Archive

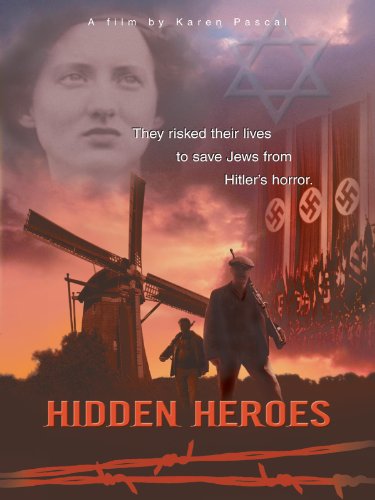

Bringing to light hidden heroes of the Holocaust

A dear friend of mine passed away recently, and as a way of paying homage to him and his legacy I am posting some stories I wrote about him and his mission. My late friend, Ben Nachman, dedicated a good part of his adult life to researching aspects of the Holocaust, which claimed most of his extended family in Europe. Ben became a self-taught historian who focused on collecting the testimonies of survivors and rescuers. It became such a big part of his life that he accumulate a vast library of materials and a large network of contacts from around the world. Ben’s mission was to help develop and disseminate Holocaust history for the purpose of educating the general public, especially youth, and he did this through a variety of means, including videotaped interviews he conducted, sponsoring the development of curriculum for schools, and hosting visiting scholars. He also led this journalist to many stories about Holocaust survivors, rescuers, and educational efforts. Because of Ben I have been privileged to tell something like two dozen Holocaust stories, some of which ended up winning recognition from my peers. I have met some remarkable individuals thanks to Ben. Several of the stories he led me to and that I ended up writing are posted on this blog site under the Holocaust and History categories.

The Hidden Heroes of the Holocaust Foundation that the following article discusses and that Ben founded was eventually absorbed into the Institute for Holocaust Education in Omaha.

Ben’s interests ranged far beyond the Holocaust and therefore his work to preserve history extended to many oral histories he collected from Jewish individuals from all walks of life and speaking to different aspects of Jewish culture. He got me involved in some of these non-Holocaust projects as well through the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society, including a documentary on the Brandeis family of Nebraska and their J.L. Brandeis & Sons department store empire (see my Brandeis story on this blog site) and an in-progress book on Jewish grocers. Ben’s passion for history and his generous spirit for sharing it will be missed. Rest in peace my friend, you were truly one of the righteous.

Bringing to light hidden heroes of the Holocaust

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

A new Omaha foundation is looking to build awareness about an often overlooked chapter of the Holocaust — the rescuers, that small, disparate and courageous band of deliverers whose compassionate actions saved thousands of Jews from genocide. A school-age curriculum crafted by the aptly named Hidden Heroes of the Holocaust Foundation, focusing on the rescue efforts of Swiss diplomat Carl Lutz, is receiving a trial run at Westside High School this spring.

The rescuers came from every station in life. They included civil servants, farmers, shop keepers, nurses, clergy. They hid refugees and exiles wherever they could, often moving their charges from place to place as sanctuaries became unsafe. The mostly Christian rescuers hid Jews in their homes or placed them in convents, monasteries, schools, hospitals or other institutions. As a means of protecting those in their safekeeping, custodians provided new, non-Jewish identities.

While not everyone in hiding survived, many did and behind each story of survival is an accompanying story of rescue. And while not every rescuer acted selflessly — some exacted payment in return for their silence — the heroes that did — and there are more than commonly thought — offer proof that even lone individuals can make a difference against overwhelming odds. These individuals’ noble actions, whether done unilaterally or in concert with organized elements, helped preserve one of Europe’s richest cultural legacies.

Hidden Heroes is the brainchild of Ben Nachman, a retired Omaha dentist who decades ago began an in-depth quest to try and understand the madness that killed 23 members of his Jewish family in the former Ukraine. While his despairing search turned up no satisfactory answers, it did introduce him to Holocaust scholars around the world and to scores of survivors, whose personal stories of survival and rescue he found inspiring.

He said he formed the non-profit foundation “to promote specific Holocaust education efforts and to promote the good deeds of hidden heroes. Most people are aware of only a handful of individuals, like Oscar Schindler or Raoul Wallenberg, who rescued Jews but there were many more who risked their lives to save others. Our mission is to bring to light the stories of these dynamic people and organizations and their little known activities. We hear enough about the bad things that went on. We want to tell the story of the good things and so our focus is on life rather than on death.”

Before he came to celebrate rescuers, Nachman spent years documenting the heroic and defiant stories of survivors. Among the accounts that stirred him most were those of former hidden children residing in Nebraska. Belgian native Dr. Fred Kader avoided deportation through the ultimate sacrifice of his mother, the brave efforts of lay and clergy Christian rescuers and a confluence of fortunate circumstances. Belgian native Dr. Tom Jaeger found refuge through the foresight of his mother and an elaborate network of civilian rescuers, all of whom risked their lives to aid him. Lou Leviticus, a native of Holland, eluded arrest on several occasions through a combination of his own wiles, an active Dutch underground movement and the assistance of Christian families. Nachman interviewed each man for the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Project (now known as the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education), a worldwide endeavor filmmaker Steven Spielberg started after completing Schindler’s List.

Nachman’s work introduced him to individuals who, despite immeasurable loss, continued embracing life. “I built-up a tremendous love affair with the survivors,” he said. “They’re a wonderful bunch of people. They’ve endured a great deal. They live with what happened every day of their lives, yet hatred is not there — and they’ve got every reason in the world to hate. They’re the most morally correct people I’ve ever found. They’re my heroes.”

As he heard story after story of how survivors owed their lives to the actions of total strangers, the more curious he became about the men and women who defied the Nazi death machine by harboring and transporting Jews, falsifying documents, bribing officials and doing whatever else was necessary to keep the wolves at bay. “I got very interested in the rescuers of Jews,” he said. “I was interested in knowing what made them do what they did. I think most of them did it because of their own personal convictions rather than out of some government mandate. For them, it was the only thing to do. They were very, very special people.”

One rescuer in particular captured his imagination — the late Carl Lutz, a Swiss diplomat credited with saving 62,000 Jews in Hungary while posted to Budapest as vice consul during the Second World War. At the center of an elaborate conspiracy of hearts, Lutz defied all the odds in devising, implementing and maintaining a mammoth rescue operation in cooperation with members of the Jewish underground, the Chalutzim, and select Swiss and Hungarian officials. He established protective papers and safe houses that helped thousands avoid deportation and almost certain death in the camps.

It is a story of how one seemingly insignificant statesman acted with uncommon courage in the face of enormous evil and personal risk and to do all this despite extreme pressure from Hungarian-German authorities and even his own superiors in Berne to stop. The more he has studied him, the more Nachman has come to admire Lutz, who died in 1975 — long before international acclaim caught up to him, including being named by Israel’s Yad Vashem as a Righteous Among the Nations.

What does he admire most about him? “Probably the fact he acted as a man of conviction rather than as a diplomat. He used the office of Swiss consul to shield a lot of what he was doing, but he did things he didn’t have to do. He was just an obstinate, stubborn man who felt right was the only way to go. Lutz was a very devout man and he felt he wanted to be on the side of God, not man.”

Nachman began searching for a way to make known to a wider audience little known acts of heroism like Lutz’s. In 2000 he and some friends, including former hidden child Lou Leviticus of Lincoln, formed Hidden Heroes. With Nachman as its president and guiding spirit, the foundation is a vehicle for researching, producing and distributing historically-based educational materials that reveal rarely told stories of rescue and resistance. It is the hope of Nachman and his fellow board members that the stories the foundation surfaces cast some light and hope on what is one of the darkest and bleakest chapters in human history.

One of the foundation’s first education projects, a curriculum program focusing on Lutz’s rescue efforts, is being piloted at Westside this spring. The curriculum, entitled Carl Lutz: Dangerous Diplomacy, includes a teacher’s guide, grade appropriate lesson plans, reading assignments, discussion activities and classroom resources, including extensive links to selected Holocaust web sites.

The curriculum was written by Christina Micek, a Holocaust studies graduate student and a third grade teacher at Springlake Elementary School in Omaha. With programs designed for the sixth and eighth grades and another for high school, Micek based the materials on the definitive book about Lutz and his heroic work in Hungary, Dangerous Diplomacy: The Story of Carl Lutz, Rescuer of 62,000 Hungarian Jews (2000, Eerdmans Publishing Co.) by noted Swiss historian Theo Tschuy, a consultant with the foundation. Micek developed the curriculum with the input of Tschuy, who made a foundation-sponsored speaking tour across Nebraska last winter.

Foundation secretary/treasurer Ellen Wright said, “The Holocaust was obviously one of the biggest travesties in history and we feel it is valuable to tell the stories of individuals like Carl Lutz who rose to the occasion and acted righteously.” Wright, who away from the foundation is deputy director of the Watanabe Charitable Trust, said the foundation wants the story of Lutz and other rescuers to serve as models for youths about how individuals can stand up to injustice and intolerance.

“Our youths’ heroes today are athletes and entertainers, which is an interesting commentary on our times. What we want to do is add to that plate of heroes by taking a look at an individual like Carl Lutz and seeing that while his actions were extraordinary he was just like you and I. The difference is, he saw a need and became not only impassioned but obsessed by it. When you consider the 62,000 lives he saved you realize he made it possible for generation after generation of descendants to live and do wonderful things around the world. It’s a remarkable feat and that’s what we want to impart.”

Wright added the foundation seeks to eventually make the Lutz curriculum available, at no cost, to schools in Nebraska, across the nation and around the world. In addition to the current curriculum package, she said, plans call for making an interactive CD-ROM as well as Tschuy’s book available to schools.

The idea of Hidden Heroes’ education mission, members say, is to go beyond facts and figures and to instead spark dialogue about what lies at the heart of bigotry and discrimination and to identify what people can do to combat hate. Curriculum author Christina Micek said she wants students using the materials “to get a personal connection to history” and has therefore created lesson plans that allow for discussion and inquiry. She said when dealing with the Holocaust, students should be encouraged to ask questions, search out answers and apply the lessons of the past to their own lives.

“I don’t see teaching history and social studies as something where a teacher is lecturing and the kids are writing down dates,” she said. “I really want students to feel they’re historians and to feel like they know Carl Lutz by the end of it. I want them to take a personal interest in the subject and to analyze the events and to be able to identify some of the moral issues of the Holocaust and to discuss them in an educated manner.”

The sense of discovery and empathy Micek wants the curriculum to inspire in youths is something quite personal for her. Recently, Micek, a Catholic since birth, discovered she is actually part Jewish. Her mother’s German emigre family, the Feldmans, were practicing Catholics as far back as anyone recalled. But the maternal branches of Micek’s family tree were shaken when relatives searching for records of descendants near Frankfurt, Germany came up empty and were instead directed to a local synagogue, where, to their surprise, they found marriage records of Josef Feldman, her maternal great-great-great grandfather.

Like many Jews in Europe hounded by pogroms, the Feldman family hid their Jewish identity and adopted Catholic traditions around the time they emigrated to America in the late 19th century. Some family members remained behind and perished in the Holocaust. This revelation of a lost heritage has been a life-transforming experience for Micek and one that informs her work with the foundation.

“I felt a great personal loss. My family was kind of cheated out of their culture and their religion,” she said. “And so, for me as educator, I feel it’s important that people realize what hate and not understanding other peoples can do to families and cultures. I was attracted to the Hidden Heroes mission because it shows children that, yes, the Holocaust was a terrible tragedy but that were good people who tried to help. It shows something more than the negative side.”

Micek field tested a revised version of the curriculum with her third grade class and found the compelling subject matter had a profound effect on her students.

“My classroom is 80 percent English-As-A-Second-Language children. Most are new immigrants from Mexico, and so they have a first-hand experience of what it is like to be discriminated against. They could relate to the prejudice Jews endured. It provided my class with a wonderful discussion forum to get into the issues raised by the Holocaust. I thought the kinds of questions my kids came up with were very adult: Why do people hate? How can we keep people from hating other people? It turned out to be really in-depth.

“And my kids have kind of become activists around the school based on this lesson. They’re more caring and they try to help other students when they hear negative messages in the hall. It’s gone a lot further than I ever thought it would.”

She anticipates older students using the lesson plan will also be spurred to look beyond the story of Lutz to examine what they can do when confronted with hate. “I hope that, like my third graders did, they take it beyond the classroom and incorporate it into their own lives To understand what prejudice and hate can do and maybe in their own little corner of the world try and make sure that doesn’t happen again.”

According to Tom Carman, head of the department of social studies in the Westside Community Schools, the Lutz curriculum is, for many reasons, an attractive addition to the district’s standard Holocaust studies.

“The material allows us to look beyond Oscar Schindler and Raoul Wallenberg, whose rescue efforts some people view as an aberration, in showing there were a number of people, granted not enough, who did some positive things at that time. It does take that rather depressing topic and give it some ray of hope. I was always looking for something that added some degree of positive humanity to it.

“And while I thought I was fairly familiar with the subject of the Holocaust, I had never heard of Carl Lutz, which surprised me. That was probably the main draw in our incorporating this curriculum. That and the fact it provides a framework for looking at the moral dilemmas posed by the Holocaust.

“Everybody asks, How could that happen? In the final analysis it happened because people allowed it to happen. It prods us to ask whether the pat answers given by perpetrators and witnesses — ‘I was only following orders’ or ‘I didn’t know’ — are acceptable answers because in figures like Carl Lutz we find there were people who behaved differently. Lutz and others said, This is wrong, and did something about it, unlike most people who took a much safer route and either feigned ignorance or looked the other way. It gives examples of people who acted correctly and that teaches there are options out there.”

Bill Hayes, a Westside social studies instructor applying the curriculum in his class, said, “I think it gives a message to kids that you don’t have to just stand by — there is something you can do. There may be some risk, but there is something you can do.”

Carman said the material provided by the Hidden Heroes Foundation is “done very well” and is “really complete.” He added it is written in such a way as to make it readily “adaptable” and “usable” within existing curriculum. District 66 superintendent Ken Bird said it’s rare for a non-profit to offer “a value-added” educational program that “so nicely augments our curriculum as this one does.”

Lutz became the subject of Hidden Heroes’ first major education project due to Nachman’s own extensive research and contacts.

“In my reading I ran across Lutz,” Nachman said, “and in writing, searching and chasing around the world I found his step-daughter, Agnes Hirschi, a writer in Bern, Switzerland. We started corresponding regularly. She introduced me to the man who is the biographer of Lutz — the Rev. Theo Tschuy — a Methodist minister living outside Geneva. He has done tremendous research into the rescuers and he particularly knows the story of Lutz. He and I have become about as close as two people can be.”

Nachman was instrumental in finding an American publisher (Eerdmans) for Tschuy’s book on Lutz. In addition to his work with the foundation, Nachman is a contributor and catalyst for other Holocaust projects. In conjunction with New Destiny Films, a production company with offices in Omaha and Sarasota, Fla., Nachman did research for two documentaries in development.

One film, which Nebraska Public Television may co-produce, profiles survivors who resettled in Nebraska and forged successful lives here, including Drs. Kader and Jaeger, a pediatric neurologist and psychiatrist, respectively, and Lou Leviticus, a retired UNL agricultural engineering professor. The other film, which American Public Television is to distribute, focuses on the rescue that Lutz engineered. The latter film, Carl Lutz: Dangerous Diplomacy, is intended as the first in a series (Hidden Heroes of the Holocaust) on rescuers.

Nachman and New Destiny’s Mike Moehring of Omaha have traveled to Europe to conduct interviews and pore over archives. The Swiss Consulate in Chicago has taken an interest in the Lutz film, providing financial (defraying airfare expenses) and logistical (cutting red-tape) support for research abroad. Swiss Consul General Eduard Jaun, who is excited about the project, said, “This will be the first comprehensive film about Lutz.”

Hidden Heroes is now working on creating new education programs featuring other rescuers. Micek is gathering data for a curriculum focusing on the late Portuguese diplomat Aristides de Sousa Mendes, who while stationed in France signed thousands of visas that spared the lives of their recipients, including many Jews.

Nachman serves on an international committee working to bring worldwide recognition to the humanitarian work of Mendes. Other subjects the foundation is researching are: Father Bruno Reynders, a Benedictine monk who found refuge for more than 200 Jewish children in Belgium; the individuals and organizations behind Belgium’s extensive rescue network, which successfully hid 4,500 children; and the rescue of children on the French and Swiss borders.

Wright said when she approaches potential donors about supporting the foundation she sometimes encounters cynical attitudes along the lines of — “I don’t want to hear anymore about the Holocaust” — which she views as an opportunity to explain what sets Hidden Heroes apart from other Holocaust education initiatives.

“While it’s true there’s a tremendous amount of information out there about the Holocaust,” she said, “what we’re trying to do is take a different approach. Through the stories of survivors and rescuers we want to talk about life. About how survivors did more than just survive — they went on to thrive, raise families and accomplish remarkable things. About how rescuers risked everything to save lives. We want to tell these stories in order to educate young people around the world. It is our hope that behaviors and attitudes can be changed, if even one person at a time, so that something like this never happens again.”

Among others, the foundation’s message of hope is being bought into by funding sources. The foundation recently gained the support of the National Anti-Defamation League, which has promised a major grant to fund its work. Hidden Heroes is close to securing a matching grant from a local donor. The foundation anticipates working cooperatively with the National Hidden Children’s Foundation, which is housed within the National ADL headquarters in New York. More funding is being sought to underwrite foundation research jaunts in Europe.

Because stories of rescue have as their counterpart stories of survival, Hidden Heroes is also involved in raising awareness about the survival experience. In a series of events ranging from receptions to lectures, the foundation presents occasional forums at which former hidden children speak about survival in terms of the trauma it exacts, the defiance it represents and the ultimate triumph over evil it achieves.

For example, the foundation sponsored a November visit by Belgian psychologist and author Marcel Frydman, a former hidden child who spoke about the lifelong ramifications of the hidden child experience, which he describes in his 1999 French-language book, The Trauma of the Hidden Child: Short and Long Term Repercussions. Nachman, who enjoys the role of facilitator, brought Frydman together with Drs. Kader and Jaeger, two countrymen who share his hidden child legacy, for an emotional meeting last fall.

Foundation members say each is participating in the work of the Hidden Heroes organization for his or her own reasons. For Ellen Wright, “it is the right thing to do.” For Nachman, it is a source of fulfillment unlike any other. “There’s nothing I’ve ever done that’s had more meaning and made more of an impact on me,” he said. He noted that as the aging population of survivors and rescuers dwindles each year, there is real urgency to recording the stories of survivors and rescuers before the participants in these stories are all gone.

With reports of anti-Semitism on the rise in Europe and elsewhere in the wake of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian crisis, foundation members say there is even added urgency to telling stories of resilience, resolve and rescue during the Holocaust because these accounts demonstrate how, even in the midst of overwhelming evil, good can prevail.

Related Articles

- ‘American Schindler’ helped 4,000 Jews escape the Nazis (telegraph.co.uk)

- Righteous Gentiles honored in Warsaw (jta.org)

- Leo Adam Biga’s Survivor-Rescuer Stories Featured on Institute for Holocaust Education Website (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

The Pawnshop Beat

The first and last time I walked into a pawnshop was when I did this story. On second thought, I may have been in a pawnshop or two when I was a kid, accompanying my dad on trips to find some bargain items, maybe a guitar for my older brother Greg or something like that. But otherwise my only take on pawnshops is derived from the movies and from books and articles. My research for this story didn’t necessarily overturn any assumptions I had about these places, other than the fact that they can be extremely large and profitable operations with vast warehouses full of merchandise that rival that of discount department stores. This story for the Omaha Weekly may not dispel any of your ideas about pawnshops either, but after doing the piece I did have a better appreciation for why they are so ubiquitous — simply put, they fill a need or demand that all the banks and loan offices cannot. I try in the piece to present the good, the bad, and the gray about these marketplace and moneychanging emporiums, where commerce of all kinds is transacted.

The Pawnshop Beat

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the Omaha Weekly

In what is a combination bazaar, everything-under-one-roof discount store and cash-on-the-barrelhead lending operation, the neighborhood pawnshop offers something for everyone. This marketplace for buying, trading and borrowing is a center of commerce where the down-and-out rub shoulders with the upwardly mobile in a common search for a good deal. From cars and boats to lawn mowers and weed whackers to guns and games to stereos and VCRs to rings and necklaces, pawnshops, which have been called the world’s greatest garage sale, deal in it all.

Because they are also historically dumping grounds for stolen goods, every single transaction is reviewed by law enforcement authorities, who, based on hunches and crime reports, look for red flags in the merchandise moved there and in the profiles of customers doing business there.

You generally don’t seek a loan at a pawnshop unless some life event — usually a bad one — has brought you to one. Maybe you’re out of work or in between pay checks. Maybe your credit cards and checking accounts are tapped out. Maybe your car’s on the blink. Maybe medical bills are due. Perhaps you’ve lost more than you can afford at Harvey’s.

Whatever your story, and there’s a million of them, you find yourself strapped for cash and unwilling or unable to borrow from family, friends, traditional lending institutions and more non-traditional sources like loan sharks. So, you grab whatever possessions you can lay your hands on and hock them for some greenbacks to help you get out of a bind. Often described as the bank of last resort, pawnshops are, for some, a stop-gap money source for when true crises arise and for others simply a way of life whose no-questions-asked ready-cash supply helps folks get by when other avenues are closed.

Jack Belmont, who’s been in the trade since growing up in the Great Depression, explained the basic appeal for people of doing business at a pawnshop as opposed, for example, to a bank. “It’s a quick deal,” he said from behind the main counter at Mid-City Jewelry & Loan, where he is a partner with owner Don Hoberman. “You walk in when you feel you’ve got something to pawn and you make the loan. You can be in and out of here inside of five minutes. You can come back anytime you want. Nobody knows your business. You don’t have to fill out a balance sheet or anything else like that. It’s very convenient, very quick.”

For those engaged in that left-handed form of human endeavor known as crime, pawnshops are convenient places to unload hot property and turn a fast buck, although the chances of avoiding detection are slim. Indeed, if it wasn’t for pawnshops, police officials say, many stolen goods would not be recovered. When stolen property in a pawnshop is detected and its rightful owner contacted to identify and retrieve it, the owner is invariably upset to find out he or she must pay to get the stuff back. This redemption charge, which is usually a fraction of the item’s cost, may seem somewhat heartless but is completely legal.

Clerking at a pawnshop is a little like being a bartender or a barber. Just about everyone who sidles up to the counter has a hard luck story to tell. Saul Kaiman, the introspective bearded owner of Sol’s Jewelry & Loan, which has four locations in the Omaha metro area, said, “When I first started working in pawnshops in the ‘50s I heard so many tales of people needing $50 to get to a funeral that I didn’t think there was anybody left alive in the United States. I was naive. I believed everything they said at first. After awhile, you know some of them are just stories and you just try to keep a straight face,” he said.

Christy, a pretty clerk in Sol’s downtown store at 514 N. 16th Street, said she has heard it all. “We get a lot of people who need help with their bills or need to get their car fixed or need to get their house repaired. Once in a while we get pawners who’ve never pawned before. They have some family emergency and they actually cry they’re so desperate.”

For a gun lover, getting a loan on a prized weapon can be as torturous as giving up a first-born son. At least that’s how painful it appeared for a man wearing a jacket and hat emblazoned with NRA slogans who came to Sol’s to pawn his Mossbach 810 rifle: “My car broke down and I needed to get it working again and this is all I had to get me what I need to get by,” he said, referring to the gun. “It’s a very fine gun. I just want to get it back.” He said it’s the first time he’s had to give up his gun. As with any pawn transaction in Nebraska, he has four months to redeem his weapon, with interest accruing from the date of the loan.

According to Tedi, a pert and petite clerk at Sol’s downtown store, “There’s a lot of people that come in here that feel bad about the circumstances they’re in. I tell them that it’s happened to everybody. That bad stuff happens and we all need money to get out of jams, and that’s what we’re here for. I try not to make them feel embarrassed about. I try to make them feel like it’s OK.”

Don Hoberman, the sardonic owner of Mid-City Jewelry and Loan at 515 So. 15th Street, explained there is an implied Don’t Ask-Don’t Tell pact in place at pawnshops to protect people’s privacy. “You don’t ask them why” they need the cash, he said. “It’s immaterial anyway. It’s their money. They don’t have to tell me why. Some people just walk in, borrow money and walk out. But some people feel they have to, so you listen,” he said.

A pretty but sad-eyed wife and mother of two recently entered Sol’s looking distraught as she used one hand to push an electric snowblower ahead of her and the other hand to cart a camera case. “I missed a payday at work and I needed a little help to pay some bills today. That way I won’t get behind and I know I still have time to come back down and get my stuff out. I’ve been dealing with Sol’s for 10 years and they don’t ask any questions — they just help if they can.” With her $275 loan in hand, she left with a smile.

Customers don’t always leave happy, however. In assessing the fair market value of a pawned item, for example, there is bound to be some difference of opinion. Christy at Sol’s said, “We get quite a few irate customers. They get mad because we don’t give them what they want or they think we’re gypping them. We’re not. We’re being fair with the game. When they sign the contract they know what they’re signing.” Tedi at Sol’s added, “No matter how hard we try to explain the loan process, you get some people that…don’t seem to understand that the item they pawned a year ago and never paid on is no longer here, because if you don’t come back for it or pay on it after four months we can sell it. A lot of times it was a sentimental thing, and they’re angry about it. Like it’s all our fault.”

Then there are the regulars. Take Judy Johnson, for example. She often pawns jewelry at Mid-City to help tide her over when things are tight. “Right now I’m painting my house, and I need extra money” for supplies, she said one morning at the shop. She still has several jewelry pieces in hock.

“I miss them a lot,” she said. She is one of several loyal customers to follow Belmont to Mid-City from the shop he and his late brother ran, and that their late father started, Crosstown Loan, which was located on N. 24th Street until it burned down in the 1969 riot, and which later moved to 16th Street. At Sol’s, the regulars include a mother-daughter combo who say they’re such frequent customers that “they should put a revolving door in for us.” Kaiman said many elderly customers, including a man who pawned his Colt. 38 revolver over and over again, make a habit of pawning as much for the social interaction as for the money.

Hoberman and partner Jack Belmont own a combined 90-plus years in the business. For them, the pawnshop is a kind of social laboratory and money changer in one where the disparate mix of human kind meet to haggle and strike a deal.

So, what’s the oddest thing someone has tried pawning? Hoberman recalled the man who came in once and asked, ‘Do you take anything?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He goes, ‘How about an eyeball?’ I said, ‘C’mon quit kidding.’ So, he popped it out and put in on the counter. And I said, ‘Make it wink.’ He couldn’t do it, so I had him put it back.” Then there was the World War II veteran who made a habit of pawning his prosthetic leg, which he never picked up — Veterans Administration Hospital workers did. Hoberman draws the line at living creatures. “We always figure if you gotta feed it or clean it, you don’t want it, so we don’t take it.”

You never know who will show up at a pawnshop, either. Back in the early 1980s then-Governor Bob Kerrey, who became a good friend of the store’s through his predecessor, former governor and senator Jim Exon, whom Hoberman knew from Exon’s days in the furniture business, stopped by to ask, “What do you give somebody who’s a movie star?” Kerrey was referring to his then girl-friend, screen actress Debra Winger. “I told him one of the fashionable things was pearls, and so we acquired 30-inch strand of pearls and he gave them to her for a present. Two day afterwards her picture was taken at some event and she had them on. He sent me the picture. He doesn’t have the girl anymore, but she still has the pearls.”

If all his years in the trade have taught him anything, Hoberman said, it is that people “from all walks of life” — from high rollers to penniless tramps — frequent pawnshops and the thing is you can’t always tell who’s who.

“You can’t qualify who comes through the front door and decide what they’re going to pawn or what they might be able to buy. It’s a lesson I learned a long time ago. I once had somebody pawn a $5 watch and then he wanted to look at a $1,000 ring. And I thought, Well, why should I show him this ring when he’s having trouble getting $5 together?

“But I soon learned you don’t look at it that way. The guy came back and he said, ‘Thank you for loaning me on the watch,” and he walked over to the jewelry case and plunked down cash to buy the ring. You see, you just don’t decide what they can and can’t do by what they look like.” In other words, assuming someone is broke just because he or she needs fast cash is a no-no. “It isn’t always because you’re broke,” Hoberman said, “it’s because you’re short.”

Or, as a distinguished looking black man said one morning at Sol’s, where he was redeeming a bracelet he originally bought there, “I get paid every two weeks and with utilities the way they are and everything in general going up, I get little shortfalls between paychecks, and so pawning’s a matter of just being able to make it and keep everything current with bills, groceries, bus fare and things like that.” He added, “You know, sometimes you don’t want to do it, but it just comes in handy as a safety net. It’s just another tool in helping you make it through.”

Besides, the kind of fast turnover loans made by pawnshops just aren’t available elsewhere. “Say you have a ring you bought at a retail store for $1,000, and now you need $200 for something. You can’t take it (the ring) to the bank because they don’t loan on products like that,” Hoberman said. “Even if the ring was worth $40,000, the bank still won’t loan on it. I have people come in with $10,000 in their pocket. They need another $4,000 to buy something and they’ve got to do it NOW. They come with something we can loan them $4,000 on and they’re out the door and they’re back.”

Hoberman believes most people find themselves financially short due to their own actions or decisions. He points to the casinos across the river as a major reason why some people end up on the margins or fringes. He said where items were once being redeemed at a nearly 80 percent rate, they are now redeemed at only 62 percent.

“The redemption percentage has dropped because I think people never recover from their gambling losses,” he said. “I have one gentleman who pawns his car here. He stops in on his way to the casino. We loan him money on the car, then we drive him over and drop him off at the boat, and we put his car into storage. On occasion…he hits and he’s back to get his car the same day.” Other times, the car sits in storage for days or weeks before he can afford to retrieve it.

Kaiman, of Sol’s, agrees that gambling addiction, along with drugs, accounts for the lower redemption rates being seen in pawnshops.

“My personal opinion is that a lot of people get financially hurt over at the casinos. You know they pawn their diamond ring or something with hopes of winning over there. They don’t win and they don’t have enough to get it back. The casinos have probably changed the way we operate more than anything than I can remember. It used to be a cyclical thing. From October to February more people were buying things and picking up things, and the rest of the months were more input — with people bringing things in more than picking up. But because the casinos are 12-months a year, 24-hours a day, that’s changed a lot. We get less pickups and just more coming in.”

It’s meant an ever expanding inventory at Sol’s, which must increasingly try to resell unredeemed items, often at close to cost just to reduce backlogs.

Detective Mike Salzbrenner of the Omaha Police Department’s Burglary/Pawn Unit works the local pawnshop beat. He, and his colleagues, follow a daily routine that finds them making the rounds at the local shops, where they scour through identification cards completed on every transaction. Each pawn card includes the customer’s name, address, telephone number, height weight and fingerprint as well as a summary of the transaction and a description of the items dealt. Rifling through the cards, the well-tanned and blue-suited Salzbrenner looks for anything that appears fishy.

“See, this one bothers me,” he tells a visitor one morning at Sol’s. “Here’s a young lady who just turned 18, which is the legal minimum age to pawn, and she brought in a $250-$300 tennis bracelet. Because of her age, that makes me think the bracelet’s her mother’s or somebody’s. That’s one I’ll call and speak with the mother about. I swear, half the time the mother will come back and say, ‘It’s not in my jewelry box.’ And I’ll tell her, ‘I’m sorry ma’am, but she just pawned it and you better find out why.” Often, Salzbrenner said, it’s to support a drug habit or to cover debts.

Although he has no hard evidence to prove it, Salzbrenner is sure that pawning — of stolen goods or not — has increased since the arrival of the casinos. Gambling debts, he said, force otherwise law-abiding citizens to take desperate measures. “A typical case I’m working on is somebody with a gambling problem. They get addicted to gambling and, of course, they run out of money. They turn around and start stealing from their employer. Well, a lot of these people are not common thieves. They wouldn’t know a fence out on the street. But they do know pawnshops, where they go and claim items as their own and get $20 for a watch or whatever. They go across the river, lose their money and they want to gamble again.” So, they steal again. And the cycle goes on.

The job, Salzbrenner acknowledges, calls for much interpretation. “We’re the judgment call beat. We’re looking for anything suspicious. Suspicious to us,” he said, includes youths bringing in merchandise not appropriate to their age or anyone selling things, especially new items, for a fraction of their value or customers not knowing much about the goods they represent as their own.

He said in following up on questionable deals, citizens often grow defensive about what they consider a hassle and an intrusion into their private lives. “We get a lot of accusations thrown at us. A lot of times they say, ‘If there’s no victim, then why are you bothering me?’ Well, I tell them, we’re trying to find out if there is one.”

When his nose tells him something stinks, he said, he’ll track the customer’s pawn and criminal records on the police computer, he’ll place phone calls and he’ll make other inquiries until he’s exhausted all lines of investigation. “Somebody’s going to have to satisfy me someplace,” he said. Until he has an answer, he can put a hold on any item, and it cannot be touched again until he releases it.

Salzbrenner’s superior, Sgt. Mary Bruner, said smart thieves either avoid pawnshops altogether — preferring to exchange their ill-gotten goods on the street — or else enlist accomplices, including residents of shelters, to pawn the booty, which makes suspect identification and apprehension more difficult. While only a fraction of all stolen goods is ever recovered, Bruner said the OPD’s Burglary/Pawn Unit cleared a record $752,000 in recovered stolen property last year. Contributing to that total, she said, was the unit cracking a couple large jewelry theft rings.

According to Hoberman, the way business is conducted at pawnshops these days — with paperwork filled out in triplicate and unredeemed items stockpiled in warehouses brimming with goods from floor to ceiling — some of the joy has gone out of the work. He said there isn’t quite the trust and conviviality there once was.

“People have changed. It used to be word was bond. Way back, a guy would come in with a two-cent lead pencil and you’d loan him $10 on it. Now, that may sound strange, but his word was bond. That’s all he had was his word. He would come back and get that lead pencil. Now, he knew he could go out and buy another pencil for two cents. He didn’t have to come back and pay that $10, but he would. It used to be a little more casual and a lot more fun. It’s still fun, but it’s more business. Back in the old days you could kind of fly by the seat of your pants. I used to keep a whistle under the counter and when it would get really crazy in here, I’d blow the whistle and say, ‘Wait a minute, let’s start this whole day over.’”

Related Articles

- Pawnshops finding unlikely customers (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Pawnshop oddities reflect Gulf struggles (cnn.com)

- Before the Wall Street Crisis, There Was “Poverty, Inc.” (politics.usnews.com)

- Pawning the family heirlooms (money.cnn.com)

- Pawnshops Becoming More Respectable (volokh.com)

- Groupon Founders Reinvent The Pawnshop (fastcompany.com)

- Pawnshops Flourish in Hard Times, Drawing Scrutiny (time.com)

A force of nature named Evie: Still a maverick social justice advocate at 100

Spend even a little while with Evie Zysman, as I did, and she will leave an impression on you with her intelligence and passion and commitment. I wrote this story for the New Horizons, a publication of the Eastern Nebraska Office on Aging. We profile dynamic seniors in its pages, and if there’s ever been anyone to overturn outmoded ideas of older individuals being out of touch or all used up, Evie is the one. She is more vital than most people half or a third her age. I believe you will be as struck by her and her story as I was, and as I continue to be.

A force of nature named Evie:

Still a maverick social justice advocate at 100

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

When 100-year-old maverick social activist, children’s advocate and force of nature Evelyn “Evie” Adler Zysman recalls her early years as a social worker back East, she remembers, “as if it were yesterday,” coming upon a foster care nightmare.

It was the 1930s, and the former Evie Adler was pursuing her graduate degree from Columbia University’s New York School of Social Work. As part of her training, Zysman, a Jew, handled Jewish family cases.

“I went to a very nice little home in Queens,” she said from her art-filled Dundee neighborhood residence. “A woman came to the door with a 6-year-old boy. She said, ‘Would you like to see his room?’ and I said, ‘I’d love to.’ We go in, and it’s a nice little room with no bed. Then the woman excuses herself for a minute, and the kid says to me, ‘Would you like to see where I sleep?’ I said, ‘Sure, honey.’ He took me to the head of the basement stairs. There was no light. We walked down in the dark and over in a corner was an old cot. He said, ‘This is where I sleep.’ Then he held out his hand and says, ‘A bee could sting me, and I wouldn’t cry.’

“I knew right then no child should be born into a living hell. We got him out of that house very fast and got her off the list of foster mothers. That was one of the experiences that said to me: Kids are important, their lives are important, they need our help.”

Evie Zysman

Imbued with an undying zeal to make a difference in people’s lives, especially children’s lives, Evie threw herself into her work. Even now, at an age when most of her contemporaries are dead or retired, she remains committed to doing good works and supporting good causes.

Consistent with her belief that children need protection, she spent much of her first 50 years as a licensed social worker, making the rounds among welfare, foster care and single-parent families. True to her conviction that all laborers deserve a decent wage and safe work spaces, she fought for workers’ rights as an organized union leader. Acting on her belief in early childhood education, she helped start a project that opened day care centers in low income areas long before Head Start got off the ground; and she co-founded, with her late husband, Jack Zysman, Playtime Equipment Co., which sold quality early childhood education supplies.

Evie developed her keen social consciousness during one of the greatest eras of need in this country — the Great Depression. The youngest of eight children born to Jacob and Lizzie Adler, she grew up in a caring family that encouraged her to heed her own mind and go her own way but to always have an open heart.

“Mama raised seven daughters as different as night and day and as close as you could possibly get,” she said. “Mama said to us, ‘Each of you is pretty good, but together you are much better. Remember girls: Shoulder to shoulder.’ That was our slogan. And then, to each one of us she would say, ‘Don’t look to your sister — be yourself.’ It was taken for granted each one of us would be ourselves and do something. We loved each other and accepted the fact each one of us had our own lives to live. That was great.”

Even though her European immigrant parents had limited formal education, they encouraged their offspring to appreciate the finer things, including music and reading.

“Papa was a scholar in the Talmud and the Torah. People would come and consult him. My mother couldn’t read or write English but she had a profound respect for education. She would put us girls on the streetcar to go to the library. How can you live without books? Our home was filled with music, too. My sister Bessie played the piano and played it very well. My sister Marie played the violin, something she did professionally at the Loyal Hotel. My sister Mamie sang. We would always be having these concerts in our house and my father would run around opening the windows so the neighbors could also enjoy.”

Then there was the example set by her parents. Jacob brought home crates filled with produce from the wholesale fruit and vegetable stand he ran in the Old Market and often shared the bounty with neighbors. One wintry day Lizzie was about to fetch Evie’s older siblings from school, lest they be lost in a mounting snowstorm, when, according to Evie, the family’s black maid intervened, saying, “You’re not going — you’re staying right here. I’ll bring the children.’ Mama said, ‘You can go, but my coat around you,’ and draped her coat over her. You see, we cared about things. We grew up in a home in which it was taken for granted you had a responsibility for the world around you. There was no question about it.”

Along with the avowed obligation she felt to make the world a better place, came a profound sense of citizenship. She proudly recalls the first time she was old enough to exercise her voting right.

“I will always remember walking into that booth and writing on the ballot and feeling like I am making a difference. If only kids today could have that feeling when it comes to voting,” said Evie, a lifelong Democrat who was an ardent supporter of FDR and his New Deal. When it comes to politics, she’s more than a bystander — she actively campaigns for candidates. She’ll be happy with either Obama or Clinton in the White House.

When it came time to choose a career path, young Evie simply assumed it would be in an arena helping people.

“I was supposed to, somehow,” is how she sums it up all these years later. “I believed, and I still believe, that to take responsibility as a citizen, you must give. You must be active.”

For her, it was inconceivable one would not be socially or politically active in an era filled with defining human events — from millions losing their savings and jobs in the wake of the stock market crash to World War I veterans marching in the streets for relief to unions agitating for workers’ rights to a resurgence of Ku Klux Klan terror to America’s growing isolationism to the stirrings of Fascism at home and abroad. All of this, she said, “got me interested in politics and in keeping my eyes open to what was going on around me. It was a very telling time.”

Unless you were there, it’s difficult to grasp just how devastating the Depression was to countless people’s pocketbooks and psyches.

“It’s so hard for you younger generations to understand” she told a young visitor to her house. “You have never lived in a time of need in this country.” Unfortunately, she added, the disparity “between rich and poor” in America only seems to widen as the years go by.

With her feisty I-want-to-change-the-world spirit, Evie, an Omaha Central High School graduate, would not be deterred from furthering her formal education and, despite meager finances, became the first member of her family to attend college. Because her family could not afford to send her there, she found other means of support via scholarships from the League of Women Voters and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where the Phi Betta Kappa earned her bachelor’s degree.

“I knew that for me to go to college, I had to find a way to go. I had to find work, I had to find scholarships. Nothing came easy economically.”

To help pay her own way, she held a job in the stocking department at Gold’s Department store in downtown Lincoln. An incident she overhead there brought into sharp relief for her the classism that divides America. “

One day, a woman with a little poodle under her arm came over to a water fountain in the back of the store and let her dog drink from it. Well, the floorwalker came running over and said, ‘Madam, that fountain is for people,’ and the woman said, ‘I’m so sorry, I thought it was for the employees.’ That’s an absolutely true story and it tells you where my politics come from and why I care about the world around me and I want to do something about it.”

Her undergraduate studies focused on economics. “I was concerned I should understand how to make a living,” she said. “That was important.” Her understanding of hard times was not just of the at-arms-length, ivory-tower variety. She got a taste of what it was like to struggle when, while still an undergrad, she was befriended by the Lincoln YWCA’s then-director who arranged for Evie to participate in internships that offered a glimpse into how “the other half lived.” Evie worked in blue collar jobs marked by hot, dark, close work spaces.

“She thought it was important for me to have these kind of experiences and so she got me to go do these projects. One, when I was a sophomore, took me in the summer to Chicago, where I worked as a folder in a laundry and lived in a working girls’ rooming house. There was no air conditioning in that factory. And then, between my junior and senior years, I went to New York City, where I worked in a garment factory. I was supposed to be the ‘do-it’ girl — get somebody coffee if they wanted it or give them thread if they needed it, and so forth.

“The workers in our factory were making some rich woman a beautiful dress. They asked me to get a certain thread. And being already socially conscious, I thought, ‘I’ll fix her,’ and I gave them the wrong thread,” a laughing Evie recalled, still delighted at the thought of tweaking the nose of that unknown social maven.

Upon graduating with honors from UNL she set her sights on a master’s degree. First, however, she confronted misogyny and bigotry in the figure of the economics department chairman.

“He said to me, ‘Well, Evelyn, you’re entitled to a graduate fellowship at Berkeley but, you know, you’re a woman and you are a Jew, so what would you possibly do with your graduate degree when you complete it?’ Well, today, you’d sue him if he ever dared say that.”

Instead of letting discrimination stop her, the indomitable Evie carried-on and searched for a fellowship from another source. She found it, too, from the Jewish School of Social Work in New York.

“It was a lot of money, so I took it,” she said. “I had my ethic courses with the Jewish School and my technical courses with Columbia,” where she completed her master’s in 1932.

As her thesis subject she chose the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, one of whose New York factories she worked in. There was a strike on at the time and she interviewed scores of unemployed union members who told her just how difficult it was feeding a family on the dole and how agonizing it was waking-up each morning only to wonder — How are we going to get by? and When am I ever going to work again?

As a social worker she saw many disturbing things — from bad working conditions to child endangerment cases to families struggling to survive on scarce resources. She witnessed enough misery, she said, “that I became free choice long before there was such a phrase.”

Her passion for the job was great but as she became “deeply involved” in the United Social Service Employees Union, she put her first career aside to assume the presidency of the New York chapter.

“I could do even more for people, like getting them decent wages, than I could in social work.” Among the union’s accomplishments during her tenure as president, she said, was helping “guarantee social workers were qualified and paid fairly. You had to pay enough in order to get qualified people. We felt if you, as social workers, were going to make decisions impacting people’s lives, you better be qualified to do it.”

Feeling she’d done all she could as union head, she returned to the social work field. While working for a Jewish Federation agency in New York, she was given the task of interviewing Jewish refugees who had escaped growing Nazi persecution in Germany and neighboring countries. Her job was to place new arrivals with the appropriate state social service departments that could best meet their needs. Her conversations with emigres revealed a sense of relief for having escaped but an even greater worry for their loved ones back home.

“They expressed deep, deep concern and deep, deep sadness and fear about what was going on over there,” she said, “and anxiety about what would happen to their family members that remained over there. They worried too about themselves — about how they would make it here in this country.”

A desire to help others was not the only passion stoked in Evie during those ”wonderful” New York years. She met her future husband there while still a grad student. Dashing Jack Zysman, an athletic New York native, had recently completed his master’s in American history from New York University. One day, Evie went to some office to retrieve data she needed on the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, when she met Jack, who was doing research in the very same office. Sharing similar interests and backgrounds, the two struck up a dialogue and before long they were chums.

The only hitch was that Evie was engaged to “a nice Jewish boy in Omaha.” During a break from her studies, she returned home to sort things out. One day, she was playing tennis at Miller Park when she looked across the green and there stood Jack. “He drove from New York to tell me I was definitely coming back and that I was not to marry anybody but him.” Swept off her feet, she broke off her engagement and promised Jack she would be his.

After their marriage, the couple worked and resided in New York, where she pursued union and social work activities and he taught and coached at a high school. Their only child, John, today a political science professor at Cal-Berkeley, was born in New York. Evie has two grandchildren by John and his wife.

Along the way, Evie became a New Yorker at heart. “I loved that city,” she said. Her small family “lived all over the place,” including the Village, Chelsea and Harlem. As painful as it was to leave, the Zysmans decided Omaha was better suited for raising John and, so, the family moved here shortly after World War II.

Soon the couple began Playtime Equipment, their early childhood education supply company. The genesis for Playtime grew out of Evie’s own curiosity and concern about the educational value of play materials she found at the day care John attended. When the day care’s staff asked her to “help us know what to do,” she rolled up her sleeves and went to work.

She called on experts in New York, including children’s authors, day care managers and educators. When she sought a play equipment manufacturer’s advice, she got a surprise when the rep said, “Why don’t you start a company and supply kids with the right stuff?” It was not what she planned, but she and Jack ran with the idea, forming and operating Playtime right from their home. The company distributed everything from books, games and puzzles to blocks and tinker toys to arts and crafts to playground apparatus to teaching aids. The Zysmans’ main customers were schools and day cares, but parents also sought them out.

“I helped raise half the kids in Omaha,” Evie said.

The Zysman residence became a magnet for state and public education officials, who came to rely on Evie as an early childhood education proponent and catalyst. She began forming coalitions among social service, education and legislative leaders to address the early childhood education gap. A major initiative in that effort was Project AID, a program she helped organize that set-up preschools at black churches in Omaha to boost impoverished children’s development. She said the success of the project helped convince state legislators to make kindergarten a legal requirement and played a role in Nebraska being selected as one of the first states to receive the federal government’s Head Start program.

Gay McTate, an Omaha social worker and close friend of Zysman’s, said, “Evie’s genius lay in her willingness to do something about problems and her capacity to bring together and inspire people who could make a difference.”

Evie immersed herself in many more efforts to improve the lives of children, including helping form the Council for Children’s Services and the Coordinated Childcare Project, clearinghouses geared to meeting at-risk children’s needs.

The welfare of children remains such a passion of hers that she still gets mad when she thinks about the “miserable salaries” early childhood educators make and how state budget cuts adversely impact kids’ programs.

“Everybody agrees today the future of our country depends on educating our children. So, what do we do about it? We cut the budgets. Don’t get me started…” she said, visibly upset at the idea.

Besides children, she has worked with such organizations as the United Way, the Urban League, the League of Women Voters, the Jewish Council of Women, Hadassah and the local social action group Omaha Together One Community.

In her nearly century of living, she’s seen America make “lots of progress” in the area of social justice, but feels “we have a long way to go. I worry about the future of this country.”

Calling herself “a good secular Jew,” she eschews attending services and instead trusts her conscience to “tell me what’s right and wrong. I don’t see how you can call yourself a good Jew and not be a social activist.” Even today, she continues working for a better community by participating in Benchmark, a National Council of Jewish Women initiative to raise awareness and discussion about court appointments and by organizing a Temple Israel Synagogue Mitzvah (Hebrew, for good deed) that staffs library summer reading programs with volunteers.

Her good deeds have won her numerous awards, most recently the D.J.’s Hero Award from the Salvation Army and Temple Israel’s Tikkun Olam (Hebrew, for repairing the world) Social Justice Award.

She’s outlived Jack and her siblings, yet her days remain rich in love and life. “I play bridge. I get my New York Times every day. I have my books (she is a regular at the Sorenson Library branch). I’ve got friends. I have my son and daughter-in-law. I have my grandchild. What else do you need? It’s been a very full life.”

As she nears a century of living Evie knows the fight for social justice is a never-ending struggle she can still shine a light on.

“How would I define social justice?” she said at an Omaha event honoring her. “You know, it’s silly to try to put a name to realizing that everybody should have the same rights as you. There is no name for it. It’s just being human…it’s being Jewish. There’s no name for it. Give a name to my mother who couldn’t read or write but thought that you should do for each other.”

Related Articles

- Alberta foster care system under scrutiny (calgaryherald.com)

- Leading article: The care system needs a drastic overhaul (independent.co.uk)

- Feds share blame for child welfare system ‘chaos’ (cbc.ca)

This version of Simon Says positions Omaha Steaks as food service juggernaut

Nebraska doesn’t have mountains or oceanfront beaches. What few iconic things it does have speak to the work ethic of its people. Omaha Steaks is a national brand, like Mutual of Omaha insurance or Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffett, that people know and trust. It’s dependable, just like Nebraskans and the Nebraska family that founded the company and still run it today. This story, which originally appeared in the Jewish Press, is an appreciation for the history and growth of this food industry titan.

This version of Simon Says positions Omaha Steaks as food service juggernaut

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Jewish Press

First cousins Bruce and Todd Simon engage in the back and forth banter of media talk-jocks, except theirs isn’t idle chat but the dialogue of two men at the top of a food service industry company giant whose annual sales fast approach a half-billion dollars. In an interview at the headquarters of their family-owned Omaha Steaks empire, 11030 “O” Street, they revealed themselves as wry sophisticates with a knack for brokering deals, managing people and anticipating the next big thing.

After working together 20 years, their close familiarity finds each interrupting the other to complete a sentence or to make a point or to poke fun. They seem to enjoy the give and take. It’s all part of being the next generation, the fifth to be exact, to lead the corporate giant. Each apprenticed under his dad. Each holds fast to cherished lessons passed down from above.

For 89 years the company’s found innovative ways to market fine meat and other foods to residential and commercial customers around the nation and the world. Along the way the Omaha Steaks name has become such an icon synonymous with quality beef that its hometown enjoys crossover brand recognition.

Bruce is president/COO and Todd is senior vice president, but their bond supersedes titles or labels. They’re family. Two in a long line to lead the business.

“You know what we have? What we have here, we have an entire company of people who we trust — that we feel like we’re family with. That’s what we have here,” Bruce said. “That blood bond is really a family bond and it traverses not only the Simon family, it includes our executive committee, all the way down. There are guys I know in the plant that were there the day I started and I feel the same bond with them as I do to my cousin Todd. We all feel a responsibility to each other to make this place successful.”

As is their habit, Bruce turned to Todd, asking, “Don’t you think?” Whereupon Todd opined, “Well, I think it starts with the fact we’re a family business that allows us to really take those kind of family values into the whole business.”

“Not in a Bush sort of way,” Bruce joked. A nonplused Todd continued, “And it shows in the benefits we provide for our team in terms of family leave benefits or vacation benefits or day care. Scholarships.” “All that stuff,” Bruce interjected.

Legacy is never far removed from the Simons’ thoughts, as their fathers still take an active part in the company, always looking over their sons’ shoulders to ensure the family jewel is well-preserved. Bruce’s father, Alan Simon, is chairman of the board/CEO. Todd’s dad, Fred Simon, is executive vice president. The cousins’ late uncle, Steve Simon, died recently after years serving as senior VP and GM.

“My dad was and is pretty much the operational guy. He’s the guy who ran the meatpacking plant and who was the bean counter,” Bruce said. “Bought the meat,” Todd offered. “Yeah, bought the meat,” Bruce confirmed. “And Todd’s dad was the real marketing guy and Steve (Simon) was the sales guy.”

The three brothers — Alan, Fred and Steve — learned the business from their father Lester Simon, who in turn learned it from his father B.A. Simon. It all began when B.A. and his father J.J. Simon, both butchers, left Latvia for America in 1898 to escape religious persecution. With the meat business in their blood, J.J. and B.A. settled in Omaha, a meatpacking center, and worked in several area markets. In 1917 father and son opened their own meat shop, Table Supply Meat Company, downtown. Their niche was to process and sell beef to restaurants and grocers.

As the decades progressed Table Supply responded to the growing food service sector by supplying meat to Union Pacific Railroad in support of its large dining car services as well as to more and more restaurants here and in other parts of the country. Cruise lines, airlines, hotels and resorts became major customers. Lester Simon first took Table Supply to the public via mail order ads that enabled households to receive packaged shipments of cut beef. In 1963 the company published its first mail order catalog, whose product offerings soon extended far beyond beef steaks. Shipping-packaging advances improved efficiency, helping widen the company’s increasingly national and international reach.

By 1966 all this growth warranted an expansion in the form of a new plant and headquarters on South 96th Street. With the new facilities came a new name, Omaha Steaks International.

The 1970s saw Omaha Steaks take new steps in customer convenience by adding inbound and outbound call centers and a mail order industry-first toll-free customer service line. An automated order entry system was installed in 1987. The first of its retail stores opened in 1976. There are now 75 and counting in 19 states. Visioning the online explosion to follow, Omaha Steaks helped pioneer electronic marketing as far back as 1990. Omahasteaks.com became the banner web site for what is the company’s fastest growing business segment. A new web site, alazing.com. promotes the company’s convenience meals brand, A La Zing, which offers a line of complete frozen prepared meals.

Omaha Steaks underwent another expansion phase in the ‘80 and ‘90s, consolidating administration and marketing in two new multi-story glass and steel buildings whose sleek interiors abound with examples from the Simons’ extensive art collections and displays that tell the history of the family business.

In a family of arts supporters, Todd’s an elected member of the Board of United States Artists and board president of the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts.

If Bruce and Todd feel burdened carrying the legacy of a company that boasts two million-plus customers and employs some 2,000 folks, they don’t show it. Guiding their interaction in family and business dealings are the principles they picked up from their elders. By living those principles they fulfill their obligation.

“Our parents taught us to do the right thing. That’s really the only responsibility we have — just do the right thing. Do it all the time. Try to produce every single box of product perfectly. Try to satisfy every single customer perfectly. Do it right every time,” Bruce said. “It’s all about being honest. Everybody in our family has been impeccably honest. We don’t take advantage of people. We sleep good.”

“Right,” Todd said, “and I think it also extends to the environment we create. We could sit around and stress out about the fact we have 2,000 employees and their livelihoods in a lot of ways depend on the decisions we make. And I think we always have that in mind. I also think one of the things that makes it so we don’t stress out is that so many of those 2,000 people think the same we do and they take responsibility for what they need to take responsibility for. And because they do that the stress we carry is minimized.”

“But the whole thing is doing the right thing,” Bruce said. “I mean, if you’ve got building blocks and you set them up properly you’re going to have a very strong building. And that’s what we have and it’s because of every single block. Look, if spacemen came and took either one of us away there’s no question in my mind…this place would continue on because of the values that J.J., B.A., Lester, Alan, Fred, Steve and now Todd and I hold dear. It’s our whole corporate culture.”

The confidence they exude may be attributed in part to the up-through-the-family-ranks training the pair got and to the well-balanced team they form.

“It’s interesting,” Todd said, “because I think in a lot of ways we’ve both sort of followed in our fathers’ footsteps. You know, Bruce is very strong operationally, purchasing, finance…All the sort of back-office stuff is his forte. And mine is the out-front stuff — the marketing, sales. Managing the customer service aspect of that, motivating the front-line people to be people-people.”

“And somebody has to manage him, too,” kidded Bruce, before turning serious again. “Yeah, I think that when you’re a leader sometimes you’ve got to fake it. My dad used to say to me, ‘When in command, command.’ And that’s what I think we do. I mean, our dads built a helluva business and, you know, you always want to top it. I mean, George W. (Bush) just had to get Saddam and we’ve just got to sale a steak to every Chinaman,” Bruce said, smiling.

Unfazed, Todd said, “I think Bruce and I really complement each other well. I would say I’m an optimist and Bruce isn’t as much an optimist…in the sense that when we both come up with ideas I’ll see one side of the picture and he’ll see the other side of the picture. And since we’re both open too each other’s perspective on it, it really helps us balance it out.”

The way Bruce puts it, “I think our management styles complement each other as well. He is really detail-oriented sometimes and I am really detail-oriented when he’s not. And about different things. There’s some stuff that Todd goes, ‘Well, so, get it shipped.’ And I just look at him and I go, ‘OK…well, just sell it.’ He looks at me and says, ‘OK.’” Whatever the situation, they make it work. “Yeah, we do,” Bruce said, “and we get along, which is great, too.”

With two father-son teams comprising the ownership-executive ranks, the potential exists for family disputes that upset the company’s inner workings. The Simons diffuse those bombs with open dialogue and transparent dealings.

“For as long as I can remember the way we operate as a family is we get our ideas out,” Todd said. “We don’t bulldoze over each other. We’re all forceful about our ideas and our opinions, and we’ll raise our voices and we’ll do whatever we need to do to get our point across. But we basically come to consensus and we don’t leave the room unless everyone’s comfortable with the direction we’re moving in.”

“Right,” Bruce said. “We don’t fight about things. If there’s a reason to do something we discuss it and we figure it out. Because, hell, we’re all on the same page. What’s good for one is good for all. We’re never very formal, either. Usually we’ll discuss things over lunch.”

Talking business within the family doesn’t follow a 9 to 5 schedule. “Business doesn’t stop and start at the office for us,” Todd said. “I mean, Bruce could be on vacation and just decide to call me about something that’s on his mind.” “Well, technically, what will happen,” Bruce said, “is when you’re away from the place and the day-to-day that’s when you really get some good ideas and then we’ll call each other. I remember before cell phone were prolific I was in Italy and Todd was in Japan and we had this fax dialogue going on.”

Vision is important in any organization and each year Omaha Steaks holds an off-site brainstorm session with its top managers. Ideas and initiatives fly. “A lot of times those come not from me or Bruce but from the people out there in the trenches dealing with our customers every day,” Todd said. In the end, “Todd and I decide with our fathers where we’re going” as a company, Bruce said.

Two affiliate companies sprung from this visioning — the A La Zing line of convenience meals and OS SalesCo., an incentive division. Fred Simon entered the publishing world with The Steak Lover’s Companion, a cookbook co-authored with Mark Kiffen. Simon adapted classic dishes from recipes developed by James Beard, an Omaha Steaks consultant for many years. More cookbooks followed. Simon’s developed Omaha Steaks-affiliated restaurants. Many more restaurants exclusively serve the Omaha Steaks brand on their menus. The company’s also approaching 100 of its own retail stores nationwide.

Trust in themselves and in the team they’ve assembled explains why the Simons are open to new marketing avenues and new technologies that enhance the ability of the company to serve customers. A toll-free customer service line. Online ordering. In-store purchases. New product lines. Seasonings, sides, desserts. Whatever passes muster with the Simons or in the Omaha Steaks test kitchens gets rolled out.

“While we have innovated a lot here and we’ve developed a lot of proprietary tools and analysis and internal stuff, I wouldn’t say we’ve been on the bleeding edge of technology,” Todd said. “Because I think what we want to do is to use technology that’s going to help us to help our customers. We were one of the first companies to put in an 800 number because it made sense to help our customers communicate with us. When we implemented a centralized computer system one of the first applications was order taking.”

“We’ve had to do these things. The Internet was just very logical — Sure, we should have that. And the fact the entire world put a PC in their living room helped,” Bruce said. “But it was easy for us because when you think about it we were just bypassing the guy on the phone.”

As “easy” as he makes it sound, Bruce added Omaha Steaks has taken great pains to enhance its order-processing systems via the Web and the phone. “I’ve seen a lot of them and I’m proud of ours — I think it’s the best one I’ve ever seen. Our development team has done such an outstanding job with those products.”

“I still think what it gets back to is that we say to ourselves, How do we solve a problem for our customers? Whether that problem is placing an order quickly and efficiently or being able to log onto the web site and access their gift list or whatever it is. And then asking, Can technology help us with that? As opposed to implementing technology in search of a problem” to solve,” Todd said.

Online sales account for an increasing chunk of the company’s profits and Omaha Steaks will accommodate the dot com craze as the demand dictates.

“Our philosophy is be wherever your customers want you to be,” Todd said. “A lot of people love to shop online. I’m one of those people. But we’ve got a lot of customers today that don’t. People still fax orders in. People still mail orders in. People like to come into our stores. So, whatever works.”

The retail segment has “grown as fast as we’ve been willing to add resources internally to support it,” Todd said. Plans call for 15 more stores this year alone. That may seem an odd way to go with cyber commerce on the rise, but he said even a cursory look around town reveals a boon in retail development. “So the economy is alive and well for a number of different sales channels to prosper.”

Success may make some tycoons complacent but not the Simons.

“I feel like with this business I can be an entrepreneur. There’s always new challenges, new products to be developed or whatever. That gives me a lot of satisfaction,” Todd said. “What gives me a charge is just seeing the business grow, being successful in business, messing around with our dads in the business. And just the sheer volume of product we go through — it’s just staggering sometimes,” said Bruce, who figures Omaha Steaks processes up to 250,000 pounds of just top sirloin each week and close to 50,000 pounds of tenderloin a week. That’s tens of millions of pounds of beef a year.

They’ve been at Omaha Steaks a combined 46 years now — Bruce since 1980 and