Archive

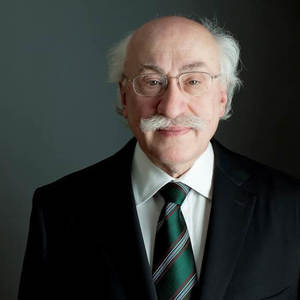

Ted Genoways Gives Voice to Rural Working Class

Ted Genoways

Gives Voice to Rural Working Class

Photography by Bill Sitzmann

Originally appeared in July-August 2018 issue of Omaha Magazine ( http://omahamagazine.com/articles/ted-genoways/)

Award-winning poet, journalist, editor, and author Ted Genoways of Lincoln, Nebraska, has long been recognized for his social justice writing as a contributor to Mother Jones, onEarth, Harper’s and other prestigious publications. While editor of the Virginia Quarterly Review, the magazine won numerous national awards.

His recent nonfiction books—The Chain: Farm, Factory and the Fate of Our Food, and This Blessed Earth: A Year in the Life of an American Farm—expand on his enterprise reporting about the land, the people who work it, and the food we consume from it. The themes of sustainability, big ag versus little ag, over-processing of food, and environmental threats are among many concerns he explores.

He often collaborates on projects with his wife, photographer Mary Anne Andrei.

His penchant for reporting goes back to his boyhood, when he put down stories people told him, even illustrating them, in a stapled “magazine” he produced. His adult work took root in the form of secondhand stories of his paternal grandfather toiling on Nebraska farms and in Omaha meatpacking plants.

His father noted this precociousness with words and made a pact that if young Ted read a book a week selected for him, he could escape chores.

“I thought that was a great deal,” Genoways says. “Reading John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men was the first time I remember being completely hooked. After that, I tore through everything Steinbeck wrote, and it made a huge impact on me. I thought, there’s real power in this—if you can figure out how to do it this well.”

Reading classics by Hemingway, Faulkner, and other great authors followed. The work of muckrakers such as Upton Sinclair made an impression. “But those Steinbeck books,” he says, “have always really stuck with me, and I go back to them and they really hold up.”

Exposing injustice—just as Steinbeck did with migrants and Sinclair did with immigrants—is what Genoways does. Nebraska Wesleyan professors Jim Schaffer and the late state poet of Nebraska William Kloefkorn influenced his journalism and poetry, respectively. Genoways doesn’t make hard and fast distinctions between the two forms. Regardless of genre, he practices a form of advocacy journalism but always in service of the truth.

“I’m always starting with the facts and trying to understand how they fit together,” he says. “There’s no question I’ve got a point of view. But I don’t show up with preconceived notions of what the story is.”

He’s drawn to “stories of people at the mercy of the system,” he says, admitting, “I’m interested in the little guy and in how people fight back against the powers that be.”

While working at the Minnesota State Historical Society Press, Genoways released a book of poems,Bullroarer: A Sequence, about his grandfather, and edited Cheri Register’s book Daughter of a Meatpacker. At the Virginia Quarterly, he looked into worker illnesses at a Hormel plant in Austin, Minnesota, and the glut of Latinos at a Hormel plant in Fremont, Nebraska. He found a correlation between unsafe conditions due to ever-faster production lines—where only immigrants are willing to do the job—and the pressures brought to bear on company towns with influxes of Spanish-speaking workers and their families, some of them undocumented.

That led to examining the impact “a corporate level decision to run the line faster in order to increase production has up and down the supply chain” and on entire communities.

“That’s become an ongoing fascination for me,” Genoways says. “I can’t seem to stop coming back to what’s happening in meatpacking towns, which really seem to be on the front line of a lot of change in this country.”

The heated controversy around TransCanada Corp.’s plans for the Keystone XL pipeline ended up as the backdrop for his book, This Blessed Earth. He found “the specter of a foreign corporation coming and taking land by eminent domain” from legacy farmers and ranchers “and telling them they had to take on this environmental risk with few or no guarantees” to be yet another challenge weighing on the backs of producers.

His focus became a fifth-generation Nebraska farm family, the Hammonds, who grow soybeans, and how their struggles mirror all family farmers in terms of “how big to get and how much risk to assume.”

“They were especially intriguing because they were building this solar and wind-powered barn right in the path KXL decided to cross their land, and that seemed like a pretty great metaphor for that kind of defiance,” he says.

Pipeline or not, small farmers have plenty to worry about.

“Right now, everything in ag is geared toward getting bigger,” Genoways says. “The question facing the entire industry is: How big is big enough? What do we lose when we force farmers off the land or make them into businessmen more than stewards of the land? To my eye, you lose agri-CULTURE and are left with agri-BUSINESS.”

Farming as a way of life is endangered.

“Nebraska lost a thousand farms in 2017,” he says. “Those properties will be absorbed by larger operations. The ground will still be farmed. The connection between farmer and farm will be further stretched and strained. That’s the way everything has gone, and it’s how everything is likely to continue. Agribusiness interests argue these trends move us toward maximum yield with improved sustainability. But it also means decisions are made by fewer and fewer people. Mistakes and misjudgments are magnified. So we not only lose the culture of independence and responsibility that built rural communities, but grow more dependent on a version of America run by corporations.”

Chronicling the Hammonds left indelible takeaways—one being the varied skills farming requires.

“We saw them harvest a field of soybeans while keeping an eye on the futures trading and calling around to elevators to check on prices; they were making market decisions as sophisticated as any commodities trader,” Genoways says. “This is one of the major pressures on family farms. To survive, you have to be able to repair your own center pivot or broken tractor, but also be a savvy business owner—adapting early to technological changes and diversifying to insulate your operation.”

The Hammonds weathered the storm.

“They are doing well. They got good news when the Public Service Commission only approved the alternate route for KXL,” he says.

Meanwhile, Genoways sees an American food system in need of reform.

“We would benefit mightily from a national food policy,” he says. “How can you explain subsidizing production of junk food and simultaneously spending on obesity education? How do we justify unsustainable volumes of meat while counseling people to eat less meat? If we really want people to improve their eating habits, we should provide economic incentives in that direction.”

Visit tedgenoways.com for more information.

This article was printed in the July/August 2018 edition of Omaha Magazine.

Life Itself IX: Media and related articles from the analog past to today’s digital era

Ariel Roblin

Mike Kelly

Doug Wesselmann, aka Otis Twelve

Journalist-author Genoways takes micro and macro look at the U.S, food system

Journalist-author Genoways takes micro and macro look at the U.S, food system

©by Leo Adam Biga,

Originally published in the Summer 2018 issue of Food & Spirits Magazine (http://fsmomaha.com)

It should come as no surprise that a writer who chronicled a year in the life of a Nebraska farm family, exposed the dangers of a broken American food system and is now researching Mexico’s tequila industry has always marched to the beat of a different drummer.

Growing up, Ted Genoways was encouraged to read books well beyond his years by his natural museum administrator father, Hugh H. Genoways. That was okay with the youngster because he liked reading, even though it took his dad makiing a bargain with him to replace comic books with classics.

The great American interpreter of the common man’s struggles, author John Steinbeck, became an inspiration for Genoways and remains so today. The exposes of muckrakers such as Upton Sinclair further lit a fire in him – that still burns – to stand up for the underdog.

“I just recently got fascinated by the work done by the ‘Stunt Girls,’ the forerunners of the muckrakers and the first undercover investigators. Their whole notion was to get into spaces hidden from public view and write about what was going on there in order to bring public pressure to bear and change conditions.”

Following in the footsteps of these socially conscious writers, Genoways has documented the hardships facing small farmers, migrants and immigrants and he’s explored the effects of big ag on towns and families.

Storytelling has captivated him for as long as he can remember. “Strangely fascinated” by the stories others told him, Genoways developed a habit of writing them down and illustrating them, a precursor to the student journalism he practiced in high school and college and to his career today as journalist and author.

Some of the stories he heard as a boy that most captured his imagination concerned his paternal grandfather’s experiences working on Nebraska farms and in Omaha meatpacking plants. Though Genoways hails from an urban background, this city boy has repeatedly turned to rural reaches for his work. After all his travels, including a short stint in Minnesota and a decade-plus back east as editor of the Virginia Quarterly Review, Lincoln, Nebraska is where he now calls home.

His father’s work meant a nomadic life for Genoways. He was born in Lubbock, Texas and grew up in the North Hills of Pittsburgh, where the family stood out both for lack of want and for the title, Dr., his Ph.D. father carried. Most of his friends and schoolmates were the sons and daughters of blue-collar working parents, some of whom were laid off by the mills and struggling to get by. By contrast, his father was curator of mammals at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

When the elder Genoways accepted the directorship of the Nebraska State Museum, the family moved to Lincoln in 1986. At Lincoln East High School, Genoways found in Jim Schaffer the first of two crucial mentors in his foundational years as an aspiring published writer.

“Jim was our journalism teacher and the publications advisor,” said Genoways, who with some fellow students and the encouragement of Schaffer founded a school magazine, Muse. Only three years after its launch the Columbia School of Journalism named it the nation’s best high school publication.

“That whole experience of working on that magazine was really formative. It was also a case where because we were all so new to that stuff, we didn’t think a lot about genre distinctions. We were all writing fiction and poetry and descriptive pieces and to whatever extent a high school student can we were trying to report on things that seemed to be of broader significance – national issues and things relevant to the school.”

Muse getting singled-out resulted in Genoways and his classmates going to New York to accept the Columbia recognition. By virtue of Schaffer working on a dissertation about baseball columnist Roger Angell, the Nebraska group got entree to visit the legend at his New Yorker magazine office during their Manhattan trip.

“It was quite an experience. We went also to Spy Magazine, which we were interested in because one of the editors, Kurt Andersen, was from Omaha.”

Three decades later, Genoways is now the established professional emerging young writers seek out.

All in all, he said Muse proved “definitely an important beginning point for me.”

It worked out that Genoways and Schaffer matriculated to Nebraska Wesleyan University at the same time – to study and teach, respectively. Again, with Schaffer’s blessing, Genoways founded a magazine, Coyote.

“It was more ambitious and probably more openly irreverent,” Genoways said. “It was something we really enjoyed. it was a great incubator for just trying out all kinds of ideas and really seeing what a magazine could be.”

At Wesleyan, Genoways found another key influence in the late state poet William Kloefkorn.

“To have an interest as I did in both the literary side and the journalistic side and then getting to work with Bill Kloefkorn at Nebraska Wesleyan while also working with Jim there was really ideal. I’ve had a lot of great teachers over the years, but I think it would be pretty impossible to match the kind of wisdom and knowledge Bill had with that incredible generosity. He was always teaching and always glad to share his thoughts with young people who were wanting to know more. I feel really lucky to have had somebody like that at a point when I was just getting started.”

Genoways soaked it all in.

“I was an English major with a creative writing-poetry emphasis and thesis but was a journalism minor. I would say over time my interests and my work have moved back and forth between those things. But I don’t see them as all that different. I mean, my first book of poems, Bullroarer, was kind of a reimagining of the life of my grandfather, who worked in a meatpacking plant in Omaha when he was young, and that definitely was part of what got me interested in investigating the meatpacking industry and writing the book The Chain (Farm, Factory and the Fate of Our Food).”

A particular story oft-told by the author’s father influenced Genoways eventually writing The Chain.

“When my dad was a kid. the family came to Fort Calhoun for Easter. And for whatever reason, his father thought it would be a good idea to show him where the Easter ham comes from. The story is that my grandfather worked in the Swift packinghouse, He took him into the kill floor there. My father said he didn’t know exactly what his dad was thinking taking an 8 or 10 year old kid to see the hogs being slaughtered, but it made a real impression on him.”

As an adult, Genoways sees an interconnected tood system full of health hazards that span the planting, fertilizing and harvesting of the grain that feeds livestock to the ways animals are housed, killed and processed.

“The Chain was this whole idea of wanting to see this go from seed to slaughter.”

More family lore has spurred his work.

“My grandfather’s upbringing during the Great Depression and landing out in western Nebraska on a farm and raising my dad out there was a big part of what was behind writing This Blessed Earth (A Year in the Life of an American Family Farm). That’s the reason there’s kind of a coda at the end, where I go back to some of those places I remember from my childhood with my dad – but now with a new understanding of all the pressures my grandfather had been under and all the factors that had helped shape my dad’s childhood.

“So to me it’s all part of the same work – it’s just different ways of approaching it and reaching different audiences. But also I suppose kind of testing out what medium and what approach works best for different kinds of material.”

He has used literary journalistic prose and straight investigative reporting for examinations of unsafe, unsanitary conditions at Hormel hog plants in Austin, Minnesota and Fremont, Nebraska and animal abuse in Iowa and for his delineation of challenges facing small family farmers. His work has appeared in Mother Jones, OnEarth, Harpers and other national magazines.

“As much as I love the pure activity of the research and writing, my hope always is it does more than just entertain and inform. I would hope it’s also shining a light on issues people hadn’t thought about before and making them see the world in a different way and maybe moves them to want to do something about injustices of the world. There’s no question I’ve got a point of view. It’s one of the reasons magazine journalism, which traditionally is more forgiving on those sorts of things, feels like the right place for me.”

Genoways doesn’t shy away from showing his sympathies for the average Joe or Jill who get the shaft from big money forces beyond their control.

“I’m always starting by seeing a complex of issues or events I think are worth investigation. I always feel like what i can contribute to the conversation is constantly saying it’s not simple – here’s another complex dimension of that. I’m interested in exposing the mechanisms of systems to show how things are stacked against the little guy. So my interest is in leveling the playing field and making sure everybody gets a fair shake. But that’s really as far as my philosophy extends. I don’t have a big political agenda.”

His reporting in meatpacking company towns revealed sped-up productions lines whose workers. many illegal. suffer more injuries and illnesses. He also shed light on predominantly white Fremont’s racially-charged stands and measures to make life inhospitable for undocumented workers and their families.

Finding packers willing to talk to him can be a challenge, but he said he’s hit upon a reliable strategy of reaching out to “whoever in the community is advocating on behalf of the workers,” adding, “There’s all these nonprofits providing interpretive services or medical help or helping navigate the immigration process.” In Austin, Minnesota, where workers suffered a neurological disorder from exposure to an aerosolized mist created from liquifying hog brains, he developed enough rapport with the afflicted that he got several to sign waivers.

“That waiver allowed the state-appointed social worker for this case to turn over her records and the release of their medical records. Having these monthly reports on their progress created a timeline, a kind of verifiable trajectory for their symptoms and illness. It also then allowed me to have this record of dates to go back to the workers themselves and jog their memories. It also opened up other kinds of conversations.”

Since paranoid management makes on-site journalist observations at any plant next to impossible, Genoways finds other ways to recreate what goes on there.

“The central problem of working on anything with meatpacking is you’re almost certainly not going to see the workplace, and so you have to kind of reconstruct it from what the workers can describe but then also try to find whatever you can in the way of documentary evidence to go with that.

“in addition to second-hand accounts from line workers and supervisors,” he said “ideally I try to get applicable government inspection records and reports of problems documented at those places. so it’s a lot of triangulation rather than direct access. To me, the process is interesting. Anytime someone tries to drop the curtain to conceal what’s going on somewhere, it feels like the place we should be going and trying to see what is behind the curtain. It’s an indicator there’s something going on we should be paying attention to.”

He suggests instead of companies investing in mega security to keep prying eyes out “money might be better spent changing processes and policies so you don’t have to worry about public scrutiny.”

He and photographer wife Mary Anne Andrei have worked on magazine and book projects together.

“I love working with Mary Anne. We seem to have some kind of built-in radar that allows us to be focused on our part of the project while remaining attuned to what the other person needs. That communication means Mary Anne is asking questions in interviews and I’m sharing what I see as she’s getting shots. It’s a true collaboration.”

In the Hammonds, they found a tight-knit, fifth-generation farm clan now growing soybeans who defied a proposed TransCanada Keystone XL pipeline route to have cut right through their property.

“Our interest really got ramped up when the neighbor to the south of them who had been renting them two quarters of ground for many years said, ‘I don’t agree with this stance you’ve taken and I’m not going to allow you to farm this ground anymore.’ The Hammonds took a real financial hit from having expressed this strong opposition to the pipeline and that was the point at which we said we’d like to spend a year as your family works to deal with struggling to make ends meet when you’ve taken a stand like that.”

Genoways saw the family as a symbol for thousands jlike them.

“They embodied so many of the challenges of modern farming as well as struggles that all family farms are up against — how big to get, how much risk to assume.

Things just kept stacking up, Prices bottomed out

There were all sorts of new pressures. And to their great credit Rick Hammond and his daughter Meghan and her fiance Kyle all said, ‘We’ve committed to doing this, we’ll stick it out. We want people to see what it’s really like here – what the stresses are.’ So they let us follow them around for that year, It was a tremendous commitment on their part and they really hung in there with us, even in times that were incredibly stressful for them.

“I hope that openness they exhibited translates into something that allows people to see just what that life is really like.”

Genoways recently returned from a trip south of the border for research on his new book, Tequila Wars: The Bloody Struggle for the Spirit of Mexico.

Visit http://www.tedgenoways.com.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at https://leoadambiga.com.

SOME MORE OF MY COVER STORIES THROUGH THE YEARS AND ONCE AGAIN YOU CAN SEE JUST HOW DIVERSE MY SUBJECTS ARE

Playwright turned history detective Max Sparber turns identity search inward

Max Sparber channeling his inner Buffalo Bill, ©photos by Debra S. Kaplan

Playwright-journalist-blogger-historian Max Sparber has a knack for reinventing himself borne from a lifelong search for identiity, though he’s recently found more clarity where his family roots are concerned. He’s always known he was an adoptee but it’s only in the last year or so he’s discovered specifics about his biological parents. Long before he began searching out his biological mother’s and father’s stories, he was intrigued by history and heritage and much of his writing for publications and for the stage has dealt with matters of cultural inheritance or perception. It’s no wonder he find himself in the day job he works today as research specialist with the Douglas County (Neb.) Historical Society. The very tools he uses there to help people search their family history are the ones he utilizes in his own personal family search. Sparber is Irish and English but he was raised Jewish and he is steeped in that culture. He has written about Africa-Americans and race in his plays “Minstrel Show” and “Walking Behind to Freedom” and he’s the author of a blog, “The Happy Hooligan,” devoted to what it means to be Irish-American. In truth, he’s written about a wide range of people and subjects and always with same incisive and sensitive eye of the outsider. His new play, Buffalo Bill’s Cowboy Band, deals with a historical figure, William Cody, who simiarly dealt with issues of identity and reinvention. My profile of Max for The Reader (www.thereader.com) follows below.

As a side note, Max has been a longtime contributor to The Reader as I have. At one point he became the arts editor there and for a brief time served as managing editor. Another superb Omaha writer I’ve written about, Timothy Schaffert, had a similar experience at The Reader.

Oh, and by the way, I wish I had thought of it when I wrote the story, because I would have included it in the piece, but it occurs to me that Max bears an uncanny resemblance to silent film comedian Harold Lloyd.

Playwright turned history detective Max Sparber turns identity search inward

New play about Buffalo Bill explores similar reinvention issues as his own

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

As an adoptee whose identity quest has shaped his life and as a research specialist investigating people’s family trees, Max Sparber perfectly embodies his “history detective” tagline.

His Douglas Country Historical Society fact-finding duties feed his work as journalist-blogger-playwright of wide-ranging interests, from Irish-American culture-history to early Omaha infamy to social justice. Then there’s his thing for singing cowboys, the Old West and everything theatrical. All of which makes him the ideal dramatist for Buffalo Bill.

Sparber’s whimsical new play Buffalo Bill’s Cowboy Band, showing through February 8 at the Rose Theater, is a Victorian era-inspired musical revue-meets-chautauqua whose identity themes resonate with his own Who-am-I-this-time? life story.

“I definitely think this has a lot to do with my own search for my identity and how identities are often a sort of collective invention.”

William Cody was a scout and buffalo hunter turned entertainer. His Wild West show, first mounted in North Platte, Neb., forever changed perceptions and portrayals of the frontier.

“I think he is in some ways the basis for all contemporary cowboy stories,” says Sparber, who just as Cody cultivated a look with fancy regalia, is seldom without a vintage fedora and tinted glasses

He says the story “is really about how William Cody invented a character called Buffalo Bill as a way of telling tall tales about the West inspired by the actual history of the West.” The play, which uses Cody’s daughter Irma as fan and foil, depicts his conflict over being authentic whole taking dramatic license.

When the Rose commissioned Sparber they didn’t know about his identity search or fixation with Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. They didn’t know he’d done a children’s play, The Ukulele King’s Sunday Family Roundup, featuring his peculiar talents for twirling guns, yodeling and playing the ukulele.

That’s folderol though compared to how the skills of his trade, along with DNA testing, recently aided him, at age 46, in discovering his late birth mother’s identity.

“When I found out who my biological family was, I had exactly the tools needed to churn through that information. It would have been completely overwhelming otherwise.”

The woman who gave him life, Patricia Monaghan, followed pursuits strikingly aligned with his own. She was a journalist and author who often wrote about her large Irish-Catholic family and Celtic mythology. She wrote about and studied theater, just as Max has. He once owned one of her books.

Knowing they were kindred spirits seemed an “astonishing coincidence” he now ascribes to genetic inheritance.

“I do regret not meeting her. I’m just very glad she left behind the wealth of writing and information about herself she did. There’s a lot of people for whom there’s no record of them. Yet she’s unknowable in the sense I’ll never be able to meet her.”

He knows less about his biological father, except he studied art, as Max did.

As best Max can tell he was the unintended result of a fling.

“It turned out the circumstances of my birth were not tragic as I feared. Probably mostly I was just terribly inconvenient and I’d rather be inconvenient than the product of tragedy.”

Now that he’s gleaned things about his mother’s family from her widower and a first cousin, it’s allayed his worst-case-scenario thinking.

“There was a real concern I’d find my biological family and they’d all have tattoos of tears on their cheeks and swastikas on their arms.

Thank goodness it’s nothing like that. They’re very lovely people.”

Most of his Irish clan lives in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, though some reside in Ireland. His birth mother gained Irish citizenship and even though he’s never been there, he may be entitled to citizenship, too. He intends visiting his ancestral homeland of County Mayo.

He always knew he was not Jewish like his adoptive parents but likely Irish and English. He especially steeped himself in all things Irish, from devouring its literature to learning to play the penny-whistle. His The Happy Hooligan blog explores what it means to be Irish-American.

What he did with his heritage is not unlike what Cody did with his past.

“Being Irish is something I had to invent because I wasn’t raised with that. It was so weird for me for a long time because it felt fabricated and then I realized it’s all fabricated, We all just make up culture. We’re Irish-American because we say we are. We do Irish-American things because we’ve decided that’s what Irish-Americans do.”

He calls a year in Bath, England for a sabbatical his adoptive father made “the defining year of my childhood.”

“It was all very fascinating to me. England is a very old country with a lot of very strange old traditions. One of the things they do is ritualize and reenact history through these pageants. At school I played a Moor battling King George.”

That experience and summers in New York introduced him to the idea of history behind every door or corner.

“I realized the whole world is these little pockets of often undiscovered history. All of a sudden these places around you aren’t just houses people live in but have these entire stories behind them that you can mentally pop into. I really like that.”

Then there’s the Jewish experience he absorbed. “I’m not religious but I do feel I am culturally Jewish, I was raised in that milieu. Jews have a very complex diaspora identity, so they have all these tools for understanding what it means to be Jewish when you’re not in Israel. Irish-Americans have almost none of that.”

As a sign of things to come, the very first play he wrote was inspired by historical events – the Salem witch trials.

Ever since first coming to Omaha from his native Minneapolis, where he wrote about forgotten Minn. history, he’s drawn on Omaha’s past in his writing. His play Minstrel Show examines the infamous 1919 courthouse riot and the lynching of William Brown.

“As a dramatist I’m not interested in when people behaved well in the past, I’m interested in when they misbehaved, and this may be the greatest town in America for that.”

His blogs unearth colorful stories of Omaha’s disreputable past, including Ramcat Alley’s rough trade denizens, the Burnt District’s madams and striptease joints passing as theaters.

He similarly immersed himself in the history of Hollywood and New Orleans when he lived in those places.

He acknowledges his job with DCHS is “a perfect match.”

“I never expected I would wind-up being a professional historian and it’s so hard for me to think of myself that way but that is at the moment the road I’m on. It’s not a surprise to be here but it wasn’t planned.”

His historical writing is a treasure trove for the organization.

“I’m like this steady machine providing content they can make use of.”

He often makes DCHS presentations related to his findings and he teaches a genealogy class for folks searching their family histories.

Now that he can finally wrap his arms around his patchwork identity, he can look back, as Buffalo Bill did, and see where myth ends and reality begins. His journey’s not unlike Omaha’s own self-image problem.

“There’s a sociological concept called a sense of place – knowing where you come from and what it means to come from there – and this is what I’ve been wrestling with my entire life.”

Omaha’s bland present obscures a debauched legacy as wild frontier town and corrupt machine politics city.

“When people find out about it it’s exciting and interesting. It gives you something to connect to. It’s a very different narrative from the one Omahans are taught in schools, and it’s a shame because towns that embrace their own wild history often do very well with it.”

Follow his ever expanding family via social media, including http://happy-hooligan.blogspot.com. For play details, visit http://www.roseheater.org.

!['I only just now became aware of this fine review of my Alexander Payne book that appeared in a 2014 issue of the Great Plains Quarterly journal. The review is by the noted novelist and short story writer Brent Spencer, who teaches at Creighton University. Thanks, Brent, for your attentive and articulate consideration of my work. Read the review below.

NOTE: I am still hopeful a new edition of my Payne book will come out in the next year or two. it would feature the additon of my extensive writing about Payne's Nebraska. I have a major university press mulling it over now.

Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film—A Reporter’s Perspective, 1998–2012 by @[1690777260:2048:Leo Adam Biga]

Review by Brent Spencer

From: Great Plains Quarterly

Volume 34, Number 2, Spring 2014

In Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film—A Reporter’s Perspective 1998–2012, Leo Adam Biga writes about the major American filmmaker Alexander Payne from the perspective of a fellow townsman. The Omaha reporter began covering Payne from the start of the filmmaker’s career, and in fact, even earlier than that. Long before Citizen Ruth, Election, About Schmidt, Sideways, The Descendants, and Cannes award-winner Nebraska, Biga was instrumental in arranging a local showing of an early (student) film of Payne’s The Passion of Martin. From that moment on, Payne’s filmmaking career took off, with the reporter in hot pursuit.

Biga’s book contains a collection of the journalist’s writings. The approach, which might have proven to be patchwork, instead allows the reader to follow the growth of the artist over time. Young filmmakers often ask how successful filmmakers made it to that point. Biga’s book may be the best answer to this question, at least as far as Payne is concerned. Biga presents the artist from his earliest days as a hometown boy to his first days in Tinseltown as a scuffling outsider to his heyday as an insider working with Hollywood’s brightest stars.

If there is a problem with Biga’s approach, it is that it occasionally leads to redundancy. The pieces were originally written separately, for different publications, and are presented as such. This means that an essay will sometimes cover the same material as a previous one. Some selections were clearly written as announcements of special showings of films. But the occasional drawback of this approach is counterbalanced by the feeling you get that the artist’s career is taking shape right before your eyes, from the showing of a student film in an Omaha storefront theater to a Hollywood premiere.

Perhaps the most intriguing feature of the book is Biga’s success at getting Payne to speak candidly about every step in the filmmaking process. These detailed insights include the challenges of developing material from conception to script, finding financing, moderating the mayhem of shooting a movie, and undertaking the slow, monk-like work of editing. Biga is clearly a fan (the book comes with an endorsement from Payne himself), but he’s a fan with his eyes wide open.'](https://scontent-dfw1-1.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xpa1/t31.0-0/p480x480/11698974_10200574953971575_7380164938074896068_o.jpg)

!['MORE AFRICA TALES MEDIA

I joined @[1619391711:2048:Jamie Fox Nollette] and @[100001709629160:2048:Terence Crawford] for a taping of KETV's "Chronicle" public affairs program with host Rob McCartney. Stay tuned for the date and time when the show will air. Photo courtesy KETV.'](https://scontent-dfw1-1.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xat1/t31.0-8/s720x720/11895041_10200655434463537_2065898640647327480_o.jpg)

!['Pam, having enchilidas tonight with our friends @[584511938:2048:Linda M. Garcia Perez] and @[1567029979:2048:Jose Francisco Garcia]. I couldn't make it. Hoping they send her home with an extra enchilida. Enjoy honey.'](https://scontent-dfw1-1.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xtf1/v/t1.0-0/q83/s600x600/11038864_10200740278184577_2799446387615869609_n.jpg?oh=d47ee16d9958b2334f2f82ccc58b1b0b&oe=57115A87)

!['HOMETOWN HERO TERENCE CRAWFORD ON VERGE OF GREATNESS AND BECOMING BOXING'S NEXT SUPERSTAR

When hometown hero and reigning WBO world welterweight champion @[100001709629160:2048:Terence Crawford] takes care of business as expected against challenger Dierry Jean Saturday night (Oct. 24) at the CenturyLink, everything then opens up for him. The scuttlebutt is that he would fight Manny Pacquiao or, should he come out of retirement, Floyd Mayweather, in which case Terence would be fighting for the chance to be boxing's next great superstar. TopRank has already indicated they are looking to hand off the baton of King of Boxing to the right candidate and they are clearly grooming Terence to be that guy.

Anyone who knows Terence understands that he has been preparing for this nearly all his life. Nothing fazes him because he's come through a lot to get here and ever since getting shot in the head back in 2008 he's made boxing, outside of family, his singular focus. And now that he's already gotten this far there is no one and nothing that he will let stand in his way, not if he has anything to say or do about it.

In a way, he really doesn't have anything left to prove, other than showing that he truly belongs among the pantheon of contemporary and perhaps even all-time boxing greats. Only time will tell there. But it does appear he will get his opportunity to make his mark and knowing him he will take full advantage of it.

I have written before how Terence is in a long line of outstanding athletes to come out of North Omaha to do great things at high levels. In terms of boxers from here, he stands alone, with nobody really even close. Among all athletes from North O, I argue that he is the most accomplished in his sport since Bob Gibson dominated for the St. Louis Cardinals in the late 1960s-early 1970s. A case could be made for Gale Sayers as well. In terms of the most beloved, Bud's only close competition is Bob Boozer, Johnny Rodgers and Ahman Green, and maybe Maurtice Ivy.

It has been fascinating to see how in such a short period of time, ever since he won his first title as a lightweight in 2014 and subsequently defended that title twice in Omaha before huge crowds, he has won over such a large cross-section of folks. He has single-handedly resurrected the sport of boxing here and put this town on the national and international boxing map, thus giving this place one more thing to take pride in. And at 28 he may be the best known living Nebraskan now outside of Warren Buffett and Alexander Payne.

Omaha has gotten behind him and his passion for his hometown and for his North O community in a way that I don't think anyone could have predicted. It's very heartwarming to see, He already had a strong team around him in his Team Crawford crew of managers, coaches and trainers and now a whole team of advisers has come on board to help guide him and protect his earnings and to help him realize his vision for the B&B Boxing Academy. At Wednesday's meet-up down at the gym, there was an incredibly diverse mix of people present – B&B members, neighborhood residents, family, friends, movers and shakers and media, of course. Lots and lots of media.

The Omaha World-Herald has reported about Terence's heart for community and others and those are threads I've been writing about for some time. I have helped frame the B&B Boxing Academy story and I traveled with Terence and his close friend and former teacher, @[1619391711:2048:Jamie Fox Nollette] to Uganda and Rwanda, Africa to see first-hand his curiosity about and concern for people in need in the Motherland. I hope to follow more of his journey as time goes by.

Read my extensive reporting and writing about Terence at-

https://leoadambiga.com/tag/terence-crawford/

I will be covering his fight against Jean and so look for my impressions about that fight and many more things about Terence and his ever evolving story in future posts and articles.'](https://scontent-dfw1-1.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xap1/v/t1.0-0/s600x600/12039372_10200852100220058_326535901349247407_n.jpg?oh=f87b25e7d91756b4f2f87d1e4aa00c5d&oe=56D6E1C8)

!['EXCERPT FROM MY UPCOMING NEW STORY ABOUT TERENCE CRAWFORD

IN THE NEXT REVIVE OMAHA MAGAZINE

@[100001709629160:2048:Terence Crawford] cemented his status as King of Omaha Sports Figures by dispatching Dierry Jean in a WBO super lightweight bout on October 24 before 11,000 hometown fans at the CenturyLink Center arena.

Crawford, who's quickly become The People's Champ, imposed his will on the game but overmatched contender from Canada. He dropped Jean three times and had him in serious trouble again when awarded a 10th round technical knockout. The Omaha native carried the fight from the opening bell, using superior boxing skills and decisive height and reach advantages to repeatedly back Jean against the ropes and in the corners, landing nearly at will when pressing the action. The few times Dierry managed an attack, Crawford countered with combination barrages that left the challenger bloodied and bruised.

The end was never in doubt because Crawford was never in trouble. It was just a matter of when Derry would go or when the referee would stop the scheduled 12-rounder.

The event marked another coronation for Crawford, who's gone from a hungry kid just looking for a shot to a mature champion on the cusp of being one of his sport's highest paid big names. Along the way he's captured the hearts and minds of a city he's proud to call his own. From the moment this local hero entered the arena that night amidst entourage members holding aloft his two title belts, the fighter exuded the confidence and star quality associated with sports icons.

In the days before the fight Jean and his manager called out Crawford, vowing to take his lightweight belt to Canada. When Jean trash talked during the bout Crawford first let his fists do the talking before variously chirping back, stomping the canvas and smiling at the crowd as if to say, "I've got this" and "He's mine."

During the HBO interview just after the fight's conclusion Crawford taunted Jean and his manager in the ring with, "Did you get what you were looking for?" The crowd erupted in cheers. He also got a big response when he answered commentator Max Kellerman's question about the source of his fierce fighting nature with, "Where I'm from…" and gestured to friends and family who share the same neighborhood he does. He also expressed love for all the support Omaha gives him. The way he handled everything, from the crowd to the media to Jean, and still took care of business showed a professional athlete with real poise and presence. The more the spotlight shines on him, the more the boxing world discovers he's also a humanitarian with a deep commitment to his community.

At the post-fight press conference, where WBO head Bob Arum sat next to him and all but crowned him the fight organization's next superstar, Crawford was the calm, confident picture of Boxing's Next Big Thing. Crawford's already the toast of this town.

READ THE ENTIRE STORY IN THE NEXT REVIVE OMAHA and

LOOK FOR IT, TOO, ON MY FACEBOOK PAGE MY INSIDE STORIES AND ON MY BLOG, LEOADAMBIGA.COM'](https://scontent-dfw1-1.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xtf1/v/t1.0-0/s600x600/12196186_10200877284969661_1134190349754642721_n.jpg?oh=eb5af3b85f8b4377e31320ebef6eb726&oe=5719270E)

!['RANDOM INSPIRATION Got a call out of the blue yesterday afternoon from an 86-year-old man in Omaha. He's a retired Jewish American retailer. He'd just finished reading my November Reader cover story about The Education of a WASP and the segregation issues that plagued Omaha. He just wanted to share how much he enjoyed it and how he felt it needed to be seen by more people. [ 374 more words. ]

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/11/19/random-inspiration'](https://scontent-dfw1-1.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xla1/v/t1.0-0/p480x480/12241543_10200912545611155_3992960899687896090_n.jpg?oh=f67590bc9a3217ec2ebc57dbef468a66&oe=570CFB17)