Archive

Brent Spencer’s fine review of my Alexander Payne book nets nice feedback

Brent Spencer’s fine review of my Alexander Payne book nets nice feedback

I only just now became aware of this fine review of my Alexander Payne book that appeared in a 2014 issue of the Great Plains Quarterly journal. The review is by the noted novelist and short story writer Brent Spencer, who teaches at Creighton University. Thanks, Brent, for your attentive and articulate consideration of my work. Read the review below and some nice responses I got to this news.

NOTE: I am still hopeful a new edition of my Payne book will come out in the next year or two. it would feature the additon of my extensive writing about Payne’s Nebraska. I have a major university press mulling it over now.

Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film—A Reporter’s Perspective, 1998–2012 by Leo Adam Biga

Review by Brent Spencer

From: Great Plains Quarterly

Volume 34, Number 2, Spring 2014

In Alexander Payne: His Journey In Film, A Reporter’s Perspective 1998-2012 Leo Adam Biga writes about the major American filmmaker Alexander Payne from the perspective of a fellow townsman. The local reporter began writing about Payne from the start of the filmmaker’s career. In fact, even earlier than that. Long before Citizen Ruth, Election, About Schmidt, Sideways, The Descendants, and Cannes award-winner Nebraska. Biga was instrumental in arranging a local showing of an early student film of Payne’s, The Passion of Martin. From that moment on, Payne’s filmmaking career took off, with the reporter in hot pursuit.

The resulting book collects the pieces Biga has written about Payne over the years. The approach, which might have proven to be patchwork, instead allows the reader to follow the growth of the artist over time. Young filmmakers often ask how successful filmmakers got there. Biga’s book may be the best answer to this question, at least as far as Payne is concerned. He’s presented from his earliest days as a hometown boy to his first days in Hollywood as a scuffling outsider to his heyday as an insider working with Hollywood’s brightest stars.

If there is a problem with Biga’s approach, it’s that it can, at times, lead to redundancy. The pieces were originally written separately, for different publications, and are presented as such. This means a piece will sometimes cover the same background we’ve read in a previous piece. And some pieces were clearly written as announcements of special showings of films. But the occasional drawback of this approach is counter-balanced by the feeling you get of seeing the growth of the artist take shape right before your eyes, from the showing of a student film in an Omaha storefront theater to a Hollywood premiere.

But perhaps the most intriguing feature of the book is Biga’s success at getting the filmmaker to speak candidly about every step in the filmmaking process. He talks about the challenges of developing material from conception to script, finding financing, moderating the mayhem of shooting a movie, undertaking the slow, and of the monk-like work of editing. Biga is clearly a fan (the book comes with an endorsement from Payne himself), but he’s a fan with his eyes wide open. Alexander Payne: His Journey In Film, A Reporter’s Perspective 1998-2012 provides a unique portrait of the artist and detailed insights into the filmmaking process.

Brent Spencer, Department of English, Creighton University, Omaha, NE.

HERE IS SOME LOVELY FACEBOOK CORRESPONDENCE THAT NEWS OF THE REVIEW PROMPTED:

-

-

Brigitte Timmerman One of my film friends from Chicago gave this to me a while ago knowing we both are from Omaha. I have to commit to read it.

-

Leo Adam Biga Tnank you so much Jayne Putjenter Meehan and I hope the book lives up to the notices Brigitte Timmerman.

-

Jayne Putjenter Meehan Yes. Brigitte, it’s a must-read.

Leo Adam, your writing is so brilliant and smooth.

-

Melanie Advancement Brent Spencer is a great guy-who knows his stuff! One great writer reviewing another!

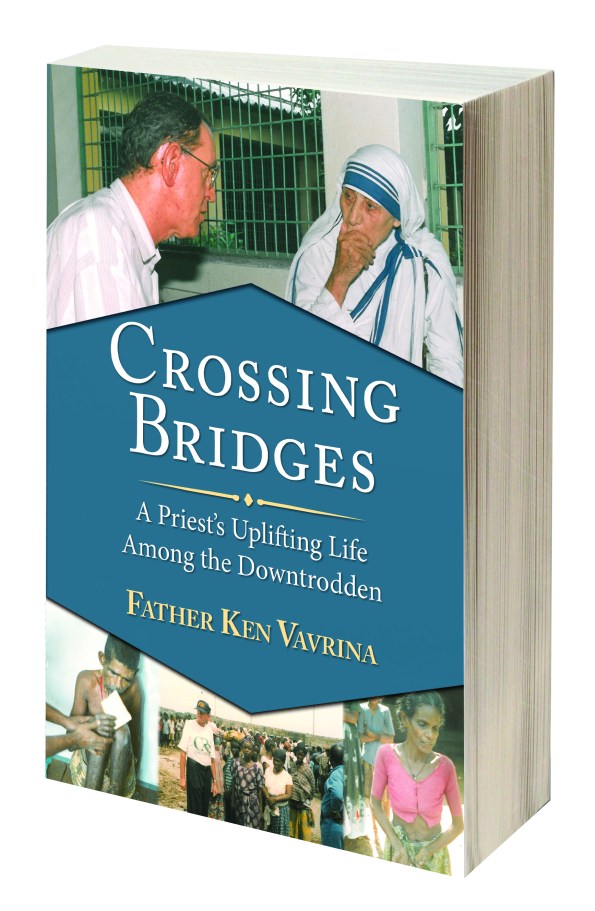

Coming Soon: A new book I wrote with Father Ken Vavrina, “Crossing Bridges,” the story of this beloved Omaha priest’s uplifitng life among the downtrodden

COMING SOON A new book I wrote with Father Ken Vavrina-

“Crossing Bridges”

The story of this beloved Omaha priest’s uplifitng life among the downtrodden.

Look for future posts about where you can get your copies. All proceeds will be donated to Catholic organizations.

-

-

Ledia Bedia Can not wait!

-

George M. Herriott Great subject. Looking forward to a great read.

-

SK Williams Author Will watch for it!! smile emoticon

-

Monica Cooper-Hubbert Oh My Goodness! He is one of my favorites! Love him to pieces. Renewed my parents 50th anniversary wedding vows. smile emoticon♡♡♡

-

Melanie Advancement He has had quite the life. That should be an awesome story!

Brent Spencer’s fine review of my Alexander Payne book in the Great Plains Quarterly

Brent Spencer’s fine review of my Alexander Payne book in the Great Plains Quarterly

I only just now became aware of this fine review of my Alexander Payne book that appeared in a 2014 issue of the Great Plains Quarterly journal. The review is by the noted novelist and short story writer Brent Spencer, who teaches at Creighton University. Thanks, Brent, for your attentive and articulate consideration of my work. Read the review below.

NOTE: I am still hopeful a new edition of my Payne book will come out in the next year or two. it would feature the additon of my extensive writing about Payne’s Nebraska. I have a major university press mulling it over now.

Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film—A Reporter’s Perspective, 1998–2012 by Leo Adam Biga

Review by Brent Spencer

From: Great Plains Quarterly

Volume 34, Number 2, Spring 2014

In Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film—A Reporter’s Perspective 1998–2012, Leo Adam Biga writes about the major American filmmaker Alexander Payne from the perspective of a fellow townsman. The Omaha reporter began covering Payne from the start of the filmmaker’s career, and in fact, even earlier than that. Long before Citizen Ruth, Election, About Schmidt, Sideways, The Descendants, and Cannes award-winner Nebraska, Biga was instrumental in arranging a local showing of an early (student) film of Payne’s The Passion of Martin. From that moment on, Payne’s filmmaking career took off, with the reporter in hot pursuit.

Biga’s book contains a collection of the journalist’s writings. The approach, which might have proven to be patchwork, instead allows the reader to follow the growth of the artist over time. Young filmmakers often ask how successful filmmakers made it to that point. Biga’s book may be the best answer to this question, at least as far as Payne is concerned. Biga presents the artist from his earliest days as a hometown boy to his first days in Tinseltown as a scuffling outsider to his heyday as an insider working with Hollywood’s brightest stars.

If there is a problem with Biga’s approach, it is that it occasionally leads to redundancy. The pieces were originally written separately, for different publications, and are presented as such. This means that an essay will sometimes cover the same material as a previous one. Some selections were clearly written as announcements of special showings of films. But the occasional drawback of this approach is counterbalanced by the feeling you get that the artist’s career is taking shape right before your eyes, from the showing of a student film in an Omaha storefront theater to a Hollywood premiere.

Perhaps the most intriguing feature of the book is Biga’s success at getting Payne to speak candidly about every step in the filmmaking process. These detailed insights include the challenges of developing material from conception to script, finding financing, moderating the mayhem of shooting a movie, and undertaking the slow, monk-like work of editing. Biga is clearly a fan (the book comes with an endorsement from Payne himself), but he’s a fan with his eyes wide open.

Attention must be paid: In the spirit of Everyone Has A Story To Tell…

Attention must be paid

In the spirit of Everyone Has A Story To Tell…

Many of us are familiar with the phrase, “Everyone has a story to tell.” Few of us, however, behave as if we believe that sentiment to be true. Most of us ignore, if not dismiss the experiences of others unless those experiences happen to belong to a close friend or family member or unless the experiences are attractively, compellingly packaged in some commercial media product. It’s hard to deny we tend to tune out stories that do not immediately appeal to our sense of curiosity and thirst for drama, tragedy, inspiration, entertainment, titillation or pure distraction. We are increasingly reliant on media channels to tell us what is worthy of our attention. More than ever before we are programmed to overlook all but the most trending or iconic or marketable stories amid the glut of data – videos, sound bytes, headlines, texts, tweets – coming at us from a multiplicity of communication-information platforms. This tendency to abdicate our personal investment of time and energy and inquisitiveness to get to know someone in our immediate reality, such as a neighbor, a coworker or the mailman, to an impersonal web search engine’s recommended list of newsmakers and celebrities we will likely never meet, makes it harder for every day people to authentically know one another. In this supposed golden age of interconnectedness the irony is that we can find ourselves increasingly disconnected from each other’s true lives and intimate stories as we more and more settle for “knowing” people by their usernames, tag lines, logos and avatars and “following” their lives virtually via social media.

I believe this phenomenon accounts for the basic lack of respect that permeates too many interactions and transactions between people these days. If you’re too busy or stressed or self-involved or condescending to get to know someone, you’re more likely to be rude or indifferent to them.

It doesn’t have to be this way, of course. How we attend to people and to their personal stories and spaces is still a matter of choice, a matter of intention.

For all this talk about the distancing, distorting effect of media, good journalists continue playing a vital role as storytellers who focus past the noise of all that clutter to flesh out the narratives of individuals from every walk of life. Human interest stories they’re called. Far more than filler or fodder, they are portraits and snapshots of a society and a period. They are windows into the human soul. They remind us of our shared traits and of our boundless differences. They are markers for the human condition. I’m proud to say I make my living doing this. I’ve even branded myself – God knows we all need to be able to reduce the sum of our parts to a brand in order to be relevant in today’s hash-tag environment – with the tagline: “I write stories about people, their passions and their magnificent obsessions.” Which is to say, as the cliche goes, I write about what makes people tick. I prefer to think of it as giving voice to the things that drive people to create, to endeavor, to aspire, to grow, to build, to sacrifice, to carry on. The reason I devote myself to this discipline and calling is that I truly do embrace the notion that we all have a story to tell. For that matter, we all have many stories to tell. In one way or another, we’re all subjects and characters worthy of being interviewed, profiled, remembered because we all have things to teach others and to move others.

It would be a shame, wouldn’t it, if someone, and it just happened to be me, didn’t tell the story of an Old Market eccentric named Lucile who dressed all in orange and decorated her home with decades worth of architectural remnants she’d collected? Or what about the classical violinist who plays in major symphony orchestras and rigorously practices Buddhism and incongruously lives in a trailer and works a warehouse day job. I wouldn’t have missed his story for the world but the world almost missed out on it if not for him telling me the story of his life and me writing it up and getting it published. Then there’s the master of Spanish classical guitar who once shared the stage at Carnegie Hall with his legendary mentor and yet who continued to compete in professional rodeos, Why put his fingers and hands at great risk? Because Hadley loved his art and his cowboy roots equally. Both were necessary expressions of his unquenchable lust for life.

I loved the story of the little old man from the Pennsylvania German anthracite coal mines. In his youth he broke horses along the Colorado River and during World War II he helped the U.S. military learn the secrets of advanced German jet fighter technology. Then as a venerable scholar he translated the massive diaries of a 19th century German prince whose expedition of the vanishing Western America frontier provided an invaluable glimpse of life in that period.

I’ll never forget a woman and her remarkable transformation, which is happening as we speak and continues to bloom. In relatively short order she’s gone from life as a substance abuser, stripper and prostitute to surviving a failed marriage to raising three children on her own to finding her and her family homeless at times as she tried getting things together. While still homeless off and on she launched a business making skin lotions, cleaners and scents using shea butter. Her business has attracted major backers and her products are now sold in stores across America. The topper to all this is that she wants most of the proceeds to support an African mission she’s established to help villagers who harvest the shea butter she uses in her products.

Memorable too is the music lover from Omaha who was part of an all-black WWII quartermaster battalion. He and 15 others from Omaha – they called themselves The Sweet 16 – served together all the way from induction to basic training to North Africa to Italy. After the war Billy earned money as taxi driver, railroad baggage handle and gambling house proprietor. He also quietly amassed a staggeringly large music collection and made sure he and his war buddies stayed in touch via reunions.

I could go on and on. The point is, remarkable, compelling stories are all around us. Until you ask, until you show some interest, you just won’t know that Brenda, the spirited old woman singing karaoke at the local bar, performed with Johnny Cash and toured Vietnam during the war with an all-girl band. You’d never guess that Helen, the elderly school para, was the lead trombonist in a multi-racial all-girl band that played the Apollo Theatre and all the top clubs and concert halls from the start of the Great Depression through the war. You’d never learn that Marion, the double amputee confined to a wheelchair in a nursing home, was arguably the best all-around athlete to ever come out of Neb, and that he integrated Dana College, where some of his athletic marks still stand 60 years later.

More recently, there’s the story of the priest who shook off his small town Neb. roots in one sense but never lost his homespun quality in another sense while ministering to diverse peoples in underserved communities and developing nations. Father Ken worked for Mother Teresa serving lepers in Yemen. He ran Catholic Relief Services humaniatian aid programs in India and Liberia. He learned many lessons in crossing all those cultural bridges and borders and he shares those lessons in a new book I collaborated with him on that comes out this fall. Then there’s Bud, a young man who has risen out of harsh conditions in northeast Omaha to become a world boxing champion. I recently traveled with him to Uganda and Rwanda, Africa, a pair of countries he’s visited twice in the last year. I went to chronicle his ever expanding exploration of the world and how the self-sufficiency and empowerment programs he witnessed in those East African nations relate to what he’s trying to do at his B & B Boxing Academy in North Omaha.

It is my privilege to tell these stories. Because I am a storyteller by trade, I also see it as my duty. With all the ready means for communication available today, I think it’s incumbent on us all to tell our stories and to tell the stories of those around us. That means talking to people and capturing their stories in words and images and putting those stories out there. It doesn’t matter if you’re a professional or an amateur, a staff reporter or a stringer or a freelancer or a citizen journalist or a blogger. It doesn’t have to be journalism either. It can be stories told through still or moving images, through music, through poetry, through fiction, you name it. Off-line, on-line, hard cover, soft cover, CD, DVD, slide show, stage show, it doesn’t matter. It’s all good. It’s all about getting it down and putting it our there. It’s all raw material that can be the basis for dialogue, discussion, or study. Take my word, once you tell a story that distills the essence of someone, it will leave an impact on that person and their family. It will captivate an audience and it will start a conversation. And more stories will follow and reveal themselves as a result. It’s all about acknowledging lives and experiences. Preserving legacies and memories. To be passed on. To be discovered and rediscovered. Lest we forget, lest we never know, attention must be paid.

It’s why I’m a big proponent of oral history projects that collect the stories of rank and file citizens right alongside those of community, business, and elected leaders, celebrities and social mavens. I’m trying to put together one of these projects right now in North Omaha. We can never really know or appreciate each other until we tell our stories and share them.

Now that’s what I call connecting.

NOTE: You can sample the stories I tell about people, their passions and their magnificent obsessions on this blog-

leoadambiga.wordpress.com

Or on my Facebook timeline or FB page, My Inside Stories.

A Journey in Freelance Writing

For Omaha metro residents, the promotion below is a heads-up regarding a presentation I am making about freelance writing. It’s free and hopefully not boring. The presentation is open to anyone. It’s part of the ongoing North Omaha Summer Arts Festival. The fest’s website address is at the bottom of this post. Check it out.

North Omaha Summer Arts 2011 presents:

A Journey in Freelance Writing

Veteran journalist and author Leo Adam Biga uses his own 27-year career to talk about what life as a freelance writer can look like.

Wednesday, August 10, 6-8pm

Call 402.455.7015 Mon thru Fri, 9am – 4pm for registration

This class is free of charge

Topics to be covered include:

•real life experience

•learning your craft

•on the job education/training

•finding a niche

•writing about your interests

•just doing it

•daring to risk different fields & styles of writing

•building a client base

•managing multiple projects

•is there any money in this?

As a contributing writer to newspapers and magazines, he’s had thousands of articles published on a vast array of subjects, many of them arts, culture, sports, and history related. Other clients include for-profit corporations, nonprofit institutions, individuals, and families.

At Church Of the Resurrection

3004 Belvedere Boulevard

Omaha, Neb.

Lit Fest brings author Carleen Brice back home flush with success of first novel, “Orange Mint and Honey”

Another Omaha native writer enjoying breakout success is Carleen Brice, whose first two novels have done very well. This is the first of a few articles I’ve written about Carleen and her work. My story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) appeared shortly after her first novel, Orange Mint and Honey, announced her as a major new voice to be reckoned with, and she soon proved that debut novel was no fluke with Children of the Waters. More recently, the superb Lifetime Movies adaptation of Orange Mint, which goes under the title Sins of the Mother, won NAACP Image Awards for Outstanding TV Movie and for Jill Scott in the lead role of Nona. Now. Brice’s sequel to Orange Mint, which she calls It Might As Well Be Spring, is due out this summer, and she’s at work on yet another novel, Calling Every Good Wish Home. I feel a personal investment in Carleen because her late grandfather, Billy Melton, was a vital source and good friend. He always spoke with great pride about her accomplishments. Go to my Billy Melton category to check out some of the stories I wrote about him and his various passions and adventures.

You can find my other Carleen Brice articles, including one about that Lifetime adaptation, by clicking on her name in the category roll to the right. I expect I’ll be adding more pieces about her as her career continues going gangbusters. Billy’s smiling somewhere.

Lit Fest brings author Carleen Brice back home slush with success of first novel, “Orange Mint and Honey”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Denver author Carleen Brice, an Omaha native who left here after graduating Central High School in the 1980s, is getting raves for her first novel, Orange Mint and Honey (One World Ballantine Books, 2008). It follows three nonfiction books and numerous newspaper-magazine essays-articles that earlier established her as a wry observer of the African American experience and the larger human condition.

Now Brice is returning as an invited author at this weekend’s (downtown) Omaha Lit Fest. That makes it sound like she hasn’t been back in awhile, which isn’t so, but now she’s riding the momentum of her novel being an Essence Magazine Recommended Read and a Target Bookmarked Breakout pick.

She’ll appear on a Saturday noon panel at the Bemis about music as an influence on writing. That’s apt as music’s a family legacy Brice inherited “by osmosis” from her beloved late grandfather, Billy Melton, or “Papa,” whose best friend was the late jazz musician and her surrogate uncle, Preston Love Sr. Her jazz-blues bassist husband, Dirk, jammed with Preston at Papa and grandmama Martha’s 50th wedding anniversary. Papa’s vast music collection led Brice to jazz singer Nina Simone. In Orange Mint Simone’s presence appears to the embittered, traumatized daughter, Shay, as a guide to find healing with her recovering alcoholic mother, Nona.

Shay, portrayed as a fan of classic jazz-blues, gets involved with a younger man she works with at a Denver music store. He schools her on contemporary artists.

Then consider Brice often uses music when writing to evoke moods she wants to convey. There’s plenty of mood swings in Orange Mint. The strained mother-daughter story is infused with pain and humor. Forgiveness walks a rocky road. The messy reconciliation between two strong wills rings true. The relationship is fiction but draws on the dynamic Brice had with her own mom. Just as Nona bore Shay as a teen, Brice’s late mother bore her at 15. Like Nona, her mom was a pistol. Unlike Nona, she was no alcoholic. Brice’s folks divorced when she was young.

“We had kind of the typical mother-daughter, love-hate so-close-that-we-drove-each-other-insane kind of relationship,” Brice said by phone. “We were more like sisters. What it’s like to have a young mom that you sort of sometimes feel like you’re raising her instead of she’s raising you comes out in the book.”

Brice’s novel never devolves into melodrama or soap opera. It satisfies and surprises in ways only a gifted writer and old soul can deliver. The book’s being adapted by a producer for a Lifetime Television movie and one hopes it’s treated with the care and sophistication it deserves. On her blog, The Pajama Gardener, a compendium of Brice’s musings about working in the earth and writing, activities she sees parallels in, the author votes for Angela Bassett to play Nona.

Nona’s passion for gardening reflects the kinds of creative, expressive outlet many black women have sought in lieu of limited opportunities for careers in the arts.

Orange Mint confirms the promise Brice has long exhibited as a storyteller.

Her first book dealt with African Americans and the grieving process and her next offered affirmations for people of color. More recently, she edited Age Ain’t Nothing But a Number (Souvenir Press, 2003), a collection of writings by black female authors, including icons Alice Walker, Terry McMillan, Niki Givoanni and Maya Angelau, that Brice put together on the subject of black women navigating mid-life. Brice contributed two pieces of her own to that well-reviewed compilation. One comments on the unrealistic expectations black women like herself face when young and how, in middle age, she’s attempted to free herself and her expressive soul from the bondage of myth.

Just don’t mistake those projects for advice column fodder. They’re much more than that. Brice writes with an eloquence and depth that put her on the same plane as the literary lionesses she shares the pages with in Age Ain’t Nothing. It’s only fitting that Brice, who grew up reading many of the very authors she’s now immortalized with, should be recognized as a serious new African American voice.

Early on she evidenced a love for the written word. “My mom liked to read,” she said, “so when I was really little I learned the joy of reading and storytelling, and I think that’s what led me to want to be a writer. I used to tell stories to other kids. I’d just make things up. I wrote my grandmother Martha stories. When I was in high school I studied creative writing. In college I studied journalism. Most of my job jobs involved writing. So it’s something I’ve always enjoyed.”

Brice no longer works a day job. She writes every day, a discipline she credits Dirk with inspiring in her. “Kind of like building my chops as a writer,” she said. “When not laying down “the bones” or “the heart” of her stories, she interacts with a literary community via book clubs, readers’ circles, writers’ groups.

She’s in-progress on a new novel, Children of the Waters, due out next July. It explores issues of race, identity and what really makes a family, she said. The story explores what happens when a pair of biracial sisters raised in separate families — one white, the other black — find each other as adults.

The author is musing with the idea of continuing Nona’s story in a future project.

Brice is among that vast exodus of blacks who’ve left this place over the years to realize their dreams elsewhere. But like many of these expatriates she’s never really left. She has lots of family and friends here. A contingent even came to Orange Mint’s release party in Denver. They’re a tight bunch and they’ll be representing at Lit Fest. They’ll have a good time, too, she said, as her “larger-than-life” family knows how to party — another legacy of sweet, ebullient Papa.

His music, she said, speaks through her.

The Sept. 19-20 (downtown) Omaha Lit Fest is its usual eclectic self, with a mish-mash of events that address diverse literary themes, some with more than a wink of the eye. The BIG theme this year is Plagiarism, Fraud & Other Literary Inspiration. Fest events take place at some of Omaha’s coolest venues, including the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, the RNG Gallery, Slowdown, Aromas Coffee House and the Omaha Public Library’s W. Dale Clark branch.

Some of Omaha’s and America’s hottest writers converge for readings, panel discussions and other litnik activities. Brice fits the bill to a tee. Think of the fest as a progressive mixer for readers, authors and artists engaging in a literary salon experience — Omaha-style. A scene where laidback meets high brow. For a complete schedule visitwww.omahalitfest.com.

Related articles

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

The Worth of Things Explored by Sean Doolittle in his New Crime Novel “The Cleanup”

Omaha is home to many fine novelists and I have the opportunity to sit down and talk writing with some of them from time and time. One of these is Sean Doolittle, a crime novelist of the first rank and a man who leaves all pretensions at the door. The following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) is the first piece I did on Sean and his work, and the second will soon be posted on this site as well. If you’re looking for a good summer read that engages your mind and your adrenalin then I highly recommend his intelligent page-turners.

Sean Doolittle

The Worth of Things Explored by Sean Doolittle in his New Crime Novel “The Cleanup“

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Sean Doolittle has you join him in the very booth at the very Omaha watering hole, the Homy Inn, where the violent denouement of his new novel The Cleanup (Dell) unfolds. Just as you slide in, he mentions you’re about to sit where Gwen, the wan victim in his tale of ever escalating misdeeds, nearly loses her life. The fact he looks a bit like the towering Red Dragon character in the film Manhunter gives you pause. Within minutes he reveals the same disarming tone of his classic crime fiction, which sardonically, not gravely, lets characters stew in their own juices.

In The Cleanup the Omaha-based author has his cop protagonist Matthew Worth discover a murder and rather than call it in, clean it up, which throws into motion, ala Scott Smith’s A Simple Plan, a cascade of unforeseen results that keep forcing Worth’s hand, raising the stakes each time. Things get complicated when it turns out the corpse was a mule in an illicit racket short a quarter million bucks. The question becomes how far will Worth go to cover his and the murderer’s tracks and how far will those after Worth’s neck or the loot, or both, go to get answers?

“I really like stories where the plot is dictated by the choices the characters make. It’s a continual reaction against cause and effect. That feels to me the way life is,” said Doolittle, whose previous novels Dirt, Burn, both set in L.A., and Rain Dogs elicited warm words from some of crime fiction’s top names. The Cleanup, due out October 31, is getting similar raves. His agent is in negotiations over a potential feature film deal. Unlike many crime authors, Doolittle’s “been lucky” to avoid pressure by editors/publishers to do a series or sequel. His are stand-alone books.

The new novel grew out of a short story, Worth, Doolittle wrote years ago that ended where The Cleanup begins. The character of Worth, a burned out cop reduced to supermarket patrol seeks to redeem himself, gnawed at him.

“I like the idea of this character really trying to do maybe the wrong thing for the right reasons,” he said. “He’s driven to do it. In a dream sort of state, he keeps going. There’s definitely a point of no return in a situation like that where once you step far enough over the line, you have to keep going and keep going. The impulsive action quickly becomes unreturnable. No matter how much he tries to dig himself out he just keeps digging himself in deeper and deeper and deeper. To me, it’s more intriguing than a mystery per se, where you’ve got some clues and you’re trying to piece together a puzzle of who-did-what.

“I’m much more interested in the way people respond to circumstances, what that leads them to do and how those actions compound on each other…There’s really not any sort of mystery in The Cleanup, except wondering how it’s all going to play out for the characters. There are little surprises along the way.”

As a nod to classic noir, Doolittle has Worth cross the line for the sake of a woman (Gwen) who, while not quite a femme fatale, draws the cop into a dark place where his one rash act has dangerous consequences in a kind of domino effect.

“In a way, we’re looking at this character of Worth on the day he did something he might not have done on any other day. It ends up changing his life,” Doolittle said of his disaffected hero, who in the course of the story moves from apathy to conviction. “He comes from a long line of police officers and so he goes into that profession as sort of a family trade. But he doesn’t have the temperament for it. He’s not cut out for it. He’s a laughing stock in the department.

“Here’s this guy who became a police officer for this sort of civic minded idea of being useful to the world and found much more self worth in the simple act of bagging people’s groceries than he ever had in the frustrating job of being a cop. In wanting to save her (Gwen) she represents what he wanted to do in becoming a police officer in the first place. This temporary savior complex that overcomes him has lots of levels in it that he puts all together in Gwen.”

What Worth doesn’t know is that his quest to find self-worth in helping Gwen out of a jam is really about saving himself. But, as Doolittle said, his redemption comes “at a fairly high cost by the time it’s all over.”

Although long “drawn to kind of darker stuff,” Doolittle’s not sure why and feels the reasons for it may be best left unexamined.

“It’s the sort of thing where you don’t really want to solve that mystery because it is your fuel and once you learn the secret maybe you lose the fuel,” he said. “The old chestnut is good drama is based on conflict and I think crime novels provide a very visceral, bottom line conflict you can start with and work from. I like what you can do within the general framework of a crime novel or a noir novel in terms of exploring human behavior. I think the way people respond to extreme pressure or in extraordinary circumstances is an interesting dramatic place to play around.”

He recalls the first story he wrote, for a school class exercise, was in the hard-boiled, first-person vein of a P.I. narrator. A kind of, “I was sitting in my office when…” tease. Strangely, he’d not yet read any crime fiction, “but I must have osmosed that sort of iconic story through my skin or something,” he said. “I don’t know if I caught pastiches on television…You just pick that stuff up everywhere.”

Among his earliest influences was Stephen King. That led him to Robert Bloch (Psycho). Then about the same time he was exposed to the neo-noir of Quentin Tarantino’s films and the breezy mayhem of Elmore Leonard’s novels, which led to old masters like Jim Thompson, Dashiell Hammett, Philip Chandler and James M. Cain. “I kind of started like a lot of people do,” he said, “by finding somebody in the mainstream and then reading my way back into the margins from there.”

Born and raised just outside Lincoln, Neb., Doolittle began as a journalism major at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln but switched to English under the tutelage of Gerald Shapiro and Judith Slater. As an undergrad his first “pro fiction,” a short story, sold and paid “real money.” He intended on an academic career teaching college English and writing, but after getting his master’s, he said, “I decided what I really wanted to do was write fiction. I got a regular job and just kept on writing.”

Married now with two young children, he still holds down a regular office gig, writing technical manuals for First Data Resources, but he hopes his books will catch on enough to “relieve the need for that day job.”

He credits his wife Jessica for cutting him slack over the odd writer’s life he leads. “When I’m in the middle of a book it’s not just that I’m physically away at the computer typing, when I’m walking around the house my head is somewhere else,” he said. “It’s very difficult to explain, even to a very supportive spouse…that sitting in a chair staring into space is working. You know, there are tough weeks when everybody’s had long days and any human being would lose their patience. With The Cleanup I was very much behind deadline and the end of that book got very tense. I was really having to lock myself away…to try to finish the book. Jessica was very understanding but by the end it was clear that something had to give.”

In his acknowledgements he thanks his mother for coming to the rescue in “the perfect storm” of deadlines, travel commitments and family illnesses that hit all at once. “Everything just fell apart,” he said. “Without my mother I don’t know how we would have gotten through that.”

Where Rain Dogs was set in Valentine, Neb. and The Cleanup in Omaha, the book he’s working on now is set in a fictional Iowa college town. For this as yet untitled “suburban thriller” he doesn’t want the distraction of adhering to a specific place but instead an Anytown USA readers can project their own experiences onto.

Just as he doesn’t like showing his work until he has a finished piece in hand, he dislikes talking about a book still in embryo. “The idea is kind of fragile for a period of time,” he said, “and you can really crush an idea by talking about it too much.” It’s why he’s reluctant to say much about a big screen adaptation of The Cleanup other than there’s “pretty strong interest” from “a fairly well known writer-director. It’s the first book that’s drawn interest prepublication. Things look fairly promising for a deal, but everything in Hollywood is talk until something happens.”

Doolittle may have left Omaha and environs for his new work but he plans to revisit Nebraska again in his fiction. “I’ve really enjoyed writing the last couple of books closer to home and I want to continue to work around this area.” Besides, it’s so much fun to track blood lettings in the very places one haunts.

Related articles

- Author Nesbø: I am attracted to dark side (cnn.com)

- Writers Tip #61: Advice From Elmore Leonard (worddreams.wordpress.com)

- A Killer Vision of a Corrupt Society (online.wsj.com)

- With His New Novel, ‘The Coffins of Little Hope,’ Timothy Schaffert’s Back Delighting in the Curiosities of American Gothic (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Crime fiction for summer (salon.com)

- Lit Fest Brings Author Carleen Brice Back Home Flush with the Success of Her First Novel, ‘Orange Mint and Honey’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

The Many Worlds of Science Fiction Author Robert Reed

I am consistently amazed at the talent surrounding me. Until I saw an item about Robert Reed in the local daily I had no idea that one of the preeminent science fiction authors of his time was from Omaha and still lived in the area – 50 miles away in Lincoln, Neb. I promptly sought out his work and was blown away by his gift, and soon thereafter arranged an interview with him. The resulting story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) appeared in the wake of Reed having won the Holy Grail of his profession, the Hugo Award, for his novella A Billion Eves. My very short piece hardly does the prolific justice to Reed, whose work is included in countless Best Of collections and anthologies, which is why I pine to do another story about him, hopefully one of some length. He is up for another major prize by the way, as a finalist for the Theodore Sturgeon Award for his novella, Dead Man‘s Run.

The Many Worlds of Science Fiction Author Robert Reed

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Omaha native Robert Reed’s 2007 Hugo Award-winning novella A Billion Eves imagines devices called “rippers” that punch holes in the fabric of the space-time continuum. People and places get propelled from one world to some infinity of alternate worlds. The prospect of man playing God in new edens plentiful with women proves a Pandora’s Box of male fantasy run amok. The Fathers of these frontiers may be false prophets.

Eves is a cautionary tale about staking claims in facsimile worlds that may have short life spans and be susceptible to human contamination. Better to begin with a clean slate, suggests Reed, a prolific science fiction author. Speculative musings about the fallout of using quantum mechanics as an instrument of Manifest Destiny consume Reed. He has great fun, too, with the divergent creation stories bound to be promulgated in such Instant Ready, up-for-grabs universes. Whose account of “In the beginning…” you believe depends on who you are within the tribe. History, we’re reminded, is the prerogative of the historian.

Reed, who lives in Lincoln, Neb. with his wife Leslie and their daughter Jessie, has largely survived on his writing earnings since 1987. There’ve been lean times when he’s lived off savings. But it’s never been so tight he’s thought of going back on the line at Mapes Industries in Lincoln, where he did the human automaton thing to support his habit. His fertile imagination and solid craft have paid off. His work has been called grim for envisioning horrific end-of-world scenarios and dire consequences of human folly.

“I’m astonished how little fright I have of my own imagination,” he said. “It really does baffle me that I don’t get more scared because I’m capable of thinking up things that are so awful. On any given day I can imagine the worst.”

Robert Reed

He’s heeded the dark side of his imagination since childhood. Already an avid reader as a kid, he tried writing a novel at 12 or 13 — filling spiral notebooks with violent monsters conjured from somewhere deep within. Playing with his buddies in a wooded area near his childhood home he’d concoct elaborate tales of creatures. At home he’d devise intricate maps of water worlds, drawing on his interest in biology, and create fantastic universes out of his head.

“I just don’t perceive things quite as other people do,” he said.

Years passed between his first stab at writing fiction and his taking it up again at Nebraska Wesleyan University. He’d stopped writing in the interim, but he never stopped reading and imagining. Ideas filled him.

“I would say, yes, they were working on me for years and years,” he said of all the stirrings that pricked at him.

It’s perhaps why when he did resume writing tales poured out of him. They’ve kept coming, too. He’s up to 160 stories and 11 novels. When someone finds the success Reed has — published in all the major SF anthologies and nominated for the field’s top prizes — one asks why he isn’t a household name?

“I’m pleased by my following, what there is of it, but science fiction is really a rather tiny business compared with its giant cousin, which is fantasy,” he said.

Then there’s the fact that while some Reed works have been optioned by filmmakers, none have made it to the screen. He doesn’t much seem to care. He doesn’t do book tours and he attends few SF conventions. And, unlike most successful SF writers whose work is tenaciously grounded in some consistent vision of the future, Reed is apt to apply entirely new suppositions from story to story.

“It doesn’t help build a fan base doing that. There’s many ways in which I’ve separated myself from the rest of the business and from my readers,” he said, adding one advantage to being an outsider is — “I think I often come up with fresh perspectives on old storylines.”

It’s true this avid long distance runner prefers to stay apart from the pack, but then there’s his big, loud web site, www.robertreedwriter.com, that two huge fans created and maintain. Reed said he doesn’t feel he would have won the coveted Hugo without the site’s props. A Billion Eves, which appeared in Asimov’s Science Fiction, can be read there. A complete bibliography of his work is available online.

Related articles

- NPR’s New Poll: “Best Science Fiction, Fantasy Books? You Tell Us” (underwordsblog.com)

- The Joy of Alt Fiction (paulcornell.com)

- The sword is mightier than the laser gun – or is it? from Stargazer’s World (stargazersworld.com)

“Walking Behind to Freedom” – A musical theater examination of race

I don’t see a huge amount of live theater, but I attend more than enough shows to give me a good feel for what’s out there. My hometown of Omaha has a strong theater scene and one of the more dynamic works I’ve seen here in recent years came and went without the attention I felt it deserved. It was called Walking Behind to Freedom, and it deal head-on with many persistent aspects of racism that tend to be trivialized or distorted. The fact that a fairly serious piece of theater dared to tackle the issue of race in a city that has long been divided along racial lines took courage and vision. Playwright Max Sparber, a former colleague and editor of mine at The Reader (www.thereader.com) based the play, which unfolds in a series of vignettes, on interviews he did with folks from all races around the community. He asked people to share experiences they’ve had with racism and how these encounters affected them. A local musical group called Nu Beginning wrote songs and music that expressed yet more layers of insight and emotion behind the dramatized experiences. A diverse group of cast and crew collaborated on a rousing, moving, thought-provoking night of musical theater. I had a personal investment in the show, too, in that my partner in life played a couple different speaking parts. She was quite good. My story about the show appeared in The Reader.

“Walking Behind to Freedom” – A musical theater examination of race

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The subject of race is like the elephant in the room. Everybody notices it, yet nobody breathes a word. The longer the silence, the more damage is done. Seen in another light, race is the label comprising the assumptions and perceptions others project on us, soley based on the shade of our skin or sound of our name. Seeing beyond labels sparks dialogue. Stopping there erects barriers to communication.

Race is as uncomfortable to discuss as sex. Yet, attitudes about race, like sex, permeate life. It’s right there, in your face, every day. You’re reminded of it whenever someone different from you enters your space or you’re the odd one out in a crowd or issues of profiling, preferences and quotas hit close to home.

It often seems Omaha’s predominantly white population wishes the topic would go away in a weary — Oh, didn’t-we-solve-racism-already? tone — or else makes limp liberal gestures toward more inclusion. Then there’s the majority reaction that pretends it’s not a problem. Take the Keystone neighborhood residents now opposing the Omaha Housing Authority’s planned Crown Creek public housing development. Opponents never mention race per se, but it’s implicit in their expressed concerns over property values being adversely affected by public housing whose occupants will include blacks. Nothing like rolling out the old welcome wagon for people trying to get ahead.

On the other side of the fence, militant minority views claim that race impacts everything, as well it might, but such sweeping indictments alienate people and chill discussion. How much an issue race is depends on who you are. If you have power, it’s not on your radar, unless it’s expedient to be. If you’re poor, it’s a factor you must account for because someone’s sure to make you aware of it.

If you doubt Omaha is beset by wide rifts along racial lines, you only need look at: its pronounced geographic segregation; its mainly white police presence in largely Latino south Omaha and African-American north Omaha; its rarely more than symbolic multicultural diversity at public-private gatherings; its few minority corporate heads and even fewer minority elected public officials. Then there’s the insidious every day racism that, intentionally or not, insults, demeans, excludes.

It’s in this climate that, last fall, Omaha Together One Community (OTOC) said: We need to talk. A faith-based community organizing group focusing on social justice issues, OTOC commissioned an original musical play, Walking Behind to Freedom, as a benefit forum for addressing the often ignored racial divide in Omaha and the need for more unity. It’s the second year in a row OTOC’s staged a play to frame issues and raise funds. In 2003, it presented a production of Working, the Broadway play based on the book of the same name by Studs Terkel.

With a book by Omaha playwright Max Sparber and music by the local quartet Nu Beginning, Walking Behind to Freedom premieres May 7 and 8 at First United Methodist Church. Performances run 7:30 p.m. each night at the church, 69th and Cass Street. Free-will donations of $10-plus are suggested. Proceeds go to underwrite OTOC operational expenses.

The play’s title is lifted from a famous quote by the late entertainer and Civil Rights activist, Hazel Scott, who posited, “Who ever walked behind anyone to freedom? If we can’t go hand in hand, I don’t want to go.” The show coincides with the 40th anniversary of Congress passing landmark Civil Rights legislation in 1964.

Max Sparber

As a foundation for the play, OTOC did what it does best: organize “house meetings” where citizens shared their anecdotes and perspectives on racial division. Sparber and Nu Beginning attended the meetings, held at OTOC-member churches city-wide, and the ensuing conversations informed the non-narrative play, which is structured as a series of thematic monologues, dialogues and songs.

“I built my script based on some of these interviews, along with some broader themes,” said Sparber, whose Minstrel Show dealt with an actual lynching in early Omaha. “We got some great stories out of it. The people who came to the meetings were very interested in the subject and I certainly got some stories that were invaluable. More than anything, we wanted this play to be specific to Omaha, and therefore we wanted its origins to be within Omahans’ own experiences.”

Surfacing prominently in those sessions was the theme of division and how by going unspoken it only deepens the divide. “This is a town that’s very separated geographically. The majority of blacks live in north Omaha. The majority of Latinos live in south Omaha. The majority of whites live in west Omaha. And, as a result, there’s not a lot of crossover,” Sparber said. “It’s really sad how closed up Omaha is,” said the play’s director, Don Nguyen, lately of the Shelterbelt Theater.

“Along with that, race is quickly becoming an undiscussed element in Omaha,” added Sparber. “I think a lot of whites believe we live in a post-racism world and, therefore, it’s not a subject that needs to be addressed. Whereas, black people experience this as not being a post-racism world at all and are kind of startled by this other viewpoint. So, there’s this disconnection based on understanding.”

|

Two lines in the play comment on this dichotomy: “I think a lot of white people feel that racism ended in the Sixties, with Martin Luther King. The only thing about racism that ended in the Sixties WAS Martin Luther King.”

Any impression all the work is done alarms Betty Tipler, an OTOC leader. “A lot of us are in our comfortable spaces. We go inside our houses with our two garages and we think things are okay. Things are not okay. The issue of race has not been cured and, if we’re not careful, things will go backward,” she said. Despite the illusion all’s well, she added, the play reminds us people of color still contend with bias/discrimination in jobs, housing, policing. “We may as well face it.”

According to OTOC leader Margaret Gilmore, the process the play sprang from is at the core of how the organization works. “We’re about bringing different people in conversation with each other to talk about what’s in their hearts and minds,” she said. “It’s a process of learning to talk to each other and listen to each other and then seeing what we have in common to work together for change.” She said the meetings that laid the play’s groundwork crystallized the racial gulf that exists and the need to discuss it. “We don’t talk about this stuff enough. We don’t talk about it on a personal level and how it affects us, which is what I think this play gets to. When we ask the right questions and we’re willing to listen, then the experiences that people tell in their own words are dramatic and provocative.”

“It’s very important we listen to real people’s stories. The only way you can come up with the truth is to go to the people. We haven’t watered down or changed their stories, but literally portrayed them,” said OTOC’s Tipler, administrator at Mount Nebo Missionary Baptist Church, which hosted some of the house meetings.

Indeed, the vignettes carry the ring of reportorial truth to them. Most compelling are the monologues, which unfold in a rap-like stream-of-consciousness that is one part slam-poet-soliloquy and one part from-the-street-rant. Some stories resemble the bared soul testimony of people bearing witness, yet without ever droning on into didactic, pedantic sermons, lectures or diatribes. The language sounds like the real conversations you have inside your head or that spontaneously spring up among friends over a few drinks. Often, there’s a sense you’re listening in on the privileged, private exchanges of people from another culture as they describe what’s it like to be them, which is to say, apart from you.

Don Nguyen

For director Nguyen, the “real life testimonies” add a layer of truth that elevates the material to a “more powerful” plane. “I think it will definitely work for us that people know this is real. It’s not an overall work of fiction. This is real stuff.”

The misconceptions people have of each other are voiced throughout the work, often with satire. You’ve heard them before and perhaps been guilty yourself assigning these to people. You know, you see an Asian-American, like Nguyen, and you reflexively think he’s fluent in Vietmanese or expert in martial arts, some assumptions he’s endured himself. “Oh, yeah, my personal experiences definitely help me to relate,” he said. “Growing up in Lincoln I got in fights all the time. People making fun of me. Thinking I knew kung-fu or I only spoke Vietmanese, which is not true. But it’s not just the blatant racism. It’s the underlying stuff, too. Sometimes it’s not even intentional, but it’s just there. And it’s that gray stuff I think these pieces capture pretty well and that people need to hear more of.”

In the vignette Tricky, some women lay out the subtle nature of racism in Omaha. “…it’s like a fox. It’s tricky. It’s sly. You’ll be standing in line at a store, and the cashiers will be helping everybody except you…and you’re the only black person in line…and because it’s so sly, I think white people don’t notice it at all.”

The play also looks at racism from different angles. One has a guilt-ridden realtor rationalizing the unethical practice of steering, which is another form of red lining. The other has a new generation bigot defending his right to espouse white pride in response to black heritage celebrations. The concept of reverse racism is explored in the real life case of students protesting their school’s special recognition of black achievers at the expense of other minorities. And the wider fallout of racism is examined in the confession offered by an insurance agent, who reveals rates for car-house coverage are higher for residents of largely black north Omaha, including whites, because of the district’s perceived high crime rate.

The vignettes touch on ways race factors into every day life, whether its the unwanted attention a black couple attracts while out shopping or the hassle African-American men face when driving while black, or DWB, which is all it takes to be stopped by the cops. The shopping piece uses humor to highlight the absurd fears that prompt people to act out racist views. Music is used as heightened counterpoint to the boiling frustration of the DWB victim, whose cries of injustice are accompanied by the soulful strains of doo-wop singers.

Bridging the play’s series of one-acts are songs by Nu Beginning, whose music is a melange of hip-hop, R & B, soul, pop and gospel. A little edgy and a lot inspirational, the music drives home the unity message with its uplifting melodies, which are sung by choruses comprised of diverse singers.

Some pieces are heavier or angrier than others. Some are downright funny. And some, like Mirrors, speak eloquently and wittily to the concept of how, despite our apparent differences, we are all reflections of each other. Here, Nguyen employs a diverse roster of performers to represent the mirror symbol. Perhaps the most telling piece is Function. This beautifully-rendered and thought-provoking discourse is delivered by an architect, who suggests racism has survived as both an ornament of the past, akin to a Roman column on a modern house, and as a still-functional device for those in power, as when a politician plays the race card.

Whatever the context, there’s no dancing around the race card, which is just how Nguyen likes it, although when he first read the script he was surprised by how brazenly it took on taboo material, such as its use of the N-word.

“Typically, a script or show sugarcoats the issue of race. It’s a very cautious topic. You don’t want to offend or patronize people by saying the wrong stuff. But this piece is much different. All of its pretty much in your face,” Nguyen said. “What I mean is, it’s very direct. Max (Sparber) makes no bones what he’s writing about, which is great. It’s a big risk to take as a writer, but essentially it’s the most interesting path to take, too. And I’m all for stirring up trouble. I’m fine with that.”

OTOC’s Betty Tipler feels racial division is too important an issue to be coy about. “We’ve got to come out of the closet, so to speak, and talk about racism and differences” she said. “We tend to shy away from talking about it, but it won’t go away. We have got to come together, put it on the table, take a look at it and deal with it — no matter how much it hurts me or how much it hurts you. But before we can do that, we’ve gotta put it out there. We won’t get anywhere until we do. And I believe this play is a step toward doing that.”

Christy Woods, a singer/songwriter with Nu Beginning, said the play is about hope. “I believe if people are open to change, we can go hand-in-hand to freedom. Just because I’m this and you’re that, doesn’t mean I have to be one step behind you. Why can’t we go together? We want people to feel inspired to go out and make a change. We want to touch, but also to teach, and I believe this musical does that.”

Nguyen hopes the play attracts a mixed audience receptive to seeing race through the prism of different experiences. “That’s where I’m trying to aim the show. As we go through these vignettes, I want some people to identify with them and some people to be like, ‘Oh, I didn’t know that.’ That’s what I want to create.”

Related articles

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Kevyn Morrow’s Homecoming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Native Steve Marantz Looks Back at the City’s ’68 Racial Divide Through the Prism of Hoops in His New Book, ‘The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Hey, You, Get Off of My Cloud! Doug Paterson – Acolyte of Theatre of the Oppressed Founder Augusto Boal and Advocate of Art as Social Action (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Theater as Insurrection, Social Commentary and Corporate Training Tool (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Polishing Gem: Behind the Scenes of the Beasley Theater & Workshop’s Staging of August Wilson’s ‘Gem of the Ocean ‘ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

What happens to a dream deferred? John Beasley Theater revisits Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun”

It’s only in the last few years I finally saw both a stage production and a television production of the classic play A Raisin in the Sun, and while I found each impressive, the thing that really turned me onto the work was reading Lorraine Hansberry’s famous work. Its intensity and truth burn on the page. After reading the play I knew I had to see a performance of it, and that motivation is what led me to write the following piece for The Reader (www.thereader.com). When I was still in the good graces of Omaha’s Beasley Theater’s I watched part of a rehearsal there and then saw a performance of the play in its entirety. Not too far removed from that experience I caught the TV version with Phylicia Rashad, Sanaa Lathan, Audra McDonald, and Sean Combs. The themes of Raisin resonate with me on many levels, but it is its dramatic interpretation of the Langston Hughes line, “What happens to a dream deferred?” within the context of a man and family struggling to get their small piece of the American Dream that deeply affects and disturbs me.

Ruby Dee and Sidney Poitier from the 1961 film adaptation of Hansberry’s play

What happens to a dream deferred? John Beasley Theater revisits Lorraine Hansberry‘s “A Raisin in the Sun”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

After its 1959 opening at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre in New York, A Raisin in the Sun was the talk of Broadway and the play’s 28-year-old author, the late Lorraine Hansberry, was the toast of the theater world. Hansberry became the first black whose work was honored with the New York Drama Critics Circle’s best play award.

The Youngers, a poor, aspiring black Chicago tenement family, are the prism through which she looks at the experience of oppression in segregated USA. Her modern story of assimilationist pressures and deferred dreams offers a realistic slice of black life unseen till then. The politically-aware Hansberry, who studied under W.E.B. DuBois and wrote for Paul Roberson’s Freedom magazine, took the play’s title from a Langston Hughes poem that asks: “What happens to a dream deferred. Does it dry up, like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore…Or does it explode?”

Lena is the stalwart, widowed matriarch holding her family intact. Ruth, the eldest daughter, is the beleaguered wife of Walter, a bitter chauffeur striving to move up in the world. Beneatha, Ruth’s younger sister, is a collegian who rejects God and embraces Africa. Her hopeful beau, George Murchison, is the bourgeois American counterpoint to her sweet-on admirer, Joseph Asagai, a politically-minded Nigerian.

When the prospects of a fat insurance check threaten tearing the family apart, Lena acts rashly and buys a house in a restricted white neighborhood. Then, just as Walter’s dreams of owning a business are crushed, the alarmed residents offer the Youngers a buy-out. What Walter will do next is at the crux of the family crisis.

With its successful Broadway revival in 2003-04, Raisin proves its themes are still relevant today and that’s one reason why the John Beasley Theater is staging it now through October 10. While not revolutionary, Raisin reveals some hard truths.

“What we have for the first time with Hansberry in the ‘50s is a dignified, realistic portrayal of the complexities of black life,” said poet and essayist Robert Chrisman, chair of the Department of Black Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha and founding editor of The Black Scholar. “With Walter, you have the young black man who wants his chance. Mama (Lena) represents the stolid, powerful, tenacious will of black people to keep on keeping on. She is the moral center of the play. These are all realistic, engaging portraitures of black people. You don’t have any stereotyped servants. I think dignity is key in Raisin because it’s finally to assert his fundamental human dignity Walter turns down the buy out.”

For Chrisman, “the single strongest theme in Raisin is the tenet that if you have your dignity, you have the potential for everything and if you do not maintain and courageously uphold your dignity and freedom as a human being, you have nothing. And I think all of that was new in the portraiture of blacks in white theater. What preceded it up to the 1950s was usually something based on the minstrel-entertainment genre — the shuffling chauffeur, the maid, the bell hop, the clown. In black theater you had legitimate efforts at portraying blacks, but I think it’s with Hansberry you get the breakthrough. She sets the stage for the subsequent work of August Wilson and Charles Fuller, who deal with issues of generations, dreams and career aspirations and frustrations. In a way, she did for modern black drama the same thing that Richard Wright did for the modern black novel.”

Directing the Beasley production is UNO dramatics arts professor Doug Paterson, who said the play “became the springboard for black theater” in the latter half of the 20th century. “Black theater exploded in all kinds of directions,” he said. He added that the militant dramatists who followed Hansberry, such as Amiri Baraka, were critical of her “drawing room kind of drama” when they “felt what was necessary was to be bold…different…experimental.” However, Chrisman reminds, “Baraka was writing at the cusp of the ‘60s and the movement of this more militant vision forward. I think what Hansberry is saying is that whether Walter goes down as a freedom rider or starts a riot is immaterial. Asserting his dignity is what matters.”

Although it stops short of radical redresses to racism and inequality, her work is full of red hot anger and indignation. Paterson said, “She revealed so much. She anticipated sort of everything that happened in civil rights, black power and integration.” He said the original production was also influential in terms of the contributions to American theater and film that its cast and crew have made. Among the lead actors, Sydney Poitier, Ruby Dee, Claudia McNeil, Ivan Dixon and Louis Gossett are household names. Douglas Turner Ward is a co-founder of the Negro Ensemble Theater. Lonne Elder III is a major playwright. Director Lloyd Richards is perhaps Broadway’s most acclaimed dramatic interpreter. “It’s an extraordinary play for what it did historically. That’s why we study it,” said Paterson, who’s taught it for years. “I always wanted to give it a shot” directorially.

Chrisman well recalls the impact of the 1961 film version, whose adaptation Hansberry wrote. “There was a tremendous surge of pride and dignity in audiences,” especially black audiences, at the time. The concerns of Raisin, he said, still reverberate today. “I think in some ways it’s still very contemporary because you still have the same kind of interest in the African experience that Beneatha had in young folks today. And you still have, perhaps even more desperately, the need of the young black man to start a business of his own.”

The play ends with the Youngers deciding to move where they’ll clearly be unwelcome, but it doesn’t show the struggle of blacks living in a white enclave organized to oust them. As Chrisman said, “There should be a sequel to it, because it ends on the affirmative note…You could have another play that shows the ostracism, harassment, graffiti, coldness and so on that have been reported by first-generation integrating blacks.” And that’s ironic, as the playwright’s own family underwent that very trial by fire when she was a young girl. Her educated parents were social activists in Chicago and when their move into a white section met with resistance, they fought the injustice all the way to the Supreme Court.

For her next play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, Hansberry disappointed some by telling a Jewish story. She died of cancer, at age 34, the day that play closed on Broadway. Other works were posthumously adapted into books and plays by her former husband, Robert Nemiroff, a writer and composer. In 1973, Nemiroff and Charlotte Zaltzberg adapted her first play into the Tony-winning musical Raisin.

Related articles

- Philip Rose, ‘Raisin’ and ‘Purlie’ Producer, Dies at 89 (nytimes.com)

- Anthony Chisholm is in the House at the John Beasley Theater in Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Hansberry Project honors Regina Taylor (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Alicia Keys helping produce a Broadway play (ctv.ca)