Archive

A Story of Inspiration and Transformation: Though Living on the Margins, Aisha Okudi Gives Back, and She Nurtures Big Dreams for Her Esha Jewelfire Mission Serving Africa

Life is what you make of it, the saying goes. Attitude is everything, goes another. Aisha Okudi is living proof that when these aphroisms are put into action life can take on a whole new meaning and direction. By being intentional about how she apprehends the world, Okudi is no longer living the self-centered life that led to ruinous consequences. Her life today is focused on positive self-empowerment through service to others. That doesn’t mean hard things don’t still happen to her. But she’s much better equipped to handle what the world deals her in healthy ways rather than the destructive ways she used before. Her inspirational story of transformation and recovery is beginning to get her noticed. That has a lot to do with her charming personality, high-energy, and humanitarian vision. She has very little in the way of monetary means or material goods, yet she’s embarked on an international mission that she seems destined to fulfill. She’s not likely to let anything stand in her way either. You go, girl!

A Story of Inspiration and Transformation: Though Living on the Margins, Aisha Okudi Gives Back, and She Nurtures Big Dreams for Her Esha Jewelfire Mission Serving Africa

©by Leo Adam Biga

When buoyant, self-made social entrepreneur, visionary and humanitarianAisha Chemmine Mure Okudi reviews how far she’s come in only a few years she can hardly believe it herself. It’s not so much that her three-year old Shea Luminous by Esha Jewelfire line of organic shea butter bodycare products is such a thriving success. It’s more to do with her business being an expression of her ongoing recovery from unfortunate life choices and setbacks as well as a conduit for her African missionary work.

At the base of her products is butter extracted from the shea nut, a natural plant indigenous to the very rural West African provinces she serves.

After years helping poor African children from long-distance by sending supplies and donations, she visited Niger, West Africa for the first time last spring through the auspices of the international NGO, Children in Christ. She engaged children in arts and crafts and games and she enlisted the support of tribal leaders, church-based volunteers, Nigerian government representatives and American embassy officials. She purchased a missionary house to accommodate more evangelists.

She says she’s tried getting local churches on board with her missionary work but has been rebuked. She suspects being a woman of little means and not having a church or a title explains it. Undaunted, she works closely with CIC Niger national director, Festus Haba, who calls her work “a blessing.”

She intends returning to Africa in May. Her long-range plan is to move to Niger. She envisions growing her business enough to employ Africans and to open holistic herbal health clinics. She’s studying to be a holistic health practitioner.

Contrast this with the desperate young woman she was in 2004. The dissolute life she led then found her crying in an Iowa jail cell after her second Operating While Intoxicated offense. Her arrest came after she left the strip club where she performed, bombed out of her head.

“I had to get drunk so I could let these men touch me all night,” says Okudi, who ended up driving her car atop a railroad embankment, straddling the tracks and poised to head for a drop-off that led straight into a river.

The Des Moines native had been heading for a fall a long time. Growing up, her family often moved. Finances were always tight. She was a head-strong girl who didn’t listen to her restless mother and alcoholic father.

“There were issues at home. I was always told no coming up and I got sick of hearing that. I felt I was a burden, so I was like, ‘I’m going to get out and get my own stuff.'”

At 15 she left home and began stripping. A year later she got pregnant. She gave birth to the first of her four children at 17.

“I found myself moving around a lot. I really didn’t know what stability was. I never had stability, whether having a stable home or just being stable, period, in life. I was young and doing my thing. My dad walked in the club where I was stripping. My sister told on me.”

The confrontation that ensued only drew her and her parents farther apart.

“I was trying to live that life. I wanted to have whatever I wanted to have. My mom and dad struggled and we didn’t get everything I thought we needed, so I did my own thing. I danced, I sold my body and I made lots of money from it. I did it for about 12 years. I wanted to have it all, but it was not the right way.”

She got caught up in the alcohol and drug abuse that accompany this sordid life. Stealing, too.

“I was in and out of prison a lot. I used to steal to make money. I was in and out of trouble and the streets.”

She served a one year sentence for theft by receiving stolen property.

That night in jail seven years ago is when it all came to a head. “I just sat there and I thought about my kids and what I just did,” she says.

She felt sure she’d messed up one too many times and was going to lose her children and any chance of salvaging her life, “I was crying out and begging to God. I had begged before but this time it was a beg of mercy. I was at my bottom. I surrendered fully.”

To her great surprise and relief the judge didn’t give her jail time. “I told the judge, ‘I will never do this.’ He said, ‘If I ever see you in my courtroom again it will be the last time.’ I burnt my strip clothes when I got out, and I didn’t turn back. I got myself into treatment.” She’d been in treatment before but “this time,” she says, “it was serious. It wasn’t a game because it used to be a game to me. I enrolled in school.”

Seven years later she has her own business and a higher calling and, she says, “I ain’t doin’ no jail time, I’ve paid all my fines, I never looked back, I kept going. I’m so proud that I write the judge and tell him how I’m doing.” She’s learned how to live a healthy lifestyle and not surround herself with negative influences and enablers.

Her life has turned many more times yet since getting straight and sober.

In 2006 she seemingly found her soulmate in George Okudi, an ordained Ugandan minister and award winning gospel artist. They began a new life in Washington DC and had two children together. Then she discovered he was still married to another woman in Africa. The couple is separated, awaiting a divorce.

“He didn’t treat me right — the way he should have,” she says. “Facing that really hurts. God, I wasted these years with this man. But my kids are a blessing. I love them. They’ve really kept me focused. I try not to be bitter, I’ve forgiven him. I’m friends with him. We do have kids”

If there’s one thing she’s learned in her own recovery journey, she says, “You’ve really got to forgive, forget and let God, and He will move you in ways you can’t even believe.”

But she’s only human, therefore doubt and self-pity still creep in when she considers her sundry “trials and tribulations.” Even though she’s forgiven her husband, the betrayal still stings. “I’m going through that, too,” she says.

“Even though I’ve grown,” she says, “sometimes it feels like, When is it going to end?’ But to much is given, much is required. You’ve just gotta consistently stay on track. No matter what it is, stay focused.”

The last three years have been equal measures triumphs and tests. The difference this time around is that when good times happen or adversity strikes she doesn’t get too high or too low, she doesn’t feel entitled to act out.

She claims she experienced an epiphany in which God spoke to her and set her on her Esha Jewelfire mission.

“When I had that vision and dream I was pregnant with my youngest son. I was living with my grandmother (in Des Moines). I was newly separated from my husband. I said to my grandmother, ‘I don’t know if I’m going crazy or what, but the Lord said I will build like King Solomon and go and help my people in Africa.'”

Since childhood Okudi’s cultivated a fascination with all things African, including a desire to help alleviate poverty and hunger there. Her visit to Niger last spring and the overwhelming reception she received confirmed she’s meant to serve there.

“It was immediate. I was able to blend in wherever I went. I’m a true African and I know that’s where my calling is. It’s natural. I cook African, my children are African, my friends are African. It’s just a natural thing for me.”

She even speaks some of the native dialects.

She’s long made a habit of sending clothes and other needed items to Africa. But a call to build was something else again.

“Where am I going to get the money from to help these people in Africa?” she asked her grandma. “I didn’t know.”

Then by accident or fate or divine providence a friend introduced her to shea butter, an oil extracted from the shea nut that grows in West Africa and is used in countless bath and beauty products. “And that’s how the idea for my business came up,” Okudi says.

In its gritty, foul-smelling natural state, sheer butter held no interest for her. But, she says, “I researched it and found that it moisturizes, it cleanses, it refreshens, it brightens, it just makes you shine. So figured out what I needed to do with it.”

She experimented with the substance and developed organically sweet shea butter products and began marketing them under the name, Esha Jewelfire, which means to empower, serve and honor the almighty.

She gets the raw shea in big blocks she breaks down by chopping and melting. She incorporates into her handmade products natural oats and grains as well as fruit and herb oils to lend pleasing textures and scents. She presses the fresh fruit and herbs herself. Nothing’s processed. “All this stuff comes from God’s green earth — oils and spices and herbs, organic cane sugar,” she says. Nothing’s written down either. “I have it all in my head. I know every ingredient in everything I make. Everything is made fresh to order and customized. I hand-package everything, too.”

Selling at networking events, trade shows, house parties, off the Internet, the small business “started really growing and taking off for me,” she says. “It was prophesied to me I will have a warehouse and be a millionaire one day and I believe that. Getting prepared is all I’ve been doing.”

Her business has been based at various sites, including the Omaha Small Business Network. Production unfolds in her mother’s kitchen, in a friend’s attic or wherever she can find usable space. She’s placed her products in several small stores but having a store of her own is attractive, too. Earlier this year “an angel” came into her life in the form of Robert Wolsmann, who within short order of meeting Okudi wrote her a check for $10,000 — as a loan — to help her open her own shop.

Wolsmann of Omaha is not in the habit of lending such amounts to near total strangers but something in Okudi struck him. Besides, he says, “I could see she needed help. She showed me what she made and I was so impressed that I presented her with that money. I couldn’t resist investing.”

“He’s an awesome person,” Aisha says of Wolsmann. “We’ve become great friends.”

She says her dynamic personality has always attracted people to her. She feels what Wolsmann did is evidence that “things work in mysterious ways — you don’t know what’s going to happen, you’ve just got to be prepared.”

Her Organically Sweet Shea Butter Body Butter Store at 3019 Pinkney St. opened last spring after she returned from Africa. It was a labor of love but it proved a star-crossed venture when after two months her landlord evicted her.

Her reaction was to ask, “What is going on God and why does this keep happening to me? I didn’t have nowhere to go. I was seeing myself back living from place to place like I’ve always been, still trying to take care of my kids and do my business.”

Stripping’s fast money tempted her before she rejected the idea. Then she found a haven at Restored Hope, a downtown transitional housing program for women and kids.

“Restored Hope has been stability for me. It’s a year program. It keeps me focused on my mission. I’ve been called to be that missionary, so I’m not so upset anymore about why I’ve been bounced around or why things have happened the way they have. There’s a way bigger purpose. If you just be really humble and wait and be patient to see what God’s doing, He’ll turn things around.”

It’s why she doesn’t dwell on the past or worry about what she doesn’t have right now.

“Nothing matters when it comes to material things. The only thing that matters to me is my health and just doing what I know is right in my heart to do. Even though I live the way I live, basically homeless, I realize I am very blessed. And I’m grateful.”

She’s aware her ability to stay positive and keep moving forward amid myriad struggles inspires others. She says some of her fellow Restored Hope residents tell her as much,

“It reminds me who I am and that when I don’t think people are watching me they are. I’ve always been a happy person. Even when I’m going through something, I pick myself up. I’ve always been a giving, loving person. Even my father said, ‘Because of you my life’s changed. I’ve seen where God has taken you through and you still hang on. If you can be changed from where you came from, I know there’s a God.’ Now he’s stopped drinking. He’s reborn.”

Her own rebirth would be hard for some to believe. “People who knew me in my past might say, ‘Oh no, not Aisha, with what she used to do?'” She doesn’t let skepticism or criticism get her down.

“I just get up knowing I gotta do what I gotta do, and I live one day at a time. I don’t let my financial and emotional path haunt me. I’m not in control, God’s in control. There’s nothing you can do but do what you need to do every day and be a part of hope.

“Too many people are hopeless. You can see it in their facial expressions and the way they do things. There’s no light in them. I’m not about that, I’m about life and living to the fullest and being happy with what I have and where I’m at because I know greatness will come some day for me. I’m a very favored woman in all things I do.”

She suspects she’s always had it in her to be the “apostolic entrepreneur” she brands herself today. “Sometimes you don’t discover it until things happen to you. I think I had it but I didn’t embrace it then. I heard so much negative in my life coming up that it turned me away…I said, ‘I’ll show you,’ and I made wrong decisions. What the devil meant for bad, God turned it for good.

“I’m a natural born hustler but I hustle in the right way now.”

View Aisha’s entire product line and read about how you can help her African mission at eshajewelfirellc.homestead.com.

Related articles

- I Am Because We Are: African Wisdom in Image and Proverb (gumption.typepad.com)

- Why Women Are the Future of Africa (hueintheworld.wordpress.com)

OPEN WIDE, Dr. Mark Manhart’s Journey in Dentistry, Theatre, Education, Family, and Life /A Biography

-

- The rest of the fall expect occasional excerpts like this one from my first book, Open Wide, a biography of an interesting fellow named Mark Manhart. He asked me to tell his life story in book form and once I satisfied myself he had a story worth sharing and the ability to compensate me we struck a deal and over the course of a couple years I feel I got to know him well enough to at least put down a reasonably informed appreciation and examination of his life for posterity’s sake. You can order the book at the following links:

- http://www.conciergemarketing.com/open-wide

- http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/open-wide-leo-adam-biga

- http://www.calciumtherapy.com/latest-news/open-wide

OPEN WIDE

Dr. Mark Manhart’s Journey in Dentistry, Theatre, Education, Family, and Life /A Biography

©by Leo Adam Biga

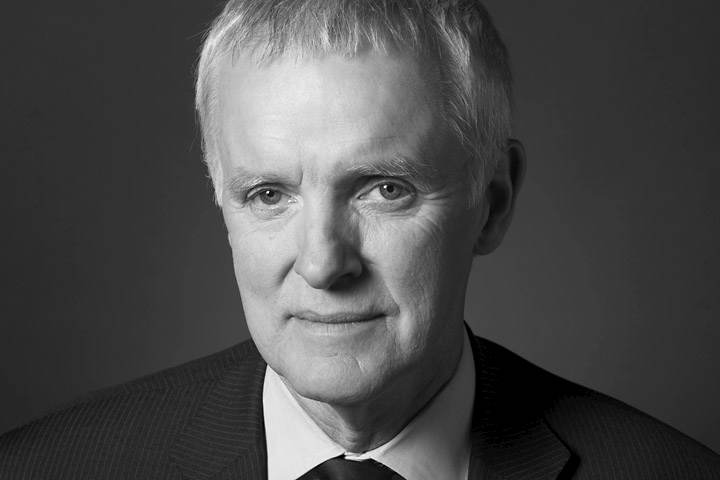

Mark Manhart

A Life in the Open

We all lead a few lives or, if you prefer, double lives. Mark Manhart knows something about the mirrors of life. In his professional life, he is a dentist. In his personal life, he is a writer, director, history buff, landscaper, father, grandfather, and husband among a few different pursuits. “I think everybody has that kind of dual life going, especially people who get into such specialized things as dentistry. A professional has to lead two lives. Your open life and your other lives,” he said. The Omaha, Nebraska resident has an opinion on most everything, and he usually has a philosophy to support his viewpoint. Try this one on for size: “One needs a real work-a-day life and then at least one other life, some hobby, avocation, distraction, to work on to nearly inane proportions, so one can return to home base refreshed, go to bat again, and make your way before the inning and game is played out. I have gone through many family and professional things that were very much like sitting in the dental chair. All have been adventuresome.”

For this man of many interests and talents, life is also full of what he likes to call “natural wonders”—those unforgettable people and events that he enjoys experiencing and cultivating. He is all about opening new horizons of discovery in his personal and professional lives.

One domain feeds the other; one dimension offers solace from the other. “All of this, in any position or occupation, is terribly important to one’s sanity, pleasure, growth, and accomplishment,” is how he sees it.

For fifty years Manhart has indeed left the confines of home for the office, leaving behind his domestic incarnation for that of the highly trained, working professional who not only practices dentistry but is actively engaged in developing new treatments or therapies.

Then there is the life that revolves around some inner passion that enables him to return to work recharged, ready to resume life in the open and persevere. For Manhart, it is the world of arts and letters that feeds or fulfills him with the sustenance to carry on with renewed vigor. Specifically, it is the life of the theatre and his work as a playwright and director, and occasionally as an actor, that is a source of satisfaction, of solace, of energy, of intellectual and emotional discovery that offers a balance or complement to his professional and family endeavors.

There is also the life he maintains with his spouse. Here, too, Manhart is well-versed in that song and dance called marriage. He has been married twice. His first marriage lasted more than two decades and resulted in eight children. That union ended in divorce, but when he was ready to start a new chapter in his life, he did not hesitate to marry again, to a woman with a pair of children of her own. This second marriage-go-round has now exceeded more than two decades itself, which would seem to indicate he is the marrying kind.

He and his wife, a spitfire named Bonnie Gill, make it work despite being very different personalities. They may not see eye to eye on many things, and they may handle situations quite differently, but when it comes to what is important in life, they are simpatico. They are both searchers, ever inquisitive to turn the next page in life, to see what is over the next hilltop, to experience a new culture or way of doing things. Both are principled people. Both would rather give than take. Both are creative souls.

It seems Mark Manhart’s thirty-year dental partnership with Dr. Tom Steg can be thought of as a kind of marriage in itself. The two men are opposites in most ways but are kindred spirits where it counts most, as people of high character, intense curiosity, extreme professionalism, and with a penchant for pushing beyond the norm of dentistry to find the best ways of caring for patients.

With his tall frame, angular features, shock of silver hair, confident pose, resonant voice, formal manner, and reserved personality, Manhart cuts a striking, classic figure. He comes across at once as a bold, magnetic personality with an authoritative air and yet at the same time as a quiet, pensive, somewhat shy, even insecure soul. It is that duality that is so much a part of him. It is an expression of his charm and his complexity.

Call it fate or coincidence, but this practitioner of the healing art of dentistry also became a creative artist somewhere along the line. More likely, he was an artist right from the start and his muse simply waited for when the time was right to finally bloom. Many of the qualities that make up a healer, after all, are much the same as those that characterize an artist: empathy, discernment, problem- solving, discipline, craft, even imagination.

Manhart still lives that personal brand, striking a balance between right- and left-brain activities that put him squarely in the mix of Omaha culture, community, and commerce. Long before social networking became a catch-word and lifestyle for the online era, he was engaging people from all walks of life and exploring ideas from disparate sources.

Calcium Therapy Institute

He was ahead of the curve on the Internet as well, launching a website for his practice back in 1995. He is on LinkedIn, Facebook, and all the other go-to social media sites. He blogs. He even conducts online training sessions for dentists from around the globe. He is as connected as anyone of his generation.

His inclusive, progressive approach to dentistry may best illustrate how open-minded and receptive he can be to new ideas and new collaborators. Eager to always improve his craft, he makes a habit of seeking out the latest advances by poring over dental journals from around the globe. Staying current this way has spurred him to make his own breakthroughs and to share his advancements with peers in the United States and abroad.

Away from dentistry, his work as a playwright and theatre director reflects his eclectic tastes, ranging from sentimental love stories to historical dramas to bawdy comedies to high- brow treatises to full-blooded biographies to English manor mysteries. From kitsch to classic, Manhart embodies it all.

Not so very different from the way he seeks to break new ground in dentistry, he actively seeks out new forums and challenges in theatre. He has done the same in education, too, as a champion for the Montessori method of early childhood instruction and for home-schooling. Although he has been a clinician most of his working life, he has also taught dentistry formally at the university level and informally in workshops and trainings.

Whether navigating the worlds of medicine, business, education, or art, he is an enterprising, energetic innovator open to new, even unconventional ways of doing things. He is what some people call today “a creative.” It is really another word for “eccentric” or for how one of his own children described him—“a half bubble away from genius.” That missing other half of the effervescent bubble can sometimes make him look like a fool or an idiot some people very close to him will tell you. It is a risk he is willing to take.

Great Plains Theatre Conference

His work and life are expressions of an inquisitive mind and a sensitive disposition. His office displays pictures of the charming digs he kept in The Passageway of Omaha’s historic Old Market district, the cultural heart and soul of the city he felt right at home in. Once the wholesale produce center for the city, the district was redeveloped beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s into a European-style marketplace.

The Mercer family of Omaha led efforts to preserve and reuse the century-old warehouses as restaurants, galleries, theaters, shops, and residences. Manhart fit right in with the Old Market’s creative class denizens.

The Old Market has become one of the state’s largest tourist attractions, along with the world-class Henry Doorly Zoo as a magnet bringing visitors to the city. Due to health issues of his own, Manhart long ago had to set aside this second office in The Passageway at 10th and Howard Streets. The Market and his affection for that Old World location is evident in the photographs he displays of the brick-hewn office and environs he practiced in there. He also keeps an antique dentist’s chair in his West Omaha office as a token of his appreciation for “good old-fashioned” dentistry, craftsmanship, and values.

Manhart’s full life is not just a professional or aesthetic exercise. His life extends to family. He came from a huge clan, and he is the father of eight himself.

“I always wanted a large family of twelve children. A lot of kids who could become ‘adult’ adults. As a granddad, it is hard to see much success in that regard, so I must wait it out. I think I was a good father but that is slightly biased. People would say I am too harsh, too outspoken, too busy elsewhere, distracted too easily, too liberal, too persistent, frugal to cheap, an exaggerator, cold with little emotion, a trouble starter, and more. An old friend, a Jewish lady, hit it for me: ‘You are a starter. We have enough finishers.’ My obligation to the kids was to house, feed, protect them from others and each other in a way that they would be able to do the same as adults, and love them. Most of the love was, and will remain, secret between each one and me. Some day I want to write about that,” he said.

Cast members of plays from Great Plains Theatre Conference

Those who know Manhart from his life in the arts may not even know he is a family man, much less a dentist. Just as those who identify him as a dentist may not be aware of his other lives. That is all par for the course for someone who throws himself passionately into whatever endeavor he is engaged in at the moment. It is not as though he focuses on a passion to the outright exclusion of everything else, but he does tend to lose himself in whatever it is he is engaged in at the moment.

His single-minded devotion is evident in his dental career. He has been in private practice now forty-five years. Counting his time doing dentistry in the United States Air Force Dental Corps and his time in dental college, he has been actively engaged in the field of dentistry for more than half a century. However, the way he has chosen to practice, by utilizing noninvasive calcium treatments of his own design, has made him an outcast of sorts within his field. And being shunned by the dentistry establishment was just the beginning; legal action to stop him followed, but each case served to strengthen his resolve.

To further his somewhat nontraditional approach to dentistry, he founded and directs the Calcium Therapy Institute in his hometown of Omaha. The Institute is the vehicle for Manhart to do dentistry and science side-by-side, using his preternatural inquisitiveness and idiosyncrasy to investigate dental problems and treatment options along lines that do not necessarily conform or adhere to organized dentistry’s prescribed ways. That is just the way he likes it, too. Tweaking the nose of authority is a Manhart trait.

He enjoys playing the contrarian. Much the same way his late father, a farmer-turned-attorney-turned-inventor, was his own man who went his own way, damn the consequences, Manhart is a maverick accountable only to himself. He takes the road less traveled, whether in his personal or professional affairs, following an inner muse that neither brooks compromise nor suffers fools gladly nor worries about what people say.

There have been times when he has severed major threads in his life in order to do what he felt was right, regardless of how others perceived him and his decisions. For example, he and his first sweetheart, Mary, married and raised a large family together. She is the mother of his eight kids. After the kids were grown, the couple decided to end the marriage.

“Mary and I were happily married for a long time,” he said. Then they simply reached a place in time when they determined they would be better off apart.

Following years as an active member of the American Dental Association and officer in the ADA’s Omaha branch, he set aside organized dentistry as well. He has practiced without direct affiliation with the dental establishment— that is, his ADA membership and a position teaching at his dental school. However, the tradeoffs became more focused on his patient care, clinical research, and life beyond dentistry. At the time he won a lawsuit over patient treatment that was egged on by dentists who opposed his research in the advanced uses of calcium materials. When a number of specialists testified against him, there were subsequent, immeasurable losses to his reputation and health.

Aside from getting some of his findings published in the preeminent international dental journal more than twenty- five years ago, and in a few minor journals, his attempts to publish his work in America have been repeatedly rebuffed, much to his frustration. Nonetheless, in 2009 a prestigious European dental journal published his latest findings almost immediately and without reservation. His perceived banishment in the United States is a source of bitterness with him but just how much it bothers him is hard to gauge as he tends to dismiss it or brush it aside as no big deal. His wife, Bonnie, knows differently.

Bonnie Gill

How much has he been hurt by all this? “Very hurt. More than you can imagine,” she said. “I cannot even talk to him about it, and some of it I think he has brought on himself. But I think as he gets older it is killing him and I keep telling him, ‘You gotta let it go.’”

Bonnie said her husband can be hard to read, even for her, because he is such a mix of things and because he can hide behind an inscrutable, sphinx-like mask that serves to insulate and isolate him from those around him.

“I know him probably better than anybody else, I would say better than any human being on Earth,” she said. “He is a very complicated soul and a very kind person. It is sometimes the bane of his existence and actually what probably drew me to him. I knew before I ever got hooked up with him that he was incredibly honest. What I do not admire is that he can seem to turn that on and off and be extremely cruel when he wants to be, too. This is one of his flaws—it’s my way or no way—he cannot ever see the gray areas on some of this stuff, which he is very good at seeing on other things.”

She has no trouble standing up to him when she feels he is wrong and telling him so. He can handle being called out on his mistakes and has no problem with Bonnie’s candidness and her telling him like it is.

Bonnie said, “You know, it takes a pretty strong guy to accept being told, ‘I think you’re full of it.’ But that is the kind of relationship we have. It’s perfect because I do not ever have to get up wondering who I should be today.” In other words, she can be herself. With Mark,” she said, “I always know I can be who I am, warts and all, and it might be a little grumpy, but it’s going to get worked out.”

She has been there through the highs and lows of his dental life. She has seen the toll it has taken on him to seek the kind of vindication and recognition he wants but that has not been forthcoming and that likely will not come anytime soon, much less in his lifetime. “One time I asked Mark in the throes of this, ‘Do you want to be rich or do you want to be famous?’ And I did not even have to ask him because I knew what the answer was. He threw me a curve ball though by saying, ‘Both.’ I said, ‘You cannot have both, you can only have one.’ And then he said, ‘Famous,’ and I said, ‘I knew that.’”

Despite setbacks he has doggedly carried on, determined to prove people wrong. Call him intransigent or stubborn or willful or simply determined, he is like the proverbial dog that won’t give up a favorite bone without a scrap. As stressful and contentious as his dentistry battles have been, the bulk of his work in the field has been fulfilling. It is why he still does what he does at an age when the vast majority of his peers are long retired.

“Look at when dentists retire. I mean, dentists retire pretty darn early, and I passed that opportunity up fifteen years ago. I keep on because our calcium therapy works and it is such a delight to practice dentistry,” he said. “You know every day I see people who have troubles and we solve them. What more of an ego trip could you want?”

A pursuit quite apart from dentistry that Manhart is no less passionate or obstinate about is the theatre. This dramatic arts enthusiast has taken the hobby seriously enough to have helped form and operate three community theatre venues: the Rudyard Norton, the Kingsmark II, and the Grande Olde Players (GOP). He co-founded and directed the latter with Bonnie. Their Grande Olde Players established a niche by producing works featuring seniors and intergenerational casts. After a twenty-four year run the Grande Olde Players Theatre, which also featured jazz concerts, staged its final season in 2008.

Manhart has also participated in the Great Plains Theatre Conference hosted by Metropolitan Community College. The college’s historic Fort Omaha campus is the site of play labs where Manhart’s work has been read and where he and Bonnie have directed play lab readings of works by other playwrights. The conference receives submissions from playwrights across America, even from abroad. It is an intensive week-long concentration on craft. Some of theatre’s greatest talents participate as readers, respondents, mentors, and panelists, all in service of furthering the work of new and emerging playwrights.

Manhart does not kid himself. He knows he is not in the same league as many of the participants, who have included Pulitzer, Tony, and Obie award winners. The experience of having his work critically evaluated has not discouraged him but has emboldened him to keep writing and improving.

He has already accomplished much in local theatre. Without a lick of formal training he taught himself how to write, produce, cast, and direct productions and to manage theatre companies. He still writes plays and he still takes directing assignments today. Bonnie also continues to write and direct. Much like his experience in dentistry, he has often butted heads with theatre colleagues and collaborators, but, right or wrong, he has always remained true to himself, which is that of a stubborn, “tough old German,” as he likes to say with a wry smile. He is actually Swiss and German, with a little French thrown in, although the borders of those countries changed so often in the not-so-distant past that his precise lineage on his father’s side, the German side, cannot be determined with absolute certainty. On his mother’s side, the Swiss side, however, the family line can be traced back some eight hundred forty years.

The worlds of dentistry and theatre could not be more unalike on the surface. But look closer and what at first seems incongruent reveals similarities, which is why Manhart has drawn from each to enrich the other. Of course, when you think about it, dentistry entails a performance aspect. After all, the practitioner fulfills the role of expert healer for the patient, who comes in search of relief. The drama and expectation alone make it a kind of theatre. Conflict is at the heart of any drama and the inherent conflict in the doctor- patient relationship is that the healer may have to cause the patient discomfort, even pain, before healing occurs.

For many patients the mere thought of going to the dentist produces extreme anxiety. Sitting in the examination chair, surrounded by all that cold, hard, sterile equipment, which for all the world resembles instruments of torture, is enough to raise anyone’s blood pressure. Then there is the whir of the drill. Add to that the unpleasant past experiences many have had in a dental office, from scrapings to extractions to injections, and you have the makings for a tense situation.

Then there is the often exorbitant cost of dentistry that not all patients have the insurance to cover. The financial burden of care is a source of some resentment. It is routine nowadays for a few extractions or a root canal, for example, to cost many hundreds of dollars. When you talk about bridges, crowns, and implants, the bill ratchets up into the thousands. Finally, some doctors do not exactly have a winning chairside manner with their condescending, paternalistic I-speak-you- listen, I am-the-expert-you-are-the-patient attitude.

Manhart went to India to lecture on calcium therapies

In stark contrast to that dysfunctional model, Manhart goes out of his way to provide high-quality service at a reasonable rate and to deal with patients in a respectful manner that makes them a part of the care plan. He has also refined his craft to the point that his supple hands have a sure touch. He said there are qualities, some tangible, some intangible, that separate a master practitioner from a run-of- the-mill one.

“It is their touch, their approach, their finesse, whatever you want to call it,” he said. As a young dentist he had a chance to not only see but to feel some masters at work. “I thought, there is the kind of practitioner I would like to be.” By all accounts, he has become one. He said, “My rule always has been, man, if I can get my hands on you, you will never go anywhere else.”

Such finesse only comes through an assurance and confidence that cannot be approximated or faked. You either have it or you don’t. “That’s everything, yeah,” said Manhart. “You cannot really hide it. It’s there and it’s in everything you do. I worked for an orthodontist named Dr. Elmer Bay, and as a teacher this guy was absolutely wonderful because you never knew you were being taught. I used to make his appliances for orthodontics, and I saw his superlative results in everything. He was very old-fashioned. A few years ago Dr. Steg [Manhart’s dental partner] said to me, ‘I had a patient who was told by so- and-so she should not go to us because we are old-fashioned dentists.’ Well, that is the best compliment anybody has ever given us because those old-fashioned dentists like a whole lot we grew up with were just wonderful.”

One old-time dentist Manhart worked with, Dr. Leo Ripp, was so well-loved and appreciated that at his funeral mourners eulogized what a great dentist he was. Manhart never heard of such a thing. “Old Dr. Ripp, he could make the most beautiful gold crown you could ever believe seeing with the oldest crap you could ever think of using,” he said. “He really just was superb. He would put a crown in someone’s mouth, and if it did not stay forty years, something was wrong here.”

Manhart has the utmost respect for the men who taught him because they were working dentists. They were the first practitioners and second teachers he has tried emulating.

“Most of my training was given to me by dentists who were practicing fulltime and coming in a little bit each week and teaching. That kind of dentist is a clinical, hands-on dentist. They really know what is going on. But since the middle 1970s or somewhere in there, the dental school faculties have been dominated by fulltime teachers who go to practice a little bit and that changes the whole picture. That changes it even in the sense of the patient-dentist relationship. When you are working on your own patients and you are listening to them, you are really listening to them, number one, and you are making decisions together, number two, and you know little things like if this patient is not happy, they are going to go home and tell seventeen people. Now you either make them happy or you are in big trouble,” he said.

Conversely, he said a sense of accountability tends to be in shorter supply among dentists who teach fulltime because in college dental clinics dentists are not seeing their own patients, they are seeing whoever walks in for treatment, and these patients are apt not to get the same attention they would in a private setting. From where Manhart sits, too, there is something to the old adage, “Those who can, do, and those who can’t, teach.” Therefore, let the buyer beware.

In such a setting, he said, the dentist tends to be insulated from any repercussions that attend substandard care. A gulf or separation existing between dentist and patient is not consistent with quality care. He feels this insularity is engendered, too, in some dentists who belong to the American Dental Association, who use the organization as a buffer. “That insulation makes you act differently,” he said. Less compassionately or less empathetically perhaps. Rather than hide behind an association, Manhart puts himself right out there, taking full ownership of who he is and what he does. “When you go onto the Internet—this is the first thing I found out—you open yourself up to the entire world and a lot of dentists cannot allow themselves to do that,” he said.

Furthermore, Manhart strives to do the most for his patients with the least overhead for fancy equipment. He has developed an array of techniques, products, and applications that treats patients in minimally invasive or entirely noninvasive ways that are also quick and painless. He is efficient enough to get patients in and out of his office in short order but without resorting to shortcuts or rushing through procedures. That is because he has reduced procedures from several steps to just a few steps, eliminating waste, excess, and overkill. Yet he still takes time to actually examine the inside of the patient’s mouth, explain things, ask questions, and lay out options. He is all about finding long-term solutions, not quick fixes. It is the way informed consent is supposed to work, he said.

Arlene Nelson has been a patient of his for nearly forty years, and she appreciates his inclusive approach. “He shows me the X-rays every time. He says, ‘I want you to look at this.’ He just explains things to you and you just get a clear picture of what is going to be done and how long it is going to take and how many treatments or whatever. You feel like you are a part of the improvement. You really are, too. He puts you right in there. You are right there and you are a part of the healing process. He gives you an ear-by-ear, side-by-side walk with the healing,” she said. “He has really done me right. I have just been very pleased. He is very gentle, very sure.”

His old-fashioned approach is something she appreciates. “You know, I kind of like that. Not only that, but I had a tooth that was bothering me that was way in the back, and I actually called him at home on a Sunday and he said, ‘I want you to meet me at the office at one o’clock,’ and I did. I did not ever think I would be calling a dentist at home. It turned out he had someone flying in from wherever for treatment that day. I thought, oh my gosh. He is just so ready to help me. He is my kind of dentist.”

Paul Luc appreciates the holistic way Manhart treats dental problems. A Hong Kong native living and working in Tennessee, he is typical of Manhart’s patients from all over the country, even all over the globe, who have discovered the Calcium Therapy Institute (CTI) via the World Wide Web. Dozens more do every day.

Diagnosed with advanced periodontal disease, Luc studied the CTI website, contacted Manhart, and arranged to come to Omaha for a treatment. People from coast to coast and from overseas venture in every other week. Like so many of Manhart’s patients, Luc came to the Institute after “seeing and consulting with a variety of general dentists and periodontists … the options offered to me were not satisfactory. The mainstream approach may be clinically acceptable, but it is too generic and statistical in nature and not patient- oriented,” said Luc, who is a scientist. “I was searching for a holistic dentist. The trip was everything I had hoped for and more. Dr. Manhart’s approach is entirely patient-oriented. His method of treatment and diagnosis is very practical, realistic, and above all very scientific. There was no pain, no surgery, no blood, no X-ray, and no anesthesia. Within twenty-four hours after the initial treatment, my condition was under control. It improved drastically after two more days of intensive treatment.”

Luc found Manhart’s “genuine concern” encouraging. He also appreciated that Manhart was willing to share his immense knowledge with him, patiently answering his many questions and offering him the best options for his particular needs. Like more and more CTI patients, Luc uses several of its self-care products at home, including the Calcium Toothbrush, the Oral-Cal mouthwash, and the Calcium Chip set. “My gums and teeth are getting better every day. I am really amazed by the power and effectiveness of the simple, common sense approach and solution.”

There is more to the story. Luc was so taken by the results that he began focusing his scientific mind on a practical application for determining the presence of periodontal disease. Long story short, Luc devised a home test that he then presented to Manhart, who immediately saw that his patient had hit upon something worth developing.

“Paul came up with a superb test for periodontal disease,” he said. “It is very neat. He adapted our products in a certain way so that you test yourself at home to tell whether you have periodontal disease or anything to worry about with your gums being infected. Paul is very creative, and he came up with a very clever oxidase process for testing. All I did was tweak it and put it in a sequence of what to do. If we had some company to work with, it could be made very inexpensively with materials we have.”

A doctor being open to accepting an idea from a patient is rare enough. It shows that Manhart is not so high and mighty as to dismiss something a mere civilian suggests or, in this case, invents. He has too often been on the other side himself of being cast as the amateur or dilettante intruding into the holy domain of the experts or specialists. So he knows what it is like to be ridiculed and spurned and not taken seriously. He has a long history of being open to ideas from many quarters.

Manhart found a high standard of care in India

In September 2009 he and Bonnie were presenting the calcium therapies in Nice, France, when one of the attendees answered the following question Manhart posed: “What causes such an infection?” To which a man in the audience responded with, “Thumb sucking.” Manhart, the expert dentist, was bewildered that he had never thought of that explanation.

In his practice Manhart must be a people-person and thus he can turn on the charm and therefore transform the often awkward patient-doctor interaction into a relaxed exchange that disarms patients and makes them collaborators in their own care. Humility goes much further than arrogance he has learned. But with him, there is no ring of phoniness to the interaction. He is genuinely engaged and in the moment with you. You feel his full attention on you.

“I always remember how theatre helped me become a better dentist, because you have to play a role,” he said. “If you go into the office and play the role of a student, people do not buy it. If you cannot play the role of a dentist who is competent, who knows what the hell you are doing even though you maybe have to go in your office and read a little to make sure you know what you are doing, then you are going to fail at it. And it works the other way, too. You learn things on stage that work and make sense that can be applied to your dental work, and one of them for me was that we were always taught in dental school never to say things like, ‘Ooops’ or ‘Sorry, I didn’t mean to cut your lip off.’ You were taught to be impervious to mistakes. Well, it is an everyday thing because you are hurting people every day, and so how do you respond?

“I remember we were taught you never give a person an injection and say, ‘I’m sorry.’ That is heresy or it used to be, maybe it is not so much anymore. I just figured out, no, I have to say that, and so it has gotten to be a habit with me. Almost every time I give someone an injection and I know I have hurt them, I have to say, ‘I’m sorry,’ and it has to be real. That makes a person a better dentist, just simple empathy. Otherwise, it is not believable.”

Just as he has learned that genuineness is a big part of being a healing arts practitioner, he has learned it is equally critical to being an artist on the stage. In each circumstance it is about transparency and professionalism. It is all about being authentic or real. Anything less than that will not hold or convince the audience. People can smell a phony act from a mile away.

He has taken his ability to authentically, transparently engage people a step further by devoting much time to teaching his craft. For four years he was an associate professor at his alma mater, Creighton University Dental School in Omaha. One of his former students, Tom Steg, is now his partner. The two make an interesting contrast. Manhart is the tall, thick figure whose bigger-than-life vibe and presence draws eyes to him. Steg is a slight man with an insular personality and a just-above-a-whisper voice. But where they differ outwardly they share the same probing intellect that enjoys the give- and-take of rigorous inquiry.

For years, Manhart has demonstrated techniques to colleagues at dental conventions across America, even abroad. At various times he conducts seminars for dentists in his office or their offices, turning the quarters into teaching labs where he works on actual patients while dentists and hygienists observe. His work as a clinician-teacher is widely respected because he is not only skilled and informative but knows how to play to the crowd and work a room. He makes eye contact, he changes the inflection of his voice, he pauses for effect, he gestures with the tools of his trade in his hands. Like any good actor or orator, he uses his entire body and whatever props are available as expressive instruments of communication.

Being able to “perform” in front of people when the pressure is on is a knack he developed early on in competitive athletics and refined as a dentist and later in Rotary International and community theatre. The Rotary International website’s “About Us” section describes itself as “the world’s first service club organization, with more than one million members in thousands of clubs worldwide. Rotary club members are volunteers who work locally, regionally, and internationally to combat hunger, improve health and sanitation, provide education and job training, promote peace, and eradicate polio under the motto Service Above Self.”

Sounds like a hand-to-glove fit for Manhart, the man of varied interests, especially when the Rotary site gets around to the part that says “the benefits of a Rotarian include serving the community, networking and friendship, and promoting ethics and leadership skills.” That is Manhart to a tee. He can and did hold his own with Omaha movers-and-shakers when he was active in Rotary. He is not so much active in it anymore, but he still follows the organization’s principles in his private and professional lives.

He suffered stage fright during his first forays in theatre but interacting with patients and with peers as a dentist and getting up and addressing an audience at Rotary meetings helped instill a composure that he then transferred to the stage. In turn, he took what he learned in theatre and applied it to his profession, especially to the public speaking, demonstrations, and teaching he does. “It taught me in a way how to present myself in giving a clinic or giving a lecture. It taught me that talent,” he said.

He remembers the first time he ever went and presented anything in Chicago, host of the dental convention in America. He said, “It is like being on the best stage in dentistry, it really is,” and how much smoother and assured he was in that rarefied environment after honing his public speaking and theatre chops. He likes being on stage, whether in the playhouse or the examination room or the classroom or the convention hall. His hands are sure, his voice steady, his posture erect, and his demeanor confident in these respective arenas. Each is a turf he feels completely comfortable and competent on.

He transferred this same nonplused quality to local cable television, for which he wrote, directed, and hosted talk shows that produced some one hundred programs featuring guests from all walks of life. He developed and hosted a talk show on Omaha’s KLNG Radio for a time. He has also appeared in a number of local TV and radio commercials. The ham in him cannot help it. Besides, he is just one of those high- energy people, as is Bonnie, who has to be doing something.

Add to that his boundless curiosity, his stage presence, and his gift for gab and you have the proverbial talking head.

He is sure there is a correlation between the intuitive breakthroughs that have come to him in dentistry and the creative breakthroughs he has experienced as an actor- writer-director. Breakthroughs only come if you are open and available to them. It means preparing yourself for invention by putting in the work ahead of time and then letting your subconscious take over to incubate and birth ideas when they are ready to emerge.

“To me it is allowing your subconscious to think for you because your subconscious is always going,” he said. “A lot of these discoveries in dentistry were being worked on just like anything else and then suddenly there it was in front of you.”

He recalls the time the idea came to him of how a paper point used in root canals can be coated with calcium. “I always remember there it was right in front of me all along on the bracket table, and I had seen that a thousand times before, but now my subconscious had put two and two together, and I saw that putting the paper point plus the calcium together gave you a wonderful way of getting calcium where you need it—inside the tooth. I really think there are people who do not allow their subconscious to do much for them or they think, If I don’t think of something right now, I am never going to. But the harder you try, the worse it is. That surrender to the subconscious—I will think of it later—is where those discoveries come from. And one kind of discovery leads to discoveries in other fields.”

Manhart demonstrating techniques in Poland

His life in theatre has not only served as an inspiration and gateway for his professional career, it has also served as a buffer and sanctuary from his life in dentistry. For Manhart, there is no greater satisfaction than knowing he has rendered service to patients. But the demands of dentistry, as with any profession, can be taxing. That is why he prizes having the theatre to go to. He can leave the work-a-day world behind in order to lose himself in a realm of make-believe.

“It is such a welcome distraction from dentistry because dentistry would drive any person crazy. The theatre is such a complete change that it’s good for you. It is wonderful to go from the office and go do theatre, and completely forget you are a dentist and really use a lot of your talents and experiences to create something on stage,” he said. “And for so many people, myself included, the theatre is where you discover talents and abilities you never dreamed you had. Theatre is so much a part of the world and you can learn so much from it. In other words, if you can play something on stage and you can do it in front of people and make them a part of what you are doing, you make people laugh and cry and solve their problems … that is irreplaceable.”

“The most fulfilling thing about my involvement in theatre,” he said, “is that I get to show that the world is a stage and it is more rewarding to realize it in different ways than to be lost in a black hole of politics or religion.”

As he says, the theatre can be a place to work things out, such as unresolved issues and emotions. It is a freeing space. Therapeutic even. Seen in that light, it is no accident he has gravitated to the therapeutic side of dentistry. You might say it is his calling. Reading, painting, listening to music, landscaping, dining out, and traveling are other pursuits that help him escape. Tennis used to do the same for him. Before that, as a youth, it was basketball. “Those kinds of things let your other mind work, free it up,” is how he describes it.

Logo for the Grande Olde Players Theatre

His appreciation for the finer things extends to home. The residence he and Bonnie share is an open modern showplace whose many windows bathe the interior in natural light. Their passion for art and music is seen throughout the spacious, muted living quarters, including paintings he has done that hang on the walls and an upright piano in the dining room. They love to entertain, and their jazz nights transform their place into an intimate atmosphere.

Their love of nature and design is expressed in a walkout patio and garden whose landscaping Manhart conceived and executed. His knack for gardening comes from his mother and her proverbial “green thumb.”

The serene yet dynamic living space is an aesthetic retreat that reflects the cultured couple who inhabit it. It is easy to see what drew them there.

“We looked for almost a decade for this home, stumbled on it, and bought it the next day in September of 2000,” he said. “It and the three houses to our east were designed by

Stanley How, who must have been a serious student of Frank Lloyd Wright, the iconic architect of Fallingwater, the most famous residence in modern architecture. The design of our home, which was built in 1963, is nothing less than genius. Its modern layout is for all the senses and weather of this area of the world. The only things we did were move the laundry upstairs, put in some mirrors Wright would have liked and kept it simple and uncluttered. I hope to die in it. We have studied Wright’s architecture a long time and have toured his buildings and homes, especially his Taliesin East and West homes. I see our home as an homage to his concrete, long-lasting contribution to American culture.”

Then, too, there is the life we experience with our own siblings or kids. This is a bit more problematic where Manhart is concerned. He likes children. He fathered and helped raise eight of them, after all. But he has been by his own admission a somewhat distracted parent with a tendency to get caught up in his own activities to the diminution of his kids’. He can also be a bit of a distant curmudgeon who unconsciously withholds the affection and approval that presumably his children, even though they are all grown now with families and careers of their own, still crave from him, the strong, patrician-style patriarch. He also is not inclined to do family things or to attend family reunions unless persuaded or nudged, and then he invariably enjoys the gatherings.

Moreover, there is the life we carry on with friends, with neighbors, with associates, and so on. Manhart can hardly count the lives he has touched in the various guises he has filled, whether as doctor or teacher or speaker or director or friend or neighbor. His has been a long, varied life well- lived and one marked by all the connections he has made with people in his many roles. He likes the many hats he has worn and continues to wear. The fact there are many different constituencies and peer groups he can call his own is a manifestation of his diverse life.

Certainly, each of us leads an intense private existence that exists apart from but not entirely separate from our gainfully employed experience. A life of any length accrues with it a host of endeavors, roles, affiliations, associations, not to mention baggage, of both the personal and professional kind, whose whole is greater than the sum of the parts—each a reflection of different aspects of our self.

If nothing else, the biographical subject of this book, veteran dentist Mark Manhart, leads a rich life that seems a bundle of contradictions upon first glance. Now in his seventies, the native Omahan is equal parts old-fashioned practitioner, alternative dentist, “mad scientist,” artist, pragmatist, dreamer, searcher, connoisseur, businessman, inventor, family man, lover, disciplinarian, libertarian, and iconoclast.

A contemporary of Manhart’s, Father Jim Schwertley of Omaha, once told him, “Manhart, you are just like mercury, just when we think we have got a hold of you, you squirt out someplace else.”

Manhart admits, “That is a fair assessment.” Manhart’s wife said, “I am going to put that (the mercury epitaph) on your tombstone.” That is how “perfect” Bonnie thinks the metaphor is in capturing her mate’s fluidity.

The word mercury comes from the quixotic Greek god of the same name. A derivation of that word is mercurial. One definition of mercurial reads: “being quick and changeable in character.” That is not to suggest Manhart is a chameleon or that he acts a certain way one instant and another way the next, at least not anymore than the rest of us play various roles to suit the company or the occasion or the situation. No, it is just that he is one of those people who cannot be easily pinned down or pigeonholed because he is into so many things and seemingly all over the place at once. So, for the purposes of this bio, he might be dubbed Manhart the Mercurial. It not only has a nice, alliterative ring to it, it happens to accurately describe the man’s multifarious nature.

All are expressions of his different sides and lives. But in truth there is no secret life for Manhart. His life is an open book, relatively. Isn’t everything relative? His very public theatre work has certainly been no secret. His running for the Omaha City Council put him out there on the front lines of public-media scrutiny. His lay leadership in the Omaha Archdiocese made him a lightning rod for church- lay issues. His wholehearted embrace of the Montessori method of early childhood education put him at odds with the local education cabal. His attempts to introduce some of his calcium therapy innovations in the classroom met with stiff resistance and, eventually, resulted in his outright dismissal. His outspoken objection to traditional endodontic and periodontal approaches in favor of noninvasive calcium- based alternatives made him a pariah among dentistry’s specialist community.

The person we become at seventy or seventy-five, if we live long enough to find out, is naturally an accumulation and a conglomeration of everything that has gone on before: the incidents, the milestones, the highs, the lows, the decisions, and the mistakes we made. Our lives are the product of many commissions and omissions. No one is without fault or blame. The best we can do, as Twelve-Step recovery programs phrase it, is to strive for progress, not perfection.

Manhart has something to say about this live-and-let-live ethos, too: “Long, long ago I decided to avoid reliving the past myself or through others, like raising the kids. If I had done one thing different, I would not be here talking about all this. All since would have changed, so history is what it is and regret is a cop out or a waste. I try to learn from the past, repeat the good parts. I love to read history and concentrate on the present, and maybe on tomorrow till about noon. I do not wake till 10 a.m., nor believe in God till after lunch. I try to see people from angles and steal the good sides.”

Related articles

- A Hospice House Story: How Phil Hummel’s End of Life Journey in Hospice Gave His Family Peace of Mind and Granted Him a Gentle, Dignified Death (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Tired of Being Tired Leads to a New Start at the John Beasley Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Theater as Insurrection, Social Commentary and Corporate Training Tool (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Lit Fest: ‘People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Nancy Kirk: Arts Maven, Author, Communicator, Entrepreneur, Interfaith Champion (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Art as Revolution: Brigitte McQueen’s Union for Contemporary Art Reimagines What’s Possible in North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Photographer Jim Krantz and His Artist Grandfather, the Late David Bialac: An Art Conversation Through the Generations (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- An Inner City Exhibition Tells a Wide Range of Stories (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Golden Boy Dick Mueller of Omaha Leads Firehouse Theatre Revival (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Memories of the Jewish Midwest: Mom and Pop Grocery Stores, Omaha, Lincoln, Greater Nebraska and Southwest Iowa (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

The Film Dude, Nik Fackler, goes his own way again, this time to Nepal and Gabon

The Film Dude, Nik Fackler, goes his own way again, this time to Nepal and Gabon to shoot psychotropic documentaries about a young buddha and the Bwiti Culture’s Iboga initiation

©by Leo Adam Biga

As published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Fresh off the warm reception to his debut feature, Lovely, Still, Omaha‘s Film Dude, Nik Fackler, is unexpectedly making his next two film projects documentaries.

Following the path of cinema adventurer Werner Herzog, Fackler’s tramping off to shoot one film in Nepal and the other in Gabon, Africa, drawn to each exotic locale by his magnificent obsession with indigenous cultures and ways.

Fackler, Lovely producer Dana Altman and two other crew left August 11 for Gabon in west central Africa. They plan living weeks with the shamanistic Mitsogo, whose practice of Bwiti involves ingesting the hallucinogenic iboga root. The mind-altering initiation ritual is about healing.

“Part of it is you’ve got to prove yourself to the tribe,” says Fackler. “They don’t just give it to anybody, especially Westerners.”

The extreme project is based in a fascination with and use of ancient, underground medicines and practices.

“I have a great interest in dreams and a great interest in psychedelic experience. I’ve had a lot of healing I’ve gone through using silicide mushrooms,” says Fackler.

A heroin addict friend is along for this exploration.

A quest for spiritual enlightenment brought Fackler and Lovely DP Sean Kirby to Nepal in May to film the end of a six-year fasting and meditative regimen by Dharma Sangha. The filmmakers followed Boy Buddha’s exodus, with tens of thousands of followers gathered, and plan returning in the fall.

Fackler is tackling the unlikely projects while awaiting financing for his next two narrative features: an untitled puppet film with illustrator Tony Millionaire; and a phantasmagorical mythology pic called We the Living.

The docs square nicely with Fackler’s eclectic interests in alternative therapies and philosophies.

Dharma Sangha

“I’m always searching. There’s so many beautiful cultures out there. I have to explore and learn as much as I possibly can. I have to go out there to discover them, document them, before they disappear into the weird one-world culture we’re heading towards.”

Mere days before leaving for Africa he still wasn’t sure the Bwiti cultists were on board, but put his faith in miracles.

“I suppose I’m in the mindset of looking at everything in a magical way rather than an intellectual way. That’s sort of where I need to be to make a film like this.”

Related articles

- Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (wornjournal.com)

- Gabon leader wants Obama to spotlight Africa (sfgate.com)

- New search for missing US trekker in Nepal (sfgate.com)

- Omowale Akintunde’s In-Your-Face Race Film for the New Millennium, ‘Wigger,’ Introduces America to a New Cinema Voice (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- African Shamanism (raymondjclements.wordpress.com)

Bob Kerrey weighs in on PTSD, old wars, new wars, endings and new beginnings

For many Nebraskans, myself included, Bob Kerrey has always been a fascinating figure. Unusual for a politician from this state, he exuded a charisma, some of it no doubt innate and genuine, and some of it I suspect the reflected after glow of our idealized projections. As a combat war veteran who overcame the loss of a leg in service to his country, he was a valiant survivor . As a brash political upstart and liberal Democrat in solidly conservative and old-boy-network Republican Nebraska his was a new voice. His good-looks and suave ways gave him a certain It appeal. When he landed in the governor’s office and struck up a romance with actress Debra Winger, who was in state to shoot scenes for the film Terms of Endearment, it only confirmed Kerrey as a rising star and player in his own right. His long career in the U.S. Senate is probably most memorable for the number of times he was mentioned as a possible candidate for the Democratic presidential nominee race. He did end up running but it soon became clear his magic did not resonate with the masses. More recently, he dealt with the unpleasant truth of hard things his unit did during the Vietnam War. He left the political arena for a university presidency only to find himself at odds with faculty and student groups who eventually called for his ouster. As he prepares to leave the world of academics for some as yet unnamed new venture, he seems like a lot of us who come to a point in life where it’s time for reinvention and renewal. The following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) is obstensibly a sampler of his views on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder as it relates to active duty military and war veterans, but it also serves as a look into how he approaches and articulates issues. I also have him weigh in on the Tucson shooting. At the end of the piece I address some of the currents in his professional life that find him, if not adrift exactly, then searching for a new normal.

Bob Kerrey weighs in on PTSD, old wars, new wars, Eedings and new beginnings

©by Leo Adam Biga

Published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Vietnam war veteran and former Nebraska governor and U.S. Senator Bob Kerrey will be in Omaha Jan. 31 to salute At Ease, an Omaha program providing confidential behavioral health services to active duty military personnel and family members.

Founded by Omaha advertising executive Scott Anderson, At Ease is administered by Lutheran Family Services of Nebraska. Kerrey, whose embattled New School (New York) presidency ended January 1, is the featured speaker for the At Ease benefit luncheon at Qwest Center Omaha.

Reports estimate up to one in five Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans — some 300,000 individuals — suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or major depression. Controversy over strict U.S. Veterans Administration guidelines for PTSD claims has led to new rules that lessen diagnostic requirements and streamline benefits processing.

Last summer Kerrey, a board member with the Iraq and Afghan Veterans of America (IAVA), publicly criticized a VA policy banning its physicians from recommending medical marijuana to patients.

“There are doctors who are strongly of the view that marijuana prescribed and monitored can be beneficial for a number of physical and mental conditions,” he says. “And in those states where medical marijuana is legal I think the VA should allow it.

“If a doctor can prescribe medical marijuana for somebody who’s not a veteran, it doesn’t seem to me to be right for that doctor not to be able to prescribe it for a veteran.”

Kerrey, speaking by phone, says he keeps fairly close tabs on veterans’ affairs.

“I would say I stay more current on veterans health and veterans issues than I do on other issues. I’ve made a few calls on the Veterans Bill of Rights that (Sen.) Jim Webb pushed. I get called from time to time to help people that are having problems. It’s much harder to help somebody when you’re not holding the power of a senate office or a governor’s office.”

Kerrey strongly advocates the work of IAVA, founded in 2004 by Paul Rieckhoff, a former Army First Lieutenant and infantry rifle platoon leader in Iraq.

“It’s a very good organization for any Iraq or Afghan veteran that’s looking for somebody they can talk to,” says Kerrey. “They’re very careful not to duplicate what the VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) and the DAV (Disabled American Veterans) and the (American) Legion are doing.

“They don’t have buildings, they just have basically networks of Iraq and Afghan veterans who are trying to help each other.”

He suggests the number of veterans needing help for PTSD is so vast that only a combined public-private initiatives can adequately address the problem.

“You start off with an estimate of 300,000 PTSD sufferers from Iraq and Afghanistan and multiply by it two or three, depending on how many family members are going to be affected, and you’re talking about maybe a million people,” he says.

“This is a difficult thing for the Veterans Administration or other government entities to handle all by themselves. Non-governmental efforts are typically supplemental — all by themselves they’re not going to get the job done (either).”

He views At Ease as a non-governmental response that can help address problems at the local level.

“It’s hard to figure out what to do for a million, but if you’re talking about 50 or 60 or a hundred or just one, there’s something you can do, and that’s what At Ease is doing through Lutheran Family Services. It’s a great example of how when you say, I’d like to do something to help, there are venues, there are ways to help. It’s a terrific story.”

His remarks at the fund raiser will make that very point.

“My focus will be on how possible it is for a single individual, in this case Scott Anderson, a nonmilitary citizen with no direct contact with PTSD, to do something. And his program’ saved lives, it’s made lives better.”

In this belt-tightening era, Kerrey says nonprofit-volunteer efforts can make an especially vital impact.

“We hear so much about things unique to America that there’s a tendency at times to be skeptical. But our nation’s volunteer, not-for-profit efforts are unique in the world. The financial and volunteer time giving that occurs is a real source of strength that doesn’t show up on economic analyses,” he says, adding that veterans’ problems are “not going to be made easier if in a moment of budget cuts we cut back on mental health services.”

Attitudes about mental health disorders are much different now than when he returned from combat in Vietnam, where he led a Navy SEAL team. Kerrey was awarded the Medal of Honor. Thankfully, he says, the stigma of PTSD is not what it used to be.

“First of all, I think mental illness is seen much differently today — much more mainstream, much more comparable to physical illness. I think you’d probably have a hard time finding somebody in Nebraska that doesn’t have somebody who’s experienced a trauma producing some kind of disability.

“I would say the mental trauma is in a demonstrable way more disabling than the physical trauma. And the two can be connected. I think generally today people accept that. I’m sure there’s still a lot of people who think of PTSD as connected to Vietnam but I think that’s the exception rather than the rule. The rule is it’s seen more broadly as a condition that can affect anybody, both in and out of combat.”

Repeated deployments in Iraq and Afghan, he says, have added new stressors for “guys rotating in and out multiple times. It’s one thing to go over your first time and wonder whether or not an IED is going to take you out, but to have to go over a second, a third, a fourth (time) — at some point it has to harden you when you get home. It has to have a terrible impact on you.”

He believes whatever care veterans receive must be personal and consistent.

“The most important thing is sustained support because what you need is somebody you can call when you’re having trouble,” he says.

Although he never suffered PTSD, he dealt with losing a limb and adjusting to a prosthesis. He endured physical pain and memory-induced night sweats. He says while recovering from his injuries “some of the most important things given to me were by volunteers who would just come in and say, ‘It’s going to be all right.’ It’s extremely important for another human being to be there and demonstrate they care enough about you to spend time with you.”

On other topics, Kerrey says the recent Tucson shooting may hold cautionary lessons. Alleged gunman Jared Lee Loughner made threats against his target, Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, a Democrat sharply criticized by the Right. Kerrey says while rhetoric is part of this society’s free exchange of ideas, labeling an elected official a danger may trigger an unstable person to act violently.

Meanwhile, Kerrey, who was to have remained New School president through July, has given way to David Van Zandt. Kerrey remains affiliated with the school. His fate as president was sealed when senior faculty returned a 2009 no-confidence vote. Until last summer Kerrey had been in negotiations with the Motion Picture Association of America to become the trade group’s president.

About his New School experience, he says, “I’m grateful for the chance to have done it. I learned a lot. I got a lot done. I made a lot of friends.” He also ran afoul of vocal student-faculty blocs. His well-known political skills failed him in the end.

“I certainly didn’t expect my term as university president was going to be free of situations where something was going to be upsetting. I was not an altogether cooperative student when I went to the University of Nebraska. I’ve seen university presidents hounded, harassed, criticized before I became one, so it didn’t really surprise me.”

With the MPAA no longer courting him, Kerrey says he’s looking to do “something in public service — something I think is not going to get done unless I do it,” adding, “It’s much more likely I’m going to be spending more time back there (Nebraska).”

Related articles

- PTSD Programs for Families (vabenefitblog.com)

- What are the signs of PTSD? (zocdoc.com)

- PTSD Affects Entire Families – Caring for the Caregivers (offthebase.wordpress.com)

- Advice for Parents of PTSD Soldiers (brighthub.com)

- Former SEAL Team Six Member Releases An Incredibly Well-Timed Memoir (mediaite.com)

- Bob Kerrey: Why Washington Isn’t Working for the American People (huffingtonpost.com)

Unforgettable Patricia Neal