Archive

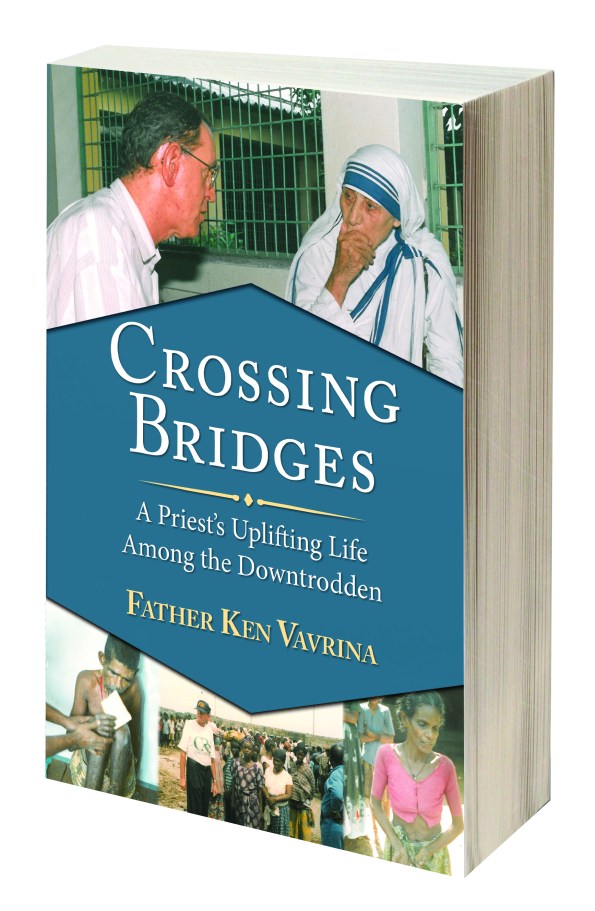

The cover for my new book with Father Ken Vavrina, “Crossing Bridges, A Priest’s Uplifiting Life Among the Downtrodden”

The cover for my new book with Father Ken Vavrina-

“Crossing Bridges, A Priest’s Uplifiting Life Among the Downtrodden”

Father Ken served diverse populations in need in America and in developing nations. His overseas work brought him in close relationship with Mother Teresa.

Look for future posts about where you can get your copies. All proceeds will be donated to Catholic organizations.

Coming Soon: A new book I wrote with Father Ken Vavrina, “Crossing Bridges,” the story of this beloved Omaha priest’s uplifitng life among the downtrodden

COMING SOON A new book I wrote with Father Ken Vavrina-

“Crossing Bridges”

The story of this beloved Omaha priest’s uplifitng life among the downtrodden.

Look for future posts about where you can get your copies. All proceeds will be donated to Catholic organizations.

-

-

Ledia Bedia Can not wait!

-

George M. Herriott Great subject. Looking forward to a great read.

-

SK Williams Author Will watch for it!! smile emoticon

-

Monica Cooper-Hubbert Oh My Goodness! He is one of my favorites! Love him to pieces. Renewed my parents 50th anniversary wedding vows. smile emoticon♡♡♡

-

Melanie Advancement He has had quite the life. That should be an awesome story!

CIVIL RIGHTS: STANDING UP FOR WHAT’S RIGHT TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE

This is an excerpt from one of two iBooks I authored for the Making Invisible History Visible project through the Omaha Public Schools. It was part of a larger Nebraska Department of Education digial publishing initiative. Working with teachers and illustrators we looked at sspects of African-American history with local storylines. My two 3rd grade books deal with the Great Migration and Civil Rights. The excerpt here is from the Civil Rights: Standing Up for What’s Right to Make a Difference book that looks at the movement through the prism of the peaceful demonstrations that integrated the popular Omaha amusement attraction, Peony Park.

Each book is used in the classroom as a teaching aid. To get the full experience of the book you need to experience it on a device because there are many interactive elements built in.You can access the iBook version at:

http://www.education.ne.gov/nebooks/teacherauthors.html

You can download a PDF version at:

http://www.education.ne.gov/nebooks/ebooks/peony_park.pdf

You can access my post about the Great Migration book I did at:

https://leoadambiga.com/?s=great+migration

NOTE: More Great Migration stories can be found on my blog.

Here is some background on the project I participated in:

During the summer of 2013, eight Omaha Public Schools teachers each developed an iBook on a topic of Omaha and Nebraska history as it relates to African American History. The four 3rd grade books are: Then and Now: A Look at People in Your Neighborhood; Our City, Our Culture; Civil Rights: Standing Up for What’s Right to Make a Difference; and The Great Migration: Wherever People Move, Home is Where the Heart is. The four 4th grade books are: Legends of the Name: Buffalo Soldiers in Nebraska; African American Pioneers; Notable Nebraskans; and WWII: Double Victory. Each book was written by a local Omaha author, and illustrations were created by a local artist. Photographs, documents, and other artifacts included in the book were provided by local community members and through partnership with the Great Plains Black History Museum. These books provide supplemental information on the role of African Americans in Omaha and Nebraska history topics. It is important to integrate this material in order to expand students’ cultural understanding, and highlight all the historical figures that have built this state. Each book allows students to go beyond the content through analysis activities using photos, documents, and other artifacts.Through these iBooks, students will experience history and its connections to their own cultures and backgrounds.

CIVIL RIGHTS:

STANDING UP FOR WHAT’S RIGHT TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE

©AUTHOR: LEO ADAM BIGA

©ILLUSTRATOR: WESTON THOMSON

INTRODUCTION

Imagine wanting to go swimming on a hot summer’s day at a big public pool. You arrive there with the simple expectation of laying out in the sun and cooling off in the refreshing water. But when you show up at the front gate ready to enter the pool and have fun you are turned away because you are black.

Naturally, your feelings are hurt. You’re probably angry and confused. How unfair that you cannot go swimming where everyone else can just because of your skin color. “What can be done about this?” you wonder.

It may surprise you to know this actually happened in Omaha, Nebraska, and the young people who were denied admission decided to do something about it. Some of them were Omaha Public Schools students. In 1963, they organized protests that forced the swimming pool owners to let everyone swim there.

INJUSTICE

How were people’s civil rights violated at Peony Park?

There was a time in America when black people and other racial minorities were denied basic human rights because of the color of their skin. Racism and discrimination made life difficult for African Americans. Often, they had to use separate facilities, such as black- only water fountains, or take their meals in the back of restaurants. Even something as ordinary as a swimming pool could be off-limits. Segregation in all aspects of daily life emphasized that African Americans were not equal and this system could be enforced with violence. If a black person tried to take a sip of water at a fountain, eat at a counter reserved for whites, or sit in the front of a bus, they could be arrested or attacked.

The system of segregation in America was called “Jim Crow.” In the South, Jim Crow segregation laws severely restricted blacks from using public facilities. But these laws were in place all over the nation. These harsh measures were put in place after the end of slavery. Though African Americans were now citizens, Jim Crow laws made black people second-class citizens, denied opportunities open to everyone else.

African Americans experienced racial discrimination in Omaha. A popular amusement park that used to be here, Peony Park, did not let blacks use its big outdoor pool. Unfair practices like that sparked the civil rights movement. People of all races and ethnicities joined together to march and demonstrate against inequality. They advocated blacks be given equal rights in voting, housing, jobs, education, and recreation.

DOING THE RIGHT THING

Following World War II protestors with the De Porres Club in Omaha peacefully demonstrated against local businesses that refused to serve or hire blacks. Members of the De Porres Club included the people of Omaha’s African American community, college students from Creighton University, and more. They were active from about 1947 to the early 1960s.

In 1963, members of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) Youth Council, some still high school teenagers, decided to challenge Peony Park and its racist policies. “Activism was in its heyday, activism was alive and well. Every community of black folks around the country was involved in some initiative and that was the Omaha initiative,” said Youth Council Vice President Cathy Hughes. Though only 16 at the time, Hughes was a veteran civil rights worker. As a little girl she carried picket signs with her parents when they participated in De Porres Club protests.

The Youth Council decided to protest at Peony Park after one of their members, a young black woman, was turned away along with her little sister. “She was told she couldn’t get into the pool,” recalled Archie Godfrey, the then-18-year-old Youth Council President. “It happened the same day we were having a meeting. She came to the meeting like she always did and said, ‘Guess what happened to me?’ And here was an issue that paralleled what was going on nationally.’ What do we do? All we knew is our member got rejected from Peony Park and we were going to make it right, and that’s how that thing got started.”

Godfrey and his peers closely monitored the civil rights movement and saw an opportunity to do here what was being done in Birmingham and Selma, Alabama, where Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and others were waging nonviolent social actions. Omaha Youth Council members had trained in nonviolent protest methods at NAACP regional events. Godfrey said, “We decided, ‘Well, let’s do what they taught us. We’ll test it.'” And they did.

STAGING THE PROTEST

Media played an important role in documenting the protests

The Youth Council activists came up with a plan for their protest. First, members tried to gain admission to the pool. Each time they were told it was full, even though whites were let in. Members next removed the ignition keys from their cars to block the entrance and exit. “That was the beginning of the demonstration,” said Godfrey. “We were nonviolent, we didn’t go out and shout and scream at them, we didn’t throw bricks, we didn’t spit, we didn’t do anything but demonstrate for the next two weeks.” Protesters also made sure the media was present to document their activities.

The group sang freedom songs to relieve the tension from counter- protestors, who were opposed to the civil rights movement. The Youth Council was aware things could turn violent as they did down South. “One of the reasons why we sung is because of how stressful and explosive a situation like that could be,” said Godfrey. “The singing of the civil rights songs as a group was like a medicine that kept us bound and understanding we were not alone, that there was unity. By singing to the top of our voices ‘We Shall Overcome,’ we didn’t hear the words that came from across the street from people calling us nasty names.”

He said the human chain they formed with clasped arms outside the front gate was only as strong as its weakest link. They needed solidarity to keep their cool. “If one of us had lost self control and got mad and went across the street and hit one of the those kids all hell would have broke out and it would have killed everything,” Godfrey observed. Cathy Hughes said all their training paid off. “We were disciplined, we were strategic.” No violence ever erupted. No arrests were made.

WINNING THE FIGHT

For a time the Malec family that owned and operated the park resisted making any changes. But after losing business, being challenged with lawsuits, and getting negative publicity, they opened the pool to everyone. The youth protestors won.

The success of the demonstration raised interest in the Youth Council. “We went from a few dozen members to 300 members that summer,” Godfrey said, “because of the attention, the excitement and people pent up wanting to do something like people were doing all over the country. We jumped on everything that was wrong that summer.” He said the Council staged protests at restaurants and recreation sites. “Each one opened its doors after we started or even threatened to demonstrate, that’s how effective it was.”

The events of that summer 50 years ago helped shape Godfrey. The lesson that youth can change things for the better has stayed with him. “I’ve been an activist and politically involved all the rest of my life,” he said. Cathy Hughes said the experience “instilled in me a certain level of fearlessness and purpose and accomplishment that I carried with me for the rest of my life,” adding, “It taught me the lesson that there’s power in unity.” She has never hesitated to speak out against injustice since then.

Demonstrations like these helped push Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which put into place many safeguards to prevent discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity. Today, people of any color or background can go anywhere they choose. That freedom, however, was hard earned by people like Archie Godfrey and Cathy Hughes who stood up to speak out against wrong.

ACTIVITIES AND QUESTIONS

ACT IT OUT

1.Describe how the Youth Council activists staged their protest of Peony Park.

2.How would you feel if you were told you couldn’t do something like go to a park or go inside your favorite store? What would you do about it?

3.Peony Park is only one example of a place where segregation occurred. Find other examples of segregation. Where did it happen? Who was involved? When did it happen? What did people do to end this segregation?

DESIGN A MONUMENT

You will design a monument that will recognize the accomplishments of the individuals who helped to desegregate Peony Park. Included with your design should be some words telling people what your monument represents.

QUESTIONS

1. WHY DID PEONY PARK WANT TO KEEP AFRICAN AMERICANS OUT?

2. WHY DID THE LIFEGUARD THINK THIS WOULD BACKFIRE?

3. THIS LIFEGUARD RISKED LOSING HIS JOB FOR SOMETHING HE BELIEVED. DO YOU THINK YOU WOULD DO THE SAME IN HIS POSITION? WHY OR WHY NOT?

4. THIS ARTICLE USES THE WORD “HYSTERICAL.” WHAT DOES IT MEAN? WHY IS FEAR OF AN INTEGRATED POOL CALLED “HYSTERICAL”? USE IT IN A SENTENCE.

MEET THE AUTHOR

Leo Adam Biga is an Omaha-based author- journalist-blogger best known for his cultural writing-reporting about people, their passions and their magnificent obsessions. His book Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film is the first comprehensive treatment of the Oscar-winning filmmaker. Biga’s peers have recognized his work at the local, state and national levels. To sample more of his writing visit, leoadambiga.com or http://www.facebook.com/LeoAdamBiga

MEET THE ILLUSTRATOR

Weston Thomson is a multidisciplinary artist and non-profit arts organization director living in Omaha, Nebraska. His work ranges from graphite, ink, and acrylic illustrations to 3D printed sculptures.

A NOTE FROM THE TEACHER

My name is Russ Nelsen. I teach 3rd grade at Standing Bear Elementary. I enjoyed taking what the author and illustrator did and putting it into an iBook! Hopefully this book was educational and fun!

Civil rights veteran Tommie Wilson still fighting the good fight

Omaha’s had its share of social justice champions. They’ve come in all shapes and sizes, colors and styles. Tommie Wilson may not be the best known or the loudest or the flashiest, but she’s been a consistent soldier in the felds of doing the right thing and speaking out against bias. Her work as an educator, as president of the local NAACP chapter and more recently as a community liaison finds her walking the walk. Read my profile about her for The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Civil rights veteran Tommie Wilson still fighting the good fight

Retired public school educator lives by the creed separate is not equal

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Social justice champion Tommie Wilson experienced the civil rights movement as it happened. For her, the good fight has never stopped.

While president of the local NAACP she brought a lawsuit against then-Gov. Dave Heineman over redistricting legislation that would have re-segregated Omaha schools. As Community Liaison for Public Affairs at Metropolitan Community College she chairs a monthly Table Talk series discussing community issues close to her heart, especially reentry resources. A grandson did time in prison and his journey through the system motivates her to advocate for returning citizens.

“I’m interested in how we can help them to have sustainable, productive lives,” says Wilson, who often visits prisons. “You know what they call me in prison? Mommie Tommie.”

Giving people second chances is important to her. She headed up the in-school suspension program at Lewis and Clark Junior High and the Stay in School program at the Wesley House.

“It took the kids off the streets and gave them the support they needed to be able to go back into school to graduate with their classes.”

Though coming of age in segregated Nacogdoches, Texas, she got opportunities denied many blacks. As a musical prodigy with an operatic voice she performed for well-to-do audiences. She graduated high school at 15 and earned her music teaching degree from Texas Southern University at 20.

She knew well the contours of white privilege and the necessity for she and fellow blacks to overachieve in order to find anything ilke equal footing in a titled world.

Her education about racialized America began as a child. She heard great orators at NAACP meetings in the basements of black churches. She read the words of leading journalists and scholars in black newspapers. She listened to iconic jazz and blues singers whose styles she’d emulate vocalizing on the streets or during recess at school.

Through it all, she gained a dawning awareness of inequities and long overdue change in the works. She credits her black professors as “the most positive mentors in my life,” adding, “They actually made me who I am today. They told me to strive to do my best in all I do and to prove my worth. They challenged me to ‘be somebody.'”

She and her late husband Ozzie Wilson taught a dozen years in Texas, where they helped integrate the public school teaching ranks. When the Omaha Public Schools looked to integrate its own teaching corps in the 1960s, it recruited Southern black educators here. The Wilsons, who came in 1967 as “a package deal,” were among them.

The couple’s diversity efforts extended to the Keystone Neighborhood they integrated. Tommie didn’t like Omaha at first but warmed to it after getting involved in organizations, including Delta Sigma Theta sorority, charged with enhancing opportunities.

“I’ve never shied away from finding things that needed to be done. I’m a very outspoken and vocal person. I don’t have a problem expressing what I feel. If it’s right, it’s right. If it’s wrong, it’s wrong, I don’t care who it hurts. That’s my attitude.”

She was often asked to lend her singing voice to causes and programs, invariably performing sonatas and spirituals.

Much of her life’s work, she says, has tried to prove “separate is not equal.” “I’m a catalyst in the community. I try to motivate folks to do what they need to do.”

She feels the alarming rates of school drop-outs, violent incidents and STDs among inner city youth is best addressed through education.

“Education is the key. Children have to feel there’s love and care about them learning in the classroom. Teaching is more than the curriculum. It’s about getting a rapport with your kids, letting them feel we’re in this together and there’s a purpose. It has to be a personal thing.”

Schools can’t do it alone, she says, “It’s got to start with church and home.”

She applauds the Empowerment Network’s efforts to jumpstart North Omaha revitalization.

“I love everything they’re trying to do because together we stand, divided we fall. If we can bring everybody together to start working with these ideas that’s beautiful.”

She’d like to see more financial backing for proven projects and programs making a difference in the lives of young people.

Since retiring as an educator, Wilson’s community focus has hardly waned. There was her four-year stint with the NAACP. She then approached Metro-president Randy Schmailzl to be a liaison with the North O community, where she saw a great disconnect between black residents and the college.

“We had students all around the Fort Omaha Campus who had never even stepped foot on campus.”

She feels Metro is “a best kept secret” for first generation college students,” adding, “For affordable tuition you can get all the training and skills needed to be successful and have a sustainable life.”

The veteran volunteer counts her 15 years as a United Way Loaned Executive one of her most satisfying experiences in helping nurture a city that’s become dear to her.

A7 79, Tommie Wilson finds satisfaction “being able to share my innermost passions, talking to people about their issues, trials and tribulations and teaching and guiding people to change their lives.”

What’s a good day for her?

“A good day is when I make a difference in the lives of others. Hardly a day goes by somebody doesn’t ask for advice.”

All Abide: Abide applies holistic approach to building community; Josh Dotzler now heads nonprofit started by his parents

North Omaha has seen its share of organizations over the years impose programs on the community to address some of the endemic problems facing that area’s most challenged neighborhoods, most of which have to do with poverty. As well intentioned as those organizations and programs may be, too often they end up as temorary or incomplete responses that come off as missionary projects designed to save the disadvantaged and misbegotten. Decades of this has resulted in a certain skepticsim, even cynicsm, and downright resentment among residents tired of saviors riding in to save the day, and then leaving when either the work is supposedly done or proves too daunting or the grant funding runs dry. To be fair, plenty of these do-gooders have stayed to fight the good fight and to make a postive difference, block by block, neighborhood by neighborhood. One of these is Abide, which also goes by Abide Omaha and which used to be called the Abide Network. Whatever its name, Abide has put down some serious roots in North Omaha over its 25 year history and the seeds of its community building work are just now beginning to blossom. Read about how Josh Dotzler, a son of Abide founders Ron and Twany Dotzler, is now leading the nonprofit in building Lighthouses in neighborhoods to provide hope, stability, fellowship, and community. Read my cover story about Abide now appearing in The Reader (http://www.thereader.com/).

NOTES: If you’re looking for a related story, then link to my 2013 piece on Apostle Vanessa Ward and the community block party she and her followers organize in a North Omaha neighborhood only a few blocks from where the Dotzlers and their Abide nonprofit operate: https://leoadambiga.wordpress.com/?s=vanessa+ward

Also, Ron and Twany Dotzler were one of the interracial couples I profile in a story I did at the start of 2014, Color Blind Love, that consistently gets dozens to hundreds of views a week: https://leoadambiga.wordpress.com/?s=color+blind+love

North’s Star: Gene Haynes builds legacy as education leader with Omaha Public Schools and North High School

In the 1960s the Omaha Public Schools was in need of African-American educators and not finding enough suitable college-educated candidates here the district looked to historically black colleges in the South. The irony of this is that many candidates from Omaha were denied teaching, coaching and administrative positions by a district that practiced blatant racism for much of its history. For decades OPS only hired a small number of black educators and then restricted them to predominantly black schools in the inner city. For years black public educators in Omaha were also restricted to elementary schools. It took a long time for OPS to dismantle those barriers and open the gates of fair employment and placement. One of the many educators recruited here from the South under those conditions was Gene Haynes, a native Mississipian who had actually followed his older brothers to Omaha and lived and worked here for a time before going back to Miss. to attend Rust College, a private historically black college. After he graduated from Rust he applied with and accepted an offer from OPS to teach and in 1967 he began what is now going on a 50-year career in the district. His first 18 years were at Omaha Technical High School and the last 31 have been at Omaha North High School, where he’s been principal since 2001. He’s helped lead a major turnaround at North, whose academic and athletic programs are doing great things. My New Horizons cover profile of Haynes follows.

North’s Star: Gene Haynes builds legacy as education leader with Omaha Public Schools and North High School

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the New Horixons

It is a marvel Omaha North High Magnet School pxrincipal Gene Haynes relates so well to students given how far removed his life experience is from theirs.

The 70 year-old Mississippi native came of age in a time and place unlike anything his students know. Haynes grew up in the grip of poverty and segregation in the post-World War II South. Yet he’s current and cool enough to accept either a handshake or a fist bump from students. He either calls them by name or by “brother man” or “sister girl” as he makes his presence known in the hallways, cafeteria and other common areas every school day.

“When you say their name they know you’re paying attention to them,” he says. “I take a lot of pride in going to the activities and seeing what the young people are doing and encouraging them to do their best.”

He’s such a fixture at North and in the community that he knows most students’ extended families. Omaha Public Schools superintendent Mark Evans says, “It makes a huge difference when the person telling you which direction to go knows not only your mom and dad but your aunt and uncle, your grandma and grandpa. I think it makes kids so responsive to Gene – much more so than most administrators.”

A message Haynes conveys to students is, “Do your best when no one is around.” When he’s around and sees students applying themselves, he says he knows “they want to be highlighted” and thus he singles them out. North students increasingly shine academically and athletically in the transformation he’s leading there.

“When you treat people right, good things happen,” he says. “I make it a point every day I come to this building to be outside greeting kids as they come in. They see this crusty old man. I’m not an office person. I have to do my paperwork on Saturdays or after school. When the kids are moving to and from class I’m out there to see what the kids are doing. You can’t stay in one place, you have to be able to move, and I do, which prompts kids to ask, ‘Are there two of you?’ I show up when they least expect it, not looking to catch them in anything but to give them that extra encouragement they need.

“We have a staff at North High School that cares about every student. The kids know that. I think that’s the key. You have to go in with a positive attitude. Every student is worth something. The young people you’re working with on a daily basis are going to be your future.”

For Haynes, there’s no conflict about his mission.

“The bottom line has been and always will be what’s best for young people, not personally for me. It’s to make a difference in the lives of young people that you come across in your path.”

It’s all about setting expectations.

“If you don’t expect anything from them they’re not going to give you anything but if you have those high expectations and you communicate that there’s no wiggle room. You need to know how to do that. I’ve kind of mellowed in my latter years. I was very aggressive (before). It goes back to my father who said, ‘You’ll catch more bees with honey than you will with a stick.'”

When he sees students acting out he handles it differently today than in the past, though he still bellows “Hit the bricks” to stragglers.

“If you reprimand or put them down in front of their peers you’re not going to get anywhere. The best thing to do is to approach them and treat them with all due respect.”

|

|||||

A credo he likes imparting is, “If you tell the truth you don’t have to worry about repeating it – it’s always going to be there.”

Haynes realizes students confront a lot these days between the pressure to have sex at an early age, the lure of drugs, the threat of bullying and the high incidence of teen depression and suicide. He’s aware many inner city students come from broken families and live in active gang areas where instability and fear rule.

“I think the biggest challenge we face is we don’t have enough time for the magnitude of issues students bring to school. It’s not about books, it’s about time and effort to convince these young people there’s a better way of dealing with issues.”

Rather than an extended school day or extended school year, he advocates schools and communities “provide the best opportunities” for students to develop.

He says parents are vital cogs in their children’s education and he actively solicits their participation.

“I pick up the phone and call them. If I need to go make a home visit I do that. We make them a part of the equation.”

He says “the trust level has improved” among North’s parent base. He

suspects some had bad experiences in school, making it incumbent on himself and his staff “to ease any apprehensions they feel,” adding, “There’s a support system in place to eliminate some of those concerns. We have a very strong PTSO (Parent Teacher Student Organization).”

Coming out of Miss. in an era when blacks were denied basic human and civil rights, he knows about hard times and perseverance. You don’t forge a 47-year career without overcoming odds.

Haynes grew up the youngest of four sons to a sharecropping father and homemaking mother in a country hamlet between Gholson and Preston, Miss. During the off-season his father drove a truck. Like his brothers and cousins he was delivered by his midwife grandmother.

“We came in with the blessings of my grandmother,” is how he puts it.

In that tight-knit community he says, “We kind of looked out after for each other.”

In the fully segregated South he attended all black schools that got “hand-me-down” textbooks from the white schools. As a child he walked miles to a one-room schoolhouse. At 9 he started taking a bus to school. By high school the routine found one bus picking up a white neighbor girl and another bus picking him up, the vehicles taking the youths to “separate and unequal schools.”

Blacks were treated as second-class citizens in every way.

“That was the way of life back in that time. Growing up in the Jim Crow South toughened your skin up.”

His parents never got as far as high school but they stressed education’s importance. The black teachers who taught at the choolhouse boarded with the Haynes family during the week. That close proximity to educators made “a big impact on me,” he says.

An influential figure in his life was a landed white man, Vardaman Vendevender, who took an interest in young Gene.

“This gentleman was very dear to my family. On the weekends I worked for him. I did things around his house. I had access to his tractor, truck, jeep. If he needed things from the store I was able to go into town and get them. He called me Gene Robert after my grandfather. He once said to me, ‘If you ever want to be successful you have to leave the state of Miss.’ Here was a white guy sharing that with me. That was a relationship I treasured for years. Up until he passed every time I would go back to Miss. I would visit him.”

Vendevender’s son, Jake, visited him at North a few years ago. “He said, ‘When I pulled up I couldn’t believe a young skinny kid from Miss. is the principal of this big high school. My father must have made an impression on you.’ That’s something that sticks with me even right now.” Haynes returned the favor, visiting Jake below the Mason-Dixon Line. “We talked about the olden days.”

Haynes was in high school, where he excelled in sports, when the civil rights movement came to Miss. and all hell broke loose. Native son James Meredith integrated “Ole Miss” in 1962 but only with the full force of the nation’s highest court and National Guard troops behind him.

“The most frightening thing in my life was riding the bus to school and having federal marshals on every corner. Tension ran very high.”

Every time activists or lawmakers threatened dismantling segregation, racist stakeholders in that apartheid system reacted violently. In 1964, his freshman year in college. a trio of Freedom Riders were killed. The deaths of the Mississippi Three further heightened fear.

Haynes says despite the obstacles and dangers he never despaired things wouldn’t improve. He believed in the power of education and in letting the truth shine through ignorance.

“I could see that because of my training and my teachers, who were always discussing how important it was to get an education. They embedded that into us – that education is a key for success.”

Blacks were also resourceful to find some kind of way through barriers to pursue their goals and dreams.

“We managed in spite of the opportunities denied us.”

Haynes says that as a college-bound African-American then his higher ed choices in the South were severely limited. In much of the region at that time blacks could not attend anything but historically black colleges. “When I was coming out of high school if you were black and you didn’t go to Jackson State, Alcorn, Mississippi Valley State, Rust College or one of the other private black schools, you couldn’t go.”

During the ’60s some challenged this exclusion but not without the federal government enforcing it. Even then there were serious, often ugly consequences. It would be some time before blacks were able to attend schools of their choice without incident.

Haynes was fortunate to have as a mentor a male high school biology teacher who also coached him in football.

“He was very instrumental in working with me from grade 10 on, preparing me for college. He had gone to Rust College in Holly Springs, Miss, and he was very instrumental in my attending Rust. I felt that was the opportunity for me to do the things I need to do.”

Before attending Rust, however, Haynes followed his brothers to Omaha, where the extended family put down roots during the Great Migration blacks made from the South to the North in search of a better life. Omaha’s booming meat packing plants and railroad operations drew many unskilled blacks and other minorities here.

“We had relatives here and they hooked my oldest brother, who came here in ’59. with a job. iI was a kind of networking that went on. He came here on a weekend and he went to work at the packinghouse on Monday. That started a chain of events,” says Haynes, whose other brothers followed. In 1963, Gene did, too. His brothers went to Miss. for his high school graduation and no sooner did the ceremony end then they took him back to Omaha with them.

“I left to the chagrin of my mom and dad. I was the baby and now the nest was empty. In 1964 my mother and father pulled up stakes and moved to Omaha. Mom couldn’t stand not being around her boys.”

Unlike his brothers, Gene didn’t work in the packinghouses. Instead, a relative got him on at the fancy Blackstone Hotel, with its distinctive exterior, ornate interior and popular Golden Spur and Orleans Room.

He returned to Miss. to attend Rust, majoring in social studies and economics.

“They provided me with a great education,” he says of his alma mater. The school also served as his introduction to his life partner. “I met a great lady whom I ended up marrying – my wife Annie. We graduated from Rust in 1967 and we got married in 1968.”

Haynes and his wife are the parents of one son, Jerel, and the grandparents of Caleb and Jacob.

Work-study and a scholarship put Haynes through college. He toiled in the dorms and athletic offices to pay his way in becoming his family’s first college graduate. Given the sway educators had in his life, he naturally looked at teaching as a career. Places like Omaha had a dearth of black college grads then, so OPS looked to historically black colleges for candidates. He joined other newly minted educators from the South as OPS hires, including Sam Crawford, Jim Freeman and Tom Harvey, all of whom enjoyed long careers like him.

“A large group of us that went to predominantly black schools came to Omaha to teach,” he says. “We’ve been very blessed because we have carved out a legacy that’s been great. We stuck together.”

Haynes didn’t intend staying in Omaha. When he started at OPS in 1967, at Omaha Technical High School. he came alone while Annie pursued teaching opportunities in Alabama and then Cleveland, Ohio.

“My plan was to teach here one year and go to Miami, where I also applied. I lived with my parents to save money. Forty-seven years later I’m still here and I haven’t saved any money yet,” he says, laughing.

After that first year in Omaha he went to Cleveland to court Annie.

“I convinced her Omaha was the place she needed to be.”

She got a job teaching 3rd grade at Lothrop Elementary. Annie ended up teaching 37-plus years in the district.

Haynes, who earned a master’s degree in education, administration supervision from the University of Nebraska at Omaha in 1974, taught and coached at Tech until the school closed in 1984. The massive Tech building is now the OPS headquarters, He was an assistant football coach when future University of Nebraska All-American and Heisman Trophy-winner Johnny Rodgers played for the school. During his tenure at Tech Haynes became the state’s first black head basketball coach. Breaking that new ground meant dealing with some racist coaches, officials and fans.

“With a predominantly black team we had some skewed eyes looking at us. I had to tell the kids, ‘You have to play above that because let’s face it if it’s close, you can forget it,'” says Haynes, referring to blatantly bad calls that went against his team and other minority-laden teams then at Omaha Central and Omaha South.

“I told the kids, ‘You have to be twice as good as your competition.’ And so we tried to prepare them for that.”

He says he instilled in his players the philosophy – “You give it your best. Winning is not everything, but a sincere effort is.” He says he still believes that today. “It’s not about wins and losses it’s about the success of the young people at the end of their high school term.”

He has fond memories of his time at Tech.

“I can think about so many young people I was fortunate enough to work with.”

One of those is Thomas Warren Sr., who became Omaha Police chief and is now president-CEO of the Urban League of Nebraska. Warren played basketball for Haynes and remembers his old coach as “a strict disciplinarian who had the respect of his players” because he went the extra mile for them. He sees Haynes doing the same thing today.

“For many of his players he was responsible for facilitating scholarship opportunities. For me individually, he drove me to Sioux City, Iowa in his personal vehicle for my recruitment visit to Morningside College, where I eventually attended. I have watched him spend countless hours serving the students of Omaha North High School and our community. He has been an advocate for at-risk students and I have never seen him give up on a kid. I consider Gene Haynes a friend, mentor and role model and I will always refer to him as ‘Coach.'”

Other students Haynes molded became entrepreneurs, lawyers and professionals in one field or another. He finds it ironic many of them are now retired while he’s still working.

“Doesn’t seem right,” he says, smiling.

He says “the passion the staff developed caring about individual students made all the difference in the world” at Tech “and that’s what I’ve attempted to do and incorporate here at North.” He and his staff work to create an environment where students “feel they can come and talk to us about their concerns and we’ll address the situation.”

When Tech closed Haynes became assistant principal and athletic director at McMillan Magnet School for a year before joining the North High staff in 1987. At North he served as assistant principal and athletic director for 14 years until assuming the principal post in 2001.

Since taking over at North, whose 4410 North 36th Street campus borders some of Omaha’s highest crime areas, he’s credited with leading a turnaround there. But he says the transformation began under predecessor Tom Harvey, who changed the school’s image. Starting in the 1980s North’s once proud reputation suffered under the strain of urban pressures that saw school dropouts and disruptive behaviors rise, along with test scores decline. Haynes says Harvey began the process of turning this wasteland into an oasis of success.

“Tom Harvey was a driving force behind the resurrection of North.”

|

|||||

The impoverished neighborhoods around North had fallen into a mire of drugs, gangs, violence, vacant homes and hopelessness but have rebounded with help from community building organizations like Abide.

North’s leaders, Haynes says, made a conscious effort to make the school an anchor and resource in a community hungering for something it could be proud of and call its own.

“Tom Harvey invited the alums and the Vikings of Distinction to turn North High School around. They talked about what would it take to change the perception. There used to be a fence around the place.

When you saw that fence you thought about the prison mentality and we had to change that. The fence came down and there was a trust factor then within the community that North is the place to be.”

Haynes has continued to enhance North’s community engagement.

“North High School is a key component of this community. We have opened up North for community events and activities. We found that when people in the community feel they are part of something your vandalism goes down. They feel they have ownership in this. The second Saturday of the month the Empowerment Network uses our facility. Every Sunday Bridge Church holds services here.”

He says if northeast Omaha is to realize its hoped-for revival then North High and its companion schools must be actors in it.

“If it’s going to change North High School and the Omaha Public Schools are going to be key players in turning things around. Right now I see we’re moving in the right direction.”

Haynes welcomes community partners.

John Backus, pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church in North Omaha, says, “When we approached him about ways to be helpful in his school he was ready with ideas, answers and the sort of willing spirit that accomplishes things. Gene Haynes is a capable leader and intensely interested in the well-being of his students.”

Perhaps the biggest sea change for North came when it was made a magnet center for STEM – science, technology, engineering and math.

“Haynes says, “We wanted the best and the brightest people to be a part of North High School – students and staff. We went out and brought in the best and the brightest and we will continue to do so.”

To accommodate this influx of students and new curriculum Haynes invited the entire North community of staff, students, alums and neighbors to weigh-in on a vision for a new addition. A group of students took the initiative and drew up the initial design for what became the 34,000 square foot, multi-million dollar Haddix Center.

“When the students are active I think it’s important you allow them to have input,” says Haynes. “It took 11 years from the time we started to plan until we were able to build. That was huge. We cherish the fact the alumni association and one gentleman, George Haddix, gave up $5 million. The district bought the project and supported it. We dedicated it in 2010. This is our fifth year in that facility.”

As a magnet center North draws students from around the metro. Haynes says one third of its students come from outside its attendance area. The school’s test scores have soared and the number of academic college scholarship awarded graduates has exploded. OPS superintendent Mark Evans says, “It’s a great success story and his leadership has made a difference there not only in the classrooms but in the extracurriculars. The principal sets the tone and is the leader of that culture and Gene Haynes is one of the best examples of that. When you say North High, you think Gene Haynes – that’s how much identification there is with him there.”

Evans adds that North’s success has a ripple effect on its student body and the surrounding community. “I think it’s huge. I think it sends a message of hope that we can and will succeed. We’ve got some young people who haven’t always thought they were going to be successful but because of North High and Gene Haynes they all believe they can be successful now and they are being successful.”

Haynes feels the STEM experience students receive there is preparing them for working living wage 21st century jobs that demand tech savvy employees. He’s confident as technology becomes ever more important that North’s on the cutting edge of utilizing it in the classroom. For example, some algebra classes are entirely taught on iPads. A new Samsung Smart School Solutions pilot program invites students to use a 75-inch touch interactive display and tablets to make stock market purchases, deliver tech-driven business presentations and get hands-on learning experiences with real life business partners.

“We have the best technology persons in Rich Molettiere and Tracy Sage,” Haynes says of North’s technology coordinators. “We really appreciate what they’ve been able to do. If someone tried to take them out of North High School, it’s on.”

North’s academic progress is matched by the success of its athletic programs. Until recently the school was known for its wrestling dominance, including multiple team and individual champions and at least one Olympic hopeful, Vikings grad RaVaughn Perkins. But more recently North’s football team has been the dominant force, winning back to back Class A state titles behind superstar running back Calvin Strong, a South Dakota commit. and Husker lineman recruit Michael Decker. The 2014 Vikings finished 13-0 and are widely considered one of the top teams in Nebraska prep football history.

|

||||

North has done all this without having a true home field to play on. Its football team plays at Northwest High’s Kinnick Stadium some four miles away. A proposal for North High to build a stadium of its own, right in the neighborhood, is being looked at. As with the earlier Haddix Center, North students did an initial design. Haynes and the school’s foundation are assessing if there’s enough support in the community for what would be a privately funded project costing millions of dollars.

“We want it be state of the art,” Haynes says.

He believes the stadium would be another “bright light for this community” and he says the facility would be available for use by nearby Skinner Magnet School and the Butler Gast YMCA.

Haynes keeps long hours at North, whose doors hardly ever seem to close for all the activity there. He says he goes home satisfied when “I see the kids leaving school with a smile on their face and a pat on the back from the principal and they acknowledge it.” He adds, “I have a post I go to at dismissal that borders the neighborhood. From my perch I can see kids coming and going and if anything’s going to happen from the outside that’s where it’s going to come from. The kids know that and I know that. That’s why I choose to go out there. As the kids walk by I acknowledge them and give them encouragement. That’s what I consider a most gratifying day.

“I try not take anything from school home, and vice versa.”

As for how much longer he’ll be doing this, he’s promised the class of 2017 he’ll walk with them at their graduation.

“That’s the plan – if my health stays good.”

That would make 50 years at OPS.

He won’t have any say in his successor but he and others will be keeping a close eye to make sure this sweet ride continues.

“I feel whoever comes in is going to do the right thing, and if not it’ll be a short tenure.”

Whoever follows him will have big shoes to fill. A measure of the high esteem he’s held in is the street named after him right outside the school. At the dedication for it last summer and on social media people offered tributes, calling him “humble, genuine, dedicated, a role model – commands true respect.” A grateful Haynes takes it all in stride, saying, “The Omaha community has been very gracious to me and my family and now I have to live up to it.”

Feeding the world, nourishing our neighbors, far and near: Howard G. Buffett Foundation and Omaha nonprofits take on hunger and food insecurity

Here is a collection of stories I wrote for the Winter 2014 issue of Metro Quarterly Magazine (http://www.spiritofomaha.com/) that focus on the theme of how responding to a starving world is within our reach. The stories explore the efforts of the Howard G. Buffett Foundation and of four Omaha nonprofits – Food Bank of the Heartland, Saving Grace Perishable Food Rescue, City Sprouts and No More Empty Pots – in taking on hunger and food insecurity through various programs and activities.

Feeding the world, nourishing our neighbors, far and near:

Howard G. Buffett Foundation and Omaha nonprofits take on hunger and food insecurity

Within Our Reach: A Starving World

40 Chances: Addressing Global Hunger

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in Metro Quarterly Magazine (http://www.spiritofomaha.com/)

Father-son team bearing famous name pen book that calls people to action

Howard G. and Howard W. Buffett want people to know they can make a difference in a hungry world

Giving became synonymous with the Buffett name when Omaha billionaire investor Warren Buffett gave part of his immense wealth to his adult children’s foundations and pledged the remainder to philanthropy in the event of his death. Thus, one of history’s largest personal fortunes is now closely aligned to myriad efforts that address pressing human needs around the world.

The Wizard of Omaha’s eldest son, Howard Graham Buffett, heads a foundation focused on improving the standard of living and quality of life for the world’s most impoverished, marginalized populations. Food security is among the foundation’s top priorities, not surprising given that its namesake chairman-CEO is a farmer with strong roots in his agriculture-rich native Nebraska. He’s also a staunch conservationist and an accomplished photographer.

A former Douglas County Commissioner now living in Decatur, Illinois, where he farms, Howard G. traveled to developing nations as a youth. His late mother, Susie, cultivated a social justice bent in him and his siblings. Those experiences helped shape the work of his Howard G. Buffett Foundation. His travels and the foundation’s work, told through the prism of experiences lived, relationships built and lessons learned, highlight his new book, 40 Chances: Finding Hope in a Hungry World.

He co-authored the bestseller with his son and former foundation executive director Howard Warren Buffett, who has extensive experience dealing with international and domestic issues. As a U.S. Department of Defense official he.oversaw ag-based economic stabilization-redevelopment programs in Iraq and Afghanistan. As a White House policy advisor he co-wrote the President’s cross-sector partnership strategy. The Columbia University lecturer also worked for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Nations.

Growing up he made many trips with his father to challenging places. Like his old man he is a farmer, too, with a spread near Tekamah.

Now or never

The book by this father-son team calls readers to take action and do something good for the world, even if it’s in your own backyard. The authors proffer principles for doing and giving and making a lasting impact with the limited chances you’re granted in a lifetime.

“If there’s an overriding thought it’s that anybody can do something. It doesn’t matter how big or small it is, it’s just doing something” that counts,” says Howard G. He adds, “Don’t be afraid to take risks. Even going down to your local food pantry to volunteer might be a risk for somebody. Make a long-term commitment – don’t just do it to see what it’s like. That message is to NGOs and foundations and everybody who works in any kind of philanthropic area.

“Figure it out, focus on it and then stick with it.”

The Buffetts hope their book gives people a sense of urgency to act.

“The truth is most of us just go through life,” Howard G. says. “We don’t think about the fact that by time we get out of college and get a little experience we’ve probably got 40 years to really make a positive impact. That’s our prime. Just do it right. We cant take stuff back and eventually we do run out of time. That’s what the title is about.”

“That gets to the core of what 40 Chances is – about having a limited number of opportunities to do the best job we can in our life,” Howard W. says. “And that can be being the best mother or father, being the best mentor, being the best resident of a neighborhood or community. It doesn’t matter what it is, it’s just that you seize those opportunities.”

Lessons learned

Much of the Buffetts’ work plays out overseas, where the West’s expectations or assumptions don’t hold much currency amid the developing world’s harsh realities. Howard G.’s seen many entities try to come up with First World solutions for Third World problems, but the metrics don’t always apply. The consequences of planting the wrong seed crop for a certain climate or soil in a vulnerable place like Eastern Congo, for example, can be disastrous.

“Everywhere we go and work in the world life is not predictable,” Howard G. says. “If you’re a small farmer struggling feed your family, if one thing goes wrong you can have a child die, so the consequences of what can happen are so significant and magnified.”

His foundation works in some tough environments, including Eastern Congo, Rwanda and Liberia, where food and water insecurity, poverty and conflict are constant threats.

He supports a research farm in South Africa, where the foundation does conservation work returning cheetahs to the wild and supporting anti-poaching measures. The farm grows cover crops, with the goal of making these crops available to several countries on the African continent. He makes a point of visiting wherever his foundation’s active, no matter how remote or unstable the site, in order to put his own eyes on a situation.

“Each trip leads to something,” he says. “I see something, I learn something. I would argue it is important to do it and I think other people need to do more of it. Anything I’ve ever learned that’s stuck with me has been in part because I’ve gone somewhere and experienced it. I think it has to do with my being a photographer. It makes you pay attention to the detailed scene of what’s happening. I absorb a lot of things by osmosis. As a photographer you have to be there to get the photograph. I think the same way with this, you have to be there.

“When you see a lot of pain and see death it’s very hard to deal with. I don’t care who you are, you internalize that somehow. What a camera allows you to do is to take pictures of that to show the world what’s happening. It gives you a whole new purpose of what you’re trying to do, so photography’s been a huge thing for me.”

This “journalist at heart” has published several books of photography featuring what he’s “seen and experienced” around the globe.

He’s learned the only way to truly appreciate the jeopardy people face is to go where they live and witness their peril.

“You can’t understand what people go through unless you see it for yourself. I can tell you what it’s like to go into a landfill where kids are living and dying because I’ve been to where people literally live in trash. When you walk in there your eyes burn and you can’t breathe. You have to experience that.”

Want is as near as our own backyard

The Buffetts say even if you can’t travel the world, opportunities to make a difference are as near as a local pantry or the Food Bank for the Heartland, where Howard W.’s volunteered. In the middle of America’s Breadbasket people face hunger and malnutrition daily.

“The numbers have grown so much in this country of people who are food insecure,” Howard G. says. “I think there are roughly 250,000 food insecure people in Neb. That’s right in the heart of America. You have to say to yourself, That’s not right, something’s totally wrong with that.”

Teaching people to grow their own food is part of building a secure, sustainable food culture. When Howard W. discovered all Omaha Public Schools’ designated career academies had been fulfilled except one – urban agriculture – he helped establish an Urban Ag and Natural Resources career academy at Bryan High School, where he also helped form a Future Farmers of America club. Both are thriving there.

“I’ve been able to mentor some of the students at Bryan and have an impact on their lives,” he says. “Those relationships and the gratification I get from being involved with very local things are extremely rewarding. It’s so enriching what takes place there.”

Father and son encourage folks to get out of their comfort zone and give time to worthy causes like these in their own community.

“I just think being there and showing up is so important,” Howard G. says. “You don’t have to have money to make a difference.”

He says America’s generosity and volunteerism stand it alone.

“Nobody volunteers like Americans. Americans are great volunteers, and they’re great volunteers right here in Omaha.”

Staying focused

If he’s learned anything, it’s that mitigating problems like chronic hunger, food insecurity and poor nutrition is gradual at best in places without America’s entrepreneurial-volunteer spirit.

“I’m very impatient and I’ve learned I have to be more patient. I’m a Type A personality, so I’m like, I’m going to go in there and figure it out when I get there. It doesn’t work that way. One of the things you learn is there’s no short-term fix or involvement. You have to be in this for the long haul. That changes how you do things. For us it means we have to stay very focused.”

He may not have the legendary focus of his father but he’s gotten better as he’s learned to say no and to accept he can’t do everything.

“I realized the consequences if I don’t stay focused – I get distracted, I’m wasting money, I’m not making impact. That’s just something I had to get better at. If I’m going to be focused and have impact I just have to say no to people, even very good friends. If I did all those things people come to me with I would get nothing done.”

His advice for organizations and individuals is the same.

“Figure out what you want to do and just do that and don’t get distracted, don’t get sidetracked, don’t try to save the world. If you’re going to try to save the world you’re going to save nobody. You’ve got to be focused. The more narrow you are the more impact you’ll have.”

Coming full circle

Doing the book brought many benefits.

“It helped the foundation itself gain additional focus and learn lessons from the past,” Howard W. says. “It allowed us to start honing in and narrowing down where we wanted to go from there, whether multi-year crop-based research on new varieties of corn or better ways to reduce soil erosion over a decade of no till with cover crops.”

Or building a new hydroelectric plant in Eastern Congo that will bring light to the masses to catalyze investment in agribusiness that will in turn create jobs for people whose only alternative is conflict. Or reducing poaching as a way to cut off funds (from the sale of elephant tusks and rhino horns) to rebels.

“For me personally this retrospective and introspective look was almost like going through a whole other undergraduate degree,” Howard W. says. “My dad and I hadn’t as much time to travel together the last couple years, so working on this book together was a new kind of journey of taking everything we had done together in person and then analyzing it. It’s been incredibly rewarding.”

The Howards were joined by family patriarch Warren, who wrote the book’s foreword, for the launch in New York City. The paperback version from Simon & Schuster is out this fall.

“That was fun. It brought us all together,” Howard G. says.

If there’s one thing Howard G. wants people to take away from the book, it’s for people to do something.

“I just feel like if we do these things it will make a difference. Even if it doesn’t make a difference, we tried and we might learn something from that failure. My dad talks about staying in your circle of confidence. I know what I’m good at, I know what I’m not good at, so I stick with that. But that’s a big enough circle for me to still step into things I’m not comfortable with.

“Like I tell young people, ‘Get uncomfortable, just go do some things that make you go, Holy crap.’ That’s what’s going to make you grow, that’s what’s going to make you want to do more because you’re going to gain some confidence. Some things might not work, but so what.”

Food Bank of the Heartland

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in Metro Quarterly Magazine (http://www.spiritofomaha.com/)

Distribution key to getting food to where it’s most needed

Collective effort to reduce food insecurity includes Food Bank

It’s no secret that in the land of plenty, a resource gap exists for many folks, including right here in the metro, The problem with poverty is not just low income, it’s lack of education and access. Want often translates into people experiencing hunger and inadequate nutrition.

Every night, a segment of poor Nebraskans goes hungry. An estimated 250,000 in the state are chronically food insecure, a dramatic increase since the 2007-2008 recession. Most of the affected adults are the working poor. One in five area children are at-risk of hunger.

The mosaic of helping agencies and initiatives addressing the issue includes food pantries. community gardens. healthy cooking classes and nutrition education. A key player in that mix is the Omaha-based Food Bank for the Heartland. Established in 1981, FBFH is one of only two food banks in the state along with the Lincoln Food Bank.

Scaling up

Until five years ago FBFH served just Omaha and Council Bluffs but it now covers most of the state, plus western Iowa, for a total of 93 counties and 75,000 square miles. In what’s been a transformation for an organization that depends almost entirely on donations and fundraisers, a completely new leadership team and staff came on board in 2009 to scale the operations up. That’s meant a new, expanded facility at 10525 J Street, a fleet of big trucks and a tech-driven warehouse order and delivery tracking system.

“We have online ordering for our customers just like Amazon that tells us what they want, when they want it and reserves it in inventory,” says president-CEO Susan Ogborn. “We have Roadnet, the UPS software, to track our trucks and to route them efficiently. We have bar coding in the warehouse so that everything is tied to an item number. It tells you when to pick and how many to pick.”

All of it’s needed to distribute the estimated 16 million pounds of food FBFH will distribute this fiscal year.

“We can’t do this without being as efficient and effective as possible. We monitor everything we do and how we do it.”

Volunteers are critical for sorting and repackaging pallets of food.

In its mode shift the Food Bank’s gone from “order taker to business seeker,” she says. “Before, we waited for people to come to us. Now, I have two full-time food sourcing professionals who do nothing but look out for food and work with the people who give it to us.”

The organization’s increased the number of retail and processing vendors it contracts with to provide food, much of it perishable meat, dairy and produce, from fewer than a dozen to more than 200. Procuring enough edible resources for its many food partners, who include pantries run by the Heart Ministry Center, Together and Heartland Hope Mission in Omaha, has “changed our entire business model completely,” Ogborn says, adding. “We are first and foremost a distribution center now. We’ve got five people on the road all the time in rural Nebraska. We’re an entirely different business.”

Heart Ministry Center director John Levy says, “The Food Bank plays an absolutely critical role in us being able to serve people in need. We can access a much wider selection of food by using Food Bank and also keep our costs much lower. By having a wider selection of food, people are more likely to come back to our Center because they had a good experience. Because we are able to get the food for free or drastically reduced prices, we have more money to spend on helping clients with their underlying problems.”

Ogborn and her staff all came to their jobs with no previous food banking experience, which she says has worked to their advantage.

“We don’t know what we can’t do, so we just we just try anything and don’t let anything stop us.”

Outside-the-box

Most satisfying to Ogborn, she says, is “finding some creative way to serve people we haven’t served before,” For example. identifying the rural poor in the Sand Hills region was proving difficult until she thought of an outside-the-box way to reach them.

“I sent out a letter to the sheriffs in those counties that said, ‘You know who the people are in your community that are in need, I don’t, how about I send you some food boxes and you give it to them when they need it?’ I didn’t know if I’d hear back or not. Well, the sheriffs in those counties, especially Nance and Merrick counties, are now distributing food on a regular basis. They’re supporting mobile pantries and we’ve got all kinds of services going on there.”

Closer to home, FBFH operates programs that provide meals to at-risk children after school, on weekends and during the summer through such youth-serving organizations as Completely Kids.

“Where we identify a gap where people aren’t being served by anybody else we will start a program.”

The effects of hunger and poor nutrition are far-reaching, especially on children’s health and school performance. Often hunger or malnourishment results when people can’t afford or find fresh, local food near them. Those living with food insecurity and residing in food deserts often don’t know what eating healthy entails and need to be taught how to source and cook things that don’t come out of a box.

Growing your own food is an option for some. But for most folks a food pantry or the SNAP (food stamps) program is more realistic. Not everyone knows about or chooses to use these remedial options. Ogborn says as many as a third of those eligible to receive SNAP benefits in Neb. fail to do so, often, she suspects, out of embarrassment.

She agrees with colleagues that mediating hunger in the Heartland requires a collaborative effort to make the needed collective impact.

“In the food banking world we have a saying – you can’t food bank your way out of hunger. And you absolutely can’t. There is enough food to feed everybody in America but how we get it and people connected is very challenging. It’s a distribution challenge process. It’s also an issue around nutrition education, cooking healthy meals.”

That’s why the Food Bank partners with ConAgra Foods Foundation, Walmart and other mega food processors and purveyors to get healthy food to where it’s needed. “We could not do what we do without them.” It’s why it partners, too, with the Hunger Free Heartland coalition and the Hunger Collaborative to do the same on a more intimate scale.

Hunger Collaborative shared services coordinator Craig Howell says FBFH not only provides nutritious food to pantries that clients might otherwise not access but supplies hot meats for children outside of school they might miss at home. He says it also assists eligible clients get signed up for SNAP. “The ability for us to make sustainable changes cannot happen without the work of the Food Bank.”

Another part of the answer is fast food giants and school cafeterias offering healthy alternatives. Ogborn says reaching people where they live with their habits will make a profound difference in their nutritional levels over time.

Ogborn says the ultimate goal is for all Nebraskans to be self-sufficient in terms of secure, sustainable access to food. “We’d love to put ourselves of business.” Until that day arrives, fundraisers are needed to help support its work. In Sept. a city-wide spaghetti feed garnered thousands of dollars. Proceeds from the ConAgra Foods Ice Skating Rink during the annual Holiday Lights Festival will go to the Food Bank. On March 12 FBFH’s big annual fundraising dinner will feature celebrity chef Geoffrey Zakarian at the Embassy Suites in La Vista.

Money, food, volunteers and vendors are what keep the Food Bank going. Visit http://www.FoodBankHeartland to get involved.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in Metro Quarterly Magazine (http://www.spiritofomaha.com/)

Community response to hunger fosters collaboration

Different approaches come together to make collective impact

Organizations working to make at-risk populations food secure agree more can be done collectively than alone to combat hunger. Omaha’s replete with efforts that feature collaboration and cross-pollination. Some players, such as Saving Grace Perishable Food Rescue or City Sprouts, have distinct niches. Others, such as No More Empty Pots, are more comprehensive in scope and thus all roads lead there.

One way or another, these organizations connect with coalitions like Hunger Free Heartland, a ConAgra Foods Foundation’s originated-initiative that’s evolved into the community-wide Child Hunger Ends Here-Omaha Plan. Members of the Hunger Collaborative – Food Bank for the Heartland and pantry operators Heart Ministry Center, Together and Heartland Hope Mission – collectively work to end food insecurity and to provide an array of human services.

New collaborations are always surfacing, including the Prospect Village Community Garden Program that finds City Sprouts, No More Empty and Big Garden, among others, promoting the benefits of engaged, cohesive neighborhoods through community gardening.

Three organizations among many making a difference in creating a secure, equitable food system are:

Saving Grace Perishable Food Rescue

If it takes a village to raise a child, then it takes a communal effort to feed one. Experts agree no one source can solve food insecurity, Instead, ending hunger takes multiple approaches. One is capturing excess food otherwise thrown away and giving it to hungry folks. That’s just what Saving Grace Perishable Food Rescue does.

Formed in late 2013 by Beth Ostdiek Smith, Saving Grace rescued more than 200,000 pounds of perishable food in its first 10 months of operation. Ostdiek says a pound of food equals one meal, meaning Saving Grace provided 200,000-plus meals to its recipient partners, who include nonprofits such as Table Grace, Heart Ministries and Open Door Mission that serve vulnerable youth, adults and families.

Smith, who’s long been concerned about the amount of food that gets wasted and the number of hungry people needing square meals, says she “found a niche that really wasn’t being fully addressed” in Omaha.

The response to her food rescue and delivery organization indicate’s she’s helping fill a gap.

“I can’t emphasize enough how excited our recipients are by what we’re bringing them. This is really healthy, nutritious food.”

Response from food vendors is equally positive.

“I think it’s because we’re offering this consistent, professional model that comes out to food vendors. We have refrigerated trucks and our drivers have food handling licenses. We keep it simple and seamless. We get food from here to there.”

Trader Joe’s, Akins Natural Foods, Greenberg Fruit and Attitude on Foods are a few of the biggest participating vendors.

“We just signed on CenturyLink Center’s Levy Restaurants, so we’re going to capture all the excess from the concessions and parties there.

QT has expressed interest in donating all the perishable excess from their convenience stores.”

She says she sells vendors on the give-away with a basic appeal. “Rather than throwing your excess food away in the trash we can rescue your food and get it to people that need it. It just makes sense. We like to say we’re feeding bellies rather than the landfills. It’s exciting to see how much people care and want to make this happen. We need to honor our donors who take and make time to donate.”

Part of Saving Grace’s mission is enhancing awareness and education on food waste and hunger. For example, the organization informs vendors and recipients it has the means to capture unsellable but still edible dairy, produce, proteins and grains that otherwise get thrown away.

“A unique thing we do is match the food to recipients’ needs because many times people have great hearts and take things down to food pantries the pantries can’t use. When we bring on a food recipient partner we interview them to see what their capacity is – whether they have refrigeration and freezers – how much they’re serving and what’s most in demand. Then we match our food to their needs.”

She wants to add more recipients but she says she won’t “until we get more food donors – I don’t want to make promises we can’t keep.” She says there are vast segments of the food industry ripe to be tapped, including corporate, school and hospital cafeterias, country clubs, caterers and arena-convention centers. She estimates more than 80 percent of perishable food goes uncaptured and therefore trashed. “There’s huge potential to procure more food,” she says.

Helping her with the logistics and food sourcing is Judy Rydberg, who brought 12 years experience with Waste Not Perishable Food Rescue and Delivery in Scottsdale, Arizona. Smith used that program as the model for her own. Smith feels she’s hitting a wave of interest in mitigating hunger. “I think we’re starting to see a movement, and if we can be a catalyst for the movement with our other food partners that would be a great thing.”

She also sees a need for more collaboration and communication so that food partners can identify how they best align. As for Saving Grace, she says, “what we need to have for this to be sustainable is more dollars and food donors,” adding, “We’re looking for Saving Grace Friends to help us get the word out, raise funds and open doors.

We’re just getting started. We’re a very small but mighty organization.”

Visit savinggracefoodrescue.org to see where you can make a difference.

City Sprouts

In 1995 City Sprouts began as a small community garden meant to bring harmony to the then-violence plagued Orchard Hill neighborhood. The nonprofit’s evolved into a one-and-half acre campus from 40th and Seward to 40th and Decatur. Its education center, community garden and urban farm have a mission to enhance food security, promote healthy lifestyles, employ at-risk youth and build community.

The land produces fresh vegetables and eight hens in a chicken coop produce eggs for use by area residents, many of whom tend plots in the community garden. Youth from challenged backgrounds learn horticulture and life lessons in addition to earning money working on the farm, which includes a hoop house that extends the growing season from early spring through late fall. The fruit and vegetables interns grow from seed to table are sold at an on-site farmer’s market. Classes and workshops by horticulture and other experts cover nutrition, canning, dehydrating, cooking and non-food topics. Events such as potlucks, discussions and seasonal celebrations invite area residents to engage with staff, volunteers and visitors.

“We are part of a larger movement locally and nationally trying to foster a connection with your food, with your neighborhood. Our work is supported by this great resurgence of people going back to gardening, knowing where their food comes from and eating more locally, more seasonally,” says City Sprouts director Roxanne Williams.

A turning point for City Sprouts came in 2005 when a vacant house at 4002 Seward Street was donated as its education center.

“Getting the house was a huge asset,” Williams says. “That is one of the things that has enabled us to grow our organization. It changed the whole direction of City Sprouts and made so many more things possible.”

The house allows the organization to be engaged with the neighborhood year-round through classes and programs held there.

In addition to the interns who grow on the urban farm, young children are introduced to gardening on campus. Next spring children from two neighborhood elementary schools, Franklin and Walnut Hill, will learn gardening and nutrition in programs City Sprouts is planning with them, including developing a school garden with Franklin staff and students.

With northeast Omaha considered a food desert because residents have limited access to fresh, local, nutritious food within walking distance, the garden and farm take center stage in good weather. Williams says City Sprouts is one of many players trying to improve food options there and in other underserved metro neighborhoods.

“It’s not one answer, it takes a village, it takes so many people working together. There’s lots of groups making a difference. I think we’re making inroads. But there’s always going to be a need.”

Community gardeners, ranging from entire families to single moms to senior retirees, grow on 45 raised beds surrounded by fruit trees and perennials. In exchange for a nominal fee gardeners are assigned a bed and provided plants, seeds, water, education and encouragement. Gardeners are responsible for maintaining their own beds.

Getting buy-in from neighbors is taking time, especially in an area with many rental properties and therefore much turnover. But there are growers who return every year. Several young professionals and students living in the area who also happen to be backyard farmers and foodies are regulars at the community-building events.

Williams, a master gardener who comes from an education and fundraising background, came on board three years ago as the nonprofit’s first full-time, year-round director.