Archive

Omaha native Steve Marantz looks back at city’s ’68 racial divide through prism of hoops in new book, “The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central”

Omaha native Steve Marantz looks back at city’s ’68 racial divide through prism of hoops in new book, “The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

America’s social fabric came asunder in 1968. Vietnam. Civil rights. Rock ‘n’ roll. Free love. Illegal drugs. Black power. Campus protests. Urban riots.

Omaha was a pressure cooker of racial tension. African-Americans demanded redress from poverty, discrimination, segregation, police misconduct.

Then, like now, Central High School was a cultural bridge by virtue of its downtown location — within a couple miles radius of ethnic enclaves: the Near Northside (black), Bagel (Jewish), Little Italy, Little Bohemia. A diverse student population has enriched the school’s high academic offerings.

Steve Marantz was a 16-year-old Central sophomore that pivotal year when a confluence of social-cultural-racial-political streams converged and a flood of emotions spilled out, forever changing those involved.

Marantz became a reporter for Kansas City and Boston papers. Busy with life and career, the ’68 events receded into memory. Then on a golf outing with classmates the conversation turned to that watershed and he knew he had to write about it.

“It just became so obvious there’s a story there and it needs to be told,” he says.

The result is his new book The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central: High School Basketball and the ’68 Racial Divide (University of Nebraska Press).

Speaking by phone from his home near Boston, Marantz says, “It appealed to me because of the elements in it that I think make for a good story — it had a compact time frame, there was a climatic event, and it had strong characters.” Besides, he says sports is a prime “vehicle for examining social issues.”

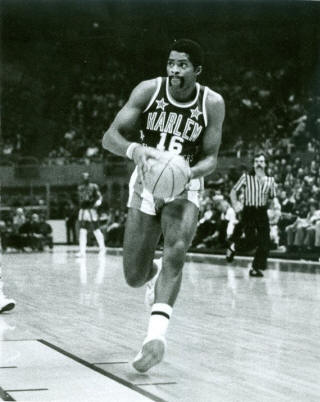

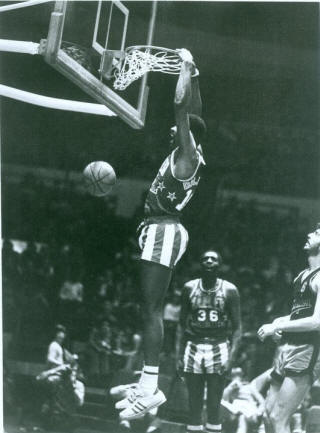

Conflict, baby. Caught up in the maelstrom was the fabulous ’68 Central basketball team, whose all-black starting five earned the sobriquet, The Rhythm Boys. Their enigmatic star, Dwaine Dillard, was a 6-7 big-time college hoops recruit. As if the stress of such expectations wasn’t enough, he lived on the edge.

At a time when it was taboo, he and some fellow blacks dated white girls at the school. Vikki Dollis was involved with Dillard’s teammate, Willie Frazier. In his book Marantz includes excerpts from a diary she kept. Marantz says her “genuine,” “honest,” angst-filled entries “opened a very personal window” that “changed the whole perspective” of events for him. “I just knew the vague outlines of it. The details didn’t really begin to emerge until I did the reporting.”

Functionally illiterate, Dillard barely got by in class. A product of a broken home, he had little adult supervision. Running the streets. he was an enigma easily swayed.

Things came to a head when the polarizing Alabama segregationist George Wallace came to speak at Omaha’s Civic Auditorium. Disturbances broke out, with fires set and windows broken along the Deuce Four (North 24th Street.) A young man caught looting was shot and killed by police.

Dillard became a lightning rod symbol for discontent when he was among a group of young men arrested for possession of rocks and incendiary materials. This was only days before the state tournament. Though quickly released and the charges dropped, he was branded a malcontent and worse.

White-black relations at Central grew strained, erupting into fights. Black students staged protests. Marantz says then-emerging community leader Ernie Chambers made his “loud…powerful…influential” voice heard.

The school’s aristocratic principal, J. Arthur Nelson, was befuddled by the generation gap that rejected authority. “I think change overtook him,” says Marantz. “He was of an earlier era, his moment had come and gone.”

Dillard was among the troublemakers and his coach, Warren Marquiss, suspended him for the first round tourney game. Security was extra tight in Lincoln, where predominantly black Omaha teams often got the shaft from white officials. In Marantz’s view the basketball court became a microcosm of what went on outside athletics, where “negative stereotypes” prevailed.

Central advanced to the semis without Dillard. With him back in the lineup the Eagles made it to the finals but lost to Lincoln Northeast. Another bitter disappointment. There was no violence, however.

The star-crossed Dillard went to play ball at Eastern Michigan but dropped out. He later made the Harlem Globetrotters and, briefly, the ABA. Marantz interviewed Dillard three weeks before his death. “I didn’t know he was that sick,” he says.

Marantz says he’s satisfied the book’s “touched a chord” with classmates by examining “one of those coming of age moments” that mark, even scar, lives.

An independent consultant for ESPN’s E: 60, he’s rhe author of the 2008 book Sorcery at Caesars about Sugar Ray Leonard‘s upset win over Marvin Hagler and is working on new a book about Fenway High School.

Marantz was recently back in Omaha to catch up with old Central classmates and to sign copies of Rhythm Boys at The Bookworm.

|

|

|

Related articles

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Big Bad Buddy Miles (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omowale Akintunde’s In-Your-Face Race Film for the New Millennium, ‘Wigger,’ Introduces America to a New Cinema Voice (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Charles Fairbanks, aka the One-Eyed Cat, makes Lucha Libre a way of life and a favorite film subject

When I read about filmmaker Charles Fairbanks for the first time last year I was immediately taken by his story: how a rural Nebraska student-athlete turned artist become enamored with and immersed in the world of Mexican professional wrestling known as Lucha Libre, which he’s made the subject of some of his short films. Then when I delved further into his story, by exploring his website and watching some of his work, I knew I had to write about him. We met last summer, when his disarmingly sweet personality and thoughtful responses made me immediately like him. The following story I wrote about Fairbanks and his work appeared just before this year’s Omaha Film Festival, where one of his Lucha Libre films, Irma, was shown. Fairbanks is a serious artist whose work may or may not ever find a wide audience but is certainly deserving of it. I plan to follow his career and to see much more of his work as time goes by.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In the space of a few years Charles Fairbanks has gone from conventional prep and collegiate wrestler to one of the few gringo performers of Lucha Libre, Mexico’s equivalent of WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment).

Amid a world of masked figures with exotic alter egos, Fairbanks performs as the One-Eyed Cat. It’s not what you’d expect from this cerebral, soft-spoken, fair-skinned rural Nebraska native. Then again, Fairbanks is an adventurous artist and art educator, which explains why he’s devoted much of the last nine years to Lucha Libre’s high-flying acrobatics and soap opera melodramatics.

Fairbanks, whose pretty boy face and chiseled body are in stark contrast to Jack Black in Nacho Libre, is a photographer and short filmmaker who loves wrestling. Naturally, then, he combines his passions as self-expression. He’s gone so far as affixing a video camera to his mask to record the action.

“Oh, I look silly,” he says of his third eye. “Other wrestlers laugh out loud but they’re always very welcoming. I make sure to establish a relationship before I walk in with a camera on my head.”

His documentary short Irma, an Omaha Film Festival selection, lyrically profiles Irma Gonzalez, a hobbled but still strong, proud former wrestling superstar and singer-songwriter who befriended him at Bull’s Gym on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Last fall Irma won the Best Short prize at the Coopenhagen International Documentary Film Festival. It’s shown at festivals worldwide, as have other works by Fairbanks, some of which, like Pioneers, have nothing to do with wrestling.

Intense curiosity brought him to Mexico in the first place. Oddly, he’d just abandoned organized wrestling. He was a state champion grappler at Lexington (Neb.) High, where his artistic side also flourished. His mat talent and academic promise earned a scholarship to Stanford University, where he wrestled two years before quitting the team.

He was touring Mexico on a rite-of-passage mission of self-discovery and enlightenment when he saw his first Lucha Libre match. He soon started shooting and practicing. He made still images that first trip and has since used video to capture stories.

“I just fell in love with this spectacle,” he says.

Bull’s Gym, located on an upper floor of a hilltop building, is his main dojo, sanctuary and set. It overlooks a cinematic backdrop.

“There’s something powerful for me in looking out at the miles of humble cinderblock housing spread out and up the ridges around Mexico City,” he says. “That view is very beautiful. With all the pollution the sunsets are very colorful. The airport is nearby and so you see the airplanes taking off.

“For me all of this magnifies and modulates the gym’s energy, which is really pretty fervent. There’s often boxing and wrestling going on at the same time in the same room. With all the activity, the ambient noise is really a roar.”

Lucha Libre has a near mystical hold on him now but he admits he originally regarded it as a lovely though bastard version of the wrestling he grew up with.

“At the time, as most competitive wrestlers in the U.S., I denied the connection,” he says. “I said, This is totally different. Now I’ve gotten to the point where I can accept the real links between competitive wrestling and show wrestling.”

Fairbanks, a Stanford art grad with a master of fine arts degree from the University of Michigan, takes an analytical view of these kindred martial arts.

“There is a lot of overlap but at the same time I think they have very different philosophies embedded in them.”

Asking if Lucha Libre is fake misses the point. The visceral, in-the-moment experience is the only reality that matters.

“In my experience of Lucha Libre the matches themselves are not staged — you don’t know who’s going to win. You still maybe want to win, but it’s not just up to you,” he says. “You can’t just go for a pin. You really have to try to entertain. It’s very much like a dance. There’s a certain repertoire of moves my opponent and I know how to do together, and if I start to do one move you recognize this move and you actually respond in a certain way to help me do it more spectacularly.

“And then there are variations, where you’re doing something defensive that’s changing me, so it’s not my move anymore. As we go through this back and forth we establish these sort of rhythms.”

The unfolding dance, he says, is also “an improvised drama” marked by “waves of tension” and “a building of energies. One wrestler is dominating but then the tides turn and the other wrestler comes back. It’s not something scripted but you feel your way through.” The improvisation, he adds, extends to the referee, who “plays his part,” and to the crowd, “who play their part.”

Reared in the no-frills tradition of amateur wrestling, he says “it’s been really hard to learn this completely different way of thinking or feeling reality. I’m the first to say I haven’t mastered Lucha Libre. I’m not trying to make it big as a wrestler in Mexico. I’m trying to learn about wrestling.” He’s also a practitioner of Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

He’s learned about Lucha Libre’s “built-in codes of honor” and “certain ways people present themselves publicly or don’t.” The wrestlers aren’t supposed to reveal their identity outside the ring. He’s made himself an exception.

“I feel OK transgressing this because I’m already marked as Other.”

Irma Gonzalez

In his Flexing Muscles some native wrestlers half-kiddingly harangue this outsider. “It’s very important to me they’re calling me gringo and saying, ‘Go back to your damned country,” he says, as it makes overt his interloper status. As deep as he’s tasted Mexican culture he knows he remains a visitor and observer.

“I’m really conscious of my differences from most of the people there in terms of nationality and economics,” he says.

He’s acutely aware too of his privileged “ability to come in and do this and then leave and go back to the States and make art out of this experience,” adding, “With my movies in a certain sense I try to build in the story of my being there and my relationship to the subjects.” He’s struck by how generous his subjects are in opening their lives and homes to him even as they struggle getting by.

Stranger or not, he engages the culture head-on.

“I do try to immerse myself very much in that world I’m living in, but without losing who I am. I never try to pretend to be Mexican. I try to get as close as I can and I try to understand, but from my point of view.”

Despite the obvious differences between Fairbanks and his fellow performers, he feels a reciprocal kinship, adding, “there’s a certain kind of camaraderie I feel with wrestlers anywhere.” Wherever he’s traveled, including Europe and Asia, he’s wrestled.

Fairbanks has seen much of Mexico but is largely centered in Mexico City and Chiapas, where he teaches filmmaking. He says, “I love to stay with families, I love to have local people to learn from and to interact with.”

Moments of zen-like meditation and magic realism lend his work poetic sensibility and cultural sensitivity. Irma‘s tough title character sings a ranchero in the ring while her circus performer granddaughters romp. In Pioneers Fairbanks lays hands over his father’s ailing back in a shamanistic healing ceremony. Enigmatic stuff.

“I like to make movies that invite more questions,” says Fairbanks, who participated in Werner Herzog’s Rogue Film School and cut his chops working with veteran filmmakers in Brussels, Belgium. “I like to have the films be a process of discovery for the viewers — to not tell the viewers how to see this world — but also a sense of discovery for me as I’m making the films.”

Authenticity is his goal.

“For me it’s important I’m making movies in Mexico that convey a part of experience not covered by our news media.”

As for the future, he says, “I have very specific stories I want to tell in Mexico and in other countries, some related to wrestling, other types of wrestling, some not at all related to wrestling.”

Irma‘s Omaha Film Festival screening is 6 p.m. on March 3 at the Great Escape Theatre as part of the Striking a Chord block of Nebraska documentary shorts.

Related articles

- WWE News: Has Mexican Lucha Libre Star Averno Signed with the WWE? (bleacherreport.com)

- Lucha Future Mexican wrestlers storm The Roundhouse (vidalondon.net)

- Behind the mask – lucha libre wrestlers tap into Kitsap (pnwlocalnews.com)

- Offbeat Wrestlers Celebrate Cinco De Mayo ‘Lucha Libre’ Style (weirdnews.aol.com)

Dean Blais Has UNO Hockey Dreaming Big

My alma mater, the University of Nebraska at Omaha, is not known for making waves in college athletics. The school competes at the Division II level in all its athletic programs, except one — ice hockey. UNO’s D-I hockey program is about 15 years young now and while it’s enjoyed a smattering of success it’s been a long way from being a championship threat. Perception and reality changed in 2009 with the hiring of Dean Blais as head coach. He’s a living legend in the game and his team has already done enough a little more than half way through his second year on the job to have fans and alums like me thinking this could be the start of something big that puts UNO on the map. I recently interviewed Blais for the New Horizons story that follows. While UNO may still be a year or two or more away from competing for a WCHA or national title, UNO hockey is increasingly in the conversation as a tough draw and potential contender. If UNO can keep Blais through the run of his contract in 2014-15, then my old school might finally have the breakthrough success in a major team spectator sport that it’s always dreamed of having. Yes, UNO has a powerhouse wrestling program, but it’s a D-II program and decidedly off the general public’s and national media’s radar. Hockey doesn’t have the broad appeal of football, basketball, or baseball, but when UNO can beat the best of the best in college hockey, as it’s already done this season in defeating Minnesota, Michigan, North Dakota, then you’ve done something.

UPDATE: After a mid-season slump the UNO hockey team has rebounded with a late season surge that’s included a second series split with North Dakota, this time in Grand Forks, where Dean Blais coached all those years, and more recently a sweep of Top Ten power Wisconsin in Omaha. Along the way Blais earned his 300th career college victory and UNO, which had risen to a Top Ten ranking early in the year before sliding down the polls, saw its stock boosted back to No. 12 in one poll and No. 13 in another. More and more observers are feeling this UNO team has what it takes to be a significant factor in the postseason.

Dean Blais Has UNO Hockey Dreaming Big

©by Leo Adam Biga

Published in the New Horizons (http://www.enoa.org/)

When UNO Athletic Director Trev Alberts named Dean Blais the school’s new hockey coach in 2009, it marked a rededicated commitment to a still young program with big dreams.

It was the kind of marquee hire one doesn’t expect from the University of Nebraska at Omaha. What makes Blais marquee material? As a coach, he’s achieved success at every level of the sport — from high school to college to the junior national ranks to the Olympics — all the way to the National Hockey League.

His longest D-I stint was at the University of North Dakota, an elite hockey school where he was an assistant for nine years and head coach for 10, twice leading the Fighting Sioux to national titles and twice winning national coach of the year honors.

To put it in perspective, his coming to UNO would be akin to Roy Williams taking over an upstart basketball program or Bobby Bowden being tabbed to lead the South Florida football program.

The move suddenly made UNO, whose program only dates back to 1997, something more than a potential contender on the hockey landscape. UNO must now be taken seriously, if for no other reason than it went out and got a coach who’s proven he can deliver the goods by recruiting and developing talent that produces all-conference, all-American performers and championship trophies. Dozens of his players have gone on to play professionally.

Even though UNO’s yet to even sniff a conference title, it’s not like Blais walked into a shambles. After a rough couple years, UNO acquitted itself well from 2000 to 2005 before plateauing in 2007 and 2008. There was grumbling the program had run out of steam even though attendance remained steady and the team managed being competitive most nights.

Still, an impending change was in the wind. Hockey revenue was down and UNO long ago fixed its financial wagon to its lone D-I program. As hockey goes, so does Maverick athletics. Alberts put it succinctly:

“Success in hockey in non-negotiable. Creating and sustaining profitability in hockey is a mandate we will hold ourselves accountable to.”

Not long after Alberts arrived as AD Mike Kemp, who founded the program and served as its only head coach for 12 years, stepped aside to be associate athletic director. He recommended as his successor Blais, an old friend then coaching the Fargo Force, a United States Hockey League team. Kemp and Blais knew each other as assistant coaches with the University of Wisconsin and the University of North Dakota, respectively.

“His ability, background and history made him an incredible fit for our program,” Kemp said. “He brings championship experience, attitude and focus that will help propel and direct our program to the next level.”

Because they go back a ways, there’s been no feeling-out process necessary.

“We know each other, we respect each other, and we’ll do whatever it takes to help each other work toward the same common goal,” said Kemp. “It’s one thing to get a program up and going, it’s another to make the next step to national prominence. I think every year we inch closer. My job is to help give Dean the resources he needs in order to be successful.”

News of the Blais hire reenergized UNO hockey fans.

“I truly believe the hiring of Dean Blais signaled a dramatic shift in our approach to excellence,” said Alberts. “With Dean Blais on board, I believe we sent a very strong message about our commitment to hockey…”

Blais’ first year on the job was UNO’s last in the Central Collegiate Hockey Association. The team finished in the upper division of a league with perennial powers like Michigan. Under Blais UNO recorded only the third 20-win season in program history at 20-16-6, finishing an impressive 8-3-1 down the stretch.

In the off-season UNO joined the Western Collegiate Hockey Association, D-I’s premier league and one Blais both played and coached in. UNO’s baptism of fire in the WCHA this season saw its young squad, including a highly touted freshmen class, become the talk of college hockey by sweeping an early road series against heavyweight Minnesota and then taking one of two games at Michigan.

Getting that first WCHA victory at his alma mater, Minnesota, Blais said, was “pretty special,” adding, “It was huge to go in there and win.”

He liked that UNO made an impression on Gopher followers.

“They said our team plays like a bunch of piranhas, can you imagine that? Hungry, fast, tenacious, ferocious. We were proud of them.”

It’s his brand of hockey alright.

“We do everything at top speed, but to do the shooting and the passing and the stick handling at top speed takes a long time to get good at. That’s my thing. Anyone can play hockey at a slow down pace. To play at our level of speed takes a lot of work and a lot of time and a lot of conditioning.”

Then he said something that revealed how he expects, no, demands his team play the fast and furious style he coaches:

“When they don’t play that well then I can get a little nasty.”

He said the relentless, fluid approach is a reflection of how he played the game.

“My feeling is the less restrictions you have the more they improve. The best discipline is self discipline. But I want to give them freedom to improve, and the only way you can improve at times is with your decision making. Do I go in and forecheck or do I just play my position? You can have rules and say you can’t go beyond certain spots on the rink, and that’s coaching, but the more freedom you give the more accountable they are.

“It’s totally against some coaches’ philosophies. Some guys will tell you you’ve got to be this, this and this, like in football. We don’t have that much structure in hockey. We have it during practice. Once they play in games we (coaches) could be drinking coffee and eating popcorn on the bench at times because there’s not a lot we can do. Now, if a player isn’t playing you’ve got to recognize that and warn ’em or sit ’em.”

Don’t assume his practices are loose. He and his staff put in many hours preparing and organizing to ensure the team gets the most out of the high energy sessions. From the opening puck drop in November, the Mavs have flown around the ice. An 8-1-1 start this season landed UNO in the Top 5, its highest ranking ever.

‘The guys came in this summer, worked hard, they went to school and they got some of their classes out of the way. They bonded quicker than I thought,” he said.

While the team slowed after that torrid first month, going 4-7-1 in its next 12 games, UNO enters the last third of the season well up in the conference standings and positioned to qualify for the postseason.

The success has only confirmed Blais was no ordinary hire. Indeed, he’s a legend in amateur hockey circles. His pedigree, almost unmatched. From an early age he knew he was destined to play, teach and coach the game he loved.

He grew up with the proverbial stick in his hand in hockey crazy International Falls, Minn. He and his wife frequent a lake cabin there in the summer. He played for top youth coaches and for the iconic Herb Brooks at the University of Minnesota, where Blais was a standout. His seasoning continued in the professional ranks with the Chicago Blackhawks developmental team in Dallas, Texas.

Then came his assorted coaching stops and championships. His latest title actually came during his first year at UNO, when as U.S. Junior National coach he took a mid-season break from his Maverick duties to lead the American team to a gold medal-winning upset over host Team Canada in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

That victory was so monumental and Blais is so respected in those hockey-obsessed northern reaches that, he said, “every kid in Canada watched that game when we beat ’em for only the second gold medal in 35 years for the U.S., and when I walked through the Saskatoon airport at 7 in the morning there were a hundred Canadians there that shook my hand.”

That’s right, Blais is a rock star among hockey coaches, When announced as UNO’s coach some wondered why a man pushing 60 who’s been to the game’s pinnacle would want to try and get a mediocre program to that same mountaintop.

“I believe Dean is a man that enjoys challenges and is willing to invest the time and energy to bring our dream to fruition,” said Alberts. “Dean’s legacy in college hockey is secure, I’ve challenged him to create a new legacy of building a championship caliber program on the national level that is sustainable.”

“Trev (Alberts) was a big reason I came here,” Blais said from behind his desk in the UNO athletic offices. “I think he’s just done an outstanding job. He’s given us all the resources we need to be successful. He gives us a lot of support daily. He makes it fun to come to work every day.

“He’s a big time guy. I just hope they can hold him as long as I’m here.”

Even though UNO’s never come close to the Frozen Four (college hockey’s equivalent of basketball’s Final Four), Blais saw a program with essential pieces already in place: a charismatic and supportive boss in Alberts; strong university backing; a rabid fan base; and the presence of Mike Kemp, who provides institutional history and a rich hockey background in addition to having established a solid foundation for Blais to build on.

Blais said he’s benefiting from the hockey culture Kemp put in place.

“Everything was done the right way with Mike. I didn’t have to change the culture. It was a pretty well run machine when we got here. He’s got a good hockey mind and a good common sense mind.”

Having an athletic administrator in Kemp who’s a hockey guy makes Blais sleep better.

“He’s looking out for hockey. All the detail stuff at the Qwest, the politics of some of that, Mike deals with, all the behind the scenes stuff with scheduling that takes time and effort, Mike takes care of, so he’s meant a lot to me in the transition. I haven’t had to slug it out with all of that. This is the kind of stuff I hate right here,” Blais said, slapping his palm down on a desk full of paperwork.

In assistants Mike Guentzel and Mike Hastings he has experienced help with strong Omaha ties. Guentzel coached the Omaha Lancers to back to back Clark Cup titles and later worked as an assistant at Minnesota. Hastings succeeded Guentzel with the Lancers and became the winningest coach in USHL history.

UNO hockey seemingly has everything in place to be a force to be reckoned with. Except a decided home ice advantage. It’s no secret UNO, whose home matches are at Qwest Center Omaha, is beating the bushes to elicit support for construction of a South Campus arena designed specifically for hockey.

“That’s the only thing we need here — we need an arena on campus,” said Blais.

While he concedes UNO draws exceedingly well — “fourth in the country in attendance tells me we have the hockey fans in Omaha” — the Qwest is a multi-purpose facility shared with Creighton and other users. That means scheduling conflicts sometimes compel UNO to practice at the Civic Auditorium or the Motto McLean Ice Arena. UNO must also share revenues with the Metropolitan Entertainment & Convention Authority (MECA), which operates the Qwest.

“You talk about an arena on campus you own and all the marketing and concessions and everything else — people tell you it’s $3 or $4 million a year in revenue. Down at the Qwest we don’t get all that revenue, so it’s hard to treat hockey as number one.”

As nice as the Qwest is, it’s too large for the fan base. Even when the Mavs draw their average turnout of 7,500 or 8,000 the cavernous venue is only half full, thus negating the edge a jam-packed intimate space affords. The goal is to make UNO hockey a hard ticket to get.

Then there’s the fact it’s a 10-15 minute drive from UNO, which requires players travel back and forth.

Blais doesn’t want to come off like sour grapes. He actually appreciates having the Qwest — for the time being anyway.

“Now the Qwest is working, our recruiting is working,” he said.

It’s just that he’s been spoiled by the ultimate hockey palace — the Ralph Engelstad Ice Arena at North Dakota, a luxurious $100 million hockey-only facility. A modest version of it is his dream for UNO.

He feels UNO hockey deserves “its due.” He knows it will always play second or third fiddle to Nebraska football and Creighton hoops. He doesn’t begrudge them their support. But he also sees NU can find donors for a planned $50 million Memorial Stadium expansion without batting an eye. He hopes just as Husker boosters are committed to returning NU to elite football status Mav supporters are prepared to put their resources behind making UNO hockey an elite program.

“If we’re going to have the best hockey program in the country we need the best commitment out of this community of Omaha and the whole university. Now, we don’t have to be the king here. I know Lincoln’s football program is the king, but UNO has to be committed as other WCHA schools, and part of it is an arena.”

So how sure does Blais feel UNO will secure the dollars for its own arena?

“I think it’s going to be pretty much a done deal,” he said. “Timeline, I have no clue, and funding, no clue. When money seems to be no object out of the other bench, they’ve got to find a way, and Trev Alberts will deliver and (UNO chancellor) John Christensen will deliver. But it’s not this year. By the time I leave here hopefully there’s a new arena here on campus.”

Last year Blais signed a contract extension to coach UNO through 2014-15.

Some observers speculate Blais is not long for UNO — that it will be hard-pressed keeping him if a Minnesota or another big-time hockey school offers the moon.

“I certainly hope that Dean concludes his coaching career here in Omaha,” said Alberts. “It’s my job to live up to the promises that I made to him and create and maintain an environment that is comfortable.”

For his part Blais betrays no hint he’s itching to leave. Rather he sounds like a man wanting to take UNO to the summit and feeling he has the goods to get there.

“We’ve got I think the most outstanding recruiting class in NCAA hockey this year,” he said.

He’s confident UNO can compete with Michigan and Minnesota for the best talent.

“We’re getting our kids. Are we there yet? Not yet, but I would say the freshmen this year feel they have a better chance of getting into the NHL right here than anywhere else.”

He likes the character of his kids too, saying that flight attendants, bus drivers, waitresses and event staff remark how well his players conduct themselves.

“Everything is please and thank you. Their average grade point average is over 3.0. These student-athletes are going on to be big-time something. It’s about more than wins and losses. Now believe me, they’ll compete, and we’ll train ’em to win, but they’re being trained for the future.”

More than half his freshmen were captains last year on their high school teams.

“Leadership is huge. Leadership starts at the top. As coaches, we’ve got to conduct ourselves right. You wont hear us swearing.”

Speaking of leadership, there is a bit of every coach he’s worked under in him. He’s grateful to have been influenced by some of the game’s greats.

“Well, I’ve been blessed,” he said.

His first mentor was legendary International Falls High School coach Larry Ross. Then Blais came under the wing of Glenn Sonmor and Herb Brooks at Minnesota. He said Sonmor “taught me to have fun every day coming to the rink.”

Brooks, the enigmatic coach of the 1980 U.S. Olympic Miracle On Ice team was hard to know but he produced unquestioned results.

“He’d love you to death when you moved on, but to play for him he was tough. Herbie did not have any friends in hockey. But as far as a coach there’s none better.”

Blais played for college and pro coaching guru Bob Johnson on the U.S. national team and for the respected Bobby Kromm, a one-time NHL coach of the year.

Then there was UND’s Gino Gasparini, whom he said “taught me how to coach up at North Dakota,” where he was Gasparini’s assistant before succeeding him.

All these coaches are inducted in various halls of fame. Blais is right there with them. Only he’s still coaching. At 60, his players are young enough to be his grandchildren. Does he have trouble relating to this generation?

“They probably think I’m nuts anyway,” he quipped. “I don’t treat my players any different now than I did 20 years ago. The bottom line for them is they want to win. They’ll do anything within reason to win, just like kids 20 years ago. I don’t see a whole lot of difference.”

Blais appears satisfied. But things can change. They did at North Dakota. He seemed content there but when the program’s biggest booster, Ralph Engelstad, passed, “things weren’t the same there,” said Blais. Rather than be unhappy, he moved on.

He left to pursue a long-held dream — the NHL, serving as associate head coach and director of player development with the Columbus Blue Jackets. He’s glad he tried it, but it didn’t fulfill him the way working with high school and college kids does. It’s why he returned to the junior ranks before UNO came calling. It’s why he feels at home at UNO.

“Here practices are for preparing kids to get better and get to the next level. In these kids you can see dramatic improvement, you can see their skills develop. That’s what I like. I like going on the ice every day. They know they’re going to develop. It’s a given.”

When UNO broke out of the gate with its dynamic start this season fans and media wondered if this was the year the program would truly break out and claim its place among the juggernauts. Not so fast, said Blais, who better than anyone else knows just how steep a climb it is to college hockey nirvana. He’s been there and back, but with programs much older and steeped in tradition than UNO. It takes time to build a championship club and UNO is still in the growing pains stage.

Jumping to conclusions that this UNO team is Frozen Four worthy right now, he warns, is premature. He sounds every bit the wizened hockey sage when he lays out just how daunting the task is:

“Well, to say we’re competing for a national title, we’re absolutely not, get real.

Michigan Tech hasn’t won a WCHA or national title in 30 years. St. Cloud’s never won the WCHA. Duluth has never won a national title. Colorado College, it’s been 40-50 years. Alaska has never won a WCHA title. Mankato’s never won the WCHA.

“Right away there’s six teams that have never won a WCHA title. Could Omaha? Yep. Is it this year? We’ll see.”

As far as being an elite program, he said, “we’re not there yet. The other thing is, we’ve got to be patient — we’ve only had hockey for 14 years.”

Then again, he saw something in that great start that told him UNO’s ahead of schedule. He knows people are watching now to see if they’re just a one-month wonder or a team to be reckoned with.

Assistant Mike Guentzel echoes Blais by saying the program is moving in the right direction. They remind observers UNO is competing in the toughest conference in the country and more than holding its own.

Dean Blais won’t accept anything less.

Related Articles

- Former Husker All-American Trev Alberts Tries Making UNO Athletics’ Slogan, ‘Omaha’s Team,’ a Reality (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- DU hockey freshman Zucker more than lives up to billing (denverpost.com)

- Cox: Mediocre won’t cut it for Team Canada against U.S. (thestar.com)

- NU regents OK UNO’s move to NCAA Division I (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Big 10 ADs propose men’s hockey for 2013-14 season (sfgate.com)

- National Collegiate Hockey Conference is new home for DU, Colorado College (denverpost.com)

Former Husker All-American Trev Alberts Tries Making UNO Athletics’ Slogan, ‘Omaha’s Team,’ a Reality

Like most Nebraska football fans I watched Trev Alberts play on some very good Husker teams in the early 1990s without ever seeing him in person, by seeing him play on television. I’ve been a Big Red fan since just before the dawn of my teens but I’ve only attended a couple games at Memorial Stadium in Lincoln in all that time. So, my relationship with Alberts remained a virtual one until I interviewed him for the following story I did for The Reader (www.thereader,com). Alberts was a high draft choice of the Indianapolis Colts but repeated injuries cut short his NFL career before he could ever really establish himself. Then, the telegenic Alberts embarked on a successful career as an on-air college football analyst with ESPN. He left the network in a dispute that received a fair amount of attention. The, totally unexpected, he wound up as athletic director at Division II University of Nebraska at Omaha, where he’s in his second year on the job trying to right what had becomes a wayward department. Although some have speculated he took the post as a way to season and position himself for eventually replacing his old coach, Tom Osborne, as NU athletic director, an assertion by the way that both Alberts and Osborne deny, he seems genuinely satisfied to be doing a very unglamorous job at a very unglamorous institution. But as he reveals in my story, he is all about work ethic, seeing a job through, and teamwork, which I believe will keep him at UNO for the foreseeable future, not that I would rule out him one day moving over to NU.

Former Husker All-American Trev Alberts Tries Making UNO Athletics’ Slogan, ‘Omaha’s Team,’ a Reality

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

UNO athletics has always been the overlooked step-child on the area sports scene.

The University of Nebraska at Omaha is still primarily a commuter school, making athletics a hard sell to students and alums. Most have a distant relationship with UNO, whose athletic success rarely translates into fans in the stands save for Maverick hockey, a few football games and a couple wrestling meets.

Things got tenuous four years ago amid revelations the school hushed up athletic budget shortfalls and secretly funneled general university funds to make up the difference. Then-chancellor Nancy Belck came under fire for loose department oversight. The cash cow UNO’s tied its wagon to, Division I hockey, sputtered.

UNO quickly went through three athletic directors. The budget and staff absorbed cuts. Some major boosters criticized school leaders and pulled support. Things stabilized when John Christensen became chancellor in 2007. His April 2009 hiring of Trev Alberts, the former University of Nebraska football All-American (1990-93), Indianapolis Colt and ESPN analyst, turned heads. Getting the chiseled, charismatic Alberts was a bold, outside-the-box move to pump life, credibility and pizazz into a floundering, faceless enterprise.

Some questioned Alberts’ lack of sports administration experience. Not Christensen.

“I wasn’t looking for an administrator, I was looking for a leader, and those are very different things,” said Christensen.

The two have big plans for UNO, including new campus facilities for baseball, softball, soccer and hockey. There’s talk of one day going D-I across the board. UNO is being touted as “Omaha’s Team.” By all accounts, confidence is restored in the department. Alberts’ hiring last year of iconic Dean Blais as hockey coach signaled a sea change in how UNO brands itself. The pretender’s now the contender.

Alberts set the tone at the press conference introducing him as AD, saying, “I believe the potential for UNO’s athletic programs is unlimited.” He hasn’t backed off on that. He sent a message with the Blais hire.

“We wanted to make a statement we weren’t going to mess around anymore, we were going to get into the arena competition and we were going to win and we were going to win the right way. I have never been a part of anything that didn’t attempt to do excellence.”

The rub is that while UNO’s located in a much larger metro than most D-II competitors, it must contend with many more divided loyalties and attractions than, say, a Northwest Missouri State, which is the only game in town in Maryville, Mo.

Husker mania looms large here. Creighton athletic programs are fan favorites. The College of St. Mary, Bellevue College and Iowa Western Community College have their followings. High school athletic contests regularly outdraw UNO’s. The Royals, the Beef, the Lancers, and now the Nighthawks, have committed fan bases, too.

Still, UNO is convinced it can capture more fans and revenue through upgrades, a must anyway if the school’s to ever seriously entertain going D-I, said Christensen.

“Right now, are we Omaha’s team? No, not the way we’re currently structured,” said Alberts. “No, not when you ask your baseball fans to drive to Boys Town to watch a game, you drive your softball fans to Westgate, you drive your hockey fans to the Qwest (Center). Think about it, we’ve been doing everything we could to make it extraordinarily difficult and inconvenient to support UNO athletics. You’re supposed to bring people to your campus.

“Imagine if we had facilities that were convenient, that met market expectations and were on or near the UNO campus.”

Alberts can sound like a pitchman, and that ability to spin things, to charm, to energize, to win hearts and minds, is why supporters like David Sokol are back in the fold. For Alberts, though, the heavy lifting’s just begun.

“We’re still a burden on campus until we’re able to realize that revenue from hockey. Do we have the kind of players, coaches, teams representative of what the market demands? We’re getting closer. I mean, it’s about winning. You gotta win, you gotta win consistently. The moniker ‘Omaha’s Team’ is really a reminder to our staff and coaches of what we aspire to become.”

Alberts said UNO must meet “market expectations of excellence of Lincoln and Creighton and the College World Series.” In some respects, he said, UNO’s done so by winning 11 national championships, adding that feedback from the community, however, indicates UNO’s fallen short in most ways.

Then there’s the awkwardness of dual NCAA membership. Yes, UNO has a D-I hockey program, but it’s a D-II, school, making for a tail-wagging-the-dog scenario.

“At strictly Division II schools, their (athletic) budgets are about three-and-a half to four million. Our budget’s approaching nine million with one Division I sport. When you have dual membership one of two things happens: you either treat all of your programs like their Division II, which is problematic to NCAA compliance. or you end up running your whole department like you’re Division I. That’s equally dangerous, because now in our budget we have all the support units of a Division I department and our Division II programs are benefitting from it.

“We’ve got strength and conditioning staff, compliance staff, three full time sports information staffers, a marketing department — you don’t need a marketing department when you’re Division II. We have a ticketing office. A five-person athletic medicine staff I’ll put up against anybody. The point is, we’re a Division I athletic department whether we like it or not, but we compete at the Division II level. It’s naturally divisive. That’s why the NCAA views dual memberships as problematic.

“That’s why Dean Blais was so important. His personality, his humility — he doesn’t walk around here like…He’s just a Midwestern guy, he’s one of us. Now, he has expectations, don’t get me wrong.”

If other UNO coaches are upset by hockey’s anointed status, Alberts said they haven’t said so. Regardless, there’s no turning back.

“We’ve tried hard to communicate from the day I took the job that that’s the way it’s going to be. You can be frustrated, but if hockey is not successful, we are not successful.”

For now, he said UNO must balance the trappings of its lone D-I sport with the low corporate sponsorships and game guarantees of a D-II school.

“We simply didn’t have the ability and maybe still don’t to deliver the product this market demands, and that’s why this job’s so hard,” he said.

Much of his job is creating a culture of integrity that’s about “making the right decision, not the convenient one.” It’s why he and Christensen talk regularly and why Alberts seeks counsel from his old coach/mentor, Nebraska athletic director Tom Osborne. He also keeps former UNO athletic director Don Leahy close by as advisor and watchdog.

“It’s transparency,” Alberts said. “You know, Nebraskans are a common sense group. Trying to fool people is simply not going to work. First of all you have to be honest with yourself, understand your limitations, your strengths, and show enough humility to welcome the input of others. The first thing we had to do was create a belief. A lot of our coaches have been promised things for years. I would never promise somebody something I couldn’t actually keep.”

He’s impressed by “the passion for this place” that’s kept several veteran coaches and staff members at UNO when they could have bolted for other opportunities. He feels UNO athletics is poised for growth despite a tough economy and NU system-wide cuts.

“We’ve never been in a more difficult position than we’re currently in. What’s encouraging to me is a lot of our problems are self-inflicted and they’re solvable, and we’re committed to finding solutions.”

Related Articles

- A Former Division II Doormat Has Taken Some Big Steps Up (nytimes.com)

- Penn State Starting A Division I Hockey Program (huffingtonpost.com)

- Howard, Morehouse may renew football rivalry (washingtonpost.com)

- UNO Wrestling Dynasty Built on a Tide of Social Change (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Dean Blais Has UNO Hockey Dreaming Big (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- College Hockey’s Seismic Shift Begins Today in Colorado Springs (pikespeaklife.wordpress.com)

Houston Alexander, “The Assassin”

Fighters have always had a certain appeal, whether doing their fighting in the street or in the ring or, since the advent of mixed martial arts events, in the octagon. Houston Alexander of Omaha has pretty much done it all and he’s turned his talent for fisticuffs, combined with his good looks and charisma, into a bit of a run in the Ultimate Fighting Championship, although he ended up losing more than he won. He’s also a radio DJ, graffiti artist, self-styled hip-hop educator, and man-about-town, making him more than the sum of his parts. The following story I did on him for The Reader (www.thereader.com) hit just as he was on his way up, and even though his star has since dimmed, he’s a survivor who knows how to work his image. He and his family didn’t like some of the things in my story, but he also knows that comes with the territory.

DJ Doc Beat Box and Houston on a school Culture Shock Tour

Houston Alexander, “The Assassin“

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Ultimate fighter Houston “The Assassin” Alexander of Omaha is being a good soldier for the photo shoot. Stripping down to his trunks, he poses in the middle of a south downtown street one late summer afternoon. He’s asked to look menacing, hardly a stretch for the chiseled, tattooed, head-shaved graffiti artist-street thug turned Ultimate Fighting Championship contender. He remarks about “those guys looking out those windows” at his half-naked ass, meaning inmates at the Douglas County Correctional Center peering out the razor-wired windows of the facility just down the block. He once peered out those same windows upon this very street.

“I was inside the cage in ‘97. I just got through beating up a cop and they took me down,” he says matter-of-factly. “The cop tried to grab me and I swung back and hit the guy. It was illegal what he was trying to do to me in the first place. He was trying to beat me up. I didn’t get charged for hitting a cop. I got charged for something else. I did like six months.”

It’s not his only run-in with the law. He alludes to “a whole bunch of domestic,” referring to disturbances with a woman that police responded to.

The fact he has a record only seems to add to his street cred as one tough M.F.. His fans don’t seem to mind his indiscretions. Passersby shout out props. “What’s up, Houston Alexander?” a guy calls out from his sedan. Another, on foot, invites him to a suburban sports bar where, the homey says, “they all love you out there.”

Now that Alexander is a certified UFC warrior, he’s handling all the hoopla that goes with it like a man. He seems unfazed by the endorsement deals, sponsorships, personal appearance requests, interviews, blog appraisals and fan frenzy demands coming his way these days.

Increasingly recognized wherever he goes, he eagerly acknowledges the attention with his trademark greeting, “What’s up, brother?” and firm handshake, giving love to grown men and boys whose star-struck expressions gleam with admiration for his fighting prowess. The African-American community particularly embraces him as a home boy made good. A strong, hard-working single father of six who came up an urban legend for his scribbing and street fighting. He’s one of their own and it’s them he’ll most be representing come next fight night.

Barely three months have passed since his furious UFC debut on May 26, when the light heavyweight put an octagon whupping on contender Keith Jardine at UFC 71 in Las Vegas. After getting knocked down in the first 10 seconds, Alexander quickly regrouped. His relentless pressing style backed Jardine against the fence, where he unleashed a flurry of knees, elbows, uppercuts and hooks to score a technical knockout. Now Alexander’s primed for his next step up the sport’s elite ladder.

He and his local coaching-training team led by Mick Doyle and Curlee Alexander, the same men who got him ready for his dismantling of “The Dean of Mean“ Jardine, left for Great Britain on Monday to make final preparations for a September 8 clash with Italian Alessio Sakara on the UFC 75 card at London’s O2 Arena.

Doyle, a native of Ireland, is a former world champion martial arts fighter. His Mick Doyle Mixed Martial Arts Center at 108th and Blondo is the baddest gym around. He’s trained and worked the corner of several world champs. Curlee Alexander, a cousin of Houston’s, is a former NAIA All-America wrestler at UNO and the longtime head wrestling coach at North High School, where he’s produced numerous individual and team state champions.

Houston Alexander when to North, but other than brief forays in wrestling and football, he didn’t really compete in organized sports, unless you count weight lifting and body shaping. He was a two-time Mr. North. There was never enough money or time, he explains. By high school he was already a burgeoning entrepreneur with his art and music. Besides, he said, “I always had responsibilities at home.” But everyone knew he was gifted athletically.

The way Doyle puts it, Alexander’s “a freak” of nature for his rare combo of power and speed. The 205-pounder can bench press more than twice his body weight, yet he’s not muscle bound. He’s remarkably agile and flexible. Alexander came to him a “raw” specimen, but with abundant natural talent and instincts. Alexander knows he has a tendency to resort to street fighting, but Doyle recently reassured him by saying, “Everything we’re showing you sticks because it’s brand new. It’s not really replacing anything that anyone else taught you.” A blank slate.

“He wants to learn,” Doyle said. “He’s very confident, but he’s grounded. It’s a joy to coach someone like him.”

Curlee Alexander, a lifelong boxing devotee, has rarely seen the likes of his cousin, who’s made this old-school grappler a UFC convert. He, too, tells Houston not to change what’s worked, street fighting and all, but to harness it with technique. When Houston came to him eight months ago asking that he condition him, Curlee was dubious. Houston’s work ethic won him over. “He’s certainly determined.” His dismantling of Jardine convinced him he was in the corner of a special athlete.

“It was the most amazing night as far as being a coach I’ve ever had. All the things we had worked on were coming to fruition. He was doing it. He put all this stuff together at that moment. Incredible.”

For his part, The Assassin credits his coaches with getting him to the next level.

“Without Mick and Curlee, there’s no me. I had the raw skills, but they’re fine tuning what I have to turn me into this champ I need to be,” he said. “I love those guys. They’re the real deal. No joke. They know what they’re talking about. I do whatever they tell me to do. There’s no getting away with anything, brother, believe me. But I wouldn’t want to cheat myself anyway.”

With their help, he said, “I’m more technical and all the power and strength I have is programmed a whole different way. More controlled. But don’t get it twisted. If I need to turn it up and go hard in the paint, it can easily change.”

A win Saturday night should put the fighter in the Top 10 and that much closer to what some anticipate will be a world title challenge within a year. Doyle told Alexander as much after an August meeting to breakdown the tape of the Jardine fight. “I told you this would be a two-year process. We’re only three months into this deal and look how much better you’ve gotten. Just think in another year where you’re going to be. You’ll be able to get in the ring with Wanderlei Silva (the legendary Brazilian world champ, late of the PRIDE series, now a UFC star).”

“We understand the window of opportunity on this thing is short,” Doyle said. “We want to get it there.” Asked if Alexander’s age, 35, is part of the urgency, he said, “Maybe some of it. If he gets an injury he’s not going to heal like a 25-year-old. He’s got some years left, but let’s get him the money. He’s got six kids.”

The Sakara-Alexander tussle is key for both fighters. Doyle calls Sakara “a stepping stone” for his fighter, whom he said must “prove the Jardine thing wasn’t a fluke.” He describes it as “a make or break fight” for Sakara, who’s coming off two straight losses at 185 pounds. “He’s gotta win to stay in the UFC. Sakara’s in the way of bigger and better things, so he’s gotta go.”

Cool, suave, laidback, playful. Quick to crack on someone. Alexander’s extreme physicality manifests in the way he grabs your hand or brushes against you or delivers none too gentle love taps or engages in horse play. When he needs to, he can turn off the imp and attend to business. He’s all, ‘Yes, coach…‘Yes, sir,’ with his trainers, putting in hour after hour of roadwork, skipping rope, weight lifting, calisthenics, stretching, grappling, sparring and shadow boxing under their watch.

For months he’s trained three times a day, up to six to eight hours per day, six days a week, devoting full-time to what not long ago was just “a hobby.” He’s disciplined and motivated enough to have transformed his physique and refined his fight style. After years of itinerant club fighting, all without a manager or trainer, only himself to count on, he began formal, supervised training less than a year ago. He worked with Doyle a few weeks before the Jardine clash, which also marked the first time he prepped for a specific foe and followed a nutritional supplement regimen. By all accounts he followed the strategy laid out for him to a tee.

“I have no problem working,” he said. “I’ve been working all my life.”

Doing what needs to be done is how he’s handled himself as an artist, DJ, father, blue collar worker and pro fighter. Whatever’s come down, he’s been man enough to take it, from completing large mural projects to getting custody of his kids to donating a kidney to daughter Elan to breaking a hand in a bout yet toughing the injury out to win. “Most people don’t know I’m fighting with one kidney,” he said. He’s paid the price when he’s screwed up, too, serving time behind bars.

The UFC is all happening fast for Alexander, which is fine for this dynamo. But the thing is, he’s come to this breakthrough at an age when most folks settle into a comfortable rut. No playing it safe or easy for him though. The truth is this opportunity’s been a long time in the making for Alexander, who enjoyed local celebrity status way before the UFC entered his life.

The veteran Omaha hip hop culture scion, variously known as Scrib, FAS/ONE and The Strong Arm, has always rolled with the assurance of a self-made man and standup brother. All the way back to the day when he protected the honor of his siblings and cousins with his heavy fists, first on the mean streets of East St. Louis, Ill., then in north O, where his mother moved he and his two younger siblings after she left their father. Alexander was all of 8 when he became the man of the family.

“I’m the oldest, so I was always expected to be the leader of the whole bunch. See, I’ve fought all my life, and that’s no exaggeration. It was always a situation where I couldn’t walk away, like somebody putting their hands on my girl cousins. I got into a lot of fights because of my brother,” he said. “I don’t interfere with no one’s business, but if you put your hands on my family, then it becomes my business. A lot of people got beat up because of that.”

Respect is more than an Aretha Franklin anthem for him.

“I don’t go around disrespecting people unless they disrespect me. There’s always a line you can’t cross.”

Growing up in a single-parent home, he started hustling early on to help support the family. What began as childhood diversions — fighting and music — became careers. When he wasn’t busting heads on the street, he was rhyming, break dancing, producing and graffiti tagging as a local hip hop “pioneer.” His Midwest Alliance and B-Boys have opened for national acts. He had his own small record label for a time, His scrib work adorns buildings, bridges and railroad box cars in the area. He mostly does murals on commission these days but still goes out on occasion with his crew to scrib structures that just beg to be tagged.

It wasn’t until 2001 he began getting paid to fight, earning $500-$600 a bout. He estimates having more than 200 fights since then, of which he’s only been credited with seven by the UFC, sometimes getting in the ring multiple times per night, on small mixed martial arts cards in Omaha, Lincoln, Sioux City, Des Moines. These take-on-all-comers type of events, held at bars (Bourbon Street), concert venues (Royal Grove), outdoor volleyball courts, casinos, matched him against traditional boxers as well as kickboxers, wrestlers and practitioners of jujitsu and muay thai.

“I fought everybody, man. I fought every type of fighter there is,” he said. “Fat, short, tall. I fought a guy 400 pounds in Des Moines. Picked him up from behind and slammed him on his neck and beat him senseless. I’m a street fighter, man. When you street fight you don’t care what size and what style. It don’t matter.”

There were times he’d MC a rap concert and fight on the same venue. “Dude, it was funny, man, because first people would see me on stage saying, ‘Hey, get your hands in the air,’ and then five hours later I’m kicking somebody’s ass in the ring.”

MMA promoter Chad Mason, who promoted many of Alexander’s pre-UFC matches, confirmed the fighter saw an inordinate amount of action in a short time.

“Sometimes he was doing two-three fights in a night. He’d do ‘em in Des Moines and then turn around two days later and go to Sioux City and fight a couple more times there. So there were times he probably had six fights in a week,” Mason said. “Of course everybody he fought wasn’t top of the line competition, but he was beating Division I college wrestlers, pro boxers, pro kick boxers, guys that had years of experience. They could come out of the woodwork to just try against Houston, and he’d beat ‘em. I mean, he’d knock ‘em out.”

By Alexander’s own reckoning his personal record was fighting and winning five times in one night in Sioux City.

“I was feeling it that night. It was just crazy, man.”

He began fathering kids 15 years ago and now has custody of his three boys and three girls, by three different mothers. Four of the kids are from his ex-wife of 10 years. He, his kids and his hottie of a new girl friend, Elana, share a three-room northwest Omaha apartment until he finds the right house to buy. He has the perfect crib in mind — a three-bedroom brick house with wood floors.

As a single daddy he has a new appreciation for raising kids. He makes it work amid his training and other commitments with some old-fashioned parenting.

“My kids have structure. It’s all military style. We have to do everything together. We all have breakfast together. We all sit down at the table together for dinner. It can’t work any other way,” he said.

Between school and extracurricular activities, he said, “I try to keep them as active as I can.” He helps coach his boys club football team, the Gladiators. One girl’s in ballet, another in basketball. “I’m always moving, so they’re always moving.”

He vows his children, ranging in age from 15 to 4, are his prime motivation for making this fight thing pay off.

“I want to win to secure a financial future for my kids’ college education. Again it always goes back to the kids.”

To makes ends meet he worked on highway construction crews for nearly 10 years. Until the UFC discovered him, he was perhaps best known locally for his radio career, first at Hot 94.1 and now at Power 106.9, where he does everything from sales to promotions to engineering to hosting his own independent music show on Sunday nights.

He’s also an educator of sorts by virtue of his long-running School Culture Shock Tour that finds him presenting the history of hip hop to students.

Whatever it takes to put food on the table, he does. “I’m a hustler, man. This is true. That’s why I have Corn Hustler on my forearms,” he said, brandishing his massive, graffiti-inked limbs. “That’s a street term. I stay busy. I have always kept busy.”

He strives to be “well-rounded” and therefore “I’m always in that mode to where I’m doing something to better myself.”

Always looking for fresh angles, a pro sports career is right up his alley with its marketing possibilities and mix of athletics and entertainment. Besides catching on like wildfire, the sport is a crowd-pleasing showcase for men wishing to turn their cut bodies, mixed martial arts skills, macho facades, charismatic personalities and catchy names into national, even international, brands. Having built to this moment for years, he leaves little doubt he’s ready to take advantage of it, confident he will neither lose himself if he succeeds nor crash should he fail.

“I give myself five or six years, maybe more than that if I keep training and don’t get hurt. (Randy) Couture is 43 and he fought a younger guy and whupped his ass. If it doesn’t work out with the UFC, who cares? I was never a UFC fan anyway.”

Would he ever return to those $500 paydays in Sioux City? “Yeah, in a hearbeat. Why not? I love fighting, man. That’s the whole thing — I love fighting.”

What is it ultimately about fighting that’s such a turn on?

“I think it’s the rush,” he said. “I know have the ability to beat the guy, but it’s still the rush of not knowing. You’re out there to prove to this guy that you know how to whip his ass. You think Jardine had remotely in his mind he was going to get done like that? I don’t think so. But I knew. Because I know deep down in my heart what type of abilities I have.”

As he says, the UFC was never really his goal until promoter and friend Chad Mason hooked him up with fight manager Monty Cox. What little Alexander’s seen of the competition out there doesn’t impress him. No high octane attacks like his.

“I never really watched the UFC. When I started watching it all I saw was this assembly line of guys. I really haven’t seen anyone come with it or bring it. Maybe the guys they bring in are not as passionate about it as I am. I really love fighting. When I get in the ring I love doing it, so I’m going to bring it to the guy 110 percent. If a guy’s trying to slack off on me and he wants to me wear me down, nu-uh, we’re going to pick up the pace a little bit and we’re going to go at it.

“If you want to try to wrestle and do all that, OK, that’s fine, but you’re going to get kneed and you’re going to get elbowed and you’re going to get disrupted.”

Disruption could be his alter ego name inside the octagon. It’s a mantra for what he tries to do to opponents. “Always disrupt, man, always disrupt,” he said. “To where they can’t think, because if you can’t think, you can’t react. That’s been my concept through the years,”

He said a quick review of the Jardine fight will reveal “I had hands in his face all the time. I was so close to him to where he couldn’t use those long arms, and I kept applying the pressure. Like my coaches said, ‘Always apply the pressure,’ and that’s what I did with that guy. I kept him disrupted.”

Alexander puts much stock in his “explosiveness.” “Once a guy tries to attack me,” he said, “my counter moves are so swift and fast and powerful, that definitely we’ll take the guy out. They’re all in short bursts.”

Doyle doesn’t even want Alexander thinking about leaving his feet. He wants him to dispatch Sakara on Saturday night the same way he did Jardine — standing straight up, his trunk and feet forming a triangle base, throwing blunt force trauma blows with knees, elbows and fists. Back in July Doyle told his fighter, “Just like in the Jardine fight, you don’t need to go to the ground. We’re going to knock the guy out or make the referee stop it. That will get you a title quicker. He’s gotta go.”

“That’s our motto for 2007 — he’s gotta go. He’s in the way. The Italian guy has got to go. Chow, baby,” Alexander said of Sakara. “I really want to go in and knock this guy out or really do something bad to him. I want people to be scared when they look at the footage. I want to show them what I’ve got.”

In his soft Irish brogue Doyle explained to his fighter how keeping an element of mystery is a good thing.

“Dude, if you go out there and knock this guy out, people are still going to wonder, What else can Alexander do? You know what, let them try to find out. If we can finish this guy on our feet, let’s do it. You don’t need to show people any more of your game than what is necessary to get the job done — until you come up with an opponent who makes you show more,” he said. “Keep it simple.”

Doyle, a Dublin native who came to America in ‘86, has tried to prepare Alexander for any technical tricks opponents might try to spring on him. He’s had him go toe-to-toe with athletes skilled in boxing, wrestling, kicking, you name it, bringing in top sparring partners from places like Chicago and sending him to Minneapolis to work with world-class submission artists good enough to make him tap out.

The fighter will have seen everything that can be thrown at him by fight night.

“They’ll get that move on you one time, and that’ll be the last time,” Doyle told Alexander. “That way when you step in the ring, and a guy goes to make his moves, you’ll feel ‘em coming, you’ll see ‘em coming, you’ll know what to do.”

Doyle and his team have spent much time honing Alexander’s footwork and stance, making sure his weight is balanced. It’s all done to harness his natural power, which becomes “more dangerous” when leveraged from below. The uppercuts that devastated Jardine were practiced repeatedly. The force behind those vicious shots, Doyle reminded him, comes from “using your legs,” which is why he harps on Alexander to maintain the foundation of a solid base.

To improve his quickness, Alexander often spars with lighter, faster guys and wears heavy gloves, so that when fight time arrives his hands and feet move like lightning.

The gameplan with Sakara is to pepper him with double jabs, then push off or slide step in to follow up with an arsenal of kill shots. For all his bravado and bull-rush style, Alexander is all about “protecting myself,” which is why a point of emphasis for the Sakara fight has been to keep his hands up against this classical boxer.

“As long as you keep your hands up you’re not going to get hurt,” Doyle said after an August sparring session. “None of the guys out there are just like that much better than you. But if you give them a mistake, they are more experienced and more technical to capitalize on it than you are right now. In a year, it’s all going to be different. Just like this guy Sakara, we’re going to make him give us a mistake.”

Sakara’s habit of keeping his hands low is one Alexander expects to exploit.

One thing Alexander said he’ll never be is intimidated.

“It’s important to inject fear. Everyone gets scared of the way a guy looks. I truly believe that half these people get scared by looking at the guy in the ring. I think Jardine beat a lot of people by the way he looked,” he said. Not that it was ever a possibility in his own mind, but Alexander said Jardine lost whatever edge he might have had when he heard him give an interview and out came a voice that didn’t match the Mr. Mean persona. “There’s no way I’m going to get my butt kicked by a guy that sounds like Michael Jackson,” he said.

Jardine’s comments leading up to the fight led Alexander and his camp to believe the veteran UFC fighter took the newcomer lightly. Alexander warns future foes not to make the same mistake.

“If anybody approaches me the same way to where they’re not taking me serious, that’s what’s going to happen. Every time. I’m going to be passionate about it. I’m going to be right or die with it. That means I’ll die in the ring before I actually lose. That’s how I feel about winning. Winning is everything, I don’t care what nobody says. If I hadn’t of won…you wouldn’t be talking to me,” he told a reporter.

It’s not hard to imagine Alexander gets an edge, both by the ripped, powerful figure he projects, and the calm demeanor he exudes. His serenity is no act.

“I’m mentally prepared for this thing,” he said. “I’ve always been mentally strong…tough. Make no mistake about it, the mental game I have down. No one’s going to out-mental me. No one’s going to deter me left or right, forward or back, because I have it down. Guys ask me, ‘Are you going to be nervous going out in front of 50,000 people?’ No, because I’ve done it before. I’ve done it with concerts. I’ve hosted concerts with 10,000 people. I do the school thing every week with 700-800 kids. Kids are the worst critics ever. If you can’t get kids’ attention, you’re garbage, and every week I get those kids’ attention. My working in radio, having 30,000 people listening every time I crack that mike, that’s pressure. So for me being in front of a crowd is nothing.”

Like all supreme athletes, Alexander exudes a Zen-like tranquility. His senseis — Mick and Curlee and company — have brought out the samaurai in him. It’s why he’s such “a calm fighter” entering the octagon.

“What it comes down to, you just have to play it out all the way and see where the chips fall,” Alexander said. “Everything happens for a reason. It is what it is.”

Related Articles

- UFC cuts The Dean of Mean (theglobeandmail.com)

- The Ten Greatest Upsets in MMA History (bleacherreport.com)

- Five Fighters Who Failed to Live Up to the Hype (bleacherreport.com)

- Inside The Undercard! UFC on Versus Live – Jones vs. Matyushenko (fighters.com)

- Alexander-Irvin Rematch Ticketed for Shark Fights 14 (evilmasterreport.com)

Johnny Rodgers, Forever Young, Fast, and Running Free (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

In the constellation of University of Nebraska football legends, Johnny Rodgers is probably still the brightest star, even though it’s been going on 40 years since he last played for the Huskers. So dazzling were his moves and so dominant was his play that this 1972 Heisman Trophy winner , who was the one big play threat on the 1970 and 1971 national championship teams, remains the gold standard for NU playmakers. The fact that he was such a prominent player when NU first reached modern day college football prominence, combined with his being an Omaha product who overcame a tough start in life, puts him in a different category from all the other Husker greats. The style and panache that he brought to the field and off it helps, too. He’s also remained one of the most visible and accessible Husker legends.

Johnny Rodgers, Forever Young, Fast, and Running Free (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

“Man, woman and child…the Jet has put ‘em in the aisles again.”

Viewing again on tape one of Johnny Rodgers’ brilliant juking, jiving broken field runs, one has the impression of a jazz artist going off on an improvisational riff and responding note by note, move by move, instant by instant to whatever he’s feeling on the field.

Indeed, that is how Rodgers, the quicksilver University of Nebraska All-American and Heisman Trophy winner known as The Jet, describes the way his instinctive playmaking skills expressed themselves in action. Original, spontaneous, unplanned, his dance-like punt returns and darting runs after catches unfolded, like riveting dramatic performances, in the moment. Poetry in motion. All of which makes his revelation that he did this in a kind of spellbound state fascinating.

“I remember times when I’d go into a crowd of players and I’d come out the other side and the first time I’d know anything about what really happened was when I watched it on film,” he said. “It was like I was in a trance or guided or something. It was not ever really at a conscious level. I could see it as it’s happening, but I didn’t remember any of it. In any of the runs, I could not sit back and say all the things I’d just done until I saw them on film. Never. Not even once.”

This sense of something larger and more mysterious at work is fitting given Rodgers unlikely life story. In going from ghetto despair and criminal mischief to football stardom and flamboyant high life to wheeler-dealer and ignominious failure to sober businessman and community leader, his life has played out in surreal fashion. For a long time Rodgers seemed to be making his legend up, for better or worse, as he went along.

Once viewed as an incorrigible delinquent, Rodgers grew up poor and fatherless in the Logan Fontenelle projects and, unable to get along with his mother, ran away from home at age 14 to Detroit. He was gone a year.

“You talk about a rude awakening. It was a trip,” he said.

He bears scars from bashings and bullets he took in violent clashes. He received probation in his late teens for his part in a Lincoln filling station robbery that nearly derailed his college football career. He served 30 days in jail for driving on a suspended license. Unimaginable — The Jet confined to a cell. His early run-ins with the law and assundry other troubles made him a romantic outlaw figure to some and a ne’er-do-well receiving special treatment to others.

“People were trying to make me out to be college football’s bad boy,” is how he sums up that tumultuous time.

Embracing his rebel image, the young Rodgers wore shades and black leather and drove fast. Affecting a playboy image, J.R. lived a Player’s lifestyle. By the time he signed a big contract with the Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League, he was indulging in a rich young man’s life to the hilt — fur capes, silk dashikis, fancy cars, recreational drugs, expensive wines and fine babes. Hedonism, baby.

Controversy continued dogging him and generating embarrassing headlines, like the time in 1985 he allegedly pulled a gun on a cable television technician or the two times, once in 1987 and again in 1998, when his Heisman was confiscated in disputes over non-payment of bills. Then there were the crass schemes to cash in on his fame.