Archive

Shakespeare on the Green: A summertime staple in Omaha

Before you get the idea that the only thing happening this summer in my hometown is the Omaha Black Music and Community Hall of Fame Awards and Native Omaha Days, here’s a heads-up for this year’s rendition of the annual Shakespeare on the Green festival. The popular event has been packing them in for performances of the Bard’s plays at Elmwood Park for 25 years. The following story for Omaha Magazine gives a brief primer for how the fest started and what to expect at it. This blog is full of stories about and links to Omaha cultural attractions. It used to be people complained there wasn’t enough to do here, but now it’s quite the opposite – there’s so much to do that it’s hard choosing among the bounty.

Shakespeare on the Green

A summertime staple in Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in Omaha Magazine

When the annual Shakespeare on the Green festival returns this June and July, alternating two professional productions of the Bard’s work, it will mark the 25th season for one of Omaha‘s summer entertainment staples.

Over that time the free outdoor event has played to more than a half-million spectators in a tucked-away nook of Elmwood Park adjacent to the UNO campus.

The play’s certainly the thing at these relaxed evenings on the green and under the stars but the lively pre-show has its own attractions:

•food and souvenir booths

•interactive activities for youths

•live musical performances

•educational seminars to brush up your Shakespeare

•Two-Minute Shakespeare quizzes where the audience tries stumping the actors

•assorted jugglers, jesters and merrymakers.

On select nights Camp Shakespeare performances let school-age kids “speak the speech.” On June 26 Will’s Best Friend Contest invites dog owners to show off their pooches in Shakespearean splendor.

Co-founders Cindy Phaneuf and Alan Klem say the festival found a loyal following right from the start. The come-as-you-are ambience, bucolic site and free shows are hard to beat.

“We really woke up the space,” says Phaneuf. a University of Nebraska at Omaha theater professor.. “It’s a gorgeous location — 3.7 acres, naturally slanted, protected by trees, gobs of parking. Once you go down the hill it’s like you’re in a magical little world.”

Cindy Phaneuf

Whether a brooding tragedy or a lilting comedy an average of 2,000-plus folks flock to each performance. This year’s contrasting shows are A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Hamlet.

Phaneuf says some favorite memories are “the hushed silence of the crowd, the laughter that ripples from the front to back row and spontaneous standing ovations.” She likes that families make Shakespeare “part of their summer… part of their growing up.” Many fans return year after year to soak up the language, the outdoors and the communal spirit.

“It was always about the highest quality art we could possibly create but we also wanted an event where everyone felt comfortable,” says Phaneuf. “Shakespeare seems somewhat elitist but then we put it in an open environment, in a park, right in the middle of the city and it’s very inviting.

“The other thing that’s made it so lasting is we wanted everyone to feel they owned it — that it didn’t just belong to the board and to the people making the plays. If you cater only to a small faction it will not continue to grow and thrive, it will start to wither and die, and so that was really important to us.”

She says the festival alleviated a paucity of the Bard’s work performed locally and gave theatergoers a fix for for the usually dormant summer stage season.

“There was such a hunger and need for it,” she says. “There’s lots of theater in town but very little Shakespeare.”

While some theaters’ seasons now extend into summer the fest’s among Omaha’s only professional venues. Equity actors from across the nation headline their.

Alam Klem

Creighton University professor Alan Klem says the event not only presents good theater but supports and grows the local talent pool by hiring professional actors from the community and “bringing in students from Creighton and UNO who are working towards becoming actors.” Phaneuf says for many students it’s their first professional gig. Some, like Jill Anderson, earn Equity cards in the process.

“It just ups the ante and the expectation,” Phaneuf says. “It’s a great training ground.”

The festival’s only one element of the nonprofit Nebraska Shakespeare. Vincent Carlson-Brown and Sarah Carlson-Brown interned as UNO students, then worked through the ranks and today are associate artistic directors.

Besides being a learning lab and career springboard for emerging talent, thousands of high school students attend the Music Alive! collaboration with the Omaha Symphony. Nebraska Shakespeare also tours a fall production to schools throughout the state, complete with post-show discussions and workshops. Klem says these educational efforts are “as important as doing the plays out in the park,” adding that there are plans to expand the tours.

Klem and Phaneuf, who go back to their undergrad days together at Texas Christian University, say they knew they were onto something big when audiences turned out in droves year one. His experience founding Shakespeare in the Park in Fort Worth, Texas gave Shakespeare on the Green a head start. The Omaha fest has always been a collaboration between UNO and Creighton.

The two theater geeks served as co-artistic directors the first six years. Then Klem went onto other things — returning to act roles. Phaneuf continued in charge until resigning after the 2009 festival, when budget cuts resulted in one show rather than the usual two. The festival’s since rebounded. Klem’s back as artistic director and Phaneuf remains close to the organization.

Volunteers are critical to putting the event on. Phaneuf recalls once when high winds blew the set down during the day the stage crew and volunteers rebuilt it in time for that night’s show. She says that show-must-go-on dedication is what she appreciates most: “It’s people pulling together to make this happen. It’s a cooperative venture.” Klem marvels that the same spirit infusing the event 25 years ago still permeates it today.

Schedule-

A Midsummer Night’s Dream: June 23-26, July 6, 8, 10 and Hamlet: June 30, July 1-3, 7, 9

Performances start at 8 p.m. Booths open at 5:30. The pre-show starts at 7.

For more info., visit http://www.nebraskashakespeare.com/home.

Related articles

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Ushers in New Era of Omaha Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- In the land of Shakespeare (everythinginflux.wordpress.com)

- Much Ado About Shakespeare (mfcartaya.wordpress.com)

Omaha theater as insurrection, social commentary and corporate training tool

My usually eclectic blog has been theater heavy this week because I decided to celebrate the 2011 Great Plains Theatre Conference, which ends June 4, by sharing some of my theater stories from the recent and not so recent past. I’ll continue posting theater stories well after the conference closes because I discovered I have a nice cache of them, but I’ll also be back to showcasing the diversity of my work that regular followers have come to expect. I did the story below for The Reader (www.thereader.com) and it’s a look at how some Omaha theater professionals variously utilize the art form as insurrection, social commentary and corporate training tool.

Omaha theater as insurrection, social commentary and corporate training tool

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Making Images

Something subversive happened in the Old Market one recent Saturday evening.

From out of the blue, pedestrians converged on sidewalk corners and molded their bodies into dramatic sculpted “images.” One image included a man on his back cringing in terror as an assailant stood over him with a raised boot. Another posed father-and-son partners sealing a deal with a handshake that suddenly, inexplicably broke. A third linked people in a solid human chain until some unseen force rudely disturbed it.

If the symbolic frieze frames did not adequately convey their message of oppression, someone hanging anti-Initiative 416 (Defense of Marriage Amendment) signs around the individuals did, including one placard labeling the assault victim as a “Gay Man.” Just to be sure, another demonstrator handed out anti-416 leaflets.

These human tableauxs, so suggestive of figurative sculptures taking shape in front of your eyes, were in fact street theater pieces being used to focus awareness on the divisive 416 measure. The unfolding scenes were meant to make a statement, draw attention and engage people in dialogue about the issue. As the theater action progressed that night, a few curious passersby did stop to stare and proffer off-handed remarks. Then, when a plant in the crowd posing as an antagonist began spouting Biblical admonitions about same sex marriage and another plant posing as an initiative supporter began refuting his every protestation, some onlookers vigorously joined the debate on either side.

The ensuing discussion was the moment when this unorthodox piece of theater melded with genuine crowd reaction and, in so doing, accomplished exactly what organizers intended.

The Boal Way

So, was this event an example of art or theater or political activism? A little of all three, according to its instigator, University of Nebraska at Omaha Dramatic Arts Professor Doug Paterson. A self-described “insurrectionist” from the ‘60s, Paterson leads the UNO-based Thespis troupe (Theater Helping Everyone Solve Problems in Society), which follows many of the theories of Brazilian director Augusto Boal and his Theater of the Oppressed (T.O.) movement.

Boal, who came to Omaha in 1996 to give workshops, developed T.O. as a political tool to aid oppressed peoples around the world in their struggle for liberation. That night in the Market Paterson led his players in applying Boal’s image and invisible theater techniques (The professor played the antagonist in the crowd.). In keeping with their revolutionary roots, the drama that night was sprung – guerrilla-style – on unsuspecting folks in public spaces for the purpose of eliciting responses to a socially relevant issue. The ultimate aim, then or any time, is to incite action. Paterson organized a second theater event around the 416 measure at an October 31 rally on campus. Previous events have tackled the enduring UNO parking crisis.

Another Boal technique favored by Paterson – forum theater – utilizes workshops in which everyday people address problems at work or in their community through discussion and role playing led by a facilitator. In this interactive, outside-the-box approach to theater, the idea is to break down the Fourth Wall traditionally separating practitioner from audience and to build bridges connecting the two via conversation that works toward some resolution.

“Boal developed a theater that differs from the Western approach of pacifying you in the audience while actors describe a reality that you then take to be true. As an audience, you are powerless to change the story. You’re told, ‘This is the way it is,’ especially if you’re a minority. Boal believes in twisting things in a fun, open, community-based way that gives people a way to change the story. It’s what he calls interrogative theater. Rather than declare reality, it interrogates reality. It challenges the notion that it has to be this way — that it can’t be something else. It suggests new possibilities,” said Paterson, who has studied with Boal in Brazil.

Working It Out

Paterson has conducted forum theater workshops for many organizations, including the Omaha Public Schools, Creighton University and UNO. Workplace diversity issues are most commonly confronted, but not in the we talk-you listen vein.

“In forum theater we first play games to relax people and get them interacting with each other. Then we perform scenarios depicting some oppression, like a secretary given a last minute project by her boss when she needs to be someplace else,” he said. “The secretary tries overcoming her obstacle, but she just can’t. At some point we turn to the audience and say, “Okay, what would you do if you were her?’ Instead of having the audience sit there quietly we encourage them to talk to each other and share ideas to find some new solution.

“We encourage them to show how they would handle the situation differently, and it’s interesting because then it’s really them in the moment feeling sympathy for that character and the words almost become their own. Our attempt is to see if the audience is willing to be so moved and engaged by what’s happening that they really want to do something. Once they see something from their own life represented or dramatized, they think, ‘That’s me up there.’”

He said the response by participants is usually enthusiastic. “Often we can’t get through all the scenarios because there’s so much discussion. People get up and intervene and are very excited. I’ve never seen it fail.”

All the World’s a Stage

This grassroots theater has been a passion of Paterson’s since he discovered how deeply it resonated with his own emerging social consciousness amid the civil unrest in America a generation ago.

“I’ve been engaged in Theater for Living, Theater for Change or what has come to be known as Community-Based Theater since the mid-’70s,” he said. “I actively resisted the war in Vietnam while at Cornell University and it was during that time I formulated all my thinking about how culture works and how it is part of the oppressive process. I was really taken by the idea that if we could stake out new audiences, then we’d find a way to create a new culture in theater.

“Later, I started a small professional company in South Dakota whose purpose was to go into rural areas and engage farmers and ranchers in a kind of cultural salvage work where we found people’s stories and turned those into plays that we performed in these small towns.” He repeated the process when he came to UNO in 1981 – exploring the farm crisis with students in an original play (It Looks Good from the Road).

His students there included Omaha playwright Doug Marr and actress Laura Marr who, along with Paterson and others, formed the proletarian Diner Theater, which took this theater-happens-everywhere philosophy to heart. “

It drew a different group of people who might not have felt comfortable going to a regular theater setting,” Paterson said. “It was more neighborhood. It was more working class. It was site-specific. It was very exciting.”

Dramatic Results

The Marrs, along with fellow UNO theater grad Brent Noel, are adherents of Boal’s work and together operate a venture, Dramatic Results, incorporating the tenets of Boal in forum theater workshops at corporations.

“The trend today in business is to develop creativity and decision-making in employees, and Boal’s exercises are effective in helping build problem-solving skills,” Noel said. “We don’t offer answers or solve problems. We’re more interested in asking the right questions and encouraging people to think about possibilities. We offer a process whereby employees discover solutions. It’s empowering.” Noel said while many businesses are not yet ready to welcome theater techniques into their staid office settings, clients that do are satisfied. “Once they see how it works, most realize the value of it. It works in everything from sales to diversity to critical thinking training.”

Related articles

- A Q & A with Theater Director Marshall Mason, Who Discusses the Process of Creating Life on Stage (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jo Ann McDowell’s Theater Passion Leads Her on the Adventure of Her Life: Friend, Confidante, Champion of Leading Playwrights, Directors, Actors and Organizer of Major Theater Festivals and Conferences (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Playwright John Guare Talks Shop on Omaha Visit Celebrating His Acclaimed ‘Six Degrees of Separation’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Q & A with Playwright Caridad Svich, a Featured Artist at the Great Plains Theatre Conference (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Ushers in New Era of Omaha Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- action, alternatives and responsibility (artsandcraftscollective.wordpress.com)

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Q & A with Edward Albee: His Thoughts on the Great Plains Theatre Conference, Jo Ann McDowell, Omaha and Preparing a New Generation of Playwrights (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Hey, You, Get Off of My Cloud! Doug Paterson – Acolyte of Theatre of the Oppressed Founder Augusto Boal and Advocate of Art as Social Action (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Anthony Chisholm is in the House at the John Beasley Theater in Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Grows in New Directions (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- What Happens to a Dream Deferred? Beasley Theater Revisits Lorraine Hansberry’s ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Shakespeare on the Green, A Summertime Staple in Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Kevyn Morrow’s Homecoming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Hey, you, get off of my cloud! Doug Paterson is acolyte of Theatre of the Oppressed founder Augusto Boal and advocate of art as social action

I love University of Nebraska at Omaha theater professor Doug Paterson’s passion. In the following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) I profile how he’s melded his art and his social activism in a seamless way through Theatre of the Oppressed, a theater form he’s mastered under founder Augusto Boal. My story appeared in advance of the international Theater of the Oppressed Conference that Paterson and UNO hosted a couple years ago. I am posting the story here to highlight different aspects of Omaha theater in the wake of the 2011 Great Plains Theatre Conference, which wraps up June 4.

Hey, you, get off of my cloud!

Doug Paterson is acolyte of Theatre of the Oppressed founder Augusto Boal and advocate of art as social action

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Doug Paterson’s always used theater as an instrument of his insurrectionist principles. As a student in the 1960s he actively protested against the Vietnam War and other burning social issues and gravitated to progressive theater that challenged the status quo.

But it wasn’t until he saw Brazilian Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed in action that his social activism and his art merged into a philosophy and a way of life. Seventeen years later the University of Nebraska at Omaha professor is a leading adherent, practitioner, facilitator and teacher of T.O., as much a political movement dedicated to social change as a form of theater.

Much of T.O.’s work involves developing scenarios with audiences around the issues of racial, gender and class inequalities. The idea is to spark dialogue among citizens in a living or social theater environment. The end goal is to generate dialogue with decision-makers in the real world as a framework for addressing these matters with concerted action, even legislation.

It is meant to be an empowering process.

“We see something that affects us. Some oppression or injustice or wrong and we identify with it, we understand it and we yell, ‘Stop.’ To Boal the very act of saying we can stop this is by itself important,” Paterson said.

The premise of T.O., he said, is that the oppressed are “dictated to” by a privileged, power-wielding elite. “They’re not in the loop of determining what’s going to be the agenda of their life. They’re told what it’s going to be and often through force of violence.” What T.O. helps people do, he said, is “learn techniques and methods to interrogate the world. It’s developing a critical sensibility so they can talk to power and demand dialogue.”

Why theater as a device to elicit participation in the political process?

“Boal’s phrase is, ‘We’re all theater.’ We can all do this. We’re all doing it all the time because we’re all actors who can change the world,” Paterson said. “In Theatre of the Oppressed we just give it a little bit of shape — to help draw the power out of a person or a community, because it’s already there.”

Theater also provides a well-founded structure for protagonist-antagonist conflicts.

The UNO educator has studied with Boal, a short-list nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize, and “jokered” dozens of workshops with him and his son Julian Boal. Paterson’s led T.O. workshops in about a dozen states as well as in Canada, Israel, Palestine, Iraq and Africa.

T.O.’s organic, democratic system for giving the disenfranchised a voice is the focus of the May 22-25 International Pedagogy & Theatre of the Oppressed Conference in Omaha. Both Augusto and Julian Boal will give workshops using exercises and games that lead into T.O.’s Forum, Image, Invisible, Cop in the Head, Rainbow of Desire and Legislative theater.

The public’s invited to a free demonstration of Legislative Theatre at 7 p.m. on Thursday, May 22 in the Omaha City Council Chambers.

Six area elected officials will convene a mock legislative body to hear a set of scenes developed over three days of Forum workshops. These scenes built around local issues will be enacted and the floor thrown open for anyone to discuss, intervene, offer solutions. By the end of the session “legislation” will be devised and presented to the “council.” Paterson said Boal will then pose a question to the panel: “Would you support this legislation proposed by this temporary community?” That’s when the real dialogue and debate begins.

Paterson said to expect “a room “humming with activity,” lively discussion, laughter. “Nothing is coerced,” he said.

The dynamic interplay needs no formal introduction or explanation.

“If you see it you understand it immediately what it is and you can participate,” Boal said by phone from New York.

For Boal, T.O.’s not about finding solutions to problems but engaging people in exchanges that at least explore ways to combat or relieve oppression.

“I always say we should strive to have peace but the worst enemy of peace is passivity,” Boal said. “We must abolish passivity to try to do things in order to have real peace.”

True believers like Boal and Paterson believe in fighting oppression in whatever form it takes — violence, discrimination — through “the solidarity of the oppressed.” It is a movement of individuals and groups banded together in the belief that change is possible.

Paterson, who’s previously brought Boal to Omaha for this same conference, is a founder of the P.T.O. organization that puts the event on. This makes the seventh time Omaha’s hosted the event. It may also be the last, as Paterson plans to let new leadership take over.

The Omahan’s first direct exposure to T.O. came in Seattle in 1991. He was familiar with the tenets of Boal’s work but merely reading about it didn’t captivate him the way a demonstration did. Although Paterson had engaged in grassroots theater through the Dakota Caravan in the Black Hills and the Diner Theater in Omaha, he was still largely bound to traditional theater and its imposed world view that offer no mediation in or deviation from the end result.

Standing in stark contrast to that approach is T.O., which does not respect any fixed narrative or resolution. It’s all about inviting audiences and participants to intervene in and alter the story as a means for confronting and, if possible, ending oppression. Where traditional theater’s a monologue, T.O.’s a dialogue.

“I never got it,” Paterson said. “It sounded too serious. But then I saw it and it was so much fun and so interactive and so liberating that I said, ‘That’s it — I found where I’ve been heading for all my life.’ It just opened up possibilities. It’s asking through educational theater is it possible to transform the world to an equitable place economically, socially and politically.”

In Paterson’s view T.O. provides a structure for affecting change.

“Dealing with oppressed populations requires real dialogue…negotiation,” he said.

The goal, he said, is creating “a fair, equitable, humane world, a rational world where people have enough food and safe shelter, where crime is not encouraged by the economy, such as it is here, where poverty is not enforced, where violence is not the way of life. That’s what we want and all of us believe it’s possible.”

More than an academic or aesthetic construct, the work’s designed with real life applications in mind. Boal applies its techniques and forms to all kinds of community organizing, including his early-1990s bid for and election to the Rio de Janeiro city council as a member of the left-wing Workers Party. He used T.O. as an on-the-streets forum that gave people a sounding board to tell him what they wanted changed and he introduced legislation to try and bring about that change.

The more Paterson immersed himself in this new theater the more committed to it he became. The better he got to know Boal his conversion only deepened.

Augusto Boal

“I know Augusto as a mentor and quasi-father figure,” Paterson said. “I’ve spent a lot of time with him and we’ve talked far into the night. I really admire his work. I admire the mind that conceived of this and just kept relentlessly developing it. By continuing to work he made a path.”

Boal overturned his own traditional theater background in the ‘60s in response to oppressive military regimes in Brazil. At the time he headed the country’s national Arena theater, whose members began to resist the censorship and other government imposed strictures. Caught up in the struggle, Boal became politicized to a more militant, even radical stand. Branded a troublemaker, he was arrested, interrogated and tortured. Pressure from the West got him released but he soon became a political exile in Argentina and France.

He devised T.O. while in exile, drawing much inspiration from the late educational theorist Paulo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Boal was little known in the U.S. outside “a very narrow circle” when Paterson first contacted him and brought him to the states for the 1992 Association for Theatre in Higher Education national conference in Atlanta, Ga.

“Boal came to the conference and just carved a whole new channel for how to make theater and who to make theater for in the United States,” said Paterson. “It was a wonderful experience and we had a wonderful connection.”

T.O. is now practiced around the globe. It operates centers in several countries. Where the movement got scant media notice a decade ago it’s well covered today.

Paterson said there’s some resistance to the movement because “the word oppressed scares people.”

In Boal’s homeland, where he lives once again, the Workers Party-controlled state government has a program called Cultura Viva (Culture Alive) that, Boal said, “helps us spread the Theatre of the Oppressed all over Brazil.” The program enables T.O. to work with schools, mental health facilities, prisons and other entities.

“This is the first time the government has supported the work that we do,” said Boal, an outspoken critic of Brazilian government since the ‘60s.

Just as for Boal the work is not an abstraction, neither is it for Paterson or for conference registrants, who include theater educators and community activists from across the U.S., Europe and other parts of the world.

Locally, Paterson hopes it’s a model groups adopt for presenting grievances to local elected officials that address some of Omaha’s long-standing oppressions. He referred to African Americans’ disproportionate poverty here.

“We’ve really violated their human rights and we need dialogue,” said Paterson, noting Omaha’s high incidence of black on black crime and sexually transmitted diseases and the ongoing segregation that divides blacks and whites. “There’s so much to do.”

Related articles

- Playwright/Director Glyn O’Malley, Measuring the Heartbeat of the American Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Ushers in New Era of Omaha Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Grows in New Directions (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Polishing Gem: Behind the Scenes of the Beasley Theater & Workshop’s Staging of August Wilson’s ‘Gem of the Ocean ‘ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Q & A with Theater Director Marshall Mason, Who Discusses the Process of Creating Life on Stage (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- action, alternatives and responsibility (artsandcraftscollective.wordpress.com)

- Playwright John Guare Talks Shop on Omaha Visit Celebrating His Acclaimed ‘Six Degrees of Separation’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Theater as Insurrection, Social Commentary and Corporate Training Tool (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- What Happens to a Dream Deferred? Beasley Theater Revisits Lorraine Hansberry’s ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

OLLAS: A melting pot of Latino/Latin American concerns

As Nebraska‘s Hispanic population has grown significantly the past two decades there’s an academic-research-community based organization, OLLAS or Office of Latino and Latin American Studies, at the University of Nebraska at Omaha that’s taken a lead role in engaging policymakers and stakeholders in Latino issues and trends impacting the state. I’ve had a chance the past two years to get to know some of the people who make OLLAS tick and to sample some of their work, and the level of scholarship and dedication on display is quite impressive. The following story for El Perico gives a kind of primer on what OLLAS does. Increasingly, my blog site will contain posts that repurpose articles I’ve written for El Perico, a dual English-Spanish language newspaper in Omaha and a sister publication of The Reader (www.thereader.com). These pieces cover a wide range of subjects, issues, programs, organization, and individuals within the Latino community. It has been my privilege to get to know better Omaha’s and greater Nebraska’s Latino population, though in truth I’ve only barely dipped my feet into those waters. But it’s much the same enriching experience I’ve enjoyed covering Omaha’s African-American and Jewish communities.

OLLAS:

A melting pot of Latino/Latin American concerns

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in El Perico

Despite an ivory tower setting, the Office of Latino/Latin American Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha is engaged in community from-the-grassroots-to-the-grasstops through teaching, research and service.

The far reach of OLLAS, established in 2003, is as multifaceted as Latino-Latin American cultures and the entities who traverse them.

“We work very hard to bring to the table the different voices and stakeholders that seldom come together but that must be part of the same conversations. We do that very well,” said director and UNO sociology professor Lourdes Gouveia.

“We’ve been able to construct a program around this very out-of-the-box idea” that academia doesn’t happen in isolation of community engagement and vice-versa. Instead, she said these currents occur together, feeding each other.

“The impetus for creating this center was driven by what informs everything in my life, which is intellectual interest right along with an interest in addressing issues of inequality and social justice and making a difference wherever I am. So, for me, OLLAS was a logical project we needed to undertake.”

At the time of its formation Gouveia was researching immigration’s impact in Lexington, Neb. “It was clear to those of us witnessing all the changes going on we needed a space in the university that addressed those changes with kind of freshened perspectives very different from the old models of ethnic studies.”

Assistant director and UNO political science professor Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado said, “We very intentionally created something that would have a community base and not talk down to it, but try to make it a part of what we do. We wanted our work to be not only politically but socially relevant and that has been the basis for the outreach projects we’ve undertaken. OLLAS has been central to helping me live out what I do in my community.”

OLLAS produces reports on matters affecting Latino-Latin American segments in Nebraska, including the economic impact of immigrants, voter mobilization results and demographic trends. Gouevia said the office takes pains to distinguish the Guatamalan experience from the Mexican experience and so on. She said it can be daunting for Individuals and organizations to navigate the rapid social-political-cultural streams running through this diverse landscape of highly mobile populations and fluid issues. OLLAS serves as an island of calm in the storm.

“I think people take solace in the fact that when things get too muddled and when things are going too fast ,” she said, “they can turn to us, whether as an organization or as individuals, and say, What do you think of this?”

“We’re a resource for the community. When it needs perhaps more academic analysis of something, they look to OLLAS for that,” said Benjamin-Alvarado. “I think one of the other things people see us as is a real resolute voice — not that we’re going to go out and be the advocates — but when they’re involved and things get crazy, they’ll call us here and say, ‘Are we doing the right thing?’ People look to us for guidance and support as they’re trying to build a foundation.”

Helping build capacity within Latino-Latin American communities is a major thrust of OLLAS. No one at OLLAS pretends to have all the answers.

“We recognize that while we may be able to provide some reflection, we’re not the complete experts about what goes on in this community. We learn an enormous from our community work,” Gouveia said. “We engage on a very egalitarian basis with community organizations and treat them with the respect they deserve as the fonts of knowledge they bring to the realities.”

“We’re actually very intentional about not assuming we know everything and that we have to lead everything,” said Benjamin-Alvarado. “For example, we often don’t lead the community meetings, we sit in the back of the room and let others assume those roles of leadership because they have been leading. I think the fact we treat others as equal and we’re willing to listen to them has engendered genuine partnerships in the community.’

One of those strong partnerships is with the Heartland Workers Center, an Omaha nonprofit that helps immigrant laborers deal with the challenges they face. The center teaches workers their rights and responsibilities.

Benjamin-Alvarado said far from the patriarchal, missionary approach others have traditionally taken with minority communities, OLLAS looks to genuinely engage citizens and organizations in ongoing, reciprocal relationships.

“We don’t go in and bless the community and come back, Oh look how good we have done, because that would be the wrong message. That has been the model that’s been utilized in the past by a lot of academic institutions in response to these types of communities, and they resent it greatly. They’ve been burned so many times in the past. We make sure what we do is interactive and iterative, and so it’s not a one-off. It’s something we continue to go back to all the time. It’s this constant back and forth, give and take.”

He said he and Gouveia recognize “there are other people in the community with immense knowledge who can articulate the issues in a way that resonates with the community more than we as academics could ever do.”

OLLAS also reaches far beyond the local-regional sphere to broader audiences.

“Something I think people are surprised about is how globally connected we are,” said Benjamin-Alvarado. “We are one of the major nodes of a global network on migration development both as scholars and ambassadors of the university. We’re all over the planet. It’s a demonstration of just how deeply connected we are.”

Gouveia said the May 14-15 Cumbre Summit of the Great Plains, which OLLAS organizes and hosts, “fits very well” the transnational focus of OLLAS. The event is expected to draw hundreds of participants to address, in both macro and micro terms, the theme of human mobility and the promise of development and political engagement. Presenters are slated to come from The Philipines, Ecuador, Mexico, Ireland, South Africa and India as well as from the University of Chicago and the Brookings Institution in the U.S.

A community organizations workshop will examine gender, migration and civic engagement. Representatives from social service agencies, the faith community, education, government and other sectors are expected to attend the summit, which is free and open to the public.

“We work with all these publics very carefully so that the community feels really invited as co-participants in these discussions, not simply as spectators or a passive public,” said Gouveia, who added the programs are interactive in nature.

“We put local people with the sacred cows, we mix and match, and the panels take on a life of their own,” said Benjamin-Alvarado. “An academic will be talking about something and a local will say, ‘Thats’ not the way it happens,’ and to me that’s music to my ears.”

Another example of the international scope of OLLAS is the summer service learning program that takes UNO students to Peru. Benjamin-Alvarado said the experience offers participants “an interesting perspective on urban Latin America. All of them come back completely motivated and transformed by what they learn and how they utilize their classroom lessons. These are not summer fun trips. the students work the whole time in a shantytown in Lima.”

This summer he’ll be a International Service Volunteers program faculty adviser/coordinator in either Ecuador or the Dominican Republic. He said the research and engagement he and Gouveia do abroad and at national conferences increases their knowledge and understanding, informing the analysis and teaching they do.

“Our college has said we’re a prime example of what’s now called the leadership of engagement,” said Gouveia. She added that the broad perspective they offer is why everyone from educators to elected officials to the Chamber of Commerce look to them for advice. “I’m very proud of how many people contact us. It’s a great feeling to know that we do fill a major void in this whole region to do this very unique combination of things,” she said.

Opening new spaces for learning is another mission objective of OLLAS. It has sponsored a cinemateca series at Film Streams featuring award-winning movies from Spanish-speaking countries. It’s involved in an outreach program at the Douglas Country Correctional Center, where UNO faculty provide continuing education to immigrant inmates. Gouveia and Benjamin-Alvarado said it’s about bringing compassion and humanity to powerless, voiceless people whose only crime may be being undocumented and using falsified records.

The scholars are satisfied that anyone who spends any time with OLLAS comes away with a deeper appreciation of Latino-Latin American cultures, history, issues. Benjamin-Alvarado said OLLAS grads are today teaching in classrooms, leading social service agencies, working in the public sector, attending law school. He fully expects some to hold key elected offices in the next 10 years. He and Gouevia feel that a more nuanced perspective of the Latino/Latin American experience can only benefit policymakers and citizens.

- Latino Voters Key to 2012 Florida Win (politics.blogs.foxnews.com)

- Latino Voices are Crucial in the Wake of Government Shutdown (prnewswire.com)

- Latinos Have Become The Largest Minority in The U.s (socyberty.com)

- Omaha’s St. Peter Catholic Church Revival Based on Restoring the Sacred (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- El Museo Latino in Omaha Opened as the First Latino Art and History Museum and Cultural Center in the Midwest (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Address by Cuban Archbishop Jaime Ortega Sounds Hopeful Message that Repression in Cuba is Lifting (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Featured Great Plains Theatre Conference Playwright Caridad Svich Explore Bicultural Themes (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Long Live Roberto Clemente, A New Exhibit Looks at this Late King of the Latin Ball Players and Human Rights Hero (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Related articles

- El Museo Latino in Omaha Opened as the First Latino Art and History Museum and Cultural Center in the Midwest (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Address by Cuban Archbishop Jaime Ortega Sounds Hopeful Message that Repression in Cuba is Lifting (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Featured Great Plains Theatre Conference Playwright Caridad Svich Explore Bicultural Themes (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Long Live Roberto Clemente, A New Exhibit Looks at this Late King of the Latin Ball Players and Human Rights Hero (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

UNO wrestling dynasty built on tide of social change

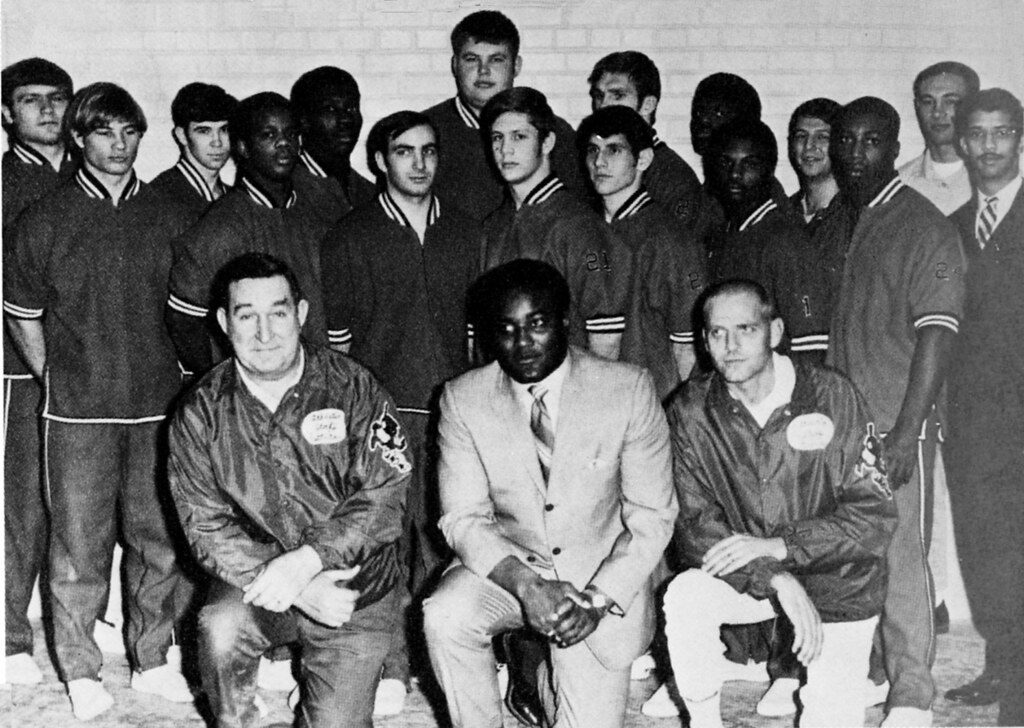

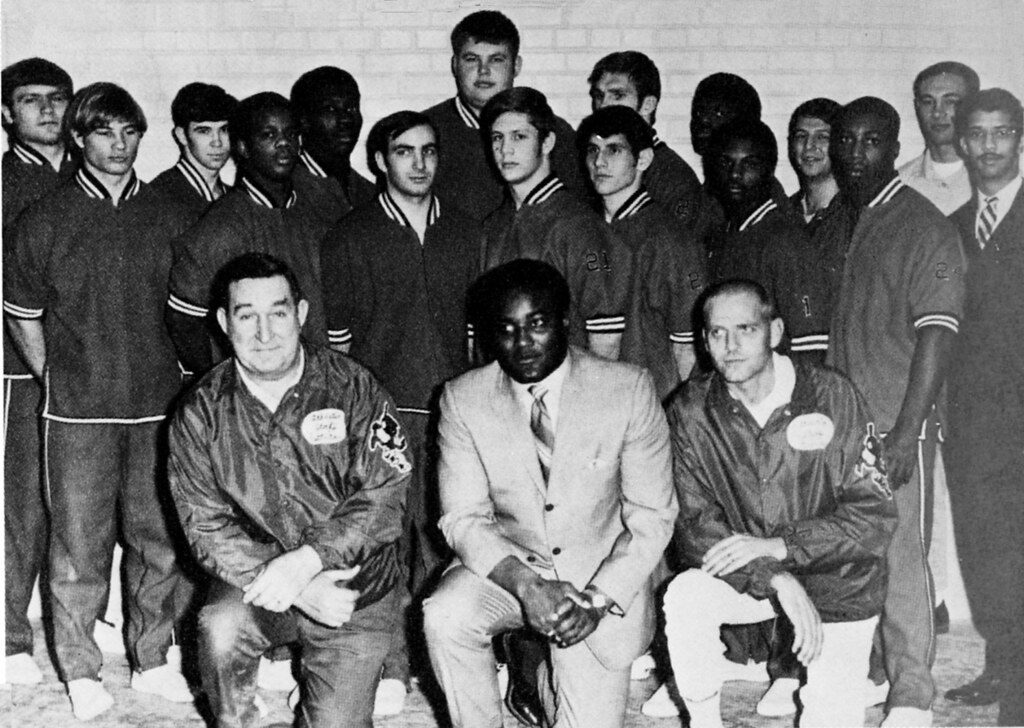

In my view, one of the most underreported stories coming out of Omaha the last 50 years was what Don Benning achieved as a young black man at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. At a time and in a place when blacks were denied opportunity, he was given a chance as an educator and a coach and he made the most of the situation. The following story, a version of which appeared in a March 2010 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com), charted his accomplishments on the 40th anniversary of making some history that has not gotten the attention it deserves. He made history at then-Omaha University as the nation’s first black coach of a major team sport at a predominantly white institution of higher education. I believe he was also the first black coach to lead a team at a predominantly white high education institution to a national championship. He laid the groundwork for the UNO wrestling dynasty that followed some years later under the leadership of Mike Denney, who always credited Don with getting the whole thing started.

In leading his team to the 1970 NAIA national title, when they roundly beat teams from from larger schools, he gathered around him a diverse group of student-athletes at a time when this was not the norm. A team coached by a young black man and comprised of whites, blacks and Latinos traveled to some inhospitable places where race baiting occured but he and his student-athletes never lost their cool. They let their actions speak for them.

One of the pleasures in doing this story was getting to know Don Benning, a man of high character who took me into his confidence. I shall always be grateful.

As the March 12-13 Division II national wrestling championships get underway at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, it’s good to remember wrestling, not hockey, is the school’s true marquee sport

Host UNO has been a dominant fixture on the D-II wrestling scene for decades. Its No. 1-ranked team is the defending national champs and is expected to finish on top again under Mike Denney, the coach for five of UNO’s six national wrestling titles. The first came 40 years ago amid currents of change.

Every dynasty has a beginning and a narrative. UNO’s is rooted in historic firsts that intersect racial-social-political happenings. The events helped give a school with little going for it much-needed cachet and established a tradition of excellence unbroken now since the mid-1960s.

It all began with then-Omaha University president Milo Bail hiring the school’s first African-American associate professor, Don Benning. The UNO grad had competed in football and wrestling for the OU Indians and was an assistant football coach there when Bail selected him to lead the fledgling wrestling program in 1963. The hire made Benning the first black head coach of a varsity sport (in the modern era) at a predominantly white college or university in America. It was a bold move for a nondescript, white-bread, then-municipal university in a racially divided city not known for progressive stances. It was especially audacious given that Benning was but 26 and had never held a head coaching position before.

Ebony Magazine celebrated the achievement in a March 1964 spread headlined, “Coach Cracks Color Barrier.” Benning had been on the job only a year. By 1970 he led UNO to its first wrestling national title. He developed a powerful program in part by recruiting top black wrestlers. None ever had a black coach before.

Omaha photographer Rudy Smith was a black activist at UNO then. He said what Benning and his wrestlers did “was an extension of the civil rights activity of the ’60s. Don’s team addressed inequality, racism, injustice on the college campus. He recruited people accustomed to challenges and obstacles. They were fearless. Their success was a source of pride because it proved blacks could achieve. It opened the door for other advancements at UNO by blacks. It was a monumental step and milestone in the history of UNO.”

Indeed, a few years after Benning’s arrival, UNO became the site of more black inroads. The first of these sawMarlin Briscoe star at quarterback there, which overturned the myth blacks could not master the cerebral position. Briscoe went on to be the first black starting QB in the NFL. Benning said he played a hand in persuading UNO football coach Al Caniglia to start Briscoe. Benning publicly supported efforts to create a black studies program at UNO at a time when black history and culture were marginalized. The campaign succeeded. UNO established one of the nation’s first departments of Black Studies. It continues today.

Once given his opportunity, Benning capitalized on it. From 1966 to 1971 his racially and ethnically diverse teams went 65-6-4 in duals, developing a reputation for taking on all comers and holding their own. Five of his wrestlers won a combined eight individual national championships. A dozen earned All-America status.

That championship season one of Benning’s two graduate assistant coaches was fellow African-American Curlee Alexander. The Omaha native was a four-time All-American and one-time national champ under Benning. He went on to be one of the winningest wrestling coaches in Nebraska prep history at Tech and North.

Benning’s best wrestlers were working-class kids like he and Alexander had been:

Wendell Hakanson, Omaha Home for Boys graduateRoy and

Mel Washington, black brothers from New York by way of cracker GeorgiaBruce “Mouse” Strauss, a “character” and mensch from back East

Paul and Tony Martinez, Latino south Omaha brothers who saw combat in Vietnam

Louie Rotella Jr., son of a prep wrestling legend and popular Italian bakery family

Gary Kipfmiller, a gentle giant who died young

Bernie Hospokda, Dennis Cozad, Rich Emsick, products of south Omaha’s Eastern European enclaves.

Jordan Smith and Landy Waller, prized black recruits from Iowa

|

Half the starters were recent high school grads and half nontraditional students in their 20s; some, married with kids. Everyone worked a job.

|

The team’s multicultural makeup was “pretty unique” then, said Benning. In most cases he said his wrestlers had “never had any meaningful relationships” with people of other races before and yet “they bonded tight as family.” He feels the way his diverse team came together in a time of racial tension deserves analysis. “It’s tough enough to develop to such a high skill level that you win a national championship with no other factors in the equation. But if you have in the equation prejudice and discrimination that you and the team have to face then that makes it even more difficult. But those things turned into a rallying point for the team. The kids came to understand they had more commonalities than differences. It was a social laboratory for life.”

“We were a mixed bag, and from the outside you would think we would have a lot of issues because of cultural differences, but we really didn’t,” said Hospodka, a Czech- American who never knew a black until UNO. “We were a real, real tight group. We had a lot of fun, we played hard, we teased each other. Probably some of it today would be considered inappropriate. But we were so close that we treated each other like brothers. We pushed buttons nobody else better push.”

“We didn’t have no problems. It was a big family,” said Mel Washington, who with his late brother Roy, a black Muslim who changed his name to Dhafir Muhammad, became the most decorated wrestlers in UNO history up to then. “You looked around the wrestling room and you had your Italian, your whites, your blacks, Chicanos, Jew, we all got together. If everybody would have looked at our wrestling team and seen this one big family the world would have been a better place.”

If there was one thing beyond wrestling they shared in common, said Hospodka, it was coming from hardscrabble backgrounds.

“Some of the kids came from situations where you had to be pretty tough to survive,” said Benning, who came up that way himself in a North O neighborhood where his was the only black family.

The Washington brothers were among 11 siblings in a sharecropping tribe that moved to Rochester, N.Y. The pair toughened themselves working the fields, doing odd-jobs and “street wrestling.”

Dhafir was the team’s acknowledged leader. Mel also a standout football lineman, wasn’t far behind. Benning said Dhafir’s teammates would “follow him to the end of the Earth.” “If he said we’re all running a mile, we all ran a mile,” said Hospodka.

Having a strong black man as coach meant the world to Mel and Dhafir. “Something I always wanted to do was wrestle for a black coach. It was about time for me to wrestle for my own race,” said Mel. The brothers had seen the Ebony profile on Benning, whom they regarded as “a living legend” before they ever got to UNO. Hospodka said Benning’s race was never an issue with him or other whites on the team.

Mel and Dhafir set the unrelenting pace in the tiny, cramped wrestling room that Benning sealed to create sauna-like conditions. Practicing in rubber suits disallowed today Hospodka said a thermostat once recorded the temperature inside at 110 degrees and climbing. Guys struggled for air. The intense workouts tested physical and mental toughness. Endurance. Nobody gave an inch. Tempers flared.

Gary Kipfmiller staked out a corner no one dared invade. Except for Benning, then a rock solid 205 pounds, who made the passive Kipfmiller, tipping the scales at 350-plus, a special project. “I rode him unmercifully,” said Benning. “He’d whine like a baby and I’d go, ‘Then do something about i!.” Benning said he sometimes feared that in a fit of anger Kipfmiller would drop all his weight on him and crush him.

Washington and Hospodka went at it with ferocity. Any bad blood was left in the room.

“As we were a team on the mat, off the mat we watched out for each other. Even though we were at each other’s throats on the wrestling mat, whatever happened on the outside, we were there. If somebody needed something, we were there,” said Paul Martinez, who grew up with his brother Tony, the team’s student trainer-manager, in the South O projects. The competition and camaraderie helped heal psychological wounds Paul carried from Vietnam, where he was an Army infantry platoon leader.

An emotional Martinez told Benning at a mini-reunion in January, “You were like a platoon leader for us — you guided us and protected us. Coming from a broken family, I not only looked at you as a coach but as a father.” Benning’s eyes moistened.

Joining them there were other integral members of UNO’s 1970 NAIA championship team, including Washington and Hospodka. The squad capped a perfect 14-0 dual season by winning the tough Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference tournament in Gunnison, Colo. and the nationals in Superior, Wis. It was the first national championship won by a scholarship team at the school and the first in any major sport by a Nebraska college or university.

Another milestone was that Benning became the first black coach to win an integrated national championship in wrestling and one of the first to do so in any sport at any level. He earned NAIA national coach of the year honors in 1969.

University of Washington scholar John C. Walter devotes a chapter to Benning’s historymaker legacy in a soon-to-be-published book, Better Than the Best. Walter said Benning’s “career and situation was a unique one” The mere fact Benning got the opportunity he did, said Walter, “was extraordinary,” not to mention that the mostly white student-athletes he taught and coached accepted him without incident. Somewhere else, he said, things might have been different.

“He was working in a state not known for civil rights, that’s for sure,” said Walter. “But Don was fortunate he was at a place that had a president who acted as a catalyst. It was a most unusual confluence. I think the reason why it happened is the president realized here’s a man with great abilities regardless of the color of his skin, and for me that is profound. UNO was willing to recognize and assist a young black man trying hard to distinguish himself and make a name for his university. That’s very important.”

Walter said it was the coach’s discipline and determination to achieve against all odds that prepared him to succeed.

Benning’s legacy can only be fully appreciated in the context of the time and place in which he and his student-athletes competed. For example, he was set to leave his hometown after being denied a teaching post with the Omaha Public Schools, part of endemic exclusionary practices here that restricted blacks from obtaining certain jobs and living in many neighborhoods. He only stayed when Bail chose him to break the color line, though they never talked about it in those terms.

“It always puzzled me why he did that knowing the climate at the university and in K-12 education and in the community pointed in a different direction. Segregation was a way of life here in Omaha. It took a tremendous amount of intestinal fortitude of doing what’s right, of being ready to step out on that limb when no other schools or institutions would touch African-Americans,” said Benning. He can only surmise Bail “thought that was the right thing to do and that I was the right person to do it.”

In assuming the burden of being the first, Benning took the flak that came with it.

“I flat out couldn’t fail because I would be failing my people. African-American history would show that had I failed it would have set things back. I was very aware of Jackie Robinson and what he endured. That was in my mind a lot. He had to take a lot and not say anything about it. It was no different for me. I had tremendous pressure on me because of being African-American. A lot of things I held to myself.”

Washington said though Benning hid what he had to contend with, some of it was blatant, such as snubs or slights on and off the mat. His white wrestlers recall many instances on the road when they or the team’s white trainer or equipment manager would be addressed as “coach” or be given the bill at a restaurant when it should have been obvious the well-dressed, no-nonsense Benning was in charge.

Hospodka said at restaurants “they just assumed the black guy couldn’t pay. They hesitated to serve us or they ignored us or they hoped we would go away.”

Washington could relate, saying, “I had a feeling what he was going through — the prejudice. They looked down on him. That’s why I put out even more for him because I wanted to see him on top. A lot of people would have said the heck with this, but he’s a man who stood there and took the heat and took it in stride.”

“He did it in a quiet way. He always thought his character and actions would speak for him. He went about his business in a dignified way,” said Hospodka.

UNO wrestlers didn’t escape ugliness. At the 1971 nationals in Boone, N.C., Washington was the object of a hate crime — an effigy hung in the stands. Its intended effect backfired. Said Washington, “That didn’t bother me. You know why? I was used to it. That just made me want to go out there more and really show ’em up.” He did, too.

“We were booed a lot when we were on the road,” Hospodka said. “Don always said that was the highest form of flattery. We thrived on it, it didn’t bother us, we never took it personal, we just went out and did our thing. You might say it (the booing) was because we were beating the snot out of them. I couldn’t help think having a black coach and four or five black wrestlers had something to do with it.”

Hospodka said wherever UNO went the team was a walking social statement. “When you went into a lot of small towns in the ’60s with four or five black wrestlers and a black coach you stuck out. It’s like, Why are these people together?” “There were some places that were awfully uncomfortable, like in the Carolinas,” said Benning. “You know there were places where they’d never seen an African-American.”

At least not a black authority figure with a group of white men answering to him.

The worst scene came at the Naval Academy, where the cold reception UNO got while holed up three days there was nothing compared to the boos, hisses, catcalls and pennies hurled at them during the dual. In a wild display of unsportsmanlike conduct Benning said thousands of Midshipmen left the stands to surround the mat for the crucial final match, which Kipfmiller won by decision to give UNO a tie.

The white wrestling infrastructure also went out of its way to make Benning and his team unwelcome.

“I think there were times when they seeded other wrestlers ahead of our wrestlers, one, because we were good and, two, because they didn’t look at it strictly from a wrestling standpoint, I think there was a little of the good old boy network there to try and make our road as tough as possible,” said Hospodka. “I think race played into that. It was a lot of subtle things. Maybe it wasn’t so subtle. Don probably saw it more because of the bureaucracy he had to deal with.”

“Some individuals weren’t too happy with me being an African-American,” said Benning. “I served on a selection committee that looked at different places to host the national tournament,. UNO hosted it in ’69, which was really very unusual, it broke a barrier, they’d never had a national championship where the host school had an African-American coach. That was pretty strange for them.”

He said the committee chairman exhibited outright disdain for him. Benning believes the ’71 championship site was awarded to Boone rather than Omaha, where the nationals were a big success, as a way to put him in his place. “The committee came up with Appalachian State, which just started wrestling. I swear to this day the only reason that happened was because of me and my team,” he said.

He and his wrestlers believe officials had it in for them. “There was one national tournament where there’s no question we just flat out got cheated,” said Benning. “It was criminal. I’m talking about the difference between winning the whole thing and second.” Refs’ judgements at the ’69 tourney in Omaha cost UNO vital points. “It was really hard to take,” said Benning. UNO had three individual champs to zero for Adams State, but came up short, 98-84. One or two disputed calls swung the balance.

Despite all the obstacles, Benning and his “kids” succeeded in putting UNO on the map. The small, white institution best known for its Bootstrapper program went from obscurity to prominence by making athletics the vehicle for social action. In a decade defined by what Benning termed “a social revolution,” the placid campus was the last place to expect a historic color line being broken.

The UNO program came of age with its dynamic black coach and mixed team when African-American unrest flared into riots across the country, including Omaha. A north side riot occurred that championship season. UNO’s black wrestlers, who could not find accommodations near the UNO campus, lived in the epicenter of the storm. Black Panthers were neighbors. Mel Washington, his brother Dhafir and other teammates watched North 24th St. burn. Though sympathetic to the outrage, they navigated a delicate line to steer clear of trouble but still prove their blackness.

A uniformed police cadet then, Washington said he was threatened once by the Panthers, who called him “a pig” and set off a cherry bomb outside the apartment he shared with his wife and daughter.

“I found those guys and said, ‘Anybody ever do that to my family again, and you or I won’t be living,’ and from then on I didn’t have no more problems. See, not only was I getting it from whites, but from blacks, too.”

Benning, too, found himself walking a tightrope of “too black or not black enough.” After black U.S. Olympians raised gloved fists in protest of the national anthem, UNO’s black wrestlers wanted to follow suit. Benning considered it, but balked. In ’69 Roy Washington converted to Islam. He told Benning his allegiance to Black Muslim leader Honorable Elijah Muhammad superseded any team allegiance. Benning released him from the squad. Roy’s brother Mel earlier rejected the separatist dogma the Black Muslims preached. Their differences caused no riff.

Dhafir (Roy) rejoined the team in December after agreeing to abide by the rules. He won the 150-pound title en route to UNO capturing the team title over Adams, 86-58. Hospodka said Dharfir still expressed his beliefs, but with “no animosity, just pride that black-is-beautiful. Dharfir’s finals opponent, James Tannehill, was a black man married to a white woman. Hospodka said it was all the reason Dharfir needed to tell Tannehill, “God told me to punish you.” He delivered good on his vow.

It was also an era when UNO carried the “West Dodge High” label. Its academic and athletic facilities left much to be desired. “The university didn’t have that many things to feel proud of,” said Benning. Wrestling’s success lifted a campus suffering an inferiority complex to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Wrestling was one area where UNO could best NU, whose NCAA wrestling program paled by comparison.

“Coach Benning and his wrestling teams elevated UNO right to the top, shoulder-to-shoulder with its big brother’s football team down the road,” said UNO grad Mary Jochim, part of a wrestling spirit club in 69-’70. “They gave everyone at the school a big boost of pride. The rafters would shake at those matches.”

“You’d have to say it was the coming-together of several factors that brought about a genuine excitement about wrestling at UNO in the late 1960s,” said former UNO Sports Information Director Gary Anderson. He was sports editor of the school paper, The Gateway, that championship season. “There were some outstanding athletes who were enthusiastic and colorful to watch, a very good coach, and UNO won a lot of matches. UNO had the market cornered. Creighton had no team and Nebraska’s team wasn’t as dominant as UNO. It created a perfect storm.”

Benning said, “It was more important we had the best wrestling team in the state than winning the national championship. Everybody took pride in being No. 1.” Anderson said small schools like UNO “could compete more evenly” then with big schools in non-revenue producing sports like wrestling, which weren’t fully funded. He said as UNO “wrestled and defeated ‘name’ schools it added luster to the team’s mystique.

NU was among the NCAA schools UNO beat during Benning’s tenure, along with Wyoming, Arizona, Wisconsin, Kansas and Cornell. UNO tied a strong Navy team at the Naval Academy in what Hospodka called “the most hostile environment I ever wrestled in.” UNO crowned the most champions at the Iowa Invitational, where if team points had been kept UNO would have outdistanced the big school field.

“We didn’t care who you were — if you were Division I or NAIA or NCAA, it just didn’t matter to us,” said Hospodka, who pinned his way to the 190-pound title in 1970. The confidence to go head-to-head with anybody was something Benning looked for in his wrestlers and constantly reinforced.

Said Hospodka,”Don always felt like we could compete against anybody. He knew he had talent in the room. He didn’t think we had to take a back seat to anybody when it came to our abilities. He had a confidence about him that was contagious.”

The sport’s bible, Amateur Wrestling News, proclaimed UNO one of the best teams in the nation, regardless of division. UNO’s five-years of dominance, resulting in one national championship, two runner-up finishes, a third-place finish and an eighth place showing, regularly made the front page of the Omaha World-Herald sports section.

The grapplers also wrestled with an aggression and a flair that made for crowd-pleasing action. Benning said his guys were “exceptional on their feet and exceptional pinners.” It wasn’t unusual for UNO to record four or five falls per dual. Washington said it was UNO’s version of “showtime.” He and his teammates competed against each other for the most stylish or quickest pin.

Hospodka said “the bitter disappointment” of the team title being snatched away in ’69 fueled UNO’s championship run the next season, when UNO won its 14 duals by an average score of 32-6. It works out to taking 8 of every 10 matches. UNO posted three shut outs and allowed single digits in seven other duals. No one scored more than 14 points on them all year. The team won every tournament it competed in.

Everything fell into place. “Nobody at our level came even close to competing with us,” said Hospodka. “The only close match we had was Athletes in Action, and those were all ex-Big 8 wrestlers training for the World Games or the Olympics. They were loaded and we still managed to pull out a victory (19-14).” At nationals, he said, “we never had a doubt. We had a very solid lineup the whole way, everybody was at the top of their game. We wrapped up the title before the finals even started.” Afterwards, Benning told the Gateway, “It was the greatest team effort I have ever been acquainted with and certainly the greatest I’ve ever seen.”

Muhammad won his third individual national title and Hospodka his only one. Five Mavs earned All-America status.

The foundation for it all, Hospodka said, was laid in a wrestling room a fraction the size of today’s UNO practice facility. “I’ve been in bigger living rooms,” he said. But it was the work the team put in there that made the difference. “It was a tough room, and if you could handle the room then matches were a breeze. The easy part of your week was when you got to wrestle somebody else. There were very few people I wrestled that I felt would survive our wrestling room.”

“It was great competition,” said Jordan Smith. “One thing I learned after my first practice was that I was no longer the toughest guy in the room. There were some recruits who came into that room and practiced with us for a few days and we never saw them again. I was part of something that really was special. It was a phenomenal feeling.”

This band of brothers is well represented in the Maverick Wrestling and UNO Halls of Fame. The championship team was inducted by UNO and by the Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference. Benning, Mel Washington, Dhafir Muhammad and Curlee Alexander are in the Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame. But when UNO went from NAIA to NCAA Division II in ’73 it seemed the athletic department didn’t value the past. Tony Martinez said he rescued the team’s numerous plaques and trophies from a campus dumpster. Years later he reluctantly returned them to the school, where some can be viewed in the Sapp Fieldhouse lobby.

UNO’s current Hall of Fame coach, Mike Denney, knows the program owes much to what Benning and his wrestlers did. The two go way back.

Benning left coaching in ’71 for an educational administration career with OPS. Mike Palmisano inherited the program for eight years, but it regressed.

When Denney took over in ’79 he said “my thing was to try to find a way to get back to the level Don had them at and carry on the tradition he built.” Denney plans having Benning back as grand marshall for the March of All-Americans at this weekend’s finals. “I have great respect for him.” Benning admires what Denney’s done with the program, which has risen to even greater heights. “He’s done an outstanding job”

As for the old coach, he feels the real testament to what he achieved is how close his diverse team remains. They don’t get together like they once did. When they do, the bonds forged in sweat and blood reduce them to tears. Their ranks are thinned due to death and relocation. They’re fathers and grandfathers now, yet they still have each other’s backs. Benning’s boys still follow his lead. Hospokda said he often asks himself, “What would Don want me to do?”

At a recent reunion Washington told Benning, “I’m telling you now in front of everyone — thank you for bringing the family together.”

Related Articles

- U. of Neb.-Omaha plans to move to Division I (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Nebraska at Omaha to join D-I’s Summit League (sports.espn.go.com)

- UNC Greensboro cuts wrestling program (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Dean Blais Has UNO Hockey Dreaming Big (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- UNO Wrestling Dynasty Built on a Tide of Social Change (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Letting 1,000 Flowers Bloom: The Black Scholar’s Robert Chrisman Looks Back at a Life in the Maelstrom

Six years ago a formidable figure in arts and letters, Robert Chrisman, chaired the Department of Black Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The mere fact he was heading up this department was symbolic and surprising. Squarely in the vanguard of the modern black intelligentsia scene that has its base on the coasts and in the South, yet here he was staking out ground in the Midwest. The mere fact that black studies took root at UNO, a predominantly white university in a city where outsiders are sometimes amazed to learn there is a sizable black population, is a story in itself. It neither happened overnight, nor without struggle. He came to UNO at a time when the university was on a progressive track but left after only a couple years when it became clear to him his ambitions for the academic unit would not be realized under the then administration. Since his departure the department had a number of interim chairs before new leadership in the chancellor’s office and in the College of Arts and Sciences set the stage for UNO Black Studies to hire perhaps its most dynamic chair yet, Omowale Akintunde (see my stories about Akintunde and his work as a filmmaker on this blog). But back to Chrisman. I happened to meet up with him when he was in a particularly reflective mood. The interview and resulting story happened a few years after 9/11 and a few years before Obama, just as America was going Red and retrenching from some of its liberal leanings. He has the perspective and voice of both a poet and an academic in distilling the meaning of events, trends, and attitudes. My story originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com) and was generously republished by Chrisman in The Black Scholar, the noted journal of black studies for which he serves as editor-in-chief and publisher. It was a privilege to have my story appear in a publication that has published works by Pulitzer winners and major literary figures.

Robert Chrisman

Letting 1,000 Flowers Bloom: The Black Scholar’s Robert Chrisman Looks Back at a Life in the Maelstrom

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) and republished with permission by The Black Scholar (www.theblackscholar.org)

America was at a crossroads in the late 1960s. Using nonviolent resistance actions, the civil rights movement spurred legal changes that finally made African Americans equal citizens under the law. If not in practice. Meanwhile the rising black power movement used militant tactics and rhetoric to demand equal rights — now.

The conciliatory old guard clashed with the confrontational new order. The assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy seemed to wipe away the progress made. Anger spewed. Voices shouted. People marched. Riots erupted. Activists and intellectuals of all ideologies debated Black America’s course. Would peaceful means ever overcome racism? Or, would it take a by-any-means-necessary doctrine? What did being black in America mean and what did the new “freedom” promise?

Amid this tumult, a politically-tinged journal called The Black Scholar emerged to give expression to the diverse voices of the time. Its young co-founder and editor, Robert Chrisman, was already a leading intellectual, educator and poet. Today he’s the chair of the University of Nebraska at Omaha (UNO) Department of Black Studies. The well-connected Chrisman is on intimate terms with artists and political figures. His work appears in top scholarly-literary publications and he edits anthologies and collections. Now in its 36th year of publication, The Black Scholar is still edited by Chrisman, who contributes an introduction each issue and an occasional essay in others, and it remains a vital meditation on the black experience. Among the literati whose work has appeared in its pages are Maya Angelou and Alice Walker.

From its inception, Chrisman said, the journal’s been about uniting the intellectuals in the street. “We were aware there were a lot of street activists-intellectuals as well as academicians who had different sets of training, information and skills,” he said. “And the idea was to have a journal where they could meet. By combining the information and initiative you might have effective social programs. That was part of the goal.”

Another goal was to take on the core issues and topics impacting African Americans and thereby chart and broker the national dialogue in the black community.

“We were aware there was a tremendous national debate going on within the black community and also within the contra-white community and Third World community on the forward movement not only of black people in the United States but also globally and, for that matter, of white people. And so we felt we wanted to register the ongoing debates of the times with emphasis upon social justice, economic justice, racism and sexism.

“And then, finally, we wanted to create an interdisciplinary approach to look at black culture and European-Western culture. Because one of the traditions of the imperialist university is to create specialization and balkanization in intellectuals, rather than synthesis and synergy. We felt it would be contrary to black interests to be specialists, but instead to be generalists. And so we encouraged and supported the interdisciplinary essay. We also felt critique was important. You know, a long recitation of a batch of facts and a few timid conclusions doesn’t really advance the cause of people much. But if you can take an energetic, sinewy idea and then wrap it and weave it with information and build a persuasive argument, then you have, I think, made a contribution.”

No matter the topic or the era, the Scholar’s writing and discourse remain lively and diverse. In the ’60s, it often reflected a call for radical change. In the 1970s, there were forums on the exigencies of Black Nationalism versus Marxism. In the ’80s, a celebration of new black literary voices. In the ’90s, the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill imbroglio. The most recent editions offer rumination on the Brown versus Board of Education decision and a discussion on the state of black politics.

“From the start, we believed every contributor should have her own style,” Chrisman said. “We felt the black studies and new black power movement was yet to build its own language, its own terminology, its own style. So, we said, ‘let a thousand flowers bloom. Let’s have a lot of different styles.’”

But Chrisman makes clear not everything’s dialectically up for grabs. “Sometimes, there aren’t two sides to a question. Period. Some things are not right. Waging genocidal war is not a subject of debate.”

The Meaning of Things

In an essay refuting David Horowitz’s treatise against reparations for African Americans, Chrisman and Ernest Allen, Jr. articulate how “the legacy of slavery continues to inform institutional as well as individual behavior in the U.S. to this day.” He said the great open wound of racism won’t be healed until America confronts its shameful part in the Diaspora and the slave trade. Reparations are a start. Until things are made right, blacks are at a social-economic disadvantage that fosters a kind of psychic trauma and crisis of confidence. In the shadow of slavery, there is a struggle for development and empowerment and identity, he said.

“Blacks produce some of the most powerful culture in the U.S. and in the world. We don’t control enough of it. We don’t profit enough from it. We don’t plow back enough to nurture our children,” he said. “Part of that, I think, is an issue of consciousness. The idea that if you’re on your own as a black person, you aren’t going to make it and another black person can’t help you. That’s kind of like going up to bat with two strikes. You choke up. You get afraid. Richard Wright has a folk verse he quotes, ‘Must I shoot the white man dead to kill the nigger in his head?’ And you could turn that around to say, ‘Must I shoot the black man dead to kill the white man in his head?’ The difference is that the white man has more power (at his disposal) to deal with this black demon that’s obsessing him.”

In the eyes of Chrisman, who came of age as an artist and intellectual reading Frederick Douglass, W. E. B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Robert Hayden, James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Vladimir Lenin, Karl Marx, Che Guevara, Pablo Neruda, Mao Tse-tung and the Beat Generation, the struggle continues.