Archive

A series commemorating Black History Month: North Omaha stories

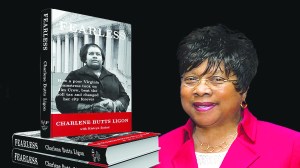

Her mother’s daughter: Charlene Butts Ligon carries on civil rights legacy of her late mother Evelyn Thomas Butts

Her mother’s daughter:

Charlene Butts Ligon carries on civil rights legacy of her late mother Evelyn Thomas Butts

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in February 2018 issue of the New Horizons

Chances are, you’ve never heard of the late Evelyn T. Butts. But you should know this grassroots warrior who made a difference at the height of the civil rights movement in the Jim Crow American South.

A new book, Fearless: How a poor Virginia seamstress took on Jim Crow, beat the poll tax and changed her city forever, written by her youngest daughter, Charlene Butts Ligon of Bellevue, Neb. preserves the legacy of this champion for the underserved and underrepresented.

Defying odds to become civil rights champion

Evelyn (Thomas) Butts grew up with few advantages in Depression Era Virginia. She lost her mother at 10. She didn’t finish high school. Her husband Charlie Butts came home from World War II one hundred percent disabled. To support their three daughters, Butts, a skilled seamstress, took in day work. She made most of her girls’ clothes.

When not cooking, cleaning, caring for the family, she volunteered her time fighting for equal rights, She became an unlikely force in Virginia politics wielding influence in her hometown of Norfolk and beyond. Both elected officials and candidates curried her favor.

She fought for integrated schools, equal city services and fair housing. Her biggest fight legally challenged the poll tax, a registration fee that posed enough of a financial burden to keep many poor blacks from exercising their right to cast a ballot. The Twenty-fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution had ruled poll taxes illegal in federal elections but the practice continued in southern state elections as a way to disenfranchise blacks. Butts’ case, combined with others. made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. in 1966, Thurgood Marshall argued for the plaintiffs. In a 6-3 decision, the court abolished the poll tax in state elections and Butts went right to work registering thousands of voters.

Devoted daughter documents mom’s legacy in book

More than 50 years since that decision and 25 years since her mother’ death in 1993, Ligon has written and published a book that chronicles Evelyn Butts’ life of public service that inspired her and countless others.

Ligon and her husband Robert are retired U.S. Air Force officers. The last station of their well-traveled military careers was at Offutt Air Force Base from 1992 to 1995. When they retired, the couple opted to make Nebraska their permanent home. They are parents to three grown children and five grandchildren.

By nature and nurture, Ligon, inherited her “mama’s” love of organized politics, community affairs and public service. She’s chair of the Sarpy County Democrats and secretary of the Nebraska State Democratic Party. As the party’s state caucus chair, she led a nationally recognized effort that set up caucuses in all 93 counties and developed an interactive voting info website.

Former Nebraska Democratic Party executive director Hadley Richters knows a good egg when she sees one.

“In politics, you learn quickly the people who will actually do the work are few, and even fewer are those who strive to do it even better than before. Charlene Ligon is definitely a part of that very few. I have also learned those few, like Charlene, are who truly uphold our democracy. Charlene works tirelessly to further participation in the process, selflessly driven by rare and deep understanding of what’s at stake. She is a champion for voices to be heard, and when it comes to protecting the democratic process, defending fairness, demanding access, and advocating for what is right, I can promise you Charlene will be present, consistent, hard-working and fearless.”

Ligon is a charter member of Black Women for Positive Change, a national policy-focused network whose goals are to strengthen and expand the American middle-working class and change the culture of violence.

Besides her mother, she counts as role models: Barbara Jordan, Shirley Chisholm and Dorothy Height.

In addition to participating in lots of political rallies, she’s an annual Omaha Women’s March participant.

Like her mother before her. she’s been a Democratic National Convention delegate, she’s met party powerbrokers and she’s made voting rights her mission.

“It all goes back to that – access and fairness. That’s how I see it.”

Even today, measures such as redistricting and extreme voter ID requirements can be used to suppress votes. She still finds it shocking the lengths Virginia and other states went to in order to suppress the black vote.

“Virginia’s really shameful in the way it did voting,” she said. “At one time, they had what they called a blank sheet for registration. When you went to register to vote you had to know ahead of time what identifying information you needed to put on there. It wasn’t a literacy test. By law, the registrar could not help people, so people got disqualified. Well, the black community got together and started having classes to educate folks what they needed to know when they went to register.”

The blank sheet was on top of the poll tax. An unintended effect was the disqualification of poor and elderly whites, too. In a majority white state, that could not hold and so a referendum was organized and the practice discontinued.

“The history books tell you they did it because of white backlash, not because of black backlash,” Ligon said.

Virginia’s regerettable record of segregation extended to entire school districts postponing school and some schools closing rather than complying with integration

“It always amazes me they did that,” she said.

Speaking her mind and giving others a voice

As a Norfolk public housing commissioner, Butts broke ranks with fellow board members to publicly oppose private and public redevelopment plans whose resulting gentrification would threaten displacing black residents.

“She really gave them a fit because they weren’t doing what they should have been doing for poor neighborhoods and she told them about it. They weren’t really ready for her to bring this out,” Ligon said of her mother’s outspoken independence.

“Mama could be stubborn, too. She was authoritarian sometimes.”

Butts became the voice for people needing an advocate.

“They called her for all kinds of things. They called her when they needed a house, when they were having problems with their landlord. They called her and called her. They knew to call Mrs. Butts and that if you call Mrs. Butts, she’ll help you. Nine times out of ten she could get something for them. She had that reputation as a mover and shaker and they knew she wasn’t going to sell them out because it wasn’t about money for her.”

Ligon fights the good fight herself in a different climate than the one her mother operated in. It makes her appreciate even more how her mom took on social issues when it was dangerous for an African-American to speak out. She admires the courage her mother showed and the feminist spirit she embodied.

“My mama always spoke up. She didn’t cow. She talked kind of loud. I got that from her. She looked them in the eye and said, ‘Yeah, this is the way it needs to be.’ They didn’t always pay attention to her, but she just always was ready to say what needed to be said. Of course, the establishment didn’t want to hear it. But she actually won most people’s respect.”

Growing up, Ligon realized having such a bigger-than-life mother was not the norm.

“She stood out in my life. I started to understand that my mom was different than most people’s moms. She was always doing something for the neighborhood. There were so many things going on in the 1950s through the early 1960s that really got her going.”

Her mother was at the famous 1963 March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. Charlene wanted to go but her mother forbade it out of concern there might be violence. Being there marked a milestone for Evelyn – surpassed only by the later Supreme Court victory.

“It meant a lot to her. That was the movement. That was what she believed,” Ligon said. “And it was historic.”

Long before the march, Butts saw MLK speak in Petersburg, Virginia. He became her personal hero.

“She was already moving forward, but he inspired her to move further forward.”

Decades later, Ligon attended both of Obama’s presidential inaugurations. She has no doubt her mother would have been there if she’d been alive.

“I wish my mom could have been around to see that, although electing the nation’s first black president didn’t have the intended effect on America I thought it would. It gave me faith though when he was elected that the process works, that it could happen. He could not have won with just black votes, so we know a lot of white people voted for him. We should never forget that.

“It just really made me proud.”

Ligon shook hands with President Obama when he visited the metro. She’s met other notable Democrats, such as Joe Biden, Hilary Clinton, Bill Clinton, Jim Clybern, Doug Wilder, Ben Nelson and Bob Kerrey.

The day the Supreme Court struck down the poll tax, her mother got to meet Thurgood Marshall – the man who headed up the Brown vs. Board of Education legal team that successfully argued for school desegregation.

“She was really thrilled to meet him.”

Then-U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy was in the courtroom for the poll tax ruling and Evelyn got to meet the future presidential candidate that day as well.

Butts was vociferous in her pursuit of justice but not everyone in the movement could afford to be like her.

“As I look back on the other prominent people in the movement,” Ligon said, “they had their ways of contributing but there were a lot of people who had what they considered something to lose. For instance, teachers just wouldn’t say a word because they were afraid for their jobs. There were lots of people that wouldn’t say anything.”

Her mother exuded charisma that drew people to her.

“People liked her. Mama was an organizer. She was the person that got them all together and she was inspirational to them, I’m sure. She had a group of ladies who followed her. They were like, “Okay. Mrs. Butts, what are we going to do today? Are we going to register voters? Are we going to picket?”

Evelyn Butts formed an organization called Concerned Citizens for Political Education that sought to empower blacks and their own self-determination. It achieved two key victories in the late 1960s with the election of Joseph A. Jordan as Norfolk’s first black city council member since Reconstruction and electing William P. Robinson as the city’s first African-American member of the state House of Delegates.

Charlene marveled at her mother’s energy and industriousness.

“I was always proud of her.”

Having such a high profile parent wasn’t a problem.

“I never felt uncomfortable or had a negative feeling about it.”

Even when telling others what she felt needed to be done, Ligon said her mother “treated everybody with respect,” adding “The Golden Rule has always been my thing and I’m sure my mom taught me the Golden Rule.”

Telling the story from archives and memories

As big a feat as it was to end the poll tax, Ligon felt her mother’s accomplishments went far beyond that and that only a book could do them justice. So, in 2007, she and her late sister Jeanette, embarked on the project.

“We thought people needed lo know the whole story.”

Ligon’s research led her to acclaimed journalist-author Earl Swift, a former Virginian Pilot reporter who wrote about her mother. He ended up editing the book. He insisted she make it more specific and full of descriptive details. Poring through archives, Ligon found much of her mother’s activities covered in print stories published by the Pilot as well as by Norfolk’s black newspaper, the New Journal and Guide. Ligon also interviewed several people who knew her mother or her work.

Writer Kietryn Zychal helped Ligon pen the book.

Much of the content is from Charlene and her sister’s vivid memories growing up with their mom’s activism. As a girl, Charlene often accompanied her to events.

“She took me a lot of places. I was exposed.”

Those experiences included picketing a local grocery store that didn’t hire blacks and a university whose athletics stadium restricted blacks to certain sections

“The first time i remember attending a political-social activism meeting with Mama was the Oakwood Civic League about 1955 during the same time the area was under annexation by the city of Norfolk. My next memory is attending the NAACP meeting at the church on the corner from our house concerning testing to attend integrated schools. I have vivid memories of attending the court proceedings of a school desegregation case. Mama took me to court every day. She was called to testify by the NAACP lawyers.”

Charlene joined other black teenage girls as campaign workers under the name the Jordanettes, for candidate Joe Jordan. Her mom made their matching outfits.

“We passed out literature, campaign buttons, bumper stickers at picnics, rallies and meetings. Hanging out with my mom and doing the campaign stuff definitely had an influence. I was always excited to tag along.”

At home, politics dominated family discussions.

“My mom did what she did all the time and she talked about it all the time, and so I always knew what was going on, She involved us. She would update my dad. We were always in earshot of the conversation. My sisters and I were expected to be aware of what was happening in our community. We were encouraged to read the newspaper. We participated in some picketing.”

Always having Evelyn’s back was the man of the house.

“He was behind her a hundred percent,” Ligon said of her father, who unlike Evelyn was quiet and reserved. He didn’t like the limelight but, Charlene said, “he never fussed about that – he was in her corner.”

“He might not have done that (activism) personally himself but yeah he was proud she was out there doing that. As long as she cooked his dinner.”

Because Evelyn Butts was churched, she saw part of her fighting the good fight as the Christian thing to do.

“We attended church but my mama wasn’t really a church lady. She just always believed in what the right thing to do would be. I guess that inner thing was in all of us as far as social justice.

“She taught me there wasn’t anything I couldn’t do if I put my mind to it. She taught me not to be afraid of people because I was different.”

When it came time for Ligon to title her book, the word fearless jumped out.

“That’s what she was.”

Where did that fearless spirit come from?

After her mother died, she was raised by her politically engaged aunt Roz. But headstrong Evelyn took her activism to a whole other level.

“I remember Roz telling mama to be careful. She said, ‘Evelyn, you better watch out, they’re going to kill you.'”

The threat of violence, whether implied or stated, was ever present.

“That’s just the way it was. In Virginia, we had some bad things happen, but it wasn’t like Mississippi and the civil rights workers getting killed. We had a few bombings and cross burnings. It still amazes me how she was able to put up with what she did. A lot of people were frightened. Not far from where we lived. racists were bombing houses near where she was picketing. She wasn’t frightened about that and she always made us feel comfortable that things were going to be okay.”

Butts drew the ire of those with whom she differed, white and black. For example, she called out the Virginia chapter of the NAACP for moving too slowly and timidly.

“My mom was considered militant back in the day, but she was also pragmatic about it. There was so much ground to cover. There’s still a lot of ground to cover.”

Progress won and lost in a never-ending struggle

Ligon rues that today’s youth may not appreciate how fragile civil rights are, especially with Donald Trump in office and the Republicans in control of Congress.

“I don’t think young people realize we’re losing ground. They aren’t paying attention. They take things for granted, I’m old enough to remember when everything was segregated and how restrictive it was. I may not want to go anywhere then someplace where all the people look like me, but I need to have that choice.

“We’ve lost almost all the ground we made when Barack Obama was president. People who wanted change said we don’t need the status quo and I would say, yes we do, we need to hold it a little bit.”

She’s upset Obama executive orders are under assail. Protections for DACA recipients are set to end pending a compromise plan. Obamacare is being undone. Sentences for nonviolent drug offenders are being toughened and lengthened.

Perhaps it’s only natural the nation’s eyes were taken off the prize once civil rights lost an identifiable movement or leader. But Ligon chose a Corretta Scott King quotation at the front of her book as a reminder that when it comes to preserving rights, vigilance is needed.

Struggle is a never ending process. Freedom is never really won –you earn it in every generation.

“I think the struggle is always going to be there for us minorities, specifically for African-Americans,” Ligon said. “It’s my belief we’re always going to have it. Each generation has to continue to move forward. You can’t just say, ‘We have it now.'”

She’s concerned some African-Americans have grown disillusioned by the overt racism that’s surfaced since Trump emerged as a serious presidential candidate and then won the White House.

“With the change that’s happened in the United States, I think a lot of them have lost faith. They seem to have given up. They say America is white people’s country. I remind them it’s our country. Do you know how much blood sweat and tears African-Americans have invested in America? Somewhere down the line we did not instill that this is our country. It’s okay to be patriotic and call them out every day. You can do both.”

How might America be different had MLK lived?

“Hopefully, we would be a little bit further along in having a more organized movement,” said Ligon.

She’s distressed a segment of whites feel the gains made by blacks have come at their expense.

“Some white people feel something has been taken from them and given to the minorities, which is sad, because it’s not really so. But they feel that way.”

She feels the election of Trump represented “a backlash” to the Obama presidency and his legacy as a progressive black man in power.

If her mother were around today, Charlene is sure she would be out registering voters and getting them to the polls to ensure Trump and those like him don’t get reelected or elected in the first place.

In her book’s epilogue, Charlene suggests people stay home from the polls because they believe politics is corrupt and dirty but she asserts Mama Butts would have something to say about that.

If my mother could, I know she’d say this: If you don’t vote, you can be assured that corrupt politicians will be elected.

“And that’s the truth,” Ligon said.

Drawing strength from a deep well

Just where did her mother get the strength to publicly resist oppression?

“It probably came from a long line of strong women. My grandmother’s sisters, including Roz, who raised my mom, and women from the generation before. The men, I suspect, were pretty strong too. You just had to know my mom and the other family ladies, and the conclusion would be something was in the genes that made them fighters. They were fighters, no doubt. They all were civic-minded, too.”

Going back even earlier in the family tree reveals a burning desire for freedom and justice.

“My great-great-grandfather Smallwood Ackiss was a slave who ran away from the plantation during the Civil War after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and went to Norfolk. He went on to fight for the Union for two years,” Ligon said. “In 1865, he came back to the plantation. John Ackiss II, who was the plantation owner and his owner, had been fighting for the Confederacy at the same time. We do know Smallwood was given 30 acres of land. He lost the property, but we still have a family cemetery there that’s now on a country club in a real exclusive area of Virginia Beach.”

From Smallwood right on down to her mother and herself, Charlene is part of a heritage that embraces freedom and full participation in the democratic process.

“I guess I was always interested and Mom always took me with her. I always saw it. Even in the military, when stationed in South Dakota, I chaired the NAACP Freedom Fund in Rapid City.

“It’s always been there.”

She feels her time in the service prepared her to take charge of things.

“The military strengthens leadership. It’s geared for you to get promoted to become a leader.”

Then there’s the fact she is her mother’s daughter.

Entering the service in the first place – as a 26-year-old single mother of two young children – illustrated her own strong-willed independence. It was 1975 and the newly initiated all-volunteer military was opening long-denied opportunities for women.

“I was divorced, had two kids and I needed child care and a regular salary. I didn’t want to have to depend on anyone else for it but me. It was difficult entering the military as a single parent, but I saw it as security for me and my kids. I was really fortunate I met a great guy whom I married and we managed to finish out our careers together.”

Ligon made master sergeant. She worked as a meteorologist.

“I didn’t want a traditional job. I didn’t want to be an administrative clerk in an office.”

She ended her career as a data base programmer and since her retirement she’s done web development work. She also had her own lingerie boutique, Intimate Creations, at Southroads Mall. Democratic Party business takes up most of her time these days.

Charlene’s military veteran father died in 1979. He supported her decision to serve her country.

Bittersweet end and redemption

While off in the military, Charlene wasn’t around to witness her mother falling out of favor with a new regime of leaders who distanced themselves from her. Mama Butts lost bids for public office and was even voted out of the Concerned Citizens group she founded. This, after having received community service awards and being accorded much attention.

Personality conflicts and turf wars come with the territory in politics.

“For a long time, my mom didn’t let those things stop her.”

Then it got to be too much and Evelyn dropped out.

Upon her death, Earl Swift wrote:

Evelyn Butts’ life had become a Shakespearean tragedy. She’d dived from the heights of power to something very close to irrelevance. This is someone who should have finished life celebrated, rather than forgotten. History better be kind to this woman. Evelyn Butts was important.

The family agreed her important legacy needed rescue from the political power grabs that tarnished it.

“The Democratic Party really was not nice to my mom. That was another reason I wrote the book – because I wanted that to be known,” Charlene said. “I didn’t know all that had gone on until 1993 when she died. I wanted to present who she was. how she came to be that way and the lessons you can learn from her life. I think those lessons are really important for young people because we need to move forward, we need to stay focused and know that we can’t give up – the struggle is still there.

“People need to vote. That’s what they really need to do. They need to participate. Voting is their force and they don’t realize it, and that’s really disheartening. Even in Norfolk, my hometown, the registered voter numbers and turnout for elections among blacks is horrible – just like it is here. In north and south Omaha, they don’t turn out the way they could – 10 to 15 percent less than the rest of the city. That should not be.

“When John Ewing ran for Congress he lost by one and a half points. A little bit of extra turnout in North Omaha would have put him over the top. The same thing happened when Brenda Council ran for mayor of the City of Omaha. If they had turned out for Brenda, Brenda would have been elected. That discourages me because they feel like they’re only a small percentage of the population. Yes, it’s true, but you can still make a difference and when you make that difference that gives you a voice. When you can swing an election, candidates and elected officials pay attention. When black voters say ‘they don’t care about us,’ well I guess not, if you don’t have a voice.”

If anything, the work of Evelyn Butts proved what a difference one person can make in building a collective of activated citizens to make positive change.

To Ligon’s delight, her mother is fondly remembered and people want to promote her legacy. A street and community center are named after her. A church houses a tribute display. Endorsements for the book came from former Virginia governor and senator Chuck Robb and current Norfolk mayor Kenneth Cooper Alexander, who wrote the foreword.

Ligon was back home in Norfolk in January for a book signing in conjunction with MLK Day. She’s back there again for more book signings in February for Black History Month.

In Omaha, Fearless is available at The Bookworm, other fine bookstores and select libraries.

Fittingly, the book has been warmly received by diverse audiences. Long before intersectionality became a thing, Ligon writes in her book, her mother practiced it.

She was black. She was a woman. She was poor. She had dropped out of high school. She was overweight and she spoke loudly with confidence in her opinions in a voice that disclosed her working-class, almost rural upbringing. But this large, black poor woman was in the room with politically powerful white people, making policy and advocating for the poor, and it drove some suit-wearing, educated, well-heeled, middle-class male ministers nuts. Some wanted her place. Or, they believed her place should be subservient to a man.

When her public career ended, my mother retreated to private life … She occupied her time by being a mother, a grandmother, a caregiver, a homemaker and a fantastic cook. To say that her post-political years were tragic is to miss how much strength and satisfaction she drew from those roles. She may have retreated, but she was not defeated.

We will never come to consensus on why Evelyn Butts lost her political power. There will always be people in Norfolk who thought her ‘style’ made her unelectable, that she brought about her own demise … Whatever her failings, her legacy is not in dispute. She will always exist in the pages of the U.S. Supreme Court case, in brick and mortar buildings that she helped to create, and in the memories of people …

For me, her last surviving daughter, Evelyn Butts will always be a great American hero.

If there’s a final lesson Charlene said she’s taken from her mother it’s that “there are things bigger than yourself to fight for – and so I do what I do for my kids and grandkids.”

She’s sure her mom would be proud she followed in her footsteps to become a much decorated Democratic Party stalwart and voting rights champion.

“I haven’t thought about a legacy for myself. I hope people will remember me as a hard worker and as a pragmatic, fair fighter for social justice and civil rights.”

Visit evelyntbutts.com or http://www.facebook.com/evelyntbutts.

Re-entry prepares current and former incarcerated individuals for work and life success on the outside

Re-entry prepares current and former incarcerated individuals for work and life success on the outside

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the December 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

A growing community of re-entry pathways serve current and former incarcerated individuals needing work upon release.

Many re-entry programs are run by people who’ve been in the criminal justice system themselves.

“Those closest to the problem are closest to the solution,” said ReConnect Inc. founding director LaVon Stennis-Williams, a former civil rights attorney who served time in federal prison. “You have people like myself coming out of prison no longer waiting for others to remove barriers. There is a network of movements being led by formerly incarcerated individuals taking control of this whole effort to make reentry something more than just talk. We’re developing programs that try to ensure people coming out are successful and don’t go back to prison.”

Some area re-entry programs are formalized, others less so. Several are grantees through the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services’ administered Vocational and Life Skills grant stemming from 2014 state prison legislation (LB 907). Programs work with individuals inside and outside state prisons.

ReConnect provide services Stennis-Williams didn’t find upon her own release in 2010.

“When I came out of prison, many second chance programs started under the 2008 Second Chance initiative either did not get refunded or the funding dried up,” she said. “So when I came out there weren’t many out there – just kind of the residuals.”

What there were, she said, were disjointed and uncoordinated.

“I wanted to create a program I wish would have been in existence when I was navigating re-entry. What I realized from my own personal experience – it did not matter how well educated you were, how much money you had, what connections you had, when you’re going through re-entry, you’re going to face barriers. I developed a program to fill service gaps and to be not so much a hand-out as an empowering thing to help overcome those barriers.”

Employment assistance is a major piece of ReConnect.

“We look beyond just helping them with creating a resume and building interview skills. We spoke with employers to find out what soft skills they’re looking for in people. In our employment readiness program Ready for Work we put a lot of emphasis on those core competencies employers want: dependable, reliable, strong work ethic, problem solvers.”

ReConnect’s Construction Toolbox Credentials Training workshops prepare participants for real jobs.

“We worked with construction companies to find out what they’re looking for in people and we developed a training program using industry professionals to come teach it. They issue industry recognized certificates.”

Metropolitan Community College has convened around re-entry for more than a decade. Today, it’s a sanctioned service provider with 180 Re-entry Assistance Program.

“The thing we constantly hear from employers is that the pool of potential employees they’re fishing in do not have employability skills,” said director Diane Good-Collins, who did a stretch in state prison. “They don’t know how to show up on time, how to communicate with their supervisor, how to be a team player. Those are the things we’re teaching clients while they’re still incarcerated, so when they come out of prison they’re on a level playing field with those without criminal histories they’re competing against for jobs.”

Programs like 180 and ReConnect build background friendly employer pipelines.

“We work now with over 80 employers,” Stennis-Williams said. “These employers are very receptive to hiring men and women who participate in our job readiness workshops. I think employers’ attitudes are changing, partly because of economics. Employers are realizing they cannot ignore this labor force anymore.

“That’s why I think they’re making an effort now to reach out to programs like ours.”

Metro’s 180 program sees a similar shift.

“We have worked hard talking to employers about the population and helping destigmatize them. Employers understand this is the hidden workforce. Individuals are coming out trained, ready to enter the workforce and have the support of MCC and others in the community as they transition. They are ready to do something different and really what they need is an opportunity,” said Good-Collins. “Statistics show those who get educated while incarcerated are many times less likely to go back to prison.”

Good-Collins said MCC closely vets participants.

“We’re not just going to send employers 10 people we don’t know anything about. We prescreen them to make sure they’re ready to be a part of their organization.”

Despite rigorous standards and numerous success stories, she said, not all employers want in.

“Some of the barriers are nonnegotiable. Some employers say they absolutely will never hire somebody with a criminal history. Some companies are limited to who they can hire due to liability concerns. Some have no idea they aren’t willing to until we talk to them about it. People with particular criminal histories can’t get hired in certain jobs.”

Good-Collins found a receptive audience at a Human Resources Association of the Midlands diversity forum she presented at in October.

“Several HR directors said they’d be willing to work with us and we’ve established relationships with their companies. I feel like the proverbial door was kicked open and destigmatizing took place.”

Metro’s credit offerings inside prison include business, entrepreneurship, trades and information technology.

“We chose to teach those four career pathways inside the correctional facilities because those are areas the population can find a job in when released.

“Employability Skills and Introduction to Micro-computer Technology are our foundation courses because they give you a foot in the door with an employer.”

Process and Power Operations is a manufacturing and distribution certification course. Upon completion, she said, “its national certification equals gainful employment upon release,” adding, “We’ve worked with guys who got this and are making very good money.”

“Manufacturing and construction are popular career fields and well-paying options,” she said. “With our forklift training, you can get a job almost immediately at one of our employer partners. Other graduates work in food service – entry level to management level.”

More re-entry efforts that focus around employment readiness include Intro To The Trades and Urban Pre-Vocational Training programs offered by Black Men United.

Big Mama’s Restaurant and Catering owner Patricia Barron has a long history hiring wait and kitchen staff with criminal histories.

Comprehensive programs like Metro’s 180 and ReConnect offer wrap-around services to clients, including transition support, referral to community agencies, coaching-tutoring-mentoring and employment assistance.

“We serve as a liaison in case there’s an issue that comes up at work and if the employee has a barrier with transportation or child care,” Good-Collins said. “We basically stand as a support and advocate.

“If they’re not at a point in their education and training to be eligible to go into a career position, then we guide them to survival employment, so at least they get working. Meanwhile, they can pursue their educational-employment goal to get to where they want to.”

Teela Mickles has worked with returning citizens for three decades. Her Compassion in Action seeks to “embrace the person, rebuild the family and break the cycle of negativity and recidivism.” CIA’s Pre-Release-Education-Reentry Preparation focuses on the individual and the unresolved core issues that led to criminal acts.

Personal validation, self-exploration and personal development activities help clients change their thinking and behaviors, said Mickles. “This allows each individual to succeed in other services offered to this population: drug rehabilitation, advance education, employment readiness and gainful employment.”

CIA, ReConnect, 180 and other programs refer clients to mental or behavioral health counseling as needed.

There’s also a prevention aspect to e-entry work. Adult clients with kids learn parenting skills and strategies that can help keep their children from entering the system. ReConnect and CIA both have youth and family components.

Jasmine Harris is Post-Release Program manager for the area’s latest re-entry player: Defy Ventures, a national organization with regional chapters. its intensive six-month CEO of Your New Life program

explores character development, transformational education and employment readiness. Participants learn to transition their street hustle experiences, talents and skills into career applications. Clients develop a life plan.

“Getting them to see that skill set and how to use it on the positive side of things really turns on a light for them and they love it,” Harris said. “We bring in volunteers for business coaching days. The entrepreneurship part is the hallmark of our program. We call our participants EITs or Entrepreneurs in Training. They get one-on-one basic entrepreneurship.”

Volunteers assist clients in developing a business plan.

“Our curriculum is vetted by Baylor University,” Harris said. “and if participants pass they get a certificate of career readiness. We do a full cap and gown graduation. That’s when we have our business pitch competition. We bring in volunteers, business execs, entrepreneurs and do a shark tank style competition. Everyone graduating pitches their business idea.”

Cash prizes are awarded.

In terms of post-release, Harris deploys the same six month program on the outside that’s offered in prison.

“Anyone in the community with a criminal history, whether they were formally incarcerated or had a misdemeanor or a felony probation, can participate if they’re looking for another option.”

Harris also runs the program’s business incubator.

“Our Entrepreneur Incubator is an additional 12 to 15 months of training. We match clients up with executive mentors who’ve gone through the process of starting their own business. Mentors help walk them through the business start-up process.

“We have business coaching nights and workshops where we bring in subject matter experts who give more in-depth information.”

Harris connects clients with workforce development resources. help with resumes and two big barriers – affordable housing and access to transportation.

“We connect them to services in the community where it makes sense. Everybody doesn’t want to be an entrepreneur or go to school. We let them know there’s a program over here doing a trades piece or there’s another program doing the education piece.”

Re-entry experts agree there are more and better services today but Harris and others see a need for more collaboration among providers.

Good-Collins said no matter how one feels about reentering citizens, they’re here to stay.

“Maybe you can look at it from a dollars and cents perspective and realize it doesn’t make fiscal sense to do what we’ve been doing, which is paying to re-incarcerate people.”

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

The November issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com) features my story on an old-line but still vital social action organization celebrating 90 years in Omaha.

The Urban League. The name may be familiar but the role it plays not. Since the National Urban League’s 1910 birth from the progressive social work movement, it’s used advocacy over activism to promote equality. The New York City-based NUL encouraged the creation of affiliates to serve blacks leaving the South in the Great Migration. One of its oldest continuously operating affiliates is the Urban League of Nebraska. The local non-profit started in 1927 as the Omaha Urban League and so operated until changing to Urban League of Nebraska (ULN) in 1968.

This century-plus national integrationist organization is anything but a tired old outfit living off 1950s-1960s Freedom Movement laurels. Its mission today within the ongoing movement is “to enable African-Americans to secure economic self-reliance, parity, power and civil rights.” Ditto for ULN, which marks 90 years in 2017. At various times the local office made housing, jobs and health priorities. Today, it does advocacy around juvenile justice, education and child welfare reform and is a service provider of education, youth development, employment and career services programs. It continues a long-standing scholarships program.

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the November 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The Urban League.

The name may be familiar but the role it plays not. Since the National Urban League’s 1910 birth from the progressive social work movement, it’s used advocacy over activism to promote equality. The New York City-based NUL encouraged the creation of affiliates to serve blacks leaving the South in the Great Migration. One of its oldest continuously operating affiliates is the Urban League of Nebraska. The local non-profit started in 1927 as the Omaha Urban League and so operated until changing to Urban League of Nebraska (ULN) in 1968.

This century-plus national integrationist organization is anything but a tired old outfit living off 1950s-1960s Freedom Movement laurels. Its mission today within the ongoing movement is “to enable African-Americans to secure economic self-reliance, parity, power and civil rights.” Ditto for ULN, which marks 90 years in 2017. At various times the local office made housing, jobs and health priorities. Today, it does advocacy around juvenile justice, education and child welfare reform and is a service provider of education, youth development, employment and career services programs. It continues a long-standing scholarships program.

Agency branding says ULN aspires to close “the social economic gap for African-Americans and emerging ethnic communities and disadvantaged families in the achievement of social equality and economic independence and growth.”

The emphasis on education and employment as self-determination pathways became more paramount after the Omaha World-Herald’s 2007 series documenting the city’s disproportionately impoverished African-American population. ULN became a key partner of a facilitator-catalyst for change that emerged – the Empowerment Network. In a decade of focused work, North Omaha blacks are making sharp socio-economic gains.

“It was a call to action,” current ULN president-CEO Thomas Warren said of this concerted response to tackle poverty. “This was the first time in my lifetime I’ve seen this type of grassroots mobilization. It coincided with a number of nonprofit executive directors from this community working collaboratively with one another. It also was, in my opinion, a result of strategically situated elected officials working cooperatively together with a common interest and goal – and with the support of the donor-philanthropic community.

“The United Way of the Midlands wanted their allocations aligned with community needs and priorities – and poverty emerged as a priority. Then, too, we had support from our corporate community. For the first time, there was alignment across sectors and disciplines.”

Unprecedented capital investments are helping repopulate and transform a long neglected and depressed area. Both symbolic and tangible expressions of hope are happening side by side.

“It’s the most significant investment this community’s ever experienced,” said Warren, a North O native who intersected with ULN as a youth. He said the League’s always had a strong presence there. He came to lead ULN in 2008 after 24 years with the Omaha Police Department, where he was the first black chief of police.

“I was very familiar with the organization and the importance of its work.”

He received an Urban League scholarship upon graduating Tech High School. A local UL legend, the late Charles B. Washington, was a mentor to Warren, whose wife Aileen once served as vice president of programs.

Warren concedes some may question the relevance of a traditional civil rights organization that prefers the board room and classroom to Black Lives Matter street tactics.

“When asked the relevance, I say it’s improving our community and changing lives,” he said, “We prefer to engage in action and to address issues by working within institutions to affect change. As contrasted to activism, we don’t engage much in public protests. We’re more results-oriented versus seeking attention. As a result, there may not be as much public recognition or acknowledgment of the work we do, but I can tell you we have seen the fruits of our efforts.”

“We’re an advocacy organization and we’re a services and solutions provider. We’re not trying to drum up controversy based on an issue,” said board chairman Jason Hansen, an American National Bank executive. “We talk about poverty a lot because poverty’s the powder keg for a lot of unrest.”

Impacting people where they live, Warren said, is vital if “we want to make sure the organization is vibrant, relevant, vital to ensuring this community prospers.”

“We deal with this complex social-economic condition called poverty,” he said. “I take a very realistic approach to problem-solving. My focus is on addressing the root causes, not the symptoms. That means engaging in conversations that are sometimes unpleasant.”

Warren said quantifiable differences are being made.

“Fortunately, we have seen the dial move in a significant manner relative to the metrics we measure and the issues we attempt to address. Whether disparities in employment, poverty, educational attainment, graduation rates, we’ve seen significant progress in the last 10 years. Certainly, we still have a ways to go.”

The gains may outstrip anything seen here before.

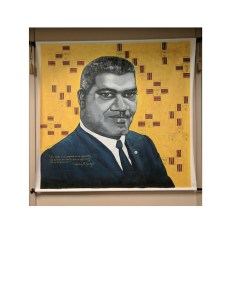

Soon after the local affiliate’s start, the Great Depression hit. The then-Omaha Urban League carried out the national charter before transitioning into a community center (housed at the Webster Exchange Building) hosting social-recreational activities as well as doing job placements. In the 1940s, the Omaha League returned to its social justice roots by addressing ever more pressing housing and job disparities. When the late Whitney Young Jr. came to head the League in 1950, he took the revitalized organization to new levels of activism before leaving in 1953. He went on to become national UL executive director, he spoke at the March on Washington and advised presidents. A mural of him is displayed in the ULN lobby.

Warren’s an admirer of Young, “the militant mediator,” whose historic civil rights work makes him the local League’s great legacy leader. In Omaha, Young worked with white allies in corporate and government circles as well as with black churches and the militant social action group the De Porres Club led by Fr. John Markoe to address discrimination. During Young’s tenure, modest inroads were made in fair hiring and housing practices.

Long after Young left, the Near North Side suffered damaging blows it’s only now recovering from. The League, along with the NAACP, 4CL, Wesley House, YMCA, Omaha OIC and other players responded to deteriorating conditions through protests and programs.

League stalwarts-community activists Dorothy Eure and Lurlene Johnson were among a group of parents whose federal lawsuit forced the Omaha Public Schools to desegregate. ULN sponsored its own community affairs television program, “Omaha Can We Do,” hosted by Warren’s mentor, Charles Washington.

Mary Thomas has worked 43 years at ULN, where she’s known as “Mrs. T.” She said Washington and another departed friend, Dorothy Eure, “really helped me along the way and guided me on some of the things I got involved in in civil rights. Thanks to them, I marched against discrimination, against police brutality, for affirmative action, for integrated schools.”

Rozalyn Bredow, ULN director of Employment and Career Services, said being an Urban Leaguer means being “involved in social programs, activism, voter rights, equal rights, women’s rights – it’s wanting to be part of the solution, the movement, whatever the movement is at the time.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, ULN changed to being a social services conduit under George Dillard.

“We called George Dillard Mr. D,” said Mrs. T. “A very good, strong man. He knew the Urban League movement well.”

She said the same way Washington and Eure schooled her in ciivl rights, Dillard and his predecessor, George Dean, taught her the Urban League movement.

“We were dealing with a multiplicity of issues at that particular time,” Dillard said, “and I imagine they’re still dealing with them now. At the time I took over, the organization had been through two or three different CEOs in about a five year period of time. That kind of turnover does not stabilize an organization. It hampers your program and mission.”

Dillard got things rolling. He formed a committee tasked with monitoring the Omaha Public Schools desegregation plan “to ensure it did not adversely affect our kids.” He implemented a black community roundtable for stakeholders “to discuss issues affecting our community.” He began a black college tour.

After his departure, ULN went through another quick succession of directors. It struggled meeting community expectations. Upon Thomas Warren’s arrival, regaining credibility and stability became his top priority. He began by reorganizing the board.

“When I started here in 2008 we had eight employees and an operating budget of $800,000, which was about $150,000 in the red,” Warren said. “Relationships had been strained with our corporate partners and with our donor-philanthropic community, including United Way. My first order of business was to restore our reputation by reestablishing relationships.”

His OPD track record helped smooth things over.

“As we were looking to get support for our programs and services, individuals were willing to listen to me. They wanted to know we would be administering quality services. They wanted to know our goals and measurable outcomes. We just rolled up our sleeves and went to work because during the recession there was a tremendous increase in demand for services. Nonprofits were struggling. But we met the challenge.

“In the first five years we doubled our staff. Tripled our budget. Currently, we manage a $3 million operating budget. We have 34 full-time employees. Another 24 part-time employees.”

Under Warren. ULN’s twice received perfect assessment scores from on-site national audits.

“It’s a standard of excellence for our adherence to best practices and compliance with the Urban League’s articles of affiliation,” he said.

Financially, the organization’s on sound footing.

“We’ve done a really admirable job of diversifying our revenue stream. More than 85 percent of our revenue comes from sources other than federal and state grants,” said board chair Jason Hansen. “We have a cash reserve exceeding what the organization’s entire budget was in 2008. It’s really a testament to strong fiscal management – and donors want to see that.”

“It was very important we manage our resources efficiently,” Warren said.

Along the way, ULN itself has been a jobs creator by hiring additional staff to run expanding programs.

“The growth was incremental and methodical,” Warren said, “We didn’t want to grow too big, too fast. We wanted to be able to sustain our programs. Our ability to administer quality programs got the support of our donor-philanthropic-corporate-public communities.

“We have been able to maintain our workforce and sustain our programs. The credit is due to our staff and to the leadership provided by our board of directors.”

Warren’s 10 years at the top of ULN is the longest since Dillard’s reign from 1983 to 2000. Under Warren, the organization’s back to more of its social justice past.

Even though Mrs. T’s firebrand activism is not the League’s style, sometimes causing her to clash with the reserved Warren, whom she calls “Chief,” she said they share the same values.

“We just try to correct the wrong that’s done to people. I always have liked to right a wrong.”

She also likes it when Warren breaks his reserve to tell it like it is to corporate big wigs and elected officials.

“When he’s fighting for what he believes, Chief can really be angry and forceful, and they can’t pull the wool over his eyes because he sees through it.”

Mrs. T feels ULN’s back to where it was under Dillard.

“It was very strong then and I feel it’s very strong now. In between Mr. D and Chief, we had a number of acting or interim directors and even though those people meant well, until you get somebody solid, you’ve got a weakness in there.”

Pat Brown agrees. She’s been an Urban Leaguer since 1962. Her involvement deepened after joining the ULN Guild in 1968. The Guild’s organized everything from a bottillon to fundraisers to nursing home visits.

“Things were hopping. We had everything going on and everything running smoothly taking part in community things, working with youth, putting on events.”

She sees it all happening again.

Kathy J. Trotter also has a long history with the League. She reactivated the guild, which is ULN’s civic engagement-fundraising arm. She said countless volunteers, including herself, have “grown” through community service, awareness and leadership development through Guild activities. She chaperoned its black college tour for many years.

Trotter likes “to share our vision that a strong African- American community is a better Nebraska” with ULN’s diverse collaborators and partners.

Much of ULN’s multicultural work happens behind-the-scenes with CEOs, elected officials and other stakeholders. ULN volunteers like Trotter, Mrs. T and Pat Brown as well as Warren and staff often meet notables in pursuit of the movement’s aims.

“I don’t think people realize the amount of work we do and the sheer number of programs and services we provide in education, workforce development, violence prevention,” Jason Hansen said. “We have programs and services tailored to fit the community.”

Most are free.

“When you talk about training the job force of tomorrow, it begins with youth and education,” Hansen said. “We’ve seen a significant rise of African-Americans with a four-year college degree. That’s going to provide a better pipeline of talent to serve Omaha.”

Warren devised a strategic niche for ULN.

“We narrowed our focus on those areas where we not only felt we have expertise but where we could have the greatest impact,” he said. “If we have clients who need supportive services, we simply refer them.”

Some referrals go to neighbors Salem Baptist Church, Charles Drew Health Center, Family Housing Advisory Services, Omaha Small Business Network and Omaha Economic Development Corporation.

“We feel we can increase our efficiency and capacity by collaboration with those organizations.”

EDUCATION

Since refocusing its efforts, ULN regularly lands grants and contracts to administer education programs for entities like Collective for Youth.

ULN works closely with the Omaha Public Schools on addressing truancy. It utilizes African-American young professionals as Youth Attendance Navigators to mentor target students in select elementary and high schools to keep them in school and graduating on time.

Community Coaches work with at-risk youth who may have been in the juvenile justice system, providing guidance in navigating high school on through college.

ULN also administers some after school programs.

“Many of these kids want to know someone cares about their fate and well-being,” Warren said. “It’s mentoring relationships. We can also provide supportive services to their families.”

The Whitney Young Jr. Academy and Project Ready provide students college preparatory support ranging from campus tours to applications assistance to test prep to essay writing workshops to financial aid literacy.

“Many of them are first-generation college students and that process can be somewhat demanding and intimidating. We’re going to prepare the next generation of leaders here and we want to make sure they’re ready for school, for work, for life.”

Like other ULN staff, Academy-Project Ready coordinator Nicole Mitchell can identify with clients.

“Growing up in the Logan Fontanelle projects, I was just like the students I work with. There’s a lot I didn’t get to do or couldn’t do because of economics or other barriers, so my heart and passion is to make sure that when things look impossible for kids they know that anything is possible if you put the work and resources behind it. We make sure they have a plan for life after high school. College is one focus, but we know college is not for everyone, so we give them other options besides just post-secondary studies.”

“We want to make sure we break down any barrier that prevents them from following their dreams and being productive citizens. Currently, we have 127 students, ages 13 to 18, enrolled in our academy.”

Whitney Young Jr. Academy graduates are doing well.

“We currently have students attending 34 institutions of higher education,” said ULN College Specialist Jeffrey Williams. “Many have done internships. Ninety-eight percent of Urban League of Nebraska Scholarship recipients are still enrolled in college going back to 2014. One hundred percent of recipients are high school graduates, with 79% of them having GPAs above 3.0.”

Warren touts the student support in place.

“We work with them throughout high school with our supplemental ed programs, our college preparatory programs, making sure they graduate high school and enroll in a post-secondary education institution. And that’s where we’ve seen significant improvements.

“When I started at the Urban League, the graduation rate for African-American students was 65 percent in OPS. Now it’s about 80 percent. That’s statistically significant and it’s holding. We’ve seen significant increases in enrollment in post-secondary – both in community colleges and four-year colleges and universities. UNO and UNL have reported record enrollments of African-American students. More importantly, we’ve seen significant increases in African-Americans earning bachelor degrees – from roughly 16 percent in 2011 to 25 percent in 2016.”

With achievement up, the goal is keeping talent here.

TALENT RETENTION

A survey ULN did in partnership with the Omaha Chamber of Commerce confirmed earlier findings that African-American young professionals consider Omaha an unfavorable place to live and work. ULN has a robust young professionals group.

“It was a call to action to me personally and professionally and for our community to see what we can do cultivate and retain our young professionals,” Warren said. “The main issues that came up were hiring and promotions, professional growth and development, mentoring and pay being commensurate with credentials. There was also a strong interest in entrepreneurship expressed.

“Millenials want to work in a diverse, inclusive environment. If we don’t create that type of environment, they’re going to leave. We want to use the results as a tool to drive some of these conversations and ultimately have an impact on seeing things change. If we are to prosper as a community, we have to retain our talent as a matter of necessity.We export more talent than we import. We need to keep our best and brightest. It’s in our own best interest as a community.”

The results didn’t surprise Richard Webb, ULN Young Professionals chair and CEO of 100 Black Men Omaha.

“I grew up in this community, so I definitely understand the atmosphere that was created. We’ve known the problems for a long time, but it seemed like we never had never enough momentum to make any changes. With the commitment and response we’ve got from the community, I feel there’s a lot of momentum now for pushing these issues to the front and finding solutions.”

“Corporate Omaha needs to partner with us and others on how we make it a more inclusive environment,” Jason Hansen said.

With the North O narrative changing from hopeless to hopeful, Hansen said, “Now we’re talking about how do we retain our African-American young talent and keep them vested in Omaha and I’d much rather be fighting that problem than continued increase in poverty and violence and declining graduation rates.

Webb’s attracted to ULN’s commitment to change.

“It’s representing a voice to empower people from the community with avenues up and out. It gathers resources and put families in better positions to make it out of The Hood or into a situation where they’re -self-sustaining.”

CAREER READINESS

On the jobs front, ULN conducts career boot camps and hosts job fairs. It runs a welfare to work readiness program for ResCare.

“We administer the Step-Up program for the Empowerment Network,” Warren said. “We case managed 150-plus youth this past summer at work sites throughout the city. We provide coaches that provide those youth with feedback and supervise their performance at the worksites.”

Combined with the education pieces, he said, “The continuum of services we offer can now start as early as elementary school. We can work with youth and young adults as they go on through college and enter into their careers. Kids who started with us 10 years ago in middle school are enrolled in college now and in some cases have finished school and entered the workforce.”

The Urban League maintains a year-round presence in the Community Engagement Center at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

Olivia Cobb is part of another population segment the League focuses on: adults in adverse circumstances looking to enhance their education and employability.

Intensive case management gets clients job-school ready.

After high school, Cobb began studying nursing at Metropolitan Community College but gave birth to two children and dropped out. Through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act program ULN administers, the single mom got the support she needed to reenter school. She’s on track to graduate with a nursing degree from Iowa Western Community College.

“I just feel like I’ve started a whole new chapter of my life,” Cobb said. “I was discouraged for awhile when I started having children. I thought I was going to have to figure something else out. I’m happy I started back. I feel like I’ve put myself on a whole new level.

“The Urban League is like another support. I can always go to them about anything.”

George Dillard said it’s always been this way.

“A lot of the stuff the Urban League does is not readily visible. But if you talk with the clients who use the Urban League, you’ll find the services it provides are a welcome addition to their lives. That’s what the Urban League is about – making people’s lives easier.”

ULN’s Rozalyn Bredow said Cobb is one of many success stories. Bredow’s own niece is an example.

“She wanted to be a nurse but she became a teen parent. She went to Flanagan High, graduated, did daycare for awhile. She finally came into the Workforce Innovation program. She went to nursing school and today she’s a nurse at Bergan Mercy.”

Many Workforce Innovation graduates enter the trades. Nathaniel Schrawyers went on to earn his commercial driver’s license at JTL Truck Driver Training and now works for Valmont Industries.

Like Warren, Bredow is a former law enforcement officer and she said, “We know employment helps curb crime. If people are employed and busy, they don’t have a whole lot of time to get into nonsense. And we know people want to work. That’s why we’ve expanded our employment and career services.”

VIOLENCE PREVENTION

The League’s violence prevention initiatives include: Credit recovery to obtain a high school diploma; remedial and tutorial education; life skills management; college prep; career exploration; and job training.

“Gun assaults in the summer months in North Omaha are down 80 percent compared to 10 years ago,” Warren said. “That means our community is safer. Also,the rate of confinement at the Douglas County Youth Center is down 50 percent compared to five years ago. That means our youth and young adults are being engaged in pro-social activities and staying out of the system – leading productive lives and becoming contributing citizens.”

Warren co-chairs the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative. “Our work is designed to keep our youth out of the system or to divert those that have been exposed to the system to offer effective intervention strategies.”

Richard Webb said having positive options is vital.

“It’s a mindset thing. Whenever people are seeing these resources available in their community to make it to greatness, then they do start changing their minds and realizing they do have other options.

“Growing up, I didn’t feel I had too many options in my footprint. My mom was below poverty level. My dad wasn’t in the house.”

But mentoring by none than other than Thomas Warren helped him turn his life around. He finished high school. earned an associates degree from Kaplan University and a bachelor’s degree from UNO. After working in sales and marketing, he now heads a nonprofit.

Wayne Brown, ULN vice president of programs, knows the power of pathways.

“My family was part of the ‘alternative economy.’ It was the family business. My junior year at Omaha Benson I was bumping around, making noise, when an Urban League representative named Chris Wiley grabbed me by the ear and gpt me to take the college and military assessment tests. He made sure I went on a black college tour. I met my wife on that tour. I got a chance to be around young people going in the college direction and I had a good time.”

Brown joined the Army after graduating high school and after a nine year service career he graduated from East Tennessee State University and Creighton Law School. After working for Avenue Scholars and the Omaha Community Foundation, he feels like he’s back home.

“I wouldn’t have been able to do all that if I hadn’t done what Mr. Wiley pushed me to do. So the Urban League gave me a start, a path to education and employment and a sense of purpose I didn’t have before.”

Informally and formally, ULN’s been impacting lives for nine decades.

“To be active in Omaha for 90 years, to have held on that long, is fantastic,” Pat Brown said. “Some affiliates have faltered and failed and gone out of business. But to think we’re still working and going strong says something. I hope I’m around for the 100th anniversary.”

Mrs. T rues the wrongs inflicted on the black community. But she’s pleased the League’s leading a revival.

“I’ve seen some good changes. It makes me feel good we are still here and still standing and that I’m around to see that. It’s a good change that’s coming.”

Visit http://www.urbanleagueneb.org.

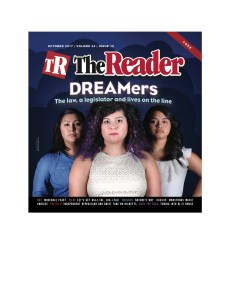

Futures at stake for Dreamers with DACA in question

Here is a followup to a story I did earlier this year about DACA or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. This executive order program of protections means everything to recipients. These so-called Dreamers and their supporters speak passionately about the need to keep DACA around and describe the devastating impact that losing it would have on recipients’ lives. President Trump has sent conflicting messages where immigration is concerned, No sooner did he decide to end the program or have it rescinded, then he gave Congress a deadline to find a compromise that would extend or solidify the program and therefore prevent young people who entered the country illegally as children from being deported and from losing certain privileges that allow them to work, obtain licenses, et cetera. My new story is part of the cover package in the October 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Futures at stake for Dreamers with DACA in question

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

When, on September 5, President Donald Trump appealed to his base by ending Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), a generation of American strivers became immigration reform’s collateral damage.

He’s since given Congress six months to enact a plan reinstating DACA protection from deportation for so-called DREAMers in exchange for more robust border security. DACA also provides permits for undocumented youth to work, attend school and obtain driver’s and professional licenses. Given the political divide on illegal immigrants’ rights, it’s unclear if any plan will provide DREAMers an unfettered permanent home here.

Thus, the futures of some 800,000 people in America (about 3,400 Nebraskans) hang in the balance. As lawmakers decide their status, this marginalized group is left with dreams deferred and lives suspended – their tenuous fate left to the capricious whims of power.

The situation’s created solidarity among DREAMers and supporters. Polls show most Americans sympathize with their plight. A coalition of public-private allies is staging rallies, pressing lawmakers and making themselves visible and heard to keep the issue and story alive.

Alejandra Ayotitla Cortez, who was a child when her family crossed illegally from Mexico, has raised her voice whenever DACA’s under assault. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln senior and El Centro de las Americas staffer has spoken at rallies and press conferences and testified before lawmakers.

“As Dreamers, we have been used as a political game by either party. Meanwhile, our futures and our contributions and everything we have done and want to do are at stake,” she said. “For a lot of us, having that protection under DACA was everything. It allowed us to work, have a driver’s license, go to school and pursue whatever we’re doing. After DACA ends, it affects everything in our life.

“It is frustrating. You’re trying to do things the right way. You go through the process, you pay the fees, you go to school, work, pay taxes, and then at the end of the day it’s not in your hands.”

If she could, she’d give Trump an earful.

“Just like people born here are contributing to the country, so are we. It’s only a piece of paper stopping us from doing a lot of the things we want to do. As immigrants, whether brought here as an infant or at age 10, like myself, we are contributing to the nation financially, academically, culturally. All we want is to be part of our communities and give back as much as we can. It’s only fair for those who represent us to respect the contributions we have made and all the procedures we’ve followed as DACA recipients.”

Justice for Our Neighbors (JFON) legal counsel Charles Shane Ellison is cautiously optimistic.

“I’m hopeful lawmakers can do whatever negotiating they need to do to come up with a common sense, bipartisan path to protect these young people. It makes no sense whatsoever to seek to punish these young people for actions over which they had no control.

“These are, in fact, the very kinds of young people we want in our country. Hard working individuals committed to obtaining higher education and contributing to their communities. It’s incumbent upon lawmakers to find a fair solution that does not create a whole category of second class individuals. Dreamers should have a pathway to obtain lawful permanent resident status and a pathway to U.S. citizenship.”

Tying DACA to border control concerns many.

“I wouldn’t feel comfortable if that was a compromise we had to arrive at,” Cortez said, “because it’s unnecessary to use a national security excuse and say we need increased border enforcement when in reality the border’s secure. It would be a waste of tax money and energy to implement something that isn’t necessary.”

Ellison opposes attempts to connect the human rights issue of DACA with political objectives or tradeoffs.

Not knowing what Trump and the GOP majority may do is stressful for those awaiting resolution.

“It’s always having to live with this uncertainty that one day it could be one thing and another day something else,” Cortez said. “It can paralyze you sometimes to think you don’t know what’s going to happen next.”

“We could have made this a priority without inserting so much apprehension into a community of really solid youth we want to try to encourage to stay,” Ellison said.

To ease fears, JFON held a September 7 briefing at College of Saint Mary.

“It was an effort to get information in the hands of DACA recipients and their allies,” Ellison said. “We had more than 400 people show up.”

Moving forward, he said, “it’s imperative” DREAMers get legal advice

“Some studies show 20 to 30 percent of DACA youth could be potentially eligible for other forms of relief that either got missed or they’ve since become eligible for after obtaining DACA. If, with legal counsel, they decide to renew their Deferred Action, they have until October 5 to do so. We provide pro-bono legal counsel and we’ll be seeing as many people as we can.”

Ellison said nothing can be taken for granted.

“It’s so important not just for DACA youth to take certain action For people who want to stand with DACA youth, now is not the time to be silent – now is the time to contact elected representatives and urge them to do the right thing.”

Alejandra Escobar, a University of Nebraska at Omaha sophomore and Heartland Workers Center employee, is one of those allies. She legally emigrated to the U.S. six years ago. As coordinator of Young Nebraskans in Action, she leads advocacy efforts.

“Most of my friends are DREAMers. I started getting involved with this issue because I didn’t know why my friends who were in this country for all their lives couldn’t be treated the same as I was. I didn’t think that was fair. This is their home, They’ve worked and shown they deserve to be here.

“There has been a lot of fear and this fear keeps people in a corner. I feel like what we do makes DACA recipients know they’re not alone. We’re trying to organize actions that keep emphasizing the importance of the protection for DACA recipients and a path to citizenship and that empower them.”

She feels her generation must hold lawmakers accountable.

“I’d like lawmakers to keep in mind that a lot of us allies protecting DREAMers are 18-19 years old that can vote and we’re going to keep civically engaged and emphasizing this issue because it’s really important.”

As a UNO pre-law student who works in an Omaha firm practicing immigration law, Linda Aguilar knows the fragile legal place she and fellow DREAMers occupy. She was brought illegally to America at age 6 from Guatemala and has two younger siblings who also depend on DACA. But she’s heartened by the support that business, labor and other concerns are showing.

“It has inspired me to continue being active and sharing with elected officials how much support there is for the DACA community.”

She hesitated speaking at a public event making the case for DACA before realizing she didn’t stand alone.

“Just knowing that behind me, around me were other DREAMers and I was there supporting them and they were there supporting me made me feel a lot stronger. Because we’re all in the same position, we all know what it feels like, we all walk in the same shoes.”

Alejandra Ayotitla Cortez won’t just be waiting for whatever happens by the March 5 deadline Trump’s given Congress.

“I am hoping for the best, but I am also taking action. not only me just hoping things will get better, it’s me educating my community so they know what actions we can take, such as calling our elected representatives to take action and to listen to our story and understand how urgent this is.”

Cortez, too, finds “encouraging” support “from people across the state, from leaders, from some of our state senators in Lincoln, from UNL professors and classmates.”

The Nebraska Immigration Legal Assistance hotline is 1-855-307-6730.

Frank LaMere: A good man’s work is never done

Frank LaMere: A good man’s work is never done

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Frank LaMere, self-described as “one of the architects of the effort to shutdown Whiteclay,” does not gloat over recent rulings to deny beer sellers licenses in that forlorn Nebraska hamlet.

A handful of store owners, along with producers and suppliers, have profited millions at the expense of Oglala-Lakota from South Dakota’s nearby Pine Ridge Reservation, where alcohol is banned but alcoholism runs rampant. A disproportionate number of children suffer from Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS). Public drunkenness, panhandling, brawls and accidents, along with illicit services in exchange for alcohol, have been documented in and around Whiteclay. Since first seeing for himself in 1997 “the devastation” there, LaMere’s led the epic fight to end alcohol sales in the unincorporated Sheridan County border town.

“This is a man who, more than anyone else, is the face of Whiteclay,” said Lincoln-based journalist-author-educator Joe Starita, who’s student-led reporting project — http://www.woundsofwhiteclay.com — recently won the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Journalism grand prize besting projects from New Yorker, National Geographic and HBO. “There is nobody who has fought longer and fought harder and appeared at more rallies and given more speeches and wept more tears in public over Whiteclay than Frank LaMere, period.”

LaMere, a native Winnebago, lifelong activist and veteran Nebraska Democratic Party official, knows the battle, decided for now pending appeal, continues. The case is expected to eventually land in the Nebraska Supreme Court. Being the political animal and spiritual man he is, he sees the Whiteclay morass from a long view perspective. As a frontline warrior, he also has the advantage of intimately knowing what adversaries and obstacles may appear.

His actions have gotten much press. He’s a key figure in two documentaries about Whiteclay, But his social justice work extends far beyond this specific matter.

“I’ve been involved in many issues in my life,” he said.