Archive

Manifest Beauty: Christian Bro. William Woeger devotes his life to Church as artist and creative-cultural-liturgical expert

Omaha’s cultural scene is stronger thanks to Christian Brother William Woeger. He heads the Archdiocese of Omaha‘s Office for Divine Worship but is best known as founder and director of the Cathedral Arts Project based at St. Cecilia Cathedral. The project sponsors many performing and fine arts presentations throughout the year, including a flower festival that draws tens of thousands over a single weekend. He oversaw a major restoration project at the magnificent cathedral a few years ago. Adjacent to the cathedral is an impressive visitors-cultural center that was developed under his leadership. The following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) apepared while the restoration was still underway. Something I discovered about Woeger in doing the story is that in addition to being a highly respected liturgy expert and arts administrator, he is also a nationally renowned icon artist.

Triptych designed and painted by Bro. William Woeger

Manifest Beauty: Christian Bro. William Woeger devotes life to Church as artist and creative-cultural-liturgical expert

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

If not traveling to confer on a church renovation or to install one of his commissioned art works, national liturgical design consultant and icon painter Brother William Woeger can be found working the phone from his tidy office in the Archdiocese of Omaha chancery. From there, the fastidious Woeger juggles a busy schedule as head of the Office for Divine Worship and as executive director and founder of the popular Cathedral Arts Project. For good measure, the 54-year-old visionary — one of the early driving forces behind Omaha’s compassionate response to the AIDS epidemic — is director of liturgy at St. Cecilia Cathedral, whose $3 million restoration he is shepherding toward completion.

Gaze Upon My Soul

When the demands of his career and vocation get to be too much for the admittedly “driven” Woeger, a 36-year veteran of the Christian Brothers teaching order founded in 1864 by French cleric John Baptist de la Salle, he retreats to the solace of his painting. In keeping with tradition, Woeger’s iconic figures (mostly of Christ) are bathed in an aura of gold light suggestive of the Holy Spirit. His acrylic paint-on-wood works adorn churches in Omaha and around the nation. He recently completed and shipped the last in a set of 15 icons for a new church he helped design in Maryland. Word-of-mouth alone keeps him immersed in new projects. “I don’t advertise. I don’t submit drawings and designs. I don’t do committees,’ he said. Working from a basement studio, he enters a nearly transcendental meditative state amid the solitude and the golden reflected gaze of the icon he is rendering.

“When I am in the act of painting it actually creates a space in my life when I’m not tied into anything else. Aside from the sound of the furnace kicking-on, it’s a very contemplative experience,” he said. “And it’s very interactive in the sense that you begin manipulating the materials and then, at a certain moment — and sometimes it’s quite identifiable — the dynamics flip around and suddenly It’s doing it’s thing to you rather than you doing something to it, and it kind of finishes itself. That most often has to do with the face and the eyes — when the image starts looking back at you — which is at the heart of icons as a focus for prayer.

“The whole notion is very non-Western. The icon becomes a window, if you will, through which you contemplate the divine. Even if the image is not one of Christ but rather one of the saints, the whole metaphor with the gold hue in the background is that the source of the light is not the person — it’s beyond the person — and that is God being mediated through the figure in the painting, which is very incarnation-oriented.”

Bro. William Woeger

Upon This Rock

Born and raised in a south St. Louis German-Catholic family, Woeger felt an affinity for the arts and a calling to religious life as a youth and has combined these passions ever since. He entered the Christian Brothers at 18 and pronounced his perpetual vows at 25. While studying art, theology and philosophy in the ‘60s he developed a social conscience. He began a formal teaching career in 1967 when assigned to Omaha’s Rummel High (now Roncalli), whose art department he established. He later taught at the College of St. Mary. In 1981 he joined the archdiocesan staff, where his focus evolves “depending on what I see around me.”

Through his archdiocesan post he coordinates area liturgical celebrations. As a freelance liturgical designer he integrates music, art, ritual and architecture in churches nationwide. Striving to make each place of worship a “sermon without words,” he goes about “shaping the building around the liturgical action,” adding, “I see what I do as educational. I help clients take liturgical principles and use those as a stepping off point to create a house for the church and the community in which to worship and praise God.” Since each parish has its own distinct personality, he must balance unique cultural characteristics (ethnic, socioeconomic, charismatic, conservative, etc.) with Roman Catholic doctrine and tradition. “There can be a tension there, but it can be a creative thing,” he said.

His services range from all-encompassing design schemes to specific features. “Sometimes I’m involved from the very beginning all the way to the end, including designing the furniture, working with the architect, being a go-between with artists doing windows or sculptures and holding workshops with local liturgical ministers. It’s a helluva package. Other times, I just come in and help with the programming. End of story. Or, other times, I just design furniture or do an icon. It’s much easier to do a brand new building than it is a restoration because it’s no-holds-barred, at least conceptually. Sometimes I work on buildings that have a historic reference where we borrow the architecture vocabulary from another period. St. Vincent DePaul Church in Omaha is like that. It’s a contemporary building but definitely has a Gothic reference.”

Whatever the assignment, he tries making each church a metaphorical emblem of the Catholic faith and its people. “The definition of a symbol is something that points to a reality beyond itself, and church architecture has tremendous potential to do that,” he said. He feels much of modern church design “fails” in this regard by opting for flimsy rather than solid values. “I’m not knocking modern architecture in comparison with classical it-looks-like-a-church architecture. I’m talking about the whole American phenomenon of suburban architecture — the here-today-gone tomorrow strip-mall transitory approach to things as opposed to an approach that establishes a sense of place and an air of permanence. Especially if you buy into the idea church buildings are places where key moments in peoples’ lives are celebrated or sanctified, than the building-as-place becomes a touchstone for their memory and, so, the walls speak.”

Imbuing a church with indelible substance requires rigorous attention to detail. It starts with a philosophy. He said, “It’s about believing in things getting better as they get older. It’s about using quality materials, which isn’t necessarily the most expensive, but ones which the community feels invested in as ‘The best we have to put forward.’ It’s about the materials and design being appropriate. It’s about integrity and all these things bearing the mark of the maker and not appearing to be mass-produced but rather created for sacred purposes. And, in the final analysis, the building should be capable of bearing the weight of mystery. The weight of mystery is what gets you in touch with the presence of God and gives you the sense this is holy space. Using strip mall approaches doesn’t cut it. It can’t carry the profundity. This is God-stuff we’re talking about. It’s pretty heavy, and so there’s no room for the trite, the silly, the mundane, the pedestrian, the pop.”

Makeovers and New Directions

This same philosophy has underpinned the restoration of Omaha landmark St. Cecilia Cathedral, the Thomas Rogers Kimball-designed Spanish renaissance revival building begun in 1905 and completed in 1958. Except that, after Kimball’s death in 1934, the building was never quite finished and the famed Omaha architect’s plans never fully carried-out. Much of the Spanish flavor Kimball intended was ignored or altered. According to Woeger, Kimball’s design drew on the buoyant monastery palace complex of Spanish ruler Philip II. To recapture that model, Woeger selected Evergreene Painting Studios Inc. of New York, to execute the restoration, and Omaha architectural firm Bahr Vermeer Haecker to oversee the project.

Recent interior work done to the Cathedral, including extensive surface cleaning, the use of bold Iberian stencil patterns in the ceiling and nave, the addition of several large murals and various lighting enhancements, has appreciably brightened the building to provide a warmer, more vibrant, more visceral space in which one’s eyes invariably look up to the heavens. The idea was to create a vital ambience for public worship and celebration in which “the whole assembly is praying with one mind, one heart, one voice.” Woeger adds, “We had an opportunity to bring a much more exuberant Spanish renaissance style feeling to the interior finishes. Now, you have the sense the building is bigger and higher. It definitely evokes wonder and awe, and that architecture’s supposed to do that. Now, you can just watch people look up when they walk in. They didn’t use to do that because you really couldn’t quite take it all in it was so dark.”

Making the Cathedral an inspirational community gathering place is something Woeger had in mind when starting Cathedral Arts Project, an autonomous presenting organization sponsoring concerts, art exhibits and an annual flower show. His other impulse was putting St. Cecilia’s squarely in-line with the historic mission of cathedrals as a center of the humanities. “All of the spiritual reality that building stands for is an appropriate context for that which is spiritual about the arts,” he said. “It broadens the scope of the people who enter the life of the Cathedral. And, historically, cathedrals were the center of learning, the center of the arts, the center of humanity, the center of theology and spirituality.”

For Woeger, an “off-the-charts control person” who lost his father at age 9, the AIDS crisis presented a special challenge. “I spent a lot of time with people while they were dying and early on it was sort of making me crazy. I had to learn I couldn’t do anything about this. That the best thing I could do was simply be there for them.”

With the death-sentence urgency of the AIDS crisis largely passed and the Cathedral restoration drawing to a close, Woeger is looking for new challenges. “I’m the kind of person who reinvents himself about every six to eight years. I have to have some new stimuli in order to keep my creative juices flowing. It doesn’t have to be a radical change, but some kind of shift so that things sort of come apart and come back together again in a new configuration.”

Not surprisingly, his renewed focus is on upcoming projects at the Cathedral. First, life-sized statues (of saints) carved in Italy will be installed on exterior niches perched above the main entrance and a side entrance. The niches have sat empty the entire life of the Cathedral. Next, an ambitious organ restoration is on tap. And, once funds are secured, work will begin on a visitors/cultural center that will tell the story of the Cathedral and the legacy of Kimball in a museum to be housed in the former Cathedral High School building. Through such efforts he hopes the Cathedral remains a beacon for generations to come.

Related articles

- Omaha Address by Cuban Archbishop Jaime Ortega Sounds Hopeful Message that Repression in Cuba is Lifting (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Change is Gonna Come, the GBT Academy in Omaha Undergoes Revival in the Wake of Fire (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Nancy Kirk: Arts Maven, Author, Communicator, Entrepreneur, Interfaith Champion (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Omaha address by Cuban Archbishop Jaime Ortega sounds hopeful message that repression in Cuba is lifting

The vast majority of my journalism is accomplished far away from other media, but once in a while I end up as part of the pack when reporting a story, as was the case when I covered a May address by Cardinal Jaime Ortega of Havana, Cuba during a visit he made to Creighton University in Omaha. Actually, there was just one other journalist there to my knowledge, but he was representing the local daily and so I needed to be on my game with tape recorder rolling and notepad and pen at the ready capturing Ortega’s remarks. As the leader of the Catholic Church in that island nation, he has navigated an uneasy relationship with the Communist regime. In recent years he’s presided over a revival of the church there and entered a dialogue with the hard line government, which has considerably softened in what can only be called a reform movement that’s transforming Cuba into a freer nation. Critics of Ortega contend he hasn’t pressed Cuban officials enough, but the evidence suggests a major change is underway and basic human rights are being respected in ways not see before under the revolutionary banner. My story appeared in El Perico, a weekly Spanish-English newspaper published in South Omaha.

Omaha address by Cuban Archbishop Jaime Ortega sounds hopeful message that repression in Cuba is lifting

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in El Perico

During a May 12 commencement address at Creighton University, Havana, Cuba archbishop Rev. Jaime Ortega described the uneasy journey the Catholic Church has navigated in the Communist island nation.

At a separate weekend event, Cardinal Ortega received an honorary law degree in recognition of his humanitarian work.

In introductory remarks last Thursday Creighton president Rev. John Schlegel, who’s visited Ortega in Cuba, praised the cardinal for “working relentlessly to mediate between the government of Raul Castro and the families of prisoners of conscience…Above all, Cardinal Ortega has proven to be a great pastor, a great leader, especially through challenging times, and a great priest.” Schlegel described Ortega as a “diplomat” seeking “the greater good, truth and justice.”

The estimated 125 attendees included Creighton faculty, Archdiocese of Omaha officials and members of Nebraska’s Cuban and greater Latino communities.

Speaking through a translator, Ortega charted the repression that followed the 1959 revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power. Ortega sounded hopeful about the new, freer Cuba emerging. He referred to frank, cooperative exchanges between the church and government authorities that recently brought the release of 52 political prisoners.

This avowed son of Cuba proudly declared, “I am a Cuban who lives in Cuba. I never wanted to live outside Cuba. It is a country I love with all my heart.”

He drew parallels between early Christian religious leaders serving their flocks amid oppression and clergy and pro-Democracy dissidents finding their voices suppressed under Fidel. He said rather than take a militant tack, the Cuban church followed a pastoral, passive approach.

“The Cuban bishops have tried to be shepherds in this way in Cuba,” he said. “Its role is not to confront the established powers.”

However, he says “the church is always asking for religious liberty, so that its followers can live their lives in peace.”

He outlined where the church and Cuba are today in comparison with the post-revolutionary period. “Initially,” he said, “there was a great acceptance of the revolution because of finding so many points of value with it.”

Within two years though, he said “very strong confrontation” and persecution distanced the church from the regime and the revolutionary fervor. He said priests were expelled from the country, Catholic schools closed, ministries and other expressions of religion curtailed and various “attacks” made on the church. He was among many young men in the church sent to labor camps.

The harsh measures, he said, “had a negative impact on the Catholic faithful” and “marked the memory” of older Cubans. He said, “This is a mark that is hard to erase.” While the bishops decried human rights violations, he said “the church as an organization was very diminished and had no means of communicating with its people.” He characterized the Cuban church then as “a church of silence,” adding, “The attitude of the church then was one of patience, perseverance, prudence.”

He said despite restrictions imposed on social, political, religious practices, fear of arrest and economic hardship, many Cuban Catholics remained faithful and risked much to speak out.

A turning point was a reflective, renewal process the Cuban Bishops Conference initiated in 1981, extending to every diocese, culminating with the 1986 National Ecclesial Encounter Cuba. “This constituted a very decisive moment for the history of the church in Cuba,” he said. It laid the groundwork for Pope John Paul II’s 1998 visit to Cuba. As a result, he said, “the church in Cuba let itself be known to the world and Cubans themselves realized there was in Cuba a church that was alive and dynamic.”

Since the conference and papal visit, he asserts the church has taken more of an active, public, missionary role and today is a church “that lives for its people,” rather than “wrapped up in itself,”” welcoming whoever comes to it.

Framing this empowerment, he said, is a new spirit of dialogue between the church and government, which he describes as “more fluid” under Raul Castro. In a Q & A after his address, Ortega said, “It has been much easier to find somebody with whom to dialogue. There seems to be a greater openness to changes.”

He’s encouraged by greater religious freedom, whose public manifestations include massive crowds for outdoor rites and a recently dedicated seminary.

On the activist front, he said an intentional process of “pastoral action” with authorities negotiated improved conditions for political prisoners, who were allowed to have contact with their families before finally gaining release. “Our humanitarian gesture was accepted,” Ortega said. He also alluded to recently announced Cuban social-political reforms.

With Cuba now thriving, he said its experience demonstrates “the human spirit should not be endangered or limited” and that liberation needs to come in both the spiritual and social life of people, adding, “It should never be necessary to negate God in order to enjoy human rights or to be active citizens.”

Ortega acknowledges that for victims of Cuban injustice “the baggage” and “suffering” remain. For “true reconciliation among all Cubans,” he said, there must be forgiveness and understanding — only then will the wounds inflicted under the old regime heal. Cuba, he insists, is moving on in acceptance and he suggests the rest of the world move on, too.

University of Nebraska at Omaha political science professor Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado, who’s extensively studied Cuba, admires Ortega for “toeing the line for the purposes of advancing the church and its teachings and its ministry.”

Referring to criticism by some that Ortega’s been slow to press for more reforms, Benjamin-Alvarado says, “His approach perhaps wasn’t as quick as some would have liked, but the fact is it’s been successful. I think what he’s understood perhaps better than most was the limitations on what the church actually could do. He moved when he could and didn’t try to deal with issues he wasn’t able to have any answer or response to.”

Related articles

- Cuba Bids Farewell to Nuncio (onecatholicorg.wordpress.com)

- Cuban bishops: Country is slowly moving toward a democratic system (onecatholicorg.wordpress.com)

- Spain receive 37 more Cuban ex-political prisoners (foxnews.com)

Omaha St. Peter Catholic Church revival based on restoring the sacred

If a potential client of mine had not referred me to a revival going on at a once proud Catholic church in Omaha that had fallen on hard times but is now undergoing a revitalization, I wouldn’t have known about it. This despite the fact I often drove past this church. The story I wrote about the transformation going on at St. Peter Catholic Church in Omaha originally appeared in El Perico. I applaud what the pastor there, Rev. Damien Cook, and his staff and parishioners are doing to infuse new life into the church by going back to the future in a sense and restoring the sacred to celebrations that had been stripped of solemnity and pageantry in the post-Vatican II world. On this same blog you can find my story titled, “Devotees Hold Fast to the Latin Rite,” and other Catholic-themed stories, particularly two dealing with the recently closed St, Peter Claver Cristo Rey High School and several dealing with Sacred Heart Catholic Church, including one focusing on the church’s inclusive spirt and another on its Heart Ministry Center.

Omaha St. Peter Catholic Church revival based on restoring the sacred

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in El Perico

Just east above a stretch of I-480 stands St. Peter Catholic Church at 27th and Leavenworth. Its classical Greco-Roman facade is unlike anything in that sketchy near downtown Omaha district. Amid ramshackle urban surroundings the stone edifice is a solid, substantial front door for a poor, working class area made up of transients, bars, liquor stores and social service agencies as well as light industrial businesses, eateries, artist studios, apartments and homes.

When St. Peter’s pastor Rev. Damien Cook arrived in 2004 the church teetered on its last legs.

“It was a dying parish,” he says flatly.

He says before the Interstate came in the parish thrived but when homes were razed for the road-overpass construction, parishioners scattered to the far winds, leaving a psychological scar and physical barrier that isolated the parish.

From the pulpit Fr. Cook saw few pews filled in a sanctuary seating 800. The membership rolls counted only a small if dedicated cadre. With the school long closed and most old-line parishioners long gone, things looked bleak.

Seven years later, however, St Peter is enjoying a revival– “the numbers have vastly gone up” — that has its roots in demographics and faith. As the parish celebrates its 125th anniversary this spring and makes plans for an extensive interior church restoration there’s a resurgence afoot that belies the forlorn neighborhood.

“It’s a big year for us,” Cook says.

Always a mixed ethnic district, the Hispanic population was growing when Cook came, but has spiked since then. Many more began attending after St. Anne‘s closed. Now the church is predominantly Hispanic, though there’s a sizable non-Hispanic base as well.

Several Spanish Masses are offered each week. Quinceanera ceremonies occur there. A Spanish school of evangelization holds retreats in the old school building.

Where the congregation was decidedly aged before, it now over-brims with families, many with young children. Catechism classes serve more than 300 youths.

Perhaps most impressive, Cook says, is that the majority coming to St. Peter today don’t live within the parish boundaries but drive-in from all across the metro, making it a true “commuter parish.”

Fr. Damien Cook

Why are folks flocking there?

It seems Cook has struck a chord in the effort to, he says, “restore the sacred at the church.” It trends with a national movement aimed at returning to a more traditional liturgy that expresses the awe, majesty, splendor and reverence of communal worship. He says many people tell him they were missing what St. Peter provides.

At St. Peter restoring the sacred means:

• integrating Latin into elements of every Mass, both English and Spanish

• performing traditional sacred music and chant

• using incense

• worshipers receiving communion at the altar rail

• multiple clergy and altar boys participating

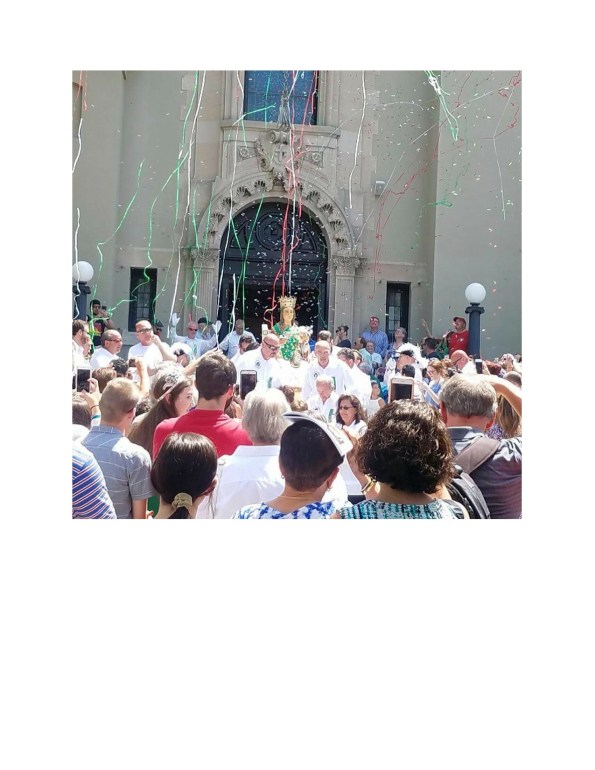

Additionally, St. Peter offers daily confession and chanted vespers. Each spring it conducts a festive Corpus Christi procession that follows a 1.4 mile route. As a canopy covered vessel containing the Eucharist is carried, children strew the path with flower petals, music plays and prayers are recited aloud. It all culminates in fireworks, song, food and thanksgiving outside the church.

Cook says parishioners embrace these rites and share their enthusiasm with others, which in turn helps St. Peter grow attendance and membership.

“I just feel really blessed,” he says. “There’s always been faith here, and I inherited that from the priests who went before me. Even if the congregation was smaller the people here were really receptive to the whole evangelization process — of going out and telling their friends, ‘You should come down to St. Peter’s for Mass. Just try it once.’ And once people do they get kind of hooked.

“So the people themselves are the greatest gift to me. They really want to know more about the faith, they really do want the sacred and are excited about restoring the sacred.”

He says his congregation’s thirst for solemnity and spiritual nourishment is part of a universal yearning.

“If you look at every culture and religion in the world there’s a desire for the transcendent, for the sacred,” he says.

Challenges remain. Cook wants St. Peter to better link its English and Spanish-speaking parishioners.

“I don’t sense any hostility between the two different cultures. We come together on various parish projects, but it’s still been very difficult. I’m still trying to learn the magic, the grace, the appropriate way to unite the two, because I don’t want there to be two different parishes. We’re one family of God. But the language difference is a reality. It’s just natural people feel more accustomed among their own.

“I sense unity here. but if we could only find the bridge for the Spanish and English-speaking segments to create that one parish.”

He also wants St. Peter to minister more to its distressed neighbors.

“We have everything from prostitutes at night on the corner to really inebriated people to aggressive panhandlers to shootings near us. We’re proud to be here as an anchor to the community. We’re privileged to serve the poor. We really do need to be out doing more evangelization because we have a whole neighborhood of people, Catholic and non-Catholic, to be invited.”

He hopes redevelopment happens for “the sake of more security, safety and opportunity” for residents. He firmly believes the area’s rich with potential, saying,

“It just needs people to realize that.”

Related articles

- Saving sacred sounds (life.nationalpost.com)

- US Catholics win rare victories on church closures (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- On The Latin Mass (acatholicdad.wordpress.com)

Open Invitation: Rev. Tom Fangman engages all who seek or need at Sacred Heart Catholic Church

In an era when Catholic priests are too often in the news for the wrong reasons it’s a pleasure to write about one who is highly respected by the church and by the community. The following article for Metro Magazine (www.spiritofomaha.com) about Rev. Tom Fangman is not the first I’ve written about this priest or the parish he pastors, Sacred Heart, in a largely African-American neighborhood in Omaha, Neb. But while those earlier pieces, which can be found on this blog by the way, deal with the rip-roaring Sunday service he presides over, complete with a gospel choir and band, and the multi-million dollar restoration of the church, this latest story focuses on him and his calling as a priest. He’s a sweet, gentle man who has managed the difficult task of not only keeping his parish church, school, and social service center alive but thriving in a district beset by profound poverty and high crime and an area hit harder than most by the recession. His winning ways with people from all walks of life, whether CEOs or parents just struggling to get by, is what makes him so good at what he does.

Open Invitation: Rev. Tom Fangman engages all who seek or need at Sacred Heart Catholic Church

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in Metro Magazine (www.spiritofomaha.com)

When Rev. Tom Fangman arrived as pastor at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in 1998, the northeast Omaha parish was already known for its humanitarian embrace.

If anything, though, this hometown cleric with a gentle, jovial demeanor has broadened and deepened the caring community he guides there by forever reaching out to others. Gladly receiving all, he asks people to give, aware that service to others heeds our better angels.

“I’ve always been a people-person,” he said from the cozy living room of the rectory he resides in behind the church. “I find so much joy being around people. I’ve just been blessed with good people in my life. Before I came here Sacred Heart was known as a very welcoming community, a place where people of all different backgrounds could go and feel a part of, a place where they feel they belonged. I am most proud that we’ve carried on in that same spirit. I know it’s a community, I know it’s a community that cares. We’ve maintained that charism.

“We’ve also been a parish that has always had a strong conviction towards social justice and serving the needs of others and providing for the poor. We are that place and we are a place that I know for certain impacts the community. We’re helping lots of young people. I’m really proud of what what we’ve maintained in continuing to do for kids.”

On a frigid Saturday morning in November, there was Fr. Tom doling out donuts, muffins and thank-yous to delivery drivers picking up Thanksgiving gift pouches for the parish’s twice-annual holiday food distribution. A record 330-some families in need received a turkey, plus all the fixings, for Thanksgiving. The operation, which runs with friendly, relaxed precision out of the parish’s Heart Ministry Center (HMC), is repeated for Christmas.

For the weekend chiller, the affable padre stood outside, bundled from head to foot, meeting and greeting volunteers, an easy conviviality and respect between the priest and his flock. Typically, he downplays his part, instead praising the large team that makes this compassionate response a reality.

“Being the pastor here is just kind of like orchestrating,” he said. “It’s recognizing people’s goodness and gifts and inviting them to offer themselves. If people are offered an invitation, they’re going to go with it. The things that happen here are because there are lots of really good people. They’re willing to get involved and to give of themselves.

“There’s lots of things I love about being a priest but one of the most exciting is when people become aware of God’s presence in their life, and no two stories are ever the same. Every person has their own journey and own ways that are revealed to them.”

He said he’s come to view his ministry as inviting people to give, whether their time, talent or treasure, in order to be of service to others. He said he’s often teased that he has a way about him that makes it impossible for anyone to say no.

“Well, there are people who have said no to me, but I’ve just kind of learned that shouldn’t stop you,” he said. “You go to the next place, you find the next person. I believe in the goodness of people. I also have high expectations of what people can do, and sometimes they really need that invitation to show that.”

Located at 2218 Binney Street, Sacred Heart serves the most poverty stricken area of the city through three nonprofit arms Fangman oversees. The most visible of these is the church, which originally opened at another site clear back in 1890.

The present stone, late-Gothic Revival church that stands today opened in 1902. Through Fangman’s leadership the parish was able to find the funds and in-kind contributions necessary for the building to undergo a $3.3 million restoration in 2009. He announced the capital campaign to fund the project in 2008. After making the case, folks responded, and within a year all pledges were secured.

More than a picture-postcard Old World edifice made new again, the church is a well-attended gathering place that draws worshipers, just as Sacred Heart counts parishioners, from all over the metro. The hospitality there is evident in the way newcomers are greeted. The Sunday 10:30 a.m. Mass is famous for its spirited celebration, complete with a rousing gospel choir and band. The animated “sign of peace” ritual includes hand shakes, salutations, hugs, kisses, as many folks circulate from pew to pew engaging each other. The fellowship resumes after Mass ends.

As a parish priest, Fangman is more than a spiritual figurehead. He’s a flesh-and-blood confessor, advisor, counselor, confidante, friend, leader, fundraiser and CEO. He serves his flock in macro and micro ways. He’s there at the most public and private, joyous and sad occasions. Hundreds of photographs of people in his life adorn every smooth surface in his kitchen, a reflection of how many he impacts and how many touch him.

“Being a parish priest lets you be involved in lots of peoples lives, from womb to tomb,” he said. “People say to me, ‘How can you be around so much sadness and death?’ I don’t know how to answer that but one thing I do know is that holiness is there in the midst of it, because that’s where love is.”

He fills multiple roles in the course of any given week: saying several Masses; hearing confessions; presiding, on average, over at least one wedding or funeral; visiting the sick; preparing couples for marriage; attending board meetings; calling on donors; and crafting his homilies.

He feels good about a lot of things that go on at Sacred Heart.

“I feel like we have a really great thing to sell, and I’m sold, I believe in what we’re doing and I’ll talk to anybody about that,” he said.

A shining example he never tires of touting is Sacred Heart Elementary School, a K-8 institution serving a predominantly African-American, non-Catholic student population. The school’s financial sustainability and operations are supported by the nonprofit CUES or Christian Urban Education Service, comprised of an “established board” of Omaha movers and shakers. Fangman is its executive director.

He said students at the small private school consistently test above average and that faculty and staff rigorously prepare students to succeed, adding that 98 percent graduate high school within four years. Mentors are assigned every student, all of whom receive work and life skills training.

Whether it’s the school, the church, or the center, he said, Sacred Heart is concerned with “addressing the whole person — body, mind and spirit.” Nothing satisfies him more than seeing the results come-full-circle in an each one, teach one way: “I get to see the goodness of people who want to make a difference, and then I get to see who receives from that goodness, and then what they do with that. Ultimately our goal is to give people opportunities. Sacred Heart is about opportunities.”

He said, “This young lady came up to me to say she grew up down the street from Sacred Heart, attended school here nine years, went to Duchesne Academy, then St. Louis University. She worked at First National Bank and she wanted to be a mentor here. To me that spoke pretty loudly about what we’re able to do, which is giving kids the opportunity to make it in life, to grow and discover what they have to offer. I want to see that continue on. I want to see those opportunities always given.”

The parish responds to social service/ human needs through Heart Ministry Center, home to the area’s only self-select pantry. Thousands receive free food, clothing, health care and other services from HMC each year. In 2002 Fangman consolidated its services on campus, raising $650,000 to build a new building.

Sacred Heart’s mission requires big money. The center operates on a $360,000 budget. The school budget is $1.3 million. Running the church/parish costs $500,000.

“That’s $2 million you have to somehow come up with,” said Fangman, adding that to secure that kind of commitment requires reaching into all areas of Omaha.

Three major fundraisers are held yearly. Holy Smokes is a pre-Labor Day bash benefiting HMC. It features barbecue, refreshments and live music. The Gathering is a sit-down dinner in support of the school. The Sacred Heart Open is a croquet tournament, battle-of-the-bands and barbecue to assist the church/parish. Two of the events began under Fangman’s watch and all three, he said, are well supported.

Thirteen years into his post, Fangman’s overdue for a transfer, but he doesn’t sense his work at Sacred Heart is finished yet.

“If I felt like we had done everything we were supposed to do, then I would feel like it’s probably time to try something new and different, but I feel like we’re on the verge of some really vital things happening.”

Whatever happens, he said, “I want to feel like I know I tried to make this a better place. I want to continue trying to get the right people in the right spots.”

To do the right thing.

Related Articles

- Social Change Chicago Style (Guest Voice) (themoderatevoice.com)

- A mission to promote health and wellness (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Omaha’s St. Peter Catholic Church Revival Based on Restoring the Sacred (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

St. Peter Claver Cristo Rey High: A school where dreams matriculate

Three years ago I did this story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) on the first Cristo Rey high school in Omaha. It’s a school where the students, mostly inner city Hispanic and African-American kids from families of little means, are required to work an office job to help defray the cost of tuition. The job is also an important learning avenue, exposing students to environments and experiences they would likely otherwise not see and helping them develop skills they likely otherwise wouldn’t feel compelled to cultivate. My story focuses on two students in the school’s inaugural freshman class, a Hispanic named Daniel and an African-American named Treasure. Although each tried to downplay it, their attending the school meant a great deal to them and their families. I may revisit the story of these two young people and their school next spring, when Daniel and Treasure, both of whom are doing quite well in the classroom and at the work site I am told, are set to graduate.

UPDATE: As updates go, this one is decidedly sad: In early February the Catholic Archdiocese of Omaha announced that St. Peter Claver Cristo Rey High School will close at the end of the 2010-2011 school year due to the school incurring a $7 million deficit in its brief four-year history. It seems the school was never really able to gain enough traction, in terms of numbers of students enrolled. There was a high turnover of students who could not or would not follow the school’s strict standards. Ultimately though the recession of the last three years may have dealt the biggest blow because the school could not find or maintain enough jobs with local employers for its students to work once the economy sagged, thus severely cutting into the revenues the school needed to operate. Without those jobs, which defrayed the cost of tuition, some families simply could not afford what it cost for their children to attend. The more financial burden the school and the archdiocese took on to cover the gap and the shorter the school came to meeting its enrollment projections the more untenable the situation became. I will be filing a story in the spring that revisits the stories of Daniel and Treasure — who were part of the school’s first freshmen class and will now be part of its first and last senior class. With the impending closing it becomes a poignant, bittersweet story for all concerned, but it doesn’t diminish the quality educational experience students experienced.

St. Peter Claver Cristo Rey High: A school where dreams matriculate

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Few school startups have attracted the attention of St. Peter Claver Cristo Rey. From the time plans for the new Catholic high school in south Omaha were first announced in 2005 through the end of its first academic year next week, the institution’s captured public imagination and media notice.

Claver’s housed in the former St. Mary’s school building at 36th and Q Streets, within walking distance of the historic stockyards site, Hispanic eateries and markets and Metropolitan Community College’s south campus. The Salvation Army‘s Kroc Center is going up down the road where the Wilson packing plant used to stand.

That the school’s elicited so much response is largely due to its membership in the national Cristo Rey Network, a branded nonprofit educational association based in Chicago. 60 Minutes profiled it. The private CR urban schools model gives disadvantaged inner city children a Catholic, college prepatory education and requires they work a paid internship in white collar Corporate America.

Wages earned help defray students’ tuition and provide schools a revenue stream. Member schools share 10 mission effectiveness standards. Staff from CR schools around the nation attend in-service workshops.

Cristo Rey’s pairing of high academics with real life work experiences is why the network’s grown from one to 19 schools in less than a decade. Three more will open their doors next fall. The model appeals to families who otherwise can’t afford a private school, much less expect their kids to work paid internships. Communities are also desperate for alternatives to America’s public education system, where resources for urban schools lag behind their suburban counterparts. Students of color in inner city public schools struggle, fail or drop out at higher than average rates. Relatively few go on to college, much less complete it, and most lack employability skills beyond low paying customer service jobs.

So when something new comes along to offer hope people jump at it. That’s what the Mayorga Alvarez and the Anderson families did. The Omaha working class families, one Hispanic and one African American, fit the demographic profile the school targets. Claver’s kids mostly come from poor Hispanic or black households qualifying for the federal free or reduced lunch program.

Some whites, black Africans and Native Americans also attend. CR schools typically serve small enrollments. Claver’s no exception with 67 students.

The Mayorga Alvarez family and the Anderson family saw the school as a gateway they couldn’t pass up. After year one their views haven’t changed. Each family sends a child there. Daniel Mayorga Alvarez and Treasure Anderson are both honor roll students.

Claver internship director Jim Pogge said it’s easy to see how much this means to families. “I participate in almost all of the application interviews and the hope in the parents’ eyes is evident.”

Families also find appealing the prospect of being in on the ground floor of a new kind of school, a theme embodied by the Claver team nickname, Trailblazers. A sign in front of the school reads, “Become a Trailblazer.” A symbol and legacy in one.

“We call ourselves Trailblazers for all kinds of different reasons,” Pogge said. “This is a trailblazing school, the students are trailblazers in their own lives.”

Daniel Mayorga Alvarez said, “We’re kind of proud we’re the first class. I guess it makes us feel more special.” Among the downsides, he said, is that Claver “doesn’t offer all the classes I wanted.”

School president Rev. Jim Keiter said Claver’s expanding its courses and staff, hiring full-time music, art and reading teachers for next fall and adding CAD drafting, culinary arts and Microsoft certification classes as early as spring ’09.

Fr. Jim Keiter

Christopher Anderson made his daughter, Treasure, among Claver’s initial enrollees last summer. He liked the idea of her being in a school “totally different than what she’s been used to. The structure, the dress, the work ethic. I mean, I wish I could have gone to a school like this. And then you get to thinking she’s going to be part of the first class,” he said, beaming.

Each Claver student works a full-time shift once a week, plus one extra day per month. The school day runs from 7:50 a.m. to 3:55 p.m. Most students stay after school an hour or two. On work days, a student reports to school, is taken by cab to his/her 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. job and then returned to school. It might be 6 before they get home.

The curriculum includes a mandatory business class addressing office skills and etiquette. Students apply classroom lessons to the workplace. Back at school they share on-the-job experiences with fellow interns. Pogge works closely with the 22 employer partners in Claver’s Hire-4-Ed program. Student job performance is reviewed and graded. Pogge said, “It’s real. They can get fired.” That’s happened. In those cases students get retrained for new jobs.

“All of our students have to work in order to make this thing work. They have to be employable. The work component actually drives the school,” he said.

Claver sets the tone in the summer with a mandatory three-week long boot camp orientation that introduces students to school-workplace expectations.

When kids can’t or won’t meet expectations they’re asked to leave Claver. A number have been expelled.

“We have a very rigorous academic program. I mean, it’s college prep. There’s no deviation. It’s very linear in its focus. We also have this work component that’s very demanding. These kids have to perform but not everyone’s up to that task. Personally, I have kids this age and I wonder how they would do,” Pogge said.

On the whole, he said, the work study program’s met expectations. “We have had bumps, but we have had far more successes. As of February, 82 percent of our students received ‘Good’ or ‘Outstanding’ job performance ratings.”

Students who do well on the job invariably gain confidence and maturity.

“We see it in changed behaviors here at school,” Pogge said. “They’re all of a sudden more focused, engaged. They communicate more effectively. They’re kind of coming out of their shell.”

Signs that Treasure’s growing up have surfaced since she started at Claver.

“She’s pretty mature. She missed a day of work, which they’re required to make up, and she made the arrangements without me asking her,” Anderson said.

Parents also like the strict dress code. Many students don’t. At Claver’s summer boot camp last August boys loosened or removed their required neck ties and girls pushed the envelope with revealing outfits. Staff reminders and reprimands were common.

Maria and Rodolfo Mayorga Alvarez made Daniel, their youngest child, an early enrollee. A bright boy with a sweet, outgoing personality, he previously attended public schools in south Omaha, where he, his two older brothers and his folks live in a snug bungalow within sight of Rosenblatt Stadium.

His Mexican immigrant parents work blue collar jobs. Their formal education is limited, as is their English. Daniel serves as interpreter. Translating for his mom, he said: “She wanted me to go to a school that was a different environment, a whole new experience. She says the work I’m doing and the interactions I’m having and the skills I’m learning will be really helpful to me in the future.”

His mother’s noticed a change in him now that he comports himself like a little man. “She says I try to correct myself more. She sees me setting more goals for myself. She likes how the school is more disciplined.”

Daniel enjoys being in a brand new school with few students and much diversity.

“It’s like you’re starting all over with a clean slate. You get to know a whole new group of people. You probably get closer to people because you’re going through the same thing…you get stronger relationships,” he said. “In this school you get to know different types of people. You get diverse friends. We’re all scattered. We’re from north Omaha, south Omaha, southeast Omaha. Everybody’s got their own story — where they live, how they grew up.”

He finds Claver more taxing than what’s he’s used to. “I put a bunch more effort into this school,” he said. “It’s hard to keep up a B or A. I come home tired.”

Treasure also finds Claver challenging. She said, “It’s not always easy or fun to get good grades but you have to. I’ve had to learn how to balance school and work. I’ve got responsibilities both ways.”

She and Daniel are keenly aware that “it looks good on a resume” to have a college prep diploma and professional internship among their credits.

Treasure’s native Omaha Baptist family has a history of Catholic education. Her dad and aunts attended Blessed Sacrament. Her aunts then went on to Dominican High. Treasure went a year at Sacred Heart, where her two younger siblings now attend.

Although she mostly attended public schools Treasure’s one year at Sacred Heart gave her an inkling of what to expect at Claver, where weekly Mass and daily religious instruction are the rule. In the end, she said, “it’s still kids. We get along, we don’t get along. It’s high school.”

Most of her friends now attend Marian, a school too pricey for her dad to afford. “I surely couldn’t,” he said. All her Claver tuition’s paid by her job earnings.

A shy, inquisitive girl with a big spirit, Treasure lives with her two younger siblings, her father and his girl friend in a big house on Florence Boulevard in North O. Her older sisters live on their own. The family attends Morningstar Baptist Church.

Her dad is separated from her mom, whom she sees regularly. Chris works at Walgreens. He’s battled kidney disease for 14 years. Last summer both kidneys were removed. He’s now awaiting a transplant. A grown step-daughter may be a match.

Claver Admissions Director Anita Farwell said Treasure hasn’t let her father’s illness stand in her way.

“I love how she keeps her mind focused. She’s not distracted. No excuses. She loves her father. She wants to succeed not only for him but also for herself. He’s a terrific man and he’s built it in her as well.”

Treasure has strong role models. One of her half sisters is in college and another’s gone back. An aunt’s in the Army. Her parents both have some college. Now Treasure’s a model for her little brother and sister. Twelve-year-old Tera and 7-year-old Trey Christopher can’t wait to join her at Claver. Anderson’s already determined they’ll be future Trailblazers.

Reporting to a job adds a new dynamic for Treasure and Daniel. They work in guest services at Immanuel Medical Center, where several Claver students intern. They variously escort patients/family members, answer the phone and do clerical tasks.

“It can be boring but it’s preparing us and that’s what we need,” Treasure said. “We’re not always going to like it but it’s the real world. It does help me with my communication and organizational skills. It’s helped me open up a little to people.”

Pogge said students get to see new worlds.

“These kids are now going into buildings they normally just drive by. Now they’re part of the process,” he said. “They’re exposed to jobs, professions they may have never thought of before, and they can transfer skills from one job or industry to another. Communication skills, attention-to-detail, punctuality, stick-toitiveness.”

The work’s not always cut-and-dried, either. In Immanuel’s Diagnostics and Procedures areas the interns interact with strangers — adult patients or loved ones. Worry is etched on people’s faces. Daniel said many of those he escorts remark on how young he is and a conversation inevitably ensues about the school. Staff say having Claver kids in this role disarms people, putting them more at ease. Daniel views it as a life skills learning experience.

“As you talk to them you get to know them and to know a whole different story. You feel so sorry for them and you want to do everything to help them,” he said. “I really do like helping people. That’s probably the most satisfying.”

Once, a woman broke down and cried in the arms of Treasure, who consoled her.

“I had to be there for her, I guess,” she said. “I just couldn’t leave her there. She was going through some hard times. Her husband wasn’t going to live. I’m not the best people person but I did learn I have to suck it up and just be there for people in order to help them.”

The incident reminded her of her father’s precarious condition.

“If my dad just died one day who would be there for me? You gotta give in order to receive. So I try my best.”

“She doesn’t like to talk about it but I’m a realist, I know on any given day,” said Anderson, his voice trailing off. “So I always tell her, You know if something was to happen to me you would kind of be the glue to hold them together,” he said, referring to her younger siblings. “If your sister or brother were doing something wrong you’d say, What would Daddy say? I’ve raised her enough now that she knows what I expect of her and them. We talk about real things.”

Same for the Mayorga Alvarez family. They were due to make their next pilgrimage to Mexico this summer but tight finances postponed those plans. His parents don’t hide the fact it’s a struggle these days.

“When Mom’s right about to finish all the bills, to pay the school off, this off, that off, then all of a sudden something breaks down and we have something else to pay,” he said. “We always have this conversation. We feel we’re right about to hit the point when we’re living free and then something else happens. We’ll probably use the vacation money to pay off the truck so next year we’ll be a little more debt free.”

If the Mayorga Alvarez family don’t make it across the border this year it’ll mark only the second time in Daniel’s memory they haven’t. Their faith sees them through hard times. On Sundays the family attends St. Agnes or Our Lady of Guadalupe churches, whose congregations are filled with aspiring, upwardly mobile young families just like them.

The family’s hopes of moving up are pinned on Daniel’s shoulders, an academic star who envisions a medical career, perhaps as a doctor. He’s already found he far prefers office work to the roofing jobs he went on with his father and brothers.

“This is way better than that. I’d rather exhaust myself mentally,” he said.

Conversely, his brother Jesus was a less than stellar high school student who’s now looking for work. His other brother, Renne, a South High sophomore, is not excited by school but does plan on college. The brothers feel while Claver may not be for them, it’s right for Daniel.

“I think it’s good because it teaches the kids how to be responsible,” said Renne, who works at a Hy-Vee. “It gives them a taste of life — of how it’s going to be.”

Daniel said his mother often expresses her fondest desires for her boys.

“She wants us to become kind of independent, finish school, get good jobs, become better people. Even though both my parents work it’s still not enough to pay for everything. She wants us to do our part and to find our own way.”

Maria Mayorga Alvarez said she dreams of the ranchero she grew up on in a small, isolated village in central Mexico. Life was simple but happy there. She loves visiting home. She sees then how far she’s come. She hopes once her boys move on they’ll return to the family’s Omaha home and appreciate how far they’ve progressed.

Rodolfo Mayorga Alvarez’s poured his heart, soul and sweat into improving the small house. When his boys leave home they carry his and Maria’s dreams for better tomorrows.

Farwell admires how Daniel’s parents “have raised him to, ‘Do your best son.’ He loves them and he’s so thankful for what they’ve done for him. That is one of the motivating factors for him to do his best.”

Maria and Rodolfo Mayorga Alvarez and Christopher Anderson harbor the classic dream that their children do better than them. Their dreams are bound up in the promise of a school whose Catholic priest namesake tended to black Africans taken off slave ships in Colombia, South America. Claver reaches out to at-risk kids with a step ladder to success. Students, though, must make the climb themselves.

“All we’re really doing here is cracking open the door. It’s up to them to walk through it, run through it, and many of them are sprinting through it,” Pogge said.

As symbols go, what could be more dramatic than a school, with all its promise for new life, situated next to a burial ground, where dreams go to die? The east and south sides of Claver look out over St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery. Just beyond the cemetery South O’s booming economy is evident.

It’s not only kids and families inspired by the opportunities the school affords but teachers, administrators and corporate internship partners as well. Pogge said businesses see the connection between profit and opportunity.

“The corporate response has been outstanding. These companies have a real need for this clerical work to be done. Why not give our students a chance to perform and develop? Every decision maker I have met has told me they want to have a hand in developing the future workforce of this city,” he said. “These students will either be a part of that workforce or will fade away from it. If they fade away from it, then everybody loses. If they are actively engaged at a young age, then the future is very bright indeed.

“These companies believe these students have real and tremendous potential.”

Educators and employers want to be part of a journey that propels young people forward — past the traditional barriers in their path. As the Claver mantra says, “to serve those who desire it the most but can afford it the least.”

“It’s inspiring and humbling and exciting,” Pogge said, “It just makes absolute sense to give people a vision of what they can become, and that’s what this school is all about. It’s so tangible. It’s very real.”

“Our kids come from poverty and it’s really hard for them to see the consequences of getting an education or not getting an education and what it means to their future success or failure,” said Claver Principal Leigh McKeehan. “But when you expose them to careers then they can start putting two and two together and create a plan for their lives.”

The needs of Claver students are great. About half arrive below grade level, some two-three grades below in reading and math. While this first year was comprised solely of a freshmen class, some 16-17-year-olds were in the ranks of otherwise 14-year-olds. The older kids dropped out of schools at one time or another and desired what Keiter termed “a fresh start.”

Farwell said some kids come from single parent homes and others from homes where grandparents or guardians raise them. Kids may have moved several times.

“They’re 14 and they have gone through so much in life, they’ve seen so much,” she said, “and we’re trying to give them stability. We want them to know they can succeed. It doesn’t matter what their past has been. Go forward.”

“They can do it,” said Pogge, who refers to the entire staff as having “a calling” to this mission. Daniel said the staff’s dedication to “go the extra mile” is noticed.

Farwell said two of the school’s biggest selling points are its negotiated tuition and the transportation provided students to and from school (bus) and work (cab).

Interest is high. But the application-registration process can be daunting for Spanish speaking newcomers. Many parents work on hourly production lines and can’t easily arrange or afford missing work to fill out forms or go through school interviews. Claver’s simplified things by reducing the number of forms and expanding its hours — making admissions more of a one-stop process. Most Claver staffers speak some Spanish. A few, like Farwell and McKeehan, are fluent, which they say helps build trust.

Then there are the school’s high academic and accountability standards, which extend to students and parents signing a contract. Farwell said many parents expressing interest in the school the first year weren’t aware of its college prep rigor but adds that inquiries today seem more informed. That should mean fewer mismatches between the school and students and, thus, fewer expulsions.

As Keiter said he’s come to realize, “we can’t be the savior school for all students and families. Not every school is meant for every student.” He’s expelled 11 kids since August. Others withdrew after recognizing Claver was not for them. The attrition’s cut deep into the rolls of an already small student body.

When registration closed last summer Claver counted 106 students. Only 95 actually showed for the boot camp. By the time the school year began that number fell to 86. Enrollment now stands at 67.

Back in August Keiter already wrestled with “the savior complex.” One early morning he assembled the students at St. Mary’s Church across the parking lot and tearfully addressed them from the foot of the altar.

“Yesterday was probably one of the hardest days I’ve ever had. I removed four students from this school for behavior.”

He talked about the need to follow directions, make good choices and work together for the common good. Using the bad apple analogy, he said one or two rotten ones can spoil the whole bunch. Removing the students, he said, was “for the good of all of you.” He pledged he’d make more hard decisions as necessary.

“We have only one chance to set the bar and create the reputation of the school, and we want that reputation to be a school that is safe and a great learning environment preparing all our students for college and work,” he said.

Two of Daniel’s friends were expelled. “It was because of the dress code,” Daniel said. “I think for some of them it opened up their eyes. They’re going to come back next year hopefully. Their parents want to enroll them.” The dress code’s been enough of an issue that Claver’s introducing uniforms next year.

Casualties are inevitable.

“We are giving some second chances and they are excelling,” Keiter said. “That is what it is about, but for the whole to excel we will at times have to remove students who are not accepting or not wanting to accept this new way of learning at school and work. If they are disruptive, et cetera, it is not fair to those who are working hard to succeed.”

He said the school’s “being more diligent” about keeping standards high and not diluting them for the sake of “wanting to help or ‘save’ one. We have to be honest about who our school can serve best, not for our betterment but for each student’s betterment.”

Farwell’s actively recruiting freshmen and sophomores for next school year. Applications and acceptances are ahead of last year. June 12 and July 10 All Admissions days are planned. The boot camp’s being revamped to include a several nights retreat away from school that promotes relationship building.

Meanwhile, the school’s secured $5 million in its $7 million capital campaign and has renderings for a planned physical expansion.

Keiter said the strength of CR schools is their “outside the box” approach of being neither tuition nor philanthropy driven but enrollment and jobs driven. Aside from that bottom line, dreams most drive what goes on there. The long hours and stringent rules are not popular with kids but the ones that stay, like Treasure and Daniel, sense a higher purpose at work. They know how much is riding on this for their folks.

When Treasure omplains how hard it is her dad reminds her, “That’s the reason we chose the school — you’re getting more out of it.” Chris Anderson added, “Me and a couple other parents talk all the time about what a great opportunity it is. I could not be any happier. She’s excelling. I have faith in her and in the school.”

Related Articles

- Another Harlem Shining Star (harlemworldblog.wordpress.com)

- You: Progress slows in closing achievement gaps in D.C. schools (washingtonpost.com)

- Cristo Rey: Part of the Solution for Education Today (prnewswire.com)

- School for poor kids would make them work for tuition (thestar.com)

Related Articles

- Cristo Rey: Part of the Solution for Education Today (prnewswire.com)

- School for poor kids would make them work for tuition (thestar.com)

Contemplative Compassion

Sometimes a writer can shed light on a little understood facet of society or humanity, and through the prism of a story perhaps bring some new clarity and insight to the subject. That’s the task I set for myself with this story about a community of contemplative nuns who after a very long presence in my hometown of Omaha left for another city. Few people had even heard of much less knew anything about the Contemplative Sisters of the Good Shepherd. Their neighbors could only imagine what went on behind their semi-cloistered compound. In truth, the sisters for some time now have led rather community-oriented if not public lives thanks to relaxed restrictions. When I heard they were leaving the campus they occupied not far from where I lived and once attended church and school, I decided to explore for myself who these women were, how they lived, and what they did. In doing the piece I met an extraordinary woman, Sister Cecelia Porter, whose formidable spirit and gentle soul impressed me, and if I did my job right will impress you, too. The story originally appeared in the New Horizons and I am glad to share its bittersweet tale here.

Mary Euphrasia Pelletier

Contemplative Compassion

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

With the departure of the Contemplative Sisters of the Good Shepherd in November, Omaha lost an exceptional group of older women dedicated to a regimen of prayerful meditation, hard labor and good will. Due to advanced age, ill health and depleted ranks, this once large Catholic community of nuns has moved to the Good Shepherd provincial colony in St. Paul, Minn. While the sisters are gone, the legacy of their amazing grace endures.

The Contemplative Sisters of the Good Shepherd (CGS) is an international congregation founded in 19th century France by St. Mary Euphrasia Pelletier. The contemplatives, a branch of the Good Shepherd order serving marginalized women and children, maintained a presence in Omaha much of the past century. Originally called Sister Magdalens and, later, Sisters of the Cross, their first home here was on South 40th Street. They moved in 1969 to the former Poor Clare Sisters convent at 29th and Hamilton. When the huge old building became untenable a new convent was erected at 3321 Fontenelle Blvd.. Occupied in 1989, the new site was home to the contemplatives until last November. It is now for sale.

Consistent with the good shepherd mission, the sisters pray for the poor, the sick, the dispossessed or anyone else needing spiritual intercession. They accept prayer requests by phone and mail. All who call on them find refuge in their gentle house of hearts. From the quiet of their tree-shaded Omaha sanctuary, complete with chapel and dining hall, the sisters provided solace and support to countless petitioners. It is a mission they continue today from their bucolic St. Paul retreat.

Despite being an enclosed community, the sisters lead lives fully engaged with, not removed from, the world. Indeed, since Vatican II eased restrictions on religious orders in the 1960s, the sisters have enjoyed greater freedom. No longer a classically cloistered community bound by strict monastic codes of silence and isolation, the sisters have used the more relaxed rules to extend their grace to ever more souls. That has meant getting involved in the lives of persons pleading for help, including “adopting” families in distress and distributing food to the hungry.

Sister Barbara Beasley, RGS, an apostolic Good Shepherd leader in St. Paul, said, “If the contemplatives are really doing their job, which is all about spirituality, then they are connected with everything that’s going on. And that’s exactly the truth about these women. The proof of their contemplative life is that they are not turned inwards on themselves. They are the least turned-in people you can imagine. Their interests are outward. Before news of a crisis hits the paper they already know it because somebody has called up asking them to pray about it. They’re truly centered people. They know what they’re about. They know their calling is to pray for ministries, to pray for needs, to pray for everything. They are alert and responsive to what’s happening.” She said while there is no plan to do so, a small group of contemplatives could one day again be assigned here.

The oldest and longest professed member of the former Omaha community, 89-year-old Sister Cecelia Porter, CGS, finds people from all walks of life confiding in them. “They tell us many things. They talk on the phone for hours, especially people living alone. You’d be surprised who it is too. You can be rich and still be lonely. Sometimes it’s hard to listen. We have one sister, Edith (Hesser), who listens and listens and listens to every kind of problem under the sun and everyone just loves her for that,” she said. “One talent God has given me is to pray with others, and to pray with them in a way that they feel they are included in the making of the prayer. If I know your problems I can pray for you so deeply. I can pray almost out of your own hope. People tell me they feel encouraged and helped by that.”

A measure of the impact the sisters made here was the stream of friends and patrons stopping by the convent to say farewell and thanks in the days prior to the move. Denise Maryanski of Papillion spoke for many in describing the sisters’ amazing grace. “Nothing I do in my life, even raising four children, would be as hard as the work they’ve done and the dedication they’ve shown in their life,” she said. “These women are totally pure in spirit. It is perfection. They are as close to being saints on earth as anyone we have met. They just don’t seem to have ugly days. They deal with whatever they’re handed and they deal with it with this joyful spirit and heart. When you’re with them, you just smile. You can’t help it. Even in their darkest hours, dealing with life-threatening illnesses, the joy is still there. They accept the challenges God gives them. You never hear them say, ‘Why me?’ When life looks really ugly to me I think, ‘What would Sister Clare (Filipowicz) do? What would Sister Edith do?’ They’ve enriched our life and been an inspiration.”

As divorced Catholics-turned-Episcopalians, Denise Maryanski and her husband Tony cherish the unconditional love extended them and trace the success of their home construction business to the prayers granted them. “You don’t have to show your Catholic badge at the door. They’re not at all judgmental,” she said. “We know they’ve taken care of us too. Stressful things have happened in our family and in our business over the last two years and all we had to do was pick up the phone and say we were having some issue in our lives and they were right there praying for us. We attribute all our blessings to them.”

There is no limit to what the sisters pray for. “We consider ourselves responsible for the entire world, prayerwise, and we are very thoughtful to that,” Sister Porter said. “That’s one thing about contemplation — it widens the mind so much. We make our prayer fruitful by having an intention, a motive and a thought in mind. It can be a disaster, a tragedy or an accident or it can be people looking for better jobs or better marriages or better health. All of it is a matter for prayer. Whether we know the people or not, we put some spiritual power in their lives that wouldn’t otherwise be there. You never know for sure what your prayer does, but people do call and say, ‘Thanks, it happened.’”

Even with the world as their focus, there are special prayer causes. For example, Sister Porter prays for governmental leaders. And, as a group, they pray for their fellow religious. Sister Eileen Schiltz, RGS, an Omaha counselor who often attended Sunday mass with the contemplatives, said, “At mass they always remember all of our Good Shepherd sisters and ministers all over the world.”

For years, Rev. Lee Lubbers, SJ, of Creighton University, took turns with other Jesuits saying mass at the convent and has relied on the sisters’ mediation for various Jesuit-related endeavors. “It was important for me to count on their prayers for the non-profit educational satellite network (SCOLA) I started in 1981. I kind of count them as the founders of that whole operation, which has become a big network worldwide. I keep them praying for every development. I count on their support constantly,” he said. Typical of the sisters’ caring, he added, was their desire to visit SCOLA and minister to its staff, which they did every year. For him and others the sisters represented a comforting presence where “the important things in the universe were in touch at least, someplace, all the time.”

Rev. Lee Lubbers

In her work counseling abused women and children, Sister Schiltz often calls and asks the contemplatives to pray for her clients and senses a genuine interest in their plight. “I have never been let down. They always ask how the woman or child they’re praying for is doing.” She said the sisters have even taken under their wing children whose parents are imprisoned or deceased — sharing mass and meals with them. She said the sisters have not only provided a prayer-line, but a lifeline to those in need. “I wish I could find a donor for an 800 number so people could call them up in St. Paul and still have their prayers answered in Omaha.”

In a culture like ours, where tangible results are held sacred, something as ephemeral as prayer may seem like wishful fancy to a cynic. For Sister Porter, it is an article of faith. “You can’t see it. You can’t prove anything. The only thing you can live by is faith. But the things we can’t see are so real. Look at your radio or TV. Their reception is based on signals and waves. You can’t see those things, but do you doubt they exist? Or oxygen. You can’t see it, but by golly if you didn’t have it you sure would miss it. Just like those things, you’ve got to have faith your prayers will be heard. I believe with all my heart it can and does happen.”

In a loud, hectic world muddled with distractions, finding the time and space for quiet reflection can be a challenge. It is all a matter of intent and focus. Likewise, being contemplative is more than taking a vow or mouthing words. It means embodying one’s faith and spirit through expressions, thoughts and deeds. “Your entire life has to have a contemplative stance in order to produce any real contemplative fruit, because your mind does not snap like that from one thing to another, usually,” Sister Porter explained, snapping her fingers for emphasis. “You can wear the habit and say all kinds of prayers and do all this stuff and not change your character one bit. To me, it’s more of a thing of opinions and dispositions and actions and priorities. You have to have the depth to know you don’t live here just to wear a habit. It’s how deep you think. How deep you live.”

Sister Schiltz feels these women remind us what our spiritual life can be. “I think they’re a symbol. We need those symbols of contemplative life more than ever now because we’re so rushed and hurried. A lot of people long for that because the world is so chaotic. The contemplatives show it can be done. But it’s hard to live. It’s a gift that God calls you to. Some choose to answer it and some don’t. Maybe we can’t do it ourselves, but it’s something we can strive for in our own way.”

Ultimately, a contemplative life is a calling. Sister Porter heeded the call as a young woman. “I didn’t resist it. I was looking forward to more of the deep mystery of spiritual life.” But the story of how she came to follow her calling, like the stories of her fellow nuns, is probably not what you would expect. Born Thelma Porter in 1910 Portland, she grew up in Seattle. Her family, she said, practiced no particular faith and were in fact hostile to Catholicism. Her mother died when she was young and her stern father raised her and her two brothers alone. Despite her father’s opposition, she had Catholic schoolgirl friends and came under the influence of local Good Shepherd nuns, whose flowing white habits made them appear “angels.”

At 16, she left home to fend for herself. She only completed a couple years of high school before going to work. By 19, she decided to become a Catholic. Even though she admits she had a rather naive idea of the commitment she was making, she decided to not only take up the forbidden faith but become a nun as well. When she told her father, he disowned her. In her youthful arrogance, she defiantly turned away from him too. They never saw each other again. She also became alienated from her brothers and extended family. The separation hurt.

“As years went by I knew I hadn’t done the right thing. I could have handled it differently. It caused me much suffering and much bitterness. I felt it was my own fault. I was pretty unhappy about that part of my life.”

It was only as she matured she came to terms with what happened. By then, however, her father was dead, the bad feelings between them left unresolved. Amidst the sweeping changes of Vatican II, when many religious reexamined their vows and dropped out, Sister Porter too had an awakening that helped her overcome the doubt and acrimony and rededicate herself to her vocation.

“At that time I rethought my whole life and I came to the conclusion this life has got to be a better one if I live it right because I feel drawn to it. It must be what I’m meant to do.I dropped all the bitterness I had about my family. I realized you can’t undo what you’ve done when you’re young, no matter how much you regret it. The Lord sent me so much satisfaction with my life as soon as I let that go.”