Archive

North Omaha Summer Arts back for 6th annual free arts festival

North Omaha Summer Arts back for 6th annual free arts festival

NOSA is dedicated to the proposition that the arts can positively change the world and the community. Support local arts and local artists because they are making a difference through their work. Let’s make this a beautiful, arts-filled summer. And hope to see you at our family-friendly, community-based events.

Check out the schedule below:

We are delighted to announce that June 2016 marks the beginning of the 6th year for North Omaha Summer Arts (NOSA), a free, grassroots, community-based arts festival!

Our mission is to bring the experience of art in all forms to the community of North Omaha. NOSA classes and events are open and free of charge to everyone.

The summer-long fest is the creation of North Omaha native and North High graduate Pamela Jo Berry. She is a veteran artist and art educator who lives in North Omaha.

Pamela began NOSA in the summer of 2011 with the support and assistance of fellow parishioner Denise Chapman and Pastor John Backus when she saw a need for more art to be infused into her community. She also wanted to provide more opportunities for area artists to exhibit their work and talent. Under the NOSA banner she organized community arts events and activities, including writing classes, a Gospel Concert and an Arts Crawl, open to all. As the community has embraced the offerings, NOSA has added new programming and partners. The goal is for this arts festival to continue growing and flourishing, but it needs help to do that.

Pamela administers NOSA with the help of volunteers. She has found success paired with a volunteer board who has history and interest in the areas of both North Omaha and the arts.

NOSA has attracted a loyal following for its annual events. New programs and opportunities continue to be added. It is truly a privilege for everyone involved to celebrate the arts in North Omaha and to provide these enriching experiences.

2016 Highlights include:

Gospel Concert in the Park

Saturday, June 18

5 to 7:30 pm

Miller Park

The 6th annual Gospel Concert in Miller Park features soloists, ensembles and choirs performing a variety of gospel styles.

NOTE: Watch for announcements about the concert’s performing artists lineup

Women’s Writing Classes and Retreats

Wednesdays, June 1 through July 27

5:30 pm dinner followed by 6 to 8 pm class

Trinity Lutheran Church

This summer the focus is on Getting Published.

Facilitator Kim Louise is a playwright and best-selling romance novelist who guides participants in finding their inner writer’s voice.

Art and Gardening Class

Saturday, July 9

10:30 am to 12:30 pm

Florence Branch Library

Combine your passion for making and growing things in a fun-filled session painting art on clay pots and planting flowers that attract pollinators.

NEW EVENT

Pop-Up Art

Various locations TBA

Happening throughout July, Pop-Up Art gives adults and children the opportunity to create art at different locations around North Omaha.

Arts Crawl

Friday, August 12

Reception at Charles Washington Branch Library

5:30-6:30 pm.

The Crawl at several venues on or near North 30th Street

6 to 9 pm

This walkable, continuous art show showcases the diverse work of emerging and established artists at venues on or near North 30th Street. The Crawl starts at the Metropolitan Community College Fort Omaha campus Mule Barn building and ends at the North Heartland Family Service – with Church of the Resurrection, Nelson Mandela School and Trinity Lutheran in between. Walk or drive to view art in a wide variety of mediums, to watch visual art demonstrations and to speak with artists about their practice. Enjoy live music at some venues.

NOTE: Watch for posts about The Crawl’s visual and performing artists roster.

COMING SOON: Look for our announcement about an opportunity to help NOSA continue offering these and other arts experiences free of charge to the community.

Like/follow NOSA on Facebook–

NOSA Facebook Page https://www.facebook.com/NorthOmahaSummerArts/?fref=ts

NOSA Facebook Group https://www.facebook.com/groups/1012756932152193/

For more information, to be a participating artist or to partner with NOSA, call 402-502-4669.

Girls Inc. makes big statement with addition to renamed North Omaha center

Girls Inc. of Omaha has added to the heavy slate of north side inner city redevelopment with a major addition that’s prompted the renaming of its North O facility to the Katherine Fletcher Center. Though the center’s longtime home, the former Clifton Hill Elementary School building, remains in use by Girls Inc. and is getting a makeover, the connected 55,000 square foot addition is so big and colorful and adds so much space for expanded programs and new services that it is the eye candy of this story. Here is a sneak peek at my story for the June issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com) about what the addition will mean to this organization and to the at-risk girls it inspires to be “strong, smart and bold.” The $15 million project is another investment in youth, opportunity and community in North O on top of what has already happened there in recent years (NorthStar Foundation, No More Empty Pots, Nelson Mandela School) and what is happening there right now (Union for Contemporary Art getting set to move into the renovated Blue Lion Center, the North 75 Highlander Village under construction, the three new trades training buildings going up on the Metro Fort Omaha campus). But so much more yet is needed.

North Omaha Girls Inc. makes big statement with addition

New Katherine Fletcher Center offers expanded facilities, programs

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the June 2016 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

A poor inner city North Omaha neighborhood recently gained a $15 million new investment in its at-risk youth.

The Girls Inc. center at 2811 North 45th Street long ago outgrew its digs in the former Clifton Hill Elementary School but somehow made do in cramped, out-dated quarters. Last month the nonprofit dedicated renovations to the old building as well as the addition of an adjoining 55.000 square foot structure whose extra space and new facilities allow expanded programming and invite more community participation. The changes prompted the complex being renamed the Katherine Fletcher Center in honor of the late Omaha educator who broke barriers and fought for civil rights. The addition is among many recently completed and ongoing North O building projects worth hundreds of millions dollars in new development there.

This local after school affiliate of the national Girls Inc. takes a holistic approach to life skills, mentoring, career readiness, education enrichment and health-wellness opportunities it provides girls ages 5 through 18. Members are largely African-American, many from single parent homes. Others are in foster care. Young girls take pre-STEM Operation SMART through the College of Saint Mary. Older girls take the Eureka STEM program through the University of Nebraska at Omaha. There are also healthy cooking classes, aquaponics, arts, crafts, gardening, sports, field trips and an annual excursion outside Nebraska. Girls Inc. also awards secondary and post-secondary scholarships.

The addition emphasizes health and wellness through a gymnasium featuring a regulation size basketball court with overhead track, a fitness room, a health clinic operated by the University of Nebraska Medical Center, a space devoted to yoga, meditation, massage and a media room. Amenities such as the gym and clinic and an outdoor playground are open to the public. The clinic’s goal is to encourage more young women, including expectant and new mothers, to access health care, undergo screenings and get inoculations.

Dedicated teen rooms give older girls their own spaces to hang out or study rather than share space with younger girls as in the older facility. Multi-use spaces there became inadequate to serve the 200 or so girls who daily frequent the center.

“I think we’ll see more teens in our programs because this expansion separates them from the younger girls and provides more opportunities to get drawn into our programs,” says executive director Roberta Wilhelm. “They may start as drop-ins but we foresee them getting involved in the more core programs and becoming consistent members. So, we think we’ll impact more girls and families.”

A big, bright, open indoor commons area, the Girls Hub, is where the brick, circa 1917 historic landmark meets the glass and steel addition.

“The design team showed great respect for how to best join the two buildings and for the importance of this space and for the social aspects of how girls gather and interact,” Wilhelm says.

The impressive, brightly colored, prominently placed new addition – atop a hill with a commanding view – gives the organization a visual equivalent to its “strong, smart and bold” slogan.

“It’s a big statement,” says director of health access Carolyn Green. “It speaks loudly, it brings awareness, it turns heads. People can’t wait to come through and see what is all in here.”

Before the open house program director Emily Mwaja referenced the high anticipation. saying, “I’m ready, the girls are ready, we’re ready for everything.”

Girls Inc. member Desyree McGhee, 14, says, “I’m excited for the new building. I feel it’s giving us girls the opportunity for bigger and better things and bringing us together with the community. I just feel like a lot of good things could come from it.” Her grandmother, Cheryl Greer, who lives across the street, appreciates what it does for youth like Desyree and for the neighborhood. “It’s just like home away from home. I have seen her grow. She’s turning into a very mature, respectful young lady. I think Girls Inc. is a wonderful experience for these girls to grow up to be independent, educated adults. The center is a great asset for them and the community.”

McGhee says Girls Inc. empowers her “to not just settle for the bare minimum but to go beyond and follow your dreams. It’s really given me the confidence to thrive in this world. They really want you to go out and leave your mark. I love Girls Inc. That’s my second family.”

Girls Inc. alum Camille Ehlers, a University of Nebraska-Lincoln graduate, says caring adults “pour into you” the expectations and rewards youth need. “It was motivating to me to see how working hard would pay off.” She says she felt called to be strong, smart and bold. “That’s what I can make my life – I can create that.” Mentors nudged her to follow her passion for serving at-risk students, which she does at a South Side of Chicago nonprofit. Denai Fraction, a UNL pre-med grad now taking courses at UNO before medical school, says Girls Inc. nurtured her dream of being a doctor. Both benefited from opportunities that stretched them and their horizons. McGhee is inspired by alums like them and Bernie Sanders National Press Secretary Symone Sanders who prove anything is possible.

Wilhelm says, “Girls Inc. removes barriers to help girls find their natural strengths and talents and when you do that over a period of years with groups of girls you’re helping affect positive change. A lot of the girls are strong and resilient and have chops to get through life and school but if we can remove some barriers they will go so much farther and be able to accomplish so much more. We see ourselves in that business.

“If you help a girl delay pregnancy so she’s not a teen mom, it’s a health outcome, an education outcome, a job outcome, it’s all of those things, they’re all tied together. If you are feeding girls who are hungry that impacts academics and also impacts growing bodies. I do think our holistic model has become more intentional, more focused. We use a lot more partners in the community who bring expertise, We are all partners with parents and families in lifting up girls. The Girls Inc. experience is all these things but the secret sauce is the relationships adult mentors, staff and volunteers cultivate with youth.” Alums come back to engage girls in real talk about college, career and relationships. The shared Girls Inc. expereince creates networking bonds.

She says support doesn’t stop when girls age out. “Even after they graduate they call us for help. We encourage that reaching out. They know there’s someone on the other end of the phone they can trust.”Assistance can mean advice, referrals, funds or most anything.

Everyone from alums and members to staff and volunteers feel invested in the bigger, bolder, smarter Girls Inc.

“It’s not just about the million dollar donors,” Wilhelm says. “We all have ownership in this. I always tell the girls, ‘The community invests in you for a reason. They want you to create a better future for yourself, to be a good student, to focus on education, to live healthy, to make good choices. They think you’re worth this investment.'”

She says there’s no better investment than girls.

“Girls make decisions when they grow up for their families for education and health. To the extent you can educate girls to make wise decisions and choices you really do start to see cycle breaking changes. How you educate girls, how you treat girls, how you invest in girls matters over time and we’re a piece of that, so we’re foundational.

The girls graduating college now are maybe going to be living and working in this community and hopefully be a part of the solution to make North O more attractive to retain the best and brightest.”

Visit girlsincomaha.org.

Bob Boozer, basketball immortal, posthumously inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame

Bob Boozer, basketball immortal, posthumously inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame

I posted this four years ago about Bob Boozer, the best basketball player to ever come out of the state of Nebraska, on the occasion of his death at age 75. Because his playing career happened when college and pro hoops did not have anything like the media presence it has today and because he was overshadowed by some of his contemporaries, he never really got the full credit he deserved. After a stellar career at Omaha Tech High, he was a brilliant three year starter at powerhouse Kansas State, where he was a two-time consensus first-team All-American and still considered one of the four or five best players to ever hit the court for the Wildcats. He averaged a double-double in his 77-game career with 21.9 points and 10.7 rebounds. He played on the first Dream Team, the 1960 U.S. Olympic team that won gold in Rome. He enjoyed a solid NBA journeyman career that twice saw him average a double-double in scoring and rebounding for a season. In two other seasons he averaged more than 20 points a game. In his final season he was the 6th man for the Milwaukee Bucks only NBA title team. He received lots of recognition for his feats during his life and he was a member of multiple halls of fame but the most glaring omisson was his inexplicable exclusion from the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. Well, that neglect is finally being remedied this year when he will be posthumously inducted in November. It is hard to believe that someone who put up the numbers he did on very good KSU teams that won 62 games over three seasons and ended one of those regular seasons ranked No. 1, could have gone this long without inclusion in that hall. But Boozer somehow got lost in the shuffle even though he was clearly one of the greatest collegiate players of all time. Players joining him in this induction class are Mark Aguirre of DePaul, Doug Collins of Illinois State, Lionel Simmons of La Salle, Jamaal Wilkes of UCLA and Dominique Wilkins of Georgia. Good company. For him and them. Too bad Bob didn’t live to see this. If things had worked out they way they should have, he would been inducted years ago and gotten to partake in the ceremony.

I originally wrote this profile of Boozer for my Omaha Black Sports Legends Series: Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness. You can access that entire collection at this link–

https://leoadambiga.com/out-to-win-the-roots-of-greatness-…/

I also did one of the last interviws Boozer ever gave when he unexpectedly arrived back stage at the Orpheum Theater in Omaha to visit his good buddy, Bill Cosby, with whom I was in the process of wrapping up an interview. When Boozer came into the dressing room, the photographer and I stayed and we got more of a story than we ever counted on. Here is a link to that piece–

Bill Cosby on his own terms: Backstage with the comedy legend and old friend Bob Boozer

Charles Hall’s Fair Deal Cafe

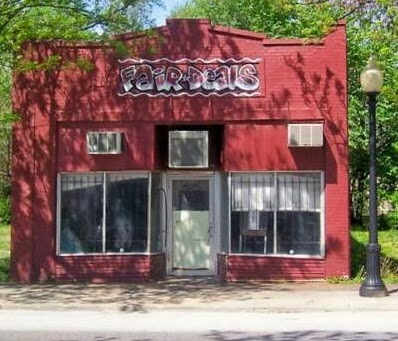

For years Omaha’s most famous purveyor of soul food was the Fair Deal Cafe. Its proprietor, the late Charles Hall, served up some righteous fare at his North 24th Street place that was also known as Omaha’s Black City Hall for being a popular spot where community leaders and concerned citizens gathered to discuss civil rights and politics. Mr. Hall and the Fair Deal are gone and sadly the building has been razed. But at least a new development on the site will be taking part of the name as a homage to the history made there and the good times had there. On my blog you can find another story I did that used the Fair Deal as the backdrop for an examination of what makes soul food, soul food. I gathered together some old school black folks to share their wisdom and passion about this cuisine. I called that piece, A Soul Food Summit.

Charles Hall’s Fair Deal Cafe

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the New Horizons and The Reader

As landmarks go, the Fair Deal Cafe doesn’t look like much. The drab exterior is distressed by age and weather. Inside, it is a plain throwback to classic diners with its formica-topped tables, tile floor, glass-encased dessert counter and tin-stamped ceiling. Like the decor, the prices seem left over from another era, with most meals costing well under $6. What it lacks in ambience, it makes up for in the quality of its food, which has been praised in newspapers from Denver to Chicago.

Owner and chef Charles Hall has made The Fair Deal the main course in Omaha for authentic soul food since the early 1950s, dishing-up delicious down home fare with a liberal dose of Southern seasoning and Midwest hospitality. Known near and far, the Fair Deal has seen some high old times in its day.

Located at 2118 No. 24th Street, the cafe is where Hall met his second wife, Audentria (Dennie), his partner at home and in business for 40 years. She died in 1997. The couple shared kitchen duties (“She bringing up breakfast and me bringing up dinner,” is how Hall puts it.) until she fell ill in 1996. These days, without his beloved wife around “looking over my shoulder and telling me what to do,” the place seems awfully empty to Hall. “It’s nothing like it used to be,” he said. In its prime, it was open dawn to midnight six days a week, and celebrities (from Bill Cosby to Ella Fitzgerald to Jesse Jackson) often passed through. When still open Sundays, it was THE meeting place for the after-church crowd. Today, it is only open for lunch and breakfast.

The place, virtually unchanged since it opened sometime in the 1940s (nobody is exactly sure when), is one of those hole-in-the-wall joints steeped in history and character. During the Civil Rights struggle it was commonly referred to as “the black city hall” for the melting pot of activists, politicos and dignitaries gathered there to hash-out issues over steaming plates of food. While not quite the bustling crossroads or nerve center it once was, a faithful crowd of blue and white collar diners still enjoy good eats and robust conversation there.

|

Fair Deal Cafe

Running the place is more of “a chore” now for Hall, whose step-grandson Troy helps out. After years of talking about selling the place, Hall is finally preparing to turn it over to new blood, although he expects to stay on awhile to break-in the new, as of now unannounced, owners. “I’m so happy,” he said. “I’ve been trying so hard and so long to sell it. I’m going to help the new owners ease into it as much as I can and teach them what I have been doing, because I want them to make it.” What will Hall do with all his new spare time? “I don’t know, but I look forward to sitting on my butt for a few months.” After years of rising at 4:30 a.m. to get a head-start on preparing grits, rice and potatoes for the cafe’s popular breakfast offerings, he can finally sleep past dawn.

The 80-year-old Hall is justifiably proud of the legacy he will leave behind. The secret to his and the cafe’s success, he said, is really no secret at all — just “hard work.” No short-cuts are taken in preparing its genuine comfort food, whose made-from-scratch favorites include greens, beans, black-eyed peas, corn bread, chops, chitlins, sirloin tips, ham-hocks, pig’s feet, ox tails and candied sweet potatoes.

In the cafe’s halcyon days, Charles and Dennie did it all together, with nary a cross word uttered between them. What was their magic? “I can’t put my finger on it except to say it was very evident we were in love,” he said. “We worked together over 40 years and we never argued. We were partners and friends and mates and lovers.” There was a time when the cafe was one of countless black-owned businesses in the district. “North 24th Street had every type of business anybody would need. Every block was jammed,” Hall recalls. After the civil unrest of the late ‘60s, many entrepreneurs pulled up stakes. But the Halls remained. “I had a going business, and just to close the doors and watch it crumble to dust didn’t seem like a reasonable idea. My wife and I managed to eke out a living. We never did get rich, but we stayed and fought the battle.” They also gave back to the community, hiring many young people as wait staff and lending money for their college studies.

Besides his service in the U.S. Army during World War II, when he was an officer in the Medical Administrative Corps assigned to China, India, Burma, Japan and the Philippines, Hall has remained a home body. Born in Horatio, Arkansas in 1920, he moved with his family to Omaha at age 4 and grew up just blocks from the cafe. “Almost all my life I have lived within a four or mile radius of this area. I didn’t plan it that way. But, in retrospect, it just felt right. It’s home,” he said. After working as a butcher, he got a job at the cafe, little knowing the owners would move away six months later to leave him with the place to run. He fell in love with both Dennie and the joint, and the rest is history. “I guess it was meant to be.”

A MOTHER’S DAY TRIBUTE Mother-Daughter Music Legacy and Inheritance: Jeanne and Carol Rogers

As musical families go, the Rogers of Omaha have few peers. The mother, Jeanne Rogers, and her three sons and one daughter have all achieved a level of notoriety in their professional music careers, including each being an individual inductee in the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame. This musical lineage has its strongest and most poignant link in the relationship between the family matriarch Jeanne and her daughter Carol Rogers. There is a powerful mother-daughter music legacy and inheritance that is powerful and only made more powerful by the fact that Jeanne today suffers from Alzheimer’s and Carol is her legal guardian. Jeanne is cared for in a nursing facility and Carol lives in her mother’s last home, where Jeanne’s presence still infuses the space. Carol and her brothers grew up in an earlier home their mother owned and it was in that music filled dwelling the siblings became initiated into the world of jazz, blues, soul and so much more. They listened in to the jam sessions and stories that their mother and her hepcat friends plied the night away with. When they were old enough the siblings made and played music of their own in that house and in talent shows and gigs around town. One by one the siblings made a name for themselves in music here and beyond Omaha. Carol’s singing career took her around the world. But when her mother fell ill she came back home to be here with her.

The following Mother’s Day Tribute is culled together from two separate stories I previously wrote: one about Carol Rogers and one about Jeanne Rogers. You can link to those stories at–

https://leoadambiga.com/?s=jeanne+rogers

A MOTHER’S DAY TRIBUTE

Mother-Daughter Music Legacy and Inheritance: Jeanne and Carol Rogers

©by Leo Adam Biga

Culled together from two previous stories I wrote

Jeanne Rogers headed a household full of music in North Omaha. The jazz singer and pianist, who suffers from dementia today, made music such a family inheritance that all of her children ended up being professional musicians like herself. Jeanne sang with area big bands and gigged as a solo jazz pianist-vocalist. A talent for music didn’t fall far from the tree, as her daughter Carol and her sons have all made a living in music and joined their mother as Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame inductees.

Carol has enjoyed a national and international singing career. And like her mom, who became an educator, Carol teaches, too. After years touring the world and making her home base in California, where she sang, recorded and taught, Carol moved back to her hometown of Omaha in 2013 in order to be near her mother. Carol feels things worked out the way they were supposed to in bringing her back home to be with her mom. She never forgets the inspiration for her life’s journey in music.

“Mom gave us music and she gave us a house full of it all the time.”

Seeing her mom’s mental capacities diminish has been difficult. Seeing her no longer recall the words to songs she sang thousands of times, like “My Funny Valentine,” cuts deeply. No one is prepared for losing a loved one, piece by piece, to the fog of Alzheimer’s. All Rogers or anyone can do is be there for the afflicted.

“I’m glad I’m close by for her sake to remind her she’s loved and hopefully, even though she doesn’t recognize me, give her a familiarity.”

Even when Jeanne became an Omaha Public Schools educator and administrator, she never left music behind. Indeed, she used it as a tool to reach kids. Carol, who as a girl used to accompany her mom to school to help her and other teachers set up their classrooms, followed in her footsteps to become a teacher herself, including running her own “kindergarten school of cool” that all her kids went through.

Carol, 61, also grew up under the influence of her grandmother Lilian Matilda Battle Hutch, She remembers her as an enterprising, tea-totaler who on a domestic worker’s wages managed buying multiple homes, subletting rooms for extra income. She sold Avon on the side.

“She could see opportunity and she was on the grind all the time. They called her ‘The General’ because she’d rifle out her demands – You comn’ in? I need you to go in the backyard and weed some stuff.’”

When Jeanne developed dementia, Carol’s trips back home increased to check on her mother and eventually take charge of her care. When Jeanne could no longer remain in her own home, Carol placed her in nursing facilities. She rests comfortably today at Douglas County Health Center. Carol’s since come back to stay. She and two of her kids reside in her mother’s former northeast Omaha home.

As a homage to her educator mother, Carol has a kitchen wall double as a chalk board with scribbled reminders and appointments.

“Chalk is how she relayed things,” Carol said of her mom.

“Music is my life. I can’t live without music.” Omaha jazz singer-pianist Jeanne Rogers recites the words as a solemn oath. As early as age 4, she said, her fascination with music began. This only child lived in her birthplace of Houston, Texas then. She’d go with her mother Matilda to Baptist church services, where young Jean was enthralled by the organist working the pedals and stops. Once, after a service, Jean recalls “noodling around” on the church piano when her mom asked, “‘What are you doing, baby?’ ‘I’m playing what the choir was singing.’ So, she tells my daddy, ‘Robert, the baby needs a piano.’ They let me pick out my piano. I still have it. All my kids learned to play on it. I just can’t get rid of it,” said Rogers, who proudly proclaims “four of my five kids are in music.”

Blessed with the ability to play by ear, she took to music easily. “I’d hear things and I’d want to play ‘em and I’d play ‘em,” she said. She took to singing too, as her alto voice “matured itself.” After moving with her family to Omaha during World War II, she indulged her passion at school (Lake Elementary) and church (Zion Baptist) and via lessons from Florentine Pinkston and Cecil Berryman. At Central High she found an ally in music teacher Elsie Howe Swanson, who “validated that talent I had. Mrs Swanson let me do my thing and I was like on Cloud Nine,” she said. Growing up, Rogers was expected by the family matriarchs to devote herself to sacred or classical music, but she far preferred the forbidden sounds of jazz or blues wafting through the neighborhood on summer nights.

“Secular was my thing,” she said. When her mother or aunt weren’t around, she’d secretly jam.

The family lived near the Dreamland Ballroom, a North 24th Street landmark whose doors and windows were opened on hot nights to cool off the joint in an era before AC. She said the music from inside “permeated the whole area. I would listen to the music coming out and, oh, I thought that was the nicest music. Mama couldn’t stop me from listening to what the bands were playing. That’s the kind of music I wanted to play. I wanted to play with a band. I was told, ‘Oh, no, you can’t do that. Nothing but trash is up in that ballroom. There’s no need your going to college if that’s all you want to play.’ But, hey, I finally ended up doing what I wanted to do. And playing music in the nightclubs paid my way through college.”

Do-gooders’ “hoity-toity,” attitude rubbed her the wrong way, especially when she “found out folks in church were doing the same thing folks in the street were.”

Rogers, who became a mother quite young, bit at the first chance to live out her music dream. When someone told her local bandleader Cliff Dudley was looking for a singer she auditioned and won the job. “That’s how I got into the singing,” she said. “I was scared to death.” She sang standard ballads of the day and would “do a little blues.” Later, when the band’s pianist dropped out, she took over for him. “And that’s how I got started playing with the band.” Her fellow musicians included a young Luigi Waites on drums. The group played all over town. She later formed her own jazz trio. She’d started college at then-Omaha University, but when the chance to tour came up, she left school and put her kids in her mother’s care.

The reality of life on the road didn’t live up to the glamour she’d imagined. “That’s a drag,” she said of living out of suitcases. Besides, she added, “I missed my kids.” Letters from home let her know how much she was missed and that her mother couldn’t handle the kids anymore. “She needed me,” Rogers said. “I mean, there were five kids, three of them hard-headed boys. So I came back home.”

The Jewell Building once housed the Dreamland Ballroom

She resumed college, resigned to getting an education degree. “All I wanted to do was play the piano in the band. But I ended up doing what I had to do,” she said.

To support her studies she still played gigs at local clubs. And she nurtured her kids’ and their friends’ love of music by opening up the family home to anyone who wanted to play, turning it into a kind of informal music studio/academy.

“My house on Bristol Street was the house where everybody’s kids came to play music,” she said. Her twin boys Ronnie and Donnie Beck practiced with their bands upstairs while younger brother Keith Rogers’ band jammed downstairs. Their sister, singer Carol Rogers, imitated soul songstresses. Some youths who made music there went on to fine careers, including the late guitarist Billy Rogers (no relation). Ronnie played with Tower of Power and still works as a drummer-singer with top artists. Donnie left Omaha with drummer Buddy Miles and now works as a studio musician and sideman. Keith is a veteran music producer. His twin sister Carol performed with Preston Love and Sergio Mendes, among other greats.

Years later Carol recalled growing up in that bustling household on Bristol Street where she couldn’t help but be immersed in music between her siblings rehearsing and her mother and her musician friends jamming. That 24-7 creative hub imbued her with a love for performing.

“In the summertime it was just crawling with people because my brothers had instruments. In the basement they were always practicing. It got so I couldn’t study without a lot of noise. I still sleep with noise. If you didn’t get home in time and there was food you didn’t eat because the people who were in the house ate. It was first come-first served. That used to make me mad.

“But there was music. Folks would come. A typical weekend, Billy Rogers, not any relation, would come and jam. Everybody who was anybody came in and jammed. I didn’t know who they all were, all I knew there was always noise.”

She confirms the Rogers’ home was the place neighborhood kids congregated.

“My mother would boast that kids’ parents would say, ‘Why is my child always at your house?’ Because they’re welcome and there’s music. And so that’s just the way it was. That’s the way I remember the house. I didn’t have to go looking for people or excitement – it came to the house. There was always something going on.”

Her mother grew up near enough the old Dreamland Ballroom to hear the intoxicating rhythms of the black music greats who played there.

“That’s when she got bitten by the jazz bug,” Carol said. “She would go to sleep hearing the music playing at Dreamland.”

Carol enjoyed an even more intimate relationship with music because of the nightclub atmosphere Jeanne orchestrated at home.

“Oh, these jam sessions that mama would have. All I know is we would have to be whisked to bed. Of course, we could hear them at night. They would never go past 10 or so. Occasionally she would let us come down and just watch, which was a privilege. There’d be Basie Givens, who she played with forever, Clean Head Base, Cliff Dudley, the names go on of all the people who would come in. And they’d just jam, and she’d sing and play piano.

“It was a big party and to-do thing at the house. I would go to sleep hearing her and her friends play the jam sessions. Coming downstairs in the morning there was always somebody crashed out on the floor.

Carol didn’t have plans to come back to Omaha but when her mother’s illness progressed, she had no choice.

“I knew I had to come back for my mom because I became her guardian.”

Seeing her mom’s mental capacities diminish has been difficult. Seeing her no longer recall the words to songs she sang thousands of times, like “My Funny Valentine,” cuts deeply. No one is prepared for losing a loved one, piece by piece, to the fog of Alzheimer’s. All Rogers or anyone can do is be there for the afflicted.

“I’m glad I’m close by for her sake to remind her she’s loved and hopefully, even though she doesn’t recognize me, give her a familiarity.”

Two of Carol’s four children live with her in Omaha and they, too, have inherited the musical gene and give Jeannie yet more family and love to be around.

2016 North Omaha Summer Arts schedule announced

2016 North Omaha Summer Arts schedule announced

We are delighted to announce that this June marks the 6th year for North Omaha Summer Arts (NOSA), a free, grassroots, community-based arts festival. Our mission is to bring the diverse experience of art in all forms to the community of North Omaha.

NOSA classes and events are open to everyone.

2016 Highlights include:

Gospel Concert in the Park

Saturday, June 18

5 to 7:30 pm

Miller Park

Featuring soloists, ensembles and choirs performing a mix of gospel styles. Free hot dogs and lemonade will be served. Bring a blanket or a chair and prepare to be inspired.

Women’s Writing Classes and Retreats

Wednesdays, June 1 through July 27

5:30 dinner followed by 6 to 8 pm class

Trinity Lutheran Church on corner of 30th and Redick.

This summer we focus on “Getting Published.”

Facilitator Kim Louise is a playwright, best-selling romance novelist and veteran workshop presenter who guides participants in finding their inner writer’s voice.

Art and Gardening Class

Saturday, July 9

10:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m.

Florence Branch Library

Combine your passion for making and growing things in a fun-filled session painting art on clay pots and planting flowers that attract pollinators.

Pop Up Art

July dates, times and venues to be announced.

Pop Up Art happenings around North Omaha will give people of all ages fun opportunities to unleash their creativity and express themselves through different mediums.

Arts Crawl

Friday, August 12

6 to 9 pm

Reception at Charles Washington Branch Library 5:30-6:30 pm.

This walkable, continuous art show showcases the diverse work of emerging and established artists at venues on or near North 30th Street. The Crawl starts at the Metropolitan Community College Fort Omaha campus Mule Barn building and ends at the North Heartland Family Service with Church of the Resurrection, Nelson Mandela School and Trinity Lutheran in between. Walk or drive to view art in a wide variety of mediums, to watch visual art demonstrations and to speak with artists about their practice. Enjoy live music at some venues.

Free food and refreshments at each stop.

Watch for NOSA announcements through the spring and summer about each of these arts programs and events. Please share with friends and family. Let’s make this a beautiful art-filled season.

Like/follow NOSA on Facebook–

https://www.facebook.com/NorthOmahaSummerArts/?fref=ts

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1012756932152193/

For more information, to be a participating artist or to partner with NOSA, call 402-502-4669.

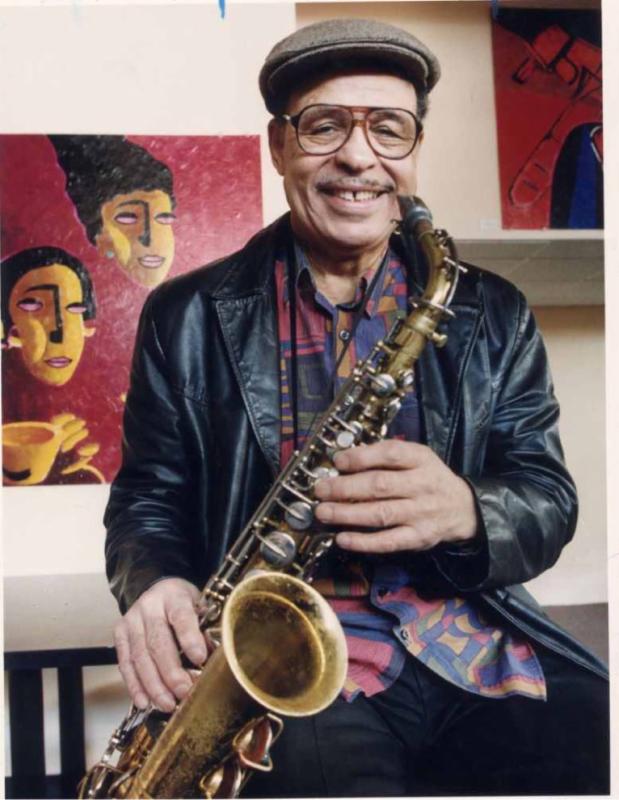

Preston Love: A Tribute to Omaha’s Late Hepcat King

Preston Love: A Tribute to Omaha’s Late Hepcat king

©by Leo Adam Biga

An early January evening at the Bistro finds diners luxuriating in the richly textured tone and sweetly bended notes of flutist-saxophonist Preston Love Sr., the eternal Omaha hipster…

By eleven, the crowd’s thinned, but the 75-year-old jams on, holding the night owls with his masterful playing and magnetic personality. His tight four-piece ensemble expertly interprets classic jazz, swing and blues tunes he helped immortalize as a Golden Era lead alto sax player, band leader and arranger.

Love lives for moments like these, when his band really grooves and the crowd really digs it:

“There’s no fulfillment…like playing in a great musical environment. It’s spiritual. It’s everything. Anything less than that is unacceptable. If you strike that responsive chord in an audience, they’ll get it too – with that beat and that feeling and that rhythm. Those vibes are in turn transmitted to the band, and inspire the band.”

For him, music never gets tired, never grows old. More than a livelihood, it’s his means self-expression, his life, his calling.

Music’s sustained during a varied career. Whether rapping with the audience in his slightly barbed, anecdotal way or soaring on a fluid solo, this vibrant man and consummate musician is totally at home on stage.

Love’s let-it-all-hang-out persona is matched by his tell-it-like-it-is style as a music columnist, classroom lecturer and public radio host. He fiercely champions jazz and blues as significant, distinctly African-American art forms and cultural inheritances. This direct inheritor and accomplished interpreter feels bound to protect its faithful presentation and to rail against its misrepresentation.

His autobiography, “A Thousand Honey Creeks Later,” gave him his largest forum and career capstone.

“It’s my story and it’s my legacy to my progeny.”

He’s long criticized others appropriating the music from its black roots and reinventing it as something it’s not.

“It’s written in protest. I’m an angry man. I started my autobiography…in dissatisfaction with whats transpired in America in the music business and, of course, with the racial thing that’s still very prevalent. Blacks have almost been eliminated from their own art. That’s unreal. False. Fraudulent.

“They’re passing it off as something it isn’t. It’s spurious jazz. Synthetic. Third-rate. Others are going to play our music, and in many cases play it very well. We don’t own any exclusivity on it. But it’s still black music, and all the great styles, all the great developments, have been black, whether they want to admit it or not. So why shouldn’t we protect our art?

“When you muddy the water or disturb the trend or tell the truth even, you make people angry, because they’d rather leave the status quo as it is. But I’m not afraid of the repercussions. I will fight for my people’s music and its preservation.”

When he gets on a roll like this, his intense speaking style belongs both to the bandstand and the pulpit. His dulcet voice carries the inflection and intonation of an improvisational riff and the bravura of an evangelical sermon, rising in a brimstone rant before falling to a confessional whisper.

Love feels his far-flung experience uniquely qualifies him to address the American black music scene of his generation.

“The fact that mine’s been a different, unlikely and multifaceted career is why publishers became interested in my book.”

From a young age, he heard the period’s great black performers on the family radio and phonograph and hung-out on then teeming North 24th Street to catch a glimpse and an autograph of visiting artists playing the fabled Dreamland Ballroom and staying at nearby rooming houses and hotels.

“Twenty-fourth street was the total hub of the black neighborhood here. This street abounded with great players of this art form.”

By his teens, he was old enough to see his idols perform at the Orpheum and Dreamland.

“All of the great black geniuses of my time played that ballroom. Jazz was all black then…and here were people you admired and worshiped, and now you were standing two feet from them and could talk to them and hear their artistry. To hear the harmony of those black musicians, with that sorrowful, plaintive thing that only blacks have, and a lot of blacks don’t get it. That pain in their playing. That indefinable, elusive blue note. That’s what jazz is.

“The Benny Goodmans and those guys never got it.”

The music once heard from every street corner, bar, restaurant, club has been silenced or replaced by discordant new sounds.

That loss hurts Love because he remembers well when Omaha was a major music center, supporting many big bands and clubs and drawing musicians from around the region. It was a launching ground for him and many others.

“This was like the Triple A of baseball for black music. The next stop was the big leagues.”

He regrets many young blacks are uninformed about this vital part of their heritage.

“If I were to be remembered for some contribution, it would be to remind people what’s going on today with the black youth and their rap…has nothing to do with their history. It’s a renunciation of their true music — blues, rhythm and blues and jazz.”

He taught himself to play, picking up pointers from veteran musicians and from masters whose recordings he listened to “over and over again.” Late night jam sessions at the Blue Room and other venues were his proving ground, He began seeing music as a way out.

“There was no escape for blacks from poverty and obscurity except through show business. I’d listen to the radio’s late night coast-to-coast broadcasts of those great bands and go to sleep and just dream of going to New York to play the Cotton Club and dream of playing the Grand Terrace in Chicago. I dreamed of someday making it – and I did make it. Everything else in my life would be anticlimactic, because I realized my dream.”

He made himself an accomplished enough player that Count Basie hired him to play with his band.

“I had the natural gift for sound – a good tone – which is important. Some people never have it. I was self-motivated. No one had to make me practice…And being good at mathematics, I was able to read music with the very least instruction.”

Music keeps him youthful. He’s no “moldy fig,” the term boppers coined to describe musicians out-of-step with the times.

He burns with stage presence with his insouciant smile and his patter between sets that combines jive, scat and stand-up. Then there’s his serious side. He coaxes a smooth, bittersweet tone from the sax and flute developed over a lifetime.

If nothing else, he’s endured, surviving fads and changing musical tastes, adapting from the big band swing era to Motown to funk. He’s risen above the neglect he felt in his own hometown to keep right on playing and speaking his mind.

“I refuse to be an ancient fossil or an anachronism, I am eternally vital. I am energetic, indefatigable. It’s just my credo and the way I am as a person.”

A Soul Man to the end.

“I think the term ‘soul’ was first applied to us as a people to describe the feeling of our expressions and attitudes and language. It means a lot of heart and a depth of feeling. It refers to the pathos in our expression, musically and colloquially.”

He says a genius for spontaneity is a hallmark of blacks in creative endeavors — from music and dancing to cooking.

“The limitations we lived under gave birth to these embellishments and improvisations. That’s what we did. We were masters of embellishment.”

He left his hometown many times, but always came back. Back to where his dream first took flight and came true. Back to the mistress – music – that still holds him enthralled. To be our conscience, guide, inspiration.

That January night at the Bistro, a beaming Love, gold horn slung over one shoulder, tells his audience, “I love this. I look forward coming to work. Preston Love’s an alto player, and you want to hear him play alto, right? Listen to this.” Supplying the downbeat, he fills the room with the golden strain of “Mr. Saturday Night.” Play on, Mr. Saturday Night, play on.

Talking it out: Inclusive Communities makes hard conversations the featured menu item at Omaha Table Talk

My, how Omaha loves to talk about race and then not. Everyone has an opinion on race and the myriad issues bound up in it. Most of us save our opinions on this topic for private, close company encounters with friends and family. Only few dare to expose their beliefs in public or among strangers. Inclusive Communities organizes a forum called Omaha Table Talk for discussiing race and other sensitive subjects in small group settings led by a facililator over a meal. It is a safe meeting ground where folks can say what’s on their mind and hear another point of view over the communal experience of breaking bread. I am not sure what all this talking accomplishes in the final analysis since the people predisposed to participate in such forums are generally of like minds in terms of supporting inclusivity and respecting diversity. But I suppose there’s always a chance of learning something new and receiving a if-you-could-walk-in-my-shoes lesson or two that might expand your thinking and perception. For the voiceless masses, however, I think race remains an individually lived experience that only really gets expressed in our heads and among our small inner circle. But I suspect not much then either, except when we see something that angers us as a racially motivated hate crime or a blatant case of racism and discrimination. Otherwise, most of us keep a lid on it, lest we blow up and say something we regret because it might be misunderstood and taken as an insult or offense. The dichotomy of these times is that we live in an Anything Goes era within a Politically Correct culture. Therefore, we are encouraged to say what is on our mind and not. And thus the silent majority plods, often gitting their teeth, while talking heads let out torrents of vitriol or rhetoric.

Talking it out: Inclusive Communities makes hard conversations the featured menu item at Omaha Table Talk

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the January-February 2016 issue of Omaha Magazine

When Catholic Charities of Omaha looked for somebody to take over its open race and identity forum, Omaha Table Talk, it found the right host in Inclusive Communities.

Formerly a chapter of the National Conference for Christians and Jews, the human relations organization started in 1938 to overcome racial and identity divisions. While the name it goes by today may be unfamiliar, the work Inclusive Communities does building bridges of understanding in order to surmount bigotry remains core to its mission. Many IC programs today are youth focused and happen in schools and residential camp settings. IC also takes programs into workplaces.

Table Talk became one of its community programs in 2012-2013. Where Table Talk used to convene people once a year around dinners in private homes to dialogue about black-white relations, under new leadership it’s evolved into a monthly event in public spaces tackling rotating topics. Participation is by registration only.

The November session dug into law enforcement and community. The annual interfaith dialogue happens Jan. 12. Reproductive rights and sex education is on tap March 22 and human trafficking is on the docket April 22,

The annual Main Event on February 9 is held at 20 metro area locations. As always, race and identity will be on the menu. Omaha North High Spanish teacher Alejandro García, a native of Spain, attended the October 13 Ethnic Potluck Table Talk and came away impressed with the exchanges that occurred.

“I had the opportunity to engage in very open conversations with people that shared amazing life stories,” he says. “I am drawn to things that relate to diversity, integration and tolerance. Even though I think I have a pretty open mind and I consider myself pretty tolerant I know this is an illusion. We all have big prejudices and fears of difference. So I think these opportunities allow us to get rid of preconceptions.”

New IC executive director Maggie Wood appreciates the platform Table Talk affords people to share their own stories and to learn other people’s stories.

“It’s exciting to be a part of a youth-driven organization that’s really looking to make a difference in the world. It’s about putting the mic in people’s hands and giving them the opportunity to voice what they feel is important.

“What I think Omaha Table Talk does is really give us the opportunity to have conversations we wouldn’t normally have in a structured way that helps us to think about other people’s ideas. Nobody else in town is doing this real conversation about tough topics.”

“These conversations do not happen in day-to-day life, at least not in my environment,” Garcia says. “I see people avoiding these topics. They find it uncomfortable and they are never in the mood to speak up for the things they might consider to be wrong and that need to be fixed. If you don’t talk about the problems in your community, you will never fix them.”

“The really beautiful thing about Omaha Table Talk,” Wood says, “is it really brings about hope for people who see how more alike we are than different.”

Maggie Wood

Operations director Krystal Boose says, “What makes Inclusive Communities special is we are very good at creating a safe space. It’s so interesting to see how quickly people open up about their identities. Part of it is the way we utilize our volunteers to help navigate and guide those conversations.”

Gabriela Martinez, who participated in IC youth programs, now helps coordinate Table Talk. She says no two conversations are alike. “They’re different at every site. You have a different group of people every single place with different facilitators. We have a set of guided questions but the conversation goes where people want to take it.”

Gabriela Martinez

Wood says the whole endeavor is quid pro quo.

“We need the participants as much as the participants need us. We need individuals to be there to help us drive the conversation in Omaha starting around the table. We’re now looking at how do we put the tools in participants’ hands to go out and advocate for the change they want to see.”

She says IC can connect people with organizations “doing work that’s important to them.”

IC staff feel Table Talk dialogues feed social capital.

“We’re planting seeds for future conversations” and “we’re giving a voice to a lot of people who think they don’t have one,” Martinez says.

“It’s not good enough to just empower them and give them voices and then release them into a world that’s not inclusive and shuts them back down,” Boose says. “It’s our responsibility to help create workplaces for them that value inclusivity and diversity.” Martinez, a recent Creighton University graduate, says milllennials like her “want and expect diversity and inclusion in workplaces – it’s not optional.”

Krsytal Boose

Boose says growing participation, including big turnouts for last summer’s North and South Omaha Table Talks and new community partners, “screams that Omaha is hungry for these conversations.”

Organizers say you don’t have to be a social justice warrior either to participate. Just come with an open mind.

Main Event registration closes January 15.

The IC Humanitarian Brunch is March 19 at Ramada Plaza Center. Keynote speaker is Omaha native and Bernie Sanders press secretary Symone Sanders. For details on these events and other programs, visit http://www.inclusive-communities.org/.

Play considers Northside black history through eyes of Omaha Star publisher Mildred Bown

Upcoming Great Plains Theatre Conference PlayFest productions at nontraditional sites examine North Omaha themes as part of this year’s Neighborhood Tapestries. On May 29 the one-woman play Northside Carnation, both written and performed by Denise Chapman, looks at a pivotal night through the eyes of Omaha Star icon Mildred Brown at the Elks Lidge. On May 31 Leftovers, by Josh Wilder and featuring a deep Omaha cast, explores the dynamics of inner city black family life outside the home of the late activist-journalist Charles B. Washington. Performances are free.

Play considers Northside black history through eyes of Omaha Star publisher Mildred Bown

Denise Chapman portrays the community advocate on pivotal night in 1969

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

As North Omaha Neighborhood Tapestries returns for the Great Plains Theatre Conference’s free PlayFest bill, two community icons take center stage as subject and setting.

En route to making her Omaha Star newspaper an institution in the African-American community, the late publisher Mildred Brown became one herself. Through the advocacy role she and her paper played, Brown intersected with every current affecting black life here from the 1930s on. That makes her an apt prism through which to view a slice of life in North Omaha in the new one-woman play Northside Carnation.

This work of historical fiction written by Omaha theater artist Denise Chapman will premiere Sunday, May 29 at the Elks Lodge, 2420 Lake Street. The private social club just north of the historic Star building was a familiar spot for Brown. It also has resonance for Chapman as two generations of her family have been members. Chapman will portray Brown in the piece.

Directing the 7:30 p.m. production will be Nebraska Theatre Caravan general manger Lara Marsh.

An exhibition of historic North Omaha images will be on display next door at the Carver Bank. A show featuring art by North Omaha youth will also be on view at the nearby Union for Contemporary Art.

Two nights later another play, Leftovers, by Josh Wilder of Philadelphia, explores the dynamics of an inner city black family in a outdoor production at the site of the home of the late Omaha activist journalist Charles B. Washington. The Tuesday, May 31 performance outside the vacant, soon-to-be-razed house, 2402 North 25th Street, will star locals D. Kevin Williams, Echelle Childers and others. Levy Lee Simon of Los Angeles will direct.

Just as Washington was a surrogate father and mentor to many in North O, Brown was that community’s symbolic matriarch.

Denise Chapman

Chapman says she grew up with “an awareness” of Brown’s larger-than-life imprint and of the paper’s vital voice in the community but it was only until she researched the play she realized their full impact.

“She was definitely a very important figure. She had a very strong presence in North Omaha and on 24th Street. I was not aware of how strong that presence was and how deep that influence ran. She was really savvy and reserved all of her resources to hold space and to make space for people in her community – fighting for justice. insisting on basic human rights, providing jobs, putting people through school.

“She really was a force that could not be denied. The thing I most admire was her let’s-make-it-happen approach and her figuring out how to be a black woman in a very white, male-dominated world.”

Brown was one of only a few black female publishers in the nation. Even after her 1989 death, the Star remained a black woman enterprise under her niece, Marguerita Washington, who succeeded her as publisher. Washington ran it until falling ill last year. She died in February. The paper continues printing with a mostly black female editorial and advertising staff.

Chapman’s play is set at a pivot point in North O history. The 1969 fatal police shooting of Vivian Strong sparked rioting that destroyed much of North’s 24th “Street of Dreams.” As civil unrest breaks out, Brown is torn over what to put on the front page of the next edition.

“She’s trying her best to find positive things to say even in times of toil,” Chapman says. “She speaks out reminders of what’s good to help reground and recenter when everything feels like it’s upside down. It’s this moment in time and it’s really about what happens when a community implodes but never fully heals.

“All the parallels between what was going on then and what we see happening now were so strong it felt like a compelling moment in time to tell this story. It’s scary and sad but also currently repeating itself. I feel like there are blocks of 24th Street with vacant lots and buildings irectly connected to that last implosion.”

Mildred Brown and the Omaha Star offices

During the course of the evening, Chapman has Brown recall her support of the 1950s civil rights group the De Porres Club and a battle it waged for equal job opportunities. Chapman, as Brown, remembers touchstone figures and places from North O’s past, including Whitney Young, Preston Love Sr., Charles B. Washington, the Dreamland Ballroom and the once teeming North 24th Street corridor.

“There’s a thing she says in the play that questions all the work they did in the ’50s and yet in ’69 we’re still at this place of implosion,” Chapman says. “That’s the space that the play lives in.”

To facilitate this flood of memories Chapman hit upon the device of a fictional young woman with Brown that pivotal night.

“I have imagined a young lady with her this evening Mildred is finalizing the front page of the paper and their conversations take us to different points in time. The piece is really about using her life and her work as a lens and as a way to look at 24th Street and some of the cultural history and struggle the district has gone through.”

Chapman has been studying mannerisms of Brown. But she’s not as concerned with duplicating the way Brown spoke or walked, for instance, as she is capturing the essence of her impassioned nature.

“Her spirit, her drive, her energy and her tenacity are the things I’m tapping into as an actor to create this version of her. I think you will feel her force when I speak the actual words she said in support of the Omaha and Council Bluffs Railway and Bridge Company boycott. She did not pull punches.”

Chapman acknowledges taking on a character who represented so much to so many intimidated her until she found her way into Brown.

“When I first approached this piece I was a little hesitant because she was this strong figure whose work has a strong legacy in the community. I was almost a little afraid to dive in. But during the research and what-if process of sitting with her and in her I found this human being who had really big dreams and passions. But her efforts were never just about her. The work she did was always about uplifting her people and fighting for justice and making pathways for young people towards education and doing better and celebrating every beautiful accomplishment that happened along the way.”

Chapman found appealing Brown’s policy to not print crime news. “Because of that the Star has kept for us all of these beautiful every day moments of black life – from model families to young people getting their degrees and coming back home for jobs to social clubs. All of these every day kind of reminders that we’re just people.”

For the complete theater conference schedule, visit https://webapps.mccneb.edu/gptc/.

Crime and punishment questions still surround 1970 killing that sent Omaha Two to life in prison

Mondo we Langa’s recent death in prison leaves Ed Poindexter still fighting for his freedom

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the April 2016 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

When Mondo we Langa died at age 68 in the Nebraska State Penitentiary last month, he’d served 45 years for a crime he always maintained he did not commit. The former David Rice, a poet and artist, was found guilty, along with fellow Black Panther Ed Poindexter, in the 1970 suitcase bomb murder of Omaha police officer Larry Minard. With his reputed accomplice now gone, Poindexter remains in prison, still asserting his own innocence.

Poindexter and we Langa have been portrayed by sympathetic attorneys, social justice watchdogs and journalists as wrongfully convicted victims framed by overzealous officials. The argument goes the two were found guilty by a nearly all-white jury and a stacked criminal justice system for their militant black nationalist affiliations and inflammatory words rather than hard evidence against them. Supporters call them the Omaha Two in reference to a supposed population of American political prisoners incarcerated for their beliefs.

The crucial witness against the pair, Duane Peak, is the linchpin in the case. His testimony implicated them despite his contradictory statements. we Landa and Poindexter dispute his assertions. Today, Peak lives under an assumed name in a different state.

Two writers with Omaha ties who’ve trained a sharp eye on the case are Elena Carter and Michael Richardson. Carter, an Iowa University creative writing graduate student, spent months researching and writing her in-depth February article for BuzzFeed. She laid out the convoluted evidentiary trail that went cold decades ago, though subsequent discoveries cast doubt on the official record of events. Just not enough to compel a judge to order a new trial.

Richardson has written extensively on the case since 2007 for various online sites, including Examiner.com. He lives in Belize, Central America.

Both writers have immersed themselves in trial transcripts and related materials. They visited we Langa and Poindexter in prison. Their research has taken them to various witnesses, experts and advocates.

For Carter, it’s a legacy project. Her father, Earl Sandy Carter, was with the VISTA federal anti-poverty program (now part of AmeriCorps) here in the early 1970s. Richardson, a fellow VISTA worker in Omaha, says he “came of age politically and socially,” much as Carter did, during all the fervor” of civil rights and anti-war counterculture. Ironically, they did things like free food programs in the black community closely resembling what the Panthers did; only as whites they largely escaped the harassment and suspicion of their grassroots black counterparts.

Earl Sandy Carter edited a newsletter, Down on the Ground, we Langa and Poindexter contributed to. Richardson knew we Langa from Omaha City Council meetings they attended. With their shared liberal leanings, Richardson and Carter teamed to cover the trial as citizen journalists, co-writing a piece published in the Omaha Star.

Elena Carter grew up unaware of the case. Then her father mentioned it as possible subject matter for her to explore. Intrigued to retrace his activism amid tragic events he reported on, she took the bait.

“The more I read about it the more I wanted to look into this very complicated, fascinating case,” she says. “Everything I read kept reinforcing they were innocent – that this was a clear wrongful conviction. Until now, my writing has been personal – poetry and memoir. This was my first journalistic piece. This was different for me in terms of the responsibility I felt to get everything right and do the story justice.”

That sense of responsibility increased upon meeting we Langa and Poindexter on separate prison visits. They were no longer abstractions, symbols or martyrs but real people grown old behind bars.

“It was a lot more pressure than I usually feel while writing, but also a really great privilege for them to trust me to write about them,” she says.

Pictured here at the headquarters of the National Committee to Combat Fascism are Ed Poindexter, Duane Peak and Dorothy Stubblefield. The headquarters of the United Front Against Fascism, formerly the Omaha Black Panther Party and along with the National Committee to Combat Fascism, were located at 3508 N. 24th St. in the Kountze Place neighborhood.

She visited we Langa three times, the last two in the prison infirmary, where he was treated for advanced respiratory disease. Though confined to a wheelchair and laboring to breathe, she found him “eccentric, super smart, optimistic, exuberant and still in high spirits – singing, reciting poems,” adding, “He wasn’t in denial he was dying, yet he seemed really determined to live.”

She says, “He was on my mind for a year and a half – it did become highly personal.” She found both men “even-keeled but certainly angry at the situation they found themselves in.” She adds, “Mondo said he didn’t have any anger toward Duane Peak. He saw him as a really vulnerable kid scared for his family. But he did express anger toward the system.”

Richardson, who applied for Conscientious Objector status during the Vietnam War, never forgot the case. Ten years ago he began reexamining it. Hundreds of articles have followed.

“The more I learned, the more I doubted the official version of the case,” he says. “I reached the conclusion the men were innocent after about a year of my research. It was the testimony of forensic audiologist Tom Owen that Duane Peak did not make the 911 call (that drew Officer Minard to a vacant house where the bomb detonated) that made me understand there had been false testimony at the trial. My belief in their innocence has only grown over the years as I learned more about the case.

“Also, my visits and correspondence with both men helped shape my beliefs. Mondo was unflinching with his candor and I came to have a profound respect for his personal integrity. Their stories have never changed. Their denials seem very genuine to me. The deceit of the police agencies has slowly been revealed with disclosures over the years, although much remains hidden or destroyed.”

Ed Poindexter and Mondo we Langa (formerly David Rice) well into their prison terms

There are as many conspiracy theories about the case as folks making it a cause. Everyone has a scapegoat and boogeyman. Richardson and Carter don’t agree on everything but they do agree the men did not receive a fair trial due to mishandled, concealed, even planted evidence. They point to inconsistent testimony from key witnesses. They see patterns of systemic, targeted prejudice against the Panthers that created an environment for police and prosecutorial misconduct.

The murder of a white cop who was a husband and father and the conviction of two black men who used militant language resonates with recent incidents that sparked the Black Lives Matter movement.

Considerable legal and social justice resources have been brought to bear on the case in an effort to have it reopened and retried.

As Elena Carter wrote, “we Langa and Poindexter’s case has penetrated every level of the criminal justice system, from local officials to former governors to the FBI to the Supreme Court.” Yet, we Langa languished in prison and died there.

Carter reported we Langa’s best chance for a new trial came in 1974, “when he filed an appeal in federal district court, arguing the dynamite and blasting caps recovered from his home during a police search for Duane Peak should never have been received in evidence” because the officers who entered his home “had no probable cause Duane was there.” Contravening and contradictory court rulings affecting that decision have apparently had a chilling effect on any judge taking the case on.

She and Richardson surmise no judicial official in this conservative state wants to overturn or commute a convicted cop killer’s sentence.

“Sadly, when you talk to people about a dead policeman and Black Panthers, the conversation sort of stops,” Richardson says.

“I don’t think enough people know about this case,” says Carter. “Why this case hasn’t been taken as seriously as it should perplexes and frustrates me.”

She and Richardson believe the fact the Omaha Panthers were not prominent in the party nationally has kept their case low profile. The Washington Post did report on it decades ago and Carter says, “I feel like that’s the only time a serious national publication had put it out there they could be innocent.” Until her story.

A documentary examined the case. Noted attorney Lennox Hinds has been involved in the defense effort.

Locally, Ben Gray made the case a frequent topic on KETV’s Kaleiidoscope. Other local champions have included State Sen. Ernie Chambers. Then-Gov. Bob Kerrey was prepared to pardon we Langa, but the prisoner refused on the grounds it would be an admission of guilt. Nebraskans for Peace and others keep the case before officials.

“I would say the Omaha Two case shows the critical need for the news media to monitor the police and courts,” says Richardson.

No major exoneration projects or attorneys have adopted the case,

“I’m not entirely sure why that is after all these years,” Carter says. “I don’t know what their reluctance would be looking into this case more.”

Most observers speculate nothing will change unless or until someone comes forward with dramatic new evidence.

Carter hopes “something more could be done for Ed (Poindexter) at this point.” Barring action by the Nebraska Board of Pardons or Gov. Pete Ricketts, the 71-year-old inmate likely faces the same fate as his late friend given the history of denied appeals attending the case.

“Mondo told me he was paying a debt he did not owe,” Richardson says. “Poindexter deserves a fresh look at his case. I believe in their innocence. They were guilty of rhetoric, not murder.”

View Carter’s story at http://www.buzzfeed.com/e6carter/the-omaha-two# and Richardson’s stories at http://www.examiner.com/topic/omaha-two-1.