Archive

Father Ken Vavrina’s new book “Crossing Bridges” charts his life serving others

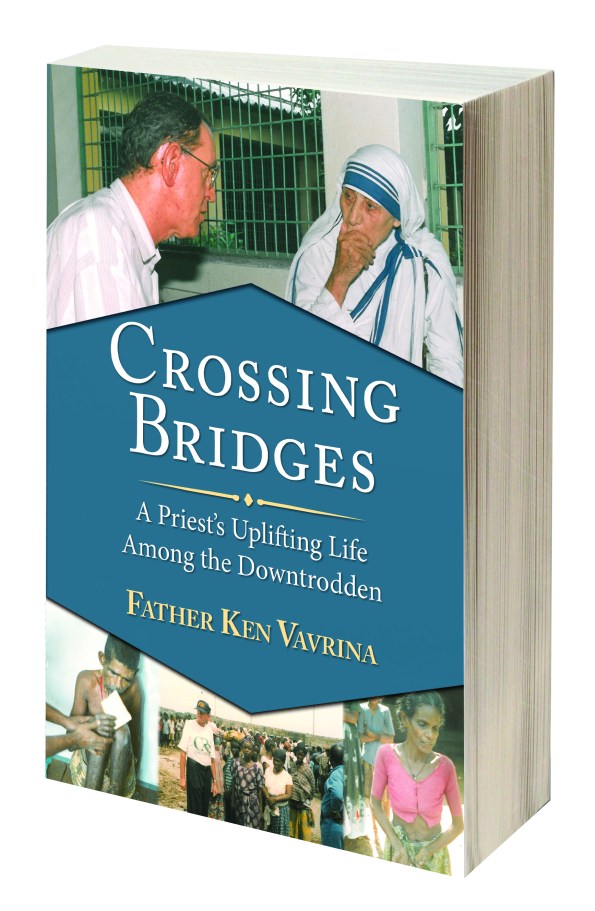

For a man whose vocation as a priest is a half-century long and counting, it may come as a surprise that Father Ken Vavrina had no notion of entering that life until, at age 18, a voice instructed him to attend seminary school. It was a classic calling from on high that he didn’t particularly want or appreciate. He had his life planned out, after all, and it didn’t include the priesthood. He resisted the very thought of it. He rationalized why it wasn’t right for him. He wished the admonition would go away. But it just wouldn’t. He couldn’t ignore it. He couldn’t shake it. Deep inside he knew the truth and rightness of it even though it seemed like a strange imposition. In the end, of course, he obeyed and followed the path ordained for him. His rich life serving others has seen him minister to Native Americans on reservations, African-Americans in Omaha’s inner city, occupying protestors at Wounded Knee, lepers in Yemen. the poor, hungry and homeless in Calcutta, India and war refugees in Liberia. He worked for Mother Teresa and for Catholic Relief Services. He’s been active in Omaha Together One Community. There have been many other stops as well, including Italy, Cuba, New York City and rural Nebraska. He has crossed many cultural and geographic bridges to engage people where they are at and to respond to their needs for food, water, medicine, shelter, education, counseling. Everywhere he’s gone he’s gained far more from those he served than he’s given them and as a result he’s grown personally and spiritually. He has attained great humility and gratitude. His simple life of service to others has much to teach us and that’s why he commissioned me to help him write the new book, Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden. It was a privilege to share his remarkable life and story in book form. Here is an article I’ve written about him and his many travels. It is the cover story in the November 2015 issue of the New Horizons. I hope, as he does, that this story as well as the book we did together that this story is drawn from inspires you to cross your own bridges into different cultures and experiences. Many blessings await.

The book is available at http://www.upliftingpublishing.com/ as well as on Amazon and BarnesandNoble.com and for Kindle. The Bookworm is exclusively carrying “Crossing Bridges” among local bookstores.

Father Ken with Mother Teresa

Father Ken Vavrina’s new book “Crossing Bridges” charts his life serving others

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the November 2015 issue of the New Horizons

NOTE:

My profile of Father Ken Vavrina contains excerpts and photos from the new book I did with him, Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden.

A Life of Service

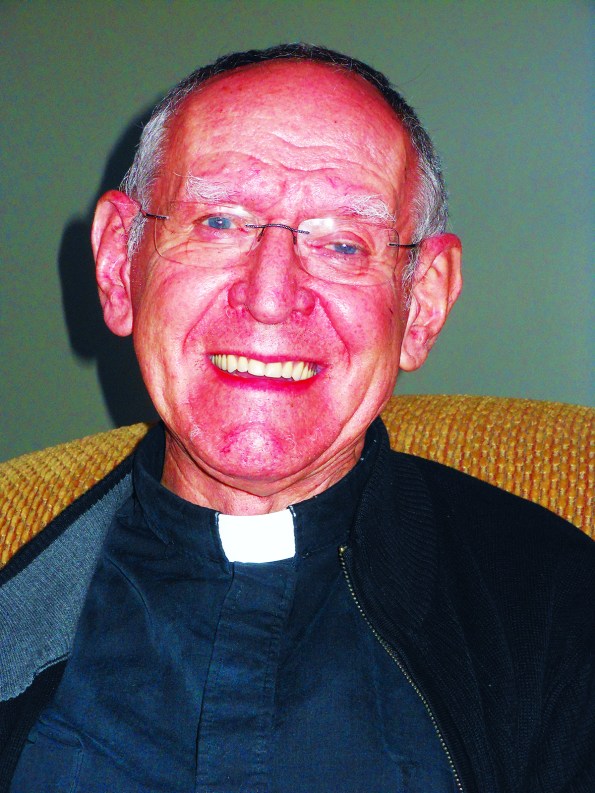

Retired Catholic priest Father Kenneth Vavrina, 80, has never made an enemy in his epic travels serving people and opposing injustice.

“I have never met a stranger. Everyone I meet is my friend,” declares Vavrina, who’s lived and worked in some of the world’s poorest places and most trying circumstances.

It’s no accident he ended up going abroad as a missionary because from childhood he burned with curiosity about what’s on the other side of things – hills, horizons, fences, bridges. His life’s been all about crossing bridges, both the literal and figurative kind. Thus, the title of his new book, Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden, his personal chronicle of repeatedly venturing across borders ministering to people. His willingness to go where people are in need, whether near or far, and no matter how unfamiliar or forbidding the location, has been his life’s recurring theme.

For most of his 50-plus years as a priest he’s helped underserved populations, some in outstate Neb., some in Omaha, and for a long time in developing nations overseas. Whether pastoring in a parish or doing missionary work in the field, he’s never looked back, only forward, led by his insistent conscience, open heart and boy-like sense of wanderlust. That conscience has put him at odds with his religious superiors in the Omaha Catholic Archdiocese on those occasions when he’s publicly disagreed with Church positions on social issues. His tendency to speak his mind and to criticize the Catholic hierarchy he’s sworn to obey has led to official reprimands and suspensions.

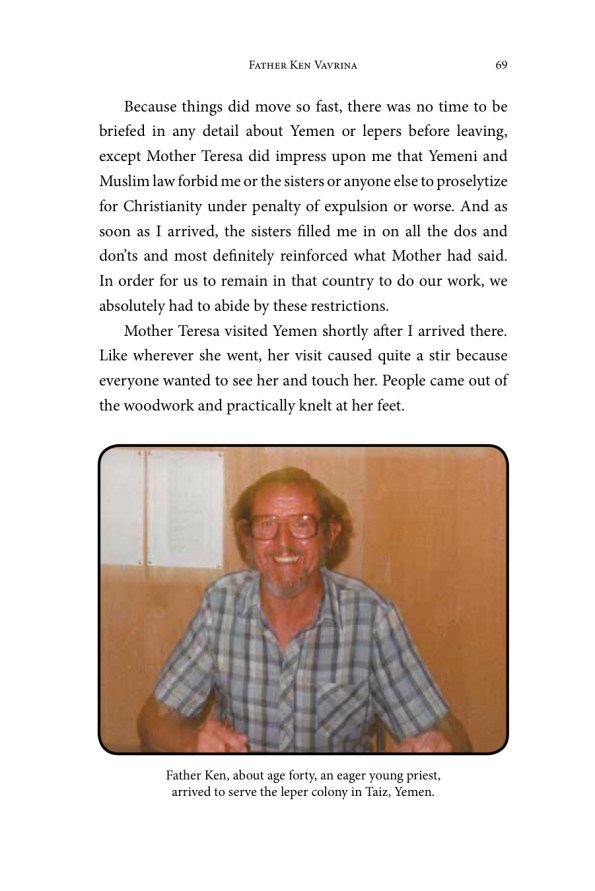

But no one questions his dedication to the priesthood. Always putting his faith in action, he shepherds people wherever he lays his head. He lived five years in a mud hut minus indoor plumbing and electricity tending to lepers in Yemen. He became well acquainted with the slums of Calcutta, India while working there. He spent nights in the African bush escorting supplies. He spent two nights in a trench under fire. The archdiocesan priest served Native Americans on reservations and African-Americans in Omaha’s poorest neighborhoods. He befriended members of the American Indian Movement, Black Panthers and various activists, organizers, elected officials and civic leaders.

His work abroad put him on intimate terms with Blessed Mother Teresa, now in line for sainthood. and made him a friend of convenience of deposed Liberia, Africa dictator Charles Taylor, now imprisoned for war crimes. As a Catholic Relief Services program director he served earthquake victims in Italy, the poorest of the poor in India, Bangladesh and Nepal and refugees of civil war in Liberia.

He found himself in some tight spots and compromising positions along the way. He ran supplies to embattled activists during the Siege at Wounded Knee. He was arrested and jailed in Yemen before being expelled from the country. He faced-off with trigger-happy rebels leading supply missions via truck, train and ship in Liberia and dealt with warlords who had no respect for human life.

If his book has a message it’s that anyone can make a difference, whether right at home or half way around the globe, if you’re intentional and humble enough to let go and let God.

“There is nothing remarkable about me…yet I have been blessed to lead a most fulfilling life…The nature of my work has taken me to some fascinating places around the world and introduced me to the full spectrum of humanity, good and bad.

“Stripping away the encumbrances of things and titles is truly liberating because then it is just you and the person beside you or in front of you. There is nothing more to hide behind. That is when two human hearts truly connect.”

Even though he’s retired and no longer puts himself in harm’s way, he remains quite active. He comforts and anoints the sick, he administers communion, he celebrates Mass and he volunteers at St. Benedict the Moor. Occasional bouts of the malaria he picked up overseas are reminders of his years abroad. So is the frozen shoulder he inherited after a botched surgery in Mexico. His shaved head is also an emblem from extended stays in hot climates, where to keep cool he took to buzz cuts he maintains to this day. Then there’s his simple, vegan diet that mirrors the way he ate in Third World nations.

This tough old goat recently survived a bout with cancer. A malignant tumor in his bladder was surgically removed and after recouping in the hospital he returned home. The cancer’s not reappeared but he has battled a postoperative bladder infection and gout. Ask him how he’s doing and he might volunteer, “I’m not getting around too well these days” but he usually leaves it at, “I’m OK.” He lives at the John Vianney independent living community for retired clergy and lay seniors. He’s more spry than many residents. It’s safe to say he’s visited places they’ve never ventured to.

Father Ken today

Roots

Born in Bruno and raised in Clarkson, Neb., both Czech communities in Neb.’s Bohemian Alps, Vavrina and his older brother Ron were raised by their public school teacher mother after their father died in an accident when they were small. The boys and their mother moved in with their paternal grandparents and an uncle, Joe, who owned a local farm implement business and car dealership. The uncle took the family on road trip vacations. Once, on the way back from Calif. by way of the American southwest, Vavrina engaged in an exchange with his mother that profoundly influenced him.

“I remember my mom telling me, “On the other side of that bridge is Mexico,” and right then and there I vowed, ‘One day I’m going to cross that bridge'”

“I never crossed that particular bridge but I did cross a lot of bridges to a lot of different lifestyles and countries and cultures and it was a great, great, great blessing. You learn so much in working with people who are different.”

One key lesson he learned is that despite our many differences, we’re all the same.

Even though he grew up around very little diversity, he was taught to accept all people, regardless of race or ethnicity. He feels that lesson helped him acclimate to foreign cultures and to living and working with people of color whose ways differed from his.

As a fatherless child of the Great Depression and with rationing on due to the Second World War, Vavrina knew something about hardship but it was mostly a good life. Growing up, he went hunting and fishing with his uncle, whose shop he worked in. He played organized basketball and baseball for an early mentor, coach Milo Blecha.

“All in all, I had a wonderful childhood in Clarkson,” he writes. “It was a simple life. The Church was dominant. There was a Catholic church and a Presbyterian church. Father Kubesh was the pastor at Saints Cyril and Methodius Catholic Church. When he was not saying Mass, Father Kubesh always had a cigar in his mouth. I served Mass as an altar boy. Little did I imagine that he would counsel me when I embarked on studying for the priesthood.”

All through high school Vavrina dated the same girl. His family wasn’t particularly religious and he never even entertained the possibility of the priesthood until he felt the calling at 18. Out of nowhere, he says, the thought, really more like an admonition, formed in his head.

“I was driving a pickup truck on a Saturday morning, about four miles east of Clarkson, when something happened that is still crystal clear to me. I distinctly heard a voice say, ‘Why don’t you go to the seminary?’ Just like that, out of the blue. I thought, This is crazy.“Was it God’s voice?

“Being a priest is a calling, and I guess maybe it was the call that I felt then and there. If you want to give it a name or try to explain it, then God called me to serve at that moment. He planted the seed of that idea in my head, and He placed the spark of that desire in my heart.”

The very idea threw Vavrina for a loop. After all, he had prospects. He expected to marry his sweetheart and to either go into the family business or study law at Creighton University. The priesthood didn’t jibe with any of that.

He says when he told Father Kubesh about what happened the priest’s first reaction was, “Huh?” For a long time Vavrina didn’t tell anyone else but when it became evident it wasn’t some passing fancy he let his friends and family know. No one, not even himself, could be sure yet how serious his conviction was, which is why he only pledged to give it one year at Conception Seminary College in northwest Missouri.

He told his uncle, I’ll give it a shot.” And so he did. One year turned into two, two years turned into three, and so on, and though his studies were demanding he found he enjoyed academics.

He finished up at St. Paul Seminary at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn. and was ordained in 1962.

Calling all cultures

His introduction to new cultures began with his very first assignment, as associate pastor for the Winnebago and Macy reservations in far northern Nebraska. Vavrina was struck by the people’s warmth and sincerity and by the disproportionate numbers living in poverty and afflicted with alcoholism. He disapproved of efforts by the Church to try and strip children of their Native American ways, even sending kids off to live with white families in the summer.

His next assignment brought him to Sacred Heart parish in predominantly black northeast Omaha. He arrived at the height of racial tension during the late 1960s civil rights struggle. He served on an inner city ministerial team that tried getting a handle on black issues. When riots erupted he was there on the street trying to calm a volatile situation. The more he learned about the inequalities facing that community, the more sympathetic he became to both the civil rights and Black Power movements, so much so, he says, people took to calling him “the blackest cat in the alley.”

He was an ally of Nebraska state Sen. Ernie Chambers, activist Charlie Washington and Omaha Star publisher Mildred Brown. He befriended Black Panthers David Rice and Ed Poindexter (Mondo we Langa), both convicted in the homemade bomb death of Omaha police officer Larry Minard. The two men have always maintained their innocence..

Vavrina welcomed changes ushered in by Vatican II to make the Church more accessible. He criticized what he saw as ultra-conservative and misguided stands on social issues. For example, he opposed official Catholic positions excluding divorced and gay Catholics and forbidding priests from marrying and barring women being ordained. He began a long tradition of writing letters to the editor to express his views. He’s never stopped advocating for these things.

He next served at north downtown Holy Family parish, where his good friend, kindred spirit and fellow “troublemaker” Jack McCaslin pastored. McCaslin spouted progressive views from the pulpit and became a peace activist protesting the military-industrial complex, which resulted in him being arrested many times. The two liberals were a good fit for Holy Family’s open-minded congregation.

Then, in 1973, Vavrina’s life intersected with history. Lorelei Decora, an enrolled member of the Winnebago tribe, Thunder Bird Clan, called to ask him to deliver medical supplies to her and fellow American Indian Movement activists at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. A group of Indians agitating for change occupied the town. Authorities surrounded them. The siege carried huge symbolic implications given its location was the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. Vavrina knew Decora when she was precocious child. Now she was a militant teen prevailing on him to ride into an armed standoff. He never hesitated. He and a friend Joe Yellow Thunder, an Oglala Sioux, rounded up supplies from doctors at St. Joseph Hospital. They drove to the siege and Father Ken talked his way inside past encamped U.S, marshals.

He met with AIM leader and cofounder Dennis Banks, whom he knew from before.

“Then I saw Lorelei and I looked her in the eye and asked, ‘What are you doing here?’ She said with great conviction, ‘I came to die.’ They really thought they would all be killed. They were fully committed…On his walkie-talkie Banks reached the authorities and told them, ‘Let this guy stay here. He’s objective. He’ll let you know what’s going on.’ The authorities went along…that’s how I came to spend two nights at the compound. We bivouacked in a ravine where the Indians had carved out trenches. We used straw and blankets over our coats, plus body heat, to keep warm at night. It was not much below freezing, and there was little snow on the ground, which made the camp bearable.“At night the shooting would commence…the tracers going overhead, the Indians huddled for cover, and several of the occupiers sick with cold and flu symptoms.

“Once back home, Joe and I attempted to make a second medicine supply run up there. We drove all the way to the rim but were turned back by the marshals because the violence had started up again and had actually escalated. When the siege finally ended that spring, there were many arrests and a whole slew of charges filed against the protesters.”

By the late-’70s Vavrina was serving a northeast Neb. parish and feeling restless. He’d given his all to combatting racism and advocating for equal rights but was disappointed more transformational change didn’t occur. He saw many priests abandon their vows and the Church regress into conservatism after the promise of Vatican II reforms. More than anything though, he felt too removed from the world of want. It bothered him he’d never really put himself on the line by giving up things for a greater good or surrendering his ego to a life of servitude.

“I felt I was out of the mainstream, away from the action. Plus, I knew the civil rights movement was…not going to reach what I thought it could achieve…So I decided I was going overseas. I wanted to be where I could do the greatest good. I always felt drawn to the missions…I just felt a need to experience voluntary poverty and to become nothing in a foreign land.“…an experience in Thailand changed the whole trajectory of my missions plan. I was walking the streets of Bangkok…on the edge of downtown…Then I made a wrong turn and suddenly found myself in the slums of Bangkok…everywhere I looked was human want and suffering at a scale I was unprepared for.

“I was shocked and appalled by the conditions people lived in. I realized there were slums all over the world and these people needed help. What was I doing about it? The experience really hit me in the face and marked an abrupt change in my thinking. I looked at my relative affluence and comfortable existence, and I suddenly saw the hypocrisy in my life. I resolved then and there, I was going to change, and I was going to move away from the privilege I enjoy, and I would work with the poor.”

A reinforcing influence was Mother Teresa, whom he admired for leaving behind her own privilege and possessions to tend to the poor and sick and dying. He resolved to offer himself in service to her work.

The nun, he writes, “was a great inspiration..” Nothing could shake his conviction to go follow a radically different path and calling.

His going away had nothing to do with escaping the past but everything to do with following a new course and passion. By that time he’s already worked 15 years in the archdiocese and “loved every minute of it.” He was finishing up a master’s degree in counseling at Creighton University. “Everything was good. No nagging doubts. But I just felt compelled to do more,” he writes.

He asked and received permission from the diocese to work overseas for one year and that single year, he describes, turned into 19 “incredible years helping the poorest of the poor.”

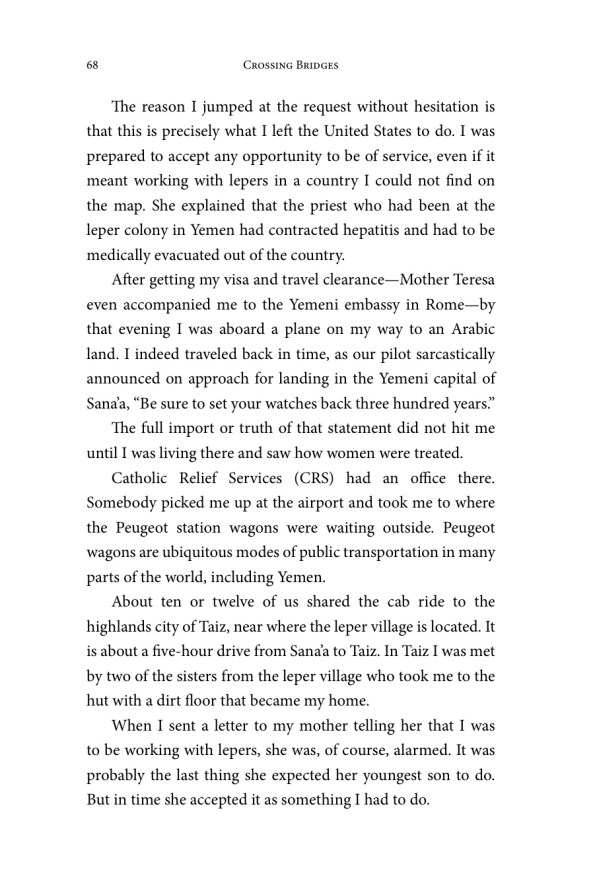

Yemen

He no sooner found Mother Teresa in Italy than she asked him to go to Yemen, an Arab country in southwest Asia, to work with residents of the leper village City of Light.

“I simply replied, ‘Sure,’” Vavrina notes in his book.

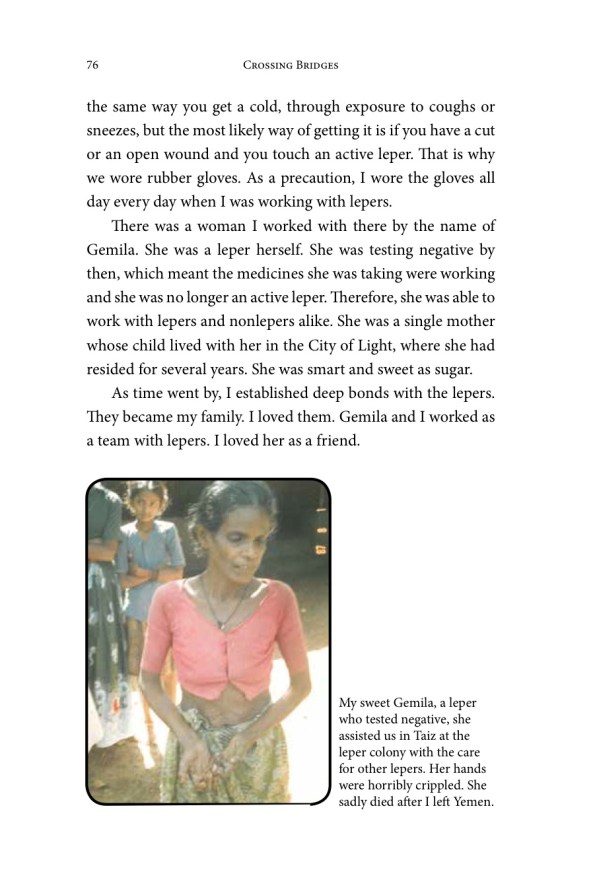

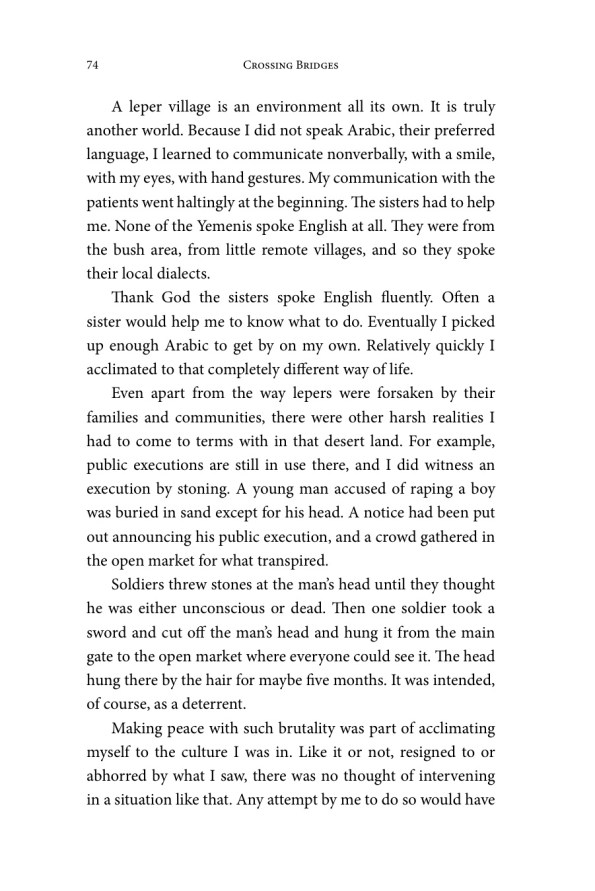

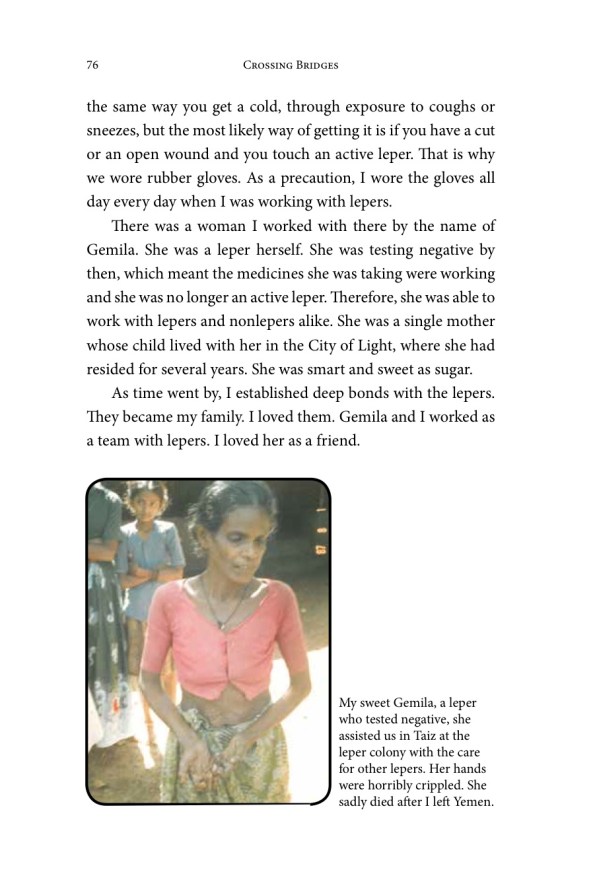

In Yemen he witnessed the fear and superstition that’s caused lepers to be treated as outcasts everywhere. In that community he worked alongside Missionaries of Charity as well as lepers.

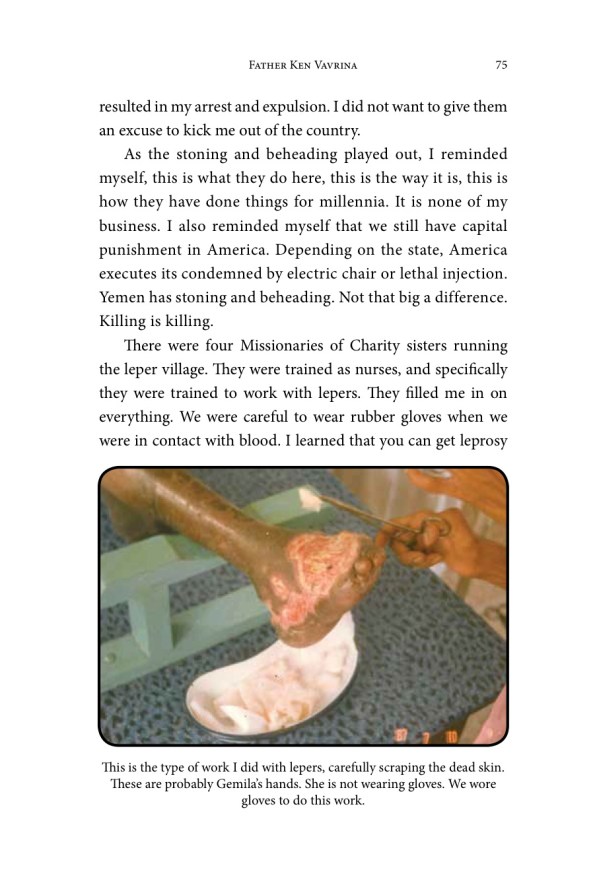

“My primary job was to scrape dead skin off patients using a knife or blade. It was done very crudely. Lepers, whether they are active or negative cases, have a problem of rotting skin. That putrid skin has to be removed for the affected area to heal and to prevent infection…I would then clean the skin.“I would also keep track of the lepers and where they were with their treatment and the medicines they needed.”

He embraced the spartan lifestyle and shopping at the local souk. He found time to hike up Mount Kilimanjaro. He also saw harsh things. An alleged rapist was stoned to death and the body displayed at the gate of the market. Girls were compelled to enter arranged marriages, forbidden from getting an education or job, and generally treated as property. Yemen is also where he contracted malaria and endured the first sweats and fevers that accompany it.

Yet, he says, Yemen was the place he found the most contentment. Then, without warning, his world turned upside down when he found himself the target of Yemeni authorities. They took him in for seemingly routine questioning that turned into several nights of pointed interrogation. He was released, but under house arrest, only to be detained again, this time in an overcrowded communal jail cell.

He was incarcerated nearly two weeks before the U.S. embassy arranged his release. No formal charges were brought against him. The police insinuated proselytizing, which he flatly denied, though he sensed they actually suspected him of spying. They couldn’t believe a healthy, middle-aged American male would choose to work with lepers.

His release was conditional on him immediately leaving the country. The expulsion hurt his soul.

“Being kicked out of the country, and for nothing mind you, other than blind suspicion, was not the way I imagined myself departing. I was disappointed. I truly believe that if I had been left to do my work in peace, I would still be there because I enjoyed every minute of working with the lepers. There is so much need in a place like Yemen, and while I could help only a few people, I did help them. It was taxing but fulfilling work.”

India

He traveled to Italy, where Catholic Relief Services hired him to manage a program rebuilding an earthquake ravaged area. Then CRS sent him to supervise aid programs in India. After nine months in Cochin he was transferred to Calcutta. Everywhere he set foot, hunger prevailed, with millions barely getting by on a bare subsistence level and life a daily survival test.

Besides supplying food, the programs taught farmers better agricultural practices and enlisted women in the micro loan program Grameen Bank. In all, he directed $38 million in aid annually.

The generous spirit of people to share what little they have with others impressed him. Seeing so many precariously straddle life and death, with many mothers and children not making it, opened his eyes. So did the sheer scale of want there.

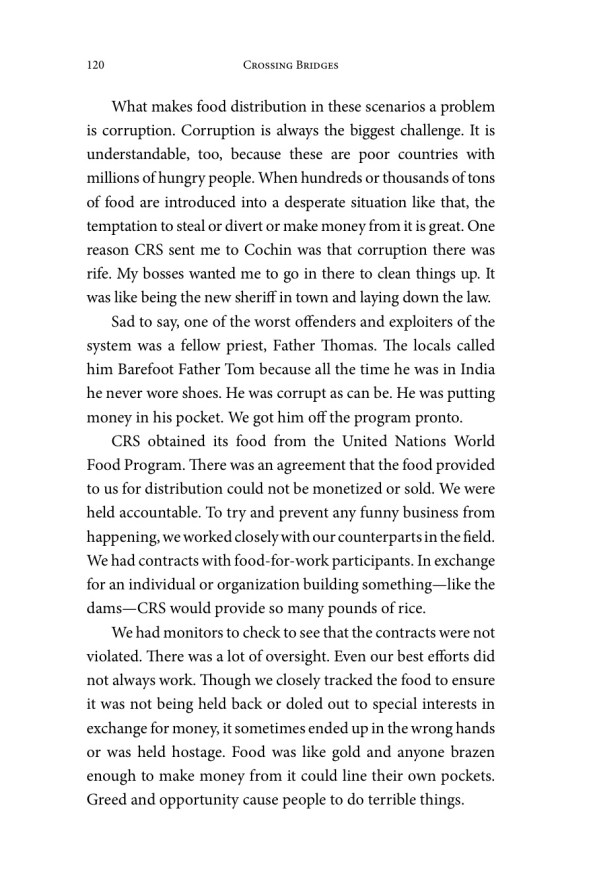

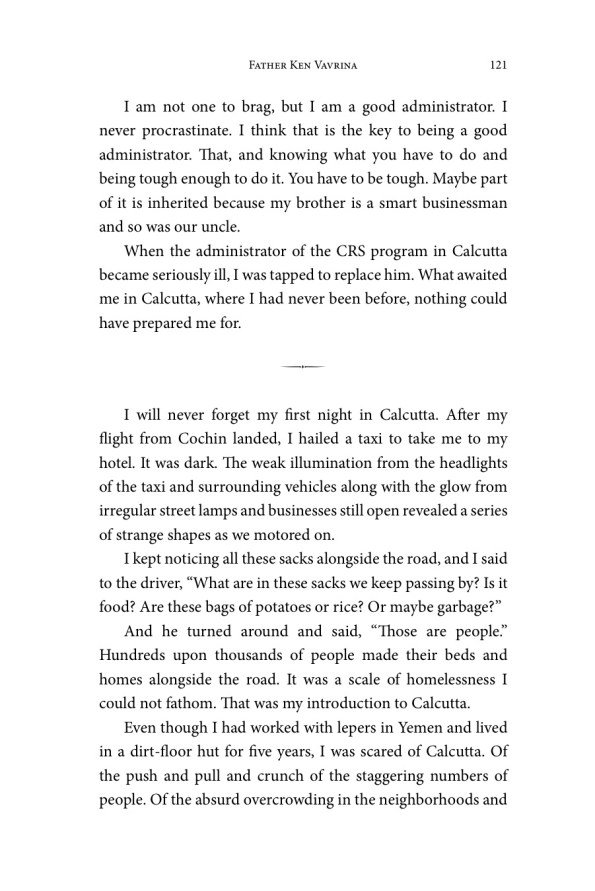

“I will never forget my first night in Calcutta. I said to the driver, ‘What are in these sacks we keep passing by?’ ‘Those are people.’ Hundreds upon thousands of people made their beds and homes alongside the road. It was a scale of homelessness I could not fathom. That was my introduction to Calcutta.“I was scared of Calcutta. Of the push and pull and crunch of the staggering numbers of people. Of the absurd overcrowding in the neighborhoods and streets. Of the overwhelming, mind-numbing, heartbreaking, soul-hurting poverty. That mass of needy humanity makes for a powerful, sobering, jarring reality that assaults all the senses…

“…only God knows the true size of the population…I often say to religious and lay people alike, ‘Go to Calcutta and walk the streets for six days and it will change your life forever” Walk the streets there for one day and even one hour, and it will change you. I know it did me.”

Vavrina was reunited there with Mother Teresa.

“I spent a lot of time working with Mother, Whenever she had a problem she would come into the office. If there was a natural disaster where her Sisters worked we would always help with food or whatever they needed.”

He witnessed people’s adoration of Mother Teresa wherever she went. There was enough mutual respect between this American priest and Macedonian nun that they could speak candidly and laugh freely in each other’s company. He criticized her refusal to let her Sisters do the type of development work his programs did. He disapproved of how tough she was with her Sisters, whom she demanded live in poverty and restrict themselves to providing comfort care to the sick and dying.

He writes, “I disagreed with Mother and I told her so. I knew the value of development work. Our CRS programs in India were proof of its effectiveness…she listened to me, not necessarily agreeing with me at all…and then went right ahead and did her own thing anyway…I cried the day I left Calcutta in 1991. I loved Calcutta. Mother Teresa had tears in her eyes as well. We had become very good friends. She was the real deal…hands on…not afraid to get her hands dirty.”

Years later he read with dismay and sadness how she experienced the Dark Night of the Soul – suffering an inconsolable crisis of faith.

“I knew her well and yet I never detected any indication, any sign that she was burdened with this internal struggle. Not once in all the time I spent with her did she betray a hint of this. She seemed in all outward appearances to be quite happy and jovial,” he writes. “However, I did know that she was very intense about her faith and her work. In her mind and heart she was never able to do enough. She never felt she did enough to please God, and so there was this constant, gnawing void she felt that she could never fully fill or reconcile.”

Even all these years later Vavrina says his experience in India is never far from his thoughts.

Liberia

CRS next sent him to Liberia, Africa, where a simmering civil war boiled over. His job was getting supplies to people who’d fled their villages. That meant dealing with the most powerful rebel warlord, Charles Taylor, whose forces controlled key roads and regions.

The program Vavrina operated there dispersed $42 million in aid each year, most of it in food and medicine. As in India, goods arrived by ship in port for storage in warehouses before being trucked to destinations in-country. Vavrina often rode in the front truck of convoys that passed through rebel-occupied territories where boys brandishing automatic weapons manned checkpoints. There were many tense confrontations.

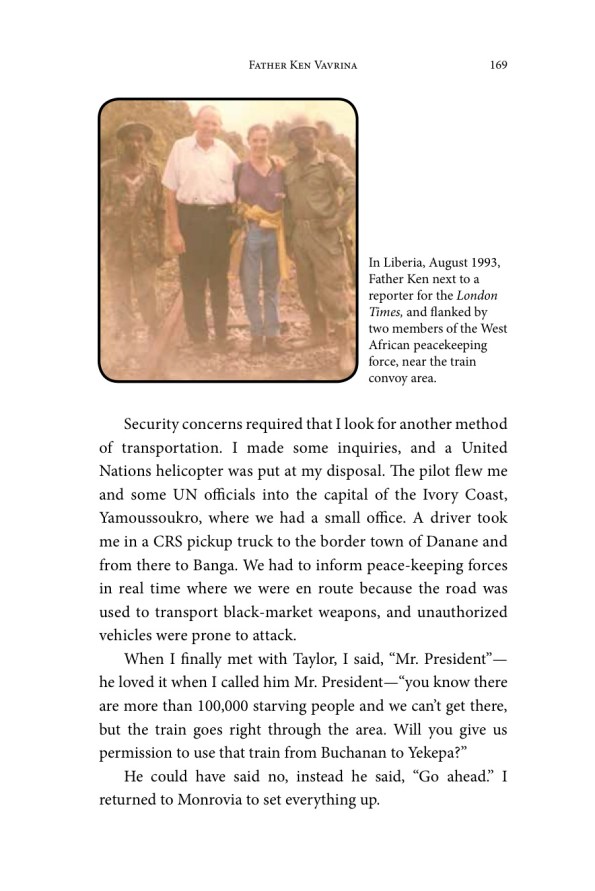

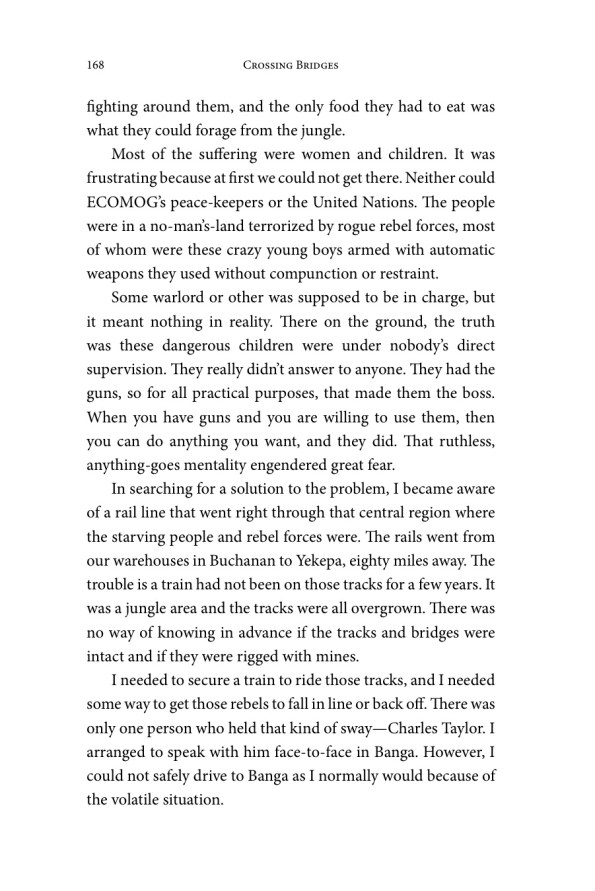

On three occasions Vavrina got Taylor to release a freight train to carry supplies to a large refugee contingent in dire need of food and medicine in the jungle. Taylor provided a general and soldiers for safe passage but Vavrina went along on the first run to ensure the supplies reached their intended recipients.

Everywhere Vavrina ran aid overseas he contended with corruption to one extent or another. Loss through pilfering and paying out bribes to get goods through were part of the price or tax for conducting commerce. Though he hated it, he dealt with the devil in the person of Taylor in order to get done what needed doing. Grim reminders of the carnage that Taylor inflamed and instigated were never lost on Vavrina and on at least once occasion it hit close to home.

“Not for a moment did I ever forget who I was really talking to…I never forgot that he was a ruthless dictator. He was a pathological liar too. He could look you dead in the eye and tell you an out-and-out untruth, and I swear he was convinced he was telling the truth. A real paranoid egomaniac. But in war you cannot always choose your friends.“Hundreds of thousands of innocent people died in Liberia during those civil wars. There were many atrocities. One in particular touched me personally. On October 20, 1992, five American nuns, all of whom I knew and considered friends, were killed. I had visited them at their convent two days before this tragedy. May they rest in peace.”

The killings were condemned worldwide.

His most treacherous undertaking involved a cargo ship, The Sea Friend, he commissioned to offload supplies in the port at Greenville. Only rebels arrived there first. To make matters worse the ship sprung a leak coming into dock. Thus, it became a test of nerves and a race against time to see if the supplies could be salvaged from falling prey to the sea and/or the clutches of rebels. When all seemed lost and the life of Vavrina and his companions became endangered, a helicopter answered their distress call and rescued them from the ugly situation.

Back home

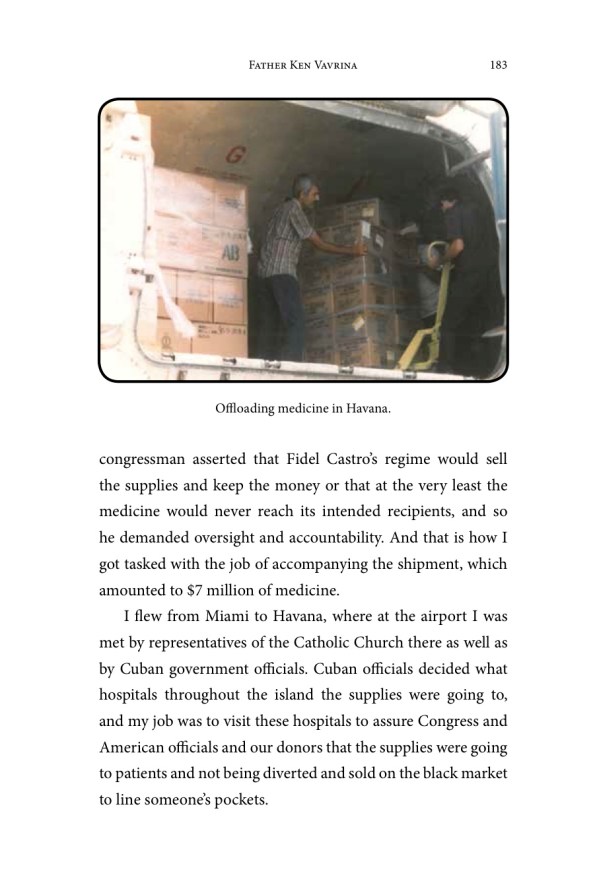

Hs work in Liberia was left unfinished by the country’s growing instability and by his more frequent malaria attacks, which forced him back home to the States. At the request of CRS he settled in New York City doing speaking and fundraising up and down the East Coast. Then he went to work for the Catholic Medical Mission Board, who sent him to Cuba to safeguard millions of dollars in medical supplies for clinics in an era when America’s Cuba embargo was still officially in effect.

During his visit Vavrina met then-Archbishop of Havana, Jamie Ortega, now a cardinal. Vavrina supported then and applauds now America normalizing relations with Cuba.

He also appreciates the progressive stances Pope Francis has taken in extending a more welcoming hand by the Church to divorced and gay Catholics and in encouraging the Church to be more intentional about serving the poor and disenfranchised. The pope’s call for clergy to be good pastors and shepherds who work directly work with people in need is what Vavrina did and continues doing.

“This is exactly what the Holy Father is saying. They need to get out of the office and stop doing just administration and reach out to people who are being neglected. A shepherd reaches out to the lost sheep. Jesus talks about that all the time,” Vavrina says.

As soon as Vavrina ended his missions work overseas he intended coming back to work in Omaha’s inner city but he kept getting sidetracked. Then he got assigned to serve two rural Neb. parishes. Finally, he got the call to pastor St. Richard’s in North Omaha, where he was sent to heal a congregation traumatized by the pedophile conviction of their former pastor, Father Dan Herek.

Vavrina writes, “Those wounds did not heal overnight. I knew going in I would be inheriting a parish still feeling raw and upset by the scandal. Initially my role was to help people deal with the anger and frustration and confusion they felt. Those strong emotions were shared by adults and youths alike.”

During his time at St. Richard’s he immersed himself in the social action group, Omaha Together One Community.

Facing declining church membership and school enrollment, the archdiocese decided to close St. Richard’s, whereupon Vavrina was assigned the parish he’d long wanted to serve – St. Benedict the Moor. As the metro’s historic African-American Catholic parish, St. Benedict’s has been a refuge to black Catholics for generations. Vavrina led an effort to restore the parish’s adjacent outdoor recreation complex, the Bryant Center, which has become a community anchor for youth sports and educational activities in a high needs neighborhood. He also initiated an adopt a family program to assist single mothers and their children. Several parishes ended up participating.

Poverty and unemployment have long plagued sections of northeast Omaha. Those problems have been compounded by disproportionately high teenage pregnancy, school dropout, incarceration and gun violence rates. Vavrina saw too many young people being lost to the streets through drugs, gangs or prostitution. Many of these ills played out within a block or two of the rectory he lived in and the church he said Mass in. He’s encouraged by new initiatives to support young people and to revitalize the area.

Wherever he pastored he forged close relationships. “One of the benefits of being a pastor is that the parish adopts you as one of their own, and the people there become like a family to you,” he writes.

At St. Ben’s that sense of family was especially strong, so much so that when he announced one Sunday at Mass that the archbishop was compelling him to retired there was a hue and cry from parishioners. He implored his flock not to make too big a fuss and they mostly complied. No, he wasn’t ready to retire, but he obeyed and stepped aside. Retirement gave him time to reflect on his life for the book he ended up publishing through his own Uplifting Publishing and Concierge Marketing Publishing Services in Omaha.

Father Ken enjoying our book

“I’ve had a wonderful life, oh my,” he says.

Now that that wonderful life has been distilled into a book, he hopes his journey is instructive and perhaps inspiring to others.

“I wrote the book hoping it was going to encourage people to cross bridges and to reach out to people who otherwise they would not reach out to. That’s exactly what Pope Francis is talking about.”

Besides, he says, crossing bridges can be the source of much joy. The life story his book lays out is evidence of it.

“That story just says how great a life I have had,” he says.

“It is my prayer that the travels and experiences I describe in these pages serve as guideposts to help you navigate your own wanderings and crossings.“A bridge of some sort is always before you…never be afraid to open your heart and speak your mind. We are all called to be witnesses. We are all called to testify. To make the crossing, all that is required is a willing and trusting spirit. Go ahead, make your way over to the other side. God is with you every step of the way. Take His hand and follow. Many riches await.”

Order the book at http://www.upliftingpublishing.com.

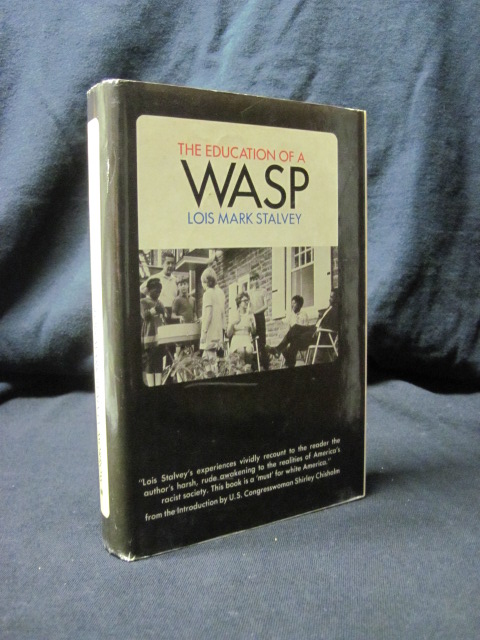

A WASP’s racial tightrope resulted in enduring book partially set in 1960s Omaha

White people don’t know shit about black people.

That’s an oversimplification and generalization to be sure but it largely holds true today that many whites don’t know a whole lot about blacks outside of surface cultural things that fail to really get to the heart of the black experience or what it means to be black in America. That was certainly even more true 50 years ago or so when the events described in the 1970 book The Education of a WASP went down. The book’s author, the late Lois Mark Stalvey, was a White Anglo-Saxon Protestant and thus WASP Omaha homemaker in the late 1950s-early 1960s when she felt compelled to do something about the inequality confronting blacks that she increasingly became aware of during the civil rights movement. Her path to a dawning social consciousness was aided by African-Americans in Omaha and Philadelphia, where she moved, including some prominent players on the local social justice scene. Ernie Chambers was one of her educators. The late Dr. Claude Organ was another. Stalvey talked to and learned from socially active blacks. She got involved in The Cause through various organizations and initiatives. She even put herself and her family on the line by advocating for open housing, education, and hiring practices.

Her book made waves for baring the depths of her white prejudice and privilege and giving intimate view and voice to the struggles and challenges of blacks who helped her evolve as a human being and citizen. Those experiences forever changed her and her outlook on the world. She wrote followup books, she remained socially aware and active. She taught multicultural and diversity college courses. She kept learning and teaching others about our racialized society up until her death in 2004. Her Education of a WASP has been and continues being used in ethnic stiudies courses around the country.

A WASP’s racial tightrope resulted in enduring book partially set in 1960s Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the November 2015 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

You’ve got to be taught to be afraid

Of people whose eyes are oddly made,

And people whose skin is a diff’rent shade,

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

When a liberal, white middle-class couple with young kids moved to Omaha from Chicago in the late 1950s they entered this city’s weirdly segregated reality, not uncommon in almost every American city. It was not as public or overtly violent as the segregation in the former Confederate states of the South, but it was no less impactful on the African-American communities in Northern states. Homemaker Lois Mark Stalvey was a former advertising copywriter who once owned her own agency. Her husband Bennett Stalvey was a Fairmont Foods Mad Man.

The Omaha they settled into abided by a de facto segregation that saw blacks confined to two delineated areas. The largest sector, the Near North Side, was bounded by Cuming on the south and Ames on the north and 16th on the east and 40th on the west. Large public housing projects were home to thousands of families. In South Omaha blacks were concentrated in and around projects near the packing plants. Blacks here could generally enter any public place – a glaring exception being the outdoor pool at Peony Park until protestors forced ownership’s hand – but were sometimes required to sit in separate sections or limited to drive-thru service and they most definitely faced closed housing opportunities and discriminatory hiring practices.

This now deceased couple encountered a country club racist culture that upheld a system designed to keep whites and blacks apart. Neither was good at taking things lying down or letting injustices pass unnoticed. But she was the more assertive and opinionated of the two. Indeed, son Ben Stalvey recalls her as “a force of nature” who “rarely takes no for an answer.”

“She was stubborn to accept the accepted norm in those days and that piqued her curiosity and she took it from there,” he says. “She had grown up in her own little bubble (in Milwaukee) and I think when she discovered racial prejudice and injustice her attitude was more like, What do you mean I can’t do that or what do you mean I have to think that way? It was more just a matter of, “Hell, no.”

Though only in Omaha a few years, Stalvey made her mark on the struggle for equality then raging in the civil rights movement.

The well-intentioned wife and mother entered the fray naive about her own white privilege and prejudice and the lengths to which the establishment would go to oppose desegregation and parity. Her headstrong efforts to do the right thing led to rude awakenings and harsh consequences. Intolerance, she learned here and in Philadelphia, where the Stalveys moved after her husband lost his job due to her activism, is insidious. All of which she wrote about in her much discussed 1970 book, The Education of a WASP.

The title refers to the self-discovery journey she made going from ignorance to enlightenment. Blacks who befriended her in Omaha and in Philadelphia schooled her on the discrimination they faced and on what was realistic for changing the status quo.

Among her primary instructors was the late black civic leader and noted physician Dr. Claude Organ and his wife Elizabeth “Betty” Organ and a young Ernie Chambers before his state senator career. In WASP Stalvey only sparingly used actual names. The Organs became the Bensons and Chambers became Marcus Garvey Moses.

A Marshall, Texas native and graduate of Xavier University in New Orleans, Claude Organ was accepted by the University of Texas Medical School but refused admittance when officials discovered he was black. The state of Texas paid the tuition difference between UT and any school a denied black attended. Organ ended up at Creighton University and the state of Texas paid the extra $2,000 to $3,000 a year the private Jesuit school cost, recalls Betty Organ.

His civil rights work here began with the interracial social action group the De Porres Club led by Father John Markoe. Organ became Urban League of Nebraska president and later advised the Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties (4CL). He was on the Catholic Interracial Council board and Mayor’s Biracial Committee.

“He built a lot of bridges,” son Paul Organ says.

Betty Organ got involved, too, supporting “any group that had something to do with making Omaha a better place to live,” she says.

So when Stalvey was introduced to the Organs by a black friend and determined to made them her guides in navigating the troubled racial waters, she couldn’t have found a better pair.

Stalvey met Chambers through Claude Organ.

Chambers says “This woman detected I was somebody who might have some things to offer that would help give her what she called her education. And when I became convinced she was genuine I was very open with her in terms of what I would talk to her about.”

Though it may not seem so now, Chambers says the book’s title was provocative for the time. WASP stands for White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, which defined Stalvey’s background, but racism was rampant across ethnic and religious lines in White America.

“WASP was a term that not everybody to whom it applied embraced. So by using that title she caught people’s attention.”

Ernie Chambers educating Pastor William Youngdahl in “A Time for Burning”

But he admired the “substance” behind the sensation. He admired, too, that the vitally curious Stalvey asked lots of questions.

“I never got the impression as used to happen when I was interviewed by white people that she was ‘studying’ me like a scientist in a lab would study insects. She genuinely was trying to make herself a better person and I think she succeeded.”

This ever apt pupil threw herself into The Cause. Her son Noah Stalvey says, “I can remember meetings at the house. She had a lot of the movers and shakers of the day meeting there. Her goal was to raise us in an environment of tolerance.”

“At times it was lively,” says Ben Stalvey. “There wasn’t much disagreement. We knew what was going on, we heard about things. We met a lot of people and we’d play with their kids.”

All par for the course at the family home in Omaha’s Rockbrook neighborhood. “It wasn’t until well into my teen years I realized my parents were fighting the battle,” Noah says. “I just thought that’s what all parents do.”

His mother headed the progressive Omaha Panel for American Women that advocated racial-religious understanding. The diverse panelists were all moms and the Organ and Stalvey kids sometimes accompanied their mothers to these community forums. Paul Organ believes the panelists wielded their greatest influence at home.

“On the surface all the men in the business community were against it.

Behind the scenes women were having these luncheons and meetings and I think in many homes around Omaha attitudes were changed over dinner after women came back from these events and shared the issues with their husbands. To me it was very interesting the women and the moms kind of bonded together because they all realized how it was affecting their children.”

Betty Organ agrees. “I don’t think the men were really impressed with what we were doing until they found out its repercussions concerning their children and the attitudes their children developed as they grew.”

Stalvey’s efforts were not only public but private. She personally tried opening doors for the aspirational Organs and their seven children to integrate her white bread suburban neighborhood. She felt the northeast Omaha bungalow the Organs occupied inadequate for a family of nine and certainly not befitting the family of a surgeon.

Racial segregation denied the successful professional and Creighton University instructor the opportunity for living anywhere outside what was widely accepted as Black Omaha – the area in North Omaha defined by realtors and other interests as the Near North Side ghetto.

“She had seen us when we lived in that small house on Paxton Boulevard,” Betty Organ says. “She had thought that was appalling that we should be living that many people in a small house like that.”

Cover of the book “Ahead of Their Time: The Story of the Omaha DePorres Club”

Despite the initial reluctance of the Organs, Stalvey’s efforts to find them a home in her neighborhood put her self-educating journey on a collision course with Omaha’s segregation and is central to the books’s storyline. Organ appreciated Stalvey going out on a limb.

Stalvey and others were also behind efforts to open doors for black educators at white schools, for employers to practice fair hiring and for realtors to abide by open housing laws. Stalvey found like-minded advocates in social worker-early childhood development champion Evie Zysman and the late social cause maven Susie Buffett. They were intent on getting the Organs accepted into mainstream circles.

“We were entertained by Lois’ friends and the Zysmans and these others that were around. We went to a lot of places that we would not have ordinarily gone because these people were determined they were going to get us into something,” Betty Organ says. “It was very revealing and heartwarming that she wanted to do something. She wanted to change things and it did happen.”

Only the change happened either more gradually than Stalvey wanted or in ways she didn’t expect.

Despite her liberal leanings Claude Organ remained wary of Stalvey.

“He felt she was as committed as she could be,” his widow says, “but he just didn’t think she knew what the implications of her involvement would be. He wasn’t exactly sure about how sincere Lois was. He thought she was trying to find her way and I think she more or less did find her way. It was a very difficult time for all of us, that’s all I can say.”

Ernie Chambers says Stalvey’s willingness to examine and question things most white Americans accepted or avoided was rare.

“At the time she wrote this book it was not a popular thing. There were not a lot of white people willing to step forward, identify themselves and not come with the traditional either very paternalistic my-best-friend-is-a-Negro type of thing or out-and-out racist attitude.”

The two forged a deep connection borne of mutual respect.

“She was surprised I knew what I knew, had read as widely as I had, and as we talked she realized it was not just a book kind of knowledge. In Omaha for a black man to stand up was considered remarkable.

“We exchanged a large number of letters about all kinds of issues.”

Chambers still fights the good fight here. Though he and Claude Organ had different approaches, they became close allies.

Betty Organ says “nobody else was like” Chambers back then. “He was really a moving power to get people to do things they didn’t want to do. My husband used to go to him as a barber and then they got to be very good friends. Ernie really worked with my husband and anything he wanted to accomplish he was ready to be there at bat for him. He was wonderful to us.”

Stalvey’s attempts to infiltrate the Organs into Rockbrook were rebuffed by realtors and residents – exactly what Claude Organ warned would happen. He also warned her family might face reprisals.

Betty Organ says, “My husband told her, ‘You know this can have great repercussions because they don’t want us and you can be sure that because they don’t want us they’re going to red line us wherever we go in Omaha trying to get a place that they know of.'”

Bennett Stalvey was demoted by Fairmont, who disliked his wife’s activities, and sent to a dead-end job in Philadelphia. The Organs regretted it came to that.

“It was not exactly the thing we wanted to happen with Ben,” Betty Organ says. “That was just the most ugly, un-Godly, un-Christian thing anybody could have done.”

Photos of the late Dr. Claude Organ

While that drama played out, Claude Organ secretly bought property and secured a loan through white doctor friends so he could build a home where he wanted without interference. The family broke ground on their home on Good Friday in 1964. The kids started school that fall at St. Philip Neri and the brick house was completed that same fall.

“We had the house built before they (opponents) knew it,” Betty Organ says.

Their spacious new home was in Florence, where blacks were scarce. Sure enough, they encountered push-back. A hate crime occurred one evening when Betty was home alone with the kids.

“Somebody came knocking on my door. This man was frantically saying, ‘Lady, lady, you know your house is one fire?’ and I opened the door and I said, ‘What?’ and he went, ‘Look,’ and pointed to something burning near the house. I looked out there, and it was a cross burning right in front of the house next to the garage. When the man saw what it was, too, he said, ‘Oh, lady, I’m so sorry.’ It later turned out somebody had too much to drink at a bar called the Alpine Inn about a mile down the road from us and did this thing.

“I just couldn’t believe it. It left a scorch there on the front of the house.”

Paul Organ was 9 or 10 then.

“I have memories of a fire and the fire truck coming up,” he says. “I remember something burning on the yard and my mom being upset. I remember when my dad got home from the hospital he was very upset but it wasn’t until years later I came to appreciate how serious it was. That was probably the most dramatic, powerful incident.”

The former Organ home in Florence where a cross was burned.

But not the last.

As the only black family in St. Philip Neri Catholic parish the Organs seriously tested boundaries.

“Some of the kids there were very ugly at first,” Betty Organ recalls. “They bullied our kids. It was a real tough time for all of us because they just didn’t want to accept the fact we were doing this Catholic thing.”

You’ve got to be taught

To hate and fear,

You’ve got to be taught From year to year,

It’s got to be drummed In your dear little ear

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

Daughter Sandra Organ says, “There were some tensions there. Dad would talk about how to handle these kind of things and to take the high road. But if they used the ‘n’ word we had an opportunity to retaliate because you defend your honor as a black person.

“An older neighbor man didn’t particularly like black people. But his grandson was thrilled to have these five boys to play with, so he became like an extra person in the family. The boy’s family was very kind to us and they kind of brought the grandfather around.”

Betty Organ says things improved with parishioners, too. “It got to the point where they got to know the family and they got to know us and they kind of came around after a few years.”

Sandra says when her brother David suffered severe burns in an accident and sat-out school “the neighborhood really rallied around my mom and provided help for her and tutoring for David.”

Stalvey came from Philadelphia to visit the Organs at their new home.

“When she saw the house we built she was just thrilled to death to see it,” Betty Organ says.

In Philadelphia the Stalveys lived in the racially mixed West Mount Airy neighborhood and enrolled their kids in predominantly African-American inner city public schools.

Ben Stalvey says, “I think it was a conscious effort on my parents part to expose us to multiple ways of living.”

His mother began writing pieces for the Philadelphia Bulletin that she expanded into WASP.

“Mom always had her writing time,” Ben Stalvey notes. “She had her library and that was her writing room and when she in the writing room we were not to disturb her and so yes I remember her spending hours and hours in there. She’d always come out at the end of the school day to greet us and often times she’d go back in there until dinner.”

In the wake of WASP she became a prominent face and voice of white guilt – interviewed by national news outlets, appearing on national talk shows and doing signings and readings. Meanwhile, her husband played a key role developing and implementing affirmative action plans.

Noah Stalvey says any negative feedback he felt from his parents’ activism was confined to name-calling.

“I can remember vaguely being called an ‘n’ lover and that was mostly in grade school. My mother would be on TV or something and one of the kids who didn’t feel the way we did – their parents probably used the word – used it on us at school.”

He says the work his parents did came into focus after reading WASP.

“I first read it when I was in early high school. It kind of put together pieces for me. I began to understand what they were doing and why they were doing it and it made total sense to me. You know, why wouldn’t you fight for people who were being mistreated. Why wouldn’t you go out of your way to try and rectify a wrong? It just made sense they were doing what they could to fix problems prevalent in society.”

Betty Organ thought WASP did a “pretty good” job laying out “what it was all about” and was relieved their real identities were not used.

“That was probably a good thing at the time because my husband didn’t want our names involved as the persons who educated the WASP.”

After all, she says, he had a career and family to think about. Dr. Claude Organ went on to chair Creighton’s surgery department by 1971, becoming the first African-American to do so at a predominately white medical school. He developed the school’s surgical residency program and later took positions at the University of Oklahoma and University of California–Davis, where he also served as the first African-American editor of Archives of Surgery, the largest surgical journal in the English-speaking world.

Claude and Betty Organ

Sandra Organ says there was some queasiness about how Stalvey “tried to stand in our shoes because you can never really know what that’s like.” However, she adds, “At least she was pricking people’s awareness and that was a wise thing.”

Paul Organ appreciates how “brutally honest” Stalvey was about her own naivety and how embarrassed she was in numerous situations.” He says, “I think at the time that’s probably why the book had such an effect because Lois was very self-revealing.”

Stalvey followed WASP with the book Getting Ready, which chronicled her family’s experiences with urban black education inequities.

At the end of WASP she expresses both hope that progress is possible – she saw landmark civil rights legislation enacted – and despair over the slow pace of change. She implied the only real change happens in people’s hearts and minds, one person at a time. She equated the racial divide in America to walls whose millions of stones must be removed one by one. And she stated unequivocally that America would never realize its potential or promise until there was racial harmony.

Forty-five years since WASP came out Omaha no longer has an apparatus to restrict minorities in housing, education, employment and recreation – just hardened hearts and minds. Today, blacks live, work, attend school and play where they desire. Yet geographic-economic segregation persists and there are disproportionate numbers living in poverty. lacking upwardly mobile job skills, not finishing school, heading single-parent homes and having criminal histories in a justice system that effectively mass incarcerates black males. Many blacks have been denied the real estate boom that’s come to define wealth for most of white America. Thus, some of the same conditions Stalvey described still exist and similar efforts to promote equality continue.

Stalvey went on to teach writing and diversity before passing away in 2004. She remained a staunch advocate of multiculturalism. When WASP was reissued in 1989 her new foreword expressed regret that racism was still prevalent. And just as she concluded her book the first time, she repeated the need for our individual and collective education to continue and her indebtedness to those who educated her.

Noah Stalvey says her enduring legacy may not be so much what she wrote but what she taught her children and how its been passed down.

“It does have a ripple effect and we now carry this message to our kids and our kids are raised to believe there is no difference regardless of sexual preference or heritage or skin color.”

Ben Stalvey says his mother firmly believed children are not born with prejudice and intolerance but learn these things.

“There’s a song my mother used to quote which I still like that’s about intolerance – ‘You’ve Got to be Carefully Taught’ – from the musical South Pacific.

“The way we were raised we were purposely not taught,” Ben Stalvey says. “I wish my mother was still around to see my own grandchildren. My daughter has two kids and her partner is half African-American and half Filipino. I think back to the very end of WASP where she talks about her hopes and dreams for America of everyone being a blended heritage and that has actually come to pass in my grandchildren.”

You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late,

Before you are six or seven or eight,

To hate all the people your relatives hate,

You’ve got to be carefully taught!

____________________________________________________________________________

Stalvey’s personal chronicle of social awareness a primer for racial studies

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the November 2015 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

With America in the throes of the 1960s civil rights movement, few whites publicly conceded their own prejudice, much less tried seeing things from a black point of view. Lois Mark Stalvey was that exception as she shared her journey from naivety to social consciousness in her 1970 book The Education of a WASP.

Her intensely personal chronicle of becoming a socially aware being and engaged citizen has lived on as a resource in ethnic studies programs.

Stalvey’s odyssey was fueled by curiosity that turned to indignation and then activism as she discovered the extent to which blacks faced discrimination. Her education and evolution occurred in Omaha and Philadelphia. She got herself up to speed on the issues and conditions impacting blacks by joining organizations focused on equal rights and enlisting the insights of local black leaders. Her Omaha educators included Dr. Claude Organ and his wife Elizabeth “Betty” Organ (Paul and Joan Benson in the book) and Ernie Chambers (Marcus Garvey Moses).

She joined the local Urban League and led the Omaha chapter of the Panel of American Women. She didn’t stop at rhetoric either. She took unpopular stands in support of open housing and hiring practices. She attempted and failed to get the Organs integrated into her Rockbrook neighborhood. Pushing for diversity and inclusion got her blackballed and cost her husband Bennett Stalvey his job.

After leaving Omaha for Philly she and her husband could have sat out the fight for diversity and equality on the sidelines but they elected to be active participants. Instead of living in suburbia as they did here they moved into a mixed race neighborhood and sent their kids to predominantly black urban inner city schools. Stalvey surrounded herself with more black guides who opened her eyes to inequities in the public schools and to real estate maneuvers like block busting designed to keep certain neighborhoods white.

Behind the scenes, her husband helped implement some of the nation’s first affirmative action plans.

Trained as a writer, Stalvey used her gifts to chart her awakening amid the civil rights movement. Since WASP’s publication the book’s been a standard selection among works that about whites grappling with their own racism and with the challenges black Americans confront. It’s been used as reading material in multicultural, ethnic studies and history courses at many colleges and universities.

University of Nebraska-Lincoln associate professor of History and Ethnic Studies Patrick Jones has utilized it in two courses.

“In both courses students had a very positive response to the book,” he says. “The book’s local connections to Omaha literally bring the topic of racial identity formation and race relations ‘home’ to students. This local dynamic often means a more forceful impact on Neb. students, regardless of their own identity or background.

“In addition, the book effectively underscores the ways that white racial identity is socially constructed. Students come away with a much stronger understanding of what many call ‘whiteness’ and ‘white privilege” This is particularly important for white students, who often view race as something outside of themselves and only relating to black and brown people. Instead, this book challenges them to reckon with the various ways their own history, experience, socialization, acculturation and identity are racially constructed.”

Patrick Jones

Jones says the book’s account of “white racial identity formation” offers a useful perspective.

“As Dr. King, James Baldwin and others have long asserted, the real problem of race in America is not a problem with black people or other people of color, but rather a problem rooted in the reality of white supremacy, which is primarily a fiction of the white mind. If we are to combat and overcome the legacy and ongoing reality of white supremacy, then we need to better understand the creation and perpetuation of white supremacy, white racial identity and white privilege, and this book helps do that.

“What makes whiteness and white racial identity such an elusive subject for many to grasp is its invisibility – the way it is rendered normative in American society. Critical to a deeper understanding of how race works in the U.S. is rendering whiteness and white supremacy visible.”

Stalvey laid it all right out in the open through the prism of her experience. She continued delineating her ongoing education in subsequent books and articles she wrote and in courses she taught.

Interestingly, WASP was among several popular media examinations of Omaha’s race problem then. A 1963 Look magazine piece discussed racial divisions and remedies here. A 1964 Ebony profile focused on Don Benning breaking the faculty-coaching color barrier at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The 1966 film A Time for Burning featured Ernie Chambers serving a similar role as he did with Stalvey, only this time educating a white pastor and members of Augustana Lutheran Church struggling to do interracial fellowship. The documentary prompted a CBS News special.

Those reports were far from the only local race issues to make national news. Most recently, Omaha’s disproportionately high black poverty and gun violence rates have received wide attention.

More praise and news for my new book with Father Ken Vavrina

“Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden”

5.0 out of 5 stars “A Humble Man with a Powerful Story” Sept. 1 2015

By Sandra Wendel – Published on Amazon.com

“As a book editor, I find that these incredible heroes among us cross our paths rarely. I am indeed lucky to have worked with Father Ken in shaping his story, which he finally agreed to tell the world. You will enjoy his modesty and humility while serving the poorest of the poor. His story of his first days in the leper colony in Yemen is indeed compelling, as is his survival in prison in Yemen. Later, his work in Calcutta, Liberia, and Cuba made a difference.”

____________________________________________________

5.0 out of 5 stars Father Ken Vavrina Sept. 28 2015

By Sandra L Vavrina – Published on Amazon.com

“Crossing Bridges. Father Ken’s life is amazing! He is my husband’s cousin and performed our wedding ceremony 51 years ago right after he was ordained.”

____________________________________________________

5.0 out of 5 stars “Great Book” Sept. 1 2015

By ken tuttle – Published on Amazon.com

“Such an amazing life story.”

____________________________________________________

BOOK NOTE:

After Father Ken recoups the cost of the book’s priting, all proceeds will go to Catholic Relief Services and Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Omaha.

BOOK NOTE:

COVER STORY NOTE:

My new book with Father Ken Vavrina, ‘Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden,’ officially releases today – August 26, 2015

My new book with Father Ken Vavrina

Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden

Releases today, August 26, 2015

Order your copies at-

http://www.UpliftingPublishing.com

My new book with Father Ken Vavrina, Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden, officially releases today, August 26, 2015, in conjunction with the birthday of Mother Teresa. He variously knew the late nun and humanitarian now in line to become a saint in the Catholic Church as his inspiration, boss, colleague and friend.

Before going overseas to do missionary work the Clarkson, Neb. native served various parishes in the state, including Sacred Heart and Holy Family in Omaha. After years away serving the poorest of the poor, he returned home and served at St. Richard and St. Benedict the Moor.

He’s ministered to many diverse communities in his time, including Native American reservations, Hispanic parishes and inner city African-American congregations. He is a long-time social justice champion and an outspoken equal rights advocate. He’s also served divese populations around the world, including long stints in Yemen, India and Liberia.

The book is the story of this beloved priest’s life and travels – simple acts that moved him, people that inspired him and places that astonished him. Father Vavrina has served as a priest for many years and has served several missions trips to help the needy. Father Ken worked with lepers in Yemen, and was ultimately arrested and thrown in jail under false suspicions of spying. After being forcibly removed from Yemen, he began his tenure with Catholic Relief Services, first in the extreme poverty and over-population of Calcutta in India, and then with warlords in Liberia to deliver food and supplies to refugees in need. Father Ken also spent several years working with Mother Teresa to heal the sick and comfort the dying. Father Ken has spent his life selflessly serving the Lord and the neediest around him, while always striving to remain a simple, humble man of God.

The book features a beautiful full-color album with Father Vavrina’s photo collection. Crossing Bridges is available online for single copy or bulk purchase at-

http://www.UpliftingPublishing.com

It is also available in black and white and Kindle ebook formats on Amazon.com.

Soon to be available in select bookstores. Watch for announcements about signings.

After the costs of publishing are subtracted, all proceeds from this book will be donated to Catholic Relief Services and the Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Omaha. It is Father’s sincere hope that others will read the stories and be inspired to serve their fellow man, either right next door or somewhere across the world.

From the book:

“The very first bridge I crossed was choosing to study for the priesthood, a decision that took me and everyone who knew me by surprise. Then came a series of bridges that once crossed brought me into contact with diverse peoples and their incredibly different yet similar needs.”

From Father Ken:

“I pray this account of my life is not a personal spectacle but a recounting of a most wonderful journey serving God. May its discoveries and experiences inspire your own life story of service.”

EXCLUSIVE EXCERPTS FROM

CROSSING BRIDGES: A PRIEST’S UPLIFTING LIFE AMONG THE DOWNTRODDEN

©2015 Kenneth Vavrina

NOTE: Father Vavrina contracted malaria in Yemen and he’s dealt with malaria attacks ever since. He describes one in the book that ;anded him in the hospital

New endorsement for my Alexander Payne book from James Marshall Crotty

My Alexander Payne book has received a lovely new endorsement. It’s from James Marshall Crotty, an Omaha native who’s made quite a name for himself as a journalist and author. He’s a filmmaker as well. A new edition of my book is forthcoming. It will feature all my “Nebraska” coverage, plus a new cover and new inside graphics.

The new edition is soon to be available on this blog, at Amazon and BarnesandNoble.com, for Kindle and in select bookstores.

About “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film” Crotty says:

“Alex Payne is one of the few remaining auteurs in the Conglomerate Hollywood era. Leo Biga, a Nebraska native like his subject, deftly looks at how the ‘home place’ of Nebraska has shaped and nurtured Payne’s singular artistic vision.”

JAMES MARSHALL CROTTY

Columnist (Forbes, Huffington Post), Director/Producer (Crotty’s Kids)

His endorsement joins those from Kurt Andersen, Dick Cavett, Leonard Maltin, Joan Micklin Silver, and Ron Hull.

Justice champion Samuel Walker calls It as he sees it

UNO professor emeritus of criminal justice Samuel Walker is one of those hard to sum up subjects because he’s a man of so many interests and passions and accomplishments, all of which is a good thing for me as a storyteller but it’s also a real challenge trying to convey the totality of someone with such a rich life and career in a single article. As a storyteller I must pick and choose what to include, what to emphasize, what to leave out. My choices may not be what another writer would choose. That’s the way it goes. What I did with Walker was to make his back story the front story, which is to say I took an experience from his past – his serving as a Freedom Summer volunteer to try and register black voters in Mississippi at the peak of the civil rights movement – as the key pivot point that informs his life’s work and that bridges his past and present. That experience is also juxtaposed with him growing up in a less then enlightened household that saw him in major conflict with his father. My cover profile of Walker is now appearing in the New Horizons newspaper.

Samuel Walker

Justice Champion Samuel Walker calls it as he sees it

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the New Horizons

And justice for all

You could do worse than label UNO professor emeritus of criminal justice Samuel Walker a dyed-in-the-wool progressive liberal. He certainly doesn’t conceal his humanist-libertarian leanings in authoring books, published articles and blog posts that reflect a deep regard for individual rights and sharp criticism for their abridgment.

He’s especially sensitive when government and police exceed their authority to infringe upon personal freedoms. He’s authored a history of the American Ciivil Liberties Union. His most recent book examines the checkered civil liberties track records of U.S. Presidents. He’s also written several books on policing. His main specialization is police accountability and best practices, which makes him much in demand as a public speaker, courtroom expert witness and media source. A Los Angeles Times reporter recently interviewed him for his take on the Albuquerque, NM police’s high incidence of officer-involved shootings, including a homeless man shot to death in March.

“I did a 1997 report on Albuquerque. They were shooting too many people. It has not changed. There’s a huge uproar over it,” he says. “In this latest case there’s video of their shooting a homeless guy (who reportedly threatened police with knives) in the park. Officers approached this thing like a military operation and they were too quick to pull the trigger.”

As an activist police watchdog he’s chided the Omaha Police Department for what he considers a pattern of excessive use of force. That’s made him persona non grata with his adopted hometown’s law enforcement community. He’s a vocal member of the Omaha Alliance for Justice, on whose behalf he drafted a letter to the U.S. Justice Department seeking a federal investigation of Omaha police. No Justice Department review has followed.

The alliance formed after then-Omaha Pubic Safety Auditor Tristan Bonn was fired following the release of her report critical of local police conduct. Walker had a hand in creating the auditor post.

“Our principal demand was for her to be reinstated or for someone else to be in that position. We lobbied a couple mayors. We had rallies and public forums,” he says.

All to no avail.

“The auditor ordinance is still on the books but the city just hasn’t funded it. It’s been a real political struggle which is why I put my hopes in the civic leaders.”

After earning his Ph.D. in American history from Ohio State University in 1973, the Ohio native came to work at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. He met his life partner, Mary Ann Lamanna, a UNO professor emeritus of sociology, in a campus lunchroom. The couple, who’ve never married, have been together since 1981. They celebrated their 30th anniversary in Paris. They share a Dundee neighborhood home.

Though now officially retired, Walker still goes to his office every day and stays current with the latest criminal justice research, often updating his books for new editions. He’s often called away to consult cities and police departments.

He served as the “remedies expert” in a much publicized New York City civil trial last year centering around the police department’s controversial stop and frisk policy. Allegations of widespread abuse – of stops disproportionally targeting people of color – resulted in a lengthy courtroom case. Federal district judge Shira Scheindlin found NYPD engaged in unconstitutional actions in violation of the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments. In her decision, she quoted from Walker’s testimony about what went wrong and what reforms were needed.

Counter notes

Walker’s work is far more than an exercise in academic interest. It’s a deeply personal expression of beliefs and values formed by crucial events of the ’60s. The most momentous of these saw him serve as a Freedom Summer volunteer in the heart of the Jim Crow South at the height of the civil rights movement while a University of Michigan student. Spending time in Mississippi awakened him to an alternate world where an oppressive regime of apartheid ruled – one fully condoned by government and brutally enforced by police.

“There was a whole series of shocks – the kind of things that just turned your world upside down. The white community was the threat, the black community was your haven. I was taught differently. The police were not there to serve and protect you, they were a threat. There was also the shock of realizing our government was not there to protect people trying to exercise their right to vote.”

His decision to leave his comfortable middle class life to try and educate and register voters in a hostile environment ran true to his own belief of doing the right thing but ran afoul of his father’s bigotry. Raised in Cleveland Heights, Walker grew up in a conservative 1950s household that didn’t brook progressivism.

“Quite the reverse. My father was from Virginia. He graduated from Virginia Military Institute. He had all the worst of a Southern Presbyterian military education background. Deeply prejudiced. Made no bones about it. Hated everybody, Catholics especially. Very anti-Semitic. Later in life I’ve labeled him an equal opportunity bigot.

“My mother was from an old Philadelphia Quaker family. It was a mismatch, though they never divorced. She was very quiet. It was very much a ’50s marriage. You didn’t challenge the patriarch. I was the one in my family who did.”

Walker’s always indulged a natural curiosity, streak of rebelliousness and keen sense of social justice. Even as a boy he read a lot, asked questions and sought out what was on the other side of the fence.

As he likes to say, he not only delivered newspapers as a kid, “I read them.” Books, too.

“I was very knowledgeable about public affairs by high school, much more so than any of my friends. I could actually challenge my father at a dinner table discussion if he’d say something ridiculous. Well, he just couldn’t handle that, so we had conflict very much early on.”

He also went against his parents’ wishes by embracing rock and roll, whose name was coined by the legendary disc jockey, Alan Freed. The DJ first made a name for himself in Akron and then in Cleveland. In the late 1940s the owner of the Cleveland music store Record Rendezvous made Freed aware white kids were buying up records by black R&B artists. Walker became one of those kids himself as a result of Freed playing black records on the air and hosting concerts featuring these performers. Freed also appeared in several popular rock and roll movies and hosted his own national radio and television shows. His promotion contributed to rock’s explosion in the mainstream.

As soon as Walker got exposed to this cultural sea change, he was hooked.

“I’m very proud to have been there at the creation of rock and roll. My first album was Big Joe Turner on Atlantic Records. Of course, I just had to hear Little Richard. I loved it.”

Like all American cities, Cleveland was segregated when Walker came of age. In order to see the black music artists he lionized meant going to the other side of town.

“We were told by our parents you didn’t go down over the hill to 105th Street – the center of the black community – because it was dangerous. Well, we went anyway to hear Fats Domino at the 105th Street Theatre. We didn’t tell our parents.”

Then there was the 1958 Easter Sunday concert he caught featuring Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis headlining a Freed tour.

“My mother was horrified. I think my generation was the first for whom popular cultural idols – in music and baseball – were African- Americans.”

In addition to following black recording artists he cheered Cleveland Indians star outfielder Larry Doby (who broke the color barrier in the American League) and Cleveland Browns unning back Jim Brown.

More than anything, he was responding to a spirit of protest as black and white voices raised a clarion call for equal rights.

“Civil rights was in the air. It was what was happening certainly by 1960 when I went to college. The sit-ins and freedom rides. My big passion was for public interest. The institutionalized racism in the South struck us as being ludicrous. Now it involved a fair amount of conflict to go to Miss. in the summer of ’64 but what I learned early on at the most important point in my life is that you have to follow your instincts. If there is something you think is right or something you feel you should do and all sorts of people are telling you no then you have to do it.

“That has been very invaluable to me and I do not regret any of those choices. That’s what I learned and it guides me even today.”

![[© Ellen Lake]](https://i0.wp.com/www.crmvet.org/crmpics/64fs_gulfport1.jpg)

Photo caption:

Walker on far left of porch of a Freedom Summer headquarters shack in Gulfport, Miss.

Mississippi burning

He never planned being a Freedom Summer volunteer. He just happened to see an announcement in the student newspaper.