Archive

Tech maven LaShonna Dorsey pushes past stereotypes

Tech maven pushes past stereotypes

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the December 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

LaShonna Dorsey, 38, busts stereotypes. Start with this sunny disruptor launching and selling a successful technology organization in her hometown.

As an African-American entrepreneur, she bridged the digital divide with Interface Web School. Though now part of the AIM Institute, she still heads the coding school that’s won her and its work much recognition. Her AIM title is Vice President, Tech Education.

She’s bypassed the Omaha ceiling for young black professionals that finds many leaving for better advancement opportunities elsewhere.

She’s defied expectations by going public, rather than remain silent, about an assault she endured.

For this superstar doer who serves on multiple boards, AIM’s acquisition of Interface was strategic.

“Interface had really reached a point of capacity,” said Dorsey. “We were growing, which was great, but I just knew I couldn’t take on more classes without having more infrastructure and all that. AIM has the infrastructure, they’ve got the space, they’ve got human resources, accounting, marketing departments.”

AIM Interface solidifies and expands partnerships.

“We had really good relationships with the Nebraska Department of Labor and Heartland Workforce Solutions and still maintain those, but it’s a lot easier for us to partner with companies and other organizations because we’re AIM now.

“It fit right with where AIM and Interface wanted to go. They have the youth education side and professional development, but they didn’t have adult tech training. The cool thing is that Interface LLC was a for-profit and now we’re a program within a nonprofit and so we get to take advantage of having that 501 designation.”

Building Interface fulfilled a dream.

“I really thought I was a starter, and so it was good to see something through from idea to completion in a major way.”

She frequently shares her start-up story, warts and all.

“I felt like especially in the early days of Interface I often had to act like I had it altogether all the time because I was selling it, too. It’s kind of a challenging position to be in because you can’t be truly authentic.

“I was really grateful to have good friends and a really strong support system. That made a huge difference.”

She especially enjoys sharing her story with women.

“Women that have done a ton in their career appreciate how difficult it is to do something like this. Women just getting started are like, ‘How did you even do that?’ We have real conversations about what it’s like and the pitfalls – but also the rewards. Being in the middle myself, I am kind of still navigating that.

“I do feel I have a lot of value to add and information to share if people are ready to hear it. I tell people it wasn’t easy all the time, but the thing that kept me moving forward was that it was so rewarding. I have so many graduate stories of people whose lives were changed because of what they learned. It helped them get better jobs and buy homes. They’re still reaping the benefits. It’s still rippling. The culture of Interface is like that.”

She readily accepts being a role model and mentor to young black women.

Growing up in a single-parent family, Dorsey learned self-reliance skills. As a bright Goodrich scholar at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, she became a self-motivated high achiever. Early in her career, she proved a project management whiz.

“I like to just figure my way forward. I like problem solving. When things get a little too simple, then that is hard for me. Then I’m like, ‘Okay, what else can we do here?’ I’m not afraid of conflict, so I do lean into it, and I encourage people who work for me to do the same. If you really want to get the thing you want, you have to work through the hard stuff, too.”

Omaha’s limited horizons saw Dorsey leave in her 20s.

“But I came back. The thing that’s really tough here is that as you move up in your career, the leadership gets more white. Working in tech, you’re with a lot of white professionals and when I lived in west Omaha I’d go home, where it was all white, and I felt I had no community. It’s unfortunate and it felt uncomfortable.

“Living in a diverse community is important for me.”

Workplace inclusion requires more than new hires.

“You can hire a bunch of black and whatever programmers but that is not going to change the culture of organizations who might not be ready for it. You have to give people a space where they’re comfortable being themselves and not feeling like they have to fully assimilate in order to fit in.

“I cannot wait until we don’t have to have this conversation anymore and where it’s not special that I’m a black woman in tech. But it matters a lot to people and I have to talk about it.”

She feels she’s reached a personal breakthrough by reclaiming her given name, LaShonna, in place of Shonna and letting her hair go natural.

“Now, I feel like I can be more of myself.”

Dorsey embraces the new diversity in revitalized northeast Omaha, where African-American culture is being discovered by white millennials.

“Whenever you can create opportunities for people to have those experiences with people they don’t interact with on a daily basis, you start to change the narrative. That’s the only way were going to see change.”

Mindset to her is critical to create the transformation she and others hope to see there.

“I think we’re still many years out from seeing the fruits of it. There’s a lot of work to do because we can’t deny the fact poverty is the highest in those zip codes. That’s something to address and fix but people have to want it and see it even as an issue.”

She’s doing her part to equip adults with job-ready tech skills by bringing her code school to the Highlander Village purpose-built community on North 30th Street.

“Those economic improvement opportunities can make a big difference for people,” she said. “It will be awesome to see all of that come to life.”

Her career exploded two years ago, but few knew she was reeling from having barely survived an assault.

“Everything was still new at Interface and I still didn’t feel like I knew what I was doing all the time when I had this really difficult, tragic thing happen. There were many work days when I had to meet attorneys or go to court Turning those emotions on and off was really hard.”

It stemmed from someone she’d dated suddenly revealing a side he’d concealed before.

“It turned into a night where he took me from where I was without my permission. He strangled me three times, including once where I lost consciousness. He assaulted me in all sorts of ways in what was a five-hour ordeal.”

Fifteen months elapsed from when she pressed charges to her attacker’s sentencing.

“It was a really hard process. I totally understand why people don’t pursue that path because it is very difficult and as the victim you have to prove something happened. Typically, this kind of stuff happens one-on- one.”

Dorsey nearly didn’t report the incident for fear of how she’d be perceived.

“I remember thinking this is going to be so embarrassing and people are going to think I can’t do anything right. It’s irrational thinking, I know, but that was in my head. I decided to report it anyway.

“I try to do everything on my own all the time. But I did get some counseling and I did work through some of this with friends. Leaning into work helped a lot.”

Nature walks and karaoke nights helped, too.

Then she began dealing with it in public forums, including a poignant Facebook post.

“It was hard to carry around all the time. People were really supportive. They called me brave and things like that. I just felt it was relieving a burden for me.”

She posted soon after the last presidential election and urged people to walk through their fear and anger over the results as she had with her assault.

“Every time I talk about it publicly, more than one person will come up to me and say, ‘Me, too,’ or “My friend, my sister, my daughter.’ It’s so common. There’s a bunch of people who feel like they can’t talk about it, so I decided to share what happened to me.”

If nothing else, she said, her story reveals all is not what it seems on the path to success.

“People tend to look at the surface and just assume that because you’ve done a lot, it was without hardship.”

Visit Interfaceschool.com. Follow Dorsey on Facebook.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

Health and healing through culture and community

Donna Polk was raised African-American but she’s also part Native American, which is a common story. Still, she never imagined she would one day head a Native agency, but she has for decades now. The story of Natives being among us and yet unseen is also a common one. Csn Native Americans be any more invisible in this country? Were it not for the travesties of Whiteclay and Dakota Access Pipeline, where would Native voices be heard and Native faces seen? This marginalized people constituting many sovereign tribes and nations presents very real health challanges that only an organization like the Nebraska Urban Indian Health Coalition (NUIHC) can meet while still respecting Native cultural traditions. This long-standing nonproft has, until recently, been nearly invisible itself as far as the majority population is concerned because its clients are so far off the mainstream radar. But with the Coalition now in the news for plans to establish a new campus, director Donna Polk and programs director Nicole Tamayo are out front and center taking about Native needs and how the organization responds to them. Read my story about NUIHC in the November 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Health and healing through culture and community

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the November 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Donna Polk and Nicole Tamayo decry developer-led gentrification driving their Nebraska Urban Indian Health Coalition out of downtown Omaha.

Headquartered at 2240 Landon Court on 24th Street, between Farnam and Leavenworth, the nonprofit feels the squeeze enough from encroaching development that it plans moving to South Omaha to be closer to its Native base and to have larger facilities.

“We intend to move because we’ve outgrown this facility and we no longer fit into the demographics of this area. Gentrification is chasing us out. Our target population is no longer here and we need more space,” said Polk, longtime CEO of the agency formed in 1986.

The 12,000-square foot building contains residential and outpatient treatment, youth and elders programs, communal-event rooms, all within close proximity,

“By moving into a larger building well be able to have one floor more for the community and a second floor for programming. We’re very excited about that.”

She plans a small culinary training program.

Meanwhile. she and Tamyao don’t like how rising property values and rents displace residents in a long dormant, mixed-use urban area being revitalized.

But Polk is also practical enough to work with one of those gentrifying developers, Arch Icon. For the new NUIHC site, they’ve fixed on the former South Omaha Eagles Club at 24th and N. It has more than double the square footage. Adjacent to it, she wants to build 44 low-income transitional housing units to “provide secure, sober housing for a displaced community.”

Tamayo, NUIHC Youth and Family program director, said the city’s Native community once lived near downtown but long since dispersed. Transportation’s an issue but will be less so with the move.

Both women are mixed heritage like most of their clients, “There aren’t that many pure bloods,” said Tamayo, who’s Mexican and Native. Polk is African-American and Native. The agency has an all-Native board of directors except for one member. Board and staff dislike any efforts, intentional or not, that further marginalize an already nearly invisible population. Though not widely seen – the census estimates 3,400 reside here – Natives have real lives, families, issues and needs NUIHC responds to with culturally competent programs and services.

Tamayo oversees the Soaring Over Meth and Suicide (SOMS) program that gives young people preventive tools to avoid abusing substances or doing self-harm. The mother of four brings “a lot of life experience” to the job. People close to her have committed suicide, battled drug addiction and suffered mental illness.

She sees herself in the clients she serves.

“I grew up in the area. i did the gangs and the drugs and the running around. Anything positive that I can keep my kids in and the bigger support system that I can put around them is definitely a plus.”

NUIHC provides that safety net.

“There’s not a whole lot else here. There’s no Indian (community) center. There’s nothing for the kids. The family supports for most of them are not there.”

Omaha’s lacked a full-fledged Indian center since 1995.

“We try to fill that void,” Polk said, “but our focus is heath basically.”

NUIHC accepts some clients other Indian Health Service (IHS) centers don’t.

“You have to be an enrolled member of a federally recognized tribe to be able to receive services from an IHS,” said Tamayo. “A big part of our push, especially with the Adolescent Health Project we’re part of through the Women’s Fund of Omaha, is to build bridges and fill gaps between the different services so that other organizations work better with our community.

“That way clients will have better options.”

NUIHC operates a federally qualified community health clinic in Lincoln, Neb. serving Natives and non-Natives and a free transportation service in Sioux City, Iowa.

“At our Lincoln clinic we provide healthcare services to a large population of undeserved people in Lancaster County,” Polk said. “Incidence and prevalence of chronic disease in the Native community probably puts them at greatest risk than any racial or ethnic group with diabetes, heart disease, cancer, respiratory issues. It’s horrific. It mirrors the mortality and morbidity rate of the dominant culture but the effect is more devastating because diagnosis is often in late stages.”

In Omaha, NUIHC offers mental illness counseling and drug-alcohol addiction treatment. The brick building houses 10-in-patient beds. The campus includes five transitional living units across the street owned by the Winnebago tribe and leased back to NUIHC.

“When people graduate from this (treatment) program or any program in the country, they’re eligible to go to the transitional housing.”

NUIHC’s not seen an upsurge in treatment referrals since since Whiteclay, Neb. liquor stores closed, though alcohol remains a huge problem.

The agency’s broader health focus extends to teaching young people healthy choices and life skills and providing social-recreational activities for elders.

“The programming we do, even sex education, is working with the culture, bringing back traditional values in how to conduct yourself to have high self-esteem and self-worth for making healthy choices,” Tamayo said. “In the majority of our families, the youth do start to drink, use, smoke, whatever, by 10-11 years old.

“It’s looking at underlying issues rather than just educating them about using condoms and getting tested. We have to help them change their mindset. It’s getting them to understand what’s important and how to take care of themselves. We tell them you may not be able to control the environment you’re put in or what’s going on around you, but you still have control of the choices you make going forward What you did yesterday doesn’t have to dictate what you do today. If you choose to go to school today, then that’s one step closer to doing what you need to be doing to better your life. We keep encouraging them.”

Two annual NUIHC events happen this month: Empowering Youth to Lead a Healthy Life: Native American Health Conference on November 10 and Hoops 4 Life 3-on-3 basketball tournament on November 11. Both are at NorthStar Foundation.

The organization works closely with local colleges and universities. Some Native post-secondary students mentor Native high schoolers.

“We want our kids to see that this is possible – that this is something they can get to,” Tamayo said.

NUIHC convenes an All Nations Youth Council that has a real voice in agency matters.

“For any big push we have we get input from this community, including our youth,” she said. “We don’t want to be telling them what they need to be learning and working on if they have other things going on that need to be addressed. They discusses where we’re going with programming – if we’re hitting it or missing it.”

Last summer, participants of an NUIHC-sponsored youth group made a chaperoned road trip to Chicago and Washington D.C., where they presented cultural performances featuring traditional singing and dancing.

“A lot of our kids haven’t even been past Sioux City,” she said. “It’s giving them an opportunity to understand there’s a whole world out there and it’s very possible for them to reach and go to. They enjoyed it.

“We took them around to all the museums in D.C. The one they enjoyed the most was the Holocaust Museum. A lot of people wondered if that was going to be too traumatic for them. But when we talked to the kids afterward, they’re so used to seeing things on the reservation, they’re so knowledgable historically of the things that have happened to Native Americans, that this didn’t affect them as it might a lot of others.

“Trauma is just such a part of their daily life that it takes so much for them to be impacted by the experience.”

The Omaha office just got grant a to do domestic and sexual violence counseling.

In everything NUIHC does, great emphasis is placed on observing Native traditions. It even occasionally hosts funeral services, most recently for Zachary Bearheels, the mentally ill man tasered and punched multiple times by Omaha police last June before dying in custody.

“We use a spiritual base,” Polk said. “We don’t deal with religion or denomination – we deal with spirituality. Religion is for people afraid they’re going to hell, and spirituality is for people who’ve been there.”

Every effort’s made to respect client requests.

“If you want to go to the sweat lodge or have a ceremony with a medicine man or go to a pow-wow, you can do that.”

“Definitely. our focus is healthcare, but the connection between cultural activities and being able to identify who you are with how those things affect your health has come more about,” Tamayo said. “We’re able to do that to address the health issues we’re working with.

“We work with Omaha Public Schools and their NICE (Native Indian Centered Education) program on addressing truancy. We help school officials understand sometimes Native students will miss school to participate in traditional practices.”

NUIHC works with OPS and other stakeholders on cultural sensitivity to Native mobility and family dynamics that find youth moving from place to place.

“That’s very important because we look at that as a protective factor so kids can feel good about who they are,’ said Polk.

Tamayo appreciates the autonomy she’s given.

“Donna (Polk) has faith in me that I understand our families’ needs and what services to give them. I have full permission. It’s like open-door mentoring. We have to be really connected and visible in the community. It’s a lot of hours.

“I’ve been in the community my whole life on and off and I know most of these families on an individual level, so being able to reach out and do what I need to do to help them is a plus.”

That help may include informal counseling-coaching to navigate the complexities of life off the Rez.

“We partner with and reach out to reservations because so many of our families migrate back and forth between urban settings and reservations. We want them to feel like they’re getting help with things wherever they go,” Tamayo said.

“They feel like they’re so far away from home and they don’t have a connection here,” Polk said. “We help get them more involved in the community so they can keep that cultural connection they may be missing in an urban setting.”

Polk feels NUIHC is sometimes out-of-sight, out-of-mind. Its $2.3 million budget depends on the vagaries of federal and foundation funds and grants. The low-key, low-profile agency isn’t exactly a household name.

“I don’t lament the fact the general public may not know us or what we do here because the people who need our services know we’re here. That’s what’s important to me. Nationally, people know we’re here. We get clients from as far away as Alaska who come for treatment.”

She’s gearing up to raise millions to acquire and renovate the South Omaha Eagles building. Plans to build the Eagle Heights recovery community are contingent on TIF financing and other funding sources.

“Our mission is to create a small community for the original inhabitants of this land. Almost every group has a community people identify with. We believe we can blend in with South Omaha. It offers the land, the vibrancy and a welcoming spirit. We will be able to increase our ability to elevate the health status of urban Indians by offering additional services, including Intensive outpatient, parenting, caregiver training-assistance, community health and outreach.”

Visit http://www.nuihc.com.

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

The November issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com) features my story on an old-line but still vital social action organization celebrating 90 years in Omaha.

The Urban League. The name may be familiar but the role it plays not. Since the National Urban League’s 1910 birth from the progressive social work movement, it’s used advocacy over activism to promote equality. The New York City-based NUL encouraged the creation of affiliates to serve blacks leaving the South in the Great Migration. One of its oldest continuously operating affiliates is the Urban League of Nebraska. The local non-profit started in 1927 as the Omaha Urban League and so operated until changing to Urban League of Nebraska (ULN) in 1968.

This century-plus national integrationist organization is anything but a tired old outfit living off 1950s-1960s Freedom Movement laurels. Its mission today within the ongoing movement is “to enable African-Americans to secure economic self-reliance, parity, power and civil rights.” Ditto for ULN, which marks 90 years in 2017. At various times the local office made housing, jobs and health priorities. Today, it does advocacy around juvenile justice, education and child welfare reform and is a service provider of education, youth development, employment and career services programs. It continues a long-standing scholarships program.

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the November 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The Urban League.

The name may be familiar but the role it plays not. Since the National Urban League’s 1910 birth from the progressive social work movement, it’s used advocacy over activism to promote equality. The New York City-based NUL encouraged the creation of affiliates to serve blacks leaving the South in the Great Migration. One of its oldest continuously operating affiliates is the Urban League of Nebraska. The local non-profit started in 1927 as the Omaha Urban League and so operated until changing to Urban League of Nebraska (ULN) in 1968.

This century-plus national integrationist organization is anything but a tired old outfit living off 1950s-1960s Freedom Movement laurels. Its mission today within the ongoing movement is “to enable African-Americans to secure economic self-reliance, parity, power and civil rights.” Ditto for ULN, which marks 90 years in 2017. At various times the local office made housing, jobs and health priorities. Today, it does advocacy around juvenile justice, education and child welfare reform and is a service provider of education, youth development, employment and career services programs. It continues a long-standing scholarships program.

Agency branding says ULN aspires to close “the social economic gap for African-Americans and emerging ethnic communities and disadvantaged families in the achievement of social equality and economic independence and growth.”

The emphasis on education and employment as self-determination pathways became more paramount after the Omaha World-Herald’s 2007 series documenting the city’s disproportionately impoverished African-American population. ULN became a key partner of a facilitator-catalyst for change that emerged – the Empowerment Network. In a decade of focused work, North Omaha blacks are making sharp socio-economic gains.

“It was a call to action,” current ULN president-CEO Thomas Warren said of this concerted response to tackle poverty. “This was the first time in my lifetime I’ve seen this type of grassroots mobilization. It coincided with a number of nonprofit executive directors from this community working collaboratively with one another. It also was, in my opinion, a result of strategically situated elected officials working cooperatively together with a common interest and goal – and with the support of the donor-philanthropic community.

“The United Way of the Midlands wanted their allocations aligned with community needs and priorities – and poverty emerged as a priority. Then, too, we had support from our corporate community. For the first time, there was alignment across sectors and disciplines.”

Unprecedented capital investments are helping repopulate and transform a long neglected and depressed area. Both symbolic and tangible expressions of hope are happening side by side.

“It’s the most significant investment this community’s ever experienced,” said Warren, a North O native who intersected with ULN as a youth. He said the League’s always had a strong presence there. He came to lead ULN in 2008 after 24 years with the Omaha Police Department, where he was the first black chief of police.

“I was very familiar with the organization and the importance of its work.”

He received an Urban League scholarship upon graduating Tech High School. A local UL legend, the late Charles B. Washington, was a mentor to Warren, whose wife Aileen once served as vice president of programs.

Warren concedes some may question the relevance of a traditional civil rights organization that prefers the board room and classroom to Black Lives Matter street tactics.

“When asked the relevance, I say it’s improving our community and changing lives,” he said, “We prefer to engage in action and to address issues by working within institutions to affect change. As contrasted to activism, we don’t engage much in public protests. We’re more results-oriented versus seeking attention. As a result, there may not be as much public recognition or acknowledgment of the work we do, but I can tell you we have seen the fruits of our efforts.”

“We’re an advocacy organization and we’re a services and solutions provider. We’re not trying to drum up controversy based on an issue,” said board chairman Jason Hansen, an American National Bank executive. “We talk about poverty a lot because poverty’s the powder keg for a lot of unrest.”

Impacting people where they live, Warren said, is vital if “we want to make sure the organization is vibrant, relevant, vital to ensuring this community prospers.”

“We deal with this complex social-economic condition called poverty,” he said. “I take a very realistic approach to problem-solving. My focus is on addressing the root causes, not the symptoms. That means engaging in conversations that are sometimes unpleasant.”

Warren said quantifiable differences are being made.

“Fortunately, we have seen the dial move in a significant manner relative to the metrics we measure and the issues we attempt to address. Whether disparities in employment, poverty, educational attainment, graduation rates, we’ve seen significant progress in the last 10 years. Certainly, we still have a ways to go.”

The gains may outstrip anything seen here before.

Soon after the local affiliate’s start, the Great Depression hit. The then-Omaha Urban League carried out the national charter before transitioning into a community center (housed at the Webster Exchange Building) hosting social-recreational activities as well as doing job placements. In the 1940s, the Omaha League returned to its social justice roots by addressing ever more pressing housing and job disparities. When the late Whitney Young Jr. came to head the League in 1950, he took the revitalized organization to new levels of activism before leaving in 1953. He went on to become national UL executive director, he spoke at the March on Washington and advised presidents. A mural of him is displayed in the ULN lobby.

Warren’s an admirer of Young, “the militant mediator,” whose historic civil rights work makes him the local League’s great legacy leader. In Omaha, Young worked with white allies in corporate and government circles as well as with black churches and the militant social action group the De Porres Club led by Fr. John Markoe to address discrimination. During Young’s tenure, modest inroads were made in fair hiring and housing practices.

Long after Young left, the Near North Side suffered damaging blows it’s only now recovering from. The League, along with the NAACP, 4CL, Wesley House, YMCA, Omaha OIC and other players responded to deteriorating conditions through protests and programs.

League stalwarts-community activists Dorothy Eure and Lurlene Johnson were among a group of parents whose federal lawsuit forced the Omaha Public Schools to desegregate. ULN sponsored its own community affairs television program, “Omaha Can We Do,” hosted by Warren’s mentor, Charles Washington.

Mary Thomas has worked 43 years at ULN, where she’s known as “Mrs. T.” She said Washington and another departed friend, Dorothy Eure, “really helped me along the way and guided me on some of the things I got involved in in civil rights. Thanks to them, I marched against discrimination, against police brutality, for affirmative action, for integrated schools.”

Rozalyn Bredow, ULN director of Employment and Career Services, said being an Urban Leaguer means being “involved in social programs, activism, voter rights, equal rights, women’s rights – it’s wanting to be part of the solution, the movement, whatever the movement is at the time.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, ULN changed to being a social services conduit under George Dillard.

“We called George Dillard Mr. D,” said Mrs. T. “A very good, strong man. He knew the Urban League movement well.”

She said the same way Washington and Eure schooled her in ciivl rights, Dillard and his predecessor, George Dean, taught her the Urban League movement.

“We were dealing with a multiplicity of issues at that particular time,” Dillard said, “and I imagine they’re still dealing with them now. At the time I took over, the organization had been through two or three different CEOs in about a five year period of time. That kind of turnover does not stabilize an organization. It hampers your program and mission.”

Dillard got things rolling. He formed a committee tasked with monitoring the Omaha Public Schools desegregation plan “to ensure it did not adversely affect our kids.” He implemented a black community roundtable for stakeholders “to discuss issues affecting our community.” He began a black college tour.

After his departure, ULN went through another quick succession of directors. It struggled meeting community expectations. Upon Thomas Warren’s arrival, regaining credibility and stability became his top priority. He began by reorganizing the board.

“When I started here in 2008 we had eight employees and an operating budget of $800,000, which was about $150,000 in the red,” Warren said. “Relationships had been strained with our corporate partners and with our donor-philanthropic community, including United Way. My first order of business was to restore our reputation by reestablishing relationships.”

His OPD track record helped smooth things over.

“As we were looking to get support for our programs and services, individuals were willing to listen to me. They wanted to know we would be administering quality services. They wanted to know our goals and measurable outcomes. We just rolled up our sleeves and went to work because during the recession there was a tremendous increase in demand for services. Nonprofits were struggling. But we met the challenge.

“In the first five years we doubled our staff. Tripled our budget. Currently, we manage a $3 million operating budget. We have 34 full-time employees. Another 24 part-time employees.”

Under Warren. ULN’s twice received perfect assessment scores from on-site national audits.

“It’s a standard of excellence for our adherence to best practices and compliance with the Urban League’s articles of affiliation,” he said.

Financially, the organization’s on sound footing.

“We’ve done a really admirable job of diversifying our revenue stream. More than 85 percent of our revenue comes from sources other than federal and state grants,” said board chair Jason Hansen. “We have a cash reserve exceeding what the organization’s entire budget was in 2008. It’s really a testament to strong fiscal management – and donors want to see that.”

“It was very important we manage our resources efficiently,” Warren said.

Along the way, ULN itself has been a jobs creator by hiring additional staff to run expanding programs.

“The growth was incremental and methodical,” Warren said, “We didn’t want to grow too big, too fast. We wanted to be able to sustain our programs. Our ability to administer quality programs got the support of our donor-philanthropic-corporate-public communities.

“We have been able to maintain our workforce and sustain our programs. The credit is due to our staff and to the leadership provided by our board of directors.”

Warren’s 10 years at the top of ULN is the longest since Dillard’s reign from 1983 to 2000. Under Warren, the organization’s back to more of its social justice past.

Even though Mrs. T’s firebrand activism is not the League’s style, sometimes causing her to clash with the reserved Warren, whom she calls “Chief,” she said they share the same values.

“We just try to correct the wrong that’s done to people. I always have liked to right a wrong.”

She also likes it when Warren breaks his reserve to tell it like it is to corporate big wigs and elected officials.

“When he’s fighting for what he believes, Chief can really be angry and forceful, and they can’t pull the wool over his eyes because he sees through it.”

Mrs. T feels ULN’s back to where it was under Dillard.

“It was very strong then and I feel it’s very strong now. In between Mr. D and Chief, we had a number of acting or interim directors and even though those people meant well, until you get somebody solid, you’ve got a weakness in there.”

Pat Brown agrees. She’s been an Urban Leaguer since 1962. Her involvement deepened after joining the ULN Guild in 1968. The Guild’s organized everything from a bottillon to fundraisers to nursing home visits.

“Things were hopping. We had everything going on and everything running smoothly taking part in community things, working with youth, putting on events.”

She sees it all happening again.

Kathy J. Trotter also has a long history with the League. She reactivated the guild, which is ULN’s civic engagement-fundraising arm. She said countless volunteers, including herself, have “grown” through community service, awareness and leadership development through Guild activities. She chaperoned its black college tour for many years.

Trotter likes “to share our vision that a strong African- American community is a better Nebraska” with ULN’s diverse collaborators and partners.

Much of ULN’s multicultural work happens behind-the-scenes with CEOs, elected officials and other stakeholders. ULN volunteers like Trotter, Mrs. T and Pat Brown as well as Warren and staff often meet notables in pursuit of the movement’s aims.

“I don’t think people realize the amount of work we do and the sheer number of programs and services we provide in education, workforce development, violence prevention,” Jason Hansen said. “We have programs and services tailored to fit the community.”

Most are free.

“When you talk about training the job force of tomorrow, it begins with youth and education,” Hansen said. “We’ve seen a significant rise of African-Americans with a four-year college degree. That’s going to provide a better pipeline of talent to serve Omaha.”

Warren devised a strategic niche for ULN.

“We narrowed our focus on those areas where we not only felt we have expertise but where we could have the greatest impact,” he said. “If we have clients who need supportive services, we simply refer them.”

Some referrals go to neighbors Salem Baptist Church, Charles Drew Health Center, Family Housing Advisory Services, Omaha Small Business Network and Omaha Economic Development Corporation.

“We feel we can increase our efficiency and capacity by collaboration with those organizations.”

EDUCATION

Since refocusing its efforts, ULN regularly lands grants and contracts to administer education programs for entities like Collective for Youth.

ULN works closely with the Omaha Public Schools on addressing truancy. It utilizes African-American young professionals as Youth Attendance Navigators to mentor target students in select elementary and high schools to keep them in school and graduating on time.

Community Coaches work with at-risk youth who may have been in the juvenile justice system, providing guidance in navigating high school on through college.

ULN also administers some after school programs.

“Many of these kids want to know someone cares about their fate and well-being,” Warren said. “It’s mentoring relationships. We can also provide supportive services to their families.”

The Whitney Young Jr. Academy and Project Ready provide students college preparatory support ranging from campus tours to applications assistance to test prep to essay writing workshops to financial aid literacy.

“Many of them are first-generation college students and that process can be somewhat demanding and intimidating. We’re going to prepare the next generation of leaders here and we want to make sure they’re ready for school, for work, for life.”

Like other ULN staff, Academy-Project Ready coordinator Nicole Mitchell can identify with clients.

“Growing up in the Logan Fontanelle projects, I was just like the students I work with. There’s a lot I didn’t get to do or couldn’t do because of economics or other barriers, so my heart and passion is to make sure that when things look impossible for kids they know that anything is possible if you put the work and resources behind it. We make sure they have a plan for life after high school. College is one focus, but we know college is not for everyone, so we give them other options besides just post-secondary studies.”

“We want to make sure we break down any barrier that prevents them from following their dreams and being productive citizens. Currently, we have 127 students, ages 13 to 18, enrolled in our academy.”

Whitney Young Jr. Academy graduates are doing well.

“We currently have students attending 34 institutions of higher education,” said ULN College Specialist Jeffrey Williams. “Many have done internships. Ninety-eight percent of Urban League of Nebraska Scholarship recipients are still enrolled in college going back to 2014. One hundred percent of recipients are high school graduates, with 79% of them having GPAs above 3.0.”

Warren touts the student support in place.

“We work with them throughout high school with our supplemental ed programs, our college preparatory programs, making sure they graduate high school and enroll in a post-secondary education institution. And that’s where we’ve seen significant improvements.

“When I started at the Urban League, the graduation rate for African-American students was 65 percent in OPS. Now it’s about 80 percent. That’s statistically significant and it’s holding. We’ve seen significant increases in enrollment in post-secondary – both in community colleges and four-year colleges and universities. UNO and UNL have reported record enrollments of African-American students. More importantly, we’ve seen significant increases in African-Americans earning bachelor degrees – from roughly 16 percent in 2011 to 25 percent in 2016.”

With achievement up, the goal is keeping talent here.

TALENT RETENTION

A survey ULN did in partnership with the Omaha Chamber of Commerce confirmed earlier findings that African-American young professionals consider Omaha an unfavorable place to live and work. ULN has a robust young professionals group.

“It was a call to action to me personally and professionally and for our community to see what we can do cultivate and retain our young professionals,” Warren said. “The main issues that came up were hiring and promotions, professional growth and development, mentoring and pay being commensurate with credentials. There was also a strong interest in entrepreneurship expressed.

“Millenials want to work in a diverse, inclusive environment. If we don’t create that type of environment, they’re going to leave. We want to use the results as a tool to drive some of these conversations and ultimately have an impact on seeing things change. If we are to prosper as a community, we have to retain our talent as a matter of necessity.We export more talent than we import. We need to keep our best and brightest. It’s in our own best interest as a community.”

The results didn’t surprise Richard Webb, ULN Young Professionals chair and CEO of 100 Black Men Omaha.

“I grew up in this community, so I definitely understand the atmosphere that was created. We’ve known the problems for a long time, but it seemed like we never had never enough momentum to make any changes. With the commitment and response we’ve got from the community, I feel there’s a lot of momentum now for pushing these issues to the front and finding solutions.”

“Corporate Omaha needs to partner with us and others on how we make it a more inclusive environment,” Jason Hansen said.

With the North O narrative changing from hopeless to hopeful, Hansen said, “Now we’re talking about how do we retain our African-American young talent and keep them vested in Omaha and I’d much rather be fighting that problem than continued increase in poverty and violence and declining graduation rates.

Webb’s attracted to ULN’s commitment to change.

“It’s representing a voice to empower people from the community with avenues up and out. It gathers resources and put families in better positions to make it out of The Hood or into a situation where they’re -self-sustaining.”

CAREER READINESS

On the jobs front, ULN conducts career boot camps and hosts job fairs. It runs a welfare to work readiness program for ResCare.

“We administer the Step-Up program for the Empowerment Network,” Warren said. “We case managed 150-plus youth this past summer at work sites throughout the city. We provide coaches that provide those youth with feedback and supervise their performance at the worksites.”

Combined with the education pieces, he said, “The continuum of services we offer can now start as early as elementary school. We can work with youth and young adults as they go on through college and enter into their careers. Kids who started with us 10 years ago in middle school are enrolled in college now and in some cases have finished school and entered the workforce.”

The Urban League maintains a year-round presence in the Community Engagement Center at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

Olivia Cobb is part of another population segment the League focuses on: adults in adverse circumstances looking to enhance their education and employability.

Intensive case management gets clients job-school ready.

After high school, Cobb began studying nursing at Metropolitan Community College but gave birth to two children and dropped out. Through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act program ULN administers, the single mom got the support she needed to reenter school. She’s on track to graduate with a nursing degree from Iowa Western Community College.

“I just feel like I’ve started a whole new chapter of my life,” Cobb said. “I was discouraged for awhile when I started having children. I thought I was going to have to figure something else out. I’m happy I started back. I feel like I’ve put myself on a whole new level.

“The Urban League is like another support. I can always go to them about anything.”

George Dillard said it’s always been this way.

“A lot of the stuff the Urban League does is not readily visible. But if you talk with the clients who use the Urban League, you’ll find the services it provides are a welcome addition to their lives. That’s what the Urban League is about – making people’s lives easier.”

ULN’s Rozalyn Bredow said Cobb is one of many success stories. Bredow’s own niece is an example.

“She wanted to be a nurse but she became a teen parent. She went to Flanagan High, graduated, did daycare for awhile. She finally came into the Workforce Innovation program. She went to nursing school and today she’s a nurse at Bergan Mercy.”

Many Workforce Innovation graduates enter the trades. Nathaniel Schrawyers went on to earn his commercial driver’s license at JTL Truck Driver Training and now works for Valmont Industries.

Like Warren, Bredow is a former law enforcement officer and she said, “We know employment helps curb crime. If people are employed and busy, they don’t have a whole lot of time to get into nonsense. And we know people want to work. That’s why we’ve expanded our employment and career services.”

VIOLENCE PREVENTION

The League’s violence prevention initiatives include: Credit recovery to obtain a high school diploma; remedial and tutorial education; life skills management; college prep; career exploration; and job training.

“Gun assaults in the summer months in North Omaha are down 80 percent compared to 10 years ago,” Warren said. “That means our community is safer. Also,the rate of confinement at the Douglas County Youth Center is down 50 percent compared to five years ago. That means our youth and young adults are being engaged in pro-social activities and staying out of the system – leading productive lives and becoming contributing citizens.”

Warren co-chairs the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative. “Our work is designed to keep our youth out of the system or to divert those that have been exposed to the system to offer effective intervention strategies.”

Richard Webb said having positive options is vital.

“It’s a mindset thing. Whenever people are seeing these resources available in their community to make it to greatness, then they do start changing their minds and realizing they do have other options.

“Growing up, I didn’t feel I had too many options in my footprint. My mom was below poverty level. My dad wasn’t in the house.”

But mentoring by none than other than Thomas Warren helped him turn his life around. He finished high school. earned an associates degree from Kaplan University and a bachelor’s degree from UNO. After working in sales and marketing, he now heads a nonprofit.

Wayne Brown, ULN vice president of programs, knows the power of pathways.

“My family was part of the ‘alternative economy.’ It was the family business. My junior year at Omaha Benson I was bumping around, making noise, when an Urban League representative named Chris Wiley grabbed me by the ear and gpt me to take the college and military assessment tests. He made sure I went on a black college tour. I met my wife on that tour. I got a chance to be around young people going in the college direction and I had a good time.”

Brown joined the Army after graduating high school and after a nine year service career he graduated from East Tennessee State University and Creighton Law School. After working for Avenue Scholars and the Omaha Community Foundation, he feels like he’s back home.

“I wouldn’t have been able to do all that if I hadn’t done what Mr. Wiley pushed me to do. So the Urban League gave me a start, a path to education and employment and a sense of purpose I didn’t have before.”

Informally and formally, ULN’s been impacting lives for nine decades.

“To be active in Omaha for 90 years, to have held on that long, is fantastic,” Pat Brown said. “Some affiliates have faltered and failed and gone out of business. But to think we’re still working and going strong says something. I hope I’m around for the 100th anniversary.”

Mrs. T rues the wrongs inflicted on the black community. But she’s pleased the League’s leading a revival.

“I’ve seen some good changes. It makes me feel good we are still here and still standing and that I’m around to see that. It’s a good change that’s coming.”

Visit http://www.urbanleagueneb.org.

Rony Ortega follows path serving more students in OPS

To be a public schools advocate, one doesn’t have to be a public education institution graduate. Nor does one need to be a professional public schools educator or administrator, But in Rony Ortega’s case, he checks yes to all three and he feels that background, plus a strong work ethic and desire to serve students, gives him the right experience for his new post as a district executive director in the Omaha Public Schools. He supervises and guides principals at 16 schools and he loves the opportunity of impacting more students than he ever could as a classroom teacher, counselor, assistant principal and principal. He also feels his own story of educational attainment (two master’s degreees and a doctorate) and career acheivement (a senior administrative position by his late 30s) despite a rough start in school and coming from a working-class family whose parents had little formal education is a testament to how far public education can carry someone if they work hard enough and want it bad enough. Read my profile of Rony Ortega in El Perico.

Rony Ortega follows path serving more students in OPS

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

Rony Ortega has gone far in his 15-year career as an educator. He worked in suburban school districts in Elkhorn and Papillion before recruited to the Omaha Pubic Schools by former OPS staffer and veteran South Omaha community activist, Jim Ramirez.

Ortega. who’s married with three daughters, all of whom attend OPS, has moved from classroom teacher and high school counselor to assistant principal at South High to principal of Buffett Middle School. Earlier this year, he was hired as a district executive director tasked with supporting and supervising principals of 16 schools.

The Southern California native traces his educational and professional achievement to his family’s move to Nebraska. Negative experiences in Los Angles public schools in the 1980s-1990s – gang threats, no running water, rampant dropouts – fueled his desire to be a positive change agent in education. In Schuyler, where his immigrant parents worked the packing plants, he was introduced to new possibilities.

“I’m thankful my parents had the courage to move us out of a bad environment. Really, it wasn’t until I got here I met some key people that really changed the trajectory of my life. I met the middle class family I never knew growing up. They really took me under their wing. We had conversations at their dinner table about college-careers – all those conversations that happen in middle class homes that never happened in my home until I met that family.

“That was really transformational for me because it wasn’t until then I realized my future could be different and I didn’t have to work at a meatpacking plant and live in poverty. I really credit that with putting me on a different path.”

He began his higher education pursuits at Central Community College (CCC) in Columbus.

“I went there because, honestly, it was my only option. I was not the smartest or sharpest kid coming out of high school. Just last year, I was given the outstanding alumnus award and was their commencement speaker. I was humbled. Public speaking is not something I really enjoy, but I did it because if I could influence somebody in that crowd to continue their education, it was worth it. And I owed it to the college. That was the beginning of my new life essentially.”

He noted that, just as at his old school in Schuyler, CCC-Columbus is now a Hispanic-serving institution where before Latinos were a rarity. His message to students: education improves your social mobility.

“No one can take away your education regardless of who you are, where you go, what you do.”

He completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and went on to earn two master’s and a doctorate at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

“I’m really the first in my family to have more of an educational professional background,” Ortega said, “I don’t think my parents quite yet grasp what I do for a living or what all my education means, so there’s some of that struggle where you’re kind of living in two worlds.”

He expects to keep advancing as an administrator.

“I have a lot of drive in me, I have a lot of desire to keep learning. I do know I want to keep impacting more and more kids and to have even a broader reach, and that is something that will drive my goals going forward.

“It’s very gratifying to see your influence and the impact you make on other people. There’s no better feeling than that.”

He’s still figuring out what it means to be an executive director over 16 principals and schools.

“For now, I’m focusing on building relationships with my principals, getting to know their schools, their challenges, observing what’s happening. So right now I’m just doing a lot of leading through learning. It’s quite the challenge with not only the schools being elementary, middle and high schools but being all over town. Every school has challenges and opportunities – they just look different. I’m trying to learn them.

“When I was a principal, I had teachers who needed me more than others. I’m learning the same thing is true with principals – some need you more because they’re new to the position or perhaps are in schools that have a few more challenges.”

Having done the job himself, he knows principals have a complex, often lonely responsibility. That’s where he comes in as support-coach-guide.

“We’re expecting principals to be instructional leaders but principals have a litany of other things to also do. Our theory of action is if we develop our principals’ capacity, they will in turn develop teachers’ capacity and then student outcomes will improve.”

He knows the difference a helping hand can make.

“No matter where I’ve been, there’s always been at least one person instrumental in influencing me. The research shows all it takes is one person to be in somebody’s corner to help them, and there’ve been people who’ve seen value in me and really invested in me.”

His educational career, he said, “is my way of giving back and paying it forward.”

“It’s so gratifying to wake up every day knowing you’re doing it for those reasons. That’s really powerful stuff.”

He purposely left the burbs for more diverse OPS.

“I kept thinking I’ve got to meet my heart. I wanted to do more to impact kids probably more like me.”

He’s proud that a district serving a large immigrant and refugee population is seeing student achievement gains and graduation increases, with more grads continuing education beyond high school.

As he reminds students, if he could do it, they can, too.

Amanda Ryan brings lifelong passion for education to school board

Serving on the Omaha Public Schools board has got to be one of the more challenging non-paid positions around. First of all, you have to get appointed or elected. Then comes the reality of representing your subdistrict and the community as a whole as a voting member of the governing body that’s over the superintendent and the administration of a very large and diverse urban school district serving 52,000 students. Throw in the fact that public schools are something every one has an opinion about – often a highly critical one at that – plus the fact that education brings up emotionally charged issues surrounding children, families, resources and opportunities, and certain disparities involving them, and you have the makings for one tough job. Despite all this, Omaha Public Schools board member Amanda Ryan loves the work and the responsibility. Her service is part of a lifelong passion she’s had for education. Read my El Perico profile of her here.

Amanda Ryan brings lifelong passion for education to school board

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

When Amanda Ryan and her fellow Omaha Board of Education members couldn’t agree on hiring a new OPS superintendent last spring, it left that search in limbo and the community asking questions.

Now, this emerging young leader is gearing up with her colleagues for a new search sure to be closely followed by stakeholders and media outlets.

The Minden, Neb. native is a third generation Mexican-American on her mother’s side and identifies as a Latina. “That’s something that’s really important to me,” said Ryan, who is single with no children.

The 26-year-old is finishing work on her master’s in sociology at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, just one of several markers she’s surpassed in her family.

“It’s interesting having to navigate being the first one in your family going to college,” she said.

Until winning the race for the Subdistrict 7 school board seat in 2016, she’d never run for or held public office before. She came on the board in a transition period that saw several new members elected to the body. The nine-member board selects the superintendent, sets policy, does strategic planning and oversees the broad brushstrokes of a diverse urban public school district serving 52,000 students, including many from migrant, immigrant and refugee populations.

Ryan feels her ethnic background, combined with her studies, her past experience working for Project Interfaith and her current job with the Institute for Holocaust Education, gives her insight into the district’s multicultural mosaic.

“I think all my education and life experience comes back to cultural understanding. With the wide array of students and staff we have in OPS. I think it’s important to remember those things.”

She sees a need for more minorities to empower themselves.

“In the political atmosphere we live in now, I think it’s really important people from marginalized communities express themselves and show that identity. That’s something I kind of ran on. It’s important kids see people similar to them doing important things so they realize, ‘Oh, I can be a leader, I can strive to do that as well.’ I think that’s something we need more of In Neb. We’re starting to have more leaders of color emerge, but it’s going to take some more time to do that.”

She credits former Omaha Public Schools board member and current Nebraska state legislator (District 7) Tony Vargas with emboldening her to run.

“Tony has been a very big influencer and mentor.”

Her decision to serve was intensely personal.

“Education has been such a huge motivating factor in my life. Everything I’ve done, every career aspiration I’ve had has to do with education. I can pinpoint teachers throughout my educational experience that have motivated me and helped me get to different places. I wanted it to pay it back somehow,”

Running for the board, she got some push-back for not having a child in OPS and for her youth. Regarding her age, she said, “I know during my campaign some people viewed it as a negative, but I think it’s a positive. It wasn’t that long ago I was in public school worrying about everything. I know some of these struggles these kids are going through.”

She has some goals for this academic school year.

“I am going to try in to be in the schools a lot more building relationships and rapport with teachers and administrators. I know morale is low. I think you can see that in board meetings when the teachers’ union and support staff come out and express these extreme frustrations.

“I want to do more community forum-listening sessions so that people are heard.”

In the wake of internal board contention that resulted in stalemates, members participated in a training session to improve communication skills and build unity.

“It was a bad experience for me starting off with all of that – the failed superintendent search, some of us wanting change in board leadership and others not wanting it. Then nobody wanting to work together to fix it. That was really hard.”

She said personality and idealogical differences – “I’m the furthest on the left politically on the board” – are being put aside.

“I do think it’s getting a lot better.”

She said disagreements are bound to occur and can even be healthy.

“Conflict isn’t bad. Out of conflict comes change and that change can be really good.”

About the new superintendent search, she said, “It’s something I really want to make sure we do right. We need to get good candidates and we need to select the right person. I think that’s going to be the biggest thing.”

Incumbent district chief Mark Evans is delaying his retirement a year to shepherd OPS until his successor’s hired and assumes the post next summer. Whoever fills that role, Ryan said, will have a full agenda.

“We’re going to be facing a lot of budget issues and we need somebody who’s going to be creative and progressive in how they deal with that. We are going to have to be very strategic to maximize as many different streams of revenue as we can. We need somebody who is politically savvy to work with state legislators and community organizations.”

Ryan knows something about making one’s own path.

“I’m ridiculously independent,” she said.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

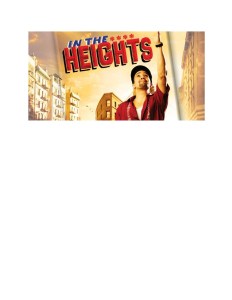

Art in the heart of South Omaha

Until I saw a Facebook post about Omaha South putting on a production of “In the Heights” in collaboration with SNAP! Productions. it had somehow escaped me that South was the Omaha Public Schools’ Visual and Performing Arts Magnet. The show, which I saw and was most impressed by, was a fundraiser for a planned visual and performing arts addition at the school, which has a robust arts curriculum far surpassing anything found in another OPS building. Indeed, the quality of the show was so high that it sold me on writing a story for The Reader about the arts magnet emphasis at the inner city school. I then found out from faculty and students just how much is going on there and how passionate these educators and kids are about what they do in the arts. My resulting story is shared here. It appears in the September 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Art in the heart of South Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the September 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Chances are, you don’t know Omaha has a public high school of performing arts, It may further surprise you that South High School is that Fame-style institution.

South has been the Omaha Public Schools’ Visual & Performing Arts Magnet for two decades. But the architect for the arts emphasis there, retired South drama teacher Jim Eisenhardt, said “by the time we were named an arts magnet, we were already an arts magnet in all but name.”

Dramatic growth in student numbers has seen a corresponding growth in programs that finds South with the district’s most robust arts curriculum. Students can even elect to be an arts major. Seventy percent of all students take at least one arts class. Forty percent take at least two. Participation has exploded, especially in dance and guitar.

The interest and activity have South facing serious space issues to accommodate it all. Thus, the school’s embarked on a $12 million private fundraising campaign for a planned Visual & Performing Arts addition.

Becky Noble, South curriculum specialist and a drts Magnet facilitator, said space is at such a premium that some labs and classrooms meet in cramped former “closets.” Film and music technology classes share the same small digs. Neither has a dedicated studio.

“We can’t grow music tech and film anymore.”

With no permanent spaces for some classes, she said, “they’re constantly moving from place to place.” Even the dance studio is makeshift. The present black box theater lacks flexibility and accessibility.

She described conditions as “maxed out,” adding, “We need space that is appropriate to enhance learning.”

Then there’s the battle for updated technology. She said it can be difficult getting district officials to accept why not just any computers or software programs will do for the high-end things students create in film, digital art and music tech.

“We are so unusual in the district that sometimes they almost don’t know what to do about us.”

Asking for state-of-the-art gear and contracting professionals to teach dance takes some explaining.

“It’s an ongoing kind of beating our heads with having them understand that it is a special thing and it is important, it’s not just a fluff thing. We don’t have students in here for fluff. We have them in here because there is a real, honest curriculum.”

“Our basic philosophy to use art as a springboard to enhance problem-solving and abstract thought,” South theater director Kevin Barratt said.

Noble said the fact teachers make-do and still net great results speaks to their commitment.

“It is really a labor of love.”

The 55,000 square foot addition would add seven general education classrooms, dedicated studio spaces, a new black box theater and an art gallery. Noble said South’s fortunate to have a strong advocate making its case in Toba Cohen-Dunning, executive director of the Omaha Schools Foundation, the project’s fiscal agent.

Administrators, such as former principal Cara Riggs, are arts advocates, too. “She put some additional money behind it and now our current principal Ruben Cano is doing a great job of listening,” Noble said.

“The equity formula of the Omaha Public Schools allowed for dollars to follow students,” Riggs said. “As we received more dollars for our magnet students, we continued to find ways to strengthen our magnet programs, We found it important to create programs in the arts that students couldn’t get anywhere else in the metro: Dance taught by professional dance instructors; a piano lab and a guitar program; a film program and a computer gaming program.

“Our school culture improved and enrollment rocketed, with successful programs and positive word-of-mouth.”

South staffers, past and present, say they hoped the arts would catch fire but Eisenhardt said no one expected this.

“We started a dance class with 12 kids and now it’s up above 400 (with five styles offered). There are over 300 kids in guitar and piano.”

Alum Kate Myers Madsen, who was active in music and theater at South, theorizes why the arts flourish there.

“I think the reason it’s so well-received is that it’s so in the community of people who are incredibly talented but might not come from homes that have the means to put them in private voice or instrument lesson and dance classes. It’s providing huge value to students who normally would not be able to access it.”

This arts infusion didn’t just happen, it was intentionally built by Eisenhardt and Co. from 1982 to his 2006 retirement. He cultivated relationships with community arts organizations that exposed students to professionals in many disciplines. Over time, South became the district’s arts epicenter and the magnet designation naturally followed.

“My colleagues across the district knew what the arts program was at South,” he said. “No one ever asked me why we got it (magnet status) and not somebody else. There were great arts teachers already here like Toni Turnquist and Mary Lou Jackson and Josh Austin working hard to create something important.”

Then-principal Joyce Christensen granted great autonomy and Eisenhardt ran with it.

“She encouraged people to do things that were innovative and making sure the kids had the best experience they could in high school. I would just forge ahead and do something, not necessarily checking with her for permission first, but she supported it. She knew I would never do anything to embarrass South High.

“Roni Huerta, my counterpart as the magnet coordinator for Information & Technology, was a big supporter of what we did in the arts. Because of her we got the dance classes to count as physical education credits.”

Eisenhardt said Jerry Bartee, another former South principal, also lent great support.

Many things make South an arts magnet. Start with the array of class options available and the fact these disciplines have different sections and levels. There are multiple music ensembles as well.

Before coming to South, Eisenhardt was at Omaha Tech, where he formed relationships with Opera Omaha’s Jane Hill and the Omaha Community Playhouse’s Charles Jones. Opera rehearsals were held at Tech. The Nebraska Theatre Caravan rehearsed A Christmas Carol there. When Tech closed, Eisenhardt invited these rehearsals to travel to South. The ties were eventually formalized as Adopt-a-School partnerships.

“Both of those had great impact on our success as a magnet school,” Eisenhardt said.

Omaha music director Hal France worked with Opera Omaha then.

“We had a home on the South High Auditorium stage rehearsing all our shows with international and national opera singers and directors. Despite putting on five shows a year of their own at South, Jim always made the schedule work for us. It was a dream. It was a relationship based on trust that emanated first and foremost from Jim, a magnificent, remarkable host.”

Opera Omaha even collaborated with South on three productions with staff-students. The last of these, Bloodlines, was a 2004 original with a libretto by Jane Hill and Eisenhardt and a score by Deb Teason,

“Jane and I worked with the kids to write a script based on their experiences as immigrants in Omaha,” Eisenhardt said. “The title came from the idea that these immigrants worked the bloodlines in the packinghouses and also the bloodlines of their families.

“That year the Omaha World-Herald named it one of the top ten cultural events in Omaha. It was quite a production and really an important part of the development of the magnet. By the time that was over, the magnet was in full swing.”

Riggs said with those kinds of collaborations, “we were able to create extra-value in the school experience, beyond the many required academic courses.”

Outside district and arts circles, South’s magnet identity is a best-kept-secret. The school’s inner-city location, working-class environment and low achievement scores may not fit some perceptions of what an arts magnet should look like.

“That’s all a big part of it,” Noble said. “It’s our challenge. One of the things we talk a lot about is that we have to continue to get more and more known in the community.”

Noble hopes others see South’s diversity as an asset.

“When we go to some competitions, most of the other schools are all white, but our kids represent what the world looks like.”

Senior arts major Jax Barkhouse, who lives in West Omaha and was expected to follow his friends to a suburban school, battled those perception issues.

“It was especially hard for me because people were like, ‘Why are you going to South?’ They think bad things about it. But I only tell them good things about it.”

South has traditionally been the main receiving school for immigrant, refugee and migrant populations. After a sharp enrollment decline, it’s experienced a renaissance. The rebirth has coincided with the boon of the South 24th business district it borders and the arrival of Latino and Sudanese families in the surrounding neighborhoods it serves.

The school’s home to a dense demographic of Latinos, Africans, Asians, African-Americans and Caucasians. South’s vast arts program and additional magnets in Information & Technology and Dual Language have made it the school of choice for the overwhelming majority of students in its home attendance area.

South also draws students from outside the area attracted to its focused offerings.

Madsen, Barkhouse and junior Ori Parks bypassed their home schools for South due to its arts concentration.

“It surpassed anything I had expected,” said Madsen. “I did a lot of things outside school.”

South funded most of her travel to Great Britain for a Playhouse-sponsored theater immersion. Since graduating in 2006, she’s performed at the Shelterbelt, The Rose and Iowa Western Community College.

“The opportunities afforded me at South allowed me to really identify what it was I loved about the arts and which track I wanted to follow. I had been classically trained up until my freshman year in high school, so the opportunity to do musical theater really allowed me to see what it was that I loved about theater performing,”

Barkhouse followed his heart to South.

“I was supposed to go to Burke, but I chose to come down here because of the performing arts. I’m so glad that I chose South. I love it.”

He plans majoring in musical theater in college.

Parks, who lives closer to Benson, was sold on South because of its rich arts options.

“I was like, whoa, they have all this stuff.”

“Having easy access to the arts here at South is really a great benefit,” said Jennifer Au, among the 80 percent of arts majors on the honor roll. “I think being involved in the arts really helps me with my schoolwork.”

Results like these help explain why there’s such energy and interest from students in going there.

“When I left South, we averaged 1,300 students and now its 2,500,” said Eisenhardt, “and a lot of that’s because of the success the kids have found in the arts, the teachers there supporting the arts and the work the kids do outside the normal classroom.”

It doesn’t hurt that South graduates are findings careers in the arts. Rachel McCutcheon stage managed The Book of Mormon on Broadway. Paul Coate performed with Nebraska Shakespeare, Nebraska Repertory Theatre, Opera Omaha and the Omaha Symphony. Since moving to Minneapolis, he’s acted with the Guthrie Theatre and sung with the Minnesota Orchestra and St. Paul Chamber Orchestra.

“My experiences at South were the foundation on which I built my career as a performing artist,” Coate said. “The arts programming and faculty leadership were very strong. I feel very lucky to have been in such a good place at such a pivotal time in my life.

There’s real talent there, too. Just ask director Kevin Lawler, who’s helmed work nationally. He was at the Blue Barn when Hill asked him to direct Bloodlines. In his current post as Great Plains Theatre Conference artistic director, he’s made South an integral part of the annual Playfest series. Visiting L.A. playwright Michael John Garces wrote an original piece called South drawn in part from interviews with students that he and the show’s director, Scott Working, conducted.

“The staff work immensely hard to give the education, tools and positive creative channels to these, the next generation of great young creatives and artists of Omaha,” Lawler said. “There is so much talent and energy packed into South High each day that, with the proper support, the impact that it can have on our city in terms of our cultural life and our community will be immeasurable.”

South, with students as the mainstay performers, premiered at the conference in late May to a warm reception. In July, a joint South-SNAP! Productions mounting of In the Heights elicited raves and kicked off the “Art in the Heart of South Omaha” campaign for the new addition. South theater students worked the show, including Aimee Perez-Valentin, who ran tech. Alums participated as well, including Kate Myers Madsen in the role of Vanessa and Esmeralda Moreno Villanueva stage managing.

“It was very interesting being on the other side of it this time in this more mature role,” Madsen said. “”For me, it was very much coming home because that was my first stage where I stepped out as a musical theater performer. For a lot of these students, it was their first show. They were experiencing what I did the first time. I was blown away by their talent.

“We have a lot of talent, not only in Omaha but at this school specifically.”

Theater students have made the cut for the Playhouse’s apprentice program.

Senior Jax Barkhouse earned a role in the Playhouse’s production of Mamma Mia! opening September 15.

Grad Ja’Taun Markel Pratt is attending the New York Conservatory for Dramatic Arts.

South’s 2016 production of Check Please was selected to perform at the International Thespian Festival in Lincoln. Three students recognized for Outstanding Performances over the last four years

The Show Choir made it to nationals last year.

“We have kids at the top levels of dance who are getting dual enrollment credit at UNO for dance and who are majoring in dance at UNL,” Noble said.

2013 grad and University of Nebraska at Omaha senior Maria Fernanda Reyes performs with UNO’s prestigious Moving Company dance troupe.

Noble said South instrumental music students get a firm foundation in music theory, ear training, sight reading, et cetera. Music tech grads are being prepared to enter audio engineering college studies and careers.