A lot of you know me as a frequent and longtime contributor with The Reader, for whom I’ve written more than a thousand stories since 1996, including hundreds of cover pieces. Beyond The Reader, I am fortunate to own extended relationships with several other publications. I was a major contributor to the Jewish Press for well over a decade. My tenures with Omaha Magazine and Metro Magazine are both more than a decade old now. But perhaps my longest-lived contributor relationship has been with the New Horizons, a monthly newspaper published by the Eastern Nebraska Office on Aging. Editor Jeff Reinhardt and I are committed to positive depictions of aging that illustrate in words and images the active, engaged lifestyles of people of a certain age. Older adult living doesn’t need to follow any of the outdated prescriptions that once had folks at retirement age slowing down to a crawl and more or less retreating from life. That’s not at all how the people we profile approach the second or third acts of their lives. No, our subjects are out doing things, working, creating, traveling, making a difference. My latest profile subjects for the Horizons, Bob and Connie Spittler, are perfect examples. They are in their 80s and still living the active, creative lives that have always driven their personal and professional pursuits. He makes still and moving images. He pilots planes. She writes essays, short stories and books. They travel. They enjoy nature. Sometimes they combine their images and words together in book projects. Bob and Connie are the cover subjects in the January 2016 issue. They join a growing list of folks I’ve profiled for the Horizons who embody such precepts of health aging as keeping your mind occupied, doing what you enjoy, following youe passion, cultivating new interests and discovering new things. The Spittlers are also in a long line of dynamic older couples I’ve profiled – Jose and Linda Garcia, Vic Gutman and Roberta Wilhelm, Josie Metal-Corbin and David Corbin, Ben and Freddie Gray. You can find many of my Horizons stories on my blog, Leo Adam Biga’s My Inside Stories at leoadambiga.com.

NOTE: ©Photos by Jeff Reinhardt, New Horizons Editor, unless otherwise indicated.

Bob and Connie Spittler outside their Brook Hollow home

Creative couple: Bob and Connie Spittler and their shared creative life 60 years in the making

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the January 2016 issue of the New Horizons

Once a creative, always a creative.

That’s how 80-something-year-olds Bob and Connie Spittler have rolled producing creative projects alone or together for six decades. Their work spans television commercials, industrial films, slideshows and books.

Bob, a photographer and filmmaker, these days experiments making art photos. Connie, a veteran scriptwriter, is now an accomplished essayist, short story writer and novelist. Her new novel, the tongue-in-cheek titled The Erotica Book Club for Nice Ladies, has found a receptive enough audience she’s writing a sequel. The book is published by Omaha author-publisher Kira Gale and her River Junction Press.

This past summer Bob and Connie hit the highway for a five-state book tour. Their stops included signings at the American Library Association Conference in San Francisco and the Tattered Cover in Denver. Following an intimate reading at a Berkeley, Calif. couple’s home she and Bob stayed the night. It harkened back to the RV road trips they made with their four kids.

On social media she termed the tour “an author’s dream.” It was especially gratifying given Bob endured a heart angioplasty and stent earlier in 2015.

Connie was also an invited panelist at an Austin, Texas literary event.

“All in all, an unforgettable year of healing, friendship, interesting places and great people,” she wrote in a card to family and friends.

Sharing a love for the outdoors, the Soittlers have applied their respective talents to splendid nature books. The Desert Eternal celebrates the ecosystem surrounding the home they shared in the foothills of the Catalina Mountains in Arizona, where they “retired” after years running their own Omaha film production biz

“When we want down to Tucson we weren’t going to be working together. We were just going to do our own thing,” she says. “We’ve always been able to kind of follow what we want to do. So I started writing literary things and he was out taking pictures. I had a lumpectomy and the day I came home I’m looking out at the Catalina Mountains and I thought, you know it’s strange Bob and I both think we’re doing our own thing when we’re doing the same thing, we’re just each doing it in our own way. We were both doing the desert.

“We lived between two washes the coyotes and other wildlife came through. I had seven weeks of radiation and I had the idea of putting our work together. I downloaded all my essays on the desert and every morning before radiation I’d go into his office and together we’d look through his photo archive for images he’d taken that matched the words I’d written. Well, by the time we got to the end we had 114 photos – enough for a book. Bob formatted it. It came back (from the printer) the day my radiation finished. It was just this cycle.”

Another of their books, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, documents the wild-in-the-city sanctuary around the southwest Omaha home they’ve lived in since 2010, when they returned from their Arizona idyll. Their home in the gated Sleepy Hollow neighborhood abuts four interconnected ponds that serve as habitat for feathered and furry creatures. The inspiration the couple finds in that natural splendor gets expressed in her words and his images.

“Words and images are perfect for each other,” Connie says by way of explaining what makes her and Bob such an intuitive match.

The couple met at Creighton University in the early 1950s. They studied communications and worked on campus radio, television, theater productions together. He was from the big city. She was from a small town, But they hit it off and haven’t stopped collaborating since.

The couple’s original office, ©Bob Spittler

Her writerly roots

The former Connie Kostel grew up in South Dakota. This avid reader practically devoured her entire hometown library.

Connie developed an affection for great women writers. “I love Emily Dickinson. Her poems are short and kind of pithy. She always has one thought in there that just kind of sticks with you.” Other favorites include Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Christina Rossetti, Jane Austen.

“I like a lot of classics.”

Terry Tempest Williams is a contemporary favorite.

Success in school got her thinking she might pursue writing.

“I think it was in the sixth grade I won an essay competition. It had to be on the topic of how we increased production on our family flax farm. Well, there were some farm kids in my grade but I don’t think anybody grew flax. My father was a funeral director. But I got the encyclopedia and I found out some facts about flax and I wrote an essay and I won. I think I got $25 or something. i mean it was like, Wow, I think I should be a writer. That sparked my interest.”

She attended the Benedictine liberal arts Mount Marty College in Yankton, S.D., a then-junior college for girls.

“I got a scholarship there. I was interested in writing and I was going to have to transfer anyway and I began to see radio and TV as one way maybe I could make a living writing rather than writing short stories and novels and so forth. So I decided to do that. My parents researched it out and found Creighton University for me, It had one of the few programs with television, radio and advertising,”

His Army detour

Meanwhile, Bob graduated from Omaha Creighton Prep before getting drafted into the U.S. Army. In between, he earned his private pilot’s license, the start of a lifelong affair with flying that’s seen him own and pilot several planes he’s utilized for both work and pleasure. Prior to the Army he began fooling around with a camera – a Brownie.

He recently put together a small book for his family about his wartime stint in Korea. He had no designs on doing anything with photography when he began documenting that experience.

“Everybody bought a camera over there and I bought an Argus C3. I just got interested in taking pictures for something to do. I learned how to use it and I just took a lot of pictures. I didn’t think it was going anywhere. It was just a hobby, you know.”

But those early photos show a keen eye for composition. He was, in short, a natural. The book he did years later, titled My Korea 1952 to 1953, gives a personal glimpse of life in the service amidst that unfamiliar culture and forbidding environment.

The Army assigned Spittler to intelligence work.

“My specialty was artillery but I was put in what they called G2 Air (part of Corps Intelligence). I went to a school in Japan. Back in Korea I coordinated the Air Force with the artillery in the CORPS front.”

Spittler relied on wall maps and tele-typed intel to schedule flights by Air Force photo-reconnaissance planes. “When I first arrived P-51 Mustangs were the planes used. Then after about six months they shifted to the F-80 Shooting Star,” he writes. “In winter a little pot-bellied kerosene stove warmed our tent. At night it had to be turned off and lighting it on a cold morning, below zero, was painful, It took 10 minutes before it even thought about giving heat.”

The closest he came to action was when a Greek mortar platoon on the other side of a river running past the American camp fired shells into a nearby hill, causing the GIs to scramble for cover.

Though he didn’t pilot any aircraft there he did find ways to feed his flying fix.

He writes, “Since my job was using radio contact with reconnaissance flights every day I became ‘talking friendly’ with some of the pilots. One of them agreed to give me a jet ride…”

Bob Spittler

That ride was contingent on Spittler making his way some distance to where the sound-breaking aircraft were based. “Come hell or high water I wasn’t going to pass up that offer,” he writes. With no jeep available, he hitchhiked his way southwest of Seoul and got his coveted ride in a T-33. From 33,000 feet he sighted the “double bend’ of the Imjin River pilots used as a rendezvous landmark – something he’d heard them often reference in radio chatter.

At Spittler’s urging the pilot did some loops. Aware his guest was a flier himself the pilot let Spittler put the jet into a roll. But before he could complete the pull out the pilot took over when Spittler began losing control in the grip of extreme G-forces he’d never felt before. An adrenalin rush to remember.

Kindred spirits

After a year in-country Bob eagerly resumed the civilian life he’d put on hold. What he did to amuse himself in the Army. photography, became a passion. When he and Connie met at Creighton they soon realized they shared some interests and ambitions. They were friends first and dated off and on. She was entranced by the romance of this tall, strapping veteran who took her up in his Piper Cub. He was drawn to her petite beauty and unabashed intelligence and independence.

Besides their mutual attraction, they enjoyed working in theater productions. They even appeared in a few plays together. Connie’s passion for theater extended to teaching dramatic play at Joslyn Art Museum. She also enacted the female lead, Lizzie, in an Omaha Community Playhouse production of The Rainmaker.

The pair benefited from instructors at Creighton, including two Jesuit priests who were mass communications pioneers. Before commercial television went on the air in Omaha, Rev. Roswell Williams trained production employees of WOW-TV with equipment he set up at the school. He founded campus radio station KOCU to prepare students for broadcasting careers. He implemented an early closed circuit television systems used to teach classes.

Connie Spittler works the board as Rex Allen gets ready to shoot a scene in the 28-minute film on the story of Ak-Sar-Ben. Published Nov. 16, 1968. (Richard Janda/The World-Herald).

“He was the person that brought television to Creighton University,” Connie says. “He was interested in it in students learning about it.”

Rev. Lee Lubbers was an art professor whose kinetic sculptures experimental, film offings and international satellite network, SCOLA, made him an “avant garde” figure.

“It was so unusual to have him be here and do what he did,” Connie says. “He stirred things up for sure.”

Right out of college she and Bob worked in local media. He directed commercials and shows at WOW-TV. She was a continuity director, advertising scriptwriter and director at fledgling KETV. She also worked in advertising at radio station KFAB.

Bob’s father was an attorney and there was an expectation he would follow suit but he had other plans.

“My father wanted me to be a lawyer and I just kept fighting that,” he recalls. “The gratifying thing about that is that after about 10 years of being in business he said, ‘I’m really kind of glad you didn’t go into it.'”

Bob calls those early days of live TV “fun.”

“I did little 10 second spots for Safeway. They’d just give me the copy and have me go shoot a banana or something. Well, one night I hung them up in the air and swung them and moved the camera and they were flying all over the place and Safeway just loved it.

“But it changed so much with (video )tape coming in. You can always look back and say, ‘Boy, what we could have done if we’d had that.'”

Taking the plunge

Bob and Connie then threw caution aside to launch a film production company from their basement. Don Chapman joined them to form Chapman-Spittler Productions. While leaving the stability of a network affiliate to build a business from scratch might have been a scary proposition for some, it fit Bob to a tee.

“To be honest with you I’m not a team player and I’m not a leader. I’m kind of a loner,” he says. “I could see corporate-wise I wouldn’t get anywhere. I had ideas and things I wanted to do myself. When I did get something done it was always off by myself and I figured out that was the way I wanted it.”

The fact that Bob and Connie brought separate skill sets to the table helped make them work together.

“We didn’t do the same things, that was part of it, so we weren’t competing with each other,” she says. “One other very important thing she did – she kept the books,” Bob notes.

It was unusual for a married couple to work together in the communications field then. Connie was also a rarity as a woman in the male-dominated media-advertising worlds.

She’s long identified as a feminist.

“I was a working woman in the ’50. We were just women that wanted to be able to work, to be able to make a living wage, that wanted to have a family and kids if we chose to but not that we had to.”

There were a few occasions when her gender proved an issue.

“Northern Natural Gas was interviewing for a position and they said there’s no way we can accept a female for this because this job entails going to a lot of parties that get too rowdy, so we’re sorry. When I was at KETV we were doing a documentary about SAC (Strategic Air Command) in-air refueling missions. I wanted to go up so I could write about it, but base officials said we can’t send up a woman, so I couldn’t do that. The station did send up a male director and he came back and told me about it and I wrote the script

“Otherwise, I don’t think I did experience discrimination.”

Bob’s beloved Piper Cub, ©Bob Spittler

She wasn’t taking any chances though when she broke into the field.

“I was one of the first people hired before KETV went on the air. My job was as an administrative assistant to work with New York (ABC). That was one place where I didn’t know if there’d be any problem with my being a woman so instead of signing letters Connie Kostel (this was before she was married), I signed them Con Kostel, so they wouldn’t know what sex I was. I didn’t have any problems.”

Connie will never forget the time she wrote a promo for a Hollywood actor on tour promoting his new ABC Western series.

“I directed him in the promo. When I got home Bob said, ‘How’d it go with the guy from Hollywood?’ I said, ‘He’s nice looking but he’s a loser, He had the personality of a peach pit. I just didn’t get anything from him at all.'”

She was referring to James Garner, whose Maverick became a hit.

In retrospect, she chalks up his lethargy to being exhausted after a long tour. “Thank heavens I didn’t want to be a talent scout.”

The salad days

She says when she and Bob had their own business she was put “in charge of some really big sales meetings” by clients who entrusted her with writing-producing multi-screen slide shows. These elaborate productions cost tens, even hundreds of thousands of dollars and often involved name narrators, such as Herschel Bernardi and Rex Allen.

She wrote-produced a 9-screen, 14-projector show for Leo A. Daly having never produced even a single-screen slide show.

“Inspired in the late ’60’s by our plane trips to the Montreal World Fair and the San Antonio HemisFair, Bob and I were both excited by multi-screen shows.”

Once, Connie was asked to produce show in three days to be shown in a tent in Saudi Arabia.

“I always wondered about the extension cord,” she quips.

Bob says Connie was accepted as an equal by the old boys network they operated in. “I never saw any signs of any rejection.” Besides, he adds, “she got along real well with people” and “she was good.”

For her part, Connie felt right at home doing projects for Eli Lilly, Mutual of Omaha, Union Pacific, ConAgra, Ak-Sar-Ben, the Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce and many other clients.

“I loved it, I absolutely loved it. And the thing I loved about the writing I did was that each one was a different subject. I’d go visit a big company like Leo A. Daly and they’d introduce me to their top people to interview. I’d be given all these research books and reports to read. It was like a continuing education. Working on the Daly account I learned a lot about architecture.

“Almost anything turned out to be really interesting once I talked to the people who worked there who were excited about their work.”

Their projects played international film festivals and earned industry awards. Bob worked with Galen Lillethorup at Bozell and Jacobs to produce the ‘The Great Big Rollin’ Railroad’ commercials for Union Pacific, which won the prestigious Clio for B & J. Bob recalls the North Platte, Neb. shoot as “fun,” adding, “We got a lot of attention out of it and we did get other business from it.” A few years later, Spittler Productions received their own Clio recognition for an Omaha Chamber project. Assignments took them all over the U.S. Bob would often do the flying.

“Bob either shot, scouted or landed for business purposes and I traveled to locations to research, write and produce sales meetings in every state in the U.S. with the exception of Alaska, Hawaii, Maine and Rhode Island,” Connie says.

One time when Bob let someone else do the flying he and a Native American guide caught a helicopter that deposited them atop a Wyoming mesa so he could capture a train moving across the wilderness valley.

“I sat up there with my Arriflex and that old Indian and waited for that train to come and neither of us could understand the other,” he recalls.

Connie once wrote liner notes for a City of London Mozart Symphonia produced by Chip Davis and recorded in Henry Wood Hall, London. Davis recommended her to Decca Records in London to write liner notes for a Mormon Tabernacle Choir album.

At its peak Chapman-Spittler Productions did such high profile projects the partners opened a Hollywood office. Spittler worked with big names Gordon McCrae and John Cameron Swayze.

The Nebraskans made their office a Marina del Rey yacht, the Farida, supposedly once owned by King Farouk and named after his wife.

“On one occasion I flew a Moviola (editing machine) out there and we edited one of the Union Pacific commercials on the boat over in Catalina,” Bob remembers.

An InterNorth commercial was edited there as well.

Connie adds, “I used the yacht as a wonderful place to write scripts.”

“Ours was 40-foot. We were able to sleep on it. I took the boat out a lot. When we left, that’s where it stayed,” Bob says. “Our boat was right next to Frank Sinatra’s boat off the Marina del Rey Hotel. His was a converted PT-boat.”

Bob also did his share of flying up and down the Calif. coast. Connie wedded her words to his images to tell stories.

One of Bob and Connie’s favorite projects was working with Beech Aircraft. Using aerial photography Bob shot in several states, they produced a film on the pressurized Baron and later a film on the King Air for the Beechcraft National Conference in Dallas, Texas

The variety of the projects engaged her.

“Curiosity is my favorite thing,” she acknowledges.

A hungry mind is another attribute she shares with her mate, as Bob’s a tinkerer when it comes to mechanical and electronic things.

“Bob is curious, too,” she says. “He’s always trying to think of something to invent. Years ago he went out and brought home one of the first PCs – a TRS 80. He wanted to play around with it. Then he pushed me into playing around with it and then he made all the kids learn it so they could do their college applications on the computer. So he dragged the whole family into the computer generation.”

The way Bob remembers it, “When I brought that first computer home we had it for a week and I was still trying to figure out how to turn the damn thing on and my son was programming it. He taught me. But that was neat. I’m way behind now on technology,” though he has digital devices to share and store his work.

Connie Spittler

Reinventing themselves

Bob and Connie’s collaborations continued all through the years they worked with Don Chapman. When that partnership dissolved the couple went right on working together.

“We were complementary I suppose in many ways,” she says. “When we had the business I wrote and produced, he shot and edited, so it just worked.”

By now, Connie’s written most everything there is to write. Being open to new writing avenues has brought rewarding opportunities.

“You have to be open to writing about other things just to keep your mind going. I received a phone call in Tucson one day and this person said, ‘We heard about you and we wondered if you’d come read your cowboy poetry at our trail ride?’ I’d never written any cowboy poetry but it sounded so much fun. I said, ‘Let me think about that.’ Well, I like cowboys and nature and all these things, so I agreed to do it. Bob and I ended up making this little book Cowboys & Wild, Wild Things.”

When she got around trying her hand at fiction writing, it fit like a glove.

“I was writing my first fiction piece and Bob said to me, ‘Do you know for the first time since we’ve come down here every time you come out of your office you’re smiling?’ Before, my projects were all kind of heavy, fact-laden subjects. I mean, there was creativity but it was mostly how do you take this subject and make it interesting. With the novel, I could make it anything I want.”

She hit her fiction stride with the books Powerball 33 and Lincoln & the Gettysburg Address.

A project that brought her much attention is the Wise Women Videos series she wrote about individuals who embody or advocate positive aging attributes. The videos have been widely screened. For a time they served as the basis for a cottage industry that found her teaching and speaking about mind, body, spirit matters.

For the series, she says, “I found interesting women I thought other people should listen to. None of them were famous. They were just women introduced to me or once people knew I was doing the series they would say, Oh, you should talk to this person or that person.”

As the series made its way into women’s festivals and organizations she got lots of feedback.

“When I would get letters from cancer groups or prisons or abused women groups I thought good grief, how wonderful that can happen, that they can ‘meet’ these women through these videos.”

The series is archived in Harvard University’s Library on the History of Women in America.

She’s given her share of writing presentations and talks – “I love to attend book clubs to discuss my books” – but a class on memoir she taught in Tucson took the cake.

“The class was inspired by one of my Wise Women Videos and began with each student telling a story about their first decade in life. Then each time we met the women chose one important memory to tell the group about the next decade. The assignment was to write that story for family, friends or themselves. An interesting thing happened: When the class sessions reached the end of their decades and the class was finished the women were so connected from the experience they continued to meet independently for years afterward.”

Bob and Connie on their deck

Legacy

Connie’s own essays and short stories are published in many anthologies. She achieved a mark of distinction when an essay of hers, “Lint and Light,” inspired by the work and concepts of the late Neb. artist and inventor Reinhold Marxhausen, was published in The Art of Living – A Practical Guide to Being Alive. The international anthology’s editor sent an email letting Connie know the names of the other authors featured in the book. She was stunned to find herself in the company of the Dalai Lama, Mikhail Gorbachev, Deepak Chopra, Desmond Tutu, Jean Boland, Sir Richard Branson and other luminaries.

“I almost fell off the chair. When that happened I was like, I wonder if I should quit writing because I don’t think I’ll ever top that.”

Bob says he always knew Connie was destined for big things. “It didn’t surprise me a bit.”

Much of her work lives on thanks to reissues and requests.

“It’s interesting how you do something and it isn’t necessarily gone,” she says. “Some of those things have a long life. I always say a book lasts as long as the paper lasts.”

Now with the Web her work has longer staying power than ever.

Meanwhile, one of Bob’s photographs just sold in excess of a thousand dollars at a gallery in Bisbee, Arizona.

Living in Tucson Connie says she was spoiled by the “absolutely wonderful writers community” there. She and some fellow women writers created their own salon to talk about art, music, theater and literature. “The one rule was you couldn’t gossip – it was just intellectual, interesting talk,” she says. “One night the subject of erotica came up. The next day I went to a bookstore and I said to this young female clerk, ‘Do you have a place for erotica here?’ And she said, ‘Oh erotica, yes, let me get my friend, she loves erotica, too!’ and they both took me off to the section and told me all their favorite books. I didn’t get any of their favorites, but I did get this one, Erotica: Women’s Writing from Sappho to Margaret Atwood.”

Connie found writers published in its pages she never expected.

“When I opened this book the first thing I saw was Emily Dickinson, then Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte, all these well-known, respected authors. Their work is considered erotica for their time because it was romantic reading with sensual undertones. It’s in your mind, not graphic. I thought it so interesting that that could be erotica. It occurred to me a book club about erotica could be fun.”

Only Connie’s resulting book is not erotica at all but “a cozy mystery.”

“A librarian who gave it 5 stars said, ‘You would not be embarrassed to discuss this book with your mother.'” In the back Connie offers a list of erotica titles for those interested in checking out the real thing.

She’s delighted the book’s being published in the Czech Republic.

“My dad was a hundred percent Czech. I asked the publisher if I could add my maiden name and change the dedication to dedicate it to my dad and my grandmother and Czech ancestors and they said, ‘We’d love that.’ My dad’s been gone a long time and he didn’t have any sons and he always said to me, ‘That’s the end of my line,’ so now I thought it will live on – at least in the Czech Republic.”

Words to live by

Closer to home, Connie’s developed a following for the Christmas Card essays she pens. Her sage observations and sublime wordings are much anticipated. This year’s riffs on the fox that visits their property.

“Sometimes in the late evening he trots along the grasslands and pond. Bob, watching TV down in the family room, has spotted the scurrying fox several times – always unexpected and too quick for his camera lens. I haven’t seen this wild urban creature yet since I’m in bed during the usual prowling gorse. Still, imagining his billowing tail flying by int he dark adds a flurry of magic to the winter night…

“As our dancing, prancing fox moves in and out of focus and time, I think of the surprising people, pets, events and moments that visit our lives. They come and go with reminders to be grateful for unexpected things that happen along the way…fleeting or lingering…illusive…intriguing.

“This season our message comes from the fox, a wish for wisdom, longevity and beautiful surprises. Do keep a look out. You never know who you’ll meet or what you’ll see.”

Finally, as one half of a 57-year partnership, Connie proffers some advice about the benefits of passion-filled living.

“One beautiful thing about writing is that by picking up pencil and paper, or using computer, iPad, you can write anywhere. I’ve written on a beach, by a pool, a yacht and in an RV. I always encourage anyone interested in writing to sit down and go to it. It doesn’t cost any money to try and studies show the creativity of writing keeps the mind alert. And it’s a feeling of accomplishment, if you finish a piece or even if you finish a good day writing.”

The same holds true for filmmaking and photography. And for delighting in the wonders of wild foxes running free.

Follow the couple at http://www.conniespittler.com.

Coming Attraction for 2016…

The new edition of my Alexander Payne book featuring a major redesign, more images and substantial new content that looks back at “Nebraska’ and that looks ahead to “Downsizing.”

RANDOM INSPIRATION

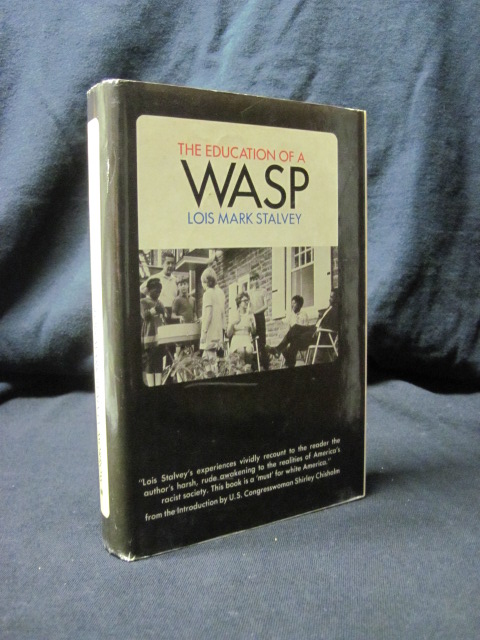

Got a call out of the blue yesterday afternoon from an 86-year-old man in Omaha. He’s a retired Jewish American retailer. He’d just finished reading my November Reader cover story about The Education of a WASP and the segregation issues that plagued Omaha. He just wanted to share how much he enjoyed it and how he felt it needed to be seen by more people. Within a few minutes it was clear the story also summoned up in him strong memories and feelings having to do with his own experiences of bigotry as a Jewish kid getting picked on and bullied and as a businessman taking a stand against discrimination by hiring black clerks in his stores. One of his stores was at 24th and Erskine in the heart of North Omaha and the African-American district there and that store employed all black staff. But he also hired blacks at other storees, including downtown and South Omaha, and some customers were not so accepting of it and he told them flat out they could take their business elsewhere. He also told a tale that I need to get more details about that had to do with a group of outsiders who warned-threatened him to close his North O business or else. His personal accounts jumped from there to serving in the military overseas to his two marriages, the second of which is 60 years strong now. He wanted to know why I don’t write for the Omaha World-Herald and I explained that and he was eager to hook me up with the Jewish Press, whereupon I informed him I contributed to it for about 15 years. I also shared that I have done work for the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society. It turns out the man who brought me and my work to the attention of the Press and the Historical Society, the late Ben Nachman, was this gentleman’s dentist. Small world. I also shared with him why I write so much about African-American subjects (it has to do in part with where and how I grew up). Anyway, it was a delightful interlude in my day talking to this man and I will be sure to talk with him again and hopefully meet him. He’s already assured me he will be calling back. I am eager for him to do so. It’s rare that people call me about my work and this unexpected reaching out and expression of appreciation by a reader who was a total stranger was most appreciated. That stranger is now a friend.

Here is the story that motivated that new friend to call me about:

ABOUT THE BOOKS

Crossing Bridges

“The very first bridge I crossed was choosing to study for the priesthood, a decision that took me and everyone who knew me by surprise. Then came a series of bridges that once crossed brought me into contact with diverse peoples and their incredibly different yet similar needs.”

Father Vavrina has served as a priest for many years, and has served several missions trips to help the needy. Father Ken worked with lepers in Yemen, and was ultimately arrested and thrown in jail under false suspicions of spying. After being forcibly removed from Yemen, he began his tenure with Catholic Relief Services. First in the extreme poverty and over-population of Calcutta in India. Then with warlords in Liberia to deliver food and supplies to refugees in need. Father Ken also spent several years working with Mother Teresa to heal the sick and comfort the dying.

Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden is the story of Father Ken Vavrina’s life and travels – simple acts that moved him, people that inspired him, and places that astonished him. Father Ken has spent his life selflessly serving the Lord and the neediest around him, while always striving to remain a simple, humble man of God.

“I pray this account of my life is not a personal spectacle but a recounting of a most wonderful journey serving God. May its discoveries and experiences inspire your own life story of service.”

REVIEWS

A Humble Man with a Powerful Story

By Sandra Wendel on September 1, 2015

Format: Paperback

As a book editor, I find that these incredible heroes among us cross our paths rarely. I am indeed lucky to have worked with Father Ken in shaping his story, which he finally agreed to tell the world. You will enjoy his modesty and humility while serving the poorest of the poor. His story of his first days in the leper colony in Yemen is indeed compelling, as is his survival in prison in Yemen. Later, his work in Calcutta, Liberia, and Cuba made a difference.

Father Ken Vavrina

By Sandra L Vavrina on September 28, 2015

Format: Paperback Verified Purchase

Crossing Bridges. Father Ken’s life is amazing! He is my husband’s cousin and performed our wedding ceremony 51 yrs ago right after he was ordained.

great book

By ken tuttle on September 1, 2015

Format: Paperback

such an amazing life story

OPEN WIDE

Open Wide

By M. Marill on May 10, 2014

Format: Kindle Edition Verified Purchase

In people or in art, according to Dr. Mark Manhart, “You may not like nor understand everything you see, but at least you will have a truer view of all that went into making the man or the artwork.” This biographical memoir takes the reader through all of his different lives – his “open life” and his “secret life”. Manhart’s professional side finds him a highly trained dentist who is actively engaged in developing new treatments and therapies. His inner passion, which keeps him charged, is his involvement in theatre as a playwright, director, and sometimes an actor.

REVIEWS

The story about the man who has changed dentistry for the better. He can and ha helped peoples everywhere how care and nourish their teeth. His calcium therapy is preventative just as much as it is curative for many dental issues. Like those in holistic medicine who have bucked the medical organizations he has done so with the dental organization forging the way for alternative prevention and care . Check out his website at http://www.calcium therapy.com and educate yourself and try his affordable products before you dismiss this. He deserves recognition for what he has accomplished and I hope it comes to him.

The story of an innovative thinker, inventor, and healer

By Best reads on August 3, 2015

Format: Kindle Edition Verified Purchase

If you read “Open Wide,” you will understand what philosophies have made Dr. Manhart ” a die hard preservationist when it comes to saving peoples teeth…” (167), and how his brilliant invention of materials for dentistry allows him to work miracles, save peoples’ teeth that other dentists are ready to pull, and spare the pain, suffering, and expense of treatments that mainstream dentistry usually pushes. He is also a preservationist with respect to architecture, a talented playwright, actor, director, and producer, is engaged in civic affairs, and has additional wide ranging interests. If you are seeking more humane and successful dental treatments, this book and his website at http://www.calciumtherapy.com are both invaluable. If you want to read about a brilliant and iconoclastic thinker in many realms, this is also a great book. Richard Feynman won the Nobel Prize for physics, Linus Pauling won two Nobel Prizes (for chemistry, and for peace); Dr. Manhart’s research, discoveries, and patented materials are certainly profound enough to merit similar recognition. Unfortunately, you will also read about why dentistry as practiced in the U.S. is often not open to innovation, or able (and willing) to recognize how it has thrived from overcharging for over-treatment that sometimes causes trauma, harm, hopelessness and yet more visits to the dentist.

Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film

I’d be an Alexander Payne fan even if we didn’t share a Nebraska upbringing: he is a masterly, menschy, singular storyteller whose movies are both serious and unpretentious, delightfully funny and deeply moving. And he’s fortunate indeed to have such a thoughtful and insightful chronicler as Leo Biga. –Kurt Andersen, Host of Studio 360.

Long before Alexander Payne arrived as a world-renowned filmmaker, Leo Adam Biga spotted his talent, even screening his thesis project, The Passion of Martin, at an art cinema. By the time Payne completed Citizen Ruth and prepped Election Biga made him a special focus of his journalism. Interviewing and profiling and Payne became a highlight of the writer’s work. Feeling a rapport and trust with Biga, Payne granted exclusive access to his creative process, including a week-long visit to one of his sets. Now that Payne has moved from emerging to established cinema force through a succession of critically acclaimed and popular projects—About Schmidt, Sideways, and The Descendants—Biga has compiled his years of reporting into this book. It is the first comprehensive look anywhere at one of cinema’s most important figures. Go behind-the-scenes with the author to glimpse privileged aspects of the filmmaker at work and in private moments. The book takes the measure of Payne through Biga’s analysis, the filmmaker’s own words, and insights from some of the writer-director’s key collaborators. This must read for any casual fan or serious student of Payne provides in one volume the arc of a remarkable filmmaking journey.

REVIEWS

Biga’s book may be the best answer to this question

By Brent Spencer on November 9, 2015

Format: Kindle Edition

Leo Adam Biga writes about the major American filmmaker Alexander Payne from the perspective of a fellow townsman. The local reporter began writing about Payne from the start of the filmmaker’s career. In fact, even earlier than that. Long before Citizen Ruth, Election, About Schmidt, Sideways, The Descendants, and Cannes award-winner Nebraska. Biga was instrumental in arranging a local showing of an early student film of Payne’s, The Passion of Martin. From that moment on, Payne’s filmmaking career took off, with the reporter in hot pursuit.

The resulting book collects the pieces Biga has written about Payne over the years. The approach, which might have proven to be patchwork, instead allows the reader to follow the growth of the artist over time. Young filmmakers often ask how successful filmmakers got there. Biga’s book may be the best answer to this question, at least as far as Payne is concerned. He’s presented from his earliest days as a hometown boy to his first days in Hollywood as a scuffling outsider to his heyday as an insider working with Hollywood’s brightest stars.

If there is a problem with Biga’s approach, it’s that it can, at times, lead to redundancy. The pieces were originally written separately, for different publications, and are presented as such. This means a piece will sometimes cover the same background we’ve read in a previous piece. And some pieces were clearly written as announcements of special showings of films. But the occasional drawback of this approach is counter-balanced by the feeling you get of seeing the growth of the artist, a life and career taking shape right before your eyes, from the showing of a student film in an Omaha storefront theater to a Hollywood premiere.

But perhaps the most intriguing feature of the book is Biga’s success at getting the filmmaker to speak candidly about every step in the filmmaking process. He talks about the challenges of developing material from conception to script, finding financing, moderating the mayhem of shooting a movie, undertaking the slow and often monk-like work of editing. Biga is clearly a fan (the book comes with an endorsement from Payne himself), but he’s a fan with his eyes wide open. Alexander Payne: His Journey In Film, A Reporter’s Perspective 1998-2012 provides a unique portrait of the artist and detailed insights into the filmmaking process.

Mom and Pop Grocery Stores

Jews have a proud history as entrepreneurs and merchants. When Jewish immigrants began coming to America in greater and greater numbers during the late 19th century and early 20th century, many gravitated to the food industry, some as peddlers and fresh produce market stall hawkers, others as wholesalers, and still others as grocers. Most Jews who settled in Nebraska came from Russia and Poland, with smaller segments from Hungary, Germany, and other central and Eastern European nations. They were variously escaping pogroms, revolution, war, and poverty. The prospect of freedom and opportunity motivated Jews, just as it did other peoples, to flock here. At a time when Jews were restricted from entering certain fields, the food business was relatively wide open and affordable to enter. There was a time when for a few hundred dollars, one could put a down payment on a small store. That was still a considerable amount of money before 1960, but it was not out of reach of most working men who scrimped and put away a little every week. And that was a good thing too because obtaining capital to launch a store was difficult. Most banks would not lend credit to Jews and other minorities until after World War II. The most likely route that Jews took to becoming grocers was first working as a peddler, selling feed, selling produce by horse and wagon or truck, or apprenticing in someone else’s store. Some came to the grocery business from other endeavors or industries. The goal was the same — to save enough to buy or open a store of their own. By whatever means Jews found to enter the grocery business, enough did that during the height of this self-made era. From roughly the 1920s through the 1950s, there may have been a hundred or more Jewish-owned and operated grocery stores in the metro area at any given time. Jewish grocers almost always started out modestly, owning and operating small Mom and Pop neighborhood stores that catered to residents in the immediate area. By custom and convenience, most Jewish grocer families lived above or behind the store, although the more prosperous were able to buy or build their own free-standing home. Since most customers in Nebraska and Iowa were non-Jewish, store inventories reflected that fact, thus featuring mostly mainstream food and nonfood items, with only limited Jewish items and even fewer kosher goods. The exception to that rule was during Passover and other Jewish high holidays, when traditional Jewish fare was highlighted. Business could never be taken for granted. In lean times it could be a real struggle. Because the margin between making it and not making was often quite slim many Jewish grocers stayed open from early morning to early evening, seven days a week, even during the Sabbath, although some stores were closed a half-day on the weekend. Jewish stores that did close for the Sabbath were open on Sunday.

Books by Leo Adam Biga

There’s something appealing about a lone actor assuming dozens of roles in a one-man performance of a multi-character play and John Hardy is bold enough to tackle a much read, seen and loved work, the Charles Dickens classic A Christmas Carol. He performs his adaptation at this fall’s Joslyn Castle Literary Festival, whose theme “Dickens at the Castle” is celebrating the great author’s work in many other ways as well, including lectures and concerts. But clearly Hardy’s one-man rendition of this work that so many of us are familiar with through theater and film versions is the main attraction. I profile Hardy and the “Dickens of a time” he has bringing this work to life in the following story I did for The Reader (www.thereader.com). By the way, if you’ve never been to the Joslyn Castle, use this as your escuse because it is a must-see place in Omaha that really has no equivalent in the metro. You should also check out the arts and culture programming that goes on year-round at the Castle.

Hardy’s one-man “A Christmas Carol” highlights Dickens-themed literary festival

Actor to bring timeless classic to life by enacting dozens of characters

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the November 2015 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The Charles Dickens classic A Christmas Carol has long haunted actor-writer-director John Hardy. Though ghosts have yet to visit him ala Scrooge, the story’s held an enchanted place in Hardy’s heart ever since he got his Equity card acting in a professional stage version.

Much theater work followed but he soon tired of others dictating his artistic life and took creative matters into his own hands. He’s since developed a pair of one-man shows he now tours nationally, including a solo rendition of Christmas Carol. He will perform his adaptation of Carol at the free Nov. 14-December 13 Joslyn Castle Literary Festival, “Dickens at the Castle.”

Joslyn Castle is located at 3902 Davenport Street.

The festival includes lectures, concerts and other Dickens-themed events. But Hardy’s one-man Carol stands apart. In his energetic show he assumes more than 40 roles across a spectrum of Victorian and Industrial Age archetypes.

The well-traveled Hardy is no stranger to Omaha. He performed his other one-man play, Rattlesnake, here. He directed Othello at this past summer’s Nebraska Shakespeare Festival.

Able to pick and choose his projects, he’s reached a golden period in his performing life. But getting there took years of searching.

This native of Texas grew up in New Jersey and got bitten by the theater bug attending plays in New York City. He studied drama and stagecraft under his muse, Bud Frank, at East Tennessee State University. He no sooner graduated then went off to do the starving acting bit in the Big Apple, making the rounds at casting calls and booking work on stage and screen. A stated desire to create “my own opportunities” led him to Calif., where he co-founded a theater. Then he earned a master of fine arts degree at the University of Alabama, where he started another theater.

He soon established himself a director and acting coach. Once fully committed to following his own creative instincts, his original one-man play, Rattlesnake, emerged.

“You know how it is, you come to things when you come to them,” Hardy says. “Freedom explains all good things I get. Man, there’s nothing like liberation.”

In casting around for another one-man play, he returned to his old friends, Dickens and Christmas Carol.

“As much as I had done it, I always felt like there was something else there. I wasn’t quite sure what it was. But there’s a reason why that play is done and why that book’s become a play and become so many movies. I feel like people were searching for it, just as I was, too.

“The other thing is it had a built-in commercial appeal. People have heard of it, it’s known.”

Tried and true is fine, but Hardy imagined a fresh take on the classic.

“I’ve seen one-man versions, but they’re nothing like the one I do. The one I do is not storytelling, it’s not described. Mine is dramatic theater, It’s characters fully involved in this world, this existence from moment to moment. I’ve never seen that in a one-man Christmas Carol. In the others, there’s always a separation – it’s storytelling with a hint of characterization here and there. Whereas mine is moment to moment characters living through this world, which makes it distinctly different.”

The more Hardy dug into the book and play, the more he discovered.

“A Christmas Carol must have a universal thing in it because it never dies and therefore there must be some very human thing that most of us can see in it and relate to in it.”

He believes Dickens possessed insights rare even among great authors or dramatists in exploring the experiences that shape us, such as the transformative powers of forgiveness, humility and gratitude.

“It’s a thrill to have anything to do with Dickens or talk about him. Dickens is just one of those people like Shakespeare that seems to have a window into the human experience that few people have. The more we get to know about ourselves through his work then the closer we get to not killing ourselves and I would like to participate in that endeavor,” he says.

“The psychology of the human being – that seems to be what he has an insight into in a way that is almost never if ever spoken. In other words, what he does is allow characters to engage in living from moment to moment and doesn’t necessarily draw conclusions about it. He doesn’t explain their behavior, he allows them to live.”

That approach works well for Hardy, who abides by the axiom that “you only really come to know a character when they’re engaged in doing something – forget about someone describing them or they describing themselves.” And therein lies the key I think to A Christmas Carol,” he adds.. “It’s not an accident this story has been made into a play and a movie again and again because it’s so active. Somebody’s engaged in doing something. It’s on its way somewhere a hundred percent of the time. It’s never static. It’s not reflective. It moves past a moment into the next moment and you can’t stop and think about it.”

“Even as a book it doesn’t have that page-long description of reaching for a door handle and turning it and that kind of thing. It’s in the room, it’s taking in the room, it’s dealing with what’s in the room and going into the next room. It never stops moving forward. It really doesn’t take a breath. It lends itself to the dramatic universe as opposed to the prosaic. It’s a series of actions characters do – and that reveals them.”

In his one-man show Hardy is our avatar embedded in the story. He embodies the entire gallery of characters immersed in this fable of redemption. As he moves from one characterization to the next, he seductively pulls us inside to intimately experience with him-them the despair, tragedy, fright, frivolity, inspiration and joy.

“Seeing a person move through that whole thing is even more human,” he says. ‘We see ourselves passing through it as this one human being passing through it. Maybe we are everyone in A Christmas Carol –Scrooge, Jacob Marley, Bob Cratchit – and Scrooge is everyone, too.”

Because this is Hardy’s vision of Carol, he can play the omnipresent God who let’s us see and hear things not in the original text.

“I get to do things the book and the plays don’t get to do. For instance, in the book I think Tiny Tim says one thing – ‘God bless us everyone.’ He says it a couple of times. Well, I get to have Tiny Tim say whatever I want him to say. In the book Bob Cratchit explains to his wife what Tiny Tim said when he was carrying him home from church on Christmas morning but I get to have Tiny Tim actually say that. I get to have him actually experience these things and you get to see him live a little more. That’s the kind of thing I can do.”

Hardy’s well aware he’s doing the show in a place with a special relationship to the Dickens drama. The Omaha Community Playhouse production of Charles Jones’ musical adaptation is a perennial sell-out here and in cities across America where the Nebraska Theatre Caravan tours it. Hardy auditioned for the Caravan himself one year.

“It seems like half of everyone I know in the business has had something to do with the Nebraska Theatre Caravan or with the Playhouse or A Christmas Carol. It’s kind of like six degrees of separation – you’re not far away from knowing someone who knows someone who was in that.”

As for his own relationship to Carol, he says, “I’ve been with that story for a long time.”

His one-man homage kicks off “Dickens at the Castle” on November 14 at 6:30 p.m. A pre-show panel of local theater artists, plus Hardy, will discuss adapting the novel. For dates-times of Hardy’s other performances of Carol during the fest and for more event details, visit http://joslyncastle.com/.

For a man whose vocation as a priest is a half-century long and counting, it may come as a surprise that Father Ken Vavrina had no notion of entering that life until, at age 18, a voice instructed him to attend seminary school. It was a classic calling from on high that he didn’t particularly want or appreciate. He had his life planned out, after all, and it didn’t include the priesthood. He resisted the very thought of it. He rationalized why it wasn’t right for him. He wished the admonition would go away. But it just wouldn’t. He couldn’t ignore it. He couldn’t shake it. Deep inside he knew the truth and rightness of it even though it seemed like a strange imposition. In the end, of course, he obeyed and followed the path ordained for him. His rich life serving others has seen him minister to Native Americans on reservations, African-Americans in Omaha’s inner city, occupying protestors at Wounded Knee, lepers in Yemen. the poor, hungry and homeless in Calcutta, India and war refugees in Liberia. He worked for Mother Teresa and for Catholic Relief Services. He’s been active in Omaha Together One Community. There have been many other stops as well, including Italy, Cuba, New York City and rural Nebraska. He has crossed many cultural and geographic bridges to engage people where they are at and to respond to their needs for food, water, medicine, shelter, education, counseling. Everywhere he’s gone he’s gained far more from those he served than he’s given them and as a result he’s grown personally and spiritually. He has attained great humility and gratitude. His simple life of service to others has much to teach us and that’s why he commissioned me to help him write the new book, Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden. It was a privilege to share his remarkable life and story in book form. Here is an article I’ve written about him and his many travels. It is the cover story in the November 2015 issue of the New Horizons. I hope, as he does, that this story as well as the book we did together that this story is drawn from inspires you to cross your own bridges into different cultures and experiences. Many blessings await.

The book is available at http://www.upliftingpublishing.com/ as well as on Amazon and BarnesandNoble.com and for Kindle. The Bookworm is exclusively carrying “Crossing Bridges” among local bookstores.

Father Ken with Mother Teresa

Father Ken Vavrina’s new book “Crossing Bridges” charts his life serving others

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the November 2015 issue of the New Horizons

NOTE:

My profile of Father Ken Vavrina contains excerpts and photos from the new book I did with him, Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden.

A Life of Service

Retired Catholic priest Father Kenneth Vavrina, 80, has never made an enemy in his epic travels serving people and opposing injustice.

“I have never met a stranger. Everyone I meet is my friend,” declares Vavrina, who’s lived and worked in some of the world’s poorest places and most trying circumstances.

It’s no accident he ended up going abroad as a missionary because from childhood he burned with curiosity about what’s on the other side of things – hills, horizons, fences, bridges. His life’s been all about crossing bridges, both the literal and figurative kind. Thus, the title of his new book, Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden, his personal chronicle of repeatedly venturing across borders ministering to people. His willingness to go where people are in need, whether near or far, and no matter how unfamiliar or forbidding the location, has been his life’s recurring theme.

For most of his 50-plus years as a priest he’s helped underserved populations, some in outstate Neb., some in Omaha, and for a long time in developing nations overseas. Whether pastoring in a parish or doing missionary work in the field, he’s never looked back, only forward, led by his insistent conscience, open heart and boy-like sense of wanderlust. That conscience has put him at odds with his religious superiors in the Omaha Catholic Archdiocese on those occasions when he’s publicly disagreed with Church positions on social issues. His tendency to speak his mind and to criticize the Catholic hierarchy he’s sworn to obey has led to official reprimands and suspensions.

But no one questions his dedication to the priesthood. Always putting his faith in action, he shepherds people wherever he lays his head. He lived five years in a mud hut minus indoor plumbing and electricity tending to lepers in Yemen. He became well acquainted with the slums of Calcutta, India while working there. He spent nights in the African bush escorting supplies. He spent two nights in a trench under fire. The archdiocesan priest served Native Americans on reservations and African-Americans in Omaha’s poorest neighborhoods. He befriended members of the American Indian Movement, Black Panthers and various activists, organizers, elected officials and civic leaders.

His work abroad put him on intimate terms with Blessed Mother Teresa, now in line for sainthood. and made him a friend of convenience of deposed Liberia, Africa dictator Charles Taylor, now imprisoned for war crimes. As a Catholic Relief Services program director he served earthquake victims in Italy, the poorest of the poor in India, Bangladesh and Nepal and refugees of civil war in Liberia.

He found himself in some tight spots and compromising positions along the way. He ran supplies to embattled activists during the Siege at Wounded Knee. He was arrested and jailed in Yemen before being expelled from the country. He faced-off with trigger-happy rebels leading supply missions via truck, train and ship in Liberia and dealt with warlords who had no respect for human life.

If his book has a message it’s that anyone can make a difference, whether right at home or half way around the globe, if you’re intentional and humble enough to let go and let God.

“There is nothing remarkable about me…yet I have been blessed to lead a most fulfilling life…The nature of my work has taken me to some fascinating places around the world and introduced me to the full spectrum of humanity, good and bad.

“Stripping away the encumbrances of things and titles is truly liberating because then it is just you and the person beside you or in front of you. There is nothing more to hide behind. That is when two human hearts truly connect.”

Even though he’s retired and no longer puts himself in harm’s way, he remains quite active. He comforts and anoints the sick, he administers communion, he celebrates Mass and he volunteers at St. Benedict the Moor. Occasional bouts of the malaria he picked up overseas are reminders of his years abroad. So is the frozen shoulder he inherited after a botched surgery in Mexico. His shaved head is also an emblem from extended stays in hot climates, where to keep cool he took to buzz cuts he maintains to this day. Then there’s his simple, vegan diet that mirrors the way he ate in Third World nations.

This tough old goat recently survived a bout with cancer. A malignant tumor in his bladder was surgically removed and after recouping in the hospital he returned home. The cancer’s not reappeared but he has battled a postoperative bladder infection and gout. Ask him how he’s doing and he might volunteer, “I’m not getting around too well these days” but he usually leaves it at, “I’m OK.” He lives at the John Vianney independent living community for retired clergy and lay seniors. He’s more spry than many residents. It’s safe to say he’s visited places they’ve never ventured to.

Father Ken today

Roots

Born in Bruno and raised in Clarkson, Neb., both Czech communities in Neb.’s Bohemian Alps, Vavrina and his older brother Ron were raised by their public school teacher mother after their father died in an accident when they were small. The boys and their mother moved in with their paternal grandparents and an uncle, Joe, who owned a local farm implement business and car dealership. The uncle took the family on road trip vacations. Once, on the way back from Calif. by way of the American southwest, Vavrina engaged in an exchange with his mother that profoundly influenced him.

“I remember my mom telling me, “On the other side of that bridge is Mexico,” and right then and there I vowed, ‘One day I’m going to cross that bridge'”

“I never crossed that particular bridge but I did cross a lot of bridges to a lot of different lifestyles and countries and cultures and it was a great, great, great blessing. You learn so much in working with people who are different.”

One key lesson he learned is that despite our many differences, we’re all the same.

Even though he grew up around very little diversity, he was taught to accept all people, regardless of race or ethnicity. He feels that lesson helped him acclimate to foreign cultures and to living and working with people of color whose ways differed from his.

As a fatherless child of the Great Depression and with rationing on due to the Second World War, Vavrina knew something about hardship but it was mostly a good life. Growing up, he went hunting and fishing with his uncle, whose shop he worked in. He played organized basketball and baseball for an early mentor, coach Milo Blecha.

“All in all, I had a wonderful childhood in Clarkson,” he writes. “It was a simple life. The Church was dominant. There was a Catholic church and a Presbyterian church. Father Kubesh was the pastor at Saints Cyril and Methodius Catholic Church. When he was not saying Mass, Father Kubesh always had a cigar in his mouth. I served Mass as an altar boy. Little did I imagine that he would counsel me when I embarked on studying for the priesthood.”

All through high school Vavrina dated the same girl. His family wasn’t particularly religious and he never even entertained the possibility of the priesthood until he felt the calling at 18. Out of nowhere, he says, the thought, really more like an admonition, formed in his head.

“I was driving a pickup truck on a Saturday morning, about four miles east of Clarkson, when something happened that is still crystal clear to me. I distinctly heard a voice say, ‘Why don’t you go to the seminary?’ Just like that, out of the blue. I thought, This is crazy.“Was it God’s voice?

“Being a priest is a calling, and I guess maybe it was the call that I felt then and there. If you want to give it a name or try to explain it, then God called me to serve at that moment. He planted the seed of that idea in my head, and He placed the spark of that desire in my heart.”

The very idea threw Vavrina for a loop. After all, he had prospects. He expected to marry his sweetheart and to either go into the family business or study law at Creighton University. The priesthood didn’t jibe with any of that.

He says when he told Father Kubesh about what happened the priest’s first reaction was, “Huh?” For a long time Vavrina didn’t tell anyone else but when it became evident it wasn’t some passing fancy he let his friends and family know. No one, not even himself, could be sure yet how serious his conviction was, which is why he only pledged to give it one year at Conception Seminary College in northwest Missouri.

He told his uncle, I’ll give it a shot.” And so he did. One year turned into two, two years turned into three, and so on, and though his studies were demanding he found he enjoyed academics.

He finished up at St. Paul Seminary at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn. and was ordained in 1962.

Calling all cultures

His introduction to new cultures began with his very first assignment, as associate pastor for the Winnebago and Macy reservations in far northern Nebraska. Vavrina was struck by the people’s warmth and sincerity and by the disproportionate numbers living in poverty and afflicted with alcoholism. He disapproved of efforts by the Church to try and strip children of their Native American ways, even sending kids off to live with white families in the summer.

His next assignment brought him to Sacred Heart parish in predominantly black northeast Omaha. He arrived at the height of racial tension during the late 1960s civil rights struggle. He served on an inner city ministerial team that tried getting a handle on black issues. When riots erupted he was there on the street trying to calm a volatile situation. The more he learned about the inequalities facing that community, the more sympathetic he became to both the civil rights and Black Power movements, so much so, he says, people took to calling him “the blackest cat in the alley.”

He was an ally of Nebraska state Sen. Ernie Chambers, activist Charlie Washington and Omaha Star publisher Mildred Brown. He befriended Black Panthers David Rice and Ed Poindexter (Mondo we Langa), both convicted in the homemade bomb death of Omaha police officer Larry Minard. The two men have always maintained their innocence..

Vavrina welcomed changes ushered in by Vatican II to make the Church more accessible. He criticized what he saw as ultra-conservative and misguided stands on social issues. For example, he opposed official Catholic positions excluding divorced and gay Catholics and forbidding priests from marrying and barring women being ordained. He began a long tradition of writing letters to the editor to express his views. He’s never stopped advocating for these things.

He next served at north downtown Holy Family parish, where his good friend, kindred spirit and fellow “troublemaker” Jack McCaslin pastored. McCaslin spouted progressive views from the pulpit and became a peace activist protesting the military-industrial complex, which resulted in him being arrested many times. The two liberals were a good fit for Holy Family’s open-minded congregation.

Then, in 1973, Vavrina’s life intersected with history. Lorelei Decora, an enrolled member of the Winnebago tribe, Thunder Bird Clan, called to ask him to deliver medical supplies to her and fellow American Indian Movement activists at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. A group of Indians agitating for change occupied the town. Authorities surrounded them. The siege carried huge symbolic implications given its location was the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. Vavrina knew Decora when she was precocious child. Now she was a militant teen prevailing on him to ride into an armed standoff. He never hesitated. He and a friend Joe Yellow Thunder, an Oglala Sioux, rounded up supplies from doctors at St. Joseph Hospital. They drove to the siege and Father Ken talked his way inside past encamped U.S, marshals.

He met with AIM leader and cofounder Dennis Banks, whom he knew from before.

“Then I saw Lorelei and I looked her in the eye and asked, ‘What are you doing here?’ She said with great conviction, ‘I came to die.’ They really thought they would all be killed. They were fully committed…On his walkie-talkie Banks reached the authorities and told them, ‘Let this guy stay here. He’s objective. He’ll let you know what’s going on.’ The authorities went along…that’s how I came to spend two nights at the compound. We bivouacked in a ravine where the Indians had carved out trenches. We used straw and blankets over our coats, plus body heat, to keep warm at night. It was not much below freezing, and there was little snow on the ground, which made the camp bearable.“At night the shooting would commence…the tracers going overhead, the Indians huddled for cover, and several of the occupiers sick with cold and flu symptoms.

“Once back home, Joe and I attempted to make a second medicine supply run up there. We drove all the way to the rim but were turned back by the marshals because the violence had started up again and had actually escalated. When the siege finally ended that spring, there were many arrests and a whole slew of charges filed against the protesters.”

By the late-’70s Vavrina was serving a northeast Neb. parish and feeling restless. He’d given his all to combatting racism and advocating for equal rights but was disappointed more transformational change didn’t occur. He saw many priests abandon their vows and the Church regress into conservatism after the promise of Vatican II reforms. More than anything though, he felt too removed from the world of want. It bothered him he’d never really put himself on the line by giving up things for a greater good or surrendering his ego to a life of servitude.

“I felt I was out of the mainstream, away from the action. Plus, I knew the civil rights movement was…not going to reach what I thought it could achieve…So I decided I was going overseas. I wanted to be where I could do the greatest good. I always felt drawn to the missions…I just felt a need to experience voluntary poverty and to become nothing in a foreign land.“…an experience in Thailand changed the whole trajectory of my missions plan. I was walking the streets of Bangkok…on the edge of downtown…Then I made a wrong turn and suddenly found myself in the slums of Bangkok…everywhere I looked was human want and suffering at a scale I was unprepared for.

“I was shocked and appalled by the conditions people lived in. I realized there were slums all over the world and these people needed help. What was I doing about it? The experience really hit me in the face and marked an abrupt change in my thinking. I looked at my relative affluence and comfortable existence, and I suddenly saw the hypocrisy in my life. I resolved then and there, I was going to change, and I was going to move away from the privilege I enjoy, and I would work with the poor.”

A reinforcing influence was Mother Teresa, whom he admired for leaving behind her own privilege and possessions to tend to the poor and sick and dying. He resolved to offer himself in service to her work.

The nun, he writes, “was a great inspiration..” Nothing could shake his conviction to go follow a radically different path and calling.

His going away had nothing to do with escaping the past but everything to do with following a new course and passion. By that time he’s already worked 15 years in the archdiocese and “loved every minute of it.” He was finishing up a master’s degree in counseling at Creighton University. “Everything was good. No nagging doubts. But I just felt compelled to do more,” he writes.

He asked and received permission from the diocese to work overseas for one year and that single year, he describes, turned into 19 “incredible years helping the poorest of the poor.”

Yemen

He no sooner found Mother Teresa in Italy than she asked him to go to Yemen, an Arab country in southwest Asia, to work with residents of the leper village City of Light.

“I simply replied, ‘Sure,’” Vavrina notes in his book.

In Yemen he witnessed the fear and superstition that’s caused lepers to be treated as outcasts everywhere. In that community he worked alongside Missionaries of Charity as well as lepers.

“My primary job was to scrape dead skin off patients using a knife or blade. It was done very crudely. Lepers, whether they are active or negative cases, have a problem of rotting skin. That putrid skin has to be removed for the affected area to heal and to prevent infection…I would then clean the skin.“I would also keep track of the lepers and where they were with their treatment and the medicines they needed.”

He embraced the spartan lifestyle and shopping at the local souk. He found time to hike up Mount Kilimanjaro. He also saw harsh things. An alleged rapist was stoned to death and the body displayed at the gate of the market. Girls were compelled to enter arranged marriages, forbidden from getting an education or job, and generally treated as property. Yemen is also where he contracted malaria and endured the first sweats and fevers that accompany it.

Yet, he says, Yemen was the place he found the most contentment. Then, without warning, his world turned upside down when he found himself the target of Yemeni authorities. They took him in for seemingly routine questioning that turned into several nights of pointed interrogation. He was released, but under house arrest, only to be detained again, this time in an overcrowded communal jail cell.

He was incarcerated nearly two weeks before the U.S. embassy arranged his release. No formal charges were brought against him. The police insinuated proselytizing, which he flatly denied, though he sensed they actually suspected him of spying. They couldn’t believe a healthy, middle-aged American male would choose to work with lepers.

His release was conditional on him immediately leaving the country. The expulsion hurt his soul.

“Being kicked out of the country, and for nothing mind you, other than blind suspicion, was not the way I imagined myself departing. I was disappointed. I truly believe that if I had been left to do my work in peace, I would still be there because I enjoyed every minute of working with the lepers. There is so much need in a place like Yemen, and while I could help only a few people, I did help them. It was taxing but fulfilling work.”

India

He traveled to Italy, where Catholic Relief Services hired him to manage a program rebuilding an earthquake ravaged area. Then CRS sent him to supervise aid programs in India. After nine months in Cochin he was transferred to Calcutta. Everywhere he set foot, hunger prevailed, with millions barely getting by on a bare subsistence level and life a daily survival test.

Besides supplying food, the programs taught farmers better agricultural practices and enlisted women in the micro loan program Grameen Bank. In all, he directed $38 million in aid annually.

The generous spirit of people to share what little they have with others impressed him. Seeing so many precariously straddle life and death, with many mothers and children not making it, opened his eyes. So did the sheer scale of want there.

“I will never forget my first night in Calcutta. I said to the driver, ‘What are in these sacks we keep passing by?’ ‘Those are people.’ Hundreds upon thousands of people made their beds and homes alongside the road. It was a scale of homelessness I could not fathom. That was my introduction to Calcutta.“I was scared of Calcutta. Of the push and pull and crunch of the staggering numbers of people. Of the absurd overcrowding in the neighborhoods and streets. Of the overwhelming, mind-numbing, heartbreaking, soul-hurting poverty. That mass of needy humanity makes for a powerful, sobering, jarring reality that assaults all the senses…

“…only God knows the true size of the population…I often say to religious and lay people alike, ‘Go to Calcutta and walk the streets for six days and it will change your life forever” Walk the streets there for one day and even one hour, and it will change you. I know it did me.”

Vavrina was reunited there with Mother Teresa.

“I spent a lot of time working with Mother, Whenever she had a problem she would come into the office. If there was a natural disaster where her Sisters worked we would always help with food or whatever they needed.”

He witnessed people’s adoration of Mother Teresa wherever she went. There was enough mutual respect between this American priest and Macedonian nun that they could speak candidly and laugh freely in each other’s company. He criticized her refusal to let her Sisters do the type of development work his programs did. He disapproved of how tough she was with her Sisters, whom she demanded live in poverty and restrict themselves to providing comfort care to the sick and dying.

He writes, “I disagreed with Mother and I told her so. I knew the value of development work. Our CRS programs in India were proof of its effectiveness…she listened to me, not necessarily agreeing with me at all…and then went right ahead and did her own thing anyway…I cried the day I left Calcutta in 1991. I loved Calcutta. Mother Teresa had tears in her eyes as well. We had become very good friends. She was the real deal…hands on…not afraid to get her hands dirty.”

Years later he read with dismay and sadness how she experienced the Dark Night of the Soul – suffering an inconsolable crisis of faith.