Archive

An Omaha Hockey Legend in the Making: Jake Guentzel Reflects on Historic Rookie Season

I am almost a year late in posting this Omaha Magazine profile I wrote about Omaha’s own Jake Guentzel and the amazing post-season tear he went on as a rookie with the Pittsburgh Penguins. Ha became a much bigger factor than anyone imagined in helping the team contend for the Stanley Cup. Guentzel and his Pittsburgh mates went on to win it of course, thus capping one of the most storybook rookie campaigns in NHL history and barely a season removed from starring for the UNO Maverick hockey program.

An Omaha Hockey Legend in the Making

Jake Guentzel Reflects on Historic Rookie Season

Story by Leo Adam Biga

Illustration by Derek Joy

Originally published in Omaha Magazine (http://omahamagazine.com/articles/an-omaha-hockey-legend-in-the-making/)

Former UNO hockey star Jake Guentzel left school in 2016, after junior year, to pursue his dream of playing professionally. No one expected what happened next.

The boyish newcomer with the impish smile went from nondescript rookie wing prospect to elite scorer during two seasons with the Wilkes-Barre/Scranton Penguins in the American Hockey League. Upon joining the parent Pittsburgh Penguins in November, he made an immediate splash. In his NHL debut, he scored a goal with his first shift. He followed with a goal on his third shift. Two shots—two goals.

By January, Guentzel secured a permanent seat in the NHL team’s locker room. The club showed faith, placing him on its top-scoring line alongside captain Sidney Crosby. The Crosby-Guentzel pairing proved pivotal in Pittsburgh’s second straight Stanley Cup win. Their team defeated Nashville four games to two in the finals.

Guentzel would make NHL playoffs history before hoisting the Stanley Cup overhead: His 13 postseason goals made him the first rookie to lead the NHL playoffs (five of those goals were game-winners); his 21 points tied the league rookie record for a postseason; and he became the second-ever rookie to score a hat trick in the playoffs.

UNO has produced several NHL players but Omaha hockey historian Gary Anderson says, “I don’t remember any who have had the same impact.”

Indeed, the Maverick who signed with Pittsburgh as a third-round, 2013 draft pick (77th overall) became the talk of the hockey world. He paired with future Hall of Famer Crosby to form a lethal scoring tandem on the NHL’s best team. He was in the running for playoffs MVP (Conn Smythe award) won by his superstar teammate.

His former coach at UNO, the recently retired Dean Blais, marvels at Guentzel’s exploits.

“It’s hard to explain,” Blais says. “I don’t think anyone would have forecast that. He played well in the American League, but he was up and down, and when that happens you don’t expect great things.”

Not from someone who would have been playing his senior year at UNO.

“Then he goes into Pittsburgh, has a pretty good season, and in the playoffs he’s a couple goals or points away from maybe winning the Conn Smythe. For Jake to step in and do that is pretty special,” Blais says.

Sharing it all was former UNO and current Penguins teammate Josh Archibald. They became the first Mavs to have their names engraved on the Stanley Cup.

Guentzel’s performance recalled what local icon Bob Gibson did as a St. Louis Cardinals pitcher in World Series competition half a century ago. Like Gibson, Guentzel is now an Omaha sports legend. The city has a legitimate claim on him, too. He was born in Omaha when his father coached the Omaha Lancers. His two older brothers, Ryan and Gabe, also played collegiately.

He’s the second Omaha native to reach the NHL (Jed Ortmeyer in 2003 was the first).

The local connection extends to Guentzel’s father assisting one season at UNO under Blais (in 2010-2011), while the younger Guentzel also helped lead UNO to its only Frozen Four in 2015.

Mere weeks removed from gaining hockey immortality with his improbable heroics, he unwinds from the spotlight with family in his other hometown of Woodbury, Minnesota.

“It’s hard to put into words what happened,” he says. “It was hard to soak it all in at some points. With each win, the media got more and more crazy. It was definitely a crazy journey.”

photo by Richard Gagnon, Omaha Athletics

Preparation meets success

Guentzel’s skill and mindset proved well-suited for hockey’s biggest stage.

Mike Kemp, UNO associate athletic director and former Mavericks coach, praises his “high hockey IQ.”

“What makes him a special player at the highest level is his ability to think his way around the ice,” Blais says. “His biggest asset is his playmaking ability and his ability to get to the net.”

Former UNO teammate Justin Parizek says Guentzel has long-mastered the mental aspects of the game: “He thinks the game really well. He’s always a couple steps ahead of the play.”

UNO hockey broadcaster Terry Leahy admires Guentzel’s pedigree: “He just knows the game, and that comes right from his father and his brothers. He was just built from the ground up. His dad had a huge influence on that. His two brothers were really good college hockey players.”

Parizek envies the extra push Guentzel got at home: “His whole childhood he was pushed trying to keep up with his older brothers. Keeping up with bigger, stronger guys gave him that competitive edge. His dad’s a really good coach, and having that 24-7 extra coach in his ear has given him insights into how he can do things better.”

Archibald says it’s no wonder Guentzel was ready to shine: “He’s been preparing his entire life for that moment. Everybody along the way has put their piece in with him, and he’s taken it all in.”

“He was definitely groomed well,” says another former UNO linemate, Austin Ortega.

Even Guentzel’s father, University of Minnesota associate head coach Mike Guentzel, says the moment is “never too big” for his son.

The rising star credits his family for giving him what he needed to excel. “They instilled ‘you gotta work every day.’ It definitely implanted in my brain,” Guentzel says.

He’s grateful they shared in his shining moments—from that memorable first NHL game to hoisting the Stanley Cup.

“It’s definitely a family thing. I realize all the sacrifice they put in for me over the years in everything they did. They’re always there for me,” he says.

Guentzel’s dad and siblings never got this far in hockey, but they’ve been with him each step of the journey.

“Whenever I need something, I can look up to them and realize they’ve been through similar situations over their hockey careers,” he says. “They’ve definitely been huge for me, and it’s definitely cool to share this with my family.”

When dreams come true

Growing up, Guentzel dreamed of winning the Stanley Cup, just like thousands of other kids.

“But to have it come true my first year in the NHL is definitely crazy. I mean, I never would have expected that. It’s pretty special,” he says.

Securing the championship against Nashville, he says, was “a night I’ll remember for the rest of my life.”

Archibald says the occasion of two Omaha hockey products being part of a title team didn’t escape them.

“For both of us to play together at UNO and then to take that next step together in Pittsburgh was a great experience,” Archibald says, adding that as the Stanley Cup got passed around, “there was a moment on the ice when we were standing next to each other, and Jake looked at me and said, ‘I can’t believe we’re here. To do this together is the best thing in the world.’”

photo courtesy of Pittsburgh Penguins

Mind over matter

As the playoffs wore on, more hype came Guentzel’s way. Except for texts referencing his newfound celebrity, he says, “I tried to stay away from that stuff. You don’t want to get caught up in what people are saying. I just try to focus on what’s at hand.” As for media, he “gives them what they want” and moves on.

The well-grounded athlete applies a pragmatic approach to the game.

“Each level you go up, the competition gets harder,” Guentzel says. “You have to do whatever it takes to get there—if it’s staying late after practice, doing extra work. That’s what I’ve always tried to do. Growing up, you go through bantams, high school, juniors, and college. I’ve just stayed with it. I’ve tried not to think ahead of what’s happening in the moment. It’s the way you have to think. If you don’t think that way, you don’t really want to play, and you don’t really love the game.”

Others attest to his dedication.

“Everything he’s accomplished is due to the hard work he put in himself,” Ortega says, “and he got rewarded.”

Archibald knows well the sacrifice: “It doesn’t come easy. You have a lot of pressure on your back. But he pushed through everything. I think one of the things that helps him is being one of the hardest workers in the room.”

Guentzel feels his approach is consistent. “It hasn’t changed much,” he says. “People are going to be coming after you, so you’ve got to make sure you’re ready every day for everyone’s best.”

What some term “pressure to perform in the clutch,” he considers “a chance to do something special. I think as a player you like those moments. They’re fun to be a part of,” he says.

Of his Penguins debut, Guentzel says, “There were nerves for sure, but you just gotta stick with what got you there. There was a lot of emotion running through me that night. I was just trying to make the most of the opportunity, and remembering that all the hard work I’ve put in has finally led to my dream coming true.”

He felt at home in his new digs. His space in the Pittsburgh locker room was just beside Crosby, who took the rookie under his wing.

“It’s cool that they all kind of take you in and make you feel comfortable right away,” Guentzel says of his veteran teammates. “I think that’s why they have so much success.”

His own even-keeled attitude helped with the season grind, too.

“You want to be a good player in the league, so you’ve got to do the little things and keep working on them every day,” Guentzel says. “You’ve just got to stay with it, stay positive, because you’re going to go through tough patches.”

Coming up big

In the playoffs, he kept making big assists and goals.

“I watched all the games at home with my family,” Parizek says, “and sometimes we were like, ‘Are you kidding me, he did it again?’ It was a surreal run for him, and I couldn’t be more happy and proud.”

Guentzel’s scoring binge was out of character for someone reluctant to shoot in college.

“When I was at UNO, coach got upset with me that I was passing too much,” he says. “I was kind of a playmaker, and I always looked for the next play. As my career went on, I started to shoot more. I think I finally realized if I shoot more maybe I can score some more goals.”

“He’s a pass-first guy,” Blais confirms. “For three years we tried to get him to be a little bit more selfish, and when the opportunity’s there, shoot it.”

Making that transition in the NHL is unusual.

“That’s a credit to Sidney Crosby,” Guentzel says. “You’re just trying to find areas on the ice where he can get you the puck because he can pretty much get it to you wherever you’re at. I was very fortunate.”

Blais agrees Guentzel found the right mentor.

“I think when it really clicked is when he started playing with Sidney Crosby,” Blais says. “It’s one thing playing for Pittsburgh, but it’s another thing for Sidney Crosby to want this 22-year old kid to play with him. That’s pretty special when the best player in the world wants Jake Guentzel as his linemate because he knows Jake plays the same way.

And I’m sure Sidney Crosby said, ‘Hey, Jake, when I get a pass from you, I’m going to shoot, and when you get it from me, you shoot.’ I mean, that’s the way it works. I think when Jake learned how to move and shoot the puck at the highest level is when he took off. Credit to Jake and his coaching staff but probably the most influential was Sidney Crosby.”

photo courtesy of Pittsburgh Penguins

Finding a coach and expanding his game

Despite not being the scorer his coach wanted, Guentzel treasured playing for Blais: “He was huge for me. I can’t thank him enough for all he did for me. He rounded out my game. He made me realize that to play every day you have to be at your top. That’s a big thing he impacted me with. I wouldn’t be the player I am today if I didn’t play in Omaha for him.”

Leaving after his junior year did not come lightly. “It was tough leaving Omaha for sure,” he says. “I just thought I was ready for the next challenge. It all worked out.”

Blais says being the close hockey family the Guentzels are, they made the decision jointly and he fully supported it. “Jake’s always been that player that has reached the highest level. He did it in college and now he’s doing it in the NHL. He’s one of the top players I’ve coached in all my years of coaching.”

UNO broadcaster Terry Leahy recalls Guentzel “began his college career the way he began his NHL career. “He had an assist right off the bat his first game as a Maverick—and he was on his way. The biggest memory I have of him is that his anticipation and passing skills were unbelievable.”

“He started out like gangbusters,” Blais remembers. “He broke Greg Zanon’s assist record his first year. Even though other teams were keying on him with their best players, Jake still managed to get his points. Even in the NHL, playing against the other team’s top line, Jake still managed to make plays and to get his goals.”

“He’s a complete package mentally and physically,” Leahy says. “He can fly, shoot, pass. I wouldn’t be surprised to see him wearing a [captain’s] letter for the Penguins in the not-too-distant future. He’s very mature…and he’s a pot-stirrer. He can chirp [trash talk] with the best. He was a little restrained his first year in the NHL, but there were moments in the finals you could see him starting to get under some Nashville skins. That’s definitely a part of his game. He’s got that baby face, but he can spring those horns pretty quickly after a whistle.”

photo by Mark Kuhlmann, Omaha Athletics

His UNO hockey family

Guentzel is happy his playing, not talking, is raising UNO’s national profile. “I only think it’s going to make the school become even more of a hockey place and have people realize Omaha’s on the rise,” he says.

“It’s a huge step for UNO hockey,” Archibald agrees. “It kind of puts it on the map in an unprecedented way.”

Leahy says with Guentzel and Archibald in the finals “UNO was on display through the whole run.” The fact that they are Stanley Cup winners “will be huge for recruiting.” UNO’s Mike Kemp and new hockey head coach Mike Gabinet have echoed such sentiments.

Austin Ortega takes inspiration from Guentzel’s example. “Seeing him do so well has definitely given me a little extra motivation and expectation to reach that goal and do what he’s done,” Ortega says.

Guentzel has not forgotten his UNO hockey family. “I keep in touch with them almost every day. They’re close friends. They’re definitely special to me,” he says.

“He has a lot of support back in Omaha and wherever his old teammates are,” Ortega says. “Myself and two other guys saw him for games three and four in Nashville. He was just the same old kid that we knew.”

“He’s not going to change, he’s not going to be cocky or arrogant about it,” Justin Parizek says. “He’s still going to go about his business and be the great guy he is and treat everyone the same.”

photo by Joe Sargent, Pittsburgh Penguins

Making his mark

Dean Blais can still hardly believe what transpired.

“To get his name on the Stanley Cup, to get a championship ring, to go from making $80,000 to $800,000, plus the Cup bonus. Not bad for a kid right out of college,” Blais says. “Everything looks bright for his future.”

Guentzel doesn’t think he’s arrived yet.

“I’ve still got to establish my spot,” he says, speaking with Omaha Magazine in June. “I’m still a young guy. I’ve got to go and try to make the team out of camp. You never know what’s going to happen, so you’ve just gotta try and make a name for yourself and do what it takes to stay at that level. You can’t take it for granted because there’s someone right behind who’s going to try to take your spot.”

Archibald senses Guentzel is hungry to “go back out there and prove to everybody he can do it again—I have all the faith in the world he’s going to be able to do it.”

“You gotta enjoy it, because it’s a once in a lifetime opportunity,” Guentzel says.

Visit nhl.com/penguins for more information.

This article was printed in the September/October 2017 edition of Omaha Magazine.

Giving a helping hand to Nebraska greats

Giving a helping hand to Nebraska greats

©story by Leo Adam Biga

©photos by Bill Sitzmann

Appears in the March-April 2018 issue of Omaha Magazine ( http://omahamagazine.com/ )

Memory-makers.

That’s what former Husker gridiron great Jerry Murtaugh calls the ex-collegiate athletes whose exploits we recall with larger-than-life nostalgia.

Mythic-like hero portrayals aside, athletes are only human. Their bodies betray them. Medical interventions and other emergencies drain resources. Not every old athlete can pay pressing bills or afford needed care. That’s where the Nebraska Greats Foundation Murtaugh began five years ago comes in. The charitable organization assists memory-makers who lettered in a sport at any of Nebraska’s 15 universities or colleges.

“All the money we generate goes into helping the memory-makers and their families,” says Murtaugh.

Its genesis goes back to Murtaugh missing a chance to help ailing ex-Husker star Andra Franklin, who died in 2006. When he learned another former NU standout, Dave Humm, was hurting, he made it his mission to help. Murtaugh got Husker coaching legend Tom Osborne to endorse the effort and write the first check.

“The foundation has been a source of financial aid to many former Huskers who are in need, but also, and maybe equally important, it has helped bind former players together in an effort to stay in touch and to serve each other. I sense a feeling of camaraderie and caring among out former players not present in many other athletic programs around the country,” Osborne says.

The foundation’s since expanded its reach to letter-winners from all Nebraska higher ed institutions.

By the start of 2018, more than $270,000 raised by the foundation went to cover the needs of 12 recipients. Three recipients subsequently died from cancer. As needed, NGF provides for the surviving spouse and children of memory-makers.

The latest and youngest grantee is also the first female recipient – Brianna Perez. The former York College All-America softball player required surgery for a knee injury suffered playing ball. Between surgery, flying to Calif. to see her ill mother, graduate school and unforeseen expenses, Perez went into debt.

“She found out about us, we reviewed her application and her bills were paid off,” NGF administrator Margie Smith says. “She cried and so did I.”

It’s hard for still proud ex-athletes to accept or ask for help, says all-time Husker hoops great Maurtice Ivy, who serves on the board. Yet they find themselves in vulnerable straits that can befall anyone. Giving back to those who gave so much, she says, “is a no-brainer.”

The hard times that visit these greats are heartbreaking. Some end up in wheelchairs, others homeless. Some die and leave family behind.

“I cry behind closed doors,” Murtaugh says. “One of the great ones we lost, a couple weeks before he passed away said, ‘All I’m asking is take care of my family.’ So, we’re doing our best. What I’m proud of is, we don’t leave them hanging. Our athlete, our brother, our sister has died and we just don’t stop there – we clear up all the medical bills the family faces. We’re there for them.”

“We become advocates, cheerleaders and sounding boards for them and their families,” Smith says. “I am excited when I write checks to pay their bills, thrilled when they make a full recovery and cry when they pass away. But we’re helping our memory makers through their time of need. Isn’t this what life is all about? “

Smith says the foundation pays forward what the athletes provided us in terms of feelings and memories.

“We all want to belong to something good. That is why the state’s collegiate sports programs are so successful. We cheer our beloved athletes to do their best to make us feel good. We brag about the wins, cry over the losses. The outcome affects us because we feel a sense of belonging. These recipients gave their all for us. They served as role models.

“Now it’s our turn to take care of them.”

Murtaugh is sure it’s an idea whose time has come.

“Right now, I think we’re the only state that helps our former athletes,” he says. “Before I’m dead, I’m hoping every state picks up on this and helps their own because the NCAA isn’t going to help you after you’re done. We know that. And that’s what we’re here for – we need to help our own. And that’s what we’re doing.”

Monies raised go directly to creditors, not recipients.

He says two prominent athletic figures with ties to the University of Nebraska – Barry Alvarez, who played at NU and coached Wisconsin, where he’s athletic director, and Craig Bohl, who played and coached at NU, led North Dakota State to three national titles, and now coaches Wyoming – wish to start similar foundations .

Murtaugh and his board, comprised mostly of ex-athletes like himself, are actively getting the word out across the state end beyond to identify more potential recipients and raise funds to support them. He’s confident of the response.

“We’re going to have the money to help all the former athletes in the state who need our help, Athletes and fans are starting to really understand the impact they all make for these recipients. People have stepped up and donated a lot of money. A lot of people have done a lot of things for us. But we need more recipients. We have some money in the bank that needs to be used.”

Because Nebraska collegiate fan bases extend statewide and nationally, Murtaugh travels to alumni and booster groups to present about the foundation’s work. Everywhere he goes, he says, people get behind it.

“Nebraskans are the greatest fans in the country and they back their athletes in all 15 colleges and universities. It’s great to see. I’m proud to be part of this, I really am.”

Foundation fundraisers unite the state around a shared passion. A golf classic in North Platte last year featured the three Husker Heisman trophy winners – Johnny Rodgers, Mike Rozier, Eric Crouch – for an event that raised $40,000. Another golf outing is planned for July in Kearney that will once more feature the Heisman trio.

Murtaugh envisions future events across the state so fans can rub shoulders with living legends and help memory-makers with their needs.

He sees it as one big “family” coming together “to help our own.”

Visit nebraskagreatsfoundation.org.

Huskers’ Winning Tradition: Surprise Return to the Top for Nebraska Volleyball

Huskers’ Winning Tradition: Surprise Return to the Top for Nebraska Volleyball

©by Leo Adam Biga

©Photography by Scott Bruhn

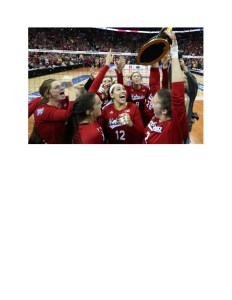

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln volleyball team entered 2017 with tempered expectations after losing three All-Americans and two assistant coaches from the previous season. But what began as a rebuilding year became a 32-4 national championship campaign for the overachieving Huskers, who capped an unexpected return to the pinnacle of their sport by defeating Florida in four sets in the NCAA title match on Dec. 16.

Thousands of Big Red fans made the trip to Kansas City for the Final Four, where a record crowd of 18,000-plus viewed the deciding contest.

While tradition-rich Husker football has been in the doldrums for two decades, the equally tradition-rich volleyball program has carried the school’s elite athletic banner. NU volleyball and its gridiron brothers have now won five NCAA titles apiece. This was NU’s second volleyball crown in three years and the fourth under head coach John Cook since succeeding program architect Terry Pettit in 2000.

Cook was an assistant under Pettit, whose stellar work at Nebraska—including one NCAA title (along with his overall contributions to the sport)—landed him in the American Volleyball Coaches Association Hall of Fame back in 2009. The current Huskers volleyball coach joined his predecessor as an inductee in the fall of 2017. Cook’s formal induction came only hours before facing the No. 1 seed Penn State in the semifinals of the NCAA Tournament.

Cook has said the 2017 Huskers, led by Papillion native and setter extraordinaire Kelly Hunter, were a joy to coach because they actually lived out their season slogan: “with each other, for each other.” That mantra got tested early when the young, inexperienced squad opened the season without an injured Hunter on the court and promptly suffered two losses—one against future NCAA finals opponent Florida. But the Huskers stayed the course and with Hunter back at setter the rest of the way, they rallied to finish the non-conference schedule with a 7-3 mark. The team really found its groove in tough Big Ten play, going 19-1 to share the league championship with arch-rival Penn State, and finished the regular season 26-4.

Hunter and fellow seniors Briana Holman (middle blocker) and Annika Albrecht (outside hitter) led the way with junior outside hitter Mikaela Foecke and junior libero Kenzie Maloney. Two dynamic freshmen—middle blocker Lauren Stivrins and outside hitter Jazz Sweet—rounded out the balanced team volleyball approach that became NU’s trademark. No superstars. Just solid players executing their roles and having each other’s backs, whether at the net or in the back-row.

Hunter, Albrecht, and Foecke did earn All-America honors.

Months before seeing Penn State in the semifinals, on Sept. 22, NU dealt the No. 1-ranked and star-studded Nittany Lions their only regular-season loss by sweeping them at Happy Valley. The Huskers earned the right to host a first-round NCAA Tournament playoff in Lincoln, where fans jammed the Devaney Center. Fifth-seeded NU swept both its foes to advance to regionals in Lexington, Kentucky, where NU downed Colorado and host Kentucky, dropping only one set in the process.

For their national semifinal match in K.C., the Huskers drew Big Ten nemesis and No. 1 overall seed Penn State. In an epic classic, the Big Red prevailed in five sets. Then, in the ensuing final against Florida, NU avenged that early season loss to the Gators in capturing collegiate volleyball’s top prize. Hunter and Foecke were named co-outstanding players of the tournament.

In 2018, NU loses Hunter, Holman, and Albrecht—look for at least one to be the latest Husker to make the U.S. national team—but the team otherwise returns with the core stable of their 2017 championship team. NU will add four top recruits to the mix, too. As defending champs, no one will underestimate the Huskers this time. A key to the season will be finding a setter to replace Hunter, the team’s on-court quarterback. Incoming freshman Nicklin Hames may just be the heir apparent in that key role.

But you can bet that Cook & Co. will stress the benefits of playing team volleyball in search of another title.

To learn more about how volleyball has become the top sport in Nebraska (and how Omaha plays an important role in the talent pipeline) be sure to pick up the January/February edition of Omaha Magazine featuring my cover story. Or link to the story here: https://leoadambiga.com/2018/01/21/the-state-of-vol…rican-volleyball/

The State of Volleyball: How Nebraska Became the Epicenter of American Volleyball

The State of Volleyball: How Nebraska Became the Epicenter of American Volleyball

©by Leo Adam Biga

©Photography by Bill Sitzmann

Originally published in Jan-Feb 2018 issue of Omaha Magazine

For generations, football gave Nebraska a statewide identity. But with Husker gridiron fortunes flagging, volleyball is the new signature sport with booming participation and success.

Here and nationally, more girls now play volleyball than basketball (according to the National Federation of State High School Associations).

“It’s the main or premier sport for women right now,” Doane University coach Gwen Egbert says.

Omaha has become a volleyball showcase. The city hosted NCAA Division I Finals in 2006, 2008, and 2015, with the Cornhuskers competing on all three occasions (winning the national title in 2006 and 2015).

Packed crowds at the CenturyLink Center will once again welcome the nation’s top teams when Omaha hosts the championships in 2020. Meanwhile, Creighton University is emerging as another major volleyball powerhouse, and the University of Nebraska-Omaha has made strides in the Mavericks’ first two years of full Division I eligibility since joining the Summit Conference.

In the 2017 NCAA tournament, Creighton advanced to the second round (but fell to Michigan State). As this edition of Omaha Magazine went to press, the Cornhuskers headed to regionals in hopeful pursuit of a fifth national championship.

“The fact Nebraska has done and drawn so well, and that kids are seeing the sport at a high level at a young age, gets people excited to play,” says Husker legend Karen Dahlgren Schonewise, who coaches for Nebraska Elite club volleyball and Duchesne Academy in Omaha.

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln first reached a national title game with Schonewise in 1986. The dominant defensive player set Nebraska’s career record for solo blocks (132)—a record that still stands—before going on to play professionally. (The Cornhuskers didn’t win the national championship until 1995.)

“I think the amount of kids that play in Nebraska is No. 1, per capita, in the country. I think the level of play is far higher than many states in the country,” says Omaha Skutt Catholic coach Renee Saunders, whose star freshman, 6-foot-3 Lindsay Krause, is a UNL verbal commit.

Volleyball’s attraction starts with plentiful scholarships, top-flight coaching, TV coverage, and professional playing opportunities.

Few states match the fan support found here.

“We have probably the most educated fans in the nation,” Saunders says. “They’re a great fan base. They know how to support their teams, and they’re very embracing of volleyball in general.”

The lack of physical contact appeals to some girls. The frequent team huddles after rallies draw others.

Omaha Northwest High School coach Shannon Walker says “the camaraderie” is huge. You really have to work together as a unit, communicate, and be six people moving within a tiny space.”

Volleyball’s hold is rural and urban in a state that has produced All-Americans, national champions, and Olympians.

The Husker program has been elite since the 1980s. Its architect, former UNL coach Terry Pettit, planted the seeds that grew this second-to-none volleyball culture.

“He really spearheaded a grassroots effort to build the sport,” says Creighton coach Kirsten Bernthal Booth. “Besides winning, he also worked diligently to train our high school coaches.”

“It’s important to realize this goes back many years,” former Husker (2009-2012) Gina Mancuso says, “and I think a lot of credit goes to Terry Pettit. He created such an awesome program with high standards and expectations.”

Pettit products like Gwen Egbert have carried those winning ways to coaching successful club and high school programs and working area camps. Egbert built a dynasty at Papillion-LaVista South before going to Doane. Several Papio South players have excelled as Huskers (the Rolzen twins, Kelly Hunter, etc.).

Their paths inspired future Husker Lindsay Krause.

“Seeing the success is a big motivation to want to play,” Krause says. “Just watching all the success everyone has in this state makes you feel like it’s all the more possible for you to be able to do that.”

Many top former players go on to coach here, and most remain even after they achieve great success.

Walker says quality coaches don’t leave because “it’s the hotbed of volleyball—they’re staying here and growing home talent now.”

“It’s us colleges that reap the benefits,” Bernthal Booth says.

Pettit says it’s a matter of “success breeds success.”

Schonewise agrees, saying, “Once you see success, others want to try it and do it and more programs become successful.”

“The standard is high and people want to be at that high level. They don’t want to be mediocre,” UNO coach Rose Shires says.

Wayne State, Kearney, Hastings, and Bellevue all boast top small college programs. In 2017, Doane was the first Nebraska National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics program to record 1,000 wins.

“We’ve got great Division I, Division II, NAIA, and junior college volleyball programs,” says Bernthal Booth, who took the Creighton job in part due to the area’s rich talent base. She feels CU’s breakout success coincided with the 2008 opening of D.J. Sokol Arena, which she considers among the nation’s best volleyball facilities.

“All these colleges in Nebraska are in the top 25 in their respective divisions,” Saunders says. “It’s crazy how high the level of play has gone, and I think it’s going to keep going that way.”

“It’s really built a great fan base of support,” Mancuso says, “and I think the reason the state produces a lot of great volleyball players is the fact we have great high school coaches, great college programs, and great club programs.”

Club programs are talent pipelines. There are far more today than even a decade ago. Their explosion has meant youth getting involved at younger ages and training/playing year-round. Nebraska Elite is building a new facility to accommodate all the action.

“The athleticism found in the state has always been pretty high, but the level of play has definitely improved. The kids playing today are more skilled. The game is faster,” Egbert says. “When I started out, you’d maybe have one or two really good players, and now you could have a whole team of really good players.”

“You have your pick of dozens of clubs, and a lot of those clubs compete at the USA national qualifiers and get their players that exposure,” says Shannon Walker, the Northwest High School coach who is also the director of the Omaha Starlings volleyball club.

“Volleyball is such a joy to be a part of in this state,” Mancuso says.

“It’s cool to be a part of everything going on in Nebraska and watching it grow and develop,” Skutt freshman phenom Krause says.

“My goal is to make Lindsay ready to play top-level Division I volleyball by the time she graduates here,” Saunders says. “She already has the physicality, the competitive edge, the smarts. Now it’s just getting her to play to her full potential, which she hasn’t had to yet because she’s always been bigger than everybody. She’s definitely not shy of challenges. I feel like every time I give her a challenge, she steps up and delivers.”

Krause values that Saunders “gives great feedback on things I have to fix.”

Native Nebraskans dot the rosters of in-state and out-of-state programs. Along with Krause, Elkhorn South freshman Rylee Gray—who holds scholarship offers from Nebraska and Creighton—may emerge as another next big name from the Omaha metro. But they are both still a few years from the collegiate level.

UNO’s Shires says “impassioned” coaches like Saunders are why volleyball is rooted and embraced here. Shires came to Omaha from Texas to join the dominant program Janice Kruger built for the Mavericks at the Division II level. Kruger, now head coach at the University of Maryland, was previously captain of the Cornhuskers’ team (1977).

Further enhancing the volleyball culture, Shires says, is having former Olympian Jordan Larson and current pro Gina Mancuso come back and work with local players. Mancuso’s pro career has taken her around the world. She wants the players she works with at UNO, where she’s an assistant, to “see where it can take them.”

As volleyball has taken off, it’s grown more diverse. Most clubs are suburban-based and priced beyond the means of many inner-city families. The Omaha Starlings provide an alternative option. “Our fees are significantly lower than everybody else’s,” says Walker, the club’s director and Northwestern’s coach. “Anybody that can’t afford to pay, we scholarship.”

Broadening volleyball’s reach, she says, “is so necessary. As a result, we do have a pretty diverse group of kids. I’ve had so many really talented athletes and great kids who would have never been able to afford other clubs. We’re trying to even the scale and offer that same experience to kids who have the interest and the ability but just can’t afford it.”

“It’s very exciting to see diversity in the sport—it’s been a long time coming,” Schonewise says.

Forty-five Starlings have earned scholarships, some to historically black colleges and universities. Star grad Samara West (Omaha North) ended up at Iowa State.

Starlings have figured prominently in Omaha Northwest’s rise from also-ran to contender. Eight of nine varsity players in 2017 played for the club.

Walker knew volleyball had big potential, yet it’s exceeded her expectations. She says while competition is fierce among Nebraska coaches and players, they share a love that finds them, when not competing against each other, cheering on their fellows in this ever-growing volleyball family/community.

“It’s awesome,” Walker says. “But I don’t think we’ve come anywhere close to reaching our peak yet.”

From couch potato to champion pugilist

From couch potato to champion pugilist

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in December 2017 issue of El Perico (el-perico.com)

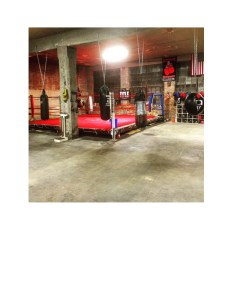

No one expected nationally ranked amateur fighter Juan Vazquez, 17, to be the poster boy for how boxing can transform your life. Four years ago, the now Ralston High senior was an obese couch potato who preferred video games over physical activity.

Even after his mother practically dragged him to Jackson’s Boxing Club in south downtown, where his older brother trained, he cut up rather than worked out. Head coach Jose Campos expected Vazquez to quit when he pushed him hard in training. But Vazquez took everything Campos and assistant coach Christian Trinidad dished out and came back for more. He rapidly shed pounds and learned ring skills. Mere months after getting serious, he fought bouts – and won.

“I tend to pick things up quickly,” Vazquez said.

Campos knew he had someone special when Vazquez kept beating or nearly beating more experienced foes.

“It inspired him to get better because he knew that if he could compete with these high level kids with his little experience then he was going to be something, and he did. He started to work really hard.”

Vazquez won Silver Gloves regionals and twice won Ringside youth world championships. Then he became a national Junior Olympic champion at 152 pounds in West Virginia. He’s now a USA team hopeful eyeing the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan.

No one’s more surprised than Vazquez himself.

“I never thought I would compete like this nationally, but as the years went by I’ve shown I’m really good at it. What I love most about the sport is that it keeps me in shape and it makes me a better person. Every day I try my hardest in everything I do. It just gets me through my days when I’m stressed.

“It’s always there for me. It’s made me into the person I am today. I’m doing good at school. I’m healthy, I’m eating right. It teaches you things you can use in real life. It’s taught me a lot about discipline When I train, I don’t cheat myself. If I don’t train hard, that’s going to end up turning into failure.”

Campos confirmed Vazquez is a quick study.

“He picks things up more and faster than other kids. When Juan goes into a fight, it takes him a round or half a round to feel out the other kid. He’s looking for mistakes they’re making, for flaws in their game, and once he sees it, he works off that.”

Reading opponent tendencies shows a cerebral side.

“I see everything,” Vazquez said. “I’m jabbing, feeling how hard they hit, what their favorite punch is, what are they throwing often, and how can I counter all that.”

Campos said Vazquez can adapt thanks to unusual versatility.

“If Juan notices he needs to go forward, he’s really good at going forward. If he notices he needs to box and move around, he’s really good with his footwork. If he needs to switch from right-handed to left-handed, he will do that, and be just as good, which is pretty impressive. You only see that from high level professional fighters.”

This complete package compels Campos to sing his prodigy’s praises.

“He’s smart, he’s calm and he’s super tough – physically and mentally. There is no quit in him. It’s rare. He’s one of those kids where if he sticks with it, he’s going to be a world champion for sure.”

Vazquez, who’s trained with world champion Terrence Crawford of Omaha, said, “I want to make this my career. I honestly want to pursue it for the rest of my life, I’m willing to take it all the way – as far as I can.”

His family supports him right down the line.

“They tell me to pursue it. When they see me fighting, they see I have the potential to be one of the greatest in the sport. I see it, too. They see that boxing has really helped me with my life – with just everything.”

Even though he has his mom to thank for introducing him to the gym, he’s taken it far beyond her imagination.

“She never thought it’d be like this.”

She’s happy for his success but can’t bring herself to watch him fight,

“She’s scared to see me getting hit. She never wants me getting hurt. She’s really protective over me.”

Only his pride was hurt when he lost in the semi-finals ofa national tournament in Tennessee.

“I thought it was a really close fight, but you can’t really be mad at anybody but yourself. You just have to go back to the gym and start training again.”

Campos feels too much time off hurt his boxer.

“He didn’t get to fight in between the Junior Olympics (in July) and this tournament (in October) because we couldn’t find him any opponents, so he got rusty.

“This kid needs to be active.”

Vazquez is in training now for a December tournament in Salt Lake City, Utah that will decide the USA boxing team for upcoming international competitions.

“That’s where I really need to bring it because that’s the one that’s going to determine who’s going to take that spot,” Vazquez said.

With a fighter who’s come so far, so fast, it’s no wonder Campos uses Vazquez as an example to others.

“I love that he does it,” Vazquez said. “It shows kids there is a chance for you to be slimmer and to up your lifestyle. It’s not all about eating junk food and playing games. You have to work out to keep your body in shape to live a healthier and better life.”

The nonprofit Jackson’s Boxing Club, 2562 Leavenworth St., holds fundraisers and accepts donations to send kids like Juan to competitions.

For details, visit jacksonsboxingclub.com.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

Terence Crawford, Alexander Payne and Warren Buffett: Unexpected troika of Nebraska genius makes us all proud

Terence Crawford, Alexander Payne and Warren Buffett:

Unexpected troika of Nebraska genius makes us all proud

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Terence “Bud” Crawford has fought all over the United States and the world. As an amateur, he competed in the Pan American Games. As a young pro he fought in Denver. He won his first professional title in Scotland. He’s had big fights in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in Orlando, Florida, in Arlington, Texas. He’s showcased his skills on some of the biggest stages in his sport, including the MGM Grand in Las Vegas and New York City’s Madison Square Garden. He’s even traveled to Africa and while he didn’t fight there he did spend time with some of its boxers and coaches. But he’s made his biggest impact back home, in Omaha, and starting tonight, in Lincoln. Crawford reignited the dormant local boxing community with his title fights at the CenturyLink Center and he’s about to do the same in Lincoln at the Pinnacle Bank Arena, where tonight he faces off with fellow junior welterweight title holder Julius Indongo in a unification bout. If, as expected, Crawford wins, he will have extended his brand in Nebraska and across the U.S. and the globe. And he may next be eying an even bigger stage to host a future fight of his – Lincoln’s Memorial Stadium – to further tap into the Husker sports mania that he shares. These are shrewd moves by Crawford and Co. because they’re building on the greatest following that an individual Nebraska native athlete has ever cultivated. Kudos to Bud and Team Crawford for keeping it local and real. It’s very similar to what Oscar-winning filmmaker Alexander Payne from Omaha has done by bringing many of his Hollywood productions and some of his fellow Hollywood luminaries here. His new film “Downsizing,” which shot a week or so in and around Omaha, is about to break big at major festivals and could be the project that puts him in a whole new box office category. These two individuals at the top of their respective crafts are from totally different worlds but they’re both gifting their shared hometown and home state with great opportunities to see the best of the best in action. They both bring the height of their respective professions to their own backyards so that we can all share in it and feel a part of it. It’s not unlike what Warren Buffett does as a financial wizard and philanthropist who brings world-class peers and talents here and whose Berkshire Hathaway shareholders convention is one of the city’s biggest economic boons each spring. His daughter Susie Buffett’s foundations are among the most generous benefactors in the state. He has the ear of powerbrokers and stakeholders the world over Buffett, Payne and Crawford represent three different generations, personalities. backgrounds and segments of Omaha but they are all distinctly of and for this place. I mean, who could have ever expected that three individuals from here would rise to be the best at what they do in the world and remain so solidly committed to this city and this state? They inspire us by what they do and motivate us to strive for more. We are fortunate that they are so devoted to where they come from. Omaha and Nebraska are where their hearts are. Buffett and Crawford have never left here despite having the means to live and work wherever they want. Payne, who has long maintained residences on the west coast and here, has never really left Omaha and is actually in the process of making this his main residence again. This troika’s unexpected convergence of genius – financial, artistic and athletic – has never happened before here and may never happen again.

Let’s all enjoy it while it lasts.

Omaha warrior Terence Crawford wins again but his greatest fight may be internal

_8.jpg)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Terence Crawford defeats Felix Diaz to retain his 140-pound world championship and to remain unbeaten.

That’s all well and good, but as Crawford is discovering, life outside the ring comes with consequences, too, and the streets that forged him are still a part of him and can, if he’s not careful, bring him down. His life, like all of ours, is a complicated business. The fact he’s come so far so fast from where he started and where he still has roots is causing him to be in situations that in some cases he’s ill-prepared to deal with. He’s straddling vasty different worlds and trying to keep his equilibrium and integrity in them. It’s a work in progress playing out on a national and international stage. The head-strong Crawford would be well-served to listen to the advice of the wise people who’ve come forward to counsel him. Yes, he needs to be his own man, but he also needs to acknowledge when he’s out of his depth. No one any longer questions his boxing genius. Or his heart for his community and for his family and friends. As for the rest of it, only time will tell.

He is a warrior or soldier, it’s true, and much of that combative spirit is admirable, but it also has its costs. Sometimes, it’s the exact thing you don’t need or want to be. Sometimes, the opposite is called for. Sometimes, it’s more courageous and certainly smarter to back off or to deliberate or to live to fight another day, another time, another round. It’s a quality he shows in the ring. He needs to show that same quality outside the ring, too.

For three perspectives on the forces that have shaped him and that make him the endlessly complex individual he is, you might want to check these out–

https://www.nytimes.com/…/terence-crawford-world-champion-profile.html

https://leoadambiga.com/tag/terence-crawford/

New approach, same expectation for South soccer

Omaha South High boys soccer is good again. No news there. By now, it’s become a tradition. In a you-can’t-take-anything-for-granted world, few things have become more dependable in Omaha high school sports than this program competing for district and state honors. It’s not exactly a given but at this point the team is expected to win every time out no matter who they play, no matter how few returning starters there on the roster, no matter who’s injured. The 2017 team lacks experience and suffered some key injuries before the season even began and yet the expectations both inside and outside the program remain high. As in get-to-the-state-tournament and win- it-all high. South did it last year and a couple years before tha, toot. The Packers have been in the hunt for the title several other years. Coach Joe Maass has a full-blown dynasty on his hands and he’s trying to learn from the past to help keep his latest defending champion squad hungry and peaking at the right time. Here’s an El Perico story I wrote in late March laying out how Coach Maass sees his team shaping up.

New approach, same expectation for South soccer

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

Lessons learned when Omaha South boys soccer won it all in 2013 inform the way coach Joe Maass does things now following last year’s second state title. He not only draws on that earlier experience but on a recent family challenge and the expertise of fellow coaches.

Heavy graduation losses from last year’s championship team have him invoking “a Bill Belichick approach.” he said, referring to the New England Patriots head coach. “The Patriots don’t always have the best players yet he’ll grab somebody’s second-team player or a late round draft pick and make them a fit for his system, We’ve focused a lot more on working hard in practice then maybe we did the year after we won it the first time.”

Hard work rubs off the youth on so many new faces.

“We feel like our talent level could drop off because we’re younger,” Maass said. “We only have four or five seniors, so we’ve had to just kind of bring a blue-collar mentality to it.”

He said his Packers reflect South Omaha’s personality.

“Blue-collar tough. That’s South Omaha to me. We’re not the biggest, but we’ll bang with you if you want.”

Attitude’s everything for this perennial power everyone wants to take down.

“These guys have to remember they play for South. Every team we play approaches it like the World Cup, so we can’t let up or coast. The fact we’re defending state champions just adds to it. The first time we won it we took it serious but I didn’t realize how serious it had to be. This time it’s been more of a business-like approach.”

Twin brothers Issac and Israel Cruz, along with Emilio Margarito, are top returnees who model high expectations.

“Those guys get it. The trick is getting some of the younger guys to. Like we’re starting a freshman and a sophomore. But a lot of new players are buying into the culture those older guys set. It’s good to see.”

Regarding the Cruz boys, he said, “They’ve been starting since their freshman year. They’ve always been leaders. Everyone respects them. It’s just how it is.

They set the standard.”

“Same thing for Emilio Margarito. He’s a team captain now.”

Maass believes in open competition at practice. Nobody’s spot is guaranteed.

“If they don’t work hard, they’ll be called out. Every day you’re competing.”

This year even more so because of injuries.

“There’s been a lot of attrition – more than we’ve had in years. One of the things we talk about is next man up.”

That mantra’s extended from preseason tryouts for open spots to now and it’s already paid dividends.

With returning goalkeeper Adrian Feliz out due to injury, his spot came down to two players until one quit. That gave the job to Jeramiah Gonzales, whose brilliant opening weekend performance included a shutout of Burke in his first career start, followed by five stops of penalty kicks in a shootout against South Sioux City.

“Extraordinary,” is how Maass described what Gonzales did. “I’ll probably never see it in my lifetime again.”

He said when Felix comes back, he won’t automatically step into the starter role. He’ll have to earn it.

“They will be competing every day.”

Joe Maass

Since Maass adopted next-man-up as a team philosophy, he said, “it feels like things are working better – there’s a lot more team harmony.” He added, “Back in the day, with some hot shot kids who wanted to do things their way it caused problems. We might have won, but it wasn’t fun.”

Forward Jose Hernandez is another player who, Maass said, “gets it.” “He was promoted from the sophomore team to the varsity for the Tennessee (Smoky Mountain) tournament last year and he scored the goal that helped us beat one team. He scored the first goal at state last year coming off the bench. He knows this is what you have to do. It’s not how many minutes you get, it’s what you do with them.”

Now in his 18th year, Maass has learned patience.

“We tell our kids, ‘Don’t worry about the first few games, let’s worry about games 17-18.’ As long as we’re clicking at the end, it doesn’t even matter what we’re doing right now. We just have to figure each other out and get better every day.”

His own priorities got a reality check last year when his wife Ann, an ESL instructor at South, was diagnosed with breast cancer. Chemo treatments and a double mastectomy later, the cancer’s in remission.

“When it first hits you, your whole life just kind of spins.”

During Ann’s illness he took a more active hand in their two young children’s lives and extracurricular activities.

“I even contemplated stepping down as coach to be a better family man but at the end of the day we managed it, and here I am. I want to win games and championships but helping younger kids is probably more important after this.”

Having taken South soccer from the bottom to the top, he’s focused on maintaing excellence.

“I just want to keep it moving along.”

He readily acknowledges assistant coaches have helped South become a dynasty.

“I’m not afraid to go out and find someone who challenges me as a coach and who on top of that can run drills and do things at a higher level than myself.

“We evolve with every coach we bring in.”

By May, South aims to win its district, return to state and compete for another title. Packer coaches, players and fans expect it. But, Maass said, “the key is to get there.”

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

The end of a never-meant-to-be Nebraska football dynasty has a school and a state fruitlessly pursuing a never-again-to-be-harnessed rainbow

The end of a never-meant-to-be Nebraska football dynasty has a school and a state fruitlessly pursuing a never-again-to-be-harnessed rainbow

©by Leo Adam Biga

Let’s start with the hard truth that the University of Nebraska never had any business being a major college football power in the first place. Don’t get me wrong, NU had every right to ascend to that lofty position and certainly did what it takes to deserve the riches that came with it. But my point is NU was never really meant to be there and therefore fundamentally was always out of its class or at least out of place even when it reigned supreme in the gridiron wars.

The fact is it happened though. Call it fate or fluke, it was an unlikely, unexpected occurrence whose long duration made it even more improbable.

In pop culture, self-identification terms, it was both the best thing that ever happened to the state of Nebraska and the worst thing. The best because it gave Nebraskans a mutual statewide rooting interest and point of pride. The worst because it was all an illusion doomed to run its course. Furthermore, it set Nebraskans up for visions of grandeur that are sadly misplaced, especially when it comes to football, because the deck is stacked against us. Far better that we aspire to be the best in something else, say wind energy or the arts or agriculture or education, that we can truly hold our own in and that reaps some tangible, enduring benefit, then something as inconsequential, tangential and elusive as football.

Husker football became a vehicle for the aspirational hopes of Nebraskans but given where things are today with the program those aspirations read more like pipe-dreams.

The critical thing to remember is that it was only because an unrepeatable confluence of things came together at just the right time that the NU football dynasty occurred in the first place. NU’s rise from obscurity to prominence took place in a bubble when peer school programs were in a down cycle and before that bubble could be burst enough foundation was laid to give the Huskers an inside track at gridiron glory.

The dynasty only lasted as long as it did because the people responsible for it stayed put and the dynamics of college football remained more or less stable during that period, thus prolonging what should have been a short rise to prominence and postponing the rude awakening that brought NU football back down to earth,.

Please don’t point to the program as the reason for that remarkable run of success the Huskers enjoyed from 1962 through 2001. It was people who made it happen. The program was the people. Once the people responsible for the success left, the results were very different. I mean, there’s never stopped being a program. It’s the people running the program who make all the difference, not the facilities or traditions.

Yes, I know there was a time when NU was successful in football prior to Devaney. From the start of the last century through the 1930s the Huskers fielded good, not great teams before the death valley years of the 1940s and 1950s ensued. But NU was never a titan the way Notre Dame, Minnesota, Michigan, Ohio State or other elite programs were back then.

Make no mistake about it, Bob Devaney was the architect of the wild success that started in the early 1960s and continued decade after decade. He deserves the lion’s share of credit for the phenomena that elevated NU to the heights of Oklahoma, Texas and Alabama. Without him, it would not have happened. No way, no how. His path had to cross Nebraska’s at that precise moment in time in the early 1960s or else NU would have remained an after-thought football program that only once in a while would catch fire and have a modicum of success. In other words, Nebraska football would have been what it was meant to be – on par with or not quite there with Kansas, Iowa, Missouri, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Colorado and Wyoming. During NU’s half-century run of excellence the state schools in those states not only envied NU but despised the Big Red because they couldn’t understand why that same magic didn’t happen with their football operations. Among those states, all but Wyoming have larger population bases. Among the Division I schools, all but Wyoming have larger student enrollments. Those realities alone should have put NU at a decided disadvantage and given those schools a leg up where football was concerned.

But Devaney found ways to compensate for the lack of bodies, not to mention for all the other disadvantages facing Nebraska. One of Devaney’s chief strategies for overcoming these things became national recruiting and eventually the recruitment of African-American student-athletes in enough numbers to be a difference-maker on the field.

The continuity of Devaney’s staff was an important factor in sustaining success.

His hand-picked successor Tom Osborne was like the apprentice who learned from the master to effectively carry on the tradition without so much as one bad season. Osborne ramped up the national recruiting efforts and especially made African-American recruits more of a priority. Like his mentor, he maintained a cohesive staff around him. He also made even greater use of walk-ons than Devaney had in that no scholarship limit era. And most importantly he saw the future and embraced an ahead-of-its-time strength and conditioning program that made NU players bigger and stronger, no doubt with some help from steroids, and he eventually adopted the spread option on offense and the 4-3 on defense, emphasizing speed and quickness on both sides of the ball. The option-based, power running and play-action passing game became NU’s niche. It allowed the program to recruit to a style and identity that stood it apart. Now, NU runs a variation of what virtuarlly everybody else does in college football, thus giving it one decided less advantage.

As long as was one or the other – Devaney or Osborne – or both were still around, the success, while not guaranteed, was bound to continue because they drove it and they attracted people to it.

First Devaney died, then Osborne retired and then athletic director Bill Byrnes left The first two were the pillars of success as head coaches and Devaney as AD. The third was a great support. There were also some supportive NU presidents. Osborne’s curated successor, Frank Solich, and other holdover coaches managed a semblance of the dynasty’s success. And then one by one the pretenders, poor fits, revisionists and outliers got hired and fired.

Ever since Osborne stepped down, NU has been playing a game it cannot win of trying to recapture past success by attempting to replicate it. That’s impossible, of course, because the people and conditions that made that success possible are irrevocably different. Whatever manufactured advantages NU once possessed are now long gone and the many intrinsic disadvantages NU has are not going away because they are, with the exception of coaches and players, immutable and fixed.

Besides Nebraska being situated far from large population centers, the state lacks many of the attributes or come-ons other states possess, including oceans, beaches, mountains, cool urban centers filled with striking skylines and features and a significant African-American and diversity presence on campus. It also lacks a top-shelf basketball program to bask in. And while NU has kept up with the facilities and programs wars the Huskers’ peer institutions now possess everything they have and more.

The dream of NU fans goes something like this: Get the right coach, and then the right players will come, and then the corresponding wins and titles will follow. Trouble is, finding that right coach is easier said than done, especially at a place like Nebraska. The university has shown it’s not willing to shell out the tens of millions necessary to hire a marquee coach. I actually applaud that. I find abhorrent the seven figure annual salaries and ludicrous buy-out guarantees paid to major college coaches. I mean, it’s plain absurd they get paid that kind of money for coaching a game whose intrinsic values of teamwork, discipline, hard work, et cetera can be taught in countless other endeavors at a fraction of the cost and without risk of temporary or permanent injuries. If NU stands pat and doesn’t play the salary wars game, then that leaves the next scenario of offering far less to an up and coming talent who, it’s hoped, proves to be the next Devaney or Osborne. Fat chance of that fantasy becoming reality.

The other wishful thinking is that some benefactor or group of benefactors will pump many millions of dollars, as in hundred of millions of dollars, into the athletic department in short order to help NU buy success in the form of top tier coaches and yet bigger, fancier facilities. There are certainly a number of Nebraskans who could do that if they were so inclined. I personally hope they don’t because those resources could go to far more important things than football.

In terms of head coaches, NU hit the jackpot with Devaney. He then handed the keys to a man, in Osborne, who just happened to be the perfect one to follow him, NU has missed on four straight passes since then. I count Mike Riley as a miss even though he’s only two years into his tenure because someone with his long coaching record of mediocrity does not suddenly. magically become a great coach who leads teams to championships just because he’s at a place that used to win championships. What Riley did in the CFL has no bearing on the college game.

Even if Riley does manage more success here than he’s been able to accomplish elsewhere, everything suggests it would be short-lived and not indicative of some enduring return to excellence. That once in a school’s lifetime opportunity came and went for NU, never to return in my opinion.

Sinking resources of time, energy and money into retrieving what was lost and what really wasn’t NU’s to have in the first place is a futile exercise in chasing windmills and searching for an elixir that does not exist.

Far better for NU to cut its losses of misspent resources and tarnished reputation and accept its place in the college football universe as a Power Five Conference Division I also-ran than to covet something beyond its reach. Having been to the top, that’s a tough reality for NU and its fans to accept. Far better still then for NU to swallow the bitter pill of hurt pride and do the smart thing by dropping down to the Football Championship Subdivision, where it can realistically compete for championships that are increasingly unattainable at the Football Bowl Subdivision. If it’s really all about the process, pursuing excellence and building character, and not about getting those alluring TV showcases and payouts, those mega booster gifts and those sell-outs, then that’s where the priority should be. If it’s about developing young men who become educated, productive, good citizens and contributors to society, then that certainly can be done at the FCS level. Hell, it can be done better there without all the distractions and hype surrounding big-time football.

This isn’t about quitting or taking the easy way out when the going gets rough, it’s about getting smart and honestly owning who you are, what you’re ceiling is and making the best use of resources.

Nebraskans are pragmatic people in everything but Husker football. With this state government facing chronic budget shortfalls. corporate headquarters leaving and a brain drain of its best and brightest in full effect, it seems to me the university should check its priorities. I say let go of the past and embrace a new identity whose future is less sexy but far more realistic and more befitting this state. Sure, that move would mean risk and sacrifice, not to mention criticism and resistance. It would take leadership with real courage to weather all that.

But how about NU leading the way by taking a bold course that rejects the big money and fat exposure for a saner, stripped-down focus on football without the high stakes and salaries and hysteria? Maybe if NU does it, others will follow. Even if they don’t, it’s the right thing to do. Not popular or safe, but right.

When has that ever been a bad move?

A case of cognitive athletic dissonance

A case of cognitive athletic dissonance

©by Leo Adam Biga

Like a lot of you out there who root for the athletic programs of all three in-state universities competing at the Division I level, I’m feeling conflicted right now. While it does my heart good to see the Creighton men’s and women’s hoops teams seeded so high in the NCAA Tournament, and this coming off strong performances by the Bluejay men’s soccer and women’s volleyball teams, I’m disappointed that both the University of Nebraska’s men’s and women’s basketball teams suffered historic losing seasons and didn’t stand a chance of making the Big Dance. The fact is that every major Husker men’s team sport – basketball, football and baseball – is in a down cycle. Indeed, among revenue generating sports in Lincoln, only volleyball is a year-in and year-out winner with the national prestige and conference-NCAA titles to show for it.

NU softball is still competitive but it’s been a long time since one of its teams has made a real run in the NCAA Tournament.

On the men’s side, NU used to be able to point to nationally relevant programs across the board as a selling tool to recruits. That just isn’t the case anymore. Baseball has been adrift for a while now and it doesn’t look like Darin Erstad has what it takes to make it a College World Series contender again.

|

Men’s hoops in Lincoln has been a joke for a long time now and it’s no longer funny. The succession of coaches from the early 1980s on has bred instability and NU just can’t seem to get it right in terms of hiring the right person for the job. Many of us suspect the real problem is a lack of institutional will and support to make basketball a priority of excellence. While the men have not been able to get their act together, we could usually count on the women to get things right. Yes, the program did go through some bumps with its own succession of coaches before reaching new heights under Connie Yori but then it all unraveled in seemingly the space of one chaotic season that saw Yori forced out amidst a scandal and player revolt. Where it goes from here under Amy Williams is anybody’s guess but a 7-22 record was not exactly a promising start, though she admittedly stepped into a program riddled with personnel holes and damaged psyches. Williams has the pedigree and track record to resurrect the program but how it collapsed so suddenly is still a shock.

Even the volleyball program. though still a perennial national contender, has lost ground to Creighton’s program. That’s actually a good thing for not only CU but the entire state and for the sport of volleyball in Nebraska. It’s another indicator of just how strong the volleyball culture is here. But I’m not sure NU ever thought CU would catch up in volleyball. The Bluejays have. The two programs are very close talent-wise and coaching-wise. In fact it’s become readily evident the Bluejays possess the potential to overtake the Huskers in the near future, many as soon as this coming season.

Then there’s the Omaha Mavericks. Its linchpin hockey program just lost its most important tie to national credibility with coach Dean Blais retiring. He got the Mavs to the promised land of the Frozen Four. Will whoever his successor ends up being be able to get Omaha back there and make the program the consistent Top 20 contender the university expects? Only time will tell. Since that run to the Frozen Four in 2015, hockey’s taken a decided step back, but the Omaha men’s basketball program has shown serious signs that it could be the real bell-weather program before all is said and done. Omaha came up just short in securing an automatic berth in the NCAA Tournament but still had post-season options available to it only to say no to them, which is strange given the university is desperate for a nationally relevant athletics program.

Ever since Omaha made the near-sighted decision to drop both football and wrestling, which were its two most successful men’s sports, the university has hung all its athletics fortunes on hockey. Now that hockey has seemingly plateaued and lost its legendary leader, basketball becomes the new hope. But basketball is a crowded field nationally speaking and no Maverick sport other than hockey has ever really caught on with Omahans. I would like to think that Omaha Maverick hoops could but I won’t believe it until I see it.

With basketball still struggling to find a following despite its recent rise, I bet university officials are wishing they still had wrestling and football around to balance the scales and give Omaha athletics more opportunities for fan support and national prestige. The way the NU football program has continued to struggle, a kick-ass Omaha gridiron program at the Football Championship Subdivision level would sure be welcome right about now. Omaha could have kept football and potentially thrived as a FCS powerhouse. But NU regents, administrators and boosters didn’t want Omaha to potentially sap Big Red’s fan and recruiting base. Too bad, because the two programs could have found a way to co-exist and even benefit each other.

Shawn Eichorst

Bruce Rasmussen

Trev Alberts

All of which takes us back to Creighton. Of the three in-state DI universities, CU’s proven to have the best contemporary model for successful, competitive and stable athletics. The Bluejays have built sustainable, winning men’s and women’s programs and they’ve found the right coaches time after time. Other than two major misses in Willis Reed and Rick Johnson, CU men’s basketball has been remarkably well led for more than 50 years. Women’s hoops has enjoyed the same kind of continuity and leadership over the last 35 years. And so on with the school’s other athletic programs. Over a long period of time the one constant has been Bruce Rasmussen, a former very successful coach there whose performance as athletic director has been nothing short of brilliant.

Culture is everything in today’s thinking and CU’s culture borne of its values-based Jesuit legacy and direction is rock solid and unchanging. This small private school has turned out to be the strongest in-state DI athletic department in the 2000s. Rasmussen’s excellent hires and big picture vision, plus the support of university presidents, have given the Bluejays a foundation that NU must envy. Even CU’s drastically upgraded facilities now favorably compare to or exceed NU’s.

Trev Alberts at UNO has proven a stronger administrator as athletic director than anyone on the outside looking in imagined, but I believe, though he’ll never admit it, that he regrets or will regret giving up the two programs that meant the most to the university. Even with that miscue, he’s built a firm foundation going forward. Baxter Arena is a nice addition but there’s no proof yet that area fans will pack it for UNO athletics other than hockey. If hoops doesn’t fly there, then UNO basketball is never going to capture fans the way it deserves to and that’s a shame.

Nebraska, meanwhile, stands on shaky ground. This is the weakest spot NU’s been in, in terms of overall athletic success, since the late 1960s-early 1970s. When other sports struggled then, the Husker athletic department always had its monolithic football program to fall back on, bail it out and keep it afloat. After nearly a generation of below par results, if things don’t dramatically change for the Big Red on the field and soon then NU’s once automatic crutch is in danger of no longer being there. If there’s no elite basketball program to pick up the football slack, NU athletics has nothing left to hang its hat on. Does anyone really have faith that NU athletic director Shawn Eichorst is making the right moves to return NU to where it once was? A lot of what’s come down is beyond his control, but the hires he makes are very much in his control. The four big questions are whether Mike Riley, Darin Erstad, Amy Williams and Tim Miles are the right coaches leading their respective programs. My opinion is that Riley is not. The sample size at NU is still too small to justify letting him go now but his overall career record indicates he won’t get done here what he couldn’t do elsewhere. Erstad has had enough time on the job and I’m afraid his excellence as a player hasn’t transferred to coaching. He’s got to go. Williams will likely prove to be a very good hire as she rebuilds the women’s hoops program. Miles is, like Riley, a guy who’s shown he has a limited ceiling as a coach and I’m afraid he’s been at NU long enough to show he can’t get the Huskers past a certain threshold. He should not have been retained.

All this uncertainity is weakening the Husker brand. Part of any brand is an identity and in college athletics that identity is often set by the head coach. Right now, it’s hard to get behind any of these coaches because, as an old expression goes, there’s no there-there. Winning sure helps but even when NU wasn’t winning big in basketball and baseball, it had some coaches who stood out. Joe Cipriano brought some verve and passion the way Danny Nee did. Cipriano got sick and had to step down as coach. Nee eventually wore out his welcome but he sure made things interesting. Between them was Moe Iba, whose own dour personality and his team’s deliberate style of play turned off many, but the man could coach. Everyone after Nee has been a let down as a coach and as a brand maker. John Sanders turned NU baseball around but he ended up alienating a lot of people. Dave Van Horn took things to a new level before he was inexplicably fired. Mike Anderson continued the surge until he too was let go after only a couple down seasons.

When NU was dominant in football and nationally competitive in basketball and baseball, tickets were hard to come by. Boy, have times changed. Yes, NU still mostly draws well at home, but not like the old days. A few more losing seasons and it will start to be a sorry sight indeed with all the empty seats.