard is an unassuming Great Plains genius whose writing, lecturing, illustrating and photographing of birds and the natural world have earned him and his work high distinction. He is also renowned for his wood carvings of waterfowl. His impressive skill set has resulted in him being called a Renaissance Man by some and a rare bird or a bird of a different feather by others. The best way I found into his story was to frame his deep passion for nature as an extension of the imprinting process that goes on with birds. Everything about where he grew up and how he grew up immersed him in nature and reinforced his fascination with birds and wild things until it became embedded or imprinted in him. He is one of the latest in that ever growing gallery of my profile subjects whose life and work epitomize what I highlight in my writing – “stories about people, their passions and their magnificent obsessions.” Johnsgard’s regard for birds and the lengths he goes to observe, study, describe, illustrate, photograph than and to represent them in art are all about passion and magnificent obsession.

My profile of Johnsgard is the cover story in the July 2016 New Horizons that should be hitting stands and arrving in mailboxes by the end of June.

As an aside, whenever I do one of my new Horizons profiles I am reminded that the people of a certain age I profile in its pages are consistently the most complex, interesting subjects I write about. These people live rich, full lives marked by intellectual rigor, unbound curiosity, joyful work and play and a sense of adventure. They know themselves well enough by age 60 or 70 or 80 or 90 or whenever I get around to them to be comfortable in their own skin and to not much give a damn what anyone else thinks. They are well past pretense and posturing. They are al about living. They own every inch of their humanity, gifts and warts and all. It’s a refreshing and instructive lesson to live large and love hard.

Paul Johnsgard: A birder’s road less traveled

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the July 2016 issue of New Horizons

A birder’s beginnings

World-renowned ornithologist Paul Johnsgard, 85, ascribes his passion for birds to something akin to the imprinting process that occurs with the winged creatures he’s made his life’s work.

For the University of Nebraska-Lincoln emeritus professor and author of 82 books, many illustrated with his own drawings and photos, this road-less-traveled life all began as a lad in North Dakota. His earliest memories are of birds and other natural things that captured his imagination while growing up on the edge of prairie country.

“The railroad track went through town and that was probably important because I could walk the railroad track and not get lost, and see birds and flowers,” he recalled. “I was unbelievably lucky I think.”

This Depression-era baby got exposed to the surrounding natural habitats of the Red River and of Lake Lida in Minnesota, where his family summered in a cottage. Those summer idylls gave him free range of unspoiled woods.

He loved the forests, grasslands, flowers, birds. But feather and fowl most fascinated him. Why?

“I don’t know,” he said, pausing a moment. “It’s their sense of freedom – they can fly anywhere and do anything. They have incredible grace. They’re wild. I’m not interested in domestic birds – turkeys and chickens and so on.”

Ah, the wild. From that Arcadian childhood through his adult field work, wild places and things have most captivated him. His appreciation for birds has ever deepened the more he’s observed them. Among other things, he admires their acuity.

Wonderful world of birds

Johnsgard wrote, “I’m absolutely convinced that there is a lot more to what they know and perceive than what humans observe. I honestly think that we are underestimating birds, and certainly other mammals, when we avoid anthropomorphism too rigorously.”

He told the New Horizons, “I even more believe that today. We’re learning things about bird intelligence that were not only unknown but unbelievable just a few years ago, such as their solving fairly complicated problems of putting things together to get at food and things like that that really require some kind of logic. The first person I think that really began to realize that was Irene Pepperberg (Brandeis University professor and Harvard University lecturer), who taught her parrot 300 or 400 words in English and the bird would put them together in not quite sentences but use them in that kind of a logical combination. I think that was one of the first major insights into how smart birds can be. They are remarkably aware of their environment and of any alterations in it, which is a measure of their intelligence.”

He has special admiration for one species – the crane – that has ancient roots and that mates for life. He’s so taken with the Sandhill Crane he’s devoted more words to its study than any other bird. For decades he’s made a pilgrimage to see and record the annual Sandhill Crane migration in central Nebraska’s Platte River Valley,

“More than any bird I know,” he said, “they are amazingly aware of what’s going on. You don’t want to go anywhere near a crane nest because even if the female’s gone if she sees it has been disturbed she will abandon the nest. The only way you can do it safely is to wait until the nest is hatching – then she will stay there and protect it.”

His favorite bird has varied over time. “I think I was probably first enamored by Wood Ducks, which are so beautiful. Then I became interested in swans, especially the Trumpeter Swan, and now, of course, cranes. Even though the Whooping Crane is bigger and more beautiful, I think I’m more attracted to the Sandhill Crane. I’ve spent so much time with them. I’ve probably not spent more than 10 hours looking at Whooping Cranes. They’re so rare. The chances of seeing them in Nebraska are remote at best. But there’s a plethora of Sandhills.”

Sandhill Crane

Photo: usfws

The great migration

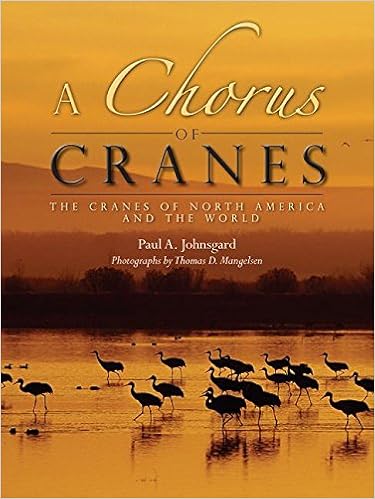

He has a special perch from which to watch the Sandhill Crane migration unfold courtesy of a cabin owned by internationally known wildlife photographer, Tom Mangelsen. The two men go way back. Mangelsen, a Grand Island native who did part of his growing up in Omaha, was a student and field assistant under Johnsgard, who mentored him in the 1970s. These friends and colleagues have collaborated on several projects, including a documentary Mangelsen shot and Johnsgard wrote about the Sandhill Cranes and for a new book A Chorus of Cranes.

Johnsgard is among the ranks who feel the spring migration is one of the greatest shows on Earth. It is a sensory experience to behold between the massive numbers on the ground and in the air and the swell of their trumpeting call.

“It’s a combination of place and sight and sound, all of which are unique,” he said. “To have 50,000 cranes overhead is quite something. Cranes are among the loudest birds in the world, so it just about blows your eardrums out when they’re all screaming. And to have a sunset or a sunrise, as the case may be, and to have this beautiful river flowing in front of you – it just all makes for a unique site in the world. It’s all those things coming together.”

Johnsgard’s prose is usually straightforward but there are times he uses a more literary style if it fits the subject, and he can’t think of anything more deserving than cranes,

“In my book Crane Music there’s a section on the cranes returning to the Platte in the spring that I wrote in the style of a kind of prayer: ‘There’s a season in the heart of Nebraska and there’s a bird in the heart of Nebraska and there’s a place in the heart of Nebraska…’ So those three paragraphs come together and then I wrote – ‘There’s a magical time when the bird and the season and the place all come together.'”

In a CBS Sunday Morning report on the migration Johnsgard described the amplified cacophony made by that many cranes “as the sounds of a chorus of angels, none of whom could sing on key, but all trying as hard as they can.” The naturalist also described what these majestic birds remind him of. “It’s almost like watching ballet in slow motion, because the wing beats are slow and they move in such an elegant way.”

Johnsgard explained to the New Horizons why the area around Kearney, Nebraska is the epicenter for this mass gathering that goes back before recorded time. An ancestral imperative has brought the birds yearly through millennia and the presence of humans has not yet disrupted this hard-wired pattern.

“Well, Kearney didn’t do anything to attract it, but the Platte River had become increasingly crowded with vegetation, both upstream and downstream, so all these wonderful sandbars were disappearing and the area around Kearney was one of the last places where the Platte was something like its original form. Lots of bars and islands and not too much disturbance. The birds from the whole upper Platte and even the North Platte were being crowded more and more together and so now you have over 500,000 in an area of no more than 50 miles.

“If it were normal conditions, then in those same 50 miles you might have 40,000 or 50,000.”

The cranes that arrive in March and April, he said, “are not getting as much food as they should be getting, so they’re having to leave the Platte due to food competition before they really have as much fat on them as they should.”

He said conservation measures help by controlling dam water releases and diversions for irrigation, recreation and other uses and therefore keeping steady water levels through the year. The shallow Platte and its surrounding vegetation is a fragile ecosystem that requires monitoring and intervention. The Platte has benefited from a river management agreement between Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska to share the water and maintain enough flow for Whooping Cranes and other endangered species. The Sandhill Cranes are not endangered.

He expects the compact to be renewed before it expires, but it will require the governors of all three states to re-up. He feels the measures are adequate to protect the cranes and other wildlife that make the migration a wonder of the world.

Even though he’s been going to catch that great display of plumage for years now, it never ceases to enthrall him.

“It just about gives me chills,” he said. “I call it nirvana. It pretty much is like a state of bliss.”

That feeling is shared by many. When Johnsgard took noted nature writer David Quammen out to the Platte for the migration he wasn’t sure what this much-traveled adventurer would make of it since “he’s been everywhere to see the natural world,” said Johnsgard. “I took him out to a blind one late afternoon at the Crane Trust and everything happened perfectly and he said, ‘You know, of all the places I’ve been and all the things I’ve seen this is probably the best time I’ve ever had watching birds.’ He did say there’s a bird sanctuary in India where storks come in in a somewhat similar way but that it’s the only thing that could possibly match what we saw.”

Acclaimed conservationist and chimp expert Jane Goodall has been joining Johnsgard and Mangelsen for crane watching expeditions since about 2000. Even though she’s seen so much of the natural world she told CBS’s Dean Reynolds, “I wasn’t quite prepared for the absolutely unbelievable, glorious spectacle of all these thousands of birds coming in. It’s just unbeatable, and it’s really peaceful.”

A confluence of interest

None of this would have happened for Johnsgard – from hanging out in blinds with celebs to his words reaching general audiences – if not for a string of things that transpired in his youth. His call to be a birder started just as he entered school.

“When I was 5 or 6 I asked Mother for the salt shaker so I could go out and put salt on a Robin’s tail. Do you know that story?” he asked a visitor at his UNL office. “Well, it goes that if you put salt on a bird’s tail it becomes tame, and I wanted to have a tame Robin. I spent a lot of time trying to do that. I wanted to touch them.”

He made his first drawings of birds then, too. But the real origin of his imprinting may be traced to an experience in first grade.

“My first-grade teacher, Hazel Bilstead, had a mounted male Red-winged Blackbird in a glass Victorian bell jar. She lifted the glass and let me touch it and that really captured my attention. I’d never seen anything that beautiful that close. I’ve never forgotten it. I remember it as well as I did that very day. I think that my need to see live birds in detail began at that time. I later dedicated one of my books to Miss Bilstead’s memory.”

His passion got further fed when a camera (Baby Brownie Special) first came into his life at 7 or 8. He’s not been without a camera since. He’s gone through the whole evolution of 35 millimeter models. He shoots digital images today. On one of his office computers alone he estimates he has more than 20,000 archived photographs.

He supports high tech image capture projects like one by the Crane Trust that has camouflaged game cameras programmed to take pictures every half hour or when motion is detected.

“These six weeks or so the birds spend in the Platte Valley are critically important for them to acquire the amount of fat — energy — they need for the rest of their spring and summer activities. So it really is important to get this kind of data,” he told a reporter.

Even though he grew up hunting – it was simply part of the culture he was raised in – he eventually gave up the gun for the camera. “It increasingly bothered me to kill things that I spent hours watching,” he wrote.

The sanctity of nature became more and more impressed upon him the more time he spent in it. Having the sanctuary of those woods near the family lake cottage nourished him.

“I’d wander around there with my dog and chase skunks and get chased by skunks, look for bears. I’d heard there were some. I developed a little wildflower garden from the flowers in the woods and tended it until we finally sold the cottage in 2005. It was still thriving then.”

Many people played a role in nurturing his Thoreau-like rapture.

“My mother’s cousin Bud Morgan was a game warden and by the time I was 12 he realized I really loved birds, so he’d take me along and we’d count ducks and just talk about birds. That really helped a lot actually in directing my studying waterfowl. He taught me how to identify waterfowl.”

Thirsty to know everything he could about birds, Johnsgard practically memorized what books on the subject his town library held. One he used to particularly “delight in” is T.S. Roberts’ two-volume The Birds of Minnesota.

“I thought it remarkable that a little town library carried it because it was an expensive book for the time. It was a wonderful book. Still is.”

As it was readily apparent that young Paul was crazy about birds, his parents and others happily indulged his curiosity by gifting him with books that any birder would be proud to own. As a result, he possess today several first editions of classics, including Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac and F.H. Kortright’s Ducks, Geese, and Swans of North America. He has a later edition of John James Audubon’s The Birds of America.

He got his first field guide in college.

Until recently brought to his attention, Johnsgard said he didn’t realize how so many early life elements reinforced his interest in nature and birds. That background set him off on his odyssey as naturalist, wildlife biologist, birder, author and more.

Renaissance man

Tom Mangelsen (Images of Nature), who knows Johnsgard as well as anyone, said of him, “He’s a wonderful man and really inspirational. Nobody’s done that many books on birds. He’s remarkably prolific and a major intellect. It’s been a long, wonderful journey for me. We are dear friends.”

Mangelsen said Johnsgard likes to tell people that while he was not his best student he is his most famous former pupil. The two also enjoy sharing the fact that Johnsgard accepted him as a graduate student not based on his grades, which were poor, but on the family cabin Mangelsen offered him access to.

As far as Mangelsen’s concerned, Johnsgard is a real “Renaissance Man.” Indeed, in addition to being a scientist, educator, author, illustrator and photographer, Johnsgard’s a highly regarded artist. Several of his drawings and wood bird sculptures are in private collections or museums. For his line drawings he works from photo composites and specimens.

“Having photographs makes it possible to draw them accurately. A photograph though won’t give you much more than just an outline so you really need to be able to look at the thing from the front, from the sides, from the top to get a sense for its shape. So I like to have a specimen if I can. Most of the time I’ve been here I’ve had access to a reasonably good collection of stuffed birds. If that doesn’t do it, I can go over to the state museum and look at things.”

This stickler for details notices when people take artistic license or just don’t get it right.

“When I was in London at the National Gallery there was a painting by Rembrandt of a dead black grouse upside down ready to be plucked. It had the wrong number of primary feathers on the wing, so he wasn’t a birder.”

Johnsgard’s waterfowl carvings are much admired. He is self-taught. “I’ve been at it since I was a Boy Scout,” he said. One of his carvings is in the permanent collection of the Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery in Lincoln. “It’s a full-sized Trumpeter Swan preening. Up until then it was by far the biggest carving I’d done. It weighed about 50 pounds.” He based it on a photo he saw in National Geographic. He didn’t know what to do with the carving when he finished it.

“It was so big that the only place I could put it at home was on top of the damn refrigerator. It was gathering dust up there. Sheldon’s then-director, George Neubert, asked if I could loan him some of my decoys for a folk art show, so I put that thing down there and after it was over he asked me if I’d consider selling it. He told me later he thought it was one of the 10 best acquisitions he got during his time as director.

“Audrey Kauders, director of MONA (Museum of Nebraska Art), has been after me for years to give them a carving. Every time I see her, she says, ‘You promised me a carving.’ I’ve gotta do it.”

He is that rare scientist to have crossed over from academia to the mainstream. Some of that attention has come from the prolific number of nature books he’s written. A book he did with his daughter Karin Johnsgard, Dragons and Unicorns: A Natural History, is an allegorical-metaphorical work that’s never been out of print from St. Martin’s Press. Some of his straight nature books have been popular with the general public. His essays and articles in Nebraskaland, Nebraska Life and Prairie Fire have enjoyed wide readership. Then there’s the public speaking he does and the media interviews he gives.

“Anyone who has made a trip west to see the Sandhill Cranes is familiar with Paul Johnsgard,” said Julie Masters of Omaha. “His books, lectures and interviews on the subject inspire. To experience the cranes through his eyes is a great gift.”

Masters recently developed a friendship with him that’s enriched her appreciation for nature.

“I happened to be on the UNL campus in January and saw him out walking. We struck up a conversation and have been meeting every few weeks to discuss cranes and all sorts of other birds. It is a great privilege to learn about bird behavior from this highly regarded ornithologist ”

Paul Johnsgard and Tom Mangelsen, ©Sue Cedarholm

Reverence for nature

While Johnsgard appreciates having his work recognized and enjoyed, he could do without the fuss or fame, such as a recent Esquire magazine piece he was part of that featured “Men of Style” from different walks of life. He would much rather commune with wild things than reporters. He’s most at home sitting patiently in a blind watching birds or marveling at the array of wildlife drawn to a water hole on the Serengeti or contemplating the flora and fauna of the High Rockies. These are mystical spots and interludes for him.

“If I had a religion, it would be nature,” he said, “I think watching birds is the most spiritually rewarding thing I do.”

He realizes the notion runs counter to science but doesn’t much care, though he’s quick to point out, “I don’t believe in any god per se, but I have a reverence for what I see in nature, I don’t think those things were created by a god, but they’re god-like aspects of the world, Without wild things and wild places in the world it’d be a pretty dreary place, so I have that maybe Eisley (Loren)-like or Neihardt (John)-like idea of the world.”

Reading Neihardt’s Black Elk Speaks “mesmerized” Johnsgard, particularly the appearance of Snow Geese in several of Black Elk’s visions. Johnsgard, who was already considering a book on Snow Geese. felt compelled to respond in a new work that counterpointed what he knew about the biology of that bird with Native American views of it.

“I couldn’t sleep, so I started scribbling the outlines of what became Song of the North Wind. I went to the library and found all I could on the beliefs of the Plains Indians and also the Inuit.

I finally decided I had enough to write a book. I went up to the nesting grounds in Western Hudson Bay before I finished it.”

Rhapsodizing about the sacredness of nature is one thing, just don’t preach to Johnsgard about thou shalt dos and do-nots.

“I don’t go to church and I get pretty upset with people who are overly religious. I have been a member of the Unitarian Church. I went mostly for the good music and the important issues they talked about, but I haven’t been back in a long time. I prefer to spend my Sunday doing other things.”

The concept of a Higher Power, he said, is “something so amorphous it’s hard to put into objective words,” adding, “I think for everybody it’s a pretty personal thing.”

Questions big and small still consume Johnsgard, who juggles three book projects at any given time. In June he submitted the page proofs for his latest, The North American Grouse, Their Biology and Behavior. Now that the retired scholar is freed from teaching, he does whatever books come to mind these days but especially on subjects that he fills a void in.

Having reached the point where he doesn’t care about royalties anymore, he puts his work in the public domain via Digital Commons, where anyone can download his books for free.

As the bird flies

Not surprising for an octogenarian of arts and letters, his two-room office on the Lincoln campus is crammed with books as well as art and artifacts from his many travels studying birds across North America, Europe, Africa, South America, Australia. His extensive collection extends to his home.

A prized birding site he’s never been to is in the Himalayas, where the Black Necked Crane resides. “It never comes below 8,000 feet. It’s the last crane in the world I haven’t seen. There’s very few in captivity. I did see a pair at the International Crane Foundation. But the ultimate in birding is to go to the Himalayas to see this incredibly rare bird. I don’t think I’ll make it because my heart isn’t up to those altitudes anymore.

“There’s still four species of waterfowl in the world I haven’t seen and I don’t think I ever will. They’re in places like Madagascar and the East Indies – hard to get to and probably not worth the time and expense and effort to try to do it. But it’s still fun to think about what might be special about them.”

Most of his birding adventures are uneventful but he’s had close calls. A harrowing incident occurred in the Andes. “A guide and I were coming down off an 11,000 foot volcano in a jeep I’d rented when it suddenly lost its brakes on a one-way narrow road looking down on a canyon probably 3,000 feet deep. The road was lined with bushes and I thought the only way I could possibly stop was if I drove into the bushes and used them to slow us down. They finally did and we got the jeep stopped. We looked at the brake connection and where there should have been a bolt there was a leather shoe lace somebody used as a temporary measure. We retied the leather and made it down.”

On other excursions, he said, “I’ve been in really life threatening situations where I should have never gone. The worst place was Oaxaca, Mexico.” Drug cartel-fueled killings and kidnappings happen there. “The biologist who was there before me was macheted to death. I was advised to carry a pistol, so I got one at a pawnshop in Lincoln and as soon as I got home I took it back.” Johnsgard never had reason to use it.

During that same trip he realized as his departure drew near he lacked permits for the birds he’d captured. They were supposed to be quarantined, but he didn’t have the time. “So I thought I’d take a chance,” he said. Wishing to avoid a customs snag, he waited till midnight to access a remote border crossing point. When an inquisitive guard asked what he was carrying in back of the van he was driving Johnsgard acknowledged the birds but left out the part about restrictions on import. The guard then asked “What else you got back there?” and Johnsgard replied, “Well, that’s about it and it’s fine if you check back there, but look out for the snake – he might have escaped,” whereupon the guard whisked him through with, “Go on, get out of here.”

Paul Johnsgard – born smuggler.

He delivered his birds back to Lincoln and got a paper out of it.

A splendid place for birding without any drama is the Waterfowl Trust in England, where Johnsgard studied two years in the 1960s. It holds special meaning because he was befriended by its founder, the late Sir Peter Scott, who became a key figure in his life. Scott was the son of legendary British explorer Robert Falcon Scott, whose second Antarctic expedition ended in tragedy when he and his men died on the return trek after reaching the South Pole.

“Peter was 2 years old at the time,” Johnsgard explains. “The last thing Robert Scott wrote to his wife read, ‘Make the boy interested in natural history” So, growing up, it was sort of incumbent on Peter to become a biologist.”

He did. He also became a renowned wildlife artist. “The art work is what made him famous,” Johnsgard said. “He was a wonderful artist.” Just like his father before him, Peter Scott became a national hero. “He was involved in the Dunkirk extraction of British troops during World War II, Then he put together this great collection of birds. At the time I went to study at the Wildlife Trust it was the best in the world, Every species has its own unique aspects and that’s part of the fun of studying this. When I had 120 species of waterfowl in England it was like opening 120 gift boxes because they’re all a little different and its fun trying to describe how they are different.”

Scott helped start the World Wildlife Fund.

“He was a great symbol to me I guess of what you could do in art and conservation.”

Johnsgard said his time at the Wildfowl Trust “was incredibly important – it gave me the experience to write books and a world view. I met some of the most famous biologists of the day there.” The Nebraska transplant thought enough of his British counterpart that he and his wife named one of their sons after him. “I dedicated one of my books to him as well. He did a painting as a favor to me for one of my big books. I have all of his big books and he inscribed each one with a watercolor on the title page. He was a very kind and wonderful person. I had the highest possible regard for him.”

Scott pursued his interests up until his death at age 79 in 1989.

A cradle to the grave creative

Though officially retired, Johnsgard shows no signs of slowing down at 85. He wakes up most days at 4 a.m. and he either reads or writes at home before going to the office. He’s as busy as ever researching and writing about birds and habitats. Before he ever gets around to writing a book he assembles references. Hundreds of them. Once he starts writing, he’s fast. He admits that his work is “a compulsion.”

He feels his rare triple threat skills to not only write but illustrate and photograph books makes his projects more palatable to publishers. He said mastering things comes with repetition. “I think talent is largely what you put into it in terms of practice.”

He’s been producing things since he was small and he fully expects to continue creating until he dies.

His new friend Julie Masters, professor and chair of the Department of Gerontology at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, views him as a model for health aging.

“As the population ages, we need people who show us that creativity can and does increase with age,” she said. “Paul Johnsgard is someone who serves as an ideal role model for us all. His passion and enthusiasm for life and the beauty of nature allow those of us who are less learned a glimpse into a world that is made even more awesome through his instruction.”

Johnsgard is just grateful he found his calling and stayed true to the road-less-traveled. “I don’t know anybody I’d trade my life with. I’ve been very lucky.”

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

It was a different breed then: Omaha Stockyards remembered

I have been meaning to post this story for some time and only now got around to it. It’s a Reader (www.thereader.com) cover story from 1999 that takes a look back at the Omaha Stockyards only months before the whole works closed and was razed. Its demise, after years of decline following decades of booming business, ended a big brawny empire that at its peak was a major economic engine and a dominant part of the South Omaha landscape. I interviewed several men and one woman whose lives were bound up in the place and they paint a picture of a city within a city about which they felt great pride and nostalgia. The Stockyards was its own culture. These stockmen and this stockwoman were sad seeing it all go away, as if it was never there. Around that same time, I wrote a second depth story about the Stockyards for the New Horizons that gave even more of a feel for the scale of operation it once maintained. Here is a link to that story–

It was a different breed then: Omaha Stockyards remembered

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Unfolding a stone’s thrown away from a South Omaha strip mall is a scene straight out of the Old West. A sturdy codger called B.J. drives a dozen burnt orange cows through a mosaic of wooden pens and metal gates. As he flogs the recalcitrant beasts with a whip, his sing-song voice calls to them in a lingo only wranglers know.

“Hey, hey, hey, hey, hey…yeh, yeh, yeh…Whoa! Get up there. Whoa! Yeh, yeh, yeh…Go, get up there. High, high, high, high. Whoa. Gip, gip, gip, gip…High, high, high, high…Yeh, yeh, yeh, yeh…C’mon, babies. C’mon, sweethearts. C’mon, darlings. Get up there.”

Welcome to the Omaha Stockyards, a once immense marketplace and meatpacking center which, owing to changing marketing trends and public attitudes, has gone to rack and ruin. Since 1997, when Mayor Hal Daub announced a city-led plan to buy the site, raze nearly the entire complex and redevelop it, the Omaha Livestock Market, which operates the yards, has been marking time. In March, market staff and traders vacated offices in the Livestock Exchange Building and have since taken up makeshift quarters in a nearby cinder-block structure. The yards are expected to close early this fall, possibly by October, and the market will move from the site it has operated at for 116 years and re-open in Red Oak, Iowa. Just as the Stockyards will soon disappear, its halcyon days are now distant memories.

But for survivors of those times, like Bernie J. McCoy, the past is very much alive. As painful as the impending end is for them, they revel in the spirit of the people who worked there and their special way of doing business. To the hard physical labor performed, the injuries incurred, the grueling dawn to dusk schedule and harsh elements endured.

“You had to want to be here and work those long hours. It was a different breed then,” McCoy says.

Yes, the fat times are long gone, never to return, but their legacy lives on in the work McCoy and others still do there. They retrace the very paths taken by countless others before them, forging a direct link to the area’s frontier past. In the yards’ cavernous, skeleton-like environs, McCoy’s voice blends with the sound of bawling calves, squealing hogs and creaking gates to resonate like the mourning, wailing echo of restless souls from long ago. Requiem for the Stockyards.

Recently, McCoy and some fellow Stockyards veterans recounted for The Reader the good old days at this soon to be vanished landmark. Their memories unveil a rich, vibrant, muscular chapter of Omaha’s working life well worth preseving. Their words celebrate an enterprise that dominated the landscape and shaped the city unlike no other. Where the once overbrimming yards pulsed with the lifeblood of Omaha’s economy, it is now a relic condemned to the scrap heap – a decript place largely given over to pigeons and rats. Blocks of abandoned, weed-strewn pens stand empty. Crumbling, sagging buildings blight the landscape. Where it took hundreds of men many hours to drive, feed, water, sort, weigh, trade and load livestock daily, now all activity unfolds in an hour or two amid a dozen pens holding perhaps a hundred cattle, a few hands putting them through their paces.

The traffic whooshing past on L Street overhead is a metaphor for how this forsaken former juggernaut has been passed by in the wake of progress, leaving it an anachronism in a city grown intolerant. Yet, it lingers still – a ghostly visage of another era.

By the close of 1999 only tracts of of dilapidated pens and barren livestock barns will remain. Soon even these meager traces will vanish when the city levels the whole works in a year or two. leaving only the looming presence of the massive Exchange Building – for decades the focal point and symbol of the sprawling , booming market. Even its future is not secure, hinging on if if developers find financing for its pricey renovation.

We helped build this city

Today, from atop the weather-beaten wooden high walk spanning the grounds, it’s hard imagining when the yards teemed with enough acitivty to make it the largest livestock market/meatpacking center in the nation. Oh, animals still arrive at market every week but comprise only a trickle of the mighty stream that once flowed around the clock.

Unless you’re pushing middle age, you never saw the Stockyards at its peak. When tens of thousands of cattle, hogs and sheep arrived daily by rail and truck. Millions of animals a year. All transactions, each worth many thousands of dollars, were consummated by word of mouth alone. Trading generated millions of dollars a day, perhaps billions over time.

Livestock were sold primarily to the big four packing plants and the many smaller independent plants then dotting the yards’ perimeter. Stock were also shipped to other parts of the country, even overseas. The place was once so big, its impact so vast, that the Omaha market helped set the prices for the industry nationwide and ran its own radio station and newspaper. As a center of commerce, the Stockyards ruled. At their peak, the packing plants employed more than 10,000 laborers. The Stockyards company itself employed hundreds, including office staff to manage the business as well as outdoor crews to handle animals, maintain pens, chutes and barns and run its own railroad line. Hundreds more did business there as livestock commission salesmen, order-buyers, inspectors, et cetera. The people converging there on any trading today ranged from frugal farmers to rough-hewn truckers to smooth-talking traders to well-heeled bankers.

Besides being THE meeting place for anyone who was anybody in the agriculture industry, the Exchange Building offered an oasis of comfort with its cafeteria, dining room, ballroom, bar, soda fountain, cigar stand and barbershop. Basement showers let you wash the stink off but somehow you always knew when a hog man was around. Nearby watering holes, eateries, stores and hotels catered to the stock trade’s every pleasure. The aroma of sweat, blood, manure, hay, grain, cologne, whiskey and tobacco created what Omaha historian Jean Dunbar calls, “The smell of money.”

“Fifty years ago the Stockyards and packing plants were the hub of Omaha, Nebraska. Nowadays, young people don’t appreciate what the Union Stockyards Company did for Omaha. We helped build this city. Everyone wanted to work here. You don’t know the pride we had. Come November, there will be nothing left to remember we were ever here or even existed. Nothing,” declares McCoy, 69, a livestock dealer who’s worked at the Omaha Stockyards for 54 years.

It was the people

From 1934 to 1969 Doris Wellman, 83, was one of the few women executives in the livestock trading business. Her ties to the place run deep. Her grandfather and father worked there, as did her late husband Ralph and his grandfather and father before him. Incidentally, she never minded the stench because she never forgot “that was my bread and butter.” Above all, the genuineness and the esprit de corps of the people there impressed her. “Every man at that Stockyards was a gentleman as far as I’m concerned. Everybody was always very cordial to you. Everybody spoke to everybody else. There was nothing phony about it. We had our own little community there. That camraderie you will never find anyplace else.”

“When someone was in the least anount of distress,” she adds, “a collection was taken up.” McCoy says, “One trip through the Exchange Building might net 10 or 15,000 dollars,” like the time enough funds were raised to stop foreclosure on Carl “Swede” Anderson’s house.

“Of course, it was the people that made the Stockyards. They took care of their own. That’s what I miss more than anything about it,” says Jim Egan, 66, whose memory of the place goes back before World War II, when as a boy he hung around his father, a livestock order-buyer. Egan later became a livestock dealer himself. “I kind of grew up there as a little kid. I looked up to the head cattle buyers for the big packers, but they were as common as could be. They didn’t look down at anybody. There was never any airs put on. Absolutely not.”

Not that there wasn’t a caste system owing to one’s position and seniority. “There was kind of a pecking order,” Egan says. The more experienced men bought and sold the prime, top-dollar beef, while the green ones learned the trade from the bottom up. Those who carried the most weight and the longest length of service, he says, earned a wider berth, a choicer selection and a primer office location. “Back in the ’50s the head cattle buyers with Armour. Swift and Wilson all wore suits and ties. They had on boots, too, in those days. If you wanted to sell one some cattle you didn’t call him by his first name – it was Mister,” says Ron Ryhisky, 63, a packer-buyer now in his 46th year at the yards. “They thought they were God,” says cattle seller Art Stolinski, who adds that cattle buyers were made even more intimidating by working on horseback.

Men only advanced after an apprenticeship learning breeds, grades, weights. “I drove cattle 10 years for Omaha Packing Co. before I got a chance to buy a few cows, Ryhisky says. Stolinski, now in his 61st year, adds, “I came to work as a yardman for my father. I was a gofer – I cleaned pens, I shook hay, I drove cattle. That’s how you came up the ladder.”

Doing business

Haggling in the yards got heated. Bidding became a pitched battle. Harsh words exchanged between buyers and sellers were soon forgotten though because everyone understood being an S.O.B was just part of doing business. “That was the other guy’s way of trying to beat you,” Ryhisky says. “Sure, the guys argued and everything, but as soon as the trade was done, it was done. Nobody stayed mad,” Egan notes. He adds that men cursing each other over the price of bulls played cards or shared a meal and some drinks a few hours later.

Egan found no “softies” among buyers. “The only time they’d be a soft touch is if they were really desperate for cattle.” Stolinski says some shippers made for tough customers. “Some guys were just hard to sell for. They’d go, ‘Well, that ain’t enough. Get more. Them cattle are worth more than that.’ So you didn’t sell them cattle and then risked not getting them sold for what they were bid, and getting set.”

Like any other traded commodity, livestock were subject to supply and demand dynamics. As Egan explains, “The buyer was trying to buy the cattle for as cheap as he could. The salesman was trying to get as much as he could for his customer. Both knew pretty close where those cattle were going to sell. When it got right down to the nitty-gritty, if the buyer had another load of cattle he thought he could get, then he probably had a little leverage. If he didn’t, then the man selling the cattle had the leverage. That knowledge moved around the yards fairly quick.”

One way the latest market updates and bid orders reached buyers and sellers was by runners. “The packer might decide to take off 50 cents or a dollar (per hundred pounds) and the only way to tell those buyers was to send a runner, usually some kid, who’d run around that high walk trying to get the word to the cow buyers, the heifer buyers, the steer buyers. That kid was running, too,” Stolinski says. “When you saw that kid running fast, you knew he had something to tell the packer-buyer.” Later, radio transmitters replaced runners.

Ball-busting tactics aside, the yards brooked no dirty deeds. As soon as a swindler got exposed for “welshing on a deal,” Egan says, the word spread and he was banned. “You’d never get another animal.”

“If you were a cheat,” Ryhisky adds, “you never came back in.”

Badmouthing a competitor was strictly taboo. Wellman explains, “I can remember whenever my husband Ralph hired a cattle salesman the first thing he told him was, ‘When you go to the country to solicit business, don’t knock any of your opponents. Every knock is a boost. I never want to hear you maligned another commission man on the road.’ We trained people like that and they grew up knowing that’s the way to do business.”

A sense of trust and fair play permeated the yards. It’s what allowed trading to unfold entirely by spoken word – with no written contracts. A man’s word or handshake was enough. It’s still done that way.

“The uniqueness of the way business was conducted,” distinguished the stockyards industry,” Egan says. “Everything was done by word of mouth. It was an honor system you adhered to. It’s just the way it was.”

“Integrity is a word that comes to mind. Anyone that was here any time at all had it. There was nothing signed,” Stolinski says, adding sarcastically, “Now, you go buy a necktie and you gotta make three copies.”

As Wellman put it, “Do you of another business where you can transact millions of dollars worth of business everyday without signing a paper? Where you word is your bond, and if it isn’t, you won’t last?”

According to Gene Miller, a long-time commission man, any livestock deal was the sole province of the buyer and seller. The shipper or producer who consigned his livestock for sell to a commission firm was usually present but only participated if the salesman conferred on the bid. Rare disputes were mediated before a board of livestock exchange officials. “It was up to the buyer and seller to settle. If they couldn’t settle then they went before the Livestock Exchange Board. At any rate, your word had to be all of it or otherwise you had no market.”

Consistent with its open market concept, the Stockyards brought many buyers and sellers together in one spot to arrive at the fairest market price. A single load of cattle might be shown to and bid on by any number of buyers. To prevent a free-for-all, rules governed the bidding process.

If a buyer looked at a load of cattle and made a bid that the salesman accepted, the buyer was bound to take them. However, if the buyer left the salesman’s alley before the bid was accepted, the buyer was not obligated. Similarly, Egan explains, “If a guy was buying, say, steers and another order-buyer or packer-buyer came along, he had to wait outside the alley until the salesman got through showing that first buyer. If the salesman got the price, he might sell a load of cattle to the first guy that looked at ’em. But that buyer wouldn’t sit on a load of cattle and let everybody in the Stockyards look at ’em because he’s got the pressure of the second buyer breathing down his neck.”

Once cattle arrived at the yards, they were usually bedded down a night before traded. The idea was to feed and water stock in order to put weight back on lost (shrinkage) during shipping. While the market didn’t open until 8 or 8:30 a.m., commission men started their workday by 4:30 or 5 in order to get the cattled consigned to them out of holding pens and driven to their firms’ alleys and pens. As the cattle were locked up, sales agents had to find a “key man” at the yards to unlock the pens. Each saleman hustled to get his cattle released ahead of the others.

Stolinski says tempers often flared over who was first in line. “If he happened to be bigger than you, you wouldn’t argue, but some of that happened, too.”

The volume of livestock being traded was so thick that men often had to wait hours in line to get their bunch released or weighed. Each time cattled were moved they were counted, a serious business too given the sheer numbers of animals and the hefty dollar values they represented. A paper trail of receipts and weigh bills followed each load.

Livestock being led to a local packinghouse were driven through an underground tunnel. To help track each load chalk marks were applied to animals. Aptly named Judas goats were used to lead the packs, mostly sheep, placidly through. Steers were run through to chase out the foot-long rats. To control fighting bulls cows were often mixed in. Even with this confluence of activity – trucks and trains arriving and departing and assorted livestock being sorted and driven through a mazework of pens – the stockmen agree there were few major screwups. “It was amazing to me that with the thousands and thousands of livestock that moved through here, we kept them straight,” says Carl Hatcher, a 44-year veteran of the yards and today manager of the Omaha Livestock Market.

“It was amazing how few miscounts we had,” Stolinski says.

More amazing still because despite the paper trail dealers kept most of the figures in their head. “When I went to work for my dad I came out with a tab and pencil and started writing stuff down, and he said, ‘Throw that away. If you have to start writing everything down, forget it. Learn to remember.’ You did,” Stolinski recalls. “You developed your memory that way. Even now, I can remember cattle I sold a couple weeks ago – what they were, what they brought, what they weighed. A lot of buyers could just look at cattle and remember, too.”

In this January 1942 photo, a line of cattle trucks extended 4 miles at the Omaha Stockyards. THE WORLD-HERALD

Out of harm’s way

As smoothly as it all ran, some things could still foul up the works, like one of the 11 scales breaking or an animal going down and not being able to get back up. Then there were close calls with ornery animals. Some broke containment, leaping fences and escaping into surrounding streets, where crews shooed them into the yards or cowboys roped and dragged them back. The wildest ones were shot dead. A mean animal in an alley or a pen sent men scurrying for the fences; the lucky ones clambered atop unscathed; the less fortunate ones got pinned, stomped or gored. Every man can tell you about his close calls and rough scrapes. Harold Hunter, a 78 year old cattle delaer who’s been hit by a heifer and rolled by a bull, among other things since his 1944 start, recalls, “I’d only been here two weeks when I was holding a gate while my boss was on a horse sortin’ these steers. They were probably 3 and 4 year-olds, weighing 1,250, and they moved fast. Two of ’em went by me just like that. My boss said, ‘Kid, they ain’t going to hurt you, just stop ’em.’ Well, the next one went right through the gate and broke it down. Those western range cattle had never seen a man on foot, They respected a horse, but not a man on foot.”

It paid knowing how to stay out of harm’s way. “If you had the gate,” Stolinski says, “you didn’t get behind it to hold ’em back because they’d hit that gate and you’d go with it. You always had to have that gate on the side of you, so when they hit it the gate went and you climbed up the fence…maybe.”

Hatcher, who saw plenty of busted noses and broken bones from swinging gates, says you were well advised “to have your escape route” planned. “Like when we unloaded cattle off the box cars, the way the railroad set the cars , they wouldn’t match up with the opening into the chute. Well, when you’d open a box car door and flop a board in for them to come out, you hoped you could shout and move ’em into the chute opening. But sometimes they’d get upset seeing the fences and turn the wrong way and go down the dock where you were standing. One night a fellow named Dale Castor was there with our night foreman, Orlin Emley, when some old western wild cows came out and turned down the dock, Emley already had the escape route figured. He was climbing the fence when Castor, who hadn’t figured his out, grabbed a hold of Emley and tried to crawl right up his back. Emley was shouting, ‘Get off me, find your own goddamn fence.’ That happened a lot.

“The sound of a gate slamming or people yelling can cause soome animals to run over or through everything they can fin. A wild or mean one like that won’t stop no matter how much you yell or wave a stick or whip or cane or anything else. You know which ones are comin’ out lookin’ for you. you can’t top ’em. You look for your spot on the fence and keep your distance. You gotta know what your doin’ and pay attention.”

Egan says hard to handle animals were often red-flagged on the paperwork accompanying them to give men a heads-up warning.

The risk of injury never goes away. Only two years ago Bernie McCoy had a run-in with a heifer that left him with three cracked ribs. There’s no end of hazards either. Try negotiating a narrow, icy, wind-swept high walk in winter. Or lashing a cow with a whip and a piece of leather tearing off into your face or leg. “It’s like getting shot with a pellet gun,” says Stolinski.

Bulls, because of their size and disposition, pose real trouble. As Stolinski says, “If a bull hits you, he don’t (sic) let you fall to the ground. He just keeps hittin’ you into the fence. Gettin’ kicked would hobble you most because you either got it in the knee or hip.”

But other animals could hurt you, too. Stolinski recalls a yardman named Dale Lovitt who had a leg ripped open by a boar in the hog yards and, true to the stockmen’s macho creed, got stitched and returned for a snort.

“They took him to the hospital, sewed him up, and he got back here and went rght to the bar and had a shot.”

Hatcher witnessed the grit of yardman Hubert Clatterbuck, who took a nasty spill “when the wild horse he was training reared up. causing him to lose his balance. He went right over the back of the horse and fell right on the concrete in the alley…landing on his shoulders and head. Hell, I thought sure he was dead. I called a rescue unit but, shoot, he just shook it off.”

You gotta have it in you

“The hours got terrible with the commission firms, let me tell you,” says Gene Miller. “Today, you couldn’t pay any man enough to work the way we did, and those hours, 5 a.m. to 9 p.m. The hours were too long . The work was too hard. It was seven days a week.” Yet, to a man, they say they don’t regret any of it. Not one hour or day.

And Bernie McCoy adds, “You were always moving,” whether fetching cattle from the hill (the west yards stretching clear to 36th Street) or driving them to the hole (the sloping southwestern yards). “I don’t how many miles we walked a day,” Ryhisky adds. The work went on regardless of the weather. “Sometiimes the conditions were just just rotten,” Stolinski notes. “Standing out there weighing cattle when it was rainy and sloppy like hell. The cattle snapped their hoofs in a puddle and it would splash all over you. We didn’t have rain suits in those days. You had a jacket and you just got wet. You had to keep just working. There wasn’t time to go in and change because those cattle had to be weighed in so many minutes.”

Away from the yards, commission men traveled weekends soliciting business from farmers and ranchers. It was not uncommon for a salesman to put 40,000 miles a year on his car. Since the advent of direct selling in the ’60s. packer-buyers like Ryhisky now solicit customers.

Yardmen have always had it the roughest, facing the same risks from animals and the same dismal weather conditions while building and repairing pens, throwing bales of hay, cleaning alleys and chutes, et cetera. “You gotta have it in you,” Stolinski says. Plenty haven’t. Hatcher saw many men quit after a day or two slogging through muck and shoveling manure. He says the worst jobs included clearing snow atop the auto park, aka, Hurricane Deck, in the winter and picking up animal dumps and hauling them away in the summer.

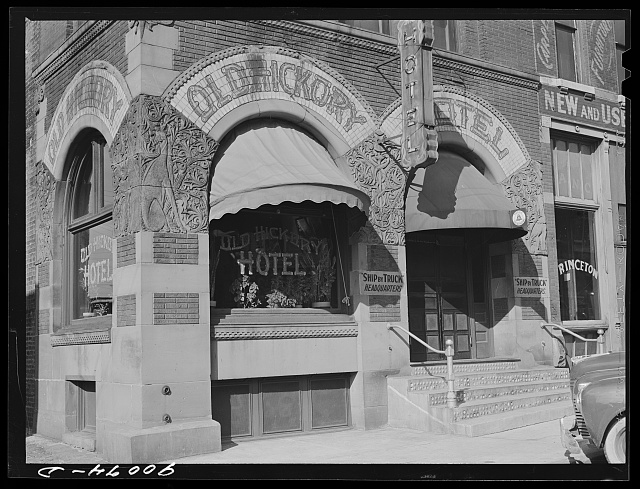

Stockmen’s and farmers’ and truckers’ hotel near Union Stockyards. South Omaha

They played hard

After a hard day’s work or big sell, men unwound bending an elbow at nearby gin joints. A few braced themselves before punching in each morning, like notable imbiber Claude Dunning, who is said to have drained a half-pint daily before the market even opened. “Some of the old guys would walk in the front of the building, make a left turn into the bar and get a drink of whiskey, then change clothes and off they’d go,” Stolinski says. “Most of the commission men had charge accounts in the bar. If you were a regular, they’d give you a second shot free.”

Fights inevitably broke out.

“They played hard,” Hatcher says, so much so the yard company cracked down. Still, there were ways, like riding in the caboose of a train shipping bulls to Chicago. Two men went along to see the bulls go watered and got tanked themselves on a case of beer. “We had fun,” Ryhisky says.

Other diversions ranged from regular craps and gin rummy games to sports betting. Once, the Stockyards took up a collection to bankroll local gin rummey king Art Jensen, a livestock trader, for a Las Vegas tournament. “They bought shares in him,” Jim Egan says. “He lost.” A good friend of Jensen’s was future Nevada gambling maven Jackie Gaughan, then a bookmaker, who allegedly used a livestock trading office as a bookie front. “You could get a lot of bets laid down there,” recounts Egan. Legend has it local stockmen sold cattle on a cash-only basis to one shady character back east who reputedly once brought a suitcase with $250,000. It’s said the fellow eventually ran afoul of the mob and was killed.

Francis “Doc” Stejskal, a former livestock commission salesman and later a packer-buyer, says people at the yards were not necessarily the raucous bunch many outsiders assumed. “I think a lot of folks thought it was rough and rowdy. That when business was over we all went down to some South Omaha cathouse. It wasn’t that way.”

Doris Wellman adds, “It was the wrong interpretation completely.” That’s not to say there weren’t establishments where women of ill repute rendered certain illicit services. “The dollies were in the Miller Hotel. The guys would take care of things there,” Harold Hunter says. “Big Irene” is said to have been a favorite among johns frequenting the whorehouses and clip joints comprising South O’s red light district.

Those who could not control their appetites were brought down. “Wine, whiskey and women ruined quite a few guys out here,” Ron Ryhisky contends. “I’d hate to have seen the casinos here back in the ’50s. We would have had a lot of broke men.” Adds Stolinski, “A lot of money was made and a lot of good men were lost to high living.”

But for most a big night on the town meant downing a few drinks and eating a hearty meal at Johnny’s Cafe, where stockmen had carte blanche. Many a farmer came to market with his family. While his stock was traded his family waited in the Exchange Building and later, fat check in hand, they went for a shopping spree. Philip’s Department Store was a favorite stop. In an industry that was a crossroads for people from nearly every strata of society – rural-urban, rich-poor – the Stockyards saw its share of memorable characters. Take Gilley Swanson, for instance. The stockmen say Swanson, a farmer, had such utter disregard for his own hygeine that he was infested with lice and slept in the yards’ hay manger. It got so bad, they say, that he was barred from the Exchange Building and people steered clear of his approach. Then there was Bernard Pauley, a mammoth shipper who overwhelmed his bib overalls and had a habit of stepping right from the feedyard into his latest Cadillac, soiling the interior. Forbidden from drinking at home by his wife, he went on benders in the big city, buying endless rounds for himself and his cronies.

Looks could be deceiving. A rancher might pass for a ripe vagrant after traveling by rail with his cattle, yet could pocket enough from one sale to pay cash for a new car and still have ample money left over. Eastern dudes passing through often didn’t know one end of a cow from the other, but knew balance sheets and some say the New York-based Kay Corp., which bought the ailing ards in 1973, simply wrote it off.

These are Stockyards people

Then, as now, money talked. For decades the Stockyards pumped the fuel powering Omaha’s economic engine. Sotuh Omaha owed its existence to the place. The Stockyards wielded power and commanded respect via the jobs it provided, the charitable works its 400 Club performed, the goodwill tours its members made and the boards its executives served on. This far-reaching impact is why stockmen feel such pride even today. “More than you’ll ever know,” says Ryhisky. As business there steadily declined the last 25 years the Stockyards saw its influence wane, operations shrink and grounds deteriorate. Now, with the City of Omaha practically running the Stockyards out of town and erasing any remnant of the past (although, as bound by law, the city is paying the relocation costs and commissioning a historic recordation of the site), it’s no wonder survivors feel forgotten and belittled.

Doris Wellman tells a story about Johnny’s Cafe founder Frank Kawa that sums up how stockmen were once regarded and would like to be remembered. “A group of us were having dinner at Johnny’s one evening years ago and the people nest to us thought we were a little too noisy, so they complained to Mr. Kawa. He told them. ‘If you don’t like it, get up and leave. These are Stockyards people. They built this place.'”