Archive

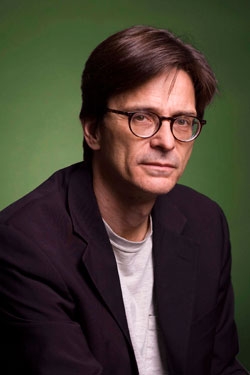

He knows it when he sees it: Journalist-social critic Robert Jensen finds patriarchy and white supremacy in porn

Robert Jensen is one of those writers who challenges preconceived ideas we all have about things we think we already have figured out. Among the many subjects he trains his keen intellect on are race, politics, misogny, and white supremacy and things really get interesting when he analyzes America’s and the world’s penchant for porn through the prism of those constructs. I interviewed him a couple years ago on these matters in advance of a talk he gave in Omaha, and the following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) is the result.

He knows it when he sees it: Journalist-social critic Robert Jensen finds patriarchy and white supremacy in porn

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Journalist-political activist-social critic Robert Jensen is the prickly conscience for a narcissistic Addict Nation that lusts after ever more. More resources. More power. More money. More toys. More sex. The tenured University of Texas at Austin associate professor organizes, agitates, reports, gives talks, writes. Oh, does he write.

He’s the prolific author of books-articles challenging the status quo of privileged white males, of which he’s one. He believes white patriarchal systems of power and predatory capitalism do injury to minorities through racist, sexist, often violent attitudes and actions. His critiques point out the injustice of a white male domination matrix that dehumanizes black men and objectifies-subordinates women.

We’re talking serious oppression here.

As an academic trained in critical thinking and radical feminism, his work rings with polemical fervor but refrains from wild rant or didactic manifesto. Agree or not, it’s hard not to admire his precise, well-reasoned arguments that persuasively connect the dots of an elite ruling class and its assumed supremacy.

He’s presenting the keynote address at a Sept. 22 Center for Human Diversity workshop in Omaha. His topic, “The Pornographic Mirror: Facing the Ugly Realities of Patriarchy and White Supremacy,” is one he often takes up in print and at the podium. His analysis, he said, is based on years studying the porn industry, whose misogynistic, racist products express “men’s contempt and hatred of women.”

Porn, he said, routinely depicts such stereotypes as “the hot-blooded Latina, the demure Asian geisha girl, the animalistic black woman and the hypersexualized black male.” Racially-charged code words — ebony, ivory, nubian, booty, jungle, ghetto, mama, chica, spicy, exotic — market these materials.

He said most interracial porn features black men having sex with white women, which he considers odd given that historically the majority culture’s posited black males as threats to the purity of white women. Why then would an “overwhelmingly white” audience want to view these portrayals?

Jensen suggests what’s at work is an “intensification” of “the core dynamic of male domination and female subordination.” Thus, he said, “by ‘forcing’ white women to have sex with black men, the ultimate sort of demonized man in this culture, it’s intensifying the misogyny and racism” behind it all. “That’s why I talk about these two things together, and why pornography is an important cultural phenomenon to study. It tells us something about the world we live in that is very important.”

The mainstreaming of porn as legitimate pop culture is a trend he finds disturbing. The industry, not counting the corollary sex trade, is estimated at $10 billion annually, comparable to other major entertainment industries such as television, film and sports. Jensen said his own students’ acceptance of porn as “just part of the cultural landscape” reflects a generational shift. Porn’s gone from taboo, scandalous, underground to casual lifestyle choice easily accessed via print, video, TV and the Web, where adult fare’s limitless and its content increasingly extreme.

Strip joints, adult book stores, chat lines, hook-up clubs, escort services, porn sites and X-rated channels abound. Sex tourism is a booming business in Third World Nations, where white men exploit women of color. Homemade porn is on the rise. Porn star Jenna Jameson owns cultural capital. Reality TV, cable programs, movies and advertising are, in his estimation, increasingly pornographic. Although careful not to link porn use to behavior, Jensen sees dangers. Sex addiction is a widely recognized disorder whose various forms have porn as a component.

Recreational choice or addictive fix, end point or gateway to overt, criminal acting- out, Jensen makes the case it’s all fodder for an already dysfunctional society.

“This is helping shape a culture which is increasingly cruel and degrading to women, which we should be concerned about,” he said. “If we’re honest with ourselves, even those who want to defend the pornography industry or who use pornography, I think we have to acknowledge the patterns we’re seeing are cause for concern. I can’t imagine how anyone could come to any other conclusion.”

He said it’s an open question how much more pornographers can push the limits before the culture says a collective, “Enough.” Any outcry’s not likely to come as a see-the-light epiphany, he said, but rather in the course of a long-term public education and public policy campaign. Anti-obscenity legal restraints, he said, are difficult now due to vague, weak state and federal laws, The exception is child porn, where strict laws are easily enforced, he said.

He opposes censorship, insisting, “I’m a strong advocate of the First Amendment and Free Speech,” adding current laws could be enforced with sufficient mandate.

“Much of the material were talking about clearly could be prosecuted yet it isn’t,” he said, “which I think reflects that level of cultural acceptance.”

He suggests enough male stakeholders consume, condone or profit from porn/illicit sex that this old boys network gives winking approval behind faux condemnation.

Jensen supports strict local ordinances and aggressive civil actions against adult porn similar to what feminists proposed in the ‘80s. He feels with modifications this approach, which failed legal challenges then, could prove a useful vehicle.

As Jensen notes, concurrent with this-anything-goes era of on-demand porn and sex-for-hire are the repressive strains of Puritanical America that discourage sex ed and open discussion of sex issues. He’d argue that silence on these subjects in a patriarchal, misogynistic society contributes to America’s high incidence of rape, sexual assault, prostitution, STDs, HIV/AIDS and teen pregnancy.

Overturning these trends, he said, begins with public critiques and forums. The Center for Diversity workshop at the Omaha Home for Boys is just such a forum. The 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. event features a wide-range of presenters on how to “Stay Alive” under the pervasive assault of sexism, racism, economic destabilization, domestic violence and pornography. The workshop’s recommended for health care professionals, therapists and social workers.

Check out Jensen’s work on the web site http://uts.cc.utexas.edu/-rjensen/index.html.

Gender equity in sports has come a long way, baby; Title IX activists-advocates who fought for change see much progress and the need for more

Title IX. This often contentious 1972 federal education act is getting more attention then usual these days because the media is taking a reflective look back on the impact it’s had over its 40 year lifespan. I’m doing the same with this article, which will soon appear in The Reader (www.thereader.com). Because I reside in Omaha, Neb. and The Reader is an Omaha news weekly my story looks at the implications of Title IX and the context that brought it into being from a local perspective, though I certainly address the nationwide effect the legislation’s had. The real interest for me in doing this story was to try and impress upong readers of a certain age that what is easily taken for granted today in terms of the ubiquitious presence of girls and women’s athletics obscures the fact that things were quite different not so very long ago. Younger readers may be surprised to learn that schools, colleges, and universities had to be compelled to cease discrimination on the basis of sex and to give females the same opportunties as males. What seems natural and common sense today wasn’t viewed in that light just a few decades ago. I end my story with a rhetorical question asked by one of my sources, former coach and athletic director Don Leahy, who said, “Why was it ever different?” My story attempts in a small way to explain why and to describe what the journey for women trying to gain equal opportunity in sports looked like.

Gender equity in sports has come a long way, baby;

Title IX activists-advocates who fought for change see much Progress and the need for more

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Participants in girls and women’s sports today should be forgiven if they take for granted the bounty of athletic scholarships, competitive opportunities, training facilities and playing venues afforded them.

After all, they’ve never known anything else.

Their predecessors from two generations ago or more, however, faced a much leaner landscape. One where athletic scholarships were unheard of or totaled hundreds, not thousands of dollars. A handful of games once comprised a season. Facilities-venues were shared, borrowed or makeshift.

Until 1972 federal Title IX legislation banned discrimination on the basis of sex, educational institutions offered nothing resembling today’s well-funded athletic programs for females. Schools devoted a fraction of the resources, if anything at all, to girls and women’s sports that they earmarked for boys and men’s sports.

Second class citizen treatment prevailed.

Nebraska women’s basketball coach Connie Yori made her mark at Creighton University, where she played and coached at some 11 different “home” sites because the program didn’t have its own dedicated facility.

“We were gypsies in some ways. We just had to figure out places to play,” she says, adding, “That wasn’t that long ago either.”

The gulf between then and are now is vast.

“I mean everything was different,” she says. “The way we traveled – the coaches and student athletes were driving the vans to the games. We as coaches had to regularly clean the facilities we practiced in. That was the norm, there wasn’t anyone else to do it. There’s countless examples. Opportunities to play, scholarship money, modes of travel, recruiting budgets, operations budgets, staff salaries, you name it, it’s escalated. But college men’s athletics has escalated too, so it’s not just the women.

“When I played college basketball there would maybe be 50 to 100 fans in the stands and now I’m coaching games where there’s sell-outs and ticket scalping is going on, and who would have thought that?”

Creighton, Nebraska and UNO have their own women’s hoops and volleyball facilities.

“That’s just kind of what’s happened across the board in women’s athletics in that institutions are more committed to equity, and as well they should be,” says Yori.

Gaps remain. Salaries for women coaches lag behind those for men. And where men routinely coach female athletes, it’s rare that women coach male athletes.

Still, things are far advanced from when women’s athletics got dismissed or marginalized and the very notion of female student-athletes was anathema to all but a few enlightened administrators and athletics officials.

In that proto-feminist era the so-called “weaker sex” was discouraged from athletics. Girls and women were considered too delicate to play certain, read: male, sports. Besides, it wasn’t feminine or ladylike to compete. Schools routinely said they could not justify women’s programs because they’d never pay for themselves. Consequently, the idea of giving females the same chances as males was met with paternalistic, patronizing objections. This despite the fact virtually all men’s programs lose money and only survive thanks to donations and to subsidies from student fees and revenue producing major sports.

Former Creighton softball coach Mary Higgins bought the rationale until realizing the contradiction

“I just remember thinking, ‘Well of course we don’t have women’s athletics, we can’t make any money, no one will come.’ And then it was like the light went on – ‘Well, wait a minute, the baseball team doesn’t make any money, they don’t have any people in the stands, then how come they have it and we don’t?'”

When people like Higgins began questioning tired old assumptions and asking for their fair share of amenities there was push back, including from men’s coaches protecting their turf.

“Well, you start with the fact that people don’t like change, period,” says former University of Nebraska at Omaha chancellor Del Weber.

With institutional support virtually nonexistent at the collegiate level, the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women evolved into the main national governing-sanctioning body. Meanwhile, the NCAA actively ignored, then opposed inroads made by women. When school presidents and NCAA officials saw the hand writing on the wall and, some argue, the profits to be made from championship events, women’s athletics fell under the NCAA’s aegis in the early 1980s.

The real impetus for change may simply have been demographic. As women became the majority population, more entered college. Today, women account for the majority enrollment at Creighton and UNO.

Where the benefits of athletic competition (improved self-esteem, leadership skills development, higher graduation rates, et cetera) were once anecdotal, they eventually became measurable.

As far as defining moments, says Higgins, “the linchpin for our programs to grow was getting scholarships. Once we had scholarships we could go get the players.” That’s when the real gains occurred.

“The AIAW got things launched and then I think we got more sophisticated with the NCAA and a lot more money became available. It was a positive thing for growth but that was a painful transition.”

UNO associate athletic director Connie Claussen began women’s athletics there in 1969 as volunteer softball coach. She soon added volleyball and basketball. “I didn’t ask anyone, I just did it,” she recalls. All three sports shared the same set of uniforms. The teams practiced and played in a quonset hut. The equipment room was the trunk of her car. There was no budget, only donations scrounged from sympathetic boosters. Similar limitations applied at Creighton. Nebraska enjoyed a decided facilities advantage. For a time small schools could hang with big schools as everyone started from scratch and had no scholarships available.

Even after Title IX passed, says Claussen “it took several years for it really to have an effect on most athletic programs,” and then only with some prodding. In the case of UNO the Chancellor’s and Mayor’s Commissions on the Status of Women brought pressure. Even the U.S. Office of Civil Rights got involved at the behest of parents Mary Ellen Drickey and Howard Rudloff.

“What sticks out in my mind is that in our old gym they had hours set aside for when the women could come in,” says Higgins. “You think about that now and it just sounds ludicrous but that’s just what it was. The women could come in I believe Sunday and Wednesday nights because God forbid they sweat or show any effort.”

Peru State College basketball coach Maurtice Ivy excelled at the high school, collegiate and pro levels but when she was learning the game as a youth in the 1970s there was no exposure to girls or women’s hoops.

“I didn’t really see women playing, and so the person I watched play and I kind of emulated my game after was Dr. J.”

As an Omaha youth Ivy and other inner city girls developed their skills as Hawkettes, the state’s first select basketball team run by the late Forrest Roper. Richard Nared’s Midwest Striders track program impacted generations of girls, including Ivy and her younger sister Mallery, who set several state records. The sisters’ father was among the first local coaches to offer girls the opportunity to play football.

Fastpitch whiz Ron Osborn organized a statewide club softball association as a forum for girls to play in and as a showcase to convince schools they should start their own softball teams.

Today, girls club teams are everywhere.

Grassroots pioneers worked independently of Title IX to bring about change. Ivy thinks of them and graduates like herself as “soldiers” in the women’s athletics movement.

But there’s no mistaking Title IX, whose enforcement has been upheld in countless legal findings, is the bedrock equal opportunity protection upon which girls and women’s athletics rests. By compelling schools receiving federal assistance to uphold gender equity it’s propelled the explosion of women going to college and the exponential growth of girls and women’s athletics. It’s meant a dramatic increase in the infrastructures supporting female student-athletes and a proportionate increase in the number of participants.

“You went from nothing to everything,” is how former UNO and Creighton athletic director and now UNO associate athletic director Don Leahy describes its impact.

“To me, it standardized and normalized athletics,” says Higgins. “Now it’s just expected.”

Institutions found not complying with Title IX are forced to take corrective action under penalty of court-ordered monetary damages.

Nebraska’s been a battleground for some notable Title IX actions, including a 1995 lawsuit brought by Naomi Friston against the Minden Public School District for scheduling girls games at off times compared to boys’ games. Creighton University graduate Kristen Galles, who successfully represented the Friston case, is now one of the nation’s leading Title IX and gender equity attorneys.

Some school districts, colleges, universities and states were more progressive than others early on. For example, where Iowa embraced girls high school athletics decades before Title IX neighboring Nebraska dragged its feet.

Yori, an Iowa girls athletics legend, says, “I feel like I grew up in almost the perfect place during my era to be a female athlete because Iowa was ahead of its time in regards to the support of girls athletics.” She says the late Iowa Girls Athletics Association president, E. Wayne Cooley, “found ways to place girl athletes on a pedestal.”

Not so much in Nebraska.

“When I crossed the river from Iowa to Nebraska during the early 1980s,” Yori says, “I saw a really different climate for girls athletics here. There was definitely a difference in the commitment level. I mean, there just weren’t opportunities. It’s been great to see how much progress we’ve made in Nebraska and now the two states are on level playing fields in my mind.”

At the collegiate level some Nebraska institutions did take the lead, including John F. Kennedy College in Wahoo and Midland University in Fremont, both of which built dominant women’s athletic programs in the ’70s. Recently retired Midland basketball coach Joanne Bracker was an inaugural member of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

Under Claussen UNO won the 1975 AIAW Women’s College World Series, one of several national titles won by UNO women’s teams. Claussen and CU’s Higgins helped grow college softball, serving on AIAW and NCAA committees and leading their respective schools in hosting more than a dozen CWS championships, which Higgins says was “huge” in legitimizing women’s sports here and beyond.

The late Omaha Softball Association guru Carl Kelly and College World Series Inc. chairman Jack Diesing Sr., along with corporate donors, helped sponsor the women’s tournament.

The start of the 1980s saw NU women’s sports emerge. The volleyball program began its run of excellence under Terry Pettit. Gary Pepin’s track program shined with superstar Merlene Ottey. Angela Beck’s basketball program reached new heights with Maurtice Ivy. NU softball began making noise.

By the early ’90s, a full complement of women’s sports was in place wherever you looked, whether big public schools like NU, smaller private schools like CU or then-Division II UNO.

None of it would have happened without activists pressing the cause of female student athletes. Along the way Title IX and its supporters met resistance, including court challenges.

“I think there’s a lot of women and men who made a huge difference for the young women of this generation,” says Yori. “Connie Claussen and Mary Higgins were very much advocates for change. There were a lot of battles fought – in offices, in meeting rooms, and even legally in courtrooms. There were people that got fired for voicing their opinions and became the sacrificial lambs because of that. There were a lot of people who didn’t want change and didn’t want to give women the opportunity they are now being given.

“You know, we still need to fight for it, but there’s not such a gap as there was.”

Higgins says the trailblazers of modern women’s athletics were “people who just had a burning passion to make this happen. It consumed me, I know it consumed my colleagues. It’s like, ‘We’ll do whatever it takes. We’ll figure it out, we’ll find a way.”

Parents played roles, too, as coaches, administrators, boosters.

“I do think dads and their concern for their daughters had a major impact, and that was absolutely the case at Creighton,” says Higgins. “It wasn’t Title IX telling Creighton they had to do it. Title IX was happening at the same time but our then-assistant athletic director, the late Dan Offenburger, kind of led the charge. He coached our very first softball team. He didn’t have time to do it, we didn’t have any money, we didn’t even have a shoestring. But he got it going because it was the right thing to do. Plus, he had three daughters and he was motivated to create opportunities for them.

“I’m sure there are stories like that all over.”

As near as UNO, where Don Leahy says he supported women’s athletics not only because “I thought it had to be done” but because “I had a daughter who played sports.” There were also a wife and mother to answer to at home.

Leahy says the coaches he worked with at UNO and Creighton “fought diligently for their programs but at the same time they maintained a common sense that made it possible for this thing to develop. We talked and we gradually worked through these things and I think that made a big difference.”

“This stuff did not come easy,” says Del Weber, who approved the early road map for women’s athletics at UNO laid out by Leahy and Claussen and the gender equity program that they and former athletic director Bob Danenhauer devised.

Ramping up meant serious dollars. Leahy says when it became clear accommodating women’s athletics was a new reality “the first thing that came up was – how are we going to pay for this?”

Current Creighton athletic director Bruce Rasmussen, who coached CU’s women’s basketball team, recalls, “We didn’t have enough resources to properly compete just with our mens’ programs and now we had the burden of essentially doubling our athletic department. It was, ‘How do we balance what we can do with what we should do?’ And there was a lot of stress across the country. Women’s athletics completely changed the dynamics of universities and how were they going to support a full athletic department. So there was a lot of tension and trauma going on.”

“And funding it is not just a matter of we’re going to give them x number of dollars,” says Rasmussen, “but it’s facilities, it’s staffing, it’s scholarships, recruiting, traveling, equipment…”

At Creighton as anywhere, says Rasmussen, “we’re asked to provide not only an athletic program but also to be fiscally responsible as a department and as a program. So when it comes to asking for more money, especially when you’re running at a deficit, there’s certainly friction. I think factions of the faculty felt every dollar that went to athletics was a dollar out of their pocket.”

By the ’90s, girls and women’s sports were a given. By the 2000s, they’re as much a part of the culture as boys and men’s sports. Some professional women’s sports leagues flourish. Icons have even emerged: Pat Summit, Lisa Leslie, Florence Griffith-Joyner, the Williams sisters, Jackie Joyner-Kersee, Brittney Griner.

“To turn that around was a seismic shift,” says Higgins.

“In a short time things really have come a long way,” says Claussen, who hastens to add, “But it took a long time to get” the opportunity.

Once spare media coverage has increased to the point that it’s commonplace if still a trickle of what males get.

“Hopefully we’ll continue getting more and more and that’s where the NCAA plays a big part in getting those television contracts,” says Claussen. “All that’s going to help increase the interest.”

The sustainability of athletic programs is an increasingly difficult proposition for schools struggling to keep pace with peers in a competitive arena of ever rising costs.

“At some point women’s athletics has to generate enough money to pay for itself because until it does we’re not going to get where we need to be,” says Rasmussen. “In men’s basketball we wouldn’t have the budget or spend the money on salaries we do if weren’t generating that, and we’ve got to move to the point where on the women’s side we’re generating realistic revenues. And the key to that is having generations of females who played sports, understand the value of sports and are willing to make a commitment to those sports.

“We don’t exist as an athletic department without people making a commitment to us.”

Creighton’s state-of-the-art athletic center and arena for volleyball and women’s basketball resulted from multi-million dollar gifts by donors Wayne and Eileen Ryan and David Sokol. Rasmussen says having coached women’s sports helps him effectively make the case for them when he asks for support.

In 1986 Claussen inaugurated the UNO Women’s Walk, now the Claussen-Leahy Run/Walk, which has raised $4 million-plus for women’s athletics.

NU’s men’s and women programs have some of the best facilities in the U.S. thanks to mega donations.

The strong sisterhood of girls and women’s sports that exists today is built on decades of sacrifice and perseverance. Ivy wants her athletes to know the history. It’s why she says she tells them about “who paved some of the way and the different struggles people had to endure so that we can have.” Yori does the same with her players because she wants them to know “where we come from as a sport.”

“There were groundbreakers and pioneers before us who made a huge impact on the opportunities young people have today,” Yori says. “Women of previous generations were not given opportunities and so it’s neat to see when they are given opportunities how much they can take advantage of that.”

“Why was it ever different?” asked Leahy. Why indeed.

Related articles

- From the series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness – Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Sports of The Times: Title IX Has Not Given Black Female Athletes Equal Opportunity (nytimes.com)

- From ESPN’s celebration of Title IX’s 40th: (womenshoopsblog.wordpress.com)

- Don’t call us tomboys anymore (nbcsports.msnbc.com)

- Title IX turns 40 (dailykos.com)

Omaha’s Malcolm X Memorial Foundation Comes into its Own, As the Nonprofit Eyes Grand Plans it Weighs How Much Support Exists to Realize Them

African-Americans from the town where I live, Omaha, Neb., are often amused when they travel outside the state, especially to the coasts, and people they first meet discover where they are from and invariably express surprise that black people live in this Great Plains state. Yes, black people do live here, thank you very much. They have for as long as Nebraska’s been a state and Omaha’s been a city, and their presence extends back even before that, to when Nebraska was a territory and Omaha a settlement. Much more, some famous black Americans hail from here, including musicians Wynonie Harris, Buddy Miles, Preston Love Sr. and Laura Love, Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson, Hall of Fame running back Gale Sayers, Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Rodgers, the NFL’s first black quarterback Marlin Briscoe, actress Gabrielle Union, actor John Beasley, producer Monty Ross, Radio One-TV One magnate Cathy Hughes, and, wrap your mind around this one, Malcolm X. That’s right, one of the most controversial figures of the 20th century is from this placid, arch conservative and, yes, overwhelmingly white Midwestern city. He was a small child when his family moved away but the circumstances that propelled them to leave here inform the story of his experience with intolerance and bigotry and help explain his eventual path to enlightenment and civic engagement in the fight to resist inequality and injustice. Though the man who was born Malcolm Little and remade himself as Malcolm X had little to do with his birthplace after leaving here and going on to become a national and international presence because of his writings, speeches, and philosophies, some in Omaha have naturally made an effort to claim him as our own and to perpetuate his legacy and teachings. Much of that commemorative and educational effort is centered in the work of the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation based at the North Omaha birthsite of the slain civil rights activist. The following story, soon to appear in The Reader (www.thereader.com), gives an overview of the Foundation and recent progress it’s made. Rowena Moore of Omaha had a dream to honor Malcolm X and she led the way acquiring and securing the birthsite and ensuring it was granted historic status. After her death a number of elders maintained what she established. Under Sharif Liwaru’s dynamic leadership the last eight years or so the organization has made serious strides in plugging MXMF into the mainstream and despite much more work to be done and money to be raised my guess is that it will someday realize its grand plans, and perhaps sooner than we think.

Omaha’s Malcolm X Memorial Foundation Comes into its Own, As the Nonprofit Eyes Grand Plans it Weighs How Much Support Exists to Realize Them

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to appear in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Self-determination by any means necessary.

The notorious sentiment is by Malcolm X, whose incongruous beginnings were in this conservative, white-bread city. Not where you’d expect a revolutionary to originate. Then again, his narrative would be incomplete if he didn’t come from oppression.

Born Malcolm Little, his family escaped persecution here when he was a child. His incendiary intellect and enlightenment were forged on a transformative path from hustler to Muslim to militant to husband, father and humanist black power leader.

As it does annually, the Omaha-based Malcolm X Memorial Foundation commemorates his birthday May 17-19. Thursday features a special Verbal Gumbo spoken word open mic at 7 p.m. hosted by Felicia Webster and Michelle Troxclair at the House of Loom.

Things then move to the Malcolm X Center and birthsite. Friday presents by the acclaimed spoken word artist and author Basheer Jones, plus The Wordsmiths, at 7 p.m.

On Saturday the African Renaissance Festival unfolds noon to 5 p.m. with drummers, native attire, storytelling, face painting and Malcolm X reflections. Artifacts from the recently discovered Malcolm “Shorty” Jarvis collection of Malcolm X materials will be displayed. The late musician was a friend and criminal partner of Malcolm Little’s before the latter’s incarceration and conversion to Islam.

It’s a full weekend but hardly the kind of community-wide celebration, much less holiday, devoted to Martin Luther King Jr.

“I tell people, you may still not like Malcolm X, you may have a problem with a revolutionary. Martin was a revolutionary and maybe you came to love him. But I do want you to know brother Malcolm’s whole story and where he came from,” says MXMF president Sharif Liwaru.

“A big portion of what we do is about the legacy of Malcolm X. We go into communities, schools and other speaking environments and we educate people about Malcolm X, what he meant, what his impact was on society. Sometimes people walk away with a different level of respect for him. Sometimes they walk away having a better understanding.”

Using the tenets of Malcolm X, the foundation promotes civic engagement as a means foster social justice.

Nearly a half-century since Malcolm X’s 1965 assassination, he remains controversial. The Nebraska State Historical Society Commission has denied adding him to the Nebraska Hall of Fame despite petition campaigns nominating him. Few schools have curricula about the slain civil rights activist.

From its 1971 start MXMF has struggled overcoming the rhetoric around its namesake. The late activist Rowena Moore founded the grassroots nonprofit as a labor of love. She secured the North O lot where the razed Little home stood and where she once lived. Fueled by her dream to build a cultural-community center, MXMF acquired property around the birthplace. The site totals some 11 acres.

By the time she passed in 1998 the piecemeal effort had little to show save for a state historical marker. Later, a parking lot, walkway and plaza were added. Other than clearing the land of overgrowth and debris, the property was long on promise and short on fruition, awaiting funds to catch up with vision.

Without a building of its own, MXMF events were held alfresco on-site from spring through fall and at rotating venues in the winter. “We felt a little homeless,” says Liwaru. “We were very creative and did a whole lot without a building but we didn’t have a place to showcase and share that.” All those years of making do and staying the course have begun paying off. Hundreds of thousands of dollars in public-private grant monies have been awarded MXMF since 2009. Other support’s come from the Douglas County Visitors Improvement Fund, the Iowa West Foundation, the Sherwood Foundation, the Nebraska Arts Council and the Nebraska Humanities Council.

Most notably a $200,000 North Omaha Historical grant allowed MXMF to acquire its first permanent indoor facility, an adjacent former Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall at 3463 Evans Street, in 2010. Now renamed the Malcolm X Center, it hosts everything from lectures, films, plays, community forums, receptions and fundraisers to a weekly Zumba class to a twice monthly social-cultural-history class. Annual Juneteenth and Kwanzaa celebrations occur there.

Most notably a $200,000 North Omaha Historical grant allowed MXMF to acquire its first permanent indoor facility, an adjacent former Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall at 3463 Evans Street, in 2010. Now renamed the Malcolm X Center, it hosts everything from lectures, films, plays, community forums, receptions and fundraisers to a weekly Zumba class to a twice monthly social-cultural-history class. Annual Juneteenth and Kwanzaa celebrations occur there.MXMF conducts some longstanding programs, including Camp Akili, a residential summer leadership program for youth ages 14-19, and Harambee African Cultural Organization, an outreach initiative for citizens returning to society from prison.

The center is a community gathering spot and bridge to the wider community. Liwaru says it gives the birth site a “public face” and “front door” it lacked before, thus attracting more visitors. Besides hosting MXMF activities the center’s also used by outside groups. For example, Bannister’s Leadership Academy classes and Sudanese cultural events are held there.

“We’re very proud to be a community resource. It legitimizes us as an organization to have that space available. It makes a difference with the confidence of the volunteers involved.””

A recent site development that’s proved popular is the Shabazz Community Garden, where a summer garden youth program operates.

The surge of support is not by accident. The birthsite’s pegged as an anchor-magnet in North Omaha Revitalization Village plans and Liwaru says, “We definitely see ourselves as a viable part of it.” North Omaha Development Project director Ed Cochran, Douglas County Commissioner Chris Rodgers and Omaha City Councilman Ben Gray have helped steer resources its way.

Attitudes about Malcolm X have softened to the point even the prestigious Omaha Community Foundation awarded a $20,000 capacity building grant. Despite working on the margins, Liwaru says “investors could see our mission and work ethic and they supported that.”

Since obtaining its own facility, Liwaru says, “I find more people speaking as if our long-range plans are possible.” Those plans call for an amphitheater and a combined conference-cultural center.

For most of its life MXMF’s subsisted on small donations. When the building grant stipulated $50,000 in matching funds, says Liwaru, “”it was really the culmination of a lot of little gifts that made it happen.”

The all-volunteer organization depends on contributions of time, talent and treasure from rank-and-file supporters.

“We believe a little bit of money from a lot of people is beneficial,” says Liwaru. “Sometimes that meant we were probably working harder than the next organization that may be able to go to one or two people to get their funds, but it certainly makes us accountable to more people. We’re ultimately responsible to our community because we have so many community members contribute.

“Our organization belongs to the community. The people get the say.”

In tangible, brick-and-mortar terms, the foundation hasn’t come far in 40 years, but all things considered Liwaru’s pleased where it’s at.

“We’ve made a lot of progress. One of the things that makes me confident we’ve turned this corner is there’s still this strong commitment, there’s still passionate people involved.”

Veteran board members and community elders Marshall Taylor and Charles Parks Jr., among others, have carried the torch for decades. “They bring experience and wisdom,” says Liwaru. He adds, “We’ve added strong young people to our board like Kevin Lytle (aka Self Expression), and Lizabet Arellano, who bring a lot of new ideas and a passion for carrying out change in this urban environment.”

However, if MXMF is to become a major attraction a giant leap forward is necessary and Liwaru’s unsure if the support’s there right now.

“Everybody wants sustainability in terms of stable funding and revenue. We put out a lot of funding proposals at the end of last year. Few were approved. We got a lot of nos. Most funders don’t say why. We don’t know if it’s because they’re not wanting to be affiliated with Malcolm X or if it’s not understanding what we do as an organization or if they don’t think we can see projects through to the end.”

He can’t imagine it’s the latter, saying, “Anybody who knows us knows we’re persistent and that what we talk we follow through with.”

His gut tells him the organization still encounters patriarchal, political barriers.

“We always feel we have to come in proving ourselves. I always come in and explain we’re not a terrorist organization or a splinter cell. Most of what we get is a lot of encouragement but it’s a pat on the back and ‘I hope that you guys do really well with that’ versus, ‘I can help.’ I think one of the challenging things is we’re not sure what people think of us. There are many who aren’t sure which Malcolm we’re celebrating.

“If an organization is just completely not interested in covering anything related to Malcolm X it’d be nice to know. So the question from me to philanthropists out there is, ‘What do you think about the Malcolm X foundation and what we do? Do you see it as a worthy cause? What are we missing?”

Answers are important as MXMF is S100,000 away from finishing its planning phase and millions away from realizing the site’s full build-out. It could all take years. None of this seems to discourage MXMF stalwarts.

“We are willing to sacrifice and work diligently for however long it takes,” says Lizabet Arellano. Fellow young blood board member Kevin Lytle takes hope from the momentum he sees. “There’s more and more people at events and rallies and different things we do. People are finally starting to recognize and take pride in the fact Malcolm X was born here,” he says. “We have to start somewhere, and that’s a start. People know that we’re here and that we’re representing something beneficial to the community.”

Liwaru sees a future when major donors ouside Nebraska help the MXMF site grow into a regional, national, even international mecca for anyone interested in Malcolm X.

Besides a House of Loom cover charge, the weekend MXMF events are free. For details, visit http://www.malcolmxfoundation.org or the foundation’s Facebook page.

Related articles

- A Brief History of Omaha’s Civil Rights Struggle Distilled in Black and White By Photographer Rudy Smith (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Malcolm X bio doubts activist was served justice (cbsnews.com)

- Malcolm X artifacts unearthed: Police docs and more found among belongs of ‘Shorty’ Jarvis (thegrio.com)

- Blacks of Distinction II (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Synergy in North Omaha Harkens a New Arts-Culture District for the City (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Carolina Quezada leading rebound of Latino Center of the Midlands

The organizations that make a difference in a community of any size are legion and I am always struck by how little I know about the nonprofits impacting people’s lives in my own city. I often find myself assigned to do a story on such organizations and by the time I’m done I feel I have a little better grasp then I had before of what goes on day in and day out in organizations large and small that serve people’s social service and social justice needs. One such institution is the Latino Center of the Midlands, which I profile here along with its executive director Carolina Quezada, who came on board last year in the midst of a tough time for the former Chicano Awareness Center. She and I are happy to report the organization is back on track and that’s good news for the community it serves.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

Carolina Quezada took the reins of the Latino Center of the Midlands last August in the wake of its substance abuse program losing funding, executive director Rebecca Valdez resigning and the annual fund raiser being canceled. Despite the travails, Quezada found a resilient organization.

Overcoming obstacles has been par for the course since community organizers started the former Chicano Awareness Center in 1971 to address the needs of underserved peoples. Its story reminds her of the community initiatives she worked for in her native East Los Angeles. She never intended leaving Calif. until going to work for the Iowa West Foundation in 2009. Once here, she found similar challenges and opportunities as she did back home.

“I’ve come full circle. I see so much of what I encountered growing up in L.A. which is parents with very low levels of education wanting their kids to succeed, graduate high school and go to college but often no plan to get them there.,” she says.

“South Omaha is like this microcosm of East L.A. The moment I drove down 24th Street the first time I thought, This is like Whittier Blvd. I felt an instant connection. There’s so much overlap. This sense of close relationship with the grassroots, the sense of community, and how the organization has its beginnings in activism, in that voice of the community. It’s so indicative of how nonprofits in Latino communities have their base in the grassroots voice and in services and issues having to do with social justice.”

Forged as the center was in the ferment of unrest, she’s hardly surprised it’s persevered.

“I am pretty struck by how the agency continues to respond,. It’s always been responsive to what that emerging need is. I think it’s just an inherent part of its DNA.”

She acknowledges the center was rocked by instability in 2011.

“Currently we are in the process of trying to strengthen that stability. Last year was a very difficult year for the agency. There was a transition in leadership, there was funding lost. The agency was still operating but in a very low key way, and I give credit to the board members and staff in making sure the doors remained open. Their passion continues to drive what we do every day.

“One of our greatest core competencies is that love for community and that connection to our people. When people come through our doors they are greeted by people who look like them and speak their language. It’s their culture. I’m very proud the Latino Center keeps that piece very close to its heart.”

She says in this era of escalating costs and competition for scarcer resources, nonprofits like hers must be adaptable, collaborative and creative “to survive.

“There is much more a need to be strategic. It’s not just about being a charity. Now it’s about being an institution that takes on a lot more of the business model and looks at diversifying funding sources.”

In her view Nebraska offers some advantages.

“Because the economy is better here the environment for nonprofits is a little better. You have funders who are strong, engaged, committed and very informed. I think a lot of it has to do with the strength of their foundations and the culture of the Midwest. People really care about getting involved and building community.

“Last year was very tough. Not having the annual fundraiser really hurt the agency. But there’s been some renewed investment in the organization from funders. There is a very strong interest in collaborating with Latino Center of the Midlands from other organizations and funders and community leaders.”

Omaha’s come to expect the agency being there.

“Because of our 40-plus year history people know to come to us. We get a lot of walk-ins. We convene large groups of people here on a regular basis because of the wide array of classes we offer. We are still making an impact in parent engagement and basic adult education. We work with parents having a difficult time getting their kids to attend school on a regular basis.

“But we also deal with all sorts of other issues that come through our doors. We get requests for assistance with immigration, other legal issues, social services. We do referrals for all sorts of things. We’ve also started inviting partners to come offer their services here – WCA, OneWorld Community Health, UNMC’s Center for Health Disparities, Planned Parenthood. So we become a very attractive partner to other organizations that want to partner in the Latino community.

“We cannot do our work well if we’re not building strong partnerships with others.”

She says she and her board “are formulating some specific directions we want to take the organization in” with help from the Omaha Community Foundation‘s capacity building collaborative. “We have to look at those support networks for how we build capacity and we’re very fortunate to count on the support of the Community Foundation. We’re working with their consultants to look at our strategic initiatives, fund raising, board recruitment, programs and projects. We’re looking at where our impact has been and what the needs are in the community.”

She feels the center is well poised for the future.

“We realize we have a lot of work to do but there’s a lot of optimism and energy about where the agency could go.”

Best of all, the annual fund raiser returns July 23. “I’m so happy it’s going to be back,” says Quezada. Check for details on that and ongoing programs-services at http://www.latinocenterofthemidlands.org.

Related articles

- Evangelina “Gigi” Brignoni Immerses Herself in Community Affairs (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jose and Linda Garcia Find a New Outlet for their Magnificent Obsession in the Mexican American Historical Society of the Midlands (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- “Paco” Proves You Can Come Home Again (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- African Presence in Spanish America Explored in Three Presentations (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- PBS WIll Air New Documentary On Latinos (huffingtonpost.com)

A brief history of Omaha’s civil rights struggle distilled in black and white by photographer Rudy Smith

Rudy Smith was a lot of places where breaking news happened. That was his job as an Omaha World-Herald photojournalist. Early in his career he was there when riots broke out on the Near Northside, the largely African-American community he came from and lived in. He was there too when any number of civil rights events and figures came through town. Smith himself was active in social justice causes as a young man and sometimes the very events he covered he had an intimate connection with in his private life. The following story keys off an exhibition of his work from a few years ago that featured his civil rights-social protest photography from the 1960s. You’ll find more stories about Rudy, his wife Llana, and their daughter Quiana on this blog.

A brief history of Omaha’s civil rights struggle distilled in black and white by photographer Rudy Smith

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Coursing down North 24th Street in his car one recent afternoon, Rudy Smith retraced the path of the 1969 summer riots that erupted on Omaha’s near northside. Smith was a young Omaha World-Herald photographer then.

The disturbance he was sent to cover was a reaction to pent up discontent among black residents. Earlier riots, in 1966 and 1968, set the stage. The flash point for the 1969 unrest was the fatal shooting of teenager Vivian Strong by Omaha police officer James Loder in the Logan Fontenelle Housing projects. As word of the incident spread, a crowd gathered and mob violence broke out.

Windows were broken and fires set in dozens of commercial buildings on and off Omaha’s 24th Street strip. The riot leapfrogged east to west, from 23rd to 24th Streets, and south to north, from Clark to Lake. Looting followed. Officials declared a state of martial law. Nebraska National Guardsmen were called in to help restore order. Some structures suffered minor damage but others went up entirely in flames, leaving only gutted shells whose charred remains smoldered for days.

Smith arrived at the scene of the breaking story with more than the usual journalistic curiosity. The politically aware African-American grew up in the black area ablaze around him. As an NAACP Youth and College Chapter leader, he’d toured the devastation of Watts, trained in nonviolent resistance and advocated for the formation of a black studies program at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where he was a student activist. But this was different. This was home.

On the night of July 1 he found his community under siege by some of its own. The places torched belonged to people he knew. At the corner of 23rd and Clark he came upon a fire consuming the wood frame St. Paul Baptist Church, once the site of Paradise Baptist, where he’d worshiped. As he snapped pics with his Nikon 35 millimeter camera, a pair of white National Guard troops spotted him, rifles drawn. In the unfolding chaos, he said, the troopers discussed offing him and began to escort him at gun point to around the back before others intervened.

Just as he was “transformed” by the wreckage of Watts, his eyes were “opened” by the crucible of witnessing his beloved neighborhood going up in flames and then coming close to his own demise. Aspects of his maturation, disillusionment and spirituality are evident in his work. A photo depicts the illuminated church inferno in the background as firemen and guardsmen stand silhouetted in the foreground.

The stark black and white ultrachrome prints Smith made of this and other burning moments from Omaha’s civil rights struggle are displayed in the exhibition Freedom Journeynow through December 23 at Loves Jazz & Arts Center, 2512 North 24th Street. His photos of the incendiary riots and their bleak aftermath, of large marches and rallies, of vigilant Black Panthers, a fiery Ernie Chambers and a vibrant Robert F. Kennedy depict the city’s bumpy, still unfinished road to equality.

The Smith image promoting the exhibit is of a 1968 march down the center of North 24th. Omaha Star publisher and civil rights champion Mildred Brown is in the well-dressed contingent whose demeanor bears funereal solemnity and proud defiance. A man at the head of the procession holds aloft an American flag. For Smith, an image such as this one “portrays possibilities” in the “great solidarity among young, old, white, black, clergy, lay people, radicals and moderates” who marched as one,” he said. “They all represented Omaha or what potentially could be really good about Omaha. When I look at that I think, Why couldn’t the city of Omaha be like a march? All races, creeds, socioeconomic backgrounds together going in one direction for a common cause. I see all that in the picture.”

Images from the OWH archives and other sources reveal snatches of Omaha’s early civil rights experience, including actions by the Ministerial Alliance, Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties, De Porres Club, NAACP and Urban League. Polaroids by Pat Brown capture Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. on his only visit to Omaha, in 1958, for a conference. He’s seen relaxing at the Omaha home of Ed and Bertha Moore. Already a national figure as organizer of the Birmingham (Ala.) bus boycott and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he’s the image of an ambitious young man with much ahead of him. Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, Jr. joined him. Ten years later Smith photographed Robert F. Kennedy stumping for the 1968 Democratic presidential bid amid an adoring crowd at 24th and Erskine. Two weeks later RFK was shot and killed, joining MLK as a martyr for The Cause.

Omaha’s civil rights history is explored side by side with the nation’s in words and images that recreate the panels adorning the MLK Bridge on Omaha’s downtown riverfront. The exhibit is a powerful account of how Omaha was connected to and shaped by this Freedom Journey. How the demonstrations and sit-ins down south had their parallel here. So, too, the riots in places like Watts and Detroit.

Acts of arson and vandalism raged over four nights in Omaha the summer of ‘69. The monetary damage was high. The loss of hope higher. Glimpses of the fall out are seen in Smith’s images of damaged buildings like Ideal Hardware and Carter’s Cafe. On his recent drive-thru the riot’s path, he recited a long list of casualties — cleaners, grocery stores, gas stations, et cetera — on either side of 24th. Among the few unscathed spots was the Omaha Star, where Brown had a trio of Panthers, including David Poindexter, stand guard outside. Smith made a portrait of them in their berets, one, Eddie Bolden, cradling a rifle, a band of ammunition slung across his chest. “They served a valuable community service that night,” he said.

Most owners, black and white, never reopened there. Their handsome brick buildings had been home to businesses for decades. Their destruction left a physical and spiritual void. “It just kind of took the heart out of the community,” Smith said. “Nobody was going to come back here. I heard young people say so many times, ‘I can’t wait to get out of here.’ Many went away to college and never came back. That brain drain hurt. It took a toll on me watching that.”

Boarded-up ruins became a common site for blocks. For years, they stood as sad reminders of what had been lost. Only in the last decade did the city raze the last of these, often leaving only vacant lots and harsh memories in their place. “Some buildings stood like sentinels for years showing the devastation,” Smith said.

His portrait of Ernie Chambers shows an engaged leader who, in the post-riot wake, addresses a crowd begging to know, as Smith said, “Where do we go from here?’

Smith’s photos chart a community still searching for answers four decades later and provide a narrative for its scarred landscape. For him, documenting this history is all about answering questions about “the history of north Omaha and what really happened here. What was on these empty lots? Why are there no buildings there today? Who occupied them?” Minus this context, he said, “it’d be almost as if your history was whitewashed. If we’re left without our history, we perish and we’re doomed to repeat” past ills. “Those images challenge us. That was my whole purpose for shooting them…to challenge people, educate people so their history won’t be forgotten. I want these images to live beyond me to tell their own story, so that some day young people can be proud of what they see good out here because they know from whence it came.”

An in-progress oral history component of the exhibit will include Smith’s personal accounts of the civil rights struggle.

Related articles

- Carole Woods Harris Makes a Habit of Breaking Barriers for Black Women in Business and Politics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Blacks of Distinction II (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Great Migration Comes Home: Deep South Exiles Living in Omaha Participated in the Movement Author Isabel Wilkerson Writes About in Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Part I of a Four-Part Q & A with Pulitzer-Winner Isabel Wilkerson On Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Part II of a Four-Part Series with Pulitzer-Winner Isabel Wilkerson, Author of ‘The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Part III of a Four-Part Q & A with Pulitzer-Winner Isabel Wilkerson on Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Part IV of a Four-Part Q & A with Pulitzer-Winner Isabel Wilkerson on Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Photojournalist Nobuko Oyabu’s Own Journey of Recovery Sheds Light on Survivors of Rape and Sexual Abuse (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Abe Sass: A mensch for all seasons

The following profile I did on Abe Sass reminds me that extraordinary individuals are all around us. He’s married to a dynamo named Rivkah Sass, one of the most honored public librarians in the nation and because of her much feted work in that field she is obstensibly the star of this couple. But as I found out and as I hopefully succeed in sharing with readers like you Abe has a story worth knowing and celebrating too. He’s packed a lot of living into his life and because he’s pursued such a wide range of interests and experiences he’s brushed up against all sorts of historic people and places and events that I trust you will find as compelling as I did.

Abe Sass: A mensch for all seasons

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the Jewish Press

When your wife is a force of nature named Rivkah Sass, a recent national librarian of the year honoree and a much-in-demand public speaker, it could be easy to get overshadowed. The Omaha Public Library director’s dynamic personality can take over a room. Abe Sass doesn’t mind. In fact, he loves the attention Rivkah gets. You see, he’s not only her husband, but her biggest fan.

“Rivkah has an incredibly difficult job and I really believe she’s already changed the world in Omaha. She is committed,” he said.

There’s no real chance of him being lost in her limelight though. He’s every bit as accomplished as she and cuts a larger-than-life figure in his own right. A veteran psychiatric social worker, Sass has worked in several hospitals, he’s consulted school districts and he’s maintained his own private practice. No longer a full-time therapist, he volunteers his services to clients these days.

Sensitive and empathic as he may be, he’s no shrinking violet. He’s a charismatic presence at library activities and events with his warm smile, quick wit, hearty laugh and earthy demeanor. His six-foot-plus height and full beard help him stand out from the crowd, as does his animated demeanor, which flashes from dramatic whisper to basso profundo boom, all spiced with expletives and dollops of Yiddish.

This son of militant, immigrant garment workers in New York grew up a progressive thinker and activist. He was a rank-and-file soldier in the civil rights movement of the 1950s-1960s. He was at the historic march on Washington, D.C. in 1963 when Martin Luther King. Jr. articulated his dream for universal brotherhood. He was a member of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality. He took part in his share of demonstrations on behalf of equality and justice.

He’s never lost his social conscience or political fervor, either. He’s remained engaged wherever he roosts, from the tenements of lower Manhattan to the halls of academia to the psychiatric wards at hospitals in California, Washington and Oregon. In Omaha he’s a familiar figure wherever ideas are exchanged, whether a community forum or a book reading or an art opening.

He often conducts therapy sessions in the mid-town home he and Rivkah inhabit. The couple’s place is an expression of their passions. They’re both lovers of literature, art and discussion. They place high value on friends and family. They do puppetry. They tell stories. They champion the underdog. They support causes. They entertain guests. Fittingly, their home is adorned with books, paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, puppets, photographs of loved ones, mementos, keepsakes and campaign buttons emblazoned with liberal slogans, such as “Fight Racism” and “Swords and Plowshares.”

“Everything we do and have done is on our walls,” said Sass, gesturing to the overflow of objects about him in his living room.

He noted a small figurine of a black girl holding a book in one hand and a globe in the other, “which really fits who Rivkah is and who I am,” he said. The figurine is perched at the edge of a table atop which are also an old camera, a pair of cut-outs from artist Wanda Ewing’s black pin-up series and a button that reads “Black Power.” Sometimes there’s a button with a black hand, a brown hand and a white hand coming together that says “Let Us All Be Good Neighbors.” Taken together, he said, the display “is almost like a snapshot of a world that is and a world we could have. In many ways that represents to me where we need to go and, unfortunately, where we haven’t always been.”

Sass traces his humanist bent to his growing up poor in the Chelsea slums of New York City. He never knew his father, an artist, a presser, and Communist Party member who a year after Abe was born in 1938, went to Europe to try and rescue family only to be “swallowed up in the Holocaust.” His mother, Sylvia, endured “a miserable working life,” but sought much more for herself and her only child.

“All of her contemporaries were militant Jewish garment workers and wherever there was a rally there we were. I was just a kid, but everything they did made crystalline sense to me. It’s through her I met Pete Seeger and Paul Robeson. We would go to places where they were singing. We had a dear friend who was a wonderful militant woman. My mom and I would go with her to like a fraternal gathering place, where they would have speakers, singers. Seeger would come. Robeson would come. It was really cool. One of the major moments for me is when Robeson shook my hand and I felt, wow.”

He said he gained an awareness beyond his years “when we marched in the May Day Parade for working people and we’d get hit by rotten eggs and cabbages and comments like, ‘Go back to Russia’ or Dirty Commie.’” If all the protests he’s been a part of — from fair housing to sane nuclear policy to immigration reform– have taught him anything, he said, it’s that “there are people in this world that just don’t get it. I’m not a pessimist but I believe many people just don’t see there’s a big picture, and I believe one of the things we suffer from — all of us — is we only focus on ‘me.’ It’s dangerous…Unless we really see and feel connections we wind up with a perspective that’s very constricted and myopic.”

Action, not apathy. “We have to reach out and do something for people who need an assist up. It’s like that powerful saying, When they came for him, I didn’t say anything, when they came for her I didn’t say anything, and then when they came for me, nobody said anything. It’s still the same. It hasn’t changed,” he said.

The “cruddy” area he came from offered some valuable lessons on human relations and social conditions. Being the only Jewish kid on his block gave him a sense for what minority really mean.

“We lived in a terrible apartment building on West 18th Street,” now the trendy art neighborhood of New York, he said. “It was a little, dinky three-room apartment. I lived there through my 20s. It was tense and tight and loud and crazy. When you’re Jewish and you grow up in an Irish-Catholic neighborhood you’re an oddball by definition. I was more of an oddball because my aura was a softer aura and the softness not only came from enjoying the sanctuary of the orthodox synagogue I grew up in, but also” from being a reader and an art lover among street kids.

“The kids I was desperately trying to fit into I really had a hard time with, because they were busy kicking other people’s asses and that really was not something I felt comfortable with. And when it came to like stick ball and football and all that shit, nuh-uh, it was like, ‘Oh, get out of here, Abe.’ I was totally useless.”

To survive, he had to find his own schtick.

“Everybody had their thing on the block. You gotta have something to get a rep, OK? My rep was on Sunday nights, when we’d gather on a stoop and I would tell stories to these same kids…just make ‘em up out of my head…and I had them, because I could weave a tale, and I loved it. I shined in that moment.”

At PS 11 Elementary School and at Charles Evans Hughes High School he mixed with Jews, Irish, Italians, African-Americans, Greeks, Asians and practically every other nationality-ethnicity. “It was a potpourri of people,” he said. “You talk about a spectrum, it was all there.”

He fondly recalls the summer camps for “underprivileged children” he attended, and later was a counselor at. They further exposed him to a multi-cultural stew.

“My best friends were always Puerto Rican kids, black kids, Asian kids. I used to drive my poor mother crazy because every summer I’d come home from camp talking like I’m a kid from Harlem. She would say, ‘What kind of talking is this?’”

Counselors at camp, he said, “were usually (university) psychology or social work students. They were there because they had a desire to be there to help kids. Every summer I looked forward to it. When I became a counselor it was a joy for me to help a kid who was going through shit clear out and get away from it and say, Bye-bye shit, I don’t need you anymore. I knew I wanted to do this.”

He credits a camp director with giving him sound career advice. At the time, Sass was weighing what to do after high school. Though he felt called to be a teacher-counselor, he felt stymied by his lack of funds.

“He said, ‘Abe, you’ve got it. If you want it, go for it. The money will show itself. Don’t hold back ‘cause you don’t have the money.’ I totally trusted him and he was right. He was absolutely right. I was lucky enough to go to City College, which didn’t have tuition, and then Columbia University gave me a full tuition scholarship.”

Going from the lower Manhattan ghetto to elite Columbia was quite a leap.

“I was a lucky guy. I was just so happy. I was in fat cat city. That was the best training I could of had and it has helped me right through till now. There just happened to be a confluence of forces that brought these dynamite people to Columbia during those years.”

For him, the core of where the therapeutic focus needs to be was brought home by a case study of a subject with “a mouthful of rotten teeth.” Sass posited, “What would it be like walking around day after day with a pain in your head? Is that going to throw you off balance? Yeah. So, we were like back to Abraham Maslow. Basics, man. I have met a lot of people who have spun their wheels with a lot of therapists and they still haven’t dealt with the basics, and it’s sad.”

University life also fed his activist and culturist sensibilities. The Cold War was at its peak. Vietnam was just getting hot. The civil rights movement already underway.

“In college I hung out with The Beats and we were all counterculture,” he said. “We didn’t see the way it was going as the way it needed to go. We felt there was a world out there of creativity, art, exciting ideas and some of that meant taking a stand and a lot of that meant looking at the fact there are a lot of people who are not free, who have less opportunities than we do. So I started into that and my mother, of course, was very proud of that.”

He participated in sit-ins, some to show support for the activists down south “getting their heads plunked.” He was tempted to be a freedom fighter himself in Jim Crow country, and once “I was all but on my way,” before something came up.

He and a friend did go to the nation’s capital for the famous MLK-led ‘63 mass March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

“We both felt this would be an important thing to do,” he said. “Several of our friends were going…We drove there. It was wild because all these cars were on the road and people were waving at each other. I mean, we all knew where we were going. It was an amazing experience.

“We first gathered at the Washington Monument, where there were singers and all kinds of speakers, and then we walked to the Lincoln Memorial. It was a hot day and…every once in awhile somebody would pass out, but we were all so tight the person would be lifted up with hands and gently moved to the outer perimeter, where medics and assundry volunteers were set-up. It was like pre-mosh pit.”

The impact of the huge, unified crowd, estimated at 250,000, and of the speakers, capped by King’s rousing “I Have a Dream” oration, was “very, very powerful.”

Last month Abe accompanied Rivkah to D.C. for the American Library Association Conference. He retraced the march he made as part of that great procession 44 years earlier. By the end, he had a Mr. Sass Goes to Washington experience.

“I wound up one late afternoon walking the exact same path. It was hot. I went straight to the Washington Monument. It was very spiritual. Half-way between it and the Lincoln Memorial there’s ‘a Kodak moment’ spot where there’s a little display with a photo of the wading pool that day in ‘63 with all those people.

“I continued on to the Lincoln Memorial. I went up where his Gettysburg Address is engraved on one wall and I don’t know what possessed me, but I started saying it out loud. I know it pretty much by heart. And this group of tourists came over and we’re all looking at it together as I’m reading it out loud and they’re like, right there with me, and I just kept on going.”

He’d had some practice with the speech. Back at PS 11 he was selected to portray Lincoln for a school assembly. On his nostalgia trip back to D.C. all those years later, he didn’t stop with “Four Score and Seven Years Ago…”

“When I was done, I turned and I walked to the wall where his second inaugural address is engraved, and this same group of people followed, and I read that out loud. They were right there with me again. The greatest thing was I called our daughter and I told her where I was and I told her how much I loved her.”

Sass said when his daughter Ilana was a young girl she’d have friends over the house and invariably get down from a shelf the book, The Negro Since Emancipation. The back cover has an image of demonstrators in the ‘63 march and there’s the young Sass towering above the throng. His daughter would proudly proclaim to her pals, “That’s my dad.” “It was very special,” Sass said.

The melting pot experiences Sass had the first half of his life gave him an enriched perspective he carries with him to this day.

“I love my roots, I really do. I treasure them. I feel really good about having been introduced to so many wonderful ways of thinking. The weird thing is, even though there were many aspects of it that were very, very uncomfortable, I’m so glad it happened that way. Because thinking about who I am now I really feel like I viscerally can feel, for example, what people in parts of Omaha feel when they’re talking about the kind of shitty conditions they’re living in and have been living in for years and there’s no f___ing excuse for it. There really isn’t.”

Not long after moving with Rivkah to Omaha about four years ago, he attended a north Omaha town hall meeting at which Mayor Mike Fahey and his cabinet responded to issues confronting the inner city. Sass said an older woman pointedly asked how it is the cracked streets and backed-up sewers area residents like her knew as kids are still in disrepair decades later, and, how come residents out west don’t have these problems. No real answers were forthcoming. The gap between black Omaha and white suburbia apparent in the void.

“It’s hard to even try to say what I was feeling as I sat there,” Sass said. “Here we are in 2007 and there’s all this stuff about segregation…The struggle goes on, and you can’t be blind to it. You really can’t be blind to it.”

The poor, old working-class woman kvetching about inequality reminded him of his mother, each asymbol of the proletariat struggling to get by.

“She would go the shop and sit behind a sewing machine all day long busting her chops,” he said of his mom. “And she worked and worked and worked, and when she was 62-years-old she was wasted. It’s very, very sad.”

He was reminded, too, of when he went to California in the mid-’60s, fresh from Columbia, and found an unfriendly climate. En route, he stopped for gas at a roadside filling station, where, he said, “this guy and I got to talking.” When Sass mentioned he was heading for Napa, he recalled “the man saying, ‘Oh, you’re going to love it, there are no niggers in Napa.’ Holy shit, I just about fell down. Could not believe it. That’s one of the things that propelled me to join CORE.”

Once there he was dismayed to discover a form of red-lining being practiced whereby “realtors in the area were knocking on doors and saying, ‘There’s a black family moving in down the street from you — you might want to sell your house now because its value is going to diminish.’ That was going on when I got there,” he said, “so I got involved in the opposite campaign.”

He threw himself into resisting city plans for razing an established residential neighborhood built during the war for shipyards workers and their families and building high-priced condos in its place.

“A lot of the people who lived there were going to get displaced,” he said. “We (CORE) got involved in a big campaign to stop that. We had rallies, marches.

“Also, we started a freedom school in a storefront and kids would come in and we’d help them with whatever their issue was. Helping people connect with their community is very powerful.”

Wherever he saw discrimination he tried meeting it head-on.

“Not too long after I got to Napa I went for lunch with my friend Frank, a black psychiatrist. We were in this local-yokel place. We ordered and we waited. People came in after us and were served while we’re still sitting there. We asked what’s going on and the wait staff said, ‘We’re out of what you ordered.’ So we said, How about such and such? And they said, ‘We’re out of anything you’ll order.’ We really got pissed off and like two days later a shit load of us showed up, black as black can be, man. I was one of the few white guys in the group.

“We were sitting there and we weren’t moving until we got served. We said, ‘If you don’t have it today, we’re coming back tomorrow.’ They just shit in their pants. And the name of the game was they changed their policy. But not because they’re kind-hearted. It’s the pocket book. It’s money.”

He noted another incident that happened when he lived in an apartment complex. Black friends of his from CORE came over and went for a swim in the pool. When they jumped in, the whites jumped out. The next day, Sass said, he found his car’s tires slashed. He had to insist the police treat the matter as a hate crime.

“It’s sad and it’s funny and crazy and pathetic and angry…all that stuff,” he said.

He knows how hard it is for people to change attitudes and behaviors. He’s spent the better part of his life helping people try to do just that. “When somebody is going through a terrible emotional crisis my job is to help them create a revolution within themselves because what they’ve been doing is not working for them. If the revolution is successful they move on and it’s like a different world.”

Abe and Rivkah have endured their own crises, including the loss of a son.

In order to grow and to conquer our fears, he said, we must take chances. “So frequently what we do — all of us — is let ourselves be preoccupied with the fear of what will happen. It holds us all back….A piece of what I do is to help people see that right now is what we have,” he said. “I think my gift somehow is to guide people through hard times. It’s an art. I think you’re either born with this gift or not of allowing someone into your skin and your getting into their skin, safely, without being made to feel violated.”

When he was In California he worked with his share of people whose substance and lifestyle excesses caused them to “freak out.” He’s done his own experimenting and, he said, “it’s given me a better understanding of what people go through.”