Archive

Forever Marilyn: Gail Levin’s new film frames the “Monroe doctrine”

Marilyn Monroe has been the subject of countless articles, books, and films, and filmmaker Gail Levin, like so many other artists, has long been fascinated by the pop culture icon’s hold on us all these years. Levin made a documentary a few years ago about the Monroe mystique, examining still images of the actress as a way of taking stock of how the starlet and a handful of photographers she posed for over and over again were complicit in creating the intoxicating sex symbol she epitomized then and continues to represent today. I must say that even as a young boy I was completely taken by the Monroe package — her looks, her voice, her manner, her everything. For better or worse, I am still enthralled today. In fact, as I write these words a Marilyn poster hanging on my office wall fetchingly looms over me, her abundant bosom straining against the decolletage of a slinky evening dress, one strap having fallen down, and she lost in the reverie of anointing her porcelain skin with perfume. Marilyn, sweet Marilyn, the embodiment of innocence and carnality that has universal appeal. My story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) about Levin’s film is unavoidably also about Marilyn, a subject I don’t mind revisiting again, although I do tire of all the prurient conspiracy theories swirling about her untimely death. I think the truth is she died just as she lived – messily.

Forever Marilyn: Gail Levin’s new film frames the “Monroe doctrine”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Filmmaker Gail Levin is at it again. Only a year after the Emmy Award-winning Omaha native’s documentary on James Dean premiered on PBS as part of the American Masters series, she has a new Masters film set to debut on July 19 that tackles another, larger screen legend — Marilyn Monroe.

Another Monroe treatise? That cynical reaction is precisely what the New York-based Levin, a Central High School graduate, hopes to overturn with her new documentary Marilyn Monroe: Still Life, premiering next Wednesday at 8 p.m on Nebraska Educational Television.

Instead of yet another biopic approach to this much revisited subject, Levin’s “gentle film” examines the persistence of Marilyn’s image in pop culture as filtered through the canon of still photographs taken of her, photos that largely account for the potency of her sex goddess status 44 years after her death.

Long intrigued by how MM and the photogs who shot her crafted an image with such currency as to cast a spell decades later, Levin committed to the film after hearing Marilyn would have turned 80 this year; reason enough to delve into the ageless Marilyn forever fixed in our collective consciousness. The filmmaker dealt once before with MM — for her 2003 doc Making the Misfits, which looks at the intrigue behind the 1961 Monroe feature vehicle The Misfits, penned by her then-husband playwright Arthur Miller.

On a recent Omaha visit to see family and friends, Levin spoke to the Jewish Press about her new project and the Monroe mystique that still beguiles us. She said MM is a much-referenced figure all these years later “not because of the movies” but “because of all the photographs” — photos the image makers and the icon used to their own ends.

“She made herself quite available to photographers and the list is just endless. We sort of picked a path through this huge archive of photographs,” said Levin. In addition to being “perhaps the most photographed woman of the 20th century,” there are MM-inspired books, articles, songs, videos, “and I was interested in what motivates all of that,” Levin said. “The masters part of this American Masters is as much these great photographers as it is her. It’s kind of book-ended by the great Eve Arnold and the great Arnold Newman. These are two giants of 20th century photography.”

Not just noted photographers contributed to her image. The film includes pics by Ben Ross, “whom none of us had ever heard of before,” Levin said. “He was one of these itinerant photographers from the 1950s and his photographs of her are stunning.” At least one of the artists whose images of MM are featured, Andre De Dienes, was also her lover. “He really knew her from the time she was probably about 20 to the time she died, and shot her all that time, and had a big romance with her,” Levin said. “There’s some very beautiful young stuff with her.”

There’s the ubiquitous Andy Warhol take on Marilyn in the film. Some images are quite familiar but others are new, at least to a general viewing audience and, Levin predicts, some images will even be new to Marilyn and photography aficionados.

Besides interviews with top photographers who helped shape MM’s image, Levin’s film features comments from Norman Mailer, Gloria Steinem and Hugh Hefner. There are even audio excerpts from the last interview Marilyn gave.

Levin said former Redbook editor Robert Stein provided a key insight into MM when he told her “she was an odd combination of innocence and guile.” As Levin has come to find, “I think a transcendent aspect with her is this real genuineness. I think she was completely approachable and accessible…You could be no one and talk to her and you could get into her bed. I think there’s something about her that is completely open, completely accepting. Burt Stern’s assistant was 22-years-old when Stern took photos of her and he said, ‘I was at the bottom of the totem pole and yet she was so kind to me and so sweet to me.’ And people say that across the board about her. Marilyn Monroe was not an imperious bitch. She was not a diva. That’s not who she was. She was a very real person. She was an Everywoman. She really was.”

The invention of her image did not happen by chance. Nor did she play a passive role in its creation. She owned her image and, if not the negatives, then what they conveyed. “This was very deliberate. This wasn’t an accident,” Levin said. “She got it and she had it and she made it and she knew it. She was not guileless because she was not stupid. She manufactured this image brilliantly. It was a calculated image, but with good heart, with good intent, with good will.”

Levin feels it’s wrong to apply a feminist prism in viewing Marilyn as a victim of misogyny or unenlightened ambition. “This was a guy’s woman. She liked guys. It was not against her will,” Levin said. “I don’t think she felt victimized at all. I think she exploited it in every way.”

The story of the famous calendar nudes she posed for as an unknown, later published in Playboy at the height of her stardom, reveal an MM in charge of her own image. “Hefner makes the remark that nude photos in those days could take you down. But when they came out she stood right up to it,” Levin said. “Her whole attitude toward it was, This is life. She wasn’t ashamed of any aspect of her body or her being.”

Ironically, Levin was forced to pixilate the nipples and other body parts in the wake of the Janet Jackson breast flash, even though, as Levin argues, the MM nudes are “not pornographic, they’re not slutty, they’re absolutely beautiful. They’ve been made ugly by other people.”

What transpired with the nudes, which made others rich while MM never got a residual dime over the $50 modeling fee, mirrored her life in the spotlight, Levin said. “I think people were rather cruel to her and I think she was hurt. But I also think she was defiant in the face of it. She was courageous. I think the soul of her was terribly resilient.”

Much of the film refers to the sessions that produced the images that still transfix us today, including The Seven Year Itch shoot. In these settings MM willingly gave herself over to the camera. She projected a playful woman-child persona, both real and acted, as she also asserted influence over what final images would see the light of day. Perhaps nothing else gave her such a sense of self-determination.

“You see that she loved it. It was her best relationship, really. It was really the place where she was most comfortable and had the most control,” Levin said. “She very much had control of her contact sheets. She would edit them. She was notorious for Xing out photos in red lipstick or marker. Eve Arnold says in the very beginning of the film, ‘This was her way of working and even though I was free to do what I wanted, she really controlled the image.’”

As Marilyn evolved from aspiring actress to star “she understood what it was she wanted” and she pursued specific photographers she knew “could do her justice,” Levin said, “and got herself in front of those people and, of course, those people wanted to photograph her. They considered her a great subject. It was the perfect metier” for a photographer-subject to play in.

A model must make love to the camera for the images to last. MM invested her photos with rarely seen rapture. “Eve Arnold comments there were a lot of four-letter words used to describe the way she seduced a camera. She loved to do it and she did it great,” Levin said. “Marilyn’s take, which I think is the critical take, is she just thought it was great to be thought of as sexual and beautiful. And why not? I think any woman would want to look like that for five minutes of her life.”

For Levin, one particular image encapsulates Monroe in all her complexity.

“We open the film with a dark room sequence in which we print a photograph of her,” Levin said. “It was taken by Roy Schatt during the time she was in the Actors Studio in New York. Her face is completely open. No makeup. You see that sort of Norma Jeane plainness, really. There’s some pictures of her, like this one, that when you look at them you think, Whatever gave her the idea she could pull this off? She’s OK. She has a cute, sweet face, but hers was not a remarkable face. At the same time you see right through that to the whole iconography of Marilyn Monroe. I chose this picture because I thought it emblematic of the whole of her being.”

Like any fine actress, and Levin ranks MM “a great comedienne,” she could summon her public persona on demand. As Levin tells it, “There’s a known story of her walking down a New York street incognito and saying to her friend, ‘Do you want to see her?’” Meaning Marilyn Monroe, superstar sex symbol. The shape shift only took a subtle change — to a more free, less uptight bearing. The power of it bemused and bothered her. “I think she lived in that schism.”

Taking on as familiar a figure as Monroe and all that “we bring to her” scared Levin. “It’s the hardest film I’ve ever made. This material has been so manipulated in so many ways. The challenge and the task is how do I take this and make this something you feel is completely fresh?” In the end, she feels she’s captured the essential Monroe. “We started out liking her and we ended up loving her. We tried not to take anything from her. She looks so beautiful in this film.”

Levin’s Marilyn will have multiple showings, along with her James Dean, the last two weeks of July. Check local NET1 and NET2 listings for dates/times.

With two movie icon subjects behind her, one might expect Levin to tackle another, but her next film may key off a documentary she worked on last fall. From Shtetl to Swing deals with the great migration of Jews from Russia and Eastern Europe to America and their development, with African-Americans, of the music style known as swing. Slated for Great Performances, the film was delivered in less than airable condition, causing series officials to call in Levin to do some “doctoring.” Her work helped the film get “the highest ratings in New York in years for a Great Performances. One of the things I’m planning on next is something similar to that, but on Latin music and how it’s transmorgified into the culture.”

American Masters is produced for PBS by Thirteen/WNET New York. Susan Lacy is executive producer of the acclaimed series.

Related articles

- The Best Marilyn Monroe Shots You’ve Never Seen (stylecrave.com)

- Marilyn Monroe’s Famous White Dress Sold for $5.6 Million! (news.instyle.com)

- Michelle Williams Begins Her Week With Marilyn Monroe and Dominic Cooper (popsugar.com)

- My Marilyn Monroe Moment (comingeast.com)

Omaha’s Grand Old Lady, The Orpheum Theater

Most cities of any size that have at least some semblance of sensitivity for historic preservation still have an Orpheum Theater. My hometown of Omaha, Neb. is one such city, although the Orpheum here came perilously close to being razed at one point. Omaha’s track record for historic preservation is rather spotty, although it’s gotten somewhat better over time. I wrote the following article shortly after the local Orpheum was renovated for the second or third time and had come under new management. I will soon post a second piece I did around this same time, for another publication, that takes a different angle at the Orpheum and its opulent place among the city’s entertainment venues. For the first half of my life I only knew the Orpheum by catching occasional glimpses of its exterior during downtown shopping excursions with my mom or dad. Mainly though I heard about it through reminiscences by my mother and aunts, who frequented the theater as girls and young women, when it was still a movie palace. They made it sound so grand and special that I was always enthralled by their descriptions. I was actually well into my 20s before I first stepped foot inside. Right out of college my first job, albeit it a part-time gig, was as a gofer for a now defunct arts presentation group, whose programs were held at the Orpheum. I was supposed to be doing PR work but all I ever seemed to do, much to my frustration, was to fetch coffee for the haute woman in charge, or pick up poster orders or transport visiting artists, et cetera. But there were perks, particularly getting to see a string of world class performances, including Marcel Marceau, Twyla Tharpe, and the Guthrie Theatre. I’ve gone on to catch dozens of programs there — touring Broadway shows, operas, ballets, movies, you name it. I try to convey some of that wide-eyed excitement in my story, which originally appeared in the New Horizons.

Omaha’s Grand Old Lady, The Orpheum Theater

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

More stars than there are in the heavens.

That’s how the great lion of Hollywood movie studios, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, described the galaxy of stars under contact to MGM during cinema’s Golden Age. Omaha may be far removed from the bright lights of Tinseltown but for 75 years now one enchanted place — the Orpheum Theater — has been a magnet for some of the brightest stars of the big screen, Broadway, the concert circuit and the recording industry.

This grand old lady, fresh from a $10 million facelift applied last summer, opened in 1927 to a varied program featuring comedian Phil Silvers, violinist Babe Egan and her Hollywood Redheads and the silent film, The Fighting Eagle, starring matinee idol Rod La Rocque. From the start, the opulent Orpheum has seduced us with its eclectic attractions and extravagant motifs. The French Renaissance Revival style theater is a monument to Old World craftsmanship in such decorative flourishes as gold leaf glazings, marble finishes, velvet coverings, framed mirrors, crystal chandeliers and ornate Venetian brocatelle and damask-adorned chairs. The grand foyer is dominated by a circular French Travertine marble stairway that winds its way to the mezzanine and balcony levels.

The City of Omaha-owned theater, saved from an uncertain future in the early 1970s before undergoing a major overhaul, is now under the purview of the Omaha Performing Arts Society, a non-profit headed by Omaha World-Herald publisher John Gottschalk. The society, which will also manage the Omaha Performing Arts Center to be built across from the Gene Leahy Mall, has signed a 50-year lease with the city for the Orpheum’s use and will share, with the city, in any operating losses the next 10 years. Money for this most recent renovation came from private donations culled together by Heritage Services, a fundraising organization headed by Walter Scott, Jr. and other corporate heavyweights. These new developments are the latest efforts to reinvent the Orpheum over the past 107 years.

The present theater is actually forged from the facade and foundation of an earlier building on the very same spot. What began as the Creighton Theater in 1895 became the Creighton Orpheum Theater when it joined the famed Orpheum Theater Circuit in 1898. The original Orpheum operated until 1925. Then, when Orpheum officials decided a grander edifice was needed to support a growing Omaha, $2 million was spent extensively enlarging, altering and gentrifying the site.

Matching the Orpheum’s lavish decor, is a rich lineage of legendary performers who have appeared there, including many identifiable by only one name. From Crosby to Sinatra, crooners have made fans swoon and sway there. From Ella to Leontyne, divas have held court there. From Channing to Goulet, luminaries from the Great White Way have made grand entrances there. From Lucy and Dezi to Hope and Benny to Cosby and Carlin, comedians have made audiences titter with laughter. Magicians, from Blackstone to Henning to Copperfield, have bedazzled patrons with their wizardry. Classical musicians, from Stern to Pehrlman, have moved crowds with their sublime playing. Big band leaders, from Kaye and Kayser to Dorsey and James, have got the place jumping.

The Orpheum has been the home to the symphony, opera and ballet, the place where Broadway touring productions play and the eclectic venue-of-choice for everything from school graduations to Berkshire Hathaway stockholder meetings to movie premieres to appearances by top orchestras, renowned repertory theater companies and elite dance troupes.

The plush theater has been adaptable to changing tastes, beginning as a vaudeville house, evolving into a movie palace and lately functioning as a performing arts hall. During the Depression and war years theaters like the Orpheum were great escapes for people just wanting a break from the real world or just to find relief from extreme weather. In the vaudeville era several shows played daily, from noon to midnight.

When movies lit up the marquee, a typical program included a line of girls, a pit band, a newsreel and a first-run feature film. The theater’s Wurlitzer organ was a staple for sing-a-longs and silent movie accompaniment. When the big band craze hit, live music moved from the pit to the stage. If a hot band packed the house, it became the main attraction. If a big movie drew long lines at the box office, it took center stage. Trying a little something of everything, the Orpheum even ran closed circuit TV broadcasts of championship fights.

In its heyday its flamboyant manager, Bill Miskell, was known as “a show doctor” and “master of ballyhoo” whose advice could help a sick act get well and turn a sow’s ear into silk. Under Miskell, the Orpheum ran grandiose promotions — like the time the lobby was dressed as a railroad station for the 1939 world premiere of Cecil B. De Mille’s epic Union Pacific. In 1953, it became the first Midwest theater to project a Cinemascope picture — the religious extravaganza The Robe. From the 1950s through the ‘60s, the theater operated almost solely as a movie house.

Ruth Fox, a veteran usher and backstage volunteer, said the theater has a one-of-a-kind appeal. “It’s elegant. It commands dressing up. It makes you feel like putting on a long gown. What could be more regal?” Patron Mark Brown said, “I’m amazed by the splendor of the grand architecture and the acoustics. I don’t think it can be matched today.” Al Brown, a former on-site Orpheum manager, calls it “the crown jewel of the Midwest. It’s majestic.”

Former Omaha Public Events Manager Terry Forsberg, goes even further by describing it as “the cathedral of the performing arts as far as Omaha is concerned.” Indeed, the sheer grandeur of the place sets it apart.

Impresario Dick Walter, presenter of hundreds of shows there over the years, said, “Visually and mentally, you have to be moved when you see the size of the lobby and the theater. It takes your breath away a little. It’s like going into any of those grand palaces in London or Vienna or Berlin. And there’s an aura when you walk in the same space that so many scores of great performers of the past performed in. It’s the implicit tradition and the magic of the theater with its history. I don’t want to sound religious, but it’s semi-sacred.”

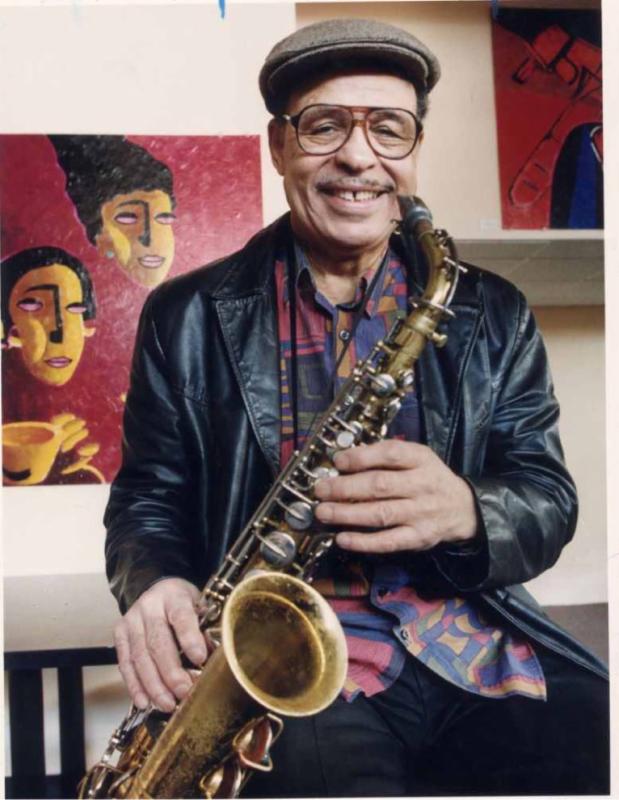

The Orpheum evokes many memories. Omaha musician Preston Love recalls getting his groove on there to the swinging sounds of jazz greats Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway, all idols for the then-aspiring sideman. “All the big names who toured theaters played the Orpheum,” he said. “Suffice to say…the Orpheum was top stuff, man. It was unbelievable.” He saw Count Basie there in ‘43, and three weeks later he auditioned for and won a seat in the band and ended up playing the Orpheum with Basie in ‘45 and ‘46, as family and friends cheered this favorite son’s every lick on the saxophone. He noted that a rolling stage utilized then carried featured acts to the lip of the stage. If it was a band, like Basie’s, those jamming cats really cut loose when they made it out front. “Boy, you started rolling down in front and that band would just be on fire,” Love said.

Dick Walter has a long relationship with the theater, first as a child lapping-up the antics of vintage comedy teams like Olsen and Johnson, than as a young man spellbound by big name entertainers and later as a presenter of performing arts programs, including everything from Camelot to The National Chinese Opera Theater. “When I was going to Omaha University I enjoyed cutting the Friday afternoon class to go down and see the first show of that week’s vaudeville show,” Walter said. Among the performers he caught then was the magician The Great Blackstone.

Decades later, in a “remarkable” bit of fate, Walter found himself presenting the famed illusionist’s son, Harry Blackstone, Jr., a great illusionist in his own right, in performance at the Orpheum. From the 1970s through the ‘90s, this local showman brought a diverse array of acts to the Orpheum, including scores of Broadway road shows. “Although I made a lot of money and I had great pleasure in presenting big-time musicals with big-time stars, I also enjoyed bringing the off-beat. I had some successes I certainly didn’t deserve and I had some failures I certainly didn’t deserve. Fortunately, I guessed right most of the time.” Although officially retired, he still dabbles in show business by presenting his long-running travel film series at Joslyn Art Museum and bringing occasional shows, such as “A Celebration of World Dance” and the Russian State Chorus, to Joslyn this fall.

As Walter can attest, show business is a series of highs and lows. For all the standing ovations and packed houses, he can’t forget the times when things went a cropper. “The biggest glitch ever was when I was presenting Hello Dolly with Carol Channing,” he said. “We had played a week when about a half-hour before the Saturday matinee show the entire electrical system went out. The emergency system came on, but it was too dim to do a show. It was a sold-out house, all of which had to be refunded. Miss Channing was really upset because she had never missed a performance. I said, ‘What are you worried about? This performance is missing you — you’re not missing it.’”

Carol Channing

With Channing mollified and the power restored, the second show went on without a hitch. In his many dealings with stars, Walter has found most to be generous. However, as “they’re pestered a lot,” he said, “all of the big people build a wall around them. They have no private life. Now, when you brought some of them in a few times, the wall broke down and the next thing you knew you were out eating dinner together after the show. A lot of them were wonderful with people coming up to them for autographs…and they should be — that’s part of their job. On the other hand, if people were a little pushy, they didn’t like that.” Among his favorites, he said, were comic musician Victor Borge, conductor Arthur Fielder, band leader Fred Waring and actor Hans Conried. “These people were special.”

Regarding Waring, Walter recalls, “The last time I had him was his ‘Eighth Annual Farewell Tour.’ I used to kid him about that. He just kept going on as long as he could. That last time we had him he gave a wonderful show and, when he came off, he was literally so exhausted he just fell into my wife’s arms backstage, catching his breath. But seconds later he was back on stage thanking everyone. That’s show business. That makes a performer.” When it came to Conried, who headlined a straight dramatic play for Walter, the actor so enjoyed a repast at the Bohemian Cafe that whenever he hit the road again “he’d drive up, give me a ring and say, ‘Let’s go to the Bohemian.’ He thought this was heaven.”

Ruth Fox recalls going as a little girl with her mother to the Orpheum and being awe-struck by the great hall. “I was so impressed with the mirrors and the chandeliers.” she said. “Oh, that was something to behold.” A lifelong theater-lover, Fox began ushering and working backstage at the Orpheum in the 1970s. “I started to usher for the symphony, the opera, Broadway touring productions and whatever else came.” It’s something she continues today. She enjoys being around theater people and the hubbub surrounding them.

“I find it thrilling.” As an opera guild member, she joins other ladies running a backstage concession for cast and crew. “We fix homemade food. Matzo balls, deviled eggs. You name it, we have it. We have a real thing going. We spend time with the performers. We take care of their needs…and they’re so nice to us. Once in a while you get a stinker, but most are wonderful.” She takes great pride in her role as an usher, too. “We, who usher, really are ambassadors to the city. There are so many people who come from out of town who have never been to the Orpheum before. It’s their introduction, you might say, to Omaha…and we have to make a good impression.”

Despite the theater’s prominence, its future was once uncertain. By the end of the ‘60’s it languished amidst a dying downtown. Ownership changed hands — from the Orpheum Circuit to several movie theater chains. As business declined, the theater fell into disrepair and, following an April 29, 1971 screening of Disney’s The Barefoot Executive that played to a nearly empty house, the place closed. At first, there was no guarantee the theater would not follow the fate of another prominent building in Omaha, the old post office, and be razed. Its prospects improved when the Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben bought the theater and donated it to the city, which agreed to steward it.

The city formed the Omaha Performing Arts Society Corp. (no relation to the current management group) for raising revenue bonds to underwrite a renovation. Local barons of commerce contributed more dollars. Everything was on the fast-track to preservation until the city learned it had inherited a $1,000 a month lease for use of the lobby from the City National Bank Building, which the Orpheum abuts. With the rental issue gumming-up the works, the theater — then lacking any protective historic status — became a white elephant and, some say, a likely candidate for the wrecking ball. It was saved when the Omaha Symphony bought out the lease and deeded the lobby to the city.

A multi-million dollar renovation ensued — removing years of grime, repairing damage caused by a leaky roof and restoring deteriorated plaster and paint — before the Orpheum reopened as Omaha’s performing arts center in 1975, with Red Skelton headlining a glitzy gala. Later, it was designated an Omaha landmark and a National Register of Historic Places site. Over the next 27 years, the theater thrived but not without complaints about acoustics, amenities and overbookings. The theater also operated at a loss for many years.

Two men who know every inch of the theater and have spent more time there than perhaps anyone else are Al and Jeff Brown, a father and son who have made managing the Orpheum a family enterprise. Al, a tattooed Korean war vet, was on-site manager there from 1974 to 1996, during which time he saw the theater enjoy a renaissance. When Al retired, his son Jeff, who worked at the Orpheum as a stagehand like his dad before him, followed in his footsteps to assume responsibility for the day-to-day operation and maintenance of this heavily-used old building in need of faithful attention.

The hours on the job can be so long that Jeff, like Al did, sometimes sleeps overnight on a cot in the office. Jeff feels the work done to the theater this past summer, which tackled some longstanding problems, will be appreciated by performers and patrons alike. “The big thing is to keep both of them happy,” he said. “I feel with this renovation we’re going to better realize that goal because of the areas we’ve addressed…improved seating, enlarged and added dressing rooms, added women’s restrooms, a new heating-air conditioning system. Before, we did the best we could with what we had, but now it’s going to be much more user-friendly.” Keeping show people happy, whether local arts matrons or visiting world-class artists, means making sure everything behind-the-scenes “has to be the way they want it,” Al said. “Touring performers come into town and they’re tired. It’s a drag. Anything you can do to alleviate some of that, they appreciate it.”

He said temperamental stars become pussycats if a manager and crew are prepared and have gone the extra mile. Echoing his father, Jeff added. “If you do your homework before the show and you make sure that everything is clean and you have everything they ask for, they’re very pleasant to work with.” Something Jeff learned from his old man is “treating every show the same — it doesn’t matter whether it’s a school graduation or a dance recital or a big Broadway show. We do whatever we can to make sure they have the best show they can have.”

Jeff said the theater’s new management structure bodes well for the facility. “I feel it’s better because our budget isn’t affected by what happens at Rosenblatt or at the Auditorium. We’re our own separate entity now. We’re on our own and we know we have to make it on our own. It will be a challenge, but I think it will be good.”

The Orpheum, saddled with recent annual operating losses in the half-million dollar range, will more aggressively seek and promote high stature events and market the theater as a destination place. An Orpheum web site is in the works. It also means Orpheum performance seasons — complete with public subscriptions — may be in the offing. It’s all been tried before. But the performing arts society may be in a better position to pull it off than financially-strapped city government.

Terry Forsberg said, “Now that you have a private group and the financial backing of the business community, it can be done. The question will be how much of a profit they will have to show in order to keep it operating.” According to John Gottschalk, “The Orpheum will have an endowment, but we’re certainly in no position to absorb half-million dollar losses every year. So, we’ll need to operate effectively and efficiently. The best way to end the…losses is to have a diversity of performances and to have bigger houses more frequently…and we will be heavily employed to make sure this place is full and active.”

Everyone, it seems, holds the Orpheum in high esteem. For Gottschalk, its rich legacy makes it a vital touchstone. “In the first place, it’s an incredibly old symbol,” he said. “There’s been an Orpheum Theater here since the turn of the century. Its longevity is what makes it such an integral part of the fabric of the community.”

Showman Walter said “it’s great to be part of this theater and it’s wonderful heritage.” Omaha Performing Arts Society president Joan Squires calls it a real treasure for the city.” Theatergoer Marjorie Schuck describes it as “a very big asset for Omaha culturally,” adding, “It’s a highlight coming to the Orpheum…it’s been here a long time, it’s still here, it’s still going, and we expect it to continue.”

Perhaps thinking of the effect the planned downtown performing arts center may have on the Orpheum, volunteer Ruth Fox said, “I just pray they will not tear it down or change it.”

Pray not, indeed, for that would be too much to bear. As a program for the Orpheum’s 1927 opening noted, the theater “is a continuation not only of a place of amusement, but also a veritable civic institution.”

Related Articles

- Ghost Hunting at the Orpheum (tdhurst.com)

- Musical Theatre Shows in Chicago (north-american-musical-theatre.suite101.com)

- Omaha Arts-Culture Scene All Grown Up and Looking Fabulous (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Quiana Smith’s Dream Time (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Re:Take: The Orpheum Will Rise Again (seattlest.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Grows in New Directions (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Kevyn Morrow’s Homecoming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Shakespeare on the Green, A Summertime Staple in Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Ushers in New Era of Omaha Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Ron Hull’s magical mystery journey through life, history and public television

For years I only knew Ron Hull through the prism of television. He was an affable, erudite executive and sometime host on the PBS affiliate in my state, Nebraska Educational Television. I knew that he was a friend of Dick Cavett‘s and over the years I prevailed upon Hull more than once for his help in contacting Cavett for various projects I was working on. But it wasn’t until a couple years ago I finally met Hull, who proved as amiable and generous in person as he was by phone. I long wanted to profile him but had never quite gotten around to it. Then a couple things happened: In the course of interviewing Cavett, the former talk-show host mentioned some things about his longtime friend Hull that peaked my interest even more; and then I read a local newspaper story about Hull that hinted at some colorful origins I wanted to flesh out in more detail. That’s exactly what I do in the following profile, which originally appeared in the New Horizons. By the way, this blog site also contains some of the articles I’ve written about Cavett and at least one of those pieces references Hull.

Ron Hull’s magical mystery journey through life, history and public television

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Only recently has Nebraska Educational Television pioneer Ron Hull, 77, come to appreciate the remarkable arc of his life, one that’s literally gone from bastard child of a bordello to chairing the board room.

“I went from that situation to this situation. It’s incredible when you think about it,” Hull said from his NET office in Lincoln.

His journey’s taken him around the world, introduced him to legends, given him access to inner circles of power and allowed him to indulge his love for the arts, the humanities and history. Perhaps none of it would have happened if not for the kindly madam, Dora DuFran, whose house of ill repute he began life in.

He’s come a long way from that dubious start in a Rapid City, S.D. den of inequity. He never knew his real parents. His adoptive parents, who got him as an infant, gave him a good home in town. His father was a mechanic and his mother, a former country school teacher, a realtor. His dad opened his own garage and used car lot. His folks made extra money buying old properties and renovating them for resell.

“There was never any doubt about how much they thought about me. I couldn’t have had better parents,” Hull said. “Coming out of the Depression my parents had nothing except each other and lots of integrity. But they really worked hard. They were very industrious people and they gave me every opportunity. I’m very lucky.”

From such modest roots, he’s forged a substantial public television career here and in the nation’s capitol. The Nebraska Broadcasters Association Hall of Fame inductee helped build the statewide NET network, considered one of the best in the PBS chain, and once wielded major influence in Washington, D.C.

In the course of his work he’s developed friendships with notables from the worlds of stage, screen, literature, media and politics. Talk show host Dick Cavett is a pal.

His much-traveled life has taken him from the Black Hills to Hollywood to New York City and back to the Midwest. Except when he worked back east as an executive with the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and with the Public Broadcasting System, Nebraska is where he’s made his home since 1955. There have also been extended stays as a guest lecturer in international broadcasting in Taiwan and as a television advisor to the government of South Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

The Lincoln, Neb. resident is still very much a citizen of the world. He’s as likely to be visiting favorite haunts in Manhattan or Los Angeles or off on some adventure in Asia, Europe or Africa as he is to be at home. He has friends all over the world.

After 52 years in public TV he’s still in the game. He serves as a special advisor at NET, where keeps a hand in programming, archiving, fundraising and just about anything he cares to involve himself in. He also teaches international broadcasting at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he’s a professor emeritus.

History, though, remains a top priority for the man who helped initiate The American Experience, the acclaimed documentary series that remains a PBS staple. He pushed for the series while director of the CPB Program Fund, a $42 million annual kitty he controlled and doled out to producers from 1982 to 1988.

His D.C. stint taught him the vagaries of power and politics. Producers seeking funding for their projects schmoozed him. He had to separate what was real from what wasn’t. “Every morning I’d get out of bed the first thing I’d say to myself was, ‘It’s the money they like.’ That really kept me on a pretty even keel.” The CPB board he reported to was comprised of Presidential appointees who displayed their partisan colors. As conservative Republicans exerted more influence, he left.

Back home he’s nurtured NET’s film production unit, whose Oregon Trail, Willa Cather, Standing Bear and Monkey Trial documentaries have aired nationally. He’s the founder and director of the Nebraska Video Heritage Library, an archive of thousands of programs that touch on life in the state over the past half-century. Among these gems are interviews with Nebraska writers John G. Neihardt, Mari Sandoz and Wright Morris, actress Sandy Dennis and entertainer Dick Cavett as well as coverage of legislative sessions, political campaign debates, et cetera. Hull’s enlisted Cavett’s interviewing-vocal talents for many NET and UNL projects.

The history bug first bit when Hull produced the NET series, Your Nebraska History, which led to an association with Sandoz, whom he convinced to do several shows. He’s headed the Sandoz Society. He’s served on the board of the Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial in Red Cloud. Then there’s his decades-long work with the Neihardt Center in Bancroft. He emcees the annual Neihardt Days. Neihardt was another key figure in the early life of NET, he said, as the poet’s appearances lent credence to public TV as a prime cultural source. Hull also led the Lewis & Clark Bicentennial Commemoration committee for seven years.

Hull’s made it his mission as a broadcaster to satisfy what he says is a basic human desire for people “to know who they are” and “where they come from.” He often refers to something Cather noted. “She said, ‘The history of every country begins in the heart of a man or a woman.’” These questions and concepts have taken on personal import for Hull ever since learning at age 15 that he’s adopted.

“I discovered it by accident…I found a birth announcement in my grandmother’s house. Of course she disavowed that. I’m sure she was so embarrassed. I have to hand it to all the relatives. Nobody ever talked. Nobody ever told me. Not my grandparents. Not my aunt who lived nearby. Nobody. They had to of known.”

He didn’t broach the subject with his folks right away.

“I didn’t have the nerve to ask my parents,” he said. “It was about a year later I went down to the courthouse to check the birth records because I knew I was born in Pennington County. I took my best friend. We said were on a school assignment and had to see our birth records.

“They looked up my friend’s. ‘Yep, here you are,’ the clerk said. Then my turn came. ‘You’re not here.’ I said, ‘Well, I have to be. I know I was born in this county. If I was born in this county and I’m not listed here, why not?’ The clerk said, ‘Well, I’m sure this isn’t your case, but illegitimate children aren’t listed in the county of their birth, those records are at the state capitol in Pierre.’”

The disclosure, Hall said, was “a big clue.” As those records were under seal, his search was stymied for a long time. Unable to keep silent anymore, he confronted his mother. She admitted the truth. “She told me as much as she could. She didn’t know much,” he said. “She had a friend, Mrs. Benjamin, who ran the social agency and she told her they’d like to adopt. She liked my mother” and an arrangement was reached to contact the Halls should a child come available.

From the time of these revelations Hull’s life’s been all about seeking answers. His search intensified over time. In 2002 he obtained a court order to unseal his birth records. The discovery of his true identity and the unusual circumstances that led to his adoption made his journey from townie to sophisticate all the more unlikely.

The brothel he entered the world in was owned and operated by one of the American West’s best-known madams, Dora DuFran. “She’s a colorful character. I’ve done a lot of research into her,” he said. DuFran got her start in the sex trade in Deadwood, S.D., that infamous frontier outpost of wild and woolly goings on.

A late 19th century immigrant from England, DuFran settled in Nebraska before making her way north to Deadwood, a gold rush town she cleaned up in. She expanded to run stables of sporting girls at brothels in Sturgis, Rapid City and Belle Fourche. Like many a successful madam she cultivated strong allies in the form of her gambling magnate husband, Joseph DuFran, and local authorities, whose ranks no doubt included regular customers.

It was in Deadwood DuFran befriended Calamity Jane, a former scout under William F. Cody, aka Buffalo Bill, whose Wild West Show she performed in. Renowned for her horsemanship, shooting and rowdy ways, Calamity knew iconic gunman-turned-lawman Wild Bill Hickok. A young Calamity once worked for DuFran and when down- and-out near the end of her life DuFran took her in. Hull’s link to the notorious DuFran and her historical cohorts is more than passing. Among other things she was a midwife and, yes, it turns out she delivered Hull. On his birth certificate the word physician is crossed out. Written over it is “midwife” and “Dora DuFran.”

“And I only know this because my mother told me,” Hull said, “but Dora DuFran carried me herself down to the Alex Johnson Hotel where the social office was and gave me to Mrs. Benjamin. Mrs. Benjamin called my mother up and said, ‘Come and get him,’ and that was me. So, anyway, I owe Dora DuFran a lot.”

As a teen Hull worked as a bell hop summers at the Alex Johnson. He didn’t know then his connection to it. “I always wondered what brought me to apply there, but I never figured it out,” he said.

DuFran’s Rapid City house also served as a popular speakeasy during Prohibition. Upon her death in 1934 the Black Hills Pioneer referred to her as “a noted social worker.” Her grave in Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood, which Hull’s visited, is near Calamity’s and Wild Bill’s plots. DuFran’s grave features four urns, each adorned with grinning imps in recognition of her four houses of pleasure. She authored a 1932 book entitled Low Down on Calamity Jane that contained her recollections of “the untamed woman of the wild, wild west.”

What Hull’s learned about DuFran, he likes.

“She was that proverbial madam,” he said, referring to her reputed heart of gold. “The sheriff, the police — everybody loved her. She’d be down at the railroad station on Thanksgiving bringing hoboes and bums back to her place to feed them Thanksgiving dinner. She was a midwife, she was a lot of things. And I was born in Dora DuFran’s house of prostitution in Rapid City. She had nine girls working for her at one time. It was a thriving business.”

This “back story” of unwanted pregnancy, abandonment and adoption has given Hull an inkling as to why he’s felt compelled to continually prove himself and why he’s rushed off to faraway places in search of some larger meaning.

“I can tell you one thing, I’m very sympathetic to anybody that’s adopted because if they’re like me you eternally wonder why somebody didn’t want you,” he said. “You could couch it another way. You can intellectualize it. She couldn’t take care of you, she couldn’t afford you, look how lucky you are…You can do all that, but the bottom line is — why didn’t they want me? And it hurts.

“It’s just something every adopted kid has to deal with…On the positive side, it’s a very powerful motivation to measure up. Am I going to be good enough? You always feel like you have to prove yourself. I decided I’d show ‘em.”

He feels strongly enough about giving lost children a home that he and his wife Naomi adopted their first child, Kevin. The couple added three children “the hard way.” Their son Brandon and his wife Linda continued the family tradition of adopting by flying off to China to bring home a baby girl, Eliza.

Hull continues trying to piece together his own pedigree. He knows the name of his birth mother, Jeanne May Ramsey, but doesn’t know if she worked as a prostitute at DuFran’s house or if she went there for help as “a girl in trouble.” He’s learned the name of his biological father, Paul Vaughn. Again, he’s unsure if he was a john or boyfriend or one night stand. He’s found his given name at birth was Theodore Vaughn Ramsey. Once adopted, his parents named him Kenneth, which he was called for a year or so, before they changed his name to Ronald.

However, he’s been unable to track down any more about his birth parents. “I have had no luck finding either parent,” he said. “I’ve really searched.” He just knows they weren’t married, which explains why his birth certificate has a box checked ‘No’ under the heading ‘Legitimate.’ He said the law changed at some point to remove “the stigma” of illegitimacy on birth records.

The intrigue of his own roots reminds Hull of life’s rich tapestry and how his work as a producer, director and programmer has tried to capture that richness.

He’s found a niche for himself in television, where he’s nurtured a lifelong love for the humanities, yet he fell into the field by happenstance. Still everything he did as a young man prepared him for his career.

Growing up in Rapid City his passion for the arts made him an odd duck. “I had certain proclivities for music,” he said. “I took piano. I loved theater.” He loved to read. His parents, meanwhile, “were not cultured people. They loved to dance, they loved to play cards. They had a lot of friends. They were very social. But I had the tickets to the concert series, to the Broadway theater league, they didn’t. All those things, from the time I was in the 7th grade, they saw to it I had them. You just have to say I was cut out of a different piece of cloth, and they knew that.”

He was delighted to move with his parents to North Hollywood, Calif. for his junior year of high school. “They always saw that as the end of the rainbow,” he said. “While I was perfectly happy out there my parents weren’t. It was just too hard for them to sever all the friendships, ties and everything. They realized they’d made a mistake.” He moved back with his folks for his senior year in Rapid City. It wasn’t long before he returned to Calif. — this time to study theater at the then-College of the Pacific. He gained valuable experience on stage in high school and college.

Hull once again went home, this time to please his strong Methodist parents by completing his theater studies at Dakota Wesleyan, a church-affiliated school in Mitchell, S.D. He and Naomi met there. Upon graduating Hull heeded the call many young people feel — to make it in the Big Apple. The military draft was hanging over his head and he, Naomi and friends opted to try their luck in New York.

“I just knew we had to get Manhattan under our belt. I knew an educated person had to have an appreciation for New York City — that’s the Acropolis of our culture. We all got jobs. Our intent was to see every play on Broadway and if we really saved our money — the Starlight Roof at the Waldorf Astoria.”

He also hoped to break into the New York theater world. “Yeah, that was always in the back of my head,” he said. Then, just as he feared, he got drafted. He wound up at Fort Sill, Okla., assigned to Special Services. He worked as a recreation equipment clerk — “…the most boring job in the world,” he recalled.

One day a sergeant came by and changed his life forever. A check of Hull’s file showed his theater background, which was enough for the young private to be offered a new job producing a TV show on Fort Sill for the post’s commander. Sensing a golden opportunity, Hull fibbed when he told the sergeant he knew something about TV when, in fact, “I didn’t know anything.”

Given only days to prepare a script, he went right to the base library to learn the basics. He spoke to a director at a local station to learn what cameras do. Before he knew it he was lining up members of the 89th Army Band to play music and signing up the wife of a major to sing in the studio. That just left interviews with soldiers coming back from or going off to Korea.

Producing-directing-writing-emceeing all came naturally to the then-22 year-old, which he chalks up to the fact that “I had a lot of experience in plays by then in summer theater.” He did 95 weekly TV shows before his hitch was over, enough experience to convince him he wanted a career in television.

“I thought, This is pretty good for me because, you know, television combines any aspect of life you want. I mean, there’s music, drama, culture, news, public affairs, documentary. It’s the whole thing.”

He used the GI Bill to study television at what’s now known as Syracuse University’s Newhouse School of Public Communications, where he earned a master’s degree. He’s since been invited back to speak as one of its distinguished alums. Naomi was with him at SU, working in the speech department. “That was a wonderful time in Syracuse. We loved it,” he said.

Hull assumed he would go into commercial broadcasting but while at SU he heard about this newfangled educational television “where you might do something, like Pollyanna, to improve people’s lives, and that really attracted me. Everybody said, ‘Well, you don’t want to go into that because you don’t make any money.’ They were certainly right about that,” he said, smiling.

He hit the road in search of a job, traversing the Midwest and South on a Greyhound Bus. “California was my goal — that golden green place out there,” he said. Except he didn’t go there. Instead, he stopped in Denver, Amarillo, Oklahoma City, Memphis, Atlanta and Chicago, leaving his resume everywhere he went, getting interviews here and there. Mostly he applied at commercial stations. Then he heard about an opening at the fledgling educational station in Lincoln, Neb.

“By this time I’d been on the road for about two weeks,” he said. “I was exhausted from the bus, from everything.”

He interviewed with Jack McBride, the father of NET and the man Hull considers his best friend. The final interview was with the university’s crusty old PR man, George Round. Hull, who had other offers, was noncommittal. Finally, Hull said, an impatient Round bluntly asked, Listen, do you want the job or not? Well, yeah, OK, Hull replied. “And I took the job,” he said. “I didn’t plan to stay here.” But Hull fell in love with Nebraska and its people. He’s remained loyal to his adopted state. He’s always returned to live here, even after extended stays abroad and back East.

“I don’t know if this place has claimed me but I certainly have claimed this place. It’s just who I am, you know. It’s where I established my family. It’s the values of the Midwest I revere. I think the people out here know how to work really hard and are basically honest. You can trust them.”

Among the first people he and Naomi met here were the parents of Dick Cavett. The Hulls, Cavetts and some other couples formed a social-cultural club called the CAs or Critics Anonymous, whose motto was, We criticize everything. A young Dick joined in on some of the activities. Hull and Cavett became close.

Upon accepting the state’s 2000 Sower Award for Humanities, Hull articulated the symbiosis he feels with Nebraskans. “We’re talking about relationships when we talk about the humanities,” he said “To me, relationships are the essence of our lives, the relationships that we have with each other…how fortunate I am, how thankful I am to have the privilege of being a part of you…in this state.”

In a real sense Hull feels he’s a steward for the state’s culture and history, not surprising when you realize he was there nearly from the start of what became NET. He arrived in October 1955. KUON had gone on the air only the previous November — the ninth public TV station to transmit. It was a humble launch.

“There’s nothing like starting at the beginning,” he said. “There were four of us. I was a producer-director, I wrote the continuity…You did everything. We were completely live. We had to be because we had no videotape, we had no network. We shared a studio with KOLN Channel 10. Our signal’s radius was maybe 35 miles.”

Live TV offered a visceral, ephemeral, enervating experience unlike any other.

“I really miss the live shows,” he said. “It makes such a demand on the people in front of the camera and behind the camera that you get a level of energy going all around. Every nerve ending is alive. It’s electrical. You can sense it, you can feel it. We used to say, ‘Poof in the night.’ You can’t replicate those experiences.”

On the down side, he said, “we made some terrible gaffes. You’ve got to be grateful there’s nobody to play those back.” A memorable one he recalled came when, “while introducing a travel film ‘live,’ our host, smiling into the camera, said, ‘Today we visit Hawaii — those lovely islands of beautiful beaches and flat sandy women.’”

Hull said video-digital technology not only eliminates the possibility of most mistakes, it “serves the viewer in the long run” by affording repeats. But he said live TV “was a little more honest” than today’s canned version.

He recalled an example of spontaneity that could never happen now.

“I was directing an interview with (Neb. Gov.) Frank Morrison, a big, lanky wonderful man. I’m sitting at the counsel (control booth) and the phone rang. ‘Hello.’ The voice at the other end said, ‘Ron, this is Maxine.’ ‘Oh, yes, Mrs. Morrison.’ ‘Tell Frank to sit up!’ ‘Yes, Ma’am.’ So I told the floor manager, ‘Make a big sign saying, Frank, sit up! — Maxine. I can still him going, Ohhhh…rolling his eyes and sitting up. Well, that’s live, interactive. It’s a different level of communication.”

“To me, one of the important things about public broadcasting is never to lose that local connection with local Nebraska people,” Hull said. “They own the station. So you’ve got to be in communication with them at every level you can be by listening to what they say and providing the things you think are useful to them and their lives. And we’ve always run this place based upon that.”

Legislative support for NET “has been wonderful,” he said. “They’ve provided us state-of-the-art equipment — millions of dollars worth. They believe in it.” Despite budget-staff cuts, NET boasts fine facilities, adequate resources and top talent.

Even as the Internet threatens TV’s hold on mass communication, the medium still reaches huge audiences and affords the possibility of informed public commerce.

“We’re trying and I think we’re getting closer and closer to make public broadcasting the central meeting place, the town hall where the issues are debated, where people have a say. I don’t detract from what commercial television does but we are the last vestige of local programming and documentaries.”

Where commercial TV once considered news-public affairs a higher calling, distinct from entertainment, he said it’s now part of the profit line along with situation comedies and reality shows. Networks and local stations don’t produce documentaries the way “they used to,” he said. “Those are expensive and nobody spends that money anymore. But you look at our schedule and we spend 600,000 bucks on Willa Cather: The Road is All documentary. That takes two years to produce but what you get is something that is worth people’s time to watch.”

Hull’s belief in the public service potential of TV remains undiminished.

“Television affects how people think. It goes right into their heads,” he said. “It is a terribly, terribly powerful instrument of persuasion that has the potential to be used for the good of the common man. I always identified with that from the beginning. The measure’s always been — Is this going to enhance somebody’s life?”

That doesn’t mean skirting hard realities or controversial subjects, he said, “because you have to show the other side of things and people have to be able to make up their own mind about things. But basically I have believed from the beginning we have an opportunity to make people’s lives better, to give people a perspective on the world and their place in it they can’t get any other way.”

He points to NOVA, Frontline, The News Hours, American Experience, American Masters and Great Performances as TV at its best. “To me, those series are the most thought-provoking, serious programs available to the American public.” Hull is proud, too, of public TV’s noyed work in children’s programming, led by Sesame Street, and how PBS has carried fare its commercial counterparts do not, such as American Playhouse, Meeting of the Minds, Steambath and Anyone for Tennyson?

New York producer Bill Perry had pitched his concept for Tennyson — mini-dramas bringing to life history’s great poets and their poems — to no avail until he approached Hull. “I liked the idea,” Hull said and the two put the series together at NET, enlisting such “brilliant actors” as Henry Fonda, Jack Lemmon, Claire Bloom, Irene Worth, Ruby Dee and Vincent Price. Hull became close friends with the show’s “first-class director,” the late Marshall Jamison. Hull, who calls the show “my favorite,” said it may have had a small audience but it made a big impact.

“I’ve never ever believed in measuring our success by the number of people who watch,” he said. “Rather you measure your success by what effect you had on people. It’s really hard to measure, but I prefer to believe there are people out there who learned from these programs.”

Similarly, he believes the programming he did in Vietnam made a difference. His experience trying “to win the hearts and minds” of its people gave him a new outlook on public service. Desiring an overseas adventure he parlayed state department contacts to get assigned a foreign service post as a TV advisor to South Vietnam. He was there in ‘66-67 and periodically the next few years to oversee construction and operation of stations in Saigon and outlying cities. Programming centered on public health and education — from potable water to immunizations.

The war raged around Saigon and casualties did not exclude those in the TV ranks.

“During the (1968) Tet Offensive all of our American engineers working at the Hue station were marched off and shot. I wasn’t in-country at the time,” he said.

He arrived in Vietnam a supporter of U.S. policy there but left convinced America “had made one of the major blunders in our country’s history.” He found distasteful the role that he and other Westerners played as outsiders looking in.

At the fancy Caravel Hotel in Saigon he and other noncombatants from the Free World bent their elbows at the rooftop Romeo and Juliet Bar. A frequent drinking companion was correspondent Peter Arnett. “We would look down at those streets to the Saigon River, the area beyond all controlled by the VC (Viet Cong). We would watch planes fly in and see the tracers any night of the week. The flares lit up the countryside. And we’re sitting there — who the hell are we? — drinking our little wine…I’m not proud of that,” he said. “But that’s the position we were in.

“Everybody who was there has to deal with the fact they were part of that war — I don’t care who you were or what your job was.”

Hull returned to Vietnam in 1999, in part to see the fruits of his labors there. Before going he was advised by foreign service veterans not to expect too much in the way of visible, tangible progress from the project he’d led.

He went to the very station in Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, he’d officed in decades earlier. He met with the station manager, a reserved man in a military uniform. The man answered Hull’s questions without any elaboration. Anxious to know more, Hull confided, “I was here teaching your people how to run this station in 1971-72. Where were you?” Hull said the manager “looked at me and said, ‘I was in Tay Ninh Province in the People’s Revolutionary Army. Mr. Hull, you and I were not on the same side.’ And then I knew where he was coming from. I said, ‘I knew what your people wanted. They wanted one Vietnam, one country. I am really happy you have your country.’ With that, his defenses went down. He showed me everything.”

What Hull saw impressed him. “My gosh, they had the news in French, Vietmanese, English. There was a ballet going on in one studio and the news being set up in another studio. The place was vibrant, alive and kicking, fabulous. I walked out of there with a happy heart. They’ve taken what we did and they’ve thrived.”

Asia is one of his favorite regions of the world. He occasionally visits China, where he stays with friends. On his last trip there he traveled via the Trans-Mongolian Railway from China to Russia, where he continued his trek on the Trans-Siberian Railway into Moscow. “It’s a fabulous trip. The cultures are fascinating,” he said. He continued on to Copenhagen to visit more friends. “I love travel,” he said.

An annual international broadcasting convention he attends takes him to exotic places. The next is set for Johannesburg, South Africa. He’s anxious to go — ever curious, ever eager to seek out new experiences.

“One of the secrets to having a good career is having a good time,” he said. “I always tell my kids, ‘If you’re not having a good time, you’re doing something wrong.’ It’s how I’ve lived. That’s the only way you stay healthy…”

Still, never far from his thoughts are nagging questions that may never find answers.

“I did find my niche in life, although I am forever this insecure, why-did-they-throw-me-away person who is still searching for Shangrila.”

Related Articles

- PBS chooses Bellingham to show sustainable economy (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- PBS Ombudsman Criticizes Shultz Series (mediadecoder.blogs.nytimes.com)

- PBS fund searching for Explorer-friendly pitches – RealScreen (countercultureprodco.com)

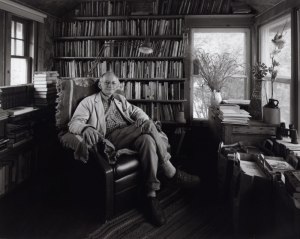

Author, humorist, folklorist Roger Welsch tells the stories of the American soul and soil

Roger Welsch is a born storyteller and there’s nothing he enjoys more than holding sway with his spoken or written words, drawing the audience or reader in, with each inflection, each permutation, each turn of phrase. He’s a master at tone or nuance. New Horizons editor Jeff Reinhardt and I visited Welsch at his rural abode, and then into town at the local pub/greasy spoon, where we scarfed down great burgers and homemade root beer. All the while, Welsch kept his variously transfixed and in stitches with his tales.

On this blog you’ll find Welsch commenting about his longtime friend and former Lincoln High classmate Dick Cavett in my piece, “Homecoming is Always Sweet for Dick Cavett.” Welsch shares some humorous (naturally) anecdotes about the talk show host’s penchant for showing up unannounced and getting lost in those rural byways that Welsch lovingly describes in his writing.

Author, humorist, folklorist Roger Welsch tells the stories of the American soul and soil

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the New Horizons

It’s been years since Roger Welsch, the author, humorist and folklorist, filed his last Postcard from Nebraska feature for CBS’s Sunday Morning program. Every other week the overalls-clad sage celebrated, in his Will Rogersesque manner, the absurd, quixotic, ironic, sublime and poetic aspects of rural life.

That doesn’t mean this former college prof, who’s still a teacher at heart, hasn’t been staying busy since his Postcard days ended. He’s continued his musings in a stream of books (34 published thus far), articles, essays, talks and public television appearances that mark him as one of the state’s most prolific writers and speakers.

In 2006 alone he has three new books slated to be out. Each displays facets of his eclectic interests and witty observations. Country Livin’ is a “guide to rural life for city pukes.” Weed ‘Em and Reap: A Weed Eater Reader is “a narrative about my interest in wild foods, a kind of introduction to lawn grazing and a generous supply of reasons to avoid lawn care,” he said. My Nebraska is his “very personal” love song to the state. “I believe in Nebraska. I love this place for what it is and not for what people think it ought to be,” he said. “I hate it when the DED (Department of Economic Development) tries to fill people full of bullshit about Nebraska. Nebraska’s great as it is. You don’t have to make up anything. You don’t have to put up an arch across the highway to charm people.”

In the tradition of Mark Twain and William Faulkner, Welsch mines an authentic slice of rural American life, namely the central Nebraska village of Dannebrog that he and artist wife Linda moved to 20 years ago, to inform his fictional Bleaker County. Drawing from his experiences there, he reveals the unique, yet universal character of this rural enclave’s people, dialect, humor, rituals and obsessions.

He’s also stayed true to his own quirky sensibilities, which have seen him: advocate for the benefits of a weed diet; fall in love with a tractor; preserve, by telling whenever he can, the tall tales of settlers; wax nostalgic over sod houses; serve as friend and adopted member of Indian tribes; and obsess over Greenland.

The only child of a working class family in Lincoln, Neb., he followed a career path as a college academician. His folklore research took him around the Midwest to unearth tales from descendants of Eastern European pioneers and Plains Indians. He lived in a series of college towns. By the early ‘70s he held tenure at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Then, he turned his back on a “cushy” career and lifestyle to follow his heart. To write from a tree farm on the Middle Loup River outside Dannebrog. To be a pundit and observer. People thought he was nuts.

“I walked away from an awfully good job at the university. People work all their lives to get a full professorship with tenure and…nobody could believe it when I said I’m leaving. ‘Are you crazy? For what?’ And, it’s true, I had nothing out here,” he said from an overstuffed shed that serves as an office on the farm he and Linda share with their menagerie of pets. “I was just going to live on my good looks, as I said, and then everybody laughed. That was before CBS came along.”

Before the late Charles Kuralt, the famed On the Road correspondent, enlisted Welsch to offer his sardonic stories about country life in Nebraska, things were looking bleak down on the farm. “We weren’t making it out here,” Welsch said. “I told Linda, ‘The bad news is, we’re not making it, and the even worse news is I’m still not going back.’ And about that point, Kuralt came along.”

No matter how rough things got, Welsch was prepared to stick it out. Of course, the CBS gig and some well-received books helped. But even without the nice paydays, he was adamant about avoiding city life and the halls of academia at all costs. What was so bad about the urban-institutional scene? In one sense, the nonconformist Welsch saw the counterculture of the ’60s he loved coming to an end. And that bummed him out. He also didn’t like being hemmed in by bureaucratic rules and group-think ideas that said things had to be a certain way.

His chafing at mindless authority extended to the libertarian way he ran his classroom at UNL and the free range front lawn he cultivated in suburbia.

“I was a hippie in the ‘60s and I really got excited teaching hippies because they didn’t give a didly damn what the bottomline was. They just wanted to learn whatever was interesting. You didn’t have to explain anything. I never took attendance. I’d have people coming in to sit in on class who weren’t enrolled, and I loved that. I hated grades. Because I figured, you’re paying your money. I’m collecting the money and I deliver. Now, what you do with that, why should I care? It’s none of my business,” he said. “The guy at the grocery store doesn’t say, Now I’ll sell you this cabbage, but I want to know what you’re going to do with it.”

Welsch said the feedback he got from students made him realize how passionate he was about teaching. On an evaluation a student noted, “‘Being in Welsch’s class isn’t like being in a class at all. It’s like being in an audience.’ I asked a friend, ‘Is that an insult or a compliment?’ ‘Well, Rog, actually being in your class isn’t like being in a class or in an audience. It’s like being in a congregation.’ And I thought, Oh, man, that’s it — I’m a preacher, not a teacher. It really is evangelism for me.”

“By the ‘80s they (university officials) wanted to know how they were going to make money out of the popular classes I taught. I said, ‘I have no idea. It’s not my problem. All I’m doing is telling them (students) what I know.’ So, there was that.”

Then there was the matter of UNL selling out, as he saw it, its academic integrity to feed the ravenous and untouchable football program, which he calls “a cancer.”

“I was and still am extremely disillusioned with the university becoming essentially an athletic department. Everything else is in support of the athletic department. And that breaks my heart, because I love the university. There was that.”

But what really set him off on his rural idyll was the 1974 impulse purchase he made of his 60-acre farm. He bought it even as it lay buried under snow.

“So, I bought it without ever really seeing the ground, but it was exactly what I wanted. I loved the river. I loved the frontage on the river. Then spring came and the more the snow melted…it was better than I thought….There are wetlands and lots of willow islands. The wildlife is just incredible. We’ve had a (mountain) lion down here and wolves just north of here.”

He used the place as a retreat from the city for several years. Each visit to the farm, with its original log cabin house, evoked the romantic in him, stirring thoughts of the people that lived there and worked the land. “That’s what I love about old lumber…the ghosts.” By the mid-’80s, he couldn’t stand just visiting. He wanted to stay. “I told Linda, ‘One of these days you’re going to have to send the highway patrol out, because I won’t come home. I can’t spend the rest of my life wanting to be here and living in Lincoln.’” Their move to the farm “really wasn’t so much getting away from anything as it was wanting to get out here.”

Then, too, it’s easier to be a bohemian in isolation as opposed to civilization.

“My life is a series of stories, so I have to tell you a story,” he said. “In my hippie days, I really got interested in wild plants and wild foods. As part of my close association with Native Americans, I was spending a lot of time with the Omahas up in Macy (Neb.). I was learning a lot of things from the Indians and, well, I was bringing home a lot of plants that I wanted to see grow, mature, go to seed and become edible. Milkweed and arrowhead and calimus. I got more and more into it. I loved the sounds and flowers and foods coming from my yard.

“One day, I come home to find a notice on my door that my lawn’s been condemned and I have six days to remove all ‘worthless vegetation.’ So, I invite the city weed inspector over to show me what’s worthless. He said, ‘OK, what about that white stuff over there?’ He didn’t even know the names of the plants. And I said, ‘Well, we had that for lunch.’ ‘How ‘bout that?’ ‘That’s supper.”

Welsch said, “As I started looking at this, I found out people were nuts. Anything over six inches high in Lincoln was a weed. The county weed board was spraying both sides of all county roads with diesel fuel and 24D. That’s essentially Agent Orange. They were laying waste to everything. Strawberries, arrowhead, cattails. So, I ran for the weed board on a pro-weed ticket. About this same time, Kuralt was coming through Nebraska. He asked somebody if anything going on in Nebraska might make a good story for his On the Road series. And whoever he asked, God bless ‘em, said, ‘Yeah, there’s a crackpot in Lincoln…’ So, Kuralt called me up and came over to the house with his van and his crew, which eventually became my crew. We sat down and had a huge weed salad and walked around and talked about weeds. And he had me on his On the Road. Well, then over the years every time he came through Nebraska he stopped. I kept a file of any stories I thought were interesting that he might use. That was my way of luring him to Lincoln.”

Charles Kuralt

The two men became fast friends and colleagues.

“We always went out to eat and drink. He loved to drink and I do, too. We would just have a good time. He used me for six more On the Road programs, for one thing or another. I tried to then steer him to other things — the jackalope in Wyoming and stuff like that. We got to be really good friends. When he started hosting Sunday Morning, he asked me to watch the show. He called me up and told me he wanted to bring the culture of New York City to towns like Dannebrog.”.

By the time Kuralt next passed through Nebraska to see Welsch, the author was giving a talk before a gathering of the West Point, Neb. chamber of commerce. What Kuralt heard helped him change the course of Sunday Morning and Welsch’s career. “He walked in the back of the room and listened to the program. We drove back to my place and he said, ‘You know, you said about 13 things we could use on Sunday Morning. What we need to do is to take the culture of a little town like Dannebrog and show it to New York City. So, that’s essentially how we got together. He originally thought about doing Postcards from America, where he had somebody (reporting) in every state. It got to be too expensive. I had six or seven years all by myself (with Postcards from Nebraska) before they added Maine. Then, by the time he went off the road, he gave me his old crew. They were like family. It was a great 13 years I was on that show. We had an awful lot of fun.”

Two years into Postcard, Welsch said Kuralt confided, “I thought we’d be lucky to get six stories out of Nebraska.” Ultimately, Welsch said, “we did over 200.”

What Welsch found in the course of, as he describes it, “my rural education,” and what he continues discovering and sharing with others, is a rich vein of human experience tied to the land, to the weather and to community. He’s often written and spoken about his love affair with the people and the place.

When friend and fellow Lincoln High classmate Dick Cavett asked him on national television — Why do you live in a small town? — Welsch replied: “In Lincoln academic circles everybody around me is the same. They’re all professors. In suburbia, everybody pretty much has the same income. But in Dannebrog, I sit down for breakfast and converse with the banker, the town drunk, the most honest man in town, a farmer, a carpenter and my best friend.” What Cavett and viewers didn’t know is Welsch was talking about his best friend Eric, who’s “been all those things. That private joke aside,” Welsch added, “the spirit of what I said is the truth.”

In his book It’s Not the End of the Earth, But You Can See it from Here, Welsch opines: “I like so many writers…have come to appreciate the power of what seems at first blush to be some pretty ordinary folks doing some pretty ordinary things. There is a widespread perception that small town life moves without color, without variety, without interest…but that has certainly not been my experience. My little town is like an extended family. There are my favorite uncles. A mean cousin or two. Some kin I barely see and do not miss. And some I can never get enough of.” It took leaving the city for the small town to find “the variety I love so much. The American small town seethes with ideas and humor, with friendship and contention, with wit and warmth, with silliness and depravity.”

He finds among the people there an inexhaustible store of knowledge to draw from, both individually and collectively, whether in the stories they tell or in the jokes they crack or in the observations they make. “It amazes me how much people out here know,” he said. “I came to love the land and its river so much. I was drawn inexorably to this rural countryside. But the land was the least of it. The real attraction…is the people. As I got to know the people in town, it just really blew me away. I love the people. It’s a cast of characters.”