A KVNO Radio studio in the early days at the Storz mansion, ©photo UNO Criss Library

A KVNO Radio studio in the early days at the Storz mansion, ©photo UNO Criss Library

Sometimes it’s easy to assume that academics are cloistered away in their ivy towers, isolated from the real world. That’s certainly not the case with Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado. The University of Nebraska at Omaha political science professor does his share of research but much of it takes him out of his office, off campus, and out into mainstream of life, whether to the barrios of South Omaha or Cuba, where he’s traveled many times for his research. I was reminded to post this profile of him I wrote a couple years ago after reading a piece in the local daily about his latest trip to Cuba, this time leading a group of UNO students to help restore a theater there that he hopes becomes a conduit for future arts-cultural exhanges. In his work he’s just as likely to meet with folks just trying to get by as he is with U.S. and Cuban diplomats and leaders. He’s even met Castro.

Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado

UNO/OLLAS resident expert on Cuban and Latino matters Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

For author, researcher, activist and University of Nebraska at Omaha associate professor of political science Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado, political engagement is a birthright.

His mother Romelia marched with Cesar Chavez in the California migrant labor movement. Both his parents know first hand the migrant worker struggle. They also know the empowering change hard work and opportunity can bring.

Benjamin-Alvarado still marvels how his folks made “a hyper speed transition” from their vagabond life hand-picking crops wherever the next harvest was to achieving the American Dream within 20 years. “The day I was born my dad was picking lettuce and the day I graduated from high school he owned his own business and we lived in a really nice house in the suburbs.”

From his mother, who worked on behalf of women’s and Latino rights and as a political campaign volunteer, he learned activism. From his father he learned ambition and determination. As someone who grew up in The Burbs, never having to toil in the fields, Benjamin-Alvarado fully realizes how charmed he’s been to have role models like these.

“To this very day I’m reminded of the lessons and examples presented before me. These were people who prided themselves on what they did. They were people with an incredible sense of dignity and self respect,” he said. “I think what makes things like Cesar Chavez (or his mother) happen is they’re not willing to cede that one iota. They made it very clear that your abuse and subjugation of me will not define me.

“I shutter to think what my forbearers could have done had they had the opportunities I’ve been extended, especially given the incredible work ethic they had. They had no choice but to work hard. It’s only as I’ve gotten older I’ve realized what an incredible legacy and, in turn, responsibility I have to pay it forward. I’m very fortunate to have been able to live and travel all over the world and to be educated in incredible places. My whole thing now is what can I do to make sure others have these opportunities. I really do cherish what I have been granted and I feel an overriding sense of obligation.”

Despite comforts, life at home for he and his brother was unpleasant. Their father was an abusive partner to their mother. The siblings were also misfits in mostly Anglo schools and neighborhoods. To escape, the boys read voraciously. “That was our refuge from all the craziness in our lives. We were really just sponges,” said Jonathan. He did well in school and was enrolled in college when he abruptly left to join the U.S. Navy.

“I think everybody in my family was aghast but i really did it more for purposes of self-preservation and to establish some independence for myself. I needed to leave.”

His 1976-1980 Naval tour fit the bill.

“For me it was just four years of incredible discovery,” he said. “I met for the first time blacks from the northeast and Chicago, kids from the South and the Midwest, other Latinos. All of that was very interesting to me. I came to appreciate them and their cultures in ways I couldn’t possibly have done so had I stayed sequestered in California, where it’s very insular and you think the world revolves around you.”

Back home he used the G.I. bill to attend ucla, where he said he went from doubting whether he belonged to believing “I’m competitive with the cream of the crop. That realization stunned me. There was no limit at that point. I was in a different world.”

Then an incident he doesn’t like discussing occurred. It took five years to recover from physical and emotional wounds. He eventually earned his bachelor’s degree and did stints at Stanford and Harvard. He earned his master’s at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. While working at its think tank, the Center for Nonproliferation Studies, he began intensive research on Cuba. He’s traveled there 25 times, often spending months per visit. Cuba remains a major focus of his professional activity.

Recruited by the Central Intelligence Agency, he seriously entertained doing clandestine work before deciding he didn’t want to give up his academic freedom. Besides, he said, “I don’t and won’t keep secrets because it gets you into trouble.” Already married and with a child, he opted to complete his doctoral studies at the University of Georgia. He landed major grants for his Cuban research. Along the way he’s become a recognized expert on Cuban energy and foreign policy, authoring one book and editing another on that nation’s energy profile and what it bodes for future cooperation with the West.

A temporary teaching post at Georgia then set him on a new track.

“I had not given the idea of being a classroom instructor much thought prior to that,” he said. “I thought I was going to spend my life as a senior researcher — a wonk. But I got this bug (to teach). I realized almost immediately I like doing this, they like me, this is a good gig. It didn’t feel like I had to work real hard to do it, a lot of it just came naturally, and I had this reservoir to draw on.”

When grant funding dried up he sought a full-time teaching job and picked UNO over several offers, in part for it’s dynamic growth and emerging Latino community. He’s been at UNO 10 years. His Cuba work has continued but in a different way.

Then the U.S. banned academic trips there. His last few visits he’s “been part of high level delegations with former Pentagon and State Department staff. This last one (in November) was with former U.N. Ambassador Thomas Pickering.” In 2006 he met with senior government officials, including Fidel Castro, Raoul Castro, the president of the national assembly and ministers of other government bureaucracies. On these visits he’s there as “technical advisor-resident expert” for debriefings, analysis and reading beyond the rhetoric to decipher what’s really being said through interpreters.

He believes normalized relations only make sense for two nations with such an affinity for each other. Once restrictions are lifted he envisions a Cuban trip with area public and private sector leaders. He and a colleague plan to convene an international conference in Havana, of university presidents from North and South America “to discuss the trajectory of higher education in the 21st century for the Americas.”

His connections helped broker a deal for Nebraska selling ag products to Cuba. Closer to home, he advises government on Latino matters and is active in the Democratic Party. He’d like to see more Latinos active in local politics. A recipient of UNO’s Outstanding Teacher Award, he said the Office of Latino/Latin American Studies at UNO “has been a godsend for me. OLLAS has been central to helping me live out what I do in my community. There’s an element of it that is very personal. When we founded OLLAS we intentionally created something that would have a community base and make the community a part of what we do. We want our work to be not only politically but socially relevant. That’s been the basis for the outreach projects we’ve undertaken.”

Recent projects include reports on immigration and Latino voter mobilization.

I am not normally crazy about covering events because I think of myself more as a writer than a reporter. While spending several hours at an academic and community confab I was assigned to report on is not my idea of a good time I did mostly enjoy covering the 2010 Cumbre conference put on by the Office of Latino and Latin American Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The big topic under discussion was human mobility or migration and the political, social, economic, and personal fallout of populations in flux. It’s interesting how things work because a year or so after the event I became aware of a great book about one of the most important and underdoumented migration experiences in U.S. history – the great migration of African-Americans from the South to all points North and West. The book by Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, is one I eventually read and wrote about, interviewing Wilkerson at some length, then meeting her before a talk she gave in Omaha. And that sparked my beginning to do research for a story or series of stories on African-Americans who migrated from the South to Nebraska. I’ll write that story next year in conjunction with the big black heritage celebration here known as Native Omaha Days. And I was to have undertaken a rather epic project all about human migration for a Catholic community of missionaries but it has been put on hold. Finally, I may be making an individual and temporary migration this fall reporting on set of Alexander Payne’s upcoming feature production Nebraska, which would find me embedding myself among the crew as they traverse from eastern Montana across much of Nebraska for the making of this road movie. So, you see, in the midst of overcoming my reluctance to cover a migration conference I found myself open to a pattern of migration subjects and opportunities that came my way. Would they have otherwise? Who knows? I’m just glad they did.

Cumbre:

Hundreds attend OLLAS conference

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in El Perico

A wide spectrum of Latino concerns, including the need for federal immigration reform, swirled around the May 14-15 Cumbre conference held at Omaha‘s Embassy Suites in the Old Market. The theme was Human Mobility, the Promise of Development and Political Engagement.

The every-few-years summit hosted by UNO’s Office of Latino and Latin American Studies is part I’ll-show-you-mine, if-you-show-me-yours research exchange, part old-fashioned networking event and part open mic forum.

More than 400 registrants from near and far came to share ideas. The perspectives ranged from star academics allied with major institutions to local grassroots organizers.

Adding urgency was the divisive new Arizona law targeting illegal immigrants. OLLAS director Lourdes Gouveia said when planning for this year’s summit began four years ago immigration was a hot topic. It was expected to remain so once Barack Obama won the White House, but the health care debate put it on the back burner.

“We began to think well maybe this was not the year when the national context about immigration was really going to provide the impetus,” she said, “and then along comes Arizona. All at once we had people like Jason Marczak (policy director with Americas Society/Council of the Americas) call and say, ‘I’d like to come, is it too late?’ We had vans of people coming from Colorado and Iowa. We had people showing up from all kinds of communities in the Great Plains, besides all the international scholars from Africa, India, Latin America, Europe.”

Omaha Mayor Jim Suttle and State Sen. Brenda Council kicked off the event. State Sen. Brad Ashford was a panelist and Omaha City Councilman Ben Gray served as a moderator.

Beyond facilitating dialogue, Cumbre introduces new scholarship. Coordinators for the Woodrow Wilson Center Mexico Institute’s Latino Immigrant Civic Engagement Project chose Cumbre to unveil their report’s findings of Latino civic involvement in nine U.S. cities, including Omaha. The authors tied engagement levels to several factors. Generally, the more engaged immigrants are with their country of origin, the more engaged they are in their adopted homeland. High participation in church activities correlates with high participation in civic activities. Coalitions, whether community, church or work-based, such as the Heartland Workers Center in Omaha, act as gateways for increased engagement.

But each Latino immigrant community has its own dynamics that influence participation, thus authors titled their report “Context Matters.” Co-author Xochitl Bada, a University of Illinois at Chicago assistant professor, presented the findings.

OLLAS issued its own site report, “Migrant Civil Society Under Construction.” Investigators conducted roundtable discussions with local Latino immigrants, who said that fear, inadequate education and lack of information are barriers to engagement.

Bada said Omaha is rather unique in being both a new and old destination for Latino migration, a mix that may partly account for the moderate levels of civic-political participation by the emerging Latino immigrant community here.

Respondents in all nine cities regarded the 2006 immigration mobilization marches as a turning point in Latino engagement but expressed disappointment the movement did not sustain itself.

Among other panels: UNO economist Christopher Decker outlined Latino immigrants’ substantial economic impact in state; and UNO languages professor Claudia Garcia detailed a project delivering education programs and restoring family connections to local Spanish-speaking immigrant prison detainees.

Cumbre’s hallmark is gathering under one roof different players. Speeches, panels, workshops, town hall meetings, Q & As and breakout sessions provide opportunities for these wonks, worker bees, policymakers and service providers to interact.

Princeton University scholar and Center for Migration and Development director Alejandro Portes has attended all four Cumbres. The Cuba native said he made his 2010 keynote address on Latino immigrant transnationalism accessible to Cumbre’s diverse audience. The Creighton University graduate said, “I think bringing the community and the scholars in the same room is one of the things I like about it. The organizers have great talent in bringing these different constituencies together.”

Another featured speaker, journalist, author and University of Southern California communication professor Roberto Suro, said what distinguishes Cumbre is “it attracts really A-list, blue-ribbon people from the academic world and at the same time a very broad swath of people who work on the ground. It’s the only conference I know of that does that. There’s a reason the room’s full.”

In his address Suro spoke about “reimagining” Latino migration policies in both the sending Central and Latin American countries and in the receiving United States.

“Through gatherings like this,” Suro said, “what you see is people broadening the horizons of policy discussion and starting to think about reformulating issues, adding to the agenda and starting to develop the kind of understandings and intellectual framework that might permit better policy in the future.”

Suro told the audience that researchers and activists like them are well ahead of policymakers and politicians on the issue and give him reason for optimism.

OLLAS assistant director Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado said some of what happens at Cumbre “is bound to be carried” to global forums,” adding, “and that to me is probably the highest compliment for what we try to do in bringing all these people together.”

Xochitl Bada, co-principal investigator of the Latino immigration Civic Engagement Project, said Cumbre “has a very important public aspect. Unlike most academic conferences, it’s conceived “as a report back to the community.” She said the fact the summit is free makes it inclusive. “That’s very unusual.” She said another mark of Cumbre’s open door approach is the simultaneous translation, from Spanish to English and from English to Spanish, it provides to ensure that “language is not a barrier.” She called Cumbre an important vehicle for “public discourse” and “public dissemination.”

Rev. Ernesto Medina, pastor of St. Martha Episcopal Church in Omaha, moderated a panel discussion on human rights, work and community membership. He said he appreciates the opportunity Cumbre presents “to see things holistically” and to put “different communities and different passions” in the same room to find common ground.

Though many differing views were voiced, some consensus emerged: immigration reform must happen but the current partisan climate makes it unlikely soon; criminalization of migrants is punitive, narrow-minded, counterproductive and damaging to families; today’s nativist anti-immigration arguments echo those of the past; lawmakers need good data about immigration to make good policy; Latino immigrants can be fully engaged in both their country of origin and American society; remittances made by Latino migrants to their native countries are crucial to those economies.

Roberto Suro said the full contributions of the recent Latino migrant wave can only be weighed when second generation children reach adulthood. He advocates Latino immigrants be viewed as more than merely a subsistence labor force.

National Alliance of Latin American and Caribbean Countries executive director Oscar Chacon called for more “robust” organizations like his that represent Latino immigrant interests and celebrate their cultural differences while working toward “common cause.”

Alejandro Portes warned if the rhetoric and actions of anti-migrant forces continue “it could usher in ethnic unrest, and there’s absolutely no reason for that. I don’t think it will get that bad because of Obama in the White House and the federal government at some point is going to enter the situation and bring some kind of immigration reform.”

For a long time and even today the University of Nebraska at Omaha was best known for its large Bootstrapper program for military personnel. The school is vastly different than it was when the program launched during the Cold War but it’s impact remains. The following story from a half-dozen years ago or more is about an original play written by the Omaha husband and wife team of Mark Manhart and Bonnie Gill that takes a nostalgic look at the program’s beginnings, and those beginnings involved two strong leaders, then-Omaha University president Milo Bail and Strategic Air Command head and hawk of hawks Gen. Curtis LeMay, who some suggest was the inspiration for the character of Gen. Buck Turgidson that George C. Scott plays in Dr. Strangelove. A Midwest academic and a military reactionary may seem to have made strange bedfellows but then again it’s not hard to imagine that two powerful middle-aged white men should come together in right wing solidarity “for the boys.”

Homage to the bootstrappers by the Grande Olde Players

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The Grande Olde Players Theatre pays homage to Omaha’s deep military ties with the new play Bootstrappers Christmas, now through December 17. Written by the theater’s Mark Manhart and Bonnie Gill, the nostalgic 1954-set piece tells a fictional story amid the trappings of history. The relationship between then-Omaha University and the former Strategic Air Command in Bellevue, Neb. is at the center of this holiday-themed dramadie.

Early in his stint as commander of the newly formed SAC, Gen. Curtis LeMay, architect of U.S. bombing campaigns in Europe and the Pacific and overseer of the Berlin Airlift, identified the need for a more professional corps of college-educated personnel. After World War II the U.S. Air Force had a glut of officers. Many had some college prior to the service and once “on the line” accrued credits at schools near where they were based, but few ever got their degrees.

LeMay, an American hero whose reactionary, right-wing views later tarnished his reputation, broached Operation Bootstrap with his egg-head friend, the late Milo Bail, then-president of what’s now the University of Nebraska at Omaha. By helping commissioned officers finish their degrees, the program would aid their climb up the ladder as well as better prepare them for post-military life. The idea of men and women “lifting themselves by their bootstraps” gave the program its name.

Bail and fellow UNO officials recognized the school was well-poised to serve military folks by virtue of a large adult education unit and Bachelor of General Studies (BGS) program that allowed nontraditional students to individualized studies in subjects of interest or deficiency. “Omaha University was really the first school in the country to offer” the BGS, said William Utley, former UNO College of Continuing Studies dean. More appealing still, he said, were the “earned life credits” granted officers for experience gained in the field, which cut by a semester their degree track.

The school’s extensive night courses offered yet more flexibility. Besides the cache of this partnership, school officials craved the extra money derived from the higher non-resident tuition bootstrappers paid. Between Offutt’s close proximity and Omaha’s central location, the military could feed students there not just from Offutt but from bases all over the U.S. and the world.

That’s what happened, too, as an influx of mostly Air Force but also Army soldiers and Marines made UNO the nation’s largest on-campus education provider for bootstrappers. Officers rotated in on active duty or TDY. Utley, director of the UNO program, said at its 1960s peak 1,200 to 1,500 “boots” attended school there at any one time. “There were any number of commencement exercises when over half of the graduating class was bootstrappers,” he said.

Alumni officials estimate 13,000-plus active duty military personnel attended UNO from the early ‘50s to the ‘80s.

Utley said UNO prided itself on being responsive to officers’ needs and interests by “developing” a system to stay in “constant communication” with them, no matter where their assignments took them. He said both active and prospective students received “counseling and advising” services to facilitate their education.

The presence of so many boots changed the dynamic of the school, especially in those early years, when it was a small, financially strapped municipal university, not yet a part of the University of Nebraska system.

“The Bootstrap Program was a major factor for several years in keeping the university afloat with the revenue” it generated, Utley said. “It was a very important element in the survival of the university during that period, when the university was really hard up.”

UNO Alumni Association President Emeritus Jim Leslie said bootstrappers were “a tremendous boon” to UNO’s finances. For a while, he said, UNO enjoyed a near monopoly in serving the bootstrap population. “It was a big deal,” he said. “For a while we claimed we were second only to West Point in the number of general officers that had graduated from our institution.” Some were stars like Johnnie Wilson, a four-star general. Other schools eventually cut in on the action.

Utley said the infusion of so many “highly motivated” students changed the academic culture at UNO. “They were a very serious group. Very good students,” said Leslie, who had boots as classmates there in the early ‘60s. “They were here to gain an education and most of them were older and more mature. Professors loved those guys because they asked the best questions.”

“A lot of students viewed them as ‘curve busters’ who made it harder to compete in the classroom or set a higher standard in the classroom. And no faculty member is going to complain about that,” said retired UNO professor Warren Francke, who had his share of boots. “And its true in general they were solid students because they were all business. They were there to do well in the classes.

“I thought they were certainly an asset. There were times when probably the undergraduates had a legitimate complaint that maybe they dominated things so much. But mostly,” Francke said, the boots “added a dimension to what” otherwise “was a commuter campus without a lot of people who had been all over the world…I thought their addition was sort of a valuable thing to have.”

While Bootstrappers Christmas is a slight, sentimental romp filled with a mix of ‘50s-era rock and traditional Christmas music, writer-director Mark Manhart does anchor the story in the real symbiosis between UNO and Offutt. The flamboyant Curtis LeMay and the non-nonsense Milo Bail are characters. The plot revolves around a boot who befriends a Cold War widow coed and other students in remodeling the campus Snack Shack in time for putting on a holiday show. The fun is tinged with the sadness of separation and loss, but hope prevails.

The play’s also about making new starts, something the bootstrap program epitomized. Ex-Air Force pilot Jim Hughes spoke for many boots when he said, “The university was the first milestone in my growth with the Air Force and I attribute any success and all successes I’ve had to that little development. I owe a debt of gratitude to the university…It introduced me to education oriented to my needs.”

The Iowa native and current Magnolia, Ark. resident said his general education degree catapulted him “up the ladder.” In 1973 he retired from active duty as a decorated colonel. He earned the Bronze Star, four distinguished Flying Crosses and five Airmedals. He received two Purple Hearts for injuries suffered as a POW.

NOTE: Operation Bootstrap supplanted Operation Midnight Oil. In 2002 the Air Force replaced the Bootstrap Program with the Educational Leave of Absence Program (ELA), although many in the service still refer to it by its old name.

Omaha’s KVNO Classical 90.7 FM turns 40:

Commercial-free public radio station serves the community all classical music and local news

While the commercial radio menu leans to blow-hard hosts and pop heavy rotations, public radio’s soothing sounds and erudite musings cut through the clutter. KVNO 90.7 FM further stands out for its all-classical play lists and original local newscasts.

Music, public affairs, news mix by KVNO for Omaha

The UNO-based independent celebrates 40 years on-air in 2012, an impressive feat considering its niche appeal as a commercial-free operation dependent on donor support for survival. The professionally-staffed station maintains high quality. The news division particularly serves as a real-world training ground for students.

KVNO long ago opted to be the master of its own content.

“KVNO’s programming is indeed unique among independent classical stations across the country,” says general manager and mid-day-midnight host Dana Buckingham. “KVNO has developed our own blend of classical music programming format that works well for us and the market we serve.

“Many traditional classical stations stick to a rigid programming formula that rarely deviates from the standard playbook of the ‘tried and true’ classics. This homogenized classical programming format almost never crosses over into more contemporary classical, vocal or film music. At KVNO we cross that line almost every hour and our listeners love it.”

Michael Hilt, who as UNO Associate Dean for the College of Communication, Fine Arts and Media oversees KVNO, sees value in personally crafting the program day.

“I think more and more you’re seeing stations going to services that provide the music. They may program part of their broadcast day but not all of it. We have a music director who works with the general manager on programming the music 24/7.”

Audience feedback is considered in programming decisions, officials note.

Buckingham says a “renewed commitment” to news and public affairs has netted award-winning results. “I am very proud of the achievements our talented news team has made. News director Robyn Wisch is a true professional and a great resource and mentor for our students.”

He says where KVNO once “sought to distance itself” from the university, “no more,” adding, “We are the broadcasting voice of the University of Nebraska Omaha and proud of it.” Hilt says the station maintains autonomy though. “The university lets us do what we do. Sometimes there are things we do they love and then there are other times when they say,’ Gee, we wish you hadn’t done that.’ Is there any censorship or editorial control? No.”

A new partnership, strengthening local arts ties, staying relevant

In January KVNO embarked on a programming partnership with NET Radio that enables each to serve a larger statewide audience and to introduce listeners to new voices. Expanding KVNO’s reach, says Hilt, “is very important to us.” Buckingham terms it “a win-win.”

Public radio and the arts make a natural fit, thus KVNO, which once branded itself “fine arts public radio” and served as “the voice of the Summer Arts Festival,” is a dedicated arts advocate and programming outlet.

“Our affiliation with the local arts scene is very strong and we are always seeking ways to make these relationships even stronger,” says Buckingham. “We’re exploring the possibility of producing an expanded weekly broadcast series of the Omaha Symphony.” He sees possibilities for the series beyond Omaha. “It is my hope we may eventually offer this expanded series for nationwide distribution. We are also in the process of integrating more classical music selections featuring the Omaha Symphony into our regular daily playlist and rotation.”

KVNO broadcasts the UNO Music Department series “Sounds from Strauss” and Omaha Symphonic Chorus and Tuesday Musical Concert performances. The station recognizes youth musicians through its Classical Kids program. Aside from the performing arts, KVNO does its share of live UNO sports broadcasts.

To remain relevant in this new media age of cable, satellite and the Internet, Buckingham says, “we cannot afford to be just another classical music service provider, we must be connected to our community and involved in promoting and providing a forum for the talented musicians and artists in our community.”

Popular on-air hosts help the station build listener loyalty, an essential facet in such an intimate medium.

“I have been an on-air classical music host on KVNO for over a decade,” he says. “In fact, most of our on-air classical announcers have been here a long-time. Over that time, we have established a connection with our listeners that has helped us through the good times and the not so good times. Many regular listeners have established a ‘relationship’ with our local hosts. We are always that familiar and friendly voice in the morning, afternoon, evening or late at night.”

Doing more with less and reinventing itself

University budget cuts and pinched donor dollars have forced a frugal station to further stretch already thin resources.

“Believe me, we know how to do more with less,” he says. “We do it every day. We furnished our newsroom entirely with computers handed down from other departments on campus and office equipment from university surplus..”

That austerity harkens back to the station’s modest roots. When KVNO first went on the air in 1972 general manager Fritz Leigh was the lone full-time employee. At the start KVNO stayed on-air only a few hours a day, gradually expanding the schedule until reaching a 24-hour broadcast day in 1985. For its first 15 years the station called the Storz mansion home before moving to the Engineering Building in 1987.

A KVNO Radio studio in the early days at the Storz mansion, ©photo UNO Criss Library

A KVNO Radio studio in the early days at the Storz mansion, ©photo UNO Criss Library

When Omaha DJ Otis Twelve became the morning drive host in 2006 it was not the first time a media personality joined KVNO. Local TV-radio personalities Frank Bramhall and Dale Munson did so in the 1970s and 1990s, respectively.

It may surprise listeners KVNO once played an eclectic mix of classical, jazz, rock, big band and folk before going all classical in the ’90s. A show it once produced and distributed, Tom May’s “River City Folk,” went national. KVNO is no longer associated with the show. Ironically, the show now airs on KVNO’s local public radio competitor, KIOS.

With a little help from its friends

One thing that’s never changed is the importance of financial support. Corporation for Public Broadcasting funding only covers so much. The rest must come from donors, memberships and sponsors. The station has thousands of loyal fans and some very generous funders, but Buckingham says, “less than 10 percent of those who listen to KVNO on a regular basis actually take the initiative to pony-up and contribute financially. We are obviously not getting the message out effectively.”

Volunteering for pledge drives is another way to help.

He’s actively seeking prospective business sponsors with this pitch. “Underwriting on KVNO is a cost effective way to promote your business and raise your organization’s profile and image. We reach a very desirable demographic-audience.” It’s a more diverse audience than one might expect. “Our listeners are not just scholars, musicians, business leaders, writers, students, intellectuals and teachers. Our devoted listeners are also butchers, bakers and candlestick makers.”

Bottom line, he says KVNO adds to the city’s cultural fabric. It follows then that becoming a sponsor or member helps KVNO improve the quality of life, in turn making Omaha a more attractive place to live. The 2012 membership drive unfolds in March. To join or give, call 402-554-5866 or visit www.kvno.org.

The role the U.S. has played in Afghanistan and with visiting Afghans in this country is fraught with controversy. The same holds true for what the University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Center for Afghanistan Studies has done and continues doing in terms of training and immersion opportunities offered to Afghan students and professionals who come here to participate in various programs. The controversy stems from the complex problems facing Afghanistan, economically, politically, culturally, and the strategic motivations by Americans to aid, occupy, and control that country. Whether you see controversy or not depends on your point of view. Leaving politics and motivations aside, UNO’s programs have provided a link or bridge unlike few others in giving Afghans some of the tools they need to rebuild and restore their embattled and ravaged nation. This story from several years ago profiles a project that saw scores of Afghan women educators come here to further their professional development. The story appeared in truncated form in The Reader (www.thereader.com) and here I’m able to present it in its entirety. This blog contains other stories I’ve written about UNO’s deep ties to Afghanistan.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The latest cadre of teachers in the University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Afghanistan Teacher Education Project return home this weekend after a month of training and cultural exchange Nebraska. This is the third group from Afghanistan to come here in the last year-and-a-half. A new group is scheduled to arrive in the fall. The program, supported by a grant from the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Cultural and Educational Affairs, is part of the UNO Center for Afghanistan Studies’ longtime efforts at repairing the war-ravaged Asian nation’s fractured education system.

Participants, all women, attend computer and intensive English language classes on the UNO campus and observe master teachers at two Omaha elementary schools. The women also visit schools and various attractions statewide, including the program’s satellite communities-schools in Oakland and Scottsbluff, Neb.

Once back in their homeland, the teachers share the skills and methodologies they acquired in the program with their peers. Each graduate is charged with training 10 colleagues from their school. That means the 37 graduates to date will soon have impacted some 370 teachers. Even more are reached via workshops and seminars the graduates present in conjunction with Ministry of Education officials. The women who completed the most training here were prepped for their American trip by their predecessors in the program. This trickle-down approach broadens the program’s reach, thus making a dent in the nation’s extreme teacher shortage.

The first group to come, in 2002, was an older, more tradition-bound bunch. The second, in 2003, were younger and more Westernized as would be expected from ESL teachers. This last cohort — all elementary school teachers — was further yet removed from the Taliban’s reach. Women are the focus of the program because their education was interrupted by prolonged fighting and then banned outright by the now deposed-Taliban. The radical fundamentalists made it a crime, punishable by beatings or reprisals, for females to teach and attend school. Some visiting teachers defied the ban and taught secretly under the repressive regime.

Aabidah, a teacher at Nazo Anaa Middle School in Kabul, is one of 12 women who attended the UNO program in April and May. She risked everything to practice her profession against Taliban edicts. “Yes, it was dangerous. I had six girls in my home. Daughters of friends and neighbors. It was done very secretly,” she said. Under the guise of teaching sewing, she instructed girls in Dari, Pashto and other subjects.

The teachers, ranging in age, experience and sophistication, have made an enduring impression on everyone they’ve met, including their host families and instructors. Robin Martens, who along with her husband, Gene, hosted Aabidah and another Afghan teacher, Lailumaa Popal, at their northwest Omaha home, is impressed with Aabidah’s fearlessness. “She seems to be a brave person. She has a strong personality and she kind of forges ahead even when she’s not sure about things. I like that about her,” Martens said. Regarding the quieter Lailumaa, a teacher at Lycee Zarghoonah in Qandahar, Martens observed, “She’s very caring and I think she must be a very good teacher because whenever I mispronounce a word in Dari, I laugh it off, but she insists I say it correctly.”

Barbara Davis, an Omaha Public Schools reading specialist, has hosted Afghan women in her Benson home. For Davis, they define what it is to be “courageous” under crisis. “If I were in the same situation I don’t know if I could have taught school in my home with the threat of my life. I really don’t know.”

In the capital city of Kabul, where most early training participants came from, women enjoy relative freedom to work and teach and go out on the streets sans chadri (or burqa), the traditional full-body veil. But even Kabul was a harsh place in the grip of the Taliban. “The Taliban was very bad. Very dangerous,” Aabidah said. “When they were in Kabul we don’t have jobs. We stay at home. We wear chadri. No, I don’t like chadri. It was very hot. I like the freedom. Now, we are free and happy. I like all of this in my country.” Things haven’t changed much in more provincial areas, where many recent participants reside and work. Women there must proceed with greater caution. “In Kabul, it’s OK. Outside Kabul, it’s bad,” Aabidah said referring to the current climate for women in Afghanistan.

Lailumaa fled with members of her family to Pakistan during the struggle for power in Afghanistan that erupted in civil war in the 1990s. Coming from a family of educators that regards teaching as a higher calling, Lailumaa said she greatly missed her students and her craft. After combined U.S.-Afghan forces ousted the Taliban in 2001, she returned to her homeland to resume teaching.

In the wake of the Taliban’s fall, Lailumaa, Aabidah and other women educators teach openly again. It’s the one thing they can do to restore their country. Aabidah said she teaches because “I love my children, my students, my people. I want a good future for them.” Baiza, a 2002 program grad who taught geography-history in a Mazar Sharif school, said then, “Students are part of my life.”

Sandra Squires, a UNO professor of speech-language-communication disorders, feels a kinship with her Afghan counterparts: “I realize that except for all the trappings, we’re all teachers,” she said. “We’re all very much alike. We love kids and we want to be doing something that can better the world, and that’s universal.” Aabidah feels the same. “Yes, I feel the teachers here are like my sisters,” she said.

In 2002, Baiza described the responsibility she and her fellow teachers feel to transform education at home with the “new concepts and skills” they learn here.

The Afghans have been motivated to be change agents, according to Anne Ludwig, assistant director of the ILUNA, the intensive language program at UNO. “What I see is women who are prepared, enthusiastic and eager to go home and make a difference in their lives and in the lives of other women,” Ludwig said. “I think they learn what they come to learn. One of them said what she would take back more than anything else was the idea that in the American classroom we want the students to feel good and positive, whereas back home the teacher is the autocrat and students are made to feel inferior. She liked the idea of opening up the classroom to where students feel safe, free to communicate and achieve.”

Practicums presented by Howard Faber, an Omaha Dodge Elementary 6th grade teacher fluent in Farsi, demonstrate good teaching practices the Afghans can implement in their own classrooms. He introduced the most recent group to Teacher Expectation Student Achievement or TESA, a set of methods promoting fairness and equality in learning, an issue of great import in Afghanistan, where ethnic-religious differences run deep. As former refugees resettle the country, he said, classrooms are filling with students of widely varying backgrounds and ages.

Faber feels the women symbolize their country’s hoped-for healing. “They’re from different places and different ethnic groups, and I think it’s very positive you have these people of varied cultural backgrounds working together on this common project. I think it bodes well for what might happen in Afghanistan, which now is a little bit like the United States was after the Civil War. You have deep feelings that are going to die slowly. Part of the healing there has to be that these cultural groups that fought so long work together.”

He said TESA alerts teachers to biases they harbor and offers strategies for giving “all children an equal opportunity to participate and to learn and to feel valued and welcomed. I show them what I do in my own classroom. They’re very practical things you don’t need a computer to do.” Later, he and the women discuss what transpired. “They ask me things…they really immerse themselves in the classroom. They even teach children a bit of their language. The kids are especially curious about them writing from right to left. It’s connected well with our studies.”

UNO’s Sandra Squires said the women’s devotion to teaching in the absence of basics makes her feel “very humbled. They’re doing things with absolutely nothing. I mean, they have to solve problems in ways I never had to dream about.” For their return trip, UNO gives each visiting teacher a laptop computer and a backpack filled with school supplies. But as UNO professor of education Carol Lloyd noted, “It still is barely a ripple in this ocean of need.”

Education is a mixed bag in Afghanistan. When schools reopened to great fanfare in 2002, far more students than expected flooded classrooms, which then, like now, were makeshift spaces amid rubble or cramped quarters. That surge has never let up as more refugees return home from camps in Iran and Pakistan. Overcrowded conditions and high student-teacher ratios continue to be a problem. Damaged schools are being rebuilt and new ones going up, but demand for classrooms far exceeds supply. For example, Aabidah’s school has 16 classrooms for its 3,000-plus students. Already scarce resources are siphoned off or entangled in red-tape.

“The schools are running by the enthusiasm of the parents and the commitment of the teachers, but there isn’t much government or international support for education,” said Raheem Yaseer, assistant director of UNO’s Center for Afghanistan Studies. “Schools don’t get enough funds and when they do get funds, a project that is started then stops because the funds dry up or are misused.”

Tom Gouttierre, director of UNO’s Center for Afghanistan Studies, said education is hindered by the “piecemeal application” the U.S. is taking to that nation’s recovery. “We’re trying to do Afghanistan on the cheap, because we’re focusing so many of our dollars on Iraq. So, we wind up bringing in a lot of other participants in a kind of donor conference approach to reconstruction and development. It leaves Kabul overrun by all kinds of different aid organizations, but with no coordination and no real firm Marshall Plan approach. It’s very hard for the Ministry of Education to coordinate it into one central educational plan for the country. It’s frustrating.”

“There is a great need for women teachers in the provinces and the women want to go, but they cannot. First, their families will not let them go and, second, the families themselves will not go because warlords and local commandos control the areas. People are scared. Also, parents are hesitant to let their girls go to school because the extremism and fanaticism in these regions is threatening,” Yaseer said.

Such fears are part of larger safety issues that find land mines littering roads and fields and Taliban loyalists and rebels waging violence. “There are some obstacles on the way to progress and security is number one,” Yaseer said. Aabidah agrees, saying that even above resources, “We want security. That’s our big problem.”

The challenge, too, is training enough teachers to educate a rising student enrollment. “The paradox is there hasn’t been any real formal education for teacher trainers for a long time and yet there are more kids in school now than ever before, and so that means the gap between the training needed and the numbers of students in classes is great,” Gouttierre said. “Among Afghans there’s a realization of something having been lost for generations and a determination not to let it get away from them again.”

Gouttierre said the fact this most recent crop of visiting Afghan teachers came from underrepresented areas, reflects UNO’s attempts to extend teacher training “in places where we haven’t been.” Part of that training is being undertaken by past graduates of UNO’s Afghan Teacher Training Project in concert with the center’s on-site master teacher trainers. The project is just the most visible branch of a much larger UNO effort. For years, its center has been: holding workshops and conferences for Afghan professionals and leaders involved in its various reconstruction efforts; training more than 3,000 Afghan teachers in workshops staffed by teacher trainers in Kabul and Peshawar, Pakistan; and writing textbooks and printing and distributing them by the millions.

These far away efforts are personified by the visiting Afghan teachers, who represent the face and future of education in their country. The diverse women all share a passion for their people and for teaching. Although their stays here are relatively brief, their impact is great. After hosting two older Afghan women who called her “our daughter,” Charity Stahl said, “I will never be the same.” Stahl, assistant director of the Afghan Teacher Education Project, later visited the women in their homeland while volunteering for an NGO. Of their emotional reunion, she said, “I still can’t believe it.”

For Barbara Davis, hosting is a cultural awakening in which her guests call her “mother,” teach her to make Afghan meals or get her to perform native folk dances. Despite a language barrier, she felt the women revealed their true selves behind the veil. “We really got to know each other,” she said. “We talked just like sisters. These are some of the warmest, dearest women I’ve ever met.”

The experience is equally meaningful to the Afghans. Aabidah called the training program “very interesting and very good” and described America as “not like in the movies. The people are very kind and hospitable. When I go back to Afghanistan, I’ll miss our dear host family and our American friends. They’re like my family in Afghanistan.” Coming to America, she said, “is like a dream for me.”

Her hosts, the Martens, will cherish many things. The pleasure Aabidah and Lailumaa took in cooking native dishes for them or in wiling away nights sitting around and talking, Or, what sharp bargain shoppers the women proved to be. Or, how thrilled they were to drive, for the first time, as the couple watched nervously on. “They’re people just like us. They want the same things we do. For themselves. For their families. We have so much to share with each other,” said Gene Martens.

When I saw Hadely Heavin perform classical guitar at the Joslyn Art Museum in the late 1980s I knew I had to write about him one day, and in 1990 I sought him out as one of my first freelance profile subjects. I’ve culled that resuling story from my archives for you to read below. What I didn’t know when I interviewed him that first time is what a remarkable story he has. I mean, how many world-class classical guitarists are there that also compete in rodeo? How many are combat war veterans? What are the chances that an inexperienced American player (Heavin) would be selected by a Spanish master (Segundo Pastor) to become the maestro’s only student in Spain? I always knew I wanted to revisit Heavin’s story and nearly two decades later I did. That more recent and expansive portrait of Heavin can also be found on this blog, entitled, “Hadley Heavin’s Idiosyncratic Journey as a Real Rootin-Tootin, Classical Guitar Playing Cowboy.” When I wrote the original article posted here Heavin’s mentor, Segundo Pastor, was still alive. Pastor has since passed away but his influence will never leave the protege. Heavin was still doing some rodeoing as of three or four years ago, when I did the follow-up story, but even if he has completely given up the sport he’ll always do something with horses because his love for horses is just that deep in him. The same as music is. I hope you enjoy these pieces on this consumate artist and athlete.

From the Archives: Hadley Heavin sees no incongruity in being rodeo cowboy, concert classical guitarist, music educator and Vietnam combat ve

©by Leo Adam Biga

Orignally published in the Omaha Metro Update

Hadley Heavin defies pigeonholing, The 41-year-old Omaha resident is an internationally renowned classical guitarist, but to ranchers in rural Nebraska he’s better known as a good rodeo hand. The University of Nebraska at Omaha instructor’s life has been full of such seeming incongruities from the very start.

Back in his native Kansas Heavin is as likely to be remembered for being a precocious child musician as an expert bareback bronc rider, star high school athlete and Vietnam War veteran. Today, despite lofty success as a touring performer, Heavin is perhaps proudest of being a husband and new father. He and his wife, Melanie, became first-time parents last year when their girl, Kaitlin, was born.

Music, though, has been the one unifying force in his life. His earliest memories of the Ozarks are filled with gospel harmonies and jazz, ragtime and country rhythms. Home for the Heavin clan was Baxter Springs, Kan., five miles froom the Oklahoma and Missouri borders.

“Basically I grew up with music and I’ve been playing it since I was 5. My father was a jazz guitarist and always had bands,” said Heavin. adding that his late father played a spell with Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys.

Heavin hit the road with his old man at age 7, playing drums, trumpet and occasional guitar at dances and socials.

“I was a little freak because I could play really well. I loved it, but it got to be a chore. I remember about midnight I’d start falling asleep. My dad would start to feel the time dragging and see me nodding, then he’d flick me ont he head with his fingertip and wake me up, and I’d speed up again.

“Most of my fellow students at school didn’t know I was doing this. I didn’t think I was doing anything special because everyone in my family were musicians. I grew up in that environment thinking everybody was like this. I couldn’t believe it when a kid couldn’t sing or carry a tune or do something with music.”

When Heavin was all of 11 he started playing rock ‘n’ roll, an experience, he said, that left him burned out on music, especially rock.

“I’m glad I got burned out on that when I did because I’ve still got students in their 20s trying to study classical guitar and wanting to play rock ‘n’ roll. They want to have fun,” he said disparagingly. “They just don’t realize rock is not an art form in the same sense. Classical guitar requires a lot of work and soul searching.”

Heavin doesn’t mince words when it comes to music. Since he studied in Spain with maestro Segundo Pastor, he performs and teaches the traditional romantic repertoire that originated there. He feels the music is a deep. direct reflection of the Spanish people, with whom he feels a kinship.

“Spanish people are much warmer than Americans. We’re not brought up with the passion those people are brought up with. That’s why I prefer listening to European artists.”

He said classical guitar “demands” a passionate, expressive quality he finds lacking in most American guitarists with the exception of Christopher Parkening.

“Who a student studies with makes a big difference. I don’t think I ever would have played the way I do if I had never studied with Segundo.”

Heavin feels Pastor selected him as a student because he saw a hungry young musician with a burning passion.

“He wouldn’t have been interested if he didn’t see things in my playing that were like his. Frankly, he doesn’t like very many American guitarists. He thinks they’re very shallow performers.”

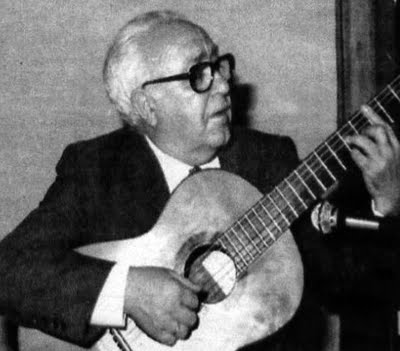

Segundo Pastor

The acolyte largely agrees, suggesting that part of the problem is most American musicians don’t face as many obstacles or endure as many sacrifices for their art as foreign musicians.

“My students are spoiled. How are they going to suffer for their art?” he asked rhetorically.

He said that when he turned to the classical guitar in the early ’70s, after seeing combat duty in Vietnam and having his father pass away, he knew what hard times were. “I suffered because by then my father was gone and my mother couldn’t support me. Somehow I played guitar and kept myself fed, but I didn’t have a penny, really, until I was 32. But I loved the guitar and I didn’t worry about those things. People are kind of unwilling to do that anymore.”

He dismissed the new guitarists who denigrate the traditional repertoire in favor of avant garde literature as mere technicians.

“I hate to say this but about all the concerts I’ve been to with the new guitarists have been very boring, driving audiences away from the guitar. It’s a real shame. They’re championing these avant garde works, which is fine, but they can’t play the Spanish and romantic repertoire at all. They just can’t phrase it. It’s not in them. They sound like they’re playing a typewriter.

“There’s a lot of great guitarists now, and they’re excellent technically, but there’s still only a handful of great musicians.”

He hopes artists like Parkening and Pastor help audiences “discern the guitarists from the musicians.”

It may surprise those who’ve seen Heavin perform with aplomb at Joslyn Art Museum’s Bagels and Bach series or some other concert venue that he as at ease on a horse as he is on a stage, as facile at roping a steer as he is at phrasing a chord, or as penetrating a critic of a rodeo hand’s technique as of a classical guitarist’s. But a look at his thick, powerful hands, deep chest and broad shoulders confirms this is a rugged man. And he does work out to stay in trim, including working with horses.

“As a matter of fact this is the first year I haven’t rodeoed in many years,” he said. “The only reason I’m not this summer is that I’m in the middle of doing an album and my producer’s worried about my losing a finger. I team rope now because I’m too old to ride rough stock. If I do get out of roping to protect my hands I’m probably going to have to do cutting or something just to stay on a horse. It’s just that horses are in my blood. But it’s tough with this kind of career because it takes so much time.”

Heavin has competed on the professional rodeo circuit all over Nebraska. “It’s funny,” he said. “I draw good crowds at my concerts in western Nebraska because I know all the ranchers and rodeo people, and they’re curious to see this classical guitarist who rodeos, too. I was playing a concert in Kearney and there were some roping friends in the audience. After I was done I went up and said to them, ‘These other people think I’m a guitarist, so don’t be telling them I’m a cowboy.’ But it was too late. They already had. I try not to advertise it too much.”

Heavin took to the rodeo as a boy to escape the music world he’d run dry on. “I started riding bulls and bareback broncs. I wanted to be a world champ bronc rider,” he said.. He rodeoed through high school and for a time in college. He also participated in football, wrestling and track as a prep athlete, winning honors and an athletic scholarship to Kansas University along the way.

“I think my dad put pressure on me to be an athlete to some degree because he wanted me to be well-rounded.”

At KU Heavin played on the same freshman football team as future NFL great John Riggins, a free-spirit known for his rebel ways. “I’ve never seen a guy that trouble came to so quickly. We used to go to bars and there was always a fight and John usually started it. He had more John Wayne in him than John Wayne.”

Another classmate and friend who became famous was Don Johnson, the actor. Heavin hasn’t seen the Miami Vice star in years but stays in touch with his folks in Kansas.

It was the late ’60s and Heavin, like so many young people then, was torn in different directions. “I decided I really didn’t want to be in school but I had the draft hanging over my head. I took a chance anyway and dropped out…and I was drafted within two months.”

The U.S. Army made him an artillary fire officer and shipped him off to Vietnam before he knew what hit him. He shuttled from one LZ to another, wherever it was hot. “I was what they called a bastard. I was with the 1st Field Force. I was in the jungle the whole time. I saw base camp twice during a year in-country,” he said.

Heavin was shot in action and after recovering from his wounds sent back out to the war. Luckily, his tour of duty ended without further injury and he finished his Army hitch back home at Fort Riley, Kansas. While stationed there he began missing working with horses and on a whim one day entered the bareback at a nearby rodeo.

“I drew a pretty rank horse, plus I hadn’t ridden in years and I was still sore from my war injuries. I got hurt. When I got back to the base they were mad at me because I couldn’t pull my duty. They were going to court-martial me.”

Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed and the incident was forgotten. “When I got out of the service my dad died shortly thereafter, and there was no music anymore.” Heavin had been working a job unloading trucks for two years when a friend suggested they see a classical guitarist perform. The experience rekindled his love for music.

“I was enthralled. And it just came over me like that,” he said, snapping his fingers. “That’s how fast I made my deicison to play classical guitar.”

Until then Heavin said he had never really heard classical guitar, much less played it. He began by teaching himself.

“I worked really hard. As soon as my hands could take it I was practicing six to eight hours a day and working a full-time job — just so I could get into college.”

Heavin brashly convinced the chairman of the Southwest Missouri State University music department to start a degreed classical guitar program for him. “I said, ‘Look, I want to get a degree in guitar and I’m determined to do it. And I don’t know why nobody has a program in this part of the country.’ He said, ‘I agree, let’s try this and see what happens.'” As the pioneering first student hell-bent on finishing the program, Heavin graduated and he said the program has “grown into something really nice and become very popular.”

His chance meeting with his mentor-to-be, Segundo Pastor, occurred at a concert in Springfield, Mo., at which Heavin was playing and the maestro was attending on one of his rare American visits. Heavin was introduced to “this little old man who couldn’t speak English” and arranged to see him later. He played for Pastor in private and the master liked the young man’s musicianship. The two began a correspondence.

When Pastor returned the next year he asked to see Heavin. “I spent practically a whole day with him and I played everything I knew. Then he said, ‘If you come to Spain I’ll teach you for nothing.’ I didn’t realize then what this meant or how it was going to work out,” Heavin said. A university official aided Heavin’s overseas studies. But the student still had no inkling his apprenticeship would turn out to be what he termed “one of the most wonderful experiences of my life.”

“When I arrive there was an apartment for me. The maestro’s wife was like my mom. His son was like my brother. And I realized only after I got there that I was his only student. He rarely takes them. There were Spanish boys waiting in line to study with him.”

Appropriately, the rodeoer lived a block from the Plaza de Toros, the bullfighting arena, and next door to the hospital for bullfighters.

“I lived in the culture. I wasn’t with Americans at all. My friends were all Spanish. I taught them English, they taught me Spanish. During the 10 months I was there I had a two-hour lesson from Segundo almost every day. He puts all of himself into that one student. That’s why he doesn’t take on many. It was really like a fairy-tale because the man literally gave me a career. The thing that’s odd about it is that I had only been playing about a year when the maestro invited me to Spain. It was confusing because there were Spanish boys who could play better than I.”

It was a question that nagged at Heavin for a long time. why me?

“The whole time I was in Spain I kept asking him, ‘Why did you pick me?’ and he would never answer it. The last night I was there he knocked on my door and we went to the university in Madrid. It was one of those romantic Spanish evenings. We were walking down a wet, cobblestone street and he put his arm on me and said, ‘Yeah, the Spanish boys are good guitarists but some day you’ll be a great guitarist,” recalled Heavin, still touched by the memory. “That gave me a lot of confidence to go on.”

During his stay abroad Heavin toured with Pastor throughout Spain, When the apprenticeship ended they performed duo concerts across the U.S., including New York’s Carnegie Hall. Heavin’s career was launched.

While the two haven’t performed publicly since then, Heavin said they remain close. “Now that I’m in the States he comes more often. When he visits we just have fun and enjoy ourselves. Two years ago he came with Pedro, a friend from Spain, and they did a duo concert here.”

Asked if in some way Pastor replaced his father, with whom he was so close, and Heavin said, “Oh yes. He’s like my father, no doubt. He’s my mentor, too.”

After earning a master’s degree at the University of Denver Heavin came to UNO in 1982. He heads the school’s classical guitar program, which he said is a good one. “I’ve got some students who play very well.”

Besides teaching Heavin performs 25-30 concerts a year, a schedule he’s cut back in 1990 to work on his first album.

“I’ve just finished doing the research on the pieces I want to put on. Now I’m learning the pieces. I’ll probably go into the recording studio in October or November,” he said.

As with Pastor singling him out for the chance of a lifetime, a patron has discovered Heavin and is helping sponsor him. “Another fairy-tale happened. A stockbroker heard me play and thinks I should have lots more recognition. He wants to get involved in my career.”

The guitarist is looking forward to touring more once the album is done. He has been invited to perform in Australia and Pastor has asked him to do concerts in Spain.

“People ask me why I live in Omaha and not on the coast,” he said. “I dearly love Omaha. I love the Old Market. I don’t like huge cities.”

Heavin, who practices his art about five hours daily, said success has little to do with locale anyway. “It’s an attitude. To do anything well requires an aggressive attitude. You have to just want to, and I’ve always done well financially playing guitar and teaching.”

This will likely be my last word on the demise of the University of Nebraska at Omaha wrestling program in 2011. As some of you may know from reading this blog or from following other media reports on the story, the program did nothing to contribute to its demise. Quite the contrary, it did everything right and then some. UNO wrestling reached the pinnacle of NCAA Division II competition and maintained its unparalleled excellence year after year. Yet university officials disregarded all that and eliminated the program. The action caused quite an uproar but the decision stood, leaving head coach Mike Denney, his assistants, and the student-athletes adrift. In a stunning turn, Denney is more or less taking what’s left of the orphaned program, including a couple assistants and 10 or so wrestlers, and moving the program to Maryville University in St. Louis, Mo. The following story for the New Horizons is my take on what transpired and an appreciation for the remarkable legacy that Denney, his predecessor Don Benning, and all their assitants and wrestlers established at a university that then turned its back on their contributions. It’s a bittersweet story as Denney closes one chapter in his career and opens a new one. It is UNO’s loss and Maryville’s gain.

UPDATE: By 2014, Denney had already made Maryville a national title contender. His team is ranked No. 1 in 2015-2016 and is the favorite to win this year’s D-II championship.

Mike Denney exhorting his troops to keep the faith

Requiem for a Dynasty:

Mike Denney Reflects on the Long Dominant, Now Defunct UNO Maverick Wrestling Program He Coached, Its Legacy, His Pain, and Starting Anew with Wife Bonnie at Maryville University

©by Leo Adam Biga

As published in the New Horizons

The For Sale sign spoke volumes.

Planted in the front yard of the home Mike and Bonnie Denney called their own for decades, it served as graphic reminder an Omaha icon was leaving town. The longtime University of Nebraska at Omaha wrestling coach and his wife of 42 years never expected to be moving. But that’s what happened in the wake of shocking events the past few months. Forced out at the school he devoted half his life to when UNO surprised everyone by dropping wrestling, he’s now taken a new opportunity far from home — as head coach at Maryville University in St. Louis, Mo.

The sign outside his home, Denney said, reinforced “the finality of it.” That, along with cleaning out his office and seeing the mats he and his coaches and wrestlers sweated on and achieved greatness on, sold via e-Bay.

On his last few visits to the Sapp Field House and the wrestling room, he said he couldn’t help but feel how “empty” they felt. “There’s an energy that’s gone.”

It wasn’t supposed to end this way. Not for the golden wrestling program and its decorated coach.

But this past spring the winningest program in UNO athletic history, fresh off capturing its third straight national championship and sixth in eight years, was unceremoniously disbanded.

Denney’s teams won two-thirds of their duals, claimed seven national team championships, produced more than 100 All-Americans and dozens of individual national champions in his 32 years at the helm. At age 64, he was at the top of his game, and his program poised to continue its dominant run.

“Let me tell you, we had a chance to make some real history here,” he said. “Our team coming back, I think we had an edge on people for awhile. We had some good young talent.”

UNO celebrates its 2010-2011 national championship

A measure of how highly thought of Denney is in his profession is that InterMat named him Coach of the Year for 2011 over coaches from top Division I programs. In 2006 Amateur Wrestling News made him its Man of the Year. That same year Win Magazine tabbed him as Dan Gable Coach of the Year.

Three times he’s been voted Division II Coach of the Year. He’s an inductee in both the Division II and UNO Athletic Halls of Fame. UNO awarded him its Chancellor’s Medal for his significant contributions to the university.

“I suppose you’re bound to have a little anger and bitterness, but it’s more sadness”

Yet, when all was said and done, Denney and his program were deemed expendable. Suddenly, quite literally without warning, wrestling was shut down, the student-athletes left adrift and Denney’s coaching job terminated. All in the name of UNO’s it’s-just-business move to Division I and the Summit League. The story made national news.

Response to the decision ranged from incredulity to disappointment to fury. To his credit, Denney never played the blame game, never went negative. But as print and television coverage documented in teary-eyed moments with his wrestlers, coaches and wife, it hurt, it hurt badly.

“I suppose you’re bound to have a little anger and bitterness, but it’s more sadness,” he said.

The closest he comes to criticism is to ask accusingly, “Was it worth it? Was the shiny penny worth it? Or are people worth it? What are you giving up for that? Your self? Your soul?”

Referring to UNO officials, Bonnie Denney said, “They’re standing behind a system that treats people very disrespectfully. You just don’t treat people like that, — you just don’t. We’ve got to put it in God’s hands and move on. We’re not going to let it pull us down. We’re going to keep our core and take it someplace else.”

Nobody saw it coming. How could they? Wrestling, with its consistent excellence and stability, was the one constant in a topsy-turvy athletic department. The decision by Chancellor John Christensen and Athletic Director Trev Alberts to end wrestling, and along with it, football, was inconceivable in the context of such unprecedented success.

Unprecedented, too, was a university jettisoning the nation’s leading program and coach without a hint of scandal or mismanagement. No NCAA rules violations. No financial woes. It would have been as if University of Nebraska-Lincoln higher-ups pulled the plug on Husker football at the height of Tom Osborne’s reign of glory.

An apples to oranges comparison? Perhaps, except the only difference between NU football and UNO wrestling is dollars and viewers. The Huskers generate millions in revenue by drawing immense stadium crowds and television audiences. The Mavericks broke even at best and drew only a tiny fraction of followers. Judging the programs solely by winning and losing over the last half-century, however, and UNO comes out on top, with eight national titles to NU’s five. Where UNO won minus sanctions, NU won amid numerous player run-ins with the law.

Noted sports psychologist Jack Stark has said Denney’s high character makes him the best coach in any sport in Nebraska.

USA Wrestling Magazine’s Craig Sesker, who covered Denney for the Omaha World-Herald, said, “He is a man of the highest integrity, values and principles. He’s an unbelievably selfless and generous man who always puts his athletes first.”

“He has a unique way of treating everybody like they’re somebody,” said Ron Higdon, who wrestled and coached for Denney. “He physically found a way to touch every guy every day at practice — touch them on the shoulder, touch them on the head. I learned so much from him. I have such incredible respect for him.

“One of the reasons I never left is I felt it was a special place. I felt such a connection that I felt this was the place for me. I feel so fortunate to have been a part of it.”

The influence Denney has on young men is reflected in the 60-plus former wrestlers of his who have entered the coaching profession.

“They not only kept going what we started, they did it even better than we did”

Denney created a dynasty the right way, but what’s sometimes forgotten is that its seeds were planted a decade earlier, by another rock-ribbed man of character, Don Benning. In 1963 Benning became the first African-American head coach at a predominantly white university when he took over the then-Omaha University Indian wrestling program. Having already made history with its coach, the program — competing then at the NAIA level — reached the peak of small college success by winning the 1970 national title.

Once a UNO wrestler or wrestling coach, always one. So it was that Benning and some of the guys who wrestled for him attended the We Are One farewell to the program last spring. The UNO grappling family turned out in force for this requiem. In a show of solidarity and homage to a shared legacy lost. wrestlers from past and present took off their letter jackets, vowing never to wear them again.

“Wrestling is kind of a brotherhood. It was my life, and so I had every reason to be there,” said Benning. “There was a lot of hurt in seeing what happened. It was devastating. We felt their pain.”

Benning said the event also gave him and his old wrestlers the opportunity to pay homage to what Denney and his wrestlers accomplished.

“It was a chance for us to say how much we appreciated them and to take our hats off to them. They not only kept going what we started, they did it even better than we did.”

Benning left after the 1971 season and the program, while still highly competitive, slipped into mediocrity until Denney arrived in 1979.

For Denney, Benning set a benchmark he strove to reach.

“When we came one of the first things I said was we want to reestablish the tradition that Don Benning started.”

A farm-raised, Antelope County, Neb. native, Denney was a multi-sport star athlete in high school and at Dakota Wesleyan college. He played semi-pro football with the Omaha Mustangs. He became a black belt in judo and jujitsu, incorporating martial arts rituals and mantras into his coaching. For example, he called the UNO wrestling room the “dojo.” He has the calm, cool, command of the sensei master.

He taught and coached at Omaha South and Omaha Bryan before joining the staff at UNO, where in addition to coaching he taught.

With his John Wayne-esque swagger, wide open smile, genial temperament, yet steely resolve, Denney was the face of an often faceless UNO athletic department. In a revolving door of coaches and ADs, Duke, as friends call him, was always there, plodding away, the loyal subject faithfully attending to his duties. You could always count on him. He modeled his strong Christian beliefs.

Under Denney UNO perennially contended for the national title and became THE elite program at the Division II level. He led UNO in organizing and hosting the nation’s largest single-day college wrestling tournament, the Kaufman-Brand Open, and a handful of national championship tournaments.

He was particularly fond of the Kaufman-Brand.

“I loved that tournament. It was a happening. Wrestlers came from all over for that. It was a who’s-who of wrestling. I mean, you saw world, Olympic and national champions. Multiple mats. Fourteen hundred matches.”

“We were a positive force…”

With everything that’s happened, he hasn’t had much time to look back at his UNO career. Ask him what he’s proudest of and he doesn’t immediately talk about all the winning. Instead, it’s the people he impacted and the difference his teams made. His guys visiting hospitals or serving meals at homeless shelters. The youth tournament UNO held. The high school wrestling league it organized. The clinics he and his coaches gave.

“We were a positive force in the wrestling community. I think its going to hurt wrestling in the area. We provided opportunities.”

Then there was the annual retreat-boot camp where his wrestlers bonded. The extra mile he and his coaches and athletes went to help on campus or in the community. The Academic All-Americans UNO produced. All the coaches the program produced.

Then, Denney gets around to the winning or more specifically to winning year in and year out.

“I think one of the most difficult things to do in anything is be consistent. If it was easy, everybody would be doing it. I think that consistency, year in and out, in everything you do is the biggest test.”

In its last season UNO wrestling went wire to wire No. 1. “Staying up there is the toughest thing,” said Denney.

“People don’t realize how difficult what they did really is,” said Benning, who knows a thing or two about winning.

Benning thinks it’s unfortunate that local media coverage of UNO wrestling declined at the very time the program enjoyed its greatest success. “They kind of got cheated in regards to their value and what they accomplished.”

“Whether it was on our terms or not, we went out on top. No one can ever take away what we accomplished,” said Ron Higdon.

Highs and lows come with the territory in athletics. Win or lose, Mike and Bonnie Denney were surrogate parents to their “boys,” cultivating family bonds that went beyond the usual coach-player relationship. Parents to three children of their own, the couple form an unbreakable team.