Archive

Louder Than a Bomb Omaha: Stand, deliver and be heard

The reverberation of Louder Than a Bomb, the Chicago slam festival, competition, and documentary, has reached Omaha and spawned a youth poetry slam here that runs April 15-22. As movements go, I must admit that while I’ve been vaguely aware of the growing popularity of poetry slams I’ve never attended one and I’ve only seen a few spoken word artists perform. But it’s not like this is completely foreign territory to me because I have heard and seen my share of authors and storytellers do readings. In the same vein, I’ve attended a few play readings, and so I do have a pretty fair notion for what this is about. Of course, the competitive nature of slams sets this apart from the others. Now that the youth poetry slam format is getting a major showcase in my hometown I find myself covering it, which brings us to the following post, which is essentially a preview of that event through the prism of what is driving this phenomenon of slams springing up around the country, even in my middle America.

NOTE: Check out my companion story on this blog about Omaha South High poetry slam team member Marissa Gomez. And for all you poetry fans out there, this blog has stories about Ted Kooser, William Kloekforn, and any number of literary lights.

Louder Than a Bomb Omaha: Stand, deliver and be heard

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Poetry slams pit individuals or teams in bouts of spoken word street soliloquies that bring performers and spectators to tears and cheers the way performing arts and sports events do.

Omaha‘s long been home to a thriving adult slam scene, thanks to poet Matt Mason and the Nebraska Writers Collective (NWC), who’ve lately cultivated youths by sending established resident and visiting poets into schools.

All that nurturing comes to a head at the April 15-22 Louder Than a Bomb youth poetry festival and competition, when some 120 students from 12 area high schools battle for poetic supremacy. It’s inspired by a movement based in Chicago, where slam began at the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge and where Louder Than a Bomb originated with the Young Chicago Authors collective.

It turns out Omaha’s a spoken word hotbed itself.

“We have one of the best poetry communities in the country, the talent level is really through the roof,” says Mason. “We send a team to the national poetry slam every year and we do pretty well in the competition but mostly people come to respect the folks here as writers who do really interesting work. People from other cities come to the Omaha bouts to see what kinds of things we’re writing about and doing. We’ve got nationally recognized poets like Dan Leamen and Johnmark Huscher.”

South High resident poet Katie F-S coaches the school’s LTaB team.

“We’re lucky in Omaha that as a crossroads for the nation we get a good amount of really quality touring poets coming through here,” says Mason. “We’re able to take advantage of that and make it even more appealing for them by paying them to run workshops or do shows for students.”

World champion slam poet Chris August came in March.

Mason long envisioned a metro youth poetry slam and began laying the groundwork for it with NWC’s work in schools. “We’ve been running a pilot program at South High called Poets on Loan that sends teams of poets into schools to give students a real taste of some of the best in the field,” he says. With help from those poet mentors South staged a December slam.

Things “accelerated” when a documentary about Chicago’s LTaB became a national sensation. It found a receptive audience at Film Streams. Support quickly surfaced for an Omaha slam modeled after LTaB Chicago. Poet and LTaB co-founder Chicago Kevin Coval visited Omaha in February at Mason’s invitation to do workshops. Mason joined a group of Omahans attending Chicago’s March slam at Coval’s invite. A local contingent may attend a Chicago summer slam institute.

Why all the buzz? South High poetry slam team members Marissa Gomez and Marisha Guffey say the power of spoken word is as simple as being “heard.”

Mason says it provides a safe, communal forum to unleash raw, personal stories and perspectives otherwise denied kids.

“No matter who we are, no matter if you come from a broken background or a well-to-do background, being a teenager is difficult, it’s insane, it’s brutal, it’s all sorts of different things,,” he says. “But something like poetry and this kind of expression of poetry especially is a way of channeling and processing and looking at your world in a different light that makes it come a little bit clearer and easier to deal with or to at least understand.”

“That kind of courage and commitment is necessary for great poetry to flourish,” says Katie F-S.

South High teacher Carol McClellan, who has several of the school’s poetry slam team members in her creative writing class, holds open mic sessions on Fridays. “I’m often amazed at their candor and honesty. It’s been a gradual process as they developed trust and a willingness to open up in the class. From a teacher’s perspective, it’s extremely gratifying to witness.”

Coval says spoken word fills intrinsic needs.

“We as people just have a desire to be heard and to be seen, so we’re providing public space for young people to talk about things they care about – who they are, where they’re from, what are their dreams, what are their fears, their dissatisfactions. It’s a a very simple form, it’s a very ancient process.,” he says. “We’re doing the work of just standing up in a public space and telling stories. People have been doing that since before civilization, so I think this is in some ways a call back to that. It’s a call to reengage young people in their own process of education.”

Coval uses himself to illustrate the medium’s transformational power.

“I certainly was not the best student in the world, but once I started reading and writing on my own and I could follow my own interests I became hyper-literate, and in part that’s what hip hop taught me to do. I think that’s what the movement of hip hop poetry and spoken word is encouraging other young people to do.”

South principal Cara Riggs, whom Coval and Mason give a shout-out for her support of spoken word, sees it as a powerful avenue to engage kids. “The format of a poetry slam is so hip and contemporary to our urban kids. It is a beautiful way for them to express themselves and the audiences are always so amazing in their feedback. The events are contagious to kids…they want more.” Besides, she says, “as a performing arts high school, I just thought it belonged here.”

She says South’s poetry slam had “kids coming out of the woodwork with their own hidden talents and supported by their classmates for their brave expression.”

Mason says schools should embrace spoken word because it promotes “creativity, writing, expression” and it “catches students’ interest and imagination.”

“I think specifically the model of Louder Than a Bomb is about engaging educational institutions around the idea of a team sport in some ways,” says Coval. “And so as opposed to just me as an individual poet coming to a place and reading my poem I’m coming representing a community. You’re going to hear what your city sounds like collectively from the voices of the young people that live here.”

Coval says Omaha like other cities is rife with segregation that divides people and LTaB “is an opportunity to come together across those boundaries that typically keep us from hearing one another.”

Mason joins Coval in suggesting spoken word can promote harmony, saying, “It can unite a city by bringing students from different parts of the community together in one room telling their stories and finding connections.” Youths interacting in this way, says Mason, realize “that no matter what community you’re from you face some of the same struggles and some that are completely different. Gaining an understanding of those struggles can really help you help our community.”

He hopes to grow the spoken word culture and encourage poets to stay here. “This community has so much talent with creative writing and not a lot of outlets. It’s about creating opportunities for students to explore writing in a fun and constructive way and giving established poets an opportunity to earn money as coaches.”

Yes, LTaB is a competition with points and prizes, but it’s mainly about affirmation and bragging rights. The mantra, says Mason, “is bring the next one up. It’s not about getting to the top of the mountain alone, it’s about helping everybody up. It’s a real pleasure to encourage and recognize young poets.”

Word.

Round One prelims are April 15 at the PS Collective, 6056 Maple Street. Round Two prelims are April 17-18 at the OM Center, 1216 Howard Street. The Finals are April 20 at the Harper Center Auditorium at Creighton University.

For schedule details visit ltabomaha.org.

Related articles

- Boston’s Best Spoken Word And Poetry Venues (boston.cbslocal.com)

- Best Venues For Spoken Word and Poetry Readings In DFW (dfw.cbslocal.com)

- It’s Slam Time! (chicagotalks.org)

- Omaha South High Student Marissa Gomez Will Stand, Deliver and Be Heard at Louder Than a Bomb Omaha Youth Poetry Festival and Competition (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From Reporter to Teacher, Carol Kloss McClellan Enjoys Her New Challenge as an Inner City Public High School Instructor (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Louder Than a Bomb Omaha Youth Slam Poetry Festival: “the point is the poetry, the point is the people” (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Lincoln High slam poets to perform (journalstar.com)

House of Loom weaves a new cultural-social dynamic for Omaha

Urban hot spots come and go. A rocking new one in Omaha that’s all the rage is House of Loom. What it’s staying power is no one knows, but it’s almost beside the point as far as co-founder Brent Crampton is concerned. He’s more about using the venue as a launching pad for socially and culturally progressive ideas and connections that assume a life of their own than he is in making the place a runaway commercial success. So far, he and his partners seem to be doing both. Crampton is another in a long and growing line of creatives making an impact here and his House of Loom is another tangible expression of the more sophisticated and diverse cultural menu emerging in this once sleepy Midwest burg that has awakened. Omaha has actually come into its own as a hopping place where there’s always something compelling going on no matter what you’re into. This blog is full of profiles about the persons and places transforming the city into a cosmo receiving center and exporter of new, different, engaging stuff. Much more to come. Keep reading and checking back.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in Encounter Magazine

For a startup bar, House of Loom at 1012 South 10th St. is generating mucho buzz. The reasons for its popularity are as eclectic as the place and the young creatives behind it.

Start with the name. It’s both a brand and a social theory that co-owner and music director Brent Crampton, a DJ by trade, conceived with business partner Jay Kline. Five years ago they launched loom, with a small l, as a roaming multicultural dance party aimed at getting people who normally don’t mix to meet, experience new cultures, form social networks and have fun.

“I have a passion for bringing people together,” says Crampton.

It never sat right with him that despite the Afro-beats he played, his DJing gigs drew mostly white crowds. Under the loom name he began inviting diverse audiences to intersect over music or art or causes at theme nights. “Cultural ambassadors” spread the word.

“These are people who are naturally connectors who have a social network within a certain cultural demographic,” says Crampton. “Through networking we have a lot of people who are into what we’re doing and support us.”

For Crampton and Kline, loom describes their intent to weave the social fabric through music, dance and other art forms, thereby broadening the cultural experience and moving forward social progress. With his Russell Brand looks and persona, Crampton’s a new-school hipster at ease talking about groove as an instrument of change.

He, Kline (the former owner of Fluxiron Gallery) and a third partner, entrepreneur Ethan Bondelid, made loom hot ticket events. The turnouts and cachet kept growing but loom lacked a home of its own. By the partners leasing and renovating the former site of Bones, the Stork Club and the Neon Goose, they now have a distinctly urban space with more flexibility to entertain patrons and promote social agenda issues.

“It opens up possibilities to a lot of great things,” says Crampton.

Bondelid says it’s all about “getting people to try new things,” adding, “We invite people to go on an experience with us.”

Regulars have followed Crampton and Co. to the House of Loom’s near-Old Market location. First-timers are quickly becoming devotees. With a decor equal parts classic Old World bar, nouveau club, chic salon and kitsch bordello it has a warm, funky ambience that, combined with an intimate scale, encourages staying awhile and interacting.

“The idea is for it to look really nice but we don’t want any form of pretentiousness. We just want a nice, unique, comfortable place that does look elegant in its own way,” says Bondelid.

Curtains can be drawn and furniture rearranged to create more private or open spaces.

A custom-built booth is where Crampton and guest MCs ignite the music. LED lights frame the electric mood. When weather permits, an outdoor patio and garden offer an open-air hang-out.

House of Loom has hosted everything from an Omaha Table Talk dinner to an Opera Omaha night to a Project Interfaith speed dialogue to a celebration of India’s Festival of Lights to a Tango Night to private parties, tastings and spoken word events. It’s an in meet-up spot for arts patrons before and after shows. Featured bands have played Cuban, hip-hop, jazz and a myriad of other music.

Catered international cuisine accompanies some events.

The cultural mix happens in a blend of music, food, ideas, personalities and walks-of-life. Bondelid says House of Loom is a haven for creative class urban adventurers seeking to sample “all different kinds” of experiences and expressions.

For events, bookings and hours, visit http://www.houseofloom.com or call 402-505-5494.

Related articles

- Art Trumps Hate: ‘Brundinar’ Children’s Opera Survives as Defiant Testament from the Holocaust (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Living the Dream: Cinema Maven Rachel Jacobson – the Woman Behind Film Streams (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Art as Revolution: Brigitte McQueen’s Union for Contemporary Art Reimagines What’s Possible in North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Film Festival Celebrates Seven Years of Growing the Local Film Culture (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- To Doha and Back with Love, Local Journalists Reflect on Their Fear and Loathing Adventure in the Gulf (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Nancy Kirk: Arts Maven, Author, Communicator, Entrepreneur, Interfaith Champion (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Soul on Ice – Man on Fire: The Charles Bryant Story (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Never is anyone simply what they appear to be on the surface. Deep rivers run on the inisde of even the most seemingly easy to peg personalties and lives. Many of those well guarded currents cannot be seen unless we take the time to get to know someone and they reveal what’s on the inside. But seeing the complexity of what is there requires that we also put aside our blinders of assumptions and perceptions. That’s when we learn that no one is ever one thing or another. Take the late Charles Bryant. He was indeed as tough as his outward appearance and exploits as a one-time football and wrestling competitor suggested. But as I found he was also a man who carried around with him great wounds, a depth of feelings, and an artist’s sensitivity that by the time I met him, when he was old and only a few years from passing, he openly expressed.

My profile of Bryant was originally written for the New Horizons and then when I was commissioned to write a series on Omaha’s Black Sports Legends entitled, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, I incorporated this piece into that collection. You can read several more of my stories from that series on this blog, including profiles of Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, and Johnny Rodgers.

Charles Bryant at UNL

Soul on Ice – Man on Fire: The Charles Bryant Story (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons and The Reader (www.thereader.com)

“I am a Lonely Man, without Love…Love seems like a Fire many miles away. I can see the smoke and imagine the Heat. I travel to the Fire and when I arrive the Fire is out and all is Grey ashes…

–– “Lonely Man” by Charles Bryant, from his I’ve Been Along book of poems

Life for Charles Bryant once revolved around athletics. The Omaha native dominated on the gridiron and mat for Omaha South High and the University of Nebraska before entering education and carving out a top prep coaching career. Now a robust 70, the still formidable Bryant has lately reinvented himself as an artist, painting and sculpting with the same passion that once stoked his competitive fire.

Bryant has long been a restless sort searching for a means of self-expression. As a young man he was always doing something with his hands, whether shining shoes or lugging ice or drawing things or crafting woodwork or swinging a bat or throwing a ball. A self-described loner then, his growing up poor and black in white south Omaha only made him feel more apart. Too often, he said, people made him feel unwelcome.

“They considered themselves better than I. The pain and resentment are still there.” Too often his own ornery nature estranged him from others. “I didn’t fit in anywhere. Nobody wanted to be around me because I was so volatile, so disruptive, so feisty. I was independent. Headstrong. I never followed convention. If I would have known that then, I would have been an artist all along,” he said from the north Omaha home he shares with his wife of nearly hald-a-century, Mollie.

Athletics provided a release for all the turbulence inside him and other poor kids. “I think athletics was a relief from the pressures we felt,” he said. He made the south side’s playing fields and gymnasiums his personal proving ground and emotional outlet. His ferocious play at guard and linebacker demanded respect.

“I was tenacious. I was mean. Tough as nails. Pain was nothing. If you hit me I was going to hit you back. When you played across from me you had to play the whole game. It was like war to me every day I went out there. I was just a fierce competitor. I guess it came from the fact that I felt on a football field I was finally equal. You couldn’t hide from me out there.”

Even as a youth he was always a little faster, a little tougher, a little stronger than his schoolmates. He played whatever sport was in season. While only a teen he organized and coached young neighborhood kids. Even then he was made a prisoner of color when, at 14, he was barred from coaching in York, Neb., where the all-white midget-level baseball team he’d led to the playoffs was competing.

Still, he did not let obstacles like racism stand in his way. “Whatever it took for me to do something, I did it. I hung in there. I have never quit anything in my life. I have a force behind me.”

Bryant’s drive to succeed helped him excel in football and wrestling. He also competed in prep baseball and track. Once he came under the tutelage of South High coach Conrad “Corney” Collin, he set his sights on playing for NU. He had followed the stellar career of past South High football star Tom Novak — “The toughest guy I’ve seen on a football field.” — already a Husker legend by the time Bryant came along. But after earning 1950 all-state football honors his senior year, Bryant was disappointed to find no colleges recruiting him. In that pre-Civil Rights era athletic programs at NU, like those at many other schools, were not integrated. Scholarships were reserved for whites. Other than Tom Carodine of Boys Town, who arrived shortly before Bryant but was later kicked off the team, Bryant was the first African-American ballplayer there since 1913.

No matter, Bryant walked-on at the urging of Collin, a dandy of a disciplinarian whom Bryant said “played an important role in my life.” It happened this way: Upon graduating from South two of Bryant’s white teammates were offered scholarships, but not him; then Bryant followed his coach’s advice to “go with those guys down to Lincoln.’” Bryant did. It took guts. Here was a lone black kid walking up to crusty head coach Bill Glassford and his all-white squad and telling them he was going to play, like it or not. He vowed to return and earn his spot on the team. He kept the promise, too.

“I went back home and made enough money to pay my own way. I knew the reason they didn’t want me to play was because I was black, but that didn’t bother me because Corney Collin sent me there to play football and there was nothing in the world that was going to stop me.”

Collin had stood by him before, like the time when the Packers baseball team arrived by bus for a game in Hastings and the locals informed the big city visitors that Bryant, the lone black on the team, was barred from playing. “Coach said, ‘If he can’t play, we won’t be here,’ and we all got on the bus and left. He didn’t say a word to me, but he put himself on the line for me.”

Bryant had few other allies in his corner. But those there were he fondly recalls as “my heroes.” In general though blacks were discouraged, ignored, condescended. They were expected to fail or settle for less. For example, when Bryant told people of his plans to play ball at NU, he was met with cold incredulity or doubt.

“One guy I graduated with said, ‘I’ll see you in six weeks when you flunk out.’ A black guy I knew said, ‘Why don’t you stay here and work in the packing houses?’ All that just made me want to prove myself more to them, and to me. I was really focused. My attitude was, ‘I’m going to make it, so the hell with you.’”

Bryant brought this hard-shell attitude with him to Lincoln and used it as a shield to weather the rough spots, like the death of his mother when he was a senior, and as a buffer against the prejudice he encountered there, like the racial slurs slung his way or the times he had to stay apart from the team on road trips.

As one of only a few blacks on campus, every day posed a challenge. He felt “constantly tested.” On the field he could at least let off steam and “bang somebody” who got out of line. There was another facet to him though. One he rarely shared with anyone but those closest to him. It was a creative, perceptive side that saw him write poetry (he placed in a university poetry contest), “make beautiful, intricate designs in wood” and “earn As in anthropolgy.”

Bryant’s days at NU got a little easier when two black teammates joined him his sophomore year (when he was finally granted the scholarship he’d been denied.). Still, he only made it with the help of his faith and the support of friends, among them teammate Max Kitzelman (“Max saved me. He made sure nobody bothered me.”) professor of anthropology Dr. John Champe (“He took care of me for four years.”) former NU trainers Paul Schneider and George Sullivan (who once sewed 22 stitches in a split lip Bryant suffered when hit in the chops against Minnesota), and sports information director emeritus Don Bryant.

“I always had an angel there to take care of me. I guess they realized the stranger in me.”

Charles Bryant’s perseverance paid off when, as a senior, he was named All-Big Seven and honorable mention All-American in football and all-league in wrestling (He was inducted in the NU Football Hall of Fame in 1987.). He also became the first Bryant (the family is sixth generation Nebraskan) to graduate from college when he earned a bachelor’s degree in education in 1955.

He gave pro football a try with the Green Bay Packers, lasting until the final cut (Years later he gave the game a last hurrah as a lineman with the semi-pro Omaha Mustangs). Back home, he applied for teaching-coaching positions with OPS but was stonewalled. To support he and Mollie — they met at the storied Dreamland Ballroom on North 24th Street and married three months later — he took a job at Brandeis Department Store, becoming its first black male salesperson.

After working as a sub with the Council Bluffs Public Schools he was hired full-time in 1961, spending the bulk of his Iowa career at Thomas Jefferson High School. At T.J. he built a powerhouse wrestling program, with his teams regularly whipping Metro Conference squads.

In the 1970s OPS finally hired him, first as assistant principal at Benson High, then as assistant principal and athletic director at Bryan, and later as a student personnel assistant (“one of the best jobs I’ve ever had”) in the TAC Building. Someone who has long known and admired Bryant is University of Nebraska at Omaha wrestling Head Coach Mike Denney, who coached for and against him at Bryan.

Said Denney, “He’s from the old school. A tough, hard-nosed straight shooter. He also has a very sensitive, caring side. I’ve always respected how he’s developed all aspects of himself. Writing. Reading widely. Making art. Going from coaching and teaching into administration. He’s a man of real class and dignity.”

Bryant found a new mode of expression as a stern but loving father — he and Mollie raised five children — and as a no-nonsense coach and educator. Although officially retired, he still works as an OPS substitute teacher. What excites him about working with youth?

“The ability to, one-on-one, aid and assist a kid in charting his or her own course of action. To give him or her the path to what it takes to be a good man or woman. My great hope is I can make a change in the life of every kid I touch. I try to give kids hope and let them see the greatness in them. It fascinates me what you can to do mold kids. It’s like working in clay.”

Since taking up art 10 years ago, he has found the newest, perhaps the strongest medium for his voice. He works in a variety of media, often rendering compelling faces in bold strokes and vibrant colors, but it is sculpture that has most captured his imagination.

“When I’m working in clay I can feel the blessings of Jesus Christ in my hands. I can sit down in my basement and just get lost in the work.”

Recently, he sold his bronze bust of a buffalo soldier for $5,000. Local artist Les Bruning, whose foundry fired the piece, said of his work, “He has a good eye and a good hand. He has a mature style and a real feel for geometric preciseness in his work. I think he’s doing a great job. I’d like to see more from him.”

Bryant has brought his talent and enthusiasm for art to his work with youths. A few summers ago he assisted a group of kids painting murals at Sacred Heart Catholic Church. He directs a weekly art class at Clair Memorial United Methodist Church, where he worships and teaches Sunday School.

Much of Bryant’s art, including a book of poems he published in the ‘70s, deals with the black experience. He explores the pain and pride of his people, he said, because “black people need black identification. This kind of art is really a foundation for our ego. Every time we go out in the world we have to prove ourselves. Nobody knows what we’ve been through. Few know the contributions we’ve made. I guess I’m trying to make sure our legacy endures. Every time I give one of my pieces of art to kids I work with their eyes just light up.”

These days Bryant is devoting most of his time to his ailing wife, Mollie, the only person who’s really ever understood him. He can’t stand the thought of losing her and being alone again.

“But I shall not give in to loneliness. One day I shall reach my True Love and My fire shall burn with the Feeling of Love.”

–– from his poem “Lonely Man”

Related articles

- A Family Thing, Bryant-Fisher Family Reunion (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Green Bay Packers All-Pro Running Back Ahman Green Channels Comic Book Hero Batman and Gridiron Icons Walter Payton and Bo Jackson on the Field (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Omaha Lit Fest: “People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like”

Seven years ago the quirky (downtown) Omaha Lit Fest began, and as an arts-culture writer here I’ve found myself writing about it and some of its guest authors and their work pretty much every year. The following piece for The Reader (www.thereader.com) is a preview of the 2011 edition, whose guests include Terese Svoboda (Bohemian Girl) and Rachel Shukert (Everything is Going to be Fine). The festival’s founder and director, novelist Timothy Schaffert (The Coffins of Little Hope), is the subject, along with the event, of several articles on this blog. If you’re a local and you have never done the fest, then shame on you. Make sure you do this time around. If you happen to be visiting during its Oct. 13-15 run then make sure you check it out and experience a sophisticated side of Omaha that may be new to you. Sure, this kind of thing is not for everyone, but it’s a fortifying intellectual exercise you’ll be glad you did. Besides, it’s free, most of it anyway. This year is a bit different in that I’m serving on a panel of local arts-culture writers discussing our role in framing Omaha’s arts scene, including its artists and art oganizations.

Apert from the Lit Fest, this blog also contains many more articles on authors and books of all kinds. Go to the books category on the right and discover the many writers and works I’ve been fortunate enough to report on and read.

Omaha Lit Fest: “People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In his capsule of the 2011 (downtown) Omaha Lit Fest founder-director and novelist Timothy Schaffert draws a parallel with The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Specifically, to the humbug Wizard’s endowing the Tin Woodman with a heart made of silk and sawdust, with some soldering necessary to better make the heart take hold.

As Schaffert (The Coffins of Little Hope) suggests, the writer’s process is part alchemy, part major surgery, part inspiration, part wishful thinking in giving heart to words and ideas and eliciting readers’ trust and imagination. Thus, he writes, this seventh edition of the Lit Fest focuses on “the heart and mechanics of writing” as authors “lift the corner of the curtain on their methods and processes.”

Consistent with its eclectic tradition of presenting whatever spills out of Schaffert’s Wizard’s mind, the Fest includes panels, exhibitions, salons and workshops that feature the musings and workings of poets, fiction writers, journalists and artists.

Guest authors include native Nebraskans turned New Yorkers Terese Svoboda, whose new novel Bohemian Girl has received ecstatic reviews, and Rachel Shukert, now at work on two new novels, a television series she’s adapting from her memoir Everything is Going to be Great and a screenplay.

The free Fest runs Oct. 13-15 at the W. Dale Clark Library, 215 South 15th St. and at Kaneko, 1111 Jones St. “Litnings” unfold the rest of the month at other venues.

With Lit Fest such an intimate Being Timothy Schaffert experience, it’s hard gauging it’s place in the Omaha cultural fabric.

“What we do is fairly esoteric. I’m always meeting people who have never heard of it and I definitely wouldn’t be able to handle it if it was as large as some other cities’ lit fests, which draw hundreds and hundreds of people. So I like it the way it is. I’ve often thought I misnamed it, that I probably shouldn’t have called it a festival, but called it a salon or something. So it’s a fraud basically,” Schaffert says with an ironic lilt in his laugh.

He quotes Abraham Lincoln to sum up the event’s cognoscenti appeal: “People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like.”

Mention how the programs feel peculiarly personal to him, Schaffert says, “It doesn’t always come together perfectly, but, yeah, I definitely try to shape it.” Ask if he pulls the strings behind the curtain, he says, “In the past it’s usually been just me but this year I’ve worked some with Amy Mather, the head of adult services at the W. Dale Clark Library. They’re cosponsors.”

That Schaffert pretty much conceptualizes the show himself is a function of limited resources and, therefore, a necessity-is-the-mother-of-invention approach. “We have virtually no budget. It actually strangely makes it even more interesting I think when you’re trying to do it on the cheap.” Of this labor of love, he adds,. “It is fun.”

Then, too, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln English instructor, Prairie Schooner web-contributing editor and Nebraska Summer Writer’s Conference director is well-plugged into writing circles. He’s also published by premier houses Unbridled Books and, soon, Penguin, which just bought his in-progress The Swan Gondola, a tragic love story set at Omaha’s 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition.

From the start, he’s viewed the Fest as a means of framing the local lit culture. Shukert appreciates the effort. She doesn’t recall a visible Omaha lit scene when she lived here, saying, “I actually think probably there was but it just hadn’t been identified yet, and once somebody is like, Wait, this is going on, then it’s like all these writers and book people can kind of like out themselves as part of a literary community and come together. I think that was an incredibly smart move on Timothy’s part to recognize there was this incipient thing that just needed someone to name it.”

She says, “I feel a nice balance he’s managed to strike is finding local people and native Omahans who have national profiles and people who have no connection to Omaha at all except this is a cool event they want to be at. It’s a nice mix, and that’s important.”

Schaffert notes the 2011 edition is heavy with native Nebraska authors “because so many local writers or writers with local ties have had new books come out in the last year and a half or so, so this is an opportunity to have them talk about their new works.” Those local scribes range from: Omaha World-Herald political cartoonist Jeffrey Koterba, whose memoir Inklings made a big splash, to OWH lifestyles columnist Rainbow Rowell, whose debut novel Attachments did well, to Mary Helen Stefaniak (The Califfs of Baghdad, Georgia) and David Philip Mullins (Greetings from Below).

Of the Nebraska ex-pats participants, perhaps the one with the largest national profile is Ogallala-born and raised Terese Svoboda, a poet and novelist praised for her exquisite use of language. In Bohemian Girl, she describes a hard-scrabble girl-to-womanhood emancipation journey on the early Nebraska frontier. The work contains overtones of True Grit, Huckleberry Finn and Willa Cather.

Peaking her intrigue were “pictures of 30 year-old pioneer women who looked like they were 70…and then they wrote diaries that were extremely cheerful — I just wondered what was going on there.” Charged by the feminist and civil rights movements’ challenge to let muted voices be heard, she says “in some ways Bohemian Girl was setting off to let those voices free or at least to talk about them.”

In some ways her book is a meditation on bohemianism as ethnicity, state of mind and lifestyle. “I was born in Ogallala as the oldest of nine children. My Bohemian father is a rancher, farmer and a lawyer, and my Irish mother painted. They read great books together and recited poetry they had memorized in high school in Neb. And I wore pointy red glasses in high school because I was the bohemian girl.”

Her proto-feminist heroine enlists Bohemian pluck and bohemian invention to survive hardships and seize opportunities in finding prosperity, if not contentment.

Terese Svoboda

Svoboda says “the picaresque story” sets out “to correct Willa Cather about Bohemians — they were more interesting than she portrayed them, and that’s dangerous territory I know to say, but I felt Cather was not a Nebraskan, she was from Virginia, and she looked at the people who settled there with that kind of eye. In fact, her point of view is always a little bit distant. So I wanted to get right inside a girl and show how hard it was and how the opportunities and the choices she makes are her own.”

As a reference point Svoboda drew on a creative pilgrimage she made to Sudan, Africa and to her own prairie growing up.

“I used the experience of my year spent in the Sudan for what it would be like to be a girl out in the bare prairie — blending that with my own experience in western Neb., the Sand Hills especially.”

Those lived vignettes, she posits, “contributed to the authenticity.”

Schaffert is among Svoboda’s many admirers.

“She brings a poet’s rich sense of language to her fiction. I feel like that’s what makes her novels and her short stories so exciting — they’re not weighty with language, they’re not inaccessible, but you do have to read them carefully to fully enjoy them. I think her new novel Bohemian Girl has eloquence. It’s eclectic, it’s whimsical, unsettling, and it has its heart in Nebraska and Nebraska history.”

The depth and precision of Svoboda’s language come from endless reworking.

“I do work hard at that. I am very attentive to each word. I am not a transparent writer — that is to say writing prose where the words are just something the reader falls into a dream for the characters and the plot. Because my background is a poet, I see each word as a possibility and each narrative exchange as a possibility, so nobody wastes any time going in and out of rooms or talking about the weather.

“I really respect the reader and their intelligence and hope that they appreciate I do that. I really think every word they read should be worthy of them.”

She didn’t plan on being a novelist, but a life-changing odyssey changed all that.

“I would have been perfectly happy to be a poet forever…but when I went off to Africa I had such a profound and emotionally difficult experience of being in practically another planet, I wrote a novel, Cannibal, about it. I felt I had to write prose.”

She only came to finish the novel, however, after struggling through 30 full length drafts over several years. A course taught by then-enfant terrible editor Gordon Lish awoke her to a new way into the story.

“At the end of that you learned that writing was the most important thing in your life and the words were a building block of the sentence…And it didn’t matter what you wrote — the minute you thought of someone else reading it or started weighing it against somebody else you might as well toss it away, so I tossed it away, I started all over again, although I had to still send it out 13 times before it finally did get published, and that excruciating experience brought me to the world of prose.

“I’m not one of those people that sits down and all the words come out right. Each of my novels seems to take 10 years from the beginning to the end, overlapping of course. I continue to go back to them. But some of my poems take that long, too.”

She’ll talk shop with Timothy Schaffert at An Evening with Terese Svoboda on Oct. 15 at 7 p.m. at Kaneko.

Shukert, along with fellow writers, will share thoughts about craft during a 2-5 p.m. salon at the library earlier that day.

“I’m happy to talk about process but I always do it with the caveat that I don’t expect it to actually be helpful to anybody. It’s not a formula,” says Shukert. “Very often people ask questions like, How do you do it? and the implication is, How can I do it? or How do I get a book published? or How do I finish my novel? And that’s the one thing nobody else can answer for you. Very early in your career it can be helpful to hear the way other people did it because you need to keep telling yourself it’s possible, it can be done.”

While Svoboda insists her process is not appreciably different writing novels than it is poems, Shukert says, “I find my process alters depending on what I’m working on. Like my process writing a book is very different than my process writing a play or a screenplay. My process writing fiction — now that I’m working on my first novel — is very different than the memoir process. It’s a lot slower. Switching from first person to third person has been interesting, especially as pertains to point of view.

“There are things that get easier and then things that get harder. I feel I have a much easier time, for example, just sitting down and writing and not being intimidated by the sheer scope of it. It’s a much more practiced muscle. But that doesn’t mean what I write right away is better.”

Rachel Shukert

Writing is one thing. Getting published, another. Conventional publishing is still highly competitive. Self-publishing though is within reach of anyone with a computer, tablet or smart phone. This democratization is the subject of a 11 a.m. Oct. 15 panel at the library and an Oct. 22-23 workshop at the Omaha Creative Institute.

Shukert says, “I feel like there’s more of an appetite to write than ever before but is there the same appetite to read? I feel, too, it’s about being able to cut through the noise. It’s one thing to publish your work, it’s another thing if anyone actually reads it or is able to find it.”

Yes, she says, self-publishing “does get voices heard that otherwise would not have been, but,” she adds. “there was a sort of curatorial process that I think is slowly falling apart. You want to know that what you’re reading is valuable. In a weird way I feel that attitude that anybody can be published, that I can publish this myself, oddly devalues the work of every writer. There’s still gotta be a way you can separate things. When there’s too much, there’s sort of too much.”

In the traditional publishing world, says Svoboda, an opposite trend finds “many more gatekeepers then when I started, or the gate has gotten a lot smaller, and so there are manuscripts in the world that deserve to get published that aren’t getting published. But I don’t know there would be that many more” (deserving manuscripts) now that the number of self-proclaimed writers has increased.

“The ability to publish so easily is probably a bad thing,” she adds. “Many people have stories and they are interesting stories but not everybody can write literature.”

Schaffert embraces this come one, come all new age.

“I think it’s a really great time to be a writer and I don’t think it’s yet necessarily interfering with the pursuit of the reader to find quality content. The stuff that the world responds to the world will still respond to and still find their way to. There are more ways to respond to the work you’re reading and more avenues to find new work thats more specific to your tastes. I mean, I think this is all great.

“If you’re sort of entrepreneurial by nature you can even venture to do for yourself what a conventional publisher might do, which is to promote your work, try to get attention for it…Even writers going through the old fashioned methods of publishing have added opportunities because you still have to promote your work. The world is your oyster.”

A 5 p.m. panel Oct. 13 at the library, moderated by blogger Sally Brown Deskins, will consider “the role criticism, arts profiles and cultural articles play in presenting artists and arts organizations to the community and to the world,” says Schaffert. “It seems to me every serious city needs serious coverage of what it’s doing. I think it’s integral there be writers we associate with coverage of the arts scene.”

Book design, objects in literature and fashion in literature are other themes explored in panels or exhibits.

An opening night reception is set for 6:30-9:30 at the library, Enjoy cupcakes, champagne and a pair of art exhibits.

For the complete Lit Fest schedule, visit omahalitfest.com.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.wordpress.com

Related articles

- Off the Shelf: Bohemian Girl by Terese Svoboda (nebraskapress.typepad.com)

- Getting to know: Terese Svoboda. (wewhoareabouttodie.com)

- Being Jack Moskovitz, Grizzled Former Civil Servant and DJ, Now Actor and Fiction Author, Still Waiting to be Discovered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Author Rachel Shukert, A Nice Jewish Girl Gone Wild and Other Regrettable Stories (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Summer Reading: The Coffins of Little Hope by Timothy Schaffert (homebetweenpages.com)

- When Safe Isn’t Safe at All, Author Sean Doolittle Spins a Home Security Cautionary Tale (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Rachel Shukert’s Anything But a Travel Agent’s Recommended Guide to a European Grand Tour (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

“Portals” opens new dimensions in performance art – Multimedia concert comes home for Midwest premiere

Back in April I wrote a piece that appeared on this blog about a multimedia concert piece then in-progress called Portals. Omaha’s creative nurturing place, KANEKO, served as producer and its bow truss live event space is where some of the project’s principal filming was done. My story then – “Open Minds, Portals Explore Human Longing in the Digital Age” – quoted creative director and virtuoso violinist Tim Fain and co-lead filmmaker Kate Hackett explaining the concept behind the project. In addition to his playing and her visuals Portals features the poetry of Leonard Cohen, the music of Philip Glass and a bevy of other top composers, and the choreography of Benjamin Millepied. A preview that month gave me and a few hundred others glimpses of the work. It was stunning and definitely whet the appetite for more, certainly for seeing the finished project. The completed Portals had its world premiere in New York City in late September and last night (Oct. 5) the piece made its Midwest premiere in Omaha. The multimedia concert mostly delivered on its promise to explore the open spaces between and betwixt the real and virtual worlds. My two more recent stories below appeared just in advance of the Omaha performance and tried to further frame what Portals intended. Something I meant to include in my print Portals stories were some notes about the violin Fain performs on, but I offer it here now for your information.

“I often find people are very interested in the violin I play,” he says. “After concerts I get a lot of people asking. It’s a beautiful old Italian violin that’s on loan to me right now. It was made in 1717 by Francesco Gobetti, one of the real Italian masters. It’s on loan to me through an organization called the Stradivarius Society of Chicago. My patrons, who live in Buffalo, Clement and Karen Arrisson, are part of this network of people who think it’s cool to loan their zillion dollar instruments to players.

“While I do consider myself the biggest winner, everyboy wins because the instruments, if they’re not played on, they deteriorate a lot quicker. I’ve had the Gobetti for almost four years now. You really get to know the instrument in an entirely different way. It’s almost like I have the feeling I’m communing with another soul. Makers were able to invest a part of themselves in the instruments they made. It’s very mysterious – I don’t claim to understand it really.”

I can attest that Fain is one with his instrument and whatever spirit it possesses.

Portals opens new dimensions in performance art – Multimedia concert comes ome for Midwest premiere

©by Leo Adam Biga

Published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

An April program at KANEKO offered a preview of the mixed media work, Portals. Virtuoso violinist Tim Fain and filmmaker Kate Hackett provided tantalizing glimpses of a phantasmagoric experiment in performance and social media. KANEKO director Hal France and the Portals creative team also laid the groundwork for a residency in the collaborative arts.

There’s great anticipation for the finished piece making its Midwest premiere here. The two shows follow on the heels of the work’s September 25th world premiere in New York, where Portals was well-received. It’s hard not being curious about a work that integrates multiple mediums and styles into a seamless experience. There’s music by acclaimed composers Philip Glass, Aaron Jay Kernis, Nico Muhly, Kevin Puts, Lev Zhurbin and William Bolcom. Images are by Hackett and Benjamin Milliepied, whose choreography is also featured. There are the words of Leonard Cohen. And the musicianship of Fain and pianist Nicholas Britell.

So, what is Portals exactly?

Think of it as a performance piece bridging the divide between real and virtual, live and digital, all expressed through a merging of set design, lighting, music, video, dance, literature, spoken word and the Web. It’s about finding new portals of communication and connection between old and new forms. New York Times reviewer Allan Kozinn felt Fain “succeeded admirably” in finding “new ways to frame the music.”

Where does the social media aspect come in?

During the concert Fain will perform live on stage, as will his accompanist, but he will also interact with several performers, even a virtual version of himself, seen via rear-projected videos that give the impression of social networking exchanges. It’s meant to be an immersive, sensory, boundaries-breaking, genre-bending experience.

KANEKO, along with Silicon Prairie News and local universities, is hosting a Live Social Media event that seeks “experimenters” to participate in the Portals experience and offer feedback. To sign-up, visit http://www.siliconprairienews.com.

What about the team residency?

Portals principles will conduct free previews, lectures, master classes and conversations in Omaha and Lincoln. Students from local universities are encouraged to attend. To register, visit thekaneko.org/portals/education.

‘Portals’ Unveiled

Last month a New York City audience embraced the world premiere of the multimedia concert piece, Portals, and now the work’s come back to its other home, Omaha’s KANEKO, for performances October 5-6.

As creative director, acclaimed violinist Tim Fain has integrated music by Philip Glass and other noted composers, including Pulitzer Prize winners Aaron Jay Kernis and William Bolcom, with the words of Leonard Cohen, choreography by Benjamin Millepied, visuals by Kate Hackett, and his own virtuosic playing.

KANEKO, whose Open Space for Your Mind mantra invites projects to explore creative boundaries, is a co-producer. The 1111 Jones Street venue’s bow truss space is where Hackett, a Los Angeles-based filmmaker known for multimedia work, did some principal taping-filming. KANEKO is also where Hackett, Fain and pianist Nicholas Britell presented a preview of Portals last April.

“Portals is really a celebration of music that epitomizes what I love and what I think is worth sharing, and the presentation of that music is meant to push what’s possible in a performance and bring it into the digital age in a way that does justice to the music and also to our times,” says Fain.

At its core is a new seven-movement partita Glass composed for Fain.

“This piece has as its inspiration one little moment from Philip’s (song-cycle) Book of Longing, where the whole stage went black except for a spotlight that came down on me as I launched into a two-minute, really intense piece for unaccompanied violin.”

Fain also wanted to “recreate that feeling as a performer where you walk into a hall before the performance and nobody else is around. It’s just you and the stage … The lighting is golden and beautiful. There’s this almost seductive feeling of privacy, intimacy and communing with the music. All leading up to sharing it with the audience …”

Portals is a “fluid collaboration between music and film” Hackett says. “There’s going to be sort of three prongs to this evening, three different feels, all of which come together. All of the pieces are going to be interconnected by spoken-word text. The films accompanying those pieces will have a Webcam feel as they show a day-in-the-life sense of the different collaborators going about their daily business. We’ll get the feeling they’re speaking to each other via Webcam and Skype.”

“The second prong will have a much more produced feel, where Tim will be on stage playing and projected behind him will be films of a violinist and a pianist playing,” she says. “The idea is these players have come together in the Webcam-Skype world and now they’ve created a concert together that only exists in their head space. The third prong is the dance films Benjamin created in New York to accompany the Philip Glass piece. Those films additionally feel like a collaboration that happens through these different portals.”

“The whole idea behind Portals,” says Fain, “is really to … make the multimedia and film element not only something cool and exciting to look at but also a very necessary part of the experience. Musicians and dancers and the audience will all in a sense be signing on to collaborate in an artistic expression through the digital medium.”

At certain intervals, Fain seemingly becomes part of the images projected around him. He hopes this melange creates “something meaningful and beautiful and human.”

This convergence of forms and ideas is what KANEKO seeks, says executive director Hal France. “This as a collaborative project is perfect for us. It’s cross disciplinary. It has a purpose.”

The outside-the-box merging of live and virtual performance creates a new kind of immersion-ensemble experience, he says, sure to provoke dialogue. That’s the point.

For tickets to the 7:30 p.m. shows call 402-341-3800 or visit http://www.thekaneko.org.

Related articles

- Music Review: ‘Portals,’ From Tim Fain, at Symphony Space (nytimes.com)

- New music for new virtuosos (the-unmutual.blogspot.com)

- From the Archives: Opera Comes Alive Behind the Scenes at Opera Omaha Staging of Donizetti’s ‘Maria Padilla’ Starring Rene Fleming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- ‘Portals’ Opens New Dimensions in Performance Art – Multimedia Concert Comes Home for Midwest Premiere (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jeff Slobotski and Silicon Prairie News Create a Niche by Charting Innovation (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Lit Fest: ‘People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Writers Joy Castro and Amelia Maria de la Luz Montes explore being women of color who go from poverty to privilege

Joy Castro

Writers Joy Castro and Amelia Maria de la Luz Montes explore being women of color who go from poverty to privilege

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in El Perico

Two University of Nebraska-Lincoln scholars and authors, one Mexican-American, the other Cuban-American, contributed pieces to a new anthology of essays by women, An Angle of Vision (University of Michigan Press).

The book derives its title from the essay by Joy Castro, an associate professor in the Department of English at UNL and the author of a 2005 memoir, The Truth Book (Arcade Press). Her colleague, Amelia Maria de la Luz Montes, is an associate professor of English and Ethnic Studies and director of UNL’s Institute for Ethnic Studies. Montes penned the essay “Queen for a Day.” She’s also edited a new edition of a 19th century novel written by a Mexican-American woman. The book, Who Would Have Thought It? (Penguin Classics), is a satiric look at New England through the eyes of a teenage Latina.

All the authors in Angle of Vision hail from poor, working-class backgrounds, a counterpoint to the privileged lives they lead today in academia and publishing. As Castro said, “when you see from a different angle, you notice different things.” The authors use the past and present as a prism for examining class, gender, ethnicity and identity. Each navigates realities that come with their own expectations and assumptions, making these women ever mindful of the borders they cross.

Montes and Castro are intentional about not diminishing their roots but celebrating them in the various worlds they traverse — higher education, literature and family.

Said Castro, “Getting out of poverty, through effort and luck, has never felt like permission to say, ‘Whew! Now I can kick back and enjoy myself.’ Acknowledging my background means that much of my work, whether it’s the short stories and essays I write or the working-class women’s literature I teach, focuses on bringing attention to economic injustice as well as racism and sexism.

“Latinidad is hugely important to me, and it is definitely connected with class and gender. Because of the great wave of well-to-do Cuban immigrants who came to the USA when Fidel Castro took power, many people assume all Cuban-Americans are wealthy, right-leaning, and so on. That wasn’t the case for my family, who had been in Key West since the 1800s and were working-class and lefty-liberal. In a forthcoming essay, ‘Island of Bones,’ I explore that little-known history.”

Castro embraces the many dimensions of her ethnicity.

“Mostly, my Latinidad has been a source of strength, comfort and great beauty throughout my life. It means food, music, love, literature, home. I’m proud to belong to a rich, strong, vibrant culture, and I love teaching my students about the varied accomplishments and ongoing struggles of our people.”

Being a person of color in America though means confronting some hard things. She said her father’s experience with racism and police abuse caused him to assimilate at any price. “For my brother Tony and me our father’s life is a cautionary tale about the costs of shame and of trying to erase who you are.”

By contrast, she said, “We raised our children to be proud of their heritage. My son is fluent in Spanish, which my father refused to speak at home.”

Complicating Castro’s journey has been the aftermath of the abusive childhood she endured, a facet of her past she long sought to suppress.

The past was also obscured in the Montes home. Her Mexican immigrant mother endured a bad first marriage. Amelia didn’t find out about her struggles until age 25. It took another 25 years before she felt mature enough to write about it.

“I do think the experience of coming from a working class family and being a minority we have certain pressures in society,” said Montes. “In order to be successful or in order to assimilate as my mother worked hard to do you had to not let on the oppressions infringing on your own spaces. You processed them in other ways, but outside of the house or outside your own private sphere you made sure you’re presenting a suitable facade.

“It is a survival mechanism. At the same time one must be careful because if you let it encompass you, then the facade overtakes you and you lose who you are.”

Being a lesbian on top of being a Latina presents its own challenges. Montes said in fundamentalist Christian or conservative Catholic Latino communities her sexual identity poses a problem. She’s weary of being categorized but said, “Labels are always necessary when there’s inequality. If there wasn’t inequality we wouldn’t need these labels, but we need them in order to be present and to have people understand. I always tell my students that just because I’m Latina does not mean I represent all Latinas or all Latinos, and that goes for lesbians as well.”

For Montes, with every “border fence” crossed there’s reward and price.

“There’s success, there’s achievement,” she said, “but there’s also loss because once you cross a fence that means you’re leaving something behind. There is a celebration in knowing my mother is very happy I have succeeded as a first generation Latina. I will never forget where my mother came from and who she is, even the sufferings and difficult times she journeyed through.”

Montes is now writing a memoir to reconcile her own self. “In looking back I’m processing what happened in order to better understand it and to also claim where I come from, so that I don’t hide I come from a working class background, or I don’t only speak English, but make sure I continue to practice my Spanish.”

Castro found writing her memoir liberated her from the veil of secrecy she wore.

“Having my story out there in the world helped me let go of the impulse to hide the truth of my life. I’m still pretty shy, perhaps by nature, but disclosing my story helped me let go of shame. And I was hired at UNL ‘because’ of my book, so everyone knew in advance exactly what kind of person they were getting. What a relief. It’s easier to live in the world when you can be free and open about who you are and where you come from. You can breathe. You’re not anxious. You’re not trying to perform something you’re not.”

She said the project helped her appreciate just how far she’s come.

“Laying it all out in book form, I came to respect the difficulty of what I’d had to navigate. In some ways, my journey was as challenging as moving from one country, one culture, to another. All the new customs have to be learned. Also, another great benefit was that writing it down…shaping it into a coherent narrative for readers helped me gain objectivity and distance on the material. It became simply content in a book, rather than a terrible weight I carried around inside me.”

Castro said her experience made her sensitive to what people endure.

“We never know what other people are carrying. In fact, sometimes they’re going to great lengths to conceal their burdens, to pass as normal and okay. Remembering that simple truth can help us be gentle with each other.”

Castro and Montes know the emotional weight women bear in having to be many different things to many different individuals, often at the cost of denying themselves . Each writer applies a feminist perspective to women’s roles.

“I’m glad to say things are changing, but despite many advances in women’s rights, Latinas are often pushed, even today, to put men first, to have babies, to love the church without question, to be submissive and obedient to authority,” said Castro.” “It took me a long time to crawl out from under the expectations I was raised with.”

“It seems to me in the early 20th century there was a big push, a big advancement, then we fell off the mountain in the ’40s, ’50s, 60s, then came back in the ’70s and ’80s. and right now I think we’re retreating backwards again,” said Montes. “The vast majority of people out of work and homeless are women and children. I’m heartsick about what’s going on in Calif. and other parts of the country concerning education and how more and more the doors of education are closing to working class people and to out-of-work minorities because of the hikes in tuition, et cetera.”

Montes concedes there’s “a lot of advances, too,” but added, “I’m always wanting us to keep going forward.”

Castro feels obligated to use her odyssey as a tool of enlightenment and empowerment. “I’m lucky and grateful to be someone who has made it out of poverty, abuse and voicelessness, who has made it to a position where I have a voice. It’s an important responsibility. My own published fiction, nonfiction and poetry all concern issues of poverty. I make a point of teaching literature by poor people in the university classroom, where most of my students are middle-class.”

She’s taught free classes for the disadvantaged at public libraries and through Clemente College. For two years now she’s mentored a young Latina-Lakota girl born in poverty. “In choosing to mentor, I wanted to keep a strong, personal, meaningful connection to what it means to be young and female and poor. I wanted to be the kind of adult friend I wished for when I was a girl,” said Castro.

Both authors were delighted to be represented in Angle of Vision. “It was a surprise and a great compliment,” said Castro. “It’s such a good book with so many wonderful writers.” “The resilience and strength of these writers in navigating through difficult childhoods really comes out. It’s amazing,” said Montes. Both have high praise for editor Lorraine Lopez. The fact that a pair of UNL friends and colleagues ended up being published together makes it all the sweeter.

To find more works by them visit their web sites: joycastro.com and ameliamontes.com.

Letting 1,000 Flowers Bloom: The Black Scholar’s Robert Chrisman Looks Back at a Life in the Maelstrom

Six years ago a formidable figure in arts and letters, Robert Chrisman, chaired the Department of Black Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The mere fact he was heading up this department was symbolic and surprising. Squarely in the vanguard of the modern black intelligentsia scene that has its base on the coasts and in the South, yet here he was staking out ground in the Midwest. The mere fact that black studies took root at UNO, a predominantly white university in a city where outsiders are sometimes amazed to learn there is a sizable black population, is a story in itself. It neither happened overnight, nor without struggle. He came to UNO at a time when the university was on a progressive track but left after only a couple years when it became clear to him his ambitions for the academic unit would not be realized under the then administration. Since his departure the department had a number of interim chairs before new leadership in the chancellor’s office and in the College of Arts and Sciences set the stage for UNO Black Studies to hire perhaps its most dynamic chair yet, Omowale Akintunde (see my stories about Akintunde and his work as a filmmaker on this blog). But back to Chrisman. I happened to meet up with him when he was in a particularly reflective mood. The interview and resulting story happened a few years after 9/11 and a few years before Obama, just as America was going Red and retrenching from some of its liberal leanings. He has the perspective and voice of both a poet and an academic in distilling the meaning of events, trends, and attitudes. My story originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com) and was generously republished by Chrisman in The Black Scholar, the noted journal of black studies for which he serves as editor-in-chief and publisher. It was a privilege to have my story appear in a publication that has published works by Pulitzer winners and major literary figures.

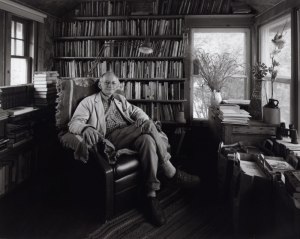

Robert Chrisman

Letting 1,000 Flowers Bloom: The Black Scholar’s Robert Chrisman Looks Back at a Life in the Maelstrom

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) and republished with permission by The Black Scholar (www.theblackscholar.org)

America was at a crossroads in the late 1960s. Using nonviolent resistance actions, the civil rights movement spurred legal changes that finally made African Americans equal citizens under the law. If not in practice. Meanwhile the rising black power movement used militant tactics and rhetoric to demand equal rights — now.

The conciliatory old guard clashed with the confrontational new order. The assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy seemed to wipe away the progress made. Anger spewed. Voices shouted. People marched. Riots erupted. Activists and intellectuals of all ideologies debated Black America’s course. Would peaceful means ever overcome racism? Or, would it take a by-any-means-necessary doctrine? What did being black in America mean and what did the new “freedom” promise?

Amid this tumult, a politically-tinged journal called The Black Scholar emerged to give expression to the diverse voices of the time. Its young co-founder and editor, Robert Chrisman, was already a leading intellectual, educator and poet. Today he’s the chair of the University of Nebraska at Omaha (UNO) Department of Black Studies. The well-connected Chrisman is on intimate terms with artists and political figures. His work appears in top scholarly-literary publications and he edits anthologies and collections. Now in its 36th year of publication, The Black Scholar is still edited by Chrisman, who contributes an introduction each issue and an occasional essay in others, and it remains a vital meditation on the black experience. Among the literati whose work has appeared in its pages are Maya Angelou and Alice Walker.

From its inception, Chrisman said, the journal’s been about uniting the intellectuals in the street. “We were aware there were a lot of street activists-intellectuals as well as academicians who had different sets of training, information and skills,” he said. “And the idea was to have a journal where they could meet. By combining the information and initiative you might have effective social programs. That was part of the goal.”

Another goal was to take on the core issues and topics impacting African Americans and thereby chart and broker the national dialogue in the black community.

“We were aware there was a tremendous national debate going on within the black community and also within the contra-white community and Third World community on the forward movement not only of black people in the United States but also globally and, for that matter, of white people. And so we felt we wanted to register the ongoing debates of the times with emphasis upon social justice, economic justice, racism and sexism.

“And then, finally, we wanted to create an interdisciplinary approach to look at black culture and European-Western culture. Because one of the traditions of the imperialist university is to create specialization and balkanization in intellectuals, rather than synthesis and synergy. We felt it would be contrary to black interests to be specialists, but instead to be generalists. And so we encouraged and supported the interdisciplinary essay. We also felt critique was important. You know, a long recitation of a batch of facts and a few timid conclusions doesn’t really advance the cause of people much. But if you can take an energetic, sinewy idea and then wrap it and weave it with information and build a persuasive argument, then you have, I think, made a contribution.”

No matter the topic or the era, the Scholar’s writing and discourse remain lively and diverse. In the ’60s, it often reflected a call for radical change. In the 1970s, there were forums on the exigencies of Black Nationalism versus Marxism. In the ’80s, a celebration of new black literary voices. In the ’90s, the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill imbroglio. The most recent editions offer rumination on the Brown versus Board of Education decision and a discussion on the state of black politics.

“From the start, we believed every contributor should have her own style,” Chrisman said. “We felt the black studies and new black power movement was yet to build its own language, its own terminology, its own style. So, we said, ‘let a thousand flowers bloom. Let’s have a lot of different styles.’”

But Chrisman makes clear not everything’s dialectically up for grabs. “Sometimes, there aren’t two sides to a question. Period. Some things are not right. Waging genocidal war is not a subject of debate.”

The Meaning of Things

In an essay refuting David Horowitz’s treatise against reparations for African Americans, Chrisman and Ernest Allen, Jr. articulate how “the legacy of slavery continues to inform institutional as well as individual behavior in the U.S. to this day.” He said the great open wound of racism won’t be healed until America confronts its shameful part in the Diaspora and the slave trade. Reparations are a start. Until things are made right, blacks are at a social-economic disadvantage that fosters a kind of psychic trauma and crisis of confidence. In the shadow of slavery, there is a struggle for development and empowerment and identity, he said.

“Blacks produce some of the most powerful culture in the U.S. and in the world. We don’t control enough of it. We don’t profit enough from it. We don’t plow back enough to nurture our children,” he said. “Part of that, I think, is an issue of consciousness. The idea that if you’re on your own as a black person, you aren’t going to make it and another black person can’t help you. That’s kind of like going up to bat with two strikes. You choke up. You get afraid. Richard Wright has a folk verse he quotes, ‘Must I shoot the white man dead to kill the nigger in his head?’ And you could turn that around to say, ‘Must I shoot the black man dead to kill the white man in his head?’ The difference is that the white man has more power (at his disposal) to deal with this black demon that’s obsessing him.”

In the eyes of Chrisman, who came of age as an artist and intellectual reading Frederick Douglass, W. E. B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Robert Hayden, James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Vladimir Lenin, Karl Marx, Che Guevara, Pablo Neruda, Mao Tse-tung and the Beat Generation, the struggle continues.

“The same conditions exist now as existed then, sadly. In 1965 the Voting Rights Act was passed precisely to protect people from the rip off of their votes that occurred in Florida in 2000 and in Ohio in 2004. Furthermore, with full cognizance, not a single U.S. senator had the courage to even support the challenge that the Congressional Black Caucus made [to the 2000 Presidential electoral process].”Raging at the system only does so much and only lasts so long. In looking at these things, one makes a distinction between anger and ideology,” he said.

“There were a number of people in the 1960s who were tremendously angry, and rightfully so. Once the anger was assuaged … then people became much much status quo. A kind of paretic example is Nikki Giovanni, who in the late ’60s was one of those murder mouth poets. ‘Nigguh can you kill. Nigguh can you kill. Nigguh can you kill a honky …’ At the end of the ’70s, she gets an Essence award on television and she sings God Bless America. On the other hand, you take a fellow like Ray Charles, who always maintained a musical resistance, which was blues. And so when Ray Charles decides to sing — ‘Oh beautiful, for spacious skies …’ — all of the irony of black persecution, black endurance, black faith in America runs through that song like a piece of iron. ‘God shed His grace on thee’ speaks then both to God’s blessing of America and to, Please, God — look out for this nation.”

Chrisman said being a minority in America doesn’t have to mean defeat or disenfranchisement. “I think we are the franchise. Black people, people with a just cause and just issues are the franchise. It’s the alienated, confused, hostile Americans that vote against their own interests [that are disenfranchised],” he said. “Frederick Douglass put it another way: ‘The man who is right is a majority.’”

Just as it did then, Chrisman’s own penetrating work coalesces a deep appreciation for African American history, sociology art and culture with a keen understanding of the contemporary black scene to create provocative essays and poems. Back when he and Nathan Hare began The Black Scholar in ’69, Chrisman was based on the west coast. It’s where he grew up, attended school, taught and helped run the nation’s first black studies department at San Francisco State College. “There was a lot of ferment, so it was a good place to be,” he said. He immersed himself in that maelstrom of ideas and causes to form his own philosophy and identity.

“The main voices were my contemporaries. A Stokley Carmichael speech or a Huey Newton rally. A Richard Wright story or a James Baldwin essay. Leaflets. Demonstrations. This was all education on the spot. I mean, they were not always in harmony with each other, but one got a tremendous education just from observing the civil rights and black power movements because, for one thing, many of the activists were very well educated and very bright and very well read,” Chrisman explained. “So you were constantly getting not only the power of their ideas and so on, but reading behind them or, sometimes, reading ahead of them. And not simply black activists, either. There was the hippy movement, the Haight Ashbury scene, the SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]. You name it.”

When he arrived at San Francisco State in 1968, he walked into a firestorm of controversy over students’ demands for a college black studies department.

“The situation was very tense in terms of continued negotiations between students and administrators for a black studies program,” Chrisman said. “Then in November of 1968, everybody went out on strike to get the black studies program. The students called the strike. Black teachers supported the strike. In January of 1969 the AFL-CIO, American Federation of Teachers, Local 1352, went out also. I was active in the strike all that time as one of the vice presidents of the teachers union. And I don’t think the strike was actually settled until March or April. It’s still one of the longest, if not the longest, in the history of American universities.”

The protesters achieved their desired result when a black studies program was added. But at a price. “I was reinstated, but on a non-tenured track — as punishment or discipline for demonstrating against the administration. Nathan (Hare) was fired,” Chrisman said. “Out of all that, Nathan and I developed an idea for The Black Scholar. Volume One, Number One came out November of 1969. So, we were persistent.”

Voicing a Generation

Chrisman didn’t know it then, but the example he set and the ideas he spread inspired UNO student activists in their own fight to get a black studies department. Rudy Smith, now an Omaha World-Herald photojournalist, led the fight as an NAACP Youth Council leader and UNO student senate member.“We knew The Black Scholar. It was written by people in touch with things. We read it. We discussed it,” Smith said. “They sowed the seeds for our focus as a black people in a white society. It kept us sane. He has to take some of the credit for the existence of UNO’s black studies program.” Formed in 1971, it was one of the first such programs.