I have been meaning to post this story for some time and only now got around to it. It’s a Reader (www.thereader.com) cover story from 1999 that takes a look back at the Omaha Stockyards only months before the whole works closed and was razed. Its demise, after years of decline following decades of booming business, ended a big brawny empire that at its peak was a major economic engine and a dominant part of the South Omaha landscape. I interviewed several men and one woman whose lives were bound up in the place and they paint a picture of a city within a city about which they felt great pride and nostalgia. The Stockyards was its own culture. These stockmen and this stockwoman were sad seeing it all go away, as if it was never there. Around that same time, I wrote a second depth story about the Stockyards for the New Horizons that gave even more of a feel for the scale of operation it once maintained. Here is a link to that story–

From the Archives: An Ode to the Omaha Stockyards

It was a different breed then: Omaha Stockyards remembered

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Unfolding a stone’s thrown away from a South Omaha strip mall is a scene straight out of the Old West. A sturdy codger called B.J. drives a dozen burnt orange cows through a mosaic of wooden pens and metal gates. As he flogs the recalcitrant beasts with a whip, his sing-song voice calls to them in a lingo only wranglers know.

“Hey, hey, hey, hey, hey…yeh, yeh, yeh…Whoa! Get up there. Whoa! Yeh, yeh, yeh…Go, get up there. High, high, high, high. Whoa. Gip, gip, gip, gip…High, high, high, high…Yeh, yeh, yeh, yeh…C’mon, babies. C’mon, sweethearts. C’mon, darlings. Get up there.”

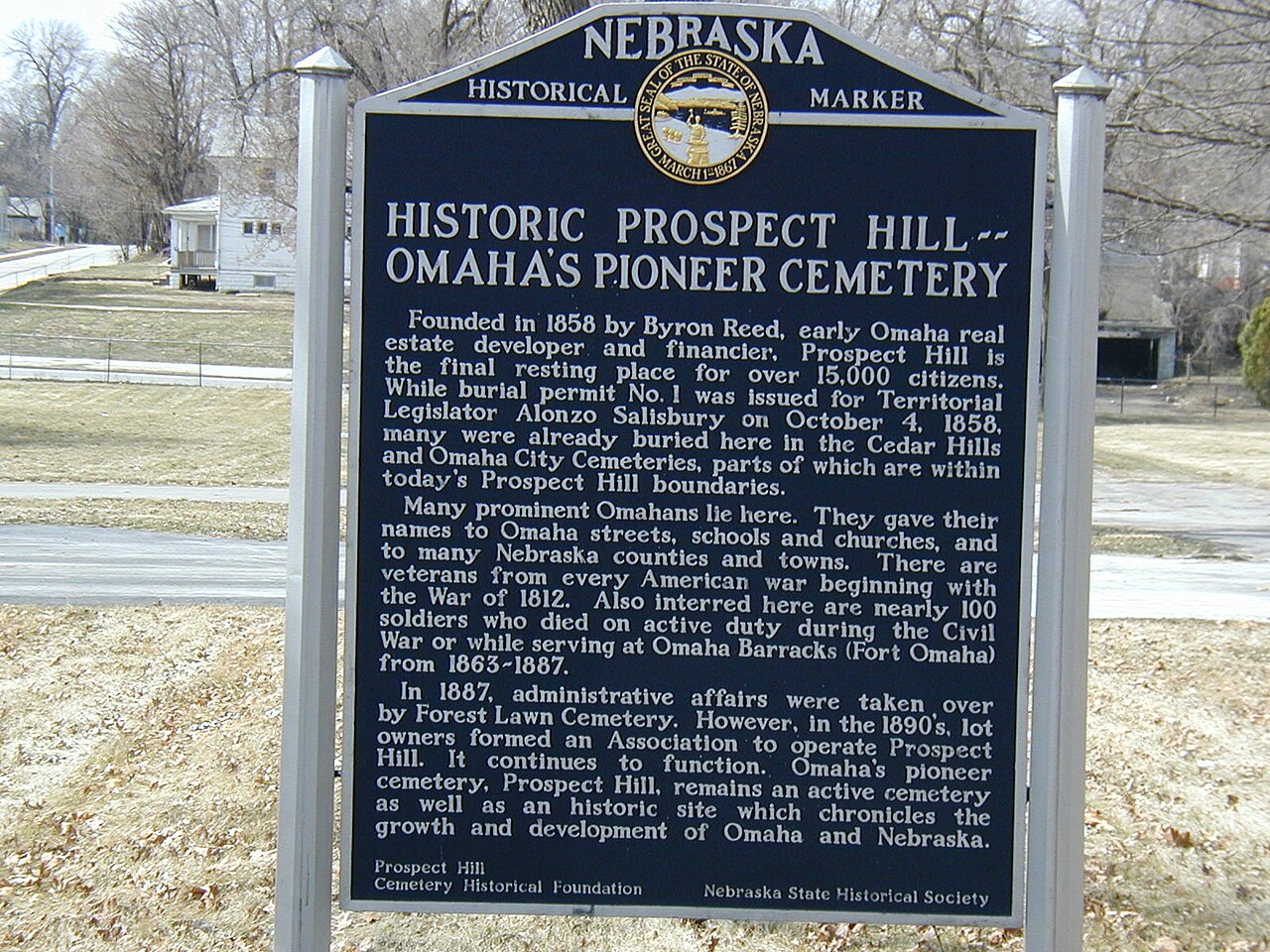

Welcome to the Omaha Stockyards, a once immense marketplace and meatpacking center which, owing to changing marketing trends and public attitudes, has gone to rack and ruin. Since 1997, when Mayor Hal Daub announced a city-led plan to buy the site, raze nearly the entire complex and redevelop it, the Omaha Livestock Market, which operates the yards, has been marking time. In March, market staff and traders vacated offices in the Livestock Exchange Building and have since taken up makeshift quarters in a nearby cinder-block structure. The yards are expected to close early this fall, possibly by October, and the market will move from the site it has operated at for 116 years and re-open in Red Oak, Iowa. Just as the Stockyards will soon disappear, its halcyon days are now distant memories.

But for survivors of those times, like Bernie J. McCoy, the past is very much alive. As painful as the impending end is for them, they revel in the spirit of the people who worked there and their special way of doing business. To the hard physical labor performed, the injuries incurred, the grueling dawn to dusk schedule and harsh elements endured.

“You had to want to be here and work those long hours. It was a different breed then,” McCoy says.

Yes, the fat times are long gone, never to return, but their legacy lives on in the work McCoy and others still do there. They retrace the very paths taken by countless others before them, forging a direct link to the area’s frontier past. In the yards’ cavernous, skeleton-like environs, McCoy’s voice blends with the sound of bawling calves, squealing hogs and creaking gates to resonate like the mourning, wailing echo of restless souls from long ago. Requiem for the Stockyards.

Recently, McCoy and some fellow Stockyards veterans recounted for The Reader the good old days at this soon to be vanished landmark. Their memories unveil a rich, vibrant, muscular chapter of Omaha’s working life well worth preseving. Their words celebrate an enterprise that dominated the landscape and shaped the city unlike no other. Where the once overbrimming yards pulsed with the lifeblood of Omaha’s economy, it is now a relic condemned to the scrap heap – a decript place largely given over to pigeons and rats. Blocks of abandoned, weed-strewn pens stand empty. Crumbling, sagging buildings blight the landscape. Where it took hundreds of men many hours to drive, feed, water, sort, weigh, trade and load livestock daily, now all activity unfolds in an hour or two amid a dozen pens holding perhaps a hundred cattle, a few hands putting them through their paces.

The traffic whooshing past on L Street overhead is a metaphor for how this forsaken former juggernaut has been passed by in the wake of progress, leaving it an anachronism in a city grown intolerant. Yet, it lingers still – a ghostly visage of another era.

By the close of 1999 only tracts of of dilapidated pens and barren livestock barns will remain. Soon even these meager traces will vanish when the city levels the whole works in a year or two. leaving only the looming presence of the massive Exchange Building – for decades the focal point and symbol of the sprawling , booming market. Even its future is not secure, hinging on if if developers find financing for its pricey renovation.

We helped build this city

Today, from atop the weather-beaten wooden high walk spanning the grounds, it’s hard imagining when the yards teemed with enough acitivty to make it the largest livestock market/meatpacking center in the nation. Oh, animals still arrive at market every week but comprise only a trickle of the mighty stream that once flowed around the clock.

Unless you’re pushing middle age, you never saw the Stockyards at its peak. When tens of thousands of cattle, hogs and sheep arrived daily by rail and truck. Millions of animals a year. All transactions, each worth many thousands of dollars, were consummated by word of mouth alone. Trading generated millions of dollars a day, perhaps billions over time.

Livestock were sold primarily to the big four packing plants and the many smaller independent plants then dotting the yards’ perimeter. Stock were also shipped to other parts of the country, even overseas. The place was once so big, its impact so vast, that the Omaha market helped set the prices for the industry nationwide and ran its own radio station and newspaper. As a center of commerce, the Stockyards ruled. At their peak, the packing plants employed more than 10,000 laborers. The Stockyards company itself employed hundreds, including office staff to manage the business as well as outdoor crews to handle animals, maintain pens, chutes and barns and run its own railroad line. Hundreds more did business there as livestock commission salesmen, order-buyers, inspectors, et cetera. The people converging there on any trading today ranged from frugal farmers to rough-hewn truckers to smooth-talking traders to well-heeled bankers.

Besides being THE meeting place for anyone who was anybody in the agriculture industry, the Exchange Building offered an oasis of comfort with its cafeteria, dining room, ballroom, bar, soda fountain, cigar stand and barbershop. Basement showers let you wash the stink off but somehow you always knew when a hog man was around. Nearby watering holes, eateries, stores and hotels catered to the stock trade’s every pleasure. The aroma of sweat, blood, manure, hay, grain, cologne, whiskey and tobacco created what Omaha historian Jean Dunbar calls, “The smell of money.”

“Fifty years ago the Stockyards and packing plants were the hub of Omaha, Nebraska. Nowadays, young people don’t appreciate what the Union Stockyards Company did for Omaha. We helped build this city. Everyone wanted to work here. You don’t know the pride we had. Come November, there will be nothing left to remember we were ever here or even existed. Nothing,” declares McCoy, 69, a livestock dealer who’s worked at the Omaha Stockyards for 54 years.

Aerial stockyards, circa 1950. Photo provided by the Douglas County Historical Society.

Chicken plant. Photo provided by the Douglas County Historical Society.

Meat inspectors. Photo provided by the Douglas County Historical Society.

Omaha: World’s largest livestock and meat-packing center. Photo provided by the Douglas County Historical Society.

Ak-Sar-Ben stockyard judging pens. Photo provided by the Douglas County Historical Society.

Stockyard view of the pens, circa 1927. Photo provided by the Douglas County Historical Society.

Trucks backed up to chutes, circa 1926. Photo provided by the Douglas County Historical Society.

Wentworth stockyards. Photo provided by the Douglas County Historical Society.

It was the people

From 1934 to 1969 Doris Wellman, 83, was one of the few women executives in the livestock trading business. Her ties to the place run deep. Her grandfather and father worked there, as did her late husband Ralph and his grandfather and father before him. Incidentally, she never minded the stench because she never forgot “that was my bread and butter.” Above all, the genuineness and the esprit de corps of the people there impressed her. “Every man at that Stockyards was a gentleman as far as I’m concerned. Everybody was always very cordial to you. Everybody spoke to everybody else. There was nothing phony about it. We had our own little community there. That camraderie you will never find anyplace else.”

“When someone was in the least anount of distress,” she adds, “a collection was taken up.” McCoy says, “One trip through the Exchange Building might net 10 or 15,000 dollars,” like the time enough funds were raised to stop foreclosure on Carl “Swede” Anderson’s house.

“Of course, it was the people that made the Stockyards. They took care of their own. That’s what I miss more than anything about it,” says Jim Egan, 66, whose memory of the place goes back before World War II, when as a boy he hung around his father, a livestock order-buyer. Egan later became a livestock dealer himself. “I kind of grew up there as a little kid. I looked up to the head cattle buyers for the big packers, but they were as common as could be. They didn’t look down at anybody. There was never any airs put on. Absolutely not.”

Not that there wasn’t a caste system owing to one’s position and seniority. “There was kind of a pecking order,” Egan says. The more experienced men bought and sold the prime, top-dollar beef, while the green ones learned the trade from the bottom up. Those who carried the most weight and the longest length of service, he says, earned a wider berth, a choicer selection and a primer office location. “Back in the ’50s the head cattle buyers with Armour. Swift and Wilson all wore suits and ties. They had on boots, too, in those days. If you wanted to sell one some cattle you didn’t call him by his first name – it was Mister,” says Ron Ryhisky, 63, a packer-buyer now in his 46th year at the yards. “They thought they were God,” says cattle seller Art Stolinski, who adds that cattle buyers were made even more intimidating by working on horseback.

Men only advanced after an apprenticeship learning breeds, grades, weights. “I drove cattle 10 years for Omaha Packing Co. before I got a chance to buy a few cows, Ryhisky says. Stolinski, now in his 61st year, adds, “I came to work as a yardman for my father. I was a gofer – I cleaned pens, I shook hay, I drove cattle. That’s how you came up the ladder.”

Doing business

Haggling in the yards got heated. Bidding became a pitched battle. Harsh words exchanged between buyers and sellers were soon forgotten though because everyone understood being an S.O.B was just part of doing business. “That was the other guy’s way of trying to beat you,” Ryhisky says. “Sure, the guys argued and everything, but as soon as the trade was done, it was done. Nobody stayed mad,” Egan notes. He adds that men cursing each other over the price of bulls played cards or shared a meal and some drinks a few hours later.

Egan found no “softies” among buyers. “The only time they’d be a soft touch is if they were really desperate for cattle.” Stolinski says some shippers made for tough customers. “Some guys were just hard to sell for. They’d go, ‘Well, that ain’t enough. Get more. Them cattle are worth more than that.’ So you didn’t sell them cattle and then risked not getting them sold for what they were bid, and getting set.”

Like any other traded commodity, livestock were subject to supply and demand dynamics. As Egan explains, “The buyer was trying to buy the cattle for as cheap as he could. The salesman was trying to get as much as he could for his customer. Both knew pretty close where those cattle were going to sell. When it got right down to the nitty-gritty, if the buyer had another load of cattle he thought he could get, then he probably had a little leverage. If he didn’t, then the man selling the cattle had the leverage. That knowledge moved around the yards fairly quick.”

One way the latest market updates and bid orders reached buyers and sellers was by runners. “The packer might decide to take off 50 cents or a dollar (per hundred pounds) and the only way to tell those buyers was to send a runner, usually some kid, who’d run around that high walk trying to get the word to the cow buyers, the heifer buyers, the steer buyers. That kid was running, too,” Stolinski says. “When you saw that kid running fast, you knew he had something to tell the packer-buyer.” Later, radio transmitters replaced runners.

Ball-busting tactics aside, the yards brooked no dirty deeds. As soon as a swindler got exposed for “welshing on a deal,” Egan says, the word spread and he was banned. “You’d never get another animal.”

“If you were a cheat,” Ryhisky adds, “you never came back in.”

Badmouthing a competitor was strictly taboo. Wellman explains, “I can remember whenever my husband Ralph hired a cattle salesman the first thing he told him was, ‘When you go to the country to solicit business, don’t knock any of your opponents. Every knock is a boost. I never want to hear you maligned another commission man on the road.’ We trained people like that and they grew up knowing that’s the way to do business.”

A sense of trust and fair play permeated the yards. It’s what allowed trading to unfold entirely by spoken word – with no written contracts. A man’s word or handshake was enough. It’s still done that way.

“The uniqueness of the way business was conducted,” distinguished the stockyards industry,” Egan says. “Everything was done by word of mouth. It was an honor system you adhered to. It’s just the way it was.”

“Integrity is a word that comes to mind. Anyone that was here any time at all had it. There was nothing signed,” Stolinski says, adding sarcastically, “Now, you go buy a necktie and you gotta make three copies.”

As Wellman put it, “Do you of another business where you can transact millions of dollars worth of business everyday without signing a paper? Where you word is your bond, and if it isn’t, you won’t last?”

According to Gene Miller, a long-time commission man, any livestock deal was the sole province of the buyer and seller. The shipper or producer who consigned his livestock for sell to a commission firm was usually present but only participated if the salesman conferred on the bid. Rare disputes were mediated before a board of livestock exchange officials. “It was up to the buyer and seller to settle. If they couldn’t settle then they went before the Livestock Exchange Board. At any rate, your word had to be all of it or otherwise you had no market.”

Consistent with its open market concept, the Stockyards brought many buyers and sellers together in one spot to arrive at the fairest market price. A single load of cattle might be shown to and bid on by any number of buyers. To prevent a free-for-all, rules governed the bidding process.

If a buyer looked at a load of cattle and made a bid that the salesman accepted, the buyer was bound to take them. However, if the buyer left the salesman’s alley before the bid was accepted, the buyer was not obligated. Similarly, Egan explains, “If a guy was buying, say, steers and another order-buyer or packer-buyer came along, he had to wait outside the alley until the salesman got through showing that first buyer. If the salesman got the price, he might sell a load of cattle to the first guy that looked at ’em. But that buyer wouldn’t sit on a load of cattle and let everybody in the Stockyards look at ’em because he’s got the pressure of the second buyer breathing down his neck.”

Once cattle arrived at the yards, they were usually bedded down a night before traded. The idea was to feed and water stock in order to put weight back on lost (shrinkage) during shipping. While the market didn’t open until 8 or 8:30 a.m., commission men started their workday by 4:30 or 5 in order to get the cattled consigned to them out of holding pens and driven to their firms’ alleys and pens. As the cattle were locked up, sales agents had to find a “key man” at the yards to unlock the pens. Each saleman hustled to get his cattle released ahead of the others.

Stolinski says tempers often flared over who was first in line. “If he happened to be bigger than you, you wouldn’t argue, but some of that happened, too.”

The volume of livestock being traded was so thick that men often had to wait hours in line to get their bunch released or weighed. Each time cattled were moved they were counted, a serious business too given the sheer numbers of animals and the hefty dollar values they represented. A paper trail of receipts and weigh bills followed each load.

Livestock being led to a local packinghouse were driven through an underground tunnel. To help track each load chalk marks were applied to animals. Aptly named Judas goats were used to lead the packs, mostly sheep, placidly through. Steers were run through to chase out the foot-long rats. To control fighting bulls cows were often mixed in. Even with this confluence of activity – trucks and trains arriving and departing and assorted livestock being sorted and driven through a mazework of pens – the stockmen agree there were few major screwups. “It was amazing to me that with the thousands and thousands of livestock that moved through here, we kept them straight,” says Carl Hatcher, a 44-year veteran of the yards and today manager of the Omaha Livestock Market.

“It was amazing how few miscounts we had,” Stolinski says.

More amazing still because despite the paper trail dealers kept most of the figures in their head. “When I went to work for my dad I came out with a tab and pencil and started writing stuff down, and he said, ‘Throw that away. If you have to start writing everything down, forget it. Learn to remember.’ You did,” Stolinski recalls. “You developed your memory that way. Even now, I can remember cattle I sold a couple weeks ago – what they were, what they brought, what they weighed. A lot of buyers could just look at cattle and remember, too.”

In this January 1942 photo, a line of cattle trucks extended 4 miles at the Omaha Stockyards. THE WORLD-HERALD

Out of harm’s way

As smoothly as it all ran, some things could still foul up the works, like one of the 11 scales breaking or an animal going down and not being able to get back up. Then there were close calls with ornery animals. Some broke containment, leaping fences and escaping into surrounding streets, where crews shooed them into the yards or cowboys roped and dragged them back. The wildest ones were shot dead. A mean animal in an alley or a pen sent men scurrying for the fences; the lucky ones clambered atop unscathed; the less fortunate ones got pinned, stomped or gored. Every man can tell you about his close calls and rough scrapes. Harold Hunter, a 78 year old cattle delaer who’s been hit by a heifer and rolled by a bull, among other things since his 1944 start, recalls, “I’d only been here two weeks when I was holding a gate while my boss was on a horse sortin’ these steers. They were probably 3 and 4 year-olds, weighing 1,250, and they moved fast. Two of ’em went by me just like that. My boss said, ‘Kid, they ain’t going to hurt you, just stop ’em.’ Well, the next one went right through the gate and broke it down. Those western range cattle had never seen a man on foot, They respected a horse, but not a man on foot.”

It paid knowing how to stay out of harm’s way. “If you had the gate,” Stolinski says, “you didn’t get behind it to hold ’em back because they’d hit that gate and you’d go with it. You always had to have that gate on the side of you, so when they hit it the gate went and you climbed up the fence…maybe.”

Hatcher, who saw plenty of busted noses and broken bones from swinging gates, says you were well advised “to have your escape route” planned. “Like when we unloaded cattle off the box cars, the way the railroad set the cars , they wouldn’t match up with the opening into the chute. Well, when you’d open a box car door and flop a board in for them to come out, you hoped you could shout and move ’em into the chute opening. But sometimes they’d get upset seeing the fences and turn the wrong way and go down the dock where you were standing. One night a fellow named Dale Castor was there with our night foreman, Orlin Emley, when some old western wild cows came out and turned down the dock, Emley already had the escape route figured. He was climbing the fence when Castor, who hadn’t figured his out, grabbed a hold of Emley and tried to crawl right up his back. Emley was shouting, ‘Get off me, find your own goddamn fence.’ That happened a lot.

“The sound of a gate slamming or people yelling can cause soome animals to run over or through everything they can fin. A wild or mean one like that won’t stop no matter how much you yell or wave a stick or whip or cane or anything else. You know which ones are comin’ out lookin’ for you. you can’t top ’em. You look for your spot on the fence and keep your distance. You gotta know what your doin’ and pay attention.”

Egan says hard to handle animals were often red-flagged on the paperwork accompanying them to give men a heads-up warning.

The risk of injury never goes away. Only two years ago Bernie McCoy had a run-in with a heifer that left him with three cracked ribs. There’s no end of hazards either. Try negotiating a narrow, icy, wind-swept high walk in winter. Or lashing a cow with a whip and a piece of leather tearing off into your face or leg. “It’s like getting shot with a pellet gun,” says Stolinski.

Bulls, because of their size and disposition, pose real trouble. As Stolinski says, “If a bull hits you, he don’t (sic) let you fall to the ground. He just keeps hittin’ you into the fence. Gettin’ kicked would hobble you most because you either got it in the knee or hip.”

But other animals could hurt you, too. Stolinski recalls a yardman named Dale Lovitt who had a leg ripped open by a boar in the hog yards and, true to the stockmen’s macho creed, got stitched and returned for a snort.

“They took him to the hospital, sewed him up, and he got back here and went rght to the bar and had a shot.”

Hatcher witnessed the grit of yardman Hubert Clatterbuck, who took a nasty spill “when the wild horse he was training reared up. causing him to lose his balance. He went right over the back of the horse and fell right on the concrete in the alley…landing on his shoulders and head. Hell, I thought sure he was dead. I called a rescue unit but, shoot, he just shook it off.”

You gotta have it in you

“The hours got terrible with the commission firms, let me tell you,” says Gene Miller. “Today, you couldn’t pay any man enough to work the way we did, and those hours, 5 a.m. to 9 p.m. The hours were too long . The work was too hard. It was seven days a week.” Yet, to a man, they say they don’t regret any of it. Not one hour or day.

And Bernie McCoy adds, “You were always moving,” whether fetching cattle from the hill (the west yards stretching clear to 36th Street) or driving them to the hole (the sloping southwestern yards). “I don’t how many miles we walked a day,” Ryhisky adds. The work went on regardless of the weather. “Sometiimes the conditions were just just rotten,” Stolinski notes. “Standing out there weighing cattle when it was rainy and sloppy like hell. The cattle snapped their hoofs in a puddle and it would splash all over you. We didn’t have rain suits in those days. You had a jacket and you just got wet. You had to keep just working. There wasn’t time to go in and change because those cattle had to be weighed in so many minutes.”

Away from the yards, commission men traveled weekends soliciting business from farmers and ranchers. It was not uncommon for a salesman to put 40,000 miles a year on his car. Since the advent of direct selling in the ’60s. packer-buyers like Ryhisky now solicit customers.

Yardmen have always had it the roughest, facing the same risks from animals and the same dismal weather conditions while building and repairing pens, throwing bales of hay, cleaning alleys and chutes, et cetera. “You gotta have it in you,” Stolinski says. Plenty haven’t. Hatcher saw many men quit after a day or two slogging through muck and shoveling manure. He says the worst jobs included clearing snow atop the auto park, aka, Hurricane Deck, in the winter and picking up animal dumps and hauling them away in the summer.

Stockmen’s and farmers’ and truckers’ hotel near Union Stockyards. South Omaha

They played hard

After a hard day’s work or big sell, men unwound bending an elbow at nearby gin joints. A few braced themselves before punching in each morning, like notable imbiber Claude Dunning, who is said to have drained a half-pint daily before the market even opened. “Some of the old guys would walk in the front of the building, make a left turn into the bar and get a drink of whiskey, then change clothes and off they’d go,” Stolinski says. “Most of the commission men had charge accounts in the bar. If you were a regular, they’d give you a second shot free.”

Fights inevitably broke out.

“They played hard,” Hatcher says, so much so the yard company cracked down. Still, there were ways, like riding in the caboose of a train shipping bulls to Chicago. Two men went along to see the bulls go watered and got tanked themselves on a case of beer. “We had fun,” Ryhisky says.

Other diversions ranged from regular craps and gin rummy games to sports betting. Once, the Stockyards took up a collection to bankroll local gin rummey king Art Jensen, a livestock trader, for a Las Vegas tournament. “They bought shares in him,” Jim Egan says. “He lost.” A good friend of Jensen’s was future Nevada gambling maven Jackie Gaughan, then a bookmaker, who allegedly used a livestock trading office as a bookie front. “You could get a lot of bets laid down there,” recounts Egan. Legend has it local stockmen sold cattle on a cash-only basis to one shady character back east who reputedly once brought a suitcase with $250,000. It’s said the fellow eventually ran afoul of the mob and was killed.

Francis “Doc” Stejskal, a former livestock commission salesman and later a packer-buyer, says people at the yards were not necessarily the raucous bunch many outsiders assumed. “I think a lot of folks thought it was rough and rowdy. That when business was over we all went down to some South Omaha cathouse. It wasn’t that way.”

Doris Wellman adds, “It was the wrong interpretation completely.” That’s not to say there weren’t establishments where women of ill repute rendered certain illicit services. “The dollies were in the Miller Hotel. The guys would take care of things there,” Harold Hunter says. “Big Irene” is said to have been a favorite among johns frequenting the whorehouses and clip joints comprising South O’s red light district.

Those who could not control their appetites were brought down. “Wine, whiskey and women ruined quite a few guys out here,” Ron Ryhisky contends. “I’d hate to have seen the casinos here back in the ’50s. We would have had a lot of broke men.” Adds Stolinski, “A lot of money was made and a lot of good men were lost to high living.”

But for most a big night on the town meant downing a few drinks and eating a hearty meal at Johnny’s Cafe, where stockmen had carte blanche. Many a farmer came to market with his family. While his stock was traded his family waited in the Exchange Building and later, fat check in hand, they went for a shopping spree. Philip’s Department Store was a favorite stop. In an industry that was a crossroads for people from nearly every strata of society – rural-urban, rich-poor – the Stockyards saw its share of memorable characters. Take Gilley Swanson, for instance. The stockmen say Swanson, a farmer, had such utter disregard for his own hygeine that he was infested with lice and slept in the yards’ hay manger. It got so bad, they say, that he was barred from the Exchange Building and people steered clear of his approach. Then there was Bernard Pauley, a mammoth shipper who overwhelmed his bib overalls and had a habit of stepping right from the feedyard into his latest Cadillac, soiling the interior. Forbidden from drinking at home by his wife, he went on benders in the big city, buying endless rounds for himself and his cronies.

Looks could be deceiving. A rancher might pass for a ripe vagrant after traveling by rail with his cattle, yet could pocket enough from one sale to pay cash for a new car and still have ample money left over. Eastern dudes passing through often didn’t know one end of a cow from the other, but knew balance sheets and some say the New York-based Kay Corp., which bought the ailing ards in 1973, simply wrote it off.

These are Stockyards people

Then, as now, money talked. For decades the Stockyards pumped the fuel powering Omaha’s economic engine. Sotuh Omaha owed its existence to the place. The Stockyards wielded power and commanded respect via the jobs it provided, the charitable works its 400 Club performed, the goodwill tours its members made and the boards its executives served on. This far-reaching impact is why stockmen feel such pride even today. “More than you’ll ever know,” says Ryhisky. As business there steadily declined the last 25 years the Stockyards saw its influence wane, operations shrink and grounds deteriorate. Now, with the City of Omaha practically running the Stockyards out of town and erasing any remnant of the past (although, as bound by law, the city is paying the relocation costs and commissioning a historic recordation of the site), it’s no wonder survivors feel forgotten and belittled.

Doris Wellman tells a story about Johnny’s Cafe founder Frank Kawa that sums up how stockmen were once regarded and would like to be remembered. “A group of us were having dinner at Johnny’s one evening years ago and the people nest to us thought we were a little too noisy, so they complained to Mr. Kawa. He told them. ‘If you don’t like it, get up and leave. These are Stockyards people. They built this place.'”

Share this: Leo Adam Biga's Blog

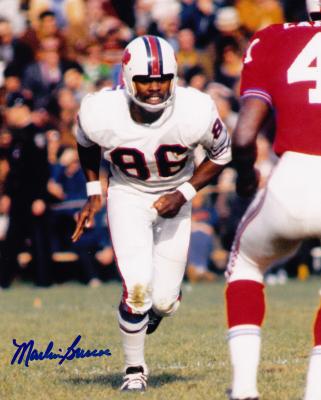

Even in those racially fraught times, Briscoe’s myth-busting feat went largely unnoticed. So did the rest of the story. After overcoming resistance from coaches and management to even get the chance to play QB, he performed well at the spot during his rookie professional season, never to be given the opportunity to play it again. That hurt. But just as he overcame obstacles his whole life, he set about winning on his own terms by learning an entirely new position—wide receiver—in the space of a month and going on to a long, accomplished pro career. He made history a second time by being part of a suit that found the NFL guilty of anti-trust violations. The resulting ruling, in favor of players, ushered in the free agency era.

Even in those racially fraught times, Briscoe’s myth-busting feat went largely unnoticed. So did the rest of the story. After overcoming resistance from coaches and management to even get the chance to play QB, he performed well at the spot during his rookie professional season, never to be given the opportunity to play it again. That hurt. But just as he overcame obstacles his whole life, he set about winning on his own terms by learning an entirely new position—wide receiver—in the space of a month and going on to a long, accomplished pro career. He made history a second time by being part of a suit that found the NFL guilty of anti-trust violations. The resulting ruling, in favor of players, ushered in the free agency era.

“Here I was on a park bench trying to get some sleep in the heart of L.A. after owning homes and property,” he says.

“Here I was on a park bench trying to get some sleep in the heart of L.A. after owning homes and property,” he says. Briscoe, Harris, Doug Williams, and Warren Moon have formed an organization called The Field General that uses the still-exclusive legacy of the black quarterback to educate and inspire young people. Blacks still comprise but a fraction of the professional QB ranks. The same is true of head coaches, coordinators, and general managers. That fact, combined with the journey each man had to make to get to those rarified places, reveals just how far the nation and league still have to go.

Briscoe, Harris, Doug Williams, and Warren Moon have formed an organization called The Field General that uses the still-exclusive legacy of the black quarterback to educate and inspire young people. Blacks still comprise but a fraction of the professional QB ranks. The same is true of head coaches, coordinators, and general managers. That fact, combined with the journey each man had to make to get to those rarified places, reveals just how far the nation and league still have to go.

A new look

A new look

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Sam Mercer, center ©Photograph by Vera Mercer

Sam Mercer, center ©Photograph by Vera Mercer