Archive

Harvesting food and friends at Florence Mill Farmers Market, where agriculture, history and art meet

Harvesting food and friends at Florence Mill Farmers Market, where agriculture, history and art meet

©by Leo Adam Biga, Originally published in the Summer 2018 issue of Food & Spirits Magazine (http://fsmomaha.com)

The Mill Lady is hard to miss at the Florence Mill Farmers Market on summer Sundays. She’s the beaming, bespectacled woman wearing the straw hat adorned by sprays of plastic fruit and vegetables.

Market vendors include local farmers, urban ag growers, gardeners and food truck purveyors. It’s been going strong since 2009 thanks to Linda Meigs, aka The Mill Lady. As director of the historic mill, located at 9102 North 30th Street, she’s transformed a derelict site into a National Register of Historic Places cultural attraction “connecting agriculture, history and art.”

She “wears” many hats beyond the fun one. As market manager, she books vendors. She organizes exhibits at the Art Loft Gallery on the mill’s top floor. She curates the history museum on the main level. She schedules and hosts special events. She writes grants to fund operations. Supervising the mid-19th century structure’s maintenance and repairs is a job in itself.

Ever since she and her late husband John acquired the abandoned mill in 1997. Meigs has been its face and heart. An artist by nature and trade, she also has an abiding appreciation for history.

“Omaha would be such a beautiful city with some of the architecture we’ve torn down. This is not the most beautiful architecture in Omaha, but it is the oldest historic business site and the only still-standing building in the state that bridges the historic eras of the overland pioneer trails of the 1840s with the territorial settlement of the 1850s. That’s a very small niche – but what a cool one. And it has this Mormon heritage and connection to Brigham Young, who supervised its construction.”

It took her awhile to arrive at the ag-history-art combo she now brands it with.

“I had very vague, artsy ideas about what to do. But that first summer (1998) I was in here just cleaning, which was the first thing that needed to be done, and I had a thousand visitors and the building wasn’t even open. A thousand people found their way here and they were all coming to see those 1846 Mormon hand-hewed timbers

“It was like those timbers told me it needed to be open as an historic site after that experience.. This is my 20th summer with the mill.”

She made the guts of the mill into the Winter Quarters Mill Museum with intact original equipment and period tools on view. Interpretive displays present in words and images the site’s history, including the western-bound pioneers who built it. She converted the top floor into the ArtLoft Gallery that shows work by local-regional artists. Then she added the farmers market.

“It was not really until after it happened I realized what I had. Then I could stand back and appreciate the integrity of it. I felt like it was a natural fit for that building because it was an ag industrial site and an historic site. The pioneer trails is certainly a significant historical passage of our country.

“Then, too, I’m an artist and a foodie. I think supporting local is good for both personal health and for conservation of resources. It promotes individual health and the health of the local farm economy. It has less impact on the environment with trucking when you bring things in from close by as opposed to far away.

“I’m into fresh, locally-produced food. In the summer I pretty much live on local vegetables. I am a gardener myself and i do support my farmers market folks, too.”

Farmers markets are ubiquitous today in the metro. Hers owns the distinction of being the farthest north within the city limits. It proved popular from the jump.

“That first farmers market started with six vendors. Hundreds of people showed. It was a crush of people for those vendors. And then every week that summer the number of vendors increased. I think we ended up with about 40 vendors. I was pleased.

“Really, 30 is about the perfect number. It’s the most manageable with the space I have. I’m not trying to compete with the maddening crowd market.”

Finding the right mix is a challenge.

“You want to have enough variety to choose from, but you also have to have the customers that will support those vendors or they wont come back. If the community doesn’t support it, it’s hard to keep it going.”

Other markets may have more vendors, but few can match her setting.

“This one is quite unique. It’s in a field. It’s inside and outside an historic ag building. And it feels like an authentic place for a market.”

She cultivates an intimate, upbeat atmosphere.

“It’s like a country fair. I have live music. Dale Thornton’s always there with his country soft pop ballads in the morning. The afternoon varies from a group called Ring of Flutes to old-time country bluegrass circle jams. Second Sundays is kind of a surprise. One time I had harpists show up. Lutist Kenneth Be has played here several times. I’ve had dueling banjos. Just whatever.”

A massage therapist is usually there plying her healing art. Livestock handlers variously bring in lamas, ponies and chickens for petting-feeding.

A main attraction for many vendors is Meigs.

“Oh, she’s beautiful. Nice lady, yeah,” said Lawrence Gatewood, who has the market cornered with barbecue with his T.L.C. Down Home Food stall.

Jared Uecker, owner of O’tille Pork and Pantry, said, “Linda’s exceptional to work with and really cares about the market and its vendors. She’s passionate about local food and is a frequent customer of ours.”

Jim and Sylvia Thomas of Thomas Farms in Decatur, Nebraska are among the produce vendors who’ve been there from near the start and they’re not going anywhere as long as Meigs is around.

“Everybody loves Linda. She’s what makes it,” Jim Thomas said. “She’s really doing a good job and she’s pretty much doing it for free. I mean, we pay her a little stall fee but for what we get its a deal.”

“Jim and Sylvia Thomas came in the middle of that first season and they’ve come back every year,” Meigs said.

“We kind of grew along with it,” Thomas said. “It’s a really nice friendly little market. We’re also down at the Haymarket in Lincoln, but it’s touristy, This (Florence Mill) is more of a real, live food market.”

Thomas is the third-generation operator of his family farm but now that he and his wife are nearing retirement they’re backing off full-scale farming “to do more of this.” “I like the interchange with the people. I guess you’d say its our social because out in the boondocks you never see anybody. The thing about Florence is that you get everybody. It’s really varied.”

That variation extends to fellow vendors, including Mai Thao and her husband. The immigrants from Thailand grow exquisite vegetables and herbs

“They came towards end of the first season and they’ve always been there since,” Meigs said.

Then there’s Gatewood’s “down home” Mississippi-style barbecue. He learned to cook from his mother. He makes his own sausage and head-cheese. He grows and cooks some mean collard greens.

Gatewood said, “I make my own everything.”

“I call him “Sir Lawrence,” Meigs said. “He’s come for the last three years. He smokes his meats and beans right there. He grills corn on the cob.”

Gatewood gets his grill and smoker going early in the morning. By lunchtime, the sweet, smokey aroma is hard for public patrons and fellow vendors to resist.

“He’s a real character and he puts out a real good product,” said Thomas.

Kesa Kenny, chef-owner of Finicky Frank’s Cafe, “does tailgate food at the market,” said Meigs. “She goes around and buys vegetables from the vendors and then makes things right on the spot. She makes her own salsa and guacamole and things. You never know what she’s going to make or bring. She’s very creative.”

Kenny’s sampler market dishes have also included a fresh radish salad, a roasted vegetable stock topped, pho-style, with chopped fresh vegetables, and a creamy butter bean spread. She said she wants people “to see how simple it is” to create scrumptious, nutritious dishes from familiar, fresh ingredients on hand.

“From a farmers market you could eat all summer long for pennies,” Kenny said.

More than a vendor, Kenny’s a buyer.

“She’s very supportive,” Meigs said. “For years, she’s bought her vegetables for her restaurant from the market.”

“It’s so wonderful to have that available,” Kenny said.

Meigs said that Kenny embodies the market’s sense of community.

“She comes down to the market and does this cooking without advertising her own restaurant. I told her, ‘You need to tell people you’re Kesa of Finicky Franks,’ and she said, ‘No, I’m not doing this to advertise my restaurant, I’m doing this to support the market and to be part of the fun.’ That’s a pretty unique attitude.”

“Kesa’s also an artist. She I knew each other back at the Artists Cooperative Gallery in the Old Market. She quit to open a cafe-coffee shop and I quit to do an art project and then got the mill instead. It’s funny that we have reconnected in Florence.”

Jim Thomas likes that the market coincides with exhibits at the ArtLoft Gallery, which he said provides exposure to the art scene he and his wife otherwise don’t get.

“I really enjoy the artsy people and the crafts people. They’re so creative. I guess what I’m saying is for us it isn’t about the food as much as it is about the people.”

Being part of a site with such a rich past as a jumping off point to the West is neat, too.

“That’s some big history,” said Thomas.

He added that the variety and camaraderie keep them coming back. “It’s really diverse and we’ve developed a lot of friendships down there.”

“It’s a great mingling of different nationalities and cultures.” Sylvia Thomas confirmed. “All the vendors help each other out, which is very unique. At a lot of markets, they don’t do that. Here, if you don’t have something that someone’s looking for, we’ll refer you to who has it. After you’ve been there long enough like we have, vendors and customers become kind of a family. Our regular customers introduce us to their kids and grandkids and keep us posted on what’s going on, and they ask how our family’s doing.

“We kind of intertwine each other.”

The couple traditionally occupy the market’s northeast corner, where gregarious Jim Thomas holds court.

“Linda (Meigs) tells us, ‘You’re our welcoming committee.’ It’s very fun, we enjoy it a lot,” Sylvia Thomas said.

Lawrence Gatewood echoes the family-community vibe found there.

“It’s real nice there. Wonderful people.”

Even though business isn’t always brisk, Gatewood’s found a sweet spot on the market’s southeast side.

“Not every Sunday’s good, but I still like being out there mingling with the people.”

But food, not frivolity, is what most patrons are after.

“Our big deal in the summer is peppers and tomatoes,” Jim Thomas said. “We also have onions,p ottos, cucumbers, eggplants. We do sweet corn but sweet corn is really secondary. Early this year, if we get lucky, we might have some morels down there. Morels sell like crazy. We can sell just as many as we’ve got.”

In the fall, Thomas pumpkins rule.

The veggies and herbs that Mai Thao features at her family stall pop with color. There are variously green beans, peas, bok choy, radishes, fingerling potatoes, cucumbers, kale, cilantro and basil.

Makers of pies, cakes and other sweets are also frequent vendors at the market.

The farmers market is not the only way the mill intersects with food. Meigs has found a kindred spirit in No More Empty Pots (NMEP) head Nancy Williams, whose nonprofit’s Food Hub is mere blocks away.

“We both have an interest in food and health,” Meigs said as it relates to creating sustainable food system solutions. “Nancy is also into cultivating entrepreneurs and I guess I am too in a way.”

Jared Uecker found the market “a wonderful starting point” for his start-up O’tillie Pork & Pantry last year.

“It was the perfect home for us to begin selling our meat products. I really enjoyed its small-size, especially for businesses new to the market such as ourselves. It gave us a great opportunity to have a consistent spot to showcase our products and bring in revenue for the business. I particularly enjoyed the small-town family feel to it. It’s filled with really great local people using it for their weekly shopping as opposed to some other bigger markets which can feel more like people are there more to browse.”

The mill and NMEP have organized Blues and Barbecue Harvest Party joint fundraisers at the mill.

Meigs has welcomed other events involving food there.

“I’ve hosted a lot of different things. Every year is kind of different. In 2014 the mill was the setting for a Great Plains Theatre Conference PlayFest performance of Wood Music. The piece immersed the audience in reenactments of the mill’s early history, complete with actors in costume and atmospheric lighting. A traditional hoedown, complete with good eats and live bluegrass music, followed the play.

Kesa Kenny catered a lunch there featuring Darrell Draper in-character as Teddy Roosevelt. A group held an herb festival at the mill. Another year, crates of Colorado peaches starred.

“I occasionally do flour sack lunches for bus tour groups that come,” Meigs said. “I make flour sacks and stuff them with grain sampler sandwiches that I have made to my specifications by one of the local restaurants. It’s like an old-fashioned picnic lunch we have on the hay bales in the Faribanks Scale.”

The mill is part of the North Omaha Hills Pottery Tour the first full weekend of October each year. The Czech Notre Dame sisters hold a homemade kolache sale there that weekend.

Visit http://www.theflorencemill.org.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at https://leoadambiga.com.

To vote or not to vote

To vote or not to vote

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Get out the vote (GOTV) efforts, whether partisan party-driven or community-based, are a staple of American politics. In this messy mosaic of interests, attitudes and demographics, you may regard voting as solemn civic duty or why-bother-it’s-rigged hassle.

Whether viewed as endorsement, protest, act of hope or futile gesture, your vote is coveted, if not always counted, as with some provisional ballots following a change of residence. With a prior felony, exercising the right to vote may be denied. Never assume anything though because regulations vary by county or state.

Omaha and Nebraska are no different than the rest of the nation’s red-blue map when it comes to voting trends and takes.

Douglas County Chief Deputy Election Commissioner Chris Carithers counters cynicism and apathy by referencing various local races decided by a few dozen votes.

“Every vote does matter,” he preaches. “It’s just convincing people of the power their votes can have.”

Issues make elections and candidates are the lightning rods that inspire or disturb the body politic. Primaries don’t entice the way general elections do, but it all comes down to who’s running for what offices. In the run-up to Nebraska’s May 15 mid-term primary, voter registration and education efforts have been in full-swing in areas of historically low voter turnout, such as predominantly black Ward 2 in North Omaha.

Politicos know 72nd Street is a boundary-line marker for voter turnout. On average, in general elections, about 75 percent of eligible West Omaha voters cast ballots compared to 45 percent in east Omaha. In Ward 2, the turnout reached 62 percent for the 2008 general election when Barack Obama won the White House. In the 2016 presidential election, that number dipped to 47 percent. Mid-term and municipal elections draw in the 30s and 20s. Given that, Carithers said, it’s only logical “who’s going to get attention” from elected officials, and thus, he emphasizes, it is in inner city voters best interests to have their say rather than stay away come election day.

Getting more urban core voter participation is a challenge. One reason is higher mobility rates, said Carithers. The more people change rental addresses, the harder it is reaching them with registration drives and with election date and polling place reminders.

Individuals without transportation or residing in shelters, half-way houses and nursing homes are tough to reach. Some may have been die-hard voters, but once out of the mainstream, it’s difficult recapturing them.

Many efforts target lapsed and new voters.

Omaha Black Votes Matter guru Preston Love Jr. was in his milieu evangelizing about the need to vote at the inaugural North Omaha Political Convention on April 14. The event drew some two hundred folks for candidate meet-and-greets, panel discussions on issues affecting North O and registration-voting information shares.

He liked what he saw.

“North Omaha in modern times has never had such a grassroots effort to get our people activated,” he said.

Omaha NAACP president Vickie Young said the convention represented a coalition of community partners working together for a common cause.

“We all have the same goal. We want people to register. We want them to get to the polls. We want them to be educated on the issues and candidates. It was a great effort with great participation,” she said.

The event was organized by Voter Registration Education and Mobilization (VREM) – a collaborative of community, civic and social service organizations.”We’re trying to motivate attendees to go out and get people on their block to vote,” Love said. “We’re hoping the results of this will be record voting for a mid-term election.”

Love, a former national political campaign manager. vowed, “It will be built on. We have captured attention. We want to corral this energy. We’ve got to start getting our people involved. It is critical.”

He envisions Black lobbying efforts aimed at the state legislature growing out of the event.

Spurring participation, he said, is a desire to unseat the conservative Republican stranglehold.

“What I’m finding in the community is a renewed awareness of the need to vote. People are very dissatisfied in my community and so that’s activating people to get involved.”

Love hopes to mobilize more door-to-door GOTV campaigns. He welcomes smaller, informal efforts, too.

“If you can get your neighbor or someone in your family turned on to participating, they have ripples because they talk about the issues or the candidates and they may be really proactive in getting folks to register.”

That strategy is behind some Heartland Workers Center (HWC) voter engagement efforts in South Omaha.

Young is counting on the ripple effect from the NAACP’s April 21 candidate forum to carryover on election day.

Frontline voter advocates are generally satisfied that the need to vote is being messaged and received.

“We can educate as much as we want, but we have to give people a reason to want to get out to vote,” Young said. “We have to make today’s issues that much more relevant. That’s what our branch is trying to do with initiatives such as the forum – to bring candidates in on a more intimate level to let residents ask them the questions they really want to ask and to get those answers. We can be that much more intentional with our questioning in regard to how candidates will handle racism, discrimination, education and increase diversity. We can then hold them accountable to those issues that affect people of color.”

North and South Omaha contain marginalized populations with low voter participation. In 2017, HWC partnered with Black Votes Matter on a Ward 2 canvassing campaign for the municipal election. Despite knocking on doors and making calls, voter turnout slightly decreased, said HWC senior organizer Lucia Pedroza-Estrada, although a similar campaign in South Omaha helped increase turnout there.

Many things contribute to low voter turnout.

“Poverty has a dynamic effect on community engagement because people are trying to survive on a daily basis and things like this go to the bottom of the list,” said Love, who feels “there’s not enough information given to the rank and file.”

Perhaps the toughest barrier to overcome, he said, is that “people don’t see the difference and feel the difference even though there are in many cases testimonies of what difference is being made.” “If you ask many people how their lives are different, they tell you, ‘I was poor and trying to make it before Obama, and I’m in the same place.'”

The disenfranchised are potentially at greater risk of voter suppression, but it appears Omaha’s been spared such tampering.

“I can’t think of any instances where anyone has done anything to intimidate voters,” Carithers said. “We were proactive in anticipating there could be some people challenging voters in the 2016 election and there were absolutely no issues.”

Omaha attorney Patty Zieg, a National Democratic Committee member and veteran poll watcher, said, “I haven’t seen intentional, official suppression. I also don’t remember any organized phone calls giving people the wrong election date like it happened in other states.”

Polling place consolidation implemented by former Douglas County Election Commissioner Dave Phipps in 2012 created an uproar in North Omaha.

“There was a perception we were trying to take these polling places away,” Carithers said.

Phipps was later replaced by Brian Kruse.

“Brian and I have gone out in the community to assure people we’re there to help them, not hurt them,” Carithers said. “We’ve made a concerted effort to make sure we’re in all the communities and giving information we think will be valuable to neighborhood groups. I think we do have a better relationship now than we did six years ago.”

“Chris and Brian have worked very hard at that. They’re very conscious of it,” Zieg said.

The nonpartisan commission intersects with many GOTV actors and advocates, including fraternities, sororities, church groups, the Empowerment Network, the Urban League of Nebraska, the NAACP and Black Votes Matter.

“We have a monthly meeting of what we call the GOTV stakeholders comprised of various groups interested in getting the vote out, ” Carithers said. “They run the political spectrum from right to left. We work with them to coordinate around what we can do to increase voter turnout so that people will participate.”

The League of Women Voters and Nebraska Appleseed are more players in this arena. Black Men United, Omaha City Councilman Ben Gray and the Empowerment Network host community forums.

“I think we each have a role,” Young said.

The Urban League’s Black and Brown Legislative Day schools participants on the legislative process as well as pressing issues and provides opportunities to meet elected officials. In partnership with Civic Nebraska, it holds Know Your Voting Rights trainings. Its Advocacy Task Force and Young Professionals auxiliary group work to reinstate voting rights for people with felony convictions, ensuring voter ID legislation is not passed, advocating for automatic voting registration and streamlining the registration and updating processes.

Bid to advance mandatory voter ID have failed in the Nebraska Unicameral. Carithers said his office sees no reason for special voter IDs since election fraud is a non-issue. It could also prove cost-prohibitive in this tight budget climate. Same-day registration and updating could create long lines and delays.

The Commission has switched voter verification (purge) programs after accuracy problems surfaced with the previous provider – CrossCheck.

Love is convinced education is the key to greater engagement. He’s organizing a summer “Walking in Black History” tour as a civics-history learning and leadership development opportunity for urban youth. Forty high school students from North Omaha will travel to 19 historic civil rights sites in Memphis, Birmingham, Montgomery, Tuskegee, Selma and Atlanta.

“I never saw a need to do a tour until I realized we’re taking some things for granted about the kids’ knowledge. The purpose is to try to plant seeds. My goal is they’ll come back wanting to participate in things like voting.”

He’s encouraged by a new, young crop of black leaders who’ve emerged as civic engagers and even candidates: Maurice Jones, Ean Mikale, Mike Hughes, Spencer Danner, Mina Davis, Tyler Davis. They are following the momentum of Black Lives Matter and other movements seeking change.

“There’s a lot of young people popping up. They’re all part of the future.”

Pedroza-Estrada is also buoyed by the dynamic young Latino leaders-engagers emerging in South Omaha. The immigration war is a catalyst for many.

Both she and Love want to help grow more social-civic-political volunteers and activists. It starts early.

“If we don’t show them the way or give them a reason why its important,” Love said, “then they wont vote and they wont become engaged in this process.”

Regardless of age, Vickie Young said, “We want to encourage more African-Americans to become involved in the political process, to run for office and get policies and bills passed that improve people’s lives.”

Love has found there’s no substitute for being “on the ground” rubbing shoulders with the constituency he seeks to energize. It’s why his office is on 24th and Lake and why he sends out door-to-door canvassers who mirror residents in that community.

The good fight is ongoing.

“It’s a full-time, year-round effort,” he said. “You have to build credibility – very important. You have to be a convener. You have to show you’ve invested in the community and what you’re telling people is right.”

Visit votedouglascounty.com or call 402-444-VOTE (8683).Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

North Omaha rupture at center of PlayFest drama

North Omaha rupture at center of PlayFest drama

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the May 2018 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In her original one-act More Than Neighbors, playwright Denise Chapman examines a four-decades old rupture to Omaha’s African-American community still felt today.

North Freeway construction gouged Omaha’s Near North Side in the 1970s-1980s. Residents got displaced,homes and businesses razed, tight-knit neighborhoods separated. The concrete swath further depopulated and drained the life of a district already reeling from riots and the loss of meatpacking-railroading jobs. The disruptive freeway has remained both a tangible and figurative barrier to community continuity ever since.

Chapman’s socially-tinged piece about the changed nature of community makes its world premiere Thursday, May 31 at 7:30 p.m. as part of the Great Plains Theatre Conference’s PlayFest.

The site of the performance, The Venue at The Highlander, 2112 North 30th Street, carries symbolic weight. The organization behind the purpose-built Highlander Village is 75 North. The nonprofit is named for U.S. Highway 75, whose North Freeway portion severed the area. The nonprofit’s mixed-use development overlooks it and is meant to restore the sense of community lost when the freeway went in.

The North Freeway and other Urban Renewal projects forced upon American inner cities only further isolated already marginalized communities.

“Historically, in city after city, you see the trend of civil unrest, red lining, white flight, ghettoizing of areas and freeway projects cutting right through the heart of these communities,” Chapman said.

Such transportation projects, she said, rammed through “disenfranchised neighborhoods lacking the political power and dollars” to halt or reroute roads in the face of federal-state power land grabs that effectively said, “We’re just going to move you out of the way.”

By designating the target areas “blighted” and promoting public good and economic development, eminent domain was used to clear the way.

“You had to get out,” said Chapman, adding, “I talked to some people who weren’t given adequate time to pack all their belongings. They had to leave behind a lot of things.” In at least one case, she was told an excavation crew ripped out an interior staircase of a home still occupied to force removal-compliance.

With each succeeding hit taken by North O, things were never the same again

“There was a shift of how we understand community as each of those things happened,” she said. “With the North Freeway, there was a physical separation. What happens when someone literally tears down your house and puts a freeway in the middle of a neighborhood and people who once had a physical connection no longer do? What does that do to the definition of community? It feels like it tears it apart.

“That’s really what the play explores.”

Dramatizing this where it all went down only adds to the intense feelings around it.

“As I learned about what 75 North was doing at the Highlander it just made perfect sense to do the play there. To share a story in a place working to revitalize and redefine community is really special. It’s the only way this work really works.”

Neighbors features an Omaha cast of veterans and newcomers directed by Chicagoan Carla Stillwell.

The African-American diaspora drama resonates with Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun and August Wilson’s Jitney with its themes of family and community assailed by outside forces but resiliently holding on.

Three generations of family are at the heart of Chapman’s play, whose characters’ experiences are informed by stories she heard from individuals personally impacted by the freeway’s violent imposition.

Faithful Miss Essie keeps family and community together with love and food. Her bitter middle-class daughter Thelma, who left The Hood, now opposes her own daughter Alexandra, who’s eager to assert her blackness, moving there. David, raised by Essie as “claimed family,” and his buddy Teddy are conflicted about toiling on the freeway. David’s aspirational wife, Mae, is expecting.

Through it all – love, loss, hope, opportunity, despair, dislocation and reunion – family and home endure.

“I think it really goes back to black people in America coming out of slavery, which should have destroyed them, but it didn’t,” Chapman said. “Through our taking care of each other and understanding of community and coming together we continue to survive. We just keep on living. There are ups and downs in our community but at the end of the day we keep redefining communityhopefully in positive ways.”

“What makes Denise’s story so warm and beautiful is that it does end with hope,” director Carla Stillwell said.

Past and present commingle in the nonlinear narrative.

“One of the brilliant things about her piece is that memory works in the play in the way it works in life by triggering emotions. To get the audience to experience those feelings with the characters is my goal.”

Feelings run deep at PlayFest’s Neighborhood Tapestries series, which alternates productions about North and South Omaha.

“The response from the audience is unlike any response you see at just kind of a standard theater production,” GPTC producing artistic director Kevin Lawler said, “because people are seeing their lives or their community’s lives up on stage. It’s very powerful and I don’t expect anything different this time.”

Neighbors is Chapman’s latest North O work after 2016’s Northside Carnation about the late community matriarch, Omaha Star publisher Mildred Brown. That earlier play is set in the hours before the 1969 riot that undid North 24th Street. Just as Northside found a home close to Brown and her community at the Elk’s Lodge, Neighbors unfolds where bittersweet events are still fresh in people’s minds.

“The placement of the performance at the Highlander becomes so important,” said Chapman, “because it helps to strengthen that message that we as a community are more and greater than the sum of the travesties and the tragedies.

“Within the middle of all the chaos there are still flowers growing and a whole new community blossoming right there on 30th street in a place that used to not be a great place – partly because they put a freeway in the middle of it.”

Chapman sees clear resonance between what the characters in her play do and what 75 North is doing “to develop the concept of community holistically.”

“It’s housing, food, education and work opportunities and community spaces for people to come together block by block. It’s really exciting to be a part of that.”

ChapMan is sure that Neighbors will evoke memories the same way Northside did.

“For some folks it was like coming home and sharing their stories.”

Additional PlayFest shows feature a full-stage production of previous GPTC Playlab favorite In the City in the City in the City by guest playwright Matthew Capodicasa and a “homage collage” to the work of this year’s honored playwright, Sarah Ruhl, a MacArthur Fellowship recipient. Two of Ruhl’s plays have been finalists for the Pulitzer Prize.

Capodicasa uses a couple’s visit to the mythical city-state of Mastavia as the prism for exploring what we take from a place.

“It’s about how when you’re traveling, you inevitably experience the place through the lens of the people you’re with and how that place is actually this other version of itself – one altered by your presence or curated for your tourist experience,” he said.

In the City gets its world premiere at the Blue Barn Theatre on Tuesday, May 29 at 7:30 p.m. Producing artistic director Susan Clement-Toberer said the piece is “a perfect engine” for the theater’s season-long theme of “connect” because of its own exploration of human connections.” She also appreciates theopen-ended nature of the script. “It’s evocative and compelling without being overly prescriptive. The play can be done in as many ways as there are cities and we are thrilled to bring it to life for the first time.”

You Want to Love Strangers: An Evening in Letters, Lullabies, Essays and Clear Soup celebrates what its director Amy Lane calls Ruhl’s “poetic, magical, lush” playwriting. “Her plays are often like stepping into a fairytale where the unexpected can and does happen. Her work is filled with theatre magic, a childlike sense of wonder, playfulness, mystery. We’ve put together a short collage that includes monologues, scenes and songs from some of her best known works.”

The Ruhl tribute will be staged at the 40th Street Theatre on Friday, June 1 at 7:30 p.m.

All PlayFest performances are free. For details and other festival info, visit http://www.gptcplays.com.

A series commemorating Black History Month – North Omaha stories Part III

A series commemorating Black History Month – North Omaha stories Part II

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/11/16/interfaith-journ…rfaith-walk-work/

Good Shepherds of North Omaha: Ministers and Churches Making a …

https://leoadambiga.com/…/the-shepherds-of-north–omaha–ministers-and- churches-making-a-difference-in-area-of-great-need/

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/30/two-blended-hous…houses-unidvided

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/11/14/small-but-mighty…idst-differences

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/16/everyones-welcom…g-bread-together/

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/02/upon-this-rock-h…trinity-lutheran/

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/gimme-shelter-sa…en-for-searchers

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/01/09/an-open-invitati…-catholic-church

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/15/everything-old-i…-church-in-omaha/

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/03/10/the-sweet-sounds…ts-freedom-choir/

Sacred Heart Freedom Choir | Leo Adam Biga’s My Inside Stories

https://leoadambiga.com/tag/sacred-heart-freedom-choir/

Salem’s Voices of Victory Gospel Choir Gets Justified with the Lord …

https://leoadambiga.com/…/salems-voices-of-victory-gospel-choir-gets- justified-with-the-lord/

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/07/11/the-myers-legacy…ng-and-community/

A Homecoming Like No Other – The Reader

http://thereader.com/news/a-homecoming-like-no-other/

Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All …

https://leoadambiga.com/…/native–omaha–days-a-black-is-beautiful- celebration-now-and-all-the-days-gone-by/

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/11/back-in-the-day-…party-all-in-one

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/05/how-one-family-d…-during-the-days/

Bryant-Fisher | Omaha Magazine

http://omahamagazine.com/articles/tag/bryant-fisher/.

A Family Thing – The Reader | Omaha, Nebraska

http://thereader.com/news/a_family_thing/.

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/11/big-mama’s-keeps…ve-ins-and-dives/

Big Mama, Bigger Heart | Omaha Magazine

http://omahamagazine.com/articles/big-mama-bigger-heart/

Entrepreneur and craftsman John Hargiss invests in North Omaha …

http://thereader.com/visual-art/entrepreneur_and_craftsman_john_hargiss_invests_in_north_omaha/

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/06/30/creative-to-the-…s-handmade-world/

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/09/27/minne-lusa-house…on-and-community/

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/10/22/a-culinary-horti…ommunity-college/

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/08/28/revival-of-benso…estination-place

A Mentoring We Will Go | Leo Adam Biga’s My Inside Stories

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/01/08/tech-maven-lasho…past-stereotypes/

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/08/22/omaha-small-busi…rs-entrepreneurs

Omaha Northwest Radial Hwy | Leo Adam Biga’s My Inside Stories

https://leoadambiga.com/tag/omaha-northwest-radial-hwy/

Isabel Wilkerson | Leo Adam Biga’s My Inside Stories

https://leoadambiga.com/tag/isabel-wilkerson/

The Great Migration comes home – The Reader

http://thereader.com/visual-art/the_great_migration_comes_home/.

Goodwin’s Spencer Street Barber Shop – Leo Adam Biga’s My Inside …

Free Radical Ernie Chambers – The Reader

http://www.thereader.com/post/free_radical_ernie_chambers

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/03/15/deadeye-marcus-m…t-shooter-at-100/

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/01/15/north-omaha-cham…s-the-good-fight

North’s Star: Gene Haynes builds legacy as education leader with …

https://leoadambiga.com/…/norths-star-gene-haynes-builds-legacy-as- education-leader-with-omaha-public-schools-and-north-high-school…

Brenda Council: A public servant’s life | Leo Adam Biga’s My Inside …

https://leoadambiga.com/…/brenda-council-a-public-servants-life/

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/17/carole-woods-har…ess-and-politics/

Radio One Queen Cathy Hughes Rules By Keeping It Real …

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/04/29/radio-one-queen-cathy-hughes…

Miss Leola Says Goodbye | Leo Adam Biga’s My Inside Stories

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/01/miss-leola-says-goodbye/.

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/02/leola-keeps-the-…-side-music-shop/

Aisha Okudi’s story of inspiration and transformation …

http://thereader.com/news/aisha_okudis_story_of_inspiration_and_transformation/

Alesia Lester: A Conversation in the Gossip Salon | Leo …

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/03/09/alesia-lester-a-conversation-in…

http://omahamagazine.com/articles/tag/viv-ewing/

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/02/11/sex-talk-comes-w…rri-nared-brooks/

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/strong-smart-and…-girls-inc-story/

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/13/omaha-couple-exp…ica-in-many-ways

Parenting the Second Time Around Holds Challenges and …

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/11/25/parenting-the-second-time…

Pamela Jo Berry brings art fest to North Omaha – The Reader

http://thereader.com/visual-art/pamela_jo_berry_brings_art_fest_to_north_omaha/

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/06/its-a-hoops-cult…asketball-league/

Tunette Powell | Omaha Magazine

http://omahamagazine.com/articles/tag/tunette-powell/

Finding Her Voice: Tunette Powell Comes Out of the Dark …

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/01/24/finding-her-voice-tunette..

Shonna Dorsey | Omaha Magazine

http://omahamagazine.com/articles/tag/shonna-dorsey/

Finding Normal: Schalisha Walker’s journey finding normal …

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/07/18/finding-normal-schalisha-walker..

A series commemorating Black History Month: North Omaha stories

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

The November issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com) features my story on an old-line but still vital social action organization celebrating 90 years in Omaha.

The Urban League. The name may be familiar but the role it plays not. Since the National Urban League’s 1910 birth from the progressive social work movement, it’s used advocacy over activism to promote equality. The New York City-based NUL encouraged the creation of affiliates to serve blacks leaving the South in the Great Migration. One of its oldest continuously operating affiliates is the Urban League of Nebraska. The local non-profit started in 1927 as the Omaha Urban League and so operated until changing to Urban League of Nebraska (ULN) in 1968.

This century-plus national integrationist organization is anything but a tired old outfit living off 1950s-1960s Freedom Movement laurels. Its mission today within the ongoing movement is “to enable African-Americans to secure economic self-reliance, parity, power and civil rights.” Ditto for ULN, which marks 90 years in 2017. At various times the local office made housing, jobs and health priorities. Today, it does advocacy around juvenile justice, education and child welfare reform and is a service provider of education, youth development, employment and career services programs. It continues a long-standing scholarships program.

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the November 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The Urban League.

The name may be familiar but the role it plays not. Since the National Urban League’s 1910 birth from the progressive social work movement, it’s used advocacy over activism to promote equality. The New York City-based NUL encouraged the creation of affiliates to serve blacks leaving the South in the Great Migration. One of its oldest continuously operating affiliates is the Urban League of Nebraska. The local non-profit started in 1927 as the Omaha Urban League and so operated until changing to Urban League of Nebraska (ULN) in 1968.

This century-plus national integrationist organization is anything but a tired old outfit living off 1950s-1960s Freedom Movement laurels. Its mission today within the ongoing movement is “to enable African-Americans to secure economic self-reliance, parity, power and civil rights.” Ditto for ULN, which marks 90 years in 2017. At various times the local office made housing, jobs and health priorities. Today, it does advocacy around juvenile justice, education and child welfare reform and is a service provider of education, youth development, employment and career services programs. It continues a long-standing scholarships program.

Agency branding says ULN aspires to close “the social economic gap for African-Americans and emerging ethnic communities and disadvantaged families in the achievement of social equality and economic independence and growth.”

The emphasis on education and employment as self-determination pathways became more paramount after the Omaha World-Herald’s 2007 series documenting the city’s disproportionately impoverished African-American population. ULN became a key partner of a facilitator-catalyst for change that emerged – the Empowerment Network. In a decade of focused work, North Omaha blacks are making sharp socio-economic gains.

“It was a call to action,” current ULN president-CEO Thomas Warren said of this concerted response to tackle poverty. “This was the first time in my lifetime I’ve seen this type of grassroots mobilization. It coincided with a number of nonprofit executive directors from this community working collaboratively with one another. It also was, in my opinion, a result of strategically situated elected officials working cooperatively together with a common interest and goal – and with the support of the donor-philanthropic community.

“The United Way of the Midlands wanted their allocations aligned with community needs and priorities – and poverty emerged as a priority. Then, too, we had support from our corporate community. For the first time, there was alignment across sectors and disciplines.”

Unprecedented capital investments are helping repopulate and transform a long neglected and depressed area. Both symbolic and tangible expressions of hope are happening side by side.

“It’s the most significant investment this community’s ever experienced,” said Warren, a North O native who intersected with ULN as a youth. He said the League’s always had a strong presence there. He came to lead ULN in 2008 after 24 years with the Omaha Police Department, where he was the first black chief of police.

“I was very familiar with the organization and the importance of its work.”

He received an Urban League scholarship upon graduating Tech High School. A local UL legend, the late Charles B. Washington, was a mentor to Warren, whose wife Aileen once served as vice president of programs.

Warren concedes some may question the relevance of a traditional civil rights organization that prefers the board room and classroom to Black Lives Matter street tactics.

“When asked the relevance, I say it’s improving our community and changing lives,” he said, “We prefer to engage in action and to address issues by working within institutions to affect change. As contrasted to activism, we don’t engage much in public protests. We’re more results-oriented versus seeking attention. As a result, there may not be as much public recognition or acknowledgment of the work we do, but I can tell you we have seen the fruits of our efforts.”

“We’re an advocacy organization and we’re a services and solutions provider. We’re not trying to drum up controversy based on an issue,” said board chairman Jason Hansen, an American National Bank executive. “We talk about poverty a lot because poverty’s the powder keg for a lot of unrest.”

Impacting people where they live, Warren said, is vital if “we want to make sure the organization is vibrant, relevant, vital to ensuring this community prospers.”

“We deal with this complex social-economic condition called poverty,” he said. “I take a very realistic approach to problem-solving. My focus is on addressing the root causes, not the symptoms. That means engaging in conversations that are sometimes unpleasant.”

Warren said quantifiable differences are being made.

“Fortunately, we have seen the dial move in a significant manner relative to the metrics we measure and the issues we attempt to address. Whether disparities in employment, poverty, educational attainment, graduation rates, we’ve seen significant progress in the last 10 years. Certainly, we still have a ways to go.”

The gains may outstrip anything seen here before.

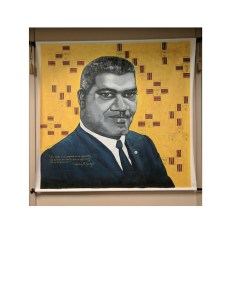

Soon after the local affiliate’s start, the Great Depression hit. The then-Omaha Urban League carried out the national charter before transitioning into a community center (housed at the Webster Exchange Building) hosting social-recreational activities as well as doing job placements. In the 1940s, the Omaha League returned to its social justice roots by addressing ever more pressing housing and job disparities. When the late Whitney Young Jr. came to head the League in 1950, he took the revitalized organization to new levels of activism before leaving in 1953. He went on to become national UL executive director, he spoke at the March on Washington and advised presidents. A mural of him is displayed in the ULN lobby.

Warren’s an admirer of Young, “the militant mediator,” whose historic civil rights work makes him the local League’s great legacy leader. In Omaha, Young worked with white allies in corporate and government circles as well as with black churches and the militant social action group the De Porres Club led by Fr. John Markoe to address discrimination. During Young’s tenure, modest inroads were made in fair hiring and housing practices.

Long after Young left, the Near North Side suffered damaging blows it’s only now recovering from. The League, along with the NAACP, 4CL, Wesley House, YMCA, Omaha OIC and other players responded to deteriorating conditions through protests and programs.

League stalwarts-community activists Dorothy Eure and Lurlene Johnson were among a group of parents whose federal lawsuit forced the Omaha Public Schools to desegregate. ULN sponsored its own community affairs television program, “Omaha Can We Do,” hosted by Warren’s mentor, Charles Washington.

Mary Thomas has worked 43 years at ULN, where she’s known as “Mrs. T.” She said Washington and another departed friend, Dorothy Eure, “really helped me along the way and guided me on some of the things I got involved in in civil rights. Thanks to them, I marched against discrimination, against police brutality, for affirmative action, for integrated schools.”

Rozalyn Bredow, ULN director of Employment and Career Services, said being an Urban Leaguer means being “involved in social programs, activism, voter rights, equal rights, women’s rights – it’s wanting to be part of the solution, the movement, whatever the movement is at the time.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, ULN changed to being a social services conduit under George Dillard.

“We called George Dillard Mr. D,” said Mrs. T. “A very good, strong man. He knew the Urban League movement well.”

She said the same way Washington and Eure schooled her in ciivl rights, Dillard and his predecessor, George Dean, taught her the Urban League movement.

“We were dealing with a multiplicity of issues at that particular time,” Dillard said, “and I imagine they’re still dealing with them now. At the time I took over, the organization had been through two or three different CEOs in about a five year period of time. That kind of turnover does not stabilize an organization. It hampers your program and mission.”

Dillard got things rolling. He formed a committee tasked with monitoring the Omaha Public Schools desegregation plan “to ensure it did not adversely affect our kids.” He implemented a black community roundtable for stakeholders “to discuss issues affecting our community.” He began a black college tour.

After his departure, ULN went through another quick succession of directors. It struggled meeting community expectations. Upon Thomas Warren’s arrival, regaining credibility and stability became his top priority. He began by reorganizing the board.

“When I started here in 2008 we had eight employees and an operating budget of $800,000, which was about $150,000 in the red,” Warren said. “Relationships had been strained with our corporate partners and with our donor-philanthropic community, including United Way. My first order of business was to restore our reputation by reestablishing relationships.”

His OPD track record helped smooth things over.

“As we were looking to get support for our programs and services, individuals were willing to listen to me. They wanted to know we would be administering quality services. They wanted to know our goals and measurable outcomes. We just rolled up our sleeves and went to work because during the recession there was a tremendous increase in demand for services. Nonprofits were struggling. But we met the challenge.

“In the first five years we doubled our staff. Tripled our budget. Currently, we manage a $3 million operating budget. We have 34 full-time employees. Another 24 part-time employees.”

Under Warren. ULN’s twice received perfect assessment scores from on-site national audits.

“It’s a standard of excellence for our adherence to best practices and compliance with the Urban League’s articles of affiliation,” he said.

Financially, the organization’s on sound footing.

“We’ve done a really admirable job of diversifying our revenue stream. More than 85 percent of our revenue comes from sources other than federal and state grants,” said board chair Jason Hansen. “We have a cash reserve exceeding what the organization’s entire budget was in 2008. It’s really a testament to strong fiscal management – and donors want to see that.”

“It was very important we manage our resources efficiently,” Warren said.

Along the way, ULN itself has been a jobs creator by hiring additional staff to run expanding programs.

“The growth was incremental and methodical,” Warren said, “We didn’t want to grow too big, too fast. We wanted to be able to sustain our programs. Our ability to administer quality programs got the support of our donor-philanthropic-corporate-public communities.

“We have been able to maintain our workforce and sustain our programs. The credit is due to our staff and to the leadership provided by our board of directors.”

Warren’s 10 years at the top of ULN is the longest since Dillard’s reign from 1983 to 2000. Under Warren, the organization’s back to more of its social justice past.

Even though Mrs. T’s firebrand activism is not the League’s style, sometimes causing her to clash with the reserved Warren, whom she calls “Chief,” she said they share the same values.

“We just try to correct the wrong that’s done to people. I always have liked to right a wrong.”

She also likes it when Warren breaks his reserve to tell it like it is to corporate big wigs and elected officials.

“When he’s fighting for what he believes, Chief can really be angry and forceful, and they can’t pull the wool over his eyes because he sees through it.”

Mrs. T feels ULN’s back to where it was under Dillard.

“It was very strong then and I feel it’s very strong now. In between Mr. D and Chief, we had a number of acting or interim directors and even though those people meant well, until you get somebody solid, you’ve got a weakness in there.”

Pat Brown agrees. She’s been an Urban Leaguer since 1962. Her involvement deepened after joining the ULN Guild in 1968. The Guild’s organized everything from a bottillon to fundraisers to nursing home visits.

“Things were hopping. We had everything going on and everything running smoothly taking part in community things, working with youth, putting on events.”

She sees it all happening again.

Kathy J. Trotter also has a long history with the League. She reactivated the guild, which is ULN’s civic engagement-fundraising arm. She said countless volunteers, including herself, have “grown” through community service, awareness and leadership development through Guild activities. She chaperoned its black college tour for many years.

Trotter likes “to share our vision that a strong African- American community is a better Nebraska” with ULN’s diverse collaborators and partners.

Much of ULN’s multicultural work happens behind-the-scenes with CEOs, elected officials and other stakeholders. ULN volunteers like Trotter, Mrs. T and Pat Brown as well as Warren and staff often meet notables in pursuit of the movement’s aims.

“I don’t think people realize the amount of work we do and the sheer number of programs and services we provide in education, workforce development, violence prevention,” Jason Hansen said. “We have programs and services tailored to fit the community.”

Most are free.

“When you talk about training the job force of tomorrow, it begins with youth and education,” Hansen said. “We’ve seen a significant rise of African-Americans with a four-year college degree. That’s going to provide a better pipeline of talent to serve Omaha.”

Warren devised a strategic niche for ULN.

“We narrowed our focus on those areas where we not only felt we have expertise but where we could have the greatest impact,” he said. “If we have clients who need supportive services, we simply refer them.”

Some referrals go to neighbors Salem Baptist Church, Charles Drew Health Center, Family Housing Advisory Services, Omaha Small Business Network and Omaha Economic Development Corporation.

“We feel we can increase our efficiency and capacity by collaboration with those organizations.”

EDUCATION

Since refocusing its efforts, ULN regularly lands grants and contracts to administer education programs for entities like Collective for Youth.

ULN works closely with the Omaha Public Schools on addressing truancy. It utilizes African-American young professionals as Youth Attendance Navigators to mentor target students in select elementary and high schools to keep them in school and graduating on time.

Community Coaches work with at-risk youth who may have been in the juvenile justice system, providing guidance in navigating high school on through college.

ULN also administers some after school programs.

“Many of these kids want to know someone cares about their fate and well-being,” Warren said. “It’s mentoring relationships. We can also provide supportive services to their families.”

The Whitney Young Jr. Academy and Project Ready provide students college preparatory support ranging from campus tours to applications assistance to test prep to essay writing workshops to financial aid literacy.

“Many of them are first-generation college students and that process can be somewhat demanding and intimidating. We’re going to prepare the next generation of leaders here and we want to make sure they’re ready for school, for work, for life.”

Like other ULN staff, Academy-Project Ready coordinator Nicole Mitchell can identify with clients.

“Growing up in the Logan Fontanelle projects, I was just like the students I work with. There’s a lot I didn’t get to do or couldn’t do because of economics or other barriers, so my heart and passion is to make sure that when things look impossible for kids they know that anything is possible if you put the work and resources behind it. We make sure they have a plan for life after high school. College is one focus, but we know college is not for everyone, so we give them other options besides just post-secondary studies.”

“We want to make sure we break down any barrier that prevents them from following their dreams and being productive citizens. Currently, we have 127 students, ages 13 to 18, enrolled in our academy.”

Whitney Young Jr. Academy graduates are doing well.

“We currently have students attending 34 institutions of higher education,” said ULN College Specialist Jeffrey Williams. “Many have done internships. Ninety-eight percent of Urban League of Nebraska Scholarship recipients are still enrolled in college going back to 2014. One hundred percent of recipients are high school graduates, with 79% of them having GPAs above 3.0.”

Warren touts the student support in place.

“We work with them throughout high school with our supplemental ed programs, our college preparatory programs, making sure they graduate high school and enroll in a post-secondary education institution. And that’s where we’ve seen significant improvements.

“When I started at the Urban League, the graduation rate for African-American students was 65 percent in OPS. Now it’s about 80 percent. That’s statistically significant and it’s holding. We’ve seen significant increases in enrollment in post-secondary – both in community colleges and four-year colleges and universities. UNO and UNL have reported record enrollments of African-American students. More importantly, we’ve seen significant increases in African-Americans earning bachelor degrees – from roughly 16 percent in 2011 to 25 percent in 2016.”

With achievement up, the goal is keeping talent here.

TALENT RETENTION

A survey ULN did in partnership with the Omaha Chamber of Commerce confirmed earlier findings that African-American young professionals consider Omaha an unfavorable place to live and work. ULN has a robust young professionals group.

“It was a call to action to me personally and professionally and for our community to see what we can do cultivate and retain our young professionals,” Warren said. “The main issues that came up were hiring and promotions, professional growth and development, mentoring and pay being commensurate with credentials. There was also a strong interest in entrepreneurship expressed.

“Millenials want to work in a diverse, inclusive environment. If we don’t create that type of environment, they’re going to leave. We want to use the results as a tool to drive some of these conversations and ultimately have an impact on seeing things change. If we are to prosper as a community, we have to retain our talent as a matter of necessity.We export more talent than we import. We need to keep our best and brightest. It’s in our own best interest as a community.”

The results didn’t surprise Richard Webb, ULN Young Professionals chair and CEO of 100 Black Men Omaha.

“I grew up in this community, so I definitely understand the atmosphere that was created. We’ve known the problems for a long time, but it seemed like we never had never enough momentum to make any changes. With the commitment and response we’ve got from the community, I feel there’s a lot of momentum now for pushing these issues to the front and finding solutions.”

“Corporate Omaha needs to partner with us and others on how we make it a more inclusive environment,” Jason Hansen said.

With the North O narrative changing from hopeless to hopeful, Hansen said, “Now we’re talking about how do we retain our African-American young talent and keep them vested in Omaha and I’d much rather be fighting that problem than continued increase in poverty and violence and declining graduation rates.

Webb’s attracted to ULN’s commitment to change.

“It’s representing a voice to empower people from the community with avenues up and out. It gathers resources and put families in better positions to make it out of The Hood or into a situation where they’re -self-sustaining.”

CAREER READINESS

On the jobs front, ULN conducts career boot camps and hosts job fairs. It runs a welfare to work readiness program for ResCare.

“We administer the Step-Up program for the Empowerment Network,” Warren said. “We case managed 150-plus youth this past summer at work sites throughout the city. We provide coaches that provide those youth with feedback and supervise their performance at the worksites.”

Combined with the education pieces, he said, “The continuum of services we offer can now start as early as elementary school. We can work with youth and young adults as they go on through college and enter into their careers. Kids who started with us 10 years ago in middle school are enrolled in college now and in some cases have finished school and entered the workforce.”

The Urban League maintains a year-round presence in the Community Engagement Center at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

Olivia Cobb is part of another population segment the League focuses on: adults in adverse circumstances looking to enhance their education and employability.

Intensive case management gets clients job-school ready.

After high school, Cobb began studying nursing at Metropolitan Community College but gave birth to two children and dropped out. Through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act program ULN administers, the single mom got the support she needed to reenter school. She’s on track to graduate with a nursing degree from Iowa Western Community College.

“I just feel like I’ve started a whole new chapter of my life,” Cobb said. “I was discouraged for awhile when I started having children. I thought I was going to have to figure something else out. I’m happy I started back. I feel like I’ve put myself on a whole new level.

“The Urban League is like another support. I can always go to them about anything.”

George Dillard said it’s always been this way.

“A lot of the stuff the Urban League does is not readily visible. But if you talk with the clients who use the Urban League, you’ll find the services it provides are a welcome addition to their lives. That’s what the Urban League is about – making people’s lives easier.”

ULN’s Rozalyn Bredow said Cobb is one of many success stories. Bredow’s own niece is an example.

“She wanted to be a nurse but she became a teen parent. She went to Flanagan High, graduated, did daycare for awhile. She finally came into the Workforce Innovation program. She went to nursing school and today she’s a nurse at Bergan Mercy.”

Many Workforce Innovation graduates enter the trades. Nathaniel Schrawyers went on to earn his commercial driver’s license at JTL Truck Driver Training and now works for Valmont Industries.

Like Warren, Bredow is a former law enforcement officer and she said, “We know employment helps curb crime. If people are employed and busy, they don’t have a whole lot of time to get into nonsense. And we know people want to work. That’s why we’ve expanded our employment and career services.”

VIOLENCE PREVENTION

The League’s violence prevention initiatives include: Credit recovery to obtain a high school diploma; remedial and tutorial education; life skills management; college prep; career exploration; and job training.

“Gun assaults in the summer months in North Omaha are down 80 percent compared to 10 years ago,” Warren said. “That means our community is safer. Also,the rate of confinement at the Douglas County Youth Center is down 50 percent compared to five years ago. That means our youth and young adults are being engaged in pro-social activities and staying out of the system – leading productive lives and becoming contributing citizens.”

Warren co-chairs the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative. “Our work is designed to keep our youth out of the system or to divert those that have been exposed to the system to offer effective intervention strategies.”

Richard Webb said having positive options is vital.

“It’s a mindset thing. Whenever people are seeing these resources available in their community to make it to greatness, then they do start changing their minds and realizing they do have other options.

“Growing up, I didn’t feel I had too many options in my footprint. My mom was below poverty level. My dad wasn’t in the house.”

But mentoring by none than other than Thomas Warren helped him turn his life around. He finished high school. earned an associates degree from Kaplan University and a bachelor’s degree from UNO. After working in sales and marketing, he now heads a nonprofit.

Wayne Brown, ULN vice president of programs, knows the power of pathways.

“My family was part of the ‘alternative economy.’ It was the family business. My junior year at Omaha Benson I was bumping around, making noise, when an Urban League representative named Chris Wiley grabbed me by the ear and gpt me to take the college and military assessment tests. He made sure I went on a black college tour. I met my wife on that tour. I got a chance to be around young people going in the college direction and I had a good time.”

Brown joined the Army after graduating high school and after a nine year service career he graduated from East Tennessee State University and Creighton Law School. After working for Avenue Scholars and the Omaha Community Foundation, he feels like he’s back home.

“I wouldn’t have been able to do all that if I hadn’t done what Mr. Wiley pushed me to do. So the Urban League gave me a start, a path to education and employment and a sense of purpose I didn’t have before.”

Informally and formally, ULN’s been impacting lives for nine decades.

“To be active in Omaha for 90 years, to have held on that long, is fantastic,” Pat Brown said. “Some affiliates have faltered and failed and gone out of business. But to think we’re still working and going strong says something. I hope I’m around for the 100th anniversary.”

Mrs. T rues the wrongs inflicted on the black community. But she’s pleased the League’s leading a revival.

“I’ve seen some good changes. It makes me feel good we are still here and still standing and that I’m around to see that. It’s a good change that’s coming.”

Visit http://www.urbanleagueneb.org.

Omaha Small Business Network Empowers Entrepreneurs

If you’re an entrepreneur seeking to establish or take your start-up to the next level, then the Omaha Small Business Network may be the place for you. Julia Parker (pictured below) is the latest in a succession of women of color to head the OSBN. The OSBN is located at the historic 24th and Lake hub where a revitalization is happening. North Omaha entrepreneurs might want to look at working with the organization to help make their dreams come true and perhaps be a part of the North O revival. Read my B2B Omaha Magazine (http://omahamagazine.com/) feature about the services and programs the OSBN offers.

Omaha Small Business Network

Omaha Small Business Network

Empowers Entrepreneurs

©By Leo Adam Biga

©Photography by Bill Sitzmann

Originally published in Jan-Feb 2017 issue of Omaha Magazine (http://omahamagazine.com/)

The Omaha Small Business Network is on its third female executive director since its 1982 launch. Julia Parker leads an all-female full-time staff that continues the nonprofit’s founding mandate to assist historically undercapitalized entrepreneurs achieve financial inclusion.

OSBN helps remove barriers that inhibit some women and racial minorities from realizing business ventures. Parker says clients lack access to capital and lines of credit and often have no formal business training. Lacking collateral, they’re rejected by lenders. “To be eligible for our micro-loans, the first qualification is you be turned down for traditional financing,” Parker says.

OSBN helps “un-bankable” clients do a financial makeover.

“What OSBN seeks to do is to initially bridge that gap between the bank and the consumer. But after receiving an OSBN loan, our desire is for you to become bankable. We really hope after that two- or three- or six-year loan you develop a relationship with a local banker, through strong payments and good credit history, and then take the leap into the traditional financial market,” she says. “That’s really where we want you to go and thrive.”

On The Edge Technology co-owner Rebecca Weitzel credits a $35,000 OSBN micro-loan, plus information gleaned from OSBN classes, and network opportunities with helping grow her firm and navigate the economics of doing business. She explored options at banks and credit unions before deciding OSBN was “the best choice for us.”

“Each opportunity with OSBN helped develop my confidence as a business owner. Now, I refer other people to OSBN that want to start or grow a business,” says Weitzel.

OSBN offers a three-pronged support system: micro-loans between $1,000 and $50,000 at low interest rates; free monthly professional development and small business training classes; and below-market-rate commercial office spaces at Omaha Business and Technology Center (2505 N. 24th St.) and two nearby buildings. Ken and Associates LLC is one of two dozen OSBN tenants benefiting from commercial office space renting for 80 percent less than market value.

OSBN has lent $2 million-plus in micro-loans to startups and existing businesses since it began micro-lending in 2010.

As of October 2016, OSBN had $500,000 in outstanding loans, with $300,000 in loan payoffs during the past calendar year.

Parker says, “Those are big numbers. Our clients are paying off their loans and going on their way as successful entrepreneurs. We’re pretty proud of that.”

Spencer Management LLC owner Justin Moore is another OSBN success story.

Since receiving a $35,000 micro-loan, Parker says his business expanded services, moved to a new, larger facility, paid off the loan in full, and exceeded $1 million in annual revenue.

As a micro-enterprise development entity, OSBN is funded by private donations from local philanthropists and banks.

Parker leverages her plugged-in experience in the nonprofit and business arenas. She served as director of operations and communications at Building Bright Futures from 2007 to 2013. She applies the skills she used there, along with lessons learned as a black female running a small business, to engage OSBN clients and partners. She owns her own communications consulting agency.

“I think there’s always a barrier for minorities in certain spaces in Omaha,” she says. “The key is to try and overcome those by having a strong work ethic and being on top of your game at all times. But I think across the city, no matter what sector you’re in, there are barriers to entry.”

She reports to a board whose members represent public and private interests. OSBN partners with leading Omaha giving institutions to even the playing field.

“With the support of the Sherwood Foundation,” she says, “we have created a loan pool specifically for minority contractors and suppliers because of the issues they face. And we’ve teamed up with Creighton’s Financial Hope Collaborative to put those contractors and suppliers through a 12-week training course to ensure they’re prepared to go out and bid on, win, and fulfill those contracts. We just completed our first cohort and started our second.”

Parker likes helping dreams be realized. It’s why she said yes when the board offered her the job in 2013.

“I took the position because I really believe in the mission of supporting low-to-moderate-income entrepreneurs. I also like the idea of micro-enterprise development and its very unique take on financial inclusion.”

She described that mission in testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship on Capitol Hill last August. She says OSBN is “dedicated to bringing underserved local small business owners, entrepreneurs, and nonprofits the tools needed to become successful and sustainable entities.” She added, “OSBN and like-minded, community-based micro-lenders…have the ability to become a catalyst for both community and economic development.”

She sees OSBN playing a role in increasing the dearth of black middle class residents and small business owners in northeast Omaha and stimulating economic revival there.

“Small business ownership has long been held as a path to financial inclusion. Owning your own business allows you to break that cycle of poverty. Often those businesses become generational. We would love to see the 24th Street corridor come alive again with small businesses.”

Besides, she says, small businesses have a positive ripple effect by creating jobs and paying taxes.

Visit osbnbtc.org for more information.

A systems approach to addressing food insecurity in North Omaha

Nancy Williams with No More Empty Pots and other players are taking a systems approach to addressing food insecuity in North Omaha.

A systems approach to addressing food insecurity

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Food insecurity in northeast Omaha is a question of access, education and poverty.

Nancy Williams has designed her nonprofit No More Empty Pots around “equitable access to local, fresh, affordable food” via a holistic approach. It offers the Community Market Basket CSA (community supported agriculture) as well as shared commercial kitchens, a training kitchen and classes. Its Food Hub in Florence is adding a business incubator, community cafe, kids kitchen and rooftop garden.

“We could just do one thing and satisfy a symptom, but we’re trying to address the root cause issue of poverty – of which hunger is a symptom. The food hub concept is a systems approach to not just deal with hunger but to get people trained and hired and to support startup businesses. So we have a multi-pronged approach to supporting local food and supporting people who need access to food and the people providing that food.

“Poverty is not just about food deserts and hunger. it’s about livable wages, adequate education, meaningful connections. It’s about being able to take advantage of the opportunities in front of you. It’s about people engaging. You see, it’s one thing to get people to food because they’re hungry or they don’t have access to it. It’s even something more if they have access to living wage jobs where they can then choose their food.”

Pots is based in North Omaha, she said, in recognition of its “rich cultural heritage of food and community” and concurrent “disparities in health, healthy food access, equity and economics.”

“So, we wanted to make a difference there first, then catalyze a ripple effect in urban, suburban and rural spaces. We believe in the reciprocity of local food.”

An effective food system involves a social contract of public-private players. In Omaha it includes United Way, Together, the Food Bank, Saving Grace Perishable Food Rescue, vendors, producers, schools, churches.

“It’s not a simple thing to talk about food access and deserts,” Williams said. “It’s a whole system of the way we produce food and get food to people, the way people consume it and how we value it. The different ways intersect. It takes all of it. But there needs to be some calibration, hole-plugging and shifting.

“We can get there, but it has to be done collaboratively so we’re not working in silos.”

On the access-education-employment side are community gardens and urban farms like those at City Sprouts, which also offers classes and internships. A farmers market is held there, too. Charles Drew Health Center and Florence Mill also host farmers markets.

Minne Lusa House is a neighborhood engagement-sustainability activator..

Some churches, including Shepherd of the Hills and New Life Presbyterian, provide free monthly community meals. New Life also provides food to participants in its youth summer enrichment program.

“There are food insecure kids that come,” pastor Dwight Williams said. “There is a lot more need than we are able to access.”