Archive

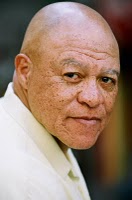

Rev. Everett Reynolds Gave Voice to the Voiceless

Another Omaha elder leader has passed. The Rev. Everett Reynolds spent the better part of his life fighting the good fight against injustice. The following in memoriam piece I wrote appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Rev. Everett Reynolds Gave Voice to the Voiceless

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Rev. Everett Reynolds was not from Nebraska but he’s remembered as someone who made a significant mark here.

The St. Louis, Mo. native passed earlier this week in Omaha at age 83.

As a United Methodist minister and community leader he led congregations, worked with parolees, headed the local chapter of the NAACP, founded Cox Cable television channel CTI-22 and advocated for civil rights.

His work followed that of his father and grandfather, who were preachers. But for a long time Reynolds resisted The Call.

As a youth, he moved with his family to Lincoln, Neb., where his father pastored a church. After his father took over at Clair Memorial United Methodist Church in Omaha, Reynolds attended Technical High School.

But school and church were far from his mind. He heeded another calling, music, to become a professional musician in touring dance bands. He sang ballads and blues and played bass violin. He sat in with such legends as Count Basie and Lionel Hampton. He also played for top Omaha Midwest touring bands led by Lloyd Hunter and Earl Graves.

It was a heady time, but as the years went by he got caught up in the night life. Women. Booze. His alcoholism made him a liability. Once, after a week-long bender, he woke up in Houston, unable to remember what happened. Exiled from the band, this Prodigal Son finally returned home.

In a 2004 interview he said after failing to kick his drinking habit, he asked for divine help, and this time he stayed dry. In 1950, he rejoined the church and married. He and his wife Shirley celebrated their 61st wedding anniversary last year. His fall from grace and his subsequent recovery and rebirth, he said, gave his ministry “a message” for anyone straying from The Word. “For I have been there.”

He made his ministry an extension of his work as a Nebraska parole officer. In his duals roles he said he often shared with youth his own experiences.

He made his ministry an extension of his work as a Nebraska parole officer. In his duals roles he said he often shared with youth his own experiences.Reynolds, who held a theology degree and a doctorate, eventually took over his father’s pulpit at Clair Methodist. A consistent theme he delivered as a preacher is that “we’re all created equal in the sight of God. One blood are we.” Black or white, he said, shouldn’t matter. “When we reduce our faith to race, we’ve reduced our faith. Each time we make an advance, it’s for all people, not one.”

“My father was against any kind of inequitable treatment of people, of any people,” says Trip Reynolds, one of the late pastor’s three sons. “That’s his hallmark. Some people talk it — my dad was frequently acknowledged for practicing what he preached.”

Rev. Reynolds went on to pastor Lefler United Methodist Church. During his tenure, he assumed leadership of the Omaha NAACP. It was a tough time for the organization, locally and nationally, with declining memberships and a flagging mission.

As a NAACP spokesman he made his voice heard on hot button incidents like alleged police brutality. He raised awareness. He advocated dialogue. He organized protests. He called press conferences. The cable channel he founded, which originated as Religious Telecast Inc. before changing names to Community Telecast Inc., was created as a forum for minority voices to be heard. Trip Reynolds ran the channel with his father and today is general manager.

The late minister is remembered as the conscience of a community.

“He was very strong and intense in what he believed in,” says Metropolitan Community College liaison Tommie Wilson.”Powerful, intelligent. He knew civil rights backwards and forwards, and he stepped out there and he did it — fighting for justice for everybody. He was a fine man and quite a leader.”

“He took on some really difficult and sometime controversial cases, and he did that knowing what the consequences were and being unafraid to address those consequences,” says Omaha City Councilman Ben Gray. “He also helped create alternative programming and an opportunity for different voices.”

Along the way, Reynolds made clear the NAACP’s watchdog mission is still relevant. “Our struggle continues. People are still hurting because of inequities in such areas as education, employment, voting and the criminal justice system,” he once told a reporter.

When Reynolds stepped down as Omaha NAACP president in 2004, he recommended Tommie Wilson succeed him.

“I feel Dr Reynolds is responsible for me appreciating my history and me wanting to follow those big shoes he wore,” says Wilson. “When he asked me to take over it intensified in me my desire to do all I could to do to make a difference.”

Clair United Methodist Church, 5544 Ames Ave., is hosting a Friday wake service from 6 to 8 p.m., and a Saturday funeral service at noon.

Related articles

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- An Omaha Legacy Ends, Wesley House Shutters after 139 Years – New Use for Site Unknown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- North Omaha Champion Frank Brown Fights the Good Fight (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

“Walking Behind to Freedom” – A musical theater examination of race

I don’t see a huge amount of live theater, but I attend more than enough shows to give me a good feel for what’s out there. My hometown of Omaha has a strong theater scene and one of the more dynamic works I’ve seen here in recent years came and went without the attention I felt it deserved. It was called Walking Behind to Freedom, and it deal head-on with many persistent aspects of racism that tend to be trivialized or distorted. The fact that a fairly serious piece of theater dared to tackle the issue of race in a city that has long been divided along racial lines took courage and vision. Playwright Max Sparber, a former colleague and editor of mine at The Reader (www.thereader.com) based the play, which unfolds in a series of vignettes, on interviews he did with folks from all races around the community. He asked people to share experiences they’ve had with racism and how these encounters affected them. A local musical group called Nu Beginning wrote songs and music that expressed yet more layers of insight and emotion behind the dramatized experiences. A diverse group of cast and crew collaborated on a rousing, moving, thought-provoking night of musical theater. I had a personal investment in the show, too, in that my partner in life played a couple different speaking parts. She was quite good. My story about the show appeared in The Reader.

“Walking Behind to Freedom” – A musical theater examination of race

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The subject of race is like the elephant in the room. Everybody notices it, yet nobody breathes a word. The longer the silence, the more damage is done. Seen in another light, race is the label comprising the assumptions and perceptions others project on us, soley based on the shade of our skin or sound of our name. Seeing beyond labels sparks dialogue. Stopping there erects barriers to communication.

Race is as uncomfortable to discuss as sex. Yet, attitudes about race, like sex, permeate life. It’s right there, in your face, every day. You’re reminded of it whenever someone different from you enters your space or you’re the odd one out in a crowd or issues of profiling, preferences and quotas hit close to home.

It often seems Omaha’s predominantly white population wishes the topic would go away in a weary — Oh, didn’t-we-solve-racism-already? tone — or else makes limp liberal gestures toward more inclusion. Then there’s the majority reaction that pretends it’s not a problem. Take the Keystone neighborhood residents now opposing the Omaha Housing Authority’s planned Crown Creek public housing development. Opponents never mention race per se, but it’s implicit in their expressed concerns over property values being adversely affected by public housing whose occupants will include blacks. Nothing like rolling out the old welcome wagon for people trying to get ahead.

On the other side of the fence, militant minority views claim that race impacts everything, as well it might, but such sweeping indictments alienate people and chill discussion. How much an issue race is depends on who you are. If you have power, it’s not on your radar, unless it’s expedient to be. If you’re poor, it’s a factor you must account for because someone’s sure to make you aware of it.

If you doubt Omaha is beset by wide rifts along racial lines, you only need look at: its pronounced geographic segregation; its mainly white police presence in largely Latino south Omaha and African-American north Omaha; its rarely more than symbolic multicultural diversity at public-private gatherings; its few minority corporate heads and even fewer minority elected public officials. Then there’s the insidious every day racism that, intentionally or not, insults, demeans, excludes.

It’s in this climate that, last fall, Omaha Together One Community (OTOC) said: We need to talk. A faith-based community organizing group focusing on social justice issues, OTOC commissioned an original musical play, Walking Behind to Freedom, as a benefit forum for addressing the often ignored racial divide in Omaha and the need for more unity. It’s the second year in a row OTOC’s staged a play to frame issues and raise funds. In 2003, it presented a production of Working, the Broadway play based on the book of the same name by Studs Terkel.

With a book by Omaha playwright Max Sparber and music by the local quartet Nu Beginning, Walking Behind to Freedom premieres May 7 and 8 at First United Methodist Church. Performances run 7:30 p.m. each night at the church, 69th and Cass Street. Free-will donations of $10-plus are suggested. Proceeds go to underwrite OTOC operational expenses.

The play’s title is lifted from a famous quote by the late entertainer and Civil Rights activist, Hazel Scott, who posited, “Who ever walked behind anyone to freedom? If we can’t go hand in hand, I don’t want to go.” The show coincides with the 40th anniversary of Congress passing landmark Civil Rights legislation in 1964.

Max Sparber

As a foundation for the play, OTOC did what it does best: organize “house meetings” where citizens shared their anecdotes and perspectives on racial division. Sparber and Nu Beginning attended the meetings, held at OTOC-member churches city-wide, and the ensuing conversations informed the non-narrative play, which is structured as a series of thematic monologues, dialogues and songs.

“I built my script based on some of these interviews, along with some broader themes,” said Sparber, whose Minstrel Show dealt with an actual lynching in early Omaha. “We got some great stories out of it. The people who came to the meetings were very interested in the subject and I certainly got some stories that were invaluable. More than anything, we wanted this play to be specific to Omaha, and therefore we wanted its origins to be within Omahans’ own experiences.”

Surfacing prominently in those sessions was the theme of division and how by going unspoken it only deepens the divide. “This is a town that’s very separated geographically. The majority of blacks live in north Omaha. The majority of Latinos live in south Omaha. The majority of whites live in west Omaha. And, as a result, there’s not a lot of crossover,” Sparber said. “It’s really sad how closed up Omaha is,” said the play’s director, Don Nguyen, lately of the Shelterbelt Theater.

“Along with that, race is quickly becoming an undiscussed element in Omaha,” added Sparber. “I think a lot of whites believe we live in a post-racism world and, therefore, it’s not a subject that needs to be addressed. Whereas, black people experience this as not being a post-racism world at all and are kind of startled by this other viewpoint. So, there’s this disconnection based on understanding.”

|

Two lines in the play comment on this dichotomy: “I think a lot of white people feel that racism ended in the Sixties, with Martin Luther King. The only thing about racism that ended in the Sixties WAS Martin Luther King.”

Any impression all the work is done alarms Betty Tipler, an OTOC leader. “A lot of us are in our comfortable spaces. We go inside our houses with our two garages and we think things are okay. Things are not okay. The issue of race has not been cured and, if we’re not careful, things will go backward,” she said. Despite the illusion all’s well, she added, the play reminds us people of color still contend with bias/discrimination in jobs, housing, policing. “We may as well face it.”

According to OTOC leader Margaret Gilmore, the process the play sprang from is at the core of how the organization works. “We’re about bringing different people in conversation with each other to talk about what’s in their hearts and minds,” she said. “It’s a process of learning to talk to each other and listen to each other and then seeing what we have in common to work together for change.” She said the meetings that laid the play’s groundwork crystallized the racial gulf that exists and the need to discuss it. “We don’t talk about this stuff enough. We don’t talk about it on a personal level and how it affects us, which is what I think this play gets to. When we ask the right questions and we’re willing to listen, then the experiences that people tell in their own words are dramatic and provocative.”

“It’s very important we listen to real people’s stories. The only way you can come up with the truth is to go to the people. We haven’t watered down or changed their stories, but literally portrayed them,” said OTOC’s Tipler, administrator at Mount Nebo Missionary Baptist Church, which hosted some of the house meetings.

Indeed, the vignettes carry the ring of reportorial truth to them. Most compelling are the monologues, which unfold in a rap-like stream-of-consciousness that is one part slam-poet-soliloquy and one part from-the-street-rant. Some stories resemble the bared soul testimony of people bearing witness, yet without ever droning on into didactic, pedantic sermons, lectures or diatribes. The language sounds like the real conversations you have inside your head or that spontaneously spring up among friends over a few drinks. Often, there’s a sense you’re listening in on the privileged, private exchanges of people from another culture as they describe what’s it like to be them, which is to say, apart from you.

Don Nguyen

For director Nguyen, the “real life testimonies” add a layer of truth that elevates the material to a “more powerful” plane. “I think it will definitely work for us that people know this is real. It’s not an overall work of fiction. This is real stuff.”

The misconceptions people have of each other are voiced throughout the work, often with satire. You’ve heard them before and perhaps been guilty yourself assigning these to people. You know, you see an Asian-American, like Nguyen, and you reflexively think he’s fluent in Vietmanese or expert in martial arts, some assumptions he’s endured himself. “Oh, yeah, my personal experiences definitely help me to relate,” he said. “Growing up in Lincoln I got in fights all the time. People making fun of me. Thinking I knew kung-fu or I only spoke Vietmanese, which is not true. But it’s not just the blatant racism. It’s the underlying stuff, too. Sometimes it’s not even intentional, but it’s just there. And it’s that gray stuff I think these pieces capture pretty well and that people need to hear more of.”

In the vignette Tricky, some women lay out the subtle nature of racism in Omaha. “…it’s like a fox. It’s tricky. It’s sly. You’ll be standing in line at a store, and the cashiers will be helping everybody except you…and you’re the only black person in line…and because it’s so sly, I think white people don’t notice it at all.”

The play also looks at racism from different angles. One has a guilt-ridden realtor rationalizing the unethical practice of steering, which is another form of red lining. The other has a new generation bigot defending his right to espouse white pride in response to black heritage celebrations. The concept of reverse racism is explored in the real life case of students protesting their school’s special recognition of black achievers at the expense of other minorities. And the wider fallout of racism is examined in the confession offered by an insurance agent, who reveals rates for car-house coverage are higher for residents of largely black north Omaha, including whites, because of the district’s perceived high crime rate.

The vignettes touch on ways race factors into every day life, whether its the unwanted attention a black couple attracts while out shopping or the hassle African-American men face when driving while black, or DWB, which is all it takes to be stopped by the cops. The shopping piece uses humor to highlight the absurd fears that prompt people to act out racist views. Music is used as heightened counterpoint to the boiling frustration of the DWB victim, whose cries of injustice are accompanied by the soulful strains of doo-wop singers.

Bridging the play’s series of one-acts are songs by Nu Beginning, whose music is a melange of hip-hop, R & B, soul, pop and gospel. A little edgy and a lot inspirational, the music drives home the unity message with its uplifting melodies, which are sung by choruses comprised of diverse singers.

Some pieces are heavier or angrier than others. Some are downright funny. And some, like Mirrors, speak eloquently and wittily to the concept of how, despite our apparent differences, we are all reflections of each other. Here, Nguyen employs a diverse roster of performers to represent the mirror symbol. Perhaps the most telling piece is Function. This beautifully-rendered and thought-provoking discourse is delivered by an architect, who suggests racism has survived as both an ornament of the past, akin to a Roman column on a modern house, and as a still-functional device for those in power, as when a politician plays the race card.

Whatever the context, there’s no dancing around the race card, which is just how Nguyen likes it, although when he first read the script he was surprised by how brazenly it took on taboo material, such as its use of the N-word.

“Typically, a script or show sugarcoats the issue of race. It’s a very cautious topic. You don’t want to offend or patronize people by saying the wrong stuff. But this piece is much different. All of its pretty much in your face,” Nguyen said. “What I mean is, it’s very direct. Max (Sparber) makes no bones what he’s writing about, which is great. It’s a big risk to take as a writer, but essentially it’s the most interesting path to take, too. And I’m all for stirring up trouble. I’m fine with that.”

OTOC’s Betty Tipler feels racial division is too important an issue to be coy about. “We’ve got to come out of the closet, so to speak, and talk about racism and differences” she said. “We tend to shy away from talking about it, but it won’t go away. We have got to come together, put it on the table, take a look at it and deal with it — no matter how much it hurts me or how much it hurts you. But before we can do that, we’ve gotta put it out there. We won’t get anywhere until we do. And I believe this play is a step toward doing that.”

Christy Woods, a singer/songwriter with Nu Beginning, said the play is about hope. “I believe if people are open to change, we can go hand-in-hand to freedom. Just because I’m this and you’re that, doesn’t mean I have to be one step behind you. Why can’t we go together? We want people to feel inspired to go out and make a change. We want to touch, but also to teach, and I believe this musical does that.”

Nguyen hopes the play attracts a mixed audience receptive to seeing race through the prism of different experiences. “That’s where I’m trying to aim the show. As we go through these vignettes, I want some people to identify with them and some people to be like, ‘Oh, I didn’t know that.’ That’s what I want to create.”

Related articles

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Kevyn Morrow’s Homecoming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Native Steve Marantz Looks Back at the City’s ’68 Racial Divide Through the Prism of Hoops in His New Book, ‘The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Hey, You, Get Off of My Cloud! Doug Paterson – Acolyte of Theatre of the Oppressed Founder Augusto Boal and Advocate of Art as Social Action (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Theater as Insurrection, Social Commentary and Corporate Training Tool (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Polishing Gem: Behind the Scenes of the Beasley Theater & Workshop’s Staging of August Wilson’s ‘Gem of the Ocean ‘ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Back in the Day: Native Omaha Days is reunion, homecoming, heritage celebration and party all in one

Even though I grew up in North Omaha and lived there until age 43 or so, I didn’t experience my first Native Omaha Days until I had moved out of the area, and by then I was 45, and the only reason I did intersect with The Days then, and subsequently have since, is because I was reporting on it. The fact that I didn’t connect with it before is not unusual because it is essentially though by no means exclusively an African American celebration, and as you can see by my picture I am a white guy. Then there’s the fact it is a highly social affair and I am anything but social, that is unless prevailed upon to be by circumstance or assignment. But I was aware of the event, admittedly vaguely so most of my life, and I eventually did press my editors at The Reader (www.thereader.com) to let me cover it. And so over the past eight years I have filed several stories related to Native Omaha Days, most of which you can now find on this blog in the run up to this year’s festival, which is July 27-August 1. The story below is my most extensive in terms of trying to capture the spirit and the tradition of The Days, which encompasses many activities and brings back thousands of native Omahans – nobody’s really sure how many – for a week or more of catching up family, friends, old haunts.

NOTE: The parade that is a highlight of The Days was traditionally held on North 24th Street but has more recently been moved to North 30th Street, where the parade pictures below were taken by Cyclops-Optic, Jack David Hubbell.

My blog also features many other stories related to Omaha’s African American community, past and present. Check out the stories, as I’m sure you’ll find several things that interest you, just as I have in pursuing these stories the last 12 years or so.

Vera Johnson,a Native Omahans Club founder, (Photo by Robyn Wisch)

Back in the Day: Native Omaha Days is reunion, homecoming, heritage celebration and party all in one

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

A homecoming. That’s what Native Omaha Days, a warm, rousing, week-long black heritage reunion, means to the thousands of native sons and daughters coming back in town for this biennial summer celebration. Although the spree, which unfolded July 30 through August 4 this year, features an official itinerary of activities, including a gospel night, a drill team competition, a parade, a dance and a picnic, a far larger slate of underground doings goes on between the many family and class reunions, live concerts and parties that fill out the Days. Some revelers arrive before the merriment begins, others join the fun in progress and a few stay over well after it’s done. A revival and carnival in one, the Days is a refreshing, relaxing antidote to mainstream Omaha’s uptight ways.

North Omaha bars, clubs and restaurants bustle with the influx of out-of-towners mixing with family and old friends. North 24th Street is a river of traffic as people drive the drag to see old sites and relive old times. Neighborhoods jump to the beat of hip-hop, R&B and soul resounding from house parties and family gatherings under way. Even staid Joslyn Art Museum and its stodgy Jazz on the Green take on a new earthy, urban vibe from the added black presence. As one member of the sponsoring Native Omahans Club said of the festival, “this is our Mardi Gras.”

Shirley Stapleton-Odems is typical of those making the pilgrimage. Born and raised in Omaha — a graduate of Howard Kennedy Elementary School and Technical High School — Stapleton-Odems is a small business owner in Milwaukee who wouldn’t miss the Days for anything. “Every two years I come back…and it’s hard sometimes for me to do, but no matter what I make it happen,” she said. “I have friends who come from all over the country to this, and I see some people I haven’t seen in years. We all meet here. We’re so happy to see each other. It’s a reunion thing. It’s like no matter how long you’re gone, this is still home to us.”

As Omaha jazz-blues guru Preston Love, a former Basie sideman and Motown band leader and the author of the acclaimed book A Thousand Honey Creeks Later, observed, “Omahans are clannish” by nature. “There’s a certain kindredness. Once you’re Omaha, you’re Omaha.” Or, as David Deal, whose Skeets Ribs & Chicken has been a fixture on 24th Street since 1952, puts it, “People that moved away, they’re not out-of-towners, they’re still Omahans — they just live someplace else.” Deal sees many benefits from the summer migration. “It’s an opportunity for people to come back to see who’s still here and who’s passed on. It’s an economic boost to businesses in North Omaha.”

Homecoming returnees like Stapleton-Odems feel as if they are taking part in something unique. She said, “I don’t know of any place in the country where they have something like this where so many people over so many generations come together.” Ironically, the fest’ was inspired by long-standing Los Angeles and Chicago galas where transplanted black Nebraskans celebrate their roots. Locals who’ve attended the L.A. gig say it doesn’t compare with Omaha’s, which goes to the hilt in welcoming back natives.

Perhaps the most symbolic event of the week is the mammoth Saturday parade that courses down historic North 24th Street. It is an impressionistic scene of commerce and culture straight out of a Spike Lee film. On a hot August day, thousands of spectators line either side of the street, everyone insinuating their bodies into whatever patch of shade they can find. Hand-held fans provide the only breeze.

Vendors, selling everything from paintings to CDs to jewelry to hot foods and cold beverages to fresh fruits and vegetables, pitch their products under tents staked out in parking lots and grassy knolls. Grills and smokers work overtime, wafting the hickory-scented aroma of barbecue through the air. Interspersed at regular intervals between the caravan of decorated floats festooned with signs hawking various local car dealerships, beauty shops, fraternal associations and family trees are the funky drill teams, whose dancers shake their booties and grind their hips to the precise, rhythmic snaring of whirling dervish drummers. Paraders variously hand-out or toss everything from beads to suckers to grab-bags full of goodies.

A miked DJ “narrates” the action from an abandoned gas station, at one point mimicking the staccato sound of the drilling. A man bedecked in Civil War-era Union garb marches with a giant placard held overhead emblazoned with freedom slogans, barking into a bullhorn his diatribe against war mongers. A woman hands out spiritual messages.

Long the crux of the black community, 24th Street or “Deuce Four” as denizens know it, is where spectators not only take in the parade as it passes familiar landmarks but where they greet familiar figures with How ya’ all doin’? embraces and engage in free-flowing reminiscences about days gone by. Everywhere, a reunion of some sort unfolds around you. Love is in the air.

The parade had a celebrity this time — Omaha native actress Gabrielle Union (Deliver Us From Eva). Looking fabulous in a cap, blouse and shorts, she sat atop the back seat of a convertible sedan sponsored by her father’s family, the Abrams, whose reunion concided with the fest’. “This is just all about the people of north Omaha showing pride for the community and reaching out to each other and committing to a sense of togetherness,” said Union, also a member of the Bryant-Fisher family, which has a large stake in and presence at the Days. “It’s basically like a renewal. Each generation comes down and everyone sits around and talks. It’s like a passing of oral history, which is…a staple of our community and our culture. It’s kind of cool being part of it.”

She said being back in the hood evokes many memories. “It’s funny because I see the same faces I used to hang out with here, so a lot of mischievous memories are coming back. It’s like, Do you remember the time? So, a lot of good times. A lot of times we probably shouldn’t of been having as young kids. But basically it’s just a lot of good memories and a lot of lessons learned right here on 24th.”

The three-mile parade is aptly launched at 24th and Burdette. There, Charles Hall’s now closed Fair Deal Cafe, once called “the black city hall,” provided a forum for community leaders to debate pressing issues and to map-out social action plans. Back in the day, Hall was known to give away food during the parade, which ends at Kountze Park, long a popular gathering spot in north Omaha. Across the street is Skeets, one of many soul food eateries in the area. Just down the road a piece is the Omaha Star, where legendary publisher Mildred Brown held court from the offices of her crusading black newspaper. Across the street is the Jewell Building, where James Jewell’s Dreamland Ballroom hosted black music greats from Armstrong to Basie to Ellington to Holiday, and a little further north, at 24th and Lake, is where hep cat juke joints like the M & M Lounge and McGill’s Blue Room made hay, hosting red hot jam sessions.

Recalling when, as one brother put it, “it was real,” is part and parcel of the Days. It’s all about “remembering how 24th and Lake was…the hot spot for the black community,” said Native Omahans Club member Ann Ventry. “We had everything out here,” added NOC member Vera Johnson, who along with Bettie McDonald is credited with forming the club and originating the festival. “We had cleaners, barber shops, beauty parlors, bakeries, grocery stores, ice cream stores, restaurants, theaters, clothing stores, taxi companies, doctors’ offices. You name it, we had it. We really didn’t have to go out of the neighborhood for anything,” Johnson said. Many businesses were black-owned, too. North O was, as lifelong resident Charles Carter describes it, “it’s own entity. That was the lifestyle.”

For James Wightman, a 1973 North High and 1978 UNL grad, the homecoming is more than a chance to rejoin old friends, it’s a matter of paying homage to a legacy. “Another reason we come back and go down 24th Street is to honor where we grew up. I grew up at the Omaha Boys Club and I played ball at the Bryant Center. There was so much to do down on the north side and your parents let you walk there. Kids can’t do that anymore.” Noting its rich history of jazz and athletics, Wightman alluded to some of the notables produced by north Omaha, including major league baseball Hall of Famer Bob Gibson, Heisman winner Johnny Rodgers, jazzman Preston Love, social activist Malcolm X, actor John Beasley and Radio One founder and CEO Catherine Liggins Hughes.

For Helen McMillan Caraway, an Omaha native living in Los Angeles, sauntering down 24th Street brings back memories of the music lessons she took from Florentine Kingston, whose apartment was above a bakery on the strip. “After my music lesson I’d go downstairs and get a brownie or something,” she said. “I had to steer clear of the other side of the street, where there was a bar called McGill’s that my father, Dr. Aaron McMillan, told me, ‘Don’t go near.’” Being in Omaha again makes the Central High graduate think of “the good times we used to have at Carter Lake and all the football games. I loved that. I had a good time growing up here.”

For native Omahan Terry Goodwin Miller, now residing in Dallas, being back on 24th Street or “out on the stem,” as natives refer to it, means remembering where she and her best girlfriend from Omaha, Jonice Houston Isom, also of Dallas, got their first hair cut. It was at the old Tuxedo Barbershop, whose nattily attired proprietors, Marcus “Mac” McGee and James Bailey, ran a tight ship in the street level shop they ran in the Jewell Building, right next to a pool hall and directly below the Dreamland. Being in Omaha means stopping at favorite haunts, like Time Out Foods, Joe Tess Place and Bronco’s or having a last drink at the now closed Backstreet Lounge. It means, Goodwin Miller said, “renewing friendships…and talking about our lives and seeing family.” It means dressing to the nines and flashing bling-bling at the big dance and, when it’s over, feeling like “we don’t want to go home and grabbing something to eat and coming back to 24th Street to sit around and wait for people to come by that we know.”

Goodwin Miller said the allure of renewing Omaha relationships is so strong that despite the fact she and Houston Isom live in Dallas now, “we don’t see each other there, but when we come here we’re together the whole time.”

Skeets’ David Deal knows the territory well. From his restaurant, which serves till 2 a.m., he sees native Omahans drawn, at all hours, to their old stomping grounds. He’s no different. “We’re just coming down here to have a good time and seeing people we haven’t seen in years.” Sometimes, it’s as simple as “sitting around and watching the cars go by, just like we used to back in the good old days.”

North Omaha. More than a geographic sector, it is the traditional, cultural heart of the local black community encompassing the social-historical reality of the African-American experience. Despite four decades of federally-mandated civil rights, equal opportunity, fair housing and affirmative action measures the black community here is still a largely separate, unequal minority in both economic and political terms and suffers a lingering perception problem — born out of racism — that unfairly paints the entire near northside as a crime and poverty-ridden ghetto. Pockets of despair do exist, but in fact north Omaha is a mostly stable area undergoing regentrification. There is the 24-square block Miami Heights housing-commercial development going up between 30th and 36th Streets and Miami and Lake Streets, near the new Salem Baptist Church. There is the now under construction North Omaha Love’s Jazz, Cultural Arts and Humanities Complex, named for Preston Love, on the northwest corner of 24th and Lake. The same sense of community infusing Native Omaha Days seems to be driving this latest surge of progress, which finds black professionals like attorney Brenda Council moving back to their roots.

Former NU football player James Wightman (1975-1978) has been coming back for the Days the past eight years, first from Seattle and now L.A., and he said, “I’m pretty pleased with what’s going on now in terms of the development. When I lived here there was a stampede of everybody getting out of Omaha because there weren’t as many opportunities. I look at Omaha’s growth and I see we’re a rich, thriving community now.” During the Days he stays, as many do, with family and hooks up with ex-jocks like Dennis Forrest (Central High) and Bobby Bass (Omaha Benson) to just kick it around. “We’re spread out in different locations now but we all come back and it’s like we never missed a beat.” The idea of a black pride week generating goodwill and dollars in the black community appeals to Wightman, who said, “I came to spend my money on the north side. And I’ll be back in two years.”

Wightman feels the Days can serve as a beacon of hope to today’s disenfranchised inner city youth. “I think it sends a message to the youth that there are good things happening. That people still come back because they feel a sense of family, friendship and connection that a lot of young people don’t have today. All my friends are in town for their school-family reunions and we all love each other. There’s none of this rival Bloods-Crips stuff. We talk about making a difference. It’s not just about a party, it’s a statement that we can all get along with each other.”

“It just shows there’s a lot of good around here,” said Omaha City Councilman Frank Brown, who represents largely black District 2, “but unfortunately it’s not told by the news media.” Scanning the jam-packed parade route, a beaming Brown said, “This is a four-hour event and there’s thousands of people of all ages here and they’re smiling and enjoying themselves and there’s no problems. When you walk around you see people hugging each other. There’s tears in some of their eyes because they haven’t seen their friends, who’ve become their family.”

Family is a recurring theme of the Days. “My family all lives here.” said John Welchen, a 1973 Tech High grad now living in Inglewood, Calif. For him, the event also “means family” in the larger sense. “To me, all of the friends I grew up with and everyone I’ve become acquainted with over the years is my extended family. It’s getting a chance to just see some great friends from the past and hear a lot of old stories and enjoy a lot of laughter.”

Native Omahans living in the rush-rush-rush of impersonal big cities look forward to getting back to the slower pace and gentler ways of the Midwest. “From the time I get off the plane here I notice a difference,” said Houston Odems, who flies into Omaha from Dallas. “People are polite…kind. To me, you just can’t beat it. I tell people all the time it’s a wonderful place to have grown-up. I mean, I still know the people who sold me my first car and the people who dry-cleaned my clothes.”

Although the Days traces its start back to 1977, when the Native Omahans Club threw the first event, celebrations commemorating the ties that bind black Omahans go back well before then. As a young girl in the ‘50s, Stapleton-Odems was a majorette in an Elks drill team that strutted their stuff during 24th Street parades. “It’s a gathering that’s been gong on since I can remember,” she said.

Old-timers say the first few Native Omaha Days featured more of a 24/7, open-air, street-party atmosphere. “We were out in the middle of the street all night long just enjoying each other,” said Billy Melton, a lifelong Omahan and self-styled authority on the north side. “There was live entertainment — bands playing — every six blocks. Guys set up tents in the parks to just get with liquor. After the dances let out people would go up and down the streets till six in the morning. Everybody dressed. Everybody looking like a star. It was a party town and we knew how to party. It was something to see. No crime…nothing. Oh, yeah…there was a time when we were like that, and I’m glad to have lived in that era.”

According to Melton, an original member of the Native Omahans Club, “some people would come a week early to start bar hopping. They didn’t wait for Native Omaha Days. If certain people didn’t come here, there was no party.”

Charles Carter is no old-timer, but he recalls the stroll down memory lane that was part of past fests. “They used to have a walk with a continuous stream of people on either side of the street. What they were doing was reenacting the old days when at nighttime 24th Street was alive. There were so many people you couldn’t find a place to walk, much less park. It was unbelievable. A lot of people are like me and hold onto the thought this is the way north Omaha was at one time and it’s unfortunate our children can’t see it because there’s so much rich history there.”

Then there was the huge bash Billy Melton and his wife Martha threw at their house. “It started early in the morning and lasted all night. It was quite a thing. Music, liquor, all kinds of food. It was a big affair,” Melton said. “I had my jukebox in the backyard and we’d have dancing on the basketball court. Endless conversations. That’s what it’s all about.”

Since the emergence of gang street violence in the mid-80s, observers like Melton and Carter say the fest is more subdued, with nighttime doings confined to formal, scheduled events like the gospel night at Salem and the dance at Mancuso Hall and the 24th Street rag relegated to the North Omahans Club or other indoor venues.

A reunion ultimately means saying goodbye, hence the close of the Days is dubbed Blue Monday. Most out-of-towners have left by then, but the few stalwarts that remain mix with die-hard residents for a final round or two at various drinking holes, toasting fat times together and getting high to make the parting less painful. After a week of carousing, out-of-town revelers wear their exhaustion like a badge of honor. “You’re supposed to be tired from all this,” Houston Isom said. “There’s no such thing as sleeping during this week. I can’t even take a nap because I’ll be worried I might be missing something.” Goodwin Miller builds in recovery time, saying, “When I go home I take a day off before I go back to work.” She and the others can’t wait to do it all over again two years from now.

Related articles

- Omaha Native Steve Marantz Looks Back at the City’s ’68 Racial Divide Through the Prism of Hoops in His New Book, ‘The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Where Hope Lives, Hope Center for Kids in North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Big Mama’s Keeps It Real, A Soul Food Sanctuary in Omaha: As Seen on ‘Diners, Drive-ins and Dives’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Community and Coffee at Omaha’s Perk Avenue Cafe (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Once More With Feeling, Loves Jazz & Arts Center Back from Hiatus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Get Crackin’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Rich Music History Long Untold is Revealed and Celebrated at the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Big Bad Buddy Miles (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- An Inner City Exhibition Tells a Wide Range of Stories (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Soon Come: Neville Murray’s Passion for the Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its Role in Rebirthing North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Soul on Ice – Man on Fire: The Charles Bryant Story (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness) (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Lifetime Friends, Native Sons, Entrepreneurs Michael Green and Dick Davis Lead Efforts to Revive North Omaha and to Empower its Black Citizenry (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

The Ties that Bind: One family’s celebration of Native Omaha Days

One of my favorite events to write about is something called Native Omaha Days, which is really a bunch of events over the course of a week or two in mid to late summer, held every two years and in essence serving as a great big celebration of Omaha‘s African American culture and heritage. There’s a public parade and picnic and a whole string of concerts, dances, and other activities, but at the root of it all is the dozens, perhaps hundreds of family and school reunions and various get togethers, large and small, that happen all over the city, but most especially in the traditional heart of the black community here – North Omaha. I’ve done a number of stories over the years about the Native Omaha Days itself or riffing off it to explore different aspects of Omaha’s black community. The story below for The Reader (www.thereader.comI is from a few years ago and focuses on one extended family’s celebration of The Days. as I like to refer to the event, via a reunion party they throw.

As the 2011 Native Omaha Days approaches (July 27-August 1) I am posting my stories about The Days over the past decade or so. You’ll also find on this blog a great array of other stories related to African American life in Omaha, past and present. Hope you enjoy.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The warm, communal homecoming known as Native Omaha Days expresses the deep ties that bind the city’s African-American community. It’s a time when natives long moved away return to roll with family and friends.

Beyond the cultural activities marking the festival, which officially concluded this week with the traditional “Blue Monday” farewells at northside watering holes, it’s an occasion when many families and high schools hold reunions. Whether visiting or residing here, it’s not unusual for someone to attend multiple public and private gatherings in the space of a week. The reunions embody the theme of reconnecting folks, separated by miles and years, that permeates The Days, whose activities began well before the prescribed Aug. 3 start and end well past the Aug. 8 close.

No singular experience can fully capture the flavor of this biennial love-in, but the Evergreen Family Reunion — a rendezvous of many families in one — comes close. Evergreen’s not the name of a people, but of the rural Alabama hamlet where families sharing a common origin/lineage, including the Nareds, Likelys, Olivers, Unions, Holts, Butlers, Turners and Ammons, can trace their roots.

For older kin reared there, Evergreen holds bitter memories as an inhospitable place for blacks. Those who got out, said Evergreen-born and Omaha-raised Richard Nared, were forced to leave. “Most of us came here because we had to,” he said. “A lot of my relatives had to leave the South in the middle of the night. I was little, but I did see some of the things we were confronted with, like the Ku Klux Klan.” The Nareds migrated north, as countless others did, to escape oppression and to find, as New York-raised Clinton Nared said, “a new freedom” and “a better life.”

Celebrating a fresh start and keeping track of an ever-expanding legacy is what compelled the family to start the reunion in the first place, said Rev. Robert Holt, who came in for the affair from California. The reunion can be traced to Moses Union and Georgia Ewing, who, in around 1928, “decided they would bring the family together so there would be no intermarriage. It started out with about 10 people and it grew. We’ve had as many as 2,000 attend. I don’t care where it is, I go.”

As Rev. Frank Likely of Gethsemane Church of God in Christ said in his invocation before the family fish fry on Friday, the reunion is, in part, a forum for discovering “family members we didn’t even know we had.” Then there’s “the chance to meet people I haven’t seen in 40 or 50 years,” said Rev. E.C. Oliver, pastor of Eden Baptist Church. “That’s what it means to me. A lot of them, I’ve wondered, ‘Were they still alive? What were they doing?’ It’s a good time for catching up and for fellowship,” said Oliver, who arrived from Evergreen without “a dime in my pocket.”

Clinton Nared‘s taken it upon himself to chart the family tree. Reunions, he said, reveal much. “Each year I come, I get more information and I meet people I never met before,” he said. “There’s so much history here.” Niece and fellow New Yorker Heather Nared said, “Every year I find out something different about the family.”

Of Richard Nared’s three daughters — Debra, Dina and Dawn — Dina’s been inspired to delve into the family’s past. “I needed to meet my people and to know our history,” she said. “I’ve been to more reunions than the rest of them. I even went to Evergreen. I thought it was beautiful. I loved the South. Before my oldest relatives died off, I got to sit and talk to them. It was fun. We had a good time.”

Over generations the family line spread, and offshoots can be found today across the U.S. and the world. But in the South, where some relatives remain, the multi-branched tree first sprouted in America. “We live all over. Now and then we come back together,” Richard Nared said. “But Evegreen’s where it all began. They used to call it Big Meeting.”

Gabrielle Union

Held variously in Detroit, Nashville, Evergreen and other locales, the reunion enjoys a run nearly rivaling that of the Bryant-Fisher clan, an old, noted area black family related by marriage to an Evergreen branch, the Unions, whose profile has increased due to the fame of one of its own, film/TV actress Gabrielle Union. A native Omahan hot off The Honeymooners remake and an Ebony cover and co-star of the upcoming ABC drama Night Stalker, she made the rounds at The Days and reunion, causing a stir wherever she went — “You seen Gabrielle? Is she here yet? We’re so proud of her.”

A display of how interconnected Omaha’s black community remains were the hundreds that greeted the star at Adams Park on Friday afternoon, when a public ceremony naming the park pond after her turned into — what else? — a reunion. Her mother, Theresa Union, said of the appreciative throng, “Most of these people, believe it or not, are her relatives, either on my side or on her father’s side. We are a very big part of North Omaha’s population.” Gabrielle’s father, Sylvester Union, said his famous daughter comes to the family galas for the same reason everyone does: “It’s a legacy we’re trying to keep going,” he said. “It’s an opportunity to communicate and share and stay in touch. To me, that’s what it’s about — bonding and rebonding.”

The actress wasn’t the only celebrity around, either. Pro football Hall of Famer Gale Sayers and Radio One founder Catherine Liggins Hughes were out and about, meeting and greeting, giving props to their hometown, family and fellow natives. This tight black community is small enough that Sayers and Hughes grew up with the Unions, the Nareds and many other families taking part. They were among a mix of current and former Omahans who gave it up for the good vibes and careers of 40 musicians inducted into the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame at an Aug. 4 banquet. The Days is all about paying homage to Omaha’s great black heritage. As Sayers said, “People in Chicago and different places I go ask me where I’m from and when I say, ‘Omaha, Neb.,’ they look at me like I’m crazy. ‘You mean there’s blacks in Omaha?’ I explain how there’s a very rich tradition of African-Americans here, how we helped develop the city, how there’s a lot of talent that’s come out of here, and how proud of the fact I am to be from Omaha, Neb.”

Gale Sayers

This outpouring of pride and affection links not only individual families, but an entire community. “Family ties is one of the most powerful things in black history. It runs deep with us,” Richard Nared said. During The Days, everyone is a brother and a sister. “We’re all one big family,” Omahan John Butler said.

Helping host the 2005 Evergreen affair were the Nareds, whose sprawling Pee Wee’s Palace daycare at 3650 Crown Point Avenue served as the reunion registration center and fish-fry/social-mixer site. Born in Evergreen with his two brothers, William and John, Richard Nared is patriarch of a family that’s a pillar in the local black community. The Nareds were instrumental in starting the Bryant Center, once Omaha’s premier outdoor basketball facility now enjoying a revival. Richard helped form and run the Midwest Striders track club. William was a cop. John, a rec center director. Richard’s sister-in-law, Bernice Nared, is Northwest High’s principal. Daughter-in-law Sherrie Nared is Douglas County’s HIV Prevention Specialist.

The Friday fry event broke the ice with help from the jamming funk band R-Style. Some 300 souls boogied the night away. “More than we expected,” Debra Nared said. About 50 folks were still living it up on the edge of dawn. As adults conversed, danced and played cards, kids tumbled on the playground.

The family made its presence known in the Native O parade the next morning with a mini-caravan consisting of a bus and two caddies, adorned with banners flying the family colors. T-shirts proclaimed the family’s Evergreen roots. A soul-food picnic that afternoon at Fontenelle Park offered more chances for fellowship. Gabrielle and her entourage showed up to press the flesh and partake in ribs, beans, potato salad and peach cobbler. She posed for pictures with aunties, uncles, cousins. A weekend limo tour showed out-of-towners the sights. A coterie of relatives strutted their stuff at the big dance at Omaha’s Qwest Center that night. A Sunday church service and dinner at Pilgrim’s Baptist, whose founders were family members from Evergreen, brought the story full circle.

Heard repeatedly during the reunion: “Hey, cuz, how ya’ doin’?” and “You my cuz, too?” and “Is that my cuz over there?”

Annette Nared said, “There’s a lot of people here I don’t know, but by the time the night’s over, I’ll meet a whole lot of new relatives.” Looking around at all the family surrounding her, wide-eyed Dawn Nared said, “I didn’t know I had this many cousins. It’s interesting.” Omahan Sharon Turner, who married into the family, summed up the weekend by saying, it’s “lots of camaraderie. It’s a real good time to reconnect and find out what other folks are doing.”

For Richard Nared, it’s all about continuity. “Young people don’t know the family tree. They don’t know their family history unless someone old enlightens them,” he said. “Kids need to know about their history. If they don’t know their history, they’re lost anyway.”

It’s why he called out a challenge to the young bloods to keep it going. “This is a family affair,” he said. “I want the young people here to carry things on. Let’s come together. Let’s make this something special from now on.”

Related articles

- Big Mama’s Keeps It Real, A Soul Food Sanctuary in Omaha: As Seen on ‘Diners, Drive-ins and Dives’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Where Hope Lives, Hope Center for Kids in North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Native Steve Marantz Looks Back at the City’s ’68 Racial Divide Through the Prism of Hoops in His New Book, ‘The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Get Crackin’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Rich Music History Long Untold is Revealed and Celebrated at the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- An Inner City Exhibition Tells a Wide Range of Stories (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Miss Leola Says Goodbye (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Soul on Ice – Man on Fire: The Charles Bryant Story (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness) (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Art as Revolution: Brigitte McQueen’s Union for Contemporary Art Reimagines What’s Possible in North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Soon Come: Neville Murray’s Passion for the Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its Role in Rebirthing North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Polishing Gem: Behind the scenes of John Beasley Theater & Workshop’s staging of August Wilson’s “Gem of the Ocean”

My concept for the following story I did for The Reader (www.thereader.como) was deceptively simple – embed myself with a community theater group as they rehearsed and mounted a play over the course of several weeks. Practical realities dictated that I be there off and on, for a few hours there or few minutes here, in observing and reporting the experience, but I think I managed a compelling behind the scenes glimpse at some of what goes into the development of a theater production from first table reading to opening night. My theater of choice was the John Beasley Theater & Workshop in Omaha. The theater’s namesake, John Beasley, is a fine stage, film, and television actor and his small theater is a good showcase for African American-themed stagework, particularly the work of August Wilson. And it was a Wilson play, Gem of the Ocean, that the theater prepared and performed during my time covering the company. On this blog you’ll find more of my stories about John Beasley and his theater, including many more pieces related to other Omaha theaters and theater figures, as well as authors, artists, musicians, filmmakers. I am posting lots of of my theater stories now to coincide with the May 28-June 4 Great Plains Theatre Conference, and you’ll find several of my stories about that event and some of its leading participants.

Polishing Gem: Behind the scenes of John Beasley Theater & Workshop’s staging of August Wilson’s “Gem of the Ocean “

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Mounting a production has its own dynamic. Discoveries happen incrementally over weeks. This creative process occurs not before a paid house but among a theater family in the privileged moments of readings-rehearsals.

It means late nights, running lines, working scenes. Over and over. Until truth emerges. Developing a play is by turns grueling, moving, satisfying. It’s all about exposing and confronting your fears — in service of emotionally honest expression.

It’s not all inspiration. More like a grind. Adrenalin feeds anxiety. Caffeine fights exhaustion. An edge cuts the air. Making a fool of yourself is a distinct possibility. Doubts creep in. Anticipation awaits resolution. Tension seeks release.

The process unfolds hundreds of times each theater season. In big state-of-the-art facilities, in intimate black box spaces, in church basements. Fully realized performances spring from coaching, encouragement, cajoling, berating, freaking, experimentation, work and prayer.

Over several nights at the John Beasley Theater & Workshop a fly on the wall observed this company developing their production of August Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean. The two-act drama is part of Wilson’s 10-play cycle chronicling the African-American experience. The JBT’s produced seven works in the cycle. Set amidst 1904 Pittsburgh’s Hill District, Gem’s a story of redemption.

Like most community theaters the JBT uses largely unpaid, untrained people who fit the work around busy lives-careers. There’s scant time to get things right. Much can go wrong. Chronic tardiness, family crises. Recasting a major part 10 days before opening. As a veteran JBT actor put it, “It seems there’s always something but in the end it all comes together.” Until opening night, the process, not the play, is the thing. In classic show-must-go-on tradition the troupe pulled Gem off. Getting there was heaven and hell.

Jan. 7 – “It’s a lot of work”

The first reading convenes. It’s like Bible study. Actors explore the sacred text — the script — under director Tyrone Beasley’s sober guidance. Hallejuah!

John Beasley, journeyman film-TV-stage character actor, headlines as Solly Two Kings, a loquacious drifter and former underground railroad conductor-turned- pure (dog manure) merchant. John arrives late, brimming with excitement about a new gig — acting in an August Wilson festival at the Kennedy Center in D.C.

Joining him in Gem are three regular JBT ensemble players. Retired electrician Charles Galloway is Eli, gatekeeper for Aunt Ester, a sage and spiritual adviser. Eli, also an ex-freedom fighter, is Solly’s best bud.

Andre McGraw, owner of Red Hot Barbershop, is Citizen Barlow, a fugitive come far to get his soul washed by Ester. Carl Brooks, Union Pacific systems analyst, is Caesar, a big, belligerent cop enforcing the white man’s law. Carl has an excused absence tonight. Ty reads his part.

JBT newcomers fill out the cast. Lovely Lakeisha Cox, grad student, plays Black Mary, Caesar’s sister and Ester’s successor-in-grooming. Tom Pensabene, dean of information technology and e-learning at Metropolitan Community College, debuts as Selig, slave finder-turned-slave runner-turned-peddler. Enigmatic Yvette Coleman is Ester. She’s a no-show. Stage manager Cheryl Bowles reads her part.

Everyone’s seated around a wooden table on the bare stage. The auditorium floor is stripped to the studs, awaiting new carpet-seats. Cast-crew wear street clothes. Introductions are made. When it comes his turn Andre jokes, “I’m born and raised in the John Beasley Theater.” Its namesake discusses the play’s musical language.

“It’s tough at first picking up the rhythm August writes in. I think August gives you enough that you won’t have to try to force it. It’ll be there.”

John commands respect. It’s he, as much as Ty, the ranks look to please.

Ty shares a JBT philosophy:

“We believe acting is behaving truthfully in imaginary circumstances. Being yourself is the first thing we’re looking for. Being in the moment. Being present.”

He suggests the players use personal experiences to make their characters extensions of themselves. “Be as specific as possible.” All to better ground one in the reality of the situation. That’s what “brings a character to life.”

He assigns homework. Actors are to flesh out character objectives, backgrounds and relationships, plus research facets of early Pittsburgh.

Ty impresses upon the cast what’s expected. “It’s a lot of work. It’s important to be here on time. It’s a long play and there’s relatively little time to do it in. If you’re here, you should always be working.”

“Let’s get started.”

The reading, opened scripts in hand, proceeds. Even dry, the drama’s inherent power is felt. In-character John tests Lakeisha by making direct eye contact with her. She rises to the occasion, By reading’s end the energy lags and lines suffer. John officially welcomes newbies Keisha and Tom with hugs and handshakes. He and Ty discuss a Plan B should their Ester prove unreliable.

Jan. 8 – “We’ll turn Omaha on its head”

Before rehearsal John covers a pivotal Act II scene with Andre. Ester puts Citizen in a trance that transports him to the City of Bones. Citizen imagines himself in a boat at sea. John says Andre must visualize it.

John Beasley

“You’re going to have to take us to the City of Bones. We see it through your eyes. If you do this right, we’ll turn Omaha on its head –and we’re going to do it right.”

Citizen’s killed a man and the death of another haunts him. He needs to make himself right with the Lord. His inward journey to be justified drives the story.

This night’s about working the prologue, when the agitated Citizen appears at Ester’s house demanding his soul be washed. There’s many takes of a tussle he has with Eli (Charles). The commotion awakens Ester, whose serene bearing calms Citizen. The movements, pacing, blocking require much attention.

“Take it again,” Ty repeats. “Good work,” he says after another.

Our missing Ester’s here. Yvette strains finding the right beat. Ty wants her moving slowly, not feebly. Exuding an aura. He contextualizes Ester in the Wilson canon.

“Aunt Ester is someone that’s talked about in several of August Wilson’s plays. She’s a powerful, spiritual woman and her power comes from her faith. This is the first time she’s seen…People are anticipating her, so when you come out there has to be a powerful, spiritual presence.”

After false starts, Yvette hits her stride.

For the reading actors have underlined or highlighted their lines in their scripts.

Ty demands more from his players. “What I want you guys to do is look each other in the eye as you’re saying your lines. Try to lift the words off the page and really talk to the person…Really communicate. Really work on seeing the images.”

“Let’s take it from the top.”

He looks and listens hard as they work. Cheryl gives stage directions, feeding lines as needed. Ty has comments for everyone. Keisha needs to find Mary’s stubbornness, Charles must avoid indicating his actions, et cetera.

“Good, that’s better, let’s do it again,” Ty says. After a bit he declares, “OK, good, let’s get this on its feet.”

Before walking through the scene he takes Keisha aside, reminding her the words she speaks must be anchored in thoughts-images.

Minimal props are introduced. Blocking addressed. The scene plays disjointed, stilted, lifeless. Ty has actors try different things. “See how that feels,” he says.

Jan. 10 – “Let the words do it”

Scene one pits Solly and Mary in a dispute over the pure he peddles. Ty’s been on Keisha to be ornery: “Black Mary has an attitude.” Keisha shoots back, “You want some real attitude? Put some real pure in there.” Laughter.

The action’s fuller, tighter than two nights ago. When Ester enters she asks Mary for the pure. Yvette, realizing what Ester’s supposed to examine, asks, “So that’s what I’m looking at? Is it real dog poop?” She’s teased. “It’s going to be dry. All you gotta do is break it up,” John quips, trading smirks with Ty. They begin again, but Yvette’s still thrown by the doo-doo.

While not the director per se John freely instructs, careful not to overstep Ty’s bounds. John goes over movements with Charles, who, as Eli, responds to loud knocking at Ester’s door. “The urgency will determine how fast you walk,” John says. He shows him. “Does that make sense?”

“OK, let’s sit at the table,” Ty says. All the principals gather round. They read scene three. It flows well. The intensity builds. The volume so high John gestures for them to tamp it down. Carl’s feeling Caesar. In a long speech his bellowing voice rises in anger. After he’s done John comments, “You don’t really have to be that forceful. You’re a big man. It’s all there in the words. Let the words do it.” Carl says, “Yeah, I don’t have to make him a caricature.”

“OK, top of the scene,” Ty says. They read it again. Carl’s quieter yet still formidable. John can be overpowering, too. It’s why he works hard “to bring everybody up to my level of energy.”

John confers with Andre, who’s concerned about finding the right note for Citizen. “He’s a full man. He’s carrying that burden with him,” John says. “You working it. Don’t be afraid to try anything because Tyrone will pull you back.”

Jan. 14 – “Being here, being now”

John helps Keisha modulate her delivery. Her thin voice pitches up to make statements into questions. “Try it again,” he says. “Down on the inflection. Keep going…One more time…Better.” “I’ll work on it” she promises.

The Gem set, which Tyrone builds by day, is more filled out. It’s basically a kitchen, dining room, parlor and staircase.

Ty and John discuss replacing Yvette. She’s missed rehearsals. She’s late for this one. “If she’s not here tonight,” John says, “then that’s it.”

John puts the cast through warm ups. “Get yourself loose. Focus on the breath. Slowly breath in and slowly breath out. It relaxes you. It keeps you focused in the moment and that’s what we need. Being here, being now.”

“One of the worst enemies of an actor is tension,” Ty says. He works with Keisha on a yoga position. He’s cast her and the others for qualities they share with their characters. Expressing that means letting go. “She has the power of Black Mary, but she’s shy to let it out on stage.”

Yvette finally arrives. She flounders with her lines.

John and Ty work with the actors on their characters’ motivations.

Jan. 15 – “It’s gotta be in your voice”

Yvette and John work one-on-one. He presses her to make it real.

“You don’t believe me?” she asks him. “Talk to me,” he says. “Make me hear it. Make me hear what you have to say. It’s gotta be in your voice because I don’t believe those other voices.” She tries again. “There it is. Did you feel the difference?”

Jan. 18 – “I want to get my soul washed”

The set’s now dressed with furniture-fixtures. The stage speckled with paint and sawdust. Ladders lean against walls, electrical cord snakes across the floor.

Per usual Carl’s arrived early to work his lines. He studies at a chair in the lobby. Others find sanctuary in the overstuffed theater tech booth or back stage amid the flats, costumes and props or in the cramped wings. Tonight, Carl and Keisha animatedly share the back stories they’ve concocted.

As actors straggle in, they run lines, scrounge for eats or just kick it. Charles is distracted. His Navy Lt. Commander son has gotten orders for Iraq.

Ty asks Andre why, as Citizen, he’s timid with Ester. “I’m feeling her out. I’m kind of like hesitant because I don’t know her. I’ve got this picture of her that’s she’s a scary looking lady,” he explains. “No, she’s not,” Ty says. “Why are you in her house?” “Because I want to get my soul washed.”

“Just remember you know that she’s the reason you’re there.”

“Lights up.”

Jan. 25 – “Come take the circle”

Nitty-gritty time. The Beasleys grow more direct. Ty announces, “Come take the circle,” a cue for players to form a tight circle in chairs. “Remember the exercise,” he says. Working in close quarters the actors call each other out on whatever rings false. Ty makes sure no one gets away with anything. In this intimate, in-your-face interaction there’s no where to hide. The extreme scrutiny bares all. It’s a living tableaux of pure concentration and naked emotion.

“I don’t believe you,” Ty tells Keisha, who’s plays opposite Carl. “Do you believe her?” he asks Carl, who nods no. “Then why are you letting her go?” “I’m just asking you to believe what you’re saying,” Ty tells all. Keisha goes again, but stops in frustration, saying, “I didn’t feel it.” Ty chastises her for breaking character.

Keisha’s under extra strain these days as her mother and aunt battle illnesses. She says the play provides a needed vehicle to channel her feelings.

Yvette’s AWOL again. And so it goes…

Jan. 29 – “We’ve all got to be in this”

There’s a new Ester. JBT favorite TammyRa Jackson has replaced Yvette with the opening less than two weeks off. A cosmetologist and mother of five, she concedes she’s anxious joining the cast so late but is warmed by how supported she’s made to feel. John won’t push back the run — not with the house sold out opening night. Besides, he’s confident his new Ester will “put the work in.”

“We brought TammyRa in because we felt she was the only that could do this in this short of time. She’s a tremendous talent. As she commits the words she’s bringing a lot of new stuff to the table, which I figured she would.”

Fresh carpet’s been laid down. A noxious chemical smell permeates the auditorium.

With “C’mon y’all” John beckons cast to work the crucial City of Bones scene at the table. The scene’s not jelled. The time’s short, the stakes high, the nerves raw. Music director Leon Adams hovers over the group to consult on song verses.

“We need to find this thing,” John tells the pensive cast, “so I need you to do as much work as you can.”

They begin. “Feel it, feel it,” he says. “See the stars, Andre,” who rocks in Citizen’s trance. TammyRa’s spot-on with the sing-song spell that puts Citizen under. John and Charles take up the chant. When Keisha and Cheryl speak out of character the chant’s broken, making John upset.

“Wait a minute, what’s going on there? Don’t talk during the exercise. You’ve got to stay in this, Keisha. We’ve all got to be in this. This is a very difficult scene. You’ve got to stay focused…This is a chant, and if you focus in on this you can feel a rhythm come up…If you find that, we’ll be half-way home.”

She’s taken aback. He holds her hand to show he’s not mad.

Next he turns to Andre to say he’s unconvinced by Citizen’s born-again epiphany.

“You’re still acting, Andre. You’re not there yet. You gotta go deeper, man. You gotta believe it. Just like in any ritual, any spiritual thing, you gotta be listening and open…in order for it to really take over, and I think you’ll find it in the rhythm. You’ll feel it. You’ll hook up into it.”

They take it again and again. Leo advises more “embellishment” here, more “swung” there. John reminds TammyRa to “keep the contemporary” out of her voice. She asks lots of questions. A good sign. Her young daughter Nadia hangs by her side as she guides Citizen on his way. John’s pleased after another take. “Just paint those beautiful pictures with those beautiful words. That’s nice, nice work.” He wants TammyRa to do more with the title line and cautions Keisha “not to throw away” a strong line about Satan.

A work in progress.

Feb. 6 – “I think we’ll be ready for Friday”

It’s tech week and 48 hours until show time. The stress shows on people’s faces. The tense actors get costumed.

The seats are in. So are Ty’s notes from the staged run through two nights before.

The company lost yesterday to a snowstorm. “I was confident enough to give them that time to study their script and do their work,” John tells a visitor. “They’re finding their characters. We’ve come a long ways. I think we’ll be ready for Friday.”

A key player’s missing, however. Carl’s father died a few days earlier and he’s still in his native St. Louis for the services. Ty’s assumes the role tonight and may open in it Friday. He’s told Carl to take as much time as he needs.

As cast filter in crew clean up the freshly painted set.

“Actors to the stage please,” Ty says. They gather round and he reads aloud their notes — hand-written critiques, refinements. As is his penchant he works from general to specific. He directs packing Caesar’s gun in a waist holster.

“Overall, it was low energy…The audience is not going to be feeling the show. So keep your energy up everybody.”

His individual notes cover stage positions, cues, intonations, intentions. He demonstrates various actions. His most telling comments concern Andre. “If you don’t have that urgency of why you’re there…then it’s a tough show.”

Before the run-through John reiterates “it’s important we keep up the energy. Just keep the story moving along…”

They work late into the night. No preview tomorrow. Another rehearsal. Then it’s on with the show the next night.

Feb. 8 – “It’s finally here”

Opening night.

6:30. An hour to curtain and jitters abound. On stage John runs lines with Carl, who got back last night. John presses him to emphasize each subject. Ty, unhappy the way Carl handles a speech to win over Mary, gets up in his face with, “You got to try to get her on your side. That’s what you’re trying to do here.” “Let me start over,” Carl says. He nails it. “Good, good,” John says.

Carl, hours removed from his dad’s funeral, never considered not performing. He says the play’s “a pretty good distraction.” He frets having “missed some valuable time” but is risking it anyway. “Something’s going to happen — stick around.”

John, wife Judy, Ty, Cheryl and production staff scurry to place props. Tom and Charles, already costumed, work lines backstage. The other actors get made up and change in the dressing room.

Past 7 the lobby fills with patrons. “We’re getting ready to open the house,” John announces. “Hold on, man, I need two minutes,” says Mark O’Leary, who hangs a picture and touches up a faucet. “You got it.”

Andre runs over lines to himself in the wings, pacing in a circle. He and Keisha share a tender moment. “A lot of different emotions,” Keisha says. “It’s finally here, so no matter what you’ve just got to go out there and have fun at this point.”

As insurance, TammyRa’s wearing an earpiece that Cheryl will feed lines into.

The house opens and folks stream in, unaware of the activity on set moments before and the beehive backstage.

Cast members squeeze into the small dressing room. They flit in and out. John, bandana wrapped around his head and big ass walking stick held in his hand, offers final notes to Charles and Keisha. There’s the usual “break-a-leg” well-wishes.

“What’s our time like?” Charles asks. “Not much — like five minutes,” says John, who asks Cheryl to round up the others. All the players cram inside. They clasp hands as Cheryl leads a fervent prayer. She refers to how “we’ve come up against everything” on this show. “We thank you God for this time we’ve been able to work together and join hearts and become friends and even family. We thank you for John Beasley and all of his hard work…He struggles to keep this going…but he hangs in there because he believes in us. He could walk away, but he doesn’t.”

“We pray you God that you will give us victory. Amen.”

A chorus of Amens goes up. John cracks, “Anybody got a collection plate here?”