Archive

Tom Lovgren, A Good Man to Have in Your Corner

In the course of developing boxing stories over the years I met the subject of this story, Tom Lovgren, who at one time or another was involved in about every aspect of the fight game. He’s still a passionate fan of the sport today and is the unofficial historian and expert on boxing in Nebraska. Tom is one of those plain talking, call-it-like-is sorts, and I love him for it. He’s also a good storyteller, and his rich experiences in the prizefighting community provide him with plenty of material. Prior to profiling Tom, he was a source for me on several boxing pieces I did, including profiles on Ron Stander, a once Great White Hope who was billed as the “Bluffs Butcher.” Lovgren was in the Stander camp when Stander fought Joe Frazier for the world heavyweight title in Omaha in 1972, still the biggest boxing event in the city’s history. You’ll find my Stander pieces on this site. Tom also contributed to stories I did on Morris Jackson, Harley Cooper, the Hernandez Brothers, Kenny Wingo, the Downtown Boxing Club, and Dr. Jack Lewis. all of which can also be found on this blog. My story about Tom originally appeared in the New Horizons.

Tom Lovgren, A Good Man to Have in Your Corner

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

During one spring night in 1972, Omaha, Neb. became the center of the professional boxing world. A record Omaha fight night crowd of 9.863 jammed the Civic Auditorium to witness the May 25 heavyweight title bout between the challenger, local favorite Ron “The Bluffs Butcher” Stander, and the popular champion, “Smokin’” Joe Frazier. A gallery of veteran boxing reporters covered the event. Film cameras fed the action to a national syndicated TV audience. Canadian heavyweight champ George Chuvalo did the color commentary. Area dignitaries and sports celebrities mingled in the electric crowd. Top heavyweight contender George Foreman looked fearsome at ringside. Legendary referee Zack Clayton appeared spiffy in his bow tie. Nervous Dick Noland ran the Stander corner while his counterpart, the sage-like Yank Durham, led the Frazier contingent.

In terms of sheer impact, the fight remains arguably the biggest sporting event ever held in Omaha. The allure of the heavyweight championship was enough that, with the title on the line, the results made headlines around the globe. And while Stander-Frazier does not rank highly in the annals of title bouts, it proved a smashing success, pulling in live gate receipts of nearly $250,000 in an era when tickets went for a fraction of today’s prices. For former Omaha boxing promoter and matchmaker Tom Lovgren, one of the men responsible for making the fight happen, it was the apex of a 20-year career that saw him put on fight cards featuring everyone from world-class boxers to journeymen pugs. A blunt man with a biting wit, Lovgren recalls a well-wisher that night praising him for pulling off such a coup, whereupon he quipped, “It’ll all be down hill from here.”

The sardonic Lovgren sat for a recent interview in his ranch-style Omaha home near Rosenblatt Stadium and explained his seeming pessimism the night of his crowning feat. “What I meant by down hill was I’d been to the peak. What was the chance of developing another heavyweight in Omaha, Neb. who drew like Stander did and who could be ready to fight for a championship? It’s all got to work together. And that time it did. All the dreams came true. A lot of people talk about doing something like this, but a lot of stuff can go wrong. A guy can get cut in training camp. Tempers can flare up and the whole deal get called off. With this situation, everything worked. It came off.” Proving himself a prophet, Stander-Frazier was indeed the one and only title fight he promoted.

At the time, Lovgren was a one-quarter partner in the recently formed Cornhusker Boxing Club, which staged most of Omaha’s top fight cards in the 1970s. Club president Dick Noland was Stander’s longtime manager. Noland and Lovgren were friends from the days when Lovgren was a correspondent for Ring Magazine. A Sheldon, Iowa native, Lovgren fell in love with boxing watching televised bouts as a kid. His short-lived amateur boxing career came to a halt at 16 when he got “dropped” three times in round one of a Golden Gloves bout. “It was at that point I decided, If you’re going to do anything in this game it’s going to have to be as something other than a boxer, because you obviously don’t have the talent it takes.”

Outside the ring, the University of Denver-educated Lovgren was a food services manager at many different stops, including Omaha’s Union Stockyards Company. Wherever he, his former school teacher wife, Jeaninne, and their four sons settled, Lovgren made it a point to acquaint himself with the area boxing scene — its gyms, fighters, managers, trainers — and to attend bouts. He often traveled 100 miles or more just to see a good fight.

He promoted his first fight card in Ohio, later detailing the highs and lows of that experience in an article he authored for Boxing Illustrated entitled, “So You Want to Be a Promoter?” His wife was skeptical about the promotion racket until he emptied his pockets after that first fight card and hundreds of dollars in gate receipts came tumbling out. Catching fights and filing stories around the Midwest helped him develop contacts among the boxing brotherhood. After contracting multiple sclerosis in 1970 Lovgren retired from the food services field, which gave him more time to feed his passion. Always the fighter, he’s not allowed MS to break his spirit, noting that managing the disease is a matter of “knowing what you can do and what you can’t do.”

When asked by Noland to join the Cornhusker Boxing Club, Lovgren jumped at the chance. Before teaming with Noland he had bailed-out the manager more than once by finding last-minute replacement opponents for Stander, whose reputation as a heavy hitter preceded him. “I was very good at coming up with fighters, and right now,” Lovgren said. “Good fighters, poor fighters, whatever it was, I would get those opponents. My strong suit was my ability to deliver a body. I knew a lot of people. I’d been a lot of places. I knew what talent was available.”

With Noland in charge of getting Stander fight-ready and Lovgren taking care of the business side of things, “The Bluffs Butcher” became their meal ticket. But getting Stander in shape was a daunting task given the fighter’s notoriously lax approach to training. “It was hard to get Ron enthusiastic about training,” Lovgren said. “There was no inner drive, no fire in the furnace, except for certain fights. I tried talking to him about it. I tried playing mind games with him. I did everything I could.” With his matchmaking acumen, Lovgren helped build Stander into a contender by putting him in “against the right guys at the right time to develop his skills.”

“He made some good fights for me,” recalls Stander, “Like the Ernie Shavers fight (a Stander KO victim). He got me in shape. We had a good time”

By the end of ‘71 Stander owned credentials for an inside track to a title shot. First, he was a Great White Hope. Second, as a short-armed slugger he played into Frazier’s smothering style. Third, he cut easily, reducing the chances the fight would go the distance and hazard a decision. Finally, he was a crowd-pleasing brawler with a knockout punch. A guy who, as Lovgren likes to phrase it, “put asses in seats,” guaranteeing a good gate. “Ron drew better than any fighter who ever fought in Omaha. There were guys with more talent, but Ron had the charisma that drew people like no one else. Some people came to see him win and some came to see him get beat. I didn’t care why they came, as long as they came.”

To ensure the chronically overweight Stander got fit, Lovgren moved him into his home for the fight. Training under Leonard Hawkins at the Fox Hole Gym in Omaha and under Johnny Dunn in Boston, Stander steeled himself. “Ron was a real fighter who asked no quarter and gave none. He backed away from no one and had no fear. He’d walk right into you. He was not going to be embarrassed,” Lovgren said.

In a confrontation that could have served as an inspiration for Rocky, Stander, the 10-1 underdog, showed admirable courage by standing toe-to-toe with the champ and exchanging haymakers. Despite taking a beating, he kept wading in until, bloodied and blinded by cuts, the fight was stopped after the 4th round. Still, there was a moment early on when the underdog appeared to rock the champ, even buckling his knees. “A lot of people say that Frazier slipped. He did, but he was hit with a shot by Stander and that’s why he staggered. Another time, Ronnie missed with an uppercut that was about that far away,” said Lovgren, holding his fingers about two inches apart. “If he landed that punch he may very well have been heavyweight champ of the world. That’s how close he was.”

Frazier retained his belt, only to lose it the very next fight to Foreman. Meanwhile, Stander got a one-way ticket back to Palookaville, where for another decade he toiled in obscurity as a club fighter whose main claim to fame was having got that one-in-a-million crack at immortality. Yet the fight that will forever link these two men almost didn’t come off when negotiations bogged down over money. “Frazier’s Philadelphia lawyers sent us a couple proposals and we turned them down because there wasn’t any money for us. Until the contracts were squared away to where we were going to make some money, that fight was not going to happen,” Lovgren said. “Then, television got involved and all of a sudden there was money enough for everybody.” With the bout confirmed, Omaha took center stage in the big time boxing arena. “Once the word was out that this title fight was on, everybody from the world of boxing was there. Everything you wanted was possible. Everybody wanted something. That’s how it is.”

Besides promoting Stander fights, he showcased the fighting Hernandez brothers (Art, Ferd, Dale) of Omaha. He considers long retired welterweight contender Art Hernandez the best fighter, pound-for-pound, the city has produced. He also organized cards featuring such top-ranked imported talent as Sean O’Grady, Lennox Blackmore and Jimmy Lester.

In his career, he saw it all — from guys taking dives to being handed bad decisions to getting “beat within a whisker of their life.” When it’s suggested boxing suffers a black eye due to mercenary, deceitful practices, he sharply replies, “Do I think there are crooks in boxing? Yes. Did I ever deal with any? Yeah, I probably did. I’ve heard a lot of bad stories, but every time I dealt with Mr. Boxing types, and I did a lot, they delivered the product and were straight down the line with me.” He feels a few unsavory elements sully the image of an otherwise above-board sport. “Anybody who ever fought for me got paid. If I said you were going to get $100, you got $100. I paid what I thought was the going rate for a 4-rounder or whatever it was, and that meant you got paid whether there was one person in the auditorium or whether the auditorium was full. If you’re going to play the game, you better be able to afford it.”

Stander said Lovgren has always owned his trust and respect. “Tom always took good care of me. You could count on him right to the end, every bit of the way. He’s just a stand-up guy. Straight as an arrow. His word is as solid as a rock, as good as gold. I love the guy.”

Because all manner of things can cause a fighter to drop out of a scheduled match, a savvy promoter like Lovgren must be able to improvise at a moment’s notice. “Once, I had a couple fighters pull out the night of the fight. These two guys that trained at a local gym had come to watch, and I went up to them and said, ‘Hey, you’re here, you can fight. You guys don’t have to kill each other — just go out and put on a good show, and I’ll pay ya.’ So, they fought an exhibition. Does that kind of thing happen? Yes. Often? Yes. Too often? Yes.”

Lovgren, who’s aimed his cutting remarks at referees, judges and athletic officials, makes no bones about the fact his frank style rubs some people the wrong way. “If you took a poll of all the boxing people in Omaha I wouldn’t make the Top 10 friendliest guys, but you’ve got to have people’s respect” and that means speaking your mind and stepping on some toes. Venerable Omaha amateur boxing coach Kenny Wingo, who’s worked alongside Lovgren organizing the Golden Gloves, admires his friend’s penchant for “telling it like it is,” adding: “He’s very opinionated and he’s a little rough around the edges. He takes no prisoners. He runs everything with an iron fist. But if he tells you something, you can take it to the bank. He’s honest. He’s got quite a history in the boxing world and he’s done a lot of good things for the sport along the way.”

If Lovgren leaves any legacy, it will be his role in bringing off Stander-Frazier, an event whose like may not be seen here again. Since retiring as a promoter in the early 1980s, this self-described “serious student” of The Sweet Science has continued his love affair with the sport by organizing his vast collection of boxing memorabilia (books, magazines clippings, tapes, wire service photos) and by writing a pair of boxing histories. The first, which he self-published, chronicles the life and times of Ron Stander, with whom he’s remained close friends. The second, which he just started, details the career of Art Hernandez, a man who fought five world champions and, in retirement, lost part of a leg following a fall at his home. The materials and histories are his attempt at preserving a record of local ring greats.

Like most passions, once boxing gets in your blood, it never leaves you. Even if many of the gyms, watering holes and ringside characters he knew are now gone, Lovgren still closely follows the sport. “You never get out of the game,” he said.

Related Articles

- For Better or Worse…..Old versus New (yougabsports.com)

- The killer instinct in boxing (trueslant.com)

- 40 Years Later, Ali-Frazier Still An MSG Classic (newyork.cbslocal.com)

- Happy Birthday To The Greatest: 10 Best Moments In Muhammad Ali’s Career (bleacherreport.com)

- Trainer Gil Clancy, 88, guided Emile Griffith to world title (thestar.com)

Don Benning: Man of Steel (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Don Benning: Man of Steel (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Wrestling is a proving ground. In an ultimate test of will and endurance, the wrestler first battles himself and then his opponent until one is left standing with arms raised overhead in victory. In a life filled with mettle-testing experiences both inside and outside athletics, Don Benning has made the sport he became identified with a personal metaphor for grappling with the challenges a proud, strong black man like himself faces in a racially intolerant society.

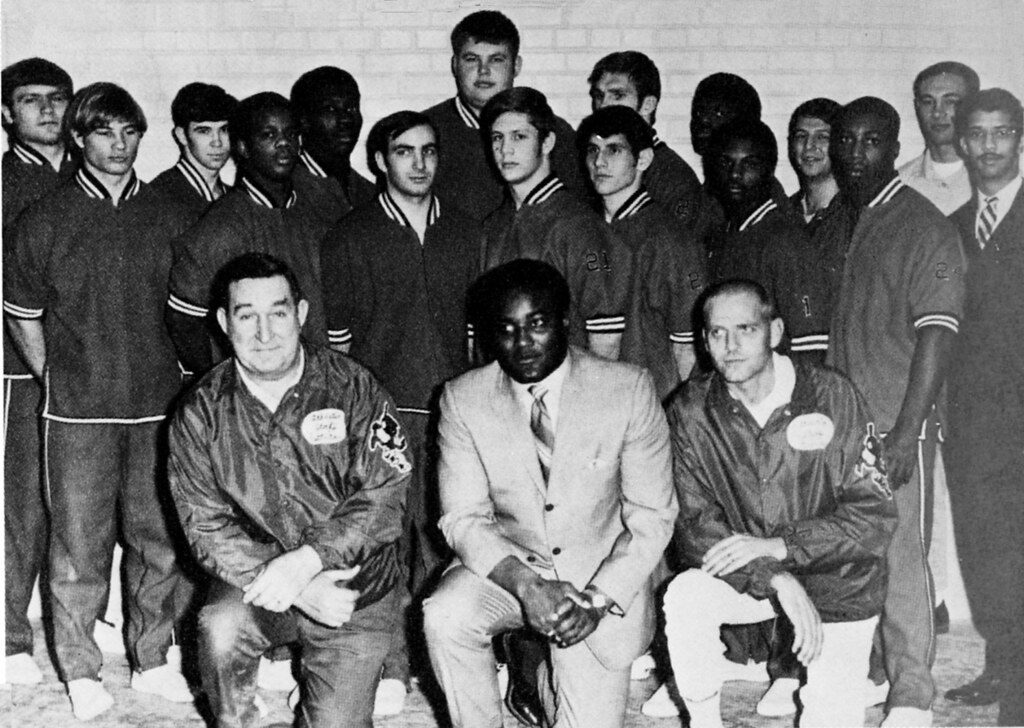

A multi-sport athlete at North High School and then-Omaha University (now UNO), the inscrutable Benning brought the same confidence and discipline he displayed as a competitor on the mat and the field to his short but legendary coaching tenure at UNO and he’s applied those same qualities to his 42-year education career, most of it spent with the Omaha Public Schools. Along the way, this man of iron and integrity, who at 68 is as solid as his bedrock principles, made history.

At UNO, he forged new ground as America’s first black head coach of a major team sport at a mostly white university. He guided his 1969-70 squad to a national NAIA team championship, perhaps the first major team title won by a Nebraska college or university. His indomitable will led a diverse mix of student-athletes to success while his strong character steered them, in the face of racism, to a higher ground.

When, in 1963, UNO president Milo Bail gave the 26-year-old Benning, then a graduate fellow, the chance to he took the reins over the school’s fledgling wrestling program, the rookie coach knew full well he would be closely watched.

“Because of the uniqueness of the situation and the circumstances,” he said, “I knew if I failed I was not going to be judged by being Don Benning, it was going to be because I was African-American.”

Besides serving as head wrestling coach and as an assistant football staffer, he was hired as the school’s first full-time black faculty member, which in itself was enough to shake the rafters at the staid institution.

“Those old stereotypes were out there — Why give African-Americans a chance when they don’t really have the ability to achieve in higher education? I was very aware those pressures were on me,” he said, “and given those challenges I could not perform in an average manner — I had to perform at the highest level to pass all the scrutiny I would be having in a very visible situation.”

Benning’s life prepared him for proving himself and dealing with adversity.

“The fact of the matter is,” he said, “minorities have more difficult roads to travel to achieve the American Dream than the majority in our society. We’ve never experienced a level playing field. It’s always been crooked, up hill, down hill. To progress forward and to reach one’s best you have to know what the barriers or pitfalls are and how to navigate them. That adds to the difficulty of reaping the full benefits of our society but the absolute key is recognizing that and saying, ‘I’m not going to allow that to deter me from getting where I want to get.’ That was already a motivating factor for me from the day I got the job. I knew good enough wasn’t good enough — that I had to be better.”

Shortly after assuming his UNO posts his Pullman Porter father and domestic worker mother died only weeks apart. He dealt with those losses with his usual stoicism. As he likes to say, “Adversity makes you stronger.”

Toughing it out and never giving an inch has been a way of life for Benning since growing up the youngest of five siblings in the poor, working-class 16th and Fort Street area. He said, “Being the only black family in a predominantly white northeast Omaha neighborhood — where kids said nigger this or that or the other — it translated into a lot of fights, and I used to do that daily. In most cases we were friends…but if you said THAT word, well, that just meant we gotta fight.”

Despite their scant formal education, he said his parents taught him “some valuable lessons scholars aren’t able to teach.” Times were hard. Money and possessions, scarce. Then, as Benning began to shine in the classroom and on the field (he starred in football, wrestling and baseball), he saw a way out of the ghetto. Between his work at Kellom Community Center, where he later coached, and his growing academic-athletic success, Benning blossomed.

“It got me more involved, it expanded my horizons and it made me realize there were other things I wanted,” he said.

But even after earning high grades and all-city athletic honors, he still found doors closed to him. In grade school, a teacher informed him the color of his skin was enough to deny him a service club award for academic achievement. Despite his athletic prowess Nebraska and other major colleges spurned him.

At UNO, where he was an oft-injured football player and unbeaten senior wrestler, he languished on the scrubs until “knocking the snot” out of a star gridder in practice, prompting a belated promotion to the varsity. For a road game versus New Mexico A&M he and two black mates had to stay in a blighted area of El Paso, Texas — due to segregation laws in host Las Cruces, NM — while the rest of the squad stayed in plush El Paso quarters. Terming the incident “dehumanizing,” an irate Benning said his coaches “didn’t seem to fight on our behalf while we were asked to give everything for the team and the university.”

Upon earning his secondary education degree from UNO in 1958 he was dismayed to find OPS refusing blacks. He was set to leave for Chicago when Bail surprised him with a graduate fellowship (1959 to 1961). After working at the North Branch YMCA from ‘61 to ‘63, he rejoined UNO full-time. Still, he met racism when whites automatically assumed he was a student or manager, rather than a coach, even though his suit-and-tie and no-nonsense manner should have been dead giveaways. It was all part of being black in America.

To those who know the sanguine, seemingly unflappable Benning, it may be hard to believe he ever wrestled with doubts, but he did.

“I really had to have, and I didn’t know if I had it at that particular time, a maturity level to deal with these issues that belied my chronological age.”

Before being named UNO’s head coach, he’d only been a youth coach and grad assistant. Plus, he felt the enormous symbolic weight attending the historic spot he found himself in.

“You have to understand in the early 1960s, when I was first in these positions, there wasn’t a push nationally for diversity or participation in society,” he said. “The push for change came in 1964 with the Civil Rights Act, when organizations were forced to look at things differently. As conservative a community as Omaha was and still is it made my hiring more unusual. I was on the fast track…

“On the academic side or the athletic side, the bottom line was I had to get the job done. I was walking in water that hadn’t been walked in before. I could not afford not to be successful. Being black and young, there was tremendous pressure…not to mention the fact I needed to win.”

Win his teams did. In eight seasons at the helm Benning’s UNO wrestling teams compiled an 87-24-4 dual mark, including a dominating 55-3-2 record his last four years. Competing at the NAIA level, UNO won one national team title and finished second twice and third once, crowning several individual national champions. But what really set UNO apart is that it more than held its own with bigger schools, once even routing the University of Iowa in its own tournament. Soon, the Indians, as UNO was nicknamed, became known as such a tough draw that big-name programs avoided matching them, less they get embarrassed by the small school.

The real story behind the wrestling dynasty Benning built is that he did it amid the 1960s social revolution and despite meager resources on campus and hostile receptions away from home. Benning used the bad training facilities at UNO and the booing his teams got on the road as motivational points.

His diverse teams reflected the times in that they were comprised, like the ranks of Vietnam War draftees, of poor white, black and Hispanic kids. Most of the white athletes, like Bernie Hospodka, had little or no contact with blacks before joining the squad. The African-American athletes, empowered by the Black Power movement, educated their white teammates to inequality. Along the way, things happened — such as slights and slurs directed at Benning and his black athletes, including a dummy of UNO wrestler Mel Washington hung in effigy in North Carolina — that forged a common bond among this disparate group of men committed to making diversity work in the pressure-cooker arena of competition.

“We went through a lot of difficult times and into a lot of hostile environments together and Don was the perfect guy for the situation,” said Hospodka, the 1970 NAIA titlist at 190 pounds. “He was always controlled, always dignified, always right, but he always got his point across. He’s the most mentally tough person you’d ever want to meet. He’s one of a kind. We’re all grateful we got to wrestle for Don. He pushed us very hard. He made us all better. We would go to war with him anytime.”

Brothers Roy and Mel Washington, winners of five individual national titles, said Benning was a demanding “disciplinarian” whom, Mel said, “made champions not only on the mat but out there in the public eye, too. He was more than a coach, he was a role model, a brother, a father figure.” Curlee Alexander, 115-pound NAIA titlist in 1969 and a wildly successful Omaha prep wrestling coach, said the more naysayers “expected Don to fail, the more determined he was to excel. By his look, you could just tell he meant business. He had that kind of presence about him.”

Away from the mat, the white and black athletes may have gone their separate ways but where wrestling was concerned they were brothers rallying around their perceived identity as outcasts from the poor little school with the black coach.

“It’s tough enough to develop a team to such a high skill level that they win a national championship if you have no other factors in the equation,” Benning said, “but if you have in the equation prejudice and discrimination that you and the team have to face then that makes it even more difficult. But those things turned into a rallying point for the team.

“The white and black athletes came to understand they had more commonalities than differences. It was a sociological lesson for everyone. The key was how to get the athletes to share a common vision and goal. We were able to do that. The athletes that wrestled for me are still friends today. They learned about relationships and what the real important values are in life.”

His wrestlers still have the highest regard for him and what they shared.

“I don’t think I could have done what I did with anyone else,” Hospodka said. “Because of the things we went through together I’m convinced I’m a better human being. There’s a bond there I will never forget.” Mel Washington said, “I can’t tell you how much this man has done for me. I call him the legend.” The late Roy Washington, who changed his name to Dhafir Muhammad, said, “I still call coach for advice.” Alexander credits Benning with keeping him in school and inspiring his own coaching/teaching path.

After establishing himself as a leader Benning was courted by big-time schools to head their wrestling and football programs. Instead, he left the profession in 1971, at age 34, to pursue an educational administration career. Why leave coaching so young? Family and service. At the time he and wife Marcidene had begun a family — today they are parents to five grown children and two grandkids — and when coaching duties caused him to miss a daughter’s birthday, he began having second thoughts about the 24/7 grind athletics demands.

Besides, he said, he was driven to address “the inequities that existed in the school system. I thought I could make a difference in changing policies and perhaps making things better for all students, specifically minority students. My ultimate goal was to be superintendent.”

Working to affect change from within, Benning feels he “changed attitudes” by showing how “excellence could be achieved through diversity.” During his OPS tenure, he operated, just like at Omaha University, “in a fish bowl.” Making his situation precarious was the fact he straddled two worlds — the majority culture that viewed him variously as a token or a threat and the minority culture that saw him as a beacon of hope.

But even among the black community, Benning said, there was a militant segment that distrusted one of their own working for The Man.

“You really weren’t looked upon too kindly if you were viewed as part of the system,” he said. “On the other side of it, working in an overwhelmingly majority white situation presented its own particular set of challenges.”

What got him through it all was his own core faith in himself. “Evidently, some people would say I’m a confident individual. A few might say I’m arrogant. I would say I’m highly confident. I can’t overemphasize the fact you have to have a strong belief in self and you also have to realize that a lot of times a leader has to stand alone. There are issues and problems that set him or her apart from the crowd and you can’t hide from it. You either handle it or you fail and you’re out.”

Benning handled it with such aplomb that he: brought UNO to national prominence, laying the foundation for its four-decade run of excellence on the mat; became a distinguished assistant professor; and built an impressive resume as an OPS administrator, first as assistant principal at Central High School, then as director of the Department of Human-Community Relations and finally as assistant superintendent.

During his 26-year OPS career he spearheaded Omaha’s smooth desegregation plan, formed the nationally recognized Adopt-a-School business partnership and advocated for greater racial equity within the schools through such initiatives as the Minority Intern Program and the Pacesetter Academy, an after school program for at-risk kids. Driving him was the responsibility he felt to himself, and by extension, fellow blacks, to maximize his and others’ abilities.

“I had a vision and a mission for myself and I set about developing a plan so I could reach my goal, and that was basically to be the best I could be. As a coach and educator what I have really enjoyed is helping people grow and reach their potential to be the best they can be. That’s my goal, that’s my mission, and I try to hold to it.”

His OPS career ended prematurely when, in 1997, he retired after being snubbed for the district’s superintendency and being asked by current schools CEO John Mackiel to reapply for the assistant superintendent’s post he’d held since 1979. Benning called it “an affront” to his exemplary record and longtime service.

About his decision to leave OPS, he said, “I could have continued as assistant superintendent, but I chose not to because who I am and what I am is not negotiable.” A critic of neighborhood schools, he did not bend on a practice he deems detrimental to the quality of education for minorities. “I compromised on a lot of things but not on those issues. The thing I’ve tried not to do, and I don’t think I have, is negotiate away my integrity, my beliefs, my values.”

Sticking to his guns has exacted a toll. “I’ve battled against the odds all my life to achieve the successes I have and there’s been some huge prices to pay for those successes.”

Curlee Alexander

His unwavering stances have sometimes made him an unpopular figure. His staunch loyalty to his hometown has meant turning down offers to coach and run school districts elsewhere. His refusal to undermine his principles has found him traveling a hard, bitter, lonely road, but it’s a path whose direction is true to his heart.

“I found out long ago there were things I would do that didn’t please every one and in those types of experiences I had to kind of stand alone or submit. I developed a strong inner being where I somewhat turned inward for strength. I kind of said to myself, I just want to do what I know to be right and if people don’t like it, well, that’s the way it is. I was ready to deal with the consequences. That’s the personality I developed from a very young age.”

Those who’ve worked with Benning see a man of character and conviction. Former OPS superintendent Norbert Schuerman described him as “proud, determined, disciplined, opinionated, committed, confident, political,” adding, “Don kept himself very well informed on major issues and because he was not bashful in expressing his views, he was very helpful in sensitizing others to race relations. His integrity and his standing in the community helped minimize possible major conflicts.”

OPS Program Director Kenneth Butts said, “He’s a very principled man. He’s very demanding. He’s very much about doing what is right rather than what is politically expedient. He cares. He’s all about equity and folks being treated fairly.”

After the flap with OPS Benning left the job on his own terms rather than play the stooge, saying, “The Omaha Public Schools situation was a major disappointment to me…To use a boxing analogy, it staggered me, but it didn’t knock me down and it didn’t knock me out. Having been an athlete and a coach and won and lost a whole lot in my life I would be hypocritical if I let disappointment in life defeat me and to change who I am. I quickly moved on.”

Indeed, the same year he left OPS he joined the faculty at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he is coordinator of urban education and senior lecturer in educational administration in its Teachers College. In his current position he helps prepare a new generation of educators to deal with the needs of an ever more diverse school and community population.

Even with the progress he’s seen blacks make, he’s acutely aware of how far America has to go in healing its racial divide.

“This still isn’t a color-blind society. I don’t say that bitterly — that’s just a fact of life. But until we resolve the race issue, it will not allow us to be the best we can be as individuals and as a country,” he said.

As his own trailblazing cross-cultural path has proven, the American ideal of epluribus unum — “out of many, one” — can be realized. He’s shown the way.

“As far as being a pioneer, I never set out to be a part of history. I feel very privileged and honored having accomplished things no one else had accomplished. So, I can’t help but feel that maybe I’ve made a difference in some people’s lives and helped foster inclusiveness in our society rather than exclusiveness. Hopefully, I haven’t given up the notion I still can be a positive force in trying to make things better.”

Related Articles

- Coaching diversity slowly rising at FBS schools (thegrio.com)

- University regents approve Nebraska-Omaha’s D-I move (sports.espn.go.com)

- UNO Wrestling Dynasty Built on a Tide of Social Change (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

The Fighting Hernandez Brothers

Another of my boxing stories is featured here, this time about a family of fighters, the Hernandez brothers. It’s a story of overcoming odds, winning great victories, enduring brutal losses, experiencing tragic events, and, where possible, keeping on despite all the blows. Rarely has a single family produced as many good boxers as this one did, but as the story goes into, there was a price to be paid. The article originally appeared in a paper that no loner exists, the Omaha Weekly. Boxing seems to give journalists license to take a more literary approach and I pulled out all the stops in this one.

NOTE: The Hernandez brother who was perhaps the most accomplished in the ring, Art Hernandez, passed away recently. He was a world-ranked contender for a time, holding his own with some tough hombres. He once fought an aging but still dangerous Sugar Ray Robinson to a disputed draw in Omaha. Most observers felt Art should have been given the decision.

The Fighting Hernandez Brothers

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Omaha Weekly

Armed with fists of fury and cajoles of brass, the Fighting Hernandez brothers strode into town from the sun-baked Panhandle to whip nearly all comers in Omaha ring events from the late 1950s through the mid-1970s. Ferd, Art and Dale Hernandez each left their mark on the amateur and professional boxing scene, not only here, but regionally and nationally as well. The brothers’ lives inside the ropes were filled with more than the usual pugilistic triumph and failure. Three of them achieved Top 10 rankings — Dale as a lightweight and both Ferd and Art as middleweights. They fought all over the globe. They crossed gloves with several world champions, including some legends. They held titles. They got robbed of some decisions. An injury ended the career of one. A bad beating spelled the beginning of the end for another. A fourth brother, Chuck, never really had the heart for boxing and quit after a brief and uneventful career.

Life outside the ring has also held more than its share of highs and lows. There have been wives, girlfriends, kids, breakups. Separated by a year in age and quite a bit older than their male siblings, Ferd and Art were fast buddies and, by all accounts, bad influences on each other — indulging in vices that fighters-in-training are supposed to avoid. “We had too much fun together,” Art said from the south Omaha home he shares with his wife, Mary, and their children. “We were bad — that’s for sure. I guess we had no will power.” He said things got so bad even his big brother realized it was best if he moved on. “He knew that if we were together we wouldn’t be right, so he went west. The greatest thing he ever did for himself and for me was to get the hell out of town.” Ferd went to Las Vegas of all places.

After compiling a 35-10-3 record as a pro, Ferd incurred a detached retina that forced him to retire early at age 33. He stayed on in Vegas, becoming a main event referee, a straight man in the “Minsky’s Burlesque” show at the Aladdin and a casino bartender, before contracting liver disease that killed him at 57. Art finished with a 44-20-2 pro mark. In his post-boxing life he worked the security detail at Douglas County Hospital, often responding to calls in the psyche ward, before becoming chief of security. A freak accident in 1997 led to his left leg’s amputation. Dale, the hardest puncher of the bunch, slugged his way to a 37-6 pro record, but his disdain for training led him to quit before ever maxing-out his ability. A trucker by trade, Dale has spent the last several years in and out of prison for assault. Today, he is persona non grata with his surviving brothers.

Born in Minatare, Neb., Art and Ferd moved with their family to Sidney, where the Hernandez boys were weaned on The Sweet Science by their father, Perfecto “Pete,” a former glove man himself. The old man worked his sons hard. For Perfecto, now caring for his Alzheimer’s-stricken wife and the mother of his six children, Rebecca, in Cheyenne, Wyo., boxing was an art form whose object was skillfully avoiding being hit while laying leather on your opponent. “His thing about boxing was defense,” said Art, the only brother still living in-state and, according to some local ring observers, the best boxer, pound-for-pound, produced by Nebraska the past 40 years. “His philosophy was, ‘Hit, and don’t get hit.’ We just moved and moved and moved and threw a lot of jabs. He never yelled. He just told you exactly what you were doing wrong. ‘Throw more jabs, boy. Throw more upper cuts, boy.’ It was always, ‘boy.’”

From the time they were 5 and 6 years old, respectively, Art and Ferd were urged to scrap by the old man, who fashioned a makeshift ring at home and ran a gym Sidney boxing boosters built for him in town. “That’s where we learned everything that we knew. There were always fights,” is how Art describes those early years. “He had us sparring all the time. He was a great inspiration.” The two tykes became a kind of novelty opening act on local fight cards when their dad had them fight exhibition matches before regularly scheduled bouts. Art said that while definitely pushed into boxing, he genuinely liked the sport and only threatened quitting once under his father’s heavy hand, “but it never happened.”

As the brothers began dominating the junior boxing circuit, they quickly made names for themselves as tough little hombres. The Midwest Golden Gloves tournament, once a huge draw at the Civic Auditorium, became their personal showcase. They represented the southwest Nebraska district out of Scottsbluff. Art so outclassed the field he became the first fighter to win five Midwest Gloves titles and, after capturing his fifth, tourney officials told the then-19 year-old he was not welcome back. Ferd won two Midwest crowns and used the second as a springboard to do something his younger brother could not — win a national Golden Gloves championship (taking the 1960 welterweight division title in Chicago). Despite the brothers being virtually the same size, their father kept them in separate weight divisions for good reasons: one, to double the family’s chances at winning trophies and titles; and, two, to placate Mama Hernandez, who forbade her sons from ever fighting each other “for real.”

Fresh off his championship, Ferd, along with Art, competed for spots on the 1960 United States Olympic boxing team during tryouts in Pocatello, Idaho. At the tryouts Ferd lost in the finals and Art bowed out in the first round. While their bid for Olympic glory ended before it could begin, they scored a coup when Idaho State University boxing coach Dubby Holt, scouting prospects for his program, offered them scholarships. “He wanted a brother team and, so, we said, ‘Sure, why not?’ and we went there,” Art said. Things did not pan out for the pair in Pocatello, where they spent more time carousing than working, a pattern that played out over and over again whenever they teamed-up. Back home for Christmas break, Perfecto sized up his sons and determined while they were not cut out for school, they just might have the right stuff for prizefighting.

Art turned pro first, signing with Omaha promoter Lee Sloan, who acted as his manager and matchmaker. “When I turned pro, Sloan asked me, ‘Do you think you can be a world champion?’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘Well, then, you’re mine.’ That was a motivating thing my whole life.” He trained under the tutelage of veteran handler Sammy Musco, a former prizefighter. Musco refined his punching style. “When he first started training me, my left hook used to come all the way around, where his style of fighting was to stay in tight and just throw it with leverage. Just a real short punch. It worked all the time. He was a good trainer — no doubt about it. He’d make you work and make you work.”

Ferd entered the prizefighting arena a few months after Art’s debut. Once Art overcame those nagging doubts to resume his career, he and Ferd notched a few more wins under their belts. Then, according to local boxing historian and former matchmaker Tom Lovgren, their shared manager, Sloan, decided one or the other had to go. It seems the two were raising such hell together that, in Sloan’s view, they were holding each other back and, so, he decided to separate these modern Corsican Brothers. He reportedly asked a promoter friend to overmatch the boys, vowing to keep the one showing the most poise in defeat. The fights were made and, as expected, each lost. The verdict: Art stayed on, while Ferd left for Las Vegas, just then evolving into a hot fight market.

By the mid-60s the brothers’ careers began taking off — each emerging as middleweight contenders. Before long, they were fielding offers to fight each other. “Yeah, we had offers,” Art said. “Well, he was rated No. 2 and I was No. 3. I asked my dad what he thought about it and he said, ‘Hey, you’re in the game for money. If the money’s right, take it.’ But, you know, our mom said, ‘No,’ and that was it.” In 1964, a young, inexperienced but promising Art got his first brush with immortality when matched with six-time world champ Sugar Ray Robinson, by then in his 40s but, as the saying goes, possessing every trick in the book. When the fight was initially made, Hernandez admits he felt intimidated by the Robinson legend. “When my handlers first mentioned the fight I thought, ‘I’m going to be killed,’ but then as I was training I got in terrific shape and I thought, ‘Well, shit, I’ve got nothin’ to lose — I’ll give it all I got.’ Which I did.” A steamy Civic Auditorium was the site of the 10-rounder, which went the distance and ended in controversy when a cagey Robinson, sensing he was behind, twice hit Hernandez below the belt. No fouls were called, much to the fans’ dismay. “I’m sure he hit me below the belt intentionally, but…that’s the fight game, you know?” Hernandez said.

Most ringside observers gave the decision to Hernandez, but the judges scored the fight a draw. “I won that fight. There’s no doubt about it,” Hernandez said. “I boxed him superbly, and then he tried making a butt of me. He slipped a punch one time and spun a little bit and slapped me on the ass. It made the crowd laugh.” He said while Robinson was ring savvy, his arsenal had little else left. “He didn’t have real hard, sharp punches. It was mostly slapping stuff. He never hurt me.”

Mere months after that tussle, Hernandez’s manager, Sloan, died of a massive heart attack. “That broke my heart,” he said. For the next few years he fought for Dick Noland, also the manager of heavyweight Ron Stander, who often sparred with Hernandez at the old Fox Hole Gym and once said of his much smaller and more agile partner, “He’s harder to hit than a handful of rice.”

Ferd was at the Robinson fight and after seeing how well his kid brother performed he grew confident he too could trade leather with the best. He proved his point a year later by winning a split-decision over Sugar Ray at the Hacienda Hotel, among the venues Ferd headlined at during the “Strip Fight of the Week” cards his promoter, Bill Miller, founded. Although both brothers became top contenders in the middleweight division, neither ever got a title shot. Art always felt Ferd hampered his chances by letting his Las Vegas camp change his style from the pure boxing stratagem their father instilled to more of a close-in style ill-suited to him. “That was his downfall. Instead of moving and boxing and slipping punches, he became a come-in fighter. He got hit too much. Then, he got that detached retina (in 1968). It’s too bad…he was a terrific boxer.” As for himself, Art chalks up his lost opportunities to ring politics, bad breaks and stupid choices. In a career of what-might-have-beens, he was often only one win away from landing a championship bout, but could never quite close the deal.

Perhaps his biggest frustration came in a 1969 duel with former champ Emile Griffith, then still in his prime. Fought in Sioux Falls, S.D., the well-boxed bout went the full 10 rounds and, in a reversal of popular opinion, Griffith was given a split decision. “The fight was a good fight,” Hernandez recalled. “I loved it. He was well-versed in boxing. I can remember bulling him into the ropes and throwing a lot of body punches, which is something I never did. I just saw where he was susceptible to it.” As against Robinson, Hernandez felt he clearly won, but again fell victim to scoring vagaries. “I don’t think it was close at all. Those yokels that judged the fight for Griffith were completely out of line.” What hurt most, he said, was the fact a victory might have set-up a title challenge. “I knew I was at my peak when I fought Griffith. If I had won that fight I probably could have fought for a world championship.” In the end, he said, “I guess I wasn’t impressive enough. There’s a lot of politics in boxing with the judging and the ratings and all that kind of crap.”

Hernandez had other chances to catapult himself into a title slot, but he always came up short, whether it was bad breaks or just plain bad habits. For example, a cut he suffered to his eye forced the stoppage of his first fight with world champ Nino Benvenuti in Rome and a leg injury he suffered in preparation for his second fight with Benvenuti in Toronto hampered his movement during the 10-round fight, which he lost by unanimous decision. The night before his match with former champ Denny Moyer in Oakland, Art reverted to his old ways by partying with Ferd. He paid for it in the ring the next night, losing a unanimous 12-round decision. He had more than his share of success, too, twice winning the North American Boxing Federation middleweight title and evening the score with Moyer in a 12-round decision in Des Moines. Ferd also faced the best, losing to Benvenuti and Luis Rodriguez, beating Robinson and boxing to a draw with Jose Gonzalez for the World Boxing Association American middleweight title in Puerto Rico in 1966.

Art’s toughest opponent? “That would have to be Jimmy Lester. He never stopped coming. I was in very good shape for that fight, but God, he would just pump and pump and pump. He was a tough guy. He beat me in a split decision.” Hernandez said while he never made much money fighting, and didn’t care much about the size of his purses anyway, boxing did let him see the world. His favorite stop? Marseilles, France. “The Mediterranean. Beautiful, man.” The worst stop? Vietnam, where he went as part of a USO tour during the war. “It was really disheartening to see all those kids in hospitals with their arms and legs shot off. It was terrible.”

While an injury forced Ferd to stop fighting, it took Art getting KO’d three consecutive fights to finally call it quits in 1973. “Bennie Brisco stopped me in three. Jean-Claude Bouttier stopped me in nine. And, in the last fight I had, Tony Licata stopped me in eight. After that, I thought, ‘Well, there’s no place else to go.’ So, I just gave it up.” He made an aborted comeback attempt when he started sparring with his up-and-coming brother Dale. “Once, he hit me somewhere on my head and I just tingled all over. I took the gloves off and said ‘That’s it. I’m done forever.’” He turned his attention to helping train Dale, the last great fighter in the Hernandez line. Where Ferd and Art were consummate boxers, Dale was a classic slugger. “He was a terrific puncher,” said Art, who often worked his corner. “Dale’s whole idea was he could knock anybody out and so he didn’t think he had to train too much. That was his problem.” The approach worked well enough for a time, with Dale securing a No. 9 world lightweight ranking, but the gambit caught up to him in a junior welterweight bout against Lennox Blackmoore. The sight of his brother beaten to a pulp at the hands of the counter punching Blackmoore was too much for Art to take. “I about had a heart attack in that corner because he got the shit beat out of him. I told Dale at the end of the fight, ‘I’m done working in your corner. I will not take it anymore.’ I never worked his corner again.”

After that thumping, Dale was never the same again, falling farther and farther off the training wagon. Away from boxing, Dale’s behavior spiraled violently out of control. He has done hard time for a series of aggravated assaults, the latest of which finds him serving a stretch in a Cheyenne, Wyo. jail. He is estranged from his once close-knit family. “I don’t know what his problem is. I have nothing to do with him anymore,” Art said. “I don’t even talk to him.” Just thinking of what his brother once was and could have been makes Art sick. “He could have been world champion. At 135 pounds he could whip anybody in the world. At 142 pounds he was too small. But he wouldn’t train to get down to 135. He wanted to play.”

With Dale out of the picture and Chuck living quietly in Des Moines, Art pined for the old days with Ferd, but they were separated by miles and lifestyles. Then, when Ferd became terminally ill in the mid-90s, Art and his wife Mary, a nurse, flew him out to Omaha. The change in the former world-class athlete was drastic. “I did not recognize him,” Art said. The couple cared for him the last three weeks of his life. He died in their home on July 17, 1996. Most of all, Art misses his brother’s “sense of humor. He was a funny guy.”

Two years later Art experienced the next biggest test of his life when, while clearing storm-strewn branches from the roof of his father-in-law’s house, he slipped and fell to the pavement below, his lower left leg shattering upon impact. He underwent eight surgeries to repair the damage. Then his recovery suffered a severe setback when infection set-in. Faced with months more of painful rehab and the possibility of infection redeveloping, he opted to have the leg amputated below the knee. “I knew that in order to get well, it had to be done,” he said, massaging the stub under the prosthetic he wears. He fought depression. “A lot of times I thought, ‘What am I doing here?’” He credits his wife for seeing him through it all. “If it weren’t for this woman, I’d be dead.” Friends helped, too. His old sparring chum, Ron Stander, hooked Hernandez up with another ex-athlete amputee — legendary pro wrestler “Mad Dog” Vachon, who lives in Omaha. “Ron called me and said, ‘I’m going to take you to Mad Dog’s because he’s got a leg like yours,’ and from there we become friends.” Hernandez made a quick recovery, resuming work four months later. He retired a couple years ago and, today, draws a county pension, enjoys watching televised fights and, like many old jocks, doubts this era’s competitors could have stacked-up with his generation of warriors.

In an era when boxing is largely dead in the state, Hernandez is the last link to one of Nebraska’s great sports dynasties. Leave it to Omaha boxing historian Tom Lovgren to put the family boxing legacy in perspective. About Art and Ferd, he said, “They could step up to fight anybody in the world. They showed no fear. They were animals.” About Dale, he reminds us, “At 135 pounds, he could beat anybody in the world.” Today, many pounds over his fighting trim, Art Hernandez battles diabetes and high blood pressure, but this still proud man is not one to wallow in Why me? pity. “Things happen,” he said, “and you just gotta go with the flow.”

Related Articles

- Golden Gloves…& golden heart (nydailynews.com)

- Gildardo Garcia finds redemption in ring and in life (denverpost.com)

- “The Latin Snake” Sergio Mora Could Bite Shane Mosley In Three Weeks (bleacherreport.com)

Wright On, Adam Wright Has it All Figured Out Both On and Off the Football Field

Though not a sports writer per se, I love writing about sports and I think I have a certain flair for it. So while I write about anything and everything in the course of a typical year, and certainly do not specialize in sportswriting, I like to keep my hand in it. The following article is an example from about nine or 10 years ago. The subject is an impressive young man named Adam Wright who made his mark on the football field at Omaha Nigh High and at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, my alma mater, as a running back. He wasn’t recruited by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln but the way he developed and dominated at the Division II level at UNO he certainly indicated he could have excelled in Division I and helped the Huskers. He even made it all the way to the National Football League as a free agent, but successive knee injuries stopped him in his tracks before he ever got to play a down. This story originally appeared in the Omaha Weekly, a paper that no longer exists.

|

Wright On, Adam Wright Has it All Figured Out Both On and Off the Football Field

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Omaha Weekly

Adam Wright has been so indestructible for the streaking UNO Maverick football team this year that no one foresaw this walking Adonis being sidelined by injury. After all, the senior has been the one constant and main workhorse for the often sputtering UNO offense in 2000, lugging the ball 30 times per contest the first seven outings. Time and again, the big bruising tailback with the ripped body crashed into a human wall at the line of scrimmage and came out the other side still intact, if not unscathed. He has taken many hard knocks, but delivered some too, usually leaving a litter of bodies in his wake. “I take pride in knowing I’m not going to be stopped by any one guy, no matter who he is, no matter how big he is,” Wright said. “I’m always looking to turn into somebody to dish out some punishment.”

But Wright, a bright and amiable student-athlete with a career in engineering (he is a civil engineering major) awaiting him if a hoped-for stint in pro football fizzles, was not always so assertive. The Omaha North High School graduate played quarterback as a prepster and arrived at UNO lacking the requisite toughness to be a hard-nosed tailback. As a freshman, he was even moved to wide receiver for a week. His passivity on the field was an off-shoot of his desire to blend in off it, where he grew up in an interracial home struck by tragedy. After losing his father at age 8, he watched his two older siblings make some bad life choices and set about being a model child for the sake of his mother.

He did anything to avoid being branded a troublemaker, even to the point of not using his God-given size to run over smaller players on the gridiron. Even after bulking up in college from 195 to his present 230 pounds, the 6’1 back steered clear of putting all of himself into runs. It took an attitude change, plus watching tapes of great backs, before he became the physical runner he is today. UNO Offensive Coordinator Lance Leipold recalls a heart-to-heart talk he had with his ballcarrier: “I said, ‘You’ve built yourself into this big back, now you’ve got to play like one.’” He said Wright, a devoted weightlifter, now not only “finishes off runs” but possesses a keen sense for the game: “He’s learned the blocking schemes better. He knows what’s really happening up front — where the hole is going to hit.”

His brute-force style, smarts and occasional breakaway speed (He cut his 40-yard dash time by two-tenths of a second over the summer — to a 4.7 electronic.), put Wright atop the NCAA Division II individual rushing chart for a time and allowed him to shatter UNO’s career rushing mark. He has 1,216 yards this season (just 100 yards short of the UNO single season record) and 3,761 overall. Earlier this year he recorded a stretch of three straight 200-yard-plus rushing performances. It’s been that kind of productivity that’s made him a regional finalist for the Harlon Hill Trophy (Division II’s Heisman).

By mid-season, he was a bruised but unbowed target for opposing defenses, absorbing hit upon hit but always picking himself up off the turf to get back into the fray. More often than not, tacklers were worn down by game’s end, not him.

Late, when defenses are tiring, he said, “you go for the kill. You put your head down a little lower, squeeze the ball tighter, fire out and go stronger.” Indeed, his late game heroics sealed wins against Northern Colorado and South Dakota. But with one twist of the knee early in the first quarter of UNO’s October 28 game versus South Dakota State, Wright went down in a heap, the medial collateral ligament in his left knee sprained. The injury happened on his first carry, a draw designed to go up the middle that he bounced wide. A defensive back came up on the play, making helmet contact just below Wright’s bent knee. As Wright tried to pull out of the tackle, his leg extended back and he felt his knee “wobble.” Playing in pain all season from tendinitis, he stayed in for a second carry, then with the knee only “getting worse,” he limped off, unable to return to a game UNO won 24-7 thanks in part to the steady play of his backup, redshirt freshman Justin Kammrad.

After week-long treatments, Wright was available for emergency duty last Saturday but with UNO dominating and Kammrad running wild (for a school record 239 yards) in a 45-7 win over Augustana. Wright did not see action. Instead, he nervously paced the sidelines — loudly encouraging his teammates. He should be close to full strength for this Saturday’s regular season finale at home against Top 20 foe and North Central Conference rival North Dakota (8-2). A healthy Wright will be a timely addition, as the 1 p.m. contest at Al Caniglia Field has major regional and national implications. Featuring a swarming defense that allows less than 10 points a game and a battering-ram offense that runs the ball down opponents’ throats, No. 5 UNO, now 9-1 and on a nine-game winning streak, is poised to capture just its second outright NCC title ever and to secure home field for the opening rounds of the NCAA playoffs. With their go-to guy back, look for the Mavs to feed the ball to No. 6 and, if his knee holds up, to ride his strong back as many times as needed.

Wright will gladly bear the load, too. “If it takes 40 carries for our offense to be successful, then give it to me 40 times,” he said. Following a 37-carry, 151-yard performance versus UNC on October 7, including gaining 38 yards on a crucial 4th quarter drive, Wright gouged South Dakota for 130 yards on 34 attempts the very next week. The more carries he gets, the more he starts “getting into a rhythm.” When he and his linemen get into that flow, running turns effortless. “It seems like once the ball is snapped, I’m beyond the hole. I’m in the secondary already. It’s kind of weird. It’s like, all of a sudden I’m there. I don’t even remember the run.”

The last few minutes of the SDU game offered another gut-check for UNO and Wright when, tied 7-7 in the 4th, the Mavs ground out two drives — with Wright the main weapon — to secure a 21-7 victory. With only minutes left, he was feeling the effects of all the pounding, but refused to sit out for even a play. “To tell you the truth, there was a point in time when I got up really slow and I was pretty sore. It was ridiculous. It was like being hit by a car — twice. My teammates were telling me in the huddle to get out of the game, but I knew J.J. (reserve tailback James Johnson) had sprained his knee and that Justin Kammrad was only a redshirt freshman. I felt I had to stay in. It was a close ballgame. And with only four minutes to go, I was like, ‘Ah, I’ve already been hit 30 times, what’s four more?’” Wright made his last four carries count, too, tearing through a tiring Coyotes defense on a short drive he capped with a nifty 23-yard touchdown run.

Doing whatever it takes has been ingrained in Wright since he lost his father, Jesse, to cancer in 1985. He has fond memories of the man, who was a packing house laborer. “The weird thing is, I can hardly remember his face, but I can remember a lot of lessons he taught me about life — about honesty, about integrity, about loyalty.” Prior to his father’s death, Wright’s mother, Liz, had been a stay-at-home mom. She returned to school (to study nursing) and entered the work force to provide for her three children. The demands took her away from her family more than she wanted. By the time her two oldest kids reached their teens, they were running wild. Adam, the youngest, sat back and saw how much grief his siblings’ behavior caused her and determined he would do nothing to add to her worries.

“My brother and sister pushed the limits to see how far they could go,” he said. “I saw how hard our mom was working just so we could have a chance for a better life and I didn’t want to disappoint her and make all the things she was doing be in vain. I tried not to disappoint anybody. Today, all of us are on the straight and narrow, but we each took different paths to get there.”

Liz Wright, an RN, recalls how as a child Adam displayed a maturity beyond his years. “Adam sort of comes from an underdog situation — being of mixed race, growing up in a poor area of the city and losing his father so young. I could have easily lost him to the crime environment in north Omaha.” She said his coming of age amid the near northside’s gang culture offered real temptations he resisted. “He didn’t take that path. A lot of his friends did. And what I admire most about him now is he doesn’t judge people who live that life. He’s a fair person. He’s kind of a keeper of justice.” Such congeniality, combined with male model good looks and a penchant for doing the right thing (he mentors disadvantaged youths), endear Wright to just about anyone he meets. For example, he was elected co-captain of the football squad and was recently voted vice president of the UNO student government.

His coaches — past and present — uniformly sing his praises. Herman Colvin, the head football coach at North High during Wright’s two years on the varsity there, became a father figure to the player. “He’s somebody I have a tremendous amount of respect and love for,” said Colvin, now assistant principal at Monroe Middle School in Omaha. “I really love the guy. He has made some good choices and I’m really happy with his choices. Has he done a lot to make me proud? He certainly has.” UNO Head Football Coach Pat Behrns said, “Adam’s a great guy. He does any type of public service work we ask him to. He’s great with young people. He’s a very classy young man. We’re going to hate to see him go.” Wright’s position coach, Lance Leipold, added, “He’s been a pleasure to work with because of his outstanding work ethic. He’s done a lot of little things to make himself a very quality back for us. But he’s not going to be one of those guys who’s going to be real frustrated if pro football doesn’t work out. Adam, from day one, has had such a plan in life. Someday, I might be working for him.”

The man instrumental in getting Wright to refuse Division I scholarship offers for UNO, Mid-American Energy CEO and fellow North High alum David Sokol, also commends Wright, whom he speaks of as a kind of protege (Wright has been an intern at Mid-American since 1996). “He has two characteristics I think are particularly important. One is, he has a very high character level. He is very cautious about keeping himself out of situations where, you know, bad things are liable to happen. The second thing is, he is extremely hard working and he has his priorities pretty well laid out. I think he can probably do anything he wants to, whether it’s the NFL or corporate America. We certainly would be more than happy to hire him after graduation.”

Clearly, the NFL is not an all-or-nothing proposition for Wright. It remains what his mom calls “a little boy’s dream.” As Wright himself said, “I’m a realist. I know it’s extremely hard to get there. If the opportunity presents itself, fine. But I’m going to leave my options open and do what’s in the best interests for my future.”

Carrying extra weight as “a cushion” against all the wear and tear he can expect to incur, Wright has his sights set on helping the Mavs make a run for the national title. “The way our defense is playing, if our offense can just control the clock, grind out the yards, get first downs and keep getting in the end zone, we have the potential to win every game.” Being on the sidelines has almost been more than he can take. “It’s killing me. I want to be on the field when we win.” he said. He will do whatever it takes to return. “I’ll argue, scratch and claw to get out there.”

Related Articles

- Georgia Tech 2010 Offensive Preview: Running Backs (bleacherreport.com)

- Arby’s Pick Five should be ready soon (chicagonow.com)

The Two Jacks of the College World Series

The College World Series underway in Omaha is a major NCAA athletic championship that attracts legions of fans from all over America and grabs gobs of national media attention. With this being the last series played at the event’s home these past 60 years, Rosenblatt Stadium, there’s been more fan and media interest than ever before, although a spate of rain storms actually hurt attendance at the start of this year’s series. Inclement weather or not, the series is a great big love-in with its own Fan Fest. But it didn’t used to be this way. Indeed, for the first three decades of the event, it was a rather small, obscure championship that garnered little notice outside the schools participating. Omaha cultivated the event when few others wanted or cared about it, and all that nurturing has resulted in practically a permanent hold on the event, which has strong support from the corporate community, from the City of Omaha, from service clubs, and from the local hospitality industry. Two key players in securing and growing the series have been a father and son, the late Jack Diesing Sr. and Jack Diesing Jr., and they are the focus of this short story that recently appeared in a special CWS edition of The Reader (www.thereader.com) called The Daily Dugout. I have another story on this site from the Dugout — it features Greg Pivovar, one of the colorful characters who can be found at the series.

The Two Jacks of the College World Series

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In 1967 the late Jack Diesing Sr. founded College World Series Inc. as the local nonprofit organizing committee for the NCAA Division I men’s national collegiate baseball championship. He led efforts that turned a small, struggling event into a major national brand for Omaha.

When son Jack Diesing Jr. succeeded him as president, the young namesake continued building the brand as Jack Sr. stayed on as chairman.

While the CSW is not a business, it’s a growing enterprise annually generating an estimated $40-plus million for the local economy. More than 300,000 fans attend and millions more watch courtesy ESPN.

Papa Diesing was around to see all that growth, only passing away this past March at age 92. Jack Jr. said his father, who saw the event’s potential when few others did, never ceased being amazed “by how it kept getting bigger and better. The phrase he always said is, ‘This just flabbergasts me.'”

His father inherited a dog back in 1963. Jack Sr. was a J. L. Brandeis & Sons Department Store executive. His boss, Ed Pettis, chaired the CWS. The event lost money nine of its first 14 years here. When Pettis died, Jack Sr. was asked to take over. He refused at first. No wonder. The CWS was rinky-dink. Nothing about it promised great things ahead. The crowds were miniscule. The interest weak. But under his aegis an economically sustainable framework was put in place.

What’s become a gold standard event had an unlikely person guiding it.

“When my father got involved with the College World Series he had never attended a baseball game in his life. He didn’t really want to do it but basically he agreed to do it because it was the right thing to do for the city of Omaha,” said Jack Jr. “Over a period of time he developed a love affair with not only what it meant for the fans but what it meant for the city and what it meant for the kids playing in it. He always was looking to do whatever we could do here to make the event better for the kids playing the games and the fans attending the games and for the community. And the rest is history.”

“I certainly grew up behind the scenes. I can’t say he was purposely grooming me into anything. It’s just that I was exposed to the College World Series ever since I moved back into town in 1975. I’d go to the games, I was involved in sports in school and still was an avid sports follower after I got back.”

Diesing said the same sense of civic duty and love of community that motivated his father motivates him.

He still marvels at his father’s foresight.

“One of the things people credited him for was having tremendous vision about how to set up the infrastructure and make sure we had an organization moving forward that would stand the test of time. And he thought it would make sense to carry on a tradition with his son following him, and that was another thing he was right about.”

His father not only stabilized the CWS but set the stage for its prominence by partnering with the city and the local business community to placate the NCAA by investing millions in Rosenblatt Stadium improvements to create a showcase event for TV.

College baseball coaching legend Bobo Brayton admired how Jack Sr. nurtured the CWS. “I think he was the single person that really kept the world series there in Omaha. I went to a lot of meetings with Jack, I know how he worked. First, he’d feed everybody good, give them a few belts, and then start working on ‘em. He was fantastic, just outstanding. It’s too bad we lost him…but, of course, Jack Jr. is doing a good job too.”

As intrinsic as Rosenbatt’s been to the CWS, Jack Jr. said his father knew it was time for a change: “He could see and did see the needs and the benefits to move into the future. Certainly, I’m the first person to understand the nostalgia, the history, the ambience surrounding Rosenblatt. It’s going to be different down at the new stadium, and it’s just a matter of everybody figuring out a way to embrace the different.”

Diesing has no doubt the public-private partnership his father fostered will continue over the next 25 years that Omaha’s secured the series for and well beyond. He’s glad to carry the legacy of a man, a city and an event made for each other.

Related Articles

- Rosenblatt Stadium memories will live on (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- College World Series: The 10 Greatest CWS Legends Omaha Has Ever Seen (bleacherreport.com)

- College World Series is Omaha’s party central (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- 1st game at new Omaha ballpark sells out in hours (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- The One That Got Away Is Still a Yankees Fan (nytimes.com)

The Little People’s Ambassador at the College World Series

UPDATE: Greg Pivovar’s Stadium View Sports Cards store was left high and dry when Rosenblatt Stadium was closed and the College World Series moved downtown to TD Ameritrade Park, but he does have a presence near the new site courtesy a tent set-up. My story below appeared on the eve of the 201o CWS, as Pivovar, whose shop stood directly across the street from Rosenblatt, prepped for his last dance with the old stadium.

As the College World Series enters the stretch run of the 2010 championship, I offer this story as a slice-of-life capsule of the local color that can be found in and around the event and its festival-like atmosphere. The subject is Greg Pivovar, who runs a sports memorabilia shop called Stadium View Sports Cards, across from Omaha‘s Rosenblatt Stadium, the venue where the CWS has been played for 60 years. This is the stadium’s last at-bat, so to speak, as it’s scheduled to be torn down next year, when the event moves to the new downtown TD Ameritrade Park. The ‘Blatt’s last hurrah is inspiring all manner of nostalgic farewells. Pivovar will be sad to see it go too, but he’s not the sentimental sort. In fact, he’s the cynical antidote to the otherwise perpetually cheery facade the city, the NCAA, and College World Series Inc. like to spin about the series, an event that Omaha has catered to to such an extent that there’s a fair amount of skepticism and animosity out there. Pivovar loves the series and the business it brings him, and he loves serving in the unofficial role of CWS ambassador for visitors from out of state, but he’s not Pollyannish about the event or the powers-that-be who run it. He just kind of says it like it is. His blog, stadiumview.wordpress.com, is a hoot for the way he skewers sacred cows.

I have posted another CWS story about a father and son legacy tied to the event.

Greg Pivovar, owner of the Stadium View shop, poses in his store in Omaha, Neb., Thursday, May 27, 2010. Pivovar is a one-man welcoming committee for College World Series fans. The Omaha attorney greets every (legal age) customer with a free can of beer and nudges them toward the barbecue, brats or, when LSU is in town, seafood jambalaya.(AP Photo/Nati Harnik) — AP

The Little People‘s Ambassador at the College World Series

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Stadium View Sports Cards proprietor Greg Pivovar makes a colorful ambassador for the College World Series with his Hawaiian shirt, khaki shorts and blue-streak S’oud Omaha patter. This bona fide character champions “the little people who built” the CWS.

Enter his sports memorabilia shop across from Rosenblatt and his coarse, cranky, world-weary sarcasm greets you, his barbs delivered with a stiff drink in one hand and a cell phone in the other. He talks like he writes on his stadiumview.wordpress.com blog.

“A lot of it is funny and cynical, but a lot of it is from my heart,” he said..

His shop’s a popular way stop for CWS fans craving authentic Omaha. He’s dispensed free beer since opening the joint 19 years ago. “It’s meant as a gesture of friendship and welcome, not as, Hey, you want to stand around and get drunk here? Part of the ritual,” he said. In 2006 he “took a cheap ass plea” on a ticket scalping charge he claims was bogus. He said the company he keeps is what got him in trouble.

“I have a bunch of scalpers who hang around here,” he said. “They’re friends of mine. I like them, they’re an interesting breed of human being.”

The arrest made headlines. A recent AP story that went viral called him a one-man CWS welcoming committee. Ryan McGee profiled him in the book The Road to Omaha.

“Famous…infamous, I’ve been both,” said Pivovar.

His uncensored ways hardly conform to the Norman Rockwell image the NCAA prefers.

Pivovar, who also serves homemade barbecue and enchiladas during the CWS, and cooks up a mean jambalaya whenever LSU makes it, feels he contributes to a “festival atmosphere.” Vendor and hospitality tents dot the blue collar neighborhood, where enterprising residents make a sweet profit charging for parking spots and refreshments.

The NCAA’s tried distancing the CWS from the commercial, party vibe. A clean zone will be easier to enforce with the move to TD Ameritrade Park next year.

“Piv” likes a good time but acknowledges all “the temporary bars” can be “a negative,” adding, “There’s a few too many people coming down here just to get drunk, and that’s not the idea. That sounds hypocritical coming from a guy who’s given 40,000 beers away, but it really isn’t. Most of my beers are given away one, maybe two at a time.”

The Creighton University Law School grad and former Sarpy County public defender has a private practice he puts on hold for the series. This being Rosenblatt’s last year, he’s stocked extra beer for the record hordes expected to say adieu to the stadium.

His own ties to Rosenblatt go back to childhood. His collecting began with baseball cards, sports magazines, game programs, signed balls. He got serious after college, traveling to buy and sell wares. Eventually, he said, “my collection was pretty much overrunning my home. I’m a hoarder. I needed a place to store my hobby.” Thus, the store was born, although he insists: “It’s not a business, it’s never been a business. I don’t make any money at this, I never have. It’s kind of like a museum.”

Most of his million or so cards, he said, “are just firewood.”

What business he does do largely happens during the CWS. Even then he said I “barely pay the bills.” He doesn’t know what he’ll do after the ‘Blatt’s gone and the series moves downtown. “I’d love to carry my hobby down there but…If somebody comes and shits a couple hundred thousand dollars on my face it might happen, but other than that…”

If he closes shop, he’s unsure what will become of his stuff.

“I don’t even want to think about it. I suppose I could throw it all on e-bay and get a mere pittance for it. That’s the way that works. So much of it has zero to such a narrow market, and I knew that going in. It’s not like I was having any allusions of getting rich from this.”