Archive

Walter Reed: Former hidden child survives Holocaust to fight Nazis as American GI

About nine years ago I was given the opportunity to meet and profile Walter Reed, whose story of escaping the Final Solution as a Hidden Child in his native Belgium and then going on to fight the Nazis as an American GI a few years later would make a good book or movie. Here is a sampling of his remarkable story now, more or less as it appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). You’ll find many more of my Holocaust survival and rescue stories on this blog.

Walter Reed: From out of the past – Former hidden child survives Holocaust to fight Nazis as American GI

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Imagine this: The time is May 1945. The place, Germany. The crushing Allied offensive has broken the Nazi war machine. You’re 21, a naturalized American GI from Bavaria. You’re a Jew fighting “the goddamned Krauts” that drove you from your own homeland. Five years before, amid anti-Jewish fervor erupting into ethnic cleansing, you were sent away by your parents to a boys’ refugee home in Brussels, Belgium. Eventually, you were harbored with 100 other Jewish boys and girls in a series of safe houses. You are among 90 from the group to survive the Holocaust.

Relatives who emigrated to America finagle you a visa and, in 1941, you go live with them in New York. You abandon your heritage and change your name. Within two years you’re drafted into the U.S. Army. At first, you’re a grunt in the field, but then your fluency in German gets you reassigned to military intelligence, attached to Patton’s 95th Division, interrogating German POWs. If this were a movie, you’d be the avenging Jewish angel meeting out justice, but you don’t. “The whole mental attitude was not, Hey, I’m a Jew, I’m going to get you Nazi bastard,” said Walter Reed, whose story this is. “I had no idea of revenging my parents. We were really more concerned about our survival and getting the information we needed.”

By war’s end, you’re in a 7th Army unit rooting out hardcore Nazis from German institutions. You don’t know it yet, but your parents and two younger brothers have not made it out alive. You borrow a jeep to go to your village. Your family and all the other Jews are gone. You demand answers from the cowed Gentiles, some you know to be Nazi sympathizers. You intend no harm, but you want them scared.

“I wasn’t the little Jewish boy anymore,” said Reed. “Now, they saw this American staff sergeant with a steel helmet on and with a carbine over his shoulder. At that point, we were the conquerors and those bastards better knuckle under or else. I asked, What happened to my family and to the other Jewish people? They told me they were sent to the east into a labor camp. That’s about all I could find out.”

It is only later you learn they were rounded-up, hauled away in wagons, and sent to Izbica, a holding camp for the Sobidor and Belzec death camps, one or the other of which your family was killed in, along with scores of friends and neighbors.

Walter Reed, now 79, is among a group of survivors known as the Children of La Hille, a French chateau that gave sanctuary to he and his fellow wartime refugees. A resident of Wilmette, Il., Reed and his story have an Omaha tie. After the war, he graduated from the prestigious University of Missouri School of Journalism and it was as a fund raising-public relations professional he first came to Omaha in the mid-1950s when he led successful capital drives at Creighton University for a new student center and library. “Part of me is in those buildings,” he said.

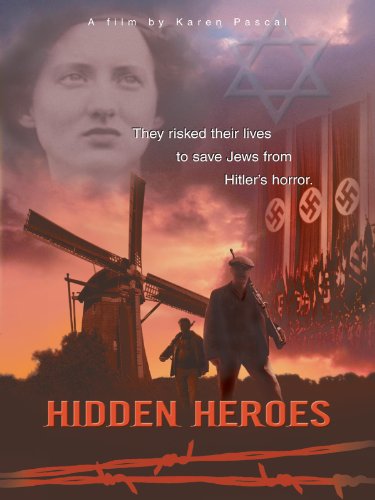

More recently, he began corresponding with Omahan Ben Nachman, who brings Shoah stories to light as a board member with the local Hidden Heroes of the Holocaust Foundation. A friend of Nachman’s — Swiss scholar and author Theo Tschuy — led him to accounts of La Hille and those contacts led him to Reed. In Reed, Nachman found a man who, after years of burying his past, now embraces his survivor heritage. With Reed’s help, Tschuy, the author of Dangerous Diplomacy: The Story of Carl Lutz and His Rescue of 62,000 Jews, is researching what will be the first full English language hardcover telling of the children’s odyssey.

On an April 30 through May 2 Hidden Heroes-sponsored visit to Nebraska, Reed shared the story of he and his comrades, about half of whom are still alive, in presentations at Dana College in Blair, Neb. and at Omaha’s Beth El Synagogue and Field Club, where Reed, a Rotary Club member, addressed fellow Rotarians. A dapper man, Reed regales listeners in the dulcet tones of a newsman, which is how he approaches the subject.

“I’m a journalist by training. All I want is the facts,” he said, adding he’s accumulated deportation and arrest records of his family, along with anecdotal accounts of his family’s exile. “I’m simply overwhelmed by the wealth of information that exists and that’s still coming out. In the last 10 years I’ve found out an awful lot of what happened. I don’t have any great details, but I have vignettes. So, my feeling when I find out new things is, Hey, that’s terrific, and not, Oh, I can’t handle it. None of that. Long, long ago I got over all the trauma many survivors feel to their death. I vowed this stuff would never disadvantage me.”

As he’s pieced things together, a compelling story has emerged of how a network of adults did right amid wrong. It’s a story Nachman and Reed are eager for a wider public to know. “It shows how a dedicated group of people, most of whom were not Jewish, coordinated their actions to prevent the Nazis from getting at these Jewish children,” said Nachman, who paved the way for the upcoming publication of a book by a La Hille survivor. “They chose to do so without promise of any reward but out of sheer humanitarian concern. It’s a story tinged in tragedy because the children did lose their families, but one filled with hope because most of the children survived to lead productive lives.”

It was 1939 when Reed made the fateful journey that forever separated him from his parents and brothers. Born Werner Rindsberg in the rural Bavarian village of Mainstockheim, Reed was the oldest son of a second-generation winemaker-wine merchant father and hausfrau mother. His was among a few dozen Jewish families in the village, long a haven for Jews who paid local land barons a special tax in return for protection from the anti-Semitic populace. Reed said Jews enjoyed unbothered lives there until 1931-1932, when Nazism began taking hold.

“I was aware of the growing menace and danger when I was about 8 or 9 years old. I recall constant conversations between my parents and their Jewish peers about Hitler. The Nazis marched up and down our main street with their swastika flags and their torches at night, singing their songs. This was a very close-knit community of about 1,000 inhabitants and you knew which kid had joined the Hitler Youth and whose dad was a son-of-a-bitch Nazi. Pretty soon, the kids began to chase us in the street and throw stones at us and call us dirty names. Then, the first (anti-Jewish) decrees came out about 1934 and increasingly got stricter.”

Pogroms of intimidation began in earnest in the mid-1930s. Reed remembers his next door neighbor, a prominent Jewish entrepreneur, taken away to Dachau by authorities “to scare the hell out of him. It saved his life, too,” he said, “because that hastened his decision to get the hell out of Germany. This stuff was going on in other towns and villages where I had relatives. In those places, including where my mother’s brothers and sisters lived, the local Nazis were more rabid and…they hassled the Jews so much they left, and it saved their lives.”

Things intensified in November 1938 when, in retaliation for the assassination of a German diplomat by an expatriate Polish Jew outraged by the mistreatment of his people, the Nazis unleashed a terror campaign now known as Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass). Roving gangs of brown-shirted thugs attacked and detained Jewish males, vandalizing, looting, burning property in their wake. Reed, then 14, and his father were dragged from their home and thrown into a truck with other captives. As the truck rumbled off, Reed recalls “thinking they were going to take us down to the river and shoot us or beat the hell out of us.” The boys among the prisoners were confined in the jail of a nearby town while the men were taken to Dachau. Reed was freed after three nights and his father after several weeks.

|

| The barn near Toulouse, France, where Walter Reed stayed as part of a children’s rescue colony |

In that way time has of bridging differences, Reed’s recent search for answers led him to a group of school kids in Gunzenhausen, a Bavarian town whose Jewish inhabitants met the same fate as those in his birthplace. The kids, whose grandparents presumably sanctioned the genocide as perpetrators or condoned it as silent witnesses, have studied the war and its atrocities. Reed began corresponding with them and then last year he and his wife Jean visited them. He spoke to the class, and to two others in another Bavarian town, and found the students a receptive audience.

“Frankly,” he said, “I find these encounters very worthwhile and uplifting. I was told by the teachers and principals it was quite a moving experience for the students to come face-to-face with history. My visit is now on the web site created by one class. On it, the students say they were especially moved by my stated conviction that the most important lesson of these events is to hold oneself responsible for preventing a repetition anywhere in the world and that each of us must bear that responsibility.”

When his father returned from Dachau, Reed recalls, “He looked awful. Emaciated. He wasn’t the same man. When we asked him what it was like he just said he’s not going to talk about it.” It was in this climate Reed’s parents decided to send him away. He does not recollect discussions about leaving but added, “I recently found a letter my father wrote to somebody saying, ‘I finally persuaded Werner to leave,’ so I must have been reluctant to go.”

A question that’s dogged Reed is why his parents didn’t get out or why they didn’t send his brothers off. It’s only lately he’s discovered, via family letters he inherited, his folks tried.

“Those letters tell a story,” he said. “They tell about their efforts to try and get a visa to America. My dad traveled to the American consulate in Stuttgart and waited with all the other people trying to get out. They gave my parents a very high number on the waiting list, meaning they were way down on the queue. There are anguished letters from my father to relatives referencing their attempts to get my brothers out, but that was long after it was too late. In no way am I castigating my parents for making the wrong decision, but they could have sent my brothers (then 11 and 13) because in that home in Brussels we had boys as young as 5 and 6 whose parents sent them.”

|

| Walter Reed, third from right in the front row, at the chateau in La Hille, France, where a smaller group of children were transferred from the barn near |

Home Speyer, in the Brussels suburb of Anderlecht, is where Reed’s journey to freedom began in June 1939. Sponsored by the city and afforded assistance by a Jewish women’s aid society, the home was a designated refugee site in the Kinder transport program that set aside safe havens in England, The Netherlands and Belgium for a quota of displaced German-Austrian children. Where the transport had international backing and like rescue efforts had the tacit approval of German-occupied host countries, others were illegal and operated underground. Reed said the only precautions demanded of the La Hille kids were a ban on speaking German, lest their origins betray them as non-French, and a rule they always be accompanied outside camp grounds by adult staff. Despite living relatively in the open, the children and their rescuers faced constant danger of denouncement.

The boys at Home Speyer, like the girls at a mirror institution whose fates would soon be mingled with theirs, arrived at different times and from different spots but all shared a similar plight: they were homeless orphans-to-be awaiting an uncertain future. Reed doesn’t recall traveling there, except for changing trains in Cologne, but does recall life there. “For a young boy from a small Bavarian farm village,” he said, “Brussels was an exciting city with its large buildings, department stores, parks and museums. We made excursions into the beautiful Belgian countryside. And there was no more anti-Semitic persecution.”

This idyll ended in May 1940 when German forces invaded Belgium. Reed said the director of the girls home informed the boys’ home director she’d secured space on a southbound freight train for both contingents of children.

“We packed what we could carry and took the streetcar to the train station,” he notes. “Late that night two of the freight cars were filled by the 100 boys and girls as the train began its journey to France.”

Adult counselors from the homes came with them. The escape was timely, as the German army reached Brussels two days later. En route to their unknown destination, Reed said the roads were choked with refugees fleeing the German advance. Unloaded at a station near Toulouse, the children were trucked to the village of Seyre, where a two-story stone barn belonging to the de Capele family quartered them the next several months. It appears, Reed said, the de Capeles had ties to the Red Cross, as the children’s homes did, which may explain why that barn was chosen to house refugees.

“It lacked everything as a place to live or sleep,” he said. “No beds, no mattresses, no running water, no sanitary facilities, no cooking equipment. Food was scarce, Pretty soon we ran out of clothes and shoes. Everything was rationed. A lot of us had boils, sores and lice.”

|

| Walter Reed with a close friend who would perish not long thereafter |

With 100 kids under tow in primitive, cramped conditions, the small staff struggled. “They were trying to manage this rambunctious group of kids, who played and fought and caused mischief. The older kids, myself included, were deputized to sort of manage things. We taught classes out in the open. We worked on nearby farms in the hilly, rolling countryside, cutting brush…digging potatoes. For compensation we got food to bring back. It was like summer camp, except it was no picnic,” he said. “We all grew up fast. We learned about survival, self-reliance and cooperation for the common good.”

It was not all bad. First amours bloomed and fast friendships formed. Reed struck up a romance with Ruth Schuetz Usrad, whose younger sister Betty was also in camp. He also found a best friend in Walter Strauss.

The barn’s occupants were pushed to their limits by “the harsh winter of 1940,” Reed said. They got some relief when the group’s Belgian director, Alex Frank, got the Swiss Children’s Aid Society, then aligned with the Swiss Red Cross, to put Maurice and Elinor Dubois in charge of the Seyre camp, which they soon supplied with bedding, furniture and Swiss powdered milk and cheese.

With the Nazi noose tightening in the spring of 1941 the Dubois relocated the children to an even more remote site — the abandoned 15th century Chateau La Hille, near Foix in the Ariege Province — where, Reed said, “they were less likely to be detected.” It was here the children remained until either, like Reed, they got papers to leave or, like others, they dispersed and either hid or fled across the border. Some 20 children came to the states with the aid of a Quaker society.

As chronicled in various published stories, Reed said that in 1942, a year after he left, 40 of the children, including his girlfriend Ruth, were arrested by French militia and imprisoned at nearby Le Vernet. Inmates there were routinely transported to the death camps and this would have been the children’s fate if not for the intervention of Roseli Naef, a Swiss Red Cross worker and the then La Hille director, who bicycled to Le Vernet to plead with the commandant for their release. When her entreaties fell on deaf ears, she alerted Maurice Dubois, who bluffed Vichy authorities by threatening the withdrawal of all Swiss aid to French children if the group was not freed.

The officials gave in and the children spared. Reed said he has copies of records documenting Naef’s termination by the Swiss Red Cross for her role as a rescuer of Jews, the kind of punitive disapproval the Swiss were known to employ with other rescuers, such as diplomat Carl Lutz.

In getting out when he did, Reed realizes he “was one of the lucky ones,” adding, “Others had to use more extraordinary means to escape, like my friend Walter Strauss. He tried escaping across the Swiss border with four others. They were caught. He was sent back and was later arrested and killed in Auschwitz.” Ruth left La Hille and led a hidden life in southern France, joining the French Underground. She reportedly had many narrow escapes before fleeing across the Pyrenees into Spain and then Israel, where she helped found a kibbutz and worked as a nurse.

It was at a 1997 reunion of Seyre-La Hille children in France that Reed saw Ruth and his former companions for the first time in 50-plus years. Keen on not being a “captive” of his past, he’d dropped all links to his childhood, including his Jewish identity and name. Other than his wife, no one in his immediate family or among his friends knew his survivor’s tale, not even his three sons.

For Reed, the reunion came soon after he first revealed his “camouflaged” past for the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History project. Then, when his turn came to tell his biography before a Rotary Club audience, he asked himself — “Do I step out of my closet or do I keep hiding from my past?” Opting to “go through with it,” he shared his story and “everything flowed from there.” After attending the ‘97 La Hille reunion, Reed and his wife hosted a gathering for survivors in Chicago and another in France in 2000.

On the whole, the survivors fared well after the war. Two Seyre-La Hille couples married. A pair enjoyed music careers in Europe — one as a teacher and the other as a performer. Nine of the adult camp directors-counselors have been honored for their rescue efforts as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in Israel. Reed has visited many of the sites and principals involved in this conspiracy of hearts. The Chateau La Hill is still a haven, only now instead of harboring refugees as a rustic hideout it shelters tourists as a trendy bed-and-breakfast.

For Reed, taking ownership of his past has brought him full circle.

“Even though our lives have taken many different paths all over the globe, nearly all my surviving companions feel a strong bond with each other. Many have strong ties to the places and persons that gave us refuge during those dangerous and turbulent years of our youth. I think a lot of things happened then that shaped me as a whole. It inculcated in me certain attributes I still have — of taking responsibility and running things.”

Above all, he said, the experience taught him “to resist oppression and discrimination,” something he and his wife do as parents of a child with cerebral palsy. “For me, recrimination and anger are not a suitable response. It’s important we strive for reconciliation and understanding. Then we live the legacy.”

Related articles

- Art Trumps Hate: ‘Brundinar’ Children’s Opera Survives as Defiant Testament from the Holocaust (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- David Kaufmann: A Holocaust Rescuer from Afar (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Holocaust rescue mission undertaken by immigrant Nebraskan comes to light: How David Kaufmann saved hundreds of family members from Nazi Germany

What makes someone a hero? Does it require exposing oneself to physical danger? Or is it taking an action, any action, that no else is willing or able to take in order to save a life or at least remove someone from harm’s way? If you agree, as I do, that doing the right thing, whether there’s the threat of bodily harm attached or not, constitutes heroism, then the late Grand Island, Neb. businessman David Kaufmann qualifies. He repeatedly signed letters of affidavit that allowed family members to leave Nazi Germany for America and freedom. By acting as their sponsor, he not only helped give them new lives here, he essentially saved their lives by getting them away from the clutch of Nazis bent on The Final Solution. When Omaha authors Bill Ramsey and Betty Shrier collaborated on a book about Kaufmann titled Doorway to Freedom I ended up writing several stories about Kaufmann and his actions. Two of those stories follow. These are among some two dozen Holocaust-related articles I’ve written over the years, several of which, including profiles of survivors, can be found on this blog.

Holocaust rescue mission undertaken by immigrant Nebraskan comes to light:

How David Kaufmann saved hundreds of family members from Nazi Germany

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in Nebraska Life Magazine

Grand Island, Neb. Jewish German emigre David Kaufmann is recalled as a Holocaust hero today despite the fact he never fired a shot, never hid anyone, never bribed officials, never forged documents. What he did do was sign letters of affidavit from 1936 to the start of World War II that enabled scores of famly members to escape genocide in Nazi Germany. With strokes of a pen this private citizen did more than some entire states in responding to the Nazis’ systematic eradication of Jews.

As the Holocaust unfolded an ocean away, he extended a lifeline from the middle of America to endangered family in his homeland. His sponsorship booked them safe passage, thus sparing them from near certain death. What makes this rescue effort unlike others from that grim time is that this merchant-entrepeneur managed it all from the small Midwest town he adopted as his own and made his fortune in.

“Yeah, Nebraska’s one of the last places one would think of to find a guy like that,” said retired Omaha Rabbi Myer Kripke, who presided over Kaufmann’s 1969 funeral in Grand Island. After years of ill health, Kaufmann did at age 93, his rescue work little known outside his extended family.

Kaufmann undertook this humanitarian mission at the height of his success as a business-civic leader with retail, banking and movie theater interests. Known as “Mr. Grand Island,” he’s best remembered for Kaufmann’s Variety Store there, the anchor for a south-central Nebraska chain of five-and-dimes.

But he did not act alone. The first family he got out of harm’s way were cousins Isi and Feo Kahn in 1936. With his help the young couple fled Germany for America. They headed straight for Grand Island, where their daughter Dorothy Kahn Resnick was born and raised. Resnick, who lived and worked in Omaha for a time, now resides in Greeley, Col. Her father worked in Kaufmann’s store until opening a used car dealership. Her mother was a “key” confidant of Kaufmann’s in the conspiracy of hearts that evolved. She kept in touch with family abroad and fed Kaufmann new names needing affidavits of support. Feo even brought Kaufmann the forms to sign.

Anti-Semitism made life ever more restrictive for Europe’s Jews, targets of discrimination, violence, imprisonment and death. People were desperate. Official, legal channels for visas dwindled. You needed a sponsor to get out. Dorothy said her mother went back repeatedly to Uncle David, as he’s referred to out of respect, saying, “‘Here’s someone else.’ Some were very distant relations. But she told me he never questioned her. He never wanted to know who they were and how they were related. He relied on her. He trusted her. He put his faith in her that if she said it was OK, he signed it. Uncle David and my mom just did the right thing. Maybe the simplicity of it is what’s so beautiful.”

“While Mr. Kaufmann had the wherewithal to do what he did, God bless him, it never would have happened without Feo,” said family survivor Guinter Kahn. “It was Feo’s doing — her persuasion — that got his agreement to get the others over.”

Kaufmann’s aid even extended after the war to those displaced by the carnage.

No one’s sure of the exact number he rescued. How he delivered people to freedom and therefore a new lease on life is better known. Escaping the Holocaust meant somehow securing the proper paperwork, making the right connections and scraping together enough money. No easy task. Even family living abroad was no assurance of a way out. It was the rare family that had someone who could take on the legal-financial burden of sponsorship. Then there were the shameful restraints imposed by governments, including the U.S., that made obtaining visas difficult. Nationalism, isolationism and anti-Semitism ruled. Apathy, timidity, fear and appeasement closed borders, sealing the fate of millions.

Few stepped forward to offer safe harbor in this crisis. One who dared was Kaufmann. On regular visits and correspondence home this self-made man kept abreast of the worsening conditions and made a standing offer to help family leave. When Isi and Feo took him up on his offer, they became liaisons between him and asylum seekers. Not all chose to leave. Most who didn’t perished.

Kaufmann didn’t need the risk of assuming responsibility for the welfare of distant relations during the Great Depression, when riches were easily lost. Not wanting publicity for his actions, which went against the tide of official and popular sentiment to keep “foreigners” out, he carried on his campaign in near secrecy. Despite all the reasons not to get involved, he did. This unflinching sense of duty makes him a laudable figure, say Omahans Bill Ramsey and Betty Dineen Shrier, authors of a forthcoming book on Kaufmann called Out of Darkness.

In their research the pair found a handful of signed affidavits of the many they determined Kaufmann signed. The affidavits represent perhaps dozens, if not hundreds of lives Kaufmann saved. He apparently left no record of how many he aided nor any explanation of why he did it. His legacy as a rescuer went largely untold outside family circles until a couple years ago. Kaufmann rarely, if ever, spoke of it. There are no press accounts. No mention in books. No journal-diary entries. Other than a letter he wrote a family he helped flee Germany, scant documentation exists.

Related by blood or marriage, the refugees included the Kahns, the Levys and other families. Most settled outside Nebraska. The few that began their new lives in Grand Island or Omaha eventually left to live elsewhere. The only ones to stay in-state were Isi and Feo Kahn, who in later life moved from Grand Island to Omaha, and Marcel and Ilse Kahn, whose two sons were born and raised in Omaha. The two Kahn couples saw more of Uncle David than their relatives and came to know a man who loved to entertain at his comfortable stone home, which sat on well-landscaped grounds. At sit-down dinners and backyard picnics he and his second wife Madeline gave, the couple regaled visitors with tales from their world travels.

Family, for this benevolent patriarch, was everything. Wherever family settled, he kept tabs on them. Upon their arrival in America, each received a $50 check from him. His support was far from perfunctory, just as the affidavits he endorsed were far from idle strokes of the pen. As their sponsor, he was responsible for every man, woman and child listed on the documents and liable for any and all debts they incurred. As the story goes, no one abused his trust.

As if to please him, Kaufmann’s charges distinguished themselves. “We’ve not met or talked to anyone yet that wasn’t very successful. There are doctors, lawyers, researchers. I mean, they were driven by this legacy. He gave them a chance to do something with their dreams and they made the most of it,” Ramsey said.

Underscoring this rich legacy of accomplishment is the fact none of it would have been possible without Kaufmann’s intervention. “The common thread is, If it wasn’t for him. we wouldn’t be here — our lives would have been lost. And they’re eternally grateful. That’s the message that goes through the whole story. They love this man. It just comes through,” Ramsey said.

“You needed someone to sponsor you and it took someone who had the resources, and Kaufmann was a king among kings in Grand Island,” Marcel Kahn said.

Kaufmann leveraged his wealth against his faith the refugees would succeed despite limited education and few job prospects. He vouched for them. If they failed, he was obliged to bail them out. “Keep in mind, it was the 1930s, a time of dust storms and depression,” Kahn said. “And for him to take the initiative that he did to sponsor as many as he did, it was just unreal.”

In February 1938 Marcel Kahn came over at age 6 with his brother Guinter and their parents on the maiden voyage of the New Amsterdam ocean liner. Months later the former Ilse Hessel made the crossing with her parents on the same ship.

The Kahns settled in Omaha. The Hessels in Astoria, New York, where she first recalls meeting The Great Man. “There was such excitement that Uncle David was coming,” she said, adding “if the President himself” came there wouldn’t have been more anticipation. “Whenever he would come we would put on the highest level of adoration you could imagine.” The best china was laid out. A lavish meal prepared. Everyone dressed in their go-to-synagogue finest. While always gracious, Kaufmann carried an “executive” air, Marcel said, that made others defer to him in all things.

On the eve of Uncle David’s 80th birthday, in 1956, Ilse and her aunt Frieda Levy discussed how the family might express their thanks to him.

“We knew we wanted to do something to honor this man because of what he had done for us,” Ilse said. “He gave us our lives. We talked about it for a while and we came up with a Tree of Life. I found an artist who painted it.” The painting included the names of families Kaufmann rescued. Trees were planted in Israel to symbolize the gift of life they’d been given. In return, Kaufmann planted two trees in Israel for every one his family did.

To Grand Islanders, Kaufmann was a businessman-philanthropist. To his family, he was a savior. Few knew he was both.

Before he was a hero, he was a dreamer. In Germany, his rural Orthodox family was in the cattle and meat business in Munsterifel, near Cologne. He left home for the city and found success as a retailer. He came to America in 1903, at age 27, with no prospects and unable to speak English. As an immigrant in New York he mastered the language and entered the retail trade. Then his path crossed with a man who changed his life — S.N. Wolbach. A native New Yorker, Wolbach followed Horatio Alger’s “Go west, young man” advice and found his pot of gold in Grand Island, where he owned a department store and bank. On a 1904 buying trip back east he visited the Abrams and Strauss store in Brooklyn, where the industriousness of a young clerk named David Kaufmann caught his eye. Wolbach convinced him his fortune lay 1,500 miles away working for him at Wolbach and Sons. Flattered, Kaufmann accepted an offer as floorwalker and window trimmer.

No sooner did he get there, than he wanted out. Ramsey and Shrier have come upon letters he exchanged with his brother in Germany in which David bemoans “the lack of pavement, the all-too frequent dust storms and the unimposing buildings.” Shrier said Kaufmann even asked his brother to find him a retail opening back in their homeland. By the time his brother wrote back saying he’d found a position for David, things had changed. “There was something about the old town that made me like it,” Kaufmann reflected years later in print. “There were no big buildings, but that doesn’t make a town. It’s the people who live in a place that make you love it. There was something about those old-timers and the ones who came after me that made me like Grand Island. There was something about the businessmen and the people…their willingness to cooperate in all worthwhile undertakings, that makes it a pleasure to work with them.”

Only a few years after his arrival, he went in business for himself, opening his store in 1906. He was a young man on the move and he’d let nothing stop him. “Some people would make a success at anything. All they need is an opportunity,” Marcel Kahn said. “I’m sure he would have been a success at just about any endeavor.”

Ramsey sees S.N. as “The Great Man model” Kaufmann aspired to. “Kaufmann was a doer and Wolbach was a doer as well,” Ramsey said. “He did a lot of charitable work. He was a well-to-do, respected person. And you get the feeling Kaufmann looked up to this man and figured maybe this is how you become a success.”

There is a perfect symmetry to the story. Just as Wolbach helped Kaufmann realize the classic immigrant-made-good success story and American Dream, Kaufmann helped his family achieve the same. The fact he brought them over at a time of peril makes it all the more poignant.

It may be, as survivor Joseph Khan surmises, “doing this good deed might not have been a big deal” to Kaufmann. “I’m not suggesting or implying it wasn’t. It was. Perhaps he was motivated to bring people over here so they could enjoy the same fruits of their labor as he did. That might have been as much a reason as anything.”

“The man came over with nothing and succeeded and he shared his success with his brothers, his cousins, his neighbors, his friends,” said Erwin Levy, of Palm Desert, Cal., who along with his brother Ernie survived the death camps before coming to America under the auspices of the Jewish aid agency Hais. The brothers were offered help by Kaufmann, though distantly related to him by marriage.

Survivors fully recognize what Kaufmann did was extraordinary.

“Mr. Kaufmann had the money…was in the United States…had the possibilities. Mr. Kaufmann used those possibilities and didn’t hold back at all. For this, he must be given credit. A rare person. An uncommon man. In the early 1930s he saw what was happening” in Germany and “he got us over. He really saved these families, including mine, and there’s no way we can express that thanks,” said Guinter Kahn.

No one asked Uncle David why he did it. For a man of such “humility,” it seemed an imposition. Ilse and Marcel Kahn have many questions today. She asks, “What did he know about the world war and Hitler? What thoughts did he have on the situation in Europe?” Marcel wonders, “Do you suppose he knew more than us?” He also wonders, “What made him do it, realizing there would be a lot of dollars involved if we were to default? And what did we display to make him confident to do such a thing?” He suspects Uncle David knew the family’s attitude of — “Just give us the opportunity” — mirrored his own enterprising spirit. They only needed a chance like the one S.N. gave him. “That’s all we were asking at the time,” he said.

As “he never talked about it,” Dorothy Kahn Resnick said, we’re left to guess. A great-nephew, Mayo Clinic researcher Scott Kaufmann, speculates Uncle David’s actions may have had something to do with “the upbringing” his great-uncle had in Germany. “His parents may have raised him with the idea that this is what you do for family.” He said the patriarchal role Uncle David filled was ironic given he had no children of his own, but the nephew recalls him as “always gracious and happy to see family members,” especially children.

Remarks from an acceptance speech Uncle David made may reveal a clue into what made him reach out to others. “Most of us have more good thoughts than we have bad ones,” he said, “and all we have to do is follow the good thoughts. The handicap is, the good thoughts are often not followed by required action.”

What makes his actions historic is that they may constitute the largest Holocaust rescue operation staged by a lone American. Omahan Ben Nachman has researched the Holocaust for decades and he’s sure what Kaufmann did is unique. He learned of Kaufmann’s deeds as an interviewer for the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Project filmmaker Steven Spielberg launched after Schindler’s List.

“After having learned of the rescue of a family by David Kaufmann I began a search in an attempt to learn if any other American had done anything near what Kaufmann had done,” Nachman said. “In this search I was unable to find anyone who had” brought “as many families out of Germany, to this country…Additionally, I could not find anyone who had brought this many people out and assumed total responsibility for them. All of this done quietly with no publicity for his actions. If only there had been more David Kaufmanns.”

“The story is important, for Kaufmann was one of the ‘silent heroes’ who made it possible for over 100,000 Jews to be saved immediately before and after the Shoah,” said Jonathan Sarna, the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braum professor of American history at Brandeis University. “These heroes provided guarantees, jobs and funds — often for people they had never met, and usually with no thought that they would be reimbursed. We know all too little about these people. Most of the literature concerning America and the Holocaust describes what was not done. Happily, the Kaufmann story reminds us of what was done.”

Survivors were motivated to do well as repayment of the debt owed Uncle David. There’s no doubt of “the gratitude” survivors like Marcel Kahn say they feel for being what his wife Ilse calls “the recipients of his goodness.”

Marcel’s brother, Guinter Kahn, a Florida physician and the inventor of Rogaine, said, “Had he not done what he did, we probably all would have been gassed. It’s incredible. What luck. Talk about hanging from fine threads…Everybody has their saints, and he’s ours.” Guinter said there’s no way to repay such a gift but to make good on it. “I’ve always thought, I’ll do as well as I can, because I’ve been given a chance.” “No one went on the public dole. He never had to support any of the people he sponsored,” said Joseph Kahn of Pennsylvania. Joseph was 8 when he came with his twin brother Hugo, sister Therese, parents and grandfather. The Khans settled in Omaha, where Joseph and Hugo attended school.

“I realize he signed an affidavit of support for me and was responsible for me. But in no way did I want him to be that,” said Fred Levy, who immigrated from Israel, where he and his family fled before the worst of the Holocaust. “I felt an obligation when I came to this country to meet him and thank him in person.” It was Levy’s way of telling him he would carry his own weight.

Ilse Kahn said the family “was too proud” to ever ask for “charity.” This, despite “the tough time” they faced getting along, Marcel Kahn said. “Most of us, fortunately, became successes. Certainly, the second generation really did well in terms of financial success. But without that opportunity, my goodness, we’d be nothing more than a pile of bones or ashes,” he said. “One would assume our successes made him that much happier.”

Success was indeed enough, said Ilse Levy Weiner, an Illinois resident who came with her folks on the S.S. Washington courtesy of Uncle David. “He told my father once that as many as he brought to the United States nobody ever bothered him for one nickel,” she said. “I never forgot that. He was so proud of everybody he brought to this country because they all worked really hard and nobody ever asked him for anything.” “He just wanted them to find their way, get settled and become good citizens,” said Kansas City resident Joe Levy, who was a boy when he, his brother and their parents arrived here. The Levys lived in Omaha for a time.

The kindness Uncle David showed his family was consistent with his giving nature.

“At the center of the book is the generosity and the goodness of this man,” said author Bill Ramsey. Uncle David’s good will extended to caring for a sister struck down by polio, arranging for Grand Island restaurants to feed the homeless on holidays and setting up a Self-Help-Society that supplied hard-on-their-luck folks food and clothing in exchange for work. Long before it was common, he paid sales staff commissions and offered employee sick benefits.

He led drives and made donations to build and improve the community. “He was involved with the Salvation Army, the American Red Cross, St. Francis Hospital…and every board he served on he rose to be the chairman,” Ramsey said. Even in death he keeps giving via the Kaufmann-Cummings Foundation begun by his second wife, Madeline. It awards scholarships to Grand Island area students and recently made a donation to help with the restoration of the Grand Theatre the couple owned.

He led drives and made donations to build and improve the community. “He was involved with the Salvation Army, the American Red Cross, St. Francis Hospital…and every board he served on he rose to be the chairman,” Ramsey said. Even in death he keeps giving via the Kaufmann-Cummings Foundation begun by his second wife, Madeline. It awards scholarships to Grand Island area students and recently made a donation to help with the restoration of the Grand Theatre the couple owned.

For Ramsey, the book project is “a labor of love.” The manuscript has made the rounds with editors and publishers, attracting much interest, but so far no deal has been struck. Ramsey and co-author Betty Shrier are in search of funds to underwrite the cost of printing enough books to provide one in every school and library in Nebraska. Nebraska Educational Television is weighing a possible documentary based on the book.

Family members who owe their lives to Kaufmann appreciate the fact this chapter in history will be preserved. “Because of this book I’ve learned a lot more details about Uncle David and his involvement in the community, civic responsibilities, duties, charitable causes and so on,” Marcel Kahn said, “and just how great of an individual he really was. It’s probably a story that should be told for generations.”

A Man Apart: David Kaufmann’s Little Known Rescue of Hundreds of Jews

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

As the shadow of the coming Holocaust darkened Europe, those sensing the dangers ahead looked for any means of escape. But getting away meant somehow securing the proper paperwork, making the right connections and scraping together enough money. No easy task. Even family living abroad was no assurance of a way out. It was the rare family that had someone who could take on the legal-financial burden of sponsorship. Then there were the shameful restraints imposed by governments, including the U.S., that made obtaining visas and entering another country difficult. Nationalism, isolationism and anti-Semitism ruled the day. Apathy, timidity, fear and appeasement closed borders, sealing the fate of millions.

Few stepped forward to offer safe harbor in the looming humanitarian crisis. One who dared was the late Jewish-German emigre David Kaufmann, a prominent business-civic leader in Grand Island, Neb. When others looked on or averted their eyes, he reached out and offered a lifeline to those facing persecution and peril. Recalled fondly as a philanthropist, he used the wealth and position acquired from his variety stores to spearhead community betterment projects. But he was far more than a good citizen. He was a hero unafraid to act upon his convictions.

David Kaufmann is pictured behind the lunch counter of Kaufmann’s Variety Store in Grand Island with one of his employees and a customer reading the menu. For more information on this photograph or other Hall County history, contact the Curatorial Department of Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer, 3133 W. Highway 34, Grand Island, NE 68801; 385-5316; research@stuhrmuseum.org; orwww.stuhrmuseum.org.

Courtesy photo

From 1936 until America’s engagement in World War II, Kaufmann responded to the growing threat overseas by endorsing affidavits of support for perhaps 250 or more people. The documents provided safe passage here under his patronage and his guarantee the refugees were sound risks. Affidavits were issued individuals, couples, siblings and entire families. His help extended to the post-war years as well, when he sponsored war victims displaced by the hostilities.

Kaufmann’s rescue of oppressed people from near certain imprisonment and probable death went untold outside his own family until last year. He rarely, if ever, publicly spoke of it. There were no press accounts. No mention in books. No radio-television interviews to shed light on it. Other than a letter he wrote a family he helped flee Germany, scant documentation exists, except for the few surviving affidavits of support he signed. More powerfully, there is the testimony of the men and women, now in their 70s, 80s and 90s, who found sanctuary here thanks to Kaufmann’s efforts to remove them from harm’s way.

These survivors came as children or young adults. Those that came during the Nazi reign of terror were fully aware of the terrible fate they avoided through his good graces. Some didn’t make it to the U.S. during the war. They escaped on their own or with the aid of family to havens like Palestine, where Kaufmann sent for them. Those that didn’t get out endured years of physical and emotional torture as prisoners, then more privation in refugee camps, before Kaufmann’s helping hands caught up with them and secured their travel to America.

Once here, the refugees received money and counsel from Kaufmann.

Some ended up in Grand Island and worked at his store. Others settled in Omaha. Most opted for big cities — New York, New Orleans, Chicago, et cetera. Wherever they went, Kaufmann kept tabs on how them. Over time, the family tree grew. Their American ranks must now number in the high hundreds. They own a rich legacy in America, too, where many members have distinguished themselves.

David Kaufmann’s gift of life only grows larger with each new birth and each new generation. Yet his name and good works remain obscure outside the clan and his adopted home. That’s about to change, however. The righteous actions of Kaufmann are the subject of a book-in-progress by Omaha authors William Ramsey and Betty Dineen Shrier that details all he did to ensure his family’s survival in the Shoah. Nebraska Educational Television producers are considering a documentary film on the subject. There is urgency in having the story recorded soon, as with each passing year fewer and fewer of the original Kaufmann wards survive.

Collaborators on two previous books, Ramsey and Shrier were approached with the idea for the Kaufmann book by Ben Nachman, a retired Omaha dentist who’s devoted the past 30 years to Holocaust research. In the course of Nachman serving as an interviewer for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Visual History Project in the early 1990s, he came upon survivors aided by Kaufmann. He knew it was a story that must be shared. Ramsey and Shrier agreed, accepting the assignment. They began work on it last year and have since interviewed dozens of figures touched by Kaufmann.

Collaborators on two previous books, Ramsey and Shrier were approached with the idea for the Kaufmann book by Ben Nachman, a retired Omaha dentist who’s devoted the past 30 years to Holocaust research. In the course of Nachman serving as an interviewer for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Visual History Project in the early 1990s, he came upon survivors aided by Kaufmann. He knew it was a story that must be shared. Ramsey and Shrier agreed, accepting the assignment. They began work on it last year and have since interviewed dozens of figures touched by Kaufmann.

“This sounded like a big story. A national or international story. And I thought it was a story that had gone untold too long. That’s what really drove me,” said Ramsey, a well-known public relations man. “People of all backgrounds are moved by what happened in the Holocaust. And with it being the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II and the liberation of the death camps, the timing was perfect.”

For co-author Shrier, the sheer humanity of it all hooked her. “I think that I have never come across anyone who was so generous across the board to so many different people as David Kaufmann was,” she said. “And he didn’t discriminate with race or creed or philosophy. It made no difference to him. He was good to everybody. And I’ve never met anybody or heard of anybody with that kind of openness. The thing about it is, he was a great businessman. He was stern when it came to business principles, but he still knew how to give.”

Good works defined Kaufmann’s life. The entrepreneur was among a handful of Jewish residents in the south central Nebraska town, yet he assisted all kinds of people in need. His largess extended to everyone from relatives and friends to complete strangers. His contributions to various building committees helped transform Grand Island into a modern city.

Kaufmann kept his most personal good works quiet. Until the Grand Island Independent began reporting last winter on the book project, which has led the authors on repeated research trips there, few residents knew Kaufmann’s name and fewer still his legacy as a Holocaust rescuer. Before he became a hero, he was a man on a mission — hell-bent on improving himself and the lot of his family.

Uncle David, as he’s called in family circles, epitomized the great American success story. He came to this country in 1903 not knowing the language, but through his industriousness he mastered English, he worked his way up the retail trade, first in New York and then in Grand Island, and he soon went into business for himself. Only a few years after arriving here, he’d built a thriving chain of five-and-dimes and put his imprint on all aspects of community life. As Grand Island’s leading citizen, he didn’t need the hassle of vouching and assuming responsibility for the welfare of a sizable number of distant relations. He especially didn’t need the risk to his riches and reputation in the Great Depression, when fortunes and good names were easily lost. Not wanting publicity for his actions, which went against the tide of official and popular sentiment to keep “foreigners” outside the nation’s borders, he carried on his rescue campaign in near secrecy. Despite all the reasons not to get involved, he did. This unflinching sense of duty makes Kaufmann a compelling and laudable figure and is the focus of Ramsey and Shrier’s book.

“At the center of the book is the generosity and the goodness of this man,” said Ramsey. Kaufmann’s good will towards his family, including caring for a sister struck down by polio, was part of a pattern of kindnesses he exhibited in his lifetime. For example, he arranged for Grand Island restaurants to feed the homeless on holidays, reimbursing the eateries himself. He set up a Self-Help-Society that supplied hard-on-their-luck folks food and clothing in exchange for work. He sprung for free sundaes — preparing them himself — when employees did inventory on weekends. Long before it was common, he paid sales staff commissions and offered employee sick benefits. He hosted backyard picnics that fed small armies of friends, neighbors and workers. He led drives and made donations to build and improve the communities he lived in and did business in. “He was called Mr. Grand Island by many. He was involved with the Salvation Army, the American Red Cross, St. Francis Hospital…and every board he served on he rose to be the chairman,” Ramsey said.

Kaufmann died in 1969, but even in death he keeps on giving via the Kaufmann-Cummings Foundation started by his second wife, Madeline.

Then there’s the ripple effect his good works have had. Ramsey, Shrier and Nachman say that almost without exception the people he sponsored, as well as their descendants, have been high achievers, motivated to do well as repayment of the debt owed Uncle David for affording them America’s opportunities.

“We’ve not met or talked to anyone yet that wasn’t very successful. There’s doctors, lawyers, researchers. I mean, they were driven by this legacy. I think they felt their lives were saved, and they probably were. He gave them a chance to do something with their dreams and they made the most of it,” Ramsey said. “I think they were trying hard to please him because he sponsored them and they didn’t want to be a burden on him or on the United States. That was part of each affidavit he signed. It said he was responsible for these people if they don’t make it here. He was putting his name and fortune and everything else on the line.”

The only recompense Kaufmann wanted for his assistance was the assurance his wards were not a drag on society. That alone was reward enough for him said Bourbonnais, Ill. resident Ilse Weiner, who was 17 when she and her parents, Ludwig and Frieda Levy, came on the S.S. Washington courtesy their affidavit of support from Kaufmann. “He told my father once that as many as he brought to the United States nobody ever bothered him for one nickel,” she said. “I never forgot that. He was so proud of everybody he brought to this country because they all worked really hard and nobody ever asked him for anything.”

The gratitude felt by Kaufmann’s charges made them strive to please him. “I realize he signed an affidavit of support for me and was responsible for me. But in no way did I want him to be that,” said Fred Levy, whose affidavit from Kaufmann enabled him to immigrate from Israel, where he and his family fled before the Final Solution.

“I felt an obligation when I came to this country to meet him and thank him in person.” It was Levy’s way of telling him he would carry his own weight.

Even after her family established themselves here, Weiner said, he would visit them on buying trips to Chicago, always bearing gifts and making sure they were getting on OK, offering help with anything they needed. She said once when her father had trouble finding work, Kaufmann put in a good word for him. She said Kaufmann even aided a friend of the family, no blood relation at all, in relocating to America.

Survivors hold Kaufmann in the highest esteem. “They love this man. It just comes through,” Ramsey said. Weiner said, “He was a warm man. Thoughtful. He gave good advice. When we arrived in The States, he sent gifts and a check for $50. He was very generous. He was fantastic to us. He was such a good person. How should I say? We looked up to him like if he was God, because he saved our lives. What more can I say? He saved our lives.” The most famous family survivor, Rogaine inventor and medical doctor Guinter Kahn, has said, “Everybody has their saints, and he’s ours.”

On his 80th birthday, Kaufmann was presented “a family tree” that relatives commissioned an artist to paint. It includes the names of those he rescued and refers to trees planted in Israel to commemorate his life saving legacy.

If Kaufmann was inspired in his good deeds by anyone, it may have been S.N. Wolbach, the figure responsible for bringing him to Grand Island. A native New Yorker, Wolbach went west himself as a young man and found his pot of gold on the prairie, where he opened a department store and held banking interests. On a 1904 buying trip back east he visited the Abrams and Strauss store in Brooklyn, where he was impressed by the salesmanship and work ethic of a young clerk named David Kaufmann. Wolbach convinced Kaufmann his fortune lay 1,500 miles away working for him at Wolbach and Sons. Flattered, Kaufmann accepted an offer as floorwalker and window trimmer. Only nine months after his arrival in America, the enterprising emigre headed west to meet his destiny.

No sooner did he get there, than he wanted out. Authors Ramsey and Shrier have come upon letters Kaufmann exchanged with his brother in Germany in which David bemoans “the lack of pavement, the all-too frequent dust storms and the unimposing buildings.” Shrier said Kaufmann even asked his brother to find him a retail opening back in their homeland. By the time his brother wrote back saying he’d found a position for David, things had changed. “There was something about the old town that made me like it,” Kaufmann reflected years later in print. “There were no big buildings, but that doesn’t make a town. It’s the people who live in a place that make you love it. There was something about those old-timers and the ones who came after me that made me like Grand Island. There was something about the businessmen and the people…their willingness to cooperate in all worthwhile undertakings, that makes it a pleasure to work with them.”

Ramsey speculates Kaufmann’s mentor, Wolbach, “was The Great Man model” he aspired to. “Wolbach was a doer as well. He did a lot of charitable work. He was a well-to-do, respected person. And you get the feeling Kaufmann looked up to this man and figured maybe this is how you become a success,” Ramsey said.

As the Nazis came to power in Germany, Kaufmann was already a self-made man. In his occasional visits and regular correspondence home he kept abreast of the worsening conditions for Jews there and made a standing offer to help family leave. His first affidavit got Isi and Feo Kahn out in 1936. The young couple moved to Grand Island, where their daughter Dorothy Kahn Resnick was born and raised.

Dorothy said her mother was a “key” conduit and emissary in the conspiracy of hearts that evolved, staying in touch with family abroad and feeding Kaufmann new names needing affidavits of support. She even brought him the forms to sign.

As the Nazis clamped down ever more, “people were desperate,” Ramsey said. “They could see what was happening.” Official, legal channels for visas dwindled. Affidavits of support, forged documents or bribes were the only routes out. Dorothy said her mother went back repeatedly to Uncle David with new names, saying, “‘Here’s someone else.’ Some were very distant relations. But she told me he never questioned her. He never wanted to know who they were and how they were related. He relied on her. He trusted her. He put his faith in her that if she said it was OK, he signed it. Uncle David and my mom just did the right thing. They just did it. Maybe the simplicity of it is what’s so beautiful.”

As “he never talked about it,” Dorothy said, we’re left guessing why he acted. Remarks from an acceptance speech he gave may be as close as we’ll ever get to knowing what made him do it. “Most of us have more good thoughts than we have bad ones,” he said, “and all we have to do is follow the good thoughts. The handicap is, the good thoughts are often not followed by required action.” Hundreds lived because Kaufmann heeded his better self to take action.

Related articles

- A Not-so-average Joe Tells His Holocaust Story of Survival (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- New deal on Holocaust-era archive expands access (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Introducing…The World Memory Project (blogs.ancestry.com)

A not-so-average Joe tells his Holocaust story of survival

Another of my Holocaust stories is featured here. Joe Boin tells his story of defiance and survival.

A not-so-average Joe tells his Holocaust story of survival

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Jewish Press

It’s not as if Joe Boin hadn’t spoken about his Holocaust survivor tale before. He shared his story for the Shoah Visual History Project. He’s told it to school groups. He helped form Nebraska Survivors of the Holocaust to raise awareness and to commission public memorials as reminders of what happened.

But until now the Berlin, Germany native never laid out his story for publication. The time seemed right. The 87-year-old widower resides at the Rose Blumkin Home, where he scoots around in his motorized wheelchair with aplomb, American and Go Big Red flags affixed to the back. The amiable man makes friends easily and lives a credo of looking ahead, not back, but the searing memories never dim. Alone with his thoughts, his odyssey is always near.

His wife Lilly, a fellow survivor he met and married after the war, passed away 14 years ago. A Vienna, Austria native, she told her survivor tale in her 1989 book, My Story. Everyone close to her died in the Shoah.

Remarkably, Joe’s entire immediate family made it out alive. His parents are long gone and his only two siblings live in Israel. Palestine is where Joe, Lilly, his sisters and eventually his folks migrated after the war. Joe and Lilly’s two children, Heni Alice and Gustav Daniel, were born and raised in Israel. Joe suffered wounds in the fight for Israel’s independence. The couple’s children preceded them to America and Joe and Lilly followed in 1966.

After hopskotching the country to be near their children, Joe and Lilly made it to Nebraska in the late-1970s, residing first in Lincoln before settling in Omaha.

Today, Joe lives for his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He sees them when he can but they all live out of state. He’s spending Hanukkah and New Year in Phoenix with his daughter and her family.

Joe insists his story is nothing special. “I’m not too interesting,” he says through his thick accent. “I’m not important.” But Joe knows better. He knows that while every survivor story shares certain commonalities, each is its own wonder, even miracle, of fortitude and fate. He knows, too, it’s his obligation to bear witness.

Born Joachim Boin, he was the only son of Arthur and Bianca Boin, an educated Orthodox Jewish couple whose roots were in Germany and Poland, respectively. Joe’s father was a World War I veteran who fought in the German Army. He had his own accounting firm. Joe’s younger sisters, Ruth and Gisela, soon followed.

The family lived in a mixed district of Berlin where Jews and Christians lived and did business together. Next door was a Christian family, the Kruegers, who were old friends. They took an active hand in helping the Boins once the Nazi’s anti-Jewish laws took effect. They even ended up hiding Gisela during the war.

Before the rein of terror, Joe’s early childhood was idyllic. “It didn’t last long but it gave me a taste of what life could be or can be,” he said. “I had dreams but it became impossible for me to even follow them after Hitler came — that all went.”

Growing up in Berlin, Joe witnessed the fascist fervor in its huge rallies and parades that kindled the worst kind of nationalism. The mass public displays included virulent anti-Semetic screeds, all meant to sway the Aryan citizenry, to inflame hatred, to intimidate Jews and other supposed enemies of the state. The Nazi regime tapped the fears of a shaken people by offering security and scapegoats.

“Like everywhere in the world Germany was in a very deep depression, people were out of work and they had big families,” noted Joe, “and so Hitler came and said, ‘Well, if you elect me as your leader I will put bread on your table and I will make sure you have enough money to pay your bills and rent.’ Of course, everybody went for it.”

To the Christian majority Hitler appealed to widespread prejudice in blaming the Jews for Germany’s decline since World War I. For most Jews, the rhetoric and restrictions aimed at them seemed nothing they hadn’t seen or heard before.

“In the very beginning when he was elected he organized the political police and then when people found out what really was going to happen it was too late, they couldn’t do much about it,” said Joe.

A strapping, athletic young man, Joe competed as an elite Maccabi club tennis player, boxer and gymnast, yet Jews like him were ostracized from German national teams and games by the Nazi regime’s racial policies. This exclusion was a bitter pill to swallow for Jewish athletes when Berlin hosted the 1936 Olympics.

“It was pretty painful, I’ll tell you that.”

Amid unprecedented propaganda and pageantry the Nazis attempted to gloss over their campaign of hate against Jews and while some observers saw through the facade most of the world did not. As far back as the Berlin Olympics, Joe’s family was warned of the impending danger facing them.

“In 1936 my mother’s brother, who lived in Berlin, too, came to my dad and said, ‘Arthur, now is the time to leave this country.’ My dad looked at him and said, ‘I was in World War I, I pay my taxes, I have a legitimate business, why should I leave?’ If anybody had any idea what was going to happen, they would have left,” said Joe, but the Boins like most people could not conceive that what seemed another pogrom would become the systematic genocide known as The Final Solution.

Until the fall of 1938 things were tolerable. Jews couldn’t go where and when they pleased as easily as they once could, owing to growing restrictions on their movements and activities, but they didn’t fear for their safety. Clearly, though, life was far from normal and things were getting more tense. Roving gangs of Nazi Brown Shirts were becoming a menace and the mere fact of being a Jew, identified by a Yellow Star, made you a target of these thugs.

The Kruegers, the Christian family who lived next door to the Boins, became a lifeline. “Our neighbors were very nice people and they supplied us with some food and so on, sometimes without taking payment, so that we could live a little,” said Joe.

When he was 15 he and his family moved to a town, Cottbus, where Joe’s father felt they would be more insulated from the Nazi grip. They did find there some kind Christians who lent aid just as the Kruegers had.

“Like everywhere else there were wonderful people that were kind to Jews, that tried to help,” said Joe.

But there ultimately was no escaping the threat. Things took a turn for the worse on Kristallnacht, Nov. 9, 1938. Nazi goons came to the Boin home to take Joe and his father away to the town square where other Jewish residents had been rounded up and their homes and businesses vandalized.

“They took us to a marketplace where they had us surrounded by Nazis and by private citizens and they put dogs on one side and they gave us a spoon and we had to pick up the crap. We got beaten pretty bad. A lot of people got killed there, too. They put bodies in the synagogue and afterwards they burned it.”

For Joe, the nightmarish incident marked the end of his boyhood innocence and the start of a cruel new reality based on instinct, chance and survival.

“My life as a child (ended). I had two years of high school before Hitler kicked us out.” From then on out, life was a harrowing affair. “We were treated like animals, not as human beings, we had to walk on the street, we couldn’t walk on the sidewalks, we couldn’t go into certain stores.”

More and more, Jews found themselves targeted, isolated, marginalized. Then, in 1939, the year Germany invaded Poland and Czechoslovakia and instigated World War II, the family was forcibly split up. A band of Nazis came to the Boin home, this time demanding only Joe come with them. He described what happened:

“At midnight they knocked on our door, shouting, ‘We want your boy Joachim.’ I came to the door and asked, ‘What do you want?’ ‘We have come for you,’ they said, and they grabbed me and hit me and put me on a truck. ‘Where are we going; do I have to take something?’ ‘No, where we’re going you don’t need nothing.’”

The ominous reply presaged the unfolding horror of the next six years, a black time when he and his family were separated from everything they knew, including each other, as each endured his or her own survival odyssey. Joe, his father, his mother and his sister Ruth all ended up in either labor or death camps.

Only his baby sister Gisela was spared. She was hidden by the Kruegers in the Christian family’s Berlin home, where for three-and-a-half years she passed a secreted-away life that if discovered would have meant certain death for her and her benefactors.

“My dad always said to them (the Kruegers), ‘You know, if the authorities find out they’re going to kill you too,’ and they said, ‘We are responsible to God, not to him (Hitler), and we feel if there’s any way to help somebody and to do something that prevents anybody from getting killed, we do it.’”

This courageous attitude struck a chord in Joe, who has tried living up to the kindnesses people bestowed on him and his family.

“It’s amazing in a situation like this that you find people that have a different way of thinking and they feel it’s immoral for others to be killed or whatever just because they’re Jewish. People helped even though they knew if they got caught they would get shot. Despite the risk, they said, ‘No, we have a responsibility to God, but not to Mr. Hitler, and whatever happens, happens,’ and that’s why quite a few Jewish people had a chance to live.”

From the time Joe was taken away in the middle of the night to the war’s end, six years passed before he was reunited with his family. He would survive six camps in four countries, counting the displaced persons and refugee camps he ended up in after the war, before the ordeal was over.

“The first camp I was in was Sachsenhausen — it was a concentration camp close to Berlin where all kinds of political prisoners, religious people were together, gypsies too. Just a very, very interesting group of people, and then from there they distributed them to the other camps.”

He didn’t know anyone at Sachsenhausen.

“I didn’t want to know anybody because in a situation like this it’s very difficult to trust people you don’t know. Sometimes you had to, but unfortunately you had a lot of Jewish people who tried to inform the Nazis of what was going on, hoping they might have a better life, which didn’t happen.”

Upon his arrival, Joe was consumed with anger over the injustice of it all.

“I was 17-years-old and the only crime I’d committed was I was born to a Jewish mother. That’s why I could never understand why I had to go through all this. I wasn’t thinking about anything else but why I’m here. I didn’t steal anything, I didn’t murder anyone — why am I here, what’s the reason? Why couldn’t I get my education so I could become somebody and get further on in life later? Why? — because I was Jewish. I could not get over that.”

Then some things happened those first 24 hours in camp to change his outlook.

“I was so mad that when we came in the barracks in the evening I said, ‘I think if I ever by any chance come out of this place I will kill every German that comes in my way.’ Somebody tapped me on my shoulder and said, ‘No my son, if you do this you’re not any better than the Nazis.’” It started him thinking.

“The next morning we had to stand in a roll call and an elderly man fell down and, of course, I bent down trying to help him and one soldier came and shoved this rifle in my back and so I fell down, too. We were carried into the barracks and the older prisoners told me, ‘If you want to stay alive you don’t see anything around you.’ Well I was a person that wanted to see what life was all about and I was trying to live a little longer if I could, and so I followed this advice.”

Joe was also befriended by an elderly Catholic priest whose selfless example made a big impact on him. When the meager bread ration was given out, Joe said, the old priest gave away his portion to Joe and other young people. “He told us, ‘You need it more than I do, I have nothing to look forward to, it’s God’s will.’ It taught me there are people who really care for other people.”

After two years at Sachsenhausen Joe was transported to Buchenwald in 1941.

“Buchenwald was horrible for me because I was delegated to be on the railroad platform as trains came in from Holland and Belgium. I would pick up the suitcases and possessions people carried. The hardest thing for me was seeing women come with little children in their arms and the children, some not even a year old, were taken away and thrown on the platform. Some guards did much more worse — they used them as target practice. I still have nightmares about this.”

It took all of Joe’s self-discipline to not respond, not intervene, not retaliate.

“I was strong enough I could probably have killed some guards but that wouldn’t do me any good because two minutes later people would be shot on the spot. It doesn’t help me or nobody else either. It was a hard decision to make but unfortunately that’s the way it worked.”

Living conditions were abysmal in every concentration camp, but he said the treatment by the Buchenwald guards was particularly harsh.

“The guys that watched us were much more brutal in Buchenwald than they were in Sachsenhausen. They got a bottle of whiskey in the morning to drink to get them in the mood of tormenting us. They were specially trained, they had only one thing in mind, make sure the people don’t get out of here alive.”

As part of the Nazi program of humiliating prisoners, he said, inmates were given absurd tasks meant to break their mind and spirit.

“We had to do idiotic things, like they had a room that needed to be cleaned and they give us a toothbrush to clean the walls. It made you feel degraded. This is the evil of the world — to not treat us like human beings. They didn’t want you to feel as a human being anymore — well, they didn’t have any luck with me.”

Death, hunger, toil and beatings became every day occurrences.

“In our barracks we had bunk beds, with maybe four or five people laying there in a clump, and very often when you woke up in the morning somebody was dead. It took me a long time to get over those deaths,” he said.

Hardening himself to his reality became a necessary thing.

“I always thought a little bit different — that I’m in a situation where I have to do certain things and I’m looking for a loophole maybe somewhere to improve my situation. Sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t. I was able to be pretty open with the people that were surrounding me in trying to explain how important it was for our little group here to hold together and not go to the Nazis, that we had to stick together and try to improve our lives — that was the only way to make it happen. Some of them did and some of them didn’t.

“Some didn’t have the will (to live) anymore. One guy told me, ‘What difference does it make?’ Some people had a little bit of sense left. I had the will to live. I prayed to God, ‘I know if you want you will give me the strength to fight back in a way to keep my mouth shut when I should,’ instead of saying something that would give them the opportunity to beat me or to restrict food from me.”

That resolve and restraint, he said, “was not very easy because when you work hard 10-12 hours a day with nothing to eat your mind is mush. I tried to get rest as much as I could because I knew that’s what I needed. Somehow I still kept on going.”

He kept alert for work details that might provide a scrap more food or be out of harm’s way. “If somebody was really weak I jumped in and told them, ‘I’ll do it.’” That may have saved his life when he got to Auschwitz-Birkenau in late ’44.

“I ended up in Auschwitz,” whose dark reputation, he said, preceded it — “somehow it went from camp to camp what happened there. I knew if I would stay there that would be it. My strength was down, we were beaten every day, we had no good food, we had to work. I wasn’t Superman, I just was a simple human being who can take only so much. I was lucky to get out of there.”

It just so happened a work detail was formed and Joe was in the right place at the right time to be assigned it. “I was there three weeks and then some officer came and he saw me and put me to work in the stone quarries on the Polish-German border, near Hindenburg. There was a big forest around us. We slept in tents.”

In early 1945 the quarry camp came under bombardment from advancing Russian forces and Joe and some fellow prisoners used the cover of chaos to flee.

“There were about 10 of us and we said, ‘Let’s go, no matter what.’ We escaped in the big forest there. Some of us were pretty weak. We were afraid the guards might set their dogs on us, so we tried to put as much distance between us and them, but most of the guards had fled — they didn’t want to get in the Russians’ hands.”

After foraging on the road for six or seven days Joe and his mates were liberated by Russian Army troops. “We were lucky,” he said, “there was a Jewish major in their ranks who spoke Yiddish and he warned us not to eat the uncooked bacon the Russians spread out to feed us. He said after what we’d been through it would kill us.”

The major didn’t warn about the bottled drinks the Russians offered.

“It looked like water to me, I was so thirsty, so I drank and I almost died — it was 100 percent vodka,” said Joe, who can smile about it now.

Joe weighed 82 pounds when rescued. He spent two months in a Russian military hospital. Once he regained his strength, he made his way to Holland, mostly by hitching rides with G.I. transports. His family had agreed to meet there if they were ever separated during the war. His mother’s brother had fled there. He hoped his family had survived but he had no real expectation of seeing them again.

Amazingly, he said, “we all came out of it. We were lucky. Slowly but surely everybody made their way to Holland.” His mother had survived as a laundress for the German military, his father escaped a camp before being pressed into duty making military roads, Ruth worked in a labor munitions camp and Gisela remained hidden.

The Boins spent the next year in a D.P. camp, where Joe met the woman who became his wife, the former Lilly Engelmann Margulies. She was a survivor of Theresienstadt (Terezin). Having lost her husband, parents and siblings, Lilly was all alone and the Boins became her protectors and friends. There was a considerable age difference between Joe and Lilly but the attraction was mutual.

“We liked each other. Then, of course, I asked her one day ‘will you marry me?’ and she looked at me and said, ‘no,’ and I didn’t take no for an answer, I wanted an explanation. So she told me, ‘Well, I’m 14 years older than you,’ and I said, ‘So what?’ So we got married in Amsterdam and we were married 50 years.”

With no prospects or permits for starting a new life in war-ravaged Europe, the couple, along with Ruth and Gisela, embarked on an epic journey to reach the promised land of Palestine. Traveling with no visas, they made their way to France and Belgium.