Archive

Coloring History: A long, hard road for UNO Black Studies

If you’re surprised that Omaha, Neb. boasts a sizable African-American community with a rich legacy of achievement, then you will no doubt be surprised to learn the University of Nebraska at Omaha formed one of the nation’s first Black Studies departments. The UNO Department of Black Studies has operated continuously for more than 40 years. The following story I did for The Reader (www.thereader.com) charts the long, hard path that led to the department‘s founding and that’s provided many twists and turns on the road to institutional acceptance and stability. At the time I wrote this piece and that it appeared in print, the UNO Department of Black Studies was in an uneasy transition period. Since then, things have stabilized under new leadership at the university and within the department.

Coloring History: A long, hard road for UNO Black Studies

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

When 54 black students staged a sit-in on Monday, Nov. 10, 1969 at the office of University of Nebraska at Omaha’s then-president Kirk Naylor, they meant their actions to spur change at a school where blacks had little voice. Change came with the start of the UNO department of black studies in 1971-72. A 35th anniversary celebration in April 2007 featured a dramatic re-enactment of the ’69 events that set the eventual development of UNO’s black studies department in motion.

Led by Black Liberators for Action on Campus (BLAC), the protesters occupied Naylor’s administration building suite when he refused to act on their demands. The group focused on black identity, pride and awareness. When they were escorted out by police, the demonstrators showed their defiant solidarity by raising their fists overhead and singing “We Shall Overcome,” which was then echoed by white and black student sympathizers alike.

The group’s demands included a black studies program. UNO, like many universities at the time, offered only one black history course. Amid the free speech and antiwar protests on campuses were calls for equal rights and inclusion for blacks.

Ron Estes, who was one of the sit-in participants in 1969, said, “We knew of the marches and sit-ins where people stood up for their rights, and we decided to make the same stand.” Joining Estes on that Monday almost 40 years ago was Michael Maroney who agreed, “We finally woke up and realized there was something wrong with this university and if we didn’t take action it wasn’t going to change.”

Well-known Omaha photojournalist Rudy Smith, who was then a student senator said, “We approached it from different perspectives, but the black students at the time were unified on a goal. We knew what the struggle was like, and we were prepared to struggle.”

The same unrest that was disrupting schools on the coasts, including clashes between students and authorities, never turned violent at UNO. The sit-in, and a march three days earlier, unfolded peacefully. Even the arrests went smoothly. Also proceeding without incident was a 1967 “teach-in”; Ernie Chambers, who was not yet a state senator but who was becoming a prominent leader in the community, and a group of students demonstrated by trying to teach the importance of black history to the administration, specifically the head of the history department.

The sit-in’s apparent failure turned victory when the jailed students were dubbed “the Omaha 54” and the community rallied to their cause. Media coverage put the issues addressed by their demands in the news. Black community leaders like Chambers, Charles Washington, Rodney Wead and Bertha Calloway continued to put pressure on the administration to act. Officials at the school, which had recently joined the University of Nebraska system, felt compelled to consider adding a formal black studies component. From UNO’s point-of-view, a black studies program only made sense in an urban community with tens of thousands African-Americans.

Rudy Smith

Within weeks of the sit-in and throughout the next couple of years, student-faculty committees were convened, studies were conducted, and proposals and resolutions were advanced. Despite resistance from entrenched old white quarters, support was widespread on campus in 1969-70. Once a consensus was reached, discussion centered on whether to form a program or a department.

The student-faculty senates came out in favor of it, as did the College of Arts and Sciences Dean Vic Blackwell, a key sympathizer. Even Naylor; he actually initiated the Black Studies Action Committee chaired by political science professor Orville Menard that approved creating the department. Much community input went into the deliberations. The University of Nebraska board of regents sealed the deal.

No one is sure of the impact that the Omaha 54 made, but they did spur change. UNO soon got new leadership at the top, a black studies department and more minority faculty. Its athletic teams dropped the “Indians” mascot/name. A women’s studies program, multicultural office and strategic diversity mission also came to pass.

“I think we helped the university change,” Maroney said. “I think we gave it that impetus to move this agenda forward.”

Before 1971, federally funded schools were not requireed to report ethnicity enrollment numbers. In 1972, 595 students, or about 4.7 percent of UNO’s 12,762 total students, were black. In 2006, 758, or about 5.2 percent of the school’s 14,693 total students were black.

Omaha 54 member and current UNO associate professor in the Department of Educational Administration and Supervision Karen Hayes said, “We were the pebble that went in the pond, and the ripples continued through the years for hopefully positive growth.”

During that formative process, the husband-wife team of Melvin and Margaret Wade were recruited to UNO in 1970 from the University of California at Santa Barbara’s black studies department. Wade came as acting director of what was still only an “on-paper black studies program.” His role was to help UNO gauge where interest and support lay and formulate a plan for what a department should look like. He said he and Margaret, now his ex-wife, did some 200 interviews with faculty, staff and students.

Speaking by phone from Rhode Island, Wade said the administration favored a program over a department, but advocacy fact-finding efforts turned the tide. That debate resurfaced in the 1980s in the wake of proposed budget cuts targeting black studies. In en era of tightened higher education budgets, according to then-department chair Julien Lafontant and retiring department associate professor Daniel Boamah-Wiafe, black studies seemed always singled out for cutbacks.

“Every year, the same problem,” Lafontant said. That’s when Lafontant did the unthinkable — he proposed his own department be downgraded to a program . Called a Judas and worse, he defended his position, saying a program would be insulated from future cuts whereas a department would remain exposed and, thus, vulnerable. A native of Haiti, Lafontant found himself in a losing battle with the politics of ethnicity that dictate “a black foreigner” cannot have the same appreciation of the black experience here as an African-American who is born in the United States.

Turmoil was not new to the department. Its first two leaders, Melvin Wade and Milton White, had brief tenures ending in disputes with administrators.

In times of crisis, the black community’s had the department’s back. Ex-Omahan A. B. “Buddy” Hogan, who rallied grassroots support in the ’80s, said from his home in California that rescues would be unnecessary if UNO had more than “paternalistic tolerance” of black studies.

“I don’t think the university ever really embraced the black studies department as a viable part,” Maroney said. “It was more a nuisance to them. But when they tried to get rid of it, the black community rose up and so it was just easier to keep it. I don’t think it’s ever had the kind of funding it really needs to be all it could be.”

UNO black studies Interim Chair Richard Breaux said given the historically tenuous hold of the department, perhaps it’s time to consider a School of Ethnic Studies at the university that includes black studies, Latino studies, etc.

Still Fighting

In recent interviews with persons close to the department, past and present, The Reader found: general distrust of the university’s commitment to black studies, despite administration proclamations that the school is fully invested in it; the perception that black studies is no more secure now than at its start; and the belief that its growth is hampered by being in a constant mode of survival.

After 35 years, the department should be, in the words of Boamah-Wiafe, “much stronger, much more consolidated than it is now.”

Years of constant struggle is debilitating. Lafontant, who still teaches a black studies course, said, “Being in a constant struggle to survive can eliminate so many things. You don’t have time to sit down and see what you need to do. Even now it’s the same thing. It’s still fighting. They have to put a stop to that and find a way to help the black studies department to not be so on guard all the time.”

Is there cause to celebrate a department that’s survived more than thrived?

“I think the fact it has endured for 35 years is itself a triumph of the teachers, the students, certainly the black community and to a certain extent elements of the university,” former UNO black studies Chair Robert Chrisman said by phone from Oakland, Calif. However he questions UNO’s commitment to black studies in an era when the school’s historic urban mission seems more suburban-focused, looking to populations and communities west of Omaha, and less focused on the urban community and its needs closer to home. It wasn’t until 1990 that UNO made black studies a core education requirement. College of Arts and Sciences Dean Shelton Hendricks has reiterated UNO’s commitment to black studies, but to critics it sounds like lip service.

Chrisman’s call for black studies in his prestigious Black Scholar journal in the late ’60s inspired UNO student activists, such as Rudy Smith, to mobilize for it. Smith said the department’s mere presence is “a living symbol of progress and hope.”

For Chrisman the endurance of black studies is tempered by “the fact the United States is governed by two major ideological forces. One is corporate capitalism and the other is racism, and that’s run through all of the nation’s institutions … . Now we tend to think colleges and universities are somehow exempt from these two forces, but they’re not … Colleges and universities are a manifestation of racism and corporatism and in some cases they’re training grounds for it.”

Robert Chrisman

He said the uncomfortable truth is that the “primary mission of black studies is to rectify the dominant corporate and racist values of the society in the university itself. You see a contradiction don’t you? And I think that’s one of the reasons why the resistance is so reflexive and so deeply ingrained.”

Smith said the movement for the discipline played out during “a time frame when if blacks were going to achieve anything they had to take the initiative and force the issue. Black studies is an outgrowth of the civil rights movement.”

Along these lines, Chrisman said, small college departments centered around western European thought, such as the classics, “are protected and maintained” in contrast with black studies. He said one must never forget black studies programs/departments arose out of agitation. “Almost all of them were instituted by one form of coercion or another. There was the strike at San Francisco State, the UNO demonstration, the siege at Cornell University, on and on. In the first four years of the black studies movement, something like 200 student strikes or incidents occurred on campuses, so the black studies movement was not welcomed with open arms … . It came in, in most instances, against resistance.”

In this light, Hogan said, “there’s a natural human tendency to oppose things imposed upon you. It’s understandable there’s been this opposition, but at some point you would have thought there would have been enough intellectual enlightenment for the administration to figure out this is a positive resource for this university, for this community and it should be supported.”

Organizing Studies

The program versus department argument is important given the racial-social-political dynamic from which black studies sprang. Boamah-Wiafe said opponents look upon the discipline “as something that doesn’t belong to academia.” Thus any attempt to restrict or reduce black studies is an ugly reminder of the onerous second-class status blacks have historically endured in America.

As Wade explained, “A program really means you have a kind of second-class status, and a department means you have the prerogative to propose the hire of faculty who are experts in black studies. In a department, theoretically, you have the power to award tenure. With a program, you generally have to have faculty housed in other departments, so faculty’s principal allegiances would be to those departments. So if you have a program, you are in many respects a step-child — always in subservience to those departments … ”

Then there’s the prestige that attends a department. That’s why any hint of messing with the department, whose 2006/2007 budget totaled $389,730, smacks some as racism and draws the ire of community watchdogs. When in 1984 Lafontant and then-UNO Chancellor Del Weber pushed the program option, Breaux said, “There was tremendous outcry from people like Charlie Washington [the late Omaha activist] and Buddy Hogan [who headed the local NAACP chapter]. They really came to bat for the department of black studies. A lot of people, like Michael Maroney — who were part of that Omaha 54 group that got arrested — said, ‘Now wait a minute, we didn’t do this for nothing.’” The issue went all the way to the board of regents, who by one vote preserved the department.

As recently as 2002, then-NAACP local chapter president Rev. Everett Reynolds sensed the university was retreating from its stated commitment to black studies. He took his concerns to then-chancellor Nancy Belck. In a joint press conference, she proclaimed UNO’s support for the department and he expressed satisfaction with her guarantees to keep it on solid footing. She promised UNO would maintain five full-time faculty members in black studies. Breaux said only three of those lines are filled. A fourth is filled by a special faculty development person. Breaux said black studies has fewer full-time faculty today than 30 years ago.

“So you ask me about progress and my answer is … not much. We’re talking 30 years, and there’s not really been an increase in faculty or faculty lines,” Breaux said.

Hendricks said he’s working on filling all five full-time faculty lines.

Sources say the department’s chronically small enrollment and few majors contribute to difficulty hiring/retaining faculty in a highly competitive marketplace and to the close scrutiny the department receives whenever talk of cutting funds surfaces.

Wade said black studies at UNO is hardly alone in its plight. He said the move to reduce the status of black studies on other campuses has led to cuts. “It has happened in enough cases to be noted,” Wade said. “I was affiliated with the black studies program at Vassar College, and that’s one whose status has been diminished over the years … . In other words, the struggle for black studies is being waged as we speak. It’s still not on the secure foundations it should be in the United States.”

Some observers say black studies must navigate a corporate-modeled university culture predisposed to oppose it. “That means at every level there’s always bargaining, conniving, chiseling, pressuring to get your goals. Every year the money is deposited in a pot to colleges, and it’s at the dean’s discretion … where and how the money’s distributed,” Chrisman said. Robbing-Peter-to-pay-Paul machinations are endemic to academia, and critics will tell you black studies is on the short end of funding shell games that take from it to give to other units.

Chrisman feels an over-reliance on part-time, adjunct faculty impedes developing “a core to your department.” At UNO he questions why the College of Arts and Sciences has not devoted resources to secure more full-time faculty as a way to solidify and advance the program. It’s this kind of ad hoc approach that makes him feel “the administration really doesn’t quite respect the black experience totally.” He said it strikes him as a type of “getting-it-as-cheap-as-possible” shortcut. Hendricks said he believes the ratio of part-time to full-time faculty in the department is comparable to that in other departments in UNO’s College of Arts and Sciences. He also said part-time, adjunct faculty drawn from the community help fulfill the strong black studies mission to be anchored there.

Breaux’s successor as Interim UNO black studies chair, Peggy Jones, is a tenured track associate professor. Her specialty is not black studies but fine arts.

Boamah-Wiafe feels with the departures of Breaux and himself the department “will be the weakest, in terms of faculty” it has been in his 30 years there.

The Struggle Continues

Critics say UNO’s black studies can be a strong academic unit with the right support. The night of the Omaha 54 reenactment Michael Maroney, president/CEO of the Omaha Economic Development Corporation, made a plea for “greater collaboration and communication” between Omaha’s black community and the black studies department. “It’s a two-way street,” he said. Omaha photojournalist Rudy Smith said the incoming chair must work “proactively” with the community.

Chrisman, too, sees a need for partnering. He noted while the black community may lack large corporate players, “you can have an organized community board which helps make the same kind of influence. With that board, the black studies chair and teachers can work to really project plans and curriculum and articulate the needs of black people in that community. It’s one thing for a single teacher or a chair to pound on the dean’s door and say, ‘I need this,’ but if an entire community says to the chancellor, ‘This is what we perceive we need as a people,’ I think you have more pressure.

“That would be an important thing to institute as one of the continuing missions of black studies is direct community service because there’s so much need in the community. And I think black studies chairs can take the initiative on that.”

He said recent media reports about the extreme poverty levels among Omaha’s African-American populace “should have been a black studies project.”

Breaux said little if any serious scholarship has come out of the department on the state of black Omaha, not even on the city’s much-debated school-funding issue. Maroney sees the department as a source of “tremendous intellectual capital” the community can draw on. Smith said, “I’m not disappointed with the track record because they are still in existence. There’s still opportunity, there’s still hope to grow and to expand, to have an impact. It just needs more community and campus support.”

What happens with UNO black studies is an open question considering its highly charged past and the widely held perception the university merely tolerates it. That wary situation is likely to continue until the department, the community and the university truly communicate.

“The difference between potential and reality is sometimes a wide chasm,” Hogan said. “The University of Nebraska system is seemingly oblivious to the opportunities and potential for the black studies department at UNO. They don’t seem to have a clue. They’ve got this little jewel there and rather than polish it and mount it and promote it, they seem to want to return it to the state of coal. I don’t get it.”

Related Articles

- Black Studies Programs Lack Support At HBCUs (huffingtonpost.com)

- Faculty Senate approves new honors degree in neuroscience – the University of Delaware (udel.edu)

- Black Studies Scholar Manning Marable Dead at 60 (theroot.com)

- UNO Wrestling Dynasty Built on a Tide of Social Change (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Letting 1,000 Flowers Bloom, The Black Scholar’s Robert Chrisman Looks Back at a Life in the Maelstrom (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- What Happens to a Dream Deferred? Beasley Theater Revisits Lorraine Hansberry’s ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Theater as Insurrection, Social Commentary and Corporate Training Tool (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Change is Gonna Come, the GBT Academy in Omaha Undergoes Revival in the Wake of Fire (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

The Brothers Sayers: Big legend Gale Sayers and little legend Roger Sayers (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Whether you’re visiting this blog for the first time or you’re returning for a repeat visit, then you should know that among the vast array of articles featured on this site is a series I penned for The Reader (www.thereader.com) in 2004-2005 that explored Omaha’s Black Sports Legends. We called the 13-part, 45,000 word series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness. The following story is one installment from that series. It features a pair of brothers, Gale Sayers and Roger Sayers, whose athletic brilliance made each of them famous in their own right, although the fame of Gale far outstripped that of Roger. Gale, of course, became a big-time football star at Kansas before achieving superstardom with the NFL‘s Chicago Bears. An unlikely set of circumstances saw his playing career end prematurely yet make him an even larger-than-life figure. A made-for-TV movie titled Brian’s Song (since remade) that detailed his friendship with cancer stricken teammate Brian Piccolo, cemented his immortal status, as did being elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame at age 29. Roger’s feats in both football and track were impressive but little seen owing to the fact he competed for a small college (the then-University of Omaha) and never made it to the NFL or Olympics, where many thought he would have excelled, the one knock against him being his diminutive size.

The Sayers brothers are among a distinguished gallery of black sports legends that have come out of Omaha. Others include Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, and Johnny Rodgers. You will find all their stories on this site, along with the stories of other athletic greats whose names may not be familiar to you, but whose accomplishments speak for themselves.

The Brothers Sayers: Big legend Gale Sayers and little legend Roger Sayers (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.theeader.com) as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out the Win: The Roots of Greatness

This is the story of two athletically-gifted brothers named Sayers. The younger of the pair, Gale, became a sports figure for the ages with his zig-zagging runs to daylight on a football field. His name is synonymous with the Chicago Bears. His oft-played highlight-reel runs through enemy lines form the picture of quicksilver grace. His well-documented friendship with the late Brian Piccolo endear him to new generations of fans.

The elder brother, Roger, forged a distinguished athletic career of his own, one of blazing speed on cinder and grass, but one overshadowed by Gale’s success.

From their early impoverished youth on Omaha’s near north side in the 1950s the Brothers Sayers dominated whatever field of athletic competition they entered, shining most brightly on the track and gridiron. As teammates they ran wild for Roberts Dairy’s midget football squad and anchored Central High School’s powerful football-track teams. Back then, Roger, the oldest by a year, led the way and Gale followed. For a long time, little separated the pair, as the brothers took turns grabbing headlines. Each was small and could run like the wind, just like their ex-track man father. But, make no mistake about it, Roger was always the fastest.

Each played halfback, sharing time in the same Central backfield one season. Heading into Gale’s sophomore year nature took over and gave Gale an edge Roger could never match, as the younger brother grew a few inches and packed-on 50 pounds of muscle. He kept growing, too. Soon, Gale was a strapping 6’0, 200-pound prototype halfback with major-college-material written all over him. Roger remained a diminutive 5’9, 150-pound speedster whose own once hotly sought-after status dimmed when, bowing to his parents’ wishes, he skipped his senior year of football rather than risk injury. Ironically, he tore a tendon running track the next spring. His major college prospects gone, he settled for then Omaha University.

Roger went on to a storied career at UNO, where he developed into one of America’s top sprinters and one of the school’s all-time football greats. He won the 100-meters at the 1964 Drake Relays. He captured both the 100-yard and 100-meter dashes at the 1963 Texas Relays. He took the 100 and 200 at the 1963 national NAIA meet. He ran well against Polish and Soviet national teams in AAU meets. The Olympic hopeful even beat the legendary American sprinter Bob Hayes in a race, but it was Hayes, known as “The Human Bullet,” who ended up with Olympic and NFL glory, not Sayers.

As an undersized but explosive cog in UNO’s full backfield, Sayers, dubbed “The Rocket,” averaged nearly eight yards per carry and 19 yards per reception over his four-year career. But it was as a return specialist he really stood out. Using his straight-away burst, he took back to the house three punts and five kickoffs for touchdowns. He holds several school records, including highest rushing average for a season (10.2) and career (7.8) and highest punt return average for a season (29.5) and career (20.6). His 99-yard TD catch in a 1963 game versus Drake is the longest scoring play from scrimmage in UNO history.

Roger Sayers running track for then-Omaha University

In football, size matters. For most of his playing career, however, Roger said his acute lack of size “never was a factor. I didn’t pay much attention to it. I didn’t lack any confidence when I got on the field. I always thought I could do well.”

Even with his impressive track credentials, Sayers, coming off an injury, was unable to find a sponsor for a 1964 Olympic bid. Even though his small stature never held him back in high school or college, it posed a huge obstacle in pro football, which after graduation he did not pursue right away because the studious and ambitious Sayers already had opportunities lined-up outside athletics. Still, in 1966, he gave the NFL a try when, after prodding from “the guys” at the Spencer Street Barbershop and a little help from Gale, he signed a free agent contract with his brother’s team, the Chicago Bears. Roger lasted the entire training camp and exhibition season with the club before bowing to reality and taking an office job.

“That’s when I realized I was too small,” Roger said of his NFL try.

Gale, the family superstar, is inducted in the college and pro football Halls of Fame but his glory came outside Nebraska, where he felt unappreciated. Racism likely prevented him being named Nebraska High School Athlete of the Year after a senior year of jaw-dropping performances. In leading Central to a share of the state football title, he set the Class A single season scoring record and made prep All-American. In pacing Central to the track and field title, he won three gold medals at the state meet, shattering the Nebraska long jump record with a leap of 24 feet, 10 inches, a mark that still stands today. He got revenge in the annual Shrine all-star game, scoring four touchdowns en route to being named outstanding player.

Recruited by Nebraska, then coached by Bill Jennings, Sayers considered the Huskers but felt uncomfortable at the school, which had ridiculously few black students then — in or out of athletics. Spurning the then-moribound NU football program for the University of Kansas, he heard people say he’d never be able to cut it in school. Sayers admits academics were not his strong suit in high school, not for lack of intelligence, but for lack of applying himself.

It took his father, a-$55-a-week car polisher, who’d walked away from his own chance at college, to set him straight. “People said I would fail. They called me dumb. But my dad said to me one time, ‘Gale, you are good enough,’ and just those words gave me the incentive that somebody believed in me. That’s all I needed. And I proved that I could do it.”

Sayers was also motivated by his brother, Roger, the bookish one who preceded him to college. Each went on to get two degrees at their respective schools.

On the field, Gale showed the Huskers what they missed by earning All-Big 8 and All-America honors as a Jayhawk and, in a 1963 game at Memorial Stadium the “Kansas Comet” lived up to his nickname by breaking-off a 99 yard TD run that still stands as the longest scoring play by an NU opponent. He was also a hurdler and long-jumper for the elite KU track program.

Upon entering the NFL with the Bears in 1965, Sayers made the most dramatic debut in league history, setting season records for total offense, 2,272, and touchdowns, 22, and a single game scoring record with 6 TDs. Named Rookie of the Year and All-Pro, he continued his brilliant play the next four seasons before the second of two serious knee injuries cut short his career in 1970. A mark of the impact he made is that despite playing only five full seasons, he’s routinely listed among the best running backs to ever play in the NFL.

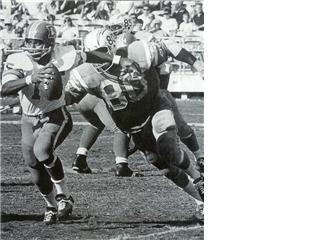

Gale Sayers with the Bears

His immortality was ensured by two things: in 1970, the story of his friendship with teammate Brian Piccolo, who died tragically of cancer, was dramatically told in a TV movie-of-the-week, Brian’s Song, (recently remade); and, in 1977, he was inducted into the pro football Hall of Fame at age 29, making him the youngest enshrine of that elite fraternity.

A quadruple threat as a rusher, receiver out of the backfield, kickoff return man and punt returner, Sayers’ unprecedented cuts saw him change directions — with the high-striding, gliding moves of a hurdler — in the blink of an eye while somehow retaining full-speed. In a blurring instant, he’d be in mid-air as he head-faked one way and swiveled his hips the other way before landing again to pivot his feet to race off against the grain. In the introduction to Gale’s autobiography, I Am Third, comic Bill Cosby may have come closest to describing the effect one of Sayers’ dramatic cuts left on him while observing from the sidelines and on the hapless defenders trying to corral him.

“I was standing there and Gale was coming around this left end. And there are about five or six defensive men ready, waiting for him…And I saw Gale Sayers split. I mean, like a paramecium. He just split in two. He threw the right side of his body on one side and the left side of his body kept going down the left side. And the defensive men didn’t know who to catch.”

The way Gale tells it, his talent for cutting resulted from his “peripheral vision,” a gift he had from the get-go. “When I was running I could see the whole field. I knew how fast the other person was running and the angle he was taking, and I knew all I had to do was make a certain move and I’m past him. I knew it — I didn’t have to think about it. I could see where people were and that gave me the ability to make up my mind what I would do before I got to a person,” he said. He reacted, on the fly, in tenths or hundreds of a second, to what he saw. “

All the so-called great moves in football are instinct,” he said. “It’s not planned. I don’t go down the football field saying, ‘Oh, this fella’s to my right, I better cut left,’ or whatever. You don’t plan it. You’re running with the football and you just do what comes natural…There were so many times in high school, college and pro ball when I was going around left end or right end and there was nothing there, and then I went the other way. You can’t teach that. That’s instinctive.”

He said his greatest asset was not speed, but quickness — combined with that innate ability to improvise on the run. “Every running back has speed, but a lot of running backs don’t have the quickness to hit a hole or to change directions, and I always could do that. A lot of times a hole is clogged and then you’ve got to do something else — either change directions or hit another hole or bounce it to the outside and go someplace else.”

Lightning fast moves may have sprung from an unlikely source — flag football, something Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Rodgers also credits with helping develop his dipsy-doodle elusiveness.

“The flags were pretty easy to grab and pull out,” Sayers said, “and so, yes, you had to develop some moves to keep people away from the flags.” The Sayers boys got their first exposure to organized competition playing in the Howard Kennedy Grade School flag football program coached by Bob Rose. An old-school disciplinarian who mentored many of north Omaha’s greatest athletes when they were youths, Rose embodied respect.

“He was a tough coach. I think he had a little attitude that said, in being black, you’ve got to be twice as good, and I think he tried to instill that in us at an early age. He’d say things like, ‘You have to be faster, you have to be tougher, you’ve got to hit harder.’ We all developed that attitude that, ‘Hey, we’ve got to do better because we’re black.’ And I think that stuck with me,” Gale said.

According to Roger, coaches like Rose and the late Josh Gibson (Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson’s oldest brother), whom the brothers came in contact with playing summer softball, “made it possible for people to succeed. They were good coaches because they taught you the fundamentals, they taught you to be respectful of people and they taught you the ethics of the game. These were folks that…made sure you played in an organized, structured event, so you could get the most out of it. They also had an uncanny ability to identify athletes and to motivate athletes to want to play and to achieve. They were part of an environment we had growing up where we had strong support systems around us.”

From the mid-1950s through the late 1960s Omaha’s inner city produced a remarkable group of athletes who achieved greatness in a variety of sports. Many observers have speculated on the whys and hows of that phenomenal run of athletic brilliance. The consensus seems to be that athletes from the past didn’t have to contend with a lot of the pressures and distractions kids face today, thus allowing a greater concentration on and passion for sports.

“Growing up, we didn’t have access to cars or play stations or arcade games,” Roger said. “We didn’t have to deal with the intense peer pressure kids are influenced by today. Because we didn’t have these things, we were able to focus in on our sports.”

For black youths like the Sayers and their buddies, options were even more confining in the ‘50s, when racial minorities were denied access to recreational venues such as the Peony Park pool and were discouraged from so-called country-club activities such as golf, which left more time and energy to devote to traditional inner city sports. “

Every day after school we were in Kountze park or some place playing a sport — football, basketball, baseball, whatever it may be. There wasn’t a whole lot else we could do,” Gale said. “So, we were in the park playing sports. Our mamas and daddies had to call us to come eat dinner because we were out there playing.”

Gale said that as youths he and his friends had such a hunger for football that after completing flag football practice, they would then go to the park to knock heads “with the big kids” from local high schools in pick-up games. “It’s a wonder no one ever got seriously injured because we had no pads, no nothing, and we played tackle. It really made us tougher.”

Dennis Fountain, a friend and fellow athlete from The Hood, said the Sayers would often compete for opposing sides in those informal games. “You wouldn’t think those two guys were brothers,” he said. “They would mix it up good.”

Speaking of tough, the brothers tussled in a pair of now mythic neighborhood football games held around the holidays. There was the Turkey Bowl played on Thanksgiving and the Cold Bowl played on Christmas. “We had some knock-down, drag-out athletic contests out there,” said Gale, referring to the annual games that drew athletes of all ages from Omaha’s north and south inner city projects. “We were a little young, but the fellas’ saw the talent we had and let us play.”

Then, there was the rich proving ground he and Roger found themselves competing in — playing with or against such fine athletes as the Nared brothers (Rich and John), Vernon Breakfield, Charlie Gunn, Bruce Hunter, Ron Boone. “No doubt about it, we fed off one another. We saw other people doing well and we wanted to do just as well,” Gale said. As the Sayers began asserting themselves, they pushed each other to excel.

“When he achieved something, I wanted to achieve something, and vice versa,” Roger said. “I mean, you never wanted to be upstaged or outdone, but by the same token we were always proud and overjoyed by each other’s success. We were as competitive as brothers are.”

Roger and Gale had so much ability that the exploits of their baby brother, Ron, are obscured despite the fact he, too, possessed talent, enough in fact for the UNO grad to be a number two draft pick by the San Diego Chargers in 1968.

Each also knew his limitations in comparison with the other. Roger played some mean halfback himself, but he knew on a football field he was only a shadow of Gale, whom nature blessed with size, speed, vision and instinct. Where Gale was a fine hurdler, relay man and long-jumper, he knew he could not beat Roger in a sprint. “I wasn’t going to get into the 100 or 220-yard dash and run against him because he was much, much faster than I was,” Gale said. “He was great in track.”

As much as he downplays his own track ability, Gale held his own in one of the strongest collegiate track programs at Kansas. It was under KU track and field coach Bill Easton he discovered a work ethic and a mantra that have guided his life ever since.

“I thought I worked hard getting ready for football,” he said, “but when I joined his track team I couldn’t believe the amount of work he put me through and I couldn’t believe I could do it. But within months I could do everything he asked me to, and I was in excellent shape. He told me, ‘Gale, you cannot work hard enough in any sport, especially in track.’ The things I did for him on the track team carried on through my pro career in football.

“Every training camp I came in shape, and I mean I came in shape. I was ready to play and put the pads on the first day of camp, where many guys would go to camp to get in shape.”

On the eve of his pro career, Sayers was entertaining some doubts about how he would do when Easton reminded him what made him special. “You go for broke every time you go.” Sayers said it’s a lesson he’s always tried to follow.

A saying printed on a card atop the desk in Easton’s office intrigued Sayers. The enigmatic words said, I Am Third. When he asked his coach their meaning, he was told they came from a kind of proverb that goes, The Lord is First, My Friends are Second, I Am Third. The athlete was so taken with its meaning he went out and had it inscribed on a medallion he wore for years afterwards. His wife Linda now has it.

The saying became the title of his 1970 autobiography. The philosophy bound up in it helped him cope with the abrupt end of his playing days. “All the talent I had, the Lord gave me. And it was the Lord that decided to take it away from me,” Gale said. “That probably helped me accept the fact that, hey, I couldn’t do it anymore. I had a very short career, but a very good career. I was satisfied with that.”

Life after athletic competition has been relatively smooth for Gale and his brother. Roger embarked on a long executive corporate career, interrupted only by a stint as the City of Omaha’s Human Relations Director under Mayor Gene Leahy. He retired from Union Pacific a few years ago. Today, he’s a trustee with Salem Baptist Church. Gale served as athletic director at Southern Illinois University before starting his own sports marketing and public relations firm, Sayers and Sayers Enterprises. Next, he launched Sayers Computer Source, a provider of computer products and technology solutions to commercial customers. Today, SCS has brnaches nationwide and revenues in excess of $150 million. Besides running his companies, Sayers is in high demand as a motivational speaker.

Both men have tried distancing themselves from being defined by their athletic prowess alone.

“I want people to view me as an individual that brings something to the table other than the fact I could run track and play football. That stuff is behind me. There are other things I can do,” said Roger. For Gale, it was a matter of being ready to move on. “I’ve always said, As you prepare to play, you must prepare to quit, and I prepared to quit. I didn’t have to look back and say, What am I going to do now? I did other things.”

Getting on with their lives has been a constant with the brothers since growing up with feuding, alcoholic parents, sparse belongings and little money in “The Toe,” as Gale said residents referred to the north Omaha ghetto. His family moved to Omaha from bigoted small towns in Kansas, where the Sayers lived until Gale was 8, but instead of the fat times they envisioned here they only found despair.

Finding a way out of that cycle became an overriding goal for Gale and his brothers.

“Yes, we had tough times, but everybody in the black neighborhood had a tough time. Our dad always said, ‘Gale, Roger, Ronnie…sorry it didn’t work out for your mother and I, but you need to get your education and make something better for yourselves.’” The fact he and Roger went on to great heights taught Gale that “if you want to make it bad enough, no matter how bad it is, you can make it.”

Related Articles

- Gale Sayers’s Knee, and the Dark Ages of Medicine (fifthdown.blogs.nytimes.com)

- The 32 Greatest NFL Running Backs (sports-central.org)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Sayers: Current players should help pioneers (sports.espn.go.com)

- John Mackey’s death has Gale Sayers ticked off at today’s NFL (profootballtalk.nbcsports.com)

Prodigal Son: Marlin Briscoe takes long road home (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

I never saw Marlin Briscoe play college football, but as I came of age people who had see The Magician perform regaled me with stories of his improvisational playmaking skills on the gridiron, and so whenever I heard or read the name, I tried imagining what his elusive, dramatic, highlight reel runs or passes looked like. Mention Briscoe’s name to knowledgable sports fans and they immediately think of a couple things: that he was the first black starting quarterback in the National Football League; and that he won two Super Bowl rings as a wide receiver with the Miami Dolphins. But as obvious as it seems, I believe that both during his career and after most folks don’t appreciate (1) how historic the first accomplishment was and (2) don’t recognize how amazing it was for him to go from being a very good quarterback in the league, in the one year he was allowed to play the position, to being an All-Pro wideout for Buffalo. Miami thought enough of him to trade for him and thereby provide a complement to and take some heat off of legend Paul Warfield.

The following story I did on Briscoe appeared not long after his autobiography came out. I made arrangements to inteview him in our shared hometown of Omaha, and he was every bit as honest in person as he was in the pages of his book, which chronicles his rise to stardom, the terrible fall he took, and coming back from oblivion to redeem himself. The story appeared in a series I did on Omaha’s Black Sports Legends, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, for The Reader (www.thereader.com) in 2004-2005. Since then, there’s been a campaign to have the NFL’s veterans committee vote Briscoe into the Hall of Fame and there are plans for a feature film telling his life story.

Prodigal Son:

Marlin Briscoe takes long road home (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness

Imagine this is your life: Your name is Marlin Briscoe. A stellar football-basketball player at Omaha South High School in the early 1960s, you are snubbed by the University of Nebraska but prove the Huskers wrong when you become a sensation as quarterback for then Omaha University, where from 1963 to 1967, you set more than 20 school records for single game, season and career offensive production.

Because you are black the NFL does not deem you capable of playing quarterback and, instead, you’re a late round draft choice, of the old AFL, at defensive back. Injured to start your 1968 rookie season, the offense sputters until, out of desperation, the coach gives you a chance at quarterback. After sparking the offense as a reserve, you hold down the game’s glamour job the rest of the season, thus making history as the league’s first black starting quarterback. When racism prevents you from getting another shot as a signal caller, you’re traded and excel at wide receiver. After another trade, you reach the height of success as a member of a two-time Super Bowl-winning team. You earn the respect of teammates as a selfless clutch performer, players’ rights advocate and solid citizen.

Then, after retiring from the game, you drift into a fast life fueled by drugs. In 12 years of oblivion you lose everything, even your Super Bowl rings. Just as all seems lost, you climb out of the abyss and resurrect your old self. As part of your recovery you write a brutally honest book about a life of achievement nearly undone by the addiction you finally beat.

You are Marlin Oliver Briscoe, hometown Omaha hero, prodigal son and the man now widely recognized as the trailblazer who laid the path for the eventual black quarterback stampede in the NFL. Now, 14 years removed from hitting rock bottom, you return home to bask in the glow of family and friends who knew you as a fleet athlete on the south side and, later, as “Marlin the Magician” at UNO, where some of the records you set still stand.

Now residing in the Belmont Heights section of Long Beach, Calif. with your partner, Karen, and working as an executive with the Roy W. Roberts Watts/Willowbrook Boys and Girls Club in Los Angeles, your Omaha visits these days for UNO alumni functions, state athletic events and book signings contrast sharply with the times you turned-up here a strung-out junkie. Today, you are once again the strong, smart, proud warrior of your youth.

Looking back on what he calls his “lost years,” Briscoe, age 59, can hardly believe “the severe downward spiral” his life took. “Anybody that knows me, especially myself, would never think I would succumb to drug addiction,” he said during one of his swings through town. “

All my life I had been making adjustments and overcoming obstacles and drugs took away all my strength and resolve. When I think about it and all the time I lost with my family and friends, it’s a nightmare. I wake up in a cold sweat sometimes thinking about those dark years…not only what I put myself through but a lot of people who loved me. It’s horrifying.

“Now that my life is full of joy and happiness, it just seems like an aberration. Like it never happened. And it could never ever happen again. I mean, somebody would have to kill me to get me to do drugs. I’m a dead man walking anyway if I ever did. But it’s not even a consideration. And that’s why it makes me so furious with myself to think why I did it in the first place. Why couldn’t I have been like I am now?”

Or, like he was back in the day, when this straight arrow learned bedrock values from his single mother, Geneva Moore, a packing house laborer, and from his older cousin Bob Rose, a youth coach who schooled him and other future greats in the parks and playing fields of schools and recreation centers in north and south Omaha.

For Briscoe, the pain of those years when, as he says, “I lost myself,” is magnified by how he feels he let down the rich, proud athletic legacy he is part of in Omaha. It is a special brotherhood. One in which he and his fellow members share not only the same hometown, but a common cultural heritage in their African–American roots, a comparable experience in facing racial inequality and a similar track record of achieving enduring athletic greatness.

Marlin Briscoe, a South High alum, is honored with a street named in his honor on Oct. 22, 2014.

Briscoe came up at a time when the local black community produced, in a golden 25-year period from roughly 1950 to 1975, an amazing gallery of athletes that distinguished themselves in a variety of sports. He idolized the legends that came before him like Bob Boozer, a rare member of both Olympic Gold Medal (at the 1960 Rome Games) and NBA championship (with the 1971 Milwaukee Bucks) teams, and MLB Hall of Famer and Cy Young Award winner Bob Gibson. He honed his skills alongside greats Roger Sayers, one of the world’s fastest humans in the early 1960s, NFL Hall of Famer Gale Sayers and pro basketball “Iron Man” Ron Boone. He inspired legends that came after him like Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Rodgers.

Each legend’s individual story is compelling. There are the taciturn heroics and outspoken diatribes of Gibson. There are the knee injuries that denied Gale Sayers his full potential by cutting short his brilliant playing career and the movies that dramatically portrayed his bond with doomed roommate Brian Piccolo. There are the ups and downs of Rodgers’ checkered life and career. But Briscoe’s own personal odyssey may be the most dramatic of all.

Born in Oakland, Calif. in 1945, Briscoe and his sister Beverly were raised by their mother after their parents split up. When he was 3, his mother moved the family to Omaha, where relatives worked in the packing houses that soon employed her as well. After a year living on the north side, the family moved to the south Omaha projects. Between Kountze Park in North O and the Woodson Center in South O, Briscoe came of age as a young man and athlete. In an era when options for blacks were few, young men like Briscoe knew that athletic prowess was both a proving ground and a way out of the ghetto, all the motivation he needed to work hard.

“Back in the ‘50s and early ‘60s we had nothing else to really look forward to except to excel as black athletes,” Briscoe said. “Sports was a rite-of-passage to respect and manhood and, hopefully, a way to bypass the packing houses and better ourselves and go to college. When Boozer (Bob) went to Kansas State and Gibson (Bob) went to Creighton, that next generation — my generation — started thinking, If I can get good enough in sports, I can get a scholarship to college so I can take care of my mom. That’s how all of us thought.”

Like many of his friends, Briscoe grew up without a father, which combined with his mother working full-time meant ample opportunity to find mischief. Except that in an era when a community really did raise a child, Briscoe fell under the stern but caring guidance of the men and women, including Alice Wilson and Bob Rose, that ran the rec centers and school programs catering to largely poor kids. By the time Briscoe entered South High, he was a promising football-basketball player.

On the gridiron, he’d established himself as a quarterback in youth leagues, but once at South shared time at QB his first couple years and was switched to halfback as a senior, making all-city. More than just a jock, Briscoe was elected student council president.

Scholarship offers were few in coming for the relatively small — 5’10, 170-pound — Briscoe upon graduating in 1962. The reality is that in the early ‘60s major colleges still used quotas in recruiting black student-athletes and Briscoe upset the balance when he had the temerity to want to play quarterback, a position that up until the 1980s was widely considered too advanced for blacks.

But UNO Head Football Coach Al Caniglia, one of the winningest coaches in school history, had no reservations taking him as a QB. Seeing limited duty as a freshman backup to incumbent Carl Meyers, Briscoe improved his numbers each year as a starter. After a feeling-out process as a sophomore, when he went 73 of 143 for 939 yards in the air and rushed for another 370 yards on the ground, his junior year he completed 116 of 206 passes for 1,668 yards and ran 120 times for 513 yards to set a school total offense record of 2,181 yards in leading UNO to a 6-5 mark.

What was to originally have been his senior year, 1966, got waylaid, as did nearly his entire future athletic career, when in an indoor summer pickup hoops game he got undercut and took a hard, headfirst spill to the floor. Numb for a few minutes, he regained feeling and was checked out at a local hospital, which gave him a clean bill of health.

Even with a lingering stiff neck, he started the ‘66 season where he left off, posting a huge game in the opener, before feeling a pop in his throbbing neck that sent him “wobbling” to the sidelines. A post-game x-ray revealed a fractured vertebra, perhaps the result of his preseason injury, meaning he’d risked permanent paralysis with every hit he absorbed. Given no hope of playing again, he sat out the rest of the year and threw himself into academics and school politics. After receiving his military draft notice, he anxiously awaited word of a medical deferment, which he got. Without him at the helm, UNO crashed to a 1-9 mark.

Then, a curious thing happened. On a follow-up medical visit, he was told his broken vertebra was recalcifying enough to allow him to play again. He resumed practicing in the spring of ‘67 and by that fall was playing without any ill effects. Indeed, he went on to have a spectacular final season, attracting national attention with his dominating play in a 7-3 campaign, compiling season marks with his 25 TD throws and 2,639 yards of total offense, including a dazzling 401-yard performance versus tough North Dakota State at Rosenblatt Stadium.

Projected by pro scouts at cornerback, a position he played sparingly in college, Briscoe still wanted a go at QB, so, on the advice of Al Caniglia he negotiated with the Denver Broncos, who selected him in the 14th round, to give him a look there, knowing the club held a three-day trial open to the public and media.

“I had a lot of confidence in my ability,” Briscoe said, “and I felt given that three-days at least I would have a showcase to show what I could do. I wanted that forum. When I got it, that set the tone for history to be made.”

At the trial Briscoe turned heads with the strength and accuracy of his throws but once fall camp began found himself banished to the defensive backfield, his QB dreams seemingly dashed. He earned a starting cornerback spot but injured a hamstring before the ‘68 season opener.

After an 0-2 start in which the Denver offense struggled mightily out of the gate, as one QB after another either got hurt or fell flat on his face, Head Coach Lou Saban finally called on Briscoe in the wake of fans and reporters lobbying for the summer trial standout to get a chance. Briscoe ran with the chance, too, despite the fact Saban, whose later actions confirmed he didn’t trust a black QB, only gave him a limited playbook to run. In 11 games, the last 7 as starter, Briscoe completed 93 of 224 passes for 1,589 yards with 14 TDs and 13 INTs and he ran 41 times for 308 yards and 3 TDs in helping Denver to a 5-6 record in his 11 appearances, 5-2 as a starter.

Briscoe proved an effective improviser, using his athleticism to avoid the rush, buy time and either find the open receiver or move the chains via scrambling. “Sure, my percentage was low, because initially they didn’t give me many plays, and so I was out there played street ball…like I was down at Kountze Park again…until I learned the cerebral part of the game and then I was able to improve my so-called efficiency,” is how Briscoe describes his progression as an NFL signal caller.

By being branded “a running” — read: undisciplined — quarterback in an era of strictly drop back pocket passers, with the exception of Fran Tarkenton, who was white, Briscoe said blacks aspiring to play the position faced “a stigma” it took decades to overcome.

Ironically, he said, “I never, ever considered myself a black quarterback. I was just a quarterback. It’s like I never thought about size either. When I went out there on the football field, hey, I was a player.”

All these years later, he still bristles at the once widely-held notions blacks didn’t possess the mechanics to throw at the pro level or the smarts to grasp the subtleties of the game or the leadership skills to command whites. “How do you run in 14 touchdown passes? I could run, sure. I could buy more time, yeah. But if you look at most of my touchdown passes, they were drop back passes. I led the team to five wins in seven starts. We played an exciting brand of football. Attendance boomed. If I left any legacy, it’s that I proved the naysayers wrong about a black man manning that position…even if I never played (QB) again.”

Despite his solid performance — he finished second in Rookie of the Year voting — he was not invited to QB meetings Saban held in Denver the next summer and was traded only weeks before the ‘69 regular season to the Buffalo Bills, who wanted him as a wide receiver.

His reaction to having the quarterback door slammed in his face? “I realized that’s the way it was. It was reality. So, it wasn’t surprising. Disappointing? Yes. All I wanted and deserved was to compete for the job. Was I bitter? No. If I was bitter I would have quit and that would have been the end of it. As a matter of fact, it spurred me to prove them wrong. I knew I belonged in the NFL. I just had to make the adjustment, just like I’ve been doing all my life.”

The adversity Briscoe has faced in and out of football is something he uses as life lessons with the at-risk youth he counsels in his Boys and Girls Club role. “I try to tell them that sometimes life’s not fair and you have to deal with it. That if you carry a bitter pill it’s going to work against you. That you just have to roll up your sleeves and figure out a way to get it done.”

While Briscoe never lined up behind center again, soon after he left Denver other black QBs followed — Joe Gilliam, Vince Evans, Doug Williams and, as a teammate in Buffalo, James Harris, whom he tutored. All the new faces confronted the same pressures and frustrations Briscoe did earlier. It wasn’t until the late 1980s, when Williams won a Super Bowl with the Redskins and Warren Moon put up prolific numbers with the Houston Oilers, that the black QB stigma died.

Briscoe was not entirely aware of the deep imprint he made until attending a 2001 ceremony in Nashville remembering the late Gilliam. “All the black quarterbacks, both past and present, were there,” said Briscoe, naming everyone from Aaron Brooks (New Orleans Saints) to Dante Culpepper (Minnesota Vikings) to Michael Vick (Atlanta Falcons).

“The young kids came up to me and embraced me and told me, ‘Thank you for setting the tone.’ Now, there’s like 20 black quarterbacks on NFL rosters, and for them to give me kudos for paving the way and going through what I went through hit me. That was probably the first time I realized it was a history-making event. The young kids today know about the problems we faced and absorbed in order for them to get a fair shot and be in the position they are.”

Making the Buffalo roster at a spot he’d never played before proved one of Briscoe’s greatest athletic challenges and accomplishments. He not only became a starter but soon mastered the new position, earning 1970 All-Pro honors in only his second year, catching 57 passes for 1,036 yards and 8 TDs. Then, in an example of bittersweet irony, Saban was named head coach of the moribund Bills in 1972 and promptly traded Briscoe to the powerful Miami Dolphins. The move, unpopular with Bills’ fans, once again allowed Briscoe to intersect with history as he became an integral member of the Dolphins’ perfect 17-0 1972 Super Bowl championship team and the 1973 team that repeated as champs.

Following an injury-plagued ‘74 season, Briscoe became a vagabond — traded four times in the space of one year — something he attributes to his involvement in the 1971 lawsuit he and five other players filed against then-NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle, an autocrat protecting owners’ interests, in seeking the kind of free agency and fair market value that defines the game today. Briscoe and his co-complainants won the suit against the so-called Rozelle Rule but within a few years they were all out of the game, labeled troublemakers and malcontents.

His post-football life began promisingly enough. A single broker, he lived the L.A. high life. Slipping into a kind of malaise, he hung with “an unsavory crowd” — partying and doing drugs. His gradual descent into addiction made him a transient, frequenting crack houses in L.A.’s notorious Ho-Stroll district and holding down jobs only long enough to feed his habit. The once strapping man withered away to 135 pounds. His first marriage ended, leaving him estranged from his kids. Ex-teammates like James Harris and Paul Warfield, tried helping, but he was unreachable.

“I strayed away from the person I was and the people that were truly my friends. When I came back here I was trying to run away from my problems,” he said, referring to the mid-’80s, when he lived in Omaha, “and it got worse…and in front of my friends and family. At least back in L.A. I could hide. I saw the pity they had in their eyes but I had no pride left.”

Perhaps his lowest point came when a local bank foreclosed on his Super Bowl rings after he defaulted on a loan, leading the bank to sell them over e-bay. He’s been unable to recover them.

He feels his supreme confidence bordering on arrogance contributed to his addiction. “I never thought drugs could get me,” he said. “I didn’t realize how diabolical and treacherous drug use is. In the end, I overcame it just like I overcame everything else. It took 12 years…but there’s some people that never do.” In the end, he said, he licked drugs after serving a jail term for illegal drug possession and drawing on that iron will of his to overcome and to start anew. He’s made amends with his ex-wife and with his now adult children.

Clean and sober since 1991, Briscoe now shares his odyssey with others as both a cautionary and inspirational tale. Chronicling his story in his book, The First Black Quarterback, was “therapeutic.” An ESPN documentary retraced the dead end streets his addict’s existence led him to, ending with a blow-up of his fingers, bare any rings. Briscoe, who dislikes his life being characterized by an addiction he’s long put behind him, has, after years of trying, gotten clearance from the Dolphins to get duplicate Super Bowl rings made to replace the ones he squandered.

For him, the greatest satisfaction in reclaiming his life comes from seeing how glad friends and family are that the old Marlin is back. “Now, they don’t even have to ask me, ‘Are you OK?’ They know that part of my life is history. They trust me again. That’s the best word I can use to define where I am with my life now. Trust. People trust me and I trust myself.”

Related Articles

- Black like me (cbc.ca)

- Black like me: CFL QB legacy (cbc.ca)

- UNO Wrestling Dynasty Built on a Tide of Social Change (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Today’s Exploration: Omaha’s History of Racial Tension (theprideofnebraska.blogspot.com)

- Omaha Native Steve Marantz Looks Back at the City’s ’68 Racial Divide Through the Prism of Hoops in His New Book, ‘The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Eric Crouch To Play For UFL’s Omaha Nighthawks, Fulfill Destiny (sbnation.com)

Lela Knox Shanks: Woman of conscience, advocate for change, civil rights and social justice champion

UPDATE: As the world turns these days I know when the subject of one of my stories on this blog is in the news by the corresponding uptick in views. When I noted dozens of viewers landing on my profile about Lela Knox Shanks I hoped for the best but suspected the worst, and sadly as some of you reading this right now already know she has passed away after a long illness. She is a woman worth remembering and if you haven’t read the story below yet I trust you’ll take the time to. If you don’t know nothing about her, then by all means familiarize yourself with some of her work and experiences in the civil rights and social justice struggle. If you knew her or her story, you still might find oout something new about her you didn’t know before. In either case, you’ll be honoring her memory by reading about her good works. Rest in peace, Lela.

New Horizons editor Jeff Reinhardt told me about the subject of this profile, Lela Knox Shanks, and I’m glad he did. I’d never heard of her, but she’s someone who deserves to be more widely known because she’s spent the better part of her 80-plus years doing the right thing in the struggle for freedom, justice, and equal rights. Jeff and I drove to meet with her at her home in Lincoln, Neb., and we were both captivated by her unwavering commitment to equality. She’s taken many brave stances in her life and she’s paid some dear prices, but she’s never backed down, never given up. She’s a model and an inspiration for us all. I think you’ll find as memorable and impressive as Jeff and I did.

JILL PEITZMEIER / Lincoln Journal Star

Lela Shanks, pictured in her home in 2008. (LJS file)

Lela Knox Shanks: Woman of conscience, advocate for change, civil rights and social justice champion

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Activist, humanitarian, scholar, speaker, feminist and author Lela Knox Shanks could be excused for getting weary after a lifetime of agitating for equal rights. As an 81-year-old African American who came of age in the Jim Crow South and fought many civil rights battles in the Midwest, she’s stood up against injustice. She’s picketed, protested, demonstrated. She’s written countless letters to elected officials.

Driving up to the cozy home in Lincoln, Neb. she’s resided in 43 years, expressions of her activism are visible in sloganed signs on her porch: “War is not the answer,” “Every human being is born legal,” “The State should be about life, not death.” She’s butted heads with the-powers-that-be. She’s advocated for the oppressed. At various times her activities have made her the object of harassment and surveillance. She’s been arrested but never convicted for her civil disobedience.

Her partner in life and in social justice causes was her husband of 50 years, the late Hughes Hannibal Shanks, who developed Alzheimer’s Disease in the mid-1980s.

A fellow product of the South, he fought his own battles on the job and in the community. Together, the couple proved an immovable force, never backing down from a perceived wrong, always striving to do the right thing. They saw much social progress flower in America, including gains by minorities in education, employment, housing. Their children, now grown with families of their own, are all professionals. The prospects for their grandchildren, bright, too.

AD marked the progressive loss of her best friend. She was Hughes’s primary caregiver when little information about the illness or how to care for loved ones afflicted with it existed. She did what she always does when confronted with an obstacle, she educated herself and threw herself into finding solutions.

Hughes had been the family radical. He presided over lively discussions at the dinner table. Everyone was expected to join in. He and Lela were kindred spirits with their keen social consciousness. As dementia stole more and more of him, she said, “the thing I missed most about my husband was that I didn’t have anybody that I could share that kind of intimacy of conversation with.”

Her odyssey caring for him was a profound experience. It led her to write a book, Your Name is Hughes Hannibal Shanks: A Caregiver’s Guide to Alzheimer’s, that received praise upon its initial 1996 publication and 1999 reprint. It was a fitting project for a woman who earned a college journalism degree and worked for the famous black newspaper, The Chicago Defender, but who abandoned a dreamed-of career as a writer in deference to Hughes’s wish she not work but raise the kids.

Reception to the book was so strong she became a much-in-demand public speaker, thus ushering in a new phase in her life as a lecturer and independent scholar. For years she’s shared her insights on caregiving with audiences around the country. She’s also given many talks about women’s empowerment, once serving on a United Nations panel addressing the subject.

She’s made many African American history presentations, too. Just as she became an expert on caregiving for AD by reading everything she could find on it, she researched black history so she could share this rich heritage with others.

“When I became a speaker on African American history for the Nebraska Humanities Council,” she said, “I made a comprehensive study of it.”

That’s the way Lela does things. No half measures. It’s all or nothing with her.

Her interest in history was stoked by the legacy of her great-grandmother, Hannah Mason McCrutcheon, who was born a slave. Lela knew her well and said this matriarch’s proudest moment was having seen Abraham Lincoln speak. This is why Lela’s so passionate to have history disseminated.

“I went to segregated schools (in Oklahoma) and in my school I took Negro history,” Lela said. “So I grew up learning it. Plus, I heard famous African Americans speak at my high school. Mary McLeod Bethune for one.”

Slavery was a taboo topic, however, in her family. Whenever Lela tried bringing it up with her elders, she said, “It was always, ‘Baby, we don’t talk about that.’ It was too awful.” It’s a painful enough history that generations later some descendants of slaves would rather not be reminded of it. “I have relatives today that don’t want me to ever say anything about that. I guess its’ so degrading.”

Linked as she is to that past Lela testified before the Nebraska Judiciary Committee last April in support of a resolution (LR284) that the state apologize for slavery.

“Words cannot really express the emotion I feel, living long enough to testify at such an historic hearing,” she told members. “An acknowledgement by this official body of the historical facts of injustices perpetrated on African Americans due to race, dating back to the Nebraska Territory, clears the air and provides an atmosphere in which honest racial healing and reconciliation can finally begin to take place in Nebraska.

“Passage of this official document can hopefully provide school administrators and teachers with the courage and the information and the permission to teach, finally, an inclusive American history not yet included in American history textbooks, thus preparing all Nebraska children with a better understanding of themselves and their prejudices…and to live in the larger, multicultural world…”

After Hughes died in 1998 there was a hole in her that could not be filled. No one could have blamed her if she’d retreated from her public life. But she’s gone right on fighting the good fight. That’s because adversity is her old friend. “We were born into it,” is how she puts it. Life in the South was a constant reminder to blacks of their second-class citizen status. “It was something I was constantly plagued by growing up,” she added. “One of the hardest things for me to accept was why I have to be treated this way. Why can’t I do something about this?” The experience toughened her for the hard times.

“My husband and I didn’t set out to be activists. We really just wanted to have whatever a so-called normal life was and raise our family, go to church and do the things that were acceptable, support the government where we could.”

Lela Knox Shanks has enjoyed pressing flowers almost all her life. Her husband made the frames and she said she gave at least 500 as gifts.

Racism made that difficult. Said Lela, “From time to time as African Americans you get so tired of it all. You would like for it to just go away. You’d kind of like to not have to think about it. But we could not ignore it, there was just no way.”

She and Hughes, a World War II vet 10 years her elder, met at Lincoln University outside St. Louis. She graduated with a journalism degree and he with a law degree. He worked for the Social Security Administration. They started their family in segregated St. Louis. When denied the opportunity to apply for jobs he was qualified for he moved the family to Denver, Colo. in the early-’50s.

“Denver was like heaven,” she said, “because we could go to the swimming pools, we could go to the museums, we could go to restaurants. It was wonderful.”

But when the couple’s oldest child, Nena, was denied equal access to the education they wanted for her, Lela drew the line.

“I went to the Urban League, the NAACP, all the civil rights organizations, to see if there was anything they could do about the problem,” she said. “There wasn’t any help coming from anybody, and I just threw myself across the bed and cried, and then it just came to me — You’re the one who’s going to have to do something.”

Questioning authority is something Lela inherited from her Okie upbringing.

“I’m not sure my parents would have even known civil rights, it was just that my mother was given intuitively the ability to speak up for herself. She was not afraid to be her own advocate, and I always say I learned that at my mothers breast because I never had that problem. It’s a great feeling to feel like you always have the inner strength to speak for yourself. It was just given to me — that’s the only way I can explain it.”

Growing up under such “a powerful person” as her mother, who “defied whatever” was in her way, Lela knew she, too, could stand up for her rights.

This same sense of independence is something Lela and Hughes instilled in their own children. As a token of their admiration and appreciation for that lesson they presented her with a card that simply reads, “Question Everything.” It’s displayed on the mantel above her fireplace, next to some of her many awards.

“That’s what my children gave me because that’s what we had taught them — question us, because if you don’t question us and state yourself and stand up for yourself as a human being with us, you won’t stand up to other authority figures. And that’s what you have to do in life — you’ve got to be your own advocate. You can’t depend on somebody else being there for you.”

When the time came for Lela and Hughes to stand together, they never wavered.

“We were different in many ways but we were essentially the same when it came to what was important to us. When we were courting we talked about what was important to us in life. We wanted to help our people but what, of course, I came to realize was that I was helping myself.”

Faced with an unfeeling educational system and Hughes once running into a glass ceiling at work, the family left Denver for Kansas City, Kan. at the height of the civil rights movement. There, they butted heads with the public school board. She said boards then used such tactics as gerrymandered school boundaries, selective pupil transfers and feeder schools “to keep the schools separate and unequal.”

Upset by this bias the couple joined others in lodging complaints and finally withdrew their children from school to enroll them in a “protest school” they opened at home. Others joined the protest by removing their kids from the public schools and having them attend what students lovingly called Shanks University.

Ten children in all attended Shanks U that 1962-63 school year. Lela was their primary educator. The ruling class though took a dim view of this renegade school operating in defiance of the established order.

“We were going against the power structure so they weren’t about to certify us and that’s why we were arrested for truancy,” Lela said. “We didn’t trust any of the attorneys there and so we went to Topeka to retain Elijah Scott, the attorney who filed the original brief for the Brown vs. Board of Education case.”

The arraignment proved traumatic. Lela remembers: “Our attorney went to post the bond and while he was gone a couple deputies came over. One pulled on me from one side and the other pulled on me from another side, with my husband and children standing there. My husband knew not to move, not to say a word. The children though were yelling and screaming, ‘Mama, Mama,’ and hanging onto my legs, because it was obvious they were trying to take me away. That was the most terrifying thing about that experience.”

Scott returned just in time, her bond posted, and she was released. Lela and her family left the courthouse breathing a sigh of relief.