Jim Taylor and Alexander Payne, winners Best Screenplay for Sideways

Archive

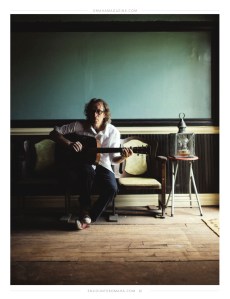

Creative to the core: John Hargiss and his handmade world

Creative to the core: John Hargiss and his handmade world

©by Leo Adam Biga

©Photos by Bill Sitzmann

Appearing in the July-Auguat 2016 issue of Omaha Encounter Magazine (http://omahamagazine.com/category/publications/the-encounter/)

Master craftsman and stringed instrument maker John Hargiss learned the luthier skills he plies at his North Omaha shop from his late father Verl. In the hardscrabble DIY culture of their Southern Missouri hill and river bottom roots, people made things by hand.

“I think the lower on the food chain you are, the more creative you become. I think you have to,” Hargiss says.

He observed his late father fashion tables and ax handles with ancestral tools and convert station wagons into El Camino’s with nothing more than a lawnmower blade and glue pot. Father and son once forged a guitar from a tree they felled, cut and shaped together. The son’s hands are sure and nimble enough to earn him a tidy living at his own Hargiss Stringed Instruments at 4002 Hamilton Street. His shop’s filled with precision tools (jigs, clamps_, many of vintage variety.

Some specialized tools are similar to what dentists use. “I do almost the same thing – polish, grind, fill, recreate, redesign, restructure.”

Assorted wood, metal and found objects are destined for repurposing.

“I have an incredible way of looking at something and going, ‘I can use that.’ Everything you see will be sold or used one way or the other.”

In addition to instrument-making, he’s a silversmith, leather-maker and welder.A travel guitar he designed, the Minstrel, has sold to renowned artists, yet he still views himself an apprentice indebted to his father.

“He just made all kinds of things and taught me how to use and sharpen tools. Being around that most of my life it wasn’t very difficult for me to be like, ‘Oh, that’s how that works,’ For some reason my father and I had a connection. I couldn’t get enough of that old man. He was a mill worker, a mechanic, a woodsman. When he wasn’t doing that he was creating things. He was a craftsman. Everything I know how to create probably came from him. Everything I watched him do, I thought, ‘My hands were designed to do exactly what he’s doing.’ On his tombstone I had put, ‘A man who lived life through his hands.'”

Hargiss also absorbed rich musical influences.

“You were constantly around what we don’t see in the Midwest – banjo players, violin players, ukulele players, dulcimer players. There are a lot of musicians in that part of the world down there. Bluegrass. Rockabilly. Folkabilly, That would be our entertainment in the evenings – music, family, friends. Neighbors would show up with instruments and start playing. Growing up, that was our recreation.”

He feels a deep kinship to that music.

.”The roots of country music and the blues come out of being suppressed and poor,” he says. “All those incredible sad songs come from the bottom of the barrel.”

His father had a hand in his musical development

“My daddy was a good musician and he taught me to play music when I was about 9. By 11 I was already playing in little country and bluegrass bands. I can play a mandolin, a guitar, a banjo, a ukulele, but I’m pretty much a guitar player. And I sing and write music.”

Hargiss once made his livelihood performing. “I like playing music so much. It’s dangerous business because it will completely overpower you. I knew I needed to make a living, raise my children and have a life. so playing music became my hobby. I worked corporate jobs, but I kept being pulled back. It didn’t matter how hard I tried. I’d no more get the tie and suit off then I’d be out in the garage making something else. The day I quit that job I went to my boss and said, ‘I can’t do this anymore, my heart’s not in it. I’m going to start building things.”

It turned into his business.

Hargiss directly traces what he does to his father.

“I watched him repair a guitar he bought me at a yard sale. The strings were probably three inches off the finger board. I remember my daddy taking a cup of hot coffee and pouring it in the joint of that neck and him wobbling that neck off, and the next I knew he’d restrung that guitar. I think that’s when I knew that’s what I’m going to do.”

The memory of them making a guitar is still clear.

“The first guitar I built me and my daddy cut a walnut tree, chopped it up and we carved us a dreadnaught – a traditional Martin-style guitar. I gave that to him and he played that up to the day he died.”

“I’m fascinated by architectural design in what I create and in what I make. I study it.”

He called on every ounce of his heritage to lovingly restore a vaudeville house turned movie theater he didn’t know came with the attached North O buildings he purchased five years ago. The theater lay dormant and unseen 65 years, like a time capsule, obscured by walls and ceilings added by property owners, before he and his girlfriend, Mary Thorsteinson, rediscovered it largely intact. The pair, who share an apartment behind the auditorium, did the restoration themselves.

The original Winn Theatre opened in 1905 as a live stage venue, became a movie theater and remained one (operating as the Hamilton and later the 40th Street Theatre), until closing in 1951. Preservation is nothing new to Hargiss, who reclaimed historic buildings in Benson, where his business was previously located. At the Hamilton site he was delighted to find the theater but knew it meant major work.

“I’ve always had this passion for old things. When we found the theater I remember saying, This is going to be a big one.”

Motivating the by-hand, labor-of-love project was the space’s “potential to be anything you want it to be.” He’s reopened the 40th Street Theatre as a live performance spot.

Hargiss is perpetually busy between instrument repairs and builds – he has a new commission to make a harp guitar – and keeping up his properties. Someone’s always coming in wanting to know how to do something and he’s eager to pay forward what was passed on to him.

The thought of working for someone else is unthinkable.

“I get one hundred percent control of my creativity. I’m not stuck, I’m not governed by, Well, you can’t do it this way. Of course I can because the sound this is going to produce is mine. When you get to control it, then you’re the CEO, the boss, the luthier, the repairman, the refinisher, the construction, the engineer, the architect. You’re all of these things at one time.”

Besides, he can’t help making things. “There’s a drive down in me someplace. Whatever I’m working on, I first of all have to see myself doing it. Then I go through this whole crazy second-guessing. And then the next thing I know it’s been created. Days later I’ll see it and go, ‘When did I do that?’ because it takes over me and it completely consumes every thought I have. I just let everything else go.”

Creating is so tied to his identity, he says, “It’s not that I can’t find peace or can’t be content” without it, “but by lands I like it.”

Jim Taylor, the other half of Hollywood’s top screenwriting team, talks about his work with Alexander Payne

No matter how Alexander Payne’s in-progress film Downsizing is received when released next year, it will be remembered as his first foray into special effects, science fiction, big budget filmmaking and sprawling production extending across three nations. But the most important development it marks is the rejoining of Payne and his longtime screenwriting partner, Jim Taylor, whose contributions to the film’s they’ve collaborated on often get overlooked even though he’s shared an Oscar with Payne and has been nominated for others with him. In truth, Payne and Taylor never broke with each other. Payne did make both The Descendants and Nebraska without Taylor’s writing contribution, but following their last collaboration, Sideways, and during much of the period when Payne was producing other people’s films and then mounting and making the two films he directed following Sideways, these creative partners were busily at work on the Downsizing screenplay. It’s been awhile since I last interviewed Taylor. I am sharing the resulting 2005 story here, It is included in my book Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film. A new edition of the book releases Sept. 1.

As my story makes clear, Payne and Taylor go farther back then Citizen Ruth, the first feature they wrote together and the first feature that Payne directed. Their bond goes all the way back to college and to scuffling along to try to break into features. After Citizen Ruth, they really made waves with their scripts for Election and About Schmidt. And then Sideways confirmed them as perhaps Hollywood’s top screenwriting tandem. They also collaborated on for-hire rewrite jobs on scripts that others directed.

I will soon be doing a new interview with Taylor for my ongoing reporting about Payne and his work. Though Taylor is not a Nebraskan, his important collaboration with Payne makes him an exception to the rule of only focusing on natives for my in-development Nebraska Film Heritage Project. By the way, one of the films that Payne produced during his seven year hiatus from directing features was The Savages, whose writer-director, Tamara Jenkins, is Taylor’s wife. That Payne and Taylor have kept their personal friendship and creative professional relationship intact over 25-plus years, including a production company they shared together, is a remarkable feat in today’s ephemeral culture and society.

NOTE: For you film buffs out there, I will be interviewing Oscar-winning cinematographer Mauro Fiore and showing clips of his work at Kaneko in the Old Market, on Thursday, July 21. The event starts at 7 p.m. and will include a Q & A.

Link to my cover story about Mauro and more info about the event at–

https://leoadambiga.com/…/05/04/master-of-light-mauro-fiore/

Jim Taylor, the other half of Hollywood’s top screenwriting team, talks about his work with Alexander Payne

Published in a fall 2005 issue of The Reader

©by Leo Adam Biga

There’s an alchemy to the virtuoso writing partnership of Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor, Oscar winners for Sideways (2004) and previous nominees for Election (1999), that resists pat analysis. The artists themselves are unsure what makes their union work beyond compatibility, mutual regard and an abiding reverence for cinema art.

Together 15 years now, their professional marriage has been a steady ascent amid the starts and stops endemic to filmmaking. As their careers have evolved, they’ve emerged as perhaps the industry’s most respected screenwriting tandem, often drawing comparisons to great pairings of the past. As the director of their scripts, Payne grabs the lion’s share of attention, although their greatest triumph, Sideways, proved “a rite of passage” for each, Taylor said, by virtue of their Oscars.

Taylor doesn’t mind that Payne, the auteur, has more fame. ”He pays a price for that. I’m not envious of all the interviews he has to do and the fact his face is recognized more. Everywhere he goes people want something from him. That level of celebrity I’m not really interested in,” he said by phone from the New York home he shares with filmmaker wife Tamara Jenkins (The Slums of Beverly Hills).

With the craziness of Sideways now subsided and Payne due to return soon from a month-long sojourn in Paris, where he shot a vignette for the I Love Paris omnibus film, he and Taylor will once again engage their joint muse. So far, they’re being coy about what they’ve fixed as their next project. It may be the political, Altmanesque story they’ve hinted at. Or something entirely else. What is certain is that a much-anticipated new Payne-Taylor creation will be in genesis.

Taylor’s an enigma in the public eye, but he is irreducibly, inescapably one half of a premier writing team that shows no signs of running dry or splitting up. His insights into how they approach the work offer a vital glimpse into their process, which is a kind of literary jam session, game of charades and excuse for hanging out all in one. They say by the time a script’s finished, they’re not even sure who’s done what. That makes sense when you consider how they fashion a screenplay — throwing out ideas over days and weeks at a time in hours-long give-and-take riffs that sometimes have them sharing the same computer monitor hooked up to two keyboards.

Their usual M.O. finds them talking, on and on, about actions, conflicts, motivations and situations, acting out or channeling bits of dialogue and taking turns giving these elements form and life on paper.

”After we’ve talked about something, one of us will say, ‘Let me take a crack at this,’ and then he’ll write a few pages. Looking at it, the other might say, ‘Let me try this.’ Sometimes, the person on the keyboard is not doing the creative work. They’re almost inputting what the other person is saying. It’s probably a lot like the way Alexander works with his editor (Kevin Tent), except we’re switching back and forth being the editor.”

For each writer, the litmus test of any scene is its authenticity. They abhor anything that rings false. Their constant rewrites are all about getting to the truth of what a given character would do next. Avoiding cliches and formulas and feel-good plot points, they serve up multi-shaded figures as unpredictable as real people, which means they’re not always likable.

”I think it’s true of all the characters we write that there’s this mixture of things in people. Straight-ahead heroes are just really boring to us because they don’t really exist,” said Taylor, whose major influences include the humanist Czech films of the 1960s. “I think once we fall in love with the characters, then it’s really just about the characters for us. We have the best time writing when the characters are leading us somewhere and we’re not so much trying to write about some theme.”

Sideways’ uber scene, when Miles and Maya express their longing for each other via their passion for the grape, arose organically.

“We didn’t labor any longer over that scene than others,” he said. “What happened was, in our early drafts we had expanded on a speech Miles has in the book (Rex Pickett’s novel) and in later drafts we realized Maya should have her own speech. At the time we wrote those speeches we had no idea how important they would turn out to be. It was instinctive choice to include them, not something calculated to fill a gap in a schematic design.”

Writer/director Tamara Jenkins and writer/producer Jim Taylorattend ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ intro at MoMA on February 15, 2008 in New York City.

He said their scripts are in such “good shape” by the time cameras roll that little or no rewriting is done on set. “Usually we’ll make some minor changes after the table reading that happens right before shooting.” Taylor said Payne asks his advice on casting, locations, various cuts, music, et cetera.

Their process assumes new colors when hired for a script-doctor job (Meet the Parents, Jurassic Park III), the latest being I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry.

“With those projects we’re trying to accommodate the needs of a different director and we generally don’t have much time, so we don’t allow problems to linger as long as we would, which is good practice,” said Taylor. “It’s good for us to have to work fast. We’ll power through stuff, where we might let it sit longer and just let ourselves be stuck.”

Ego suppression explains in part how they avoid any big blow ups.

”I think it’s because both of us are interested in making a good movie more than having our own ideas validated,” Taylor said. “So we are able to, hopefully, set our egos aside when we’re working and say, ‘Oh, that’s a good idea,’ or, ‘That’s a better idea.’ I think a lot of writing teams split up because they’re too concerned about protecting what they did as opposed to remembering what’s good for the script. We can work out disagreements without having any fallout from it. It’s funny. I mean, sometimes we do act like a married couple. There’s negotiations to be made. But mostly we just get along and enjoy working together.”

As conjurers in the idiom of comedy, he said, “I think our shared sensibilities are similar enough that if I can make him laugh or he can make me laugh, then we feel like we’re on the right track.”

Collaboration is nothing new for Taylor, a Pomona College and New York University Tisch School of the Arts grad, who’s directed a short as well as second unit work on Payne shoots (most of the 16 millimeter footage in Election) and is developing feature scripts for himself to direct.

”For me, I didn’t set out to be a screenwriter, I set out to be a filmmaker,” said Taylor, a former Cannon Films grunt and assistant to director Ivan Passer (Cutter’s Way). So did Alexander. And we kind of think of it all as one process, along with editing…People say everything is writing. Editing is writing and in a strange way acting is writing, and all that. Filmmaking itself is a collaborative medium. People drawn to filmmaking are drawn to working with other people. Sure, a lot of screenwriters do hole up somewhere so they’re not disturbed, but I’m not like that and Alexander’s not like that. I don’t like working on my own. I like to bounce ideas off people. Filmmaking demands it, as opposed to being a novelist or a painter, who work in forms that aren’t necessarily collaborative.”

Simpatico as they are, there’s also a pragmatic reason for pairing up.

”We just don’t like doing it alone and it’s less productive, too. And we sort of have similar ideas, so why not do it together? Even beyond that, it’s like a quantum leap in creativity. You’re just sort of inspired more to come up with something than if you’re just sitting there and hating what you’re doing. At least there’s somebody there going, ‘Oh, that’s good,’ or, ‘How do we do this?’ And you sort of stick with the problem as opposed to going off and cleaning out a drawer or something.”

Payne says scripting with someone else makes the writing process “less hideous.” For Taylor, flying solo is something to be avoided at all costs.

”I hate it. I really hate it. I mean, I do it, but it’s very slow and I don’t think it’s as good,” he said. “I’m getting Alexander’s input on something I’ve been working on for a long, long time on my own, a screenplay called The Lost Cause about a Civil War reenactor, and I expect it to became 50 percent better just because of working with him. We’ll essentially do with it what we do on a production rewrite.”

Lost Cause was part of a “blind deal” Taylor had with Paramount’s Scott Rudin, now at Disney. The fate of Taylor’s deal is unclear.

Writing with his other half, Taylor said, opens a script to new possibilities. “I’ll see it through different eyes when I’m sitting next to Alexander and maybe have ideas I wouldn’t otherwise.”

The pair’s operated like this since their first gig, co-writing short films for cable’s Playboy Inside Out series. The friends and one time roommates have been linked ever since. ”It’s pretty hard to extract the friendship from the partnership or vice versa. It’s all kind of parts of the same thing. We don’t end up seeing each other that much because we live in separate cities, unless we’re working together,” Taylor said. “So our friendship is a little bit dependent on our work life at this point, which is too bad.” However, he added there’s an upside to not being together all the time in the intense way collaborators interact, “It’s important to not get too overdosed on who you’re working with.”

He can’t imagine them going their separate ways unless there’s a serious falling out. ”That would only happen of we had personal problems with each other. Sometimes, people naturally drift apart, and we’re both working against that. We’re trying to make sure that it doesn’t just drift away, because that would be sad.”

Keeping the alliance alive is complicated by living on opposite coasts and the demands of individual lives/careers. But when Taylor talks about going off one day to make his own movies, he means temporarily. He knows Payne has his back. “He’s supportive of my wanting to direct. But I’m so happy working with him that if that were all my career was, I’d be a very lucky person.”