Archive

Standing on Faith, Sadie Bankston Continues One-Woman Vigil for Homicide Victim Families

For years I read about this Omaha woman who has dedicated her life to help the families of homicide victims since she losing her own son to a senseless act of violence and finding the support network for grieving loved ones to be wanting. I finally met Sadie Bankston a couple years ago and this is her story. It originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com), and I think you will find her as determined and compassionate as I did. She goes to rather extraordinary lengths to help people, mostly women, who in a very real way become the secondary victims of homicides. Her clients may have lost a son or a daughter or a mate, and without the help she and thankfully some others now provide, these hurting parents and spouses are in danger of being casualties themselves. Sadie carries on her work through her own nonprofit, PULSE, and she can always use more donations and resources to help out families trying to cope with the trauma of losing someone dear and often having to relive it through criminal investigations and court proceedings.

Standing on Faith, Sadie Bankston Continues One-Woman Vigil for Homicide Victim Families

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Whenever Omahan Sadie Bankston hears of a new homicide, her heart aches. Her son Wendell Grixby was shot and killed in 1989 in the Gene Leahy Mall. He was 19. An outpouring of support followed. Then Sadie was on her own. Paralyzed by pain. She sensed others expected her to move on with her life after a certain point. The rest of her adult kids had lives, families, careers of their own. She was single. There wasn’t anyone around to confide in who’d been in her place — another parent who’d suffered the same nightmare of a murdered son or daughter.

Violent crimes in Omaha only escalated. A growing number, gang-related. Others, domestic disputes or random acts turned deadly. Guns the main weapons of choice in the mounting homicide tallies. Sadie felt called to do something for others left adrift in the wake of such loss. She identified with their heartbreak.

Without a degree, she couldn’t provide formal mental health assistance, but she could reach out — mother to mother, heart to heart. Talking, praying, holding hands, preparing care packages, extending a lifeline for people to call day or night. Bearing witness for families at court hearings.

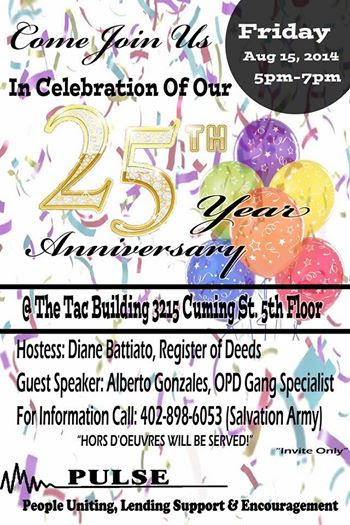

She’s been doing all this and more through the nonprofit organization she started in 1991 — PULSE or People United Lending Support and Encouragement.

Mary E. Lemon’s daughters Saundra and Renota Brown were stabbed to death last Christmas Eve in the basement of an Omaha home. The grieving mother has relied on Sadie to get through many long days and nights.

“Sadie has been a help,” said Lemon. “I call her and talk to her whenever I feel I need to talk to somebody, and that happens quite often. It helps to know that there is someone out there who cares — that you can talk to. And Sadie’s made me feel as if I could talk to her at anytime. She’s a friend worth having, I’ll tell you.”

PULSE began as a support group for mothers who’ve lost a child to homicide. The meetings “phase in and out” now due to funding limitations. Sadie hopes to start the sessions again. She knows how vital these unconditional forums can be.

“You hear their loneliness, their pain, their sleeplessness, their hopelessness. Will I ever stop crying? Those kinds of things. It’s just to come together with other parents who have lost. We have a common denominator there.”

Virgil Cook Jr. and his wife Patricia fell into a depression after their son, Little Virgil. was shot and killed in 1991. They thought they were alone in their grief until Sadie introduced the Native American couple to others suffering like them.

‘We found there are other people like us who’ve been through the same thing. White people, black people, Spanish people. We’re all in the same boat. We’ve become friends,” said Cook.

Sadie’s only guide in the beginning was her own experience. “Just the pain that I knew that I felt,” she said. “I knew other mothers were feeling the same, so I just wanted to help in some way to steer them in the right path as far as help and support.” She knew the most powerful thing she could offer was having walked the same painful journey they’re on. “When you can embrace someone and say, ‘I know how you feel.’ and really know it, it makes a difference,” said Sadie, whose eyes ooze empathy and mirror survival. “I always say, ‘The pain won’t go away, but it will get softer.’”

Lemon said she appreciates dealing with someone who’s walked in her shoes. Their conversations can be about anything or nothing at all. “I talk to Sadie at least once if not twice a week,” she said.

“We talk about my girls, we talk about old days, growing up in the old neighborhood, we talk about a lot of things. Just to kind of relieve my nerves, you know.”

Once Sadie enters a family’s life she sticks. Even years later, despite moves, remarriages, the bond remains.

“They’re not left alone with me around,” she said, “because I’m calling them.”

PULSE volunteer Denise Cousin got acquainted with Sadie while an Omaha police captain. Now retired, Cousin feels Sadie builds rapport by carrying no institutional agenda or baggage. She’s open, she’s real, she’s honest. She’s just Sadie.

‘“I think because she is not representing any type of governmental entity, there’s no concern the family’s going to be jeopardized as far as what they tell her. She does not have that attachment. And I think it is her personality. She is down to earth. She lets the family know she’s there for them. She kind of comes across as the mother figure. She comes across as family, and so she breaks that barrier of a professional I’m-here-to-tell-you-something.”

Cook said he and his wife regard Sadie “as an older sister” even though they have a few years on her. He credits her with getting them out of the deep funk they fell into after Little Virgil was killed.

“We didn’t want to work, we didn’t want to go anywhere, we didn’t want to do anything. Things got real bad. She helped us out of that ugly state. She’s been like an angel to us. Everybody needs a Sadie.”

With her warm, soulful, old-school way, it’s easy picturing Sadie as everyone’s auntie or big mama or sistah. A girlish, impish side shines when she laughs. She’s no pushover though. A steely, sassy righteousness shows through when describing disrespectful “bagging and sagging” young men, silly girls getting pregnant and senseless gun play taking lives and wrecking havoc on families and neighborhoods.

This woman of faith ascribes her own healing to her higher power. “My source, and still is my source of comfort and strength,” she said, casting her eyes heavenward. A hardness shows, too, when she bemoans PULSE’s chronic financial straits. PULSE grew beyond being merely a support group to a multi-faceted human services operation providing food, clothes and other support. Ambitious programs, including at-risk workshops, were drawn up.

But as a largely one-woman band, Sadie’s left to scratch for dollars and volunteers wherever she can find them. There’ve been many supporters. Churches, businesses, individuals. Lowes donated materials to renovate the house she resides-offices in. Sadie and fellow victim moms did all the labor. Lamar Advertising does billboards for Stop the Violence messages. Popeye’s Chicken donates dinners for We-Care packages PULSE delivers to families.

An annual Mother’s Day banquet she hosts relies on donated food and facilities. Lately though she’s cut back PULSE services.

All the begging, all the scrounging, all the promised donations that don’t come through, all the unrealized dreams get to be too much at times. “I’m just tired of constantly having to ask.” Then there’s her own well-being. She was 46 at PULSE’s start. She’s 63 now. Like many caregivers the last person she thinks of is herself. She realizes that has to change. “I figure I should be taking care of myself because I’m a senior citizen now. I’m just tired.”

A bad back prevents her from working. She’s on disability. Despite this hand-to-mouth existence the work of PULSE goes on, largely unheralded. Oh, she receives glowing endorsements.

Omaha Police Department Sgt. Patrick Rowland said, “What makes Sadie effective is she’s determined to make a difference even when it’s not the most pleasant of times. She gets out there and she still tries. She truly cares for people. She doesn’t judge them or the circumstances in which their loved ones lost their life. She sees the families as being victims also. She cares about the police, too. She wants them to do a good job. She understands the difficulty in trying to solve these things.”

Sadie’s declined Woman of the Year citations. She’s not looking for awards or pats on the back, but tangible support. The situation’s akin to the way parents feel when a child’s been murdered. Life must go on but until someone notices their pain, it’s hard to want to go forward. Attention must be paid. She said one of the hardest things in the aftermath of her son’s murder was the unpleasant realization the world was oblivious to her sorrow. Instead of validating her trauma, life ground on as usual. It made the void that much more cruel. In her outreach work Sadie’s found nearly everyone experiencing a loss feels a sense of emptiness and abandonment at their suffering being ignored or minimized. It’s as if society tells you, “they’re gone,” so get on with your life, she said.

“When I talk to mothers they explain it the same way. When my son was murdered I was driving somewhere and the street lights were still coming on and I wondered, Why is this going on just like nothing happened? People are still walking and laughing like nothing had happened. It’s a sad feeling, yeah. I wouldn’t say so much lonely. It’s just more, Here, feel my pain — recognize I’m hurting here. Instead of people still eating their ice cream like nothing has affected you, you want everybody to stop and acknowledge what you’re going through.”

She inaugurated the Forget Us Not Memorial Wall shortly after launching PULSE. The commemorative marker ensures victims like her son “will not be forgotten.” Resembling an opened Bible, the tall, custom-made wooden memorial has hinged panels that presently display 150 name plates, most accompanied by a likeness of the victim. The majority of victims are African-American. Two OPD officers slain in the line of duty — Jimmie Wilson Jr. and Jason Pratt — are among those memorialized. A small collection box next to the memorial accepts donations.

Sadie contacts families for permission to affix their loved ones’ names to the wall. The memorial’s had different homes. It’s now displayed at St. Benedict the Moor, 2423 Grant St. The church’s pastor, Rev. Ken Vavrina, champions Sadie’s work. “She has a good heart, she’s compassionate, and she’s been there,” he said. “And she’s worked now over the years with so many families who have a lost a child she really is good at it. She’s developed the expertise of being able to reach out and support these families who have had someone killed. It’s a great idea. I don’t know of any other organization that is doing what she’s doing — certainly not as consistently as she does. We’re honored to have it (the wall) here.”

He and Sadie admit the wall’s not up to date. So many killings. So hard to keep up. “I had no idea it was going to be filled up (so quickly) that we had to have two more extensions put on it. I was just thinking in the here and now,” she said.

In the years following Wendell’s death Omaha homicides exploded. There were 12 in 1990, 35 in 1991 and an average of 31 over the next 17 years, with the count reaching a record 42 last year. 2008 has already seen 40-plus homicides. With more frequency than ever killings happen in waves. This year alone has seen a handful of weeks with multiple fatalities each. “I just don’t know what to say or think about the recent rash of homicide that is plaguing our community,” Sadie said in response to a flurry of gun deaths in early November.

A problem once seen confined to northeast Omaha appears more widespread, including recent incidents in Dundee and south Omaha and, most starkly, the deadly spree at the Westroads Von Maur in 2007. Community responses to the problem are evident. Prayer vigils, anti-violence summits, stop-the-violence campaigns, sermons, editorials, articles, proposed ordinances to stiffen gun laws, public discussions on ways to stem the flow of guns and, ironically, increased gun sales/registrations as people arm themselves to feel safer.

She doesn’t like turning anybody away. “I refer people PULSE cannot help to The Compassionate Friends (a national nonprofit grief assistance group with an Omaha chapter). I don’t let them just drown out there. I don’t say we can’t help you and let it go.” There’s not much she lets go of once she latches onto something.

“I have to say I admire Sadie’s persistence, because she has encountered numerous roadblocks and obstacles. Not getting paid a dime for this. Very little if any type of donation comes her way. This is strictly a heartfelt humanitarian effort that she continues to push on, day after day, year after year. I think most of us would say, ‘That’s it, I’m tired, I’m ready to go on to other things,’” said Denise Cousin. That’s why when Sadie reached a point of no return last summer, Cousin was sympathetic.

A March car accident left Sadie with severe injuries, including two torn rotator cuffs. “I’m in pain now. The accident had a lot to do with it. Then I have nerve damage from having two teeth pulled.” Bad enough. But when Sadie learned the office the Salvation Army let PULSE use starting a year ago would no longer be available, it was more than she could take. She’d talked about closing PULSE before but this was different. “This time I was really at my lowest,” she said. After all, a body can only take so much. It’s why on June 25 she called reporters and friends together to announce PULSE’s end. “I’m tired of the struggle,” she told the gathering. Among those in attendance were some of the parents she’s comforted over the years. They expressed appreciation for all PULSE has done.

Cousin let her know it was OK to walk away. “I was in her corner there saying, You have put in a sufficient amount of time. I can understand you being tired.” Vavrina empathized, too. “Sadie got discouraged and I can understand she gets discouraged, because she’s financially strapped all the time. She doesn’t get the support she needs,” he said. “We try to help her as much as we can.” “But then she called me and said she just couldn’t put it down. She still felt compelled to help families,” said Cousin.

Soon enough, the word got out — Sadie was back and recommitted to serving what’s become her life’s mission. What helped change her mind were messages from friends, associates and complete strangers. One, from a woman who identified herself as Eunice, stood out: “I’m calling you Miss Bankston because you were placed in that position for a reason. God put you there, sweetheart. Don’t get weary yet. I get weary at times, too. I know you’re tired. You become tired when you’re trying to do something all by yourself, baby, but you’re not by yourself. God doesn’t want you to get weary. He’ll lift you up. It seems nobody cares but we do care, because that’s our future out there dying daily. We see it. And it’s time for us as women to come together and stop it. Please don’t give up yet, Miss Bankston. I beg you in Jesus’ name.”

Buoyed by such words Sadie’s staying the course, even though she still battles health problems, still pleads for money, still gets frustrated fighting the good fight on little more than goodwill and prayer. But she can’t bear to turn her back on the truth: the killings go on unabated and each time a family’s left to pick up the pieces. “So I must go on. Life goes on. You know I must love what I’m doing or I wouldn’t be doing it for this long,” said Sadie. “I love what I do. You know it’s not for money. Anytime you can reach out and help people it is just so nice. That’s what we’re put here for — to love our brothers and sisters.”

Lemon wouldn’t have blamed her if she had quit but added, “I’m glad she didn’t. Sadie does a job that a lot of people probably wouldn’t even consider doing. Sadie is a special person, That job is meant for Sadie. She does such a good job.”

Sadie plans going about it smarter now though. For years she resisted advice that she should write grant applications for operating funds. Recently, she devised a budget for a year-long project grant. If she gets the monies PULSE will gain the financial stability it’s never enjoyed before. She needs it to ease her mind.

“I’m not going to overstress myself because if I’m no good for myself I’m no good for anyone else. I just can’t do it anymore. I’m not gong to do it anymore.”

Vavrina’s sure it’s a sound strategic move. “Now that she’s doing it the right way,” he said, “I think she can get funded.” He’s encouraged Sadie has a contingency plan “that would permit PULSE to continue without her.”

Forget Me Not Memorial Wall

Her friends know she’s given so much of herself for so long she may not have much left to give. Crisis intervention takes a toll. What some don’t know is that she’s seen some hard things no one should see. “Well, why shouldn’t I see it? I mean, it happens,” she said. PULSE was part of a University of Nebraska Medical Center pilot program that trained folks like her to respond to homicide events. She was on call trauma nights. When the phone rang with a new assignment it meant going to hospitals at all hours to console loved ones. On at least one occasion, she said, “I had to tell the family their loved one was gone. I did. l mean, its really hard comforting people who’ve just lost a son or daughter. Sad, sad, sad.”

Her work at times meant going to crime scenes, where families lived amid fresh evidence of carnage. Even there, she tended to their needs. “There would be blood on the floor from shootings. There was so much it just glistened from the lights.”

She recalled the case of a young mother from Chicago. The woman’s husband kidnapped their baby and fled to Omaha. She followed, with her other kids in tow. After finding and confronting him here, he slit her throat in front of the kids. Sadie managed getting the kids released from the foster care system. Said Sadie, “Now you know how hard that is to do, don’t you? To get someone out of foster care once they’re in? I got ‘em out. I have a gift for gab when something needs to be done.” The victim’s family contacted Sadie asking her to retrieve items from the murder site. “We went into the apartment. It was all white, except where it was saturated with blood. Blood splattered all over. And we retrieved the kids’ clothes and the toys and I sent them back to Chicago. I still keep in contact with the grandma. The kids are grown now.”

Another time, Sadie observed how difficult it was for a family to be surrounded by the stain of murder in their Omaha Housing Authority unit. “Two young men were killed at home, and the blood — it was hard for the mother, for the family to see, so I contacted OHA and they came out and cleaned up everything.” Sadie had noticed a throw rug the mother avoided walking on. Sadie had trod over the same rug and it wasn’t until she got home, she said, “I realized that must have been where her son was murdered. So I called her back and I apologized, and she said, ‘That’s OK, Sadie.’”

In this conspiracy of broken hearts, Sadie said, “there’s that camaraderie” that makes explanations unnecessary. “They (OHA) had to take the carpet up because it soaked through,” Sadie said. She demonstrates she’s not just there for families once, never to be seen or heard from again. She’s there for the long haul. “If they ask for me to attend the funeral I will, and I do.” Celebrations, too. She’s cooked holiday dinners for families. She’s bought groceries, clothes. She even had a wheelchair ramp built for a family. Around her home are tokens of families’ appreciation for her going the extra mile.

Being a court advocate is another example of Sadie going beyond the call of duty. She understands the strain of seeking justice for a loved one. She attended every proceeding for her son’s assailant. To her other children’s dismay she forgave the young man, who was convicted of manslaughter and is now free. So she attends court with families — to be a pillar of strength, a shoulder to cry on. She knows the last thing a family under extreme emotional distress needs is to see her cry. “Normally I stifle my tears,” she said. She couldn’t once, she said, when it was read into evidence a female shooting victim’s “last words were, ‘It burns.’ I handed tissues to the family and I had to turn my head so they wouldn’t see my tears. It’s hard for me to find someone to go with me because I can’t have them crying.”

Sadie also treads a delicate line as a liaison between families and law enforcement officials investigating unsolved homicides. She’s well aware “snitching” is seriously frowned on by some in the African American community. “A lot of people don’t like the police and I try to be the mediator to keep an open line of communication with the police department,” she said. She said sometimes family members with information about a case tell her what they won’t disclose to police. With a family’s consent, she shares leads. “As a mother how would you feel if someone killed your child and no one came forward?”

OPD’s Sgt. Rowland, who worked with Sadie when he was in homicide, said, “She understands the situation that some of these families are put in, just by the nature of where they live and what their loved one, the homicide victim, was involved in. Sadie does what she can to get them to cooperate with the police. She’s very honest with us. Very blunt.” “She will continue to beat down a door until the information is laid at the footsteps of the police department,” said Cousin.

Sadie’s also known to put herself in harm’s way breaking up scuffles between kids before they escalate into something worse. “I try to intervene. Once, I got flung around and I landed on the hood of the car. But I got back up. I broke up the fight. The cops came. Everybody was OK,” she said. “All I’m trying to do is get ‘em to just think. When I say I lost my son some of them seem to have compassion or pity for me.” Once, a gun was pulled on her. The windows of her home have been shot out. She won’t be intimidated. Would she get involved in the middle of a dispute again? “Probably, and 100 percent if a woman we’re being hit by a man. There would be no doubt.”

She still has dreams for PULSE. She envisions youth life coaching classes. “Make them feel better about themselves, so they’ll make better choices and won’t settle for anything,” she said. “So, that’s a goal. My theory now is if we pay attention to the children maybe there’d be less grief support meetings we have to have.” Cousin suspects Sadie will go right on with PULSE till her dying days.

“As long as we continue to have homicides in this community and as long as there’s breath in her body Sadie will continue to help the families. She’s quite remarkable and definitely unforgettable.” Miss Sadie may not have everything to give she’d like but, she said, “I have my heart and my family. And I have hope. Keep hope alive. I guess I have to stand on faith.”

Related Articles

- Unsolved murder is not forgotten, family says at vigil (mysanantonio.com)

- N.J. 211 hotline expands as one-stop shop for social services information (nj.com)

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Miss Leola Says Goodbye (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Crowns: Black Women and Their Hats (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- An Inner City Exhibition Tells a Wide Range of Stories (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Whatsoever You Do to the Least of My Brothers, that You Do Unto Me: Mike Saklar and the Siena/Francis House Provide Tender Mercies to the Homeless

Before I did the following story on Mike Saklar, I only knew him from media reports about the Siena/Francis House homeless facility he ran then and continues running today. Even in sound bites he comes off as a thoughtful, highly competent man deeply committed to his work. When I finally met him a couple years ago to interview him and spend some time around the shelter and residential treatment program there, I found he was all those things and more. This is quite an extensive profile of him and his work, and yet this was one of those occasions when I never heard word one back from him or anyone else for that matter at the Siena/Francis House about my story. That lack of feedback is in itself not that unusual per se, but for a story of this length it definitely is. So, if you happen upon this Mr. Saklar or perhaps one of your colleagues or supporters do, shoot me a comment or two, just so I have the satisfaction of knowing that at least somebody there read it.

Mike Saklar

Whatsoever You Do to the Least of My Brothers, that You Do Unto Me: Mike Saklar and the Siena/Francis House Provide Tender Mercies to the Homeless

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

The plight of the homeless tends to make news seasonally, during winter and summer, and then fades away the rest of the year. Out of sight, out of mind. Trouble is, even when the homeless stand in plain view you likely don’t see them. That’s because society makes them invisible, untouchable.

If you take a good look, though, the homeless are easy to spot downtown. They’re fixtures in the Gene Leahy Mall, hanging out, panhandling, lining up for free lunches. They camp out at the W. Dale Clark Library, reading, dozing, drying out, coming down. These discarded, dispossessed figures occupy a limbo, killing time between some indeterminate goal or destination — perhaps a ride, a meal, a roof over their head or their next fix.

They’re an inconvenient reminder the fabric of America is torn, its safety net not catching everyone who suffers a fall.

The homeless often habituate Omaha’s east corridor, where several nonprofits serve the population. The state’s largest homeless shelter, the Siena/Francis House, is situated on the fringes of NoDo or North Downtown. This multiplex at 17th and Nicholas St. is an oasis for the lost and the misbegotten.

Siena/Francis executive director Mike Saklar has never been homeless himself but he’s seen the lives of street people wrecked by neglect and transformed by support. After 28 years in the Omaha City Planning Department, where he began working with area homeless programs, he now focuses on breaking the cycle of homelessness. That’s the mission of Siena/Francis, which he’s directed since 2002.

It wasn’t like the job was a long-held dream. But being there doing this work makes sense given his background and the choices he’s made. Siena/Francis men’s shelter manager James Hayes said he believes Saklar “has been in training for this job since day one. All of his experiences in life up to the day he took this job prepared him in some way or another to be one of the most sincere, compassionate, hard working, help-anyone-in-any-way-he-can individuals I have ever met.”

Saklar confirmed he’s “experienced different things during my life” that have helped him connect with the poor and to value them as human beings. Giving to the less fortunate is a practice his elders modeled. His father was a traveling salesman, his mom a stay-at-home matriarch.

“My extended family’s always been big in helping others,” he said. “My grandfather was director of one of Omaha’s early homeless shelters in the 1930s. My parents and grandparents helped and befriended many people, often opening their homes to them. I open my home to a select few who I know well. I do bring some homeless to dinner on Christmas and Thanksgiving.”

He came into contact with more homeless working at Peony Park, near where he grew up. The amusement park’s owners, the Malecs, used to hire what were called ‘bums” then. They worked the grounds and the gardens.

Though a teen at the time, Saklar did a man’s job at the amusement park, sometimes working alongside the transients.

“I put in 10-12 hour days. It was a lot of hard work. I did everything from operating rides to putting out a couple thousand pounds of charcoal in these great big pits, preparing barbecue sauce from scratch in these giant vats, to cutting up chickens, washing them, cooking them, making potato salad for 2,500 people, to working as a bus boy for the bartenders at night. I’d bring up the ice and the beer from the basement, pop the popcorn, clean up afterwards. I did all that.

“It was really a life experience…meeting lots of people.”

Doing manual labor, being around diverse people set the tone for his adult life. “I love different cultures and I know a lot of people from a lot of different cultures,” he said. A person he got “particularly close to” at Peony Park was a homeless man who worked there. Saklar said, “When I was about 13-years-old I had my first homeless friend, Joel Craig. I liked him. We got to be talking friends. We talked a lot. I don’t remember how he got to be homeless.”

Saklar lost touch with Craig. Years passed before they were reunited. By then it was the ‘70s and Saklar was an Omaha Community Development trainee with the City. His job — relocating east Omaha residents to make way for progress. Eppley Airfield expansion meant displacing hundreds of families. In the process of notifying homeowners he came upon Craig living in a tiny but tidy bungalow that had to go.

“He had somehow put his life together a little bit, still at a very low level, but he’d married and he and his wife lived together in this house,” Saklar recalled. “I thought it was so cool to run into him again later and to be able to help them get another house. I helped them move.”

Living conditions in east Omaha then, he said, were akin to Appalachia with its crushing poverty, only minus the coal dust and hills. The small shotgun houses were substandard. Being exposed to such hardships opened Saklar’s eyes.

“This was two minutes from downtown and they didn’t have sewers. Some of them still had outhouses, dirt floors. I was in houses where there were five kids sleeping on a dirt floor in the basement. With the jet liners rumbling over your head every 15 or 20 minutes you couldn’t talk or hear. It would just vibrate like heck. Some homes were heated just by wood space heaters. Residents chopped the lumber.

“It was really a backwards community, and it was very very poor. I was amazed. It would have been the most blighted, poorest census tract in Douglas County by far, maybe one of the poorest in the state per capita.”

Despite the disruption to people’s lives and the rupture to communities that went with razing people’s homes to make way for public works projects, Saklar believes dislocated residents came out ahead in the long run.

“It was a great experience because you’re not just kicking people off this land — you’re working with them and helping them to better themselves, and with all the federal laws you’re providing relocation assistance in order to help them buy a decent home,” he said.

Before he ever got into city planning Saklar embarked on a path that made him empathetic to people living on the margins. After graduating Westside High School in the late ‘60s he enrolled at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He paid his own way and when his funds ran dry he dropped out. No sooner did he leave school then Uncle Sam drafted him into the U.S. Army. The Vietnam War was escalating. Seeing action was a real possibility.

He ended up in airborne training and made the cut as a paratrooper in the famed 82nd Airborne division. In ‘69 he shipped overseas to Korea, via Japan. He couldn’t wait for his chance at combat duty in ‘Nam. As fate had it, he never got the call.

“I was very disappointed. If you go through airborne training and then to the 82nd Airborne you’re ready to go anywhere and to do whatever you have to do.”

Instead, he tested into an operations intelligence specialist post with the 7th infantry division’s command in Seoul. He rated top secret clearance. The work was interesting but what most fascinated him was the Korean culture. “I liked to walk around and peruse through the markets, see the action, right.”

Everything the naive 21-year-old saw made an impression. He came across situations that would inform his later work with Omaha’s homeless. South Korea was still reeling from the war that ended 16 years before and, thus, unchecked diseases, shortages of basic goods and other hardships were rampant.

“When I was overseas I ran into leper camps, really terrible situations, lots of homeless people, and I think maybe that helped create something inside me, right.”

The resiliency and ingenuity of the Korean people struck Saklar. After meeting his wife there and visiting several times over the years he remains impressed today.

“I admire the work ethic of the Korean culture. It doesn’t seem to matter if a person’s job is street sweeper, teacher, businessman or doctor, they will do their very best and do it in a very professional way. I don’t know how to explain this. Koreans are very respectful of others, and if you walk around, say, in Seoul, the capital city, you will be hard-pressed to find trash blowing around. It is a very clean city. Korea offers a lot to admire. The culture goes back some 5,500 years. I love Korean history, architecture, anthropology, geography, sociology, et cetera.”

He said Koreans well-deserve their reputation for being driven to achieve, especially in the classroom. “They are way too smart.”

During his overseas tour Saklar met a bright Korean national attached to his unit, Han Chil Song, who let the curious American know his sister, Chong, worked in a Seoul tailor shop. “She measured me up for a number of suits,” said Saklar. “For some reason, I kept going back to purchase some very nice and very inexpensive suits.” Love bloomed. The pair married. Her brother died tragically.

Saklar learned the harrowing story of how Chong’s family escaped North Korea after the Communists came to power and implemented a purge that targeted figures like Chong’s banker father. Chong was not yet born. The family made it to Seoul, South Korea, where they survived the war.

“I think it was rough going,” said Saklar. “I mean, that whole country was devastated and destroyed. I was just there, and the mountains surrounding Seoul still don’t have any trees on them yet. They’re just bare. The trees were blasted out or people cut them down to survive. It’s unbelievable.”

Saklar became a father shortly before his Army release. In the States his small family settled in Omaha, where his Greek-American clan embraced his Korean wife and Amerasian son. “I think it was pretty exciting for all of them, especially since we had a child.” His Korean wife and biracial kids — he and Chong have three grown children — have been subject to some prejudice, he said, but mostly welcomed.

Back home, Saklar returned to school on the G.I. Bill but with a family to support he needed a job. He tried driving a taxi, working construction — “whatever I could do just to make ends meet,” he said. He began his own roofing business. “I was struggling. I went to Nebraska Job Service and I saw an opening for this new city department (Omaha Community Development), and I was the last person they hired, at the lowest ranking of all the staff.”

Acquisition/relocation work transitioned to developing affordable housing in largely African-American northeast Omaha neighborhoods. All of it was an education.

“There’s lots of things I was exposed to — a myriad of housing programs. I was active working to get housing built for first-time home buyers all the way down to the homeless shelters. I just learned on the way.”

His professional interest in the homeless began in the mid-’80s, when laws emptied mental health institutions, dumping countless people into the streets without a system to assist them or the communities they inhabited. He became Omaha’s point person for developing plans and capturing funds to deal with homelessness. He assembled the land the Siena/Francis, the Open Door Mission and the Campus of Hope occupy today. He secured a building and funds for the Stephen Center.

“Omaha City Planning became a leader in the nation,” he said. “I developed almost every homeless strategic plan since the very first one starting in 1987. And so I just got really interested in it. I got really good at bringing in money. I brought in like tens of millions of dollars worth of (community block) grants. In about 1995 some homeless agencies came and asked me to take the leadership in trying to create community partnerships with all the programs. Up until then it was all turf wars — fighting over the money and philosophical differences on strategy. It was terrible.”

The resulting Metro Area Continuum of Care for the Homeless, a collaborative network of 100 homeless providers that coordinates and maximizes resources to prevent and eliminate homelessness, has been recognized nationally.

“It was all just creative juices flowing, without any knowledge of really how to do it. Just learn as you go and do it with openness and honesty,” Saklar said of the process that launched MACCH in ‘96. “It just evolved, as everything does. I got to meet the directors of probably a hundred programs or more, becoming their friend and colleague and guiding them — they sought my advice and I sought theirs. We were just finding ways to do this. Programs flourished. Collaborative efforts formed.

“It’s become so good we’ve became a model for other communities. I find myself in Washington, D.C. or Charlotte (N.C.) at seminars showing them our strategy — this is how we did it. I get calls from all over the country for advice.”

Overcoming old turf battles in Omaha, he said, “involved bringing all the agencies and programs together. We tried to create some values within this system, to get the agencies to recognize they’re all just a piece of the puzzle and they have to respect each other’s philosophies on how to deal with homeless people. I could use the money as the carrot or as the stick of no funding if you don’t hop on board and get on this program. I did that quite effectively I believe. I made people that wouldn’t even talk to each other become partners, and jointly funded them.”

While the homeless problem in big cities overwhelmed those communities, Omaha’s situation was more manageable. Still, many service gaps existed. Saklar’s seen much improvement. “Omaha’s made huge strides,” he said. “Omaha’s been very, very good in dealing with the homeless.” He’s one reason why. The plaques on his office wall honoring his service attest to it. In 2001 MACCH was singled out among hundreds of programs nationwide by Innovations in American Government. “It said Omaha was doing the right thing and on its way,” he said of the award.

Omaha city planner James Thele, a colleague of Saklar’s, said “what makes Mike effective is he’s a very caring person. He’s also a very practical person. He understands budgets and money. He understands that things take time. He’s also adept at building concensus to move forward with new projects.” Thele said Saklar “has the ability to create a vision of how to address homelessness from a continuum standpoint based on the needs of the individual.”

Saklar was drawn to the work of Siena/Francis before ever working there. The shelter was begun by two nuns in ‘75. It was on Cuming Street then. From the start he liked that it accepted whomever came to its doors. No discrimination. Saklar’s own life is all about embracing diversity and making multiculturalism a way of life.

“The thing about Siena/Francis House was it had unconditional acceptance,” said Saklar. “It’s the only program that’s not a religion, that’s not a church itself or that doesn’t have restrictions. The other shelters at that time wouldn’t let you in if you had even alcohol on your breath. And so for the active addict, the active alcoholic, the Siena/Francis House was the only place they could stay.”

“So there’s this huge unattended need,” he said of active users unmet at other agencies. “When I was a city official,” he said, “there’d be huge arguments almost always against Siena/Francis House — that they were just enabling this lifestyle.”

The way Saklar and Siena/Francis staff see it, however, an addict can’t get sober until basic human needs for food, clothing, shelter and security are met. Then the process of recovery can begin. Siena/Francis operates the state’s largest residential chemical addiction program in its Miracles Recovery Treatment Center. He said his agency serves the vast majority of this area’s chronic homeless.

Everything about Siena/Francis appealed to him and so when the opportunity to head it up came he accepted. “This place is a hidden jewel and I knew that when I was at city hall,” he said. “I loved city hall, l loved my colleagues, what I was doing. I was at age 55 and I could retire but I thought, I would love to do something else, I could have another career. This job opened up and I took it.”

Administrative duties aside, Saklar goes out of his way to engage homeless “guests.” Some wind up staffers like James Hayes.

“I’ve found that not only does he handle the very important decisions and planning that goes into keeping the Siena Francis House above water but also he is always concerned with each individual homeless person he comes in contact with,” said Hayes. “And, believe me, there are many of our guests he knows personally and has helped in a number of ways.”

Women’s shelter guest manager Patricia Cunningham was once a resident there. “Mike was and is a very big part of my recovery,” she said. “He showed me how honesty and integrity could and did change my life.” Saklar leads a large weekly AA meeting on campus, where he’s warmly greeted by staff and guests. “I like being a mentor,” said Saklar. “That’s one of the best things I have going here. I’m able to mentor people who are very dysfunctional, have lots of issues and problems, and maybe offer some advice. Every day I talk to people.”

Spend any time with Saklar making the rounds and you’ll witness this. Usually he greets guests with, “How we doing?” One March morning he came across a client in the treatment program and stopped to speak with him.

“Are you doing good?” asked Saklar. “Yeah, I just got back from Metro,” the man reported. “You going to college?” Saklar inquired. “Yeah,” the man said, “I just have to follow those same (12) steps here…” “Right, exactly, good,” Saklar said. “OK, well, just keep moving forward — you’re just doing a remarkable job here. I’m glad to have you as a friend.” “I’m glad to be your friend,” the man replied.

Later, Saklar told a visitor, “I’m so glad to see this guy succeeding in the program. You wouldn’t even have recognized him a few months ago — he was a hardcore street person.” It’s miracles like these and the sobriety anniversaries and treatment center graduations celebrated there that keep Saklar motivated. “It just shows that treament, especially in this facility, works. It works very well and we can all accomplish the goals if we just put our minds to it,” he said.

That same March day Saklar got a report from Miracles program director Bill Keck that three ex-homeless addicts are still making it on the outside.

“They live in the Gold Manor Apartments up by Immanuel Hospital — they were all hardcore street people and they all graduated (from treatment) about the same time and they’re all doing well. All employed. Haven’t abused or used drugs or alcohol for a number of years,” said Saklar, “and I’m talking about some long-term addicts that if you saw them on the street and you saw them today you wouldn’t even think they’re the same person. Those are the good things.

“My greatest pleasure is when I run into a formerly homeless person who is housed, employed, reunited with family and, basically, doing very well. Or them sending me pictures of their children that were born here, showing me they’re doing OK. I’ve had a lot of parents hug me and tell me I saved their son’s life. This whole issue of homelessness — it is often a matter of life or death.”

Positive feedback is vital in an arena that has more casualties than victories.

“Otherwise, you do get totally burned out. You still do to some degree,” he said. “The discouraging times come when homeless guests with whom I am working give up or leave, or something or someone interferes with progress. This happens a lot. Maybe someone who was dealing with an addiction was doing real well and then a brother comes and messes up his life. Things like that.

“The heartbreaking situations come in many forms. Obviously, a lot of homeless people whom I befriended have died — in the neighborhood of 100 in the seven years I’ve been at Siena/Francis House. I watched a lot of them waste away due to their alcoholism or cancer or other illness. We always hold memorial services for the homeless who die. I didn’t know when I took this job I would be doing that.”

Saklar is someone the homeless go to when they lose a loved one.

“Not too long ago I had to write a eulogy for a father whose two young sons and ex-wife had been murdered. He didn’t know what to say and came to me for help. I knew the children and mother had been homeless at times. I sat in the back of the funeral home and watched. He did a very good job under trying circumstances.”

Then there are the unsettling reminders of how homelessness can touch people who look just like us. Call these there-but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-I moments.

“I had two recent experiences that were very depressing to me,” said Saklar. “First, my 16-month-old granddaughter was visiting. I spent a Sunday bouncing her on my lap, looking into her big blue eyes. Then, when I arrived at work the next day I immediately ran into a 16-month-old girl whose mother had just checked into the Siena House. She had big, beautiful, blue eyes. She was unkempt, her clothes dirty and torn. I held her and tried to be happy but it tore me up inside.

“The same thing happened with my other granddaughter, who’s 11. We baby-sit every Wednesday. One Thursday morning I arrived at work to be introduced to an 11-year-old homeless girl and her mother. That bothered the heck out of me.”

Stereotypes abound about the homeless. We’re taught to avert our eyes from THEM or to avoid THEM because they’re unclean, dangerous, crazy derelicts. The truth is, something’s happened to bring them to this point. Every single one has a story of how they got there. Saklar said the chronic homeless account for most of Omaha’s down-and-outs. Others are pushed into desperate straits by a job loss, an illness, an addiction, an abusive relationship, before getting back on their feet.

“Most homeless do have an addiction or a mental illness, or both. Most have criminal histories. Most are not job-ready or housing-ready,” said Saklar. “Most have had disasterous lives since childhood. Too many are illiterate. Never got beyond fifth grade. It’s very unbelievable the number of people who never learned to read and write. Beyond that, they are all very unique individuals.”

Pass through downtown and you’ll glimpse some of these vagabonds and nomads. Some lug their possessions in bags, others in grocery carts. Weather allowing, men mill about the Siena/Francis compound. Most stay inside, protected from the elements, under the supervision of professionals who care. Were it not for safe environments like this the homeless would resort to dumpster diving, begging, stealing, loitering on corners, in alleys, in stairwells, in parks, living in shanties. Street life is no life at all. It’s a survival-of-the-fittest grind.

The current economic crisis with its high unemployment is spiking pantry and homeless shelter usage. Human service directors like Saklar worry the slump will impact the donations they depend on.

“Our budget this year is going to be $1.8 million but that’s counting a lot of grants for things, like a $200,000 (matching) grant from Kiewit for the new day services program. When I first came here the previous year’s budget was $600,000. I’d never run a business in my life. This is a business — you’ve got cash flow, you’ve got bills, you’ve got salaries, you’ve got employment laws just like every place you work.”

What he found when he arrived, he said, were “a lot of cash flow problems. I’m here a little over a year and I borrowed $60,000 to keep the doors open. We had a little line of credit and I used it.” He acknowledges that first year or two “was a challenge personally trying to learn all this and figure out what I got myself into.”

With time, it’s all worked out. “We turned all that around nicely as far as the fundraising,” he said. Siena holds an annual walk/run that raises money for the agency’s programs. And where before Siena rarely sent out solicitation letters asking for help it sends out several a year now. “I changed that. I had to — we would never have survived. There’s a lot of competition out there.”

Even though the agency’s financially stable today he said it never fails that “by October we’re always in the red.” He said, “Last year we were like $300,000 in the hole but amazingly in this business 50 percent of all our donations come in that fourth quarter. Every year it happens. You have to have faith.”

“In 2008, he said, “probably 83 to 85 percent of all our funding support just came from people in the community responding to our fundraising letters, probably six percent came from government” and the rest from foundations, corporations, etc.

Siena/Francis does much with little. Last year it provided 126,000 nights of shelter and 330,000 meals. “We probably average 350 (guests) a night,” said Saklar. “In addition to the mental health and addictions treatment one of the major efforts we have is the employment training program. We’ve got about 105 men and women in employment training. They help us run the programs and operate the facilities. We only have 26 salaried employees — everybody else is in employment training. It enables us to operate 24 hours-a-day, seven days-a-week.”

Saklar said the needs are great and more services required. He pulled out blueprints to reveal the expanded campus and services he has in mind. “This is going to be the centerpiece,” he said, indicating a rendering of a bright, airy building. “This is a human resource center or empowerment center — everybody has a different name for it — but it’s going to be a multipurpose facility with a healthcare center, strictly for the homeless, a dental clinic, respite care. It will provide every service a homeless person would need right out of this facility.”

This master collaborator envisions a one-stop campus where every appropriate service provider will have a presence. “One agency can’t do everything. I want Salvation Army involved, Heartland Family Services, all the mental health programs, Douglas County, Social Security, everybody. They can just do it right here.” Currently, homeless often must shuttle to off-site provider offices around town.

His vision doesn’t end there. “We’re going to build permanant supportive housing units,” he said, giving qualifying homeless a place to call their own. What would it mean to a homeless individual to have his/her own home? “When I walk over to our men’s shelter at night I see people sandwiched on the mats we spread out all over the floor. These people lying around, their self-esteem is so low — they think this is all they deserve. Then I think of the pride of knowing you have your own little apartment. What a huge lift up it’d be for these people.”

The plans also include “an employment-based center, where guests will do day labor. Perhaps an on-site manufacturer will put homeless people to work.

The price tag for the proposed 21-acre social service campus: $36 million. That includes an estimated $10 million in on-site improvements already completed.

He feels urgency to get it done but is pragmatic enough to be patient. “It needs to happen today,” he said. “This has been on the books for a long time. I think this is going to become a very worthwhile campus. It’s all part of the big picture.” Realistically, he thinks the campus could be completed in four years. He’s looking at funding avenues to realize the dream.

One nagging worry is potential opposition to a homeless campus in trendy NoDo, especially once the ballpark’s built. NoDo’s once hard streets are undergoing urban renewal, as warehouses, junk yards, manufacturing plants, bars and flop houses give way to gentrified new digs by Creighton University, the City and commercial developers. Fancy brick and mortar facades don’t change the fact homelessness exists. It’s a reality not going away anytime soon. Turning a blind eye won’t solve it. Moving shelters elsewhere only isolates the homeless from helping agencies.

Saklar’s advocated to keep services downtown, where, historically, the homeless congregate. “Somebody might want to come and take this place out. I know it could happen, and so I’m doing everything I can to solidify this agency-this campus,” he said. He’s weighed in on the NoDo development plan and he’s active in the Jefferson Square Business Association, assuring stakeholders a homeless campus can be a good neighbor. The more entrenched his homeless oasis, he figures, “the more impractical, more expensive” it is to remove.

“But you always have that danger,” he said. “So I’ve taken steps to ensure this is the appropriate place. One of those steps is working with Mayor (Mike) Fahey. He sees value in what we’re trying to do here. He’s been supportive from day one.”

City hall and Saklar work well together. He has strong allies there. It’s how the new day shelter Siena/Francis runs got built. Lameduck Fahey sings Saklar’s praises. “Mike has served Omaha’s homeless population with great distinction,” he said. “Under Mike’s leadership, the Siena/Francis House and the City of Omaha have developed an outstanding partnership through the establishment of a permanent homeless day shelter. Mike has gone the extra mile to help those in need.”

Is Saklar concerned what stance the next mayor may take? “No, because I think I’ve got relationships with everybody that’s running,” he said. “I think we’ll be fine.” He noted that the designs call for “a beautiful campus with green boundaries, landscaping, elevations that isolate it without having to erect fences.”

Once hired, Saklar gave himself 10 years on the job. Seven years in, he’s intent on reaching certain goals before he’s ready to call it quits. It may be three years, it may be more, “nothing’s set in stone.”

“Siena/Francis House needs to concentrate on getting better. We’ll get everything in place and then this agency needs to prove it can effectively deal with homelessness. I want to complete the vision I have,” he said. “I want everything operating at full capacity, doing what it’s supposed to be doing.” Then, and only then, he said, might he feel comfortable to “slowly maybe slip away…”

Related Articles

- How the Homeless Services Sector Fails the Short-Term Homeless (homelessness.change.org)

- Downtown L.A. homeless shelter to begin charging for some beds (latimesblogs.latimes.com)

- City To Create Name Registry For Homeless (chicagoist.com)

- San Diego Will Help the Homeless, Whether They Like it or Not (homelessness.change.org)

A force of nature named Evie: Still a maverick social justice advocate at 100

Spend even a little while with Evie Zysman, as I did, and she will leave an impression on you with her intelligence and passion and commitment. I wrote this story for the New Horizons, a publication of the Eastern Nebraska Office on Aging. We profile dynamic seniors in its pages, and if there’s ever been anyone to overturn outmoded ideas of older individuals being out of touch or all used up, Evie is the one. She is more vital than most people half or a third her age. I believe you will be as struck by her and her story as I was, and as I continue to be.

A force of nature named Evie:

Still a maverick social justice advocate at 100

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

When 100-year-old maverick social activist, children’s advocate and force of nature Evelyn “Evie” Adler Zysman recalls her early years as a social worker back East, she remembers, “as if it were yesterday,” coming upon a foster care nightmare.

It was the 1930s, and the former Evie Adler was pursuing her graduate degree from Columbia University’s New York School of Social Work. As part of her training, Zysman, a Jew, handled Jewish family cases.

“I went to a very nice little home in Queens,” she said from her art-filled Dundee neighborhood residence. “A woman came to the door with a 6-year-old boy. She said, ‘Would you like to see his room?’ and I said, ‘I’d love to.’ We go in, and it’s a nice little room with no bed. Then the woman excuses herself for a minute, and the kid says to me, ‘Would you like to see where I sleep?’ I said, ‘Sure, honey.’ He took me to the head of the basement stairs. There was no light. We walked down in the dark and over in a corner was an old cot. He said, ‘This is where I sleep.’ Then he held out his hand and says, ‘A bee could sting me, and I wouldn’t cry.’

“I knew right then no child should be born into a living hell. We got him out of that house very fast and got her off the list of foster mothers. That was one of the experiences that said to me: Kids are important, their lives are important, they need our help.”

Evie Zysman

Imbued with an undying zeal to make a difference in people’s lives, especially children’s lives, Evie threw herself into her work. Even now, at an age when most of her contemporaries are dead or retired, she remains committed to doing good works and supporting good causes.

Consistent with her belief that children need protection, she spent much of her first 50 years as a licensed social worker, making the rounds among welfare, foster care and single-parent families. True to her conviction that all laborers deserve a decent wage and safe work spaces, she fought for workers’ rights as an organized union leader. Acting on her belief in early childhood education, she helped start a project that opened day care centers in low income areas long before Head Start got off the ground; and she co-founded, with her late husband, Jack Zysman, Playtime Equipment Co., which sold quality early childhood education supplies.

Evie developed her keen social consciousness during one of the greatest eras of need in this country — the Great Depression. The youngest of eight children born to Jacob and Lizzie Adler, she grew up in a caring family that encouraged her to heed her own mind and go her own way but to always have an open heart.

“Mama raised seven daughters as different as night and day and as close as you could possibly get,” she said. “Mama said to us, ‘Each of you is pretty good, but together you are much better. Remember girls: Shoulder to shoulder.’ That was our slogan. And then, to each one of us she would say, ‘Don’t look to your sister — be yourself.’ It was taken for granted each one of us would be ourselves and do something. We loved each other and accepted the fact each one of us had our own lives to live. That was great.”

Even though her European immigrant parents had limited formal education, they encouraged their offspring to appreciate the finer things, including music and reading.

“Papa was a scholar in the Talmud and the Torah. People would come and consult him. My mother couldn’t read or write English but she had a profound respect for education. She would put us girls on the streetcar to go to the library. How can you live without books? Our home was filled with music, too. My sister Bessie played the piano and played it very well. My sister Marie played the violin, something she did professionally at the Loyal Hotel. My sister Mamie sang. We would always be having these concerts in our house and my father would run around opening the windows so the neighbors could also enjoy.”

Then there was the example set by her parents. Jacob brought home crates filled with produce from the wholesale fruit and vegetable stand he ran in the Old Market and often shared the bounty with neighbors. One wintry day Lizzie was about to fetch Evie’s older siblings from school, lest they be lost in a mounting snowstorm, when, according to Evie, the family’s black maid intervened, saying, “You’re not going — you’re staying right here. I’ll bring the children.’ Mama said, ‘You can go, but my coat around you,’ and draped her coat over her. You see, we cared about things. We grew up in a home in which it was taken for granted you had a responsibility for the world around you. There was no question about it.”

Along with the avowed obligation she felt to make the world a better place, came a profound sense of citizenship. She proudly recalls the first time she was old enough to exercise her voting right.

“I will always remember walking into that booth and writing on the ballot and feeling like I am making a difference. If only kids today could have that feeling when it comes to voting,” said Evie, a lifelong Democrat who was an ardent supporter of FDR and his New Deal. When it comes to politics, she’s more than a bystander — she actively campaigns for candidates. She’ll be happy with either Obama or Clinton in the White House.

When it came time to choose a career path, young Evie simply assumed it would be in an arena helping people.

“I was supposed to, somehow,” is how she sums it up all these years later. “I believed, and I still believe, that to take responsibility as a citizen, you must give. You must be active.”

For her, it was inconceivable one would not be socially or politically active in an era filled with defining human events — from millions losing their savings and jobs in the wake of the stock market crash to World War I veterans marching in the streets for relief to unions agitating for workers’ rights to a resurgence of Ku Klux Klan terror to America’s growing isolationism to the stirrings of Fascism at home and abroad. All of this, she said, “got me interested in politics and in keeping my eyes open to what was going on around me. It was a very telling time.”

Unless you were there, it’s difficult to grasp just how devastating the Depression was to countless people’s pocketbooks and psyches.

“It’s so hard for you younger generations to understand” she told a young visitor to her house. “You have never lived in a time of need in this country.” Unfortunately, she added, the disparity “between rich and poor” in America only seems to widen as the years go by.

With her feisty I-want-to-change-the-world spirit, Evie, an Omaha Central High School graduate, would not be deterred from furthering her formal education and, despite meager finances, became the first member of her family to attend college. Because her family could not afford to send her there, she found other means of support via scholarships from the League of Women Voters and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where the Phi Betta Kappa earned her bachelor’s degree.

“I knew that for me to go to college, I had to find a way to go. I had to find work, I had to find scholarships. Nothing came easy economically.”

To help pay her own way, she held a job in the stocking department at Gold’s Department store in downtown Lincoln. An incident she overhead there brought into sharp relief for her the classism that divides America. “

One day, a woman with a little poodle under her arm came over to a water fountain in the back of the store and let her dog drink from it. Well, the floorwalker came running over and said, ‘Madam, that fountain is for people,’ and the woman said, ‘I’m so sorry, I thought it was for the employees.’ That’s an absolutely true story and it tells you where my politics come from and why I care about the world around me and I want to do something about it.”

Her undergraduate studies focused on economics. “I was concerned I should understand how to make a living,” she said. “That was important.” Her understanding of hard times was not just of the at-arms-length, ivory-tower variety. She got a taste of what it was like to struggle when, while still an undergrad, she was befriended by the Lincoln YWCA’s then-director who arranged for Evie to participate in internships that offered a glimpse into how “the other half lived.” Evie worked in blue collar jobs marked by hot, dark, close work spaces.

“She thought it was important for me to have these kind of experiences and so she got me to go do these projects. One, when I was a sophomore, took me in the summer to Chicago, where I worked as a folder in a laundry and lived in a working girls’ rooming house. There was no air conditioning in that factory. And then, between my junior and senior years, I went to New York City, where I worked in a garment factory. I was supposed to be the ‘do-it’ girl — get somebody coffee if they wanted it or give them thread if they needed it, and so forth.

“The workers in our factory were making some rich woman a beautiful dress. They asked me to get a certain thread. And being already socially conscious, I thought, ‘I’ll fix her,’ and I gave them the wrong thread,” a laughing Evie recalled, still delighted at the thought of tweaking the nose of that unknown social maven.

Upon graduating with honors from UNL she set her sights on a master’s degree. First, however, she confronted misogyny and bigotry in the figure of the economics department chairman.

“He said to me, ‘Well, Evelyn, you’re entitled to a graduate fellowship at Berkeley but, you know, you’re a woman and you are a Jew, so what would you possibly do with your graduate degree when you complete it?’ Well, today, you’d sue him if he ever dared say that.”

Instead of letting discrimination stop her, the indomitable Evie carried-on and searched for a fellowship from another source. She found it, too, from the Jewish School of Social Work in New York.

“It was a lot of money, so I took it,” she said. “I had my ethic courses with the Jewish School and my technical courses with Columbia,” where she completed her master’s in 1932.

As her thesis subject she chose the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, one of whose New York factories she worked in. There was a strike on at the time and she interviewed scores of unemployed union members who told her just how difficult it was feeding a family on the dole and how agonizing it was waking-up each morning only to wonder — How are we going to get by? and When am I ever going to work again?

As a social worker she saw many disturbing things — from bad working conditions to child endangerment cases to families struggling to survive on scarce resources. She witnessed enough misery, she said, “that I became free choice long before there was such a phrase.”

Her passion for the job was great but as she became “deeply involved” in the United Social Service Employees Union, she put her first career aside to assume the presidency of the New York chapter.

“I could do even more for people, like getting them decent wages, than I could in social work.” Among the union’s accomplishments during her tenure as president, she said, was helping “guarantee social workers were qualified and paid fairly. You had to pay enough in order to get qualified people. We felt if you, as social workers, were going to make decisions impacting people’s lives, you better be qualified to do it.”

Feeling she’d done all she could as union head, she returned to the social work field. While working for a Jewish Federation agency in New York, she was given the task of interviewing Jewish refugees who had escaped growing Nazi persecution in Germany and neighboring countries. Her job was to place new arrivals with the appropriate state social service departments that could best meet their needs. Her conversations with emigres revealed a sense of relief for having escaped but an even greater worry for their loved ones back home.

“They expressed deep, deep concern and deep, deep sadness and fear about what was going on over there,” she said, “and anxiety about what would happen to their family members that remained over there. They worried too about themselves — about how they would make it here in this country.”

A desire to help others was not the only passion stoked in Evie during those ”wonderful” New York years. She met her future husband there while still a grad student. Dashing Jack Zysman, an athletic New York native, had recently completed his master’s in American history from New York University. One day, Evie went to some office to retrieve data she needed on the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, when she met Jack, who was doing research in the very same office. Sharing similar interests and backgrounds, the two struck up a dialogue and before long they were chums.

The only hitch was that Evie was engaged to “a nice Jewish boy in Omaha.” During a break from her studies, she returned home to sort things out. One day, she was playing tennis at Miller Park when she looked across the green and there stood Jack. “He drove from New York to tell me I was definitely coming back and that I was not to marry anybody but him.” Swept off her feet, she broke off her engagement and promised Jack she would be his.

After their marriage, the couple worked and resided in New York, where she pursued union and social work activities and he taught and coached at a high school. Their only child, John, today a political science professor at Cal-Berkeley, was born in New York. Evie has two grandchildren by John and his wife.

Along the way, Evie became a New Yorker at heart. “I loved that city,” she said. Her small family “lived all over the place,” including the Village, Chelsea and Harlem. As painful as it was to leave, the Zysmans decided Omaha was better suited for raising John and, so, the family moved here shortly after World War II.

Soon the couple began Playtime Equipment, their early childhood education supply company. The genesis for Playtime grew out of Evie’s own curiosity and concern about the educational value of play materials she found at the day care John attended. When the day care’s staff asked her to “help us know what to do,” she rolled up her sleeves and went to work.

She called on experts in New York, including children’s authors, day care managers and educators. When she sought a play equipment manufacturer’s advice, she got a surprise when the rep said, “Why don’t you start a company and supply kids with the right stuff?” It was not what she planned, but she and Jack ran with the idea, forming and operating Playtime right from their home. The company distributed everything from books, games and puzzles to blocks and tinker toys to arts and crafts to playground apparatus to teaching aids. The Zysmans’ main customers were schools and day cares, but parents also sought them out.

“I helped raise half the kids in Omaha,” Evie said.

The Zysman residence became a magnet for state and public education officials, who came to rely on Evie as an early childhood education proponent and catalyst. She began forming coalitions among social service, education and legislative leaders to address the early childhood education gap. A major initiative in that effort was Project AID, a program she helped organize that set-up preschools at black churches in Omaha to boost impoverished children’s development. She said the success of the project helped convince state legislators to make kindergarten a legal requirement and played a role in Nebraska being selected as one of the first states to receive the federal government’s Head Start program.

Gay McTate, an Omaha social worker and close friend of Zysman’s, said, “Evie’s genius lay in her willingness to do something about problems and her capacity to bring together and inspire people who could make a difference.”

Evie immersed herself in many more efforts to improve the lives of children, including helping form the Council for Children’s Services and the Coordinated Childcare Project, clearinghouses geared to meeting at-risk children’s needs.

The welfare of children remains such a passion of hers that she still gets mad when she thinks about the “miserable salaries” early childhood educators make and how state budget cuts adversely impact kids’ programs.

“Everybody agrees today the future of our country depends on educating our children. So, what do we do about it? We cut the budgets. Don’t get me started…” she said, visibly upset at the idea.

Besides children, she has worked with such organizations as the United Way, the Urban League, the League of Women Voters, the Jewish Council of Women, Hadassah and the local social action group Omaha Together One Community.

In her nearly century of living, she’s seen America make “lots of progress” in the area of social justice, but feels “we have a long way to go. I worry about the future of this country.”

Calling herself “a good secular Jew,” she eschews attending services and instead trusts her conscience to “tell me what’s right and wrong. I don’t see how you can call yourself a good Jew and not be a social activist.” Even today, she continues working for a better community by participating in Benchmark, a National Council of Jewish Women initiative to raise awareness and discussion about court appointments and by organizing a Temple Israel Synagogue Mitzvah (Hebrew, for good deed) that staffs library summer reading programs with volunteers.

Her good deeds have won her numerous awards, most recently the D.J.’s Hero Award from the Salvation Army and Temple Israel’s Tikkun Olam (Hebrew, for repairing the world) Social Justice Award.

She’s outlived Jack and her siblings, yet her days remain rich in love and life. “I play bridge. I get my New York Times every day. I have my books (she is a regular at the Sorenson Library branch). I’ve got friends. I have my son and daughter-in-law. I have my grandchild. What else do you need? It’s been a very full life.”

As she nears a century of living Evie knows the fight for social justice is a never-ending struggle she can still shine a light on.

“How would I define social justice?” she said at an Omaha event honoring her. “You know, it’s silly to try to put a name to realizing that everybody should have the same rights as you. There is no name for it. It’s just being human…it’s being Jewish. There’s no name for it. Give a name to my mother who couldn’t read or write but thought that you should do for each other.”

Related Articles

- Alberta foster care system under scrutiny (calgaryherald.com)

- Leading article: The care system needs a drastic overhaul (independent.co.uk)

- Feds share blame for child welfare system ‘chaos’ (cbc.ca)

John Sorensen and his Abbott Sisters Project: One man’s magnificent obsession shines light on extraordinary Nebraska women

The following story was published in the June 2009 New Horizons newspaper. The layout and photographs and article all worked harmoniously together to create a great spread. I post the story here because I think it makes a good read and it introduces you to an interesting personality in the figure of Sorensen and to the remarkable accomplishments of two women I certainly never heard of before working on this story. I think you’ll find, as I did, that Sorensen and the Abbotts make a fitting troika of unbridled passion.

NOTE: John has worked closely over the years with Ann Coyne from the University of Nebraska at Omaha‘s School of Social Work, which was recently renamed the Grace Abbott School of Social Work. Coyne’s a great champion of the work of the Abbott sisters, particularly Grace Abbott, and drew on Sorensen’s work to make the case to university officials to rededicate the school in honor of Grace Abbott. John is also nearing completion on a documentary film that ties together the legacy of the Abbotts and their concern for immigrant women, children, and families and a story quilt project he organized that involved Sudanese girls living in Grand Island telling the stories of their families’ homeland and their new home in America through quilting.

My new story about John Sorensen and his magnificent obsession with the Abbotts is now posted, and in it you can learn more about his now completed documentary, which is being screened this fall.

Grace Abbott

John Sorensen and his Abbott Sisters Project: One man’s magnificent obsession shines light on sxtraordinary Nebraska women

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Grace and Edith Abbott may be the most extraordinary Nebraskans you’ve never heard of. John Sorensen aims to change that.

Born and reared on Grand Island’s prairie outskirts in the last quarter of the 19th century, when Indians still roamed the land, the Abbott sisters graduated from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. After teaching in Grand Island they felt called to a secular ministry — the then emerging field of social work in Chicago. They earned advanced degrees at the University of Chicago, where they later taught.

No ivory tower dwellers, the sisters worked with Hull House founder Jane Addams at her famous social settlement. There, amid miserable, overcrowded tenement slums, they set a progressive course for the fair treatment of immigrants, women and children that still has traction today. The sisters’ trailblazing paths followed the lead of their abolitionist father, an early Nebraska politico, and Quaker mother, whose family worked the Underground Railroad. The parents were avid suffragists.

The sisters exerted wide influence: Grace as a federal administrator charged with children and family affairs; Edith as a university educator. They were outspoken advocates-muckrakers-reformers-advisers who helped to set rigorous protocols for social work and to craft public policies and laws protecting marginalized groups. Each attained many firsts for women. Both valued their Nebraska roots.