Archive

In Case You Missed It – Hot Movie Takes from July-August 2017

Hot Movie Takes – “The Crooked Way”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

If you’re a fan of great black and white photography and specifically the work of master of light John Alton, who helped establish the look of film noir, then “The Crooked Way” (1949) is a must-see. This is not a great film, but it is a good one. If only the script, direction and acting were at the same level of artistry as the lighting and cinematography, it would be remembered as a classic. But it’s well worth a watch if you’re in the mood for a solid crime, mystery, suspense story whose shadow world is gorgeous to behold in the hands of Alton. The hook behind this film is quite compelling. A mild-mannered World War II U.S. Army combat vet has suffered a head wound that’s left him with a total amnesia break The military is only able to tell him he had some connection to Los Angeles. Otherwise, he has no family or history to go on to tell him who he is and what he did in life before the war. John Payne plays the poor sap who goes to L.A, in search of answers and almost immediately two cops pick him up and take him to headquarters, where he discovers he was a notorious criminal that LAPD ran out of town and warned never to return. From there, Payne’s character begins piecing together his unsavory profile and it leads him into ever murkier, more dangerous territory, until he has both the underworld and law enforcement gunning for him. It’s all very Jason Bourne-like but the creators of this film didn’t have the imagination or instincts or good sense to show us that Payne’s character is a lethal weapon. Instead, he’s always taking his lumps and never dishing them out. Until the very end. And even then he’s a bit of a weak sister. The story needed him to be much tougher. Payne had the build and looks to pull it off, but that’s not how the filmmakers saw his character, and it hurts the piece. Bourne is a great character because he’s active, never passive, whereas this character is far too prone to take a beating rather than to dish one out.

Payne was a rather stiff, emotionally stunted actor whose limited range imposed limits on what he could bring to a part. He was always better when he played with good people and here he’s not helped much by actors playing, his rival, Sonny Tufts, and his love interest, Ellen Drew. Rhys Williams adds some life and blarney to the cop after all of them. Percy Helton added his usual eccentric presence to the proceedings.

The location for the showdown at the end offered a visual playground for Alton and director Robert Florey to work with and they made the most of it. This may be the only film of Florey’s I’ve seen and from what I read he was a second-feature director working in crime and horror genres and later a prolific TV director. Some of his B films are held in high regard and so I have to assume he was responsible for some of the arresting visual flourishes here as well as for the very good pace the film maintains. It would have been interesting to see what he could do with a better script and cast. I already know he made the most of Alton’s talents and the visual palette of this film is still the primary reason to see it, though you won’t feel shortchanged in the entertainment department either.

“The Crooked Way” is available in full and for free on YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QA08f63E4RU

Hot Movie Takes – Jerry Lewis, RIP

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Few popular entertainers have been as polarizing in their own lifetime as comic, filmmaker and humanitarian Jerry Lewis managed to be. In the years immediately after World War II he became one-half of perhaps the biggest live entertainment act in show biz history – Martin and Lewis. He played the silly clown that entertainers like Tim Conway, Robin Williams, Jim Carrey and Adam Sandler would take up after him. Martin and Lewis also teamed up for a large number of hit feature films. After Lewis and Martin split to pursue very successful solo careers, Lewis headlined some films but soon got the itch to creatively control his own starring vehicles, and so he made himself a do-everything comedy writer, director, actor in the tradition of Chaplin and Keaton. He was a very talented man but he wasn’t in their league. Mel Brooks and Woody Allen would follow Lewis. While Brooks’ best films were about on par with those of Lewis, Allen proved to be a far superior filmmaker than them. Lewis did enjoy a solid decade or so of success with the comedy films he made, even developing a hard to explain critical and popular following in France, where he was revered as an auteur and genius of comic cinema. Go figure. My personal take on this is that Lewis was unafraid to play the fool who was often a weak failure and the French liked that he punctured the American facade of superiority, strength and success. Lewis was an innovator in film production by becoming one of the first if not the first directors to use video playback technology on the set. Some of his comic bits were quite inspired. He was also capable of moving us with empathy, bordering on pity. Too often, however, his material was awkward, tone deaf, even amateurish. When he was on, his silliness worked, but when he was off, his work read just plain stupid, and that’s a kiss of death.

His films began to fall increasingly out of favor with audiences and out of touch with the times. For a long time he became better known as the Muscular Dystrophy Telethon host than for his screen and stage work. But, like the survivor he was, he then reinvented himself as a fine dramatic actor in film and television. If you’ve never seen Martin Scorsese’s “The King of Comedy” starring Robert De Niro, make a point to, because its a great dark comedy in which De Niro’s never been better and Lewis gives a superb straight dramatic performance that nearly steals the picture out from under De Niro. Lewis also received raves for his work in TV’s “Wiseguy” and in some later features. As the telethon turned into an ever harder to watch spectacle and his political incorrectness made him a fringe figure, a never completed Holocaust feature he made in Europe and tried to suppress – “The Day the Clown Cried” – came to light. When snippets from the never released picture began leaking on the Web, this bold, some say misguided attempt to stretch himself became an object of great speculation and scrutiny. What little there is to see is quite provocative. I believe Lewis made a stipulation in his will that the film not be shown publicly until years after his death.

Here’s a link to my Hot Movie Take on “King of Comedy”:

https://leoadambiga.com/…/king-of-comedy-a-dark-reflection-of-our-times/

Hot Movie Takes – “The Seven-Ups”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Philip D’Antoni produced two of the best police-crime pictures of their era in “Bullit” and “The French Connection” and, depending on how you look at it, he paid homage to or ripped off those earlier films by producing and directing “The Seven-Ups.” I always avoided seeing “The Seven-Ups” because I remember reading that it was a pale imitation of “The French Connection” but now that I’ve seen it for myself I have to report that while it owes a huge amount to that great film and to “Bullit” it is a very strong work in its own right. “The Seven-Ups” may not be quite as good as those two, but it’s well worth your time. This is the only feature film D’Antoni directed and he proved more than adequate to the task. Indeed, working with some of the very creatives and consultants behind “French Connection,” including editor Gerald B. Greenberg, technical advisor Sonny Grasso, composer Don Ellis , star Roy Scheider and co-star Tony Lo Bianco, he captures the same gritty reality and intense energy that William Friedken so indelibly committed to the screen. Scheider’s detective character of Buddy is based on Grasso’s own exploits just as they were in “French Connection.” Here, Scheider is basically playing the same character of Buddy, only this time leading a secret New York City mob investigative unit that goes by the name “The Seven-Ups” and uses extra-legal methods to make its cases. Unlike “French Connection,” Buddy and his colleagues are strictly working a domestic angle in “The Seven-Ups” that has them breaking up protection rackets. Buddy’s chief informant Vito (Tony Lo Bianco), a wise guy connected pal from the neighborhood they grew up in, turns out to be playing Buddy and the mob in a dangerous business of kidnappings for cash. When one score goes awry and one of Buddy’s men is killed, the film turns from investigation to revenge story.

The portrayals of the cops and mobsters are very believable and it’s clear each side uses unsavory tactics to get what they want. In this way, it’s very much a shades of gray story the way “Bullit” and “french Connection” are. D’Antoni makes great use of actual New York locations and stages an outstanding car chase midway through and an excellent manhunt climax .Scheider is superb as the grizzled detective who will practically go to any means in order to make a case or to get even. Scheider has that world-weary, existential thing about him that makes him a good fit for this kind of material. This was perhaps his first starring role and he makes the most of it. He’s just about as impressive as Gene Hackman was as Popeye Doyle in “French Connection.” The actors portraying his fellow investigators aren’t given much to work with in terms of dialogue but they also didn’t bring much to their parts except for a sense of working stiff commitment, solidarity and camaraderie.

The whole film rests on the uneasy relationship between old friends on opposite sides of the law and the eventual betrayal and rupture that occurs. Scheider and Lo Bianco are electric together. Less effective is the inside look at the mob. It’s not bad, but just not up to the deep, convincing takes you find in the films of Coppola or Scorsese, for example. But that’s a minor quibble since this story is mainly told from the police POV and it gets that insular world down pat. The bad guys we do spend the most time with are mob associates and rogues looking to get over The Man and they are the rank opportunists they appear to be.

Hot Movie Takes – 1967: A Memorable Year in Movies

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Some of my recent Hot Movie Takes have focused on films celebrating 50 year anniversaries this year. In reviewing what I wrote, it occurred to me that an unusual number of very good English-language films were originally released in 1967. More than I previously thought. My previous posts about films from that banner year covered “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” “In the Heat of the Night,” “Bonnie and Clyde,” “Point Blank” and “The Graduate,” respectively. In doing some online checking, I found several more notable films from ’67, including some I hold in very high regard, Thus, I feel compelled to write about some of them, too. In this new post I reflect on this overlooked year in movies and give some capsule analyses about the pictures I’ve seen and feel most strongly about. I may eventually develop separate posts on ’67 movies of special merit or with special meaning to me.

Let me start by listing the movies I consider to be the best from that year of those I’ve seen. In descending order, my ’67 picks are:

Will Penny

Bonnie and Clyde

In Cold Blood

The Producers

The Graduate

In the Heat of the Night

Cool Hand Luke

Reflections in a Golden Eye

Point Blank

The Fearless Vampire Killers

Who’s that Knocking at My Door?

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner

El Dorado

You Only Live Twice

The Dirty Dozen

To Sir, with Love

Barefoot in the Park

The War Wagon

Tobruk

Beach Red

Wait Until Dark

Throughly Modern Millie

That list includes a crazy range of cinema representing the crossroads the medium found itself at in that bridge year between Old and New Hollywood. A couple venerable but still vibrant filmmakers contributed to the year’s output: John Huston with his then-unappreciated and misunderstood “Reflections in a Golden Eye” and Howard Hawks with the middle film, “El Dorado,” of his Western trilogy that began with “Rio Bravo” and ended with “Rio Lobo.”

Richard Brooks, who rose to prominence as a screenwriter before becoming a highly successful writer-director, had the best movie of his career released in ’67, “In Cold Blood,” which is still as riveting, disturbing and urgent today as it was a half century ago. It captures the essence of the masterful; Truman Capote book it’s adapted from. The semi-documentary feel and the atmospheric black and white look are incredibly evocative. Though neither was exactly a newcomer, Robert Blake and Scott Wilson were strokes of genius casting decisions and they thoroughly, indelibly own their parts. I believe “In Cold Blood” features one of the best opening credit sequences in movie history. Even though the film doesn’t actually show overt violence, the intimate, voyeuristic way the Clutter killings are handled actually make the horror of what happened even more disturbing. Those scenes took what Hitchcock did in “Psycho” and pushed them further and really set the stage for what followed in the crime and horror genres.

Distinguished producer turned director Stanley Kramer chose that year to give us the most pregnant message picture of his career – “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.” Burt Kennedy, who owns a special place in movie history for his writing and producing that great string of Westerns directed by Budd Boetticher starring Randolph Scott, gave us an entertaining as hell if less than classic Western he wrote and directed – “The War Wagon” – starring John Wayne and Kirk Douglas.

More random cinema stirrings from that list:

Warren Beatty asserted himself a Player with the success of “Bonnie and Clyde,” which he produced and starred in. Its director, Arthur Penn, had made a splash with his second feature, “The Miracle Worker,” only to recede into the shadows until “Bonnie and Clyde” made gave him instant cachet again. The film also helped make Faye Dunaway a star. And it was the launching pad for its writing team, Robert Benton and David Newman, to become in-demand talents, both together and individually. Finally. that film, along with “The Wild Bunch,” took American cinema violence to a new place and stylistically introduced European New Wave elements into the mainstream.

“The Graduate” similarly ignited the New Hollywood with its inventive visual style, contemporary soundtrack and cool irony. Beneath that cool exterior are red hot emotions that finally burst forth in the latter part of the picture.

“Will Penny,” the film I have as the best from that decade among the pictures I’ve seen, may not be familiar to many of you. It should be. The Tom Gries written and directed Western contains the best performance of Charlton Heston’s career. The stiff, arrogant, larger-than-life weightiness that made him a star but that also trapped him is no where to be seen here. He is the very epitome of the low-key laconic cowhand he’s asked to play and he’s absolutely brilliant in the minimalistic realism he brings to the role. The supporting players are really good, too, including a great performance by Joan Hackett as the love interest, strong interpretations by Lee Majors and Anthony Zerbe as his riding companions, and superb character turns by Clifton James, G.D. Spradlin, Ben Johnson and William Schallert. The villains are well played by Donald Pleasance as the evening angel patriarch of a mercenary family and Bruce Dern as one of his evil sons. Schallert, as a prairie outpost doc, beautifully delivers one of my favorite lines in movie history when put upon by Will (Heston) and Blue (Majors) to fix their ailing companion Dutchy (Zerbe) and, smelling their rankness and shaking his head at their daftness, sends Will and Blue away so he can get to work with: “Children, dangerous children.”

The story of “Will Penny” is exquisitely modulated and even if the climax is a little frenetic and over the top, it absolutely works for the drama and then the story ends on its more characteristic underplayed realism. The satire of the piece is really rather stunning, especially for a Western. This was an era of American filmmaking when certain genre films, especially Westerns and film noirs, were generally not deemed worthy material for Oscar nominations. If “Will Penny” came out years later or even today it would be hailed as a great film and be showered with awards the way Clint Eastwood’s “Unforgiven” was (“Will Penny’s” better in my book).

The crime story that is the backdrop of “In the Heat of the Night” is pretty pedestrian and mundane but what makes the picture sing is the core dramatic conflict between black Northern cop Virgil Tibbs and white Southern cop Bill Gillespie in the angst of 1960s Mississippi. That’s where this film really lives and gets its cultural significance. Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger are crazy good working off each other.

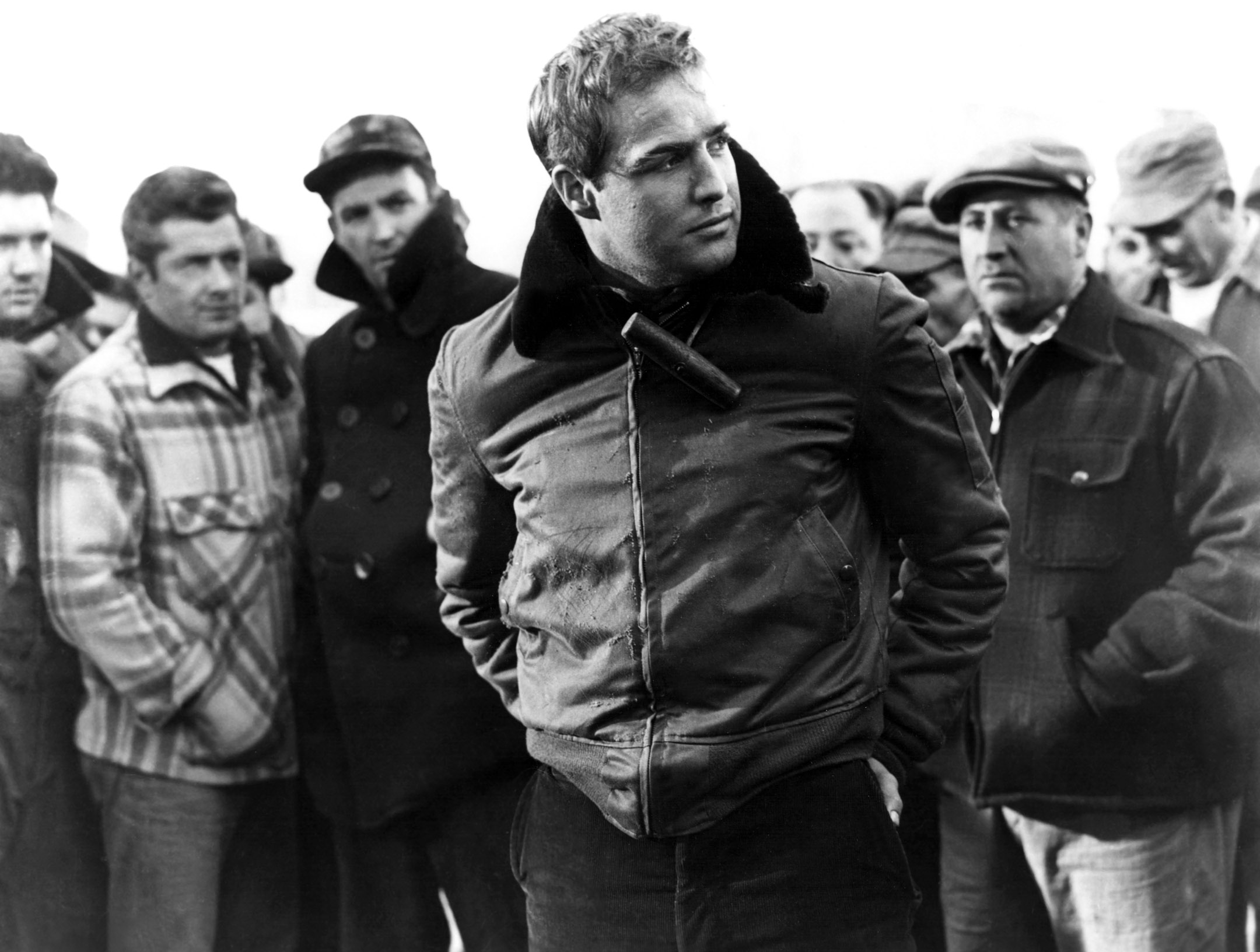

“Cool Hand Luke” was the latest vehicle for the series of rebel figures Paul Newman played that made him a star (“Somebody Up There Likes Me,” “The Long Hot Summer,” “Hud,” “The Hustler,” “Harper”) and he took this one to the hilt. It’s not really a great movie, though it’s very engaging, but Newman is a treat to watch as he repeatedly tests authority. The film includes an amazing number of then obscure but soon to be well-known character actors.

For my tastes, “The Producers” is the best comedy ever made. It is an inspired work of looniness that decades later transferred into a successful Broadway musical. No offense to Nathan Lane, but he’s no Zero Mostel in the role of Max Bialystock. Everything hinges on Max, the brash, boorish, desperate, impossible has-been of a producer reduced to seducing wealthy old women to get some of their cash to live on. When he hires nebbish accountant Leo Bloom to examine his books and hears Leo muse to himself that a play could make more as a failure than as a success by raising, in advance, far more money than the play will ever cost to put on, Max instantly seizes on the wild-hair idea as a scheme to get rich. After terrorizing and seducing sweet, dissatisfied Leo to participate in this larceny, the two embark on a grand guignol adventure to find and mount the worst play they can find. They’re sure they’ve found it in “Springtime for Hitler,” a demented musical homage to the fuhrer penned by a certifiable lunatic who believes what he’s written is a serious work of art. Not taking any chances, Max hires a raving drag queen director and encourages him to go over the top with Busby Berkeley numbers and a dim-witted lead playing Hitler as a drug-crazed hippy. Despite their best efforts and complete confidence the play will open and close in one night to disastrous reviews and the audience walking out in disgust, Max and Leo discover to their despair that they have a hit on their hands. “Where did we go right”” a desolate Max asks rhetorically. Mel Brooks wrote a greet screenplay and perfectly cast Mostel and Wilder as the fraudsters. They were never better on screen than here. We care about them, too, because the heart of the comedy is a love story between these two men, who are opposites in every way except in their mutual affection for each other. You might say each completes the other.

Kenneth Mars and Dick Shawn deliver truly inspired performances as the stark raving mad playwright and as the flower child Hitler, respectively.

That same year, 1967, introduced the world to a future cinema giant in Martin Scorsese. His little seen debut feature “Who’s that Knocking at My Door?” – starring a very young Harvey Keitel – contains themes that we have come to identify with the filmmaker’s work. Sure, it’s raw, but it’s easy to see the characteristic visual and sound flourishes, urban settings and dark-spiritual obsessions that would infuse his “Mean Streets,” “Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull,” “King of Comedy” and “Goodfellas.”

It was also the year that Roman Polanski released his first American film, “The Fearless Vampire Killers,” a sumptuous feast for the eyes send-up of the vampire genre.

I know “The Dirty Dozen” is a popular flick with an eclectic and even iconic cast in a wartime adventure that’s pure entertainment hokum but I find it too much of it canned and over-produced. Lee Marvin holds the whole thing together but outside of his performance and some routine training and combat scenes, there’s not a whole lot there. It pales in comparison to other anti-war films of that era, such as “Paths of Glory,” “Dr. Strangelove” and “MASH.”

“Barefoot in the Park” is a contrived but endearing romantic comedy that showcases Robert Redford and Jane Fonda in two of their more liable if less than taxing parts. They’re both good light comedians when they want to be and early in their careers there was little to suggest in their screen work they would be fine dramatic actors as well. Charles Boyer and Mildred Natwick basically steal the show with their overripe but delicious performances as the parallel older couple to the young couple engaged in navigating the hazards of love.

The conceits of “Wait Until Dark” were barely acceptable when I was a kid, but not so much anymore We’re asked to believe that a blind woman, Susy, (Audrey Hepburn) alone in her apartment can summon the courage and presence of ming to ward off a gang of thieves, one of whom is a cold-blooded killer. The henchmen, played by Alan Arkin, Richard Crenna and Jack Weston, concoct elaborate games of deception to try and get what they want, which is a drug stash she unknowingly possesses. The whole con setup is way too implausible as is the way Susy prevails against all odds. I mean, it’s one of those movies where we know the protagonist is going to survive but we’re asked to put aside our intelligence and common sense. I don’t what the picture looks like on a big screen, as I’ve only seen it on television, but on the small screen at least it badly suffers from the apartment supposedly being in total blackness, and thus blinding the last bad guy, when Susy’s clearly visible.

Here are several more films of note from ’67. It’s also quite a hodgepodge. I’ve seen portions of many of them but not enough of any one film to comment on it.

Bedazzled

Two for the Road

Hombre

How I Won the War

The President’s Analyst

The Night of the Generals

Accident

Far from the Madding Crowd

The Way West

In Like Flint

Casino Royale

Camelot

Valley of the Dolls

Hour of the Gun

The Taming of the Shrew

Five Million Years to Earth

Poor Cow

A Guide for the Married Man

How to Succeed in Business Wothout Really Trying

The Trip

Hells Angels on Wheels

The Honey Pot

The Happiest Millionaire

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre

Rough Night in Jericho

Tony Rome

The Flim-Flam Man

Countdown

Up the Down Staircase

The Whisperers

A Matter of Innocence

The Incident

The Comedians

Woman Times Seven

Marat/Sade

Divorce American Style

Hot Movie Takes – “Bonnie and Clyde”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Fifty years have not aged “Bonnie and Clyde” in the least. This seminal American film from 1967 plays just as fresh and vital today as it did half a century ago. In their script David Newman and Robert Benton treated the story of the Depression-era bank robbing couple of the title in such a way as to make their criminal escapades resonant with the social-cultural rebellion of the Sixties. Director Arthur Penn, in turn, found just the right approach – visually, rhythmically and musically speaking – to make Bonnie Parker, Clyde Barrow and their gang romantic, tragic and pathetic all at once. The casting is superb. Warren Beatty has never topped his performance as the enigmatic Clyde. Faye Dunaway makes what could have been a one-dimensional part complex with her multi-layered portrayal of Bonnie. Gene Hackman is a life force as Buck Barrow. Estelle Parsons almost goes too far as Blanche but keeps it together just enough to add an hysterical tone. And Michael J. Pollard brings his characteristic weirdness as CW Moss. Gene Wilder adds manic glee in a brief but memorable interlude as Eugene Grizzard. There are some great turns by nonactors, including Mabel Cavitt as Bonnie’s mother, that add authenticity. There is a free, open, rollicking, bordering on cartoonish levity to the gangster proceedings artfully counterpointed by fatalistic grimness. The story unfolds in the Dust Bowl, Bible Belt ruins of poverty, farm foreclosures, bank runs, desperation, conservatism and fundamentalism and all that comes through in various scenes and sets. It’s also the story of two star-crossed lovers who can never quite consummate their attraction for each other, perhaps because they negate rather than fulfill each other.

More than most films, “Bonnie and Clyde” captures the parallel strains of American naivety, idealism and dream-making alongside its penchant for venality, corruption and violence.

Penn made some very good films, but this was his best, with the possible exception of “Night Moves.” I believe “Bonnie and Clyde” works so well because the script is so good at describing a very specific world and Penn and Co. are so good at realizing that on screen. It’s said the Robert Towne also contributed to the script. Like with any great film, you can feel the all-out commitment its makers had in capturing something truly original. Yes, the film is in a very long line of gangster pics, but rarely before or after has one so effectively balanced comedy and drama, myth and history, romanticism and reality. Editor Dede Allen’s work in creating the frenetic yet highly controlled pace of the film is outstanding. Burnett Guffey’s cinematography is a splendid blend of Hollywood gloss meet documentary meets French New Wave. The different tones of the film made old-line Warner Brothers studio execs nervous because they didn’t know what to make of it or do with it. Some veteran critics didn’t get it upon their first look. Most notably, New York Times critic Bosley Crowther, was practically shamed into giving the film a second watch when his initial negative review was so out of step with the critical mainstream who saw it as a bold, exciting and entertaining take on an old Hollywood genre.

Sure, the film may seem somewhat tepid or tame in the wake of Quentin Tarantino’s and Christopher Nolan’s darkly comic visions of gangster worlds. But there had to a “Bonnie and Clyde” before there could be a “Reservoir Dogs” or “Pulp Fiction” and a “Memento” or “The Dark Night.”

“Bonnie and Clyde” is credited with jumpstarting the American New Wave or New Hollywood that we associate with the late ’60s through the late ’70s. If that’s true, then several other films from around that same decade, some of them made years before “Bonnie and Clyde,” also greatly contributed to that movement, including:

Splendor in the Grass

The Manchurian Candidate

Wild River

David and Lisa

Nothing But a Man

A Thousand Clowns

Lilith

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

The Graduate

Point Blank

In the Heat of the Night

The Producers

Bullit

The Wild Bunch

East Rider

Midnight Cowboy

Take the Money and Run

Catch-22

MASH

Five Easy Pieces

The Landlord

Harold and Maude

Dirty Harry

Beatty produced “Bonnie and Clyde” and it was THE project that made him a real Player in Hollywood. He’s gone on to act in and produce and direct some very good films but I’m not sure he’s ever done anything that worked so well as this. He did make one other great film as an actor in Robert Altman’s “McCabe and Mrs. Miller.” I am a big fan of two films Beatty acted in, wrote and directed: “Heaven Can Wait” and “Reds,” which are rather safe and conventional compared to “Bonnie and Clyde” but no less entertaining. But for my tastes anyway Beatty’s never made a better film than the very first one he appeared in: “Splendor in the Grass.” On that project he had the very good fortune to work with a master at the peak of his powers in director Elia Kazan and to inherit a great script by William Inge. Beatty learned from the outset how important it is to align himself with the best talent and aside from a few notable exceptions, he did that during the ’60s and ’70s.

Hot Movie Takes – “Diplomatic Courier”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

The Cold War became a topic of many 1950s and 1960s Hollywood films and one of the early ones to deal with the subject was 1952’s “Diplomatic Courier” directed by Henry Hathaway from a script by Casey Robinson and Liam O’Brien. The screenplay was an adaptation of a novel by Peter Cheyney. Pretty much any Hathaway film is a safe bet for being engaging, solidly produced entertainment and this picture is no different. But he was a director of limitations and here working with a script that’s good but not great, the result is an espionage tale that just isn’t smart enough to be anything more than a slightly better than average routine thriller. The best things about it are its lead players Tyrone Power as the title character, Patricia Neal as a mysterious American woman he gets entangled with and Hildegard Knef as the Romanian woman of intrigue who throws his world in disarray. Then there is the excellent use of actual Eastern European locations and visceral exterior and interior photography by Lucien Ballard. The story also gets great mileage out of its premise that a U.S. State Department courier with no special training or ability gets caught up in dangerous, deadly spy games that become very personal for him.

Power makes a believable and sympathetic ordinary man thrust into extraordinary circumstances figure when his old U.S. Navy veteran pal doesn’t hand off the diplomatic pouch as expected behind the Iron Curtain. A complicated sequence on a train and in train stations ensues that ensnares Power deep into a brewing international incident. I kept thinking that Power would have made a very good leading man in a Hitchcock film. I am very impressed by Knef, whom I’d never heard of before. She practically steals the picture out from everyone else with her portrayal of a refugee playing different sides against each other. Neal never looked more beautiful than she does in this pic and her ability to play both hard and soft comes in handily here as a widow who is and is not what she appears to be. Stephen McNally gives his typical no-nonsense, hard as nails performance as a U.S. Army officer who enlists Power for more hazard duty. Karl Malden brings some color to his part as a good-old-boy sergeant who keeps coming to Power’s rescue. As a by-the book and eager-beaver M.P. Lee Marvin, in one of his first speaking parts, gets to banter a few words with Power. Despite only being on screen for a minute. the dynamic Marvin makes his presence felt. Michael Ansara is appropriately dour and menacing as a Soviet bad guy. And Charles Bronson looks aptly Slavic and tough as another Soviet goon, though he doesn’t get to speak any lines.

On the down side, there are some gaping logic and credibility holes, the clumsily.staged action scenes land flat and the stock Soviet agents lack the verve of three dimensional characters. I mean, one part of me knew that Power would somehow negotiate the duplicity and survive the ordeal, but another part of me would have liked for things to get a bit more harrier than they do, though by the end the stakes are for keeps. But the whole thing is played a bit too much by the numbers safe and antiseptic where it could have used more down and dirty grit. On the whole though, it’s probably a better movie than it needed to be in terms of sheer production value and performance. Not quite a classic, but a worthy addition to anyone’s curated spy and mystery cinema collection.

“Diplomatic Courier” is available for free and in full on YouTube.

https://www.movie–trailer.co.uk/trailers/1952/diplomatic-courier

Hot Movie Takes – “Nightmare Alley”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Ever encounter a movie you heard about your whole life that you build up certain expectations around only to finally see it and have it leave you wanting? Well, that’s my experience with “Nightmare Alley,” a 1947 drama starring Tyrone Power, Joan Blondell, Colleen Gray, Helen Walker, Taylor Holmes, Mike Mazurki and Ian Keith. The hothouse script is by Jules Furthman (from a William Lindsay Gresham novel) and the taut direction is by Edmund Goulding. The brooding photography is by Lee Garmes. I think the film suffers a bit from false advertising because today it’s billed as a film noir and I just don’t see it neatly fitting that genre. I consider it more akin to the Todd Browning horror show “Freaks” than any of the classic noirs from that period, with the possible exception of Edgar Ullmer’s “Detour.” Sure, “Nightmare Alley” reeks with darkness – from its theme to its look – but that alone does not make a noir. Its plot of a man reaching too far and then suffering a terrible fall is more a classical narrative than a noir narrative. Tyrone Power plays the ill-fated protagonist – an overambitious carny willing to do anything to get ahead. Many consider this to be Power’s best film performance. He is quite good in it. He fought hard for the movie to be made and for him to go against type and I admire him for it.

Indeed, I feel Power was a very underrated actor. I think his extreme good looks worked against him in terms of the kinds of parts he was forced to settle for in the old studio system. While he didn’t have the talent of another incredibly handsome actor, Montgomery Clift, he did have a grit and depth, besides his considerable charm and charismam that often times wasn’t acknowledged. The part in “Nightmare Alley” demanded a lot and he was up to it. I think he could have had the same kind of postwar career another pretty boy, William Holden, enjoyed had he been given the same caliber parts. Whenever Power did get a superior script and director, he rose to the occasion, as in “Witness for the Prosecution” for Billy Wilder, “Rawhide” for Henry Hathaway and “The Long Gray Line” for John Ford.

“Nightmare Alley” is in the spirit of the pre-Code exploitation movies that depicted the depravity of desperate in zealous pursuit of money, power, fame. Its harsh, unsparing stuff. Joan Blondell is just okay as the spiritualist but the movie would have been much better with a stronger actress in the part. Barbara Stanwyck would have been perfect. Blondell’s character and her alcoholic husband, in a superb performance by Ian Keith, have a low rent act together in a small-time carnival. The couple used to be headliners in vaudeville and in posh clubs. They devised a code that became the key to their act but ever since the bottle brought him down they’ve been reduced to traveling side show performers. In the carnival, Power is a part of the act, and behind Keith’s back he and Blondell carry on an affair and eventually scheme to leave him behind and reconstitute the act using the code. When Keith dies by accidentally drinking poison he thought was liquor, Power is taught the code by Blondell and by a young performed played by Colleen Gray who adores him. Power isn’t above playing the field with her and when the two are forced to marry he convinces her they should leave the carnival and strike out on their own. The pair soon make it big with their mentalist act. But Power isn’t satisfied and his relentless coveting after more gets him mixed up with a hustler even more cunning and dangerous than him. He crosses many ethical. moral lines to get what he wants. His inevitable and even foretold epic fall is eerily parallel to what happened to Keith and other former headliners who suffered similar fates. There’s a moralistic salve at the end that lessens the impact but it’s still a powerful conclusion to a nightmarish tale.

I have to think this movie would have been a classic in the hands of Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder or Orson Wells, whose baroque visual styles and cynical tones would have been tailor made for the material. Edmund Goulding was a journeyman pro who lacked their dark visions and sensibilities. I got the impression he tried to sanitize the film and raise it from its B origins when in fact he should have reveled in its perversity and celebrated its exploitation roots. That may have been a studio-imposed thing, too.

https://http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1144535_nightmare_alley

Hot Movie Takes – “The Longshot”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

I admit it, I something of a film snob, but the other night I put away my elitism long enough to watch a quirky, sometimes hilarious, even inventive, but more often just plain silly and ultimately too dumb 1986 Tim Conway scripted and starring comedy vehicle called “The Longshot.” It’s an odd little number for several reasons, not the least of which is that it was directed by Paul Bartel of “Eating Raoul” fame and executive produced by Tony and Oscar-winning director Mike Nichols. Conway is the ringleader of a dimwitted group of friends hopelessly addicted to playing the ponies and hoping they will finally score big even though they always find ways to lose, even when they have a sure thing. His loser cohorts are played by Harvey Korman, Jack Weston and Ted Wass. Each character is actually more fully developed than you would expect from a B film like this and that is one of its saving graces. These are good actors given a chance to play with some rich comic parts and they have a field day with it. There are some nice character turns by actors playing the various archetypes found at any race track – in this case Hollywood Race track.

The boys believe they’ve stumbled onto an inside fix that will make them big winners. They need to play large in order to bet large but they are good as broke. So in typical nitwit fashion they borrow money from the mob. Along the way Conway’s character barely escapes becoming a gelding at the hands of a deranged woman played by Stella Stevens. When the sure thing at the track ends up being a ruse, it looks like curtains for our four stooges until Conway remembers what their horse’s former trainer told him about getting the nag to run like the wind.

Much of the film plays like a Jerry Lewis comedy, which is to say that when it’s works it’s surprisingly good but when it falters it really stinks and in between it’s just okay. The first third of “The Longshot” is quite strong and had me thinking it just might be a worthy companion piece to one of my all-time comedy favorites, “Let It Ride,” which is about a horse player, but “The Longshot” is unable to sustain things. Like most films that show some real promise and then let you down, this one settles for things that in better hands would never be acceptable and, when all is said and done, it’s just not smart enough. Yes, even a film about four dummies needs to be really smart in order for the gags to come off (witness the Farrelly brothers comedies).

On the positive side, Conway, Korman, Weston and Wass work very well off each other and each has some shining individual moments. Some of the physical comedy bits are pretty inspired. And there are some very good lines and scenes, though not nearly enough. Conway and Bartel also tend to let many comic bits go on too long and to beat some tired old gags to death.

https://www.videodetective.com/movies/the-longshot/2007

Hot Movie Takes – “The Mountain Road”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Daniel Mann’s feature film directorial career got off to rousing start in the 1950s with “Come Back, Little Sheba,” “About Mrs. Leslie,” “The Rose Tattoo,” “I’ll Cry Tomorrow,” “Hot Spell,” “The Last Angry Man” and “Butterfield 8,” all prestige pictures based on plays or novels. Mann knew his way around a drama and there are some fine things that stand the test of time in those films, though they all pale against the best films of that or any era.

One of his lesser known efforts, “The Mountain Road” (1960), may be his most enduring big screen work. Mann very ably directed an Alfred Hayes script based on a Theodore White novel to create a mature, unvarnished look at racism and cultural dissonance in the American military campaign aiding China’s resistance of invading Japanese forces in World War II. This movie has much in common with John Ford’s “The Searchers” in that they both deal head-on with a racist protagonist hell-bent on revenge against indigenous peoples. In the Ford film, it’s John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards who hates Native Americans and will stop at nothing, even killing his own niece, to exact his brand of justice. Like all racists, Edwards dehumanizes the Native to justify his attitudes and actions. He’s a returning Civil War veteran who lost his way and his connection to civilized society in the years after the war. When Indians attack and kill family members, kidnapping his niece, he sets out on an epic, blood-thirsty manhunt. In “The Mountain Road’ James Stewart’s Major Baldwin is a civilian engineer turned Army demolition officer assigned to blow up an airfield and bridge in the face of advancing Japanese troops. Baldwin is a good man but he can’t hide his antipathy for the Chinese. All the men in his unit harbor the same ill feelings, with the notable exception of Collins (Glenn Corbett), who admires Chinese culture and tries hard respecting Chinese ways.

In addition to Corbett, there are some very fine supporting performances by actors playing the other men comprising the demo team: Harry Morgan, Rudy Bond, Mike Kellin, James Best, Eddie Firestone, Alan Baxter. Frank Silvera plays a Chinese colonel attached to the unit.

Baldwin commits his men to extra duty when he agrees to have them block a key mountain pass and to blow a major ammunition dump. The small convoy is repeatedly delayed by the refugee-choked roads. The assignment develops a further complication when the outfit is obliged to transport an indigenous woman whose Chinese officer husband was executed by the Japanese. Lisa Lu plays the educated, high principled Madame Su-Mei Hung who acts as a buffer between the Americans and the Chinese. En route to where the Americans are taking her, Baldwin and Hung develop romantic feelings for each other. But even their warm regard cannot survive the enmity he exhibits when one of his men is trampled to death by starving refugees and the rage he goes into when two more of his men are killed and their bodies desecrated by irregular Chinese soldiers. Baldwin systematically, brutally seeks retribution against the renegades and leads his men in committing a war crime to exact payback. Madame Su-Mei Hung is horrified by their actions but is particularly sickened that he would not only condone but actively participate in such behavior.

Dealing so frankly with American G.I. xenophobia and atrocity in a Hollywood film was pretty much unheard of at the time. I mean, this goes far beyond “South Pacific” and “Sayonara” and is closer to “Bad Day at Black Rock” in terms of its malevolent tone and social critique.

https://http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/mountain_road

Hot Movie Takes – “Jackie Brown”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Quentin Tarantino dug Hollywood exploitation movies of the 1970s and ’80s and he cast two veteran actors from those movies, Pam Grier and Robert Forster, to play the leads in his superb “Jackie Brown” (1997). The film’s a faithful adaptation of the Elmore Leonard Novel “Run Punch.” This is my personal favorite among the Tarantino movies I’ve seen (the others being “Reservoir Dogs,” “Pulp Fiction,” “Kill Bill,” “Inglorious Basterds”) because it has the clearest exposition lines and the tightest control over his often florid verbal and visual language. Tarantino knew he wanted Grier for the role and so he changed the character from a Caucasian in the book to African-American and changed her name, too, I knew something of Grier before the film but I’d never seen any of her movies in their entirety and so her performance as the title character was a revelation to me. She brings total conviction and believability to playing a strong, street-smart, together woman trying to get by the best way she knows how as a stewardess for a crap airline. But the job doesn’t pay squat and so she has a little action going on the side – running illegal arms money from L.A. to Mexico and back for Ordell Robbie (Samuel L. Jackson). Jackie knows the risks and how the system works and so when she’s caught she begins working the system against itself and against her criminal employer.

Forster is equally convincing as bail bondsman Max Cherry, a real pro at what he does but at a point in life where he’s looking for an opportunity to get make a chance. Max is street wise, too, and he knows that in Jackie Brown he’s met someone who is at least his match. He’s older than her but she appreciates his integrity and keeping it real with her, He admires her beauty, her savvy and how she carries herself and her business with a real calm in the midst of chaos. He does the same in his own way and it’s why Jackie comes to trust him with her scheme.

Perhaps the best thing Tarantino does as a writer-director is to create rich, multi-dimensional characters and then to cast the right actors in those roles so that we feel they really inhabit the worlds they traverse. His characters seem so real because they carry – through the words they speak, the situations they appear in and the behaviors they exhibit – a history and context that is palpable, even if not seen. It’s right there in the dialogue and the actions, the gestures and the expressions, the body language and the settings.

Jackson has never been better as the charismatic gun runner Ordell, who stands in the way of Jackie and Max steering his stash, which is exactly what they conspire to do. Early on, we see how Ordell is ruthless in protecting his interests when he kills an associate he only thinks may inform on him. Later, when he suspects Jackie is turning state’s evidence against him, he plots eliminating her, too, but he finds she is not so easily intimidated or disposed of. Robert De Niro is wonderfully low key as fresh out of prison life criminal Louis Gara, an old associate of Ordell’s, Gara is more than a little lost in the outside world and becomes the next loose cannon threatening to bring down Ordell’s world. Bridget Fonda is very good as the irritating Melanie, a white surfer girl Ordell keeps as a front for his illicit activities. And Michael Keaton shines as overly eager federal agent Ray Nicolette.

While the film has all the treachery and duplicity we’ve come to expect from a Tarantino flick,, there’s a subtle romance story at the heart of this one that separates it from all the rest. Grier and Forster generate real sparks together even though they only fertilely act on the mutual attraction that binds them.

As a film, the whole works runs like a finely-tuned mechanism, without a false start or note or measure. The two-hours go by in a flash. Tarantino’s penchant for bending time and revisiting moments from different perspectives can be off-putting and jarring, but not here. This technique adds layers of meaning and depth to the mosaic.

It’s a great looking and sounding film, too, with gritty cinematography by Guillermo Navarro and a pitch-perfect music soundtrack of black power soul and R&B songs that help set the mood and tell the story.

I love the fact that Jackie, a middle-aged black woman, is the mastermind heroine who uses all her wiles to beat both the law and Ordell. She’s not a femme fatale because she’s totally straight with Max from the start. He knowingly and willingly goes along with her plan and when they pull it off she clearly wants him to go away with her to enjoy the score they made as a team. The ambiguous ending leaves to our imagination if Max and Jackie will end up together. That’s only right since these two mature, independent-minded people only found each other by coincidence and then used each other to get what they wanted. Even though they have feelings for each other, this story is not about finding love – but freedom and getting out from under The Man.

“Jackie Brown” is available on Netflix.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7HkBDNZV7s

Hot Movie Takes – “Human Desire”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Part of my sick at home triple feature yesterday was the 1954 Fritz Lang film noir “Human Desire,” which I’d only seen a few minutes of before, and I must say this is a very good film. Lang makes great use of actual settings for this story of a railroad engineer who gets sucked into a whirlpool of deceit and murder that threatens to bring him down. Glenn Ford plays the engineer, a recently returned single war veteran looking to make s fresh start in his hometown. His uncomplicated life turns nightmare when he begins an affair with a manipulative married woman (Gloria Grahame) who is embroiled in a sick relationship with her abusive husband (Broderick Crawford). When the controlling Crawford character goes too far in a jealous rage, he holds this act over Grahame and it binds her to him despite their mutual loathing for each other. When she begins reeling in Ford to do her dirty work for her and eliminate her husband from the equation, he finds himself going down an ever darker path with no good end in sight.

This picture pretty much has it all in terms of film noir:

a brazen femme fatale; a fatalistic plotline; a conflicted protagonist; a brutish villain; and dream-like, expressionistic black and white photography by Burnett Guffey that captures both the harsh and romantic aspects of rail life and the sweet and confining aspects of small town America. Lang makes the trains, their whistles and schedules both a practical and symbolic part of the narrative. Ford’s character represents the wide open freedom of the rails. He’s his own man – until he’s not, For Grahame’s character, the sound of a train is a wistful reminder of how close yet distant her own freedom is from the trap she’s made of her life. And for Crawford, the harsh, hard, unbending rails are a prison of his own making.

The inspiration for this movie is the Emile Zola novel “La Bete humaine,” which Jean Renoir made into a classic film. I’m not sure the Lang version is a classic but it’s certainly a better than average noir. I think a stronger cast would have made the film better, and here I’m referring to Ford and Grahame. Neither was a great actor. They both do an adequate job here but I would have preferred, say, William Holden and Elizabeth Taylor. As the heavy, Crawford is fine, though again I would have preferred, say, Rod Steiger or Ernest Borgnine or Robert Ryan.

I also found ridiculous that the daughter of Ford’s best friend, played by Edgar Buchanan, has supposedly grown from awkward teen to mature young woman in the space of the three years Ford was gone to war. The actress playing her has got to be around 30. And she’s a real dish and it’s hard to conceive that Ford would jeopardize everything for Grahame’s neurotic and married character and ignore this real catch, who by the way adores him, under his own roof (he’s boarding with her family). I guess it’s an instance of the guy going for the bad girl over the good girl just the way some women do for guys.

The film reminds of Hitchcock’s “Shadow of a Doubt” and of the James M. Cain classic “The Postman Always Rings Twice,” but in the end it is a singular, stand-alone American cinema work.

Hot Movie Takes – “The Lineup”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Got another old crime film fix in last night watching “The Lineup” on YouTube. This 1958 Don Siegel directed and Stirling Silliphant scripted police procedural is a tale of two movies about police investigating an illicit drug smuggling ring in San Francisco. When the movie is focused on the two detectives and their colleagues trying to crack the case, it’s pretty routine, nothing special to write home about fare. But when focused on the crooks and their accomplices, it’s quite engaging for giving us two out of the ordinary villains in killer Dancer played by Eli Wallach and his Svengali-like associate, Julian. played by Robert Keith (father of Brian Keith). Dancer is a from the streets tough being groomed in the finer things by the erudite Julian. Their unusual, philosophical, literate, irreverent, sarcastic repartee is something akin to what the Samuel L. Jackson and John Travolta characters exhibit in “Pulp Fiction.” The exchanges between Dancer and Julian almost make you forget they’re cold blooded sociopaths – until their malice and menace leak through.

The violence in the movie is also harsher and more jarring than what you’re used to from the cinema of that era. There’s an extended car chase at the end that ranks among the best in screen history. The callous tone of the film was certainly influenced by the Cold War.

Siegel and cinematographer Hal Mohr make great use of Frisco locations and Siegel and Bruce Surtees would do the same years later in “Dirty Harry.” Indeed, one of the distinguishing marks of Siegel’s work was his obvious interest in and flair for shooting on location and using actual places. It’s visible in virtually all his best movies and gives them a vital realism. Siegel also knew how to cut his films for maximum pace and urgency, though the older he got the slower the rhythms he employed, and not always to the work’s advantage.

If the detectives, played by stiff Warner Anderson and ambivalent Emile Meyer, had been made half as interesting as the bad guys, this could have been a minor masterpiece. But as it is, the dull, strictly by the numbers police stuff bogs down the film and is out of balance with the far more dynamic criminal goings-on and characterizations. Even so, it’s a better than average crime picture. Better than the last Siegel film I posted about – “Private Hell 36,” which he made a few years earlier. Siegel was already a good director by the ’50s but he got better as his career went on. He would go on to make some superior genres pics starting in the late ’50s trough the late ’70s:

Edge of Eternity

Hell is for Heroes

The Killers

Coogan’s Bluff

Two Mules for Sister Sara

The Beguiled

Dirty Harry

Charley Varrick

The Shootist

Escape from Alcatraz

I consider “Hell is for Heroes,” “Dirty Harry,” “Charley Varrick” and “The Shootist” as genuine classics and I greatly admire the rest of those films as well,

A couple more of his films from this period have very good reputations, including “Madigan,” but I’ve only seen a few minutes of it and so I need to make an effort to watch the whole thing before making a call on it.

Of course, before “The Lineup,” Siegel made some very good films as well, most notably “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” and “The Big Steal.” There are a few others from that earlier period that are well thought of that I need to see, including “Riot in Cell Block 11.”

By the way, the Wallach and Keith characters are not the only charismatic villains in “The Lineup.” Richard Jaeckel is good as the getaway driver Sandy McLain and Vaughn Taylor is superb as the enigmatic The Man, Larry Warner, a Mr. Big figure who’s reference throughout the whole picture and only seen near the very end. Taylor only has a couple minutes to make an impression and he does.

“The Lineup” was inspired by a radio and TV series of the same name and theme.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qjN2gyhNSRA

Hot Movie Takes – “The Producers”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Mel Brooks has had a hand in a few comedy film classics as both writer and director, One of them, “Young Frankenstein,” he co-wrote with its star Gene Wilder. But it was Brooks and Brooks alone who wrote his very first feature, “The Producers.” It’s a farce in the same spirit of Billy Wilder’s 1960 “Some Like It Hot,” though with a very different plot. Like that earlier film, “The Producers” (1967/1968) is so damn good because the writing is truly inspired and the pitch perfect cast throw themselves into their roles with such aplomb. The central idea behind both films is cute and in lesser hands would not have been able to hold up for 90 or 100 minutes. But Brooks, whose writing can be plain bad and whose comedic can be wildly uneven, structured a very strong, cohesive script that only has a few lapses in judgment and taste in it. I believe the real strength of the piece is in the very inventive plot. Two desperate losers, Max and Leo, scheme to make a fortune by getting investors to put up far more capital than the actual budget and then doing everything possible to ensure the play is a one-night only flop, thus leaving the producers off the hook to pay back their financiers. Max and Leo endeavor to find the worst possible material and are sure they’ve done so with “Springtime for Hitler,” a staggeringly bad, offensive tribute to the fuhrer and Nazism. They take further precautions by hiring a director whose tasteless vision for the story is beyond belief. And as final insurance, they cast an actor in the lead role of Hitler who makes the evil dictator a misunderstood hippie.

Convinced their production is a dreadful abomination sure to turn off any audience and thus destined to bomb on opening night, the producers are shocked when their play is warmly received as a novelty comedy. As a devastated Max says to Leo, “Where did we go right?” Because the play’s a hit, it’s only a matter of time before the fraud the producers committed is found out and they can’t possibly satisfy all their investors. But what really makes the story sing is the humanity of Max and Leo, who are total opposites, and their love for each other. Max is loud, crude, abrasive and afraid to show his vulnerable side, whereas Leo is a meek, gentle soul afraid to risk anything outside the box. Both are lonely, unfilled men looking for a reason to live. Each finds in the other what’s missing in himself. Of course, having two actors perfect for those parts brought the characters to full, vivid life. We really care about them.

The other thing that makes “The Producers” work so well is how Brooks isn’t timid at all in tackling outlandish, sensitive, controversial subject matter. He manages to do this without being tacky and where he is tacky it works for the story. With plot-lines that include a mad playwright obsessed with celebrating Hitler, a drag queen director turning the play into a Busy Berkley-“Hair” hybrid and a producer (Max) not above seducing little old ladies out of their money, this farce plays like a dark comedy. That’s just how it is with “Some Like It Hot” with its gender-bending plot and Jack Lemmon’s character seemingly changing sexual preference by movie’s end. And just as Lemmon and Curtis were totally committed to their parts, so are Wilder and Mostel. The sheer, unadulterated, ballsy freedom of the material and its interpretation is what captured me when I first saw “The Producers” and it’s still what captures me today.

When I first heard that Brooks had adapted “The Producers” into a musical, I was taken aback, until I realized its over-the-top quality, combined with it already being about staging a musical, provided a ready-made canvas for such a treatment. I mean, Max and Leo are practically comic opera characters as originally written anyway and even watching the film now it’s not hard to imagine them bursting into song amidst such emotionally-keyed, histrionic and campy goings-on.

I’ve never seen the Broadway version or the new movie made from it, both with Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick in the parts that Zero Mostel and Gene Wilder so memorably played, and I don’t care to. The original is just too dear to me and I’m afraid I would be most unkind to any updating. For me and for a lot of other fans, the original is an untouchable cinema classic.

The Producers (1968) trailer – YouTube

Hot Movie Takes – “The Heroes of Telemark”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Kirk Douglas enjoyed a brilliant career from the late 1940s through the mid-1960s before an inexplicable drought in quality films that’s now lasted half a century. No actor in Hollywood made more good films than he did from about 1947 through about 1967. But from that point forward, it’s hard to find even a single good film he made with the possible exceptions of “Posse,” which he also directed, “The Fury” and “The Man from Snowy River.” Last night on YouTube I rewatched a film from the latter part of his quality years – the 1965 war thriller “The Heroes of Telemark” directed by Anthony Mann. It’s a good film based on true life events but it doesn’t compare with another World War Ii movie he appeared in that same year, Otto Preminger’s “In Harm’s Way.” The point is, Douglas was still a major star in important projects. No one could know it at the time but his real peak occurred at the end of the ’40s through the early ’60s, and he would never again regain relevance or stature, not even as a character actor and supporting player. It’s hard to explain.

At the peak of his powers he worked with great directors on excellent films:

William Wyler, “Detective Story”

Billy Wilder, “Ace in the Hole”

Howard Hawks, “The Big Sky”

Vincente Minnelli, “Lust for Life”

Stanley Kubrick, “Paths of Glory”

Alexander Mackedrick, “The Devil’s Disciple”

John Sturges, “Last Train from Gun Hill”

John Frankenheimer, “Seven Days in May”

And let’s not forget “Champion,” “The Bad and the Beautiful,” “Gunfight at the OK Corral,” “Lonely are the Brave” and the aforementioned “The Vikings” and “In Harm’s Way.”

Some point to Douglas’ scenery-chewing propensities for why he fell out of favor with filmmakers and audiences but this is an actor capable of great subtly too. Indeed, his best performance may be in the very understated role of a modern day cowboy in “Lonely are the Brave,” which was the favorite of his films by the way. And if overacting, very much a subjective, in-the-eye-of-the-beholder thing, is such a mortal sin, then how do you explain the sustained excellent careers of Jack Lemmon, Jack Nicholson Al Pacino, Samuel L. Jackson or even Johnny Depp?

“The Heroes of Telemark” is one of those well-mounted big physical productions in which the characters tend to get lost amidst all the outdoor locations and the action. Much of it was shot in and around the very mountainous sites in Norway where the actual events the movie depicts took place. Even with its fidelity to place, and we’re talking gorgeous snow covered slopes and cliffs turned treacherous by marauding Nazi troops, the characters become more props than human beings. That’s not the actors’ fault. It’s the fault of a script by Ben Barzman and Ivan Moffat and of the direction by Mann that leave some gaping exposition and character development holes that no amount of local color or scenery or derring-do can cover up. This is ironic, too, because Mann was a director known for staging high drama in rugged outdoor locales (see his series of Westerns with James Stewart) and expertly having the settings and the characters communicate with each other. For whatever reason, he wasn’t able to pull that off with this war movie.

Still, the film mostly works and takes you on a satisfying ride filled with suspense, adventure, heroism. It’s just that there’s something missing. It doesn’t help that Douglas and co-star Richard Harris don’t seem to have much of chemistry. I mean,I know they start as antagonists and only eventually become friends, but there’s no there-there when the pair are on screen together. The part of Kirk’s love interest and ex-wife played by Ulla Jacobsson is okay but nothing special. Her father is played by Michael Redgrave, and in many ways he delivers the most interesting performance in the film but unfortunately he’s only on screen for a few minutes.

The actors playing the various German officers are appropriately sinister.

The upload of this film online is pretty darn good but the clarity, especially in the night scenes, is somewhat muddy,

Hot Movie Takes – “The Vikings”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Richard Fleischer was a journeyman Hollywood director from the mid-1940s through the late 1980s who moved indiscriminately from one genre to another and from projects of certifiable to dubious quality. Because his work was all over the place and he wasn’t a writer per se himself, it’s hard to assign a particular style to him except to say his better films consistently showed visual flair and his stories crackled with real verve. His father was the great animator Max Fleischer and if anything the son Richard Fleischer displayed an almost graphic novel sensibility to the way his movies looked, sounded and played. That was brought home to me last night watching one of his biggest hits, “The Vikings,” a sumptuous 1958 epic starring Kirk Douglas, Tony Curtis, Ernest Borgnine, Janet Leigh, James Donald and Alexander Knox. It’s grand entertainment served up with stunning Nordic locations and rich, if stereotypical, portrayals,, of Viking life. The film demonstrates Fleischer’s ability to handle epics, and he made several of them, but this was probably his most successful alongside “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” and “Barrabas.”

Helming the Disney adaptation of the Jules Verne classic about the fictional Captain Nemo, he got a reputation as a special effects director and went on to make many films that relied on heavy effects work, such as “Fantastic Voyage,” “Doctor Doolittle,” “Tora, Tora, Tora,” “Amityville 3D” and “Conan the Destroyer.” But there was another side of Fleischer that he should have cultivated even more and that was his real gift for making taut crime thrillers. As good as “The Vikings” is and it actually holds up very well (it would make a great revival pic on the big screen), Fleischer’s best work came on pictures like “The Narrow Margin,” “Violent Saturday,””Compulsion,” “The Boston Strangler,” “The Last Run,” “10 Rillington Place,” “The New Centurions” and “Mr. Majestyk.” But he kept returning to period costume pics that were more about exploitation (“Mandigo,” “Red Sonja”) than evocation.

“The Vikings” is a happy hybrid of exploitation and history, resulting in an always gorgeous to look at spectacle that falls short of great because of a mediocre script. Cinematographer Jack Cardiff, who went on to direct his own Viking feature in “The Long Ships,” helped Fleischer create a visually beautiful film. Fleischer and his team of craftsmen worked with real ships on real fjords and with genuine castles in authentic locations to execute many of the film’s dynamic set pieces and action sequences.

The stirring score by Mario Nascimbene hits just the right notes of legendaric saga, vigor and adventure.

Ernest Borgnine and Kirk Douglas deliver full-blooded performances as a high-spirited Viking father and son duo bedeviled by a scheming English slave, played by a sullen Tony Curtis. Early in the film, Douglas and Curtis have a confrontation that results in Douglas sustaining a terrible injury. Curtis is bound to rocks off shore to drown but is saved by the Gods and claimed by an English spy (James Donald) employed by the Vikings to make maps that guide their raids on the English countryside. The spy recognizes a talisman around the slave’s neck that has great implications. It turns out the Curtis character, who was taken as a child in a Viking raid, is the heir to both Viking and English kingdoms. His blood father is the Borgnine character (who impregnated an English princess during a raid) and his blood brother is the Douglas character. Only Donald doesn’t tell him who his father is. When the Vikings kidnap an English princess (Janet Leigh) for ransom, Curtis vies for her affections with Douglas. The two men are sworn enemies and a deadly conflict to the end is ensured when Curtis escapes with Leigh. In the aftermath of the pursuit, Borgnine meets a spectacular death. The climactic fight between Curtis and Douglas lives up to the expectation.

Something’s that’s always bothered me about the film and still does after watching it again last night is that the Curtis and Leigh characters are not well developed and they both come across as cold, rather cruel individuals. They’re cardboard cutouts compared to Douglas and Borgnine, who are full of life. But, given Hollywood mores of the time, the Vikings are cast as barbarian villains who rape and pillage, and the English are cast as cultured victims. Things were a little more complex than that. I think the movie would be more satisfying if everybody got what they wanted rather than killing off the supposed bad guys. I mean, they’re way more interesting than the heroes here. And it’s not like the English characters don’t have all kinds of guilt, manipulation and blood on their hands. I guess it’s all in how you look at it.

This was one of several films that Curtis and Leigh made together when they were married.

Douglas followed this epic by producing and starring in one of the greatest epics ever made, “Spartacus,” directed by Stanley Kubrick.

By the way, until recently there were only awful uploads of “The Vikings” on YouTube, but someone has put up a superb upload of the film. Better watch it while it lasts. The same for another Douglas flick, “The Heroes of Telemark.” I’m watching it tonight.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0FF9JLIj1c

Hot Movie Takes – “Fruitvale Station”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

I saw and greatly admired writer-director Ryan Coogler’s “Creed” (2016) before I watched the film that first put him on the map, the 2013 drama “Fruitvale Station.” Now that I’ve absorbed the earlier film and found it an impressive work as well, it’s abundantly clear that Coogler’s one of the bright new American filmmakers to have arrived on the scene. He’s also part of a New Wave of African-American filmmakers making their marks (Barry Jenkins, Malik Vitthal, Dee Rees, Jordan Peele).

“Fruitvale” is a bio-pic that dramatizes the last day in the life of Oscar Grant III, who in 2009 was wrongfully killed by an Oakland rapid transit police officer. Before the shooting, Grant and his male friends were brutalized by officers. There was no cause for the officers’ actions. The young African-American men got into a brief undeventful altercation with some race baiting white supremacist gang bangers on the train New Year’s night. No one was hurt. The black men were clearly profiled by the white officers because they were the only ones detained. None of this is conjuncture, Virtually the entire encounter was captured on video by several onlookers. The cops, not the young men, were the problem here. Coogler sets up the final tragic moments of Grant’s life through an unvarnished, semi-documentary approach that portrays the 22-year-old, warts and all, as someone trying to better himself and the lives of his girlfriend and daughter. Like too many young black males from inner cities, Grant faced a lot of challenges. As the movie plays out, we learn about his criminal and incarceration history, his anger issues, his problems holding a job and the street life pressures and threats he confronts that can turn violent in an instant. We also learn he’s a sweet, silly kid with a lot of growing up to do who deeply cares for his family and is desperate to make a new start. He just doesn’t know how and society doesn’t do well by individuals like him.

Outrage over his unnecessary death at the rail system’s Fruitvale Station, among a series of officer involved wrongful death scenarios around the nation, was a flash-poins for the Black Lives Matter movement.

Coogler drew on his own experience as a young black man in America and his work counseling youth on a San Francisco correctional facility to humanize the story and keep it real. Michael B. Jordan, who went on to star in Coogler’s “Creed,” brings a very authentic balance of harshness and gentleness, street smarts and naivete to his interpretation of Grant. Melonie Diaz and Ariana Neal are believable as his girlfriend and daughter, respectively. They, along with his mother, played beautifully by Octavia Spencer, all worry about Oscar because they know that trouble follows him and that danger lurks in the streets. Sadly, ironically, his death comes not at the hands of a gang banger or a stereotypical bad guy, but at the hands of rouge cops overreacting to a situation and doing the exact opposite of what they’re called to do: protect and serve.

Coogler favors an intimacy and immediacy to the way his films look and feel, and he was well served in this regard on “Fruitvale” by cinematographer Rachel Morrison. When Coogler and Morrison do go wide or long or slow, it has a greater effect than it would otherwise because of the intimacy and fluidity of what precedes and follows it. Coogler and cinematographer Maryse Alberti found the same balance on “Creed.”

Both of Coogler’s first two features have musical scores by Ludwig Göransson.

The emergence of African-American filmmakers en mass the last several years is a healthy development in U.S. cinema as fresh, dynamic new voices and perspectives are added to the cultural stew. The days when Gordon Parks, Melvin Van Peebles, Michael Schultz, Sidney Poitier, Stan Lathan, Bill Duke, Charles Burnett, Charles Lane and Spike Lee were pretty much the only black American filmmakers are long gone. Individuals such as Carl Franklin, Kasi Lemmons, John Singleton, Julie Dash, Tim Reid, Cheryl Dunye, Kenny Leon, Antoine Fuqua, Regiald Hudlin, the Hughes Bros., F. Gary Gray, Tyler Perry began asserting themselves. And now a whole new wave has appeared after them, led by Ryan Coogler, Barry Jenkins, Mailk Vitthal, Dee Rees, and Jordan Peele, and more yet.

“Fruitvale Station” is showing on Netflix.

http://m.imdb.com/title/tt2334649/

Hot Movie Takes – “Private Hell 36”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Besides Netflix, my other regular source for discovering films these days is YouTube. I am always a sucker for a good film noir and so I decided to give “Private Hell 36” a look. Before seeing it, I was excited because the 1954 film had several things going for it. Director Don Siegel always showed a real flair for crime dramas. Co-writers Collier Young and Ida Lupino were true-crime screen veterans. Stars Howard Duff, Steve Cochran, Dean Jagger, Dorothy Malone, plus Lupino doing triple duty as supporting co-star and co-producer through her and Collier’s own Filmways company, all brought some acting chops. Cinematographer Burnett Guffey lit many classic crime films.

In terms of execution, the black and white picture does feature appropriately moody photography and music for its tale of one bad cop (Cochran) coercing his partner (Duff) into absconding with a large stash of counterfeit money tied to a murder suspect they’ve been investigating. Cochran’s character of Cal Bruner is a rogue and loose cannon who sees an opportunity to cash in quick and goes for it. He’s single and involved with a key witness in the case, a nightclub singer played by Lupino Duff’s character of Jack Farnham is a stable, honest cop and a married man (his wife’s played by Malone) with a kid. He’s a straight-shooter and though at first tempted to take the money himself he wants nothing to do with the hot loot. Meanwhile. Bruner doesn’t hesitate to pocket it, Farnham tries talking him out of it and then reluctantly goes along to get along with his partner. But Farnham is increasingly tormented by this criminal act he’s a party to. The secrets and lies to cover up the deed make him hate himself and the world. With Farnham ready to crack and spill the beans, Bruner’s liable to do anything to stop him.

It’s a good plot-line but getting to that moral conflict takes way too long and the writing and acting just don’t go deep enough to make this a classic, which I think it had the potential to be in more talented hands. I believe the film strayed too far from the core dramatic tension and spent too much time on the budding relationship between the bad cop and the singer-witness. There are also several dull scenes with the cops and witness scouting a race track to try and spot the suspect, who’s known to play the ponies. These scenes nearly stop the movie in its tracks – no pun intended. One telling scene there would have sufficed. And the wise police captain played by Jagger is a totally routine stock character who adds very little to the story except for the contrivances involving him at the end.

Much more could have been done with the stash site for the ill-gotten gains that is the inspiration for the film’s title.

All in all, it’s a fair to good movie that should keep you watching, but this is B movie fare all the way., which is to say that this potboiler didn’t have aspirations to anything more, and if it did, it failed to realize them.

Look for my Hot Movie Take on another. better crime film from that same era, “The Hitch-Hiker,” which Lupino directed, produced and co-wrote. She was a maverick woman filmmaker in Hollywood when there was no one else of her gender directing features or episodic television shows.

https://www.movie-trailer.co.uk/trailers/1954/private-hell-36

Hot Movie Takes – “The Hitch-Hiker” (1953)

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”