Archive

The Myers Legacy of Caring and Community

Myers Funeral Home is an institution in northeast Omaha‘s African-American community, and like with any long-standing family business there is a story behind the facade, in this case a legacy of caring and community. My article originally appeared in the New Horizons.

The Myers Legacy of Caring and Community

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Strictly speaking, a funeral home is in the business of death. But in the larger scheme of things, a mortuary is where people gather to celebrate life. It’s where tributes are paid, memories are recalled, mourning is done. It’s a place for taking stock. One where offering condolences shares equal billing with commemorating high times. In a combination of sacred and secular under one roof, everything from prayers are said to stories told to secrets shared. It encapsulates the end of some things and the continuation of others. It’s where we face both our own mortality and the imperative that life goes on. Perhaps more than anywhere outside a place of worship, the mortuary engages our deepest sense of family and community.

Besides organizing the myriad of details that services encompass, funeral directors act as surrogate family members for grieving loved ones, providing advice on legal, financial and assundry other matters. It means being a good neighbor and citizen. It’s all part of being a trusted and committed member of the community.

“It’s more than just being a funeral director. It’s like I used to tell people, ‘Look, you called me to perform a service, and I’m here to do it. Think of me really as a part of the family. We’re all working together because we have a job to do. My role is to see it goes the way it’s supposed to go,” said Robert L. Myers, former owner and retired director of Myers Funeral Home in Omaha. The dapper 86-year-old with the Cab Calloway looks and savoir-faire ways lives with his wife of 54 years, Bertha, a retired music educator, guidance counselor, choir director and concert pianist, at Immanuel Village in northwest Omaha. After the death of his first wife, with whom he had two daughters, he married Bertha, who raised the girls as her own. They became educators like her.

For Myers, community service extended to social causes. Much of his volunteering focused on improving the plight of he and his fellow African-Americans at a time when de facto segregation treated them as second-class citizens.

He learned the importance of civic-minded conviction from his father, W.L. Myers, the revered founder of Myers Funeral Home — 2416 North 22nd Street — Nebraska’s oldest continuously run African-American owned and operated business. Since the funeral parlor’s 1921 Omaha opening, three generations of Myers have overseen it. W.L. ran things from 1921 until 1947, when his eldest son, Robert, went into partnership with him. Then, in 1950, W.L. retired and Robert took over. He was soon joined by his brother, Kenneth, with whom he formed a partnership before they incorporated. In the early ‘70s, Kenneth handed over the enterprise to his son and Robert’s nephew, Larry Myers, Jr, who still owns and operates it today.

The Myers name has been a fixture on the northeast Omaha landscape for 84 years. From its start until now, it’s presided over everyone from the who’s-who of the local African-American scene to the working class to the indigent.

W.L. saw to it no one was turned away for lack of funds. He assisted people in their time of need with more than a well-turned out funeral, too.

“Families come in helpless. They’ve had a death. It’s a traumatic event. They don’t know what to do. They’re upset. They need some guidance. Dad was more interested in counseling and guiding people than he was in the financial part of it,” Myers said. “He’d tell them which way to go. What extra step they should take. How to handle their business affairs. How to dispose of their property. They’d plead, ‘What am I going to do, Mr. Myers?’ He’d say, ‘Don’t worry about it. You just ask me anything you want.’ I’d say the same thing. That’s where I learned a lot from him. Be fair and be truthful. He was that, so people would call him because they knew he would lead them in the right way. Money was secondary.”

Myers said his father’s goodwill helped build a reputation for fairness that served him and the funeral home well.

“A lot of times, people couldn’t pay him, especially back in the Depression days. He did a lot of charity service. He would talk to Mom about it. ‘They don’t have any money,’ he’d say. ‘Well, go ahead and give ‘em a service,’ she’d tell him. He’d try and reassure her with, ‘It’ll come back some way or another down the line.’ And as a result, he got a lot of repeat business. The next time those people came back, why they were able to pay him. They’d say, ‘I remember you helped me out. I’ll never forget that and I want to employ you again, and this time I’ll take care of it myself.’ Word of mouth about his generosity built his business.”

The Golden Rule became the family credo. “Compassion. That’s what we learned from Dad. He wouldn’t let anybody take advantage of our people. He looked out for our people and saw that they were treated fairly,” he said.

“Back in those days, a lot of our people couldn’t read and write and were afraid of dealing with white collar types, who were usually Caucasian and liked to assert their authority over minorities. Dad used to take folks to the insurance office or the social security office or the pension office, so he could talk eyeball to eyeball with these bureaucrats. That way, our people wouldn’t be intimidated. If the suits got confrontational, he would take over and intercede. He’d say, ‘Wait a minute. Back off.’ He’d speak for the people. ‘Now then, she has what coming to her?’ He’d do the paperwork for them. We’d carry people through the process.”

Myers said his father rarely if ever made a promise he couldn’t keep.

“The word is the bond. That was my dad,” Myers said. “And that’s what I developed, too, in dealing with people. If I say something, you can go to the bank with it.” That reputation for integrity carries a solemn responsibility. “People reveal confidences to you that you would not divulge for love of money. Everything is confidential. You appreciate that type of trust.”

His father no sooner got the funeral home rolling than the Great Depression hit. W.L. plowed profits right back into his business, including relocating to its present site and making expansions. He never skimped on services to clients.

In an era before specialization, Myers said, a funeral director was a jack-of-all-trades. “We did everything from car mechanics to medicine to law to vocal singing to counseling to barber-beautician work to yard work.” Keeping a fleet of cars running meant doing repairs themselves. W.L. graced services with his fine singing voice, an inherited talent Robert shared with mourners. Robert’s mother, Essie, played organ. His wife, Bertha did, too. Describing his father as “a self-made and self-educated man,” Myers said W.L. enjoyed the challenge of doing for himself, no matter how far afield the endeavor was from his formal mortuary training.

“He was very hungry for knowledge. He read incessantly. Anything pertaining to this line of work, to business, to the law…He sent off for correspondence courses. He just wanted to know as much as he could about everything. He knew a lot more than some of these so-called educated people. He could stand toe-to-toe and converse. Doctors and lawyers respected his intellect.”

The patriarch’s “classic American success story” began in New London, Mo., a rural enclave near Hannibal. He sprang from white, black and Native American ancestry. His folks were poor, hard-working, God-fearing farmers. His mother also ran a cafe catering to farmers. Born in 1883, W.L. enjoyed the country life immortalized by Mark Twain. Myers said his father felt compelled from an early age to intern the remains of wildlife he came upon during his Huck Finn-like youth. “He just felt every living thing should have a decent burial. That was his compassion. He just loved to funeralize — to speak words and what-not in a service. I think he had the calling before he realized what he was doing. That just led him into the real thing.”

But W.L.’s journey to full-fledged mortician took many hard turns before coming to fruition. As a young man he found part-time work burying Indians for the State of Oklahoma. Later, he worked in a coal mine in Buxton, Iowa, a largely-black company town that died when the coal ran out. He eventually scraped together enough money to enter the Worsham School of Embalming in St. Louis. When his money was exhausted, he took a garment factory job in Minneapolis, where he was gainfully employed the next eight years. He made foreman. In 1908 he married Essie, mother of Robert, Kenneth and their now deceased older sisters, Florence and Hazel.

The good times ended when W.L.’s black heritage was discovered and he was summarily fired — accused of “passing.” With a family to support, he next made the brave move of picking up and moving to Chicago. There, he worked odd jobs while studying at Barnes School of Anatomy in pursuit of his mortuary dream.

Upon graduating from Barnes in 1910 he was hired as an embalmer at a Muskogee, Ok. funeral home. After a long tenure there he was again betrayed when the owner, whom he taught the embalming art, fired him, saying he no longer needed his services. It was a slap in the face to a loyal employee.

Tired of the abuse, W.L. opened the original Myers Funeral Home in 1918 in Hannibal, where Robert was born. When slow to recover from a bout of typhoid fever he’d contracted down south, doctors ordered W.L. to more northern climes. So, in 1921 he packed his family in a touring car en route to Minneapolis when a fateful stopover in Omaha to visit friends changed the course of their lives.

It just so happened a former Omaha funeral home at 2518 Lake Street was up for grabs in an estate sale. W.L. liked the set-up and the fact Omaha was a thriving town. North 24th Street teemed with commerce then. The packing houses and railroads employed many blacks. Despite little cash, he rashly proposed putting down what little scratch he had between his own meager finances and what friends contributed and to pay the balance out of the proceeds of his planned business. The deal was struck and that’s how W.L. and Myers Funeral Home came to be Omaha institutions. As his son Robert said, “He wasn’t heading here. He was stopped here.” Character and compassion did the rest.

Myers admires his parents’ fortitude. “Dad was a school-of-hard-knocks guy. He was determined to do what he wanted and to make it on his own, and he succeeded in spite of many obstacles. I always appreciated how our mother and father sacrificed to give us advantages they did not have. They put all four of us through college.”

Old W.L.’s instincts about relocating here proved right. Under his aegis, Myers Funeral Home soon established itself as the premiere black mortuary in Omaha.

“He had a little competition when he came in, but it all faded away,” Myers said. “Some of the black funeral homes were fronts for whites. They didn’t have the training, the skills, the know-how, nor the techniques Dad developed over the years. Plus, he was very personable. People took to him. The clientele came to him, and he ran with it.”

“Everybody was pretty much in the same boat. But we had community. We had fellowship. We had a bond through the church and what-not. So, everybody kind of looked out for everybody else,” Myers said.

As youths, Robert and Kenneth had little to do with the family business, but since the Myers lived above the mortuary, they were surrounded by its activities and the stream of people who filed through to select caskets, seek counsel, view departed. Their mother answered the phone and ushered in visitors. The boys were curious what went on in the embalming room but were forbidden inside. They knew their father expected them to follow him in the field.

“It was kind of understood. When I was in school, I looked into other areas like pharmacy and law and this, that and the other thing, but it didn’t go anywhere,” Myers said. “I guess Dad’s blood got into me because there was really nothing else I wanted to do. Besides, I liked what he was doing and the way he was doing it. I always felt the same way he did with people.”

A Lake Elementary School and Technical High School grad, Myers earned his bachelor’s degree from prestigious, historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C., where Kenneth followed him. After graduating from San Francisco College of Mortuary Science, he worked in an Oakland funeral home three years. He intended staying on the west coast, but events soon changed his mind. Frustrated by an employer who resisted the modern methods Robert tried introducing, he then got word that W.L. had lost his chief assistant and could use a hand back home. The clincher was America’s entrance in World War II. Robert got a deferment from the military in light of the essential services he performed.

From 1943 until the mid-’60s, Myers had a ringside seat for some fat times in Omaha’s black community. Those and earlier halcyon days are long gone. Recalling all that the area once was and is no more is depressing.

“It is because I can think back to the Dreamland Ballroom and all the big bands that used to come there when we were kids. We used to stand outside on summer nights. They’d have a big crowd out there. The windows would be open and we could hear all this good music and, ohhhh, we’d just sit back and enjoy every minute of it. Yeah, I think back on all those things. How at night we used to stroll up and down 24th Street. Everybody knew everybody pretty much. We’d stand, greet and talk. You didn’t have to worry about anything. Yeah, I miss all that part.”

The northside featured any good or service one might seek. Social clubs abounded.

“We had a lot of black professional people there — doctors, lawyers, dentists, pharmacists. They intermingled with the white merchants, too,” he said. Then it all changed. “Between the riots’ destruction and the North Freeway’s division of a once unified community, it started going down hill. And, in later years, after the civil rights movement brought in open housing laws and our people had a chance to better themselves, many began moving out of the area’s substandard housing.”

He said northeast Omaha might have staved-off wide-spread decline had blacks been able to get home loans from banks to upgrade existing properties, but restrictive red lining practices prevented that. Through it all — the riots, white flight, the black brain drain, gang violence — Myers

Funeral Home remained.

“No, we never considered moving away from there. Even though North 24th Street was pretty well shot, the churches were still central to the life of the community. People still came back into the area to attend church,” he said.

Emboldened by the civil rights movement, Robert and Bertha put themselves and their careers on the line to improve conditions. As a lifetime member of the NAACP and Urban League, he supported equal rights efforts. As a founder of the 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties) he organized and joined picket lines in the struggle to overturn racial discrimination. As a member of Mayor A.V. Sorensen’s Biracial Commitee and Human Relations Board and a director of the National Association of Christians and Jews, he promoted racial harmony. As the first black on the Omaha Board of Education (1964-1969), he fought behind the scenes to create greater opportunities for black educators.

With blacks still denied jobs by some employers, refused access to select public places and prevented from living in certain areas, Myers was among a group of black businessmen and ministers to form the 4CL and wage protest actions. The short-lived group initiated dialogues and broke down barriers, including integrating the Peony Park swimming pool. In his 4CL role, he went on the record exposing Omaha’s shameful legacy of restrictive housing covenants.

In a 1963 Omaha Star article, Myers is quoted as saying, “The wall of housing segregation” here is “just as formidable as the Berlin Wall in Germany or the Iron Curtain in Russia.” Labeling Omaha as the “Mississippi of the North,” he said the attitudes of realtors is “one of down right ghetto planning.” He and Bertha raised the issues of unfair housing practices in a personal way when they went public with their ‘60s ordeal searching for a ranch-style home in all-white districts. Realtors steered them away, some discreetly, others bluntly. The Myers finally resorted to using a front — a sympathetic white couple — for building a new residence in the Cottonwood Heights subdivision. When the Myers were revealed as the actual owners, a fight ensued. Subjected to threats and insults, they endured it all and stayed.

“That’s what my dad gave me an education for — to not accept these things. To see it for what it’s worth and to do something about it,” said Myers, who replied to a developer’s offer to move elsewhere with — “You don’t assign us a place to live.”

In a letter to the developer, Myers wrote, “Let me remind you that this is America in 1965 and…you must accept the fact there are some things money, threats or circumstances cannot change. We knew we could expect some trouble, we just figured it was part of the price we have to pay for living in a new area.”

Myers also worked for change from the inside as a member of the Omaha school board. The board had a lamentable policy that largely limited the hiring of black teachers to substitute status or, if hired full-time, placed them only in all-black schools and blocked promotion to administrative ranks. Even black educators with advanced degrees were routinely shut out.

“That was my wife’s situation. After she finished Northwestern University School of Music she couldn’t get a job here. She had to go to Detroit,” he said. Bit by bit, he got OPS to relax its policies. “The majority of school board members were in the frame of mind that they saw the unfairness of it. I was the catalyst, so to speak. All my work was done in the background in what’s called the smoke-filled back room.”

Advocating for change in a period of raging discontent brought Myers unwanted attention. He got “flak” from blacks and whites — including some who thought he was pushing too hard-too fast and others who alleged he was moving too soft-too slow. “I became something of a hot potato,” he said. “I thought I was independent and could do what I wanted because I didn’t have to rely on whites for business, but I found out people in my own community could get to me.”

The experience led Robert to retreat from public life. At least he had the satisfaction of knowing he’d carried on where his father left off. An anecdote Myers shared reveals how much his father’s approval meant to him.

“I handled a service one time when Dad was out sick. This was before my brother had joined us, so everything fell on me. I was scared,” he said. “There’s a lot to deal with. The mourners. The minister. The choir. The pallbearers. The employees. And you’re in charge of the whole thing. The whole operation has got to jell with just the right timing — from when to cue the mourners to exit to what speed the cars are to be driven. It’s all done silently — with expressions and gestures.

“Well, we went through the whole service OK. Later, a friend of the family told me. ‘Your old man told me to keep an eye on you and to watch everything you do and report back to him.’ He said he told my dad “everything was perfect — that I handled things just the way he would have’ and that my dad said, ‘That’s all I wanted to know.’ So, in that respect, Dad was still watching over me. It made me feel good to know I’d pleased him.”

Related Articles

- Woman Claims ‘Death at a Funeral’ Ripped Off Her Real-Life Funeral Nonsense (cinematical.com)

- A Dying Industry to Die For (fool.com)

- Home funerals making a comeback (nj.com)

The Two Jacks of the College World Series

The College World Series underway in Omaha is a major NCAA athletic championship that attracts legions of fans from all over America and grabs gobs of national media attention. With this being the last series played at the event’s home these past 60 years, Rosenblatt Stadium, there’s been more fan and media interest than ever before, although a spate of rain storms actually hurt attendance at the start of this year’s series. Inclement weather or not, the series is a great big love-in with its own Fan Fest. But it didn’t used to be this way. Indeed, for the first three decades of the event, it was a rather small, obscure championship that garnered little notice outside the schools participating. Omaha cultivated the event when few others wanted or cared about it, and all that nurturing has resulted in practically a permanent hold on the event, which has strong support from the corporate community, from the City of Omaha, from service clubs, and from the local hospitality industry. Two key players in securing and growing the series have been a father and son, the late Jack Diesing Sr. and Jack Diesing Jr., and they are the focus of this short story that recently appeared in a special CWS edition of The Reader (www.thereader.com) called The Daily Dugout. I have another story on this site from the Dugout — it features Greg Pivovar, one of the colorful characters who can be found at the series.

The Two Jacks of the College World Series

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In 1967 the late Jack Diesing Sr. founded College World Series Inc. as the local nonprofit organizing committee for the NCAA Division I men’s national collegiate baseball championship. He led efforts that turned a small, struggling event into a major national brand for Omaha.

When son Jack Diesing Jr. succeeded him as president, the young namesake continued building the brand as Jack Sr. stayed on as chairman.

While the CSW is not a business, it’s a growing enterprise annually generating an estimated $40-plus million for the local economy. More than 300,000 fans attend and millions more watch courtesy ESPN.

Papa Diesing was around to see all that growth, only passing away this past March at age 92. Jack Jr. said his father, who saw the event’s potential when few others did, never ceased being amazed “by how it kept getting bigger and better. The phrase he always said is, ‘This just flabbergasts me.'”

His father inherited a dog back in 1963. Jack Sr. was a J. L. Brandeis & Sons Department Store executive. His boss, Ed Pettis, chaired the CWS. The event lost money nine of its first 14 years here. When Pettis died, Jack Sr. was asked to take over. He refused at first. No wonder. The CWS was rinky-dink. Nothing about it promised great things ahead. The crowds were miniscule. The interest weak. But under his aegis an economically sustainable framework was put in place.

What’s become a gold standard event had an unlikely person guiding it.

“When my father got involved with the College World Series he had never attended a baseball game in his life. He didn’t really want to do it but basically he agreed to do it because it was the right thing to do for the city of Omaha,” said Jack Jr. “Over a period of time he developed a love affair with not only what it meant for the fans but what it meant for the city and what it meant for the kids playing in it. He always was looking to do whatever we could do here to make the event better for the kids playing the games and the fans attending the games and for the community. And the rest is history.”

“I certainly grew up behind the scenes. I can’t say he was purposely grooming me into anything. It’s just that I was exposed to the College World Series ever since I moved back into town in 1975. I’d go to the games, I was involved in sports in school and still was an avid sports follower after I got back.”

Diesing said the same sense of civic duty and love of community that motivated his father motivates him.

He still marvels at his father’s foresight.

“One of the things people credited him for was having tremendous vision about how to set up the infrastructure and make sure we had an organization moving forward that would stand the test of time. And he thought it would make sense to carry on a tradition with his son following him, and that was another thing he was right about.”

His father not only stabilized the CWS but set the stage for its prominence by partnering with the city and the local business community to placate the NCAA by investing millions in Rosenblatt Stadium improvements to create a showcase event for TV.

College baseball coaching legend Bobo Brayton admired how Jack Sr. nurtured the CWS. “I think he was the single person that really kept the world series there in Omaha. I went to a lot of meetings with Jack, I know how he worked. First, he’d feed everybody good, give them a few belts, and then start working on ‘em. He was fantastic, just outstanding. It’s too bad we lost him…but, of course, Jack Jr. is doing a good job too.”

As intrinsic as Rosenbatt’s been to the CWS, Jack Jr. said his father knew it was time for a change: “He could see and did see the needs and the benefits to move into the future. Certainly, I’m the first person to understand the nostalgia, the history, the ambience surrounding Rosenblatt. It’s going to be different down at the new stadium, and it’s just a matter of everybody figuring out a way to embrace the different.”

Diesing has no doubt the public-private partnership his father fostered will continue over the next 25 years that Omaha’s secured the series for and well beyond. He’s glad to carry the legacy of a man, a city and an event made for each other.

Related Articles

- Rosenblatt Stadium memories will live on (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- College World Series: The 10 Greatest CWS Legends Omaha Has Ever Seen (bleacherreport.com)

- College World Series is Omaha’s party central (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- 1st game at new Omaha ballpark sells out in hours (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- The One That Got Away Is Still a Yankees Fan (nytimes.com)

A Mentoring We Will Go

Mentoring programs, whether community or school-based , along with mentoring done more informally, on one’s own, offer effective ways for reaching at-risk youth. The following story I did for The Reader (www.thereader.com) about 10 or 12 years ago profiles some mentoring efforts in my hometown of Omaha. I cannot recall much about the assignment other than the passion and commitment of the people involved as mentors to make a difference in young people‘s lives.

A Mentoring We Will Go

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

A sweltering June night in the inner city finds a rag-tag basketball game under way in the Adams Park Community Center gymnasium. Here, in this hot house of testosterone, a lone female watches from the sidelines, itching, like the men around her, for a chance to play.

Maurtice Ivy is a tall, poised woman of 31. She mingles easily with the crowd. A righteous sister perfectly accepted as one of the guys. And why not? She grew up a tomboy among them and is a bona fide player to boot. The former Central High School all-state performer was a collegiate basketball star with the Lady Huskers and played professionally long before TV discovered the women’s game.

This night, like so many before, she’s brought along a young man she regards as a son, Rickey Loftin. The lean, hard-bodied 16-year-old harbors big-time hoop dreams of his own. The junior-to-be at South High School is anxious to strut his stuff. When the pair finally do take the court, she feeds him the rock again and again, highlighted by a slick one-handed bounce pass from the top of the key to a driving Rickey in the lane. Count it. These two anticipate each other’s moves and moods more than mere teammates do. More like soulmates.

It’s that way off the court, too, where Ivy mentors Rickey. In that capacity she serves as friend, counsel, guide, nag and personal coach.

After the gym clears out she “fusses at” him about his showboating and points out a flaw in his shooting technique. He listens good-naturedly and adjusts his shot. “That’s it,” she says approvingly.

Maurtice Ivy

The pair first met when she coached an Omaha Housing Authority team he played on. They hit it right off, and three years later they’re nearly inseparable. She attends all his athletic and school events. She helped pay for a black college tour he attended in May and is looking to enroll him in summer basketball camps where he’ll be exposed to better coaching and competition. She’s been there for him at every turn, including a tragedy.

“A couple years ago Rickey called me up one morning and asked me to come get him,” Ivy recalls. “I was wondering why he wasn’t in school and he said, ‘My dad was shot and killed last night. The only person I want to be around right now is you.’ I was speechless. It took everything in me not to break down and cry. At that point, I hadn’t realized how I had impacted him as a coach. And I just felt like that God was placing him in my life for a reason, and I needed to pick up the ball and be as positive as I could be.

“Rickey was hurting and he really didn’t know how to deal with that. Since then, I’ve really played a role in his life. I just try to be a strong support system for him. Our relationship has truly grown over the years.”

Ivy is among thousands of adults in the Omaha metropolitan area who maintain a one-to-one mentoring relationship with an at-risk youth. What follows is an exploration of different mentoring relationships and how these relationships follow certain familiar patterns, yet retain their own individual dynamic. Of how mentoring brings adults, kids and resources together in often surprising ways. Of how good mentoring isn’t a magic elixer or quick fix, but an investment of time that pays off slowly but surely.

Who are mentors? They’re individuals lending the benefit of their experience to a younger person struggling to reach his/her potential. They can be parents, teachers, coaches, professionals, laborers or anyone with a commitment to making a difference in the life of a child.

Some, like Ivy, mentor on their own — as an extension of their life and work. Others do it through the growing number of formal mentoring programs offered by schools, community service agencies and corporations. For example, adults from all walks of life mentor students in Tom Osborne’s school-based Teammates program, currently serving the Lincoln Public Schools and now gearing to go statewide.

This surge in mentoring is part of a larger movement in which clearinghouse organizations like the National Mentoring Partnership provide training materials and funding referrals in support of local efforts. Several Omahans involved in mentoring, including Hanson, were delegates at a 1997 Presidential summit that examined the most effective ways adults can serve America’s youth. The summit launched the Colin Powell-led volunteer initiative, America’s Promise, a catalyst for linking adults with kids in positive, community-building ways like mentoring.

A Method to Mentoring

The needs of a specific community often dictate the shape mentoring takes. The Chicano Awareness Center’s Family Mentoring Project serves first-generation Hispanic-American families in south Omaha, meaning mentors like Maria Chavez must be a “big sister” to Diana Gonzalez, 12, as well as a bilingual liaison to the girl’s parents, Aman and Maria, as they deal with language, immigration, job, education and social service issues. Joe Edmonson’s Youth Outreach Program, housed in north Omaha’s Fontenelle Park Pavillion, gives kids the safety, discipline and nurturing the area’s gang-ridden streets do not. Edmonson builds kids’ minds and bodies via athletic, multi-media and recreation activities.

Programs generally try striking a balance between structure and spontaneity. The US West-sponsored Monarch Connection, matching employees with McMillan Magnet School students, awards achievement badges to kids completing community service projects with their mentors, and encourages participants to spend other leisure time together.

Some programs strive to be part of youths’ lives from elementary school through college, others target a shorter time frame. Scholarship and other financial aid is sometimes provided as an incentive for children to excel. To qualify for aid, kids must usually honor a signed agreement detailing certain standards of personal behavior and school performance.

Whatever its face, however, mentoring is seen by practitioners as one proven, prevention-based approach to the widespread problems facing America’s youth, although supporters agree it’s no panacea, much less substitute for quality parenting or professional counseling.

“I think in today’s society parents aren’t always there, and not necessarily because they don’t care or they’re bad. Economically, a lot of parents are put in positions where they have to work two or three jobs or opposite shifts. Part of the fabric of the family is missing. A lot of kids nowadays don’t learn at home about manners and etiquette, and about consequences and encouragement and those kinds of things,” says AOK’s

Michael Hanson. “Often we hear from teachers or case workers that a kid’s parents are gone all day. The key is we need to do a better job of linking kids to the adult world in a way that makes sense to them.

“I think mentoring is being recognized as something that’s happened for a long time, but it just wasn’t called that, and now we’re formalizing it and trying to add some structure to it. That’s why I think its powerful. It’s the basis for everything we do as social animals. We form relationships, and a mentor is a special kind of relationship. If we look back in our own lives we all had someone who helped us see something in ourselves we couldn’t see or helped us make a decision we might not have made.”

Hanson says today’s mentoring efforts attempt “to artificially recreate something that happens naturally” for most youths, but that doesn’t for others. Without mentoring, he feels, kids fall through the cracks. That’s why programs like AOK work with school counselors and social service experts to identify youths who could most benefit from a mentor. Typically, it’s a bright student underachieving due to personal/family difficulties.

Doing the Right Thing

Mentoring is also a form of community activism. Of citizen helping citizen. Of giving back. Although Maurtice Ivy works in west Omaha (at Career Design), she still resides and takes an active role in the near north side community she grew up in, coaching youth athletic teams, sponsoring a 3-on-3 basketball tournament and mentoring kids like Rickey. “As a young community leader it’s my obligation to try and make a pathway to make things better,” she says. “It’s all about trying to do the right thing. And it’s just remarkable how receptive kids are when they know you’re sincere and doing everything you can do to try and help them.”

She has seen the difference mentoring’s made for Rickey. Thanks in part to her tutelage, he’s harnessed his mental and physical gifts and become a top scholar-athlete with lofty dreams for the future. He can’t imagine life without her.

“We have like a bond between each other,” he says. “She’s helped me not only with my physical skills on the basketball court, but mentally too by helping me keep my focus in the game and on school. She inspires me to keep getting good grades. She’s made me see how I can get a scholarship to college. I’d like maybe to be an engineer or an accountant. She’s like my second mom. I feel comfortable calling her my step-mom.”

Ivy, single and childless, doesn’t pretend to be Rickey’s mother. Mentors sometimes tread a fine line between being a friend and usurping the parental role. When Ivy started working with Rickey, she sensed his mother, a single working parent of three, viewed her as a threat. “I can understand that,” Ivy says, “and I didn’t want it to be that way, so I would back off, but then I’d be there for him when he needed me. I told her basically, ‘View me as an extension of you.’ She’s done a wonderful job with him. His mom is now a lot more supportive of what I’m doing in his life. I just try to give him direction. I try to place him around individuals and resources that can give him the assistance he needs. I see the impact I’ve made in his life and that is truly the most rewarding thing. When I see him excelling, I feel joy. ‘There’s my boy!’”

In return, Rickey looks up to Ivy. “She’s a black independent woman. No one can force her to do anything she doesn’t want to. She’s athletic. She’s working on graduate school now. She gives me advice on anything I need to talk about. I feel like I can always depend on her,” he says.

Reaching Out and Giving In

Trust must be present before a mentoring bond can be cemented. Getting there involves a feeling-out process. It can be a daunting task reaching sullen kids who are already wary of adults. According to Hanson, “A lot times mentors are more scared of the relationship than kids are because it’s a big responsibility. And if they feel they’re not doing a good enough job or don’t know what to expect in terms of working with a young person, they’ll give up.”

Jeff Russell had two AOK mentors give up on him in junior high before being paired with a third, David Vana. Already burned twice, Jeff held back. “I was really hesitant about getting involved with another because I figured he wasn’t going to stick around for very long anyway,” Jeff, now 20, says.

Vana, an Inacom business analyst, felt the young man’s reluctance. “He didn’t have a whole lot of faith in the program based on his experiences with his first two mentors, so I think he was a little cautious before he warmed up to me. I think the previous mentors tried to push him, and with Jeff it just didn’t work because he had a tendency to rebel. Before I started giving him advice and stuff, I wanted him to trust me and accept me. I didn’t want to come down too hard on him, so we started doing things together like going to hockey games and we got comfortable with each other.”

Before Vana came into his life, Jeff was a juvenile delinquent in the making. After the death of his mother upon entering 5th grade, Jeff, who never knew his father, was raised by an aunt and uncle. Things were fine at home, but he was failing high school and hanging with a bad crowd, so counselors recommended him for mentoring. “The friends I had were not exactly…going anywhere. In fact, they’re still not anywhere,” he says. “One of them is in jail for murder. Another one has many drug convictions. Another one can’t hold a job. I was very fortunate to get out of it when I did.”

Upon first meeting Jeff, Vana was struck by his fatalistic attitude. “When I asked about college, he said, and I’ll never forget it, ‘People like me don’t go to college.’ That’s when I focused on building his self-esteem and confidence. He made a lot of progress. Jeff definitely is a success story.”

Jeff credits Vana and Vana’s wife Noreen for helping him turn things around. “They’ve been very influential in my life. Whenever I’d have a question — school-related, work-related, anything — I’d call and we’d talk. They’ve been there for me a lot. They really took time out for me.” With their help he applied himself, raising his GPA from 0.32 to 3.20 and graduating on time. Currently taking a break from his studies at Metro Community College, where he’s working toward an associate’s degree in horticulture, Jeff oversees a gardening crew at a private estate and hopes to one day have his own landscaping business/nursery. AOK is paying his college tuition.

When he looks back to where he was headed — a likely drop-out — he sees how far he’s come and where he yet aspires to go. “I could have very easily followed that path. I still could revert back to that path, but I just have to remind myself of my goals. This program showed me that if I do what I should do, I can actually get someplace in my life.”

Trial and Error

Even when mentoring works, there are still power struggles, communication gaps, unrealistic expectations and bumpy spots along the way. “You can’t just pull two people’s names out of a hat — a mentor and a mentee — and expect their personalities to mesh perfectly,” says Vana. “It’s important to remember every kid is different. You can’t apply some mentoring template to every relationship. If it isn’t working, recognize that and make a new match.”

Bad matches do occur. They’re bound to, since aside from a screening/interview process, pairings are based on instinct and educated guesses. “With some, there’s no chemistry there. Others walk a fine line, with neither side willing to get real close or comfortable. But there’s been some extremely good matches too,” says Roz Moyer, US West manager of Community Affairs/ Employee Relations and Monarch Connection director. She says when things don’t click or mentors quit, affected youth are reassigned until a solid match takes hold. The challenge then becomes regaining the child’s trust. It can take time.

Moyer says mentors often have a sense of failure even when the match succeeds and the child thrives. “I think part of that is the kids don’t run up and say, ‘Thank you, you did such a good job.’ I tell the mentors not to expect them to do that. You’ll see it in other ways — in the success they have in school or by a good word every once in a while. You just have to know you’re doing a good job.”

Monarch mentor Linda Verner, a US West Finance executive, has at times doubted the job she’s done with former McMillan and current North High student Carrie Laney, 15, whom she’s mentored since 1996. Verner says, “I really wasn’t sure how much I had to contribute.”

Carrie, though, is certain of Verner’s impact. “I went through a lot of family and school problems the last couple years and Linda gave me a lot of good advice. I can talk about a lot more things with her than I can with my parents. She’s always told me she’s proud of me. She boosted my self-esteem so I would believe in myself and strive to get good grades, and I did.” Carrie plans attending college, with a goal of becoming a pediatrician.

Verner says if mentors just stick with it, good things happen. “I did not understand how much I would get out of it. Part of it is the enjoyment of setting goals with a young person and then getting them accomplished and feeling like you’ve contributed a little bit something.”

Because mentoring doesn’t follow a formula, sponsors offer support when things come a cropper. “Mentors can get discouraged,” Hanson says. “The challenge is tempering their expectations, but at the same time maintaining a level of enthusiasm that will help keep them there for the long haul. We can help prepare them for the fact kids are not going to fall down on their knees and thank you for saving them. They may not even acknowledge you at all. I mean, some of the kids we work with really need a lot of social skills. We have to teach kids how to look a person in the eye, shake their hand and greet them.”

Since mentoring only works if both parties are active participants,sponsors stress why each person shares responsibility for the relationship.

“Both the mentor and the mentee have to have a willingness to forge ahead. Neither one can give up on making that connection and forming that relationship. As a mentor you have got to be dedicated enough to overcome obstacles and focus on that kid. As a kid you’ve got to be as committed as the mentor in attending all the functions and doing all the things needed to make this thing go,” says Moyer. “We tell the kids right off, ‘We cannot change your life. You have to change your life. We can help you. We can guide you. We can open some doors. But you have to be the one who makes the changes.”

“We do group activities so that we can see kids and mentors interact,” Hanson says. “The kid may only say five words to his mentor, and you can see the adult is getting frustrated. The mentor may come to me and say, ‘Gee, I’m just not making any progress. This kid doesn’t like me. I don’t know what to do.’ Yet, if the mentor quits coming to the meetings, the first thing the kid will do is say, ‘Where’s my mentor?’ They’ll know when you’re gone.”

New Beginnings

Karnell Perkins felt betrayed after his first three mentors gave up on him. His family was in disarray. School was a bust. Things looked bleak for the black north Omaha native before he finally connected with AOK mentors Mike and Judy Thesing, a white suburban Omaha couple who practically adopted him. It all started when Thesing, president of America First Financial Advisors, was recruited by America First Cos. head, Michael Yanney, to mentor kids at McMillan Junior High (now McMillan Magnet School) in Yanney’s Kids (the forerunner of AOK). Eventually, Thesing was assigned Karnell, by then a struggling Burke High student reeling from an increasingly chaotic home life and three unsuccessful matches.

Michael Yanney

“Before I met them I was bounced around from mentor to mentor,” Karnell says. “When I finally got Mike and Judy, they were different than the average mentor who sees their kids every once in a while for lunch or a movie or helping with their homework. But Mike and Judy, for sure, go above and beyond. They’ve meant a lot to me.”

But as the problems in Karnell’s family deepened, he was in danger of flunking out of school. “His unwed mother was on the fringe of being in trouble with the law for numerous reasons. There was never any role modeling or anybody who really cared what he was doing or how he was doing. There was never any money or transportation. He was the oldest of three boys and he felt responsible for his brothers. He worked after school, so school was the last thing he focused on,” Thesing explains.

That’s when Karnell’s mentors dramatically intervened in his life. “My wife and I took him by the ears and made him live with us the latter part of his senior year. We put together a program he was to abide by in order to get through school. We made sure he had transportation and that his academic requirements were fulfilled before he could go do anything else. It was a disciplinary and structural change for him, but I think he realized at that point that we really cared and were willing to do whatever it took to make sure he had every opportunity to be successful.”

The change in environment was profound, and so were the changes in Karnell. “I went from one culture in north Omaha to a totally different culture in west Omaha, but race was never an issue. Mike and Judy let me know there’s a better way of life than what I had. They gave me stability. They kind of became like mom and dad.”

There was a period of adjustment, however. “At first things were a little chilly, but as time went on and we did stuff together and he got to know us, things just evolved,” Thesing says. There’ve been road bumps since, like the time Karnell, now a University of Nebraska-Lincoln student, sloughed off in his studies and was placed on academic probation. He soon felt the wrath of the intense, goal-oriented Thesing. Karnell, who describes himself as “laidback,” says Thesing’s constant “do-it-now” prodding got old. “Sometimes I was like, ‘Hey dude, chill out.’ But I do know he’s trying to help me accomplish good things. If I didn’t have him I think I’d be a slacker.”

Thesing says working through such differences is worth the end result. “It can be pretty frustrating, but if you can get past those barriers and develop a real solid relationship, the reward is you’ll be making a difference in someone’s life.” He’s seen the change: “I’ve always been proud of Karnell, but I’ve seen him mature quite a lot. Now he realizes the value of an education, the value of hard work and the value of discipline. By most measures, especially given his background, he’s doing outstanding.”

Karnell, 21, pulled his grades up enough to not only graduate high school, but earn a full college scholarship — courtesy of AOK. The finance major is on pace to graduate from UNL next year, which will mark a family milestone. “No one in my family has ever graduated college,” he notes. “Now, it’s like I’ve set a standard for my brothers. William and Langston are planning to go too. That makes me feel really good.”

Having seen the ups and downs of mentoring, he feels an adult must first earn a child’s confidence before being called a friend: “You need a person who’s sincere. You can’t be fake. You have to sincerely care about kids and want to help out, even if you don’t have all the answers. You have to seriously lead by example. And you have to want to do it from the heart.”

Thesing agrees, adding: “These kids just need someone that cares about them. A lot of them have gone through their whole life without anyone really caring. Throwing money at these things is not really the answer. It’s got to be a genuine commitment of time. Kids need your time more than anything else, and the earlier you get involved the better.”

He expects to remain a part of Karnell’s life for as long as he’s around. “I see it as a lifetime commitment. I look at him as a son almost.” The Thesings have, in fact, gained partial custody of Karnell’s youngest brother, Langston, 10, who now lives with them.

“He really likes being there,” Karnell says. “Every night I go to sleep I thank God for Mike and Judy…and all the people who’ve helped us out. Their hearts are so big.”

Related Articles

- Youth Mentors Needed in Greater S.E. DC! (socialactions.net)

- Mentors discover the power (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Programs in Detroit, beyond seek minority mentors (thegrio.com)

- First lady urges more people in US to mentor youth (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Been mentored? Pass it forward! (studenttransitionissues.wordpress.com)

- Women Mentoring Women (rejoicingrebecca.com)

- Even Mentors Need Mentoring (togetheragainstviolence.wordpress.com)

A force of nature named Evie: Still a maverick social justice advocate at 100

Spend even a little while with Evie Zysman, as I did, and she will leave an impression on you with her intelligence and passion and commitment. I wrote this story for the New Horizons, a publication of the Eastern Nebraska Office on Aging. We profile dynamic seniors in its pages, and if there’s ever been anyone to overturn outmoded ideas of older individuals being out of touch or all used up, Evie is the one. She is more vital than most people half or a third her age. I believe you will be as struck by her and her story as I was, and as I continue to be.

A force of nature named Evie:

Still a maverick social justice advocate at 100

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

When 100-year-old maverick social activist, children’s advocate and force of nature Evelyn “Evie” Adler Zysman recalls her early years as a social worker back East, she remembers, “as if it were yesterday,” coming upon a foster care nightmare.

It was the 1930s, and the former Evie Adler was pursuing her graduate degree from Columbia University’s New York School of Social Work. As part of her training, Zysman, a Jew, handled Jewish family cases.

“I went to a very nice little home in Queens,” she said from her art-filled Dundee neighborhood residence. “A woman came to the door with a 6-year-old boy. She said, ‘Would you like to see his room?’ and I said, ‘I’d love to.’ We go in, and it’s a nice little room with no bed. Then the woman excuses herself for a minute, and the kid says to me, ‘Would you like to see where I sleep?’ I said, ‘Sure, honey.’ He took me to the head of the basement stairs. There was no light. We walked down in the dark and over in a corner was an old cot. He said, ‘This is where I sleep.’ Then he held out his hand and says, ‘A bee could sting me, and I wouldn’t cry.’

“I knew right then no child should be born into a living hell. We got him out of that house very fast and got her off the list of foster mothers. That was one of the experiences that said to me: Kids are important, their lives are important, they need our help.”

Evie Zysman

Imbued with an undying zeal to make a difference in people’s lives, especially children’s lives, Evie threw herself into her work. Even now, at an age when most of her contemporaries are dead or retired, she remains committed to doing good works and supporting good causes.

Consistent with her belief that children need protection, she spent much of her first 50 years as a licensed social worker, making the rounds among welfare, foster care and single-parent families. True to her conviction that all laborers deserve a decent wage and safe work spaces, she fought for workers’ rights as an organized union leader. Acting on her belief in early childhood education, she helped start a project that opened day care centers in low income areas long before Head Start got off the ground; and she co-founded, with her late husband, Jack Zysman, Playtime Equipment Co., which sold quality early childhood education supplies.

Evie developed her keen social consciousness during one of the greatest eras of need in this country — the Great Depression. The youngest of eight children born to Jacob and Lizzie Adler, she grew up in a caring family that encouraged her to heed her own mind and go her own way but to always have an open heart.

“Mama raised seven daughters as different as night and day and as close as you could possibly get,” she said. “Mama said to us, ‘Each of you is pretty good, but together you are much better. Remember girls: Shoulder to shoulder.’ That was our slogan. And then, to each one of us she would say, ‘Don’t look to your sister — be yourself.’ It was taken for granted each one of us would be ourselves and do something. We loved each other and accepted the fact each one of us had our own lives to live. That was great.”

Even though her European immigrant parents had limited formal education, they encouraged their offspring to appreciate the finer things, including music and reading.

“Papa was a scholar in the Talmud and the Torah. People would come and consult him. My mother couldn’t read or write English but she had a profound respect for education. She would put us girls on the streetcar to go to the library. How can you live without books? Our home was filled with music, too. My sister Bessie played the piano and played it very well. My sister Marie played the violin, something she did professionally at the Loyal Hotel. My sister Mamie sang. We would always be having these concerts in our house and my father would run around opening the windows so the neighbors could also enjoy.”

Then there was the example set by her parents. Jacob brought home crates filled with produce from the wholesale fruit and vegetable stand he ran in the Old Market and often shared the bounty with neighbors. One wintry day Lizzie was about to fetch Evie’s older siblings from school, lest they be lost in a mounting snowstorm, when, according to Evie, the family’s black maid intervened, saying, “You’re not going — you’re staying right here. I’ll bring the children.’ Mama said, ‘You can go, but my coat around you,’ and draped her coat over her. You see, we cared about things. We grew up in a home in which it was taken for granted you had a responsibility for the world around you. There was no question about it.”

Along with the avowed obligation she felt to make the world a better place, came a profound sense of citizenship. She proudly recalls the first time she was old enough to exercise her voting right.

“I will always remember walking into that booth and writing on the ballot and feeling like I am making a difference. If only kids today could have that feeling when it comes to voting,” said Evie, a lifelong Democrat who was an ardent supporter of FDR and his New Deal. When it comes to politics, she’s more than a bystander — she actively campaigns for candidates. She’ll be happy with either Obama or Clinton in the White House.

When it came time to choose a career path, young Evie simply assumed it would be in an arena helping people.

“I was supposed to, somehow,” is how she sums it up all these years later. “I believed, and I still believe, that to take responsibility as a citizen, you must give. You must be active.”

For her, it was inconceivable one would not be socially or politically active in an era filled with defining human events — from millions losing their savings and jobs in the wake of the stock market crash to World War I veterans marching in the streets for relief to unions agitating for workers’ rights to a resurgence of Ku Klux Klan terror to America’s growing isolationism to the stirrings of Fascism at home and abroad. All of this, she said, “got me interested in politics and in keeping my eyes open to what was going on around me. It was a very telling time.”

Unless you were there, it’s difficult to grasp just how devastating the Depression was to countless people’s pocketbooks and psyches.

“It’s so hard for you younger generations to understand” she told a young visitor to her house. “You have never lived in a time of need in this country.” Unfortunately, she added, the disparity “between rich and poor” in America only seems to widen as the years go by.

With her feisty I-want-to-change-the-world spirit, Evie, an Omaha Central High School graduate, would not be deterred from furthering her formal education and, despite meager finances, became the first member of her family to attend college. Because her family could not afford to send her there, she found other means of support via scholarships from the League of Women Voters and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where the Phi Betta Kappa earned her bachelor’s degree.

“I knew that for me to go to college, I had to find a way to go. I had to find work, I had to find scholarships. Nothing came easy economically.”

To help pay her own way, she held a job in the stocking department at Gold’s Department store in downtown Lincoln. An incident she overhead there brought into sharp relief for her the classism that divides America. “

One day, a woman with a little poodle under her arm came over to a water fountain in the back of the store and let her dog drink from it. Well, the floorwalker came running over and said, ‘Madam, that fountain is for people,’ and the woman said, ‘I’m so sorry, I thought it was for the employees.’ That’s an absolutely true story and it tells you where my politics come from and why I care about the world around me and I want to do something about it.”

Her undergraduate studies focused on economics. “I was concerned I should understand how to make a living,” she said. “That was important.” Her understanding of hard times was not just of the at-arms-length, ivory-tower variety. She got a taste of what it was like to struggle when, while still an undergrad, she was befriended by the Lincoln YWCA’s then-director who arranged for Evie to participate in internships that offered a glimpse into how “the other half lived.” Evie worked in blue collar jobs marked by hot, dark, close work spaces.

“She thought it was important for me to have these kind of experiences and so she got me to go do these projects. One, when I was a sophomore, took me in the summer to Chicago, where I worked as a folder in a laundry and lived in a working girls’ rooming house. There was no air conditioning in that factory. And then, between my junior and senior years, I went to New York City, where I worked in a garment factory. I was supposed to be the ‘do-it’ girl — get somebody coffee if they wanted it or give them thread if they needed it, and so forth.

“The workers in our factory were making some rich woman a beautiful dress. They asked me to get a certain thread. And being already socially conscious, I thought, ‘I’ll fix her,’ and I gave them the wrong thread,” a laughing Evie recalled, still delighted at the thought of tweaking the nose of that unknown social maven.

Upon graduating with honors from UNL she set her sights on a master’s degree. First, however, she confronted misogyny and bigotry in the figure of the economics department chairman.

“He said to me, ‘Well, Evelyn, you’re entitled to a graduate fellowship at Berkeley but, you know, you’re a woman and you are a Jew, so what would you possibly do with your graduate degree when you complete it?’ Well, today, you’d sue him if he ever dared say that.”

Instead of letting discrimination stop her, the indomitable Evie carried-on and searched for a fellowship from another source. She found it, too, from the Jewish School of Social Work in New York.

“It was a lot of money, so I took it,” she said. “I had my ethic courses with the Jewish School and my technical courses with Columbia,” where she completed her master’s in 1932.

As her thesis subject she chose the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, one of whose New York factories she worked in. There was a strike on at the time and she interviewed scores of unemployed union members who told her just how difficult it was feeding a family on the dole and how agonizing it was waking-up each morning only to wonder — How are we going to get by? and When am I ever going to work again?

As a social worker she saw many disturbing things — from bad working conditions to child endangerment cases to families struggling to survive on scarce resources. She witnessed enough misery, she said, “that I became free choice long before there was such a phrase.”

Her passion for the job was great but as she became “deeply involved” in the United Social Service Employees Union, she put her first career aside to assume the presidency of the New York chapter.

“I could do even more for people, like getting them decent wages, than I could in social work.” Among the union’s accomplishments during her tenure as president, she said, was helping “guarantee social workers were qualified and paid fairly. You had to pay enough in order to get qualified people. We felt if you, as social workers, were going to make decisions impacting people’s lives, you better be qualified to do it.”

Feeling she’d done all she could as union head, she returned to the social work field. While working for a Jewish Federation agency in New York, she was given the task of interviewing Jewish refugees who had escaped growing Nazi persecution in Germany and neighboring countries. Her job was to place new arrivals with the appropriate state social service departments that could best meet their needs. Her conversations with emigres revealed a sense of relief for having escaped but an even greater worry for their loved ones back home.

“They expressed deep, deep concern and deep, deep sadness and fear about what was going on over there,” she said, “and anxiety about what would happen to their family members that remained over there. They worried too about themselves — about how they would make it here in this country.”

A desire to help others was not the only passion stoked in Evie during those ”wonderful” New York years. She met her future husband there while still a grad student. Dashing Jack Zysman, an athletic New York native, had recently completed his master’s in American history from New York University. One day, Evie went to some office to retrieve data she needed on the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, when she met Jack, who was doing research in the very same office. Sharing similar interests and backgrounds, the two struck up a dialogue and before long they were chums.

The only hitch was that Evie was engaged to “a nice Jewish boy in Omaha.” During a break from her studies, she returned home to sort things out. One day, she was playing tennis at Miller Park when she looked across the green and there stood Jack. “He drove from New York to tell me I was definitely coming back and that I was not to marry anybody but him.” Swept off her feet, she broke off her engagement and promised Jack she would be his.

After their marriage, the couple worked and resided in New York, where she pursued union and social work activities and he taught and coached at a high school. Their only child, John, today a political science professor at Cal-Berkeley, was born in New York. Evie has two grandchildren by John and his wife.

Along the way, Evie became a New Yorker at heart. “I loved that city,” she said. Her small family “lived all over the place,” including the Village, Chelsea and Harlem. As painful as it was to leave, the Zysmans decided Omaha was better suited for raising John and, so, the family moved here shortly after World War II.

Soon the couple began Playtime Equipment, their early childhood education supply company. The genesis for Playtime grew out of Evie’s own curiosity and concern about the educational value of play materials she found at the day care John attended. When the day care’s staff asked her to “help us know what to do,” she rolled up her sleeves and went to work.

She called on experts in New York, including children’s authors, day care managers and educators. When she sought a play equipment manufacturer’s advice, she got a surprise when the rep said, “Why don’t you start a company and supply kids with the right stuff?” It was not what she planned, but she and Jack ran with the idea, forming and operating Playtime right from their home. The company distributed everything from books, games and puzzles to blocks and tinker toys to arts and crafts to playground apparatus to teaching aids. The Zysmans’ main customers were schools and day cares, but parents also sought them out.

“I helped raise half the kids in Omaha,” Evie said.

The Zysman residence became a magnet for state and public education officials, who came to rely on Evie as an early childhood education proponent and catalyst. She began forming coalitions among social service, education and legislative leaders to address the early childhood education gap. A major initiative in that effort was Project AID, a program she helped organize that set-up preschools at black churches in Omaha to boost impoverished children’s development. She said the success of the project helped convince state legislators to make kindergarten a legal requirement and played a role in Nebraska being selected as one of the first states to receive the federal government’s Head Start program.

Gay McTate, an Omaha social worker and close friend of Zysman’s, said, “Evie’s genius lay in her willingness to do something about problems and her capacity to bring together and inspire people who could make a difference.”

Evie immersed herself in many more efforts to improve the lives of children, including helping form the Council for Children’s Services and the Coordinated Childcare Project, clearinghouses geared to meeting at-risk children’s needs.

The welfare of children remains such a passion of hers that she still gets mad when she thinks about the “miserable salaries” early childhood educators make and how state budget cuts adversely impact kids’ programs.

“Everybody agrees today the future of our country depends on educating our children. So, what do we do about it? We cut the budgets. Don’t get me started…” she said, visibly upset at the idea.

Besides children, she has worked with such organizations as the United Way, the Urban League, the League of Women Voters, the Jewish Council of Women, Hadassah and the local social action group Omaha Together One Community.

In her nearly century of living, she’s seen America make “lots of progress” in the area of social justice, but feels “we have a long way to go. I worry about the future of this country.”

Calling herself “a good secular Jew,” she eschews attending services and instead trusts her conscience to “tell me what’s right and wrong. I don’t see how you can call yourself a good Jew and not be a social activist.” Even today, she continues working for a better community by participating in Benchmark, a National Council of Jewish Women initiative to raise awareness and discussion about court appointments and by organizing a Temple Israel Synagogue Mitzvah (Hebrew, for good deed) that staffs library summer reading programs with volunteers.

Her good deeds have won her numerous awards, most recently the D.J.’s Hero Award from the Salvation Army and Temple Israel’s Tikkun Olam (Hebrew, for repairing the world) Social Justice Award.

She’s outlived Jack and her siblings, yet her days remain rich in love and life. “I play bridge. I get my New York Times every day. I have my books (she is a regular at the Sorenson Library branch). I’ve got friends. I have my son and daughter-in-law. I have my grandchild. What else do you need? It’s been a very full life.”

As she nears a century of living Evie knows the fight for social justice is a never-ending struggle she can still shine a light on.

“How would I define social justice?” she said at an Omaha event honoring her. “You know, it’s silly to try to put a name to realizing that everybody should have the same rights as you. There is no name for it. It’s just being human…it’s being Jewish. There’s no name for it. Give a name to my mother who couldn’t read or write but thought that you should do for each other.”

Related Articles

- Alberta foster care system under scrutiny (calgaryherald.com)

- Leading article: The care system needs a drastic overhaul (independent.co.uk)

- Feds share blame for child welfare system ‘chaos’ (cbc.ca)

The Smooth Jazz Stylings of Mr. Saturday Night, Preston Love Sr.

An unforgettable person came into my life in the late 1990s in the form of the late Preston Love Sr. He was an old-line jazz and blues player and band leader who was the self-appointed historian and protector of a musical legacy, his own and that of other African American musicians, that he felt did not receive its full due. Love was a live-life-to-its-fullest, larger-than-life figure whose way with words almost matched his musicianship. As I began reporting on aspects of Omaha’s African American community, he became a valuable source for me. He led me to some fascinating individuals and stories, including his good friend Billy Melton, who in turn became my good friend. But there was no one else who could compare to Preston and his irrepressible spirit.

I ended up writing five stories about Preston. The one that follows is probably my favorite of the bunch, at least in terms of it capturing the essence of the man as I came to know him. The piece originally appeared in the New Horizons. Aspects of this piece and another that I wrote for The Reader, which you can also find on this site, ended up informing a profile on Preston I did for a now defunct national magazine, American Visions. Links to that American Visions story can still be found on The Web. I fondly remember how touched I was listening to the rhapsodic praise Preston had for my writing in messages he left on my answering machine after the first few stories were published. After basking in his praise I would call him back to thank him, and he would go off again on a riff of adulation that boosted my ego to no end.

I believe he responded so strongly to my work because I really did get him and his story. Also, I really captured his voice and pesonality. And this man who craved validation and recognition appreciated my giving him his due.

Near the end of his life Preston hired me to write some PR copy for a new CD release, and I approached the job as I would writing an article. I’ve posted that, too.

The last story I wrote about Preston was bittersweet because it was an in memoriam piece written shortly after his death. It was a chance to put this complex man and his singular career in perspective one more time as a kind of tribute to him. A few years after his death I got to interview and write about a daughter of his he had out of wedlock, Laura Love, who is a fine musician herself. Her story can also be found on this site.

The Smooth Jazz Stylings of Mr. Saturday Night, Preston Love Sr.,

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

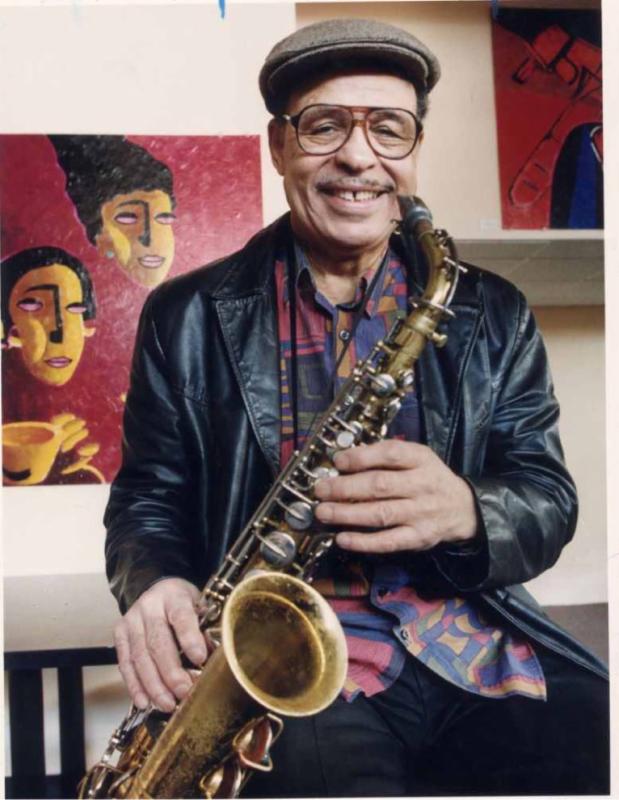

An early January evening at the Bistro finds diners luxuriating in the richly textured tone and sweetly bended notes of flutist-saxophonist Preston Love, Sr., the eternal Omaha hipster who headlines with his band at the Old Market supper club Friday and Saturday nights.

By eleven, the crowd’s thinned out, but the 75-year-old Love jams on, holding the night owls there with his masterful playing and magnetic personality. His tight four-piece ensemble expertly interprets classic jazz, swing and blues tunes Love helped immortalize as a Golden Era lead alto sax player and band leader.

Love lives for moments like these, when his band really grooves and the crowd really digs it: “There’s no fulfillment…like playing in a great musical environment,” he said. “It’s spiritual. It’s everything. Anything less than that is unacceptable. If you strike that responsive chord in an audience, they’ll get it too – with that beat and that feeling and that rhythm. Those vibes are in turn transmitted to the band, and inspire the band.”

His passion for music is shared by his wife Betty, 73, the couple’s daughter, Portia, who sings with her father’s band Saturdays at the Bistro and sons, Norman and Richie, who are musicians, and Preston Jr.

While the Bistro’s another of the countless gigs Love’s had since 1936 and the repertoire includes standards he’s played time and again, he brings a spontaneity to performing that’s pure magic. For him, music never gets tired, never grows old. More than a livelihood, it’s his means of self-expression. His life. His calling.

Music has sustained him, if not always financially, than creatively during an amazingly varied career that’s seen him: Play as a sideman for top territory bands in the late ‘30s and early ‘40s; star as a lead alto saxophonist with the great Count Basie Orchestra and other name acts of the ‘40s; lead his own highly successful Omaha touring troupe in the ‘50s; and head the celebrated west coast Motown band in the ‘60s and early ‘70s.

He’s earned rave reviews playing prestigious jazz festivals (Monterey, Montreux, Berlin). Toured Europe to great acclaim. Cut thousands of recordings, including classics re-released today as part of anthology series. Worked with a who’s-who list of stars as a studio musician and band leader, from Billie Holiday to Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles to Stevie Wonder. Performed on network television and radio. Played such legendary live music haunts as the Savoy and Apollo Theater.

After 61 years in the business, Love knows how to work a room, any room, with aplomb. Whether rapping with the audience in his slightly barbed, anecdotal way or soaring on one of his fluid sax solos, this vibrant man and consummate musician is totally at home on stage. Music keeps him youthful. Truly, he’s no “moldy fig,” the term boppers coined to describe musicians out-of-step with the times.

“As far as being a ‘moldy fig’…that’ll never happen. And if it does, then I’ll quit. I refuse to be an ancient fossil or an anachronism,” said Love. “I am eternally vital. I am energetic, indefatigable, It’s just my credo and the way I am as a person. I play my instruments as modern as anybody alive and…better than I’ve ever played them.”

Acclaimed rhythm and blues artist and longtime friend, Johnny Otis, concurs, saying of Love: “He has impeccable musicianship. He has a beautiful tone, especially on solo ballads, which is rare today, if it exists at all. He’s one of the leading lead alto sax players of our era.”

Otis, who lives in Sebastopol, Calif., is white. Love is black. The fact they’ve been close friends since 1941 shouldn’t take people aback, they say, but it does. “Racism is woven so deeply into the fabric of our country that people are surprised that a black and a white can be brothers,” Otis said. “That’s life in these United States.”

Love’s let-it-all-hang-out performing persona is matched by the tell-it-like-it-is style he employs as a recognized music authority who demands jazz and the blues be viewed as significant, distinctly African-American art forms. He feels much of the live jazz and blues presented locally is “spurious” and “synthetic” because its most authentic interpreters – blacks – are largely excluded in favor of whites.

“My people gave this great art form for posterity and I’m not going to watch my people and our music sold down the road,” he said. “I will fight for my people’s music and its presentation.”

Otis admires Love’s outspokenness. “He’s dedicated to getting that message out. He’s persistent. He’s sure he’s right, and I know he’s right.”

Love’s candor can ruffle feathers, but he presses on anyway. “No man’s a prophet in his hometown,” Love said. “Sometimes you have to be abrasive and caustic to get your point over.”

Orville Johnson, Love’s keyboardist, values Love’s tenacity in setting the record straight. “He’s a man that I admire quite a bit because of his ethics and honesty.”

Love has championed black music as a columnist with the Omaha World-Herald, host of his own radio programs and guest lecturer, teacher and artist-in-residence at colleges and universities.

With the scheduled fall publication of his autobiography, “A Thousand Honey Creeks Later,” by Wesleyan University Press, Love will have his largest forum yet. Love began the book in 1965 while living in Los Angeles (where he moved his family in 1962 during a lean period), and revised it through a succession of editors and publishers. He sees it as a career capstone.

“It’s my story and it’s my legacy to my progeny,” he said. “They’ll know what I’m like and about by the way I said things, if nothing more.”