Archive

Soon Come: Neville Murray’s passion for Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its role in rebirthing North Omaha

The Loves Jazz & Arts Center in North Omaha is a symbol for the transition point that this largely African-American area is poised at – as decades of neglect are about to be impacted by a spate of major redevelopment. LJAC and some projects directly to the south of it along North 24th Street represented steps in the right direction but since then little else has happened in the way of renewal. Development efforts farther south, east, and west had little or no carryover effect. The subject of this story however is not so much the LJAC as it is its former director, Neville Murray, who was very much the director when I did this piece for The Reader (www.thereader.com) about three years ago. Murray expressed, just as his successor does today, the hope that the center would serve as anchor and catalyst for a boom in new activity in the area. The center never really realized that goal, but it still could. Murray is a passionate man, artist, and arts administrator with an interesting perspective on things since he’s not from Omaha originally. Indeed, he’s a native Jamaican. But as he explains right at the top of my story, he identifies closely with the African-American experience here and he’s committed to making a difference in the Omaha African-American community – one that’s been waiting a long time for change. If it’s up to him, it will soon come.

Soon Come: Neville Murray’s passion for Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its role in rebirthing North Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Oriignally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

“I’m an artist, first and foremost. I think everything else is just kind of a reflection of the art,” said Neville Murray, director of the Loves Jazz & Arts Center (LJAC), 2510 North 24th Street in Omaha. He came to the States in 1975 from his native Jamaica on a track scholarship that saw him compete for the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He’s made America and Nebraska his second home, but it is the north Omaha African American community the center serves where his heart lies.

“I consider myself African-American,” he said. “North Omaha is such a tremendous culture. There’s so much talent and there’s so much need. If we can just inspire kids to become artists or to becomeinvolved in the arts or to realize the role the arts can play in their lives…

“We’re really trying to change the dynamic by bringing world class arts programming to north Omaha and to bring in art one would not ordinarily see. Art is a catalyst for change. We’ve seen it downtown. And we think this can be a catalyst for change in our community.”

During a recent interview in the center conference room, which doubles as a storage space with stacks of art works leaning against the walls, he alluded to the year-and-a-half-old LJAC as trying to separate itself from “other organizations in the community” that have failed. The center’s “state of the art facility” is a big start. Another is his long track record as an administrator with the Nebraska Arts Council (NAC), where he worked prior to opening the center in 2005. Well-versed in grant writing and well-connected to the art world, he’s determined to avoid the pitfalls.

“We have to be at a different level in terms of our 501C3 meeting certain criteria with accountability (for programs and grants) and ownership of collections,” he said. “We have to set high standards. For me it’s critical we operate at a high level because of the history of some things.” When asked if he meant the troubled Great Plains Black History Museum a block to the east, he confirmed he did. He said that other venue’s long-standing problems of unarchived materials, unrealized repairs, unpolitic moves and unanswered questions stem from ineffective governance.

“It can’t be a hand-picked board. It needs to be a real board,” he said. “We have a great, pro-active, eight-member board.” The LJAC also has ongoing Peter Kiewit Foundation support. Even with that the center operates on the margin, with revenues coming chiefly from rental fees and grants rather than its light walk-in traffic. Murray was a one-man band for months after his only staffer resigned, leaving him doing everything from curating exhibits to cleaning floors. A Kiewit grant’s made possible the hiring of a new assistant. Still, he acknowledges problems — from the phone not always being manned to the doors not always being open during normal visiting hours to inadequate marketing and membership campaigns.

“I wear many different hats. There’s only so much you can do. It’s frustrating,” he said. “That has been an issue, you bet. I think that’s just part of our growing pains. Hopefully, that will resolve itself at some point in time. I’m not going to be here forever, but I want to make sure I put in place processes that can ensure the success of this institution into the future.”

Another barrier the center faces is one of identity and image. Some assume its solely focused on the legacy of Preston Love or a venture of the late musicians’s family. Neither is true. Others think it’s primarily a performance space when in fact it’s an exhibition/education space. Still others confuse it as a social service site. None of it deters him. “Ultimately, the goal for this institution is to be one of just a handful of accredited African American arts institutions” in America, he said.

The center grew out of many discussions Murray engaged in with members of the African American community. “We’d been meeting for years with a variety of folks about the need for an institution such as this in north Omaha,” he said.

Murray got to know greater Nebraska and north Omaha in particular as the NAC’s first multicultural coordinator in the 1990s. His work today at the LJAC is a natural extension of how his personal journey as an artist and arts administrator evolved to embrace his own Jamaican identity, the wider African American experience and the need to create more recognition and opportunities for fellow artists of color.

“It enriched me so much being able to travel all over Nebraska and work with indigenous folks to promote the arts,” he said. “To be able to work with different cultures, Latino and American Indian cultures, really inspired me, not just as an artist but in terms of my awareness. I began to realize the arts play a critical role in cultural development. A culture without art is dead. Art is what makes us human.”

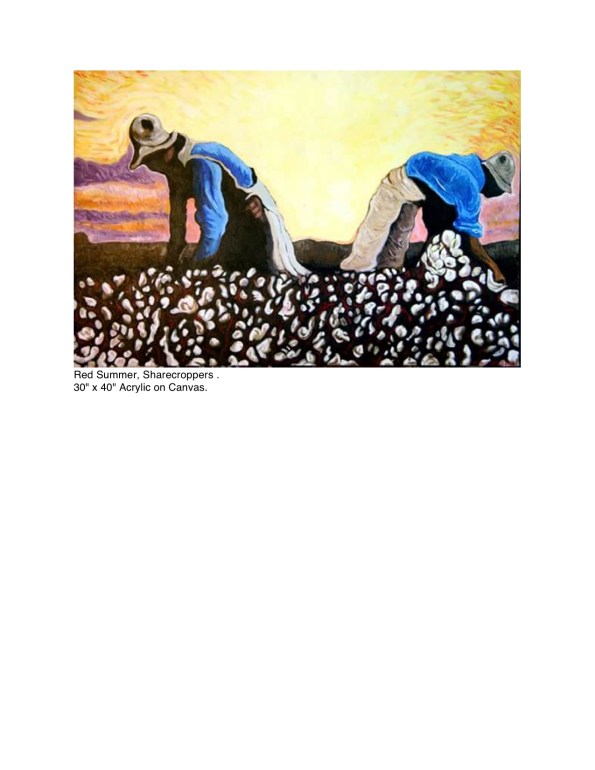

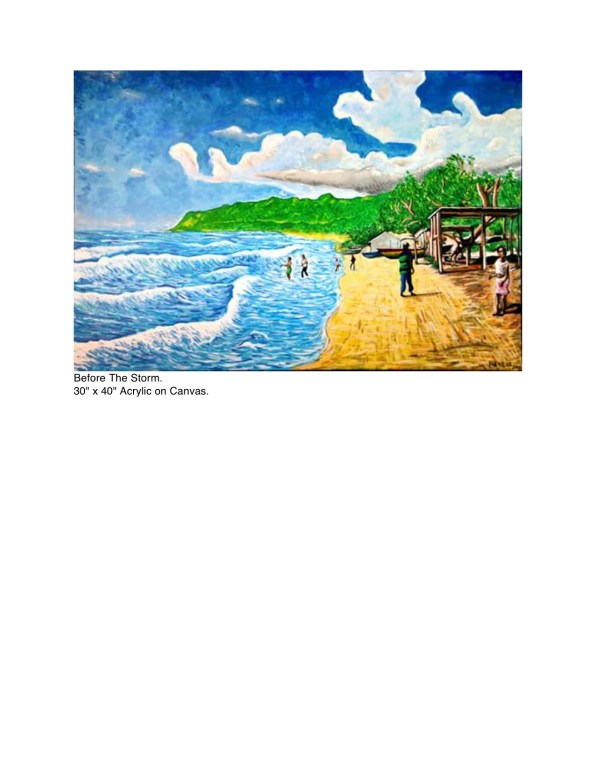

Besides, he fell in love with the state’s wide open spaces, variable topography, classic seasons and Northern Hemispheric light. “Nebraska’s such a beautiful state. If you drive straight from here to Colorado you don’t see it. But if you go just a few miles north of I-80 you’re in the Sand Hills and the vistas are just magnificent,” said Murray, whose paintings reflect his “love of nature” in iconic earth-tone images of the Great Plains or pastel seascapes of his tropical homeland.

He came to the NAC at a crucible time. His newly formed post was a response to protests over inequitable funding for artists of color. Inequity extended to museums/galleries, where works about and by black artists were absent, and to academia, where, he said, art textbooks at UNL failed to mention one of its own, grad Aaron Douglas, famed “illustrator of the Harlem Renaissance.”

Murray’s experience working with Nebraska’s Ponca population in their effort to be reinstated within the greater Ponca Tribe reflected his own sense of dislocation from his roots and the severing African Americans feel from their heritage.

“The Ponca had to relearn their traditions, so the NAC helped them get the grant funding to network back with the Southern Ponca down in Oklahoma to rediscover their dances and cultural traditions,” he said. “If as a tribe you’re cut off you lose a sense of your identity. I can relate to that because there was a period in my life when I can say I was kind of embarrassed at some of my rural upbringing. My grandmother used to walk five miles to market. People come from all over up in the mountains and bring their wares. Colors everywhere. Fruits of every ilk. Wonderful old stories. It took me a while to really appreciate all that. Now I look at it as a treasure and something we’re losing rapidly in the islands, I might add.”

“As black folks we’ve lost a sense of our identity. We’re confused. We don’t understand a lot of our traditions, even what tribes we come from. All of that was lost with slavery. Slavery’s had such a critical roles in our lives. It’s almost like we’re brand new,” he said. “Our whole life is a search, a journey for identity.”

Today, there’s more emphasis on black heritage and black art. “I think there’s much greater appreciation for art and artistic expression,” he said. “It’s not unusual to see artists of color in Art News now or other major art publications.”

Despite inroads, the place black artists hold in their own community and in the wider sphere of life is a work in progress. “It seems as black artists we’re always trying to validate ourselves. A few will come through. The flavor of the day, so to speak,” he said. “But as artists of color we we’re so often stigmatized. We have to get beyond that and recognize our art as an expression of our culture. We have a tendency in our community to look at arts as only recreation or extracurricular.”

His own ground breaking path reflects the possibilities for artists of color today. “I’ve kind of been doing a lot of things that hadn’t been done before,” he said. He was one of the first state multicultural coordinators in the nation. He pioneered the use of digital technology for Nebraska-curated shows. He organized the first comprehensive touring exhibit of contemporary Jamaican art with the 2000 Soon Come: The Art of Contemporary Jamaica. The project took him to parts of the island he’d never visited and introduced him to its diverse spectrum of artists.

He continues to celebrate art and to explore “what does it mean to be an artist of color?” at the LJAC, where he’s brought exhibits by renowned artists Frederick Brown, Faith Ringgold and Ibiyinka. In late November paintings from the Revival Series of noted artist Bernard Stanley Hoyes opens. The LJAC will publish its first catalogue for the show.

On display from time to time is work by local artists like Wanda Ewing, whose images deal with being a woman of color. It hosts regular art classes for adults/kids and occasional lectures/workshops. In keeping with its historic, symbol-laden location, the LJAC presents socially relevant programs, such as a History of Omaha Jazz panel held this year and the current Freedom Journey civil rights exhibit. All around the center, businesses flourished, streets teemed, marches proceeded, riots burned and hot jazz sessions played out. In a nod to political awareness, activist Angela Davis will appear there November 11.

Murray’s penchant for technology is evident in interactive stations/kiosks. An oral history project he’s doing with the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where he also studied, documents, in high def video, the lives/stories of older African American residents. The materials will inform a documentary about the history of black Omaha and its music heritage. The archived interviews will be available to scholars. He looks forward to curating a new exhibit around a group of photos from a local collector that record some of the earliest images of local African American life. A selection from the LJAC permanent collection displays photos of early African American scenes and moments from the career of namesake Preston Love.

Murray’s also in discussions for the LJAC to be an outreach center for New York’s Lincoln Center. “I’m really excited about that,” he said. “That gives us an opportunity to bring in some coeducational programming and performances.” It’s all about his trying to engage people with art in news ways. He said, “I would hope I bring a certain creativity to this position as an artist.”

He knows he and the center will be judged by their longevity. “You have to have a period of time when people can see if you’re going to be here for a while,” he said.” “I think folks feel good about we’re doing. I think people realize my heart is in the right place. I have a love of this community and the culture. It’s a huge challenge. It’s a big responsibility. But it’s been a wonderful experience.”

Related articles

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Overarching Plan for North Omaha Development Now in Place, Disinvested Community Hopeful Long Promised Change Follows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Lifetime Friends, Native Sons, Entrepreneurs Michael Green and Dick Davis Lead Efforts to Revive North Omaha and to Empower its Black Citizenry (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omowale Akintunde’s In-Your-Face Race Film for the New Millennium, ‘Wigger,’ Introduces America to a New Cinema Voice (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Negro Leagues Baseball Museum Exhibits on Display for the College World Series; In Bringing the Shows to Omaha the Great Plains Black History Museum Announces it’s Back (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Brief History of Omaha’s Civil Rights Struggle Distilled in Black and White By Photographer Rudy Smith (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha’s Malcolm X Memorial Foundation Comes into its Own, As the Nonprofit Eyes Grand Plans it Weighs How Much Support Exists to Realize Them (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Blacks of Distinction II (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Outward Bound Omaha Uses Experiential Education to Challenge and Inspire Youth (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Frederick Brown’s journey through art: Passage across form and passing on legacy

UPDATE: The subject of this story, artist Frederick Brown, passed away in the spring of 2012.

An Omaha cultural venue that has never enjoyed the attendance it deserves is the Loves Jazz & Arts Center. Then again, poor marketing efforts by the center help explain why so few venture to this diamond in the rough resource. The fact it’s located in a perceived high-risk, little-to-see-there area doesn’t help, but without the promotional initiative to drive people in numbers there it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of folks avoiding the area like the plague. All of which is a shame because the center’s programming, while lacking full professional follow-through, has a lot to offer. An example of some very cool LJAC programs from a few years ago were workshops that noted artist Frederick Brown conducted there in conjunction with an exhibition of his work at Joslyn Art Museum. Some of Brown’s paintings of jazz and blues legends ended up on display at the center. I interviewed Brown during his Omaha visit and I think I managed capturing in print his spirit. The story originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Frederick Brown’s journey through art: Passage across form and passing on legacy

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

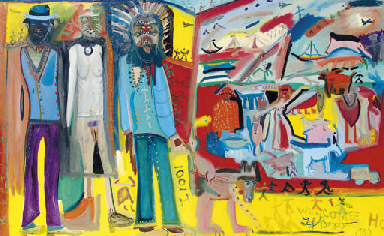

Leading contemporary American artist Frederick Brown offered a glimpse inside the ultra-cool, super-sophisticated New York salon and studio scene during a June visit to Omaha in conjunction with his current exhibition at Joslyn Art Museum. Showing through September 4, Portraits of Music I Love is a selection of Brown’s huge, ever expanding body of work devoted to jazz and blues artists under whose influence he came of age in the American avant garde movement of the 1960s and ‘70s.

The Georgia-born Brown was raised in Chicago, where he was steeped in the Delta Blues tradition that seminal figures like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon and Jimmy Reed, neighbors and friends, brought from the South. He grew up with Anthony Braxton. Later, in New York, he fell under the spell of jazz masters Ornette Coleman and Chet Baker. His intimate circle also encompassed the who’s-who of post-modern American painters, including his mentor, Willem deKooning. It was in this rarefied atmosphere of appreciation and collaboration Brown blossomed. He observed. He absorbed. He shared. The only condition for hanging with this heady crew, he said, was to “be unique — to bring something to the table.”

“At that time one of the nice things about living in an artist’s community like SoHo was that you had these people all around you who were at the top of their game and of the avant garde scene and of the aesthetic thing. I didn’t have to invent the wheel. The standard was set. Plus, right in front of me, I saw the work ethic. You could go to their studio or they could come to yours, and you could partake in whatever you wanted to partake in and discuss aesthetics at the highest level. You had all this kind of wisdom, information, feedback and back-and-forth,” he said.

Given all the time he’s spent with musicians, it’s perhaps inevitable Brown speaks in the idiom of a jazzman. That is to say he patters away in a hip, improvisational riff that sings with the eloquence of his thoughts, the musicality of his language and the richness of his associations, stringing words and ideas together like notes.

New York was the start of his being consumed with making it as an artist. “Total immersion. 24/7. Total commitment. Either I make it or die. A total spartan kind of situation,” he said, adding the artists befriending him “accepted and encouraged me.” Art is not only his inspiration but a legacy he must carry on. A set of musicians he was tight with, including Magic Sam and Earl Hooker, made him pledge long ago that after they were gone he’d preserve their heritage through his work. Then, after emerging as a bright new force in New York, his chronically troubled tonsils grew infected, but Brown had neither the insurance nor the cash to pay for an operation. He was resigned to dying when an anonymous benefactor stepped forward to foot the bill. It was 20 years before he learned his musician friends had ponied up to save his life. Ever since then, he’s felt a debt to further the art of jazz. His paintings at Joslyn represent a fraction of the music portraits he’s done as the fulfillment of that “promise.” At his 30,000-square foot studio in Carefree, Arizona he’s working on a 450-work National Portrait Gallery-curated series of jazz icons that will tour the world under the aegis of the U.S. State Department.

Jazz and blues artist Frederick J. Brown displays his painting “Stagger Lee,” in Kansas City, Mo.

Architecture was Brown’s first field, but when painting began speaking to him more deeply, he chose the life of an artist. He hit the ground running upon his 1970 arrival in New York, where he was immediately embraced for his talent, intellect and curiosity and for the fluidity of his technique and the originality of his vision.

“I’ve always had an innate ability to look at something or hear something and then do it. I could always paint in every style. If styles are languages, then I’m fluent in all of them. I never felt like any were above me or below me,” he said.

In amazingly short order, his work was exhibited in the Whitney Biennial, the Marlboro Gallery and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

He first made his mark in the realm of abstract expressionism, but always looking to stay “10 years ahead of the curve,” he changed directions to more figurative work and is often credited with helping bring back the figure in contemporary art. The small selection of his paintings at Joslyn are expressionistic figurative portraits that employ iridescent colors and bold brush strokes to evoke the singular essence and creative spark of such artists as Count Basie, Coleman Hawkins, Billy Holiday, Billy Eckstine, Bessie Smith, Dinah Washington and the late Ray Charles.

The prolific and versatile Brown is that rare artist with the ability to produce at the highest level while churning out a prodigious volume of pieces in quick succession. He’s tackled ambitious series’, massive single works, “mosaics” that fill entire rooms and themes ranging from the history of art to the Assumption of Mary. Still indefatigble at age 60, he can paint for hours without a break, as he did 13 hours straight during celebrated tours of China in the late ‘80s, and complete a fully realized work in the span of a musical cut or joint, something he’s done on countless occasions at rehearsals and recording sessions with musicians. Hanging with “the cats” at those jams, Brown does his thing and paints while they do their thing and play. Together, in harmony, each gives expression to the other.

“When you have people expressing, live, their spirit — in music, dance, poetry — these elements are cross pollinating the whole environment and gives the place another spirit and vibe and rhythm, too,” he said. “I’ve always painted very quickly. I can paint in the same rhythm and motion as the music. In fact, I can do one painting while they do one tune. So, every day doing that, doing that, for like 15 years — 30-40 paintings a day — every day, every day for all those years, you get to a certain level where it’s just like natural and you forget that it’s anything special.”

His experiences with performing and visual artists have prompted him to explore the mysteries of capturing music on canvas via color. “To hear Ed Blackwell play, it sounded like it was raining on the drums,” he said. “So, how do you translate that into color?” To get it right, Brown embarked on a study of color theories, harmonies and contrasts. “It’s like what color do you put next to another color to make that color brightest? It’s the same kind of thing you have in music. They’re all just notes. It made me have to think about this, where before it was just instinctual. Once I got it down, I didn’t have to think about it. It became subliminal again. And then I was just reacting to the sounds…and seeing the music.”

Welcome Home by Frederick Brown

In a series of cooperative workshops Brown conducted at the new Loves Jazz & Arts Center on North 24th Street, he simulated the fertile environs of the haute couture salons and loft studios he’s so familiar with. As his workshop students applied brush to canvas, bongo players beat out a driving rhythm, life models struck dance poses and Brown, turned out smartly in suit and shades, navigated the room, stopping at each easel to offer insight and encouragement to the students, who included some of Omaha’s best known artists. It was a sensual, visceral experience.

Brown’s painted this way for decades, using music as a channel for summoning his muse. “I always have music when I’m painting. I listen to a whole spectrum of music.” It’s about setting a mood for ushering in the shamanistic spirit he feels he possesses. Art as communion. “It’s like doing a jazz solo. You’re in that stream. It’s like a total zone you’re in and it just happens. You’re not conscious of it. In one sense my painting is like automatic writing,” he said. “No one can reproduce it, either.” It’s how he goes about painting his portraits of singers or musicians.

“When I’m doing this stuff I have their music playing or I have a photograph of them out,” he said. “Their spirit has to agree to come into that painting. In essence, I provide a painterly body for their spirit to inhabit. I’m a vehicle or a conduit for this information to pass through. Until the painting has a soul or a spirit, then it’s just paint on canvas. I just work on it until their spirit is satisfied,” he said. “You have to get in this like protective, almost out-of-body experience. With some people, like Johnny Hodges, you can express everything about them very quickly and simply. Others, like (Thelonious) Monk, are more complex. But sometimes you can catch the most complex situation in the fewest strokes.

“People always say, How do you know when you’re finished? Because it won’t allow you to touch it. The thing is complete. It doesn’t need any more brush strokes.”

Brown made his Omaha workshops a vehicle for exposing participants to new “possibilities” — “pushing” artists beyond self-imposed “limits” by having them, for example, create 24 paintings in a single night. He also made the classes a means for imbuing the Loves Center, whose mission is to be a venue where all the arts meet, with a synergistic “energy” open to all forms of expression. “What it comes down to is one person expressing themselves in a certain way and being inspired by different mediums. It’s getting more people involved. It’s opening minds, just like Ornette and them did for me.”

Related articles

- When Jazz Married Art (doublelattebooks.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Yolonda Ross Takes It to the Limit (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Camille Metoyer Moten, A Singer for All Seasons (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Frederick J. Brown, Painter of Musicians, Dies at 67 (nytimes.com)

- Eddith Buis, A Life Immersed in Art (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- For Love of Art and Cinema, Danny Lee Ladely Follows His Muse (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jazz-Plena Fusion Artist Miguel Zenon Bridges Worlds of Music (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Peter Buffett Completes the Circle of Life Furthering the Legacy of Kent Bellows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)