Archive

Born again ex-gangbanger and pugilist, now minister, Servando Perales makes Victory Boxing Club his mission church for saving youth from the streets

It’s doubtful that another amateur boxing club has received as much ink and video coverage in the short time Victory Boxing has since starting about a decade ago. The magnet for the attraction is founder Servando Perales, whose personal story of transformation and redemption and unbridled passion for helping at-risk youth are the driving forces behind his boxing gym. The gym is really his mission church and sanctuary for getting kids out of the gang life that consumed him and landed him in prison. That’s where his own turnaround began. If you’re a boxing fan, then check out the boxing category on the right — I have many stories there about pro and amateur fighting, past and present.

Born again ex-gangbanger and pugilist, now minister, Servando Perales, makes Victory Boxing Club his mission church for saving youth from the streets

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Rev. Servando Perales and his faith-based Victory Boxing Club at 3009 R Streets is a story of redemption laced with irony. He’s eager to share the story at its April 25 grand opening, when from 1 to 3 p.m. the public’s invited to experience the program USA Boxing magazine recently named national club of the month.

In terms of redemption, consider how this one-time boxer and gang-banger from south Omaha survived The Life of a drug dealer-abuser only to undergo a profound transformation in prison. Behind bars Perales found God with the help of fellow con Frankie Granados, an old friend he’d run with on the outside. Granados already had his own born again experience in the pen and he worked on Servando to take the plunge, too. It took time but Perales finally “surrendered.”

On the curious side, consider that Victory head coach John Determan is both a former corrections officer and cop. He donated Victory’s first ring. He appreciates the oddity of a gringo badge and a Latino fist teaming up.

“I knew him as a bad guy when I was a cop,” said Determan, a former Mills County (Iowa) deputy. “That’s what’s cool, you know — bad guy-cop coming together to do something like this,” said Determan, whose son Johnny, a nationally-rated 119-pound amateur, and daughter Jessica, a former amateur world champ, train there.

Beyond their lawman-outlaw roles, Determan and Perales knew one another from boxing circles. They even traded blows in the ring when the older Determan was a journeyman pro fighter and Perales a feisty young amateur. They dispute who got the better of each other in those long ago sparring sessions.

Victory Boxing partnered with Jimmy John’s to purchase their gym at 3009 S. R. Street

Fighting’s not all they share in common. Both are devout Christians. Determan ran a faith-based boxing club in Glenwood, Iowa. The evangelists boldly fly their Christian colors at Victory, whose “t” is an oversized cross with a pair of boxing gloves hanging from it. A wooden cross adorns a wall inside, where Perales ends pep talks with, ‘You guys ready for the risen Lord? Alright, amen.’” The pair hold weekly Bible studies on Thursdays. All part of the signs and wonders that distinguish Victory from other gyms, where Christ is more apt to be an expletive than a prayer.

“The thing that separates us from all the other ones is that we’re Christ-centered,” said Perales. “We do not waver our faith, our values, and we stand firm on who can change a person’s life, and it’s Jesus Christ. That’s my strong belief and that’s what sets us apart. That’s why you see 30 kids in here. It’s not because we’re the best coaches or because we have the best fighters, it’s because they sense a presence of God in this place. I actually believe that.

“We acknowledge that God is the only one that can change circumstances and change people. If He did it for me he can do it for anybody.”

“It’s great when we have our Bible studies,” Determan said. “They’re really hot topics where we talk to the kids about things they might struggle with and they’re hearing it from two perspectives — the gang member and the cop. And that’s one of our testimonies to our kids — that it doesn’t matter who anybody is, skin color, background or any of that, you can come together.”

Perales, a father of five, said the fact he and Determan can speak with first-hand authority about both sides of the law, gives them an edge in dealing with kids who may have problems at home or school and be veering off track.

“They can’t pull a fast one over on either one of us,” said Perales, whose gym serves members ages 10 and up. The coaches field calls from kids at all hours.

The cop connection doesn’t end there. Retired Omaha deputy police chief Mark Martinez believes enough in what Perales does that he volunteers at the gym.

“Servando knows the challenges some young people face, having traveled that road himself, so he has an incredible ability to relate. His story is real and he has much credibility with youngsters. Consequently, he’s very effective, especially in helping troubled youth be positive and productive citizens,” said Martinez.

When storm damage made Victory’s previous site uninhabitable last summer, the gym was homeless. Martinez told a friend about it. Perales and the benefactor met and Victory soon had a spacious new home in the former Woodson Center.

“Actually, we wouldn’t be in this building had it not been for (ex) deputy chief Martinez. He’s the one who helped us get in this building by introducing us to a gentleman that actually put $65,000 up for this building,” said Perales.

A Weed and Seed grant purchased a new ring. The minister sees Victory as a partner with law enforcement to provide safe havens and activities. The gym hosts all-night lock-ins, takes kids camping and has them participate in community events, from parades to Easter egg hunts. Cops are frequent visitors. Some come to train, others just to kick it with kids. “We have a lot of cops that are friends,” Perales said. “Law enforcement is really deep out here. They’re strong. The gang unit, I know those guys personally. I grew up with them. We’re working, we’re doing everything in our power to keep the streets of south Omaha safe.”

It’s only logical the local Latino Peace Officers Association (LPOA) is a major backer of the gym, given its makeup and location in Hispanic-rich south Omaha and the club’s predominantly Hispanic members. But what you wouldn’t expect is that past LPOA president Virgil Patlan, the man who arrested Perales in ‘96 in a bust that sent Perales away for 18-months, ardently champions Victory. Once on opposite sides of the law, Patlan and Perales are friends and admirers today.

Perales attributes this turn of events to divine whimsy. “Yeah, God has a sense of humor, man — He put an ex-gangster and a cop together, and all for the glory of God,” said Perales, whose tats are remnants of the old life he left behind.

Patlan admits being dubious of Servando’s change of heart until hearing him preach and talking with him. “I was real skeptical at first because you hear this all the time about cons,” said Patlan. “It took a lot of ice-breaking but we became good friends. I knew he had a heart to help young people. I knew he didn’t want them to go through what he went through. I know if someone’s trying to pull the wool over my eyes — he’s not. He’s authentic, he’s genuine.”

An Omaha Police Department retiree, Patlan is an active community advocate and neighborhood association volunteer. He and Perales collaborate on projects.

“I think that’s where the trust and the respect came for each other,” said Patlan, “and we’ve just kept doing programs for the neighborhood.”

A program they formed called This is Your Neighborhood makes presentations to school-age kids about the evils of gang affiliation-activity and the importance of staying in school. By his late teens Perales was incorrigible and got expelled from South High. His troubles escalated after that. It’s why Victory requires members abide by a strict code of conduct that includes maintaining good grades and refraining from swearing, gang signs and any disrespectful behavior.

Since Victory’s inception Patlan’s helped with donations. He and his wife are planning a “fun run” to raise funds for the program’s operating expenses. Patlan and Perales share so many values they don’t dwell on the divergent paths that led them to the close bond they enjoy today.

“Now I don’t even think of it. It’s natural. We call each other brother,” said Patlan.

Something more than fate led Perales back to his roots. Before he got mixed up in a gang, he trained under Kenny Wingo at the Downtown Boxing Club. The promising amateur soon wasted his potential, using his skills to protect turf and wreak havoc. After his conversion and ‘97 prison release Perales turned pro. “The Messenger” once fought on the undercard of a world heavyweight bout. He hung up the gloves with a 9-5 record. His heart wasn’t in it anymore.

Between matches he’d already begun missionary work with at-risk kids in his old South O stomping grounds — steering youths away from bad influences he’d succumbed to and bad choices he’d made. His regular job as a YMCA membership coordinator reflects the Christian outreach he’s felt drawn to. Unable to ignore the call to serve, he was ordained a minister in the Assemblies of God Church in 2005. He launched Victory in his garage that same year, using “the gift of boxing” to coach/mentor/minister kids from the same streets he ran wild on.

“This is my church,” he said of Victory. “God called me to do this. It wasn’t by accident I boxed for 20 years. But with that comes responsibility, man.”

It’s no accident the Downtown club let an alum — Perales — train his kids there after the storm left Victory homeless. No accident he reunited with Determan, who took over Downtown after Wingo died. They’re family. It’s all come full circle for Perales. He sees in kids today the same hunger for love he craved at their age.

“Hopefully, God-willing, they learn and they feel valued here, because that’s the thing man — they’re all searching really for a sense of belonging,” said Perales, whose alcoholic father ditched the family. “For the most part they embrace our values and they love it here. 90 percent come to the Bible studies, and it’s optional. They want to be there. We tell ‘em, ‘You don’t have to join gangs to belong to something bigger than yourself. You don’t have to be a follower, man, you can be a leader.’ And that’s why were here — to provide that outlet.”

He said kids find escape at Victory from lives on the edge. “There’s maybe a couple I keep a close eye on and talk to one-on-one,” he said. Impressive prospect Luis Rodriguez, a gang member before Perales turned him onto Christ and boxing, “is one I think about a lot,” Perales said, “He’s been with me for about three years. I keep him very close to him. He and his little brother Ezekiel. They really respect our values.” Success stories include three Victory alums now in the military.

Peer pressure though is a constant worry. “I’m not going to lie, some kids have come and gone,” said Perales. “They didn’t embrace our values. They didn’t like the fact they couldn’t cuss, they couldn’t bag and sag, they couldn’t fight out on the streets. We’re not teaching them how to box so they can go out and hurt people. That’s what I did and I regret every minute of it.”

Victory’s road from humble beginnings to its envied new 10,000 square foot facility is the start of “a dream” Perales has to create a full-service “hope center.” A rec room’s set-up but computers are needed. The kitchen needs a new stove and fridge. The training area holds two rings and assorted bags and free weights but boxing equipment wears out fast. Hundreds of spectators can fit on the main level and balcony for boxing shows, which provide revenue for the nonprofit gym. But Victory struggles making the $2,000 monthly rent. Overdue repairs await fixes.

Meanwhile, he said, grant monies have run out. More donations would secure Victory’s future as a community center. “It’s got so much potential, there’s so much room to grow. But one day at a time. It’s only been five months since we moved in,” he said. He’s counting on the grand opening adding new members and support. “I’ve personally invited all the organizations in this community and hopefully they’ll make it out.”

He worries but then he remembers to trust in his Higher Power. “We’ve been walking in faith the whole time. He hasn’t left us yet. He didn’t bring us here to leave us hanging. He opened this door for us. I know He’ll take care of us.” Amen.

Related articles

- Gangs Are an Epidemic in Indian Country – But They Can Be Stopped (indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com)

- Head Boxing Coach for Mixed Martial Arts Conditioning Association Alan Kemp Inducted Into Buffalo Boxing Hall of Fame (pr.com)

The Cut Man: Oscar-winning film editor Mike Hill

The number of Nebraskans working in or on the fringes of the film industry is in the hundreds. I know there’s nothing remarkable about that in and of itself, other than that this is a small population state far removed from either coast. Then again, the vast majority of Hollywood film professionals originated somewhere else besides Calif., including lots of places just like Nebraska. But what is unusual is the high number of folks from here who have made significant contributions to the film industry either by the imprint or quality or volume of their work .

Try this cursory list on for size:

Darryl Zanuck, Harold Lloyd, Hoot Gibson, Fred Astaire, Robert Taylor, Ward Bond, Ann Ronell, Henry Fonda, Dorothy McGuire, Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando, Lynn Stalmaster, Donald Thorin, James Coburn, David Janssen, Inga Swenson, Sandy Dennis, David Doyle, Lew Hunter, Irene Worth, Joan Micklin Silver, Nick Nolte, Swoosy Kurtz, Paul Williams, Marg Helgenberger, Lori Petty, Sandy Veneziano, Alexander Payne, John Jackson, Jon Bokenkamp, Jaime King, Dan Mirvish, Dana Altman, John Beasley, Kevin Kennedy, Patrick Coyle, Gabrielle Union, Yolonda Ross, Nicholas D’Agosto, Chris Klein, Nik Fackler, Tom Elkins.

Add in Johnny Carson and Dick Cavett for good measure.

The list includes mega-moguls, directors, producers, screenwriters, songwriters, actors, actresses, you name it, and their influence extends from the silent era through the Golden Age of Hollywood to the indie movement and right on up to today. There are Oscar winners both behind and in front of the camera, industry stalwarts and mavericks, household names and lesser known but no less significant figures.

And then there’s the subject of this story, Mike Hill, an Oscar-winning editor who’s been attached to Ron Howard for decades and shared in the director’s many successes. Hill is an Omaha native and resident known for his generosity with young, aspiring filmmakers and editors. I did the following profile on him in 2002 and what most interested me about him then and still does now is the story of how he came to work in Hollywood in the first place and the classic journey he took as an apprentice learning his craft. During that process he worked with some genuine legends and those experiences obviously added his professional development.

The Cut Man: Oscar-winning film editor Mike Hill

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Success for Mike Hill, Academy Award-winning film editor from Omaha, did not come overnight. His local-boy-made-good-in-Hollywood story ranges from lean years learning the craft to being mentored by old pros to turning lucky breaks to his advantage to reaching the pinnacle of his profession.

He and fellow editor Dan Hanley, who together cut all of Ron Howard’s films, shared the 1995 Oscar for Best Film Editing on Apollo 13 and are nominated again this year for the critically-praised A Beautiful Mind, which is up for a total of eight Oscars, including Best Picture. During an interview at the Pacific Street Spirit World, Hill, who lives in Omaha with his wife and their daughter, discussed his career and collaboration in cinema.

After graduating from Omaha Burke in the late 1960s Hill attended UNO, where he studied a little of everything before earning a criminal justice degree. To pay his way through school he worked nights as an assistant film editor at Channel 6 television, splicing 16 millimeter commercials together, a seemingly forgettable job that, however, would soon be his entree into movies.

He headed out to California in the early 1970s with the idea of working in penology. But after a few months as a Chino State Prison guard he realized he was in the wrong field and promptly quit. He took odd jobs to pay the rent and almost on a whim applied for work with the film editors guild.

“I wasn’t really counting on anything,” he said. “Then luckily one day I was home when a phone call came from the guild saying Paramount was hiring. I ended up getting hired as an apprentice, which consisted of working in film shipping and driving a golf cart delivering film to editing rooms and screening rooms and doing whatever they told you to do.”

As unglamorous as his work was, Hill landed in the movies at a propitious time and a prestigious place. It was 1973 and Paramount ruled Hollywood after scoring big the previous year with The Godfather. The studio was producing a whole new slate of soon-to-be classics.

“It was an amazing time,” he said. “The movie business was very busy. Paramount was making Godfather II and Chinatown at the time I was there. I would just marvel every day at who I saw on the lot — Jack Nicholson, Al Pacino, Robert De Niro. So, it was pretty heady stuff for a kid from Omaha.”

Once Hill understood the way out of the shipping room meant learning how to be an assistant film editor, he announced his ambition to do just that.

“I was fortunate to have a couple assistant editors I met who were willing to teach me how to synch-up dailies. When film comes from the previous day’s shoot you synch it up with picture and track (soundtrack) so it can run in a screening room. I learned how to do that and I slowly learned editing room tasks.” His first screening room duties were for then hit TV shows like The Brady Bunch. Learning the ropes the same time as Hill was Dan Hanley, with whom he would later team.

Among the old-line editors Hill and Hanley apprenticed under was Bob Kern. “Both Dan and I learned quite a bit from him. He would give us scenes to edit — to work on — and that’s the best way to learn. He and other editors encouraged us to pursue it and to move up.”

The ‘70s saw Hill work on many made-for-TV movie and film projects. Two master filmmakers he assisted around 1976 spurred his development: on The Last Tycoon he worked with Elia Kazan (On the Waterfront) whose elegant if rather lifeless feature adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s unfinished last novel ended up being the director’s final film; and on Bound for Glory he worked with Hal Ashby (Coming Home), whose exquisite vision of folk singer Woody Guthrie’s life story secured critical plaudits but saw scant box office returns.

Hill said he went to the Tycoon set every day observing Kazan at work and ran dailies for him the entire shoot. Kazan may have noted his young charge’s intense interest in the process as, Hill said, “He took me under his wing and let me cut some scenes. One scene he was going to reshoot anyway, so he said. ‘Go ahead and cut this together and see what you can do with it.’ I was there all night messing around with it. It was a simple scene of two people talking. On every line I cut back and forth until it was like a ping pong match. I really didn’t know what I was doing. He looked at it with me in the screening room and told me, ‘You don’t need to cut so much. Pick your spots and sometimes let a scene play out awhile.’ I learned stuff like that from him that was invaluable. The same way with Hal Ashby.”

It was while working in a second editor’s position on TV movies that Hill “really started to learn how to edit.” He was prepared, therefore, when his big break came in 1982. He was set to join his old mentor, Kern, and his former shipping room mate, Hanley, as an assistant on Ron Howard’s first mid-major studio feature, Nightshift, when Kern suffered a stroke.

Instead of bringing in a veteran replacement Howard entrusted the lead editing to the green assistants.

“We had a lot of responsibility on our shoulders,” Hill said, “but we were too young and too stupid to be really that aware of it, and so we just did it. Bob was there to lend moral support and answer questions. The movie turned out to be a modest comedy hit, enough of a hit to get Ron Splash.”

Then came Cocoon. As Howard’s directorial career reached ever greater heights, Hill and Hanley went along for the ride every step of the way. Their nearly exclusive relationship with him is one of the closest collaborations between a director and an editor, or editors, in Hollywood. So, what makes it work?

“I think personality-wise we kind of meld,” Hill said. “We have the same interests. Our senses of humor mesh. There’s really no ego problems…and Ron is just the nicest guy in the world. We’re all really good friends. Plus, he likes our work and he likes having two film editors.”

During production Hill-Hanley cut on location and during post-production they work at a permanent editing suite Howard maintains in New York. The men work in separate rooms on separate scenes before assembling a first cut. In shaping the raw footage coming-in during the shoot, the pair enjoy great latitude.

“We have total freedom. Ron just lets us go. He’ll give us cryptic notes like, ‘I like that take’ or ‘Try to use this moment’ and that’s it. The structure and everything is up to us. He relies on us to come up with things he doesn’t expect to see. He likes to be surprised.”

Once shooting is complete Howard joins his editors and the three slowly prune the film-in-progress into a workable length.

“Ron’s kind of impatient about editing. He doesn’t like to sit around. He likes going back and forth from room to room,” Hill said, “so he’s always got something to look at. We’ll look at the movie reel by reel with him and get extensive notes from him about each scene and then we’ll go to work on them. We’ll do an entire pass and see how much time we’ve taken out and how it plays and then we’ll start again. We try to make every scene shorter without hurting it. Some of the toughest decisions are which scenes to drop. But some scenes have got to go, including some that would be very good and that I’ve grown attached to personally because I’ve worked so hard on them. It’s a slow process of whittling it down, sculpting it, refining it, honing it. We’ve got a good system worked out over 20 years now.”

The art in what Hill does comes in selecting from the myriad takes at his disposal to create a seamless film that appears to have sprung to life, organically, as “one piece,” he said, adding, “That’s what I admire about good editing.” Working for Howard means sifting through “a lot of angles and a lot of takes. He shoots a lot of film. He likes to have options. We’ve always found, especially when you need to trim a scene down, that the more coverage you have the more success you have in shortening a scene. You’re stuck if you just have one or two takes or one or two shots. Then, you have nothing to cut to. There’s no way to get out of the scene.”

Making Hill’s job easier is the fact Howard commands final cut. “Ron’s in a position where he has complete power. There’s nobody messing with him, which is great for us because there’s nothing worse than working on a film where the director loses control and the studio steps in.”

Hill lived that nightmare on one of the few Howard-less films he edited, Problem Child. He said each project has it’s own “unique problems.”

Of Howard’s films, he lists Willow and Apollo 13 as the toughest assignments because the former entailed so many special effects shots and the latter required flawlessly blending weightlessness footage shot in a plane with matching footage shot on a sound stage. The Grinch posed a new challenge when Howard broke precedent and allowed an actor, star Jim Carrey no less, free reign in the editing room to select his own takes. Hill said while the character-based A Beautiful Mind involved a lower degree of difficulty than those technically-oriented films it demanded greater finesse in shaping a cohesive performance from star Russell Crowe, whose takes ranged wildly from subdued to over-the-top, and in preserving the integrity of the narrative while shortening the piece.

Hill has been in the business long enough now that he has hands-on experience working with the full historical range of film editing equipment — from the old Movieola (“a horrible machine…a dinosaur”) through which film noisly clattered through a gate to the streamlined Kem (“much more civilized”) to today’s digital Avid system (“a huge leap forward”) that eliminates the need to ever handle film again and allows instant access to every shot.

“Now, we can finish a scene that used to take days in an hour.” The Movieola days were such drudgery, he said, “that I have to admit there were times I got so tired of editing a scene, I’d say, ‘That’s it — I don’t care anymore. Take it or leave it.’” It’s no coincidence his new confidence in his work has coincided with the labor-free new technology. “It gives us freedom to experiment” with pure editing because “you don’t have to worry about splicing, putting frames back, loading or unloading film. You can approach a scene totally without fear..do whatever you want and there’s no consequences.”

As for his and Hanley’s Oscar bid, he said, “I don’t really believe we’re going to win. Our picture isn’t showy or flashy enough. But I didn’t think so last time either.” Should he win, the statuette will likely join his Apollo 13 Oscar on a bookcase at home.

Meanwhile, he’s anxiously awaiting word on Howard’s next project and is getting antsy enough that he’s having his agent look for a temporary assignment he can fill until the call comes.

During lull periods he sometimes lends his expertise to small independent films, including the Omaha-made Shakespeare’s Coffee and The Full Ride. Even though he and Hanley have no formal agreement with Howard stipulating they will work on his films, neither has missed one in 20 years and Hill doesn’t intend missing one now that Howard is such a prominent Player in Hollywood.

Related articles

- Screenwriting Adventures of Nebraska Native Jon Bokenkamp (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: About ‘About Schmidt’: The Shoot, Editing, Working with Jack and the Film After the Cutting Room Floor (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne – Portrait of a Young Filmmaker (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne Discusses His New Feature ‘About Schmidt’ Starring Jack Nicholson, Working with the Star, Past Projects and Future Plans (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Alexander Payne Achieves New Heights in ‘The Descendants’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Vincent Alston’s Indie Film Debut, ‘For Love of Amy,’ is Black and White and Love All Over (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Song Girl Ann Ronell (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Designing Woman: Connie Spellman Helps Shape a New Omaha Through Omaha By Design

Designing Woman: Connie Spellman Helps Shape a New Omaha Through Omaha By Design

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Connie Spellman’s imprint on Omaha grows every day. As director of Omaha By Design, the Omaha Community Foundation (OCF) initiative attempting to do nothing less than change the face of the city, she has her hands all over the metro.

When she joined what was then called Lively Omaha in 2001 Spellman was already a passionate advocate of the city from her prior Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce career. Her Chamber experience gave her a keen understanding of how the private and public sectors work in Omaha.

“I’d had a wonderful career at the Chamber and couldn’t imagine having another position that was as fun and meaningful and rewarding as that,” she said. “I’d had a year of retirement and other opportunities that sounded like jobs. And I wasn’t ready. And this one came along…”

“This one” refers to her Omaha By Design position, which is that of facilitator and visionary. She brings diverse people together to brainstorm ideas, design guidelines, write zoning-construction codes and develop projects that embody aesthetically pleasing, eco-friendly, cohesive urban planning. The aim is to improve Omaha’s appearance and the way people interact with their lived environment. She works closely with the city, neighborhood groups and the private sector to do that.

She took the newly formed post, she said, because “I love Omaha. I enjoy challenges. I thought the timing was right because sometimes timing is everything. The city was really ready for looking beyond its historic attributes to look at its environment in a bigger picture.”

When then-OCF chairman Del Weber recruited her to the job Omaha was in the throes of an identity crisis. The city embodied stolid Midwestern values predicated on friendliness and work ethic but could claim few signature public spaces. The adverse effects of suburban sprawl, inner city neglect and scattershot development were everywhere.

“We’re a great city of individual projects that were developed without consideration of how they’re connected to each other,” she said.

Studies confirmed Omaha lacked a positive image and that residents, especially younger ones, found the city dull and drab. Spellman said a Gallup survey found only a small percentage of Omahans thought the city attractive.

“I was appalled,” she said. “I thought, What a shame. It means we really haven’t paid attention to it and we didn’t have much pride in it. How can we be competitive and expect our kids to stay here if we think our city is unattractive?”

Foundation supporters, who include some of Omaha’s movers and shakers, hired Minnesota consultant Ronnie Brooks to assess the city’s Wow! factor. He suggested Omaha needed to be more” connected, smart, significant, sparkling and fun.” The foundation created Lively Omaha in 2001 to do just that, but it floundered trying to put into action what sounded so abstract or, as Spellman put it, “nebulous.” Meanwhile, Omaha’s doldrums and inferiority complex festered.

Still, she said, those words by Brooks “in one way or another kept coming back to everything we do — to how we look and how we act…”

Then something happened that brought the organization’s mission into focus. When the downtown-riverfront construction boom began — one that ultimately resulted in $2 billion in new development — Lively Omaha saw the potential for an Omaha makeover on a citywide scale.

The Omaha World-Herald’s Freedom Park, Union Pacific’s and First National Bank’s new headquarters, the Holland Performing Arts Center, the Qwest Center, the Gallup campus, the National Parks Services building, Creighton University’s soccer stadium and new dorms and a beautified Abbott Drive created a dynamic new downtown-riverfront corridor. What had been unsightly was now a picture postcard destination district. These projects signaled a major turnaround in not only Omaha’s appearance but in the way Omahans felt about their city.

More energizing projects followed, including the Saddle Creek Records build-out with Slowdown and Film Streams and nearby hotels in NoDo. More is on the drawing boards, notably the $140 million downtown baseball stadium slated to open in 2011.

The cityscape is changing far beyond downtown as well. Improvements around 24th and Lake Streets and along the South 24th Street business strip, the transformation of the former stockyards site and the mixed use developments going up on the Mutual of Omaha and Ak-Sar-Ben campuses are examples of the New Omaha.

Spellman said such projects are changing residents’ and visitors’ appreciation for a town that’s long battled an image problem.

“That translates into so many things,” she said. “You can’t help but feel good when you’re downtown today or driving into our city. There’s an energy here that’s coming back because people have a vision that is being realized. And I think that attitude can accelerate the implementation of the vision because once you get a taste of it you want more, faster.”

She’s certain if a survey were done today sampling the city’s “It” quotient there would be a very different result than a decade ago.

“I think people would feel better about their community. I think there is a contagion that is going on because of the continued development that’s happening downtown and the revitalization of suburban areas like Village Pointe.

“I see it everywhere — in what people do with their own homes and what they do with their businesses and what they want to see happen with development in general and how they view their city.”

It’s ironic the woman who has Omaha reinventing itself through sustainable, livable design strategies had to immerse herself in the subject when she got the job.

“I knew nothing about urban design or public space,” she said from her office in the historic Blackstone building. She’s about a stone’s throw away from Mutual of Omaha’s Midtown Crossing at Turner Park project under construction — an example of the kind of transformation she advocates. “I have always had an appreciation of art and architecture but I never really put them in the context of public spaces or design. And so the first thing I had to do was educate myself.”

That posed no problem for this former teacher who’s devoted much of her public service to education. She read, she sounded out experts, she attended trainings.

“Perhaps the basis for most of my education came from Project for Public Spaces (PPS), a national advocacy group,” she said. “It grew out of the work of New York planner William Whyte, whose book The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces is fascinating. I learned enough to allow me to ask questions. And then I was fortunate enough to meet people like Doug Bisson, a planner at HDR, who recommended more books.”

After PPS training in New York she returned to Omaha to organize Place Making sessions, which she describes “as a way to engage citizens in helping them decide what their own spaces should look like and discover their own neighborhoods’ potential.” Place Games and Place Definitions workshops were held with neighborhood associations. Program Manager Teresa Gleason leads these sessions today. Ideas get broached, goals set and actions taken to make improvements — from lighting to green spaces to facades.

Through these experiences Spellman and others gained a new sense for how Omaha could be flipped.

“I had to have that ‘Ah-ha’ moment in looking at Omaha because I’ve seen it as I’ve always seen it — family-oriented, hard working, conservative. I loved it but I didn’t see it in terms of its potential,” she said. “Then I saw it in terms of what it could look like — a lively, more interesting Omaha that is cutting edge, exciting and fun.

“You can never see the city the same way again once you see it as what it could be. That’s probably the greatest gift to me — opening my eyes to see what the potential is for this city.”

Spellman is unabashedly devoted to Omaha, where she and her husband, attorney Rick Spellman, moved in the ‘70s. It’s where they raised their three kids. Some of Omaha’s greatest ambassadors didn’t start out here and she’s among them. The former Connie Hoy grew up in Wahoo, Neb. Her family moved there from a farm they had near Lincoln. She enjoyed small town life.

“I probably had the most idyllic childhood. I lived a block away from school. The thing about small towns is you’re forced to do everything because there aren’t enough people. I love the opportunity to sample everything. I think that’s useful.”

Her role of helping Omaha see itself in a new light is in keeping with her background.

“I am first and foremost an educator because that’s what I went to school to be,” the 1965 University of Nebraska-Lincoln graduate said.

She taught high school in Ashland, Neb. for two years while her husband Rick was in law school. Even then she showed a knack for getting broad coalitions of people involved as she started a speech and theater program. Under her direction community productions of South Pacific and Our Town were staged.

“We got the whole town engaged in these productions,” she said.

Sound familiar? She built coalitions as a volunteer with the Junior League, a women’s group that promotes community involvement and leadership development. Her work there led to her involvement with the Chamber, where she spearheaded corporate leadership and public school education initiatives.

In a sense, what this designing woman does today is direct an epic scale version of Our Town where the props and the players are real and the stakes are for keeps.

The more she steeped herself in what constitutes good design the more she saw Omaha for the first time. The striking new face that began emerging downtown and on the riverfront offered a preview of what could be. It increased expectations.

“With the downtown redevelopment we were beginning to see that transformation is possible and energizing and positive. It was a wonderful catalyst to begin to say, Boy, if we can do it downtown, why can’t we translate this throughout our entire city? We can still be hard working and family-oriented but we can also be cutting edge and exciting and fun. We can be competitive in a regional market which we really hadn’t been. All of that, I think, gives a sense of pride, a sense of energy.”

What became known as Omaha By Design evolved from studies, surveys and discussions prompted by Foundation donors. This led to public meetings where citizens weighed in. The work continues today.

“It’s all citizen-led,” she said. “One of the terms we use is, ‘The citizen is the expert — the community is the expert.’ They know best what they want for their community. We just help them see it differently.”

All the feedback called for a citywide approach focusing on key neighborhoods, districts, corridors, sectors that took a more considered approach to development — from signage to setbacks to lighting to landscaping to public art.

The idea’s to create organic, splendid, interconnected, pedestrian-friendly spaces that make Omaha a more pleasant place to live and therefore a more competitive market for attracting and retaining companies and individuals.

“Besides the feel-good aspect there’s an economic component to this as well,” Spellman said. “If you design a building well, if you have a shopping center that’s easily accessible for pedestrians and exciting and attractive, that’s going to be a return on investment.”

The real work began in response to a pair of new Wal-Mart stores slated for Omaha. Objections arose over the plans for the big box projects and their ugly concrete footprints, which all but ignored elements like greenery or enhanced lighting. Spellman, local elected officials, Omaha Planning Department staff and other concerned citizens concluded if the city wanted projects with more curb appeal than design standards must be adopted that compel developers-builders to conform. Rules and regulations with oversight-enforcement teeth were needed.

“In order to create the vision there had to be a change,” she said. “Otherwise, you would have continued to perpetuate the development that’s gone on before.”

Wal-Mart was Omaha’s line-in-the-sand.

“We weren’t content to take the bottom drawer of a Wal-Mart or any box store,” she said. “We were confident enough to say we won’t accept that anymore. We deserve more.”

That’s when her organization decided to undertake a comprehensive plan, called the Urban Design Element, which meant identifying and articulating areas of the city in need of revitalization and redesign. This required the collaboration of a cross-section of city departments, design firms, real estate developers, lawyers, utilities providers, neighborhood associations and others.

Philadelphia planner Jonathan Barnett helped devise Omaha’s plan. He divided it into three focus areas — Green, Civic and Neighborhoods. “That was one of the best organizational tools we could have come up with,” Spellman said, “because it helps you so much describe it, define it, categorize it, implement it. This way you break it down into very visual, concrete segments that anybody can see. There’s something for everybody.”

A list of goals for each segment is now in place and projects have been targeted within each goal.

The Urban Design Element was not the end game, however.

“It was written not as a plan but as a specific element that once adopted went right into the (city’s) master plan,” she said, “which I think was a brilliant thing. We didn’t want it to be a report that sat on the shelf. Just because it’s part of the master plan doesn’t mean it has the force of law or automatically gets done. It doesn’t unless attention is given to it.

“The highest priority was the implementation of those recommendations that required codification in order to be effective. That became our next major effort.”

In August of 2007 the Omaha City Council unanimously adopted the Urban Design Element into the city’s official master plan. Ideas and goals had been turned into tangible, enforceable codes. As a result, Omaha no longer has to settle for what a developer or builder decides is a sufficient design but the city now has specific standards in place that, by law, must be met.

She said the effort needed both the private and public sectors involved “to make this work and we did have that from the very beginning. It was a wonderful blend that was strategically thought about to make sure that every sector had a voice.”

Spellman got diverse players to sit at the same table and work out the details. Her talent for “bringing people together to get things done” is one of the skills she learned in her 20 years at the Commerce. She managed its Leadership Omaha and Omaha Executive Institute programs and led its education and workforce development initiatives, Omaha 2000 and the Omaha Job Clearinghouse, respectively. Her successes made her a player.

Typical of Spellman, she prefers deflecting attention away from herself and onto others. For example, she credits the Omaha Planning Department with helping make the Urban Design Element a reality.

“I can’t say enough about the role of the Planning Department in making this happen,” she said. “Steve Jensen, Lynn Meyer and Co. are trusted and respected by the development community and they’ve been a real factor in working this through. They were totally professional and patient.”

Her work, however, has been much recognized, including being named The World-Herald’s 2007 Midlander of the Year. She’s previously been the recipient of the Ike Friedman Community Leadership Award and other awards noting her community focus and consensus building.

She said as arduous as creating the Urban Design Element was, “codifying these design standards” was a classic “the-devil’s-in-the-details process” that required innumerable meetings. An expert committee addressed the codification, which among other things put the standards into language that was clear and binding. There was much discussion, argument and compromise.

“It was more technical. It was a smaller, tighter group having to deal with the codes,” she said. “We added more developer-real estate-leasing agent-finance people that really understood the implications of what was going to be asked of them and coupled it with the design community — architects, landscape planners, city department heads — all at the table.

“We thought it was going to be a year’s process. It turned out to be two years. It was the best thing that we did take the two years because nobody had ever done this before. We’re really trying to address so many things from so many different perspectives.”

Spellman said no U.S. city has ever tackled such a sweeping, all encompassing design plan to code.

“Where others had done major sections of code it was usually in a city like Santa Fe, where everything is the same, uniform Southwest look, or a Santa Barbara, where there’s very strict requirements. Well, we didn’t want Omaha to look all the same, so that meant our code doesn’t fit all. Therefore, we really needed to make sure there were no unintended consequences.

“We had to test and reevaluate and retest. There was a several month period where we studied (design) surettes of (mock) urban settings and suburban settings to see how the codes would affect those. Then we learned how topography affects those. It was a true education in how important it is to do it right the first time. It takes time.”

Developers, builders and others who will be working within these codes on future projects expressed various concerns.

“There’s a fear factor,” she said. “What if it doesn’t work? What if it’s going to cost more? What if it’s going to prohibit development? Those are legitimate issues. That’s why it took so long — to be sure that all of us were comfortable with the outcome. The last thing any of us want to do is to hamper economic development. We’re all in this for economic development and quality of life.”

Consequently, nothing’s set in stone. By its nature, urban design is evolutionary.

“It’s not hard and fast,” she said. “Something this big and this broad can’t be perceived as perfect the first time out. That’s why the Technical Advisory Committee decided to stay together to be that sounding board. If the language doesn’t meet the intent then let’s by all means change it. We’re already working on some issues that we discovered need to be changed.”

The committee also serves on the city’s Design Review Board, which is charged with interpreting the codes.

Redesigning Omaha carries the responsibility of being true to all those who’ve participated in the process.

“In a way we’re protecting the interests of all the people that attended meetings and voiced their opinions,” she said. “So we really felt this was a mandate from the community. We went through this process not just as an exercise but as something we want to see because we love our city and we want to make it better. I take that as a responsibility and I don’t want to stop until we’re done.”

Omaha By Design recently released its Streetscape Handbook. This primer for project managers, developers and design professionals offers guidelines for creating enhanced streetscape environments that give careful attention to street fixtures rather than treat them as afterthoughts.

“It deals with all of the street furnishings in the public right of way,” she said. “Signage, street lights, wires, bike racks…If you think about the placement of this stuff you have to have anyway, if you think about maintenance and sustainability and how it relates to each other and how it looks on the street, it makes a whole different visual impression.”

The committee that generated the handbook was made up of architects, landscape designers, city planners, public works professionals, roads experts and “anyone that had something to do with the placement of street furnishings or the streetscape,” she said. “We worked together for 27 months, once a month, to figure out what we needed to do and how we could do it. I think we’re proud of what we’re presenting. It’s an example of people working together because there’s a vision of what we want out city to be some day.”

None of this could happen, she said, without broad support and participation. “We rely heavily on volunteers and community leadership to make these things happen,” she said.

Where is Omaha By Design’s work taking shape?

Projects have now been identified in each of the Urban Design Element’s goals, “which I think is very exciting,” Spellman said. Keep Omaha Beautiful is undertaking one of the first projects — a landscaped highway’s edge at I-680 and Center.

Other efforts are in progress or soon to start. Omaha By Design acts as project manager for some, including the Benson-Ames Alliance, a comprehensive plan for integrating the design of commercial centers with their neighborhoods. The goal is mixed-use centers that blend retail, residential and office in a balanced manner. The plan also addresses transportation, housing and public space issues.

The Alliance has two projects underway — the Cole Creek Project and the Maple Street Corridor Project. The first entails various stormwater construction to help cleanse runoff and moderate the amount of water flowing into Cole Creek; the second designs functional-decorative streetscapes along the Maple corridor and builds on the entrepreneurial growth under way in downtown Benson with a goal of spurring development in neighboring sectors.

All this activity requires Spellman attend many meetings.

“My to-do lists are pages long,” she said.

But she’s doing exactly what she wants to do.

“I’m very fortunate. It’s just a gift. I am totally content and most days very excited about the potential of what we’re doing.”

- The Slowdown and Film Streams development in NoDo or North Downtown

- Related articles

- Omaha’s Film Reckoning Arrives in the Form of Film Streams, the City’s First Full-Fledged Art Cinema (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jeff Slobotski and Silicon Prairie News Create a Niche by Charting Innovation (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Overarching Plan for North Omaha Development Now in Place, Disinvested Community Hopeful Long Promised Change Follows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Nancy Oberst, the Pied Piper of Liberty Elementary School (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Lit Fest: ‘People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Golden Boy Dick Mueller of Omaha Leads Firehouse Theatre Revival (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Opera Comes Alive Behind the Scenes at Opera Omaha Staging of Donizetti’s ‘Maria Padilla’ Starring Rene Fleming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Legends: Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce Business Hall of Fame Inductees Cut Across a Wide Swath of Endeavors (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Garry Gernandt’s Unexpected Swing Vote Wins Approval of Equal Employment Protection for LGBTs in Omaha; A Lifetime Serving Diverse Constituents Led Him to ‘We’re All in the Human Race’ Decision (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Linda Lovgren’s Sterling Career Earns Her Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce Business Hall of Fame Induction (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Nick and Brook Hudson, Their YP Match Made in Heaven Yields a Bevy of Creative-Cultural-Style Results – from Omaha Fashion Week to La Fleur Academy to Masstige Beauty and Beyond (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Entrepreneur Extraordinaire Willy Theisen is Back, Not that He Was Ever Really Gone (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- North Omaha Champion Frank Brown Fights the Good Fight (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

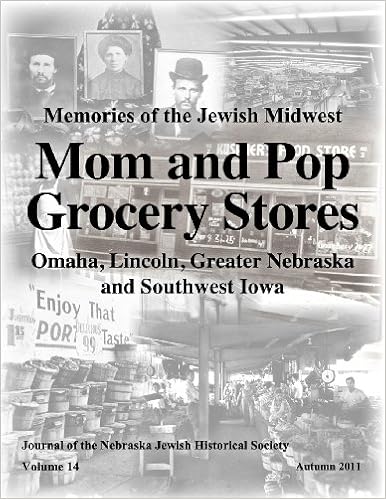

“Memories of the Jewish Midwest: Mom and Pop Grocery Stores, Omaha, Lincoln, Greater Nebraska and Southwest Iowa”

“Memories of the Jewish Midwest: Mom and Pop Grocery Stores Omaha, Lincoln, Greater Nebraska and Southwest Iowa”

I contributed to a new book out by the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society that is an appreciation of the Jewish Mom and Pop grocery stores that once dominated the landscape in Omaha. From time to time I am posting an excerpt from the book to give provide a sample of the robust story it tells. For this post I chose a front section essay I wrote about the long defunct wholesale market that operated just southeast of downtown and that today is home to the popular historic cultural district known as the Old Market. While the market didn’t contain grocery stores, its many wholsalers serviced grocers. It was a bustling center of commerce abd characters that is no more.

For additional information or to order a copy of the book, contact Renee Ratner-Corcoran by e-mail at rcorcoran@jewishomaha.org or by phone at 402.334.6442.

Excerpt from the book-

The Old Market: Then and Now

©by Leo Adam Biga

Omaha’s Old Market is a National Register of Historic Places district abuzz with activity. Bounded by 10th Street on the east, 13th Street on the west, and extending from Leavenworth Street on the south end to Howard Street on the north end, the character-rich area is an arts and entertainment hub. Restaurants. Speciality shops. Art galleries. Performance spaces. Many venues housed in late 19th and early 20th century warehouse buildings.

Street performers and vendors “set up shop” there. Horse-drawn carriages transport fares over cobblestone streets. Streams of shoppers, diners, bar patrons, art lovers, theatergoers, sightseers, and residents file in and out, back and forth, all day long, through the wee hours of night. Summertime finds folks relaxing at restaurant and bar patios. Fresh flowers adorn planters arranged all about the Market.

Fifty years ago and for a half-century or more before that these same streets and warehouses were equally busy, the commerce transacted there just as brisk. Only instead of trendy eateries, boutiques, galleries, and studios, the urban environs contained Omaha’s wholesale center for fresh fruit and vegetables. Whatever was in season and sellers could lay their mitts on, the market carried it. Now and then, owing to untimely droughts or freezes in prime growing areas, certain items were in short supply. During wartime, rationing made much produce scarce. But most of the time the Market offered a great variety of fresh produce at reasonable prices.

In an earlier era, the Market, along with the Jobbers Canyon complex of wholesale and mercantile warehouses, meat packers, and outfitters a bit further to the east, supplied surveyors, land agents, speculators, railroad workers, steamboat crews, military personnel, trappers, and pioneers with the stores needed for settling the West. Jobbers Canyon, however, went the way of the wrecking ball, a fate that could have easily befallen the Market if not for a few interventionists.

The Way It Was

The Omaha Wholesale Produce Market House Company was an officially incorporated consortium of wholesalers and the Omaha City Market the city designated marketplace where the local produce industry concentrated. This American equivalent of the Middle Eastern bazaar or Old World farmer’s market consisted of two fundamental parts.

Multi-story brick buildings housing warehouses, mercantiles, and offices were where the major produce wholesalers and brokers did high volume, bulk business with major buyers. A single wholesale deal might have moved 40,000 pounds of watermelons, for example. At street level, the warehouses featured a system of docks and bays where trucks carting loads of produce parked, their contents emptied out onto sidewalk pallets for immediate resell to buyers or into storage for later resell.

Perhaps the biggest Jewish wholesaler in terms of volume handled was Gilinsky Fruit Company, whose two-story warehouse and offices became home to the French Cafe. When Sam Gilinsky’s business closed in 1941 several former employees, many of them Jews, opened their own wholesale businesses and wrote their own chapters as successful Market entrepreneurs. One of Omaha’s most recognizable and nationally branded businesses, Omaha Steaks, owned by another Jewish family, the Simons, did business in the Market when still known as Table Supply Meat Company.

An open air market located in a paved lot at 11th and Jackson Street saw vendors and peddlers doing business with neighborhood grocers and retail consumers. The merchants selling there rented stalls, where they displayed their wares in bushel baskets, barrels, crates, boxes, and bags arranged on benches. The hawkers benefited from a sheet metal canopy overhead. Tarps were stretched out for additional protection. Old-timers who worked there will tell you the conditions made for long days during the heat of summer, when the canopy and tarp would get burning hot to the touch and make it like a sauna underneath. Standing on the hard cement was tough on shoes and feet.

Across from these vendors were local truck gardeners and farmers, who turned an alleyway into a market of their own, selling bed loads of produce.

These were small family businesses. Men made up the vast majority of Market workers, but some women and children worked there, too. For most, it was a humble living, but more than a few sons of immigrant vendors and peddlers went on to become doctors, lawyers, educators, and to enter many other professions. In this way, the Market was an avenue to the American Dream for first and second generation families here.

The marketplace attracted a small army of workers and customers. Suppliers included farmers, gardeners, and greenhouse owners. Wholesale produce dealers ranged from giant operators buying and selling in train car lots or truckloads to smaller operators. The middle men included brokers, jobbers, and distributors.

Most of the vendors and peddlers were immigrants, including Jews from Russia, Poland, and Germany, along with Syrians and Italians. Yiddish was among the many languages heard wafting through the Market. The foreign-born merchants’ raised, heavily-accented voices mixed with various American accents to create a music all their own. Then there was the sonorous strain of the district’s very own Italian tenor, “Celery John” (Distefano), who would serenade the marketplace when the mood struck.

Veteran produce marketer Sam Epstein said Celery John “had a voice like you’d hear in an opera house,” adding, “It was absolutely marvelous to hear him.” Epstein said he would stand outside Celery John’s place and kibbitz as the erstwhile Caruso made up “soup bunches” and “plant boxes.” “His personality and his demeanor were just the same as his voice,” said Epstein “Just a wonderful human being.”

Don Greenberg, whose family’s wholesale Greenberg Fruit Company had a decades-long run in the Market, recalled Celery John once leading a group of workers in a rendition of the “Happy Birthday” song. The occasion celebrated the birthday of a veteran, well-liked merchant. The guys even got up enough dough to go in on purchasing a rather extravagant gift then — a television set.

It was a place where men in smocks, aprons, overalls, or dungarees and with nicknames like Dago Pete, Crowbar Mike, Montana, Shoes, Red Wolfson, and Popeye rubbed shoulders with men in suits. Brothers George and Hymie Eisenberg became known as the Potato and Onion Kings for the considerable nationwide market share they held supplying spuds and onions to large food processors.

The Eisenbergs had a much humbler beginning though as a family of produce peddlers. Many immigrants had established routes in neighborhoods around Omaha and on back country roads, where in the early days they traveled by horse and wagon before modernizing to trucks. Peddlers often operated stalls in the Market, too. Some peddlers and vendors, like the Eisenbergs, eventually became wholesalers.

The primary buyers at the Market were grocers, restaurants, hotels, institutions, and major food processors. Just like today’s Omaha Farmers Market, the general public went to get their pick of fresh produce during the summer from the open air market that operated there. Day in, day out, the Market saw a flow of people, trucks, and goods. George Eisenberg can attest to “a lot of hustle and bustle, a lot of competition” that went on.

Changing Times

The Market thrived as a produce center from at least the first decade of the 20th century, when it was incorporated and a city appointed superintendent of markets or market master put in place to collect rent, enforce rules, and settle disputes, through the late 1950s. By the early ‘60s the Market declined as wholesalers either disbanded or moved west, the peddler trade disappeared, and many neighborhood and country grocers went belly up. The emergence of supermarket chains had a ripple effect that drove the small independents out of business, thereby eating into the Market’s trade.

But the real death knell came when large grocers pooled their resources together to form their own wholesale cooperatives. The combined purchasing power of coops let them buy in huge quantities at bargain rates that smaller wholesalers and coops could not match. Grocers or supermarkets naturally bought from their own coop because they owned shares in it and any profits were returned as dividends.

The same few blocks comprising that wild and woolly marketplace then and that make up the more cultivated Old Market today were, by comparison, virtually barren of people by the mid-1960s, the huge warehouse structures largely abandoned and fallen into disrepair. The open air City Market was closed by the City of Omaha in 1964.

The overall Market district was saved from the wreckage heap by the vision and action of a family with longstanding business and property interests in the area, the Mercers, and by other enterprising sorts who despaired losing this vital swath of Omaha history.

During the late ‘60s-early ‘70s what was once the produce center of Omaha began undergoing a transformation, building by building, block by block. The renovations continued to take hold over the better part of a decade. The labor intensive, working man’s market that revolved around fruit and vegetable sales gave way to head shops, galleries, theaters, and restaurants that appealed to the counter culture and sophisticated set. What is known now as the Old Market emerged and the area gained landmark preservation and historic status designations in 1979.

By the late ‘70s, people began moving into loft-style living spaces above storefronts, an update on an old tradition that increasingly gained new traction. So many Old Market buildings have since been converted into mixed uses, with apartments and condos on the upper floors and businesses on the ground floor, that today the district is more than just a commercial center and tourist destination, but a urban residential neighborhood as well.

Not every remnant of the early Market disappeared. At least one old-line vendor, Joe Vitale, hung on through the 1990s.

Character and Characters

Old-time sellers were usually loud, animated, sometimes gruff, and by any measure assertive in trying to reel buyers in for themselves and thus steer sales away from competitors. If a vendor thought a rival was out of line or infringing on his turf or undercutting prices or, God forbid, stealing sales, there might be heated words, even fisticuffs. Customers did not always get off easy either. Some old-time vendors took exception if someone fussily handled the merchandise without purchasing or questioned the quality or price of the goods.

Sam Epstein recalled the time that Independent Fruit Company partners Sam “Red” Wolfson and Louie Siporin had just unloaded a batch of tomatoes when Tony Rotollo walked up to pick over the goods.

“Old Man Rotollo apparently asked Sam the price of tomatoes and he told Sam it was too high. Sam, who was loud and had a temper, started raving. He had a voice you could hear from miles away. Sam yelled, ‘Too high, you SOB I’m treating you right. You get out of here and don’t ever come back.’ And Louie, the refined guy of the business, came running out and said, ‘For God’s sakes, Sam, don’t talk like that out here. You gotta call him an SOB, take him in the back room.’ And Sam said, ‘He’s an SOB out here, he’s an SOB in the back room.’ Well, Old Man Rotollo went on his way and about a half hour later was back buying tomatoes from Sam, the two of them getting along just fine.”

Another hot head Epstein treaded lightly around was a banana house operator known to chase out persons he disliked with a sharp, curved banana knife.

Vendors had to be more brazen then because: (1) for most of them this was their single livelihood and so every sale mattered; and (2) most merchants followed the tradition practiced back in the Old Country, where markets were more expressive, the competition more cut throat, where decorum was put aside and survival meant outshining and outshouting the vendor next to you or across from you. You had to have some chutzpah and some get-and-up-and-go initiative in order to make it.

The give-and-take haggling, bartering, and bickering, good-natured or not, that was part and parcel of the classic marketplace is largely a thing of the past these days. For the most part, people today pay whatever price is set for goods without making a fuss. It’s all very polite, all very pleasant, all very banal.

George Eisenberg and his brother Hymie worked with their father Ben in the Omaha City Market in the years before, during, and after World War II. The brothers’ father went into the wholesale business with Harry Roitstein and the Eisenberg and Roitstein Fruit Company survived into the 1950s and beyond.

One of the few other Jewish wholesalers to last that long was Greenberg Fruit Company. Don Greenberg joined his father Elmer in the family business in 1959. He said when he got involved most of the company’s buyers were small independent grocers, many of them Jewish and Italian. Even as late as ’59, Greenberg recalled, “parking places were at a premium” in the Market. Over time, the traffic trailed off, so much so that Greenberg Fruit left to build a new warehouse, in tandem with another Jewish wholesaler, Nogg Fruit Company, in southwest Omaha.

“When we moved out of the Market,” said Greenberg, “parking spaces were no longer at a premium and there were very few independent grocers left.”

The Eisenberg family’s produce dealings nearly spanned the arc of the Market, as the patriarch, Ben, went from peddler to vendor to wholesaler. Son George then took the business into an entirely new realm by specializing in the wholesale potato and onion field. He found a lucrative niche selling directly to food processors. But it all began with Ben and his horse and wagon, later his truck, and then the stalls on 11th and Jackson Street.

“My dad didn’t speak really sharp English because he came from the Ukraine. He didn’t speak any English when he got here, but he learned to speak survival English. Either you spoke the language or you starved to death. You had to make a living,” said George. “My dad was a really good salesman. He was very polite, businesslike, very fair. His word was his bond. He used to tell us when we were kids, ‘Don’t lie, cheat or steal.’ It pays off — people are happy to do business with you.”

Legacy, Heritage, History, Memories

As the proud son of a successful immigrant, Eisenberg is glad to see his old stomping grounds active again, filled with people jabbering, jostling, buying, and selling. But you cannot blame him for being a little wistful at the loss of the colorful, boisterous characters and antics that populated the Market back in the old days.

With sellers noisily touting their goods like carnival barkers, all packed tightly together in a kind of vendors row, each vying for the same finite customer base, there was an every-man-for-himself urgency to the proceedings. There was no place Eisenberg would have rather been.

“I felt that’s where all the action in Omaha was — in the Market,” he said. “I mean, people were shouting like, ‘Watermelon, watermelon, get your red, ripe and sweet watermelon.’ ‘Strawberries, strawberries, get your strawberries.’ ‘We’ve got Idaho potatoes here, 25 cents a basket.’ It was fun. They were all shouting to people walking in the Market to bring attention to their location. That was our advertisement — our voice.”

Occasionally, things would get a little too rambunctious for some tastes.

“The city had a market inspector, and he’d come down and tell us, ‘You guys are going to have it to hold it down. People are complaining that you’re making too much noise hawking the merchandise.’ Some people used to say that was the charm of the Market, yet some complained.

“So we’d tell him, ‘Well, we can’t sell the stuff unless they hear what we got to sell.’ And he’d say, ‘I know, but just keep it down.’”

Eisenberg said he and his mates would then talk in muted tones, at least while the inspector was still around, but once he went on his way they would go right back to shouting. It was the only way to be heard above the din.

A typical day on the Market was not your average 9-to-5 proposition. Most vendors arrived by 4 or 5 a.m. to sell to commercial buyers seeking the best, freshest picks of the day. “If we thought we were going to be busy we might open the doors at 3 a.m.,” said Don Greenberg. “It was not unusual to work until 5 or 6 in the evening.” Some wholesalers and vendors stayed even later if business was good or if they had an excess of product they wanted to turn over before the next business day.

Greenberg remembers card and dice games as popular distractions among some Market workers, who had their favorite hangouts in surrounding cafes and other creature comfort joints. Sam Epstein, whose family bought Nogg Fruit Company from Leo Nogg, recalled that the owner of Louie’s Market often sat in on a standing card game, leaving instructions that anyone who called the Market inquiring after him be told he had not been seen. Epstein recounted how a broker known to have dalliances with women at work worked out a system whereby a friend would “pound like hell” on a metal pole downstairs as a signal someone was coming to interrupt his latest conquest.

Epstein’s business dealings in the Market began as a supermarket buyer. He made the rounds down there selecting and buying quantities of produce from truck gardeners or farmers, including a Jewish man named Herman Millman. Epstein worked for Nogg for a time and later became a part owner, eventually buying him out. Epstein said he and his family kept the Nogg Fruit Company name intact because “it had 60 years of name recognition.”

He said in a market the size of Omaha’s word got around fast about who you could and could not trust in business dealings. “There’s no secrets around the Market,” Epstein said.

Everything was done on a handshake and verbal basis then. All the transactions figured in ledger books or in people’s heads.

As the independent grocers were dying off, Nogg Fruit got into the food service and frozen food business and flourished in this new niche.

The Market’s band of brothers hung on as long as they could before the business faded away. As the big operators and small entrepreneurs left, one by one, and then all together, soon only photographs, articles, and memories remained.

The brawny Industrial Era buildings that survive in new guises today are physical testament to what once went on there. But aside from a few signs on building walls, some produce scales, and maybe some hooks for hanging bunches of bananas, tangible evidence is hard to see.

If you just close your eyes, though, perhaps you can imagine it all: the dance and ritual of shipments coming and going out; displays of produce being loaded, unloaded, handled, and haggled over; the jabbering commerce playing out from pre-dawn to past dusk between men in jaunty hats, their cigarettes, cigars or pipes ablaze. It was a colorful, lively place to work in and to shop at.

And maybe, just maybe, if you happen by the Omaha Farmers Market some Saturday, in your mind’s eye you can picture an earlier scene that unfolded there, and know that all of it, past and present, is part of an unbroken line. Just like it has always been, it remains a place where people come together to buy and sell, bargain, and trade. The memory of what once was and what still is brings a smile to George Eisenberg’s face.

- Memories of the Jewish Midwest: Mom and Pop Grocery Stores, Omaha, Lincoln, Greater Nebraska and Southwest Iowa (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Enchanted Life of Florence Taminosian Young, Daughter of a Whirling Dervish (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Overarching Plan for North Omaha Development Now in Place, Disinvested Community Hopeful Long Promised Change Follows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Golden Boy Dick Mueller of Omaha Leads Firehouse Theatre Revival (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

A Story of Inspiration and Transformation: Though Living on the Margins, Aisha Okudi Gives Back, and She Nurtures Big Dreams for Her Esha Jewelfire Mission Serving Africa

Life is what you make of it, the saying goes. Attitude is everything, goes another. Aisha Okudi is living proof that when these aphroisms are put into action life can take on a whole new meaning and direction. By being intentional about how she apprehends the world, Okudi is no longer living the self-centered life that led to ruinous consequences. Her life today is focused on positive self-empowerment through service to others. That doesn’t mean hard things don’t still happen to her. But she’s much better equipped to handle what the world deals her in healthy ways rather than the destructive ways she used before. Her inspirational story of transformation and recovery is beginning to get her noticed. That has a lot to do with her charming personality, high-energy, and humanitarian vision. She has very little in the way of monetary means or material goods, yet she’s embarked on an international mission that she seems destined to fulfill. She’s not likely to let anything stand in her way either. You go, girl!

A Story of Inspiration and Transformation: Though Living on the Margins, Aisha Okudi Gives Back, and She Nurtures Big Dreams for Her Esha Jewelfire Mission Serving Africa

©by Leo Adam Biga

When buoyant, self-made social entrepreneur, visionary and humanitarianAisha Chemmine Mure Okudi reviews how far she’s come in only a few years she can hardly believe it herself. It’s not so much that her three-year old Shea Luminous by Esha Jewelfire line of organic shea butter bodycare products is such a thriving success. It’s more to do with her business being an expression of her ongoing recovery from unfortunate life choices and setbacks as well as a conduit for her African missionary work.

At the base of her products is butter extracted from the shea nut, a natural plant indigenous to the very rural West African provinces she serves.

After years helping poor African children from long-distance by sending supplies and donations, she visited Niger, West Africa for the first time last spring through the auspices of the international NGO, Children in Christ. She engaged children in arts and crafts and games and she enlisted the support of tribal leaders, church-based volunteers, Nigerian government representatives and American embassy officials. She purchased a missionary house to accommodate more evangelists.

She says she’s tried getting local churches on board with her missionary work but has been rebuked. She suspects being a woman of little means and not having a church or a title explains it. Undaunted, she works closely with CIC Niger national director, Festus Haba, who calls her work “a blessing.”

She intends returning to Africa in May. Her long-range plan is to move to Niger. She envisions growing her business enough to employ Africans and to open holistic herbal health clinics. She’s studying to be a holistic health practitioner.

Contrast this with the desperate young woman she was in 2004. The dissolute life she led then found her crying in an Iowa jail cell after her second Operating While Intoxicated offense. Her arrest came after she left the strip club where she performed, bombed out of her head.

“I had to get drunk so I could let these men touch me all night,” says Okudi, who ended up driving her car atop a railroad embankment, straddling the tracks and poised to head for a drop-off that led straight into a river.

The Des Moines native had been heading for a fall a long time. Growing up, her family often moved. Finances were always tight. She was a head-strong girl who didn’t listen to her restless mother and alcoholic father.

“There were issues at home. I was always told no coming up and I got sick of hearing that. I felt I was a burden, so I was like, ‘I’m going to get out and get my own stuff.'”

At 15 she left home and began stripping. A year later she got pregnant. She gave birth to the first of her four children at 17.

“I found myself moving around a lot. I really didn’t know what stability was. I never had stability, whether having a stable home or just being stable, period, in life. I was young and doing my thing. My dad walked in the club where I was stripping. My sister told on me.”

The confrontation that ensued only drew her and her parents farther apart.

“I was trying to live that life. I wanted to have whatever I wanted to have. My mom and dad struggled and we didn’t get everything I thought we needed, so I did my own thing. I danced, I sold my body and I made lots of money from it. I did it for about 12 years. I wanted to have it all, but it was not the right way.”

She got caught up in the alcohol and drug abuse that accompany this sordid life. Stealing, too.

“I was in and out of prison a lot. I used to steal to make money. I was in and out of trouble and the streets.”

She served a one year sentence for theft by receiving stolen property.

That night in jail seven years ago is when it all came to a head. “I just sat there and I thought about my kids and what I just did,” she says.

She felt sure she’d messed up one too many times and was going to lose her children and any chance of salvaging her life, “I was crying out and begging to God. I had begged before but this time it was a beg of mercy. I was at my bottom. I surrendered fully.”

To her great surprise and relief the judge didn’t give her jail time. “I told the judge, ‘I will never do this.’ He said, ‘If I ever see you in my courtroom again it will be the last time.’ I burnt my strip clothes when I got out, and I didn’t turn back. I got myself into treatment.” She’d been in treatment before but “this time,” she says, “it was serious. It wasn’t a game because it used to be a game to me. I enrolled in school.”