Omaha once reigned as a major live music hub where scores of legendary artists came to perform. Many resident musicians who got their chops here used Omaha as a springboard to forge fat careers on the coasts.

The local African-American music scene was particularly lively from the 1930s into the 1970s, with jumping venues and jam sessions galore.

Then, that halcyon time faded away.

Now, identical twins Ezra and Adeev Potash of Omaha, two fast-rising horn players with crazy close ties to such living-legend jazz greats as Wynton Marsalis and Jon Faddis, are intent on reviving that long dormant scene. Nominated for Best Jazz for the 2014 Omaha Entertainment and Arts Awards, they recently became co-artistic directors at the Love’s Jazz & Arts Center in Omaha. The twins, who turned 20 this fall, booked an all-star lineup of local artists at LJAC through 2013, headlining some dates themselves.

But it’s all a prelude for something grander. In collaboration with LJAC executive director Tim Clark the brothers are busy raising funds to underwrite a 2014-2015 lineup of jazz superstars. Many prospective guest artists are personal friends and colleagues of the twins in New York City, where the Westside High School graduates study music.

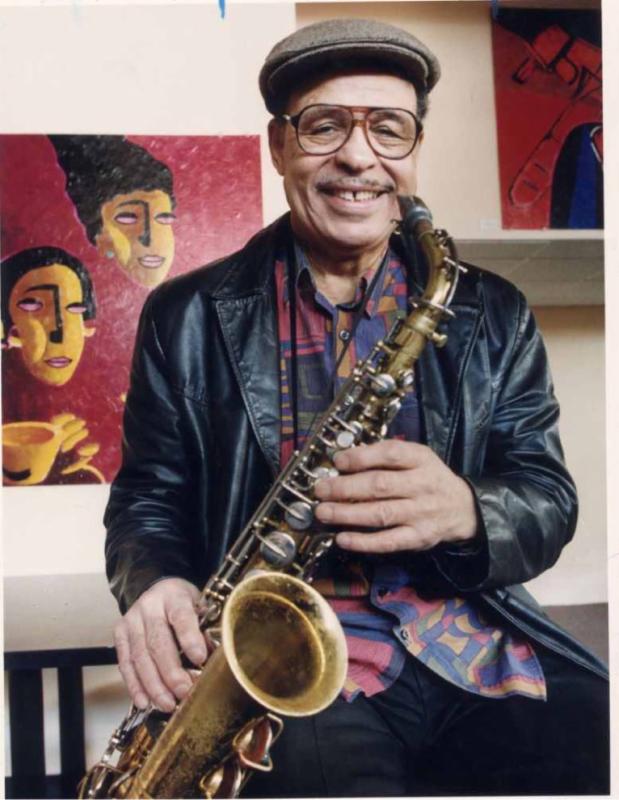

The brothers and Clark want nothing less than to create a world-class jazz club at the center, whose jazzman namesake, Omaha’s own Preston Love Sr., played with Count Basie and came of age in local nightspots like the Dreamland Ballroom. All the jazz giants played there or at Allen’s Showcase and other long-gone venues.

Clark says, “What’s so exciting about the twins is their enthusiasm and their sincere desire to preserve one of America’s original art forms, jazz, and to put Omaha back on the map as a national jazz hub. They’re very serious about their craft and making jazz a priority in Omaha. They bring a breath of fresh air.”

“We’re going to try to raise the money to do the season right,” says Ezra, who plays trombone, tuba, and sousaphone.“We’re meeting with donors to prove to them our passion and our vision to get what we need to become a sustainable jazz club. The thing we want people in Omaha to know is that we have the connections to bring in the biggest names in jazz. The only way we can make it happen is if Omaha gives us the resources to make it happen. We’re really close to getting it.

“Now is the time. Omaha’s really thriving as a city and becoming known for its arts. Jazz is a historical music with strong Midwest roots. North Omaha was a center of jazz, and it can be that again.”

Adeev, who plays trumpet, says, “We want to make Love’s Jazz an attraction for not only the Midwest but around the country. You won’t have to go to 18th and Vine in Kansas City or to the Dakota Club in Minneapolis to listen to great jazz.”

There are plans to upgrade the acoustics at LJAC to “make it a state-of-the-art performance space,” says Ezra.

As unlikely as it sounds that two suburban Jewish-Americans barely out of their teens should lead a jazz revival in the heart of Omaha’s black community, it’s just par for the course for the twins. At 15, their chutzpah translated into a private lesson with trumpet master Marsalis after sneaking backstage at the Lied Performing Arts Center in Lincoln following a gig by his Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra.

They appreciate what they have with Marsalis, who’s introduced them to other jazz icons, some of whom they’ve played with.

“Because of our relationship with Wynton we’re able to meet, hang out with, and learn from the best musicians in the world,” says Ezra. “We have a lot of awesome opportunities. We’re always eager to learn. And we like sharing with Omaha what we’re exposed to.”

Faddis confirms the brothers are “not shy” in approaching accomplished players like himself, Marsalis, and Jonathan Batiste for “pointers.” That networking has the brothers getting schooled by the best in the field.

“We’re living jazz history,” says Adeev, who studies under Faddis. “Wynton is the modern Coltrane. Jon Faddis is the disciple of Dizzy Gillespie. I feel honored to be part of the legacy they’ll leave me.”

Clark describes the twins as ambassadors, but the brothers also enjoy the limelight. In March, they performed at South by Southwest in Austin, Texas, where they led an impromptu New Orleans-style “second line” parade down Sixth Street that National Public Radio featured. A film crew following them for a proposed reality TV series was there and at the May Berkshire Hathaway Shareholders Meeting, where the brothers performed. They also did a recent talk at October’s TEDx Omaha event on the Creighton University campus.

Their talk and performance there focused on the intuitive communication and bond twins enjoy, an asset that is magnified on stage. “Twins in general like to finish each other’s sentences,” says Adeev, “and that kind of works the same in jazz.”

Visit

Visit