Grain elevators, not skyscrapers, fill the view outside Paul Serrato’s home now that the jazz pianist-composer is back in Omaha after decades in New York City.

Serrato was a New York sideman, soloist and band leader. When not performing, he haunted clubs to see countless legends play. An avid collector, he helped himself to rare posters of great jazz lineups at iconic spots like the Village Gate in East Harlem.

He also spent untold hours composing and trying out original tunes and arrangements. He’s released nine albums on his Graffiti Productions label. He cut his tenth in February with his regular Big Apple crew. The new CD will have a fall national release.

Serrato also wrote for and accompanied underground cabaret and off-Broadway performers.

Education is a parallel passion for Serrato, who has degrees in music (Harbor Conservatory for the Performing Arts) and urban education (Adelphi University). Since the 1980s he’s taught adult ESL. He taught in various New York boroughs. Since resettling in Omaha five years ago he’s been an adjunct instructor at Metropolitan Community College’s south campus.

“I love teaching ESL. I love working with international students,” he said. “It’s taught me to respect other people, especially immigrants. I’ve always been interested in other cultures, other languages. It was a natural fit for me to migrate to teaching ESL and to pursue it to the end that I have.

“I’m a great believer in bilingual education.”

He’s distressed state funding cutbacks threaten something so impactful for students.

“There’s a tremendous amount of satisfaction in knowing we’re helping them to acculturate-integrate into the larger scene.”

He’s outraged by draconian Trump administration measures against illegal immigrants and by Trump’s own hateful rhetoric on immigration.

Serrato has immigrant students compose essays about their new lives in America. He’s moved by their stories.

“It inspires me that I can guide them and give them an opportunity to release their emotions and feelings. It’s like nobody’s ever asked them before. Some of the papers are so remarkable. They spill it all out – eloquently, too – their feelings about being immigrants, living here, the difficulties, the good things.”

Last year he organized a program at Gallery 72 in which his Omaha students read personal accounts that his New York students wrote in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks that brought down the Twin Towers. Serrato and his NYC students were only a few blocks from ground zero that fateful day. They watched the tragedy unfold before their eyes.

“I had my international adult students write about their impressions of that day. They were from all these different countries. They wrote eloquently about what they witnessed. I saved their essays and decided to turn it into EYEWITNESS: New York Testimonies. Though they all experienced the same event, we hear it filtered through the sensibilities of their diverse cultures.”

Serrato’s “Broadway Electronic” and “Blues Elegy” compositions provided ambient music for the readings.

“I was very proud of how that event turned out. My Metro students did a great job.”

He said the international student mix he teaches “makes me feel like I’m back in New York.”

His cozy southeast Omaha home is a tightly packed trove. Framed posters and album covers adorn walls. Photos of students, family, friends and jam cats are pinned to boards. Stacks of books occupy tables.

His music life began in Omaha, where he showed early muscial aptitude and formally studied piano.

“I began doing talent contests around town. Schmoller & Mueller piano store had a Saturday morning talent show on the radio. I won first prize a couple times.”

The Creighton Prep grad was brought up the son of a single mother who divorced when he was three.

“She was a pretty remarkable woman considering what she had to go through. There were no resources in those days for single moms.”

The Chicano artist has indulged his Latino roots via study and travel. He made pilgrimages to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil to steep himself in boss and samba. His tune “Blues in Rio” originated there. A YouTube video produced by musician friend Donald Mohr features that tune matched with photos from Serrato’s Brazilian sojourns.

Bumming around Europe, he made it to Spain and grew “smitten with bullfighting’s art and pageantry.” “I began returning to Spain annually for the long taurine season as an aficionado. I’d lock up my New York apartment and fly off. My life as an artist’s model and bookstore manager in Greenwich Village made it easily possible. Such was the Boho (bohemian) life.”

His Latino roots music and world jazz immersion influences following a classical music track. He gave recitals in Omaha. Then he heard intoxicating sounds on his family’s short wave radio that changed his life.

“I thought I wanted to be a concert pianist until I started hearing recordings by Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson,

whose records were being spun out of Chicago. I was very like blown away by these great jazz pianists.

“Hearing that stuff opened up a big door and window into other possibilities.”

Harbor Conservatory in Spanish Harlem became his mecca. He earned a bachelor’s degree in music composition with a concentration on Latin music styles.

“It’s like the repository of the jazz and Latin music in New York after the World War II diaspora. It’s an incredible place. You walk into that school and you walk into another world, of Latin jazz music, which I love.”

His intensive study of Spanish has extended to Latin literature and art.

He cites congo player Candido Camero as “a great inspiration.” “He could play anything. Candido made a record, Mambo Moves, with Erroll Garner, one of my favorite pianists. They play such great duets. I’ve always loved that record. I’ve tried to incorporate some of those ideas into my own music.

“I compose pieces in the bossa style, though filtered through a New York jazz lens.”

Just as Serrato’s never done learning, he’s never done teaching,

“I love education. It’s absolutely vital to me. I’m teaching all the time, as many jazz musicians do. We’re all educators.” Visit www.paulserrato.com.

Visit www.paulserrato.com.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

Archive

Venerable jazzman Paul Serrato has his say

Venerable jazzman Paul Serrato has his say

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the April 2019 New Horizons

Journeyman jazz pianist, composer, arranger and recording artist Paul Serrato has packed much living into 83 years. The accouterments of that long, well-lived life fill to overbrimming the textured South Omaha house he resides in.

The humble dwelling is in the shadow of Vinton Street’s mural-adorned grain silos. They are distant echoes of the skyscrapers of New York, where for decades he plied his trade gigging in clubs and cabarets and writing-performing musical theater shows.

After all that time in Manhattan, plus spending bohemian summers in Europe, he returned to Omaha eight years ago upon the death of his mother. He inherited her snug bungalow and it’s there he displays his lifetime passion for arts and culture. Books, magazines, albums, DVDs, VHS tapes and CDs fill shelves and tables. Photos, prints, posters and artworks occupy walls.

Each nook and cranny is crammed with expressions of his eclectic interests, There’s just enough space to beat a measured path through the house and yet everything is neat and tidy under the fastidious eye of Serrato.

“This is how we live in New York in our cluttered, small apartments,” he said.

In a music room is the Yamaha keyboard he composes on and gigs with as well as manuscripts of completed and in-progress instrumental works. Though he’s recorded many CDs released on his own record labels, many of his tunes have never been made public.

“I couldn’t bring it all out. That’s how it is for any artist.”

His latest release “Gotham Nights” on his Graffiti Productions label has charted nationally since January.

Some of his catalogue is licensed for television. He finds it “exciting” to hear his music on TV or radio. Tracks from “Gotham Nights” have aired on the nationally syndicated “Latin Perspective” public radio program.

Serrato has made provisions for his archives to go to his alma mater, Adelphi University, when he dies.

“They’ve been very supportive, very receptive about accepting my archives,” he said.

His home contains reminders of his second career teaching English as a Second Language to international students, including photos and letters from former students with whom he corresponds. All these years teaching immigrants and refugees, combined with his many travels, gives Serrato friends in faraway places.

“It’s really wonderful,” he said. “I’m very fortunate. We keep in touch. We send each other gifts . I have more close friends around the world than I do in Omaha.”

A friendship with a former student from Japan led to Serrato making two concert tours of the Asian nation.

He began working as an ESL instructor long ago in New York. He earned a master’s degree in Urban Education from Adelphi. He now teaches ESL for Metropolitan Community College in Omaha.

Coming of age

Serrato’s always shown an aptitude for learning. Growing up, he was drawn to the big upright piano his aunt played in church. It wasn’t long before he gained proficiency on it.

“I can remember myself so distinctly fascinated by the piano, wanting to play it, going over and pounding on the keys. That’s how I got to playing the piano as a toddler. From an educational point of view, it’s interesting how children can gravitate to an environment or a stimulus when they see adults doing things.”

Not being good at sports and not having advantages more well-off kids enjoyed, he said, “Music gave me the confidence I could do something. My early childhood was rather deprived. We moved around a lot. It wasn’t until I was 9 we got settled. My mother bought a piano and paid for classical lessons. She was a pretty remarkable woman considering what she had to go through raising a kid on her own.”

Music gave him his identity at Omaha Creighton Prep.

“I could start to come out as a musician and I found people liked what I did. They applauded. I was like, Hey, man, I’m good, I can do this. That’s how I got started on the track.”

All it took for him to shine was affirmation.

“That’s how it is, that’s how it always is.”

iHe was starved for encouragement, too, coming from a broken family of meager meansHe performed classical recitals and competed in talent shows at school and community centers, even on radio. “I won a couple of first prizes on KOIL” He played on a WOW show hosted by Lyle DeMoss. All of it made him hungry for more.

His classical training then took a backseat to captivating new sounds he heard on jazz programs out of Chicago on the family’s old Philco radio set.

“That was an eye-opener, definitely because at that point I had only studied classical piano – Chopin, Debussy. I hadn’t been exposed to hearing guys like Oscar Peterson or Art Tatum and Erroll Garner. Hearing that stuff opened up a big door and window into other possibilities.”

He began composing riffs on popular song forms, mostly big band and Broadway show tunes.

“That’s what jazz players did and still do – take standard songs and interpret them. That’s the classic jazz repertoire. I still love Cole Porter. I still play his stuff. I have a whole Cole Porter portfolio.”

New York, New York

After high school Serarto’s awakening as an aspiring jazz artist pulled him east. After a stint at Boston University he went to New York. It became home.

Said Serrato, “There’s three kinds of New Yorkers: the native New Yorker who’s born there; the commuter who comes in from Long Island to work or play; then there are those like myself who go there for a purpose – to achieve a goal – and for personal fulfillment. New York draws in all these dynamic young people who go to feed themselves creatively/.”

The sheer diversity of people and abundance of opportunity is staggering.

“You meet people of all different persuasions, professions, everything.

Finding one’s kindred spirit circle or group, he said, “is so easy in New York.” “You don’t find it, it finds you. I made lots of friends. I’d meet somebody in a coffee shop and it would turn out they were producing a play and needed somebody to write music. I’d say, ‘I write music’. ‘Oh, why don’t you do it?’ they’d say.

“For example, I ended up collaborating on many projects with Jackie Curtis, who later became an Andy Warhol superstar. We met at a Greenwich Village bookstore I managed. Totally serendipitous. He was very young. We struck up a conversation. I said, ‘I write songs.’ He said, ‘Oh we could do a musical together.’ We did the first one, O Lucky Wonderful, as an off-off-Broadway production, on an absolute shoestring.”

Serrato worked with other Warhol personalities, including Candy Darling and Holly Woodlawn.

“Some of that material for these crazy talented trans performers and underground figures was rather risque.”

He also teamed with comedian Craig Vandernberg, “who did a great spoof on Las Vegas crooners.”

Whatever work he could find, Serrato did.

“I had different kinds of jobs. I was a bartender, a bouncer, a waiter, an artist’s model. That’s how I supported myself. You have to hustle and do whatever it takes. That’s the driving force. That’s why you’re in New York. That’s why it’s competitive and there’s that energy because you look around and you see what’s possible.

“You’re in the epicenter of the arts. All that stuff was my world – visual arts, performance arts. There’s all this collision of cultural forces and people all interested in those things.”

Serrato believes everyone needs to find their passion the way he found his in music.

“That just happens to be my domain. I tell my students, ‘Hopefully, you’ll find your domain – something you can feel passionate about or connected to that will drive you and give you the energy to pursue that.’ I love to guide young people.”

Everything he experienced in NYC fed him creatively.

“As an artist’s model I met all these wonderful artists and art teachers. That’s when my passion for visual art and painters really got implanted.

When it comes to artistic vocations, he said, “many are called, few are chosen.”

“If you are truly engaged as an artist, you have confidence – you know you’re connecting.”

He eventually did well enough that he “would take off for months in the summer and go to Europe to follow bullfights and go to Paris.” “Then I’d come back and just pick up where I left off.”

“In those days living in New York was not as prohibitive as it is now economically. The rents have since priced a lot of people out.”

On his summer idyls abroad he followed a guide book by author Arthur Frommer on how to see Europe on five dollars a day and, he found, “you could just about do it.”

“His book had all the cheap places you could stay and eat. It worked, man. It was fabulous.”

Always the adventurer, he smuggled back copies of banned books.

|

|---|

All that jazz

Jazz eventually became his main metier. He earned his bachelor’s degree in Jazz Studies and Latin American Music from Harbor Conservatory for the Performing Arts in East Harlem.

Jazz is a truly American art form. Though its following is shrinking, he said the music retains “plenty of vitality.”

“The fact that it’s not mainstream music is probably to its benefit because that means you can be individual, you don’t have a lot of hierarchy breathing down your neck saying do it this way, do it that way. So a jazz artist can sort of be what he or she wants to be.

“It’s a personal expression. It’s not a commodity the way corporately sanctioned music can be.”

A few jazz artists have managed to gain broad crossover appeal.

“But for every artist like that,” he said, “there’s a legion of others like myself that don’t have that kind of profile.

“There’s been such a tectonic shift in the jazz culture. Mid-20th century jazz artists – (Thelonious) Monk, (Dave) Brubeck – used to make the covers of national magazines. Who would put a jazz musician on the cover of a national magazine today? Do you ever see jazz musicians on the late night TV shows? You see rock, pop or hip-hop artists. In a lot of people’s minds, jazz is not that important because it doesn’t make much money and doesn’t get much media attention, so we work however we can. But it’s always been a struggle, even in the golden era.”

The Life can take a toll.

“I remember at the Village Gate in the ’60s. I was house manager and performed there sometimes. You’d have a 2 a.m. show. You had to make it through these gigs. It’s a tough life. No wonder there was alcohol and drugs and everything. It’s always been a tough life.”

Playing by his own rules

Making quality music, not fame, remains Serrato’s ambition. In New York he got tight with similarly-inclined musicians, particularly “master Latin percussionist” Julio Feliciano.

“He was Yorkirican – a New Yorker of Puerto Rican descent. Just full of energy and vitality and ideas. He contributed his deep musicianship to my many recording sessions and New York gigs. We enjoyed that vibe that enables the most successful collaborations. That also includes Jack ‘Kako’ Sanchez. They were a percussion team. It’s evident on my record ‘More Than Red,’ which spent many weeks on the national jazz charts.

“I’ll never find another like Julio. It was like (Duke) Ellington with (Billy) Strahorn – the two of us together. We had a tremendous collaboration. He was a Vietnam vet who OD’d on prescription pain killers. It was tragic. So young, so talented, so brilliant. We were like brothers musically and spiritually.”

What Serrato misses most about New York is “the cultural network” he had there that he lacks here.

“Like I have an idea for a musical project right now. In New York I could just pick up the phone and tell these guys, ‘Come over.’ and they’d come over and we’d start working on it. I can’t do that here. I don’t have that kind of musical infrastructure here.

“My studio in New York was a place where we would try out things. It was wonderful for me as a composer. It taught me a lot of discipline in terms of being accurate and clear about what I write.”

Just as musician Preston Love Sr. found when he returned to Omaha after years away, Serrato’s found his hometown less than inviting when it comes to jazz and to the idea of him performing his music.

“I hear people say things like. ‘We love your music, but it’s very sophisticated. We never hear music like this around here. What do you call it?’ I scratch my head when they say those things. I never get this in New York.”

He turns down some offers because, in true New Yorker fashion, he doesn’t drive and public transportation here can’t easily get him to out-of-town gigs.

“I’m not the first New York creative who left the city and had to make an adjustment somewhere else.”

Some discerning listeners have supported his music, including KIOS-FM.

“They’ve been very good to me.”

He’s cultivated a local cadre of fellow arts nuts. He sees shows when he can at the Joslyn, Kaneko, Bemis, Holland and Orpheum. His best buddy in town is another New York transplant, David Johnson. Their shared sensibilities find them kvetching about things.

What Serrato won’t do is compromise his music. His website says it all: Urban Jazz – Not by the Rules. He’s put out CDs on his own terms since returning to Omaha.

“I’m a music producer – of jazz music in particular. So when I have enough music that I think I’m ready to record, I figure out a way to record it. I don’t really have the network here to feel confident enough to do a project like ‘Gotham Nights’ in Omaha. So I rely on my band members in New York. We’ve played together for years. I want to record with them.”

For “Gotham Nights” he booked two four-hour recording sessions in Manhattan.

“It was so successful because I had everything clearly written. I gave it to my guys and the caliber they are, they saw it, and they played it. I knew these guys so well that we didn’t have to rehearse. I gave them the charts and turned them loose and let them go. We all spoke the same musical language – that’s the most important thing. I had eight instrumental tunes. We went through it once, twice at most.”

“Gotham Nights” marks a change for Serrato in moving from artsy to mainstream.

“In the past I’ve had good success, but sometimes I’ve heard, ‘Oh, your music is too avant garde,’ which is like poison. ‘Gotham Nights’ is not avant garde. It reflects my Brazilian influences. It’s Latin jazz filtered through my own musical personality. Very melodic. It’s why it’s so accessible.”

The album is the latest of many projects he’s done that celebrate his muse, New York, and its many notes.

He was there teaching only blocks from ground zero when the twin towers came down on 9/11.

“We had to vacate our building. After we were allowed back in a few weeks later I had my international adult students write about their impressions of that day. They were from Taiwan, Japan, Turkey, Korea, Chile, all these different countries. They wrote eloquently about that and I saved their essays. Fast forward 15 years later and I asked some of my ESL students in Omaha to read these testimonials set to music I composed at a Gallery 72 event commemorating that tragic day. I was very proud of how that event turned out.”

He’s teaching a new ESL class this spring. As usual, he said, he’s trying “to make it comfortable” for recent arrivals “to adapt to a new culture and a new land.”

“Cultural transference or acculturation – that’s an ESL teacher’s job.”

But his class assignments always encourage students to celebrate their own culture, too.

The ever searching Serrato said, “I love other cultures and I love education. I’m a big believer in bilingual education. Teaching’s been a natural evolution for me. All musicians are educators at heart.”

Fellow hin at http://www.paulserrato.com.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

El Museo Latino: A Quarter Century Strong

El Museo Latino: A Quarter Century Strong

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Omaha’s a livelier place today than 30 years ago because Individuals noted cultural voids and put their passion, reputation or money on the line to create iconic attractions. Blue Barn Theatre, The Waiting Room, Slowdown, Film Streams, Kaneko, Holland Performing Arts Center, Union for Contemporary Art and Gallery 1516 are prime examples.

Count El Museo Latino among the signature venues in this city’s cultural maturation. Founder-director Magdalena “Maggie” Garcia noted a paucity of Latino art-culture-history displays here. Like other place-makers, she didn’t wait for someone else to do something about it. Acting on her lifelong interest in Latino heritage, she left a business career to learn about museums and in 1993 she launched her nonprofit.

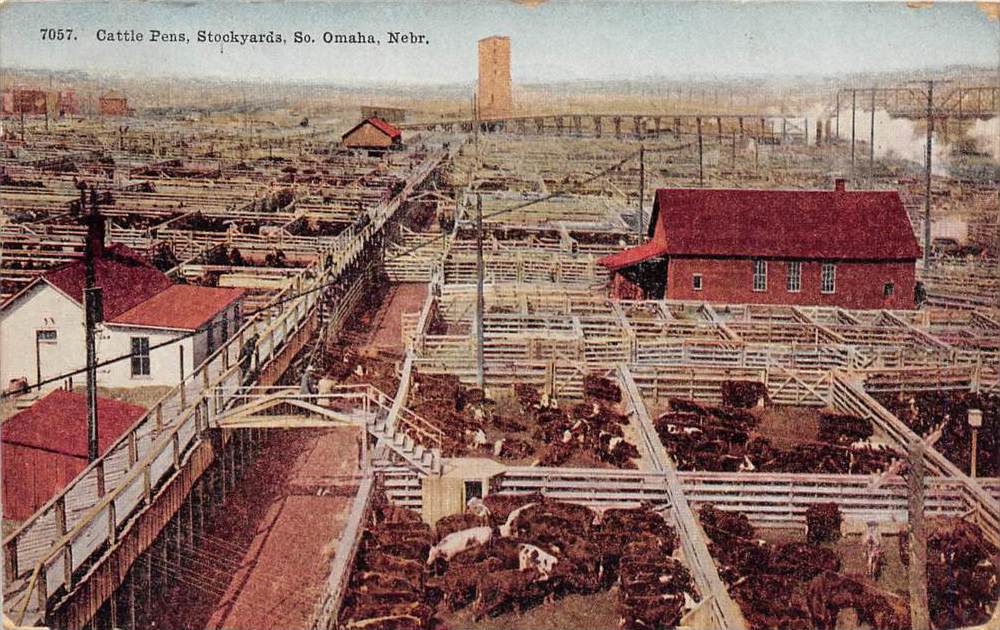

El Museo Latino got its humble start in a 3,000 square foot basement bay of the Livestock Exchange Building. The stockyards were still active, making pesky flies and foul smells a gritty nuisance. Volunteers transformed the grimy old print shop space in 34 days for El Museo Latino to open in time for Cinco de Mayo festivities.

Five years later she led the move from there to the present 18,000 square foot site at 4701 South 25th Street in the former Polish Home. Growth necessitated the relocation. As the museum consolidated its niche, it expanded its number of exhibits and education programs. It hosts events celebrating traditional art, dance, music, film and ethnic food.

The museum launched amidst the South Omaha business district’s decline. It prospered as the area enjoyed a resurgence of commerce – finding community and foundation support. From 1993 till now, Garcia’s nurtured a passionate dream turned fledgling reality turned established institution. In celebration of its 25th anniversary, El Museo Latino is hosting a Saturday, October 13 Open House from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m.

Visitors can view a special contemporary textiles exhibition by Mexican artist Marcela Diaz along with selections from the permanent collection.

A quarter century of presenting national-international traveling exhibits and bringing visiting artists, scholars and curators only happened because Garcia didn’t let anything stop her vision. She didn’t ask permission, She didn’t heed naysayers who said Omaha didn’t need another museum. She didn’t delay her dream for her board to find a more suitable space or to raise money.

“My attitude was, let’s get something established instead of waiting for funding, for a different space, for this or that. I just thought we needed to do it now – and so we went ahead, Besides, who’s going to give us the authority to say what we can have and not?”

Retired University of Nebraska at Omaha arts education administrator Shari Hofschire lays the museum’s very being at the feet of Garcia.

“Maggie Garcia’s passion is the building block of its 25 year history. She doggedly fundraised and programmed. She recognized the need for a community-cultural identity just as South Omaha was growing with new residents.”

Hofschire added the museum’s now “a catalyst for both the past traditions of Latino history and culture and future opportunities for the South Omaha community to express itself and expand its cultural narrative.”

As a founding board member, David Catalan has seen first-hand the transformation of Garcia’s idea into a full-fledged destination.

“Underlying the foundation of El Museo Latino’s success was Maggie’s leadership and outstanding credentials in the arts Her outreach skills harvested financial support in the form of foundation grants and corporate sponsorships,” Catalan said. “Her organizational acumen created a governing board of directors, each with resources necessary for achieving strategic objectives. The museum’s programs and exhibits drew rapid membership growth as well.

“Today, El Museo Latino is a treasured anchor in the cultural and economic development of South Omaha. Another 25 years of sustainability is assured so long as Maggie Garcia continues to be the face of inspiration and guidance.”

Garcia spent years preparing herself for the job. She performed and taught traditional folk dance. She collected art. She met scholars, curators and artists on visits to Mexico. After earning an art history degree, she quit her human resources career to get a master’s in museum studies and to work in museums. Seeing no Latino art culture, history centers in the region, she created one celebrating the visual and performing arts heritage of her people.

She’s seen El Museo Latino gain national status by receiving traveling Smithsonian exhibits. One brought actor-activist Edward James Olmos for the Omaha opening. The museum’s earned direct National Endowment for the Arts support.

In 2016, Garcia realized a long-held goal of creating a yearly artist residency program for local Latino artists.

Her efforts have been widely recognized. In 2015 the Mexican Government honored her lifetime achievement in the arts.

With the museum now 25 years old and counting, Garcia’s excited to take it to new heights.

“I don’t want us to just coast. I don’t want it to get old for me. For me the excitement is learning and knowing about new things – even if it’s traditions hundreds of years old we can bring in a new way to our audiences.

“We want to continue to challenge ourselves and to always be relevant by finding what else is out there, where there is a need, where do we see other things happening. Hopefully that’s still going to be the driving force. It has to be exciting for us. We have to be passionate about it. Then how do we bring that interest, love and passion to do what we said we’re going to do and to make it grow and fulfill needs in the community.”

She cultivates exchanges with Mexican art centers and artists to enrich the museum’s offerings. A key figure in these exchanges is artist-curator Humberto Chavez.

“We have connections with artists and centers in different parts of Mexico because of him,” she said. “He’s a professor of art in Mexico City and he was head of all the art centers throughout the country. He’s very well connected. That’s a huge window of opportunity for our artists here and a real plus with our residency.

“We’re not just giving artists a place and time to work and a stipend, but trying to provide them some other opportunities they wouldn’t necessarily be able to get.”

She said she hopes “to expand our network of working with other institutions as well as other artists “

Besides exposing artists and patrons to new things, Maggie’s most pleased when art connects with youth.

“I had a group of elementary students come in to see an exhibition of traditional shawls, Some of the boys and girls said, ‘What are those things doing here?’ Then as I talked about the different fabrics and colors, how the shawls are worn, what they mean, how they’re created, all of a sudden the kids were oohing and aahing at the rainbow of materials and history..

“When we came to a map of Mexico showing where the shawls were made, the kids were asking each other, ‘Where are you from?’ One said, ‘I don’t know where I’m from, but I’m going to go home and ask.’ Another pointed at the map and said, ‘Well, I’m from that state.’ Suddenly, it was accepted by their peers and so it was okay to value who they are.

“I see that all the time here. It’s very satisfying.”

Satisfying, too, is seeing the fruition of her dream reach 25 years.

“The journey has been an adventure. It hasn’t been easy. There’ve been challenges, but I thrive on challenges. If someone says, this is the way it’s been done forever, all the more reason to say, why not make a difference.”

Visit http://www.elmuseolatino.org.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

South by Southwest: Omaha South High Soccer Builds Makings of Dynasty on Diversity

South by Southwest: Omaha South High Soccer Builds Makings of Dynasty on Diversity

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in El Perico (el-perico.com)

The feel-good story of Omaha South High School’s boys soccer team nearly got lost in the aftermath of last week’s state championship game. The Packers lost 4-2 to Lincoln East at Creighton’s Morrison Stadium. Marring the action was a small group of Lincoln East fans waving American flags during the contest. In the post-game rush celebrating the win some East fans littered the field with fake U.S. resident “green cards.”

Few among the record 5,800 in attendance actually saw the incident, which happened amid a tangle of bodies. When reporters on the scene informed South Coach Joe Maass what occurred he confronted East coach Jeff Hoham.

In the ensuing flood of media coverage the offending East students were suspended. Students and officials from the schools have expressed outrage and regret. Messages have been exchanged. A face-to-face dialogue convened. All to work through the hurt feelings. Practically everyone agrees the insults were racist taunts targeting predominantly Latino South. The provocative symbols inferred illegal status in what is already a tense climate over immigration. East has a largely white student body.

What should have been a capstone moment for South, whose graduation ceremony was held blocks away before the game, instead became fodder in the growing culture war. South officials say the stunt was just the latest insensitivity the school’s endured.

“There’s been incidents throughout the season and throughout my 11 years here,” said Maass. “It’s always been there.” Principal Cara Riggs said “inappropriate comments” have been directed towards “not just our boys soccer team, but also our nearly all African-American boys basketball team. They too have suffered from similar situations.”

She noted frustration with schools “minimizing” such events but credits East staff and students for trying to make things right.

As inevitable as it may be for what transpired to be headline material in the raging immigration debate, the greater lesson is how a team from a diverse inner city school achieved great heights and didn’t take the bait when egged on.

Maass has guided the program from awful to elite. Fueling the turnaround is talent from feeder South Omaha and Bellevue soccer clubs, notably Club Viva. The mostly Latino players bring a fluid style of finesse, quickness, creativity he terms “beautiful to watch. The average kid comes here with natural foot skills and an understanding of the game. A lot of the fundamentals are there.” Plus, he said, “they want to play passionately.”

South’s lone non-Latino player, junior Alex Stillinger, came from Viva, too. He was South’s leading scorer in 2010 and he calls playing for South “an honor.” He and his teammates describe themselves as “family.” Junior Guillermo Ventura, whose brother Eric made the squad as a freshman, said, “all my teammates are my brothers.”

MATT DIXON/THE WORLD-HERALD

The coaching staff is a mix of ethnicities, including Greece native Demitrios Fountas.

Diversity is not isolated to the soccer team, said Riggs: “Our students who live in a very diverse school population…are respectful of each other’s cultures and differences.”

The Packer faithful at the state title game included Latinos and non-Latinos. “It gives us some real pride to have the power back in one of the sports,” said South High grad Tom Maass, an uncle of coach Joe Maass. Sergio Rangel, who knows several South players, said the team’s success “is a good thing for the community.”

Coach Maass believes South’s new Collin Field came to fruition when alums and backers of largely Eastern European ancestry put their faith in the Latino-led soccer program as the school’s best chance at reclaiming its long dormant athletic glory. The regulation soccer field offers a decided home advantage. South’s unbeaten there.

His first five years brought only a handful of wins. But steady progress has resulted in three state tourney appearances in four years. In 2010 the program set a school record for single-season wins, 20, and achieved several South High soccer firsts: a No. 1 ranking; a district championship; a win at state; and a championship game berth. As departing senior star Manny Lira put it after South finally beat its longtime nemesis, Creighton Prep, in the state semifinals, “It’s history within history within history.”

“Yeah, this is huge, I can’t even put it into words right now,” Maass said after South beat Lincoln Southeast for the District A-3 title. “We’ve been building to this with every little stepping stone. Every year we’ve improved a little bit. Where we’re at and where we were are two different stories. It’s been a complete reversal. People used to pat me on the back and say, ‘Oh you’re making the kids so much better.’ Now when I beat their teams I don’t get that anymore. Now it’s kind of like they can’t stand me.”

The truth is, anytime South plays a Millard, Papillion, Westside or Prep, there’s a clash of inner city-suburban, poor-wealthy, Latino-gringo. Maass said despite some bigots most opponents “respect us in the end. People actually believe we’re good now. We’ve closed the gap for sure. It’s not a fluke, it’s the real deal.”

More important, he said, is how South soccer “is building a lot of pride within our community and our kids.”

“The community has something positive to look at now at South rather than the low test scores or low graduation rates,” said Guillermo Ventura. “The community is appreciative of the school and the kids and what we have to offer.”

Before the state championship game against unbeaten and nationally ranked Lincoln East Maass said, “I’ve been telling everybody regardless of the outcome of this game the community interest and support and enthusiasm I’ve seen from all walks of life far outweighs whether we win or lose, and it’s always kind of been about that here until the tradition’s built. Then I suppose it’ll be about winning championships.”

Even after the loss, he sounded upbeat, saying, “This is the best game I’ve ever been to in terms of crowd support, South Omaha support. I’ve never been so proud to be from South Omaha in my life. Seriously. This is the pinnacle.”

Maass feels with the pipeline that’s in place it’s just the start of something big.

“I hear stories now of middle school kids wanting to come to South and play soccer, and so I’m hoping we can build on this and create kind of like an every year trip to state and possibly win a state championship.”

Graduated goalkeeper Billy Loera, who set a state record with 37 career shutouts predicts “there’s a lot more to come.”

Roger Garcia: Servant Leader

Garcia Makes Community Service his Life’s Work

©by Leo Adam Biga

Origiinally appeared in Omaha Magazne

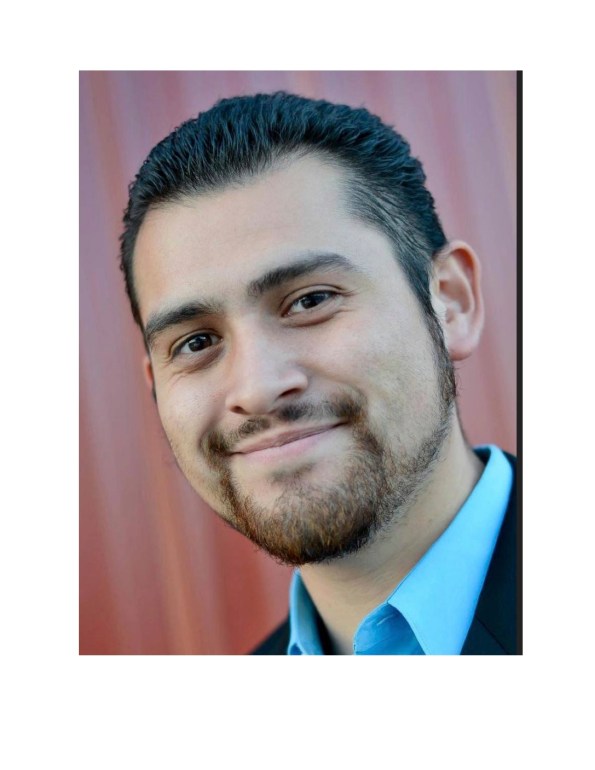

Roger Garcia fits squarely in the mix of young professionals taking their turn at leading Omaha.

As a former special assistant to Mayor Jim Suttle on urban affairs and community engagement, Garcia kept close tabs on issues impacting Latinos. Today, he continues doing the same as a community volunteer and activist with his eyes set on earning a master’s degree in public administration to prepare for the non-profit leadership role he expects to assume one day.

His community focus right now extends to serving on the boards of Justice for Our Neighbors Nebraska,the Nebraska Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and the Brown-Black Coalition of Greater Omaha. He also works with the Latino Academic Achievement Council and the South Omaha Violence Prevention-Intervention Initiative.

He chairs the Nebraska Democratic Party Latino Caucus, which actively addresses issues like redistricting and immigration.

He’s so busy he’s had to hand over the reins of the Omaha Metro Young Latinos Professional Association he founded and led.

His deep concern and involvement keep him attuned to what’s going on and to where he and the organizations he represents can help.

“I do need to know what’s going on in the community and to see where we can help out if at all possible,” he says.

Everywhere he looks, he sees young professional making a difference.

“It’s definitely a growing community that’s being sought after more and more. Lots of people are wanting to know where we stand and what our opinions are. They want us to get involved because we bring that new energy or new mind frame. Our technology-social media skills are in demand.

“I think it’s a population that will definitely gain in influence. Clearly, we’re the leaders of tomorrow.”

He’s glad the distraction of the mayoral recall election has passed and the city administration and the community can move forward as one.

“Luckily that’s over and we can focus on just bettering the community.”

For Garcia, there’s no higher calling than public service.

“I love working with people, I love trying to help people better themselves. It’s just something I truly enjoy doing. I’m blessed to have the opportunity to serve.”

Roger Garcia: A Young Man on the Move

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in El Perico (el-perico.com)

Roger Garcia is a young man in a hurry.

He took a job in Mayor Jim Suttle’s office last June at age 22, a full year short of graduating from the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Now, eight months into his position as Community Liaison this dual psychology and Latino/Latin American Studies major is slated to earn his bachelor’s degree in May.

He can hardly wait. Next up is an Omaha Board of Education bid and then either law school or pursuing his master’s in psychology, an educational-career path he said he chose “because of my love of interacting with people, which ultimately leads to a love of helping people and serving people.”

Growing up, first in Los Angeles, then in Schuyler and Columbus, Neb., Garcia was precocious, alway excelling in school and involved in community activities. His parents’ split-up in L.A. precipitated his Honduran immigrant mother Margarita coming to Neb. with Roger and his two older brothers. His mother had a cousin living in Schuyler.

The culture shock was profound.

“It was completely different going from a humongous city to a tiny Midwestern town of about 6,000 at that point,” said Garcia. “I had never seen snow, I had never seen cows. The demographics were completely different. I was just one of about three maybe four Latinos in my class. Today, if you go to Schuyler it’s like 95 percent or more Latinos in the elementary school. It’s pretty interesting how it’s changed.

“It did require adjusting but ultimately I truly liked the Nebraska lifestyle, even the small town lifestyle.”

After two years in Schuyler, where his mother worked in a meatpacking plant, the family moved to Columbus. The Garcias again found themselves part of a small minority community.

“Being a Latino newcomer, especially to those small towns, there’s a lot of good experiences and there’s a lot of bad experiences as well,” he said. “I don’t like to dwell on the bad experiences but they did happen. Of course, there’s a lot of racism in smaller towns, going as far as violent acts I saw towards my friends. Luckily no physical violence was done to me but there were things like random yelling at me and my family.

“But there’s a lot of good things that came from living in those small towns. It’s a great peaceful atmosphere. Most of my friends were Caucasian and I learned a lot from them and their families. And I am bicultural as far as having that small town Nebraska experience and learning the cultures of my parents.”

His father’s from Mexico and his step-father’s from Guatemala. His dad’s been out of his life for some time, his mother only remarried a few years ago and his brothers don’t share his passion for education. His mom pushed him to achieve.

“She’s always promoted my getting an education and she’s been there for me through my process,” he said. “She always wanted me to get those straight As and that really influenced my desire for knowledge in general, something that’s very big in my life. I love to read — history, literature. I have a passion for knowledge and learning.”

His interest in politics and government was stoked by the events of 9/11. He became a news junkie fixated on U.S. policies, issues. Upon graduating high school and enrolling at UNO his interest shifted to events closer to home. Two important figures in his life became UNO’s Lourdes Gouveia and Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado, who gave direction to his social justice bent.

“They got me involved in some political and voter mobilization campaigns. I learned a lot about policy that directly affects the Latino community. So they’ve definitely been mentors to me. I appreciate both of them.”

Garcia became an advocate and organizer with grassroots initiatives aimed at overturning anti-immigrant legislation. His role: educating the community about the impact of bills and encouraging people to participate by letting their voices be heard.

“I have a passion and a drive to just help people, stand up for them, in an educated and professional manner of course. I need to be informed on the topics.”

He worked with the American Civil Liberties Union, the Office of Latino/Latin American Studies, the Anti-Defamation League and the United States Hispanic Leadership Institute. His interest and experience coalesced when he worked on the Suttle campaign doing bilingual phone calls, canvasing South 24th St. and connecting then-candidate Suttle with local Latino leaders.

After Suttle’s victory Garcia posed ideas to the new mayor and staff about interacting with the Latino community and they liked his ideas so much, he said, “they offered me a position.” He chairs the South Omaha Advisory Committee he created himself.

“One of my main objectives coming into this is just making sure people within the community have a direct line of communication to the mayor’s office,” said Garcia. “Some people feel detached from government, that it’s hard to get straight answers, so I wanted to make sure people felt they could contact us directly and they had a source that would reliably reply to them.

Since the mayor can’t be everywhere, as a community liaison I can go to meetings for him. That’s a big part of it, being in the community, seeing what the needs are, what the happenings are.

“That’s why it’s so important to meet so many organizations and people, so they can feel comfortable that if they have any question they can just call me and they will get an answer. Sometimes I’ll join a committee or a board just to be at the ground level in the community with some projects, helping out in whatever we can utilizing city services.”

There’s no where he’d rather be.

“Doing community service is just something I love to do, so to incorporate it into my job, that’s beautiful.”

A Talent for Teaching and Connecting

A Talent for Teaching and Connecting

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico (el-perico-com)

Liberty Elementary School kindergarten instructor Luisa Maldonado Palomo has reached the top of her field as a 2010 Alice Buffet Outstanding Teacher Award-winner.

The Gering, Neb. native is the grade leader at her Omaha school. She heads outreach efforts to parents, many of them undocumented, through the Liberty Community Council. She’s a liaison with partners assisting Liberty kids and families. The school engages community through parenting and computer classes, food and clothes pantries, and, starting in the fall, a health clinic.

Colleagues admire her dedication working with the school’s many constituents.

“She truly reaches the whole child — behaviorally, academically, socially, emotionally — and then steps beyond that and reaches the family too,” said Liberty Principal Carri Hutcherson. “We can count on her to do a lot of the family components we have at Liberty because she gets it, she has a heart for it, the passion, the drive, the focus, all those great things it takes. She’s an expert practitioner on so many levels.”

But there was a time when Palomo questioned whether she wanted to be a classroom teacher. While a Creighton University education major she participated in Encuentro Dominicano, a semester-long study abroad in the impoverished Dominican Republic. She described this immersion as a “huge, life-changing experience” for reawakening a call to service inherited from her father, Matt Palomo.

“My dad has spent his whole life doling for others,” she said. “He comes from a migrant worker family. He gave up a college scholarship to work so he could help support his nine brothers and sisters. From the age of 15 he’s been involved with the Boy Scouts as a scout leader. He just celebrated his 45th year with the Boy Scouts of America.

“He’s always worked with underprivileged youth, Hispanic or Caucasian, in our small town. He’s such a role model for so many young boys who’ve gone through that program. He has such a sense of what’s right and wrong and he’s instilled that in my brother and sister and I.”

Luisa Palomo (standing) talks to Primarily Math Cohort 3 LPS on June 6.

Luisa Palomo (standing) talks to Primarily Math Cohort 3 LPS on June 6.

In the Dominican Republic Luisa felt connected to people, their lives and their needs.

“You work, take classes and live with families,” she said. “You learn the philosophy and the why of what’s going on. You really learn to form relationships with people, which isn’t something that always comes naturally to Americans. Here, it’s always more individualistic and what do I need to do for myself, whereas in a lot of other countries people think about what do I need to do for my community and my family.”

The communal culture was akin to what she knew back in Gering. When she returned to the States she sought to replicate the bonds she’d forged. “I came back wanting that,” she said. Unable to find it in her first teaching practicums, she became disillusioned.

“I was ready to quit education and my advisor was like, ‘Nope, there’s this new school in a warehouse and Nancy Oberst is the principal and you’ll meet her and love her — give it a shot before you quit.’ So I went there and loved it and stayed there. Nancy and I just clicked and she hired me to teach kindergarten.”

Liberty opened in 2002 in a former bus warehouse at 20th and Leavenworth. In 2004 it moved into a newly constructed building at 2021 St. Mary’s Avenue. Oberst was someone Palomo aspired to be like.

“She’s so dynamic and such a good model,” said Palomo. “She has such a vision for how a school should be — it shouldn’t be an 8:30 to 4 o’clock building. Instead it should be a community space where it’s open all the time and families come for all kinds of different services, and that really is the center of the community.”

Oberst and many of Liberty’s original teachers have moved on. Palomo’s stayed. “We have a core group of parents who have been with us from the old building and they know I’m one of the few teachers who have been here all eight years,” she said. “They’ve seen what I do. They know Miss Palomo is the one who spent the night in the ER when Jose broke his arm and started a fund raiser when Emiliano’s house burned down. They know me and they trust me and they let me into their homes.

“They know I’m coming from a good place.”

She said one Liberty family’s “adopted” her and her fiance. The family’s four children will be in the couple’s fall wedding.

Hutcherson said Liberty is “the hub” for its downtown neighborhood and educators like Palomo empower parents “to feel they’re not just visitors but participants.” Whether helping a family get their home’s utilities turned back on or translating for them, she said Palomo and other staff “step out of the walls of this building to get it done.” For two-plus years Palomo mentored a girl separated from her parents.

“It’s that whole reaching out and meeting our families where they’re at,” said Palomo.

Liberty’s holistic, family-centered, “do what’s best for the child” approach is just what she was looking for and now she can’t imagine being anywhere else.

“I really love it here. We’re not just a teacher in the classroom. We do so much to really bring our community into our school so our families can come to us for all these different activities and for help with different needs. It’s one of those things where we let them into our lives and they let us into theirs, and we’re both better for it.”

She’s proud to be “a strong Hispanic” for kids who may not know another college graduate that looks like them.

Palomo recently earned her master’s in educational administration from UNO. Sooner or later, she’ll be a principal. Hutcherson said when that day comes “it’ll be a great loss to Liberty but a great gain for the district.”

Positively, no negativity: Nick Hernandez

Positively, no negativity: Nick Hernandez

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the July 5, 2018 issue of El Perico (el-perico.com)

Some call it bliss. Others, serenity. For Nick Hernandez of Lincoln, Nebraska, the study and practice of positive psychology is both way of life and career.

The 41-year-old couldn’t have imagined this two decades ago. Back then, the Olathe, Kansas native was a married post-graduate student who looked at people and life critically. Now he’s co-founder and evangelist for an organization called Posiivity Matters, He hosts Community Matters on KZUM 89.3 FM, conducts coaching-team building workshops, makes presentations and organizes activities – all around the notion that individuals and communities thrive when engaged in nurturing activities.

He’s convened regional and citywide summits (Happiness Lincoln) and contributed to events (Cameron Effect and Seeds of Kindness) on the subject.

Before finding his niche, he got divorced and entered recovery for a problem drinking habit. The seeds of his “community-building” were planted earlier through Hispanic leadership opportunity and Midwest Center for Nonprofit Leadership programs he completed in Kansas City, Missouri.

He earned a bachelor’s degree from liberal arts Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas and did graduate studies in economics at the University of Texas at Austin.

When he lost his job as an economist with the Texas Department of Labor, he found a matching job with the Nebraska Department of Labor in 2002. When his unit took the Gallup organization’s Strengths Finder test, he learned a new way of thinking and being. “It was a very meaningful experience,” he said. “I then discovered there is a field called positive psychology.” In reading up on it, he became convinced he found the holistic pathway he’d been missing.

“It was a shift in mindset. I had a real critical mindset that wasn’t focused on strengths before. It opened up new territory for how how I saw myself and others.”

Newly aware he was by nature and nurture a convener, a leader, an affirmer and an appreciator, he embraced “hooking up with good in ourselves” and became “an encourager for others to grow into potential you see in them that they may not be aware of.”

“I found it really fulfilling to be in that role for others.”

Meanwhile, he sounded out experts who further encouraged his interest in the philosophy and science of positive psychology, well-being and human flourishing.

“That deepened my sense that maybe I’m onto something here.”

He then broadened his reach of influence.

“I started getting involved more in the community.”Nick

Nick Hernandez

Upon completing the Great Neighborhoods program offered by Neighbor Works Lincoln, he said, “I found myself feeling a sense of purpose to see if it could be put into action at the neighborhood association level.”

In 2007 he restarted the dormant Havelock Neighborhood Association and revived its fall festival.

“It was quite an enriching experience to create an occasion for people from different places in the neighborhood to get together. I enjoy coming up with activities that make mindfulness fun and accessible.”

He helped lead kindness campaigns in Lincoln that inspired participation by adults and youth.

“Kindness hopefully has a double effect. The stories we tell ourselves when we volunteer or do random acts of kindness are self-affirming. We think, ‘I’m the kind of person that practices generosity, kindness and compassion.’ That alters the story of who we are in our identity.’

Hernandez’s journey has been far more than academic.

“It was spurred by my own experiences in recovery and then getting involved in service work. What I found eventually was a profound sense of fulfillment by volunteering to take a recovery meeting into the Lancaster County adult detention center.

“That’s where I really felt I started taking this idea of practicing generosity as a way of life and really committed myself to doing it in a systematic way.”

His recovery has paralleled his well-being quest.

“Once I got into recovery I realized I felt a deep sense of loneliness. I know there were people around me who loved and cared for me, but for some reason I wasn’t letting it connect. Through being in recovery and getting in service, I finally felt that sense of connectedness.”

Since humans are genetically wired to be on high alert, he said, we must consciously choose positive thoughts. He’s convinced our basic desire and need for well-being is achieved “when we’re able to share our sense of self, our core ideas with others in a positive relationship, whether friendship or romantic, who really care about us growing into that.”

“That’s the direction I’m trying to take this habit of kindness and generosity. I am exploring if this can be something fostered through small group conversation grounded in the philosophy and science of well-being.”

He’s long organized discussion groups promoting positive psychology research and the benefits of practicing mindfulness. His 2015 Happiness Lincoln summit at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln featured scholars on the 15th anniversary of America’s first national positive psychology conference held in Lincoln, a community that ranks high in well-being measures.

His Community Matters radio show facilitates discussions with well-being experts from around world, including a recent guest he Skyped-in from Israel.

On May 20 he organized a community conversation on collaboration at Lincoln’s Constellation Studios with fiber artist Karen Kunc, a philosophy professor and a public health advocate.

His speaking, coaching, team building doesn’t pay all the bills, thus he makes money other ways, including teaching social dance – swing, salsa, tango, ballroom.

“That’s personally an extremely fun, positive psychology intervention – cognitive, social, physical well-being all in one.”

He’s now actively pursuing work in the human resources field.

Follow him on Facebook and YouTube. His show broadcasts Mondays from 11:30 a.m. to Noon and streams at http://kzum.org.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

Paul Serrato finds balance as musician and educator

Paul Serrato finds balance as musician and educator

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico (el-perico.com)

Finding home: David Catalan finds community service niche in adopted hometown of Omaha

Finding home: David Catalan finds community service niche in adopted hometown of Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon appearing in El Perico

David Catalan long searched for a place to call home before finding it in Omaha four decades ago.

Born in San Diego, Calif. and raised in Arizona, the former business executive turned consultant has served on many nonprofit boards. It’s hard to imagine this sophisticate who is so adroit in corporate and art circles once labored in the migrant fields with his Mexican immigrant parents. It’s surprising, too, someone so involved in community affairs once lived a rootless life.

“My whole life had been like a gypsy. I was a vagabond because traveling from place to place and never really having a fixed home – until I came to Omaha with Union Pacific in 1980.. I chose to stay even after I left U.P. because I really felt at home here and still do after all those years wandering around.”

Vagabundo, a book of his own free-style verse, describes his coming-of-age.

Catalan, 76, grew up in a Tucson barrio immediately after World War II. His father worked in the copper mines. When Catalan was about 13, his family began making the migrant worker circuit, leaving each spring-summer for Calif, to pick tomatoes, figs, peaches and grapes and then returning home for the fall-winter.

“I didn’t really feel I wanted to get stuck in that kind of a destiny,” he said. “Maybe escape is too rough a word, but I had to get away from that environment if I was going to do anything differently, and so I left and went to live with a sister in the Merced (Calif.) area.”

He finished high school there and received a scholarship to UCLA,

“I was the only one in the family that actually completed high school, let alone college.”

He’d long before fallen in love with books.

“That led me to realize there was more I could accomplish.”

While at UCLA, a U.S. Army recruiter sensed his wanderlust and got him to enlist. He served in Germany and France. He stayed-on two years in Paris, where an American couple introduced him to the arts.

“It was a big awakening for me,” he said.

Back in the U.S., he settled in Salt Lake City, where he was briefly married. Then he joined U.P., which paid for his MBA studies at Pepperdine University. Then U.P. transferred him from Los Angeles to Omaha.

“I never had a sense of knowing my neighbors, having some continuity in terms of schools and experiences, so I felt like I had missed out by not having had that identity with place and community. When I came to Omaha, I loved it, and U.P. really promoted employees getting involved in community service.

“Doing community service, being on nonprofit boards became an identity for myself.”

Upon taking early retirement, he worked at Metropolitan Community College, in the cabinet of Mayor Hal Daub and as executive director of the Omaha Press Club and the Nonprofit Association of the Midlands.

“I threw myself into the nonprofit world.”

He’s served on the Opera Omaha, Omaha Symphony and Nebraska Arts Council boards.

He cofounded SNAP! Productions, a small but mighty theater company originally formed to support the Nebraska AIDS Project.

“Omaha was the first place I saw a couple friends die of AIDS and that was a real revelation for me. That got me working to do some fundraising.”

SNAP! emerged from that work.

“I was the producer for almost every production the first few seasons. The audience base for SNAP! is a very accepting part of the community. It was gratifying. It’s been very successful.”

His interests led him to South Omaha, where he helped found El Museo Latino. More recently, he helped get the South Omaha Museum started. He also served as president of the South Omaha Business Association.

“I got involved with a lot of economic development.”

He wrote and published Rule of Thumb: A Guide to Small Business Marketing.

He’s “very proud” both SNAP! and El Museo Latino, whose vision of Magdalena Garcia he caught, “are still going strong and still serving the community.”

Each time he gets involved, he said, “it isn’t planned – the need arises and I’m there willing to help work to make it happen.”

“Doing all this work helps me feel I am a part of a dynamic community. That’s what really drives me, motivates me and makes me feel very positive.”

He’s involved in a new project that dreams of building a 300-foot tall Nebraska landmark destination to be called “Tower of Courage” at the intersection of 13th and I-80 across from the Henry Doorly Zoo.

“We’re in the process of trying to acquire the land. It’ll be a place for culture-history exhibits all focused on the rich cultural and historical history of Neb. and the region.”

Meanwhile Catalan has his own consulting company helping nonprofit and small business clients with strategic planning and grant-writing.

He’s also active in the Optimist Club.

“I’ve lived a full life. I’ve met so many wonderful people. I can navigate around many communities because of the the work I’ve done and the people I’ve met.”

He’s doing research for what may be his third book: weaving the story of a pioneering Jesuit priest from the same Sonora. Mexico hometown Catalan’s mother was born in and near where his father was from, with the history of area Indian tribes and his own family.

He’s traveling this winter to Sonora – not to escape his roots but to discover more about them.

He’s written about his family in Vagabundo and in poems published in the literary journal, Fine Lines.

“I think I’m creating a David Catalan space of my own I never had growing up.”

Rony Ortega follows path serving more students in OPS

To be a public schools advocate, one doesn’t have to be a public education institution graduate. Nor does one need to be a professional public schools educator or administrator, But in Rony Ortega’s case, he checks yes to all three and he feels that background, plus a strong work ethic and desire to serve students, gives him the right experience for his new post as a district executive director in the Omaha Public Schools. He supervises and guides principals at 16 schools and he loves the opportunity of impacting more students than he ever could as a classroom teacher, counselor, assistant principal and principal. He also feels his own story of educational attainment (two master’s degreees and a doctorate) and career acheivement (a senior administrative position by his late 30s) despite a rough start in school and coming from a working-class family whose parents had little formal education is a testament to how far public education can carry someone if they work hard enough and want it bad enough. Read my profile of Rony Ortega in El Perico.

Rony Ortega follows path serving more students in OPS

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

Rony Ortega has gone far in his 15-year career as an educator. He worked in suburban school districts in Elkhorn and Papillion before recruited to the Omaha Pubic Schools by former OPS staffer and veteran South Omaha community activist, Jim Ramirez.

Ortega. who’s married with three daughters, all of whom attend OPS, has moved from classroom teacher and high school counselor to assistant principal at South High to principal of Buffett Middle School. Earlier this year, he was hired as a district executive director tasked with supporting and supervising principals of 16 schools.

The Southern California native traces his educational and professional achievement to his family’s move to Nebraska. Negative experiences in Los Angles public schools in the 1980s-1990s – gang threats, no running water, rampant dropouts – fueled his desire to be a positive change agent in education. In Schuyler, where his immigrant parents worked the packing plants, he was introduced to new possibilities.

“I’m thankful my parents had the courage to move us out of a bad environment. Really, it wasn’t until I got here I met some key people that really changed the trajectory of my life. I met the middle class family I never knew growing up. They really took me under their wing. We had conversations at their dinner table about college-careers – all those conversations that happen in middle class homes that never happened in my home until I met that family.

“That was really transformational for me because it wasn’t until then I realized my future could be different and I didn’t have to work at a meatpacking plant and live in poverty. I really credit that with putting me on a different path.”

He began his higher education pursuits at Central Community College (CCC) in Columbus.

“I went there because, honestly, it was my only option. I was not the smartest or sharpest kid coming out of high school. Just last year, I was given the outstanding alumnus award and was their commencement speaker. I was humbled. Public speaking is not something I really enjoy, but I did it because if I could influence somebody in that crowd to continue their education, it was worth it. And I owed it to the college. That was the beginning of my new life essentially.”

He noted that, just as at his old school in Schuyler, CCC-Columbus is now a Hispanic-serving institution where before Latinos were a rarity. His message to students: education improves your social mobility.

“No one can take away your education regardless of who you are, where you go, what you do.”

He completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and went on to earn two master’s and a doctorate at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

“I’m really the first in my family to have more of an educational professional background,” Ortega said, “I don’t think my parents quite yet grasp what I do for a living or what all my education means, so there’s some of that struggle where you’re kind of living in two worlds.”

He expects to keep advancing as an administrator.

“I have a lot of drive in me, I have a lot of desire to keep learning. I do know I want to keep impacting more and more kids and to have even a broader reach, and that is something that will drive my goals going forward.

“It’s very gratifying to see your influence and the impact you make on other people. There’s no better feeling than that.”

He’s still figuring out what it means to be an executive director over 16 principals and schools.

“For now, I’m focusing on building relationships with my principals, getting to know their schools, their challenges, observing what’s happening. So right now I’m just doing a lot of leading through learning. It’s quite the challenge with not only the schools being elementary, middle and high schools but being all over town. Every school has challenges and opportunities – they just look different. I’m trying to learn them.

“When I was a principal, I had teachers who needed me more than others. I’m learning the same thing is true with principals – some need you more because they’re new to the position or perhaps are in schools that have a few more challenges.”

Having done the job himself, he knows principals have a complex, often lonely responsibility. That’s where he comes in as support-coach-guide.

“We’re expecting principals to be instructional leaders but principals have a litany of other things to also do. Our theory of action is if we develop our principals’ capacity, they will in turn develop teachers’ capacity and then student outcomes will improve.”

He knows the difference a helping hand can make.

“No matter where I’ve been, there’s always been at least one person instrumental in influencing me. The research shows all it takes is one person to be in somebody’s corner to help them, and there’ve been people who’ve seen value in me and really invested in me.”

His educational career, he said, “is my way of giving back and paying it forward.”

“It’s so gratifying to wake up every day knowing you’re doing it for those reasons. That’s really powerful stuff.”

He purposely left the burbs for more diverse OPS.

“I kept thinking I’ve got to meet my heart. I wanted to do more to impact kids probably more like me.”

He’s proud that a district serving a large immigrant and refugee population is seeing student achievement gains and graduation increases, with more grads continuing education beyond high school.

As he reminds students, if he could do it, they can, too.