Archive

Where Hope Lives, Hope Center for Kids in North Omaha

My blog features a number of stories that deal with good works by faith-based organizations, and this is another one. Northeast Omaha’s largely African-American community suffers disproportionately in terms of poverty, low educational achievement, underemployment and unemployment, health problems, crime, et cetera. These challenges and disparities by no means characterize the entire community there, but the distress affects many and is persistent across generations in many households. All manner of social services operate in that community trying to address the issues, and the subject of the following story, Hope Center for Kids, is among those. I filed the story for Metro Magazine (www.spiritofomaha.com) and I came away impressed that the people behind this effort are genuinely knowledgable about the needs there and are committed to doing what they can to reach out to youth in the neighborhoods surrounding the center.

Where Hope Lives, Hope Center for Kids in North Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in Metro Magazine (www.spiritofomaha.com)

Northeast Omaha’s largely poor, African-American community is a mosaic where despair coexists with hope. A stretch of North 20th Street is an example. Rows of nice, newly built homes line both sides of the one-way road — from Binney to Grace Streets. Working class families with upwardly mobile aspirations live there.

Yet, vacant lots and homes in disrepair are within view. God-fearing working stiffs may live next door to gang bangers. To be sure, the good citizens far outnumber the thugs but a few bad apples can spoil things for the rest.

Endemic inner city problems of poverty, teen pregnancy, drug abuse, gun violence, unemployment, school dropouts and broken homes put a drag on the district. Church, school and social service institutions do what they can to stabilize an unstable area. Meanwhile, the booming downtown cityscape to the south offers a vista of larger, brighter possibilities.

One anchor addressing the needs is the faith-based nonprofit Hope Center for Kids. Housed in the former Gene Eppley Boys Club at 2209 Binney, the center just celebrated its 10th anniversary. An $800,000 renovation replaced the roof and filled in the pool to create more programming space. Four years ago the organization opened Hope Skate, an attached multi-use roller rink/gymnasium that gives a community short on recreational amenities a fun, safe haven.

In the last year Hope’s received grants from the Kellogg Foundation, the Millard Foundation and Mutual of Omaha to expand its life skills and educational support services. Additional staff and more structured programs have “taken us to a whole new level,” said founder/executive director Rev. Ty Schenzel.

Clearly, the 50,000 square foot, $1.2 million-budgeted center is there for the long haul. Hope serves 400 members, ages 7 to 19. Most come from single parent homes. Eight in 10 qualify for free or reduced price lunch at school. Hope collaborates with such community partners as nearby Conestoga Magnet Center and Jesuit Middle Schools, whose ranks include Hope members. University of Nebraska at Omaha students are engaged in a service learning project to build an employability curriculum. Creighton med students conduct health screenings. Volunteers tutor and mentor. Bible studies and worship services are available.

Some Hope members work paid part-time jobs at the center. Members who keep up their grades earn points they can spend at an on-site store.

Per its name, Hope tries raising expectations amid limited horizons. It all began a decade ago when two Omaha businessmen bought the abandoned boys club and handed it over to Schenzel, a white Fremont, Neb. native and suburbanite called to do urban ministry. He was then-youth pastor at Trinity Interdenominational Church., a major supporter of Hope.

He first came down to The Hood doing outreach for Trinity in the mid-’90s. He and volunteers held vacation bible studies and other activities for children at an infamous apartment complex, Strehlow, nicknamed New Jack City for all its crime. He met gang members. One by the street name of Rock asked what would happen to the kids once the do-gooders left. That convinced Pastor Ty, as Schenzel’s called, to have a permanent presence there. In a sea of hopelessness he and his workers try to stem the tide.

“What we believe is at the root of the shootings, the gang activity, the 15-year-old moms, the generation after generation economic and educational despair is hopelessness,” he said. “If you don’t think anything is going to change and you don’t care about the consequences then you lose all motivation. You have nothing to lose because you’ve lost everything.

“Our vision is we want to bring tangible hope with the belief that when the kids experience hope they’ll be motivated to make right choices. They’ll start to believe.”

Schenzel said what “differentiates Hope is that the at-risk kids that come to us probably wouldn’t fit in other programs. The faith component makes us different. The economic development-jobs creation aspect. The roller rink.”

He said former Hope member Jimmie Ventry is a measure of the challenge kids present. Older brother Robert Ventry went on a drug-filled rampage that ended in him being shot and killed. Jimmie, who’s been in and out of trouble with the law, had a run in with cops and ended up doing jail time. Schenzel said, “One day I asked Jimmie, ‘How do I reach you? What do I do to break through?’ And the spirit of what Jimmie said was, Don’t give up on me. Don’t stop trying.” Hope hasn’t.

Schenzel said results take time. “I tell people we’re running a marathon, not a sprint, which I think is what Jimmie was saying. We’re now in our 10th year and in many ways it feels like we’re still starting.” Hope Youth Development Director Pastor Edward King said kids can only be pointed in the right direction. Where they go is their own decision.

“It’s one thing when they come here and we’re throwing them the love and it’s another thing when they go back to their environment and the drug dealers are telling them not to go to work,” he said. “We’re here telling them: You do have options; you can make honest money without the guilt and having to look over your shoulder; you don’t have to go to prison, you can graduate from school — you can go to college.

“We provide hope but the battle is theirs really. When you don’t believe you can, when everything around you is hopelessness, it takes a strong person to want to make the right choices.”

Chris Morris was given up as a lost cause by the public schools system. Hope rallied behind him. It meant long hours of counseling, prodding, praying. The efforts paid off when he graduated high school.

“The Hope Center helped me in a positive way. Just having them around gave me hope,” said Morris.

King said several kids who’ve thought of dropping out or been tagged as failures have gone on to get their diploma with the help of Hope’s intervention.

“It took a lot of hard work for people to stay on them and to push them through,” said King. “We’re so proud of them.”

The kids that make it invariably invite Hope teachers and administrators to attend their graduation. That’s affirmation enough for King. “It’s the thing that keeps me coming back,” he said. “When I hear a guy talk about how coming here keeps him out of trouble or makes him feel safe or that he enjoys hanging out with my family at our house, that lets me know we’re doing the right thing.”

For many kids the first time they see a traditional nuclear family is at a Hope staffer’s home. It’s a revelation. Staff become like Big Brothers-Big Sisters or surrogate parents. They go out of their way to provide support.

“Our staff go to kids’ games, they connect with them on the weekend, they’re involved in the lives of the kids. Pastor King’s house should probably be reclassified a dormitory,” Schenzel said.

King comes from the very hard streets he ministers to now. Like many of these kids he grew up fatherless. He relates to the anger and chaos they feel.

“It breaks my heart to see the killings going on. I couldn’t sit back on the sidelines and not do anything. I feel like it’s my responsibility to be here. I know what it’s like to have resentment for not having a dad around. A lot of the young men don’t have a positive male role model at home to be there for them, to discipline them.”

Hope educators work a lot on discipline with kids. Positive behavior is emphasized –from accepting criticism to following instructions. Hope slogans are printed on banners and posters throughout the center.

There, kids can channel their energies in art, education, recreation activities that, at least temporarily, remove them from bad influences. A Kids Cafe serves hot meals. King supervises Hope’s sports programs. “If we can get them involved in our rec leagues, then it’s less time they can be doing the negative things,” he said. “There’s nothing like the discipline of sports to keep a guy in line. We get a chance to teach life skills to the guys. “

Ken and Rachelle Johnson coordinate Hope’s early ed programs. An expression of the couple’s commitment is the home they bought and live in across the street.

“For me personally it’s not a job, it’s a ministry it’s a lifestyle, it’s our life.” Rachelle said. “We love being around the kids in the neighborhood. The kids deal with a lot of abandonment-neglect issues. They all have their own story. We wanted to say, Here, we’re committed, we’re not going anywhere, because it takes a long time to build relationships.”

Relationship building is key for Hope. Staff work with families and schools to try and keep kids on track academically. Programs help kids identify their strengths and dreams. To encourage big dreams teens meeting certain goals go on college tours.

“Increasingly we want to create this culture of connecting our kids to higher education,” Schenzel said.

Optional worship services are offered but all members get exposed to faith lessons through interactions with staff, who model and communicate scripture.

“Here’s our mantra,” Schenzel said: “You can only educate and recreate so long but unless there’s a heart change through a relationship with the Lord it’s putting a Band Aid on wet skin.”

Hope strives to have about 100 kids in the building at any given time. “Much more than that feels a little bit like a daycare. We don’t want to be a daycare. We want to do some transformation,” he said.

Schenzel sees “little buds of tangible hope going on” in what he terms Omaha’s Ninth Ward. He and residents wonder why “there’s seemingly an unholy bubble over north Omaha” preventing it from “getting in on the growth” happening downtown and midtown.” Those frustrations don’t stop him from dreaming.

“We would love to do mini-Hope satellites in the community, maybe in collaboration with churches, as well as Hope Centers in other cities. We envision an internship program for college students who want something to give their hearts to. We could then exponentially impact more kids. We want to create cottage industries that generate jobs and revenue streams. Some day we want to do Hope High School.”

Keep hope alive, Pastor Ty, keep hope alive.

Related articles

- Community and Coffee at Omaha’s Perk Avenue Cafe (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha’s St. Peter Catholic Church Revival Based on Restoring the Sacred (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Hey, You, Get Off of My Cloud! Doug Paterson – Acolyte of Theatre of the Oppressed Founder Augusto Boal and Advocate of Art as Social Action (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Theater as Insurrection, Social Commentary and Corporate Training Tool (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- An Omaha Legacy Ends, Wesley House Shutters after 139 Years – New Use for Site Unknown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Joy of Giving Sets Omaha’s Child Saving Institute on Solid Ground for the Future (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Coming to America: The Immigrant-Refugee Mosaic Unfolds in New Ways and in Old Ways In Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Overarching Plan for North Omaha Development Now in Place, Disinvested Community Hopeful Long Promised Change Follows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Soon Come: Neville Murray’s Passion for the Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its Role in Rebirthing North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Decent House for Everyone, Jesuit Brother Mike Wilmot Builds Affordable Homes for the Working Poor Through Gesu Housing (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Lifetime Friends, Native Sons, Entrepreneurs Michael Green and Dick Davis Lead Efforts to Revive North Omaha and to Empower its Black Citizenry (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- After a Steep Decline, the Wesley House Rises Under Paul Bryant to Become a Youth Academy of Excellence in the Inner City (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Synergy in North Omaha Harkens a New Arts-Culture District for the City (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Outward Bound Omaha Uses Experiential Education to Challenge and Inspire Youth (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

An Omaha legacy ends, Wesley House Community Center shutters after 139 years — New use for site unknown

Omaha Legacy Ends, Wesley House Community Center shutters after 139 years – New use for site unknown

©by Leo Adam Biga

As seen in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Omaha’s oldest social service agency closed earlier this year with a whimper, not a bang. The Wesley House Community Center, a United Methodist Church mission since 1872, has ended 139 years of service, confirmed Rev. Stephanie Ahlschwede, interim executive director and head of United Methodist Ministries in Omaha.

The agency’s two-acre, twin-building campus at 2001 North 35th St. will be sold, she says. And it’s unclear who will purchase it.

Wesley served the African-American community for the last half century. At its peak, it offered youth and adult programs and spun off a black-run radio station, a community bank, a credit union and a pair of economic development organizations.

But Wesley lost traction in the 1990s. Later, when management came under fire, primary funding support was pulled. By the early 2000s, Wesley barely hung on as a youth center. In 2005, Paul Bryant came on as executive director to shore up the nonprofit’s reputation and finances. He largely succeeded through the youth leadership academy he launched.

In October, Bryant tendered his resignation with the understanding Wesley would continue.

“Last year was our absolute best year at the Wesley House. Things were hitting on all cylinders,” he says, adding that the agency’s annual fundraising dinner and golf tournament were successful.

Paul Bryant

However, financial pressures remained. He says the academy struggled competing with larger, better-funded programs with more facilities. It scrambled just to meet operating costs. Besides, he says, “it was time to go, my work there was done. I felt a calling to take this work and expand it outside the walls of Wesley House into the schools.” He’s doing that under his Purpose Leading brand.

Bryant says he offered to remain through 2010 to assist the transition once a new executive director was hired. On Nov. 12, Ahlschwede was appointed. Bryant says he was then asked to clear out and disband the academy by Nov. 19.

Ahlschwede says she and the board intended to keep the center open, but closer examination revealed it wasn’t financially sustainable.

“The type of program Paul envisioned was much more difficult to fund than we realized,” she says. “You’ve got program costs to have things be adequately staffed and nurtured and tended, but you also have overhead, and the property itself comes with a significant amount of overhead because they’re big, old buildings.”

She says the board considered converting the site into an urban farm and food-justice campus, “until we realized the significance of the financial shortfall.”

Rev. Stephanie Ahlschwede

With Bryant — the center’s chief programmer and fundraiser — leaving to form his own nonprofit, the board soon decided to close the agency.

“They probably got a first-hand look at what it took to keep that thing afloat — I raised close to $2.5 million in the time I was there,” Bryant says.

Ahlschwede says she and the board concluded it was time to break the decades-old cycle of underfunding and revolving programs.

“We’ve been on a roller coaster here and at some point you can’t ignore it anymore,” she says.

She’s aware a legacy’s come to an end.

“It’s hard to end things and to say no to things,” she says. “When you talk to United Methodists who’ve been around about Wesley House, everyone sighs and is really sad because there’s been all these dreams and a long, rich history with many visionary and charismatic leaders, including Paul.

“It was very difficult. the board really struggled, because the dream and the reality weren’t matching up, and that is heartbreaking.”

Bryant learned of Wesley’s demise from The Reader.

“This is quite shocking to me it’s closed and it’s going to be sold,” he says. “It was so much more than a gym and swim program. In Omaha, at one time, it was the point agency for change.”

While the center received donations from Methodist congregations, even in outstate Nebraska, he says, “It really didn’t feel like we had the whole weight and support of the United Methodist Church behind it.”

Omaha Economic Development Corporation president Michael Maroney shares a heavy heart over the news of Wesley’s closing.

“It had meant so much over the years, particularly in the ’60s and ’70s, when it actually was doing unprecedented things,” says Maroney, who worked there on three occasions.

In a twist of fate, OEDC, which began at Wesley, is weighing a purchase agreement for the site. If OEDC decides to buy, Maroney says, “we would do the best we could to ensure it continues to add value to the community going forward, and no one knows exactly what that means. But we didn’t want to see an abandoned property or an inappropriate use. We wanted to make sure that whatever goes in there is hopefully embraced and supported by the community.”

Bryant and Ahlschwede express confidence in Maroney’s stewardship should OEDC proceed. The OEDC board is expected to decide before June.

Related articles

- Who do we serve? (johnmeunier.wordpress.com)

- Campaign Seeks to Take a ‘Bite’ Out of Disease (nytimes.com)

- Once More With Feeling, Loves Jazz & Arts Center Back from Hiatus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- All Trussed Up with Somewhere to Go, Metropolitan Community College’s Institute for Culinary Arts Takes Another Leap Forward with its New Building on the Fort Omaha Campus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Change is Gonna Come, the GBT Academy in Omaha Undergoes Revival in the Wake of Fire (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Rev. Everett Reynolds Gave Voice to the Voiceless (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Family Thing, Bryant-Fisher Family Reunion (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Overarching Plan for North Omaha Development Now in Place, Disinvested Community Hopeful Long Promised Change Follows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- North Omaha Champion Frank Brown Fights the Good Fight (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Soul on Ice – Man on Fire: The Charles Bryant Story (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness) (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Once More With Feeling: Loves Jazz & Arts Center back from hiatus

Once More With Feeling, Loves Jazz & Arts Center back from hiatus

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Rumors about the impending demise of a north Omaha cultural institution began flying last fall when Loves Jazz & Arts Center, 2510 N. 24th St., took an extended break from normal operations.

Even the hint of trouble alarmed the African American community and city-county officials, who view LJAC as a linchpin for an envisioned 24th and Lake revival. The North Omaha Development Project, the Empowerment Network and others target the area as a potential cultural-tourism district.

The reports, while dead wrong, were not unreasonable given that during a nine-month hiatus LJAC made no announcement concerning why it ceased exhibitions and programs. Or why it was open only by appointment and for rental. It turns out the inactivity was not due to financial crisis as some feared; rather, the staff and board undertook a funder-prompted and strategic planning and building process.

LJAC also underwent an audit, which board chair Ernest White says “came out clean.” The result of it all, White said, is a restructured and refocused organization whose makeover is in progress. For the first time in months LJAC is regularly open to the public, presenting gallery displays and live music events.

White could have quelled negative speculation by offering an explanation through traditional or social media. The American National Bank vice president chose silence, he says, to distance LJAC from the rumor mill that dogged the nearby Great Plains Black History Museum.

While questions went unanswered about its dormancy, LJAC participated with other nonprofits in the Omaha Community Foundation’s capacity-building initiative. White says the monthly sessions, led by OCF consultant Pete Tulipana, critically examined staffing, administration, memberships and programs.

White says no funding was withheld as a stick for LJAC to undergo the review, though some funds are “pending” its compliance with recommended changes. (The LJAC would not identify any specifics in terms of pending funds.)

Understaffed and under-funded since its 2005 opening, LJAC hurt itself, White says, by doing a poor job marketing, not signing up members, keeping inconsistent hours and, on at least two occasions, losing approved grant money by failing to file required paperwork.

“There were some things not done, there were some inefficiencies,” he says. “We need to do a better job, we need to be open when we say we’re going to be open, we need to be accessible, and those are things I think we’re already a long ways to fixing.”

Despite “great” exhibits and programs, White says few people knew of them.

The review process, he says, is “brutally honest — here’s your strengths, here’s your weaknesses. They make you do a 10-year plan. They challenge you.” The need for a seasoned administrator led White to ask Neville Murray, executive director since LJAC’s inception, to relinquish that role and remain as curator. When Murray declined, White appointed Omaha entrepreneur Tim Clark as interim executive director.

“This place needs money,” says Clark, “and every single board member has to step up and do their part. You can’t ask anybody else to help you if your board is not helping.”

The LJAC board continues to be in flux.

Efforts going forward, says Clark, revolve around “trying to retool, build the infrastructure for capacity, for sustainability long term.” He says, “The strategy now will be more looking at how do we build partnerships with school systems, getting more youth involved. We’ve brought on Janet Ashley as program director to help look at our Loves Art School and partnering with targeted elementary schools this summer.”

White says funders want the center to do more educational programming and stay on mission as an art gallery that celebrates black culture and jazz music.

“When people give us money,” says Clark, “we’ve got to give them a return on their investment. They can hold us accountable — we’ve just got to live up to expectations.”

He says LJAC’s securing sponsors and strategic partners to help it realize its potential as a public attraction.

“I think we have a product and a story to tell. We just have to be better at telling that story. We have to be more proactive. I think we’re positioned now to move forward. I’m excited about its future possibilities. I think if we’re successful it stimulates everything around us.

“Have we made some mistakes? Yes, we have. We have some challenges before us. It’s not going to be a cakewalk, but we’re going to roll up our sleeves and tackle them.”

Acknowledging the center’s transitional mode, Clark says, “We’re open for business, but we’re not making a big splash of that until we know we can sustain that. We want to do the work within first. We want to be whole.”

“We want to be viable,” adds White.

LJAC’s new Jazz Fridays series launches May 6, from 5 to 8 p.m., with For the Occasion. Two new exhibits are in the works. For more information, call 402-502-5291.

Related articles

- Frederick Brown’s Journey Through Art is a Passage Across Form and a Passing On of Legacy (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Adventurer/Collector Kam-Ching Leung’s Indonesian Art Reveals Spirits of the Islands (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Lit Fest Brings Author Carleen Brice Back Home Flush with the Success of Her First Novel, ‘Orange Mint and Honey’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Rich Music History Long Untold is Revealed and Celebrated at the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omowale Akintunde’s In-Your-Face Race Film for the New Millennium, ‘Wigger,’ Introduces America to a New Cinema Voice (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Tired of Being Tired Leads to a New Start at the John Beasley Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Vincent Alston’s Indie Film Debut, ‘For Love of Amy,’ is Black and White and Love All Over (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Art as Revolution: Brigitte McQueen’s Union for Contemporary Art Reimagines What’s Possible in North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Omaha native Steve Marantz looks back at city’s ’68 racial divide through prism of hoops in new book, “The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central”

Omaha native Steve Marantz looks back at city’s ’68 racial divide through prism of hoops in new book, “The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

America’s social fabric came asunder in 1968. Vietnam. Civil rights. Rock ‘n’ roll. Free love. Illegal drugs. Black power. Campus protests. Urban riots.

Omaha was a pressure cooker of racial tension. African-Americans demanded redress from poverty, discrimination, segregation, police misconduct.

Then, like now, Central High School was a cultural bridge by virtue of its downtown location — within a couple miles radius of ethnic enclaves: the Near Northside (black), Bagel (Jewish), Little Italy, Little Bohemia. A diverse student population has enriched the school’s high academic offerings.

Steve Marantz was a 16-year-old Central sophomore that pivotal year when a confluence of social-cultural-racial-political streams converged and a flood of emotions spilled out, forever changing those involved.

Marantz became a reporter for Kansas City and Boston papers. Busy with life and career, the ’68 events receded into memory. Then on a golf outing with classmates the conversation turned to that watershed and he knew he had to write about it.

“It just became so obvious there’s a story there and it needs to be told,” he says.

The result is his new book The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central: High School Basketball and the ’68 Racial Divide (University of Nebraska Press).

Speaking by phone from his home near Boston, Marantz says, “It appealed to me because of the elements in it that I think make for a good story — it had a compact time frame, there was a climatic event, and it had strong characters.” Besides, he says sports is a prime “vehicle for examining social issues.”

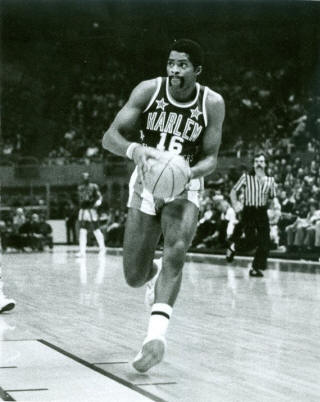

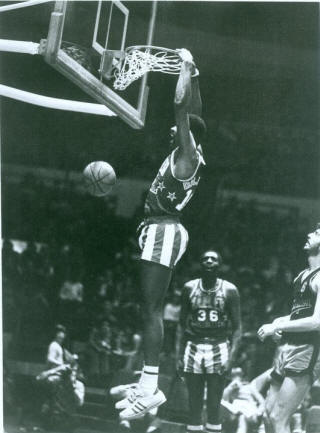

Conflict, baby. Caught up in the maelstrom was the fabulous ’68 Central basketball team, whose all-black starting five earned the sobriquet, The Rhythm Boys. Their enigmatic star, Dwaine Dillard, was a 6-7 big-time college hoops recruit. As if the stress of such expectations wasn’t enough, he lived on the edge.

At a time when it was taboo, he and some fellow blacks dated white girls at the school. Vikki Dollis was involved with Dillard’s teammate, Willie Frazier. In his book Marantz includes excerpts from a diary she kept. Marantz says her “genuine,” “honest,” angst-filled entries “opened a very personal window” that “changed the whole perspective” of events for him. “I just knew the vague outlines of it. The details didn’t really begin to emerge until I did the reporting.”

Functionally illiterate, Dillard barely got by in class. A product of a broken home, he had little adult supervision. Running the streets. he was an enigma easily swayed.

Things came to a head when the polarizing Alabama segregationist George Wallace came to speak at Omaha’s Civic Auditorium. Disturbances broke out, with fires set and windows broken along the Deuce Four (North 24th Street.) A young man caught looting was shot and killed by police.

Dillard became a lightning rod symbol for discontent when he was among a group of young men arrested for possession of rocks and incendiary materials. This was only days before the state tournament. Though quickly released and the charges dropped, he was branded a malcontent and worse.

White-black relations at Central grew strained, erupting into fights. Black students staged protests. Marantz says then-emerging community leader Ernie Chambers made his “loud…powerful…influential” voice heard.

The school’s aristocratic principal, J. Arthur Nelson, was befuddled by the generation gap that rejected authority. “I think change overtook him,” says Marantz. “He was of an earlier era, his moment had come and gone.”

Dillard was among the troublemakers and his coach, Warren Marquiss, suspended him for the first round tourney game. Security was extra tight in Lincoln, where predominantly black Omaha teams often got the shaft from white officials. In Marantz’s view the basketball court became a microcosm of what went on outside athletics, where “negative stereotypes” prevailed.

Central advanced to the semis without Dillard. With him back in the lineup the Eagles made it to the finals but lost to Lincoln Northeast. Another bitter disappointment. There was no violence, however.

The star-crossed Dillard went to play ball at Eastern Michigan but dropped out. He later made the Harlem Globetrotters and, briefly, the ABA. Marantz interviewed Dillard three weeks before his death. “I didn’t know he was that sick,” he says.

Marantz says he’s satisfied the book’s “touched a chord” with classmates by examining “one of those coming of age moments” that mark, even scar, lives.

An independent consultant for ESPN’s E: 60, he’s rhe author of the 2008 book Sorcery at Caesars about Sugar Ray Leonard‘s upset win over Marvin Hagler and is working on new a book about Fenway High School.

Marantz was recently back in Omaha to catch up with old Central classmates and to sign copies of Rhythm Boys at The Bookworm.

|

|

|

Related articles

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Big Bad Buddy Miles (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omowale Akintunde’s In-Your-Face Race Film for the New Millennium, ‘Wigger,’ Introduces America to a New Cinema Voice (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Great Plains Black History Museum Asks for Public Input on its Latest Evolution

This February 2011 story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) is my latest about the Great Plains Black History Museum in Omaha. Referenced in the article are some of the many travails that have dogged this organization. You can find out more about the challenges the museum has faced in three earlier stories posted on this blog. For the longest time the only news coming out of the museum was bad news. But as my new piece suggests there are some positive things happening now having to do with new leadership in place that might finally provide the direction needed to move forward with long overdue change and much delayed progress. I will continue following this story and as new developments occur and as I report on them I will share the posts here.

Great Plains Black History Museum Asks for Public Input on its Latest Evolution

©by Leo Adam Biga

Published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The new Great Plains Black History Museum board is putting its stamp on the long troubled organization by holding the first in a planned series of community forums about its future direction.

On February 11, GPBHM chairman Jim Beatty will lead a 2-4 p.m. forum at the Lakeside (Family Housing Services Advisory) building, 24th and Lake, to, as a flyer describes, “discuss a variety of topics…on your mind.”

Beatty, president of Omaha-based consulting firm NCS International, is aware attempts to move forward necessarily entail addressing the dysfunction of the museum’s recent past. The City of Omaha has declared the museum building at 2213 Lake Street uninhabitable, resulting in the doors being closed. The mandated repairs have not been made due to lack of funds.

When he assumed his roles as board chair and museum executive director last fall he found the coffers virtually empty, with no members and no donors. The museum’s not been awarded a grant in years.

“There isn’t a lot of money there,” he says. “I think something like $29 in the checking account.”

Previous chair and director Jim Calloway tried maintaining the building and collection by paying for utility bills, spot roof-window fixes and storage sites out of his own pocket.

Calloway, the son of founder Bertha Calloway, was criticized for his management of funds and for storing the museum’s historical research materials in a non-climate controlled trailer.

“That by no means meets my criteria or any museum’s criteria for proper storage of documents and artifacts,” says Beatty. “That may have been done in the past out of some level of desperation, another indication the leadership of the museum was not operating with the best intentions of handling its business properly.”

Yet, Beatty praises Calloway’s passion. “I think the public needs to understand Jim was trying to keep his mother’s dream alive,” he says, “and that’s not to be taken lightly.” He also credits Calloway for reaching an agreement with the Nebraska State Historical Society to take temporary custodial care of the materials. The documents and photographs are housed at the NSHS in Lincoln, where cataloging’s been done.

Beatty says the materials will remain there until a suitable home is found. While the GPBHM seeks support to address issues at its Lake Street building and the possible addition of a new site, it seeks to make itself and the collection visible.

“The museum has a very valuable collection the public has not seen that it needs to see or at least needs to understand what does exist,” he says. “We have a challenge to save the building but we have to make certain people understand the building does not dictate the museum. The museum is a compilation of resources, artifacts, documents, and that work needs to go on. Once we have properly inventoried everything, then we can begin to identify opportunities to properly display that.”

He’s thinking outside the box.

“The museum can and will have to function without having that building as its base. We can have exhibits at schools, at corporations, at Crossroads, Westroads, at various events.”

He envisions a revamped, interactive website featuring the collection online.

“So, for a time it may well be a museum without walls, and that’s OK. I am in discussions with an entity to provide a facility. Until we get a space, I think we have to be creative — we have to truly demonstrate the museum is alive and well.”

He acknowledges the GPBHM has not communicated its story well. “It’s unfortunate the community just has not known what the museum is doing. I believe there’s a number of rumors out there that need to be corrected.” One he wants to dispel is that the Lake Street building is owned by the Calloways.

“A lawsuit ultimately decided in favor of the museum gave title to the building to the museum as opposed to the family,” he says.

He vows greater transparency.

“People want to know what the bottom-line is. They want to have an assurance the money is being used wisely, accounted for properly and in a timely fashion, and that the books are open. Folks want to know, and in my opinion they deserve to know.”

A capital campaign will eventually be launched.

“Omaha’s a very philanthropic community. I believe we’ll be able to raise money. I’m very confident in that. How much depends on how the funders view the credibility of the organization. That starts with the board of directors,” he says. “We have to have people that bring resources and credibility.”

Toward that end two stalwart Omaha business-community figures — Frank Hayes and Ken Lyons — recently joined the board.

“We need the involvement of the government too,” he says. “The city, county and state all are potential funders at some level.”

More than anything, he wants the museum lifted out of its dormancy.

“There is a sadness this is happened but at the same time there is a hope something can be done to revive the museum and put it on a proper track. My discussions in the community confirm people want to see a vibrant museum that is relevant, involved, proactive, well managed, respected.”

Beatty, who chaired the Durham Museum board, says, “It’s certainly a challenge but one I feel my previous involvement in the community has prepared me well for. I’m unafraid of it, I welcome it.”

Related Articles

- Long and Winding Saga of the Great Plains Black History Museum Takes a New Turn (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Arts-Culture Scene All Grown Up and Looking Fabulous (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Once More With Feeling, Loves Jazz & Arts Center Back from Hiatus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- El Museo Latino in Omaha Opened as the First Latino Art and History Museum and Cultural Center in the Midwest (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Negro Leagues Baseball Museum Exhibits on Display for the College World Series; In Bringing the Shows to Omaha the Great Plains Black History Museum Announces it’s Back (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Synergy in North Omaha Harkens a New Arts-Culture District for the City (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Academy Award-nominated documentary “A Time for Burning” captured church and community struggle with racism

Rarely has a film, fiction or nonfiction, captured a moment in time as tellingly as did A Time for Burning, the acclaimed 1967 documentary that exposed racism in Omaha, Neb. through the prism of a church and a community’s struggle with issues of integration at a juncture when the nation as a whole struggled with the race issue. The film really is a microcosm for the attitudes that made racial dialogue such a painful experience then. In truth, when it comes to race not as much has changed as we would like to think. It is still America’s great open wound and it will likely remain so for the foreseeable future. The following two articles appeared, as Part I and Part II, of a two-part series exploring the context for the film and the impact it had here and nationwide. The stories appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com) around the time of the film’s 40th anniversary. If you’ve never seen the documentary, then by all means seek out a DVD copy or a screening. It’s a powerful piece of work that will provoke much thought and discussion. In fact, from the time the film was first released to this very day it is used by educators and activists and others as an authentic glimpse at what lies beneath the racial divide.

“A Time for Burning”

Part I

Academy Award-nominated documentary captured church and community struggle with racism

What Would Jesus Do Today?

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

On the eve of the 1968 Oscars, a nominee for best documentary feature, filmed in Omaha, foretold the violence that was ripping America apart. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination six days earlier in Memphis was the match that lit the fire. The riots that followed spread to more than 100 cities.

About once every generation a seminal film takes an unblinking look at race in America. Crash took the incendiary subject head-on in the 2000s. Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing hit all the hot buttons in the 80s. Roots offered a hard history lesson in the 70s. A Time for Burning arguably made the most righteous contribution to the topic in the 60s.

The movie took a heavy toll locally, splitting Omaha’s largest and most established Lutheran congregation on the year of its 100th anniversary.

Produced at the height of the civil rights movement, Burning captures honest, in-the-moment exchanges about race. Shot here in 1965 and released in late ‘66, Burning’s candid, unadorned style was revolutionary then and remains cutting-edge today.

Turned down by the three major networks, it premiered on PBS to national acclaim. Burning earned an Oscar nomination and became a staple of school social studies curricula and workplace diversity programs. Selected for the National Film Registry in 2005 to be preserved by the Library of Congress, the picture may be viewed in a new DVD release.

Burning holds special significance for Omaha. The film that was a litmus test for racism then and is a prism for measuring progress today. Then the mood was rapidly turning acidic. The black frustration expressed in the film first erupted in violent protest mere months after production wrapped. The race riots of the late 60s tore apart the North Omaha community as the promise of a better future was dashed against new injustices piled on a century of oppression.

The film came at a crossroads moment in Omaha history. At a time when racism was on the table for discussion, the opportunity to address it was lost.

Burning follows self-described “liberal Lutheran” pastor Rev. Bill Youngdahl, on a quest for his all-white congregation at Augustana Lutheran Church to do some fellowship with black Christians living “less than three blocks away.” The son of a popular former Minnesota governor, Youngdahl had recently come from a Lutheran Church of America post in New York, where he led the national church body’s social justice ministry. He marched with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Washington, D.C. He traveled the country working for the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act.

All of which led director Bill Jersey and producer Bob Lee to seek him out when he came to minister in that most typical American city — Omaha.

His “inclusive ministry” posed problems from the start of his arrival at Augustana. Church elders earlier made it clear he should steer clear of the homes of black families when evangelizing in the neighborhood. “I said, ‘I can’t do that. I won’t do that.’” The film project brought everything to a head.

“After filming began, some people began to question what was being documented. ‘Why aren’t they filming the smorgasbord and the choir?’ So, that became an issue,” Youngdahl said. “I had to call those two (Jersey and Lee) back from New York to appear before the council. We talked several hours and finally affirmed going ahead with the film as Bill wanted to do it.”

Members of the church council try to get this brash upstart to tone down calls for diversity. Caught in the fray is member Ray Christensen, who goes from the timid ranks of “we’re moving too fast” to vocal advocate of outreach.

Militant sage Ernie Chambers, pre-state senator days, dissects it all. Chambers held court then in Dan Goodwin’s Spencer Street Barbershop, where he cut heads and blew minds with his razor sharp activist ideology. A famous scene finds Chambers lecturing Youngdahl, who’s come to the shop to float his idea for interracial fellowship. The pastor sweats as Chambers, wary of this do-gooder’s intentions, critically analyzes him and foretells his fate.

As the film plays out, the black Christians stand ready to break bread and talk straight with whites, most of whom repeat the mantra “the time is not right.” Youngdahl asks his bishop, “If not now, when?”

Cinema Verite

Unseen but felt throughout is the guiding hand of Jersey — one of America’ most noted and honored documentarians. His projects range from the Renaissance to the Jim Crow era to a recent film on propaganda in modern society. He applied cinema verite techniques with his hand-held camera and available lighting. The approach registers an intimate naturalism. Point-of-view narration and jump cuts heighten the conflict. He was assisted on the shoot by the late Barbara Connell, who also cut the film.

“Nobody in that film appears because a filmmaker dragged them in,” said Jersey. “Everyone appears because they were in some way directly involved with what was going on in that community. I feel that is, in fact, its strength — it’s a story of individuals who faced one another and confronted one another. No one was ever set up to expose their prejudice.”

Jersey admits he influenced situations to further the story, suggesting a couples exchange to Youngdahl, sensing it would stir up trouble.

The climax comes when Youngdahl proposes the exchange with ten volunteer couples from Augustana meeting with ten couples at nearby black churches Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church and Hope Lutheran Church. The mere idea of meeting for fellowship in each others’ homes polarized the Augustana congregation. The adult visits never come off, but a youth exchange does, setting off a firestorm.

Former Calvin member Wilda Stephenson helped escort the youths to Augustana. The retired Omaha educator recalled “the people in the congregation became very upset that they were there and participating, especially in their communion service. That bothered me. I wouldn’t have gone if I had thought we weren’t going to be received well that Sunday.”

The visit followed a warmly received visit by white Augustana youths to Calvin.

“We were really glad to see that happen and welcomed them,” Stephenson said. “And that was the situation whenever any white people attended our church. We just always made them feel welcome. For our youths to have been treated otherwise, I was really shocked about that.”

The Calvin youths who went to Augustana that Sunday included Central High students Johnice (Pierce) Orduna and Francine Redick. Orduna said they were not made to feel “unwelcome” by anything overtly said or done. Such is the “insidious face of racism.” They only learned of the upset their visit caused when Jersey, who always stirred the pot, told them what his cameras and mikes caught. He gathered the students for an on-camera forum in which they pour out their disappointment.

“There was a fair amount of anger, certainly some frustration, but I would say outrage and real surprise that Christians we thought had similar ideas about humanity and how to live lives would behave that way,” Redick said. “The visit seemed like such a small thing. I mean, it’s not like we wanted to marry their children. It was people worshiping together. At one point in the film I utter something like, ‘How can people who profess to be Christians and Christian ministers respond in this way?’ Even today that seems outrageous to me.”

“I’m sure whatever Bill preached was not that radical,” then-Calvin pastor Rev. James Hargleroad said. “The whole gist of the film is how such a minor thing could lead to such a momentous result when racism is rampant in a community. The civil rights movement was well under way then, but it was a little late getting to Omaha.”

Burning documents the fallout, including rounds of frank discussion that expose people’s naked fears and prompt serious soul searching, as the divisive climate increasingly makes Youngdahl’s position untenable.

Commissioned by Lutheran Film Associates to show a positive portrayal of the church engaged in racial ministry, Jersey made a film tacitly critical of its efforts.

“It didn’t spark conflict, it sparked dialogue,” Jersey said. “We didn’t do a film about Omaha. We didn’t really even do a film about a church. We did a film about individuals in a church structure struggling with the issue of race in a way that I think represented how America was dealing with race at the time,” he said. “Not the crazies in the South who were using fire hoses and attack dogs. Not the urbanites who were frustrated for many other reasons and setting fires to the banks. But average people being who they are authentically.

What Would Jesus Do Today?

The figure who most poignantly grapples onscreen with his own views is Christensen. His crisis of conscience marks some of Burning’s most human moments. At one point, he said, he wanted to quit the project. Everything was topsy-turvy. The placid church that once comforted him had turned battleground. Jersey convinced him the film was too important for him to abandon it.

“This was scary. I wanted to bail out. I was unsure. We were all unprepared,” Christensen said.

“The church was a retreat where you go to recharge your batteries and sing beautiful hymns — it’s not where you go to be disturbed and bothered. And then Bill (Youngdahl) wakes you up. Waking up is bothersome.”

But Christensen stayed the course, one that got even rougher when he and his late wife June were ostracized by old friends in the church. A moving scene depicts the couple in a state of emotional exhaustion. A tearful June says, “I just can’t do it anymore.” She appears opposed to going forward. The unseen back story is that she was sick with cancer. The rebuffs she and Ray endured took a further toll.

Far from disagreeing, he said, “We were totally together. As a matter of fact, we had agreed that whatever Bill said, we’d support. That’s how unified we were. It’s too bad the film implies otherwise. When she says she’s tired, she’s tired of the radiation treatments, the phone calls, the cold shoulders, the loss of her friends. She’d founded the altar guild and the acolyte guild and now she’s on the outside.”

“She’s crying for the people of the church,” he says in the DVD.

As Jersey explains in the DVD, “There’s a universal important lesson in the film — that change is hard. That change can be costly, but that resistance to change is a killer. It makes even the simplest efforts impossible.”

Youngdahl said the film is an accurate snapshot of where America and the church were then with regard to race. “Our country had not advanced very far.” Churches included. At its core, Jersey said Burning examines the human tendency for one group to distrust “the other.” “It’s fear that immobilizes people,” he said.

All along Jersey meant to “find a situation where there’s a potential conflict” but never intended showing the church turning its back on racial accord.

“I offered Lutheran Church officials the option to cancel the project and to take the footage, but I wasn’t going to change a thing. And to their ever lasting credit, they said, ‘No, this is the story. It’s an honest film — keep making it.’”

Still, “this isn’t what the church wanted to say about itself,” he said.

Reaction by local church officials was not as positive. Nebraska Lutheran leaders filed a protest with the national executive council, branding the film “a disgrace to the church.”

Soon after its original PBS airing, the film ignited national discourse in reviews and essays. Jersey, Lee, Youngdahl and Chambers were much quoted. The earnest pastor and militant barber even made a joint speaking appearance. Their association with the film made them public figures. But Youngdahl was too embroiled in healing the divided house of his church to care. In the end, he couldn’t square his beliefs with the rancor and resistance at Augustana.

For Johnice Orduna, Burning still has the power to illuminate racism. “The film is a gift in that it reminds us we’re not there yet. It’s not a short war. I’m not going to see it ended in my lifetime,” she said. Racism, she said, is “still there, just a little more hidden, a little better couched. But it’s still burning. We still need to put some heat under it.”

Orduna’s done mission development work for the Lutheran church to promote integration, including anti-racist training workshops. She said, “I find the movie itself is a wonderful microcosm of the time. Watching can be a real wonderful remembrance, but it’s also a real frustration. I’m still dealing with the same frustration of, Why don’t they get it?”

Some years ago she consulted Augustana on blended worship services and found resistance still alive. She said bruised feelings remain among old-liners.

“They’re angry over the film. They feel they got set up. That it showed them at their very worst,” she said. “But that would have been any (white) congregation in this city 40 years ago. The fact it was them is sad for them. I think at their core they’re good people.”

She said few Omaha churches are integrated today. New Life Presbyterian Church — a merger of Calvin and Fairview — is an exception. She said Burning reminds us how far we have to go. “I think it’s wonderful it’s still making people itch…because the things that make us uncomfortable force us to change.”

“A Time for Burning “

Part II

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Forty-two years have not cooled the incendiary 1966 documentary A Time for Burning. Its portrayal of a failed social experiment in interracial outreach at Omaha’s Augustana Lutheran Church, 3647 Lafayette Ave., still burns, still illuminates.

What members were led to believe was a paean to the all-white congregation’s attempts at fellowship with the surrounding African American community turned into a de facto critique.

As pastor William Youngdahl and others pushed “civil rights” at the church, things were stirred up at Augustana. When a group of black high school students worshiped there one Sunday in 1965 — returning a visit white youths made to Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church — it caused a ripple. When white couples considered hosting black couples in their homes it made waves. Burning captured the wake. The fallout led to a rift within the church’s leadership that resulted in Youngdahl’s ouster. Hundreds of members eventually left.

Augustana faced its biggest crisis on the 100th anniversary of its founding.

The film, shot hand-held style, immediately became a sensation for the naked emotions and stark black-and-white imagery that framed the problem of racism against the backdrop of the church. The dark-suited, male-centric piece has a chic Mad Men look today that belies the angst of its real-life, as-it-happened drama.

Near the end of the film the late Reuben Swanson, the church’s former pastor, asks how people can be persuaded “to change their hearts? This is the burning question … ”

Augustana’s remaining members could have closed their hearts and minds to introspection, growth, renewal. Instead, they pursued the more difficult path of facing and overcoming their bias.

“It wasn’t all a political thing, it was a spiritual struggle for people, and a very deep one,” said Vic Schoonover, who helped heal and guide the church in Burning’s aftermath. “This was a struggle for one’s soul and what they really believed.”

Omaha and New York City

This Friday, Oct. 17, the UNL College of Journalism will screen Burning at 1 p.m. with a Q & A to follow with Director Bill Jersey. On Saturday, Oct. 18. Film Streams will again screen Burning, at 2 p.m., with a panel discussion to follow, moderated by current Augustana Pastor Susan Butler . Jersey will participate, along with two key figures in the film. Ray Christensen is the Augustana member who had a change of heart — moving from opponent to timid supporter, and then to outspoken witness for change. Johnice Orduna is one of the teenagers from Calvin Memorial Presbyterian, who speaks out strongly against the response her youth group’s visit evokes at Augustana. On Sunday, Augustana Lutheran will be hosting an interfaith service at 10:30 a.m.

Similar programs are happening the following Monday in New York, where the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is sponsoring a screening of Burning and panel discussion. Longtime Nebraska state Sen. Ernie Chambers, who plays a prominent “role” in the film, is appearing with filmmaker Bill Jersey.

‘Stirred people to their bones’

Today, Augustana is a beacon for an inclusiveness, crossing racial/ethnic lines, to sexual preference/identity. Butler said that as the only Reconciling Church in Christ congregation in the Nebraska Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, Augustana “is welcoming, affirming and supporting of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered believers.”

What transpired at Augustana wasn’t unprecedented. Ministers often get people’s backs up for taking unpopular stances. Tensions rise, disputes erupt. Members of First United Methodist Church in Omaha have endured their own schism, only over same sex marriage, not race.

What set Augustana apart is that its wrestling with controversy and discord was caught on film and aired nationwide. One could argue the parish might never have come to brand itself “a progressive, thinking, Christian church,” as it does today, without Burning as a backdrop for discussion, examination, inspiration and transformation. Longtime member Janice Stiles said the film initially “created a lot of hard feelings” within the church.

“I felt and most of the people felt they only picked out the bad parts,” she said.

Her perspective changed because, wherever she traveled, she met people familiar with the film, and they wanted to discuss it.

“I was really astounded. It gave me another outlook you might say; that maybe it did something good. Much more than we thought. It really was a blessing that we did that,” she said. “It really brought up the feelings and the discussion out into the open, and it needed to be done very much.”

Since the film’s release, the parish has fielded inquiries from around the world. People ask:

“How’s Augustana doing?” It still sparks discussion wherever it’s played. That is what Lutheran Film Associates intended when Burning was commissioned.

“Some of these memories are going to be brought back up again, for better or worse,” Augustana member Mark Hoeger told a recent gathering of church members who watched the film as part of adult forums he led there. The forums were meant to generate discussion and they succeeded, Hoeger said. He also screened a 1967 CBS special on the impact of Burning.

Butler views the programs at Augustana and at Film Streams as educational opportunities.

“My intention is to use this reunion weekend as a time to revisit a particular part of Augustana’s history,” she said. “I think it is always productive to review one’s story from time to time in order to see where we have come from, where we are now and where we are going.”

Butler said reviewing church history can only be healthy.

“I don’t think there is any healing that needs to be done at Augustana. I think we have moved on quite healthily,” she said.

The CBS News special about the aftermath of Burning was entitled A Time for Building.

Moderator Charles Kuralt, Burning co-director Bill Jersey, executive producer Bob Lee and Lutheran pastor Philip A. Johnson discussed reaction to the film.

For the special, Jersey had traveled nationwide and captured audience reactions, including church congregations.

The program ended with members of all-white Our Redeemer Lutheran Church in Seaford, N.Y. deciding to proceed with an interracial exchange. Pastor Bob Benke’s benediction offered thanks “for the willingness of the Augustana congregation to let themselves be seen; for we are well aware of the fact that we have problems here, too.”

Forty years later, Benke is in Portland, Ore., a town Youngdahl also calls home, though the two have not met. Our Redeemer did follow through with interracial youth fellowship, but Benke confirmed the attempt was not well received within his church.

Willing or not, Augustana members found their weaknesses laid bare on screen. for all to see, becoming a mirror for others to do their own inventories and ministries. Introducing the program, Kuralt described the buzz Burning had generated: “It is a film that has stirred people to their bones … “

‘A social tide’

The Hoeger-led forums at Augustana were attended by dozens of parishioners. Most had seen Burning. Few had seen Building. There were lots of questions. For newer members, the most obvious was “What happened next?” The answer is best informed by the context of the film’s troublesome times. The mid-’60s marked the height of the civil rights movement. A great social tide was moving forward and an old-line, inner-city Swedish-American congregation in the Midwest like Augustana felt threatened by change that might disrupt its homogeneous traditions.

More blacks were moving into the area. Cries for black power, equal rights and change by any means necessary (as the late Malcolm X famously put it) disturbed many. Black discontent is well expressed in the film by a young Ernie Chambers as well as Earl Person, Rev. R.F. Jenkins and students from Central High/Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church.

The exclusion blacks felt was tangible. Omaha’s pronounced geographic and social segregation meant whites and blacks lived parallel lives, separate and unequal. The era of white flight saw scores of Augustana members move to The ‘Burbs, a pattern that played out in inner cities across America. The tinderbox of racial tension exploded in riots here and elsewhere during the late ’60s.

Schoonover said those who left Augustana in the decade following the film did so for many reasons, “but the rapidity and the intensity of it I directly attribute to A Time for Burning.” Now a retired minister, he’s an active member of Augustana.

White-black interaction was so thoroughly circumscribed that the mere suggestion of interracial exchange concerned enough Augustana members that the proposal was defeated and Youngdahl forced to resign.

Heated discussions ensued, prejudices surfaced, conflict escalated and resistance held fast. Filmmakers Jersey and Barbara Connell captured fears and doubts that usually remain hidden or silent. The film is a prism for viewing all people’s struggles with race.

Burning uncovered racism among otherwise decent, churchgoers. Unfortunately, Augustana took the fall for the bigotry, cowardice and hypocrisy of the larger white Christian church and society. Its members scarred with the celluloid scarlet letter, when virtually any white congregation would have looked that way under the same scrutiny.

“I think A Time for Burning was a slice of the American church wherever you would have cut it in those days,” Schoonover said. “There was racial tension all over the city and the country. White congregations were not really ready to face the whole racism issue. They wanted it to go away.”

He said the film resonated with audiences everywhere.

“If people across the country hadn’t identified with that on a personal level as well as a just oh-my-gosh level, it would never had had the popularity that it did. It hit chords in people,” Schoonover said.

Hoeger agreed, saying “ … this was not the story of a single congregation, it was the story of our society, our community in general. People could see in this bunch of white Lutherans themselves.”

But for Augustana members, a stigma was attached to their church that made it/them a symbol or scapegoat for prejudice.

“To a certain extent the congregation was sacrificed for a greater good and in that sense probably deserves some credit,” Hoeger said. “The pain and suffering they went through as an institution led to a larger, better good. And frankly, we think, it’s a better congregation than if it had not gone through that experience.”

Indeed, as Building brought out, people admired Augustana for initiating steps to deal with race. Hoeger and Schoonover said they elected to worship there because of the church’s role in the film, not in spite of it.

Hoeger first saw Burning in grad school, where it was held up as the pinnacle of American cinema verite. He recalls being struck this searing drama set in his native Nebraska. When he and his wife moved to Omaha in 1980 their “church shopping” brought them to Augustana without realizing its connection to the film. The day they went there, Schoonover led the congregation in confessing their sexism, typical of the radical liberal sermons he delivered.

It was only then, Hoeger said, “it clicked in my head this was THAT church” from the film.

He was hooked. He was also intrigued by how Augustana had so drastically changed in 15 years. Hoeger discovered it had been a process led by Schoonover, fellow pastors and a lay leadership willing to “embrace change.” The groundwork for that change can be traced to Burning.

In 1969 Schoonover accepted a call to lead Lutheran Metropolitan Ministries in his hometown of Omaha. His social justice mission tasked him with confronting racism in the Lutheran Church and wider community. Following Youngdahl’s exodus Augustana had a “quiet-things-down, not-rock-the-boat” pastor in Merton Lundquist who, to his and his lay leadership’s credit, began doing more minority outreach, Stiles said.

Schoonover joined Augustana and within a decade was asked to pastor there. He shepherded to completion a year-long self-study begun by Lundquist at the church on its future. Ironically, the church that drove off Youngdahl got a bigger troublemaker in Schoonover.

Vic Schoonover today

‘Hit square in the jaw’

When Schoonover began preaching he sounded-off on integration, police-community relations, poverty, prejudice — both from the pulpit and in his work with the activist group COUP — Concerned Organized for Urban Progress. He quoted Stokeley Carmichael. He once called America “a structured racist prison.”

COUP’s overtures to and advocacy for the black community made Schoonover a target. “I had to move my family into a motel because we had anonymous threats of doing harm to us and to our property,” he said.

His less militant stands led him to co-found a handful of social service programs still active today, including the Omaha Food Bank, Together Inc. and One World Health.

Schoonover was attracted by what he found at Augustana. “I thought, here was a congregation that at the very least was forced to begin to look at the issues and maybe had made some progress,” he said.

The people were, he said, “in any other circumstance some of the most generous people I’ve ever known.”

“They would do anything for you. Really good-hearted. But on that issue (race) it was a blind spot,” Schoonover said. “It’s a dichotomy. But that’s what they were taught. Because I don’t think it’s possible for any white person to be raised in our country without being raised a racist and a sexist. I just think it’s in the air you breathe and in the systems you get socialized in.

That’s the milieu in which you live and — that’s what you absorb.”

Janice Stiles acknowledged the blind spot she had in those days. She recalled her feelings when blacks moved in.

“All I could think of was the price of my house going down,” she said.

She recalls when her son Mark became friends with a black schoolmate. At first, she was bothered by it. She gradually changed.

“I started looking at people and seeing what’s on the inside instead of the outside. I’m glad I got to know black people as people.”

Schoonover was also the product of a myopic vision. He grew up on Omaha’s north side, where his family kept moving, in white flight mode, as neighborhoods were integrated. His own “baptism” or “awakening” came as a young minister in Kansas City, where he “took a class taught by black clergy called Black Power for White Churchmen,” he said. “It cleared my eyes open to some of the problems.”

After interacting with Augustana members, he said, he “really became aware of their anguish” over the film and how it held them back.

Some felt it unfairly made them an example. Some accused the filmmakers of betraying their trust. Others believed the film presented a gross distortion of them and their church. After all, much of the conflict in the film went on behind the scenes, in private, in the inner circle of the church council. That’s why most members who went to the Omaha premiere were shocked by the friction Burning depicted.

“They all traipsed to the world premiere at the Joslyn in their best bib-and-tucker and got hit square in the jaw,” Schoonover said.

As if being exposed in that way were not enough, the film became a phenomenon — the subject of untold screenings, reviews, essays, articles, public programs, debates.

Burning aired coast to coast, prompting the CBS special. The film earned an Oscar nomination. It’s been used in film/social studies programs and diversity training. In 2005 it was selected for the National Film Registry.

Thirty-odd years ago the wounds were still fresh enough that Schoonover discovered members didn’t want to relive the film. Understandably, they didn’t appreciate being a whipping post, as they saw it, for a national dialogue on race. When he became co-pastor there in 1976, he decided to bring it out of the closet.

“It wasn’t mentioned, it wasn’t something talked about, it was something avoided in the congregation,” he said. “They were traumatized. They felt totally betrayed, misled. I knew we could never get healthy without confronting it, so we bought a copy of the film and began showing it. The young people were especially interested.”

Thus, Burning became a conscience or barometer for the parish to measure itself. Older members may not have realized it, but outside its walls Burning wasn’t viewed as an indictment or condemnation of Augustana, but as a challenge for America to confront the nation’s racial divide. That’s why the film endures beyond being a mere artifact of ’60s racial tension. Instead, this document of a congregation struggling with its worse nature was the impetus for that same congregation, and presumably others, to realize their better angels.

‘You’re already dead’

At the end of Augustana’s year-long self-study, the congregation was faced with several options. Stay and expand the ministry, merge/relocate, close or continue as is. The parish council recommended remaining and expanding its inner-city ministry. Put to a vote of the general membership, a majority opted for the council’s recommendation.

“It was a test for the parish and to their credit they said, yes, and we did,” Schoonover said.

His sermons helped sway the congregation to stay its new course. He cautioned against being mired in old ways, old attitudes.

“The past cannot be brought back,” he told them, “and the way things were is irretrievable.”

Janice Stiles said his preaching exerted much influence.

“Oh, yes, he opened our eyes to so many things,” she said. Rather than criticism she said “it was more like a challenge.”

Despite empathy for his flock’s distress, Schoonover didn’t let them off the hook or allow them to rationalize or minimize their reluctance to accept diversity.

“I told them, ‘Look, I understand your pain, but what the black people have felt far surpasses any pain you have felt.’ I was extremely blunt about what they faced and what it meant and what it would require of them. I said, ‘If you don’t do this, you’re already dead. You’ve got to change. You don’t have any choice.’”

One of his sermons put it this way: “ … There is no place you and I can go to hide from change. We might wish things would leave us alone but this will not be … Organized religion has often been in the conservative role of resisting change. This has often been at the cost of truth and integrity. A congregation can lose touch if it is static and immovable. It’ll become irrelevant … ”

From that crucible, Augustana evolved into the progressive place it is today. The rupture that divided the church allowed Augustana to reinvent itself.

“By splitting the church and creating this schism,” Hoeger said, “those who were left were the core of folks who were more socially aware, concerned, interested in embracing change then the folks that were upset … There are still some people here who I would consider very conservative, but what differentiates them is they were willing to stick with it.”

The film that created this house divided also helped repair the breach.

“In the end run I think whether they realize it or not the film was worth it … It certainly changed the direction of that congregation, that’s for sure,” said Schoonover.

It’s meant Augustana engaging in urban, interfaith service-mission ministries.

For example, the church is active in the ecumenical social action group Omaha Together One Community, OTOC offices there. Augustana’s Cornerstone Foundation addresses the inner city’s shortage of affordable-livable housing by buying-fixing up homes for low-price resale, or refurbishing residences that owners don’t have the means to renovate.

In the late ’60s Augustana and nearby Lowe Avenue Presbyterian Church launched Project Embrace, a summer youth enrichment program for minority kids. At one time, Embrace included an after-school tutoring program serving thousands of kids at six churches. It has dwindled to a summer-only program at Augustana and two other churches. The integrated Danner day care operated for years at Augustana.

Schoonover carried those relationships over to the larger black community through Augustana, where he performed weddings, funerals and confirmations for blacks. Some blacks began attending the church. A few became members. As did Hispanics. Several Laotians, whose immigration the church sponsored, joined Augustana. He said those experiences “helped win the congregation over.” Stiles was among them.

“It was our occasion of getting to know a different race,” she said.

Even as barriers at Augustana have vanished, blacks still comprise only a small fraction of the parish rolls.

Vic Schoonover would say Janice Stiles is representative of the changed hearts that can move institutions forward. He acknowledged much work remains to be done.

“I go from hope to despair on the whole racial issue,” he said. “From thinking, ‘Yeah, we have made some progress, to thinking, Geez, we’re not any further along. We’ve just become more subtle, more guarded about it. Not much has changed.’”

As Bill Jersey said in Building: “Until the individual is willing to say what I can do, we’re going to continue with all this pious dialogue and get nowhere.”

The tragedy in that, everybody agrees, is that as the beat goes on, the flames still burn. Who will put out the fire? And what will heaven say if we had the chance but didn’t act?

Related Articles

- Faith in Memphis: Color-blind church an audacious experiment (commercialappeal.com)

- Sunday morning remains segregated (religion.blogs.cnn.com)

- Reverend: If Heaven is integrated, why not churches? (cnn.com)

- Get On the Bus, An Inauguration Diary: My Story is a Companion Piece to New Documentary Charting An Inaugural Ride to Freedom (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Today’s Exploration: Omaha’s History of Racial Tension (theprideofnebraska.blogspot.com)

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omowale Akintunde’s In-Your-Face Race Film for the New Millennium, ‘Wigger,’ Introduces America to a New Cinema Voice (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Everyone’s Welcome at Table Talk, Where Food for Thought and Sustainable Race Relations Happen Over Breaking Bread Together (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Overarching Plan for North Omaha Development Now in Place, Disinvested Community Hopeful Long Promised Change Follows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- North Omaha Champion Frank Brown Fights the Good Fight (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Burden of Dreams: The trials of Omaha’s Black Museum