Archive

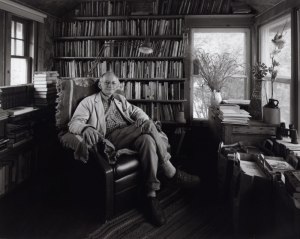

Author, humorist, folklorist Roger Welsch tells the stories of the American soul and soil

Roger Welsch is a born storyteller and there’s nothing he enjoys more than holding sway with his spoken or written words, drawing the audience or reader in, with each inflection, each permutation, each turn of phrase. He’s a master at tone or nuance. New Horizons editor Jeff Reinhardt and I visited Welsch at his rural abode, and then into town at the local pub/greasy spoon, where we scarfed down great burgers and homemade root beer. All the while, Welsch kept his variously transfixed and in stitches with his tales.

On this blog you’ll find Welsch commenting about his longtime friend and former Lincoln High classmate Dick Cavett in my piece, “Homecoming is Always Sweet for Dick Cavett.” Welsch shares some humorous (naturally) anecdotes about the talk show host’s penchant for showing up unannounced and getting lost in those rural byways that Welsch lovingly describes in his writing.

Author, humorist, folklorist Roger Welsch tells the stories of the American soul and soil

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the New Horizons

It’s been years since Roger Welsch, the author, humorist and folklorist, filed his last Postcard from Nebraska feature for CBS’s Sunday Morning program. Every other week the overalls-clad sage celebrated, in his Will Rogersesque manner, the absurd, quixotic, ironic, sublime and poetic aspects of rural life.

That doesn’t mean this former college prof, who’s still a teacher at heart, hasn’t been staying busy since his Postcard days ended. He’s continued his musings in a stream of books (34 published thus far), articles, essays, talks and public television appearances that mark him as one of the state’s most prolific writers and speakers.

In 2006 alone he has three new books slated to be out. Each displays facets of his eclectic interests and witty observations. Country Livin’ is a “guide to rural life for city pukes.” Weed ‘Em and Reap: A Weed Eater Reader is “a narrative about my interest in wild foods, a kind of introduction to lawn grazing and a generous supply of reasons to avoid lawn care,” he said. My Nebraska is his “very personal” love song to the state. “I believe in Nebraska. I love this place for what it is and not for what people think it ought to be,” he said. “I hate it when the DED (Department of Economic Development) tries to fill people full of bullshit about Nebraska. Nebraska’s great as it is. You don’t have to make up anything. You don’t have to put up an arch across the highway to charm people.”

In the tradition of Mark Twain and William Faulkner, Welsch mines an authentic slice of rural American life, namely the central Nebraska village of Dannebrog that he and artist wife Linda moved to 20 years ago, to inform his fictional Bleaker County. Drawing from his experiences there, he reveals the unique, yet universal character of this rural enclave’s people, dialect, humor, rituals and obsessions.

He’s also stayed true to his own quirky sensibilities, which have seen him: advocate for the benefits of a weed diet; fall in love with a tractor; preserve, by telling whenever he can, the tall tales of settlers; wax nostalgic over sod houses; serve as friend and adopted member of Indian tribes; and obsess over Greenland.

The only child of a working class family in Lincoln, Neb., he followed a career path as a college academician. His folklore research took him around the Midwest to unearth tales from descendants of Eastern European pioneers and Plains Indians. He lived in a series of college towns. By the early ‘70s he held tenure at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Then, he turned his back on a “cushy” career and lifestyle to follow his heart. To write from a tree farm on the Middle Loup River outside Dannebrog. To be a pundit and observer. People thought he was nuts.

“I walked away from an awfully good job at the university. People work all their lives to get a full professorship with tenure and…nobody could believe it when I said I’m leaving. ‘Are you crazy? For what?’ And, it’s true, I had nothing out here,” he said from an overstuffed shed that serves as an office on the farm he and Linda share with their menagerie of pets. “I was just going to live on my good looks, as I said, and then everybody laughed. That was before CBS came along.”

Before the late Charles Kuralt, the famed On the Road correspondent, enlisted Welsch to offer his sardonic stories about country life in Nebraska, things were looking bleak down on the farm. “We weren’t making it out here,” Welsch said. “I told Linda, ‘The bad news is, we’re not making it, and the even worse news is I’m still not going back.’ And about that point, Kuralt came along.”

No matter how rough things got, Welsch was prepared to stick it out. Of course, the CBS gig and some well-received books helped. But even without the nice paydays, he was adamant about avoiding city life and the halls of academia at all costs. What was so bad about the urban-institutional scene? In one sense, the nonconformist Welsch saw the counterculture of the ’60s he loved coming to an end. And that bummed him out. He also didn’t like being hemmed in by bureaucratic rules and group-think ideas that said things had to be a certain way.

His chafing at mindless authority extended to the libertarian way he ran his classroom at UNL and the free range front lawn he cultivated in suburbia.

“I was a hippie in the ‘60s and I really got excited teaching hippies because they didn’t give a didly damn what the bottomline was. They just wanted to learn whatever was interesting. You didn’t have to explain anything. I never took attendance. I’d have people coming in to sit in on class who weren’t enrolled, and I loved that. I hated grades. Because I figured, you’re paying your money. I’m collecting the money and I deliver. Now, what you do with that, why should I care? It’s none of my business,” he said. “The guy at the grocery store doesn’t say, Now I’ll sell you this cabbage, but I want to know what you’re going to do with it.”

Welsch said the feedback he got from students made him realize how passionate he was about teaching. On an evaluation a student noted, “‘Being in Welsch’s class isn’t like being in a class at all. It’s like being in an audience.’ I asked a friend, ‘Is that an insult or a compliment?’ ‘Well, Rog, actually being in your class isn’t like being in a class or in an audience. It’s like being in a congregation.’ And I thought, Oh, man, that’s it — I’m a preacher, not a teacher. It really is evangelism for me.”

“By the ‘80s they (university officials) wanted to know how they were going to make money out of the popular classes I taught. I said, ‘I have no idea. It’s not my problem. All I’m doing is telling them (students) what I know.’ So, there was that.”

Then there was the matter of UNL selling out, as he saw it, its academic integrity to feed the ravenous and untouchable football program, which he calls “a cancer.”

“I was and still am extremely disillusioned with the university becoming essentially an athletic department. Everything else is in support of the athletic department. And that breaks my heart, because I love the university. There was that.”

But what really set him off on his rural idyll was the 1974 impulse purchase he made of his 60-acre farm. He bought it even as it lay buried under snow.

“So, I bought it without ever really seeing the ground, but it was exactly what I wanted. I loved the river. I loved the frontage on the river. Then spring came and the more the snow melted…it was better than I thought….There are wetlands and lots of willow islands. The wildlife is just incredible. We’ve had a (mountain) lion down here and wolves just north of here.”

He used the place as a retreat from the city for several years. Each visit to the farm, with its original log cabin house, evoked the romantic in him, stirring thoughts of the people that lived there and worked the land. “That’s what I love about old lumber…the ghosts.” By the mid-’80s, he couldn’t stand just visiting. He wanted to stay. “I told Linda, ‘One of these days you’re going to have to send the highway patrol out, because I won’t come home. I can’t spend the rest of my life wanting to be here and living in Lincoln.’” Their move to the farm “really wasn’t so much getting away from anything as it was wanting to get out here.”

Then, too, it’s easier to be a bohemian in isolation as opposed to civilization.

“My life is a series of stories, so I have to tell you a story,” he said. “In my hippie days, I really got interested in wild plants and wild foods. As part of my close association with Native Americans, I was spending a lot of time with the Omahas up in Macy (Neb.). I was learning a lot of things from the Indians and, well, I was bringing home a lot of plants that I wanted to see grow, mature, go to seed and become edible. Milkweed and arrowhead and calimus. I got more and more into it. I loved the sounds and flowers and foods coming from my yard.

“One day, I come home to find a notice on my door that my lawn’s been condemned and I have six days to remove all ‘worthless vegetation.’ So, I invite the city weed inspector over to show me what’s worthless. He said, ‘OK, what about that white stuff over there?’ He didn’t even know the names of the plants. And I said, ‘Well, we had that for lunch.’ ‘How ‘bout that?’ ‘That’s supper.”

Welsch said, “As I started looking at this, I found out people were nuts. Anything over six inches high in Lincoln was a weed. The county weed board was spraying both sides of all county roads with diesel fuel and 24D. That’s essentially Agent Orange. They were laying waste to everything. Strawberries, arrowhead, cattails. So, I ran for the weed board on a pro-weed ticket. About this same time, Kuralt was coming through Nebraska. He asked somebody if anything going on in Nebraska might make a good story for his On the Road series. And whoever he asked, God bless ‘em, said, ‘Yeah, there’s a crackpot in Lincoln…’ So, Kuralt called me up and came over to the house with his van and his crew, which eventually became my crew. We sat down and had a huge weed salad and walked around and talked about weeds. And he had me on his On the Road. Well, then over the years every time he came through Nebraska he stopped. I kept a file of any stories I thought were interesting that he might use. That was my way of luring him to Lincoln.”

Charles Kuralt

The two men became fast friends and colleagues.

“We always went out to eat and drink. He loved to drink and I do, too. We would just have a good time. He used me for six more On the Road programs, for one thing or another. I tried to then steer him to other things — the jackalope in Wyoming and stuff like that. We got to be really good friends. When he started hosting Sunday Morning, he asked me to watch the show. He called me up and told me he wanted to bring the culture of New York City to towns like Dannebrog.”.

By the time Kuralt next passed through Nebraska to see Welsch, the author was giving a talk before a gathering of the West Point, Neb. chamber of commerce. What Kuralt heard helped him change the course of Sunday Morning and Welsch’s career. “He walked in the back of the room and listened to the program. We drove back to my place and he said, ‘You know, you said about 13 things we could use on Sunday Morning. What we need to do is to take the culture of a little town like Dannebrog and show it to New York City. So, that’s essentially how we got together. He originally thought about doing Postcards from America, where he had somebody (reporting) in every state. It got to be too expensive. I had six or seven years all by myself (with Postcards from Nebraska) before they added Maine. Then, by the time he went off the road, he gave me his old crew. They were like family. It was a great 13 years I was on that show. We had an awful lot of fun.”

Two years into Postcard, Welsch said Kuralt confided, “I thought we’d be lucky to get six stories out of Nebraska.” Ultimately, Welsch said, “we did over 200.”

What Welsch found in the course of, as he describes it, “my rural education,” and what he continues discovering and sharing with others, is a rich vein of human experience tied to the land, to the weather and to community. He’s often written and spoken about his love affair with the people and the place.

When friend and fellow Lincoln High classmate Dick Cavett asked him on national television — Why do you live in a small town? — Welsch replied: “In Lincoln academic circles everybody around me is the same. They’re all professors. In suburbia, everybody pretty much has the same income. But in Dannebrog, I sit down for breakfast and converse with the banker, the town drunk, the most honest man in town, a farmer, a carpenter and my best friend.” What Cavett and viewers didn’t know is Welsch was talking about his best friend Eric, who’s “been all those things. That private joke aside,” Welsch added, “the spirit of what I said is the truth.”

In his book It’s Not the End of the Earth, But You Can See it from Here, Welsch opines: “I like so many writers…have come to appreciate the power of what seems at first blush to be some pretty ordinary folks doing some pretty ordinary things. There is a widespread perception that small town life moves without color, without variety, without interest…but that has certainly not been my experience. My little town is like an extended family. There are my favorite uncles. A mean cousin or two. Some kin I barely see and do not miss. And some I can never get enough of.” It took leaving the city for the small town to find “the variety I love so much. The American small town seethes with ideas and humor, with friendship and contention, with wit and warmth, with silliness and depravity.”

He finds among the people there an inexhaustible store of knowledge to draw from, both individually and collectively, whether in the stories they tell or in the jokes they crack or in the observations they make. “It amazes me how much people out here know,” he said. “I came to love the land and its river so much. I was drawn inexorably to this rural countryside. But the land was the least of it. The real attraction…is the people. As I got to know the people in town, it just really blew me away. I love the people. It’s a cast of characters.”

“When I did It’s Not the End of the Earth I got mail from everywhere, with people saying, ‘I know what town you’re talking about…I live there in Pennsylvania,’ or, ‘I was in that same Texas town you write about.’ It’s the same cast of characters everywhere.” His characters may be fictional, but they’re extracted from real life. “There is no CeCe, no Slick, no Woodrow, no Lunchbox…and yet, I hope you will recognize them because they are not only people I have known, they are people you have known…In fact, if you are at all like me, they are people you have been.”

As he found out long ago in his folklore studies, there is a beauty, a charm and a value in the common or typical, which, as it turns out, is not common or typical at all. Like any storyteller, his joy is in the surprises he finds and gives to others.

“It’s not just me being surprised, but the pleasure I take in surprising other people,” he said. “I like to tell them, ‘Hey, guess what?’ And there are so many surprises. Every week out here when we turn on television to listen to the weather, there’s a new record set — record highs, record lows, record change, record snowfall, record draught. That means we don’t know anything yet. We haven’t the foggiest notion what this place is like. We still don’t know what the parameters are of this place. And as long as it keeps amazing me like that…”

The amazing stories he compiles keep coming. Like the woman who left an elegant life behind in Copenhagen to keep house for two bachelor farmers in their dirt-floor dug-out. Or the American Indian who witnessed the Wounded Knee massacre. Or the children that perished on their way home from school in the Blizzard of ‘88.

By now, Welsch is not quite the oddity he was when he first arrived in Dannebrog, an historical Danish settlement of about 265 today. Ensconced at a table in the Whisky River Bar and Grill, he’s just that loud, funny fella who cultivates stories.

“Up here at the bar, whenever people start to tell stories, I start doing like this,” he said, gesturing for a pen and napkin, “because they know I’m going to jot them down. Eric, who used to run the bar, said, ‘Welsch, everybody hears these stories, but you’re the only one who writes them down, takes them home and sells them.’” Welsch likes to tell the story of the time he and Linda were bellying up at the bar with a couple locals, when they asked, “‘How do you make a living writing?’ And I said, ‘Well, Successful Farmer pays me for the article and Essence pays me $2 a word…’ And one of them said, ‘You mean, each time you say — the — they pay you $2? And Linda said, ‘Well, he can use the same words over and over, but he has to put them in a different order every time.’” That’s when it dawned on Welsch, “Oh, God, that’s all I’m doing. Same damn words — different order.”

He remains a suspect figure all these years later. “To a lot of people in town, I’m still the professor, writer, outsider, eccentric. There’s still people that say, ‘Is that all he does is write?’” He’s used to it by now. This son of a factory worker and grandson of sugar beat farmers long ago set himself apart.

His initiation as country dweller was complete once he fell head over heels for a tractor. A 1937 Allis Chalmers WC to be precise. Many vintage models sit in a shed on his farm. He tinkers, toils and cusses, refurbishing engines and discovering stories. Always, stories. He’s penned several books about his tractor fetish.

“On an Allis, there’s a piece of braided cloth between the framework and gas tank to prevent friction and wear. I was taking apart a tractor and it was obvious somebody soldered the gas tank before and hadn’t put back the cloth. What they had done was take a piece of harness and put it in there. What that meant was a farmer working on it looked on the barn wall and made a decision: ‘I’m not going to use that harness again; horses are done; you’re now in the tractor age.’ To me, it said a world of things, and tractors are that way. I’ve still got the harness.”

Welsch feels he only gained the respect of some townies when he “admitted total ignorance” as a tractor hack. “No longer was I Professor-Smart-Ass. I was the dumb guy who didn’t know shit. I’d bring in my welding. I’d ask how to adjust a magneto. They were showing the professor…the guy from the city. That put me in touch with people here in town I never would have known. There was a connection…”

Perhaps no connections he’s made for his work mean more to him than do his ties with the Omaha, Pawnee and Lakota tribes. He said his experiences with them have “changed my life. What amazes me is that the culture is still alive. They’ve maintained it in the face of unbelievable pressure and deliberate efforts to destroy it, and yet it’s still there and they’re still willing to share it. That, to me, is astonishing. It’s being able to go to another country and another world within striking distance of Omaha that has different ideas about what property is and what time is and what generosity is and what family is.” His adoption by members of the Omaha and Lakota tribes has given him large extended tribal families. He treasures “the brotherhood and the closeness of it. Maybe because I was an only child.”

A trip to Greenland gave him a similar appreciation for the Innuits. He hopes one day to write a book about his “love” for the Arctic country and its people. It used to be he wrote books on contract. Not anymore. “You’re really obligated then to write the book the publisher wants. The books I’m doing now are so idiosyncratic and so personal that I want to write the book I want.” Besides, he said, “everybody loves to hear stories,” and he’s got a million of them.

Welsch knows how rare and lucky he is to be doing “exactly what I want to do. So much of my life is just unbelievable fortune. My daughter Antonia said I belong to The Church of Something’s Going On. I really believe there is. That’s about as close as I come to dogma.”

Related Articles

- Review: The Language of Trees (bookingmama.blogspot.com)

- Do Not Miss Get Low (observer.com)

- Folktexts: A library of folktales, folklore, fairy tales, and mythology, page 1 (pitt.edu)

- Monowi, Nebraska, USA (presurfer.blogspot.com)

After whirlwind tenure as Poet Laureate, Ted Kooser goes gently back to the prairie, to where the wild plums grow

This is the second story I wrote about poet Ted Kooser. It followed the first one I did on him by several months. That earlier story is also posted on this site. This second profile appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com) and nearer the completion of his duties as U.S. Poet Laureate. He’d enjoyed the position and the opportunities it afforded to spread the art of poetry around the nation, but as the article makes clear, he was also relieved he would soon be leaving that very public post and returning to his quiet, secluded life and the sanctuary of home.

After whirlwind tenure as Poet Laureate, Ted Kooser goes gently back to the prairie, to where the wild plums grow

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Late spring in Seward County will find the wild plums Ted Kooser’s so fond of in full bloom again. If he has his way, the county’s most famous resident will be well ensconced in the quiet solitude he enjoys. Once his second term as U.S. Poet Laureate is over at the end of May, he returns to the country home he and his wife share just outside the south-central village of Garland, Neb., tucked away in his beloved “Bohemian Alps.” It’s served him well as a refuge. But as a historical personage now, he’s obscure no more, his hideaway not so isolated. It makes him wonder if he can ever go back again to just being the odd old duck who carefully observes and writes about “the holy ordinary.”

When named the nation’s 13th Poet Laureate, the first from the Great Plains states, his selection took many by surprise. He wasn’t a member of the Eastern literary elite. His accessible poems about every day lives and ordinary things lacked the cache of modern poetry’s trend toward the weird or the unwieldy.

“I knew in advance there would be a lot of discontent on the east coast that this had happened. I mean — Who’s he? — and all that sort of thing,” he said. “If it had been given to me and I had failed it would have really been hard. So I felt not necessarily I have to do it better than anyone else but that I really needed to work on working it. It’s really been seven-days-a-week for 20 months now. And I think I have had a remarkable tenure.”

The fact he pledged to do “a better job than anyone had ever done before” as Laureate, said partly out of a pique of regional pride, set him up for failure. By all accounts, though, he’s been a smashing success, taking The Word with him on an evangelical tour that’s brought him to hundreds of schools, libraries, museums, book clubs, writing conferences and educational conventions.

No less an observer than Librarian of Congress James Billington, Kooser said, told him he’s “probably been in front of more people than any other Laureate, at least during his tenure. So, that counts for something.”

Kooser wanted to connect with a public too long separated from the written word. To reverse the drift of poetry away from the literay elite and return it to The People. Swimming against the tide, he’s managed to do just that with the stoic reserve and grim resolve of a true Midwesterner. No figurehead Laureate, he’s a working man’s Poet, sticking to an itinerary that’s seen him on the road more than at home for nearly two years. “I can’t remember where I’ve been and when,” he said recently.

For a shy man who “really prefers to be at home,” the thought of coming out of his shell to make the rounds as Laureate seized him with panic.

“At first, I didn’t think I could do it. Looking down the line right after it happened I thought, No way are you going to be able to be that public a person. I’ve always been kind of an introvert and it’s always been very difficult for me to get up in front of groups of people,” he said. “But I decided I would throw myself into it and make myself do it. I learned how to do that and I’m much more comfortable now after doing hundreds of things, although I’m still nervous.”

He estimates he’s appeared before some 30,000 people as the Laureate.

Much as a post-Sideways Alexander Payne expressed a desire to immerse himself in the unseen depths of a new film, a process he likens to “scuba diving,” Kooser craves a time when he can once more lose himself on the road less traveled.

“Now of course my impulse is, as of the end of May, to start retreating back into that very comfortable introversion that I’ve always loved,” he said.

His 2004 Laureate appointment and 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry brought the world to his quiet country home, if not literally to the doorstep, then virtually there via requests for interviews, readings and appearances of one kind or another. He still gets them. The fact he’s obliged many of these entreaties says much about the man and his avowed mission to bring poetry to the masses.

“My principal goal is to show as many people as I can who are not now reading poetry that they’re missing out on something,” he’s said.

His honest, pinched, Presbyterian face, set in the detached, bemused gaze of a portrait subject, is familiar as a result of his weekly newspaper column, “My American Poetry.” The column, the primary vehicle he chose to promote poetry, appears in hundreds of papers with a combined readership of some 11 million. Not that the townies in and around Garland didn’t already recognize him. He’s only reminded of his celebrity when he puts on a tie for some fancy event or is spotted in a public place, which happens in Omaha, Lincoln or more distant spots, like Washington, D.C., the home of the Laureate’s seat, the Library of Congress, where a 3rd floor office is reserved for him. Not that he uses it much.

Besides the phone calls, e-mails and letters he wades through, there’s the more mundane perhaps but still necessary chores to be done around his acreage. Fallen branches to pick up. Dead trees to bring down. Repairs to make. Dogs to feed and water. Distractions aplenty. It’s why he must get away to get any writing done. Yes, there’s sweet irony in having to find an escape from his own would-be sanctuary.

“We have a lovely place and all that, but the problem’s always been that when I’m sitting there in my chair at home with my notebook I’m constantly noticing all the things that need to be done” he said. “So getting away from that is going to be nice. I’ve bought an old store building in Dwight (Neb.). It’s about 10 miles from where we live. It’s a thousand square feet. One story. It’s been a grocery store and various things and I’m fixing it up as a sort of office. In the front room I have a desk and bookshelves and in the second room I have a little painting studio set-up.

“Nobody in Dwight’s going to bother me. I’m really going to try and figure out having a work day where I would go up there at eight in the morning and stay till five and see what happens. Paint, write, read books. And then go back.”

The demands of his self-imposed strict Laureate schedule have seriously cut into his writing life. With a few weeks left before he can cut the strings to the office and its duties, he’s resigned to the fact his writing output will suffer “for awhile” yet, but confident his return to productivity “is gradually going to come about.”

He’s already whetting his appetite with the outlines of a new project in his head. “I’ve been thinking about a little prose book I might like to do in which I would go to my building in Dwight and sit there in the middle of that little town of 150 or 200 people and read travel literature and write about armchair travel all over the world from Dwight, Neb. It’d be a book like Local Wonders (his 2000 work of prose), but I’d be sitting there daydreaming about Andalusia, you know. I don’t like to travel, but that might be a sort of fun way of doing it…learning about the world.”

He may also keep busy as general editor of an anthology of poems about American folklore to be published by the Library of Congress. Kooser originally broached the project with the Library soon after being installed as Laureate.

Then there’s his ongoing column, which he’s arranged to have continue even after he’s out of office. The column, offered free to newspapers, supports his strong belief poetry should be inclusive, not exclusive. He hit upon the idea for it along with his wife, Lincoln Journal Star editor Kathleen Rutledge.

“Kathy and I talked for years and years about the fact poetry used to be in newspapers and how do you get it back,” he said.

A column made sense for a poet who describes himself as “an advocate for a kind of poetry newspaper readers could understand.” Making it a free feature got papers to sign on. He said the number of papers carrying “My American Poetry” is “always growing” and one paper that dropped it was pressured to resume it after readers complained. He’s most pleased that so many rural papers run the column and that perhaps schools there and elsewhere use the poems as teaching tools.

|

|

Karl Shapiro, center, with students in Nebraska nearly a half century ago. Left is Poet Ted Kooser .(Reprinted with permission from Reports of My Death by Karl Shapiro, published by Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, a division of Workman Publishing.) |

Besides the feedback he gets from readers, the poets whose work he features also get responses. “And, of course, the poets are tremendously excited. They’re in front of more readers than they’ve ever been in front of in their lives,” he said. It’s all part of breaking down barriers around poetry.

“The work that is most celebrated today is that work that needs explaining…that’s challenging. The poetry of the last century, the 20th century, was the first poetry ever that had to be taught. That had to be explained to people,” he said in an April 24 keynote address before the Magnet Schools of America conference at Qwest Center Omaha. It began “when the great Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs of contemporary poetry fell upon poetry in the persons of Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot.”

This drift toward a literary poetry of “ever-more difficulty” and “elitism” continues to this day, limiting its appeal to a select circle of poets, academics and intellectuals. “The public gets left out,” he said. He has a different audience in mind. “I’m more interested in reaching a broad, general audience. I’m in the train of those poets (in the tradition of William Carlos Williams) who always believed in wanting to write things that people could understand.” Rather than a focus on form, he said, “I believe in work that has social worth.”

As a missionary for a common poetry that really speaks to people, his newspaper column amounts to The Ted Kooser Primer for Poetry Appreciation. “I have felt like a teacher all through it,” said Kooser, a poetry instructor for select graduate students at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “Basically with the column I’m doing what a teacher would do. I’m trying to teach by example…what poetry can offer.”

He realizes his insistence on realism and clarity rankles the established order.

“I try pretty hard to make it understandable,” he’s said of his own work. “That sort of thing runs against the grain in poetry right now. I’m very interested in trying to convince people that poetry isn’t something we have to struggle with.”

Kooser harbors no allusions about making a sea change on the poetry scene.

“I think by the time I’m done at the end of May, when my term as Poet Laureate is over, I will have shifted American poetry about that far,” he said, his clamped hands moving ever so slightly to mimic those of a clock. “And the minute I’m out of office there’ll be a tremendous effort to get back where it was.”

It’s all about making converts. “Yeah, and, you know, they’re only one at a time. but for the one person that comes up there are others in the audience that are feeling the same way,” he said. “I don’t know that it’s my poetry that’s making the difference. This is not something I’m doing intentionally, but in looking at myself from over on the side I think have de-mystified the process. You know, it’s really about working hard and learning to write. There’s no magical thing I have that nobody else has. It’s just the fact I’ve been writing poetry for 50 years and I’ve gotten pretty good at it. And I think people like to hear there’s nothing really mysterious about it.”

Part of the exclusion people feel about poetry, he said, stems from how it’s taught in schools. It’s why soon after getting the Laureate he made a point of speaking at the National Conference of Teachers of English, “an organization on the front line for expanding the audience for poetry,” yet one ignored by his predecessors.

“I wanted to go there because I thought, Here are the people who have all the experience teaching poetry and usually where poetry goes wrong is in the public schools. It’s taught poorly. It discourages people, and so they never know to read it. And so I figured these teachers are really the prime teachers — any teacher who will pay his or her own way to a convention is pretty serious about teaching — and would have the really good ideas about how to teach poetry. And, as a matter of fact, there were a lot of ideas that came out of it. Mostly enthusiasm, really, and encouragement and that sort of thing.”

He never underestimates the power of “a great big dose of encouragement, no matter how bad the students’ work is, because I was one of those students,” he said. Growing up in his native Ames, Iowa, his earliest champion was his mother, the woman who taught him to see and to appreciate the world around him — the local wonders so to speak, and to not take these things for granted. Another early influence was an English teacher named Marian McNally. In college, teachers Will Jumper and Karl Shapiro, the noted poet, inspired him.

As Laureate Kooser’s embraced diversity in poetry. A 2005 program he organized in Kearney, Neb. saw him share the stage with an aspiring poet, a cowboy poet, a romantic poet, a performance poet and a fellow literary poet. Whatever the form or style, he said, poetry provides a framework for “expressing feelings,” for gaining “enlightenment,” for “celebrating life” and for “preserving the past.”

When he battled cancer eight years ago he didn’t much feel like celebrating anything. “And then…I remembered why I was a writer. That you can find some order and make some sense of a very chaotic world by writing a little poem. People need to be reminded there are these things out there that they can enjoy and learn from — and there might be something remarkable in their own backyard — if they would just slow down and look at them. To really look at things you have to shut out the thinking part and look and just see what’s there. It’s reseeing things”

True to his openness to new ideas, he’s agreed to let Opera Omaha commission a staged cantata based on his book The Blizzard Voices, a collection of poems inspired by real-life stories from the 1888 blizzard that killed hundreds of children in Nebraska, Iowa and Kansas. Adapting his work is composer Paul Moravec, winner of the 2005 Pulitzer for Music. The March 2008 production will premiere at the Holland Performing Arts Center and then tour. Recording rights are being sought.

For Kooser, who once adapted his Blizzard poems for a Lincoln Community Playhouse show, the possibilities are exciting. “I met with him (Moravec) and I liked him immensely and so I decided I would trust him to do anything he wanted to do. I think the idea of a blizzard and the kind of noise you could associate with it could be really interesting.”

Music-poetry ties have long fascinated Kooser, who hosted a program with folk musician John Prine. The March 9, 2005 program “A Literary Evening with John Prine and Ted Kooser,” was presented by the Poetry and Literature Center at the Library of Congress in D.C. The program included a lively discussion between the songwriter and the poet as they compared and contrasted the emotional appeal of the lyrics of popular songs with the appeal of contemporary poetry.

“I’ve been following John Prine’s music since his first album came out and have always been struck by his marvelous writing: its originality, its playful inventiveness, its poignancy, its ability to capture our times,” Kooser said. “For example, he did a better job of holding up the mirror of art to the ’60s and ’70s than any of our official literary poets. And none of our poets wrote anything better about Viet Nam than Prine’s ‘Sam Stone.’ If I could write a poem that somebody could sing and make better for being sung, that would be great.”

In anticipation of the Opera Omaha cantata, the University of Nebraska Press has reprinted Kooser’s Blizzard Voices in paperback.

Whoever’s named the next Laureate will get a letter from Kooser. If his successor asks for advice he will say to be sure to avoid talking politics. If Kooser had responded to a national reporter’s question two years ago about who he voted for in the presidential race, he’s sure he’d still be dogged by that admission now. “Instead,” he said, “I’ve gotten to talk about poetry…the job I was hired to do.”

Related Articles

- Author Wins National Poetry Award (nebraskapress.typepad.com)

- Poetry Pairing | August 19, 2010 (learning.blogs.nytimes.com)

- Poet Laureate Announced: William S. Merwin Named 17th U.S. Poet Laureate (huffingtonpost.com)

- Billy Collins: Horoscopes For the Dead (everydayfeatsofcourage.com)

- Off the Shelf: Valentines by Ted Kooser (nebraskapress.typepad.com)

Keeper of the Flame: Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner Ted Kooser

Ted Kooser was already well into his term as U.S. Poet Laureate and had recently been awarded the Pulitzer Prize when I wrote two stories about him. This is the first. It appeared in the New Horizons, and it ‘s based on an interview I did with him at his home in Garland, Neb. Whenever I interview and profile a writer, particularly one as skilled as Kooser, I feel added pressure to get things right. He helped make me feel comfortable with his amiable, homespun way, although I never once forgot I was speaking to a master. The subsequent piece I did on him is also posted on this site.

Keeper of the Flame: Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner Ted Kooser

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Forget for the moment Ted Kooser is the reigning U.S. Poet Laureate or a 2005 Pulitzer Prize winner. Imagine he’s one of those quixotic Nebraska figures you read about. A bespectacled, bookish fellow living on a spread in the middle of nowhere, dutifully plying his well-honed craft in near obscurity for many years. Only, fame has lately found this venerable artist, who despite his recent celebrity and the rounds of interviews and public appearances it brings, still maintains his long-held schedule of writing each morning at 4:30. Away from the hurly-burly grind, the writer’s life unfolds in quiet, well-measured paces at his acreage home recessed below a dirt road outside Garland, Neb. There, the placid Kooser, an actual rebel at heart, pens acclaimed poetry about the extraordinariness of ordinary things.

Once you get off I-80 onto US 34, it’s all sky and field. Wild flowers, weeds and tall grasses encroach on the shoulders and provide variety to the patches of corn and soy bean sprawled flat to the horizon. The occasional farm house looms up in stark relief, shielded by a wind break of trees. The power lines strung between wooden poles every-so-many-yards are guideposts to what civilization lies out here.

Kooser’s off-the-beaten-track, tucked-away place is just the sort of retreat you’d envision for an intellectual whose finely rendered thoughts and words require the concentration only solitude can provide. More than that, this sanctuary is situated right in the thicket of the every day life he celebrates, which the title of his book, Local Wonders, so aptly captures. In his elegies to nature, to ritual, to work, and to all things taken for granted, his close observations and precise descriptions elevate the seemingly prosaic to high art or a state of grace.

The acreage he shares with his wife Kathy Rutledge includes a modest house, a red barn, a corn crib, a gazebo he built and a series of tin-roofed sheds variously containing a shop for his handyman work, an artist’s studio for his painting and a reading salon for raiding bookcases brimming with volumes of poetry and literature.

The pond at the bottom of the property is stocked with bluegill and bass.

His dogs are the first to greet you. Their insistent barking is what passes for an alarm system in these rural digs. Kooser, 66, comes out of the house to greet his visitors, looking just like his picture. He’s a small, exact man with a large head and an Alfred E. Newman face that is honest, wise and ironic. He has the reserved, amiable, put-on-no-airs manner of a native Midwesterner, which the Ames-Iowa born and raised Kooser most certainly is.

Comfortably and crisply outfitted in blue jeans, white shirt and brown shoes, he leads us to his shed-turned-library and slides into a chair to talk poetry in his cracklebarrel manner. A pot-bellied stove divides the single-room structure. The first thing you note is how he doesn’t play off the lofty honors and titles that have come his way the last two years. He is down to earth. Sitting with him on that June afternoon you almost forget he’s this country’s preeminent poet. That is until he begins talking about the form, his answers revealing the inner workings of a genuine American original and master.

Kooser, who teaches a graduate-level tutorial class in poetry at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, patiently responds to his visitors’ questions like the generous teacher he is. His well-articulated passion for his medium and for his work, a quality that makes him a superb advocate for his art, are evident throughout a two-hour conversation that ranges from the nature of poetry to his own creative process.

So, what is poetry?

“I like to think it is the record of a discovery. And the discovery can either be something in your environment or something you discover in the process of writing, like in new language. You basically record that discovery and then give it to the reader. And then the reader discovers something from it,” he said. “There’s a kind of kaleidoscope called a taleidoscope. It doesn’t have the glass chips on the end. It has a lens and I turn it on you and however ordinary the thing is it becomes quite magical because of the mirrors. And that’s the device of the poem. The poet turns it on something and makes it special and gives it — the image — to the reader.”

There is a tradition in poetry, he said, of examining even the smallest thing in meticulous detail, thereby ennobling the subject to some aesthetic-philosophical-spiritual height. It’s one of the distinguishing features of his own work.

“The short lyric poem very often addresses one thing and looks at it very carefully. That’s very common. I guess I’m well known for writing poems about very ordinary things. There’s a poem in my latest book about a spiral notebook. Every drug store in the state has a pile of them. Nothing more ordinary than that. I’ve written poems about leaky faucets and about the sound a furnace makes when it comes on and the reflections in a door knob. They’re all celebrations in some sense. Praise” for the beauty and even the divine bound up in the ordinary.

His Henry David Thoreau-like existence, complete with his own Walden’s Pond, feeds his muse and gives him a never-ending gallery to ponder and to convey.

“I like it out here. I like being removed from town. I like it because it’s quiet. For instance, I have a poem in my book Weather Central about sitting here and watching a Great Blue Heron out here on the pond. And there are many poems like that. There’s another one in that same book called A Hatch of Flies about being down in the barn one morning very early in the spring and seeing a whole bunch of flies that had recently hatched behind a window.”

The rhythms of country living complement his unhurried approach to life and work. He waits for inspiration to come in its own good time. When an idea surfaces, he extracts all he can from it by finding purity in the music and meaning of language. Words become notes, chords and lyrics in a kind of song raised on high.

“I never really have an idea for a poem,” he said. “I’ll stumble upon something and it kind of triggers a little something and then I just sort of follow it and see where it goes. I always carry a little notebook. If I see something during the course of the day I want to write about, I make a note of it.”

Another element identifying Kooser’s work is the precision of his language and his exhaustion of every possible metaphor in describing something. The rigor of poetry and of distilling subjects and words down to their truest essence appeals to him.

“I think there’s a kind of polish on my metaphors. I’m extremely careful and precise in the way I use comparisons. I wrote about that in my Poetry Repair Manual. How you really work with a metaphor. You just don’t throw it in a poem and let it go. You develop it and take everything out of it you can. With a poem, once it’s finished or it’s as finished as best as I can finish it, there isn’t anything that can be moved around. You can’t substitute a word for its pseudonym or its synonym. You can’t change a punctuation mark or anything like that without diminishing the effect,” he said. “Whereas, with prose, you can move a word around or change the sentence structure and it really doesn’t have that much of an effect on the overall piece. I like the fact poetry has to be that orderly and that close to perfect. I tend to be a kind of orderly type guy.”

Getting his work as close to perfection as possible takes much time and effort.

“I spend a lot of time revising my poems and trying to get them just right. A short poem will go through as many as 30 or 40 revisions before it’s done. Easily. I’m always trying to make the poems look as if they’re incredibly simple when they’re finished. I want them to look as if I just dashed them off. That takes revision itself. I’m always revising away from difficulty toward clarity and simplicity.”

So, how does he know when a poem is done?

“I think what happens is eventually you sort of abandon the poem. There’s nothing more you can do to make it better. You just give up. Rarely do you get one you think is really perfect. But that blush of success doesn’t usually last very long.”

A serious poet since his late teens, Kooser has refined his style and technique over a half-century of experimentation and dogged work.

“We learn art by imitation — painters, musicians, writers, everybody — by imitating others. So, the more widely you read, the more opportunities there are to imitate different forms and different approaches, and I tried everything I suppose,” he said. “You learn from the bad, unsuccessful poems as much as you learn from the good ones. You see where they fail. You see where they succeed. I’ve written the most formal of forms — sonnets and sestinas and ballads and so on, just trying them out, as you’d try on a suit of clothes.”

“I’ve come to my current style, which feels very natural to me,” through this process of trial and error and searching for a singular voice and meter and tone. “Somebody glancing at it would say, ‘Well, this is free verse.’ But it really is not free verse at all. I take a tremendous amount of care thinking about the number of syllables and accents in the lines. I might not have three accents in every lines, but the only reason I wouldn’t add another accent to a line of two is that it would seem excessive or redundant in a way.

“So, I never let the form dominate the poem. It’s all sort of one thing. And I think poems proceed from someplace and then they find their own form as they’re written. You let them develop. You let them fill their own form.”

Being open to the permutations and rhythms of any given poem is essential and Kooser said his routine of predawn writing, which he got in the habit of while working a regular office job, feeds his creativity and receptivity. “It’s a very good time for me to write. It’s quiet. You mind is refreshed. I’m a poet very much devoted to metaphor and rather complex associations,” he said, “and they tend to rise up at that time of day. I think what happens is as you come out of sleep your mind is trying make connections and sometimes some really marvelous metaphors will arise. By the end of the day, your head is all full of newspaper junk and stuff.”

All that sounds highly romantic, but the reality and discipline of writing every day is far from idyllic. Yet that’s what it takes to become an artist, which reminds Kooser of a story that, not surprisingly, he tells through metaphor.

“A friend of mine had an uncle who was the tri-state horse shoe pitching champion three years running and I asked — ‘How’d he get so good at it? — and my friend said, ‘Son, you’ve got to pitch a hundred shoes a day.’ And that’s really what you have to do to get good at anything. And I tell my students that, too: ‘You’ve got to be in there pitching those hundred shoes every day.’ Often times, in the process of writing, the really good things happen. That’s why you have to write every day. You have to be there, as the hunters say, ‘when the geese come flying in.’”

As most writers do, Kooser came to his art as an eager reader. He grew up in a Cold War-era home where books were abundant. He became a fixture at the local public library in Ames. His mother, who had some college and was a voracious reader, encouraged young Ted. But what really drove him, more than the Robert Louis Stevenson books he devoured, was his sense of being an outsider. He was a puny kid who didn’t mesh with the cliques at school. But in writing he found something of his own. A key book in his early formation as an aspiring writer was Robert McCloskey’s novel Lentil.

“It’s about a boy in a small town who doesn’t fit it very well. He’s not an athlete. He can’t sing. Then he teaches himself to play the harmonica. When a very important person from the town returns home, the band is all assembled at the depot, the banners are all hung out and a parade is planned down main street. But the guest has an enemy who gets up on the depot roof with a lemon, and when the band gets ready to play, he slurps this lemon and the band can’t blow their horns. But Lentil can play his harmonica and by saving the day he gets to ride with the special guest in the parade. The last line of the poem is, ‘So you never know what will happen when you learn to play the harmonica. And that really is a seminal story for me. I identified with that kid. And this poetry business is really like the harmonica. This was my thing to do. And so, for me, the lesson was, You never know what will happen when you learn to write poetry.”

Besides writing, Kooser was “into hot rods.” He built one car himself and built another one with a friend. It was inevitable he would combine both passions.

“I was writing these Robert Service-type ballads about auto races. I wrote a long one about a race and some of my friends sent it to a slick teen magazine called Dig. It was nothing I would have ever done myself. I never was one to really put myself forward in any way. But they sent it in, and it was published, much to my surprise.”

Between the buzz of his first published story, the strokes his teachers gave him and the emerging Beat Poetry scene he embraced, Kooser was sold on the idea of being a poet despite and, indeed, because of the fact it was so far afield from his proletarian roots. Making his mark and defying convention appealed to the non-conformist in Kooser. It was his way of standing apart and being cool.

“I wanted to be a poet right from the time I was 17 or 18. That was really my driving force. It was the idea of being different and interesting. I wanted to be on the outside looking in. It had a lot to do with girls, frankly. I came from an extremely plain, ordinary, middle class background and I wanted to set myself apart from that. Who knows how that works psychologically? My mother was very devoted to me and had very conventional ideas, and it may have been my attempt to separate myself from her. And to this day, when I become sort of reabsorbed into the establishment, as if I had ascended in class to some other level, I feel slightly uncomfortable and rebellious. I think that to be successful as an artist you have to be on the outside of the general order — observing it.”

In his wife, Kathy Rutledge, whom he met in the ‘70s, he’s found a kindred spirit. A child of the ‘60s, she was caught up in the fervor of the times. Now the editor of the Lincoln Journal Star, she shares his love of writing and is his gentle reader.

“She helps me with my writing. She’s a very good reader of my work. She’s a brilliant woman. She knows terms for the English language I don’t understand.”

He finds it ironic a pair of iconoclasts have ended up in such mainstream waters. She as a daily newspaper editor and he as “a celebrated poet” speaking to Kiwanis and Rotary Club meetings and giving college commencement addresses.

Besides his poetry and his insurance job, which he retired from a few years ago, Kooser’s been on the periphery of the academic circle. He’s taught night classes for years at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he earned his master’s.

Growing up in a college town, he gravitated almost as a matter of course to local Iowa State University, where he studied architecture before the math did him in. His literary aspirations led him into an English program that earned him a high school teaching certificate. He taught one year before moving onto UNL for grad studies. He was drawn by the presence of former U.S. Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize-winner Karl Shapiro, under whom he studied. When Kooser spent more time hanging out with Shapiro than working on his thesis, he lost his grad assistantship and was forced to take a real job. He entered the insurance game as a stop-gap and ended up making it a second career. It was all a means to an end, however.

“I worked 35 years in the life insurance business, but it was only to support myself to write. It was an OK job and I performed well enough that they kept promoting me. But writing was the important thing to me and I did it every morning, day in and day out. Writing was always with me. I’ve never not been writing.”

While his 9 to 5 job gave him scant satisfaction beyond making ends meet, it proved useful in providing the general, non-academic audience for his work he sought.

“The people I worked with influenced my poetry,” he said. “We all write toward a perceived community, I think, and I was writing for people in that kind of a setting. I had a secretary in the last years I was there, a young woman who’d read poems in high school but had no higher education, and I often showed her my work. I’d say, ‘Did it make any sense to you?’ and she’d say, ‘No, it didn’t.’ And I’d go home and work on it, until it did because I wanted that kind of audience. I would not refer to anything that would drive anybody to stop in the middle of the poem to go look it up in the encyclopedia. The experience of the poem shouldn’t be interrupted like that. I have a very broad general audience. I get mail from readers every day.”

A less obvious benefit of working as a medical underwriter, which saw Kooser reading medical reports filled with people’s illnesses, was gleaning “a keen sense of mortality.” “Poetry, to really work,” he said, “has to have the shadow of mortality carried with it, because that darkness is what makes the affirmation of life flower.”

These days, Kooser is working hard to help poetry bloom in America, where he feels “it’s really thriving” between the literary-academic, cowboy, hip hop and spoken word poets. “It’s so important to do a good job as Poet Laureate, as far as extending the reach of poetry, that I’ve largely set my own writing aside for now.” His post, which he sees as “a public relations job for the sponsoring Library of Congress and for poetry,” has him promoting the art form as a speaker, judge and columnist. His syndicated Everyday Poetry column is perhaps his most visible outreach program. He’s considering doing an anthology of poems about American folklore. He’s also collaborating with educators to distill their ideas for teaching poetry into a public forum, such as a website. “The teachers are really on the front line here. They’re the people who make or break poetry,” he said.

Then, as if reassuring his visitors he’s no elitist, he excuses himself with, “I’ve got to run up to the house — I’ve got a pheasant in the oven.” Yes, even the Poet Laureate must eat.

Related Articles

- Author Wins National Poetry Award (nebraskapress.typepad.com)

- Poetry Pairing | August 19, 2010 (learning.blogs.nytimes.com)

- Poet Laureate Announced: William S. Merwin Named 17th U.S. Poet Laureate (huffingtonpost.com)

- “Librarian of Congress James H. Billington today announced the appointment of WS Merwin as the Library’s 17th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry for 2010-2011.” and related posts (resourceshelf.com)

- Off the Shelf: Valentines by Ted Kooser (nebraskapress.typepad.com)

- Poetry Pairing | March 31, 2011 (learning.blogs.nytimes.com)

- After Years, Ted Kooser (objetsdevertu.wordpress.com)

- Billy Collins “Introduction to Poetry” (thenightlypoem.com)

Art Missionaries, Bob and Roberta Rogers and their Gallery 72

If you saw the odd little old couple on the street you would never guess they were serious art connoisseurs. But get them in their element, at a museum or at a gallery opening, and get them talking art, and then there would be no doubt that Bob and Roberta Rogers were much more than some stereotypical representation of narrow minded, buttoned down old fogies. Then you would see them for who they really were — savvy, sophisticated art collectors and dealers whose open minds saw them champion all sorts of edgy art. Together, they owned and operated perhaps the most respected private gallery in Omaha. They made their Gallery 72 a fixture on the local art scene. When Roberta died Bob carried on for a while on his own. Then his son John joined him. By the time Bob died, the gallery was fully in the hands of John, who moved the business to an emerging arts hub on Vinton Street in South Omaha. My story about the couple originally appeared in the New Horizons.

Art Missionaries, Bob and Roberta Rogers and their Gallery 72

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

For the longest time, Bob and Roberta Rogers of Omaha were models of conventionality. He did the 9 to 5 office routine. She stayed home to raise their two sons. Their lives revolved around work, family, home, church, school. Then, in middle age, a funny thing happened. The 1960s arrived with a bang and they found themselves drawn to the decade’s vital counter-culture movement.

Unlike most of their generation, who resisted the tumult, the Rogers embraced the era’s provocative art, film, music, literature. They were especially taken with the Pop Art scene and the groundbreaking work of artists like Andy Warhol. Their new found passion led to a whole new way of life. She began hanging out at Old Market head shops. He started breaking out of the corporate mold by opening a donut business. And although not artists themselves, they became ardent art admirers and collectors. So much so, they started their own gallery in 1972.

“We learned so much about art by just looking at it. We just got to looking. And we both got interested in doing something creative,” Roberta said in the sweet, meandering accent of her native Mississippi. “In both of our cases we were finally getting around to doing something we should have done when we were younger.”

Better late than never. Twenty-six years later their Gallery 72 at 2709 Leavenworth Street is a respected venue presenting and selling contemporary works by top American and foreign artists. They feel a life in art was somehow meant for them.

“I think this is to a certain extent something you almost get a calling for,” Roberta said. “What we wanted to do was to bring the kind of art people should be looking at and collecting in Omaha — really good contemporary art. That was our mission. I guess we wanted to be art missionaries, and any true missionary doesn’t think too much about the consequences or they wouldn’t become missionaries. It was awful tough getting started, but we survived through various ways and sundry miracles.”

Bob Rogers

Their mission has taken them far beyond their gallery walls. They have long been fixtures at local art shows. She has been a Joslyn Art Museum docent and a presenter of art educational programs at area schools. He has advised galleries, museums, corporations and private collectors. Their undying devotion to art has won them many admirers.

“A lot of people get into gallery work because they know a little bit about art and may have a good eye, but they still look on it as a business,” said Joslyn Art Museum registrar Penelope Smith. “Bob and Roberta look on it as a vocation. They really believe in the art they’re exhibiting and they really care about it.”

The couple has acquired a reputation as astute art appraisers, collectors and exhibitors as well as enthusiastic art lovers. Their contributions to the visual arts in Nebraska were recognized with the 1990 Governor’s Art Award.

“I don’t know of anybody within the state that has more personal passion for and commitment to art and artists,” said George Neubert, director of the Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery in Lincoln. Neubert, a sculptor, has shown at Gallery 72. “It’s a full range of support and nurturing they provide, whether it’s at one of their famous potlucks, where they gather together a wonderful strange mix of people interested in art, or whether it’s selling works to museums for their collections.”

Omaha painter Stephen Roberts notes the “very warm atmosphere” the Rogers extend to artists like himself and the fact “they show things they really love. I think sales are really secondary to them.”

Married 54 years, the Rogers are such stalwart partners in their life and vocation that you can’t think of one without the other. “I think it was fate that I met Bob,” Roberta said. “I’d had several young men that were interested, but they didn’t care for the same things that I liked. We just both liked the same things. We’ve always done nutty things.”

If nothing else, they prove appearances can be deceiving. A casual glance at their storefront gallery, across from St. Peter’s Catholic Church in downtown’s Park East area, suggests a curio shop. But on closer inspection it is a showplace whose spare neutral interior is a perfect backdrop for the paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures displayed there. The unassuming Rogers are Omaha’s mom and pop art missionaries all right, and so much more. These forever youthful codgers are full of surprises. She’s an effusive Southern sprite with a biting wit. He’s a gruff stoic curmudgeon with a stubborn free-spirit. Together, they’re quite a pair.

Their apartment above the gallery is a single-level New York-style loft whose tall windows overlook St. Peter’s. Nearly every available inch of space is covered by art from their extensive, eclectic personal collection. Book shelves bulge with volumes on art. A huge industrial cabinet and table double as a kitchen pantry and dining surface, respectively. Magazines and newspapers are strewn everywhere. Potted plants adorn one corner. It is a home resonating with the energy of lives lived well and fully.

Although slowed by age — he’s 79, she’s 83 — their intense feeling for art remains undiminished. To understand the depth of that feeling, one must return to when their lives were transformed. They credit their sons, John and Robert, with introducing them to the vital art scene emerging in the ‘60s. Robert attended the Kansas City Art Institute at the time.

“He came back and told us about all these exciting things going on,” Roberta said. “Those were the days when the modern old masters were struggling young artists.”

Innovative modern artists like Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg and Frank Stella “changed the history of art forever,” Bob said in the low, flat rumble he speaks in. Adds Roberta, “When I found out about people like Stella and Oldenburg and great foreign movies by Francois Truffaut and Federico Fellini and music by Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, and the Doors, it was like I was finally coming alive. It almost seemed like we were waiting for something to come along, and when we discovered all these wonderful things, we were ready. It seems like I had been just kind of existing up till then. As I tell people, I think I was really born in the ‘60s.”

Bob was equally inspired by the fervor of the times. “There was a tremendous amount of energy in America that we don’t have now,” he said. What many of their generation viewed as a threat, he and Roberta saw as an exciting new experience full of personal growth opportunities. Instead of rejecting youth, they followed their lead.

“In those days all the parents were screaming about ‘my children won’t talk to me,’ but I never felt we had that problem,” he said. “We never had a void in our relations. We let our sons educate us. They brought us into the 20th century.”

The Rogers, though, were hardly art neophytes. Each was brought up to appreciate the finer things. That mutual interest was a point of attraction when they met during World War II. But even after they married, circumstances left little time or money to pursue their shared passion.

She grew up in a series of Midwestern and Southern towns, moving with her family wherever her father’s civil engineering job with the Illinois Central Railroad took them. Her mother was an arts devotee and Roberta often accompanied her on cultural outings.

“My mother had friends who were artists, so I got a feeling for what they were trying to do. My mother recognized these things were necessary. She loved music. She loved the theater. And when we were in a place where we could go, why we went.”

Roberta’s many travels even brought her, as a teen, to Omaha, where she and her family lived during 1928-29. She attended Saunders School (since closed) and lived in the Austin Apartments near the Joslyn Castle. She recalls seeing Al Jolson in the first motion picture talkie, “The Jazz Singer,” at the Riviera Theater (now The Rose) and taking the streetcar to attend Saturday afternoon matinees as well as repertory plays at the now defunct Brandeis Theater.

Bob, an Iowa native, fed his artistic muse dabbling in theater at Northwestern University, where he majored in business administration to please his father, a sales manager at John Morrell meatpacking company.

“My father had a dream that I was supposed to carry on what he was doing,” he explains. “Well, he overlooked the fact that every human that’s born is different. His idea of what I should do in my life was 180 degrees from what I wanted to do, but you couldn’t tell your father that. If I could have kicked over the traces I would of got a job in the front-office of the Chicago Cubs baseball team. I was a baseball fanatic in those days. If that hadn’t of worked out I probably would have gone in the technical end of the theater in Chicago.”

But like a good son he followed his father’s wishes and obediently punched the clock at Morrell even though he felt stifled there. Then the war came and with it his active duty in the Army Quartermasters and eventually action in Europe. His stint in the service also led him to Roberta. It was while stationed at Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg, Miss. that their lives intersected in 1941.

“We were living in Gulfport at the time. My father had a little house up in the piney woods about 18 miles from the Gulf Coast. There was a place where soldiers with a weekend pass could get away from camp and swim and go to movies” Roberta recalls. “Every Saturday night the ladies in Gulfport had a dance at the community center. A band came over from Biloxi to play.

“They recruited all the young unmarried women in Gulfport to come. It was Labor Day weekend and most of the troops from Camp Shelby were over in Louisiana on maneuvers, and so it was one of the few times there were about as many men as there were women. And that’s how Bob and I got to talkin’ and all. I liked him. He was a nice quiet young man. As we got to know each other and visit more and all, why we just found out we had a lot of common interests.”

The only potential obstacle was their families’ diametrically opposed politics. Her people were staunch Democrats. His, dyed-in-the-wool Republicans. Fortunately, her father was a Northerner by birth and a Republican by nature. The match could go on.

After an 18-month engagement the couple married in 1943 in San Bernardino, Calif., near the training center Bob was assigned. After the war he resumed working for Morrell. It was around this time his father died, and as Bob says, “I really didn’t feel like I had to fulfill his dream anymore.”

He then went from job to job, searching for his niche, but always ending up frustrated. His job with a packaging services firm led the couple to Omaha in 1958. Soon he got fed up again and tried a drastic change.

“Bob was seeking. He felt getting into the donut business was really a creative kind of thing and so we started the Mr. Donut shops here in 1964. It took off pretty well but then after several years we began to have problems with getting good help,” she said. “Then Bob just asked one day, ‘What would you think of opening an art gallery?’ And I said, ‘I guess it would be okay.’ We both knew it was going to be an uphill battle with art in Omaha. But the boys were raised and we decided we could sink or swim or starve in an attic and start our own art gallery.”

Unlike today, galleries were rare then in Omaha. Still, there was no looking back. “Once the bug bites you, you’re bitten. That’s the way it is,” she said. They sacrificed everything for the project, opening in a strip mall on 72nd Street, hence the name.

“We pared our living expenses way down,” she said. “But it didn’t work out too well out there… and so we sold the house we were living in and we looked around for a building.”

They found the building they occupy now, formerly offices of the Association for the Blind, and after renovating it, re-opened the gallery in 1974. She said their mission has remained constant: “It was to show the best of contemporary art, because we live in a contemporary world. Another thing we felt was that the work had to be of museum quality. In all these years we’ve only had one show where everything in it was not of museum quality. And we’ve never gone into making a living off of crafts and jewelry. Just art. We felt like that would be lowering our standards.”

With the advent of area artist cooperatives, the gallery shows fewer local artists than in the past. The art market has also changed drastically since Gallery 72 opened. “Then you could get a good fine art print by the best artist for $150. Now that these artists have become so much better known their prints come out at $3000 or $4000 or $5000 each,” she said.

Three woodcuts the Rogers acquired years ago (by Francesco Clemente, William T. Wiley and Pat Steir) have risen in value many times over. “I sold a little bit of stock I had and with that and a few dollars Bob put in we got the three of them wholesale. They were real bargains. Any one of ‘em is way more valuable than the dividend would have been. And I feel like I’m getting a good dividend just because I look at ‘em all the time.”

Bob said the law of supply and demand accounts for such steep price increases. “There’s a limited amount of these things, and a ton of people who want it. People are always asking me, Do you think this will go up in value? Well, I never sell anybody art for an investment because there’s very little way you can tell for sure.”

Roberta said the true reward of art is not the money it brings, but the satisfaction it affords. “Art is something that when it gets in your blood, your mind, your being, it just adds so much to your life and how you feel about yourself. When you look at a piece of art you’ve got a relationship with this artist’s mind. It’s like a conversation. It says something to you, you say something back, and it becomes a visual dialogue.”

Bob, who makes all decisions concerning which artists to show, said too often people fret over the meaning of a work rather than just respond to it instinctually. “Don’t analyze anything,” he suggests. “If you went to the artist and asked him, he probably wouldn’t be able to tell you, or if he did, it’d be something he made up.”

For him, the best art provokes thoughts and feelings that broaden your mind. One’s likes or dislikes, he said, have “a lot to do with what you’re willing to accept” and what “you’ve been exposed” to. As far as his and Roberta’s preferences, they both like geometric abstraction. He prefers minimalist art more than she does. Although their tastes do diverge, they say they never argue over a piece or artist for the gallery.

To stay abreast of art and cultural trends, he reads art and news publications daily. He finds artists for the gallery in several ways. “

One of the best sources we have is the artists we work with,” he said. Seeing exhibitions is another. In May Bob attended the annual Navy Pier show in Chicago, featuring some 200 galleries from around the world. The couple used to make the rounds in New York, but can’t any longer due to physical/ financial constraints. Now, she said, “We bring the world to us. We’ve brought artists from Spain, Cuba, New York, Chicago, the West Coast. It’s made life very interesting.”

The Rogers know their gallery has limited appeal. That’s why they’ve tried developing their own market, largely through word-of-mouth. “And that’s difficult to do,” Bob said, “because the average run of people will buy a picture of a butterfly, but they would never buy a Claes Oldenburg painting or print of a clothespin sitting in the middle of Philadelphia. So we have to develop the kind of people that will relate to that.”

Many of their best customers are art-savvy residents who’ve moved here from either coast. The Rogers are known for hosting fun, informal potluck dinners, occasions they use to develop potential clients and to give guests a forum for “exchanging ideas.”

“People who don’t know each other, know each other when they leave. And so far we’ve never had a food fight,” Roberta said with a smile.

The couple has no plans to retire. “You don’t retire in art, you die in art,” she said. “It keeps us young.”

Besides, their mission continues.

“There’s so much to learn about art,’ said Roberta. “There’s so many different styles and types. And whether people come in and buy or not, we feel like our role is to educate them.”

Related Articles

- Art Dealers Re-up (observer.com)

- Now Showing | “Dennis Hopper Double Standard” (tmagazine.blogs.nytimes.com)

- A Collector of People Along With Art (nytimes.com)

- Fine Art Collector Magazine (castlegallerieschester.wordpress.com)

- Once More With Feeling, Loves Jazz & Arts Center Back from Hiatus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

A Peace Corps Retrospective

Another anniversary story. It was the 40th anniversary of the Peace Corps and I just happened to know a few veterans of that renowned service program, and so after they agreed to share their stories with me, those experiences formed the backbone of what I wrote. One of the individuals I profiled served in Afghanistan and the other three in India. All of them were deeply affected by what they saw and did and at some level that experience has informed everything they’ve done since then. My story originally appeared in the New Horizons. On this same blog you can find my profile of one of these Peace Corps veterans – Thomas Gouttierre, and his affinity for and work with Afghanistan.

A Peace Corps Retrospective

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Forty years ago, the first wave of Peace Corps volunteers landed in Ghana and Tanzania, Africa. The young, bright-eyed Americans were a new kind of emissary. Neither diplomats nor missionaries, they arrived in far-flung destinations with the appointed task of helping Third World peoples learn skills and develop resources for overcoming tyranny, poverty and disease.

Trained in various service assignments, ranging from education to health to agriculture, the volunteers embodied the idealism and vigor of America’s young, energetic President, John F. Kennedy, who had announced his vision for the Peace Corps in an October 14, 1960 campaign speech at the University of Michigan in which he challenged the nation’s youth to aid the developing world. Once elected, Kennedy reiterated the plan for an international volunteer corps during his January 20, 1961 inaugural address, asking a new generation of Americans to join “a grand and global alliance” to aid the dispossessed and pledging “our best efforts to help them help themselves.”

Kennedy’s clarion call was answered by thousands, including several Nebraskans. By September ‘61 Congress approved legislation formally authorizing Peace Corps and by the end of that year the first contingent of volunteers left for their host countries. Within five years, more than 15,000 volunteers from around the U.S. were implementing Peace Corps projects in the field. As of 2001, 163,000 volunteers have served in 135 countries.