Archive

From the Archives: Cowboy-turned Scholar Discovers Kinship with 19th Century Expedition Explorer

NOTE: My apologies to those who read this post when I first put it up, as it was filled with typos. I failed to proof the copy and it made for a very rough read. It won’t happen again.

With this post I am starting a periodic series featuring favorite stories of mine from deep in my archives. The story below is from 1990 and profiles a charming man, Paul Schach, who has since passed. I got to know Schach just a bit when I worked as public relations director at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha. My friend, then Joslyn western history curator Joseph Porter introduced me to Schach, who was engrossed in a multi-year translation project of a vast set of journals or diaries that German explorer Prince Maximilian of Wied kept of a historic expedition he made of North America. The 1832-34 expedition also had a fine artist along, Karl Bodmer, who made sketches and watercolor paintings of the vanishing West. The Maximilain diary and the Bodmer artworks are in the Joslyn’s permanent collections and I was struck both by how uniquely suited Schach was for the project and by how deeply connected he felt to Maximilian.

Also on this blog is a story I did a few years later about an artist who drew inspiration from the life and work of Karl Bodmer. That piece is titled, “Naturalist-Artist John Lokke – In Pursuit of the Timber Rattlesnake and in the Footsteps of Karl Bodmer.”

From the Archives: Cowboy-turned Scholar Discovers Kinship with 19th Century Expedition Explorer

©by Leo Adam Biga

Orignally published in Omaha Metro Update (now Metro Magazine)

In his 52 years as a language scholar retired University of Nebraska-Lincoln professor Paul Schach has seldom strayed far from his German heritage and rough-and-tumble roots. It’s only fitting that Schach, who loves a good yarn, has lived a storybook life – from cowboying along the Arkansas River to doing top-secret intelligence work during World War II to forging a distinguished academic career.

Until his 1986 returement Schach held the Charles J. Mach professorship of Germanic languages at UNL, where he taught 35 years. The noted philogist has traveled widely to record and study ethnic languages and literary traditions native to Northern Europe. He’s published his work in scores of articles and eight books.

Schach’s work has taken hiim to Denmark, Sweden, Iceland and Germany. A companion on some of his overseas trips was his late wife, Ruth, who was also a colleague. She typed and proofed all his work during their 48-year marriage. In 1956-57 the couple and their three daughters lived in Germany, where the children attended public school while Schach taught and worked on a book.

“Ruth typed the manuscript of the first book I ever published, during the winter of 1956 in Germany,” Schach said. “That was a cold winter and buildings were only heated two hours out of 24 because of fuel shortages. I would come back home at noon for lunch and she’d be at a little red Remington portable typewriter.

“She had a sweater, overcoat, woolen cap and scarf on. She’d type for awhile, stop, blow on her hands, put on gloves, blow on her hands a bit and then type a few more sentences. And that’s how that first book came to be typed. I’m just beginning to realize now she did about half my work for me. I got the credit for it – she did the work.”

Today, the 74-year-old is still busy writing and researching, only now his daughter Joan is his proofreader. Schach hopes to finish three books yet. But one project in particular has occupied much of his attention the past three years. It’s the translation of the diary kept by German explorer-naturalist-ethnologist, Maximilian Furst zu Wied of his 1832-34 expedition to North America with Swiss artist Karl Bodmer.

Maximilian’s chronicles, along with Bodmer’s paintings and sketches, document their historic journey along the Missouri River. The diary, artwork and related articles are housed at Joslyn Art Museum‘s Center for Western Studies, where Schach commutes from his Lincoln, Neb. home to work with the original manuscript. Scholars regard the collection as an unparalleled record of the early American West.

Prince Maximilian

Translating the epic, 4,000 -page diary is painstaking work which Schach is uniquely qualified to do. He grew up speaking and reading a dialect very similar to Maximilian’s – one few are fluent in today. As a boy Schach reveled in stories told in German by his extended immigrant family.

Schach’s work is made more difficult by Maximilian’s tiny script, which can be read only with the aid of a magnifying glass. The diary will be published in four volumes by Joslyn and the University of Nebraska Press. Schach has only a final reading to do before volume one is published within a year. Work on volume two is nearing completion and by July Schach said the translation project should reach its halfway point.

His careful reading and meticulous translation of Maximilian’s observations have put him on intimate terms with the man, whom he feels a close kinship with by virtue of their shared dialect, heritage and interests. Strengthening the bond is the fact Maximilian spent a summer in Pennsylvania, where Schach was born and raised.

“I’m seeing parts of that state much more clearly now through his descriptions. So many of the things he describes are things I have experiencd in my life,” said Schach.

Just as Maximilian spemnt a lifetime as both a rugged outdoorsman and rigorous scholar, so too has Schach. During his long career Schach has remaimed true to bedrock values learned as a boy gorwing up “mainly in mining camps and cow towns” during the Great Depression.

Despite harships, he enjoyed an arcadian youth in the fertile back country of eastern Pennsylvania’s anthracite coal mining region, where he developed a lifelong love for the great outdoors.

“Until I was about 20 I lived outdoors whenever I could – hunting, fishing and trapping. My father was a coal miner. Some days he’d strike it rich, and then for weeks he wouldn’t have any money at all. We spent quite a bit of our free time fishing and hunting for food. Yes, times were hard, but people in those times were hard, always shared things. Everybody helped everybody else. I was always being farmed out to work on different farms when someone got hurt or sick.”

Schach learned a healthy respect for nature and the land from his maternal grandfather, nicknamed the “Old Black Hessian” for both his dark features and horse-trading skills.

“When people came and wanted to buy soome wood on his farm, he refused to sell. They said, ‘We’ll pay you more money for those trees than you’ll get for the rest of your farm.’ ‘It belongs to the farm,’ he replied. ‘Well, the farm belongs to you, doesn’t it?’ He wasn’t quite sure,” Schach said, “because it would go to his son or daughter. It was his farm, but it was there for people to use and the idea was to make it a better farm then when he got it from his father.”

Schach laments, “There’s not so much of that (philosophy) “left anymore – people are mining the soil and destorying the forests.”

A Karl Bodmer watercolor from the expedition

He said Maximilian espoused the same Old World wisdom and was “shocked, even at that time, at the way Americans were destrorying their forests and their soil. In Europe, if you cut down a tree you have to plant two to replace that one.”

According to Schach, Maximilian’s enlightened environmental concerns were typical of a man who was ahead of his time. “There were so many ways in which he was so very modern, such as the idea of conserving the soil and forests. There’s so much to learn from a man like this.”

Far from a rural idyll, however, life for the Schachs was full of severe trials, just as Maximilan weathered blizzards, epidemics and other miseries on his trek.

Then there were the man-made problems the Schachs and their neighbors confronted.

“There was a lot of trouble in the coal mines,” Schach said. “The owners would shut down the mines so the miners wouldn’t ask for more wages. You couldn’t even buy coal in the coal regions – you had to go out to slag dumps at night, where we were shot at frequently. My father wanted to get out…there was just no future there because he didn’t own any land.”

The family pulled up stakes and headed west. They settled in Colorado, where Schach’s father hoped to dig for gold but was disillusioned to find “the gold mines had petered out just as coal had in Pennsylvania.” He opted for running a grocery store instead.

Schach helped support the family of eight by working as a hired hand on a cattle ranch along the Arkansas River, riding horseback in the shadow of Pike’s Peak. The full-fledged cowboy broke wild horses, drove cattle and lived a Western life most young men only dreamed about.

“I enjoyed working on the farm and especially on that ranch. Coming from the East to the West, I suppose, made it more romantic.

“We used to move the cattle up in the spring to a higher pasture in the mountains and then, in the fall, bring them down. When you brought them down they were just as wild as buffalo. you could handle them on horseback, but on foot they’d either run away from you or they’d come right at you, in which case you ran for the closest fence,” he recalled, laughing heartily.

“I liked working with horses, but I guess I was never too good at it because I’ve been banged up pretty badly several times.”

The last time he tried taming a horse was just 10 years ago. The result: three broken ribs. Years later he still feels the effects and carries the scars of his horse spills. He joked that it’s open to question whether he broke horses or they broke him. “But I still love them,” he said.

Schach passed on what little horse sense had to two of his daughters, who are “very good with horses.” He sometimes goes riding with them at a local stable. But to his daughters’ amusement a bronco buster’s old habits die hard. He’s been bucked, bitten and kicked enough times that he mounts any horse, even a tame one, as warily as if it were a time bomb.

“I set up close to the shoulder, facing the back, so he can’t get me with his foreleg. I pull his head away from me so he can’t bite me. And I watch his hind leg and am conscious to get my left foot in the stirrup and to swing into the saddle. Then I wait to see what’s going to happen. Of course, with these horses around here, nothing happens. He just sits there,” said Schach, who delights in telling the story.

A Karl Bodmer watercolor from the expedition

He exchanged a saddle for a school desk in the mid-’30s, when he enrolled at Albright College in Reading, Pa. Although he was a roughrider, Schach always found time for books and writing. He had as his models two older sisters who taught school.

“I always read a lot. I read German and English from the time I was 5. I used to keep notebooks with lists of all the words I could find in German and English of colors, for example. Or synonyms of all kinds.”

He was immersed in his people’s rich reservoir of culture and language. “The Old Black Hessian was a marvelous storyteller. I remember one story had two different endings. When I was about 10 I got up enough courage to ask him which of the two stories was the true one. He looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘Paulos, the one is as true as the other,’ which was a marvelous answer.”

Schach, who’s recorded German immigrant dialects from Canada to Texas, has collected Russian-German folktales handed down through generations. He cherishes both the grassroots education he got at home and his formal training in high school. He feels today’s students are shortchanged.

“If you intended to go to college you had to have a thorough knowledge of French, German and Latin. You took science and math courses straight through, including trigonmetry and geometry. I would say graduates of my high school in 1935 or so had a much more solid education than the average college graduate today.

“We’ve lost touch. I read European newspapers all the time…people all over the world are talking about what’s happened to the United States, how we’ve fallen behind in science and can’t make anything that meet their standards. The neglect of languages has been a terrible handicap to our country and we have suffered greatly from it, too.”

He believes language studies are vital “not only for what they tell us about language” but for what they reveal about culture, history and ourselves. As an ethnologist, Maximilian studied the cultures and languages of Native Americans from a humanist perspective rare for expolorers of the period. His progressive learnings helped him empathize with the Indians while his scientific training lent his descriptions great objectivity. He approached the study of Indians not as something strange, not as the savages we’re used to reading about in cowboy and Indian stories, but as human beings. He didn’t idealize them. He didn’t denigrate them. They were people – good, bad, indifferent – and he just portrayed them as they were,” Schach explained, adding that Maximilian’s accounts are treasured for their wealth of detail and accuracy.

Statue of Karl Bodmer and Prince Maximilian at the Castle of Neuweid in Germany

Maximilian, whom Schach described as “a very well-educated man,” had both a priviliged and liberal upbringing. A nobleman by birth, Maximilian’s inherited title was Prince of Wied. His grandfather had established the city of Newied, on the banks of the Rhine, as a refuge for victims of religious persecution. The family castle was located there.

“Early on, Maximilian was in contact with peoples of all nationalities, religions and so on,” said Schach. “I think this was a big help to him when he studied the Indians.”

Schach’s own educational pursuits have been diverse. After graduatiing from Albright in 1938 he began work on his master’s degree at the University of Pennyslvania. Before finishing his thesis, World War II erupted and Schach soon found himself putting his language skills to use in the U.S. Navy. He was the only U.S.-born member of a translation project team assigned the top-secret duty of translatiing captured documents on Germany’s jet propulsion and rocketry programs.

“As soon as they developed something, we knew about it,” said Schach. “The material was easy to read and understand, but we had no (compatible) terminology in English. We hadn’t done anything in those areas yet. We literally had no words to translate into English. That was a strange and a frightening situation.”

It was all the more frightening, he said, because “we knew the V-2 was designed for an atomic warhead. We also knew there were German engineers who could construct an atomic bomb.”

The stateside team based in Philadelphia did hands-on work as well – once reconstructing a Messerschmitt 262 from parts of three of the German jet planes that had crashed. It flew, too. “I guess that the first jet plane to every fly on this country,” he said.

After the war Schach taught at Penn, where he also earned a doctorate. He taught several years at Albright and at North Central Collge in Chicago. He joined the UNL staff in 1951, lured by the opportunity to study the area’s many varieties of German, Czech and Scandinavian dialects. Another factor was Lincoln’s close proximity to Colorado, where the Schachs often vacationed summers, roughing it in the outback.

“We never had much money. The salaries were miserable then. One summer we had $75 – I took the tent, a gun and my fishing pole and we all headed west in the car.” En route to Colorado their meager funds were cut by a third when a flat tire needed replacing. To conserve money that summer the family ate whatever Schach hooked or shot. “We ended up eating mostly fish that summer. At one point the children just sort of sat and looked down their noses at the fish, and Ruth said, ‘You better go to town and buy some hamburgers.'”

Until recently Schach still hunted regulalry, favoring the Nebraska Sand Hills for ducks and the Pine Ridge area for deer. He ventured as far north as Ontario, Canada for bigger game, including a bear he bagged with one shot.

Translating Maximilian’s diary leaves precious little time for the outdoors these days. “I’ve become perhaps too much interested in the man. This is one of only several major projects I’ve been working on. But it’s like reading a good book – you read it four times and you see things you didn’t see the first time. Maximilian was a very remarkable person.

Some would say Schach is no slouch himself.

Related articles

- Smithsonian Archives unveils new website (gadling.com)

- A World We Have Lost (online.wsj.com)

- From the Archives: Opera Comes Alive Behind the Scenes at Opera Omaha Staging of Donizetti’s ‘Maria Padilla’ Starring Rene Fleming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Eighty Years and Counting, History in the Making at the Durham Museum (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Young artist steps out of the shadows of towering presence in his life

Legacy is a powerful thing, and when the shadow cast by a an older, highly accomplished figure looms large it can be a paralyzing specter of expectation to live up to for a young person following in those footsteps. In the case of the late celebrated realist figurative artist Kent Bellows, his larger-than-life presence in life and in death has not stymied the emergence of his talented nephew, Neil Griess, who is very much charting his own path as an artist to be watched. The following piece I did on Griess for The Reader (www.thereader.com) appeared three years ago, fast on the heels of Griess, then a high school senior, winning the same national award his uncle Kent Bellows had won 40 years earlier. Now, Griess is a college senior at the University of Nebraska, where he’s a studio art major, and is once again making waves with his work. Griess, who like his uncle did creates elaborate sets for his hyper-realistic paintings, had a work selected for a show at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art in Omaha in early 2011 and another of his works has been selected for a new show, The Fascinators, the inaugural Charlotte Street Biennial of Regional BFA/MFA Candidates at La Esquina in Kansas City, Mo. You can read a short piece I did about Neil’s famous uncle, Kent Bellows, on this blog.

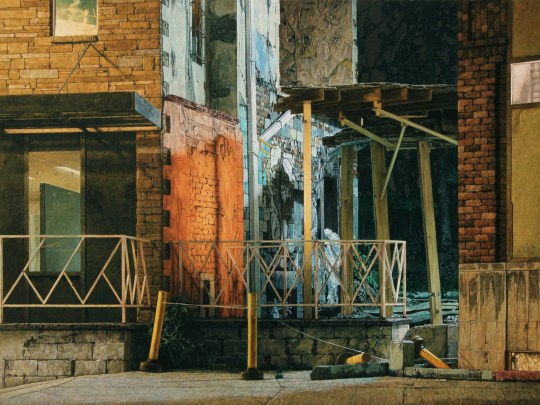

©Neil Griess, “Site Measure” (2010), oil on panel

Young artist steps out of the shadows of towering presence in his life

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the The Reader (www.thereader.com)

If 18-year-old award-winning visual artist Neil Griess of Omaha feels pressure to live up to the legacy of his maternal uncle Kent Bellows, he doesn’t betray it. Work by Bellows, the late American master of figurative realism, is in major private/public art collections. We’re talking the Metropolitan Museum of Art here.

In 2005 Bellows died at age 56 of natural causes in his Leavenworth Street studio/home, now preserved by the Bellows Foundation as an education center. The Omaha iconoclast was a player in New York art circles via his association with the Tatistcheff and Forum galleries. His paintings/drawings sold out wherever they exhibited. Interest in his work continues high.

A May Westside High School grad, Griess has far to go to reach such status, but perhaps not as far as you’d think. With his parents Jim and Robin Griess and his Westside art teacher Shawn Blevins on hand at New York City’s Carnegie Hall on June 15, Griess accepted the Portfolio Gold Honor in the national Scholastic Art & Writing Awards, which included a $10,000 cash prize. Griess, one of 12 Portfolio Gold winners from around the nation, trod onto the hallowed stage to accept the award. The presenter draped a large gold medal over him as the full, black tie-attired house applauded.

Forty years earlier Bellows won in the same competition. Other name artists have won, too, including Richard Avedon and Andy Warhol. The recognition brought Bellows scholarship opportunities at prestigious art schools. Griess too has been deluged with offers. Bellows studied at then-Omaha University. Starting in the fall, Griess will study at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln under realist painter Keith Jacobshagen, a friend of Bellows.

What makes the prospect of Griess’s future development alluring is that he works in the same style as Bellows did — meticulous realism. Their dense work renders persons, objects, settings in such rigorous detail that it draws viewers into an infinite space invested with meaning. With almost any Bellows, Griess said, “it feels like you can get lost in it.” Even up close, he said, “you can’t really derive how he did it.” The technique and the process are as invisible and ineffable as Bellows was enigmatic.

Griess said he’s always been drawn to realism. “Yeah, I always thought realistic work is the direction I would want to go if I continued art,” he said. He can’t exactly pinpoint why. “I don’t know. It’s interesting,” he said, “because you’re not trying to reproduce this object or this person…but more capturing it, I suppose, in a specific moment, a specific point in time.” Or as Bellows once put it in an interview, the goal is to capture what’s beyond the photograph to “what is actually happening…to capture the subject’s soul…the subject’s inner life.”

“And that’s something I wanted to try to do with the eight paintings for my portfolio,” Griess said. “I think if something’s rendered so fully and to its ultimate height, it feels like you can enter the work and like feel that draped cloth in a piece,” he said, referring to a Bellows print on the wall of his home, the image’s tactile realism begging to be touched.

Naturally, Griess aspires to reach the mastery of Bellows, but by no means does he intend to be an imitator.

“I wouldn’t say I’ve tried to emulate him, although in certain instances I was when I was like really young, drawing based off some of the nudes he had done,” a smiling, nearly blushing Griess said, wiping his soft brown bangs from his face.

He’d especially like for his work to attain the openendedness that Bellows captured. In a Bellows work no single prescribed meaning is imposed on the viewer; rather the image invites viewers to glean their own meanings.

“That’s a quality I want to develop myself,” Griess said.

The process Griess uses to create his own work, much of it completed in a small, well-lit downstairs home work space he calls “thrown together” but that is neatly arrayed with brushes, pencils, acrylic paint tubes, is in the vein of photo-realism. He first photographs his subjects and with the resulting image as a guide he uses a pencil to map out the canvas before painting.

“I always paint based off pictures (photographs),” Griess said. “I grid everything out. I take that approach. Laying out a painting you still need to draw. It’s an important skill for getting things right when you finally start painting.”

The artist applies a clear plastic grid over a printed out photo of his subject and with a pencil divides the surface into squares running the length and width of the image. He transfers his grid to a board, which is what he paints on these days. He begins by drawing the major shapes or forms contained in each square onto the board before applying brush to paint and brush strokes to board.

“I pretty much just figure out where one square in the picture would be on the board and then from that one square I go to the next one” and so on, he said. “I add the smaller details later.”

Griess shares many predilections his late uncle indulged, including a love of film, a fascination with the fantastic, a passion for creating elaborate sets or backdrops for his work, although to date Griess has only employed sets to stop motion animation, and an interest in action figures and miniatures. Then there’s the fact Griess is left-handed, just as Bellows was.

“A lot of things line up like that,” Griess said. “Because I know he’s done all this great work it’s kind of like me now trying to discover what things I’m interested in beyond his work…to decide what I’ll ultimately be doing in my art. Of course this is an influence I’ll always keep while doing it.”

©Neil Griess, “Untitled” oil painting

The art strain runs deep, as Griess’s maternal grandfather was a commercial artist and watercolorist, his mother is a watercolorist, one brother is a ceramicist/sculptor and another brother writes computer video game programs. “So I come from a long lineage of artists or creative thinkers,” Griess said.

Growing up, Griess was exposed to dozens of Bellows prints that adorn the walls of the family home. One of the nephew’s favorites, Nuclear Winter, is displayed in his bedroom. He felt drawn to Bellows as any adolescent would to a cool adult doing his own thing. “I admired him so much. He was probably the most charismatic, funny, interesting person that I know or probably will know,” Griess said.

The parallels between the two were obvious two weekends ago in New York City. It was the kid’s first time in the Big Apple, where in a whirlwind few days his path intersected with the path Bellows took in setting the art world on fire.

Just as Bellows attracted notice beyond his years, once cultivating Warren Buffett and his late first wife Susan Buffett as patrons, Griess, too, found himself the center of attention from older admirers at a post-awards dinner. The scene was the ritzy Mandarin Oriental Hotel on Madison Avenue in Manhattan. There were congratulations, even autograph requests. “I got some very great compliments,” Griess said. Among the well-wishers was New York thespian Jason Butler Harner, who hosted the awards.

“He seemed very enthusiastic and impressed by my work, so that was great,” Griess said of Harner. “One of the guys that asked for my autograph said everyone was kind of talking about my work specifically, and that was nice. One woman actually came up to me and said my work brought tears to her eyes because of how young I am and I’m able to produce work like that.”

The plaudits began the night before, at Reeves Contemporary gallery in Chelsea, where selections of work by Griess and other Portfolio gold winners were shown. It was then, Griess said, that Alliance for Young Artists & Writers Chairman Dwight E. Lee “told me how much he loved my work.” At dinner the next night, Griess said, “he gave me his card and said if I should ever want to sell art work I should contact him.” Westside teachers and others have expressed interest in buying Neil’s work.

“I’m actually selling paintings this summer,” Griess said. “I’ve sold one already, so I’m starting to learn how it feels to part with something.”

As if that wasn’t enough, the June 14 issue of USA Today reproduced one of his paintings to illustrate a Life Section story on the awards. “The one picture they chose was mine — my painting Pool Boy,” Griess said. “That was a really nice surprise. My dad ran up and down the floors in the hotel acquiring more” copies.

Pool Boy is one of many self-portraits and portraits Griess has executed. Portraiture was a favorite form for Bellows as well. One difference is that while Bellows was known for a dark, brooding nature that made him look severe if not downright scary, Griess has a sweet face and demeanor. That’s not to say there wasn’t whimsy in Bellows or his work or that Griess and his art is all peaches and cream.

The award, the praise, the contacts, Griess said, “are obviously great exposure for me and a great thing I can put on the resume. I would say it’s probably the best recognition I could have received operating within a high school.”

Griess submitted eight works to the Scholastic competition but gave little thought to winning, as he photographed his entrees himself and the images he submitted were less than flattering to the works themselves.

“Because of the fact I did not have great pictures of these paintings I submitted, I kind of dismissed the idea that anything would happen with this,” he said. “But then I got the call (saying he’d won) and I couldn’t really believe it for a good amount of time. I was basically sitting at home on a Friday night when I got this call out of the blue. I was pretty unprepared…Surprisingly. I think I handled it well, although afterwards I was like shaking in disbelief for 15 minutes.”

The artist created his winning series for Westside’s Advanced Portfolio class, which he said allows student artists rare autonomy in finding their vision-voice.

“Not many high school classes give you that much freedom in developing your own line of thinking for a series of paintings…I think it kind of helped me develop my own thinking for how I want to approach my art,” he said. “In the typical class you kind of just think in terms of the assignment and what they’re expecting you to see as the outcome, not how you would best display your own ideas or get your own point across.”

Griess hit upon the theme of high contrast at night, playing with different light sources. Some of the inspiration for what’s depicted in the work, he said, comes from Russian fairy tales — “I’ve always been interested in fairy tales” — and some of it comes from what was going on in his life at the time. His girlfriend, Erica, a film studies major at Northwestern University, is the subject of more than one work. She’s a casual portrait study in a piece called “Home Again” and her absence informs another piece in which an anxious Griess cowers on his front porch, alone at night, a doll seen inside a window providing no solace.

“With some of my paintings I first kind of get like this mental image and then when I’m painting it, even weeks after, I start to think about why I needed to do that or what was the significance of it,” he said.

©Kent Bellows’s self-portraits

Just as Bellows sought out great art in his travels, Griess spent his weekend in New York soaking up treasures at the Met. He and his folks also made special visits there and to the Forum gallery to see Bellows’ work in each venue. The splendor of it all, Griess said, “made me want to go back home and start working again.”

Griess didn’t need all the hype to feel an artistic kinship to his uncle. He just wished Bellows could have been there. “I was probably more wishing he could have been involved in this with me and seen the work I did to win this award,” he said. He regrets too never discussing their shared sweet affliction. “I was a shy kid and probably still am. I wouldn’t have necessarily been ready to talk with him about art or these other interests we shared,” Griess said. “Now I would say I would definitely be ready to talk to him about things.”

It’s probably unfair to say Griess lived in the shadow of Bellows, but Bellows was a giant among artists and a looming presence in the life of the the sensitive young artist-nephew. A legacy he could not escape. Griess wasn’t necessarily a slacker before Bellows’ death, but then again he acknowledges he didn’t exactly apply himself to his art. When Bellows passed, Griess suddenly got busy, approaching his own art with a greater sense of urgency.

“After his death is when I really started to get serious about drawing and painting and that’s when I started to do better things and win awards,” Griess said. “I realized he would no longer be there to kind of give me advice or look at what I’m doing, so in some strange way that pushed me, It was kind of a way to deal with it. I mean, also I realized I need to be doing this for myself, too.”

Related articles

- An Inner City Exhibition Tells a Wide Range of Stories (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Art from the Streets (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Soon Come: Neville Murray’s Passion for the Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its Role in Rebirthing North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Frederick Brown’s Journey Through Art is a Passage Across Form and a Passing On of Legacy (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Artist Bernard Stanley Hoyes Explores the Lamentations and Celebrations of Jamaican Revival Worship (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

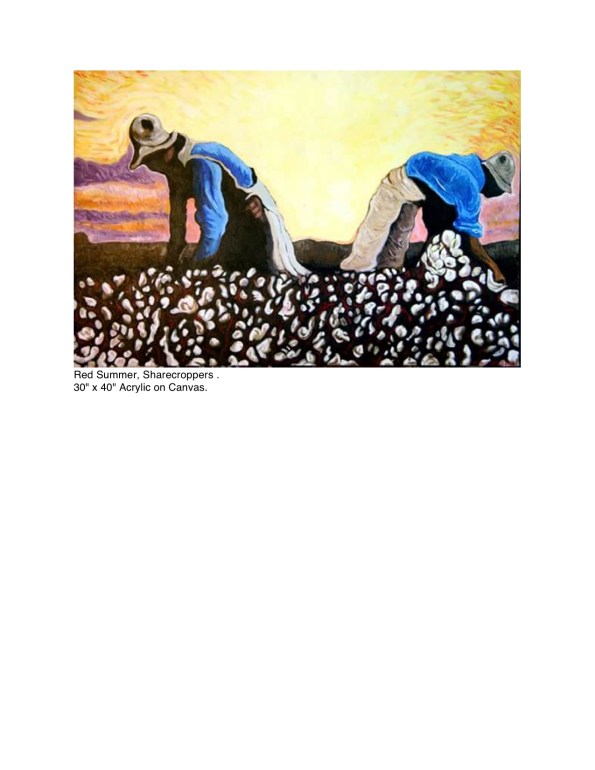

Inner City Art Exhibition Tells Wide Range of Stories

Loves Jazz & Arts Center’s 4th Annual African-American Art exhibition, Telling Our Stories, displays work by some two dozen artists.

The stories of four of the featured Omaha artists follow.

Art saw Yolanda Williams, aka Ms. Yo, through an abusive childhood and early adulthood. Today, this accomplished single mom studying for her master’s in leadership still uses art as “therapy.”

Of her intuitive, self-reflexive approach, she said, “I get consumed with the emotion in the piece of work. When I’m painting I’m talking through my problems, I’m talking through my past. Every paint stroke for me is, OK, this happened, how do I deal with this?’I want every single thing to be based on what I’m going through. When I look at my artwork from when I first started to now I can chart where I was in my life.”

With “Enojado” (Spanish for angry) she flung paint on canvas to release the primal rage she endured with the death of her father and a bad breakup. “Serene” pictures a poised woman standing her ground, sure of herself. It represents self-affirmation. Said Williams, “I love who I am — as an artist, as a parent, as a professional, as a community leader.” “Ra” is her meditation on life, mood, energy, faith and her affinity for the warm orange glow of sun and spirit.

Williams mentors school kids through her North Omaha Youth Art and Culture Program. She also writes and performs music.

Gabrielle Gaines Liwaru, aka G. D’Ebony, infuses threads from her life — family, multiculturalism, social connectivity — in her work, which incorporates found objects.

“Tribute to Lila” is an acrylic portrait executed on an old projector screen she salvaged. The subject is her grandma Lila Gaines, “a pillar” for several generations of South Chicago family and community. Working from an old black and white image, Liwaru’s choice of gray, black and white for the skin palette and regal purple for the backdrop imbues the work with sweet nostalgia.

The mixed media “Human Frailty and Salvation: The Wheat Perspective” ruminates on the fragility, interconnectedness and renewability of sustainable resources, human and otherwise. “The Thaw” is a watercolor/mixed media ode to the rite of spring, as the frozen winter gives way to the free flow of life again. “I Am, I Was, I Shall Be” poignantly renders the dimensions of a young girl on the path to maturity.

Liwaru is an Omaha Public Schools art teacher. She and husband Sharif Liwaru are African Culture Connection board members.

Gerard Pefung, from touristinmyhometown.blogspot.com, ©photo by Abby Jones

The dreamlike imagery of 20-something Cameroon native Gerard Tchofor Pefung variously pays homage to the tribal culture of his homeland and to the urban environs of his adopted country. Vibrant color schemes, kinetic shapes and familiar rituals celebrate life. In “Farm Watchman” a villager’s thoughts commingle with the flame and smoke of a fire. In “Music Festival,” a saxophonist holds sway over a jiving crowd. In each, a conjuring and communion occurs. There’s a deep spiritual fervor and electric immediacy in the work.

Though often starting from a sketch, he said “when I go to put it on the canvas I just let the canvas be itself until the work is complete. I’m not in control of what it’s going to be. Sometimes I’m guided by personal life experience, or by music, or just by the aura that surrounds me.” He works in acrylic and mixed media but mostly spray paints. Pefung, who has a Hot Shops studio, does diversion work with kids to channel them from destructive graffiti to positive modes of expression. Part of the proceeds from sales of his art go to his foundation that supports young people in West Africa.

DeJuan Cribbs, whose day job is at Metropolitan Area Transit, produces “digital paintings” entirely on his home computer, working from found images or from memory. Trained in fine art and graphic design, he melds traditional and nontraditional styles. Many of his images, such as “Native Omaha Legends,” salute a gallery of hometown heroes, including Malcolm X, Ernie Chambers and Mildred Brown. “Native Omaha Days” is a shout out to the biennial heritage event and the family reunions it spawns.

Some of his graphic design prints are abstract but most are figurative, including straight up portraits, caricatures, anime-like imagery, poster art-inspired work and more fine art-like studies. When he uses color it pops with an intensity and richness that comes from deft layering. His non-color work has an engaging older aesthetic to it.

Besides loving black culture, Cribbs said he wants his celebrations of high achieving blacks to show youngbloods the possibilities for success. He hopes to produce a coloring book of black Omaha legends and a digital graphic novel set in urban Omaha.

Other works of note in the show, which continues through May 22, include: Wanda Ewing’s whimsical “Black Catalogue” embrace of ebony women; Sebron Kendrick’s funkadylic religious inconography; Bob Duncan’s stark black and white photos; Jason Fischer’s gangsta rap Pop photo art; and Tina Tibbs’ sublimely textured digital photo collages.

The LJAC is at 2510 No. 24th St. Call 502-5291 for hours. Visit lovesjazzartcenter.org.

Related articles

- Soon Come: Neville Murray’s Passion for the Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its Role in Rebirthing North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Rich Music History Long Untold is Revealed and Celebrated at the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Miss Leola Says Goodbye (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Art from the Streets

I am not an art reviewer, but on occasion I am called upon to write about art, and in this case street art. My story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) discusses an exhibition from a couple years ago at the Loves Jazz & Arts Center that focused on Art from the Streets. The idea by then LJAC administrative director Michelle Troxclair, who is an artist herself, was to give artists who don’t often get the chance to show in gallery settings an opportunity to present some of their work. I was captivated by most of what I saw. At least one of the four artists featured in the show is a genuine celebrity – mixed martial arts figher Houston Alexander. This blog contains a profile I did on Alexander.

NME Crew Omaha, ©photo by Ginkz

Art from the Streets

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Urban Pop Funk might best describe Art from the Streets at Loves Jazz & Arts Center. Curated by LJAC administrative director Michelle Troxclair, the exhibition highlights the work of four Omaha artists whose subject matter, approach and mediums reflect art trends emanating from the inner city.

Troxclair organized the show to give props to artists of color whose self-taught airbrush-graffiti-graphic art remains off-the-grid. By presenting it in a gallery she’s validating this grassroots “street” art and implicitly slamming elitists who dismiss it.

To represent this movement, she selected artists with made reps for keeping it real: Graphic artist-digital photographer Jason Fischer, aka, Ginkz; airbrush artists Bruce Briggs and Spot; and graffiti artist/hip hop ambassador Houston Alexander.

The street-themed opening included sports cars out front inked with the latest graphic design detail work and Alexander on site creating two original graffitos. Together with the stylings of spoken word artists and the featured gents talking about their work, you had a street salon thing going on.

Fischer, whose business is called Surreal Media Lab, makes visceral, cerebral, suave images for magazines, CD covers, web sites. His shots of urban desolation bring an edgy, social critique. “Wasted” is one of several Fischer pics dealing with notions of refuse. He turns a littered gutter grate into a poetic indictment of excess and waste. Cutting through the black and white is a Coke can caught up in the wash, a glaring red symbol for capitalism’s disposable, discarded flotsam and jetsam.

He likes strong contrasts. “Cross the Line” pictures a crumpled yellow crime scene tape. It’s an interesting take on these garish plastic artifacts of violent, often fatal crime scenes. What do they symbolize once an investigation ends? Are they merely debris or markers commemorating tragedy? Or talisman warning of danger?

His “Razor’s Edge” series makes near abstractions of barbed wire. Troxclair told this reviewer the wire’s a security deterrent outside a youth detention center. That information lends the images deeper meaning. Yet no panel-guide text notes the context or artist intent for any exhibit works, an omission that hurts the show.

Briggs displays amazing control, precision and artistry in his expressive airbrush portraits, some mixed with acrylic. His pieces range from lush, glowing, colorful reveries of iconic pop stars (Beyonce, Christina Aguilera, P. Diddy Combs) to intense, moody, interpretive glimpses — in muted black-gray shadings — of Mos Def and Miles Davis. The mesmerizing Davis portrait, “Miles Away,” captures the jazz great in the throes of creative brainstorm, fingering his forehead as if a horn.

Spot’s equally impressive riffs on pop stars are by-turns whimsical (Barack Obama as a hipster in “Ba Roc-a-fella”) and mythic (Scarface’s Tony Montana in “The World is Mine”). His stunning portrait “Tupac” raises the late rapper to Sinatra Cool status in a swirl of joint smoke framing the artist in all his fly machismo splendor. The dense, abstract-like “Blue Pride” reveals another aspect of Spot’s vision.

Aptly, Troxclair incorporates tools of these artists’ trade, including cans of spray paint, along with apparel they’ve adorned.

Related articles

Soon Come: Neville Murray’s Passion for the Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its Role in Rebirthing North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Artist Bernard Stanley Hoyes Explores the Lamentations and Celebrations of Jamaican Revival Worship (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Miss Leola Says Goodbye (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Frederick Brown’s Journey Through Art is a Passage Across Form and a Passing On of Legacy (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

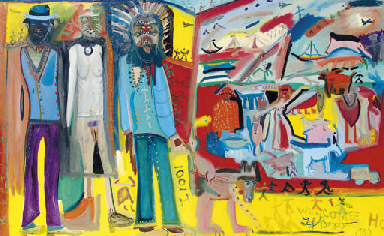

Artist Bernard Stanley Hoyes explores the lamentations and celebrations of Jamaican revival worship

This is one of many stories I have filed over the years related to the Loves Jazz & Arts Center in Omaha and various programs and exhibitions there. The subject of this story from a few years ago for The Reader (www.thereader.com) is the artist Bernard Stanley Hoyes and an exhibiiton of his work then showing at the LJAC. I am not an art reviewer, and thus the pieces I do from time to time about painters and sculptors and photographers are written more from a profile perspective than anything else. The center has presented many excellent exhibitions over the years that I have had the chance to see and cover, and in some cases I’ve interviewed the featured artists. Hoyes included. On this same blog you’ll find more LJAC art stories, including one on Frederick Brown and another on collector/explorer Kam-Ching Leung. You’ll also find stories about the center’s namesake, the late jazz musician Preston Love.

Sanctified Joy, ©Bernard Stanley Hoyes

Artist Bernard Stanley Hoyes explores the lamentations and celebrations of Jamaican revival worship

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Spiritual rapture is captured in artist Bernard Stanley Hoyes’s Revival Series. The exhibition Lamentations & Celebrations on display now through March 10 at the Loves Jazz & Arts Center features oil paintings, lithographs and etchings from the series, in which the Los Angeles-based artist explores the Revival worship services of his native Jamaica. He spent a week in Omaha doing school residencies.

Hoyes uses lustrous colors, seductive swirls and overwrought figures to evoke the “spirit at that moment of crescendo.” A cathartic moment when light, sound, music, rhythm and emotion reach a fever pitch of illumination or exaltation, said Hoyes, standing amid his iridescent work on the walls at the LJAC. When he began the series 25 years ago he chose a clean color palette and lyrical line pattern for his dynamic series. “In order for me to attain spirit and spirituality in my pictures,” he said, “my colors had to be pure. I went about by using colors without really muddling or mixing or tapering them. It’s like a sequence of motion and I’m capturing the motion at different points, but at the peak of each sequence.”

His images of incantation, reverie and ritual take place in outdoor, night time gatherings brightened by the glow of candle light and supernatural incandescence, where worshipers commune with their higher power in scenes at once solemn, joyful and eerie. There’s a power to the writhing figures caught in the spirit’s sway. The congregants worship en mass, buoyed by the communal beat of The Call.

He said, “The intention is to show where we gather our strength in all the trials and tribulations we have to endure. The strength comes from the commonality of our spiritual seeking. That’s one of the reasons I group the figures together and put them kind of like solid. They feel like one. You need all these bodies together to evoke the strength of what it takes to have a spiritual community.”

Flow with the Rhythm, ©Bernard Stanley Hoyes

His own experience of Revivalism, an amalgam of Afro-Caribbean–Christian traditions, goes back to his Jamaican youth. His great aunt was a priestess and elder whose backyard was the site for many services. He witnessed the songs, chants, dances, drums, processions, channeling of spirits, ecstatic revelations. The sacred, the mystical, the strange. It frightened and fascinated him. It was inevitable his art would explore these altered states and this mediation of ethereal and terrestrial.

Long after he left the island for America, he returned to Jamaica to observe with the eyes of a mature artist the Poccomanian and Zion strains of Revivalism. In rediscovering his roots, he found an intuitive grasp of it all. “I started to realize I had an innate sensibility about these ceremonies. I knew them,” he said. “It’s like knowing Mass. You know the consecutive ceremonies and where they go. You know the hymns. You can recognize what that special ritual and special consecration is all about without being told. As I started investigating it I saw there were some things being lost over the years. Certain sentiments in the religion. The way there was pressure to get a formal church building, where before worship was conducted in holy sites throughout the countryside or in certain blessed yards.”

He noted, too, the introduction of technology, by means of electrical amplification, to what were all acoustic rites. The changes, he said, gave him an urgency to document a rapidly disappearing heritage.

Bernard Stanley Hoyes

Hoyes views his art as an expression of the spirit and the spirit of art. As a veteran of inner city life in Kingston and L.A., he knows the soul killing poverty and crime people of color face. He creates work for nontraditional spaces as offerings of peace and unity amid troubled tribes and times, like his murals and his installations of altars and tables in riot-ravaged neighborhoods.

“We have to move beyond those manic rages,” he said through “spiritual cleansing. We can then start anew, afresh. That’s why I think we’ve seen the pervasive Born Again rituals-religions in America. People see the need for that cleansing. We have to look for the rituals where we find them. Until we do that we become captive to the oppressive nature of urban violence and all the other manic depressive things that go on in our community.”

Moonlight Spiritual S/N, ©Bernard Stanley Hoyes

Art, he said, can be part of “the healing process. It has to be about something that’s pervasive, that everybody can link their spirit to.” His Revival Series, informed by Jamaican and African American rites, is a resplendent multi-faith expression of praise and worship, call and response testifying. “It covers the whole gamut of Western Christianity with the African influence in it,” he said. Ever since his series struck a chord” a few years ago, his work has been collected by celebs like Oprah Winfrey, bringing thousands of dollars for originals and hundreds for prints. Why? “I think for the first time people with spiritual longing and spiritual connection see that part in it. They see the passion and the emotion of worship that is in the DNA of anybody that’s been to a Pentecostal or Baptist service.”

It’s about getting caught up in and overcome by the spirit. It’s what moved him when he began the series in a flourish of productivity. The spirit dictated “the style and motif and energy…the drive. One painting would beget the other — suggest the idea for the next,” he said, until he’d done 40 paintings in five weeks. “While I’m painting it becomes unconscious. It’s a classic inspired-work. That’s what it is.” He’s quit the series, but has always returned to it, finding the “inexhaustible” subject lends itself to “variations on a theme ” It numbers 500 to 600 works now. He means to retire the series with this exhibit, but suspects he’ll be drawn back to it again.

The LJAC, 2510 North 24th Street, is open Tuesday through Saturday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Call 502-5315 or visit www.lovesjazzartcenter.org for more details.

Related articles

- Frederick Brown’s Journey Through Art is a Passage Across Form and a Passing On of Legacy (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Soon Come: Neville Murray’s passion for Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its role in rebirthing North Omaha

The Loves Jazz & Arts Center in North Omaha is a symbol for the transition point that this largely African-American area is poised at – as decades of neglect are about to be impacted by a spate of major redevelopment. LJAC and some projects directly to the south of it along North 24th Street represented steps in the right direction but since then little else has happened in the way of renewal. Development efforts farther south, east, and west had little or no carryover effect. The subject of this story however is not so much the LJAC as it is its former director, Neville Murray, who was very much the director when I did this piece for The Reader (www.thereader.com) about three years ago. Murray expressed, just as his successor does today, the hope that the center would serve as anchor and catalyst for a boom in new activity in the area. The center never really realized that goal, but it still could. Murray is a passionate man, artist, and arts administrator with an interesting perspective on things since he’s not from Omaha originally. Indeed, he’s a native Jamaican. But as he explains right at the top of my story, he identifies closely with the African-American experience here and he’s committed to making a difference in the Omaha African-American community – one that’s been waiting a long time for change. If it’s up to him, it will soon come.

Soon Come: Neville Murray’s passion for Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its role in rebirthing North Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Oriignally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

“I’m an artist, first and foremost. I think everything else is just kind of a reflection of the art,” said Neville Murray, director of the Loves Jazz & Arts Center (LJAC), 2510 North 24th Street in Omaha. He came to the States in 1975 from his native Jamaica on a track scholarship that saw him compete for the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He’s made America and Nebraska his second home, but it is the north Omaha African American community the center serves where his heart lies.

“I consider myself African-American,” he said. “North Omaha is such a tremendous culture. There’s so much talent and there’s so much need. If we can just inspire kids to become artists or to becomeinvolved in the arts or to realize the role the arts can play in their lives…

“We’re really trying to change the dynamic by bringing world class arts programming to north Omaha and to bring in art one would not ordinarily see. Art is a catalyst for change. We’ve seen it downtown. And we think this can be a catalyst for change in our community.”

During a recent interview in the center conference room, which doubles as a storage space with stacks of art works leaning against the walls, he alluded to the year-and-a-half-old LJAC as trying to separate itself from “other organizations in the community” that have failed. The center’s “state of the art facility” is a big start. Another is his long track record as an administrator with the Nebraska Arts Council (NAC), where he worked prior to opening the center in 2005. Well-versed in grant writing and well-connected to the art world, he’s determined to avoid the pitfalls.

“We have to be at a different level in terms of our 501C3 meeting certain criteria with accountability (for programs and grants) and ownership of collections,” he said. “We have to set high standards. For me it’s critical we operate at a high level because of the history of some things.” When asked if he meant the troubled Great Plains Black History Museum a block to the east, he confirmed he did. He said that other venue’s long-standing problems of unarchived materials, unrealized repairs, unpolitic moves and unanswered questions stem from ineffective governance.

“It can’t be a hand-picked board. It needs to be a real board,” he said. “We have a great, pro-active, eight-member board.” The LJAC also has ongoing Peter Kiewit Foundation support. Even with that the center operates on the margin, with revenues coming chiefly from rental fees and grants rather than its light walk-in traffic. Murray was a one-man band for months after his only staffer resigned, leaving him doing everything from curating exhibits to cleaning floors. A Kiewit grant’s made possible the hiring of a new assistant. Still, he acknowledges problems — from the phone not always being manned to the doors not always being open during normal visiting hours to inadequate marketing and membership campaigns.

“I wear many different hats. There’s only so much you can do. It’s frustrating,” he said. “That has been an issue, you bet. I think that’s just part of our growing pains. Hopefully, that will resolve itself at some point in time. I’m not going to be here forever, but I want to make sure I put in place processes that can ensure the success of this institution into the future.”

Another barrier the center faces is one of identity and image. Some assume its solely focused on the legacy of Preston Love or a venture of the late musicians’s family. Neither is true. Others think it’s primarily a performance space when in fact it’s an exhibition/education space. Still others confuse it as a social service site. None of it deters him. “Ultimately, the goal for this institution is to be one of just a handful of accredited African American arts institutions” in America, he said.

The center grew out of many discussions Murray engaged in with members of the African American community. “We’d been meeting for years with a variety of folks about the need for an institution such as this in north Omaha,” he said.

Murray got to know greater Nebraska and north Omaha in particular as the NAC’s first multicultural coordinator in the 1990s. His work today at the LJAC is a natural extension of how his personal journey as an artist and arts administrator evolved to embrace his own Jamaican identity, the wider African American experience and the need to create more recognition and opportunities for fellow artists of color.

“It enriched me so much being able to travel all over Nebraska and work with indigenous folks to promote the arts,” he said. “To be able to work with different cultures, Latino and American Indian cultures, really inspired me, not just as an artist but in terms of my awareness. I began to realize the arts play a critical role in cultural development. A culture without art is dead. Art is what makes us human.”

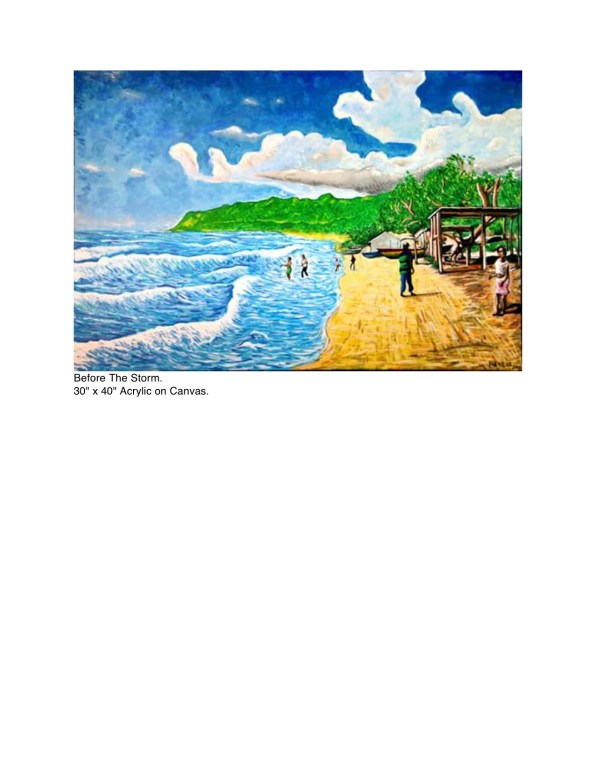

Besides, he fell in love with the state’s wide open spaces, variable topography, classic seasons and Northern Hemispheric light. “Nebraska’s such a beautiful state. If you drive straight from here to Colorado you don’t see it. But if you go just a few miles north of I-80 you’re in the Sand Hills and the vistas are just magnificent,” said Murray, whose paintings reflect his “love of nature” in iconic earth-tone images of the Great Plains or pastel seascapes of his tropical homeland.

He came to the NAC at a crucible time. His newly formed post was a response to protests over inequitable funding for artists of color. Inequity extended to museums/galleries, where works about and by black artists were absent, and to academia, where, he said, art textbooks at UNL failed to mention one of its own, grad Aaron Douglas, famed “illustrator of the Harlem Renaissance.”

Murray’s experience working with Nebraska’s Ponca population in their effort to be reinstated within the greater Ponca Tribe reflected his own sense of dislocation from his roots and the severing African Americans feel from their heritage.

“The Ponca had to relearn their traditions, so the NAC helped them get the grant funding to network back with the Southern Ponca down in Oklahoma to rediscover their dances and cultural traditions,” he said. “If as a tribe you’re cut off you lose a sense of your identity. I can relate to that because there was a period in my life when I can say I was kind of embarrassed at some of my rural upbringing. My grandmother used to walk five miles to market. People come from all over up in the mountains and bring their wares. Colors everywhere. Fruits of every ilk. Wonderful old stories. It took me a while to really appreciate all that. Now I look at it as a treasure and something we’re losing rapidly in the islands, I might add.”

“As black folks we’ve lost a sense of our identity. We’re confused. We don’t understand a lot of our traditions, even what tribes we come from. All of that was lost with slavery. Slavery’s had such a critical roles in our lives. It’s almost like we’re brand new,” he said. “Our whole life is a search, a journey for identity.”

Today, there’s more emphasis on black heritage and black art. “I think there’s much greater appreciation for art and artistic expression,” he said. “It’s not unusual to see artists of color in Art News now or other major art publications.”

Despite inroads, the place black artists hold in their own community and in the wider sphere of life is a work in progress. “It seems as black artists we’re always trying to validate ourselves. A few will come through. The flavor of the day, so to speak,” he said. “But as artists of color we we’re so often stigmatized. We have to get beyond that and recognize our art as an expression of our culture. We have a tendency in our community to look at arts as only recreation or extracurricular.”

His own ground breaking path reflects the possibilities for artists of color today. “I’ve kind of been doing a lot of things that hadn’t been done before,” he said. He was one of the first state multicultural coordinators in the nation. He pioneered the use of digital technology for Nebraska-curated shows. He organized the first comprehensive touring exhibit of contemporary Jamaican art with the 2000 Soon Come: The Art of Contemporary Jamaica. The project took him to parts of the island he’d never visited and introduced him to its diverse spectrum of artists.

He continues to celebrate art and to explore “what does it mean to be an artist of color?” at the LJAC, where he’s brought exhibits by renowned artists Frederick Brown, Faith Ringgold and Ibiyinka. In late November paintings from the Revival Series of noted artist Bernard Stanley Hoyes opens. The LJAC will publish its first catalogue for the show.

On display from time to time is work by local artists like Wanda Ewing, whose images deal with being a woman of color. It hosts regular art classes for adults/kids and occasional lectures/workshops. In keeping with its historic, symbol-laden location, the LJAC presents socially relevant programs, such as a History of Omaha Jazz panel held this year and the current Freedom Journey civil rights exhibit. All around the center, businesses flourished, streets teemed, marches proceeded, riots burned and hot jazz sessions played out. In a nod to political awareness, activist Angela Davis will appear there November 11.

Murray’s penchant for technology is evident in interactive stations/kiosks. An oral history project he’s doing with the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where he also studied, documents, in high def video, the lives/stories of older African American residents. The materials will inform a documentary about the history of black Omaha and its music heritage. The archived interviews will be available to scholars. He looks forward to curating a new exhibit around a group of photos from a local collector that record some of the earliest images of local African American life. A selection from the LJAC permanent collection displays photos of early African American scenes and moments from the career of namesake Preston Love.

Murray’s also in discussions for the LJAC to be an outreach center for New York’s Lincoln Center. “I’m really excited about that,” he said. “That gives us an opportunity to bring in some coeducational programming and performances.” It’s all about his trying to engage people with art in news ways. He said, “I would hope I bring a certain creativity to this position as an artist.”

He knows he and the center will be judged by their longevity. “You have to have a period of time when people can see if you’re going to be here for a while,” he said.” “I think folks feel good about we’re doing. I think people realize my heart is in the right place. I have a love of this community and the culture. It’s a huge challenge. It’s a big responsibility. But it’s been a wonderful experience.”

Related articles

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Overarching Plan for North Omaha Development Now in Place, Disinvested Community Hopeful Long Promised Change Follows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Lifetime Friends, Native Sons, Entrepreneurs Michael Green and Dick Davis Lead Efforts to Revive North Omaha and to Empower its Black Citizenry (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omowale Akintunde’s In-Your-Face Race Film for the New Millennium, ‘Wigger,’ Introduces America to a New Cinema Voice (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Negro Leagues Baseball Museum Exhibits on Display for the College World Series; In Bringing the Shows to Omaha the Great Plains Black History Museum Announces it’s Back (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Brief History of Omaha’s Civil Rights Struggle Distilled in Black and White By Photographer Rudy Smith (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha’s Malcolm X Memorial Foundation Comes into its Own, As the Nonprofit Eyes Grand Plans it Weighs How Much Support Exists to Realize Them (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Blacks of Distinction II (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Outward Bound Omaha Uses Experiential Education to Challenge and Inspire Youth (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Manifest Beauty: Christian Bro. William Woeger devotes his life to Church as artist and creative-cultural-liturgical expert

Omaha’s cultural scene is stronger thanks to Christian Brother William Woeger. He heads the Archdiocese of Omaha‘s Office for Divine Worship but is best known as founder and director of the Cathedral Arts Project based at St. Cecilia Cathedral. The project sponsors many performing and fine arts presentations throughout the year, including a flower festival that draws tens of thousands over a single weekend. He oversaw a major restoration project at the magnificent cathedral a few years ago. Adjacent to the cathedral is an impressive visitors-cultural center that was developed under his leadership. The following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) apepared while the restoration was still underway. Something I discovered about Woeger in doing the story is that in addition to being a highly respected liturgy expert and arts administrator, he is also a nationally renowned icon artist.

Triptych designed and painted by Bro. William Woeger

Manifest Beauty: Christian Bro. William Woeger devotes life to Church as artist and creative-cultural-liturgical expert

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

If not traveling to confer on a church renovation or to install one of his commissioned art works, national liturgical design consultant and icon painter Brother William Woeger can be found working the phone from his tidy office in the Archdiocese of Omaha chancery. From there, the fastidious Woeger juggles a busy schedule as head of the Office for Divine Worship and as executive director and founder of the popular Cathedral Arts Project. For good measure, the 54-year-old visionary — one of the early driving forces behind Omaha’s compassionate response to the AIDS epidemic — is director of liturgy at St. Cecilia Cathedral, whose $3 million restoration he is shepherding toward completion.

Gaze Upon My Soul

When the demands of his career and vocation get to be too much for the admittedly “driven” Woeger, a 36-year veteran of the Christian Brothers teaching order founded in 1864 by French cleric John Baptist de la Salle, he retreats to the solace of his painting. In keeping with tradition, Woeger’s iconic figures (mostly of Christ) are bathed in an aura of gold light suggestive of the Holy Spirit. His acrylic paint-on-wood works adorn churches in Omaha and around the nation. He recently completed and shipped the last in a set of 15 icons for a new church he helped design in Maryland. Word-of-mouth alone keeps him immersed in new projects. “I don’t advertise. I don’t submit drawings and designs. I don’t do committees,’ he said. Working from a basement studio, he enters a nearly transcendental meditative state amid the solitude and the golden reflected gaze of the icon he is rendering.

“When I am in the act of painting it actually creates a space in my life when I’m not tied into anything else. Aside from the sound of the furnace kicking-on, it’s a very contemplative experience,” he said. “And it’s very interactive in the sense that you begin manipulating the materials and then, at a certain moment — and sometimes it’s quite identifiable — the dynamics flip around and suddenly It’s doing it’s thing to you rather than you doing something to it, and it kind of finishes itself. That most often has to do with the face and the eyes — when the image starts looking back at you — which is at the heart of icons as a focus for prayer.

“The whole notion is very non-Western. The icon becomes a window, if you will, through which you contemplate the divine. Even if the image is not one of Christ but rather one of the saints, the whole metaphor with the gold hue in the background is that the source of the light is not the person — it’s beyond the person — and that is God being mediated through the figure in the painting, which is very incarnation-oriented.”

Bro. William Woeger

Upon This Rock

Born and raised in a south St. Louis German-Catholic family, Woeger felt an affinity for the arts and a calling to religious life as a youth and has combined these passions ever since. He entered the Christian Brothers at 18 and pronounced his perpetual vows at 25. While studying art, theology and philosophy in the ‘60s he developed a social conscience. He began a formal teaching career in 1967 when assigned to Omaha’s Rummel High (now Roncalli), whose art department he established. He later taught at the College of St. Mary. In 1981 he joined the archdiocesan staff, where his focus evolves “depending on what I see around me.”

Through his archdiocesan post he coordinates area liturgical celebrations. As a freelance liturgical designer he integrates music, art, ritual and architecture in churches nationwide. Striving to make each place of worship a “sermon without words,” he goes about “shaping the building around the liturgical action,” adding, “I see what I do as educational. I help clients take liturgical principles and use those as a stepping off point to create a house for the church and the community in which to worship and praise God.” Since each parish has its own distinct personality, he must balance unique cultural characteristics (ethnic, socioeconomic, charismatic, conservative, etc.) with Roman Catholic doctrine and tradition. “There can be a tension there, but it can be a creative thing,” he said.

His services range from all-encompassing design schemes to specific features. “Sometimes I’m involved from the very beginning all the way to the end, including designing the furniture, working with the architect, being a go-between with artists doing windows or sculptures and holding workshops with local liturgical ministers. It’s a helluva package. Other times, I just come in and help with the programming. End of story. Or, other times, I just design furniture or do an icon. It’s much easier to do a brand new building than it is a restoration because it’s no-holds-barred, at least conceptually. Sometimes I work on buildings that have a historic reference where we borrow the architecture vocabulary from another period. St. Vincent DePaul Church in Omaha is like that. It’s a contemporary building but definitely has a Gothic reference.”

Whatever the assignment, he tries making each church a metaphorical emblem of the Catholic faith and its people. “The definition of a symbol is something that points to a reality beyond itself, and church architecture has tremendous potential to do that,” he said. He feels much of modern church design “fails” in this regard by opting for flimsy rather than solid values. “I’m not knocking modern architecture in comparison with classical it-looks-like-a-church architecture. I’m talking about the whole American phenomenon of suburban architecture — the here-today-gone tomorrow strip-mall transitory approach to things as opposed to an approach that establishes a sense of place and an air of permanence. Especially if you buy into the idea church buildings are places where key moments in peoples’ lives are celebrated or sanctified, than the building-as-place becomes a touchstone for their memory and, so, the walls speak.”

Imbuing a church with indelible substance requires rigorous attention to detail. It starts with a philosophy. He said, “It’s about believing in things getting better as they get older. It’s about using quality materials, which isn’t necessarily the most expensive, but ones which the community feels invested in as ‘The best we have to put forward.’ It’s about the materials and design being appropriate. It’s about integrity and all these things bearing the mark of the maker and not appearing to be mass-produced but rather created for sacred purposes. And, in the final analysis, the building should be capable of bearing the weight of mystery. The weight of mystery is what gets you in touch with the presence of God and gives you the sense this is holy space. Using strip mall approaches doesn’t cut it. It can’t carry the profundity. This is God-stuff we’re talking about. It’s pretty heavy, and so there’s no room for the trite, the silly, the mundane, the pedestrian, the pop.”

Makeovers and New Directions

This same philosophy has underpinned the restoration of Omaha landmark St. Cecilia Cathedral, the Thomas Rogers Kimball-designed Spanish renaissance revival building begun in 1905 and completed in 1958. Except that, after Kimball’s death in 1934, the building was never quite finished and the famed Omaha architect’s plans never fully carried-out. Much of the Spanish flavor Kimball intended was ignored or altered. According to Woeger, Kimball’s design drew on the buoyant monastery palace complex of Spanish ruler Philip II. To recapture that model, Woeger selected Evergreene Painting Studios Inc. of New York, to execute the restoration, and Omaha architectural firm Bahr Vermeer Haecker to oversee the project.

Recent interior work done to the Cathedral, including extensive surface cleaning, the use of bold Iberian stencil patterns in the ceiling and nave, the addition of several large murals and various lighting enhancements, has appreciably brightened the building to provide a warmer, more vibrant, more visceral space in which one’s eyes invariably look up to the heavens. The idea was to create a vital ambience for public worship and celebration in which “the whole assembly is praying with one mind, one heart, one voice.” Woeger adds, “We had an opportunity to bring a much more exuberant Spanish renaissance style feeling to the interior finishes. Now, you have the sense the building is bigger and higher. It definitely evokes wonder and awe, and that architecture’s supposed to do that. Now, you can just watch people look up when they walk in. They didn’t use to do that because you really couldn’t quite take it all in it was so dark.”

Making the Cathedral an inspirational community gathering place is something Woeger had in mind when starting Cathedral Arts Project, an autonomous presenting organization sponsoring concerts, art exhibits and an annual flower show. His other impulse was putting St. Cecilia’s squarely in-line with the historic mission of cathedrals as a center of the humanities. “All of the spiritual reality that building stands for is an appropriate context for that which is spiritual about the arts,” he said. “It broadens the scope of the people who enter the life of the Cathedral. And, historically, cathedrals were the center of learning, the center of the arts, the center of humanity, the center of theology and spirituality.”

For Woeger, an “off-the-charts control person” who lost his father at age 9, the AIDS crisis presented a special challenge. “I spent a lot of time with people while they were dying and early on it was sort of making me crazy. I had to learn I couldn’t do anything about this. That the best thing I could do was simply be there for them.”

With the death-sentence urgency of the AIDS crisis largely passed and the Cathedral restoration drawing to a close, Woeger is looking for new challenges. “I’m the kind of person who reinvents himself about every six to eight years. I have to have some new stimuli in order to keep my creative juices flowing. It doesn’t have to be a radical change, but some kind of shift so that things sort of come apart and come back together again in a new configuration.”

Not surprisingly, his renewed focus is on upcoming projects at the Cathedral. First, life-sized statues (of saints) carved in Italy will be installed on exterior niches perched above the main entrance and a side entrance. The niches have sat empty the entire life of the Cathedral. Next, an ambitious organ restoration is on tap. And, once funds are secured, work will begin on a visitors/cultural center that will tell the story of the Cathedral and the legacy of Kimball in a museum to be housed in the former Cathedral High School building. Through such efforts he hopes the Cathedral remains a beacon for generations to come.

Related articles

- Omaha Address by Cuban Archbishop Jaime Ortega Sounds Hopeful Message that Repression in Cuba is Lifting (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Change is Gonna Come, the GBT Academy in Omaha Undergoes Revival in the Wake of Fire (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Nancy Kirk: Arts Maven, Author, Communicator, Entrepreneur, Interfaith Champion (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Photographer Larry Ferguson’s work is meditation on the nature of views and viewing

Larry Ferguson is one of the most collected and published fine art photographers in the Midwest. I have long been aware of the artist and his work, yet it was only witinh the last couple years he became a subject for this writer. I suspect I will be writing more about him in the years to come. This article for The Reader (www.thereader.com) appeared in conjunction with an exhibition he had at Creighton University. The black and white works in the show were drawn from various series he has done over the years depictiing the views afforded by rooms he stayed in and various touchstone places he’s visited in his many travels. Like many photographers I’ve met over the years, he maintains a very cool studio space.

Photographer Larry Ferguson’s work is meditation on the nature of views and viewing

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Photographer Larry Ferguson’s lush black and white imagery displays a mastery of technique and composition. But it’s not so much the work’s subject or execution as the evocative subtext bound up in it that is most arresting.

His new exhibition at Creighton University’s Lied Art Gallery, The View From My Room, is drawn from pictures he’s made of scenes outside the many rooms he’s inhabited over 30 years. The rooms, located in Nebraska, other parts of the U.S. and the far corners of the globe, offer a road map of sorts for the Omaha artist’s journey through life and craft. Aside from a few landscape and cityscape images, nothing dramatic or sumptuous is revealed, but rather the prosaic, mundane fixtures and rhythms of life as it proceeds around us. That’s the point.

Ferguson shows the holy ordinary of moments and places, some he has personal ties to and others he merely intersects with, but all of which express deep stirrings in him. It is, he said, “a travelogue through my emotional life.”