Archive

Keeper of the Flame: Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner Ted Kooser

Ted Kooser was already well into his term as U.S. Poet Laureate and had recently been awarded the Pulitzer Prize when I wrote two stories about him. This is the first. It appeared in the New Horizons, and it ‘s based on an interview I did with him at his home in Garland, Neb. Whenever I interview and profile a writer, particularly one as skilled as Kooser, I feel added pressure to get things right. He helped make me feel comfortable with his amiable, homespun way, although I never once forgot I was speaking to a master. The subsequent piece I did on him is also posted on this site.

Keeper of the Flame: Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner Ted Kooser

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Forget for the moment Ted Kooser is the reigning U.S. Poet Laureate or a 2005 Pulitzer Prize winner. Imagine he’s one of those quixotic Nebraska figures you read about. A bespectacled, bookish fellow living on a spread in the middle of nowhere, dutifully plying his well-honed craft in near obscurity for many years. Only, fame has lately found this venerable artist, who despite his recent celebrity and the rounds of interviews and public appearances it brings, still maintains his long-held schedule of writing each morning at 4:30. Away from the hurly-burly grind, the writer’s life unfolds in quiet, well-measured paces at his acreage home recessed below a dirt road outside Garland, Neb. There, the placid Kooser, an actual rebel at heart, pens acclaimed poetry about the extraordinariness of ordinary things.

Once you get off I-80 onto US 34, it’s all sky and field. Wild flowers, weeds and tall grasses encroach on the shoulders and provide variety to the patches of corn and soy bean sprawled flat to the horizon. The occasional farm house looms up in stark relief, shielded by a wind break of trees. The power lines strung between wooden poles every-so-many-yards are guideposts to what civilization lies out here.

Kooser’s off-the-beaten-track, tucked-away place is just the sort of retreat you’d envision for an intellectual whose finely rendered thoughts and words require the concentration only solitude can provide. More than that, this sanctuary is situated right in the thicket of the every day life he celebrates, which the title of his book, Local Wonders, so aptly captures. In his elegies to nature, to ritual, to work, and to all things taken for granted, his close observations and precise descriptions elevate the seemingly prosaic to high art or a state of grace.

The acreage he shares with his wife Kathy Rutledge includes a modest house, a red barn, a corn crib, a gazebo he built and a series of tin-roofed sheds variously containing a shop for his handyman work, an artist’s studio for his painting and a reading salon for raiding bookcases brimming with volumes of poetry and literature.

The pond at the bottom of the property is stocked with bluegill and bass.

His dogs are the first to greet you. Their insistent barking is what passes for an alarm system in these rural digs. Kooser, 66, comes out of the house to greet his visitors, looking just like his picture. He’s a small, exact man with a large head and an Alfred E. Newman face that is honest, wise and ironic. He has the reserved, amiable, put-on-no-airs manner of a native Midwesterner, which the Ames-Iowa born and raised Kooser most certainly is.

Comfortably and crisply outfitted in blue jeans, white shirt and brown shoes, he leads us to his shed-turned-library and slides into a chair to talk poetry in his cracklebarrel manner. A pot-bellied stove divides the single-room structure. The first thing you note is how he doesn’t play off the lofty honors and titles that have come his way the last two years. He is down to earth. Sitting with him on that June afternoon you almost forget he’s this country’s preeminent poet. That is until he begins talking about the form, his answers revealing the inner workings of a genuine American original and master.

Kooser, who teaches a graduate-level tutorial class in poetry at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, patiently responds to his visitors’ questions like the generous teacher he is. His well-articulated passion for his medium and for his work, a quality that makes him a superb advocate for his art, are evident throughout a two-hour conversation that ranges from the nature of poetry to his own creative process.

So, what is poetry?

“I like to think it is the record of a discovery. And the discovery can either be something in your environment or something you discover in the process of writing, like in new language. You basically record that discovery and then give it to the reader. And then the reader discovers something from it,” he said. “There’s a kind of kaleidoscope called a taleidoscope. It doesn’t have the glass chips on the end. It has a lens and I turn it on you and however ordinary the thing is it becomes quite magical because of the mirrors. And that’s the device of the poem. The poet turns it on something and makes it special and gives it — the image — to the reader.”

There is a tradition in poetry, he said, of examining even the smallest thing in meticulous detail, thereby ennobling the subject to some aesthetic-philosophical-spiritual height. It’s one of the distinguishing features of his own work.

“The short lyric poem very often addresses one thing and looks at it very carefully. That’s very common. I guess I’m well known for writing poems about very ordinary things. There’s a poem in my latest book about a spiral notebook. Every drug store in the state has a pile of them. Nothing more ordinary than that. I’ve written poems about leaky faucets and about the sound a furnace makes when it comes on and the reflections in a door knob. They’re all celebrations in some sense. Praise” for the beauty and even the divine bound up in the ordinary.

His Henry David Thoreau-like existence, complete with his own Walden’s Pond, feeds his muse and gives him a never-ending gallery to ponder and to convey.

“I like it out here. I like being removed from town. I like it because it’s quiet. For instance, I have a poem in my book Weather Central about sitting here and watching a Great Blue Heron out here on the pond. And there are many poems like that. There’s another one in that same book called A Hatch of Flies about being down in the barn one morning very early in the spring and seeing a whole bunch of flies that had recently hatched behind a window.”

The rhythms of country living complement his unhurried approach to life and work. He waits for inspiration to come in its own good time. When an idea surfaces, he extracts all he can from it by finding purity in the music and meaning of language. Words become notes, chords and lyrics in a kind of song raised on high.

“I never really have an idea for a poem,” he said. “I’ll stumble upon something and it kind of triggers a little something and then I just sort of follow it and see where it goes. I always carry a little notebook. If I see something during the course of the day I want to write about, I make a note of it.”

Another element identifying Kooser’s work is the precision of his language and his exhaustion of every possible metaphor in describing something. The rigor of poetry and of distilling subjects and words down to their truest essence appeals to him.

“I think there’s a kind of polish on my metaphors. I’m extremely careful and precise in the way I use comparisons. I wrote about that in my Poetry Repair Manual. How you really work with a metaphor. You just don’t throw it in a poem and let it go. You develop it and take everything out of it you can. With a poem, once it’s finished or it’s as finished as best as I can finish it, there isn’t anything that can be moved around. You can’t substitute a word for its pseudonym or its synonym. You can’t change a punctuation mark or anything like that without diminishing the effect,” he said. “Whereas, with prose, you can move a word around or change the sentence structure and it really doesn’t have that much of an effect on the overall piece. I like the fact poetry has to be that orderly and that close to perfect. I tend to be a kind of orderly type guy.”

Getting his work as close to perfection as possible takes much time and effort.

“I spend a lot of time revising my poems and trying to get them just right. A short poem will go through as many as 30 or 40 revisions before it’s done. Easily. I’m always trying to make the poems look as if they’re incredibly simple when they’re finished. I want them to look as if I just dashed them off. That takes revision itself. I’m always revising away from difficulty toward clarity and simplicity.”

So, how does he know when a poem is done?

“I think what happens is eventually you sort of abandon the poem. There’s nothing more you can do to make it better. You just give up. Rarely do you get one you think is really perfect. But that blush of success doesn’t usually last very long.”

A serious poet since his late teens, Kooser has refined his style and technique over a half-century of experimentation and dogged work.

“We learn art by imitation — painters, musicians, writers, everybody — by imitating others. So, the more widely you read, the more opportunities there are to imitate different forms and different approaches, and I tried everything I suppose,” he said. “You learn from the bad, unsuccessful poems as much as you learn from the good ones. You see where they fail. You see where they succeed. I’ve written the most formal of forms — sonnets and sestinas and ballads and so on, just trying them out, as you’d try on a suit of clothes.”

“I’ve come to my current style, which feels very natural to me,” through this process of trial and error and searching for a singular voice and meter and tone. “Somebody glancing at it would say, ‘Well, this is free verse.’ But it really is not free verse at all. I take a tremendous amount of care thinking about the number of syllables and accents in the lines. I might not have three accents in every lines, but the only reason I wouldn’t add another accent to a line of two is that it would seem excessive or redundant in a way.

“So, I never let the form dominate the poem. It’s all sort of one thing. And I think poems proceed from someplace and then they find their own form as they’re written. You let them develop. You let them fill their own form.”

Being open to the permutations and rhythms of any given poem is essential and Kooser said his routine of predawn writing, which he got in the habit of while working a regular office job, feeds his creativity and receptivity. “It’s a very good time for me to write. It’s quiet. You mind is refreshed. I’m a poet very much devoted to metaphor and rather complex associations,” he said, “and they tend to rise up at that time of day. I think what happens is as you come out of sleep your mind is trying make connections and sometimes some really marvelous metaphors will arise. By the end of the day, your head is all full of newspaper junk and stuff.”

All that sounds highly romantic, but the reality and discipline of writing every day is far from idyllic. Yet that’s what it takes to become an artist, which reminds Kooser of a story that, not surprisingly, he tells through metaphor.

“A friend of mine had an uncle who was the tri-state horse shoe pitching champion three years running and I asked — ‘How’d he get so good at it? — and my friend said, ‘Son, you’ve got to pitch a hundred shoes a day.’ And that’s really what you have to do to get good at anything. And I tell my students that, too: ‘You’ve got to be in there pitching those hundred shoes every day.’ Often times, in the process of writing, the really good things happen. That’s why you have to write every day. You have to be there, as the hunters say, ‘when the geese come flying in.’”

As most writers do, Kooser came to his art as an eager reader. He grew up in a Cold War-era home where books were abundant. He became a fixture at the local public library in Ames. His mother, who had some college and was a voracious reader, encouraged young Ted. But what really drove him, more than the Robert Louis Stevenson books he devoured, was his sense of being an outsider. He was a puny kid who didn’t mesh with the cliques at school. But in writing he found something of his own. A key book in his early formation as an aspiring writer was Robert McCloskey’s novel Lentil.

“It’s about a boy in a small town who doesn’t fit it very well. He’s not an athlete. He can’t sing. Then he teaches himself to play the harmonica. When a very important person from the town returns home, the band is all assembled at the depot, the banners are all hung out and a parade is planned down main street. But the guest has an enemy who gets up on the depot roof with a lemon, and when the band gets ready to play, he slurps this lemon and the band can’t blow their horns. But Lentil can play his harmonica and by saving the day he gets to ride with the special guest in the parade. The last line of the poem is, ‘So you never know what will happen when you learn to play the harmonica. And that really is a seminal story for me. I identified with that kid. And this poetry business is really like the harmonica. This was my thing to do. And so, for me, the lesson was, You never know what will happen when you learn to write poetry.”

Besides writing, Kooser was “into hot rods.” He built one car himself and built another one with a friend. It was inevitable he would combine both passions.

“I was writing these Robert Service-type ballads about auto races. I wrote a long one about a race and some of my friends sent it to a slick teen magazine called Dig. It was nothing I would have ever done myself. I never was one to really put myself forward in any way. But they sent it in, and it was published, much to my surprise.”

Between the buzz of his first published story, the strokes his teachers gave him and the emerging Beat Poetry scene he embraced, Kooser was sold on the idea of being a poet despite and, indeed, because of the fact it was so far afield from his proletarian roots. Making his mark and defying convention appealed to the non-conformist in Kooser. It was his way of standing apart and being cool.

“I wanted to be a poet right from the time I was 17 or 18. That was really my driving force. It was the idea of being different and interesting. I wanted to be on the outside looking in. It had a lot to do with girls, frankly. I came from an extremely plain, ordinary, middle class background and I wanted to set myself apart from that. Who knows how that works psychologically? My mother was very devoted to me and had very conventional ideas, and it may have been my attempt to separate myself from her. And to this day, when I become sort of reabsorbed into the establishment, as if I had ascended in class to some other level, I feel slightly uncomfortable and rebellious. I think that to be successful as an artist you have to be on the outside of the general order — observing it.”

In his wife, Kathy Rutledge, whom he met in the ‘70s, he’s found a kindred spirit. A child of the ‘60s, she was caught up in the fervor of the times. Now the editor of the Lincoln Journal Star, she shares his love of writing and is his gentle reader.

“She helps me with my writing. She’s a very good reader of my work. She’s a brilliant woman. She knows terms for the English language I don’t understand.”

He finds it ironic a pair of iconoclasts have ended up in such mainstream waters. She as a daily newspaper editor and he as “a celebrated poet” speaking to Kiwanis and Rotary Club meetings and giving college commencement addresses.

Besides his poetry and his insurance job, which he retired from a few years ago, Kooser’s been on the periphery of the academic circle. He’s taught night classes for years at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he earned his master’s.

Growing up in a college town, he gravitated almost as a matter of course to local Iowa State University, where he studied architecture before the math did him in. His literary aspirations led him into an English program that earned him a high school teaching certificate. He taught one year before moving onto UNL for grad studies. He was drawn by the presence of former U.S. Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize-winner Karl Shapiro, under whom he studied. When Kooser spent more time hanging out with Shapiro than working on his thesis, he lost his grad assistantship and was forced to take a real job. He entered the insurance game as a stop-gap and ended up making it a second career. It was all a means to an end, however.

“I worked 35 years in the life insurance business, but it was only to support myself to write. It was an OK job and I performed well enough that they kept promoting me. But writing was the important thing to me and I did it every morning, day in and day out. Writing was always with me. I’ve never not been writing.”

While his 9 to 5 job gave him scant satisfaction beyond making ends meet, it proved useful in providing the general, non-academic audience for his work he sought.

“The people I worked with influenced my poetry,” he said. “We all write toward a perceived community, I think, and I was writing for people in that kind of a setting. I had a secretary in the last years I was there, a young woman who’d read poems in high school but had no higher education, and I often showed her my work. I’d say, ‘Did it make any sense to you?’ and she’d say, ‘No, it didn’t.’ And I’d go home and work on it, until it did because I wanted that kind of audience. I would not refer to anything that would drive anybody to stop in the middle of the poem to go look it up in the encyclopedia. The experience of the poem shouldn’t be interrupted like that. I have a very broad general audience. I get mail from readers every day.”

A less obvious benefit of working as a medical underwriter, which saw Kooser reading medical reports filled with people’s illnesses, was gleaning “a keen sense of mortality.” “Poetry, to really work,” he said, “has to have the shadow of mortality carried with it, because that darkness is what makes the affirmation of life flower.”

These days, Kooser is working hard to help poetry bloom in America, where he feels “it’s really thriving” between the literary-academic, cowboy, hip hop and spoken word poets. “It’s so important to do a good job as Poet Laureate, as far as extending the reach of poetry, that I’ve largely set my own writing aside for now.” His post, which he sees as “a public relations job for the sponsoring Library of Congress and for poetry,” has him promoting the art form as a speaker, judge and columnist. His syndicated Everyday Poetry column is perhaps his most visible outreach program. He’s considering doing an anthology of poems about American folklore. He’s also collaborating with educators to distill their ideas for teaching poetry into a public forum, such as a website. “The teachers are really on the front line here. They’re the people who make or break poetry,” he said.

Then, as if reassuring his visitors he’s no elitist, he excuses himself with, “I’ve got to run up to the house — I’ve got a pheasant in the oven.” Yes, even the Poet Laureate must eat.

Related Articles

- Author Wins National Poetry Award (nebraskapress.typepad.com)

- Poetry Pairing | August 19, 2010 (learning.blogs.nytimes.com)

- Poet Laureate Announced: William S. Merwin Named 17th U.S. Poet Laureate (huffingtonpost.com)

- “Librarian of Congress James H. Billington today announced the appointment of WS Merwin as the Library’s 17th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry for 2010-2011.” and related posts (resourceshelf.com)

- Off the Shelf: Valentines by Ted Kooser (nebraskapress.typepad.com)

- Poetry Pairing | March 31, 2011 (learning.blogs.nytimes.com)

- After Years, Ted Kooser (objetsdevertu.wordpress.com)

- Billy Collins “Introduction to Poetry” (thenightlypoem.com)

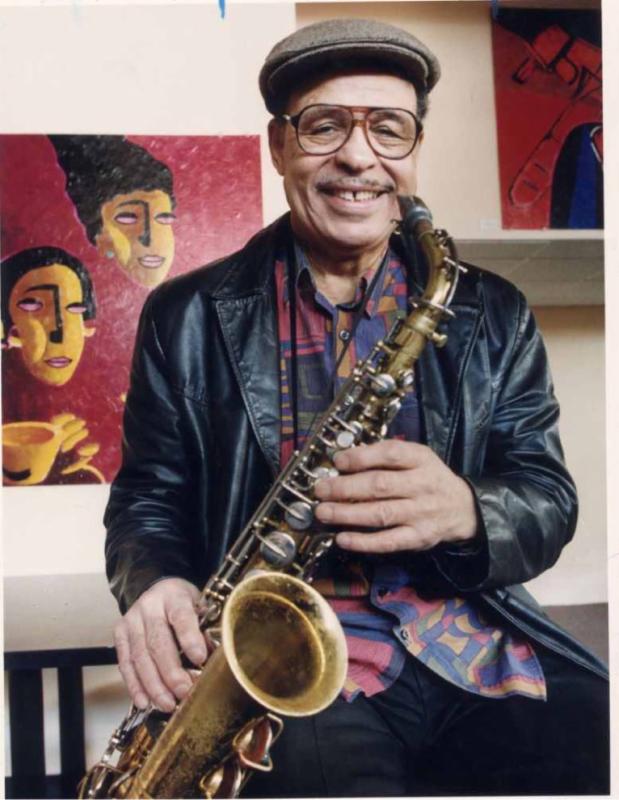

RIP Preston Love Sr., 1921-2004, He Played at Everything

This is one of the last stories I wrote about Omaha jazz and blues legend Preston Love. It’s a tribute piece written in the days following his 2004 death. Trying to sum up someone as complex and multi-talented as Preston was no easy task. But I think after reading this you will have a fair appreciation for him and what was important to him. The piece originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). I actually ended up writing about him two more times, once on the occasion of the opening of the Loves Jazz & Arts Center, which is named in his honor and located in the hub of North Omaha‘s old jazz scene, and then again when profiling his daughter Laura Love, a singer–musician he fathered out of wedlock. You can find my other Preston Love stories along with my Laura Love story on this blog site.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader,com)

Lead alto sax player with Basie in the 1940s. Territory band leader in the ‘50s. Arranger, sideman, band leader for Motown headliners in the ‘60s. Studio session player. Recording artist. Music columnist. Radio host. Teacher, lecturer, author.

Until his passing from cancer at age 82, the voluble, playful, irrepressible, ingenious Preston Love wore all these hats and more during a long, versatile career. Around here, he may be best remembered for the easy way he performed at countless venues or the nostalgic, by-turns cantankerous tone of his Love Notes column or the adoring tributes and scalding rebukes he issued as host of his own jazz radio programs. Others might recall the crusading zeal he brought to his roles as college instructor, lecturer and artist-in-residence in spreading the gospel of jazz.

His curt dismissal of some local jazz musicians made him an egoist in some corners. In Europe, he was accorded the respect and adulation he never got at home. Yet, despite feeling unappeciated here, he often championed Omaha. It took the publication of his 1997 autobiography to make his resident jazz legend status resonate beyond mere courtesy to genuine recognition of his talents and credits.

For his well-received book, A Thousand Honey Creeks Later, My Life in Music from Basie to Motown (Wesleyan Press), Love drew on an uncanny memory to look back on a life and career spanning an enormous swath of American history and culture. It was a project he labored on for some 25 years and even though he still had a lot of living left in him, it served then, as it does now, as an apt summing-up and capstone for an uncommon man and his unusual path. It’s a bold, funny, smart, brutally frank work filled with the rich anecdotes of a born storyteller.

“You know how most people who write their life story have ghost writers? Well, he wrote his book. Every word,” says his son, Richie Love, with pride and awe.

The ability, with no formal training, to master writing, music and other pursuits was what Billy Melton calls his late friend’s “God-given talents. Preston just picked up everything. He had a photographic memory. He was remarkable.” Richie Love says his father’s huge curiosity and appetite for life was part of “a drive to excel” that came from being the youngest of nine in a poor, single-parent house so run down it was jokingly called the” Love Mansion.” Young Preston taught himself to play the sax, abandoning a promising career in the boxing ring for the bandstand, where the prodigy’s gift for sight reading became his forte. “Any kind of music you put in front of him, he played it,” says former Love pianist Roy Givens.

Whether indulging in food and drink, friends and family, leisure or work, Richie Love says his father lived large. “Everything he did was larger than life. He did everything with a passion. Music. Fishing. Cooking. He was just so interesting. He was an all-around person. People loved him. People flocked to him.”

“He was just a big man all the way around,” says Juanita Morrow, a lifelong friend and fishing companion who experienced his generosity when she and her late husband, Edward, fell ill and Love made frequent visits to their home, bringing them groceries. “I’ll remember him as a very dear friend. He never let my husband and I down. No matter where he went on tour…he always sent letters and pictures.”

Frank McCants, another old chum from back in the day, says even after making it big with Basie that Love “never got the big head. He stayed regular.” Melton says Love would return from the road looking for a good time. “Preston made the big bucks and when he came to town he’d look us up…and that’s when the partying would begin. We let our hair down.” On those rare occasions when the blues overtook Love, Melton says, “music was the antidote. He really loved it.”

Although he hated being apart from his wife Betty, who survives him, Love savored “the itinerant life.” Givens recalls how he made life on tour a little more enjoyable: “He was a very serious musician, but he was a joker. He kept you laughing a lot because of the things he would say and do.” Traveling by bus, the spontaneous Love often heeded the sportsman’s call en route to a gig. “He loved to hunt and he loved to fish,” Givens says, “and on the bus we had he carried his shot gun and his fishing rod. If we went across any water, he’d stop the bus and say, ‘I’m just going to see what I can catch in 15 or 20 minutes.’ He’d throw in a line. When passing by a field, if he’d see a pheasant or a rabbit, he’d stop and shoot at it out the windows. If he hit anything, he’d skin it. If he caught anything, he’d put it on ice in a cooler. A lot of times we were almost late getting to the job because he would be catching fish and he didn’t want to leave. The guys would just laugh.”

A consummate showman, Love burned with stage presence between his insouciant smile and his patter between sets that combined jive, scat and stand up. Richetta Wilson, who sang with various Love bands, recalls his ebullience. “He would talk more than he would play sometimes. He was so funny and talented. The best person you could ever want to work with.” Billy Melton recalls Love teasing audience members from the bandstand. “Almost everybody that came in the door he’d know by name and he’d call them out. He was always joking, but he could take it, too. He didn’t care what you said about him.”

Then there was his serious side. Love coaxed a smooth, sweet, plaintive tone from the sax developed over a lifetime of listening and jamming in joints like McGill’s Blue Room on north 24th Street. As a student of music, he voiced learned, militant diatribes against “the corruption of our music.” As he saw the once serious Omaha jazz scene abandon its indigenous roots, he used his newspaper columns, radio shows and college classrooms as forums for haranguing local purveyors and performers of what he considered pale imitations of the real thing.

Calling much of the white bread jazz presented here “spurious” and “synthetic,” he decried the music’s most authentic interpreters being passed over in favor of less talented, often times white, players. “My people gave this great art form for posterity and I’m not going to watch my people and our music sold down the road,” he said once. “I will fight for my people’s music and its presentation.”

He delivered his eloquent, evangelical musings in free-flowing rants that were equal parts improvisational riff, poetry slam and pulpit preaching, his mellifluous voice rising and falling, quickening and slowing in rhythmic concert with his emotions.

Love’s guardianship for the music may live on if the planned Love Jazz-Cultural Arts Center dedicated to him on 24th Street ever opens, which organizers say could happen by the end of 2004. The center’s driving force, Omaha City Councilman Frank Brown, hopes the facility can showcase the Love legacy, including his many well-reviewed recordings. “I want visitors to know here is a person who was great and touched greatness and was part of that rich jazz history,” Brown says. “People like that just don’t come along every day. And I want kids to walk away with the feeling they too can achieve like he did.” Richie Love says he wants people to know his dad was “a great man.”

Center board members plan displaying items from the mass of memorabilia the late artist collected in his collaborations with what one reviewer of a reissued Love album called a “Who’s Who of American Musicians.” The star-studded roster of artists he worked with ranged from Count Basie, Lucky Millinder and Earl Hines to Wynonie Harris, Billie Holiday and Jimmy Rushing to Aretha Franklin, The Four Tops, The Temptations, The Supremes, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Ray Charles, Marvin Gaye, Issac Hayes and Stevie Wonder.

Richie Love is sorting through the materials, including hundreds of photos, in an effort to decide what the family will donate to the center. Many photos picture Love with the Motown artists he worked with during his decade (1962 to 1972) in California. He moved his family there at the urging of friend Johnny Otis, the blues great with whom he often collaborated. Love worked as an L.A. session player and sideman and, later, as the leader of Motown’s west coast backup band, an ensemble that backed many of the label’s artists performing there.

For Richie, and siblings Norman and Portia, the L.A. years were golden. Richie recalls the high times that ensued whenever his father parked the Motown tour bus outside their rented house on West 29th Place. “The kids from the neighborhood would see that bus and we’d all get on it. I’d sit in the driver’s seat and act like I was driving and they’d be in the back singing like they were Motown. It was just the greatest.” Other times, stars arrived in style at the Love home. “We’d look out the window and see a limo coming and say, ‘Oh-oh, who’s it going to be this time?’ I think Dad liked to surprise us. It was always somebody different.” Some visitors, like Gladys Knight or Jimmy Rushing, became live-in guests, passing the time swapping stories and playing Tonk, a popular card game among blacks. “My brother, sister and I would sit in the front room and watch and listen while they were having a ball, laughing and talking all night. We’d get up in the morning, and they’d still be there.” Then there were the times when the boys accompanied their father to television tapings or live concerts and got to hang backstage with the show’s stars, including Stevie Wonder. “Oh, it was the coolest,” Richie says.

|

Having a dad who’s a kid at heart meant impulsive trips to the beach, swimming pools, fishing holes, music gigs. Sitting up with him all hours of the night as he made “elaborate dinners” – from gourmet to barbecue – and “told these great stories,” Richie says. “He was a great father…he turned us on to so many things in life.”

By all accounts, Love was a good teacher as well. Whether holding court at the Omaha Star, where he was advertising director, or from the bandstand, he shared his expertise. “He helped musicians reach their potential,” says Roy Givens. “After listening to you play, he could tell you what your weaknesses were…He would pull you aside and tell you to work on them. I know he made me a better musician.”

Melton says Love often spoke of a desire “to pass his knowledge on.” To see the results of that teaching, Givens says, one has only to look at Love’s children. “They are all exceptional musicians, and that right there’s an accomplishment.” Richie is an instrumentalist, composer and studio whiz. Norman, who resides in Denver, is widely regarded as an improvisational giant. Portia is a jazz vocalist. All performed with their father on live and recorded gigs.

If nothing else, Preston Love endured. He survived fads and changing musical tastes. He adapted from the big band swing era to the pop, soul, rhythm and blues refrains of Motown. He rose above the neglect and disdain he felt in his own hometown and kept right on playing and speaking his mind. Always, he kept his youthful enthusiasm. The eternal hipster. “I refuse to be an ancient fossil or an anachronism,” Love told an interviewer in 1997. “I am eternally vital. I am energetic, indefatigable. It’s just my credo and the way I am as a person.”

Even into his early 80s, Love could still swing. Omaha percussionist Gary Foster, who played alongside him and produced CDs featuring him, marveled at his skill and vitality. “He had a very pure, soulful sound that just isn’t heard anymore. It’s that Midwestern, Kansas City thing. He was part of that past when it was real — when the music was first coming and new. He had that still.” He says Love was not about “coasting on what he’d done in the past,” adding: “To him, that just wasn’t good enough. He still wanted to produce. He was still hungry. In the studio, he was like, ‘What are we doing today? Where are going to take the music today?’”

Love’s musical chops were such that, at only 22, he earned an audition with Basie during an appearance of the Count’s fabled band at Omaha’s Dreamland Ballroom. In the same room he grew up worshiping at the feet of his musical idol, Basie sax great Earle Warren, Love won a seat in the band as a replacement for none other than the departing Warren. “Preston Love was part of this lineage of great lead alto saxophone players. With Basie, he took over for one of the great lead alto saxophone players…and he performed that role with distinction,” Foster says.

Love once said, “Everything in my life would be an anticlimax because I realized my dream.” That dream was making it to the top with Basie. Luckily for us, he didn’t stop there. Now, he leaves behind a legacy rich in music and in Love.

Related Articles

- Leon Breeden, Jazz Educator, Dies at 88 (nytimes.com)

- International Jazz Day (beliefnet.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Big Bad Buddy Miles (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Once More With Feeling, Loves Jazz & Arts Center Back from Hiatus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Rich Music History Long Untold is Revealed and Celebrated at the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

“Omaha Blues” and “Preston Love’s Omaha Bar-B-Q”: Two scorching instrumental blues journeys by Omaha music Llgend Preston Love

This next story is actually adapted from a press release that the late Omaha jazzman and blues artist, Preston Love Sr., commissioned me to write to help promote a new CD he was releasing. I include it here as another element of putting the arc of his life and career in proper perspective.

“Omaha Blues” and “Preston Love’s Omaha Bar-B-Q’” Two scorching instrumental blues journeys by Omaha music legend Preston Love

©by Leo Adam Biga

Adapted from a press release I wrote for Preston promoting a new CD

At age 80, legendary Omaha jazz and blues musician Preston Love is enjoying the kind of renaissance few artists survive to see. It began with the 1997 publication of his autobiography, A Thousand Honey Creeks Later (Wesleyan University Press), which earned rave reviews in such prestigious pages as the New York Times Book Review. Next, came a steady stream of re-released albums on CD featuring a much younger Love playing in such distinguished company as the Count Basie and Lucky Millinder bands, just two of the classic groups he played with during this indigenous American music’s Heyday.

Now, there is the unlikely release of two albums, produced 30 years apart, each with the name Omaha in them – Omaha Blues and Preston Love’s Omaha Bar-B-Q – and each showcasing Love at his silky smooth lead alto saxophone playing best. Love has always been faithful to his hometown of Omaha where, as a kid, he first got hooked on jazz and blues by hanging on every note performed by his idols at the near northside clubs he later played too. He still makes his home in Omaha, where he lives with his wife Betty.

“What a unique thing to have two albums out with the name Omaha in them and to have them selling like hotcakes all over the country,” Love said. “What a thrill.”

Beyond the rare confluence of Omaha in their titles, the two releases cast an equally rare spotlight on an artist at two different periods in his career as a jazz-blues interpreter. A brand new release, the Omaha Blues CD presents the ever vibrant Love performing the music of his life, including a mix of standards by the likes of Duke Ellington and Count Basie and a selection of original Love tunes, including the soulful title track.

Produced by Gary Foster at Omaha’s Ware House Productions studio and distributed by North Country Distributors, Omaha Blues has received high praise from what is commonly referred to as The Bible of jazz and blues magazines for the way Love and his band perform everything from slow ballads to hot swinging numbers. Special praise is reserved for Love’s music-making.

Gregg Ottinger, a reviewer with Jazz Ambassador Magazine in Kansas City, writes that the ensemble heard on the record “is particularly good and provides an excellent surrounding for Mr. Love’s strong sound. But the highlight of the CD is Mr. Love’s playing. This is a man who is full of music – eight decades of it – and it’s still strong and fresh. It’s a joy to hear it released on this recording.” Jack Sohmer in Jazz Times describes Love as “still a masterly saxophonist,” adding, “The proof is here that Love has not lost a beat…” And Robert Spencer in Cadence writes, “Preston Love has a slippery, slithery tone that slides through the blues real easy and rings all the changes on a dime with a fine exuberance. Preston Love plays this music with superlative commitment and yes, love. Great fun.”

Producer Gary Foster, the drummer on this recording and a regular percussionist with Love’s working band, said he was drawn to the project because it provided an opportunity to bring the man he considers his mentor to the forefront, a position unfamiliar to this venerable artist who for decades toiled in relative obscurity as a highly respected if not starring sideman, session musician, contractor and band leader.

Also a flutist, Love was a fixture in the reed section of many bands and made a name for himself with his ability to sight read. In addition to playing with Basie and Millinder, he headed-up his own territory bands and led Motown’s west coast band.

“I’m really happy I was able to present Preston Love just doing what he does best and doing it as well as he can. I think in the past Preston deferred to what producers wanted and a lot of times he ended up in the background,” said Foster, who refers to Love’s many studio and live collaborations with legendary artists — ranging from Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin to longtime friend and rhythm and blues great Johnny Otis. During these gigs, Love almost always played a supporting role. But, as Foster and others see it, Love is more than deserving of his own limelight because he is a consummate artist in his own right and the genuine article to boot.

“Preston Love is part of this lineage of great lead alto saxophone players. With Basie, he took over for one of the great lead alto saxophone players — Earl Warren — and he performed that role with distinction. He did a great job,” Foster said.

The way Foster sees it, Love is still making sweet sounds some half-a-century later. “He’s got a very pure, soulful sound that just isn’t heard anymore. It’s that Midwestern, Kansas City thing. He’s part of that past when it was real — when the music was first coming and new. He’s got that still.” Despite the fact Foster has played alongside Love for years he is still amazed that a man of his age remains as sharp and vital and curious as he is. “I’m half his age and I watch this guy night after night constantly trying to improve himself. He’s 80 years old and he’s still worried about being good enough. He’s never satisfied. It’s an inspiration. That’s what I aspire to be as an artist — just constantly trying to be better.”

Foster said Love is not about “coasting on what he’s done in the past,” adding: “To him, that’s just not good enough. He still wants to produce. He’s still hungry. In the studio, he’s like, ‘What are we doing today? Where are going to take the music today?’”

The idea of resting on his laurels is anathema to Love, who dismisses the notion he is some “moldy fig” or stick in the mud. Indeed, Love feels his playing has never been better. “I reached my peak on my instruments later in life,” he said. “I wasn’t interested that much in a career as a soloist early on, but as I became more interested in that I was able to accomplish more at a time in life when most guys deteriorate. I refuse to be an ancient fossil or an anachronism. I am eternally vital. I am energetic, indefatigable. It’s just my credo and the way I am. I play my instruments as modern as anybody alive and better than I’ve ever played them. It’s helped that my health has been good too.”

For Love, Omaha Blues was a blast to make because he was working with his longtime band members Orville Johnson (piano), Nate Mickels (bass) and Foster (drums), along with his daughter Portia Love, an assured vocalist and frequent collaborator. Also heard on the disc are guitarist Jon Hudenstein, pianist Bill Erickson, bassist John Kotchain and vocalist Ansar Muhammad. Of his fellow musicians, Love said, “The guys are just miraculous on this. We didn’t get technical or anything. We just banged it out and I think we did a good job.” Love also lends his smoky voice to a few tunes.

Originally produced on Kent Records and now being re-released by Ace Records of Great Britain, Preston Love’s Omaha Bar-B-Q represents Love at a time and place in his career when he was working with some of the music industry’s strongest talents. “These were top players and all dear friends of mine. I hired them a lot for the Motown band,” Love said. “We had James Brown’s drummer and Ike and Tina Turner’s sax player. We had my dear friend Johnny Otis, who produced the album. Johnny also brought in his son, Shuggie, then a 15 year-old prodigy on the guitar.”

The recording features several different artists, but most notably Shuggie, now enjoying a revival of his own. “He played the greatest blues solos on guitar on that album that will ever be done,” Love said. “He’s a genius.” In keeping with the album’s Omaha and eating themes, the tracks feature a number of Love-penned tunes named after favorite soul food staples, including Chitlin Blues. Released in 1970, the album fared well in Europe, where, Love said, “it made me a pretty big name.” The musician has performed in Europe several times and he is preparing to play France later this year.

Not only a performing and recording artist, Love is also a noted jazz-blues columnist and historian. For years, he hosted a popular jazz program on local public radio, a forum he used as a combination stage, classroom and pulpit in presenting classic jazz in its proper aesthetic-cultural-historical context. He is clearly not done making his passionate, sometimes prickly voice heard either. From his brand new CD to classic reissues of old LPs to area gigs his band plays, his music-making continues enthralling and enchanting old and new listeners alike. With his first book, A Thousand Honey Creeks Later, now going into its second printing, Love is already planning to write another book on his eventful life inside and outside music.

NOTES: After a highly successful run at L & N Seafood in One Pacific Place, Preston Love and his band now jam Friday and Saturday nights at Tamam, 1009 Farnam-on-the-Mall, an Old Market restaurant specializing in Middle Eastern cuisine;

Love was recently a featured performer at the August 3 Blues, Jazz and Gospel Festival on the Metropolitan Community College Fort Omaha campus; Omaha Blues can be found at area record and music stores, including Homer’s. Preston Love’s Omaha Bar-B-Q will soon be available.

Related Articles

- Harlem Jazz Museum Acquires Trove By Greats (harlemworldblog.wordpress.com)

- National Jazz Museum Acquires Savory Collection (nytimes.com)

- He Keeps Discovering Who He Is (online.wsj.com)

- Gene Conners obituary (guardian.co.uk)

- Omaha Arts-Culture Scene All Grown Up and Looking Fabulous (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Tyler Owen – Man of MAHA (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Once More With Feeling, Loves Jazz & Arts Center Back from Hiatus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Big Bad Buddy Miles (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Rich Music History Long Untold is Revealed and Celebrated at the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Preston Love: His voice will not be stilled

This is one of those foundational stories I did on Omaha jazz and blues legend Preston Love. Together with my other stories on him I give you a good sense for who this passionate man was and what he was about. The piece originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). I should mention that Love’s autobiography, which is referenced in the story, was well-reviewed by the New York Times and other major national publications. Preston always wanted to leave a legacy behind, and his book, “A Thousand Honey Creeks Later,” is a fine one. The very cool Loves Jazz & Arts Center in the heart of North Omaha’s historic jazz district is named in honor of him. More stories by me about Preston Love can be found on this blog site. I also feature a profile I did on his daughter, singer-songwriter-guitarist Laura Love.

Preston Love: His voice will not be stilled

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader

One name in Omaha is synonymous with traditional jazz and blues — Preston Love Sr., the native son musician most famous for playing lead alto saxophone with the legendary Count Basie in the 1940s.

The ebullient Love, still a mean sax player at 75, fiercely champions jazz and blues as rich, expressive, singularly African-American art forms and cultural inheritances. This direct inheritor and accomplished interpreter of the music feels bound to preserve it, to protect its faithful presentation and to rail against its misrepresentation.

He has long been an outspoken critic of others appropriating the music from its black roots and reinventing it as something it’s not. Over the years he’s voiced his opinion on this and many other topics as a performer, columnist, radio host, lecturer and oft-quoted music authority. Since 1972 his Omaha World-Herald “Love Notes” column has offered candid insights into the art and business sides of music.

From 1971 until early 1996 he hosted radio programs devoted to jazz. The most recent aired on KIOS-FM, whose general manager, Will Perry, describes Love’s on-air persona: “He was fearless. He was not afraid to give his opinion, especially about what he felt was the inequality black musicians have endured in Omaha, and how black music has been taken over by white promoters and artists. Some listeners got really angry.”

With the scheduled fall publication of his autobiography “A Thousand Honey Creeks Later,” by Wesleyan University Press in Middletown, Conn., he will finally have a forum large enough to contain his fervor.

“It’s written in protest,” Love said during a recent interview at the Omaha Star, where he’s advertising manager. “I’m an angry man. I started my autobiography to a large degree in dissatisfaction with what has transpired in America in the music business and, of course, with the racial thing that’s still very prevalent. Blacks have almost been eliminated from their own art because the people presenting it know nothing about it. We’ve seen our jazz become nonexistent. Suddenly, the image no longer is black. Nearly all the people playing rhythm and blues, blues and jazz in Omaha are white. That’s unreal. False. Fraudulent.

“They’re passing it off as something it isn’t. It’s spurious jazz. Synthetic. Third-rate. Others are going to play our music, and in many cases play it very well. We don’t own any exclusivity on it. But it’s still black music, and all the great styles, all the great developments, have been black, whether they want to admit it or not. So why shouldn’t we protect our art?”

When Love gets on a roll like this, his intense speaking style belongs both to the bandstand and the pulpit. His dulcet voice carries the rhythmic inflection and intonation of an improvisational riff and the bravura of an evangelical sermon, rising in a brimstone tirade one moment and falling to a confessional whisper the next. Suzanna Tamminen, acting director of Wesleyan University Press, says, “One of the wonderful things about Preston’s book is that it’s really like listening to him talk. A lot of other publishers had asked him to cut parts out, but he felt he had things to say and didn’t want to have to change a lot of that. So we’ve tried to have his voice come through, and I think it does.”

Love pours out his discontent over what’s happened to the music in the second half of the book. Love, who’s taught courses at the University of Nebraska at Omaha on the history of jazz and the social implications of black music, says he “most certainly” sees himself as a teacher and his book as an educational document.

In his introduction to the book, George Lipsitz, an ethnic historian at the University of California-San Diego and a Wesleyan contributing editor, compares Love to the elders of the Yoruba people in West Africa” “According to tradition, elders among the Yoruba…teach younger generations how to make music, to dance, and create visual art, because they believe that artistic activity teaches us how to recognize ‘significant’ communications. Preston Love…is a man who has used the tools open to him to make great dreams come true, to experience things that others might have considered beyond his grasp.

“He is a writer who comes to us in the style of the Yoruba elders, as someone who has learned to discern the significance in things that have happened to him, and who is willing to pass along his gift, and his vision to the rest of us. His dramatic, humorous and compelling story is significant because it uses the lessons of the past to prepare is for the struggle of the future. It is up to us to pay attention and learn from his wisdom.”

Some may disagree with Love’s views, but as KIOS Perry points out, “All they can do is argue from books. None of them were there. None of them have gone through what’s he gone through. They have nothing to compare it with.” Perry says Love brings a first-hand “historical perspective” to the subject that cannot be easily dismissed.

Those who share Love’s experience and knowledge, including rhythm and blues great and longtime friend, Johnny Otis, agree with him. “Those of us who came though an earlier era are dismayed,” Otis said by phone from his home in Sebastopol, Calif., “because things have regressed artistically in our field. Preston is constantly trying to make young people understand, so they’ll do a little investigation and get more artistry in their entertainment. He’s dedicated to getting that message out.”

But Love’s book is far more than a polemic. It’s a remarkable life story whose sheer dramatic arc is daunting. It traces his deep kinship with jazz all the way back to his childhood, when his self-described “fanaticism” developed, when he haunted then flourishing North 24th Street’s popular jazz joints to glimpse the music legends who played there.

He grew up the youngest of nine in a ramshackle house in North Omaha. Love’s mother, Mexie, was widowed when he was an infant. Music was always part of his growing up. He listened to his music idols, especially Count Basie and Basie’s lead alto sax man, Earle Warren on the family radio and phonograph. He taught himself to play the sax brought home by his brother “Dude.” He learned, verbatim, Warren’s solos by listening to recordings over and over again. By his med-teens he was touring with pre-war territory bands, playing his first professional gig in 1936 at the Aeroplane Inn in Honey Creek, Iowa (hence the title of his book).

At Omaha’s Dreamland Ballroom he saw his idols in person, imagining himself on the bandstand too — hair coiffured and suit pressed — the very embodiment of black success. “We’d go to see the glamour of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. We aspired to escape the drabness and anonymity of our own town by going into show business,” Love recalls. “I dreamed of someday making it…of going to New York to play the Cotton Club and of playing the Grand Terrace in Chicago.”

He encountered both racism and kindness touring America. The road suited him and his wife Betty, whom he married in 1941.

The couple’s first child, Preston Jr., was born 54 years ago and the family grew to include three more off-spring: Norman and Richie, who are musicians, and Portia, who sings with her father’s band.

Life was good and Love, who eventually formed his own band, enjoyed great success in the ’50s. Then things went sour. Faced with financial setbacks, he moved his family to Los Angeles in 1962, where he worked a series of jobs outside music. His career rebounded when he found work as a studio musician and later as Motown’s west coast band leader in the late ’60s, collaborating with such icons as Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles and Stevie Wonder. He returned to Omaha in 1972, only to find his music largely forgotten and his community in decline. While often feeling unappreciated in his hometown, he basked in the glow of triumphant overseas tours, prestigious jazz festival performances and, more recently, reissues of classic recordings. Today, he’s an elder statesman, historian and watchdog.

To grasp just how much the music means to him, and how much it saddens him to see it lost or mutilated, you have to know that the once booming North 24th Street he so loved is now a wasteland. That the music once heard from every street corner, bar, restaurant, and club has been silenced altogether or replaced by discordant new sounds.

The hurt is especially acute for Love because he remembers well when Omaha was a major jazz center, supporting many big bands and clubs and drawing premier musicians from around the region. It was a launching ground for him and many others.

“This was like the Triple A of baseball for black music,” he says. “The next stop was the big leagues.”

He vividly recalls jazz giants playing the Dreamland and the pride they instilled: “All of the great black geniuses of my time played that ballroom — Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Earl “Father” Hines, Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker. Jazz was all black then, number one, and here were people you read about in magazines and heard on radio coast-to-coast, and admired and worshipped, and now you were standing two feet from them and could talk to them and hear their artistry.”

Love regrets many young blacks are uninformed about this vital part of their heritage. “If I were to be remembered for some contribution,” he says, “it would be to remind people that what’s going on today with the black youth and their rap and all that bull has nothing to do with their history. It’s a renunciation of their true music — blues, rhythm and blues and jazz. You couldn’t get the average young black person today to listen to a record by anyone but one of the new funk or rap players. It’s getting to be where black people in their 20s and 30s feel that way, too.”

He says “the power structure” running the music business in cities like Omaha plays on this malaise, marketing pale reproductions of jazz and blues more palatable to today’s less discriminating audiences:

“Everything’s controlled from out west and downtown in our music. It’s based on personalities, politics and cronyism. Even though it’s often a very poor imitation of the original, it passes well enough not only for whites, but for black too. The power structure has the ability to change the meaning of everything and compromise truth. It’s a disservice to this art and to this city. Every old jazz friend of mine who comes here says the same thing” ‘What happened to your hometown, Preston?'”

Love says his son Norman, a saxophonist living in Denver, largely left Omaha out of frustration — unable to find steady gigs despite overwhelming talent. Love says black musicians have been essentially shut out certain gigs because of their race.

He believes several local musicians and presenters inappropriately use the jazz label. “The implication is that these guys might be fine jazz players. It’s an arrogance on the part of people who really don’t have the gift to perform it and don’t have the credibility to present it. What I’m saying is not an ego trip. It’s irrefutable. It is, at least, a professional opinion.”

It’s on points like these Love elicits the most ire because they are, arguably, matters of taste. For example, Love complains the city’s main jazz presenters don’t book enough black performers and the people booking the events are unqualified. When it’s pointed out to him that half the acts featured in a major jazz series the past two years have been black and the series’ booker is Juilliard-trained, he dismisses these facts because, in his view, the performers “haven’t been much” and the booking agent’s classical credentials carry little weight in jazz circles.

He acknowledges limited opportunities extend even to North Omaha. “We have no place to play in our own neighborhood,” he says. “The club owners here, in most cases, really can’t afford it, but even if they could they don’t know anything about it. So we’ve been thrown to the wolves by our own people.”

Bill Ritchie, an Omaha Symphony bass player and leader of his own mainstream jazz quartet, agrees that many local jazz players don’t measure up and rues the fact there are too few jazz venues. The classically-trained Ritchie, 43, who is white, says the boundaries of jazz, rightly or wrongly, have been blurred: “There’s so much crossover, so much fusion of jazz and rock and pop today, that it’s hard to say where to draw the line. Preston obviously feels he’s one to draw the line. I might go a little further on that line than someone like Preston, because he comes from a different era than I do, and somebody younger than me might even stretch that line a little bit further.”

For Love and like-minded musicians, however, you either have the gift for jazz or you don’t.

Orville Johnson, 67, a keyboardist with Love’s band, says jazz and the blues flow from a deep, intrinsic experience common to most African-Americans. “It’s a cultural thing,” Johnson says. “Jazz is sort of the sum total of life experiences. It’s the same with the blues. There’s a thread that runs clear through it, and it’s a matter of life experience that’s particular to black people in America.

“If a person hasn’t lived that life, it’s unlikely they’ll be able to express themselves musically that way. It’s a sum total of what musicians frequently describe as ‘the dues that we’ve paid.’ It doesn’t have much anything to do with technique. It’s a matter of being able to express in musical terms your experience. A university-educated white student who’s been raised perhaps in a middle-class white neighborhood and never known hunger or the frustration of living in a racial society, usually isn’t able to play and get the same feeling. And that includes a young black person who hasn’t known nearly the hardship that people of my generation or Preston’s generation has known.”

It’s the same message Love delivers in lectures. Like Johnson, Love feels jazz is an expression of the black soul: “To hear the harmony of those black musicians, with that sorrowful, plaintive thing that only blacks have. That pain in their playing. That blue note. That’s what jazz is,” he says. “The Benny Goodmans and those guys never got it. They were tremendous instrumentalists in their own way. But that indefinable, elusive blue note — that’s black, and a lot of blacks don’t get it.”

The two men doubt if many of the younger persons billing themselves as jazz and blues musicians today have more than a superficial knowledge of these art forms. “Take the plantation songs that were the forerunners of the blues,” Johnson says. “Many of the things they said were not literal. When they sung about an ‘evil woman.’ frequently that was a reference to a slave master…not to a woman at all. There’s pretty much a code involved there. When you study it as I’ve done and Preston’s done, that’s what you discover.”

He and Love feel their music is diluted and distorted by university music departments, where jazz is taught in sterile isolation from its rich street and club origins.

Love bristles at the notion he’s a “moldy fig,” the term Boppers coined to describe older musicians mired in the past and resistant to change.

“As far as being a moldy fig, that’s bullshit. I’m as alert and aware of what’s going on in music now as I was 60 years ago,” he says. “I hear quite a few young guys today who I admire. I’m still capable of great idol worship. I am eternally vital. I play my instruments as modern as anybody alive…and better than I’ve ever played them.”

And like the Yoruba elders, he looks to the past to inform and invigorate the present:

“When you muddy the water or disturb the trend or tell the truth even, you make people angry, because they’d rather leave the status quo as it is. A lot of musicians around her will say privately to me the same things, but they’re afraid to say them publicly. But I’m not afraid of the repercussions. I will fight for my people’s music and its preservation.”

Related Articles

- Harlem Jazz Museum Acquires Trove By Greats (harlemworldblog.wordpress.com)

- National Jazz Museum Acquires Savory Collection (nytimes.com)

- Gene Conners obituary (guardian.co.uk)

- Cicily Janus: Moments Captured, A Moment Passed: Jazz Photographer Herman Leonard (1923 – 8/14/2010) (huffingtonpost.com)

- Omaha Native Steve Marantz Looks Back at the City’s ’68 Racial Divide Through the Prism of Hoops in His New Book, ‘The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Arts-Culture Scene All Grown Up and Looking Fabulous (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Canceled FX Boxing Show, ‘Lights Out,’ May Still Springboard Omahan Holt McCallany’s Career (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Preston Love’s Voice Will Not Be Stilled (short version)

The following story about fabled Omaha jazz man Preston Love Sr., who died in 2004, originally appeared in American Visions magazine. The piece was culled together from a couple earlier stories I had written about Love, both of which can be found on this site: “Mr. Saturday Night “and a much longer version of “Preston Love’s Voice Will Not Be Stilled.” There are yet more Love stories on the blog. He was forever fascinating.

|

Preston Love’s Voice Will Not Be Stilled (short version)

©By Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in American Visions

While Kansas City and Chicago were the undisputed centers for the Midwest’s burgeoning jazz scene in the 1920s and ’30s, Omaha, Neb., was a key launching pad for musicians of the time. “It was like the Triple A of baseball for black music,” recalls Omaha native and Count Basie alumnus Preston Love. “The next stop was the big leagues.”

The flutist-saxophonist grew up the youngest of nine children in a ramshackle house, jokingly called “the mansion,” in a predominantly black North Omaha neighborhood. He listened to his idols (especially Earle Warren) on the family radio and phonograph, taught himself to play the sax his brother “Dude” had brought home, and learned Warren’s solos note for note, laying recordings over and over again.

At Omaha’s fabled but now defunct Dreamland Ballroom, he saw his idols in person, imagining himself on the bandstand, too–the very embodiment of black success. “All of the great black geniuses of my time played that ballroom–Count Basic, Earl Fatha Hines, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker,” he recalls. “We’d get to see the glamour of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong‘ Jazz was all-black then, and here were people you read about in magazines and heard on radio coast to coast and admired and worshipped, and now you were standing 2 feet from them and could talk to them and hear their artistry. I dreamed of someday making it …, of going to New York to play the Cotton Club and of playing the Grand Terrace in Chicago.”

With Warren as his inspiration, Love made himself an acccomplished player. “I had the natural gift for sound–a good tone, which is important. Some people never have it. I was self-motivated. No one had to make me practice. And being good at mathematics, I was able to read music with the very least instruction.” His first paying gig came in 1936, at age 15, as a last-minute fill-in on drums with Warren Webb and His Spiders at the Aeroplane Inn in Honey Creek, Iowa. Soon, he was touring with prewar territory bands.

His breakthrough came in 1943, when Warren recommended Love as his replacement in the Basie band. Love auditioned at the Dreamland and won the job. It was his entry into the big time. “I was ready,” he says. “I knew I belonged.” It was the first of two tours of duty with Basie. In storybook fashion, Love played the very sites where his dreams were first inspired: the Dreamland and the famous, glittering big city clubs he’d envisioned.

Love enjoyed the spotlight, playing with Basie and the bands of Lucky Millinder, Lloyd Hunter, Nat Towles and Johnny Otis. “Touring was fun,” he says. “You played the top ballrooms, you dressed beautifully, you stayed in fine hotels. Big crowds. Autographs. It was glamorous.” The road suited him and his wife, Betty, whom he had married in 1941. And it still does. “The itinerant thing is what I love. The checking in the hotels and motels. The newness of each town. The geography of this country. The South, with those black restaurants with that flavorful, wonderful food and those colorful hotels. It’s my culture, my people,” he rhapsodizes.

Life was good, and Love, who formed his own band, enjoyed fat times in the ’50s. Then things went sour. Faced with financial setbacks, he moved his family to Los Angeles in 1962, where he worked a series of jobs outside of music. His career rebounded when he found work as a studio musician and as Motown Record Corporation‘s West Coast backup band leader.

He returned to Omaha in 1972, only to find the once booming North 24th Street he so loved a wasteland and the music once heard from every street corner, bar, restaurant and club silenced altogether or replaced by discordant new sounds.

Today, the 76-year-old who earned rave reviews playing prestigious jazz festivals (Monterey Montreaux, Berlin); toured Europe to acclaim; cut thousands of recordings; worked with everyone from Basie and Billie Holiday to Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles and Stevie Wonder; and taught university courses on the history of jazz and the social implications of black music–and who still earns applause at the trendy Bistro supper club in Omaha with his richly textured tone and sweetly bended notes–has written his autobiography. While A Thousand Honey Creeks Later (Wesleyan University Press, 1997) recounts a lifetime of itinerant musicianship, it also serves as a passionate defense of jazz and the blues as rich, expressive, singularly African-American art forms and cultural inheritances.

“It’s written in protest,” Love explains. “I’m an angry man. I started my autobiography to a large degree in dissatisfaction with what has transpired in America in the music business and, of course, with the racial thing that’s still very prevalent. Blacks have almost been eliminated from their own art because the people presenting it know nothing about it. We’ve seen our jazz become nonexistent. Suddenly, the image is no longer black. Nearly all the people playing rhythm and blues, blues and jazz … are white. That’s unreal. False. Fraudulent.”

When Love gets on a roll like this, his intense speaking style belongs both to the bandstand and to the pulpit. His dulcet voice carries the rhythmic inflection and intonation of an improvisational riff and the bravura of an evangelical sermon, rising in a brimstone tirade one moment and falling to a confessional whisper the next.

While Love concedes the music is free for anyone to assimilate, he demands that reverence be paid to its origins. In his mind, jazz is separate from fusion and other hybrid musical styles that incorporate jazz elements. For Love, either you have the gift for jazz or you don’t. All the studying, technique and best intentions in the world won’t cut it, without the gift. And while he doesn’t assert that only blacks can excel at jazz, he always returns to the fact that it is, at its core, indigenous black music, an expression of soul: “To hear the harmony of those black musicians, with that sorrowful, plaintive thing that only blacks have. That pain in their playing. That blue note. That’s what jazz is. The Benny Goodmans and those guys never got it. They were tremendous instrumentalists in their own way, but that indefinable, elusive blue note–that’s black.”

Love feels that the music is diluted and distorted by university music departments, where jazz is taught in sterile isolation from its rich street and club origins, and he bristles at the notion that he’s a “moldy fig,” the term boppers coined to describe older musicians mired in the past and resistant to change.

“As far as being a moldy fig, that’s bull—-,” he says. “I’m as alert and aware of what’s going on in music now as I was 60 years ago. I hear quite a few young guys today who I admire. I’m still capable of great idol worship. I am eternally vital. I play my instruments as modern as anybody alive … and better than I’ve ever played them.”

Related Articles

- No one captured the passion and spontaneity of jazz like photographer Herman Leonard. (slate.com)

- A Jazz Colossus Steps Out (online.wsj.com)

- Minton’s closes, Great Night in Harlem (harlemworldblog.wordpress.com)

The Smooth Jazz Stylings of Mr. Saturday Night, Preston Love Sr.

An unforgettable person came into my life in the late 1990s in the form of the late Preston Love Sr. He was an old-line jazz and blues player and band leader who was the self-appointed historian and protector of a musical legacy, his own and that of other African American musicians, that he felt did not receive its full due. Love was a live-life-to-its-fullest, larger-than-life figure whose way with words almost matched his musicianship. As I began reporting on aspects of Omaha’s African American community, he became a valuable source for me. He led me to some fascinating individuals and stories, including his good friend Billy Melton, who in turn became my good friend. But there was no one else who could compare to Preston and his irrepressible spirit.

I ended up writing five stories about Preston. The one that follows is probably my favorite of the bunch, at least in terms of it capturing the essence of the man as I came to know him. The piece originally appeared in the New Horizons. Aspects of this piece and another that I wrote for The Reader, which you can also find on this site, ended up informing a profile on Preston I did for a now defunct national magazine, American Visions. Links to that American Visions story can still be found on The Web. I fondly remember how touched I was listening to the rhapsodic praise Preston had for my writing in messages he left on my answering machine after the first few stories were published. After basking in his praise I would call him back to thank him, and he would go off again on a riff of adulation that boosted my ego to no end.

I believe he responded so strongly to my work because I really did get him and his story. Also, I really captured his voice and pesonality. And this man who craved validation and recognition appreciated my giving him his due.

Near the end of his life Preston hired me to write some PR copy for a new CD release, and I approached the job as I would writing an article. I’ve posted that, too.

The last story I wrote about Preston was bittersweet because it was an in memoriam piece written shortly after his death. It was a chance to put this complex man and his singular career in perspective one more time as a kind of tribute to him. A few years after his death I got to interview and write about a daughter of his he had out of wedlock, Laura Love, who is a fine musician herself. Her story can also be found on this site.

The Smooth Jazz Stylings of Mr. Saturday Night, Preston Love Sr.,

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

An early January evening at the Bistro finds diners luxuriating in the richly textured tone and sweetly bended notes of flutist-saxophonist Preston Love, Sr., the eternal Omaha hipster who headlines with his band at the Old Market supper club Friday and Saturday nights.

By eleven, the crowd’s thinned out, but the 75-year-old Love jams on, holding the night owls there with his masterful playing and magnetic personality. His tight four-piece ensemble expertly interprets classic jazz, swing and blues tunes Love helped immortalize as a Golden Era lead alto sax player and band leader.

Love lives for moments like these, when his band really grooves and the crowd really digs it: “There’s no fulfillment…like playing in a great musical environment,” he said. “It’s spiritual. It’s everything. Anything less than that is unacceptable. If you strike that responsive chord in an audience, they’ll get it too – with that beat and that feeling and that rhythm. Those vibes are in turn transmitted to the band, and inspire the band.”

His passion for music is shared by his wife Betty, 73, the couple’s daughter, Portia, who sings with her father’s band Saturdays at the Bistro and sons, Norman and Richie, who are musicians, and Preston Jr.

While the Bistro’s another of the countless gigs Love’s had since 1936 and the repertoire includes standards he’s played time and again, he brings a spontaneity to performing that’s pure magic. For him, music never gets tired, never grows old. More than a livelihood, it’s his means of self-expression. His life. His calling.

Music has sustained him, if not always financially, than creatively during an amazingly varied career that’s seen him: Play as a sideman for top territory bands in the late ‘30s and early ‘40s; star as a lead alto saxophonist with the great Count Basie Orchestra and other name acts of the ‘40s; lead his own highly successful Omaha touring troupe in the ‘50s; and head the celebrated west coast Motown band in the ‘60s and early ‘70s.

He’s earned rave reviews playing prestigious jazz festivals (Monterey, Montreux, Berlin). Toured Europe to great acclaim. Cut thousands of recordings, including classics re-released today as part of anthology series. Worked with a who’s-who list of stars as a studio musician and band leader, from Billie Holiday to Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles to Stevie Wonder. Performed on network television and radio. Played such legendary live music haunts as the Savoy and Apollo Theater.

After 61 years in the business, Love knows how to work a room, any room, with aplomb. Whether rapping with the audience in his slightly barbed, anecdotal way or soaring on one of his fluid sax solos, this vibrant man and consummate musician is totally at home on stage. Music keeps him youthful. Truly, he’s no “moldy fig,” the term boppers coined to describe musicians out-of-step with the times.

“As far as being a ‘moldy fig’…that’ll never happen. And if it does, then I’ll quit. I refuse to be an ancient fossil or an anachronism,” said Love. “I am eternally vital. I am energetic, indefatigable, It’s just my credo and the way I am as a person. I play my instruments as modern as anybody alive and…better than I’ve ever played them.”

Acclaimed rhythm and blues artist and longtime friend, Johnny Otis, concurs, saying of Love: “He has impeccable musicianship. He has a beautiful tone, especially on solo ballads, which is rare today, if it exists at all. He’s one of the leading lead alto sax players of our era.”

Otis, who lives in Sebastopol, Calif., is white. Love is black. The fact they’ve been close friends since 1941 shouldn’t take people aback, they say, but it does. “Racism is woven so deeply into the fabric of our country that people are surprised that a black and a white can be brothers,” Otis said. “That’s life in these United States.”

Love’s let-it-all-hang-out performing persona is matched by the tell-it-like-it-is style he employs as a recognized music authority who demands jazz and the blues be viewed as significant, distinctly African-American art forms. He feels much of the live jazz and blues presented locally is “spurious” and “synthetic” because its most authentic interpreters – blacks – are largely excluded in favor of whites.

“My people gave this great art form for posterity and I’m not going to watch my people and our music sold down the road,” he said. “I will fight for my people’s music and its presentation.”

Otis admires Love’s outspokenness. “He’s dedicated to getting that message out. He’s persistent. He’s sure he’s right, and I know he’s right.”

Love’s candor can ruffle feathers, but he presses on anyway. “No man’s a prophet in his hometown,” Love said. “Sometimes you have to be abrasive and caustic to get your point over.”

Orville Johnson, Love’s keyboardist, values Love’s tenacity in setting the record straight. “He’s a man that I admire quite a bit because of his ethics and honesty.”

Love has championed black music as a columnist with the Omaha World-Herald, host of his own radio programs and guest lecturer, teacher and artist-in-residence at colleges and universities.