Archive

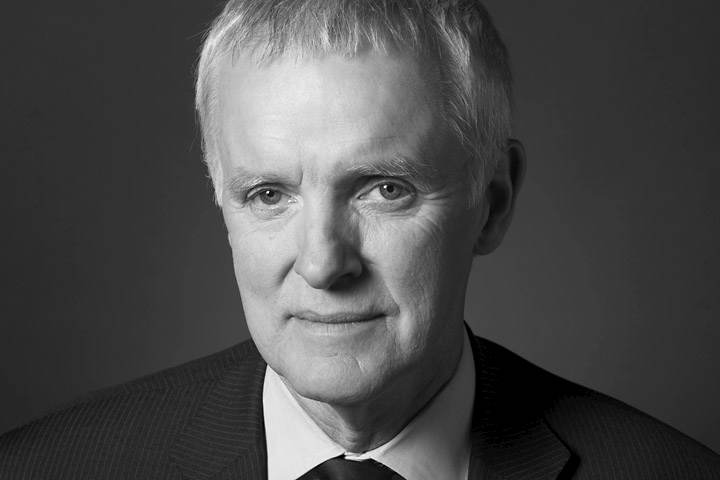

The life and times of scientist, soldier and Zionist Sol Bloom

I love proving the enduring truth that everyone has a story, especially when it comes to older individuals. It’s all too easy to dismiss an old man like Sol Bloom if you only choose to look at his wrinkled features and his stooped posture and don’t take the time or interest to learn something about the life he’s lived. Sol’s lived an unusually full blooded life that, among other things, saw him work as a scientist, soldier, and Zionist in the independence of Palestine. He’s a wonderful racanteur and writer who related his story to me in a series of interviews he gave me at his home and through several written reminiscences he shared. My profile of Sol, who was still going strong when I wrote the piece about three years ago, appeared in the Jewish Press.

The life and times of scientist, soldier and Zionist Sol Bloom

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the Jewish Press

The Omaha resident is equally sure a higher power saved him from almost certain death on at least three occasions; once, when scratched from an armed patrol whose entire ranks were decimated by an Arab ambush in the Judean Valley.Sol Bloom doesn’t believe in accidents. It’s why he’s sure he was destined to make his way to Palestine as a young, idealistic Zionist 62 years ago. Inflamed with passion to help secure a Jewish state, he left America for service in the Haganah militia.

He’s convinced something beyond mere circumstance has guided his five-decade career as a dairy nutritionist, leading him to work with fellow Jews in a field where Jews are a rarity. He’ll tell you his parents’ brave immigrant journey from Romania and a cousin’s pioneer efforts settling Palestine inspired him to beat his own adventurous path — to Israel, Puerto Rico, Nigeria, Zambia and the Philippines.

For Bloom, rhyme and reason attend everything.

The scientist in him methodically studies things to identify patterns and processes. The believer in him finds the hand of fate or God behind incidents he can’t ascribe to mere chance. He’s always been curious about the grand design at work. An ever inquisitive hunger drives his lifelong search for order, meaning and variation. He appreciates life’s richness. It’s no coincidence then he’s sought out foreign posts and immersed himself in indigenous cultures.

At age 84 he still savors life’s simple wonders, whether a Brahms symphony, a good book, a bountiful crop, a cow producing milk from rough silage, his family, his daily prayers, his research, his travels, his memories. A good batch of fu-fu.

Far from an unexamined life, Bloom’s charted his times in voluminous journals. Both the good and bad. He writes-talks with pride about his parents making a comfortable life for the family in America. He grew up in West New York and Palisade, N.J., a pair of bedroom communities outside New York City.

His reminiscences refer to a “dominant” and “disciplinarian” father pushing him and his two brothers. Despite little formal education Sam Bloom kept a complete set of Harvard classics and a Webster’s unabridged dictionary at home. On Sundays Papa Bloom held court in bed, where he regaled the boys with the florid prose of advertisements. He instilled a love of learning in Sol, Norman and Jack.

The patriarch also made sure his sons were exposed to, as Sol puts it, “the finer things.” He made them take music lessons — Sol plays the fiddle — and attend Jewish school. He took the family to Central Park for band concerts, Second Avenue for vaudeville shows and Yiddish theater productions, Coney Island for the amusement park rides and the Catskills for Borscht Belt retreats.

It was at Esther Manor near Monticello, N.Y., where the family vacationed summers, that Sol, the city boy, got his first exposure to farming. The hotel owner kept dairy cows out back to supply guests with fresh milk and Bloom made it a habit to help bring the herd in from pasture. He didn’t know it then but fattening calves and boosting milk cows’ production would take up a large part of his adult life.

Sol sees divine intervention in the Bloom boys coming from such humble roots to achieve professional heights. Besides his own exploits as an animal nutritionist, Norman became a biochemist and Jack a rabbi and psychologist.

He candidly describes a history of mental illness in his family. His late older brother Norman descended into schizophrenia, believing he was the second coming of Christ. Bloom said his younger brother Jack sought psychiatric help for a time. Their mother received electric shock treatments. Bloom himself has had problems. Jesse now struggles with his own brainstorms.The stories of old times roll off Bloom’s tongue. The words precise and poetic. The recall uncanny. He expresses disappointment, not regret, about his failed first marriage, ended when his oldest children were already grown. He acknowledges a weakness for the flesh led him to take a mistress in Nigeria and that the romantic in him led to a love affair in Manila with a woman who became his second wife, Erlinda. He and Elinda share a home together in Millard with their son Jesse.

Then there’s Bloom’s once sturdy body, now severely stooped, wracked by various maladies. It doesn’t stop the former competitive swimmer from taking daily laps in the Jewish Community Center pool.

No hint of judgment or bitterness in Bloom. He accepts what life gives, both the sweet and the sour. He awakes each morning eager to meet the day, ready to make some new connection or association or insight. Whether it’s a laboratory with four walls or the larger lab of living, he approaches life as a much anticipated experiment. Discovery always just around the corner.

His brother Norman would get in manic, obsessive moods trying to prove God’s existence in numerical coincidences. He caught the attention of the late astronomer and popular science writer, Carl Sagan, whose book Broca’s Brain devotes an entire section to Norman’s belief that he was a messenger of God.

Sol isn’t his brother but when considering certain matters, such as the proposition Jews are God’s chosen people, he assumes a slightly messianic manner himself.

Speaking as a scientist, he told a guest at his home: “I don’t know if God actually exists.” However, Bloom suggests Jews’ disproportionate impact on everything from world religion to art to politics to moral tenets is a testament to some divine plan.

“So when I go back to the fact that a good part of the western world goes by Isaac’s basis” for righteous living, “and what the Jews presented to humanity, maybe even though I’m a scientist there’s something in there that is not just completely random,” he said. “The eternal thread of Jewish survival over 3,000 years is a strong thread. That thread’s metaphorically wrapped itself around historical periods and around the throats of Egyptian, Persian, Asyrian, Greek and Roman empires and left them all lifeless — as the Jews moved on small but strong to the present day. It’s a very thin fiber, but it’s so.

“If little people like we have been able to maintain these basic moral foundations to the whole world and still exist when all these empires have gone down, then even though I’m a scientist and I have to go by hypotheses, I don’t think it’s just random. I’ll leave it at that.”

Sol Bloom just leave it at that? Impossible. Invariably, one theory begets another.

“When I lived in the Philippines (1970-’81) Manilla already was a city of 7-8 million. In Israel maybe you had at that time 2 1/2 million. And how many times did you read about that big city of Manilla in the newspaper? Maybe when there’s a typhoon or maybe when they found all those shoes in Imelda’s closet. But how many times was there something to do with that tiny fragment of humanity in Israel?

“Today, you have 6 to 7 billion people on the face of the earth while the whole population of Jews in the world is about 16 million. It works out to be about .018 percent of the total population. And yet there’s always something going on about them. Mexico City alone has 16 million. How often do you hear about Mexico City? But you will hear about the Jews being in this, doing that — out of all proportion to their numbers. That tiny fleck of humanity in six billion.

“Why for such a long time are we always hearing something about them? Isn’t that interesting?”

He’s confident the weight of evidence demonstrates Jews hold a special, even anointed place in the scheme of things. “That’s one of the things that sort of helps me maintain my faith,” he said.

All this musing leads Bloom to his own variation on the law of attraction.

For Sol, it’s more than coincidence he and Silver found each other. “Random, or as we say in my Yiddish, betokhn (faith)? Isn’t that interesting?”“The first (formal) agricultural experience in my life was with a Jew. I started at 21 with my father’s cousin, Ephraim Katz, in Palestine. And now at this point, 60 years later, I’m working with a fellow by the name of Steven Silver, who owns International Nutrition in Omaha. He’s from the same tribe as I am. Now, imagine this, OK? How many Jews are in American agriculture? Not many. How many are in the professional feed milling business? Even fewer. How many Jews do you find in the feed business in the north central area — Minnesota, Wisconsin, the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri? One. Do you follow me?”

Like Bloom’s parents, Katz, the pioneer in the family, was a Romanian emigre. Unlike them Katz felt the call to Palestine strongly enough that he became a settler there, raising a family and farming. Katz, an academic by training but a man of the soil by inclination, appealed to Bloom’s sense of wanderlust and earthiness. Tales of Katz’s contributions to the aspiring nation state fed Bloom’s imagination.

“My cousin in Palestine is growing wheat and has oranges and pears and apples. He’s growing oil seed crops for the factories in Haifa,” is what Bloom recalls thinking about this man he admired. “I mean, at that time Ephraim Katz was the leading light of our entire family. He was the one doing it.

“When he was in Bucharest, Romania he was a professor of English. Because he was a Jew he was still considered an alien and he couldn’t have citizenship, so he left and farmed in Israel, in the northern part of Haifa, near the port. He planted crops. He had wheat, sorghum, citrus.”

There were hardships and tragedies, too.

“In 1929 there were bad riots by the Arabs and they burnt his wheat and cut down all his citrus. His first wife, Sabena, died from typhus. He went into depression.”

The neighborhood where Katz’s place was located was named for Sabena. But Katz and his farm and the settlement that grew up around it survived. He remarried and raised a second family there.

Letters from Katz to Bloom’s father “about all of these adventures in Palestine” were much anticipated. When his father read the letters aloud it sparked in the “impressionable” Sol a burning desire to emulate Cousin Katz and thereby break from the prescribed roles many Jews filled then. Sol’s aptitude for science already had him thinking about medicine. Katz’s example gave him a new motivation.

“Since I was already a socialist — I was going to a Jewish socialist school — I thought, I’m going to break this Jewish commitment to being a merchant. I am going into agriculture. I am going to bring right out from the earth. So that was my raison detre.”

The promise of helping forge a new nation enthralled Bloom. “I was struck by the idealism of these people in Palestine struggling building a new frontier.”

However, at the urging of his parents, who feared for his safety in conflict-strewn Palestine, Bloom enrolled at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa. He was still a premed major. America was at war by then and in ‘43 his draft number came up. He wound up in the 99th Infantry Division but when the unit began preparations to join the fight in Europe his poor eyesight and flat feet got him transferred to guard duty at a stateside disciplinary barracks. As it turned out, the 99th’s ranks were decimated in the Battle of the Bulge.

Providential? Sol believes so. “Perhaps something else was meant for me,” he said.

After the war he worked as a counselor at a summer camp, where he met Helen, a nice Jewish girl from the East Bronx. He once again set his sights on Palestine when he learned he could study agriculture at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem under the GI Bill of Rights. He went first in 1946 and Helen followed six months later.

Cousin Katz greeted Bloom in Haifa. For Sol, it meant finally meeting the hero whose spirited example led him to make the long voyage. Katz took Sol to the rural compound of houses he’d built and to the fields he’d planted.

“He brought in new ways, new machinery, new breeds from America and he built this pioneer-type house of rough-hewn blocks and iron bars on the windows,” said Bloom, “and that’s where Helen and I were married in 1947.”

The kibbutz Sol and Helen were assigned, Gvat, “was a completely communal settlement. You never saw any money,” he said. “It had begun in 1925 with Jews from Poland and Russia. There were about 400 members and about 300 ‘illegals’ from displaced persons camps (in war-ravaged Europe). Bloom began training at the kibbutz ahead of Helen’s arrival. He worked the corn and wheat fields and the vegetable gardens. He helped harvest the fruit crops. Mucking out the poultry house and cattle pens convinced him cows were preferable to hens.

“The first silage I made was on the kibbutz — a combination of cow pee and citrus rinds-peels. It was a pit silo, layered with silage we packed down with a tractor. If you want it to ferment properly you have to extrude all the oxygen,” he said. “I fed it out (to cattle) and I’m telling you it was nice stuff, but the flies…” Oi vay!

The fertile country impressed Bloom.

“I remember the secretariat showing me the place. They were in a valley with the richest soil in all of Israel,” akin to Iowa’s rich black earth, Bloom said. “When they got there in ‘25 there were some swamps, a few cows. The settlers erected tents. If you ever want to know what Palestine looked like before the Jews started coming back in, get Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad, and you’ll understand the transformation that came about. It’s completely described there. Dismal, desolate.

“By the time I got there they’d built concrete barracks with manicured lawns. It was a mixed farm of dairy, poultry, a vegetable garden, a fruit orchard, a vineyard, forage crops for cattle and sheep, eucalyptus and field crops — sorghum, wheat, corn. They’d done all that in 20 years. It was a lovely place.”

Even then, he said, the region “produced beautiful oranges exported to Europe.”

Bloom reveled in the daily routine of kibbutz life.

“You got up about 5:30. You got your coffee and milk. I would go to work in the vegetable garden. Then about 8 o’clock you’d come into the communal dining hall, with its big bowls of porridge, and there’d be sour cream, yogurt, cottage cheese, vegetables, thick baked bread. You had a choice of a hard egg or a soft egg.

“After breakfast I’d go back and work. I was called in Hebrew a bakbok — cork. In other words, you’re used wherever you’re needed. I’d come back for lunch — a cold fruit soup made from harvested plums, apples, grapes. It’s hot in the summertime, so we would rest until about 1:30. When the heat would break we’d go back and finish our work. About 4:30 you’d shower and change your clothes. You had a set of khakis to work in and a set of khakis for the evening.

“We stopped working about noon on Friday for the Sabbath, whose observance lasted till Sunday morning. You had two weeks vacation.”

The enterprise of reclaiming an ancestral homeland moved Sol, who witnessed the settlement’s first high school graduation ceremony. He liked being part of a glorious historic tide. He couldn’t help but get caught up in what he called “that sense of purpose of destiny — of recreating something that had been hibernating for 1,800 years.”

“There was something completely mystical about it,” he said. “The land I was working on, the plums I was harvesting, they were planted by Jews, tended by Jews, plucked by Jews. The Jews had been persecuted, separated, driven from place to place for 1,900 years and here they’d gone back to the same place from which they were driven. Here they were graduating their first set of kids back on the lands where ancient Israelis had plowed and enjoyed the fruits of that land. Back in the land of Joshua and the prophets and all the greats of Israel,

“These pilgrims’ kids were training to begin life there again. You have to have a pretty strong memory in order to do that. To have lived a year in that type of community among these people who had settled, built the place, who knew why they were there, what they were doing and where they were going” was everything Bloom had hoped for and more.

He left before Israel’s formation in mid-‘48 but was there when the United Nations declared Palestine would be partitioned to allow a Jewish state amid Arab neighbors. “This was the first time in history a group made the decision that Jews, after being dispersed all over the world in ghettos, would have a place of their own,” he said. Photos he snapped then picture jubilant crowds in Jerusalem. He and Helen joined the celebration. “We danced, we sang, we drank. It was something very uplifting, something quite marvelous.”

Israel’s independence was not won without a fight and Bloom volunteered to do his share there, too. He and other Americans studying abroad joined the Haganah. Unlike most of the green recruits, who lacked any military experience, Bloom was a U.S. Army veteran familiar with weapons. But he’d never seen combat. Outside Jerusalem he went through training with fellow enlisters under the command of Haganah officers. They made simulated night patrols in the hilly terrain.

His training complete, he went on recon missions to gauge the location-strength of guerrilla Arab units. Assigned to a unit guarding the perimeter of a Jewish enclave, he wrote, “we kept guard during cold nights and moved weapons secretly by taxi cab.” He and his mates quartered in residents’ homes, staying out of sight of British peacekeepers and hostile Arab forces by day and manning rooftops at night.

He was selected for a strike force of 35 soldiers tasked with engaging the Arab Legion laying siege to the Jewish settlement of Ramat Rachel. At the last minute, he said, an officer scratched him from the operation due to his marital status. A bachelor friend and fellow American, Moshe Pearlstein, replaced him. Moshe and his comrades were cut down in an ambush. There were no survivors. Bloom’s journal commented:

“I will always remember how formidable — yes, how heroic — the ‘35’ appeared in all their battle gear as they assembled on the edge of Beit Hakarem. They were the Yishuv’s best…” Their loss, he wrote, “was a terrible blow to the Haganah…The sweet soul Moshe became, as far as I know, one of the first Americans to fall in the war of independence for Israel. His sacrifice has given me a long and eventful life.”

His life was spared another time there when a bus he and Helen were on took sniper fire. Only the vehicle’s side armor plating shielded him from the rounds.

With the couple’s parents pressing for their return they came back to the U.S. While studying at Iowa State University Bloom met Israeli emissaries who were visiting American ag colleges “to talk enthusiastic ideas to young Jewish fellows like me” he said. It was a recruitment tour designed to attract Zionists in serving the newly formed Jewish nation. Bloom was ripe for the picking. “I knew one thing — I wanted to study a profession that I could go back to use in Israel.”

He asked the visitors, “What should l study to help the State? Should I become a veterinarian?” “We need nutritionists,” he was told. That’s all he needed to hear. Besides, he said, “I liked very much working with cattle when I was on the kibbutz.” From ‘50 to ‘55 he earned his bachelor’s degree from Iowa State, his master’s from Penn State and his Ph.D. from ISU. All in dairy applications.

His scientific inquiries in that period proved fruitful. At PSU, he said, “the first feed grade antibiotics were in use. I worked with oromycin — I got beautiful gains. I got the sense of how powerful biological (compounds) are.” Of how 20 grams “of this yellow powder in a ton of feed” could increase milk production. Magic dust. He went back to ISU, he said, “where this line of study was more advanced. I worked with very good people. The work I did gave off papers in three different fields. I was elected to Sigma Xi, a scientific honorary society. I won the Borden Award.”

Longing to apply his expertise in Israel he was frustrated when no position was immediately available. Thus, in ‘56 he followed his nose for adventure to Puerto Rico, where he worked on dairy cattle feeding trials and introduced high molasses rations for swine. When a post finally opened in Israel the next year to conduct a Ford Foundation study at a research station, the Suez Canal crisis erupted. The U.S. government issued stiff warnings to Americans to avoid travel there but a little war wasn’t going to stop Bloom “I went anyway,” he said. “They (the American consulate) called me in and slapped my wrists.”

These were heady times for Bloom.

“It was exciting. In the Suez campaign all the agronomists had gone into the Sinai Peninsula and had just come back, so the first seminars I heard were all about their findings in that area. When I did my research the agronomists there wanted us to use more pasture. We didn’t have that much. Security was a problem.”

The study compared cows feeding in pastures to those feeding off silage in enclosures. The herds “were then hit by foot and mouth disease,” he said, “which cut off some of the work I did over there.”

He was just happy to be back in a flourishing, independent Israel. He was, in many ways, home again.

“There’s a deep Jewish cultural connection,” he said. Not to mention “the beauty of living as part of the majority. There’s a certain sweetness, a certain pleasure in that that even today with our liberal (tolerant) attitudes you don’t quite have here (in the U.S.).”

He and Erlinda traveled to Israel in 2003. He hadn’t been there since 1962 and he marveled at how a once dreary stretch of road outside Tel Aviv “was green all the way to Jerusalem. That is my road. It’s built by Jews.” The whole country’s transformation from dusty outpost to verdant oasis satisfied him. “Israel’s a beautiful place, and it means so much,” he said. “There’s a personal connection.”

His much-traveled life-career has taken intriguing turns outside Israel. For example, in 1964 he was hired by the Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia. He said it marked “the only time in my life I worked in the medical profession. I worked with many oncologists and cardiologists in helping them design their studies. In the building there were about 30 prima donna medical and biological researchers and I learned how to get things done” in terms of landing research grants.

Nigeria was in the throes of a civil war, making difficult living conditions even harder. Bloom was largely untouched by the conflict. “The only way USAID people felt this war was in the many checkpoints on the roads, the frequent searches of our vehicles and the presence of troops in training,” he wrote.

A memorable experience was leading a convoy of trucks loaded with 15 tons of seed corn across Nigeria to impoverished Biafran farmers. Despite bad roads, devastated villages, chaotic assundry delays, the delivery was made.

Bloom spent four conflicted years there. The affair he carried on with his housekeeper, Rose, came in the wake of “the powerful loneliness” he felt so many miles from home. “Combined with my own mental anxieties,” he wrote, “it endangered my ability to function, and so it was to the journal I turned to record daily activities to maintain sanity and stability.” To numb the pain there was plenty of Star Beer and dancing under the starlight to the sound of talking drums.

In 1970 the USAID sent him to Zambia to advise/study the local swine industry. He wrote, “Mind you, you find Jews almost anywhere in the world, but I didn’t expect to find any in Zambia.” But he did in the Shapiro family, who adopted him. “I have found Jews in the most exotic places,” he wrote in his African memoirs.He took an extended R & R in Spain, where the bull fights both intrigued and repulsed him. Like most in the crowd he rooted for “the majestic creature.”

That same year he began his longest overseas idyll, in the Philippines, where he stayed through 1981. He went in the employ of the USAID but eventually became a free agent. He was a nutrition consultant for swine operations and feed mills, he created and marketed his own Rose-N-Bloom brand livestock feeds with another American expatriate and worked for the American Soybean Association and corporate giants Cynamid and Monsanto.

He became close with an American ranch family, the Murrays. Bloom loved riding out on their high grass tropical range. Pastures gave way to jungle. The ranch was accessible only by boat or plane. Getting the steers to market was a big operation.

The Philippines is also where Bloom met and married Erlinda, “my Oriental package.” They started a family together there.

“I came back from the Philippines in ‘81 — to Richmond, Ind. Erlinda had a cousin living-working there. God took me to a place, the Midwest, with corn, soy, cattle, pigs, where I could begin my work again,” he said,

Over the next dozen years his work necessitated more moves. Vigortone Ag Products in Marion, Ohio. Dawes Laboratories in Chicago. At Dawes he developed vitamin-mineral fortifiers for animal industry species. Omaha-based I.M.S. Inc. brought him to Omaha in 1989 as its senior nutritionist.

He stayed here after hooking up with Steve Silver’s Omaha-based International Nutrition in 1990. Meeting up with another Jew in the goy ag field only confirmed Bloom’s belief that far from “purely chance” it was “supposed to happen.” At least he chooses to believe so. The very thought, he said, “is a comfort to me.”

Silver said Bloom brought “a wealth of experience. He worked in helping develop products for use in our overseas markets.” Though mostly retired now, Bloom said, “I’m still working a little bit. “I’m doing something on the co-product or residue from ethanol production and how to make it more amenable for pigs and poultry and so forth and so on. It’s interesting”

Away from work Bloom enjoys “the little pleasures of the day.” Listening to his beloved Brahms. Praying/socializing at the synagogue. Doing mind exercises.

When reviewing his life, he said, “Sometimes I think, Did I do all these things? It’s hard to imagine.”

Related articles

- Why and when was the nation of Israel created (wiki.answers.com)

- The Zionist Story (alhittin.wordpress.com)

From wars to Olympics, world-class photojournalist Kenneth Jarecke shoots it all, and now his discerning eye is trained on Husker football

Photojournalist Kenneth Jarecke is as intrepid as they come in his globe-trotting work. He covers everything, from wars to Olympic Games, in all corners of the world, always seeing deeper, beyond the obvious, to capture revelatory gestures or behaviors or attitudes the rest of us miss. With his new book, Farewell Big 12, he examines the University of Nebraska Cornhusker football program’s last go-round in the Big 12 Conference through his unique prism for making images of moments only the most discerning eye can recognize and document. He sets off in relief the truth of individuals and events and actions, drawing us in to bask in their beauty or mystery.

Two photographer mentors of Jarecke’s, Don Doll and Larry Ferguson, are also profiled on this blog.

A gallery of Jarecke’s images can be seen at http://www.eyepress.com. His book can be purchased at http://www.huskermax.com.

From wars to Olympics, world-class photojournalist Kenneth Jarecke shoots it all, and now his discerning eye is trained on Husker football

©by Leo Adam Biga

In his 26 years as a Contact Press Images photojournalist, award-winning Kenneth Jarecke has documented the world. Assignments for leading magazines and newspapers have taken him to upwards of 80 countries, some of them repeatedly.

His resulting images of iconic events have graced the pages of TIME, LIFE, Newsweek, U.S. News & World Report, National Geographic, Sports Illustrated and hundreds of other publications. His work has been reproduced in dozens of books.

He has captured the spectrum of life through coverage of multiple wars, Olympic Games and presidential campaigns. He has documented the ruling class and the poorest of the poor. He has photographed the grandest public spectacles and the most intimate, private human moments.

Wherever the assignment takes him, whatever the subject matter he shoots, Jarecke brings his keen sensitivity to bear.

“I know how to capture the human condition,” he said.

His well-attenuated intuition and highly trained eye followed the University of Nebraska football team on its last go-round through the Big 12 during the 2010 season. The result is a new coffee-table book, Farewell Big 12, that reproduces 300 Jarecke photographs, in both black and white and color, made over the course of 10 games.

He is planning a companion book, Welcome to the Big 10, that will document the Huskers throughout their inaugural 2011 season in the fabled Big 10 conference.

The projects represent his first solo books since 1992, when he published a collector’s volume of his searing Persian Gulf War I photos entitled, Just Another War.

His work has shown at the Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery in Lincoln, at Nomad Lounge in Omaha, at the Houston Fine Arts Museum and at other galleries around the nation.

Coming Full Circle

The Husker photo books have special meaning for Jarecke, a native Nebraskan and one-time college football nose guard, who wanted to give Husker fans and photo aficionados alike a never-before-seen glimpse inside the game.

“It’s something I always wanted to do. I wanted to do an in-depth season in my own style, capturing the kind of images I like to see and make. I don’t cover football or sports as a news event, I cover it as an experience.

“I don’t care about the winning touchdown, I don’t care about really anything except what I can capture that’s interesting. So, it might be a touchdown or it might be a fumble or it might be concentrating on something completely different (away from the action).

“You don’t really see those type of pictures too much.”

His instinct for what is arresting and indelible guides him.

“It could be the light was right in this area. It could be something I see on somebody’s helmet or hand. It could be something I’ve seen somebody do two or three times and I follow this guy around to see if that happens again. My goal is to not record the game as it happens, my goal is to try to give an idea of what it’s like inside that thing.”

As a University of Nebraska at Omaha nose guard, he lived in the trenches of football’s tangled bodies, where violent collisions, head slaps, eye gouges and other brutal measures test courage. As a world-class photographer with an appreciation for both the nuanced gestures and the blunt force trauma of athletics, he sees what others don’t.

“I understand the game of college football from an inside perspective and I know how to shoot sports.”

“He’s a person who has this gift of seeing. He’s a 360-degree seer,” said noted photography editor and media consultant and former TIME magazine director of photography MaryAnne Golon. “What you’re going to get is Ken’s take, and Ken’s take is always interesting. Plus, he has a very strong journalistic instinct, and not every photographer has that.”

He is well versed in the hold the Huskers exert on fans. Indeed, his first national assignment, for Sports Illustrated, was a Husker football shoot.

“I’m basically circling back with this project,” he said. “In a lot of ways this Husker book is a dream project. As a native, I understand what this program means to the people of the state. and I wanted to capture it. That’s basically the bottom line.”

What appears on the surface to simply be a football photo book hones in on behavior – subtle or overt, gentle or harsh – as the mis en scene for his considered gaze.

“That’s the same approach I take to anything,” he said.

“Ken possesses an uncanny artistic exuberance and a deliberateness that belie his quiet personality,” said Jeffrey D. Smith, Jarecke’s Contact agent.

“Like a hunter methodically stalking his prey, Ken quickly and silently sizes up his surrounds, and determines position, shying away from the obvious. He assesses the light, watching how it changes, then he waits. He waits till the moment’s right, till the crowds thin, till the explosion of action provides an awkward off-moment or someone pauses to catch their breath, and then BAM, Ken catches the subject floating and off-guard.”

Camera as Passport

This sense of capturing privileged, revelatory moments is the same Jarecke had when he first discovered photography at age 15 in his hometown of Omaha.

“I realized that with a camera in your hand you basically had an excuse to invite yourself into anybody’s life. I figured out real quick it’s like a passport.”

A camera, when wielded by a professional like himself, breaks down barriers.

“As a photographer you’re completely at the mercy of kindness from strangers wherever you go in the world. Whether you speak the language or not, you’re with strangers, and it never ceases to amaze me how kind people are and how open they are. And if not helpful, how they just leave you alone to go about your business, and it’s been that way everywhere.

“Yeah, I’ve had nasty experiences, but even then you see where there’s like a silver lining, and somebody helps you out somehow.”

He remembers well when photography first overtook him and, with it, the purpose-driven liberation it gave him.

“It was the end of my sophomore year at Omaha Bryan High School when I met a couple guys photographing football-wrestling-track. I was in all that. A guy named Jim Guilizia (whom Jarecke is still friends with today) invited me to see the school darkroom and how it works. And the first time I saw that I was like, ‘I’ve found something to do with my life.’ It was just that quick, just that easy. It was a done deal. Like magic.

“My dad had a 35 mm camera, so I started messing with that.”

Reflecting back, Jarecke said, “I didn’t know exactly what a photographer was. I mean, I thought it was this thing where you go and shoot a war and you come back to New York City and do a fashion shoot. I knew that’s what I wanted to do.” He wanted it so badly he quit football over the objections of his coach, arguing it left no time for photography.

“I felt like I was already missing out on things. I had to get to making pictures.”

His actual career has not been so unlike the idyll he imagined it to be, though as an independent contractor it has been a struggle at times. The challenges he may endure are outweighed by the freedom of operating on his own terms.

“I’ve always been a freelance photographer,” he said.

He has worked with every conceivable budget and circumstance – from all expenses paid, full-access, months-long sojourns to zero budget, uncredentialed gambits funded himself. He doesn’t let obstacles get in the way of doing his work.

“It seems strange, I know, but I’ve gone to countries without visas.”

His mantra is: “Somehow, I’m going to find a way.”

His skills at improvising and making-do in difficult situations and in a highly competitive field have steeled him for the lean times. Like today, when the market for editorial photography has shrunk as print media struggle to survive in the digital age.

“Basically I was forced to keep getting better, keep getting smarter, keep working. I’m a better photographer today then I’ve ever been,” he said. “I’ve been hungry with this profession for 30 years. That’s the difference. If you’re making a living with a camera today, you’re already in the 96th-97th percentile. How do you get to that 99th percentile?

“The whole struggling thing has made me stronger, has given me an edge. I think it’s more of a blessing than a curse.”

Magnum photographer Gilles Peress admiringly calls Jarecke “one of the few free men still in existence,” adding, “I think he’s great.”

School of Hard Knocks

Jarecke broke into the ranks of working photographers with a by-any-means-necessary ethic.

At 18 he got his first picture published – of an escaped Omaha Stockyards bull subdued on a highway. He became a pest to Omaha World-Herald editors, ”borrowing” its darkrooms to process his images. Sometimes he even sold one or two.

He became a stringer for the AP and the UPI.

“I was doing whatever I could do,” he said. “I never had a press pass. It was always, Which door can I sneak through? Literally.”

Jarecke often refers to the uneasy balance of chutzpah and humility top photographers possess, qualities he displayed when, still only a teen and with minimal experience, he flew to New York City to be discovered.

Against all odds he talked his way in to see Sports Illustrated editor Barbara Hinkle, who reviewed his meager black and white portfolio and offered advice: Start shooting in color and filling the frame. He heeded her words back home and built up a color portfolio.

His first big break came courtesy SI via an early-1980s Husker football shoot. He itched for more. Local assignments just weren’t cutting it for him financially or creatively.

“I was pretty frustrated. I was already at the point where I could make their pictures, but now I wanted to make my pictures.”

It was time to move on, so he headed back to NYC, where he “pieced together a living.” “I always had a camera in hock,” he said. “I was kind of stumbling along, living out of a suitcase for two or three years. I was broke.”

Among the best decisions he made was attending back to back Main Photographic Workshops: one taught by Giles Peress and another by David Burnett and Robert Pledge of newly formed Contact Press Images.

It was not the first time Jarecke studied photography. He counts among his mentors two Omaha-based image-makers with national reputations, Don Doll and Larry Ferguson, who took him under their wing at various points.

During one of his forays at college, editor MaryAnne Golon was judging a photography show in Lincoln, Neb. when she saw the early potential that eventually led him to working for her at TIME and U.S. News.

“I met Ken when he was an emerging photographer and I remember the work standing out then, and he was like 19, so it was interesting to watch the progression of his career,” she said. “I think he has a very lyrical eye. He’s a classic case of a photographer who comes out with some little magic moment.”

Bobbi Baker Burrows, director of photographer at LIFE Magazine Books, has also seen Jarecke grow from a wunderkind to a mature craftsman. “He just never ceased to amaze me in his growth and his artistry and his strong journalistic integrity,” she said. “As an adoptive mother to Ken I was so proud to see him blossom into a fine person as well as an extraordinary photographer.”

Breaking Through

Jarecke said he got noticed as much for his talent as for his attitude. “I was obnoxious, I was arrogant.” Chafing at what he considered “too much naval gazing and thinking” by fellow students, he advocated “going with your gut.”

“It was very clear right off the bat he was quite a special, unusual character on the one hand and photographer on the other. Quite daring also,” said Pledge.

Pledge became a champion. With both Pledge and Burnett in his corner, Jarecke became an early Contact Press Images member. Pledge assigned Jarecke his breakthrough job: getting candid shots of Oliver North at the start of the Iran-Contra affair.

“I actually got his (North) home address through a Sygma photographer. Back then there were a lot of photo agencies. We were all competitors, but we all kind of worked together, too.”

From his car parked along a public street, Jarecke staked out North’s home. “I hung out from sunrise to sunset, waiting for him to mow the lawn or something. I was down to two rolls of film when this LIFE magazine photographer showed up. He had some type of agreement with Ollie that he’d get exclusive pictures. But he wasn’t allowed to go into Ollie’s place. It was like a wink and nod deal.

“This photographer had a small window to get his pictures and my being there was screwing up his whole deal.”

Frantic phone calls ensued between the LIFE photographer and his editor and Jarecke’s agent, Robert Pledge. LIFE insisted Pledge get his bulldog to back off, but Jarecke recalls Pledge giving him emphatic orders: Whatever you do, don’t leave.

“I explained to Bob I didn’t have any film. He said, ‘I don’t care, just pretend like you’re making pictures.’ It was a bluff with very high stakes.”

Jarecke did make pictures though, “shooting a frame here and a frame there,” shadowing the LIFE photographer.

“I just had to cover everything he covered.”

Jarecke’s persistence paid off. His work effectively spoiled LIFE’s exclusive, forcing the magazine to negotiate with Contact. “LIFE had to buy all my pictures that were similar to the ones in the magazine, basically to embargo them.” Jarecke found eager bidders for his remaining North images in Newsweek and People.

“I went from being broke to making a huge sell over like one week. That allowed me to keep working.”

Recognizing a good thing when they saw it, LIFE hired Jarecke to shoot some stories. Offers from other national mags followed. In 1987-1988 he traveled constantly, covering all manner of news events, including the elections in Haiti, an IRA funeral in Belfast that turned violent and the Seoul Summer Olympics. He was the most published photographer of the ‘88 presidential election campaign. His in-depth coverage of Jesse Jackson earned him his first World Press Photo Award.

In 1989, he became a contract photographer for TIME, whose editors nominated him for the International Center of Photography’s Emerging Photographer Award. Jarecke fulfilled his promise by producing cover stories on New York City, Orlando and America’s emergency medical care crisis. The 1990 “The Rotting of the Big Apple” spread attracted worldwide attention. His nine pages of black and white photographs dramatically illustrated the deterioration of America’s greatest metropolis. The piece’s signature picture, “Two Bathers,” won him another World Press Photo Award.

He didn’t know it then, but these were the halcyon times of modern photojournalism.

“Back then we used to spend a month on a story, not three or four days like we do now.”

it was nothing for a major magazine to send a dozen or more photographers and a handful of editors to a mega event like the Olympics.

When not on assignment, the TIME-LIFE building became something of a tutorial for Jarecke. In his 20s he got to know master photographers Carl Mydans, Alfred Eisenstaedt and other originators of the still very young profession.

“If you’re Yo-Yo Ma today, that’s like hanging out with Mozart,” said Jarecke. “You’re standing on the shoulders of these giants that paved the way and you have their careers to build off of.”

Photographing and Surviving a War Zone

Then came his coverage of Desert Storm and a controversy he didn’t bargain on.

The U.S. military instituted tight control of media access.

“I was a TIME magazine photographer at that point. I didn’t want to be in the (U.S.) Department of Defense pool, but I was forced to be in this pool. AP set up all the rules of engagement, down to the type of film you shot.”

Near the conclusion of fighting Jarecke was with a CBS news crew and a writer. Escorting the journalists were an Army public affairs officer and his sergeant. All were geared up with helmets and flak jackets.

It was still early in the day when the group came upon a grotesque frieze frame of the burned out remains of fleeing Iraqi forces attacked by coalition air strikes. Jarecke took pictures, including one of an incinerated Iraqi soldier. Jarecke’s images of the carnage offered unvarnished, on-the-ground glimpses at war’s brutality. The photos’ hard truth stood in stark contrast to the antiseptic view of the war leaders preferred.

At a certain point, Jarecke recalls, “we broke off from our pool” to avoid the Republican Guard. “We had this stupid, stupid plan to drive cross country into Kuwait. We started with two vehicles – a military Bronco and a Range Rover. We headed out across the desert with no compass, no map. We had a general idea of the direction we needed to go, but we immediately got lost.”

At one point Jarecke and Co. ran smack dab into the very forces they tried to avoid, and got shelled for their trouble, but escaped unharmed. Technically there was a cease fire, but in the haze of war not everyone played by the rules.

Skirting the combatants, the journalists and their escorts went off-road, ending up farther afield than before. The journalists waited until twilight to try and circle around the Republican Guard. The normally 45-minute drive was hours in progress with no end in sight.

“We’re seriously lost.”

Unable to make their way back onto the highway, the situation grew ever more precarious.

“The Bronco kept getting flat tires. We finally abandoned it and we all piled into the Range Rover.”

Around midnight, Jarecke’s group found themselves amid a caravan of non-coalition vehicles in the middle of a desert no-man’s land. “We’re playing cat and mouse throughout the night through the minefields, through the burning oil fields, through Iraqi fortified positions. We got our wheels tangled up once in their communication wires.”

Adding to the worries, he said, “we were almost out of fuel.” Nerves were already frayed as he and his fellow reporters had been up five days straight. Relief came when they stumbled upon a fuel truck and a small Desert Rat (British) unit. A new convoy was formed in hopes of regaining the highway. Then an idle American tank came into view.

“At 2 a.m. you don’t drive up to a tank and knock on the door,” said Jarecke. “You’ve got serious concerns with friendly fire and protocol and passwords of the day. It was dicy, but they recognized us.”

It turned out they were atop the highway, only the drifting sand obscured it.

“We’re still like 40 miles outside Kuwait City, but we’re on our way. We’ve got these Desert Rats behind us and we’re tooling along. At that point we’re kind of relaxed. I drifted off and when I awoke we’re in what looks like a parking lot with all these stopped vehicles. The Desert Rats are gone. We’ve lost them.

“I get out of the car and see a Russian machine gun set up on a truck, the silhouette visible in the light from the distant fires. Then I realize I hear a radio and that some of these vehicles are still running. It’s a mystery. Where are we? How’d we get here?”

Leaving the surreal scene, he said, “It was obvious trucks were running and eyeballs were on you. And then at some point we drove out of it and we were back on the highway, and we made it into Kuwait City as the sun was rising.”

Controversy, New Directions, Satisfaction

A couple days later Jarecke said he was trading war stories with a CBS news producer, who commented, “You won’t believe what we just saw – we’re calling it the Highway of Death,’ blah, blah, blah…”’ Looking and sounding eerily familiar to what Jarecke had driven through earlier, he said, “We were there.”

Back home, his incinerated soldier image was the object of a brouhaha. Deeming it too intense, the AP pulled the photo from the U.S. wire. The photo was distributed widely in Europe via Reuters and on a more limited basis in the U.S. through UPI. Jarecke and others were dismayed censorship kept it from most American print media.

“I thought I had done my job. I’d shown what I’d seen, and let the chips fall where they may. I thought being a journalist was supposed to be trying to tell the truth.”

He said so in interviews with BBC, NPR and other major media outlets. Eventually, that picture and others he made of the war were published in America. The iconic photo earned him the Leica Medal of Excellence and a Pulitzer Prize nomination.

Meanwhile, in the flood of Gulf War books, many utilizing his work, he tried to interest publishers in his own book, Just Another War, picturing the carnage. Admittedly an experiment that juxtaposes his visceral black and white images with art and poetry by Exene Cervenka, publishers declined. He self-published.

Jarecke’s imagery from the Gulf, said Contact’s Robert Pledge, is “really outstanding and unexpected and very personal. It’s some of the best documentation of that war.”

In 1996 Jarecke left TIME to be a contract photographer at U.S. News & World Report, where he made his mark in a decade of high-end, globe-trotting work.

“He’s the kind of photographer that when you send him out you know you’re going to be surprised when he comes back and surprised in a joyful way,” said MaryAnne Golon. “I’ve worked with him off and on for over 20 years and I’ve never been disappointed in an assignment he’s done.”

“He’s very determined. He really spends the time looking for things to give a shape and a meaning. He’s someone who’s very thoughtful with his eye. He looks at a situation and tries to dig in deep and look with greater detail,” said Pledge. “He’s able to seize upon things.”

Contact co-founder and photographer David Burnett has worked on assignment with Jarecke at major venues like the Olympics, where he can attest to his colleague’s intensity.

“It’s quite something to be able to see Ken about the fourth or fifth day at the Olympic Games, when we’re just starting to get really into it, really tired, and really frustrated. He’s walking down a hallway with this killer look on his face, holding two monopods, one with a 400 and one with a 600. He looks like he’s got the thousand yard stare, but he knows exactly where he’s going

“And it’s a treat to watch, because when he gets wound up like that, the pictures are amazing.”

Today, Jarecke, his wife, and the couple’s three daughters and one son live far from the madding crowd on a small spread in Joliet, Montana. His hunger to make pictures still burns.

“Working without a net keeps me going for that next mountain, and the truth is you never reach it.”

Elusive, too, is the perfect picture.

“There’s no such thing, because if it is perfect it’s no good. There has to be something messy around the edges. That’s part of the mystery of creating these pictures. They almost get their power from the imperfections.”

Imperfect or not, his indelible observations endure.

With his iconoclastic take on Husker football, he’s sure he’s published a collection of pictures “no one else is making.” He’s pleased, too, this quintessential Nebraska project is designed by Webster Design and printed by Barnhart Press, two venerable Nebraska companies.

“No small feat,” he said.

With traditional media in flux, Jarecke looks to increasingly bring his work to new audiences via e-readers and tablets. His art prints are in high demand.

Golon said the present downturn is like a Darwinian cleansing where only the strongest survive and that Jarecke “is definitely one of the fittest, and so I’m sure he’ll survive” and thrive.

War and Peace: Bosnian refugees purge war’s horrors in song and dance that make plea for harmony

Here is a story I did in 1996 in the flood of refugees coming to America from war-ravaged Bosnia and Serbia. I tell the story of two families from Saravejo whose lives were turned upside down when the city fell under siege. Rusmir and Hari stayed behind to fight, as their wives and children narrowly escaped, eventually to the West. The men were eventually reunited with their families and ended up starting new lives in America. In my hometown of Omaha no less. I came across this story when I learned about a music and dance performance that a local choreographer organized as a way of commemorating the experience of these Bosnian refugees. The cathartic performance served as a bridge between the war that changed everything and the peace they had to flee their homeland to find.

|

Bosnian refugees purge war’s horror’s in song and dance that make plea for harmony

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Even with United States peacekeeping troops stationed in Bosnia-Hercegovina, the war-ravaged nation and troubled Balkan region remain a shrouded mystery to many Americans.

But on two successive nights in October, audiences packing a Creighton University theater came face-to-face with the tragic, ultimately triumphant odyssey of Omaha’s Bosnian war refugees.

The forum for this unusual intersection of cultures was the finale of an October 25-26 Omaha Modern Dance Collective concert. The closing piece, “Day of Forgiveness,” featured a melting pot of dancers and musicians, but most poignantly, local Bosnian refugees performing as a five-piece band

The work incorporated vigorous Bosnian folk dances and songs symbolizing the relative harmony in Bosnia before the war and the healing so sorely needed there now. Ironically, a dance whose context was an ethnic war, joined Croats, Muslims and Serbs in a unifying celebration.

The refugees are among a growing, diverse Bosnian colony that has sprung up in Omaha since 1993. They say the Bosnia they knew was free of ethnic and religious strife until Serb nationalism began rearing its ugly head. Many are natives of Sarajevo, where they enjoyed an upscale, Western European lifestyle. Since escaping the carnage to start over in America, they’ve forged a tranquil Little Sarajevo in Omaha.

“Bosnia was like a small United States, where many different cultures, many different religions lived together,” says the band’s lead vocalist and guitarist, Rusmir Hadzisulejmanovic, 41, formerly a marketing manager with a Sarajevo publishing firm. Today, he works as a handy man and attends Metropolitan Community College. “We prepared a good life in our country. We had nice jobs. We made good money. But somebody from outside tried to destroy that. And we lost everything in one day.”

Fellow refugee and musician Muharem “Hari” Sakic, 39, a friend of Rusmir’s from before the war, was an import-export executive and now works odd jobs while attending Metro. Hari says, “In Sarajevo we never cared what religion you were. And none of us care about that now. It doesn’t matter. We only care what kind of person you are.”

Both men are Muslim. Rusmir’s wife is Serb; Hari’s, Croation-Catholic. They say mixed marriages such as theirs were typical.

The two men fought side-by-side defending their beloved Sarajevo, the besieged Bosnian capital devastated by Serb aggressors. Talking with Rusmir and Hari today, surrounded by loved ones in their safe, comfortable southwest Omaha apartments, it’s hard to imagine them as fierce soldiers engaged in a life and death struggle with forces who outnumbered and outgunned them. But then Rusmir passes around snapshots of he and Hari in camouflage fatigues, armed to the teeth, outside the burned-out shell of a train station. A later photo shows Rusmir, usually a burly 240 pounds, looking pale, drawn and shrunken from the near-starvation war diet.

War Hits Home

Although Serbia invaded Croatia by late 1990, beginning the pattern of pogroms and atrocities it repeated elsewhere in the former Yugoslav Republic, most Bosnians never suspected the conflict would affect them. But it did, beginning, shockingly and viciously at noon, April 4, 1992, when Serb artillery units dug in atop the hills overlooking Saravejo launched an unprovoked, indiscriminate attack on the city’s homes, streets and businesses.

Rusmir was eating lunch in a cafeteria when the first explosions rocked the city. He was trapped there until morning. “I saw many, many damaged houses and cars and dead people in the streets. It was the first time in my life I saw something like that,” he recalls. It was the start of a three-year siege that killed thousands of civilians and soldiers.

At the family’s apartment he found his wife Zorana, 39, and their children Ida and Igor, then ages 8 and 2, respectively, unharmed, but “very scared.” He immediately set about finding a safe way out for them. Escape was essential, since Ida suffers from a serious kidney disease requiring frequent medical treatment, and his family’s Muslim surname made them targets for invading Serbs. As for himself, he had no choice but to stay – and fight.

The roads and fields leading out of town were killing zones, manned by roaming Serb militia. Air service was disrupted. With the help of Jewish friends he finally got his family approved for a flight to Belgrade, Serbia several days later. On the day of departure Zorana and the kids boarded a bus for the tense ride to the Serbian-held airport. As it was too dangerous to be seen together, Rusmir followed behind in a car.

The scene at the airport was chaotic. Hundreds of people milled about the tarmac, frantic not to be left behind. When a mad dash for the plane began, Zorana, carrying Igor in one arm, felt Ida being pulled away by the surging crowd. She grabbed hold of her daughter and hung on until they were aboard.

From a distance Rusmir watched the plane lift off safely, carrying his family to an uncertain fate. It was the last flight out for many months. Three-and-a-half years passed before he saw his family again.

While in Belgrade, Zorana and the kids stayed at a hotel. Zorana made Ida promise (Igor was too young) never to say their Muslim name aloud, but only her Serb maiden name, Vojnovic. Zorana says she felt “shame” at denying her true identity and “guilty” for what some Serbs were doing to Muslims. “It was very hard.”

“You had to say some Serb name to save your life,” notes Hari, whose family took similar precautions. Like Rusmir and Zorana, Hari and his wife Marina were desperate to get their daughter Lana out, as she has a kidney condition similar to Ida’s. Marina and Sakic’s kids eventually fled to Croatia.

In Belgrade Zorana often confronted Serb enmity, such as when a hospital denied Ida treatment fate learning her real name. From Belgrade, they fled to norther Croatia, staying with relatives and friends.

Life in Croatia had a semblance of normality until Croat-Muslim hostilities erupted. Then Zorana was denied work and Ida expelled from school and refused care. A human rights organization did fly Zorana and the kids to London, where her brother lived, but they were denied residency and returned to Croatia. Growing more desperate, she pleaded her family’s case at every embassy, to no avail.

With few resources and options left she heard about the International Organization for Migration (IOM), a humanitarian agency offering visas based on medical need. After her first entreaties were rejected she went to IOM’s offices “every morning for three months,” before finally getting the visa that eventually brought them to Omaha in October, 1993. Zorana was among the first group of Bosnian and Croatian refugees to arrive here.

Omaha – A New Home, A New Life

Why Omaha? Dr. Linda Ford, a local physician affiliated with IOM, was matched with the family as a medical caseworker and mentor. Zorana says Ford was her “main moral support” when she first arrived. “She showed me how to live on my own. She was a great help.”

Ford arranged for the family to live at the home of Dr. Dan Halm and at her urging Zorana, an attorney in Saravejo, earned a para-legal degree at UNO while working part-time jobs. Zorana now works full-time at Mutual of Omaha. Ford says the contacts Zorana made here as a result of her own refugee experience have aided other Bosnians in settling here, including Rusmir’s sister and brother-in-law. Since moving her family to the Woodcreek Apartments, Zorana has guided 12 other refugee families there.

Barbarism, Heroism and Sacrifice

Meanwhile, Rusmir, who as a young man served in the Yugoslav equivalent of the CIA, had joined Hari and others in mobilizing the local Bosnian Army, It was a civilian army comprised of Muslims, Croats and Serbs, They lacked even the most basic supplies. Uniforms were improvised from sleeping bags. Many soldiers fought in athletic shoes. Shelling and sniper fire continued day and night. The streets and outlying areas were a grim no-man’s land. The only respite was an occasional cease-fire or relief convoy.

As the siege progressed conditions worsened. Rusmir’s and Hari’s homes were destroyed. But life went on. “In war it’s not possible to keep a normal life, but we tried,” says Rusmir. For example, school-age kids who remained behind still attended classes, and Hari’s wife Marina gave birth to their son, Adi, on May 22, 1992.

“At that time the situation was terrible, especially for babies. No food, no water, no electricity , no nothing,” Hari recalls.

Somehow, they hung on. Marina and their two children got out as part of a Red Cross convoy that fall.

Hari and Rusmir fought in a special unit that took them behind enemy lines to wreak havoc, do reconnaissance, collect intelligence and capture prisoners. Miraculously, neither was wounded.

“I was many times in a very dangerous position,” says Rusmir. “I know how to use a gun and a knife. That helped me to survive. I’m lucky, you know? I survived.”

Two of his best friends did not – Dragan Postic and Zelicko Filipovic.

Rusmir witnessed acts of barbarism, heroism and sacrifice, An artillery shell landed amidst a group of school kids during recess, killing and maiming dozens. “That was very awful.” In the heat of battle, a comrade jumped on an enemy tank and dropped hand grenades inside the open turret, killing himself and the tank’s crew. Despite overwhelming odds and losses the city held. “We stopped them…we survived,” Rusmir says.

By the time a United States-brokered and NATO-enforced peace halted the war in 1995, Rusmir, who’d stayed gallantly (“Stubbornly,”says Zorana) on to protect his homeland and care for his ill father, felt very alone. Except for his father, there was nothing left – no home, no job, no family, no future. Hari was gone, too, escaping on 1994 on foot via a tunnel dug under the Saravejo airport, and then over the mountains into Croatia, where after a long search he was reunited with his family.

The Sakics emigrated here in January, 1995.

Music – Celebration and Mourning

Every refugee has a story. The Bosnians’ story is of suddenly being cast as warriors and wanderers in an ethnically-cleansed netherworld where borders and names suddenly meant the difference between freedom or imprisonment, between living or dying.

It all happened before – to their parents and grandparents in World War II. It’s a story burned in their memories and hearts and told in stirring words, music and dance.

Their music inspired choreographer Josie Metal-Corbin to create “Day of Forgiveness.” The professor of dance at the University of Nebraska at Omaha first heard the music when a former student and Bosnian emigre brought the band to her class. They played about 10 minutes and right away I knew I had to do something with this music,” Metal-Corbin recalls. “I was very taken by it, I’m part Italian and part Slovak, and this music really spoke to me. It’s very passionate.”

After months of working with the musicians and UNO’s resident dance troupe she directs, the Moving Company, Metal-Corbin grew close to the refugees and their families, particularly Rusmir, Zorana and their children, now ages 12 and 6. Zorana acted as the project’s interpreter and cultural guide.

During the Creighton concert, which marked the dance’s premiere, Rusmir and the other, all-male musicians exuberantly accompanied the rousing dance from a rear corner of the stage.

Rusmir, who grew up singing and playing the romantic tunes that accompanied the dance, says, “I feel the songs in my heart, in my soul, in my blood.” Song and dance are a big part of Bosnian celebrations, which can last from evening through dawn.

A Gypsy song – “Djurdjevdan” (“Day of the Flowers”) – was chosen by Metal-Corbin to give the dance its thematic design. The song, like the dance she adapted from it, tells of a holiday when people go to a river to cleanse themselves with water and flowers as an act of atonement and plea for forgiveness. According to Rusmir, the song and dance reflect Bosnians’ forgiving nature.

The executive council building burns after being hit by artillery fire in Sarajevo May 1992; Ratko Mladić with Army of Republika Srpska officers; a Norwegian UN soldier in Sarajevo. |

“What is very hard about the war is that we lost so many friends. We lost neighbors. We lost family members. And for what? Really for nothing. We tried to keep Bosnia in Bosnian borders. But I can forgive,” Rusmir says, “because my wife and kids are alive. My father is alive. It’s time for forgiveness, for one reason – the war must stop, always, I cannot live with hate. My people are not like that. You can kick me, you can beat me…I will always find a reason to forgive you. That is the Bosnian soul.”

Hari, though, cannot so easily let go of the memory of Marina and their two children barely escaping a direct artillery hit on their Sarajevo apartment. “Forgive, yes, but forget, no,” he says. “I must try never to forget.” Even now, the whine of a siren and the clap of thunder are nervous reminders of incoming artillery rounds. “That is the kind of sound you can never forget,” Hari says.

He still wakes up in a cold sweat at the thought of the three-finger sign used by Chetnik Serbs in carrying out their terror campaigns. “When they started to use that sign,” he says, “the poison came. It meant. ‘You are not with us.’ Then the killing started.”

As a haunting reminder of what the dance was about, an enlarged news photo in the background pictured the tearful reunion of a Bosnian refugee family. The image had special meaning for Rusmir and Hari, who had only recently reunited with their own families. For them, the dance was their own personal commemoration of loss, celebration of survival, offering of thanks and granting of forgiveness.

Adding further resonance, virtually the entire local Bosnian refugee colony attended out of a deep communal sense of pride in their rich culture, one they’re eager to share with the wider Omaha community they’ve felt so welcomed by.

©photo by Quinn M. Corbin

Josie Metal-Corbin and her husband David Corbin

Zorana was there. “I was real proud, but at the same time I was kind of sad,” she says. “It was the music of our country – but in a different country. I was real touched when I saw Americans feel the same we do. I wanted to cry.”

Zorana, whose journey with her children across the war-torn region took a year before she found safe passage to America, adds that forgiveness must never come at the price of wisdom. “I would not let anybody to that to us again. Yo can trick us one time, but just one time.”

Yes, these Bosnians, are remarkably free of bitterness, but they do feel betrayed by the European community’s delayed, timid intervention. Zorana says, “You cannot wait so long and be so passive. You cannot say, ‘Oh, this is not my war. I don’t want to be bothered – they’re not killing me.’ Because tomorrow they may come to your house and try to kill you.” Hari says, “All the time we waited for a miracle.”

Rusmir decries the Serbs’ targeting of civilians. Hari hopes “world justice catches the war criminals, so that they will never sleep good again.”

New Pioneers

With the aid of Neb.Republican U.S. House of Representatives member John Christensen, Rusmir finally got permission to immigrate and was reunited with his family last November. Once here there were many adjustments to make. Igor didn’t remember him. Ida was slow to warm to a father she hadn’t seen for so long. Rusmir spoke no English. The family barely got by. But in classic immigrant tradition they’ve adapted and now call Omaha – a city they’d never heard of before – their home.

“It is hard. But step by step, day by day, we make connections, we make new friends we make a good life, too. We feel like Bosnian pioneers in Omaha and Nebraska,” says Rusmir, who hopes to start a construction business with Hari.

The Bosnians like America and feel sure they’ll thrive here. Their children already have, with many earning top grades in school. Ida and Lana are both healthy and doing fine. The Bosnians are deeply grateful to America, which Hari calls “a dream country” for its warm reception.

Hari says, “In America I can once again live like a normal person. There’s no fear that somebody will knock on my door and ask, ‘Who are you?’ and say, ‘You’re guilty.’ We are safe here. Many Americans have helped to give us a chance. Thanks America. We are sure that we will be a success.”

Zorana downplays their heroic struggle, saying, “You need to go on if you think ou have some tomorrow. You need to believe in yourself. Then nothing is impossible.”

America is, after all, the land of opportunity.

“You give me a chance to be equal,” she says. “To work. To be a citizen. I wanted my children to be Bosnian, but now I want them to be American. Here, you can be proud of your last name. You don’t have to feel ashamed.”

Related articles

- A Long Way from Home (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Mladic could face two trials for alleged Bosnian war crimes (cnn.com)

- Serbia alert over Mladic protests (bbc.co.uk)

- Bosnia tensions live on despite Mladic capture (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Key dates and events in the Bosnia war (zokstersomething.wordpress.com)

- No closure (bbc.co.uk)

A Long Way from Home: Two Kosovo Albanian families escape hell to start over in America

This story from a decade ago or so is one of two I have done that try to paint a human, intimate portrait of the late 20th century European wars that erupted in the aftermath of the end of Communist rule, when generations of long-simmering ethnic hatred spilled over in the power grabs that ensued. The following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) portrays the journey of two Kosovo Albanian families escaping the chaos and horror of war in their homeland to starting new lives in America. The second story along these lines, which I will be posting soon, tells a similar journey, only of a Bosnian family. There were numerous atrocities to go around in these wars, and on both sides, but the sad truth of the matter is that every day men, women, and children like the people I write about got caught up in the carnage. The result: untold hundreds of thousands dead and injured; broken societies and families; hatred that perpetuates from one generation to the next; retaliation attacks; refugee cultures; and the recipe for ongoing tensions that will only continue flaring until there is true reconciliation. The related articles below indicate the region is still a cauldron of unrest.

A Long Way from Home: Two Kosovo Albanian families escape hell to start over in America

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Uprooted

Among the mass exodus of ethnic Albanians fleeing their embattled native Kosovo last year were two young couples who met in a refugee camp and ended up starting new lives together in Omaha. Gazmend and Fortesa Ademi and Basri and Valbona Jashari left Kosovo during the March-May 1999 NATO bombing campaign targeting Serbian military strongholds.

With Serb troops ousted and NATO peacekeepers in their place, many refugees returned to the ravaged province. The couples, however, opted for asylum in America. After arriving here July 1 under the auspices of a humanitarian agency, they lived five weeks with their Bellevue sponsors, the Theresa and Richard Guinan family, whose parish — St. Bernadette Catholic Church — lent aid. The Kosovars, who today share a unit in the Applewood Pointe Apartments near 96th & Q Streets, are now first-time parents: the Ademis of a 5-month-old boy, Eduard, and the Jasharis of a 3-month-old girl, Elita.

Last August, Basri Jashari’s sister, Elfeti, her husband and their five children moved to Omaha (sponsored by Kountze Memorial Church). Another 59 Kosovars settled in Lincoln. The U.S. State Department reports some 14,000 Kosovars found asylum in America. Of the more than 800,000 refugees who fled the province, most have gone home, including some who came to Nebraska.

War may have been the catalyst for Kosovo Albanians’ leaving their homeland, but the events prompting their expulsion are rooted in long-standing ethnic conflict. During a recent interview at their apartment, Gazmend Ademi and Basri Jashari told, in broken English, their personal odyssey into exile. As the men spoke, sometimes animatedly, their wives listened while tending to their babies.

Only in their early 20s, the Kosovars exhibit a heavy, world-weary demeanor beyond their years. They carry the burden of any refugee: being apart from the people and culture they love. With a patriotic Albanian song playing in the background (“the music, it gives us power to live…to go on,” Ademi said) and defiance burning in their eyes, the men lamented all they have lost and left behind and expressed enmity for Serb aggressors who threw their lives into turmoil.

“We never wanted what happened. We never wanted this. THEY wanted the war. It’s like old Albanian men used to say, ‘Don’t ever trust the Serbs. They don’t keep their word,’” Ademi said. Do the refugees hate the Serbs? “No, I just don’t like them,” Jashari said, adding, “I know not every Serbian was guilty. But I still hate the cops.”

Aside from bitterness, sadness consumes them. Ademi said, “Sometimes I stop and think, Why do I have to go through all these things? It’s just too much. I miss my family. I miss my friends. I miss everything in Kosovo. That’s why I’ll go back. But, for now, things are still bad there. Many people have no work, no homes. What the Serbs couldn’t take they destroyed. When I speak to my friends by phone they all tell me to stay where I am.” Or, as Jashari simply put it, “It’s better here.”

Watch Out for the Dark

Conflicts between ethnic Albanians and Serbs were part of the uneasy landscape Ademi and Jashari grew up in. Born and raised in southeastern Kosovo cities 40 kilometers apart, the two came of age in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the ugly rhetoric of Slobodan Milosevic’s Serb nationalism turned openly hostile. Serb aggression in Bosnia erupted into full-scale war that United Nations forces helped quell. Although ethnic Albanians comprised the vast majority of Kosovo, Serbs controlled key institutions, most tellingly the police and military, which became oppressive occupying forces.

Ademi and Jashari say police routinely interrogated and arrested people without cause, extorting payment in return for safe passage or release. The harassment didn’t always end there. “For just a little thing they could arrest you or beat you or kill you. If they stopped you and demanded money, and you didn’t pay, your car was gone or you were gone,” Jashari said. “You had to pay,” Ademi said.

As Milosevic pressed for a Greater Serbia, life became more restrictive for ethnic Albanians (schools were closed and the display and teaching of Albanian heritage banned), whose Muslim culture contrasted with Serb Orthodox Christianity. The Ademis and Jasharis received much of their education in makeshift schools housed in basements and cellars. When young ethnic Albanians began fleeing Kosovo to avoid military service in the raging Balkans War, a moratorium on passports was enacted. Freedom could be bought, with a bribe, but most Kosovars could not afford it. Ademi, a bartender, and Jashari, a university student, faced bleak prospects. Jobs were scarce and those available paid low wages, yet prices for goods and services remained high. Bartering and blackmarket trading prevailed.

The start of the Kosovo War is generally agreed upon as March 23, 1998, when a Serb police action ended in the massacre of some 50 civilians and ignited the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) to escalate its armed resistance. However, for rank and file ethnic Albanians “the war started much earlier,” Jashari said. As early as 1989 the Serb political-military machine tightened its noose around Kosovo. Ademi and Jashari say they witnessed friends beaten by cops. Ademi said a cousin was held and tortured for days in a police station without legal counsel.

At mass demonstrations he recalls police firing tear-gas, even bullets, into crowds. Once, he said, a cop guarding a train load of tanks drew his weapon on he and some friends taking a short cut through a rail yard. In such a climate, once carefree days spent playing soccer or shopping in open air markets were replaced by caution. Nights were most ominous, with the Black Hand, a secret police/paramilitary force, roaming the streets. “After the dark would come, people who were out on the streets were taken away. Many were killed. Everybody was afraid from here,” Ademi said, clutching his chest. “Walking home every night I was afraid what might happen. I didn’t know if I was going to make it back. If you saw a car coming you turned back into the road and stayed until it passed. When they passed, you were like, ‘Whew, I made it okay.’”

Amid brutal police tactics and outright terrorist acts, the KLA began striking back with savage retaliatory attacks of its own, which led to Serb reprisals. When entreaties and threats by the U.N., the European Union and the West failed to get Milosevic to back down, a controversial U.S.-led NATO military response followed.

A Taste of Freedom

The night of the first air strikes prompted celebrations.