Archive

Next generation of North Omaha leaders eager for change: New crop of leaders emerging to keep momentum going

North Omaha’s prospects are looking up, even as longstanding problems remain a drag on the largely African-American community, and a strong, established leadership base in place is a big part of the optimism for the area’s continued revival. These leaders are in fact driving the change going on. Working side by side or coming up right behind that veteran leadership cohort is a group of emerging leaders looking to put their own stamp on things. The following article for The Reader (www.thereader.com) takes a look at this next generation of North Omaha leaders and their take on opportunities and vehicles for being change agents.

Thomas Warren and Julia Parker

Next generation of North Omaha leaders eager for change: New crop of leaders emerging to keep momentum going

©by Leo Adam Biga

Now appearing in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

If redevelopment plans for northeast Omaha come to full fruition then that long depressed district will see progress at-scale after years of patchwork promises. Old and new leaders from largely African-American North Omaha will be the driving forces for change.

A few years and projects into the 30-year, $1.4 billion North Omaha Revitalization Village Plan, everyone agrees this massive revival is necessary for the area to be on the right side of the tipping point. The plan’s part of a mosaic of efforts addressing educational, economic, health care, housing, employment disparities. Behind these initiatives is a coalition from the private and public sectors working together to apply a focused, holistic approach for making a lasting difference.

Key contributors are African-American leaders who emerged in the last decade to assume top posts in organizations and bodies leading the charge. Empowerment Network Facilitator Willie Barney, Douglas Country Treasurer John Ewing, Urban League of Nebraska Executive Director Thomas Warren and Omaha City Councilman Ben Gray are among the most visible. When they entered the scene they represented a new leadership class but individually and collectively they’ve become its well-established players.

More recently, Neb. State Senator Tanya Cook and Omaha 360 Director Jamie Anders-Kemp joined their ranks. Others, such as North Omaha Development Corporation Executive Director Michael Maroney and former Omaha City Councilwoman and Neb. State Sen. Brenda Council, have been doing this work for decades.

With so much yet to come and on the line, what happens when the current crop of leaders drops away? Who will be the new faces and voices of transformation? Are there clear pathways to leadership? Are there mechanisms to groom new leaders? Is there generational tension between older and younger leaders? What does the next generation want to see happen and where do they see things headed?

Some North Omaha leaders

Transformational Leadership

The Reader asked veteran and emerging players for answers and they said talent is already in place or poised to assume next generation leadership. They express optimism about North O’s direction and a consensus for how to get there. They say leadership also comes in many forms. It’s Sharif Liwaru as executive director of the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation, which he hopes to turn into an international attraction. It’s his artist-educator wife Gabrielle Gaines Liwaru. Together, they’re a dynamic couple focused on community betterment. Union for Contemporary Arts founder-director Brigitte McQueen, Loves Jazz and Arts Center Executive Director Tim Clark and Great Plains Black History Museum Board Chairman Jim Beatty are embedded in the community leading endeavors that are part of North O’s revival.

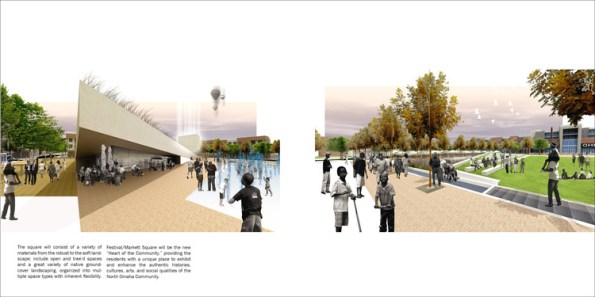

Seventy-Five North Revitalization Corp. Executive Director Othello Meadows is a more behind-the-scenes leader. His nonprofit has acquired property and finished first-round financing for the Highlander mixed-used project, a key Village Plan component. The project will redevelop 40 acres into mixed income housing, green spaces and on-site support services for “a purpose-built” urban community.

Meadows says the opportunity to “work on a project of this magnitude in a city I care about is a chance of a lifetime.” He’s encouraged by the “burgeoning support for doing significant things in the community.” In his view, the best thing leaders can do is “execute and make projects a reality,” adding, “When things start to happen in a real concrete fashion then you start to peel back some of that hopelessness and woundedness. I think people are really tired of rhetoric, studies and statistics and want to see something come to life.” He says new housing in the Prospect Hill neighborhood is tangible positive activity.

Othello Meadows

Meadows doesn’t consider himself a traditional leader.

“I think leadership is first and foremost about service and humility. I try to think of myself as somebody who is a vessel for the hopes and desires of this neighborhood. True leadership is service and service for a cause, so if that’s the definition of leadership, then sure, I am one.”

He feels North O’s suffered from expecting leadership to come from charismatic saviors who lead great causes from on high.

“In my mind we have to have a different paradigm for the way we consider leadership. I think it happens on a much smaller scale. I think of people who are leaders on their block, people who serve their community by being good neighbors or citizens. That’s the kind of leadership that’s overlooked. I think it has to shift from we’ve got five or six people we look to for leadership to we’ve got 500 or 600 people who are all active leaders in their own community. It needs to shift to that more grassroots, bottom-up view.”

Where can aspiring North O leaders get their start?

“Wherever you are, lead,” John Ewing says. “Whatever opportunities come, seize them. Schools, places of worship, neighborhood and elected office all offer opportunities if we see the specific opportunity.”

“They need to get in where they fit in and grow from there,” says Dell Gines, senior community development advisor, Omaha Branch at Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Empowerment Network board member and Douglas County Health Department health educator Aja Anderson says many people lead without recognition but that doesn’t make them any less leaders.

“There are individuals on our streets, in our classrooms, everywhere, every day guiding those around them to some greater destiny or outcome,” Anderson says.

Meadows feels the community has looked too often for leadership to come from outside.

“A community needs to guide its own destiny rather than say, ‘Who’s going to come in from outside and fix this?'”

He applauds the Empowerment Network for “trying to find ways to help people become their own change agents.”

Carver Bank Interim Director JoAnna LeFlore is someone often identified as an emerging leader. She in turn looks to some of her Next Gen colleagues for inspiration.

“I’m very inspired by Brigitte McQueen, Othello Meadows and Sharif Liwaru. They all have managed to chase their dreams, advocate for the well-being of North Omaha and maintain a professional career despite all of the obstacles in their way. You have to have a certain level of hunger in North Omaha in order to survive. What follows that drive is a certain level of humility once you become successful. This is why I look up to them.”

LeFlore is emboldened to continue serving her community by the progress she sees happening.

“I see more creative entrepreneurs and businesses. I see more community-wide events celebrating our heritage. I see more financial support for redevelopment. I feel my part in this is to continue to encourage others who share interest in the growth of North Omaha. I’ve built trusting relationships with people along the way. I am intentional about my commitments because those relationships and the missions are important to me. Simply being a genuine supporter, who also gets her hands dirty, is my biggest contribution.

“Moving forward, I will make an honest effort to offer my expertise to help build communication strategies, offer consultations for grassroots marketing and event planning and be an advocate for positive change. I am also not afraid to speak up about important issues.”

If LeFlore’s a Next Gen leader, then Omaha Small Business Network Executive Director Julia Parker is, too. Parker says, “There is certainly a changing of the guard taking place throughout Omaha and North O is not an exception. Over the next several years, I hope even more young professionals will continue to take high level positions in the community. I see several young leaders picking up the mic.” She’s among the new guard between her OSBN work and the Urban Collaborative: A Commitment to Community group she co-founded that she says “focuses on fostering meaningful conversation around how we can improve our neighborhoods and the entire city.”

Parker left her hometown for a time and she says, “Leaving Omaha changed my perspective and really prompted me to come home with a more critical eye and a yearning for change.”

Like Parker, Othello Meadows left here but moved back when he discerned he could make a “meaningful” impact on a community he found beset by despair. That bleak environment is what’s led many young, gifted and black to leave here. Old-line North O leader Thomas Warren says, “I am concerned about the brain drain we experience in Omaha, particularly of our best and brightest young African-Americans students who leave. We need to create an environment that is welcoming to the next generation where they can thrive and strive to reach their full potential.” Two more entrenched leaders, John Ewing and Douglas County Commissioner Chris Rodgers, are also worried about losing North O’s promising talents. “We have to identify, retain and develop our talent pool in Omaha,” Ewing says.

Tunette Powell

Omaha Schools Board member Yolanda Williams says leadership doors have not always been open to young transplants like herself – she’s originally from Seattle – who lack built-in influence bases.

“I had to go knock on the door and I knocked and knocked, and then I started banging on the door until my mentor John Ewing and I sat down for lunch and I asked, ‘How do younger leaders get in these positions if you all are holding these positions for years? How do I get into a leadership role if nobody is willing to get out of the way?’ They need to step out of the way so we can move up.

“It’s nothing against our elder leadership because I think they do a great job but they need to reach out and find someone to mentor and groom because if not what happens when they leave those positions?”

Ewing acknowledges “There has been and will always be tension between the generations,” but he adds, “I believe this creative tension is a great thing. It keeps the so-called established leaders from becoming complacent and keeps the emerging leaders hungry for more success as a community. I believe most of the relationships are cordial and productive as well as collaborative. I believe everyone can always do more to listen. I believe the young professional networks are a great avenue. I also believe organizations like the Empowerment Network should reach out to emerging leaders to be inclusive.”

Author, motivational speaker and The Truth Hurts director Tunette Powell says, “It’s really amazing when you get those older leaders on board because they can champion you. They’ve allowed me to speak at so many different places.” Powell senses a change afoot among veteran leaders, “They have held down these neighborhoods for so long and I think they’re slowly handing over and allowing young people to have a platform. i see that bridge.” As a young leader, she says, “it’s not like I want to step on their toes. We need this team. It’s not just going to be one leader, it’s not going to be young versus old, it’s going to be old and young coming together.”

Yolanda Williams

In her own case, Yolanda Williams says she simply wouldn’t be denied, “I got tired of waiting. I was diligent, I was purpose-driven. It was very much networking and being places and getting my name out there. I mean, I was here to stay, you were not just going to get rid of me.”

LeFlore agrees more can be done to let new blood in.

“I think some established leaders are ignoring the young professionals who have potential to do more.”

Despite progress, Powell says “there are not enough young people at the table.” She believes inviting their participation is incumbent on stakeholder organizations. She would also like to see Omaha 360 or another entity develop a formal mentoring program or process for older leaders “to show us that staircase.”

Some older leaders do push younger colleagues to enter the fray.

Shawntal Smith, statewide administrator for Community Services for Lutheran Family Services of Nebraska, says Brenda Council, Willie Barney and Ben Gray are some who’ve nudged her.

“I get lots of encouragement from many inside and outside of North Omaha to serve and it is a good feeling to know people trust you to represent them. It is also a great responsibility.”

Everyone has somebody who prods them along. For Tunette Powell, it’s Center for Holistic Development President-CEO Doris Moore. For Williams, it’s treasurer John Ewing. But at the end of the day anyone who wants to lead has to make it happen. Williams, who won her school board seat in a district-wide election, says she overcame certain disadvantages and a minuscule campaign budget through “conviction and passion,” adding, “The reality is if you want to do something you’ve got to put yourself out there.” She built a coalition of parent and educator constituents working as an artist-in-residence and Partnership 4 Kids resource in schools. Before that, Williams says she made herself known by volunteering. “That started my journey.”

Powell broke through volunteering as well. “I wasn’t from here, nobody knew me, so I volunteered and it’s transformed my life,” says the San Antonio native.

“The best experience, in my opinion, is board service,” OSBN’s Julia Parker says. “Young leaders have a unique opportunity to pull back the curtain and see how an organization actually functions or doesn’t. It’s a high level way to cut your teeth in the social sector.”

JoAnna LeFlore, ©omahamagazine.com

Chris Rodgers, director of community and government relations at Creighton University, agrees: “I think small non-profits looking for active, conscientious board members are a good start. Also volunteering for causes you feel deeply about and taking on some things that stretch you are always good.”

The Urban League’s Thomas Warren says, “We have to encourage the next generation of leaders to invest in their own professional growth and take advantage of leadership development opportunities. They should attend workshops and seminars to enhance their skills or go back to school and pursue advanced degrees. Acquiring credentials ensures you are prepared when opportunities present themselves.”

Gaining experience is vital but a fire-in-the-belly is a must, too. Yolanda Williams says she was driven to serve on the school board because “I felt like I could bring a voice, especially for North Omaha, that hadn’t yet been heard at the table as a younger single parent representing the concerns and struggles of a lot of other parents. And I’m a little bit outspoken I say what I need to say unapoligitically.”

Powell says young leaders like her and Williams have the advantage of “not being far removed from the hard times the people we’re trying to reach are experiencing.” She says she and her peers are the children of the war on drugs and its cycle of broken homes. “That’s a piece of what we are, so we get it. We can reach these young people because our generation reflects theirs. I see myself in so many young people.”

Just a few years ago Powell had quit college, was on food stamps and didn’t know what to do with her life. “People pulled me up, they elevated me, and I have to give that back,” she says. In her work with fatherless girls she says “what I find is you’ve got to meet them where they’re at. As younger leaders we’re not afraid to do that, we’re not afraid to take some risks and do some things differently. We’re seeing we need something fresh. Creativity is huge. When you look at young and old leaders, we all have that same passion, we all want the same thing, but how we go about it is completely different.”

Powell says the African-American Young Professionals group begun by fellow rising young star Symone Sanders is a powerful connecting point where “dynamic people doing great things” find a common ground of interests and a forum to network. “We respect each other because we know we’re all going in that direction of change.”

Sanders, who’s worked with the Empowerment Network and is now communications assistant for Democratic gubernatorial candidate Chuck Hassebrook, says AAYP is designed to give like-minded young professionals an avenue “to come together and get to know one another and to be introduced in those rooms and at those tables” where policy and program decisions get made.

Aja Anderson believes Next Gen leaders “bridge the gap,” saying, “I think this generation of leaders is going to be influential and do exceptionally well at creating unity and collaboration among community leaders and members across generations. We’re fueled with new ideas, creativity and innovation. Having this group of individuals at the table will certainly make some nervous, others excited and re-ignite passion and ideas in our established group.”

John Ewing

County treasure John Ewing sees the benefit of new approaches. “I believe our emerging leaders have an entrepreneurial spirit that will be helpful in building an African-American business class in Omaha.”

While Williams sees things “opening up,” she says, “I think a lot of potential leaders have left here because that opportunity isn’t as open as it should be.”

Enough are staying to make a difference.

“It’s exciting to see people I’ve known a long time staying committed to where we grew up,” 75 North’s Othello Meadows says. “It’s good to see other people who at least for awhile are going to play their role and do their part.”

Shawntal Smith of Lutheran Family Services is bullish on the Next Gen.

“We are starting to come into our own. We are being appointed to boards and accepting high level positions of influence in our companies, firms, agencies and churches. We are highly educated and we are fighting the brain drain that usually takes place when young, gifted minorities leave this city for more diverse cities with better opportunities. We are remaining loyal to Omaha and we are trying to make it better through our visible efforts in the community.

“People are starting to recognize we are dedicated and our opinions, ideas and leadership matter.”

Old and young leaders feel more blacks are needed in policymaking capacities. Rodgers and Anderson are eager to see more representation in legislative chambers and corporate board rooms.

Warren says, “I do feel there needs to be more opportunities in the private sector for emerging leaders who are indigenous to this community.” He feels corporations should do more to identify and develop homegrown talent who are then more likely to stay.

Shawntal Smith describes an added benefit of locally grown leaders.

“North Omahans respect a young professional who grew up in North Omaha and continues to reside in North Omaha and contribute to making it better. Both my husband and I live, shop, work, volunteer and attend church in North Omaha. We believe strongly in the resiliency of our community and we love being a positive addition to North Omaha and leaders for our sons and others to model.”

With leadership comes scrutiny and criticism.

“You have to be willing to take a risk and nobody succeeds without failure along the way to grow from,” Rodgers says. “If you fail, fail quick and recover. Learn from the mistake and don’t make the same mistakes. You have to be comfortable with the fact that not everybody will like you.”

Tunette Powell isn’t afraid to stumble because like her Next Gen peers she’s too busy getting things done.

“As Maya Angelou said, ‘Nothing will work unless you do,’ I want people to say about me, ‘She gave everything she had.'”

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.wordpress.com.

Sisters of song: Kathy Tyree connects with Ella Fitzgerald; Omaha singer feels kinship to her stage alter ego

©by Leo Adam Biga

Now appearing in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Ella, the dramatic musical revue of the life of American songbook diva Ella Fitzgerald at the Omaha Community Playhouse, reveals the anguish behind the legendary performer’s sweet voice and carefree persona.

Call it kismet or karma, but the woman portraying her is veteran Omaha chanteuse Kathy Tyree, whose ebullient, easy-going public face has similarly disguised her own torment.

The high points surely outweigh the low points in their respective lives but Tyree’s experienced, much as Ella did, her share of failed relationships, including two divorces, and myriad financial struggles.

“I’m in a much better place now,” Tyree says.

Known for her bright spirit and giving heart, Tyree’s usually worked a regular job to support her and her son. Currently, she’s program manager at Omaha Healthy Start. A few years ago she used all her savings and 401K to launch her own production company and after a rousing start one bad show broke the business.

The enigmatic Fitzgerald died in 1996 at age 79 with few outside her inner circle knowing her private travails because her handlers sanitized her regal image as the First Lady of Song.

As Tyree researched Fitzgerald’s life for the role, which director Susie Baer Collins offered without an audition, she identified with what Ella did to separate, if not always reconcile, her private and public sides.

“She was very weak and very strong at the same time,” Tyree says of Ella. “She had all these secrets and these hurts, all this internal pain, but she always held it together. She was at the top, she was international, she was the goddess of scat.”

Fitzgerald was respected for her dignified demeanor, the purity of her well-modulated voice and her perfect elocution, though some criticized her for being too precise, too pristine, too white. All of it helped to popularize jazz.

Tyree says the adoration that flowed Ella’s way was due to her talent but also to “how she carried herself as a black woman,” adding, “She wasn’t Lady Day (Billie Holiday), she wasn’t drinking and popping pills and going through all these changes publicly. That takes a lot.”

Before getting the role Tyree was lukewarm about the singer. Her favorite female artists were Diana Ross, Patti Labelle and Cher. After months listening to the Ella canon, Tyree says ,”I have a completely different appreciation for her. Now I am a fan. This woman was a walking instrument. She could do just amazing things with her voice.”

Because the script peels back the layers of myth around Fitzgerald’s antiseptic image, Tyree now feels connected to the real woman behind the silky voice and prim and proper mask

“There’s so much more to her than was allowed to be shared with the world. She definitely has a story, she definitely was singing from a place of pain. In rehearsals I began seeing a lot of the parallels between us.”

Both grew up fatherless and both lost a sister. By their mid-teens both were mixed up in the wrong crowd. Just as performing saved Fitzgerald, it gave the “rebellious” Tyree a purpose and discipline she’d lacked. She began singing in church, at Morningstar Baptist, where she still attends today, and at Omaha Technical High School. Outside of her faith, performing is Tyree’s spiritual sanctuary.

“For me theater and music are my therapy but from everything I’ve learned about Ella it was more like her drug. For me it takes me to another place and it gives me a peace and a calm. I leave everything outside. It’s like this is a whole other world.”

Just as performing helped Tyree cope with insecurities, she guesses it did so for Ella, whose character in the show says, “I’m always OK when I’m on the stage. When I’m not working, I turn off, I get lost.”

Tyree’s usual reticence about her own turmoil isn’t to protect a well-manufactured facade, but a personal credo she inherited.

“I shared with Susie (Baer Collins) in a read-through that in my family we have a rule – you never look like what you’re going through. Though I’ve been through a lot, I’ve had a lot of heartbreak and heartache, I never look like what I’m going through, and that was Ella.

“It’s a pride thing. I was raised by strong black women. These women had to work hard. Nobody had time for that crying and whining stuff.

It was, ‘Straighten your face up, get yourself together, keep it moving.'”

She says what she doesn’t like about Ella is “the very same thing I don’t like in myself,” adding, “Ella didn’t have enough respect for herself to know what she deserved. She didn’t have those examples, she didn’t have a father. People always say little boys need their fathers, well little girls need their fathers. too. They need somebody to tell them they’re beautiful. They deserve somebody in their life that isn’t going to abuse them. When you don’t have that you find yourself hittin’ and missin’, trying to figure it out, searching for that acceptance and that love. That’s very much our shared story.”

That potent back story infuses Tyree’s deeply felt interpretations of Fitzgerald standards. Tyree’s singing doesn’t really sound anything like her stage alter ego but she does capture her heart and soul.

Tyree, a natural wailer, has found crooning ballad and scat-styles to conjure the spirit of Ella. Tyree makes up for no formal training and the inability to read music with perfect pitch and a highly adaptable voice.

“My voice is very versatile and my range is off the charts,” Tyree says matter-of-factly. “I can sing pretty much anything you put in front of me because it’s all in my ear. I’ve been blessed because they (music directors) can play it one time and I get it.”

She considers herself a singer first and an actress second, but in Ella she does both. She overcame initial doubts about the thick book she had to learn for the part.

“It’s a lot of lines and a lot of acting and a lot of transitions because I’m narrating her life from 15 years-old to 50.

But after months of rehearsal Tyree’s doing what she feels anointed to do in a space where she’s most at home.

“This is where I get to be lost and do what I do best, this is where I don’t miss. I think it’s because it’s coming from a sincere place. My number one goal is that everybody in the audience leaves blessed. I want to pour something out of me into them. I want ’em to leave on a high. It’s not about me when I’m on stage. This is God-given and there’s a lot of responsibility that comes with it to deliver.”

This popular performer with a deep list of musical theater credits (Ain’t Misbehavin’, Beehive) feels she’s inhabiting the role of a lifetime and one that may finally motivate her to stretch herself outside Omaha.

“I’m still like blown away they asked me to come do this show. I still have goals and dreams and things I want to do. As you go through your journey in life there’s things that hinder those goals and dreams and they cause you to second guess and doubt yourself – that maybe I don’t have what it takes. I’m hoping this will instill in me the courage to just go for it and start knocking on some of those doors.”

Ella continues through March 30. For times and tickets, visit http://www.omahacommunity playhouse.com.

Patique Collins Finds the Right Fit

Patique Collins has got it going on. She is a high achieving African American woman with an alluring combination of physical besuty, spiritual enlightenment, business savvy, and passion for her life’s calling. The Omaha, Neb. fitness trainer loves empowering people to positively chnage their lives. In the short time between leaving a successful corporate career to starting her own buisness, she’s expertly branded her Right Fit company to grow its client base and to garner media attention. I discovered her through her heady, consistent use of Facebook as a social media marketing platform that gets her name and face and brand out there, not just through the usual promotional methods but through inspiring before and after pictorials and testimonials that demonstrate the difference that Right Fit workouts make and through affirmations she writes and shares to offer encouraging life lessons. My profile of Patique is for Omaha Magazine.

Patique Collins Finds the Right Fit

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in Omaha Magazine

In 2011 Patique Collins left a two-decade corporate career to open a fitness gym. Two-and-a-half years later her Right Fit at 11067 West Maple Rd. jumps with clients.

Under her watchful eye and upbeat instruction, members do various aerobic and anaerobic exercises, kickboxing and Zumba included, all to pulsating music, sometimes supplied by DJ Mista Soul. She helps clients tone their bodies and build cardio, strength and flexibility.

The sculpted Omaha native is a longtime fitness convert. Nine years ago she added weight training to her running regimen and got serious about nutrition. She’d seen too many loved ones suffer health problems from poor diet and little exercise. The raw vegan describes her own workouts as “intense” and “extreme.”

She pushes clients hard.

“I really want to help every single person that comes in reach their maximum potential, and that is a big responsibility,” she says. “if you don’t give up on you, I won’t. I will do whatever I can to help you earn your goals if you’re ready to.”

She’s known to show up at your job if you skip class.

“There’s accountability here at Right Fit. I’m very passionate about my clients.”

She believes the relationships she builds with clients keeps them coming back.

“People will tend to stay if you develop a relationship and work towards results.”

Her gym. like her Facebook page, is filled with affirmations about following dreams. being persistent and never quitting.

“I think positivity is a part of my DNA.”

She keeps things fun with theme workouts, sometimes dressing as a superhero.

A huge influence in her life was her late maternal grandmother, Faye Jackson, who raised her after Collins and her siblings were thrown into the foster care system. “My grandmother told me I could be whatever I wanted to be and made me believe it.” Collins went on to attain multiple college degrees.

Motivated to help others, she made human resources her career. She and her then-husband Anthony Collins formed the Nothing But Foundation to assist at-risk youth. While working as a SilverStone Group senior consultant and as Human Resources Recruitment Administrator for the Omaha Public Schools she began “testing the waters” as a trainer conducting weekend fitness boot camps..

Stepping out from the corporate arena to open her own gym took a leap of faith for this now divorced mother of two small children..

“This is a lot of work. I am truly a one-woman show. Sometimes that can be challenging.

She’s proud to be a successful female African-American small business owner and humbled by awards she’s received for her business and community achievements.

Right Fit is her living but she works hard maintaining the right balance. Family and faith are er top priorities.

This former model, who’s emceed events and trained celebrities (Usher and LL Cool J), wants to franchise her business, produce workout videos and be a mind-body fitness national presenter.

She believes opportunities continue coming her way because of her genuine spirit.

“There’s some things you can’t fake and being authentic is one of them. I’m doing what I want to do, I think it’s my ministry. Everybody has their gifts, and this is mine.

I’m able to influence people not just physically but mentally.”

Wanda Ewing Exhibit: Bougie is as Bougie Does

Omaha has lost one of its most respected and exibited artists, Wanda Ewing. As a memoriam to her, I am posting for the first on this blog a story I did about an exhibition of hers some years ago. When the assignment came I already knew her work and like most folks who experienced it I was quite impressed. I very much wanted to do a full-blown profile of her but I only got the go-ahead to focus on the exhibit. She was very gracious with her time in helping me understand where she was coming from in her work. Her untimely death has taken most of us, even those who knew her far better than me, by complete surprise. Facebook posts about her are filled with shock and admiration.

You can appreciate her work at http://www.wandaewing.com.

Wanda Ewing Exhibit: Bougie is as Bougie Does

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Wanda Ewing is at it again. The Omaha printmaker known for her provocative spin on African-American images has created a sardonic collection of reductive linocuts and acrylic paintings that considers aspects of beauty, race and social status. The work has been organized in the solo exhibition, Bougie, at the Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery in Lincoln, where it continues through December 2.

The title comes from a slang term, derived from the French word bourgeois, used in the black community as a put down for anyone acting “uppity,” said Ewing, an assistant professor in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. “It speaks to the level of acceptance due to your social and economic background, your physical appearance, all of it.”

She explores bougie through the template of popular magazine culture and its vacuous lifestyle advice. The heart of the show is 12 faux glossy covers, each a reductive linocut with vinyl lettering on acetate, depicting a slick monthly women’s mag of her imagination called Bougie. The garish covers are inspired by Essence and other Cosmo knockoffs whose content places style over substance.

Among the “bougie markers,” as Ewing calls them, are black cover girls with straight or long hair and “story tags” that embody those things compelling to bougie women — shopping, how to lose weight, money and getting a man. Some of the teasers get right to the point: “Not Hood enough? 25 ways to get ghetto fabulous.” Another reads, “It’s what’s on the outside that counts.” Among the many double entendres are, “Tom Tom Club, back on the scene” and “I’m dreaming of a white Christmas.”

“I wanted to achieve something that was funny to read, but had some grit to it,” she said.

Each “issue” is adorned by a head and shoulders illustration of a black glamazoid female, the features made just monstrous enough that it’s hard to recognize the real-life celebs Ewing based them on. One vixen is based on home girl Gabrielle Union. Other iconic models include Halle Berry, Mariah Carey, Beyonce, Tyra Banks, Janet Jackson, Eve, Star Jones and Queen Latifah.

Ewing “distorted” the images, in part, she said, as “I didn’t want them to be necessarily commentary on the celebrity, because it’s not about that,”

These cover girls represent impossible beauty standards and thus, in Ewing’s hands, become primping, leering creatures for the fashionista industry. Like the figures in her popular Pinup suite, she said, bougie women “are not shrinking violets.”

Contrasted with the plastic mag images are big, bold, beautiful head portraits of more realistically rendered black women and their different hair styles — bald, straight, permed, afroed, cornrowed — executed in intense acrylic and latex on canvas. These are celebratory tributes of black womanhood. The figures-colors jump out in the manner of comic book or billboard art. “I’m still holding onto being influenced by Pop Art,” Ewing said. “I love color. I’m not afraid of color.” The Hair Dresser Dummy works, as she calls them, are a reaction to the stamped-out glam look of the old Barbie Dress Doll series. Ewing’s “dolls” embody the inner and outer beauty of black women, distinct features and all. We’re talking serious soul, here.

There are also fetching portraits of women that play with the images of Aunt Jemima and Mammy and that refer to German half-doll figures Ewing ran across. Another painting, Cornucopia, is of a reposed woman’s opened legs amid a cascade of flowers — an ode to the source of life that a woman’s loins represent.

All these variations on the female form also comment on how “the art world likes to celebrate women,” she said, “especially if they’re naked and in pieces.”

Bougie examines women as objects and the whole “black is-black ain’t” debate that Ewing’s work often engages. Glam mags help inform the discussion. Ewing said black models were once shades darker and displayed kinkier hair than today, when they have a decidedly more European appearance. “I grew up looking at these images and felt bad because as hard as I tried, I couldn’t achieve what was being shown,” she said. At least before, she said, publications offered “a variety of the ways black women looked. Now, these magazines idealize the same type of woman with the same kind of features. I find that interesting and damaging on so many levels.”

Like the figures in her Pinup series, Bougie’s women are too self-possessed or confident to care what anyone thinks of them.

Leave it to a master satirist, Omaha author Timothy Schaffert, to put Ewing’s new work in relief. In an essay accompanying the show, he comments:

“The women…demonstrate a giddy indifference to their objectification, defying any interpretations other than the ones they choose to convey. See what you want to see, the women seem to be saying. You can’t change who I am, they taunt. Ewing portrays women in the act of posing, women possibly conscious of their degradation yet nonetheless seducing us with their self confidence. For Ewing’s women, the beauty myth becomes just another beauty mark…

“And yet the politics of fashion are what give Ewing’s work its sinister and satirical bent. Just beyond the coy winks and the toothpaste-peddling smiles and curve-hugging skirts of these fine black women is the sense that the images aren’t just about them” but about “the various co-conspirators in the invention of glamour. In Ewing’s work, black women assert themselves into the commercial, white-centric iconography of prettiness, and the result is at times funny, at times sad, at times grotesque, but often charming. Her women rise above the didactic, each one becoming a character in her own right, in full control of her lovely image.”

In the final analysis, beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

“Although this work is coming from an artist who is black, it is not limited to just the black community,” Ewing said. “Ultimately, the work is about beauty. That’s a conversation everyone can contribute to.”

A conversation is exactly what her work will provoke.

The Sheldon Gallery is located at 12th & R Streets. Admission is free. For gallery hours, call 402.472.2461 or visit www.sheldonartgallery.org.

Related articles

- Bougie… Insult or Badge of Honour? (crazyramblingsofaconversatingadult.wordpress.com)

- Black women need more self esteem. (blacksforabetterlife.wordpress.com)

Gray Matters: Ben and Freddie Gray fight the good fight helping young men and women find pathways to success

Omaha’s African-American community has some power couples in John and Viv Ewing; Willie and Yolanda Barney; Dick and Sharon Davis, among others, but the couple with the broadest reach may be Ben and Freddie Gray. He serves on the Omaha City Council. She’s president of the Omaha Public Schools Board of Education. That’s really having your fingers on the pulse of Omaha. Ben is someone I use as a source from time to time for stories I write about North Omaha and he is the subject of an extensive profile you’ll find on this blog. Freddie is someone I’ve just begun to know and I expect I’ll be interviewing and profiling her again before too long. They both have compelling stories and individually and collectively they are dynamic people making a difference wherever they serve and it just so happens their passions allign in boosting urban, inner city North Omaha through a variety of community, youth, and education initiatives.

Gray Matters: Ben and Freddie Gray Fight the Good Fight Helping Young Men and Women Find Pathways to Success

©by Leo Adam Biga

To appear in the August edition of the New Horizons

If you follow local news then you can’t help know the names Ben Gray and Freddie Gray. What you may not know is that they are married.

He’s instantly recognizable as a vocal Omaha City Councilman (District 2). He’s also a prominent player in the Empowerment Network, One Hundred Black Men and other community initiatives. He was a public figure long before that as a KETV photojournalist and the activist-advocate executive producer and host of the public affairs program Kaleidoscope, which weekly found him reeling against injustice.

Until recently his wife wasn’t nearly as well known, though in certain circles she was tabbed a rising star. She actually preceded Ben in public service when appointed to the Douglas County Board of Health. At the time she was office manager at NOVA, a mental health treatment facility. Along with Ben she co-chaired the African-American Achievement Council. She was also a paid administrator with the organization, which works closely with the Omaha Public Schools. It’s not the first time the couple worked in tandem. They have a video production business together, Project Impact. He produces-directs. She’s in charge of continuity.

She’s also worked as a strategic planning and management consultant.

Her longstanding interest in education led her to volunteer with the Omaha Schools Foundation and serve as a member of the student assignment plan accountability committee. The Grays were vocal proponents of the “one city, one school district” plan. Her public stature began to rise when she replaced Karen Shepard on the Omaha Public Schools Board of Education in 2008. She’s since become board president. The demands of the position leave little time for consulting work, which she misses, but she may have found her calling as a public servant leader.

“I like governance, I really do,” she says. “I have a strong feel for it.”

The size of responsibility she carries can be daunting.

“Sometimes I think about what a big job it is. The Omaha Public Schools district is one of the largest employers in the state and I’m the president of the board that’s in control of this entity. That’s kind of scary. I am not as confident as it comes across but I have a voice and I believe in using it for all these kids.”

Since assuming the presidency her public profile’s increased. In truth her private life was compromised as soon as she became Ben Gray’s wife in 1991. “It put me in the spotlight. There’s so many things that marrying somebody in the public eye does, and you don’t have a choice, you’re going to be public at that point.”

She suspects that sharing his notoriety has worked to her advantage. “There’s a lot of stuff Ben has afforded me the opportunity to do. Without him people wouldn’t know me from a can of paint and that’s probably how I would have lived my life and I would have been comfortable and OK with that.”

That each half of this pair holds a highly visible public service office makes them an Omaha power couple both inside and outside the African-American community.

Each represents hundreds of thousands of constituents and each deals with public scrutiny and pressure that gets turned up when controversy arises. That was the case last spring when he led the fight for the nondiscrimination ordinance the council eventually passed and Mayor Jim Suttle signed into law. In June Freddie found herself squarely in the media glare in the fallout of the scandal that erupted when sexually explicit emails OPS superintendent hire Nancy Sebring made came to light and she resigned under fire.

The couple makes sure to show their solidarity and support in crisis. Just as she turned out for city council hearings on the ordinance he attended the first school board meeting after the Sebring flap.

They act as sounding boards for each other when they feel they need to. “Sometimes we do,” he says, “but most of the time we don’t.” “If I want to bounce something off of him I can do that but I have my board members to do that with and he has his council members,” she says.

“If you’re married and you’re connected you know when it’s time to intervene and say let’s have a discussion about this,” he says. “Sometimes you just want to come home and veg out. The last thing you want is to talk about it. I don’t bring it home unless there’s a strategy, like when the Sebring thing happened we needed my expertise as a journalist, we needed legal counsel, we needed all of that, so that week was all about that.”

He’s proud of “how well she handled that situation, adding, “That was her defining moment.”

“A lot of times the conversation is after the fact,” she says, “because I can’t wait to talk to him to respond to the media when they’re in my face. I know if i need to I can reach out and he’s going to respond. The other thing is, we don’t always agree with each other. There’s been times when we’ve been able to change each other’s opinion or stand but not real often. But we don’t fight about it.”

The Grays have been making a difference in their individual and shared pursuits for some time now. The seeds planted during their respective journeys have borne fruit in the public-community service work they do, much of it centered around youth and education.

“We believe in children, I can tell you that, we believe strongly in children,” says Ben. Freddie calls it “a passion.”

Their work has earned them many awards.

They have seven adult children from previous marriages. They mentor more. By all accounts, they’ve made their blended family work.

“One of the things we did was we started having family dinners, and we started that before we got married,” says Freddie, “I still had one daughter at home with me. My older daughter was away from home. His children were still at home with their mom. Both of us were smart enough to figure out that with this new young person, let alone me, in the picture spending time with him that could be difficult. So we started having family dinner on Sunday and all seven of the kids would come. And we still do family dinner today.

“It was a wonderful way to bring our families together. And when people talk about a blended family, if you’ve ever done something like that and made it a tradition of your house for everyone to come together, it really and truly does blend them.”

Two of their kids live out-of-state now, as does one of their 11 grandchildren (they also have a great grandchild), but that still leaves a houseful.

“So generally on Sunday it’s a zoo time,” she says. “He loves it. He’s like they could all move back tomorrow. I’m the one that says no they cannot move back here and they have to go home now. They’re so close.”

Though born and reared in Cleveland, Ben’s made Omaha his home ever since the U.S. Air Force brought him here in the early 1970s. He’s built a life and career for himself and raised a family in his adopted hometown.

She’s an Omaha native but her father’s own Air Force career uprooted her and her six sisters for a time so that she did part of her growing up in Bermuda and in Calif. She returned in the early 1960s. The Omaha Central High School graduate raised a family here while working.

Whether in vote deliberations or media interviews each seems so poised and at home in this milieu of politics. As accomplished as they are today each comes from hard times far removed from these circumstances.

For example, the man Omahans know as Ben Gray is called by his street name “Butch” in his old stomping grounds of East Cleveland, where after suffering the loss of his working class parents at age 13 he fell into a life of organized crime. Numbers running, pimping, drug dealing. His extended family was well-entrenched in the black criminal underworld there. Its pull was something he avoided as long as his parents were alive but once gone he succumbed to a life that he’s sure would have ended badly.

Ben’s older sister Mary Thompson, whom he calls “my guardian angel,” and her husband took Ben and his younger brother Doug in and raised the boys right, modeling a fierce work ethic. But the call of the streets won out.

“The guys that I was dealing with, the guys that I knew, were real life gangsters. They do stories about these guys. Shondor Birns. Don King.

Before he was a fight promoter Don King used to run Cleveland. He ran all the drugs. And then he stomped a guy to death and when he went to prison his territory was split up, primarily between three different individuals and one of them was my uncle.”

Gray was arrested and sentenced to a youth incarceration center. After graduating a year late and near the bottom of his class he entered the military. His life’s never been the same since. “The Air Force changed who I was,” he says. “The military was my way out. Had I not joined I don’t think I would be alive. I was headed down a pretty dark path.” He graduated from aerial photography with honors. “People ask, ‘What was different?’ My response is always the same – discipline and expectations.”

That training is so ingrained, he says, “I’m disciplined about everything,” whether the self-pressed clothes he wears, the tidy home he keeps, the legislation he advances or the youth outreach he does.

“The intention of the military is to complete the mission and I complete the mission. When it came to the equal employment ordinance I had to complete the mission. When it came to the budget I had to complete the mission.”

He says leaving his old environment behind was the best thing he could have done.

“My sister readily tells folks all the time that while she hated to see me go she was in a lot of ways glad to see me go because she didn’t think I was going to make it if I stayed there.”

“That’s what she told me once,” says Freddie. “She said, ‘We’d thought he’d be dead or in jail.’ But they’re so proud of who he is today.”

When he goes back to visit relatives and friends, as he did with Freddie in July, he’s clearly a different person than the one who ran the streets as a youth but to them he’s still Butch. Oh, they see he’s transformed alright, but he’s Butch just the same.

“When we’re in Cleveland I immediately go back to referring to him as Butch,” says Freddie. “That’s what everybody knows him as. I don’t think anybody knows him as Ben.”

“It’s interesting when you leave a place and you come back to it,” he says, “because when I visited the corners I used to be at – even though a lot of the same people were still there – it wasn’t the same for me. They knew it and I knew it. A friend of mine told me, ‘This is not your place anymore,’ and he was right, it wasn’t. I didn’t fit.

“When I was doing the things I was doing I fit right in, as a matter of fact I ran the show for the most part.”

On a plane ride the couple made 20 years ago to spend Thanksgiving with his family in Cleveland Ben revealed his past for the first time to Freddie.

“I said, ‘Babe, when we get to Cleveland you’re going to hear some stories about me.'”

Then he asked her to marry him.

“Yeah, that plane ride was interesting,” she says, “and I still said yes.”

She has her own past.

Living in the South Omaha public housing projects called the Southside Terrace Garden Apartments, near the packinghouse kill floors her father worked after his military service ended, the future Mrs. Ben Gray grew up as Freddie Jean Stearns.

Life’s not always been a garden party for her. She got pregnant at age 17 and missed graduating with her senior class. She struggled as a young single mother before mentors helped her get her life together.

“It was not all a fairy tale life. The personal feeling of disappointment, not just letting my parents down but all those sisters behind me. That humbled me for a really long time.”

Long before marrying a celebrity and entering the public eye or serving on the school board, she quietly made young people her focus as a mother and mentor. She calls the young people under her wing “my babies.” Just as women helped guide her she does the same today.

She can identify with young single moms “who think their lives are over,” telling them, “I thought that was going to be it, that I was going to be on welfare for the rest of my life. I looked around at where I was, the projects, and I saw a lot of it around me. Mothers who had never been married. I was on public assistance for awhile and didn’t like that at all. I didn’t like the fact welfare workers could just come over my place and go through my stuff.”

She shares her experience of learning to listen to the right advice and to make better choices.

“I talk to these young women now, and I’m very open about it. I don’t preach.”

But she tries to do for them what women did for her. “I was blessed to have those women in my life. A number of them became my mentors. One of them was LaFern Williams. I’ll never forget her and Miss Alyce Wilson, the director of the Woodson Center in South Omaha. I spent so much time there. My big sister Lola Averett was another. There was a time when anything and everything she did I would do. She still models everything I could ever hope to do and to be.”

She says women like her sister, who worked at GOCA (Greater Omaha Community Action), along with Carolyn Green, Juanita James, Phyllis Evans, Sharon Davis and Beverly Wead Blackburn, among others, encouraged and inspired her. When Gray attended GOCA meetings she says she was at first too shy to speak up at but Lola and Co. helped her find her voice and confidence.

“They honestly would make me stand up and ask my question.”

“I’ve been very blessed in my life to have great female role models,” she says. “They took special care of me and others. They took care of the community, too. They made it safe. They protected and loved. These women touched a lot of lives.”

Those that survive continue fighting the good fight into their 70s and 80s. “They haven’t stopped. I wouldn’t even say they’ve slowed down.” She says when she sees them “you can bet your bottom dollar I’m in their ear saying, ‘I’m making you proud, I’m doing the right thing.'” It’s what Freddie’s babies do when they’re around her. All of it in the each-one-to-teach-one tradition.

“I’ve always had the passion for those who are behind me, young people. I just collect them, I don’t know what else to say. Anyone who really knows me knows that I talk about my babies. And they know who they are and they know what I expect from them. I can’t tell you how they’re selected, I don’t know how. But there is that group and they are my babies and I love them with all my heart.

‘I’ve told them, ‘My expectations are you’ve got to take care of Miss Freddie when she’s old.’ They laugh at that. But I need them to take care of me. They’re going to be my doctor, my mechanic, my attorney. And then they get it, they understand what I’m telling them. That they’re going to take care of me because I can’t do it forever. So they’re going to have to do these things, they’re going to need to be on the board of health, on the school board, work at NOVA. They need to take care of the world. They know that’s my expectation.”

She is a wise elder and revered Big Mama figure in their lives.

“When they see me they call me Mama Freddie or say, ‘How you doin’ Mama Freddie?'”

She recently lost one of her “babies.” When she got the news, she says, “it knocked me to my knees and I’m not talking figuratively. I was walking down the hall looking at Facebook on my phone when I saw it. I was very thankful Ben was here because I dropped to the floor. And then the phone started ringing and it was some of the other babies calling to check on me and me needing to check on them.”

Just as Freddie’s been a force in the lives of young people for a long time, so has Ben, who’s made at-risk youth his mission. As part of his long-time gang prevention and intervention work he even founded an organization, Impact One, that supports young people in continuing their education and becoming employable.

Because he’s been where they are, he feels he can reach young men and women whose lives are teetering on the edge of oblivion.

“It’s amazing how quickly you can spiral down into some really deep stuff if you let yourself, so I understand,” he says.”When people ask me why I do i deal with gang members it’s because I know ’em. I know how they think, I know what they think, I know most of ’em don’t want to do what they’re doing because I didn’t.

“But you get to a point after awhile where it becomes a lifestyle that makes it very difficult for you to get out of and the only choice you have sometimes, and the only choice I see for a lot of these young men, I hate to say this, is to leave here. I don’t like the brain drain. A lot of these people are really smart. But they’ve cast such a bad shadow that I don’t know how you stay here. I mean, I think there has to be some time between they’re leaving and coming back.”

He says something missing from today’s street dynamic is a kind of mentoring that used to unfold on the corner.

“At that time we had older guys that were able to talk to the younger guys.”

Kind of like what Ben does today.

“Someone might say, ‘Stop, don’t do that, that’s crazy.’ Or, ‘If this is what you’re going to do, here’s how you do it.’ Those kinds of things.

These young men don’t have that. A lot of them don’t. I’m talking about across the country. There’s nobody on that corner anymore who’s older who can tell them…”

“It used to be the young guys on the corner and the wise guys that went back to the corner gave people words of wisdom, and that’s gone,” says Freddie, who’s known her share of hard corners.

“That’s lost,” says Ben.

He says what’s missing from too many of today’s homes and schools in the inner city and elsewhere is the kind of discipline he got from his parents and sister and the military.

“I think most of us want it, we just don’t know we want it. Discipline is a method of working with people and molding people into what they should be as adults. That’s what it is. And that’s what my father tried to do for me in the brief time he was on this Earth.”

Gray sees a disconnect between some of today’s African-American youth and schools.

“I think what’s missing from majority minority schools is a pathway to get young people to know who they are. Our African-American students don’t know why they are. They don’t know the background. In the classroom they get a real strong dose of European history but they don’t get much about who they are.

“When there’s little or no discussion about you then how do you sit there and maintain an interest in being there?”

OPS has struggled closing the achievement gap between African-American students and nonblack students. Gray says before any real progress can be made “you’ve got to get them to stay there and keep them interested,” an allusion to the high truancy and drop-out rates among African-American students.

The problem has thus far defied attempted remedies.

He says, “In spite of efforts by the Empowerment Network, Building Bright Futures and others to address core problems like truancy and drop-outs in the (North Omaha) Village Zone we’re losing kids, they’re not staying in school. And they’re not staying in school because the influence of the street is such a strong influence. I know it. Those streets call you, man, and you can be in that classroom six hours a day but damnit you’ve got to go home and when you dog home you go to an environment that’s primarily unhealthy.

“So in spite of all we’ve done in that Village Zone we’re not winning.”

He doesn’t pretend to have the answers. He knows the problem is complex and requires multiple responses. But he does offer an illustration of one approach he thinks works.

“Teachers are constantly amazed I can address a school assembly and keep kids’ attention. Staff don’t get it. Freddie gets it. I talk about where the kids came from, I talk about who they are, I talk about what their history has been. They listen because they don’t (usually) hear that. That’s part of the missing piece of why they don’t stay. They don’t feel there’s anything there for them.”

He doesn’t claim miraculous results either.

“Any of us who are involved in this effort who talk to these kids know they’re not going to hear everything we say right away. They’re waiting to hear if we’re genuine. I tell them, ‘I’m not here to get all of you, I’m not here to convince any of you of anything. One of you is going to hear what I say, respond and react to what I say by becoming a leading citizen in this community. So I’m just here to get my one.’

“That’s when they start listening. They want to be the one.”

Flanked by Freddie Gray and Ben Gray, grieving parent Tabatha Manning at a press conference in the aftermatth of losing her 5-year-old child to gun violence.

Freddie appreciates better than most the challenge of educating children when so many factors bear on the results.

“We don’t produce widgets, we produce the citizens that are going to run this country. That’s exactly what we’re doing every single day. Every single one of these kids is an individual who deserves to have an individual touch them. It’s about that one-on-one relationship if we’re going to get kids to succeed, and if we don’t get this right then I think that says something about what the state of this country will be.

“Poverty is going to be the thing that kills us if we don’t take care of it and the only way I know to do that is to provide our children with the necessary skills to become employable.”

She’s keenly aware of criticism that the school board has ceded too much power to the superintendent.

“I understand people say that thing about the board being a rubber stamp but they don’t come and listen to the committee meetings and hear the board in dialogue. By the time theres a news sound bite we’ve already talked about it or figured it out or tabled it. Those things happen during the day (when the cameras aren’t on).

“But trust me we’ve got this. My job is to provide the superintendent with guidance in saying, ‘This is what you will do.’ There has to be parameters. We’ve got statutes to follow.”

In seeking solutions to bridge the achievement gap, she say, “I’m talking to other districts’ board presidents and members, not just when I’m on the Learning Community, but other times, too. That hasn’t happened much before.”

She says more collaboration is necessary because studies show that wherever kids live, whatever their race, if they live in poverty they underachieve.

“Poverty is a problem. If we’re not addressing poverty now than 20 years from now we’ll be having the same conversation.”

Breaking the cycle is a district goal.

“At the board level it’s looking at careers. We do kids a disservice when we say everybody’s going to college because that’s a lie and we all know it. But we do need to supply them with the necessary skill sets so they can be productive citizens.

“We’ve got to get these young people to the place where they can get jobs, where they can get out of poverty.”

She says OPS is finding success getting businesses to offer students internships that provide real life work experiences. He’s been active in the Empowerment Network’s Step-Up Omaha program to provide young people summer training and employment towards careers.

As both of them see it, everyone has a stake in this and a part to play, including schools, parents, business.

“There’s room at the table for everybody and everybody has to have a foot in this and has to step up. The focus has to be on what can we do together,” she says.

Now that she’s solidly in the public eye in such a prominent job she hopes African-American women follow her.

“I have to say this for other women who find themselves feeling like they’re voiceless: If you can see it, you can be it. There’s a lot of young African-American females who are just sharper than sharp, that could run rings around me all day doing this, but they don’t feel like they have a voice.

“And so I really hope they are paying attention because again Miss Freddie is not going to be doing this for the rest of her life and some of them are going to need to be sitting on this board.”

Ben Gray feels the same way about the young men and women of color he wants to see follow him into television or politics or wherever their passion lies.

Both with his own children and those he’s “adopted,” he’s taken great pains exposing them to African-American history and culture and encouraging them to engage in critical thinking and discussion.

“I wanted them to be more aware, I wanted all of our children to be aware of what’s around them and what it takes to survive. And to know who they are and what their history is, and some of them can tell you a lot better than I can tell you now.

“We have two that are like our own who are former gang members. Both of these guys are brilliant young men, and given a different set of circumstances would be someplace else.”

Ben and Freddie Gray are living proof what a difference new circumstances and second chances can make.

Related articles

- Masterful: Omaha Liberty Elementary School’s Luisa Palomo Displays a Talent for Teaching and Connecting (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Fast Times at Omaha’s Liberty Elementary: The Evolution of a School (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Negro Leagues Baseball Museum Exhibits on Display for the College World Series; In Bringing the Shows to Omaha the Great Plains Black History Museum Announces it’s Back (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Kelly: It’s not about the ‘sex story,’ Freddie Gray says of Sebring (omaha.com)

- Brown v. Board of Education: Educate with an Even Hand and Carry a Big Stick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha’s Malcolm X Memorial Foundation Comes into its Own, As the Nonprofit Eyes Grand Plans it Weighs How Much Support Exists to Realize Them (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Psychiatrist-Public Health Educator Mindy Thompson Fullilove Maps the Root Causes of America’s Inner City Decline and Paths to Restoration

America’s inner cities are sick. Have been for a long time. They’re long overdue for a sweeping public health approach that gets to some of the root causes of their decliine over the past 40-some years. North Omaha (really northeast Omaha) is a case in point. It’s long been in need of a transformation and one finally is underway after years of neglect, half-starts, spotty redevelopment, counterproductive urban renewal efforts, and rampant disinvestment. Psychiatrist and public health educator Mindy Thompson Fullilove has done much research, writing, and speaking about what’s happened to drag down inner cities and what’s needed to bring them back and I wrote the following piece on the eve of a presentation she gave in Omaha. I interviewed her in advance of her talk. I did attend her program, and though I didn’t do a followup story to report what she said I can tell you she covered many of the same points she made with me in our session.

Psychiatrist-Public Health Educator Mindy Thompson Fullilove Maps the Root Causes of America’s Inner City Decline and Paths to Restoration

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared iin The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The low standard of living found in segments of Omaha’s inner city mirrors adverse urban conditions across America. Poverty, low test scores, unemployment, gang violence, teen pregnancy, HIV/AIDS and STDs, distressed/devalued properties all occur at disproportionately high rates in these sectors.

Psychiatrist Dr. Mindy Thompson Fullilove, a public health educator at Columbia ((N.Y.) University, studies the causes and consequences of marginalized communities. A pair of talks she’s giving in Omaha next week, one for the public and one for health professionals, will echo local efforts addressing economic-educational-health disparities, infectious diseases and inner city redevelopment.

By training and disposition Fullilove looks for the connections in things. Much of her research focuses on linkages between the collapse of America’s urban core and the corollary decline in health — physical, psychological, emotional, environmental, economic — endemic there. She blames much of the blight on fallout from late ‘40s through mid-‘70s urban renewal projects.

Many longtime Omaha residents rue the North Freeway for driving a stake through the heart of a once cohesive, stable community. Hundreds of homes and dozens of businesses were razed to build it. Critics say this physical-symbolic barrier divided and damaged an area already reeling from late ‘60s riots that destroyed the North 24th St. business district, which only hastened white flight.

These interrelated phenomena, Thompson Fullilove believes, caused widespread carnage in cities like Omaha — displacing families, disrupting lives, rupturing communities, dragging down quality of life, property values, self-esteem and hope. In her view urban renewal was part of policies that “destroyed neighborhoods” — as many as 2,500 nationwide by her calculation — in the guise of progress.

“Many of the ways in which we built at that time involved demolishment of a neighborhood,” she said by phone. “There were these very large projects put in so that the old grid of the city was fused into sort of super blocks and huge things built on them like cultural centers or universities that made a fundamental change in the flow of the city. A lot of these projects were really not very thoughtful and didn’t work. So we’re living with the aftermath of very bad urban development, much of which is now coming down and being replaced.”The kind of severing of neighborhoods that occurred when freeway projects cut through the heart inner cities

Witness the sprawling Logan Fontenelle public housing project that came down a few years ago in northeast Omaha. In the early ‘70s, large tracts of land dotted with homes and businesses in far east Omaha were cleared for airport expansion. Anytime people are forced to move from their home it’s a major stress that can dislocate them from family, friends, jobs, neighborhood, community.

“Displacement is always accompanied by violence,” said Thompson Fullilove. “When people are displaced they need help to get back on their feet but if there’s never any help then things can get worse and worse. You get anger, hostility, and then people, instead of being able to solve problems, are just trying to survive.”

She said when people live outside social networks-support systems, epidemics like AIDS, STDs or gun violence emerge and grow entrenched. Often she said, people displaced from their homes also get displaced from blue-collar jobs. “People have no way to make a living and no social network to fall back on, so it’s really a double whammy,” she said. The results? “Terrible crime as people try to do work in the underground economy.” Thus, the drug trade thrives, gangs go unchecked. Some observers say Omaha’s African American community is still hurting from the packinghouse/manufacturing/railroad jobs lost in the ‘60s-‘70s.

She said today’s info service-high tech economy leaves many workers behind. “You have to get people to learn skills, you have to get people more education and you have to be inventing what they’re going to work at, and all these require a stable, engaged city as a center of exchange not a city of haves against have-nots,” she said. “Until cities are places of development, we’re in bad trouble as a nation.”

A term she uses to describe displacement’s trauma, “root shock,” is also the title of a book she authored examining how the ripple effects of urban renewal impact whole swaths of cities and persist long after the bulldozers leave.

“It has a ripple both in time and in space,” she said. “So tearing up a neighborhood has ripples for a whole metropolitan area and it also has ripples over time for generations of people who live in that area. Also, when you demolish a big area it creates a ripple of destruction on the other side of the area you demolish — you also decrease the value and the stability of the properties. And as those properties decline in value and really fall apart the properties next to them fall apart, and then the properties next to them fall apart. So you can actually take a drive in a place where there was urban renewal and find the leading edge of the destruction, typically a couple of neighborhoods over from where the urban renewal was done and, sometimes, even further.”

She said the decline extended to downtowns.

“Many neighborhoods demolished for urban renewal were near downtown or part of the downtown,” she said, “so demolishing a lively neighborhood which added to the strength of a downtown shopping center contributed to the collapse of many American downtowns, which are only slowly coming back.”

Like a disease introduced into a larger host, she said as urban decline spread it compromised the health of entire cities.

“It installed something that was dysfunctional in a critical part of the landscape of the city,” she said, “Although we think of all the terrible things that happened to the African Americans who actually lived in many affected neighborhoods, the worst consequence is that we made our cities weaker, so the whole nation lives with that grievous error. Cities are important for our nation because they really are the economic engine. So undermining the cities the way we did weakened our whole economic prosperity. You might say one of the seeds of this current economic crisis is in the destruction of our cities.”

From her perspective, America hasn’t corrected these problems — “what we’re doing instead is continuing to use versions of the same process.” She said even where a city center may enjoy a renaissance “it’s being rebuilt with the goal of attracting people from the suburbs to come back to the city.” That’s gentrification. “So the goal is not to make the city a welcoming place for all people that might like to live there. As opposed to figuring out how do you make a city which is a place of exchange, you’re making a city a place of exclusion,” she said, “and that’s just as destructive as urban renewal.”

She notes there‘s not yet widespread understanding among policymakers, developers and stakeholders of processes that diminish-threaten public health. She’s hopeful conferences like one she was at earlier this month in NYC, Housing, Health and Serial Displacement, “really open up this conversation, because I think if we’re going to have exciting cities in the United States it requires really a new approach to how you build cities, not just pushing people out.” She and her husband, community organizer and sociomedical sciences expert Robert Fullilove, work with urbanists on strategies for sustainable, inclusive, built environments.

Through the couple’s think tank, Community Research Group, they study and advocate holistic, public health approaches to urban living dynamics that view cities as ecosystems with interdependent neighborhoods-communities. What happens in one district, affects the rest. If one area suffers, the whole’s infected.

“You can’t undermine stable living conditions in a neighborhood or a community without bringing down the quality of life of everybody in the area, and it’s a very large area that then gets affected,” Thompson Fullilove said. “The foundation of health is good living conditions. Health is sort of our ability to enjoy our lives.”

Related articles

- A Synergy in North Omaha Harkens a New Arts-Culture District for the City (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Brief History of Omaha’s Civil Rights Struggle Distilled in Black and White By Photographer Rudy Smith (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha’s Northwest Radial Highway’s Small Box Businesses Fight the Good Fight By Being Themselves (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Demolition is Not Enough: Design After Decline Author Brent Ryan on Redevelopment in Philadelphia (pennpress.typepad.com)

- Bill Cosby Speaks His Mind on Education (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Lifetime Friends, Native Sons, Entrepreneurs Michael Green and Dick Davis Lead Efforts to Revive North Omaha and to Empower its Black Citizenry

Two well-connected players on the Omaha entrepreneurial scene and two stalwart figures in efforts to revitalize predominantly African-American North Omaha are Michael Green and Dick Davis. The Omaha natives go way back together and they share a deep understanding of what it will take to turn around a community that lags far behind the rest of the city in terms of income, commerce, jobs, education, housing starts, et cetera.

Lifetime Friends, Native Sons, Entrepreneurs Michael Green and Dick Davis Lead Efforts to Revive North Omaha and to Empower its Black Citizenry

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the New Horizons

Growing up in the late 1940s-early 1950s, Michael Green and Dick Davis knew The Smell of Money from the pungent odors of the bustling packing plants and stockyards near the Southside Terrace apartments they lived in. Buddies from age 4, these now middle aged men began life in similar disadvantaged straits, yet each has gone on to make his fortune.

Instead of the old blue collar model they were exposed to as kids, they’ve achieved the Sweet Smell of Success associated with the fresh, squeaky clean halls of corporate office suites. Education got them there. Each man holds at least one post-graduate degree.