Archive

Writers Joy Castro and Amelia Maria de la Luz Montes explore being women of color who go from poverty to privilege

Joy Castro

Writers Joy Castro and Amelia Maria de la Luz Montes explore being women of color who go from poverty to privilege

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in El Perico

Two University of Nebraska-Lincoln scholars and authors, one Mexican-American, the other Cuban-American, contributed pieces to a new anthology of essays by women, An Angle of Vision (University of Michigan Press).

The book derives its title from the essay by Joy Castro, an associate professor in the Department of English at UNL and the author of a 2005 memoir, The Truth Book (Arcade Press). Her colleague, Amelia Maria de la Luz Montes, is an associate professor of English and Ethnic Studies and director of UNL’s Institute for Ethnic Studies. Montes penned the essay “Queen for a Day.” She’s also edited a new edition of a 19th century novel written by a Mexican-American woman. The book, Who Would Have Thought It? (Penguin Classics), is a satiric look at New England through the eyes of a teenage Latina.

All the authors in Angle of Vision hail from poor, working-class backgrounds, a counterpoint to the privileged lives they lead today in academia and publishing. As Castro said, “when you see from a different angle, you notice different things.” The authors use the past and present as a prism for examining class, gender, ethnicity and identity. Each navigates realities that come with their own expectations and assumptions, making these women ever mindful of the borders they cross.

Montes and Castro are intentional about not diminishing their roots but celebrating them in the various worlds they traverse — higher education, literature and family.

Said Castro, “Getting out of poverty, through effort and luck, has never felt like permission to say, ‘Whew! Now I can kick back and enjoy myself.’ Acknowledging my background means that much of my work, whether it’s the short stories and essays I write or the working-class women’s literature I teach, focuses on bringing attention to economic injustice as well as racism and sexism.

“Latinidad is hugely important to me, and it is definitely connected with class and gender. Because of the great wave of well-to-do Cuban immigrants who came to the USA when Fidel Castro took power, many people assume all Cuban-Americans are wealthy, right-leaning, and so on. That wasn’t the case for my family, who had been in Key West since the 1800s and were working-class and lefty-liberal. In a forthcoming essay, ‘Island of Bones,’ I explore that little-known history.”

Castro embraces the many dimensions of her ethnicity.

“Mostly, my Latinidad has been a source of strength, comfort and great beauty throughout my life. It means food, music, love, literature, home. I’m proud to belong to a rich, strong, vibrant culture, and I love teaching my students about the varied accomplishments and ongoing struggles of our people.”

Being a person of color in America though means confronting some hard things. She said her father’s experience with racism and police abuse caused him to assimilate at any price. “For my brother Tony and me our father’s life is a cautionary tale about the costs of shame and of trying to erase who you are.”

By contrast, she said, “We raised our children to be proud of their heritage. My son is fluent in Spanish, which my father refused to speak at home.”

Complicating Castro’s journey has been the aftermath of the abusive childhood she endured, a facet of her past she long sought to suppress.

The past was also obscured in the Montes home. Her Mexican immigrant mother endured a bad first marriage. Amelia didn’t find out about her struggles until age 25. It took another 25 years before she felt mature enough to write about it.

“I do think the experience of coming from a working class family and being a minority we have certain pressures in society,” said Montes. “In order to be successful or in order to assimilate as my mother worked hard to do you had to not let on the oppressions infringing on your own spaces. You processed them in other ways, but outside of the house or outside your own private sphere you made sure you’re presenting a suitable facade.

“It is a survival mechanism. At the same time one must be careful because if you let it encompass you, then the facade overtakes you and you lose who you are.”

Being a lesbian on top of being a Latina presents its own challenges. Montes said in fundamentalist Christian or conservative Catholic Latino communities her sexual identity poses a problem. She’s weary of being categorized but said, “Labels are always necessary when there’s inequality. If there wasn’t inequality we wouldn’t need these labels, but we need them in order to be present and to have people understand. I always tell my students that just because I’m Latina does not mean I represent all Latinas or all Latinos, and that goes for lesbians as well.”

For Montes, with every “border fence” crossed there’s reward and price.

“There’s success, there’s achievement,” she said, “but there’s also loss because once you cross a fence that means you’re leaving something behind. There is a celebration in knowing my mother is very happy I have succeeded as a first generation Latina. I will never forget where my mother came from and who she is, even the sufferings and difficult times she journeyed through.”

Montes is now writing a memoir to reconcile her own self. “In looking back I’m processing what happened in order to better understand it and to also claim where I come from, so that I don’t hide I come from a working class background, or I don’t only speak English, but make sure I continue to practice my Spanish.”

Castro found writing her memoir liberated her from the veil of secrecy she wore.

“Having my story out there in the world helped me let go of the impulse to hide the truth of my life. I’m still pretty shy, perhaps by nature, but disclosing my story helped me let go of shame. And I was hired at UNL ‘because’ of my book, so everyone knew in advance exactly what kind of person they were getting. What a relief. It’s easier to live in the world when you can be free and open about who you are and where you come from. You can breathe. You’re not anxious. You’re not trying to perform something you’re not.”

She said the project helped her appreciate just how far she’s come.

“Laying it all out in book form, I came to respect the difficulty of what I’d had to navigate. In some ways, my journey was as challenging as moving from one country, one culture, to another. All the new customs have to be learned. Also, another great benefit was that writing it down…shaping it into a coherent narrative for readers helped me gain objectivity and distance on the material. It became simply content in a book, rather than a terrible weight I carried around inside me.”

Castro said her experience made her sensitive to what people endure.

“We never know what other people are carrying. In fact, sometimes they’re going to great lengths to conceal their burdens, to pass as normal and okay. Remembering that simple truth can help us be gentle with each other.”

Castro and Montes know the emotional weight women bear in having to be many different things to many different individuals, often at the cost of denying themselves . Each writer applies a feminist perspective to women’s roles.

“I’m glad to say things are changing, but despite many advances in women’s rights, Latinas are often pushed, even today, to put men first, to have babies, to love the church without question, to be submissive and obedient to authority,” said Castro.” “It took me a long time to crawl out from under the expectations I was raised with.”

“It seems to me in the early 20th century there was a big push, a big advancement, then we fell off the mountain in the ’40s, ’50s, 60s, then came back in the ’70s and ’80s. and right now I think we’re retreating backwards again,” said Montes. “The vast majority of people out of work and homeless are women and children. I’m heartsick about what’s going on in Calif. and other parts of the country concerning education and how more and more the doors of education are closing to working class people and to out-of-work minorities because of the hikes in tuition, et cetera.”

Montes concedes there’s “a lot of advances, too,” but added, “I’m always wanting us to keep going forward.”

Castro feels obligated to use her odyssey as a tool of enlightenment and empowerment. “I’m lucky and grateful to be someone who has made it out of poverty, abuse and voicelessness, who has made it to a position where I have a voice. It’s an important responsibility. My own published fiction, nonfiction and poetry all concern issues of poverty. I make a point of teaching literature by poor people in the university classroom, where most of my students are middle-class.”

She’s taught free classes for the disadvantaged at public libraries and through Clemente College. For two years now she’s mentored a young Latina-Lakota girl born in poverty. “In choosing to mentor, I wanted to keep a strong, personal, meaningful connection to what it means to be young and female and poor. I wanted to be the kind of adult friend I wished for when I was a girl,” said Castro.

Both authors were delighted to be represented in Angle of Vision. “It was a surprise and a great compliment,” said Castro. “It’s such a good book with so many wonderful writers.” “The resilience and strength of these writers in navigating through difficult childhoods really comes out. It’s amazing,” said Montes. Both have high praise for editor Lorraine Lopez. The fact that a pair of UNL friends and colleagues ended up being published together makes it all the sweeter.

To find more works by them visit their web sites: joycastro.com and ameliamontes.com.

Actor Peter Riegert makes fine feature directorial debut with “King of the Corner”

About three years ago or so I heard that one of my favorite actors, Peter Riegert, was going around the country with a feature film he starred in and directed, King of the Corner. His appearance in Nebraska took on greater import for me when I learned that the film was adapted from a group of short stories by noted author Gerald Shapiro, who teaches at the University of Nebraska. Long story short, I obtained a screener of the film and I really responded to it, and then I did a phone interview with Riegert, who proved a delight. The resulting story appeared in the Jewish Press. I highly recommend King of the Corner. And if you don’t know his name or work, I recommend two essential Riegert films: Local Hero and Crossing Delancey, which also happen to be two of my favorite films. Two of Riegert’s best films, Crossing Delancey and Chilly Scenes of Winter, were directed by Omaha native Joan Micklin Silver, the subject of an extensive profile on this blog under the title, “Shattering Cinema’s Glass Ceiling.”

Actor Peter Riegert makes fine feature directorial debut with “King of the Corner”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Jewish Press

For months now, noted stage and screen actor Peter Riegert has been taking his new film comedy about “crummy Jews,” King of the Corner, on the road. Best known for his work in front of the camera, he’s the director, co-writer and star of this engaging satire that critic Roger Ebert gives 3 1/2 stars. While this is the first feature he’s directed, Riegert won praise for helming the 2000 short By Courier, an Oscar-nominated adaptation of the O. Henry short story.

In March, he brought his new film to Lincoln, where he has a history showing his work and where his co-script writer, Gerald Shapiro, author of the short stories upon which the film is based, resides and teaches. Although they’d never met before their collaboration, Shapiro’s long admired Riegert’s work. A University of Nebraska-Lincoln creative writing professor, Shapiro utilizes one of the actor’s best known films, Crossing Delancey, along with an audio reading by Riegert of a famous Yiddish story by Sholem Aleichem, in his Jewish American fiction class.

“I was an admirer of his before I ever saw ‘Crossing Delancey’. I loved him in ‘Animal House’. I loved him in ‘Local Hero’,” Shapiro said.

Personally peddling his cinema wares to theater and video chains has Riegert appreciating the irony of schmoozing over a movie whose two main characters are Sol Spivak (Eli Wallach), an ex-door-to-door salesman with a Willy Loman death wish, and his son Leo (Riegert), a newfangled huckster beset by an Oedipal complex.

“I’m turning into Leo and Sol,” a joking Riegert said by phone.

The story revolves around Leo, the dutiful yet resentful son in the midst of an identity crisis that has him questioning everything, including his own religious heritage, and doubting advice given him, especially by his father.

From the very opening, Riegert portrays Leo as a man adrift. Sitting at his office desk, he’s the picture of apathy and narcissism as he sends a parade of wind-up toys marching over the edge into the abyss. This image instantly conveys he’s heading for a similar fall and one he’ll precipitate himself. It’s happens, too, but to Riegert and Shapiro’s credit, the crisis assumes richer, funnier, sadder dimensions than we could imagine.

Continually kvetching about his father wanting to die, his troubled marriage, his rotten job and his willful daughter, Leo acts the meshugina, but he’s really a guilelessmensch short on confidence and, therefore, judgment. More than once, he’s asked, “What do you want?” To his dismay, he doesn’t know.

Where family and colleagues see a protege angling for his job, Leo seems strangely unaware and unfazed by the threat. So depressed is Leo that even when their suspicions prove true, he can’t get angry.

He can’t feel anything, except lost. As men often do, his nonverbalized fears and frustrations drive him to act badly– impulsively pursuing a tryst in a kind of retro-adolescent daze. There’s no question he loves his wife (Isabella Rosselini) and family. But he gives into temptation and reaches for the nearest fix to feel something, anything, again.

In the surreal infidelity sequence Leo revels in his conquest in a most inappropriate way, only to have a moment of self-awareness–too late, as it happens–that’s delicious for how absurd and ashamed he feels.

Riegert has just the right ironic detachment, sardonic bemusement, pragmatic charm, cockeyed whimsy and simmering venom to make his character one we can both laugh at and empathize with. It turns out Leo is a lot like Shapiro.

The actor’s career revolves around New York and L.A., but his many ties here extend to filmmaker Joan Micklin Silver, a native Omahan based in New York. He first worked with her as the wry friend to John Heard in her Chilly Scenes of Winter and next as stand-up Sam, the lovelorn pickle man (opposite Amy Irving), in her Crossing Delancey. For his new film, he’s teamed with transplanted Nebraskan Shapiro, whose book Bad Jews and Other Stories supplied the plot and characters adapted into King of the Corner.

The film falls into that cinema limbo where many good, small, character-driven movies, either owing to limited distribution or poor studio marketing, end up, which is anywhere but your local cineplex. As unusual as it may seem for someone to make the circuit with their picture, “it’s not an uncommon thing,” Riegert said, for moviemakers “to be out there hustling their film. (John) Cassavetes did it. I’m pretty sure Mel Brooks did it with ‘The Twelve Chairs’. I’ve met lots of indie directors who do it.”

Indeed, Joan Micklin Silver and her producer-husband Raphael Silver made the rounds with her Oscar-nominated feature debut Hester Street and again with Between the Lines. If you want your film shown in theaters, self-distribution is the only route left when your pic fails to win a traditional studio release, as was the case with King. It’s not something entered into lightly, but Riegert almost sounds fortunate when he says, “Basically, I’ve had to learn every part of making movies”–from producing to writing-directing to marketing.

“I didn’t want to distribute the movie myself, but I didn’t find the help I felt the movie needed. I didn’t want somebody to just release it. I needed somebody to nurture it, because it’s that kind of a movie, and nobody was stepping up in any particularly enthusiastic way. So, now I’m learning about every part of movies, and in a way that’s not only theoretical but practical.”

The experience should inform whatever project he directs next. His efforts to get his film more widely seen were bolstered when a national chain took it on.

“I booked the first three months of the tour and then Landmark Theaters, which specializes in independent films, picked me up for June, July, August and September,” he said. “So, that was a big help and a nice endorsement in terms of their confidence. In general, the reviews have been very good and people have been coming out to support the film. We’ve been held over in Chicago, Detroit, Buffalo, San Francisco. What I believed, which is that there’s an audience for the movie, has proven true. So, I’m seeing there is some kind of word of mouth.”

Yes, there’s a nice little buzz about it, but to do any real business–the kind that gets Hollywood’s attention –a big fat exploitation campaign is called for, which is just what Riegert and Elevation Filmworks can’t afford.

“What I’ve learned is that as valuable as word of mouth is, you have to help it along and that’s where a marketing budget comes in. I essentially don’t have one. I don’t have the clout to buttress it with advertising support and I can’t get national press for it” without it being in theaters everywhere.

Minus a wide release and cushy press junket, he pushes King “one city at a time.” On the other hand, he gets to know its audience more intimately than he would otherwise. For example, he conducts Q & As after select screenings. He said he enjoys “my conversations with audiences,” adding the sessions have “reinforced my instinct” about the film resonating with people.

As much as he believes in his film, he knows its real worth will be measured by box office-rental-pay-per-view dollars and by how it stands up over time.

“Anybody who makes a film, or makes anything for that matter, has to have a certain kind of crazy courage or arrogance about it,” he said. “You have to believe in yourself. The audience eventually tells you whether you’re right or wrong. And then, of course, time really tells you whether you’re right or wrong.”

Last winter, Riegert’s road show took him to Lincoln, where King played the Mary Riepma Ross Media Arts Center (His picture has yet to be screened in Omaha.). The visit brought Riegert and his project full circle. His appearance there a few years before, for a screening of his own By Courier, proved fortuitous as it was then he was first introduced to Shapiro’s work. The author got someone to slip the actor a copy ofBad Jews. The stories struck a chord in Riegert.

“The title made me laugh out loud and I thought if the book is half as funny as the title then maybe I’ve found what I was looking for, which was material for a feature. I read the book on a plane back to L.A., where I was working, and just thought this guy is fantastic. I called him up the next day and began a process of collaborating.”

Directing is something Riegert’s longed to do since college, when he made a promising short film. When his acting career took off, years passed before he realized he hadn’t followed up on his passion. By Courier was his “if I don’t do it now, I’m never going to do it” project.

In Shapiro, Riegert found an artist with a shared world view that sees “the sense of outsidedness many of us feel” and “how we’re the engineers of our own problems.” He also admires Shapiro’s appreciation for how “the drama and comedy in our respective lives co-exist at the same time, which is what I think makes his material so rich.” Shapiro said the two share “a dry sense of humor. I think both Peter and I tend to laugh at things that are not especially funny. There’s something so Jewish about that as well. But where he’s more optimistic, I’m gloomier.”

In the end, Shapiro feels King stands alone as more Riegert’s vision than his own. “I think it has its own voice and its own validity,” he said. “To be perfectly honest, what it captures is Peter’s voice, and that’s how it should be, because he is the author of that film. The thing I learned from watching this film get made is the director really is the author of the film, and in the case of ‘King of the Corner’, it’s Peter’s movie from top to bottom. His vision and his voice are everywhere.”

For Shapiro, the experience of writing the film entailed a series of firsts. It was his first screenplay, collaboration and adaptation.

“I’m not used to working with anyone. I’m not used to hearing someone else’s input or having someone listen to me. So, that was strange. Not having the tool of narrative to work with as a writer–having to have everything visual or come out of someone’s mouth–it’s a huge difference. My voice as a fiction writer is much more than my dialogue. Most useful to me with ‘King of the Corner’ were the staged readings Peter arranged in New York and Los Angeles that I attended. It’s wonderful to hear the screenplay read aloud by talented actors before a live audience, especially if you’re writing comedy. You get to hear if the jokes work. You get to hear the pacing. Because that’s really what a lot of it is hinging on.”

Many of the actors at those readings wound up in the film, including Eli Wallach, Beverly D’Angelo, Harris Yulin and Eric Bogosian.

As funny as it is, the film’s humor springs from heavy, Death of a Salesman themes. Sol’s bitter over a life spent lived out of cars and motels, schlepping a heavy case to support his family. He bears Leo’s disdain and rues his only child’s weakness. Leo shrinks at the notion he’s anything like his dad. Despite an office, a three-piece suit, a fancy title and his focus groups, he’s ultimately a peddler, too.

In his wallowing Leo recalls the bad times. It’s only much later, after his dad’s gone, he looks past the negative to see a more balanced truth.

Near the end, there’s a marvelous monologue, lifted nearly verbatim from Shapiro’s book, in which Leo delivers a raw, hilarious excoriation of his “crummy” Jewish roots. Riegert said the intent was to make Leo’s from-the-gut rant as unvarnished as possible.

Perhaps the most moving scene is the funeral service. Sol’s died a most unflattering death. Leo’s given the freelance rabbi with the silly name, Evelyn Fink, nothing but dirt to say about the old man. Fink runs Sol down so much even Leo’s offended. Finally, he can’t take it anymore and launches into an impromptu kaddish that’s equal parts confessional and atonement. In a sad-comic soliloquy, Leo properly memorializes his father, poignantly coming to terms with the man and his legacy, which is to say, himself.

At the end, Leo’s found himself again. Even though his fate’s unclear, he can dare to dance his troubles away.

The film’s charm is that it’s so real in adeptly showing the fine edge in comedy-pathos, levity-gravity, absurdity-profundity, and how we slip so easily from one to the other. It helps that all the actors underplay their roles in the naturalistic style Riegert prefers. “What I knew as an actor I’m now becoming more confident in as a director and writer,” he said, “which is to let go of whatever control I think I have and just let my imagination loose and figure out what it means later.”

While Riegert searches for his next directing project, Shapiro’s shopping around a new script, drawn from both his novella Suskind: the Impresario, and Bad Jews. The story focuses on a PR man in San Francisco (where Shapiro once lived) struggling with his job, his estranged family and the new woman in his life.

“It’s a comedy,” he said. Producers are reading it, but Shapiro, like Leo, isn’t one to boast. “I’m amazed anybody would ever want to do anything with anything I wrote. I’ve not had the kind of success that leads to the raging self-confidence I see in other people.”

Related articles

- Why I love Joan Micklin Silver (bookpod.wordpress.com)

- ‘White Irish Drinkers’ captures Irish Bay Ridge in intimate flick (nydailynews.com)

- John Gray’s ‘White Irish Drinkers’ (movies.nytimes.com)

With his new novel, “The Coffins of Little Hope,” Timothy Schaffert’s back delighting in the curiosities of American Gothic

©by Leo Adam Biga

This is a longer version of the story that appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The widowed matriarch of a broken family in a small ag town barely hanging on, Essie’s the local sage whose inquisitiveness and intuition make her the apt, if sometimes prickly narrator for this rural gothic tale of faith on trial.

Schaffert, founder-director of the Omaha Lit Fest and a University of Nebraska-Lincoln lecturer in creative writing and creative nonfiction, has a predilection for idiosyncratic characters. Their various obsessions, compulsions and visions seem magnified or anointed somehow by the backwoods environs. He knows the territory well — having grown up in Nebraska farm country.

His keen observations elevate the ordinary conventions of small town life into something enchanted and surreal. Even desperate acts and heartbreaking loss are imbued with wonder amid the ache. Joy and humor leaven the load.

Schaffert satirically sets off his beguiling characters and situations with a sweetness that’s neither cloying nor false. His stories remain grounded in a subtly heightened reality.

He says, “I don’t know why I’m surprised when people find the stories quirky or perverse, although certainly I’m aware of it as I’m writing it. But I don’t think they’re absurd and they’re certainly not held up for ridicule. You don’t want it to be a cartoon.

“But it is definitely filtered through imagination. I guess it feels a little bit like magical realism without the magic because, yeah, pretty much anything that happens in the book could actually happen. I mean, there’s no one levitating, there’s nothing of the supernatural really occurring.”

His first two novels, The Phantom Limbs of the Rollow Sisters and The Singing and Dancing Daughters of God, trained his whimsy on the bucolic nooks and crannies of the Great Plains.

After a change of course with Devils in the Sugar Shop, whose wry, winking bacchanal of misdeeds was set in the big city — well, Omaha — he’s returned to mining the curious back roads of America’s hinterland in Coffins.

The hamlet of the story stands-in for Small Town USA at the micro level and American society at the macro level. Essie’s our guide through the story’s central riddle: A local woman named Daisy claims a daughter, Lenore, has been abducted by an itinerant aerial photographer. Trouble is, there’s no evidence she ever existed. The facts don’t prevent the tale from captivating the local community and the nation.

Schaffert says he agonized if the narrative should explain the enigma or not.

“A problem I had writing the book was needing to figure out whether I needed to offer a solution, whether the book needed to come to a conclusion or something definitive about how Daisy came to have these delusions, and I went back and forth about that.

“There are some earlier versions where there is a kind of extended explanation and in talking to my editor it became clear that that was just too complicated or it was just sort of muddying things, which was a great relief actually. It was a great relief to know I didn’t have to…So there is nothing definitive — it’s not a mystery solved in a sense.”

He says he was interested in writing about “how invested people get into situations that have nothing to do with them and how they adopt other people’s predicaments and apply them to their own conditions,” adding, “That’s the nature of community.” And of the human condition he might have mentioned.

People resist disowning narratives, no matter how far-fetched. Second-guessing themselves becomes a kind of existential self-mortification that asks:

“If I stop believing in her, what have I done? What kind of philosophical crime have I committed against my own belief system or the belief system of the community? And then there’s the what-if,” says Schaffert. “If I stop believing in this horrible thing that might have happened then what does it say about the fact I ever believed in it, and what does it say about the potential for mystery? Which is the other thing, I mean we trust in mystery and we rely upon it, it informs our daily lives — the unknowable.”

Rumors, myths, legends take on a life all their own the more attention we pay to them.

“What I’m really looking at is how a community responds to a tragedy or a crime or an eccentricity that has far reaching consequence,” he says. “And we do see that happening, we see it on the news, we see this kind of perversion or distortion of the tragedy. It’s treated as entertainment, it’s fed back to us in the same way the movies are, with these narratives produced around them. They are promoted and we are led along. The newscasters want us to tune in to find out what happened in this particular grisly situation, and as soon as we lose interest then they move onto something else.

“That’s existed as long as news has existed — that conflict and cultural condemnation we attach to the news as feeding off tragedy and how delicate that balance is and how poised for catastrophe it is. So, that’s definitely part of my interest in pursuing that plot.”

Essie’s grandon, Doc, editor-publisher of the local County Paragraph, feeds the frenzy with installments on the grieving Daisy and the phantom Lenore. Readership grows far beyond the county’s borders. Essie’s obits earn her a following too. Her fans include a famous figure from afar with a secret agenda.

As the Lenore saga turns stale, even unseemly in its intractable illogic, Doc comes to a mid-life crisis decision. He and Essie have raised his sister Ivy’s daughter, Tiff, since Ivy ran away from responsibility. But with Ivy back to assume her motherly role, the now teenaged Tiff maturing and Essie getting on in years, Doc takes action to restore the family and to put Lenore to rest.

Coffins ruminates on the bonds of family, the power of suggestion, the nature of faith and the need for hope. It has a more measured tone then Schaffert’s past work due to Essie, the mature reporter — the only time he’s used a first-person narrator in a novel.

The first-person device, says Schaffert, “carries with it a somewhat different approach –definitely a voice that’s perhaps different than the narrative voice I’ve used before, because it has to be reconciled with her (Essie’s) own experience. And she’s spent her life writing about death, and now her own life nears its end and so as a writer you have a responsibility to remain true and respectful of that. So, yeah, I think her age brought a kind of gravity to the narration. The last thing you want is for it to be a lampoon. You don’t want it to be a missing child comedy.”

It goes to reason then Essie’s the sober, anchoring conscience of the book.

“And that has to work in order for the novel to work,” says Schaffert. “That what she tells us at the beginning of the novel is true, that she’s recording what she heard, that she’s paid attention, that people trust her. So that when we do get to a scene and she does get into the minds of other characters and she describes scenes she didn’t witness, you don’t want the reader questioning the veracity of that description. You don’t want some sort of metaphysical moment where you’re trying to figure out the narrator’s relationship to the scene or material.”

Having a narrator who chronicles lives already lived and lives still unfolding appealed to Schaffert’s own storytelling sensibilities.

“It’s a great wealth of experience and information and knowledge and insight,” he says. “I think it was Alex Haley who said once, ‘When an old person dies, it is like a library burning.’ The older you get the more you recognize that there’s just a million lives around us that have these incredible rich histories and experiences, anyone of which would make a great novel.”

Schaffert did not set out to write a first-person narrative.

“It just kind of happened that way,” he says. “I mean, I definitely had the plot in mind and some of the characters and what I wanted to happen, but I couldn’t quite get started because I didn’t really know where to start. And so I one day just started writing and it was in the first person, but I didn’t know who the narrator was. I figured that out shortly thereafter and even as I kind of wrote the first draft I still didn’t feel I knew her (Essie)that terribly well because she was speaking more in the third person.

“It was really in revision that I figured out how prominent she needed to be in the book and that if she was going to be the narrator it really needed to be her story, in her voice, so once I figured that out it then it came together in my mind.”

He admires Essie’s grit.

“She has a sense of herself of having a particularly special gift for writing about the dead, and she takes that very seriously. She’s not at all self-deprecating and I like that about her. She recognizes her importance to the community and the importance of the newspaper, which she really fights for.”

Before Essie became paramount on the page, he says Doc and Tiff took precedence. As an amateur magician Doc’s long pressed Tiff into service as his assistant. Doc, the surrogate parent, is tempted to keep her a child in the magic box they use in their act.

“One of the earliest images I had for the book was Tiff outgrowing the magic box,” says Schaffert. “I read something about a woman who worked as a magician’s assistant and she had done this trick in this box until she couldn’t fit into it anymore, and that seemed sort of profound to me and fit so perfectly this relationship between Doc and Tiff.”

The tension of growing up, holding on, letting go, he says, “seems to be a theme I keep returning to — these delicate relationships between parents and children. When these various losses occur long before the child leaves the nest it means these constant renegotiations parents have to do in their relationships with their children. And when it’s happening at the same time as renegotiating other relationships, it seems often an impossible situation.”

Related Articles

- Heartland of Darkness: Timothy Schaffert’s Midwestern Trilogy (themillions.com)

- Books of The Times: The Obituary Writer Has the Upper Hand (nytimes.com)

- What People Magazine is Reading This Week (May 16th Issue) (kindlereader.blogspot.com)

- Reviewing the Reviewers: Catch Up on Your Reading Now That Your Taxes are Done Edition (omnivoracious.com)

Omaha native Steve Marantz looks back at city’s ’68 racial divide through prism of hoops in new book, “The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central”

Omaha native Steve Marantz looks back at city’s ’68 racial divide through prism of hoops in new book, “The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

America’s social fabric came asunder in 1968. Vietnam. Civil rights. Rock ‘n’ roll. Free love. Illegal drugs. Black power. Campus protests. Urban riots.

Omaha was a pressure cooker of racial tension. African-Americans demanded redress from poverty, discrimination, segregation, police misconduct.

Then, like now, Central High School was a cultural bridge by virtue of its downtown location — within a couple miles radius of ethnic enclaves: the Near Northside (black), Bagel (Jewish), Little Italy, Little Bohemia. A diverse student population has enriched the school’s high academic offerings.

Steve Marantz was a 16-year-old Central sophomore that pivotal year when a confluence of social-cultural-racial-political streams converged and a flood of emotions spilled out, forever changing those involved.

Marantz became a reporter for Kansas City and Boston papers. Busy with life and career, the ’68 events receded into memory. Then on a golf outing with classmates the conversation turned to that watershed and he knew he had to write about it.

“It just became so obvious there’s a story there and it needs to be told,” he says.

The result is his new book The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central: High School Basketball and the ’68 Racial Divide (University of Nebraska Press).

Speaking by phone from his home near Boston, Marantz says, “It appealed to me because of the elements in it that I think make for a good story — it had a compact time frame, there was a climatic event, and it had strong characters.” Besides, he says sports is a prime “vehicle for examining social issues.”

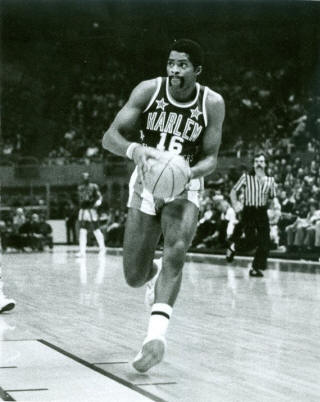

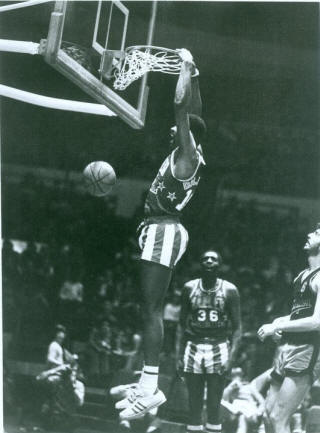

Conflict, baby. Caught up in the maelstrom was the fabulous ’68 Central basketball team, whose all-black starting five earned the sobriquet, The Rhythm Boys. Their enigmatic star, Dwaine Dillard, was a 6-7 big-time college hoops recruit. As if the stress of such expectations wasn’t enough, he lived on the edge.

At a time when it was taboo, he and some fellow blacks dated white girls at the school. Vikki Dollis was involved with Dillard’s teammate, Willie Frazier. In his book Marantz includes excerpts from a diary she kept. Marantz says her “genuine,” “honest,” angst-filled entries “opened a very personal window” that “changed the whole perspective” of events for him. “I just knew the vague outlines of it. The details didn’t really begin to emerge until I did the reporting.”

Functionally illiterate, Dillard barely got by in class. A product of a broken home, he had little adult supervision. Running the streets. he was an enigma easily swayed.

Things came to a head when the polarizing Alabama segregationist George Wallace came to speak at Omaha’s Civic Auditorium. Disturbances broke out, with fires set and windows broken along the Deuce Four (North 24th Street.) A young man caught looting was shot and killed by police.

Dillard became a lightning rod symbol for discontent when he was among a group of young men arrested for possession of rocks and incendiary materials. This was only days before the state tournament. Though quickly released and the charges dropped, he was branded a malcontent and worse.

White-black relations at Central grew strained, erupting into fights. Black students staged protests. Marantz says then-emerging community leader Ernie Chambers made his “loud…powerful…influential” voice heard.

The school’s aristocratic principal, J. Arthur Nelson, was befuddled by the generation gap that rejected authority. “I think change overtook him,” says Marantz. “He was of an earlier era, his moment had come and gone.”

Dillard was among the troublemakers and his coach, Warren Marquiss, suspended him for the first round tourney game. Security was extra tight in Lincoln, where predominantly black Omaha teams often got the shaft from white officials. In Marantz’s view the basketball court became a microcosm of what went on outside athletics, where “negative stereotypes” prevailed.

Central advanced to the semis without Dillard. With him back in the lineup the Eagles made it to the finals but lost to Lincoln Northeast. Another bitter disappointment. There was no violence, however.

The star-crossed Dillard went to play ball at Eastern Michigan but dropped out. He later made the Harlem Globetrotters and, briefly, the ABA. Marantz interviewed Dillard three weeks before his death. “I didn’t know he was that sick,” he says.

Marantz says he’s satisfied the book’s “touched a chord” with classmates by examining “one of those coming of age moments” that mark, even scar, lives.

An independent consultant for ESPN’s E: 60, he’s rhe author of the 2008 book Sorcery at Caesars about Sugar Ray Leonard‘s upset win over Marvin Hagler and is working on new a book about Fenway High School.

Marantz was recently back in Omaha to catch up with old Central classmates and to sign copies of Rhythm Boys at The Bookworm.

|

|

|

Related articles

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Big Bad Buddy Miles (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omowale Akintunde’s In-Your-Face Race Film for the New Millennium, ‘Wigger,’ Introduces America to a New Cinema Voice (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

A Shameless Plug: Lit Coach Erin Reel Highlights this Site, leoadambiga.wordpress.com, aka Leo Adam Biga’s Blog, Among Her Picks for Blogs That Work

A Shameless Plug: Lit Coach Erin Reel Highlights this Site, leoadambiga.wordpress.com, aka Leo Adam Biga’s Blog, Among Her Picks for Blogs That Work

©by Erin Reel from her blog site, The Lit Coach’s Guide to the Writer’s Life (http://thelitcoach.blogspot.com/)

The best blogs serve a purpose greater than sharing miscellaneous tid bits about the blogger’s day – they educate, inform, inspire, humor, enlighten – they share a unique perspective.

Today’s Blog That Works spotlight shines on Leo Adam Biga, Omaha‘s most prolific award-winning cultural journalist. Biga’s eclectic body of work spans from Omaha filmmaker Alexander Payne (Sideways; About Schmidt) tofashion and film making to Warren Buffett and just about everything in between. Rather than collect his published pieces in files, unexposed to new readers, Biga collected his published work and archived them on his blog. Why? To gain new readers and showcase his body of work to prospective clients.

Here’s what Biga had to say:

“My blog is primarily intended as a showcase of my cultural journalism. I want the visitor to the site to experience it the way they would a gallery featuring my work. This exhibition or sampling quickly reveals my brand — “I write stories about people, their passions, and their magnificent obsessions” — as well as the scope of my work within that brand, which is quite broad and eclectic. The home page features 10 of my stories, each in their entirety, and those front page stories, which change every few days or weeks, consistently reflect the wide range of interests, subjects, and themes found on the blog. The blog is set up so that whether the visitor is on the home page or clicks on to any page featuring an individual story the entire inventory or index of stories on the blog is always accessible, organized by tags, categories, et cetera. Visitors can also search the site by using key words.

And Leo tells me showcasing his body of work blog style has allowed those interested in hiring Biga for new writing gigs has allowed them to get a good feel for his writing. He’s received more offers to write than if he hadn’t set up the blog as his massive online writing brochure.

Leo goes on to say, “The real satisfaction I suppose comes in having a public gallery of my work, even if it only is a small sampling of it, that I can refer or direct people to or that people can discover all on their own. In fact, it appears as if the vast majority of visitors to my site end up there by virtue of Web searches they do and their finding links to my blog as part of the search results that come up. Because I have so many stories out there on so many different topics my blog shows up as part of an endless variety of searches. It’s also kind of fun to have people I wrote about, in some cases years ago, find stories I did about them and contact me, reliving old times or bringing me up to date with what they’re doing today. ”

Check out Leo’s blog. There really is something for every reader.

Related Articles

- 10 Ways to Keep Visitors Coming Back to Your Blog (performancing.com)

- 10 Ways To Promote Your Blog Giveaways (bloggingot.com)

- Unique Content: The Key to Online Relationship Building, Social Media and SEO (windmillnetworking.com)

- The Different Avenues of Building Traffic (iblogzone.com)

Letting 1,000 Flowers Bloom: The Black Scholar’s Robert Chrisman Looks Back at a Life in the Maelstrom

Six years ago a formidable figure in arts and letters, Robert Chrisman, chaired the Department of Black Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The mere fact he was heading up this department was symbolic and surprising. Squarely in the vanguard of the modern black intelligentsia scene that has its base on the coasts and in the South, yet here he was staking out ground in the Midwest. The mere fact that black studies took root at UNO, a predominantly white university in a city where outsiders are sometimes amazed to learn there is a sizable black population, is a story in itself. It neither happened overnight, nor without struggle. He came to UNO at a time when the university was on a progressive track but left after only a couple years when it became clear to him his ambitions for the academic unit would not be realized under the then administration. Since his departure the department had a number of interim chairs before new leadership in the chancellor’s office and in the College of Arts and Sciences set the stage for UNO Black Studies to hire perhaps its most dynamic chair yet, Omowale Akintunde (see my stories about Akintunde and his work as a filmmaker on this blog). But back to Chrisman. I happened to meet up with him when he was in a particularly reflective mood. The interview and resulting story happened a few years after 9/11 and a few years before Obama, just as America was going Red and retrenching from some of its liberal leanings. He has the perspective and voice of both a poet and an academic in distilling the meaning of events, trends, and attitudes. My story originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com) and was generously republished by Chrisman in The Black Scholar, the noted journal of black studies for which he serves as editor-in-chief and publisher. It was a privilege to have my story appear in a publication that has published works by Pulitzer winners and major literary figures.

Robert Chrisman

Letting 1,000 Flowers Bloom: The Black Scholar’s Robert Chrisman Looks Back at a Life in the Maelstrom

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) and republished with permission by The Black Scholar (www.theblackscholar.org)

America was at a crossroads in the late 1960s. Using nonviolent resistance actions, the civil rights movement spurred legal changes that finally made African Americans equal citizens under the law. If not in practice. Meanwhile the rising black power movement used militant tactics and rhetoric to demand equal rights — now.

The conciliatory old guard clashed with the confrontational new order. The assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy seemed to wipe away the progress made. Anger spewed. Voices shouted. People marched. Riots erupted. Activists and intellectuals of all ideologies debated Black America’s course. Would peaceful means ever overcome racism? Or, would it take a by-any-means-necessary doctrine? What did being black in America mean and what did the new “freedom” promise?

Amid this tumult, a politically-tinged journal called The Black Scholar emerged to give expression to the diverse voices of the time. Its young co-founder and editor, Robert Chrisman, was already a leading intellectual, educator and poet. Today he’s the chair of the University of Nebraska at Omaha (UNO) Department of Black Studies. The well-connected Chrisman is on intimate terms with artists and political figures. His work appears in top scholarly-literary publications and he edits anthologies and collections. Now in its 36th year of publication, The Black Scholar is still edited by Chrisman, who contributes an introduction each issue and an occasional essay in others, and it remains a vital meditation on the black experience. Among the literati whose work has appeared in its pages are Maya Angelou and Alice Walker.

From its inception, Chrisman said, the journal’s been about uniting the intellectuals in the street. “We were aware there were a lot of street activists-intellectuals as well as academicians who had different sets of training, information and skills,” he said. “And the idea was to have a journal where they could meet. By combining the information and initiative you might have effective social programs. That was part of the goal.”

Another goal was to take on the core issues and topics impacting African Americans and thereby chart and broker the national dialogue in the black community.

“We were aware there was a tremendous national debate going on within the black community and also within the contra-white community and Third World community on the forward movement not only of black people in the United States but also globally and, for that matter, of white people. And so we felt we wanted to register the ongoing debates of the times with emphasis upon social justice, economic justice, racism and sexism.

“And then, finally, we wanted to create an interdisciplinary approach to look at black culture and European-Western culture. Because one of the traditions of the imperialist university is to create specialization and balkanization in intellectuals, rather than synthesis and synergy. We felt it would be contrary to black interests to be specialists, but instead to be generalists. And so we encouraged and supported the interdisciplinary essay. We also felt critique was important. You know, a long recitation of a batch of facts and a few timid conclusions doesn’t really advance the cause of people much. But if you can take an energetic, sinewy idea and then wrap it and weave it with information and build a persuasive argument, then you have, I think, made a contribution.”

No matter the topic or the era, the Scholar’s writing and discourse remain lively and diverse. In the ’60s, it often reflected a call for radical change. In the 1970s, there were forums on the exigencies of Black Nationalism versus Marxism. In the ’80s, a celebration of new black literary voices. In the ’90s, the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill imbroglio. The most recent editions offer rumination on the Brown versus Board of Education decision and a discussion on the state of black politics.

“From the start, we believed every contributor should have her own style,” Chrisman said. “We felt the black studies and new black power movement was yet to build its own language, its own terminology, its own style. So, we said, ‘let a thousand flowers bloom. Let’s have a lot of different styles.’”

But Chrisman makes clear not everything’s dialectically up for grabs. “Sometimes, there aren’t two sides to a question. Period. Some things are not right. Waging genocidal war is not a subject of debate.”

The Meaning of Things

In an essay refuting David Horowitz’s treatise against reparations for African Americans, Chrisman and Ernest Allen, Jr. articulate how “the legacy of slavery continues to inform institutional as well as individual behavior in the U.S. to this day.” He said the great open wound of racism won’t be healed until America confronts its shameful part in the Diaspora and the slave trade. Reparations are a start. Until things are made right, blacks are at a social-economic disadvantage that fosters a kind of psychic trauma and crisis of confidence. In the shadow of slavery, there is a struggle for development and empowerment and identity, he said.

“Blacks produce some of the most powerful culture in the U.S. and in the world. We don’t control enough of it. We don’t profit enough from it. We don’t plow back enough to nurture our children,” he said. “Part of that, I think, is an issue of consciousness. The idea that if you’re on your own as a black person, you aren’t going to make it and another black person can’t help you. That’s kind of like going up to bat with two strikes. You choke up. You get afraid. Richard Wright has a folk verse he quotes, ‘Must I shoot the white man dead to kill the nigger in his head?’ And you could turn that around to say, ‘Must I shoot the black man dead to kill the white man in his head?’ The difference is that the white man has more power (at his disposal) to deal with this black demon that’s obsessing him.”

In the eyes of Chrisman, who came of age as an artist and intellectual reading Frederick Douglass, W. E. B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Robert Hayden, James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Vladimir Lenin, Karl Marx, Che Guevara, Pablo Neruda, Mao Tse-tung and the Beat Generation, the struggle continues.

“The same conditions exist now as existed then, sadly. In 1965 the Voting Rights Act was passed precisely to protect people from the rip off of their votes that occurred in Florida in 2000 and in Ohio in 2004. Furthermore, with full cognizance, not a single U.S. senator had the courage to even support the challenge that the Congressional Black Caucus made [to the 2000 Presidential electoral process].”Raging at the system only does so much and only lasts so long. In looking at these things, one makes a distinction between anger and ideology,” he said.

“There were a number of people in the 1960s who were tremendously angry, and rightfully so. Once the anger was assuaged … then people became much much status quo. A kind of paretic example is Nikki Giovanni, who in the late ’60s was one of those murder mouth poets. ‘Nigguh can you kill. Nigguh can you kill. Nigguh can you kill a honky …’ At the end of the ’70s, she gets an Essence award on television and she sings God Bless America. On the other hand, you take a fellow like Ray Charles, who always maintained a musical resistance, which was blues. And so when Ray Charles decides to sing — ‘Oh beautiful, for spacious skies …’ — all of the irony of black persecution, black endurance, black faith in America runs through that song like a piece of iron. ‘God shed His grace on thee’ speaks then both to God’s blessing of America and to, Please, God — look out for this nation.”

Chrisman said being a minority in America doesn’t have to mean defeat or disenfranchisement. “I think we are the franchise. Black people, people with a just cause and just issues are the franchise. It’s the alienated, confused, hostile Americans that vote against their own interests [that are disenfranchised],” he said. “Frederick Douglass put it another way: ‘The man who is right is a majority.’”

Just as it did then, Chrisman’s own penetrating work coalesces a deep appreciation for African American history, sociology art and culture with a keen understanding of the contemporary black scene to create provocative essays and poems. Back when he and Nathan Hare began The Black Scholar in ’69, Chrisman was based on the west coast. It’s where he grew up, attended school, taught and helped run the nation’s first black studies department at San Francisco State College. “There was a lot of ferment, so it was a good place to be,” he said. He immersed himself in that maelstrom of ideas and causes to form his own philosophy and identity.

“The main voices were my contemporaries. A Stokley Carmichael speech or a Huey Newton rally. A Richard Wright story or a James Baldwin essay. Leaflets. Demonstrations. This was all education on the spot. I mean, they were not always in harmony with each other, but one got a tremendous education just from observing the civil rights and black power movements because, for one thing, many of the activists were very well educated and very bright and very well read,” Chrisman explained. “So you were constantly getting not only the power of their ideas and so on, but reading behind them or, sometimes, reading ahead of them. And not simply black activists, either. There was the hippy movement, the Haight Ashbury scene, the SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]. You name it.”

When he arrived at San Francisco State in 1968, he walked into a firestorm of controversy over students’ demands for a college black studies department.

“The situation was very tense in terms of continued negotiations between students and administrators for a black studies program,” Chrisman said. “Then in November of 1968, everybody went out on strike to get the black studies program. The students called the strike. Black teachers supported the strike. In January of 1969 the AFL-CIO, American Federation of Teachers, Local 1352, went out also. I was active in the strike all that time as one of the vice presidents of the teachers union. And I don’t think the strike was actually settled until March or April. It’s still one of the longest, if not the longest, in the history of American universities.”

The protesters achieved their desired result when a black studies program was added. But at a price. “I was reinstated, but on a non-tenured track — as punishment or discipline for demonstrating against the administration. Nathan (Hare) was fired,” Chrisman said. “Out of all that, Nathan and I developed an idea for The Black Scholar. Volume One, Number One came out November of 1969. So, we were persistent.”

Voicing a Generation

Chrisman didn’t know it then, but the example he set and the ideas he spread inspired UNO student activists in their own fight to get a black studies department. Rudy Smith, now an Omaha World-Herald photojournalist, led the fight as an NAACP Youth Council leader and UNO student senate member.“We knew The Black Scholar. It was written by people in touch with things. We read it. We discussed it,” Smith said. “They sowed the seeds for our focus as a black people in a white society. It kept us sane. He has to take some of the credit for the existence of UNO’s black studies program.” Formed in 1971, it was one of the first such programs.

The poet and academics’ long, distinguished journey in black arts and letters led him to UNO in 2001. Soon after coming, concerns were raised that the program, long a target of cuts, was in danger of being downsized or eliminated. Chrisman and community leaders, including then-Omaha NAACP president Rev. Everett Reynolds, sought and received assurances from Chancellor Nancy Belck about UNO’s commitment to black studies, and the department has been left relatively unscathed.

Chrisman said the opposition black studies still faces in some quarters is an argument for its purpose and need. “A major function of black studies is to provide a critique of Western and American white society — for all kinds of reasons. One is to apprise people of the reality of the society in the hope that constructive ways will be developed to improve it. Some people say racism doesn’t exist anymore. Well, of course it exists,” he said. “What was struck down were the dejure forms of racism, but not defacto racism.” As an example, he points to America’s public schools, where segregation is illegal but still in place as whites flee to the more prosperous suburbs while poor, urban neighborhoods and schools languish.

“If you look at the expansion of Omaha, you have this huge flow of capital heading west and you have this huge sucking sound in the east, which is the black, Hispanic working-class community that gets nothing. This is a form of structural racism and its consequences, and the ruling class refuses to see it.”

He said integration by itself is not the answer.

“People sometimes confuse integration with equality. Equality is always desirable, but it’s not always achieved with integration.” He said a black studies perspective provides a new way of viewing things. “A function of black studies has always been cultural enrichment, not only for blacks, but also for whites, which is why some of our black studies are required. It also gives people practical information about the nature of black people and institutions. It can be almost like a think-tank of information about the characteristics of a black population that can be put to use by policy makers.”

A new black power movement is unlikely in the current climate of fear and apathy. Chrisman said the public is baffled and brainwashed by the conglomerate media and its choreographed reporting of information that promulgates multi-national global capitalist ideologies. Then there’s the Bush administration’s hard line against detractors.

“This is the most intimidated I’ve seen the American people since the ’50s. People are afraid of being called leftist or disloyal in wartime,” Chrisman said. “Hegemony’s been surrendered to the white establishment. If a movement develops, it will have to be a different movement … and on its own terms. What people need to do is organize at the local level on fundamental local issues and, if necessary, have a coalition or interest group or party which can act as issues come up.”

Related Articles

- Clarence B. Jones: Remembering Ten Black Christian Leaders (huffingtonpost.com)

- The Mecca of Black America (online.wsj.com)

- 14 African American Game Changers That Started as Rhodes Scholars (bossip.com)

- What Happens to a Dream Deferred? Beasley Theater Revisits Lorraine Hansberry’s ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Being Dick Cavett

The recent publication of Dick Cavett‘s new book, Talk Show: Confrontations, Pointed Commentary, and Off-Screen Secrets, is as good enough a reason as any for me to repost some of the Cavett stories I’ve written in the last few years. I’m also using the book’s release as an excuse to post some Cavett material I wrote that hasn’t appeared before on this blog. I’ve always admired this most adroit entertainer and I feel privileged that he’s granted me several interviews. With his new book out, I plan to interview him again. For me and a lot of Cavett admirers he’s never quite gotten the credit he deserves for raising the bar for talk shows, perhaps because almost no one followed his lead in making this television genre a forum for both serious and silly conversation. Cavett never quite caught on with the masses the way his talk-jock contemporaries did, and I’ve always thought it had something to do with his built-in contradiction of being both an egg-head and a stand-up comedian at the same time. The following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) was based on a face-to-face interview I did with him in Lincoln, Neb. in 2009.

Being Dick Cavett

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in a 2009 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

While Johnny Carson’s ghost didn’t appear, visages of the Late Night King abounded in the lobby of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Temple Building.

Carson’s spirit was invoked during an Aug. 1 morning interview there with fellow Nebraska entertainer, Dick Cavett. That night Cavett did a program in its Howell Theatre recalling his own talk show days. Prompted by friend Ron Hull and excerpts from Cavett television interviews with show biz icons, the program found the urbane one doing what he does best — sharing witty observations.

The Manhattanphile’s appearance raised funds for the Nebraska Repertory Theatre housed in the Temple Building. The circa-1907 structure is purportedly haunted by a former dean. Who’s to say Carson, a UNL grad who cut his early chops there, doesn’t clatter around doing paranormal sketch comedy? His devotion to Nebraska was legendary. Only months before his 2005 passing he donated $5.4 million for renovations to the facility, whose primary academic program bears his name.

The salon-like lobby of the Johnny Carson School of Theatre & Film is filled with Carsonia. A wall displays framed magazines — Time, Life, Look — on whose covers the portrait of J.C., Carson, not Christ, graced. Reminders of his immense fame.

A kiosk features large prints of Carson hosting the Oscars and presiding over The Tonight Show, mugging it up with David Letterman. In one of these blow-ups Carson interviews Cavett, just a pair of Nebraska-boys-made-good-on-network-TV enjoying a moment of comedy nirvana together.

It’s only apt Cavett should do a program at a place that meant so much to Carson. They were friends. Johnny, his senior by some years, made it big first. He hired Cavett as a writer. They remained close even when Cavett turned competitor, though posing no real threat. Cavett was arguably the better interviewer. Carson, the better comic.

They shared a deep affection for Nebraska. Carson starred in an NBC special filmed in his hometown of Norfolk. He donated generously to Norfolk causes. Cavett’s road trips to the Sand Hills remain a favorite pastime. Though not an alum, he’s lent his voice to UNL, and he’s given his time and talent to other in-state institutions.

Looking dapper and fit, Panama hat titled jauntily, Tom Wolfe-style, the always erudite Cavett spoke with The Reader about Carson, his own talk show career, his work as a New York Times columnist/blogger, but mostly comedy. In two-plus hours he did dead-on impressions of Johnny, Fred Allen, Katharine Hepburn, Marlon Brando, Charles Laughton. His grave voice and withering satire, intact. He dropped more names and recounted more anecdotes than Rex Reed has had facelifts. Walking from the UNL campus to his hotel he recreated a W.C. Fields bit.

He’s so ingrained as a talking head Cavett’s comedy resume gets lost: writing for Jack Paar, Carson, Merv Griffin; doing standup at Greenwich Village clubs with Lenny Bruce; befriending Groucho Marx. He hosted more talk shows than Carson had wives. He’s had more material published than any comic of his generation.

On the native smarts comedy requires, Cavett said, “comedy is complete intelligence.” He said the best comics “may not be able to quote Proust (you can bet the Yale-educated Cavett can), but there’s an order of genius there that sets them apart. There aren’t very many stupid, inept, dumb comics. There are ones that aren’t very talented and there are the greatly talented, but the comic gift is a real rare order. It doesn’t qualify you to do anything else but that.”

Good material and talent go a long way, but he concedes intangibles like charisma count, too. He said, “Thousands of comics have wondered why Bob Hope was better than they are. What’s he got? I’ve got gags, too.”

For Cavett, “Lack of any humor is the most mysterious human trait. You wonder what life must be like.” He appreciates the arrogance/courage required to take a bare stage alone with the expectation of making people laugh.

“Oh, the presumption. It’s not so bad if the house isn’t bare but that has happened to me too at a club called the Upstairs at the Duplex in the Village, where many of us so to speak worked for free on Grove Street. A great motherly woman named Jan Wallman ran this upstairs-one-flight little club with about seven tables. Joan Rivers worked there. Rodney Dangerfield, Bob Klein, Linda Lavin. Woody (Allen) worked out some material there early on.”

He knows, too, the agony of bombing and that moment when you realize, “I have walked into the brightest lit part of the room and presumed to entertain and make people laugh and I’m doing apparently the opposite.” A comic in those straits is bound to ask, “What made me do this?” The key is not taking yourself too seriously.

“If you can get amused by it that will save you, and I finally got to that point at The Hungry Eye,” he said. “I knew something was wrong because I’d played there for two weeks and been doing alright and then one night, nothing, zero. The same sound there would be if there was no one seated in the place. Line after line. It was just awful. You could see people at the nearest tables gaping up at you like carp in a pool, not comprehending, not laughing, not moving. And I finally just said, ‘Why don’t you all just get the hell out of here?’ It gave me a wonderful feeling.

“Two, what Lenny Bruce used to call diesel dikes sitting in the front row with their boots up on the stage, one of whose boots I kicked off the stage, taking my life in my hands, got up to leave. And as they got to the door I said, ‘There are no refunds,’ and one of them said, ‘We’ll take a chance.’ And she got a laugh. So they (the audience) were capable of laughing.”

He finished his set sans applause, the only noise the patter of his patent leathers retreating. Inexplicably, he said, “the next show went fine. Same stuff.” For Cavett it’s proof “there is such a thing as a bad audience or a bad something — a gestalt, that makes a room full of unfunnyness, and I don’t think it’s you. It might be something in you. Whatever it is, you’re unaware of its source, not its presence.”

Anxiety is the performer’s companion. It heightens senses. It gets a manic edge on.

“Whether you want it, you’re going to get some,” he said. “I can go into a club and perform without any nerves of any kind now. But if it isn’t there you want a little something, and there are ways you can get it. Like be a little late. Or I found with low grade depression, before diagnosed, not knowing what it was, I would do things like go back and rebrush my hair or put another shirt on. ‘This is dangerous, they’re going to be mad,’ I’d think. ‘But that’s alright somehow.’ I didn’t realize the somehow meant it’s giving me adrenalin that lifted the depressed seratonin level. It raises you a little bit above the level of a normal person standing talking to other normal people. It’s a recent realization. I’ve never told that before.”

Cavett was always struck by how Carson, the consummate showman, was so uptight outside that arena. “I’ve said it before, but he was maybe the most socially uncomfortable man I’ve ever known. At such odds with his skills. There are actors who can play geniuses that aren’t very smart seemingly when you talk to them, but whatever it is is in there and it comes out when they work. I have a sad feeling Johnny was happiest when on stage, out in front of an audience. I don’t know that it’s so sad. Most people are sad a lot of the time, but some don’t ever get the thrill of having an ovation every time they appear.”

“It’s funny for me to think there are people on this earth who have never stood in front of an audience or been in a play or gotten a laugh,” he said.

People who say they nearly die of nerves speaking in public reminds him he once did, too. “I had the added problem of every time I spoke everybody turned and looked at me because of my voice. It was always low. If I heard one more time ‘the little fellow with the big voice’ I thought I’d kick someone in the crotch.”

He said performers most at home on stage dread “having to go back to life. For many of them that means the gin bottle on the dresser in a hotel in Detroit. On stage, god-like. Off-stage, miserable.”

In Cavett’s eyes, Carson was a master craftsman.

“He could do no wrong on stage. I mean in monologue. He perfected that to the point where failure succeeded. If a joke died he made it funnier by doing what’s known in the trade as bomb takes — stepping backwards a foot, loosening his tie…’” Not that Carson didn’t stumble. “He had awkward moments while he was out there. Many of them in the beginning. My God, the talk in the business was this guy isn’t making it, he’s not going to last. It’s hard to think of that now. Merv Griffin began in the daytime the same day as Johnny on The Tonight Show. Merv got all the good reviews. He was the guy they said should have Tonight, and Merv really died when he didn’t get it.”

When the mercurial Paar walked off Tonight in ’62 NBC scrambled for a replacement. Griffin “was actually seemingly in line” but the network anointed Carson, then best known as a game show host. In what proved a shrewd move Carson didn’t start right away. Instead, guest hosts filled in during what Cavett refers to as “the summer stock period between Paar and Johnny. People don’t remember that. Everybody and his dog who thought he could host a talk show came out and most of them found out they couldn’t.” Donald O’Connor, Dick Van Dyke, Jackie Leonard, Bob Cummings, Eva Gabor, Groucho. Some were serviceable, others a disaster.

Carson debuted months later to great anticipation and pressure. “At the beginning he was really uncomfortable, drinking a bit I think to ease the pain, and as one of my writer friends said, ‘with a wife on the ledge.’ It was a very, very hard time in his life to have all this happen” said Cavett, “and then he just developed and all this charm came out.”

Off-air is where Carson’s real problems lay. “Many a time I rescued him in the hall from tourists who accidentally cornered him on his way back to the dressing room after the show. They’d made the wrong turn to the elevators and decided to chat up Johnny, and he was just in agony.” The same scene played out at cocktail parties, where Carson hated the banter. It’s one of the ways the two were different. Said Cavett, “I don’t seek it but I don’t mind it. He couldn’t do it and he knew he couldn’t do it and it pained him.”

That vulnerability endeared Carson to Cavett. “I liked him so much. We had such a good thing going, Johnny and I. It dawned on me gradually how much he liked me. I mean, it was fine working for him and we got along well, and when I was doing an act at night he’d ask me how it went, and we’d laugh if a joke bombed. He’d say, ‘Why don’t you change it to this?’ He’d give me a better wording for it. I feel guilty for not seeing him the last 8 or 10 years of his life, though we spent evenings together. The staff couldn’t believe I ate at his house. ‘You were in the house?’ On the phone he was, ‘Richard’ — he always called me Richard, sort of nice — ‘you want to go to the Magic Castle?’ I’d say, ‘Who is this?’ ‘Johnny.’ And I would think somebody imitating him, even though I’d been around him a million times.”

Something Brando once told Cavett — “Because of Nebraska I feel a foolish kinship with you” — applied to Cavett and Carson.

Cavett realized a dream of hosting his own show in ’68 (ABC). In ’69 he went from prime time to late night. A writer supplied a favorite line: “‘Hi, I’m Dick Cavett, I have my own television show, and so all the girls that wouldn’t go out with me in high school — neyeah, neyeah, neyeah, neyeah, neyeah.’ It got one of the biggest laughs. Johnny liked it.”

Getting more than the usual canned ham from guests was a Cavett gift. Solid research helped.

“I often did too much. I’d worry, ‘Oh, God, I’m not going to get to the first, let alone the 12 things I wrote down. Or. ‘I’ve lost the thread again.’ Only to find often the best shows I did had nothing I’d prepared in it. The best advice I ever got, which Jack Paar gave me, was, ‘Kid, don’t ever do an interview, make conversation.’ That’s what Jack did.” A quick wit helps.

At its best TV Talk is a free-flowing seduction. For viewers it’s like peeking in on a private conversation. “Very much so,” he said. “You’d think that can’t be possible because there are lights and bystanders and an audience, and it’s being recorded, and yet I remember often a feeling of breakthrough, almost like clouds clearing. ‘We’re really talking here. I can say anything I want .’”

With superstar celebs like Hepburn, Bette Davis, Robert Mitchum, Orson Welles and his “favorite,” Groucho, Cavett revealed his fandom but grounded it with keen instincts and insights. “That did help. I could see on their faces sometimes, Oh, you knew that about me? I guess I have to confess to a knack of some sort that many people commented about: ‘How did you get me to say those things?’”

He said viewing the boxed-set DVDs of his conversations with Hollywood Greats and Rock Greats reveals “there was a time when nobody plugged anything” on TV. Then everyone became a pimp. “When first it happened it was rare. Then it was joked about,” he said, “and then it got so it was universal — that’s the reason you go on.”

Today’s new social media landscape has him “a bit baffled and bewildered.”

“I have wondered at times what all has changed, what’s so different. It did occur to me the other day looking at the Hollywood Greats DVD — who would be the 15 counterparts today of these people. I might be able to think of three. And that’s not just every generation thinks everything is better in the past than it is now. I know one thing you could start with is the single act that propelled me here — the fact I was able to enter the RCA Building via the 6th Ave. escalators, which were unguarded, and walk up knowing where Paar’s office was, and go to it.”

He not only found Paar but handed him jokes the star used that night on air, netting Cavett a staff writing job. “No career will start that way today,” he said. Then again, some creatives are being discovered via Facebook and YouTube.

In terms of the talk genre, he said, “it doesn’t mean as much to get a big name guest anymore. They’re cheap currency now,” whereas getting Hepburn and Brando “was unthinkable.” He’s dismayed by “how much crap” is on virtually every channel.” He disdains “wretched reality shows” and wonders “what it’s done to the mind or the image people have of themselves that allows them to think they’re still private in ways they’re not anymore.”

Comedy Central is a mixed bag in his opinion. “I like very little of the standup. I don’t see much good stuff. They all are interchangeable to me. They all hold the mike the same and they all say motherfucker the same. You just feel like I may have seen them before or I may not have. And I don’t believe in the old farts of comedy saying ‘we didn’t need to resort to filthy language’ and ‘they don’t even dress well.’ That’s boring, too.”

Cavett’s done “a kind of AARP comedy tour” with Bill Dana, Mort Sahl, Shelley Berman and Dick Gregory. “It was pretty good.” But he’s about more than comedy nostalgia. He enjoys contemporary topical comics Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert and Bill Maher, about whom he said, “he gives as good as he gets and gets as good as he gives.” He’s fine not having a TV forum anymore: “I’ve lived without it and I got what I wanted mostly I guess in so many ways.” Besides, who needs it when you’re a featured Times’ blogger?

“Yeah, I like that, although it can be penal servitude to meet a deadline.”