As Eduardo Aguilar walked down an Omaha Creighton Prep hallway one school day last April, he had no idea a lifelong dream would soon be secured. Counselor Jim Swanson pulled the then-high school senior out of his international relations class on the pretext of seeing how he was doing. It’s something Swanson often did with Aguilar, whose undocumented parents were deported to Mexico when he was about ten. Aguilar lived with Swanson and his family an entire year – one in a succession of homes Aguilar resided in over six years.

The counselor and student talked that spring morning as they had countless times, only this time school president Father Tom Neitzke joined them. The priest shook Aguilar’s hand and invited him into his office, where several adults, including media members, awaited.

“I was confused and shocked,” Aguilar recalled. “I thought I was in trouble.”

Creighton University president Father Daniel Hendrickson then informed him he was receiving a full-ride scholarship worth $200,000 funded by donors and the G. Robert Muchemore Foundation.

Cameras captured it all.

“To have that news thrown at me out of nowhere was incredible,” Aguilar said. “I just felt like God answered my prayer because it was always my dream to go to Creighton. I was so happy.

“I still can’t believe it even happened. I’m forever grateful for the scholarship donors and for the people that believed in me.”

KMTV Channel 3 news reporter Maya Saenz, who filed a touching story on him, came away impressed by Aguilar.

“He’s a brilliant and hardworking guy and I feel privileged to have met him and to have highlighted his extraordinary efforts to reach the Mexican-American dream.”

The scholarship came just as Aguilar despaired his dream would go unrealized.

“There weren’t many options for me at that time and I was thinking, ‘Maybe this is the end of my journey – maybe I’m not going to go to college.’ I was in a bad mood about it that same day.”

After learning his good fortune, he called his parents, Loreny and Jose Aguilar.

“They were extremely excited to hear I’m continuing my education, especially at Creighton University, because they knew from a very young age I wanted to go there, They’re absolutely humbled their son received such a generous gift to attend such a prestigious place and that people believed in their son.

“Even though not having them here physically hurts, they’ve motivated me throughout. They’ve given me words of wisdom and advice. They’ve definitely pushed me to be best that I can.”

Aguilar also appreciates the support he’s received in his folks’ absence, first at Jesuit Academy, then at Prep, and now at CU, where he’s finishing his freshman year. He didn’t get to say goodbye to his parents, who are general laborers in Tijuana, when they got deported. He and his older brother Jose relied on family and friends.

“It was a very traumatizing experience,” Aguilar said. “I felt powerless. It really opened my eyes to the harsh place life can bring you at times. It definitely made me mature a lot faster than my peers.”

Jesuit Academy staff rallied behind him.

“They assured me everything would be okay, I decided I had to kick my academics into gear because it was the only thing to get me ahead without my parents here.”

Three months after that sudden separation, Aguilar and his folks were reunited in Mexico. He lived three years there with them.

“I enjoyed it down there with family. I learned a lot. It really humbled me and made me into the person I am today. Now, I’m just happy to be getting my education. I don’t really care about material possessions.”

By 13, his yearning for America would not be denied.

“I realized in Mexico I wouldn’t have the same opportunities I would here. My mom was very hesitant about me coming back because I was so young. But she agreed. Leaving was very difficult. I came back with a family member. I ended up staying with him for awhile and then i just moved from house to house.

“It’s been a journey.”

Few of his peers at Prep knew his situation.

“The majority of them found out on graduation day, They were surprised because they never saw me upset or sad. I was always smiling, happy. They were astonished I was able to go through all that, but it’s due to the support system I had.”

Prep staff took him under their wing his four years there.

“Jim Swanson has been a great motivator. He and his wife served as my second family. When I needed them the most, they opened the doors to their house to me. I see him as my second father. I have the utmost respect for him and his family.”

Aguilar also grew close to art teacher Jeremy Caniglia

“He left a great impact on me. I still reach out to him.”

Aguilar used art and slam poetry to process and express his intense feelings.

In college, he’s found professors sympathetic to his plight. He calls CU Vice Provost for Enrollment Mary Chase “one of my go-to persons,” adding, “She always checks up on me.”

“It really means a lot to me to have extra structure and support and to know these people actually care and believe I have potential to do something in life,” Aguilar said.

He’s studying international business and corporate law in CU’s 3-3 program, which will allow him to earn an undergraduate degree and a law degree in six years instead of seven. His dream job is with Tesla Motors, which produces mass-market electric cars.

“Renewable energy has always fascinated me and Elon Musk (Tesla founder-CEO) has always been one of my idols.”

Thus far, Aguilar said, “College has been an incredible, eye-opening experience.”

Aguilar hopes his personal story empowers others caught in the immigration vice.

“If this can serve any person going through a similar situation or hardship and help them to succeed, then I’m totally for that.”

Archive

Omaha Storm Chasers part of Minor League Baseball push to cultivate Latino market

Been late posting some El Perico stories I had publsihed in July and August 2018. This is one of them.

Omaha Storm Chasers part of Minor League Baseball push to cultivate Latino market

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico (el-perico.com)

Baseball has long been an international sport. Its deep roots throughout Asia, Latin America, South America,Canada, Mexico, and Puerto Rico are well reflected in minor and major league team rosters in the United States.

To see this Latin influence, look no further than the Triple A Omaha Storm Chasers. The current roster includes players with the surnames Torres, Lopez, Arteage, Villegas, San Miguel, and Hernandez. Others, including top prospect Adalberto Mondesi, have been with the club in 2018. Two key players with the parent Kansas City Royals, Salvador Perez and Paulo Orlando, served rehab assignments here earlier this summer.

The emergence of Latino players – they comprise 27 percent of MLBers today compared to 14 percent in 1988 – has happened as America’s Latino population has exploded. Professional baseball knows that to stay relevant to diverse audiences, it must market the game to growing minority segments represented on the field. Thus, in 2017 Minor League Baseball initiated the Copa de la Diversión series or Fun Cup in celebration of Hispanic culture. Four franchises test-marketed the series. This year, 33 franchises are participating, including the Storm Chasers.

Teams designate select home dates as Copa games featuring Hispanic-themed uniforms and names, special community guests, and traditional cultural food, music, and dancing. For Copa, the Storm Chasers become Cazadores de Tormentas at Werner Park. The team played as the Cazadores on June 7, June 21 and July 21 and will close out the Copa series as the Cazadores on Thursday, August 2 at 7:05 p.m., playing against Las Vegas.

Showing off Latin roots and playing before Spanish-speakers is “fun”, according to Chasers utility player Jack Lopez. The Puerto Rico native added, “It’s an honor to be able to participate. Representing our countries is something we take pride in.”

Rosendo Robles will sing the national anthem prior to the start of the August 2 game. A post-game celebration concert will feature performers Marcos & Sabor, Alexis Arai and Premo el Negociante.

Chasers General Manager Martie Cordaro said his organization is focused on cultivating the Hispanic market here moving forward.

“This is a long play for us that’s based in community as we create and make relationships. The long play is this is a growing population nationally and specifically here in the metro area. We want them to look at us just like they do the Henry Doorly Zoo or Funplex or Pizza Machine or Cinco de Mayo. We want to be right there with their entertainment decisions.

“Sales is really secondary to what we’re doing right now. It’s not just another immediate promotion to sale tickets. We hired a staff member specifically for the community outreach it entails.”

Venezuela native Jhonnathan Omaña, a former Montreal Expos prospect and longtime Omaha resident, was hired in January as the club’s first multicultural marketing lead.

After years of experience in marketing, customer service, and promotions, Omaña enjoys being back in baseball using his bilingual and community relations skills.

“I have the opportunity to see baseball behind the scenes, in the front office, to make connections with the community and to facilitate interactions between the players and coaches and the fans. We’re reaching out to community businesses, nonprofit organizations, and schools, and we’re at different events. I get the chance to see baseball from a whole different perspective. That’s what really attracted me the most about this position.”

Baseball runs deep in his heritage.

“I’m from a country where baseball is big. Baseball has been in our family a long time and is a big part of our family.”

His grandfather Lucindo Caraballo was a legendary player with Los Leones del Caracas and is a candidate for Venezuela’s national baseball hall of fame. Omaña was talented enough to get a look by the Expos. A younger brother played community college ball in Nebraska.

Omaña sees his job as building on the goodwill the franchise has established in its 50 years in Omaha.

“The relationship with the Hispanic community was already there,” he said. “I’m just contributing to making that relationship stronger.”

GM Cordaro acknowledged more needed to be done before Copa.

“I don’t think traditionally minor league baseball has done all it could to target all demographics,” he said. “Minor league baseball is a great sport. It draws 42 million fans a year – outdrawing the NFL and NBA combined – but there are additional groups and demographics we’re not directly speaking or had not been to prior to the Copa program.”

“I think this is an opportunity to say, yes, we are the community’s ballclub, not just the traditional baseball fans’ ballclub. I think what the Copa program does is to be a little more inviting, a little more welcoming. That’s really what Jjonathan [Omaña] has been tasked with,” GM Cordaro said.

Eduardo Aguilar: Living a dream that would not be denied

Living a dream that would not be denied

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in El Perico (el-perico.com)

Rosales’ worldwide spiritual journey intersects with Nebraska

Rosales’ worldwide spiritual journey intersects with Nebraska

Victoria Rosales is a seeker. At 27, the Houston, Texas native is well-traveled in search of self-improvement and greater meaning. She’s dedicating her life to sharing what she knows about healthy living practices. Her journey’s already taken her to Ireland, England, Kosovo, Vietnam, Alaska, Mexico and Costa Rica.

From her Salt Lake City home, she handles communications for Omaha-based Gravity Center for Contemplative Activism. Its husband-wife team, Chris and Phileena Heuretz, lead workshops and retreats and author books. Rosales met them at the 2012 Urbana student missions conference in St. Louis. She took their contemplative activism workshop and participated in retreats at the Benedictine Center in Schuyler, Nebraska. The experiences enhanced her spiritual quest.

“I remember writing in my journal, ‘I love their message and mission and I would really love to do the work these people do.’ And now – here I am,” Rosales said.

Meditation came into her life at a crucial juncture.

“I was in a season where the idea of resting in the presence of God was all that I longed for.”

A few years earlier she’d left her east Texas family to chart a new path.

“I am a first-generation high school and college graduate. I’m carving my own path, but for the better – by doing things a little bit differently. In that way, I definitely see myself as a trailblazer for family to come.”

She grew up an Evangelical Christian and attended a small private Christian college in Michigan, where she studied literature, rhetoric and storytelling.

“The idea of telling a story and telling it well and of being careful in the articulation of the story really began to come alive for me. I began to pursue avenues of self-expression in terms of word choice and dialect.”

As a child enamored with words, the tales told by her charismatic grandmother made an impression.

“I was heavily influenced by my grandmother. She captivated an audience with her storytelling. I was raised on stories of her childhood coming out of Mexico. It was very much instilled in me. I see it as a huge gift in my life.”

But Rosales didn’t always see it that way.

“Growing up, it was like, ‘Here goes grandma again in Spanish. Okay, grandma, we’re in America’ – shutting her down. When she passed away, reconciling those prejudices became a huge part of my journey. I moved to Mexico for that very purpose and spent time living with my distant relatives, mostly in Monterey, to truly embrace what it means to be this beautiful, powerful, sensual Latina and honor that part of who I am.

“Part of creating a safe place for others to show up as who they are is feeling safe in my own skin and appreciating the richness of my Hispanic heritage.”

Self-awareness led her to find a niche for her passion.

“It started with me being really honest about telling my story with all of the hurts and traumas. I could then invite in light and life, healing and redemption.”

Her work today involves assisting folks “sift through the overarching stories of their life and to reframe those narratives in ways more conducive to personal well-being.” She added, “It’s moving from victim mentalities into stances of empowerment through how different life experiences are articulated. I developed my own practice to help people journey through that.”

She calls her practice Holistic Narrative Therapy. It marries well with meditation and yoga. She’s learned the value of “silence, solitude and stillness” through meditation and centering prayer.

“In silence you take time to sit and listen to find the still small voice within, the rhyme and reason in all the chaos and loud noise. In stillness you learn to sit through discomfort. In solitude you learn to remove yourself from the influences of culture, society, family and expectation and to be comfortable with who you show up as when no one else is watching. Those are the roots and fruits of the contemplative life.”

Doing yoga, she believes, “is the embodied expression of dance with the divine.” After attending a yoga resort-health spa in Costa Rica, the owners hired her to conduct Holistic Narrative Therapy sessions. She said everything about the setting invited restoration – “the lush jungles, the pristine beaches, the blue waters, the food that grows there, the music, the vibe.”

After that idyll. she roughed it by working as a wilderness therapy guide in Utah with youth struggling with anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation.

“Being one with the elements provides a lot of space for growth. I was just naturally attracted to that. That was a great experience.”

En route to starting that job she was driving through Zion National Park when she took her eyes off the road and her SUV tumbled down a cliff. She escaped unharmed but chastened. This heady, strong, independent woman needed bringing down a notch.

“I was falling into a trap of playing God in my own life. You don’t want to take rolling over a cliff to learn a lesson, but I guess I needed to be knocked off my center to re-land on something fortified and true.”

She now works for a Salt Lake youth therapy program.

“My dream is to open a community center for people to come and experience restoration and what it means to be fully alive, fully human.”

She rarely makes it back to Neb., but she did come for Gravity’s March Deepening Retreat in Schuyler.

“I am a firm believer we can only extend the love to the world we have for ourselves. That’s truly what these retreats are for me – to fill my own tank so that I can go out and serve the world to the best of my abilities.”

Visit http://www.facebook.com/public/Victoria-Rosales.

Heartland Dreamers have their say in nation’s capitol

Heartland Dreamers have their say in nation’s capitol

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico (el-perico.com)

Self-described social justice warrior, activist and community organizer Amor Habbab-Mills cannot sit idly by while lawmakers decide her fate as a Dreamer and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipient.

With President Donald Trump’s deadline for Congress to revamp DACA unmet last fall, she organized a September 10 rally in South Omaha. Dreamers and allies gathered to show solidarity. She then shared her story in a Lincoln Journal-Star op-ed and in the locally produced documentary and play We Are Dreamers.

“It was great because people got to know a little more about our struggle,” she said.

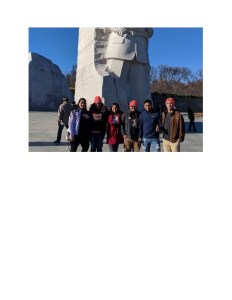

Two weeks ago, with the March 5 deadline looming and redoubled U.S. immigration enforcement efforts placing more undocumented residents in detention, awaiting possible deportation, tensions ran high. True to her “drive to speak up against injustice,” she led a group of Nebraska Dreamers to Washington D.C. to join United We Dream demonstrations demanding Congress act to pass protections and paths for citizenship. It did not.

Thus, those affected like her remain in limbo with DACA provisions slated to end pending a new program.

She’s in the process of obtaining her Green Card.

Before she and her fellow travelers could make the trip, they had to find funds to cover air fare. United We Dream picked-up meals. She donated the hotel tab.

“We raised $1,676,” she said. “It was nice to see our community had our backs and they wanted us to go to D.C. This trip was so important to me and the local movement.”

The Omaha contingent arrived Feb. 28 and returned March 6. They were joined by activists from Centro Hispano in Columbus, Nebraska. The groups coordinated schedule to walk in a planned march.

“My goal was to be there when the Dream Act passed. I had a lot of hope the government would act on March 5 or before,” she said. “I wanted to be there to witness history happen. It did not happen. It was sad. But it was good to be there with other Dreamers. We just get each other. We know exactly what each other has been through. We all share the same heartbreak, the same roadblocks, the same fears.

“The trip opened our eyes about what’s going on in our government and how the Trump administration is pushing its racist agenda on our community.’

She won’t soon forget the experience of rubbing shoulders with thousands of kindred spirits, voicing pro-DACA chants, carrying signs with slogans, and seeing some protesters engage in acts of civil disobedience that resulted in arrest. All unfolding in front of national symbols of power, including the White House.

“It was empowering. It was a breath of fresh air and a reminder we’re not alone in the fight. it made me feel not as afraid, not as worried. It put things into perspective.

“The march was really the highlight of the visit. That’s why we went there. We walked to Capitol Hill. We had an ‘artivism’ moment where we put some paper flowers on the ground that read: ‘We Rose Unafraid.’ We wanted to beautify the word undocumented to bring attention that we’re not afraid” (and not apologetic).

“It was a great experience. It opened my eyes to how much support we actually have,” trip participant David Dominguez-Lopez said.

The local group plead their case to Nebraska Republican Congressman Don Bacon.

“We did a (peaceful) office takeover of Rep. Bacon’s office,” Habbab-Mills said. “We went there because he’s said he supports Dreamers. We appreciate that. But we don’t appreciate him supporting bills, such as the Secure and Succeed Act, that will harm our community.”

The proposed legislation seeks to secure the border, end chain migration, cancel the visa lottery and find a permanent solution for DACA tied to building a wall.

“We were there sharing our stories, chanting and asking him to not vote for the Secure Act. It’s this horrible bill that would build a stupid wall, give more money to the Department of Homeland Security so they can do raids and put more agents on the street.”

Given the Republican majority’s anti-immigration stance, Habbab-Mills is leery of promises. Distrust intensified when leaked government memos revealed discussions to use the National Guard to maintain border security

She’s concerned “more families are going to be apart” in the wake of immigration crackdowns.

“On a personal level, if my mom were to get pulled over by a cop who does not like immigrants, she faces a good chance of being deported. The fact I cannot help her, breaks my heart. Under the current political climate, we need a way to protect family members under attack.”

Another goal of the trip was “to plant the seed of social justice with the Dreamers who went,” she said, “and that’s what’s happened,” adding, “Everyone’s ready to get things going back home to stop the Secure Act.”

“it inspired me to learn more and be active in my community and to work with Amor and the rest of the ‘D.C. gang,'” said Dominguez-Lopez.

Habbab-Mills traces her own social activism to seeing disparity growing up in Mexico City and to doing Inclusive Communities camps here. She earned high marks at Duchesne Academy and Creighton University. She founded the advocacy group Nebraska Dreamers. She works as a legal assistant at a law firm and is eying law school. She hopes to practice immigration and human rights law.

Meanwhile, she amplifies Dreamer’s voices for change.

“If we’re not the ones speaking up, who else will? We want people to know we are educated and even though we cannot vote, we have the power to influence people on how they vote. Social media is huge for us.

“Bringing awareness to the issues is a way of creating change. Planting that seed will bloom into a more just society one day. I think it’s a duty to speak up when something’s not right. If i don’t, I’m part of the problem.”

Follow Nebraska Dreamers on Facebook.

Having attained personal and professional goals, Alina Lopez now wants to help other Latinas

Having attained personal and professional goals, Alina Lopez now wants to help other Latinas

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico (el-perico.com)

When new UNO Office of Latino and Latin American Studies community engagement coordinator Alina Lopez appears at public forums and school assemblies to tout OLLAS academic programs and scholarships, she speaks from experience.

This 2017 magna cum laude University of Nebraska at Omaha graduate found OLLAS opportunities herself as a volunteer and a Next Generation Leadership scholar.

Embedded in her outreach is a desire to help Latinas pursue higher education. She doesn’t want them deferring their dreams due to challenges like those she faced as a young mother in a domestic violence relationship. She lets aspirants know obstacles don’t need to prevent attaining goals. She delayed her college studies a decade until leaving her abuser. Once free, she shined in the classroom and blossomed as a woman and as a professional.

Born in Michoacan, Mexico, she was 3 when her family moved to Santa Barbara, Calif., where they lived until she was 12. Then they moved to Ogden, Utah. Concerns about undocumented status and the death of her grandfather prompted the family’s return to Mexico. Though an exceptional student, she struggled in Mexican schools and convinced her parents to let her return to the States.

She joined an older sister then living in Bellevue, Neb. Lopez graduated from Bryan High School – the last of five high schools she attended.

“I think I grew to be okay with change. I can adapt very well. But when you’re 15-16, parental guidance is essential. Not having that was the toughest part.”

Lopez married young and began having children. She’s the mother of five today.. She was an Omaha Public Schools ESL specialist and administrative aide at her alma mater, Bryan, where she helped coach girls soccer. Assistant principal Tracy Wernsman emboldened her.

“She was a mentor who was like an angel sent from God,” said Lopez. “She talked me through things like, ‘If you leave that relationship, you’ll be okay, you can do it,’ and so in 2011 I finally had the guts to say, ‘No more.’ Tracy told me I had great potential and needed to pursue college. Once I became liberated, I pursued it.”

Another strong influence has been Spring Lake Magnet principal Susan Aguilera-Robles.

“She is a great role model for me. She’s gone through a lot and dedicated her life to helping others. Being the principal of a school takes a lot. I know she has really bad days and really good days, but she’s made it work

and she makes it look easy.”

Lopez worked multiple jobs to support her family while earning an associate’s degree from Metropolitan Community College. Then she enrolled at UNO.

“Trying to figure it all out was very challenging and stressful, but well worth it.”

None of it was possible without first taking her life back.

“It makes you a stronger person. For a woman to get out of it is empowering. It makes you want to mentor other females going through the same. You don’t want anybody else to go through what you went through.”

School provided sanctuary and affirmation.

“After being divorced, you feel like a failure. When I enrolled in college I wanted to feel good about myself and to make up for lost time. It was a personal goal to attain a 4.0 GPA and I did it. I’m hungry to learn. I’m hard on myself. I want to give the best of me. I know what I’m capable of and so I push myself. School has always been my safe place. When I’m studying, it feels peaceful, so I’ve dedicated myself to school.”

She’s now eying a dual masters program in public administration and social work. She expects to earn a Ph.D. as well.

Her curiosity extends beyond books. She participated in an international student program that took her to Hong Kong for five weeks last summer, where she joined other students from around the world. “I thought if I don’t do it now, I’m never going to do it, and it was life-changing. If I could go back, I’d do it all over again.”

She went beyond her job description at Bryan to influence young people.

“I was drawn to the kids who carried the most challenges with them. I wanted to know who they were, what they were going through. I also encouraged Latinas to seek post-secondary scholarships. It felt really good.”

While studying at UNO, Lopez became a regular in the OLLAS office and when the community engagement coordinator post opened, it seemed a perfect fit.

“Every single thing has led me to this point. I saw UNO and OLLAS offered the opportunity for more growth and academic success. We’re here to support students.”

She envisions one day realizing another dream – “to start an organization dedicated to young Latino women.” “I feel sometimes we let our culture oppress ourselves,” she said, “especially the immigrant community. We tend to look at our culture as more important than anything. For me, the thought of divorce was not even an option because when you marry, you marry until death do you part. A lot of women stay in a bad life and don’t receive support from family to leave it. I wish to help Latinas who don’t find support elsewhere.”

Lopez, who formed a single parent group at UNO, has come a long way herself.

“It’s been quite the journey.”

A book a day keeps the blues aways for avid reader and writer Ashley Xiques

If you’re like me, sitting down with a good book is a distinct pleasure and there have been times in my life when I would plow through a fair number of books in the course of a year. It’s been a long time since that was true. As a writer, I’m not proud of that. But even at the height of my reading habit I was never into books the way Ashley Xiques is. She’s not sure how many she’s read but she’s virtually never without without a new book to read, which means as soon as she finishes one, she’s onto another. She’s into young adult fantasy and other genres of fiction. She just can’t get enough. It’s been like this for her since her early teens. I wouldn’t be surprised that at age 20 she’s already surpassed my lifetime account of books read. Like most good readers she’s also a good writer. She’s shared her writng online via different platforms, including Odyssey. The twin passions of reading and writng merged a couple years ago when as an Elkhorn South student she won the national Letters About Literature contest for Nebraska for the letter she penned to author Leigh Bardugo. She’s now a sophomore at UNO. Since she works and attends school full-time, she doesn’t have much time to write these days, but she always makes time for reading. Still undecided on a major, she doesn’t plan to study writng but she does expect to write a novel one day. I don’t doubt she will and if she does I will add her work to my long neglected reading list.

Ashley Xiques

Self-described “full-time book addict” who’s “overly enthusiastic about fictional people.”

A book a day keeps the blues aways for avid reader and writer

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

There are book lovers and then there’s Ashley Xiques, an Elkhorn South graduate and UNO sophomore.

The 20-year-old caught the bug after being swept away by a Young Readers fantasy series in her early teens. Countless books later, she’s now a self-described “full-time book addict.”

“I can’t go like even two days without reading a book – it drives me crazy,” she said.

Her habit’s filled several book shelves at home and finds her often hunting new reads at bookstores and in online reading communities.

“I go around taking pictures of books and post them and I talk to other people about books online. I’ve found so many recommendations on Goodreads through people from all across the United States and the world. It’s just a way of connecting through books.”

Her Facebook timeline, Pinterest page and Instagram page brim with book chatter.

“There’s so many ways of finding good books. I’m on those sites. too, for inspiration about characters and stories. Whenever I read new books I want other people to find out about them, especially if they’re not popular. I want people to find them so we can talk about them together.”

She’s also shares her literary musings with fellow bibliophiles on Odyssey.

Her admiration for the Grisha series by New York Times best-selling author Leigh Bardugo led Xiques to enter the national Letters About Literature contest through a high school creative writing class. Ashley’s letter won her age category in Nebraska.

As soon as she came across her first Bardugo book, she was hooked.

“It was one of the very first fantasy books I read. Fantasy’s still my favorite genre.”

She calls herself “a fantasy nerd” online.

The Grisha trilogy captured her imagination.

“It was very addictive. Leigh’s a really good author. I like her writing style and her storytelling.”

Ashley’s letter draws parallels between themes in the series and her own life. For sample. the series deals with what it’s like to feel adrift. She related to that as her large family – she’s one of eight siblings – moved several times following her now retired Air Force father’s military base assignments.

“We moved around a lot. We moved all around Texas (where she was born), then to Virginia, back to Texas and then to Nebraska eight or nine years ago. I don’t mind moving – it’s nice to see new things and meet new people. But, yeah, it’s nice to be settled, stable and have a set group of friends and not have to leave them.

“Sometimes it’s difficult to readjust your life again.”

I need a home. Not a house, I’ve known a plethora of those.

-from Ashley’s letter

Like a series character, she doesn’t like being labeled things she’s not. She took offense at being called spoiled and selfish by other kids.

“I’ve never been like that. I’ve never been someone that things are just given to. I’ve always been a person who’s worked for what I want. My parents don’t buy me everything. I work for myself, I work for my grades, I work for my money. But people want to put labels and stereotypes on you. People judge before they understand the situation and the person and who they actually are.”

Before anyone actually knew the person I was, society had already placed a label on my shoulders. Time to prove them wrong.

I could. I would. I did.

-from Ashely’s letter

Xiques also identified with an outsider character because she sometimes felt like the odd sibling out as the third oldest sibling and then having to try and fit in as the new kid on the block.

Writing the letter helped her express things she couldn’t always verbalize. She went through several drafts. Two days before the deadline, she rewrote it in a single sitting.

“I do good under pressure. I didn’t edit it or anything. I just said, ‘OK, this is what I’m feeling and that’s what it’s going to be.’ That’s why I was kind of shocked when it won. It’s cool though.

She’s an old hand at writing: reviews, essays, poems. She once started her own spy novel. Fifty thousand words worth. She sent friends each new chapter. Then she decided it wasn’t good enough and abandoned the project. She laid out the plot and characters for a new book before putting it aside, too, but she’s hatched new ideas for it.

“I’ve spinned the original idea into something completely different. If I were to do it now, I’d be torn between writing a fantasy book or a realistic modern fiction book. I think I will eventually write a book if I come up with a good (enough) idea.”

It will have to wait though. She’s too busy now working a job and carrying 17 credit hours at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. At her parents urging Xiques long ago set her sights on college. She credits reading with her excelling in school. She made the UNO Dean’s List.

“I know reading helped a lot with that. It boosted my comprehension skills in all different subjects.”

As glad as she is to be settled, she anticipates one day returning to Texas to live. Wherever she ends up, books will be part of her life.

Meanwhile, she’s cultivating new readers in her family.

“My two younger brothers like to read. They go with me to bookstores when I’m out looking for new titles. They view it as an adventure.”

Follow Ashley’s literary adventures at http://www.theodysseyonline.com/@ashleyxiques.

South Omaha stories on tap for free PlayFest show; Great Plains Theatre Conference’s Neighborhood Tapestries returns to south side

Omaha’s various geographic segments feature distinct charecteristics all their own. South Omaha has a stockyards-packing plant heritage that lives on to this day and it continues its legacy as home to new arrivals, whether immigrants or refugees. The free May 27 Great Plains Theatre Conference PlayFest show South Omaha Stories at the Livestock Exchange Building is a collaboration between playwrights and residents that shares stories reflective of that district and the people who comprise it. What follows are two articles I did about the event. The first and most recent article is for The Reader (www.thereader.com) and it looks at South O through the prism of two young people interviewed by playwrights for the project. The second article looks at South O through the lens of three older people interviewed by playwrights for the same project. Together, my articles and participants’ stores provide a fair approximation of what makes South O, well, South O. Or in the vernacular (think South Side Chicago), Sou’d O.

South Omaha stories on tap for free PlayFest show

Great Plains Theatre Conference’s Neighborhood Tapestries returns to south side

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the May 2015 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Perhaps more than any geographic quadrant of the city, South Omaha owns the richest legacy as a livestock-meatpacking industry hub and historic home to new arrivals fixated on the American Dream.

Everyone with South O ties has a story. When some playwrights sat down to interview four such folks, tales flowed. Using the subjects’ own words and drawing from research, the playwrights, together with New York director Josh Hecht, have crafted a night of theater for this year’s Great Plains Theatre Conference’s Neighborhood Tapestries.

Omaha’s M. Michele Phillips directs this collaborative patchwork of South Omaha Stories. The 7:30 p.m. show May 27 at the Livestock Exchange Building ballroom is part of GPTC’s free PlayFest slate celebrating different facets of Neb. history and culture. In the case of South O, each generation has distinct experiences but recurring themes of diversity and aspiration appear across eras.

Lucy Aguilar and Batula Hilowle are part of recent migration waves to bring immigrants and refugees here. Aguilar came as a child from Mexico with her undocumented mother and siblings in pursuit of a better life. Hilowle and her siblings were born and raised in a Kenya refugee camp. They relocated here with their Somali mother via humanitarian sponsors. In America, Batula and her family enjoy new found safety and stability.

Aguilar, 20, is a South High graduate attending the University of Nebraska at Omaha. GPTC associate artistic director and veteran Omaha playwright Scott Working interviewed her. Hilowle, 19, is a senior at South weighing her college options. Harlem playwright Kia Corthron interviewed her.

A Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) work permit recipient, Aguilar is tired of living with a conditional status hanging over head. She feels she and fellow Dreamers should be treated as full citizens. State law has made it illegal for Dreamers to obtain drivers licenses.

“I’m here just like everybody else trying to make something out of my life, trying to accomplish goals, in my case trying to open a business,” and be successful in that,” Aguilar says.

She’s active in Young Nebraskans for Action that advocates restrictions be lifted for Dreamers. She follows her heart in social justice matters.

“Community service is something I’m really passionate about.”

She embraces South O as a landing spot for many peoples.

“There’s so much diversity and nobody has a problem with it.”

Hilowle appreciates the diversity, too.

“You see Africans like me, you see African Americans,, Asians, Latinos, whites all together. It’s something you don’t see when you go west.”

Both young women find it a friendly environment.

“It’s a very open, helpful community,” Aguilar says. “There are so many organizations that advocate to help people. If I’m having difficulties at home or school or work, I know I’ll have backup. I like that.”

“It’s definitely warm and welcoming,” Hilowle says. “It feels like we’re family. There’s no room for hate.”

Hilowle says playwright Kia Corthon was particularly curious about the transition from living in a refuge camp to living in America.

“She wanted to know what was different and what was familiar. I can tell you there was plenty of differences.”

Hilowle has found most people receptive to her story of struggle in Africa and somewhat surprised by her gratitude for the experience.

“Rather than try to make fun of me I think they want to get to know me. I’m not ashamed to say I grew up in a refugee camp or that we didn’t have our own place. It made me better, it made me who I am today. Being in America won’t change who I am. My kids are going to be just like me because I am just like my mom.”

She says the same fierce determination that drove her mother to save the family from war in Somalia is in her.

About the vast differences between life there and here, she says, “Sometimes different isn’t so bad.” She welcomes opportunities “to share something about where I come from or about my religion (Muslim) and why I cover my body with so many clothes.”

Aguilar, a business major seeking to open a South O juice shop, likes that her and Hilowle’s stories will be featured in the same program.

“We have very different backgrounds but I’m pretty sure our future goals are the same. We’re very motivated about what we want to do.”

Similar to Lucy, Batula likes helping people. She’s planning a pre-med track in college.

The young women think it’s important their stories will be presented alongside those of much older residents with a longer perspective.

Virgil Armendariz, 68, who wrote his own story, can attest South O has long been a melting pot. He recalls as a youth the international flavors and aromas coming from homes of different ethnicities he delivered papers to and his learning to say “collect” in several languages.

“You could travel the world by walking down 36th street on Sunday afternoon. From Q Street to just past Harrison you could smell those dinners cooking. The Irish lived up around Q Street, Czechs, Poles, and Lithuanians were mixed along the way. Then Bohemians’ with a scattering of Mexicans.”

He remembers the stockyards and Big Four packing plants and all the ancillary businesses that dominated a square mile right in the heart of the community. The stink of animal refuse permeating the Magic City was called the Smell of Money. Rough trade bars and whorehouses served a sea of men. The sheer volume of livestock meant cows and pigs occasionally broke loose to cause havoc. He recalls unionized packers striking for better wages and safer conditions.

Joseph Ramirez, 89, worked at Armour and Co. 15 years. He became a local union leader there and that work led him into a human services career. New York playwright Michael Garces interviewed Ramirez.

Ramirez and Armendariz both faced discrimination. They dealt with bias by either confronting it or shrugging it off. Both men found pathways to better themselves – Ramirez as a company man and Armendariz as an entrepreneur.

While their parents came from Mexico, South Omaha Stories participant, Dorothy Patach, 91, traces her ancestry to the former Czechoslovakia region. Like her contemporaries of a certain age, she recalls South O as a once booming place, then declining with the closure of the Big Four plants, before its redevelopment and immigrant-led business revival the last few decades.

Patach says people of varied backgrounds generally found ways to co-exist though she acknowledges illegal aliens were not always welcome.

New York playwright Ruth Margraff interviewed her.

She and the men agree what united people was a shared desire to get ahead. How families and individuals went about it differed, but hard work was the common denominator.

Scott Working says the details in the South O stories are where universal truths lay.

“It is in the specifics we recognize ourselves, our parents, our grandparents,” he says, “and we see they have similar dreams that we share. It’s a great experience.”

He says the district’s tradition of diversity “has kept it such a vibrant place.” He suspects the show will be “a reaffirmation for the people that live there and maybe an introduction to people from West Omaha or North Omaha.” He adds, “My hope is it will make people curious about where they’re from, too. It’s kind of what theater does – it gives us a connection to humanity and tells us stories we find value in and maybe we learn something and feel something.”

The Livestock Exchange Building is at 4920 South 30th Street.

Next year’s Neighborhood Tapestries event returns to North Omaha.

For PlayFest and conference details, visit http://www.mccneb.edu/gptc.

South Omaha stories to be basis for new theater piece at Great Plains Theatre Conference

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

Historically, South Omaha is a melting pot where newcomers settle to claim a stake of the American Dream.

This hurly burly area’s blue-collar labor force was once largely Eastern European. The rich commerce of packing plants and stockyards filled brothels, bars and boardinghouses. The local economy flourished until the plants closed and the yards dwindled. Old-line residents and businesses moved out or died off. New arrivals from Mexico, Central America, South America and Africa have spurred a new boon. Repurposed industrial sites serve today’s community needs.

As a microcosm of the urban American experience it’s a ready-made tableaux for dramatists to explore. That’s what a stage director and playwrights will do in a Metropolitan Community College-Great Plains Theatre Conference project. The artists will interview residents to cultivate anecdotes. That material will inform short plays the artists develop for performance at the GPTC PlayFest’s community-based South Omaha Neighborhood Tapestries event in May.

Director Josh Hecht and two playwrights, Kia Corthron and Ruth Margraff, will discuss their process and preview what audiences can expect at a free Writing Workshop on Saturday, January 24 at 3 p.m. in MCC’s South Campus (24th and Q) Connector Building.

Participants Virgil Armendariz and Joseph Ramirez hail from Mexican immigrant clans that settled here when Hispanics were so few Armendariz says practically everybody knew each other. Their presence grew thanks to a few large families. Similarly, the Emma Early Bryant family grew a small but strong African-American enclave.

Each ethnic group “built their own little communities,” says Armendariz, who left school to join the Navy before working construction. “There were communities of Polish, Mexicans, Bohemians, Lithuanians, Italians, Irish. Those neighborhoods were like family and became kind of territorial. But it was interesting to see how they blended together because they all shared one thing – how hard they worked to make life better for themselves and their families. I still see that even now. A lot of people in South Omaha have inherited that entrepreneurial energy and inner strength. I feel like the blood, sweat and tears of generations of immigrants is in the soil of South Omaha.”

Armendariz, whose grandmother escaped the Mexican revolution and opened a popular pool hall here, became an entrepreneur himself. He says biases toward minorities and newcomers can’t be denied “but again there’s a common denominator everybody understands and that is people come here to build a future for their families, and that we can’t escape, no matter how invasive it might seem.”

He says recent immigrants and refugees practice more cultural traditions than he knew growing up. He and his wife, long active in the South Omaha Business Association, enjoy connecting to their own heritage through the Xiotal Ballet Folklorico troupe they support.

“These talented people present beautiful, colorful dance and music. When you put that face on the immigrant you see they are a rich part of our American past and a big contributor to our American future.”

Ramirez, whose parents fled the Cristero Revolt in Mexico, says he and his wife faced discrimination as a young working-class couple integrating an all-white neighborhood. But overall they found much opportunity. He became a bilingual notary public and union official while working at Armour and Co. He later served roles with the Urban League of Nebraska and the City of Omaha and directed the Chicano Awareness Center (now Latino Center of the Midlands). His activist-advocacy work included getting more construction contracts for minorities and summer jobs for youths. The devout Catholic lobbied the Omaha Archdiocese to offer its first Spanish-speaking Mass.

He’s still bullish about South Omaha, saying, “It’s a good place to live.”

Dorothy Patach came up in a white-collar middle-class Bohemian family, graduated South High, then college, and went on to a long career as a nursing care professional and educator. Later, she became Spring Lake Neighborhood Association president and activist, helping raise funds for Omaha’s first graffiti abatement wagon and filling in ravines used as dumping grounds. She says the South O neighborhood she lived in for seven decades was a mix of ethnicities and religions that found ways to coexist.

“Basically we lived by the Golden Rule – do unto others as you want them to do unto you – and we had no problems.”

She, too, is proud of her South O legacy and eager to share its rich history with artists and audiences.

MCC Theatre Program Coordinator Scott Working says, “The specifics of people’s lives can be universal and resonate with a wide audience. The South Omaha stories I’ve heard so far have been wonderful, and I can’t wait to help share them.”

Josh Hecht finds it fascinating South O’s “weathered the rise and fall of various industries” and absorbed “waves of different demographic populations.” “In both of these ways” he says, “the neighborhood seems archetypally American.” Hecht and Co. are working with local historian Gary Kastrick to mine more tidbits.

Hecht conceived the project when local residents put on “a kind of variety show ” for he and other visiting artists at South High in 2013.

“They performed everything from spoken word to dance to storytelling. They told stories about their lives and it was very clear how important it was for the community to share these stories with us.”

Hecht says he began “thinking of an interactive way where they share their lives and stories with us and we transform them into pieces of theater that we then reflect back to them.”

Working says, “This project will be a deeper exploration and more intimate exchange between members of the community and dramatic artists” than previous Tapestries.

The production is aptly slated for the Stockyards Exchange Building, the last existing remnant of South O’s vast packing-livestock empire.

Nebraska’s Changing Face; UNO’s Changing Face

I wrote the following feature and sidebar exploring some trends about the changing face of Neb. and the University of Nebraska at Omaha, my alma mater. Slowly but surely the state and some of its institutions are becoming more diverse. Some of the changes can be readily seen already, others not so much, but in a few decades they will be more obvious. It’s a healthy thing that’s happening, though diversity is still taking far too long to be fully felt and lived and embraced in all quarters, but that’s for another story.

Nebraska’s Changing Face

©by Leo Adam Biga

Nebraska’s “Plain Jane” sameness has long extended to its racial makeup. Diversity hasn’t held much truck here. Even when the foreign-born population was at its peak in the state’s first half century, the newcomers were predominantly of European ancestry.

An African-American migration from the Deep South to Omaha in the early 1900s established the city’s black base. Until a new immigration wave in the 1990s brought an influx of Africans and Latinos-Hispanics to greater Neb., the composite face of this Great Plains state was decidedly monotone.

The perception of Flyover Country as a bastion of white farmers has never been completely accurate. The state’s two largest metropolitan areas, for example, have always boasted some heterogeneity. Urban areas like Omaha and urban institutions such as the University of Nebraska at Omaha express more racial-ethnic diversity because of longstanding minority settlement patterns and the university drawing heavily from the metro.

But it is true Neb.’s minority population has always been among the nation’s smallest, which only supported the stereotype.

Finally, though, its minority numbers are going up and its diversity broadening.

Still, if Nebraskans posed for a group portrait as recently as 1980 more than 9 of every 10 would have beeb white. Only 6 percent identified as African-Americans, Latino-Hispanics, Native Americans or Asians.

The lack of diversity extended virtually everywhere. The largest minority group then, blacks, was highly concentrated in Omaha. Despite slow, steady gains blacks still account for only 13 percent of the city’s population and 4 percent of the state’s population.

But as recently announced by UNO researchers, Neb. is changing and with it the face of the state. A group picture taken today would reveal a noticeable difference compared to a quarter century ago, with whites now accounting for 8 of every 10 residents. Indeed, the state’s minority population has more than doubled the past four decades, with by far the largest increase among Latinos-Hispanics, who now comprise the largest minority segment. Latinos-Hispanics are on a linear growth trajectory. They tend to be young and their women of childbearing age.

Minority growth has been even greater in select communities, such as Lexington, where meat processing attracted newcomers.

Celebrated native son filmmaker Alexander Payne’s new movie “Nebraska” – set and shot primarily in the northeast part of the state – accurately portrays a slice of Neb.’s past and present through a large ensemble of characters, all of whom but two are white. The exceptions are both Hispanic. The Oscar-winning writer-director may next make a partly Spanish-language feature about the impact of the immigrant population on Neb.’s towns and cities.

New UNO Center for Public Affairs Research projections posit that by 2050 the state’s portrait will dramatically change as a result of major demographic trends well under way. Within four decades minorities will account for about 40 percent of the entire population. Nearly a quarter of the projected 2050 population of 2.2 million, or some 500,000, will be Latino-Hispanic.

It’s a sea change for a state whose diversity was traditionally confined to a few enclaves of color. Immigration, migration and natural causes are driving this new minority surge.

Everything is relative though. So while CPAR Research Coordinator David Drzod says, “Our diversity will increase,” he adds, “Neb. is one of the less diverse places countrywide and other states are going to become more diverse as well.”

Still, the snapshot of Neb. is changing due to real demographic shifts with significant longterm consequences. Just as the majority white base is holding static or declining, non-whites are proliferating. The results can be seen in the ever more diverse profiles of some communities, neighborhoods, schools and other settings.

Thus, for the first time in Neb. diversity is becoming more lived reality than aspirational goal.

Economic conditions were the main driver for the sharp rise in Latinos-Hispanics migrating here. Plentiful jobs, a low cost of living, coupled with aggressive industry recruitment, lured people to move here from places with comparatively weak economies, high cost of living and job shortages. Neb. grew its Latino-Hispanic base from points of origin in California, Texas. Mexico, Central America and South America, The state also saw its African and Asian populations increase as refugees from Sudan and Bhutan, for example, resettled here.

Drozd says, “People are not coming as directly for new jobs like in the ’90s when the meat processors were expanding and recruiting. We expect to see some regional migration that Neb. has typically seen from smaller locations to more urban locations that tend to have a diverse pool of job opportunities within various industries.”

While migration has slowed from its peak waves it’s expected to continue in fits and starts. Migration, researchers agree is “a wildcard” that can’t be accurately forecast, but Office of Latino and Latin American Studies Research Associate Lissette Aliaga Linares notes an uptick in Latinos-Hispanics from Arizona, which OLLAS Director Lourdes Gouvia attributes to that state’s anti-immigrant policies.

Drozd says Neb.’s minority experience is consistent with some surrounding states and inconsistent with others.

“We are typical of the Great Plains in that we tend to suffer from outmigration especially of young college-aged whites, which is counteracted by in-migration and increase in the minority population groups. On the other hand Neb. is unique in that we are growing faster in some of our metropolitan areas and not holding our population as well as some of the more rural areas.”

The emergence of more minorities is perhaps most visible in urban inner city public schools, where student enrollment naturally reflects the heavily minority communities these schools serve. Minority enrollment in the Omaha Public Schools stands at 68 percent.

“The diversity of UNO will continue to grow and one only has to look at the demographics in the metro area to understand that traditional middle school and high school students will increasingly be students of color,” says UNO Senior Vice Chancellor for Academic and Student Affairs B.J. Reed.

Some outstate school districts are now majority Latino-Hispanic.

The impact of diversity in this small population state that suffers from brain drain cannot be overstated.

“There’s a large part of Neb. that would be having population decline if it were not for minority growth,” says Drozd. “There’s all sorts of implications with respect to aging, the workforce, health care, education. From a gerontology standpoint you have the possibility of seeing a younger, more diverse working-age population caring for a predominantly white non-Hispanic aging population and will there be any issues associated there. With programs like Social Security you’re going to be relying more and more on an immigrant population to support payments for predominantly white people collecting from the program. So there are potentials for tension there and of course political ramifications and all sorts of factors.”

Gouveia, a sociology professor, reminds that “Latinos are going to imitate some trends of the larger population the more urban and educated they become,” adding. “The more women are able to work outside the home fertility rates will drop and the population will begin to age. It’s the life cycle.”

As minorities grow they become a larger sector of the tax and voting base that elected officials and prospective candidates must recognize.

Drozd says communities must adapt, whether offering English-as-a-Second Language programs or multicultural competency classes, in order to best serve minorities and their particular needs.

As more minorities graduate high school educators and employers hope that many of these college-bound grads and working-age young adults will attend school and find jobs in-state.

“As people have become upwardly mobile in Neb.’s past that has led to outmigration out of the state,” says Drozd. “It’s going to be a very policy relevant factor because people born in the early ’90s are now hitting age 18. Even if they choose a Neb. college where are they going to go to work? Will there be jobs and associated positions for them here in the state or will they go out of state?”

Just as preparing students to succeed in school is critical, so is preparing a workforce for today’s service and skilled jobs.

“Let’s make no mistake about this, without immigration Nebraskans may have to rethink how they are going to have a viable economy that produces not only jobs but payrolls that produce taxes from which an aging population will benefit greatly,” says Gouveia. “Without this population there won’t be services this Boomer population and this aspiring mini-global city of Omaha depends on. These are increasingly service economies and that means it’s very important for the economy to increasingly be based on higher pay jobs likely to grow, such as information technology or biotechnology.

“That also means educational institutions need to be able to truly know how to train this generation of children of immigrants. The children may not be immigrants themselves but a large number have immigrant parents who endured very poor, disadvantageous conditions that tend to disadvantage the educational achievement of their children. We have to have multidimensional. multidisciplinary perspectives to understand who this population is. And that goes to our research also.”

She believes minorities will succeed to the extent opportunities allow.

“We haven’t addressed the serious barriers to education that would guarantee that new face of America and of Neb. becomes a face with equal opportunities to participate in the prosperity all of us will want to share.” She says if barriers to upward mobility aren’t removed “it may prevent Neb. from truly harnessing what we call this demographic bonus that’s been gifted to this state. A state that was losing population were it not for minority growth and international migration would be in serious trouble today to have a viable economy and future.”

Daniel J. Shipp, UNO associate vice chancellor for student affairs, says schools must find ways to support minority students.

“When combined with the typical struggles of new college students the demographics of race-ethnicity will create even more difficult challenges in both access to and success in college. Not only must we continue to open our doors wider to traditionally under-served student populations but once on campus it is critical for all of us to see their success as a top institutional and community priority.”

UNO Associate Vice Chancellor for Academic and Student Affairs Pelema Morrice urges educators and employers to appreciate diversity’s many forms.

“We always focus on racial-ethnic diversity but I think intellectual diversity, geographic diversity, cultural diversity, all those different forms of diversity, really add a lot of value to everyone’s experience. There’s plenty of evidence that the more diverse environment we’re in the more we all have opportunities to learn from each other.

“So I think it’s incredibly important for an institution to be a welcoming and diverse environment where folks can learn from each other at a higher level. I think that adds to the educational experience and it provides students with really good training to go out and be productive citizens and to be successful in the workplace.”

Diversity is also the way of this flatter, interconnected world.

Reed from UNO’s Academic and Student Affairs office, says “Our students will grow up in a much more global environment requiring exposure to difference cultures and different experiences.”

Where diversity often must be programmed, Gouveia is heartened by students’ inherent embrace of it. “About this new Neb. mosaic, one thing I’m particularly hopeful about is the younger generation. I love our new students. From any background they are so much more prepared and so much more ahead of where we are as professors or department chairs or deans in terms of knowing how to do diversity. We are the ones who are often behind them.”

As Neb. becomes more multi-hued, UNO’s Morrice says representative stakeholders should discuss what diversity holds for the state.

“With these new demographics coming forward it means our student base will obviously be more diverse than it is now and that means the outcomes will be more diverse and so we’ll see more diverse workplaces and communities within the state. We’re just a piece of that puzzle but I think it’s a good collective conversation for everyone to have as the state continues to grow and it becomes clear that there will be different faces at the table.”

UNO’s Changing Face

©by Leo Adam Biga

The same demographic trends on pace to make the United States a minority majority population by 2050 and making Neb. a more racially-ethnically diverse place in the second decade of the new millennium, are increasingly being expressed at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

Roughly a quarter of UNO’s 2013-2014 freshman class is minority and just under 20 percent of the school’s entire undergraduate enrollment is minority. Both are record marks for the school. In 2000, for example, UNO’s minority enrollment stood at 9 percent. The minority numbers are even greater among graduate students.

The 11 percent rise in UNO minority enrollment from 2000 until now reflects in large measure the Latino-Hispanic boom that happened in-state from 1980 to 2010, when that segment increased from about 37,000 to 167,000. The Latino-Hispanic population is expected to add another 370,000 residents by 2050, according to UNO’s Center for Public Affairs Research.

As a public institution with a state-wide reach, UNO’s a model for the changing face of Neb. Drawing principally from the Omaha metropolitan area, which as the state’s largest urban center has always been Neb.’s most racially-ethnically diverse spot, UNO is, as expected, one of the most diverse campuses in the University of Nebraska system.

At the University of Nebraska-Kearney minority undergraduate enrollment has nearly doubled since 1995. Today, nearly a quarter of its students are non-white or non-resident alien. Meanwhile, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln reports the most diverse student body in its history. UNL’s 2,328 minority undergrads are about 12 percent of the undergraduate total, a 9 percent increase just from last year. Just as at UNO, the largest minority gains at each school are in the Latino-Hispanic and international students categories,

As minorities comprise a growing segment of the state’s mainstream and of its public schools’ enrollment, institutions are tasked with incorporating these populations and responding to their needs.

“The good news for Omaha is that UNO has a proud tradition of supporting minority students through various educational equity and learning community investments such as Goodrich, Project Achieve and the newer Thompson Learning Community,” says UNO Associate Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Daniel J. Shipp. “These programs provide student participants with a network of caring and concerned faculty, staff and peer mentors that help students to succeed and thrive in college. Moving forward, I expect we will continue to build on our national reputation for attracting and supporting the growing numbers of minority students and their families in the Omaha area and beyond.”

“Minority students are an important population but they are only one of an increasing mosaic of diversity at UNO, whether they are military, first generation, students of color or adult learners or transfer students,” says UNO Senior Vice Chancellor for Academic and Student Affairs B.J. Reed. “We are working every day to ensure that these students feel welcome at UNO and have the type of support services and environment that will make them want to be want to be here and to be successful. We do this for all our special populations of students. We have programs and learning communities as well as staff specifically directed at helping ease their transition to UNO and success in their academic goals.”

Reed says hiring faculty and staff who reflect the changing face of UNO “is a top priority,” adding, “We have made important strides in diversifying our staff but we lag behind where we want to be here and also with recruiting and retaining a more diverse faculty. We are working on reviewing existing policies and procedures and looking at incentives and support efforts to increase the diversity of faculty and staff to reflect the changing demographics of our student body.”

There’s wide agreement that diversity is a net sum experience for all involved.

“The benefits are substantial,” Reed says. “The workplace is becoming increasingly diverse and employers need and want an increasingly diverse group of employees. We cannot underestimate the shift occurring here. We need to provide a strong educational workforce for employers and UNO must be positioned to do that effectively.”

Office of Latino and Latin American Studies Director and Sociology Professor Lourdes Gouveia agrees that educators at UNO and elsewhere must increasingly consider diversity and its impact.

“We have to educate our professionals and student populations in ways that allow them to be skilled about global issues and diversity and to have multicultural competencies as the world is very connected,” she says. “But also we need to address structural barriers that may prevent Neb. from truly harnessing what we call this demographic bonus that has been gifted to this state. A state that was losing population if not for minority growth and international migration would be in serious trouble today to have a viable economy and a future.”

Born again ex-gangbanger and pugilist, now minister, Servando Perales makes Victory Boxing Club his mission church for saving youth from the streets

It’s doubtful that another amateur boxing club has received as much ink and video coverage in the short time Victory Boxing has since starting about a decade ago. The magnet for the attraction is founder Servando Perales, whose personal story of transformation and redemption and unbridled passion for helping at-risk youth are the driving forces behind his boxing gym. The gym is really his mission church and sanctuary for getting kids out of the gang life that consumed him and landed him in prison. That’s where his own turnaround began. If you’re a boxing fan, then check out the boxing category on the right — I have many stories there about pro and amateur fighting, past and present.

Born again ex-gangbanger and pugilist, now minister, Servando Perales, makes Victory Boxing Club his mission church for saving youth from the streets

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Rev. Servando Perales and his faith-based Victory Boxing Club at 3009 R Streets is a story of redemption laced with irony. He’s eager to share the story at its April 25 grand opening, when from 1 to 3 p.m. the public’s invited to experience the program USA Boxing magazine recently named national club of the month.

In terms of redemption, consider how this one-time boxer and gang-banger from south Omaha survived The Life of a drug dealer-abuser only to undergo a profound transformation in prison. Behind bars Perales found God with the help of fellow con Frankie Granados, an old friend he’d run with on the outside. Granados already had his own born again experience in the pen and he worked on Servando to take the plunge, too. It took time but Perales finally “surrendered.”

On the curious side, consider that Victory head coach John Determan is both a former corrections officer and cop. He donated Victory’s first ring. He appreciates the oddity of a gringo badge and a Latino fist teaming up.

“I knew him as a bad guy when I was a cop,” said Determan, a former Mills County (Iowa) deputy. “That’s what’s cool, you know — bad guy-cop coming together to do something like this,” said Determan, whose son Johnny, a nationally-rated 119-pound amateur, and daughter Jessica, a former amateur world champ, train there.

Beyond their lawman-outlaw roles, Determan and Perales knew one another from boxing circles. They even traded blows in the ring when the older Determan was a journeyman pro fighter and Perales a feisty young amateur. They dispute who got the better of each other in those long ago sparring sessions.

Victory Boxing partnered with Jimmy John’s to purchase their gym at 3009 S. R. Street

Fighting’s not all they share in common. Both are devout Christians. Determan ran a faith-based boxing club in Glenwood, Iowa. The evangelists boldly fly their Christian colors at Victory, whose “t” is an oversized cross with a pair of boxing gloves hanging from it. A wooden cross adorns a wall inside, where Perales ends pep talks with, ‘You guys ready for the risen Lord? Alright, amen.’” The pair hold weekly Bible studies on Thursdays. All part of the signs and wonders that distinguish Victory from other gyms, where Christ is more apt to be an expletive than a prayer.

“The thing that separates us from all the other ones is that we’re Christ-centered,” said Perales. “We do not waver our faith, our values, and we stand firm on who can change a person’s life, and it’s Jesus Christ. That’s my strong belief and that’s what sets us apart. That’s why you see 30 kids in here. It’s not because we’re the best coaches or because we have the best fighters, it’s because they sense a presence of God in this place. I actually believe that.

“We acknowledge that God is the only one that can change circumstances and change people. If He did it for me he can do it for anybody.”

“It’s great when we have our Bible studies,” Determan said. “They’re really hot topics where we talk to the kids about things they might struggle with and they’re hearing it from two perspectives — the gang member and the cop. And that’s one of our testimonies to our kids — that it doesn’t matter who anybody is, skin color, background or any of that, you can come together.”

Perales, a father of five, said the fact he and Determan can speak with first-hand authority about both sides of the law, gives them an edge in dealing with kids who may have problems at home or school and be veering off track.

“They can’t pull a fast one over on either one of us,” said Perales, whose gym serves members ages 10 and up. The coaches field calls from kids at all hours.

The cop connection doesn’t end there. Retired Omaha deputy police chief Mark Martinez believes enough in what Perales does that he volunteers at the gym.

“Servando knows the challenges some young people face, having traveled that road himself, so he has an incredible ability to relate. His story is real and he has much credibility with youngsters. Consequently, he’s very effective, especially in helping troubled youth be positive and productive citizens,” said Martinez.

When storm damage made Victory’s previous site uninhabitable last summer, the gym was homeless. Martinez told a friend about it. Perales and the benefactor met and Victory soon had a spacious new home in the former Woodson Center.

“Actually, we wouldn’t be in this building had it not been for (ex) deputy chief Martinez. He’s the one who helped us get in this building by introducing us to a gentleman that actually put $65,000 up for this building,” said Perales.

A Weed and Seed grant purchased a new ring. The minister sees Victory as a partner with law enforcement to provide safe havens and activities. The gym hosts all-night lock-ins, takes kids camping and has them participate in community events, from parades to Easter egg hunts. Cops are frequent visitors. Some come to train, others just to kick it with kids. “We have a lot of cops that are friends,” Perales said. “Law enforcement is really deep out here. They’re strong. The gang unit, I know those guys personally. I grew up with them. We’re working, we’re doing everything in our power to keep the streets of south Omaha safe.”

It’s only logical the local Latino Peace Officers Association (LPOA) is a major backer of the gym, given its makeup and location in Hispanic-rich south Omaha and the club’s predominantly Hispanic members. But what you wouldn’t expect is that past LPOA president Virgil Patlan, the man who arrested Perales in ‘96 in a bust that sent Perales away for 18-months, ardently champions Victory. Once on opposite sides of the law, Patlan and Perales are friends and admirers today.

Perales attributes this turn of events to divine whimsy. “Yeah, God has a sense of humor, man — He put an ex-gangster and a cop together, and all for the glory of God,” said Perales, whose tats are remnants of the old life he left behind.

Patlan admits being dubious of Servando’s change of heart until hearing him preach and talking with him. “I was real skeptical at first because you hear this all the time about cons,” said Patlan. “It took a lot of ice-breaking but we became good friends. I knew he had a heart to help young people. I knew he didn’t want them to go through what he went through. I know if someone’s trying to pull the wool over my eyes — he’s not. He’s authentic, he’s genuine.”

An Omaha Police Department retiree, Patlan is an active community advocate and neighborhood association volunteer. He and Perales collaborate on projects.

“I think that’s where the trust and the respect came for each other,” said Patlan, “and we’ve just kept doing programs for the neighborhood.”

A program they formed called This is Your Neighborhood makes presentations to school-age kids about the evils of gang affiliation-activity and the importance of staying in school. By his late teens Perales was incorrigible and got expelled from South High. His troubles escalated after that. It’s why Victory requires members abide by a strict code of conduct that includes maintaining good grades and refraining from swearing, gang signs and any disrespectful behavior.

Since Victory’s inception Patlan’s helped with donations. He and his wife are planning a “fun run” to raise funds for the program’s operating expenses. Patlan and Perales share so many values they don’t dwell on the divergent paths that led them to the close bond they enjoy today.

“Now I don’t even think of it. It’s natural. We call each other brother,” said Patlan.