Archive

Ex-Prizefighter and Con Turned-Preacher Man Morris Jackson Spreads the Good News

I knew the name Morris Jackson growing up because my older brother Dan was a boxing fan and I think he saw one of the grudge bouts between Jackson, the slick boxer, and Ron Stander, the Great White Hope slugger. Jackson was undeniably the superior boxer but it was Stander not Jackson who got a title shot against Joe Frazier. As the years went by I lost track of Jackson, only to read one day in the local daily about how he had gotten in trouble with the law and done time behind bars. There, he had a born again experience of such magnitude that after serving his time he went on to become a minister. His chosen ministry is poetic justice, too, as he pastors to incarcerated men. I finally got to meet and profile Jackson a few years ago. The story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) about Jackson and his transformation follows. My stories about Morris’ then-nemesis, Ron Stander, can also be found in this blog site, along with other stories about Omaha boxers, boxing coaches and gyms. Like most writers, I am always down for a good boxing story. There are several yet in me that I wish to tell and I am sure that others will reveal themselves when I least expect it.

Ex-Prizefighter and Con Turned-Preacher Man Morris Jackson Spreads the Good News

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In his best three-piece, GQ-style suit, Morris Jackson looks like just another slick do-gooder to prisoners seeing him for the first time at the Douglas County Correctional Facility, where he’s chaplain with Good News Jail and Prison Ministry. But the large man soon separates himself from the pack when he tells them he used to be a prizefighter. Rattling off the famous names he met inside the ring — Ron Stander, Ernie Shavers, Ron Lyle, Larry Holmes — usually gets their attention. If not, what he says next, does. “My number is 30398.” That’s right, this preacher man did time. The former convict now stands on the other side of the cell as a born-again Christian and International Assemblies of God-ordained minister.

His 1975 armed robbery conviction sent him to the Nebraska Men’s Reformatory for a term of three to nine years. He served 22 months, plus seven more on work release. But being locked away wasn’t enough to reform Morris. His rebirth only happened years later, after squandering his freedom in a fast life leading to perdition. Referring to that transformation, one of several makeovers in his life, is enough to make even hardcore recidivists listen to his message of redemption.

“Then they hang on every word you’ve got to say, because they see a change. They really can’t believe you were there once yourself. Having Christ in your life really makes a big difference. Actually, it’s almost a visible presence — in your eyes, in your demeanor, in your voice, in your conversation — that people can notice,” said Jackson, whose prison ministry work dates back to 1992.

He first returned to the correctional system doing mission work for northwest Omaha’s Glad Tidings Church, where he still worships today. Reliving his incarceration experience behind the secured walls made him anxious.

“The first time I went, it was with fear and trembling because the last place I wanted to be in was anybody’s jail, hearing the doors close behind me,” he said.

To his relief, though, he sensed he had found a calling as an evangelist to cons.

“It was just as if I was right where I was supposed to be. The words were there. The life. The testimony. The word of God. My studies. The first time I did a service in the county jail there were 66 men present and 44 of those professed faith in Jesus Christ when given the opportunity. I said, ‘Man, I like this. I could do this all the time.’ Like I tell people, ‘Be careful what you say, because God is listening.’ I’m exactly where God wants me to be and I’m doing exactly what he wants me to do.”

Jackson’s had many occasions to reinvent himself, stemming back to his Texas childhood. As a youth, he lived with his family in an upper middle class part of Dallas. Then, he found out the man he thought was his father was actually his step-father. His real father was killed when Jackson was a year-old. Soon after this revelation, his mother and step-father split up and his world unraveled again. His mother got custody of him and his sister, but she could only afford a place in the projects. Already distraught over the divorce and the discovery he’d been lied to, he expressed his rage on the streets, where fighting was a rite of passage and survival mechanism in an area ruled by gangs.

“In Dallas, in the projects, you either had to be a good fighter or a fast runner, and I never could run too fast. I went from being a person who would see a fight coming and move away from it, to initiating fights. If you’d so much as look at me wrong, I’d haul off and hit you. I was getting into three-four fights a week. It was crazy. I guess I was an angry young man. Yet, I considered myself a meek person. I describe a meek person as a steel fist in a velvet glove. I would do everything I could to get out of a fight, but when I got cornered and I had to fight, I never lost one. Sometimes, I lost my temper and did something stupid.”

During this time, he lived a kind of double life. He was a star high school football and basketball player and a regular churchgoer, but also a notorious gangsta. His mother had grown up in the church before drifting away. When she found religion again, she made Morris and his sister attend services. He chafed at the fire-and-brimstone admonitions hollered down from the pulpit.

“The church I was raised in, you never heard a lot about grace. It was a lot of dos and donts and laws. You don’t smoke…don’t chew…don’t drink…don’t mess with girls. Of course, when I came of age where I could make my own decisions, there was no way I could live that kind of life when everybody else was having fun and I wasn’t doing anything.”

When his rebellion got to be too much, his mother kicked him out of the house. He went to live with his sister, stealing food to help support themselves.

His mother relocated to Omaha, where she had family, and she sent for her unrepentant son, hoping he’d find himself here. For a time, he did. He even prayed to lose his hair’s-edge temper, and it did leave him. When a neighbor training for the Golden Gloves prodded the strapping Jackson to join him at the old Swedish Auditorium, the newcomer did and soon found a home in the sport. Recognizing his talent, veteran handlers Harley Cooper, Leonard Hawkins, Ronnie Sutton, Don Slaughter and Yano DiGiacomo variously worked with him at the Foxhole Gym.

In his first amateur bout, he laid out cold his hulking opponent in a Lincoln smoker. His very next fight pitted him against the man who proved to be his main nemesis — Ron “The Bluffs Butcher” Stander. From the late 1960s through the early 1970s, they met six times — four as amateurs and twice as pros — in highly competitive, well-attended bouts. “People came out to see us fight,” said Jackson. Their matches drew crowds of 6,000-7,000. Each took the measure of the other, although Stander, Omaha’s then-Great White Hope, usually came out on top. Stander took four of the contests, including one by KO, Morris won a decision and a sixth encounter ended in a controversial draw most felt should have been a Morris win.

“Every time I turned around, there was Morris. He was my biggest, toughest opponent,” Stander said.” “Yeah, we went at it quite a bit. We just happened to come along at the same time,” Jackson said.

The intense rivalry was tailor-made for fans as the fighters embodied the classic adage that styles make fights. Jackson was the boxer, Stander the puncher. Jackson relied on his feet. Stander, on his brawn. One was black, the other white. In the era of militant Muhammad Ali, Jackson was the closest thing Omaha had to a righteous Brother bringing down The Man. Stander, meanwhile, was a real-life Rocky who got his shot at the title in a 1972 bout with champ Joe Frazier.

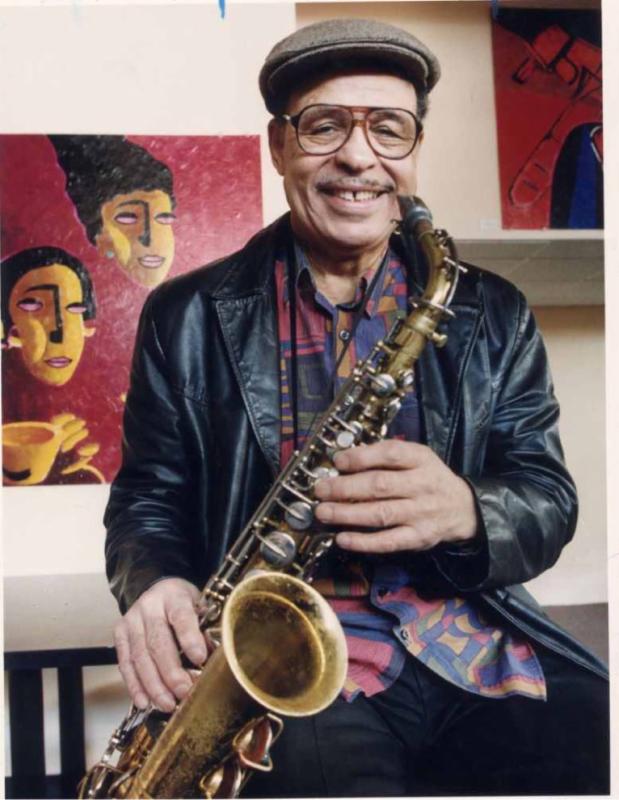

Morris Jackson in his fighting days

“I don’t know if I patterned myself after Ali, but I was somewhat like him because I would stick, move, think, box. I was light on my feet. But I wasn’t the type of person who talked a lot. I didn’t have any gimmicks or shuffles. I just got in and took care of business,” Jackson said.

The two long retired fighters reside in Omaha, but rarely mix. While their rivalry was too close for them to ever be friends outside the ring during their fighting days, they’ve always maintained the mutual respect warriors have for each other.

Stander is well aware of the transformation Jackson has undergone and admires his old foe for it. “He turned himself around. Yeah, he went from bad to good in a big way. God blessed him. God grabbed Morris by the neck and said, ‘Come over to me.’ Yeah, he’s a beautiful man now, I’ll tell ya.”

Ron Stander, known as the Butcher, went face to fist with Joe Frazier in Omaha in 1972. CreditUnited Press International

By most measures, Stander’s career surpassed Jackson’s, whose early promise ended in missed chances, bad matches, poor management, and too small takes. The familiar litany of a club fighter who never got his shot the way Stander did. Former Omaha matchmaker Tom Lovgren feels Jackson could have gone farther. Still, the fighter was once in line to join promoter Don King’s stable. He was a main eventer in Omaha’s last Golden Era of boxing. A two-time Midwest Golden Gloves champion, he compiled a 28-5-1 career pro record, including a KO of then-British Commonwealth champion Dan McALinden, a win Lovgren rates as the top by any Omaha boxer in the ‘70s. Jackson was also a sparring partner for ring legends Ron Lyle, Ernie Shavers, Joe Bugner and future champ Larry Holmes.

But then the good times ended. His run-in with the law came during a dry spell when the journeyman “couldn’t get any fights.” As he tells it, “I started running with some old friends who’d been in the joint and I was influenced by them to make some quick money in the hold up a Shaver’s food mart.” Once nabbed, he was almost grateful, he said, “because eventually somebody was going to get hurt.”

His crime spree was brief but telling and foreshadowed a later descent that threatened to land him back in jail or kill him.

While serving his stretch, Jackson studied Islam and became a Black Muslim. His dalliance with spirituality was short-lived, however. After getting out, he tried resurrecting his career but after three fights called it quits. Like many an ex-pug, he had few prospects beyond the ring and, so, he grabbed the first thing offered — bouncing at strip clubs.

“I got caught up in this lifestyle. I got to smoking marijuana and doing all the things that go with that lifestyle. My wife was working days and I was bouncing nights. We hardly ever saw each other. I was just kind of in limbo and that led to the brawls and the drinking and the drugs,” he said.

Morris Jackson today

He never imagined being saved. “No. If someone would have told me, I would have said, ‘Yeah, right, you’re crazy man. Give me some of what you’re smoking.’” It was his mother who finally pulled him from the brink and back into the fold of the church. In March 1983 she staged a one-woman intervention with her wayward son. “My mother came over to my house to talk to me about what my life was like and how Christ was calling me. She shared the gospel with me in such a way as I’d never heard it before. She spoke of God’s grace. How He loves you. How He has a purpose and a plan for your life. And how it’s up to you to accept and follow the path God has for you.” What came next can only be called salvation.

“I had this sense and I heard this voice that said. ‘The line is drawn in the sand and if you don’t make the decision now, you’ll never get another chance.’ I know just as sure as I’m sitting here today that if I wouldn’t have accepted Jesus Christ in my life, I’d be gone. I’d be dead. My mother prayed. We prayed. And the next day I went to church with her.”

Church bible classes led to college religious studies and, ultimately, his ordination. His first ministry was on the streets of north Omaha. Then came the prison gig. In the mid-’90s, then-Nebraska Governor Ben Nelson granted him a full pardon.

Now, he can’t imagine going back to that old life, although he keeps memories of it nearby as a reminder of where he came from. “There’s a peace in my life. Serenity. Stability. Certainty. It makes a difference when you come from darkness to light,” he said. “I know what my life used to be like. The turmoil, the uncertainty. Spinning my wheels. Living for the weekends. No purpose.”

Living his faith, which he loudly proclaims from the inscription above his home’s front door to the message on his answering machine, is his way of telling the good news. As he tells prisoners: “You’ve got to believe in something.” He’s seen enough cons turn their lives around to know his story is not an aberration.

The proud old fighter sees his ministry as his new battleground, only instead of knocking heads, he’s about saving souls and staying straight. “Most of my teaching is biblical principles applied to our lives. I’m still a warrior. Only now when I put on my armor and go to war every day, I don’t feel turmoil. My wars are fought in my prayer closet. I pray before I do anything,” he said.

But once a fighter, always a fighter. He repeated something Ron Stander said: “If they told us to lace ‘em up again, we’d go at it.” The Preacher versus the Butcher. Now wouldn’t that be a card?

Related Articles

- World Heavyweight Boxing Championship 1960-1975 (sportales.com)

- Meldrick Taylor vs. Julio Caesar Chavez: The Greatest Prizefight Ever? (bleacherreport.com)

- James Kirkland: Ex-Convict Will KO Japanese Prizefighter Within 7 Rounds Tonight (bleacherreport.com)

Heart and Soul, A Mutt and Jeff Boxing Story

This is another of my favorite boxing stories. I wrote it for the New Horizons. It profiles the same downtown Omaha boxing gym as featured in the House of Discipline story also recently posted here, only this time I concentrate more on the two old men who ran the gym, Kenny Wingo and Dutch Gladfelter, both of whom are now gone. I suppose my approach to this story and all the boxing stories I’ve done reveals influences of the boxing movies and documentaries and magazine articles I’ve been exposed to in a lifetime of being both thrilled and sickened by the sport. You’ll find on this blog site a handful of boxing articles I’ve written over the years, and there will be more to come.

Heart and Soul, A Mutt and Jeff Boxing Story

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

The heart and soul of Omaha amateur boxing can be found one flight above the dingy 308 Bar at 24th & Farnam. There, inside a cozy little joint of a gym, fighters snap punches at heavy bags, spar inside a makeshift ring, shadowbox and skip rope.

Welcome to the Downtown Boxing Club, a combination sweatshop and shrine dedicated to “the sweet science.” A melting pot for young Latino, African-American and Anglo pugilists of every conceivable size, shape and starry-eyed dream. They include die-hard competitors and fitness buffs. Genuine prospects and hapless pugs. Half-pint boys and burly men. They come to test their courage, sacrifice their bodies and impose their wills. For inspiration they need only glance at the walls covered with posters of boxing greats.

Whatever their age, ability or aspiration, the athletes all work out under the watchful eye of Kenny Wingo, 65, the club’s head coach, president and founder. The retired masonry contractor keeps tempers and egos in check with his Burl Ives-as-Big Daddy girth and grit. Longtime assistant Dutch Gladfelter, 76, is as ramrod lean as Wingo is barrel-wide. The ex-prizefighter’s iron fists can still deliver a KO in a pinch, as when he decked a ringside heckler at a tournament a few years back.

Together 17 years now, these two grizzled men share a passion for the sport that helps keep them active year-round. Wingo, who never fought a bout in his life, readily admits he’s learned the ropes from Gladfelter.

“He’s taught me more about this boxing business – about how to handle kids and how to run a gym – than anybody else I’ve been around,” Wingo said. “I’ve got a lot of confidence in his opinion. He’s a treasure.”

The lessons have paid dividends too, as the club’s produced scores of junior and adult amateur champions; it captured both the novice and open division team titles at the 1996 Omaha Golden Gloves tourney.

Ask Gladfelter what makes a good boxer and in his low, growling voice he’ll recite his school-of-hard-knocks philosophy: “Balance, poise, aggressiveness and a heart,” he said. “Knowing when, where and how to hit. Feinting with your eyes and body – that takes the opponent’s mind off what he’s doing and sometimes you can really crack ‘em. I try to teach different points to hit, like the solar plexus and the jaw, and to stay on balance and be aggressive counterpunching. You don’t go out there just throwin’ punches – you have to think a little bit too.”

Gladfelter’s own ring career included fighting on the pro bootleg boxing circuit during the Depression. The Overton, Neb., native rode freight train boxcars for points bound west, taking fights at such division stops as Cheyenne, Wyo., Idaho Falls, Idaho and Elko, Nev. (where the sheriff staged matches).

“I fought all over the Rocky Mountain District. You’d travel fifty miles on those boxcars for a fight. Then you’d travel fifty more to another town and you were liable to run into the same guy you just fought back down the line. They just changed their name a little,” recalls Gladfelter, who fought then as Sonny O’Dea.

He got to know the hobo camps along the way and usually avoided the railroad bulls who patrolled the freight yards. It was a rough life, but it made him a buck in what “were hard times. There wasn’t any work. Fightin’ was the only way I knew to get any money. I got my nose broke a couple times, but it was still better than workin’ at the WPA or PWA,” he said, referring to the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration and Public Works Administration.

After hanging up his gloves he began coaching amateur fighters in the early 1950s. He worked several years with Native American coach Big Fire. Gladfelter, who is part Lakota, hooked up with Wingo in the late ‘70s when he brought a son who was fighting at the time to train at the Downtown Boxing Club. Gladfelter and wife Violet have five children in all.

“After his boy quit, Dutch stayed on and started helping me with my kids,” said Wingo.With Gladfelter at his side Wingo not only refined his coaching skills but gained a new appreciation for his own Native American heritage (He is part Cherokee.).“He took me to several powwows,” said Wingo. “He taught me what a dream catcher is and the difference between a grass dancer and a traditional dancer. He’s given me maps where the Native Americans lived. I ask him questions. I do some reading. It’s interesting to me.”

A self-described frustrated athlete, Wingo grew up a rabid baseball (Cardinals) and boxing (Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson) fan in Illinois. He saw combat in Korea with the U.S. Army’s 7th Regiment, 3rd Division. After the war he moved to Omaha, where a brother lived, and worked his way up from masonry blocklayer to contractor.

He got involved with boxing about 25 years ago when he took two young boys, whose mother he was dating, to the city Golden Gloves and they insisted they’d like to fight too. Acting on the boys’ interest, he found a willing coach in Kenny Jackson. Hanging around the gym to watch them train sparked a fire in Wingo for coaching boxers.

“And I’ve kind of been hooked on it ever since. It gets in your blood,” he said.

Before long Wingo became Jackson’s cornerman, handling the spit bucket, water bottle, towel, et cetera, during sparring sessions and bouts. He increased his knowledge by studying books and quizzing coaches.

When Wingo eventually broke with Jackson, several fighters followed him to the now defunct Foxhole Gym. Soon in need of his own space, Wingo found the site of the present club in 1978 and converted empty offices into a well-equipped gym. He underwrote much of the early venture himself, but has in recent years used proceeds from pickle card sales to fund its operation. No membership fees are charged fighters, whose gloves, headgear and other essentials are provided free. He annually racks up thousands of miles on the club van driving fighters to tournaments around the Midwest and other parts of the nation. Except for fishing trips, he’s at the gym every weeknight and most Saturday mornings.

What keeps Wingo at it?

“I like working with the kids, number one. And when a kid does well it just makes you feel like all this is worthwhile. That you did your job and you got the best from him,” Wingo explains.

He enjoys helping young men grow as boxers and persons.

“When kids first come into the gym, they want to fight but they’re scared to death – because it is physical contact. But if you’re intimidated, you’ve got no chance. You try to teach them to be confident. I tell them from day one, and I keep tellin’ ‘em, that there’s three things that make a good fighter – conditioning, brains and confidence.”

Wingo feels boxing’s gotten a bad rap in recent years due to the excesses of the pro fight game.

He maintains the amateur side of the sport, which is closely regulated, teaches positive values like sportsmanship and vital skills like self-discipline.

The lifelong bachelor has coached hundreds of athletes over the years – becoming a mentor to many.

“Growing up without a father figure, Kenny’s really kind of filled that role for me,” notes Tom McLeod of Omaha, a former boxer who under Wingo won four straight city and Midwest Golden Gloves titles at 156 pounds. “We developed a real good friendship and a mutual trust and respect. I think Kenny’s a great coach and a great tactician too. He always told me what I needed to do to win the fight. He gave me a lot of confidence in myself and in my abilities. He took me to a level I definitely couldn’t of reached by myself.”

McLeod, 27, is one of several Downtown Boxing Club veterans who remain loyal to Wingo and regularly spar with his stable of fighters. Another is Rafael Valdez, 33, who started training with Wingo at age 10 and later went on to fight some 150 amateur and 16 pro bouts. Valdez’s two small sons, Justin and Tony, now fight for Wingo and company as junior amateurs.

“When my kids were old enough to start fighting,” said Valdez, “Kenny was the first one I called. He treats the kids great. There aren’t many guys who are willing to put in the amount of time he does.”

This multi-generational boxing brotherhood is Wingo’s family.

“Winning isn’t everything with me. Fellowship is,” Wingo said. “It’s the fellowship you build up over the years with fighters and coaches and parents too. I’ve got friends from everywhere and I got ‘em through boxing.”

A 1980 tragedy reminded Wingo of the hazards of growing too attached to his fighters. He was coaching two rising young stars on the area boxing scene – brothers Art and Shawn Meehan of Omaha – when he got a call one morning that both had been killed in a car wreck.

“I really cared about them. Art was an outstanding kid and an outstanding fighter. He was 16 when he won the city and the Midwest Golden Gloves. And his little brother Shawn probably had more talent than him. I’d worked with them three-four years. I picked ‘em up and took ‘em to the gym and took ‘em home. I took the little one on a fishing trip to Canada.”

Wingo said the Meehans’ deaths marked “the lowest I’ve ever been. I was going to quit (coaching).” He’s stuck with it, but the pain remains. “I still think about those kids and I still go visit their graves. It taught me not to get too close to the kids, but it’s hard not to and I still do to a certain extent.”

Quitting isn’t his style anyway. Besides, kids keep arriving at the gym every day with dreams of boxing glory. So long as they keep coming, Wingo and Gladfelter are eager to share their experience with them.

“We’ve done it together for 17 years now and we’re gonna continue to do it together for another 17 years. We both love boxing. What would we do if we quit?”

Related Articles

- What can be done to revitalize boxing? (timesunion.com)

- Golden Gloves…& golden heart (nydailynews.com)

- Canceled FX Boxing Show, ‘Lights Out,’ May Still Springboard Omahan Holt McCallany’s Career (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Gleason’s Gym: Next Amateur Shows are September 8 and 10, 2011 (unlimitedfightnews.com)

The Downtown Boxing Club’s House of Discipline

Most writers are drawn at one time or another to write about boxing. There’s just so much atmosphere around the sport and so many characters in it. I’ve done my share of stories on boxers over the years. Every now and then I get the hankering to do another. I’m overdue for one now. This was my first and still one of my favorites. I believe it was the very first assignment I did for an Omaha news weekly called The Reader (www.thereader.com). It was 1996 and I’ve been contributing articles to that paper ever since. The story concerns a classic urban boxing gym and its denizens. A sidebar or companion piece to this feature follows below.

The Downtown Boxing Club’s House of Discipline

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The Powers Building at 24th and Farnam holds a dingy little dive called the 308 Bar, whose sodden patrons belly up in pursuit of oblivion. Directly above the bar, yet a world apart, lies an athletic retreat where sturdy, modern-day spartans engage in a punishing physical regimen offering personal renewal and redemption. The first is a public house of pain. The second, a private house of discipline.

As dusk falls over downtown on a raw, windy day in February, a short but well-chiseled uniformed cop with dark, brooding good looks – Vince Perez – glides with cocksure grace towards the bar, which he bypasses to step inside a glass-fronted entrance next door. A shabby carpeted staircase – enclosed by water-stained and paint-peeled walls – takes him one flight up to a dim landing poised between empty offices. He follows a hallway to a bare, unvarnished pine door, behind which the rhythmic sounds of leather-lashed discipline reverberate.

Vince has once again arrived at 24th Street’s House of Discipline, otherwise known as the Downtown Boxing Club, where once inside he’s transformed from peace officer into fighting warrior. He says a warrior’s mentality is vital for entering a 20’ by 20’ ring to test yourself – one-on-one – against another man: “I think that’s the attitude you have to have to even get in the ring. Because that’s the way it is – you and him. The other guy wants to hurt you and it’s a challenge to see if your body is in good enough shape to try and withstand that.”

If your only boxing references are Hollywood-based, then the club will surprise you. The gym doesn’t ooze a moody “Raging Bull” atmosphere. The utilitarian brick-walled space is a non-profit center for amateur boxing – a closely regulated sport featuring many safeguards, such as mandatory headgear, that are worlds away from the anything-goes excesses of the pro fight game. Knockouts and serious injuries are rare here. No punch-drunk pugs hang around the gym. It doesn’t reek of stale sweat, urine and blood.

The gym lays out on one level, comprised of tidy work stations – the largest of which is a makeshift ring. Two medicine balls sit against a ring post. Outside the ropes four heavy bags hang in a row – like sides of beef – from chains fastened to the ceiling’s metal crossbeam. Speed bags stand at opposite ends of the room.

Banks of tall windows filter in natural light, which blends with the fluorescent tube lighting overhead to cast a vague yellowish tint over the place. Rusted radiators and exposed pipes run along one wall. Plastered to another wall are posters of famous pugilists and snapshots of club fighters – all silently bearing witness to the men at work there.

On any given night fighters train under the scrutiny of three men: Club founder, president, head coach and chief guru Ken Wingo, 64, wields a commanding authority befitting his Burl Ives-as-Big Daddy girth and grit; resident ring historian and assistant coach Dutch Gladfelter, who hopped freight trains to fight on the pro bootleg boxing circuit during the Depression, offers priceless pointers on feints, footwork and kill shots; and swarthy assistant coach John Glatgakos, a martial arts aficionado turned boxing buff, barks instructions in his thick Boston accent.

Wingo, who never fought a round in his life, describes himself as the ultimate frustrated athlete. He started coaching out of sheer love for the sport. He credits much of his boxing acumen to Dutch, a ramrod at 76 whose arms hang like thick lengths of lead pipe from his sloped shoulders.

Through mid-February the coaches paid special attention to Vince, Steve Ray, Andy Schrader and Craig Price, who were all preparing for the Midwest Golden Gloves Tournament (Feb. 16-17). Vince, who usually trains at Offutt Air Force Base under former world-class amateur boxer Kenny Friday, and the others fought gamely in the Midwest competition. But this story isn’t about wins or losses. It’s about how and why the men of the House of Discipline dedicate themselves to the rituals of the ring.

Wingo himself says, “Winning isn’t everything with me. Fellowship is.” Indeed, everyone at the club is treated the same. There’s a fraternal, democratic spirit that keeps many members coming back for years. A boxing brotherhood borne from grueling workouts and sparring sessions as well as long road trips to smokers and tourneys. For example, after sparring combatants touch gloves as a sign of sportsmanship, telling each other, “Good work.” There’s no animosity because it’s all about being pushed to your limits through clean hard work and competition. The sport breeds mutual respect because it takes courage to do what boxers do.

Club members can’t be pigeonholed. Most are men in their late teens or early 20s, although many boys compete in the junior ranks and an occasional woman works out there. There are family men like Vince, whose wife Heather is expecting the couple’s first child. A fireman named John. Blue-collar types like Steve and Craig. College students. Some members come purely for the exercise. All share a passion for boxing so intense they sacrifice long hours training for a chance at not so much winning a title or trophy as a measure of honor and comradeship not found anywhere else.

“I love coming down to the gym just for the camaraderie with the guys,” says Steve, who’s trained there since 1991. “We work out together and try to push each other and help each other out as much as we can.”

Rafael Valdez, 33, started training under Wingo as a 10-year-old junior amateur and a quarter-century later still spars with Wingo’s stable of fighters, who now include Rafael’s two small sons, Justin and Tony. He fondly recalls Wingo driving him and other youngsters to regional competitions, something Wingo still does today. After 150 amateur and 16 pro bouts, Rafael, an electrician, remains loyal to his friend and mentor.

The club is proving ground, training facility and sporting haven for boxers like Rafael. The physical and mental discipline learned there is all fighters have to fall back on when, as Craig says, you’re alone in the ring and wild with adrenalin and “somebody’s tryin’ to take your head off.”

Steve describes “the rush you get at the beginning, when you’re almost so scared you want to back out and you’ve got to push yourself to go on. It’s not fear of being hurt. It’s fear of losing and not doing well.” Of losing face among the brotherhood.

“Boxing’s the only sport in the world where the intent is to hurt the other guy, so there’s that little bit of trepidation there,” notes Wingo. “But if you’re intimidated, you’ve got no chance. You try to teach fighters to be confident. You say, “You can go with this guy, otherwise I wouldn’t have put you in there.’ You have to be a bit of a psychologist. You have to know when to build them up and when to settle them down.”

Rafael says “the nerves” usually fade after the first blows are struck, although doubts sometimes creep in, making you wonder, “‘What the hell am I doin’ in here?’” The answer is you’re trying to prove something. Not your manhood or prowess exactly, but more your heart, your skill, your determination – to meet the challenge and go the distance.

“For me, the sport of amateur boxing isn’t so much about who’s tougher, but more about how far I can take my body,” says Vince, who despite being 29 is a relative newcomer to the sport. “I’m more concerned about getting hurt on my job than in the ring. Boxing’s more a test of whether my style, my skills, my training are better than yours. For me, life is just a series of goals and this is just a goal I have.”

The eight-year Omaha Police Department veteran is a superb athlete who’s competed in baseball, basketball and bodybuilding. He started boxing in 1994 – drawn by the keen fitness it develops and the steep athletic challenges it poses: “It’s such a demanding sport. Unless you’ve tried it, you have no idea what it entails. You’re always on your feet, moving around. There’s a lot of hand-eye coordination. It truly is an art. And if you’re out of shape, two or three minutes can be an eternity.”

Wingo says, “It takes more hard work to go three two-minute rounds than it does for a football player to play a whole game because boxing’s non-stop action. Three things make a good boxer – conditioning, brains and confidence. You’ve got to pay the price to be a good boxer by training hard – getting up in the morning to go running when you’d much rather lay in bed. You’ve got to be smart and to be able to think on your feet.”

Although boxing’s macho ethic is what first appealed to Steve, a husband and father two, he’s grown to love the competition and the self-reliance required to compete. “You’ve got to do a lot of stuff, like running and dieting, when nobody’s around. If you’re not disciplined, you’ll never do it.” The 24-year-old drywall construction foreman says boxing’s’ given him a new resolve that’s carried over into other aspects of his life. “I’ve learned discipline from the gym. I didn’t do well in school. I was lazy. But how well I dedicated myself to boxing and how fast I learned boxing made me feel confident. Now I know if I set my mind to something I can accomplish it. It’s extended even to my work. I’ve excelled at work.”

Wingo admires the tenacity displayed by fighters like Steve and Vince – family men with demanding full-time jobs – who “have to pay a steep price” in order to box. “Anytime you love something like they love boxing, you’re going to be good at it,” he says.

Vince pays the price every day by juggling his patrolman’s schedule with classes at Bellevue University – where he pursues a dual major in sociology and psychology – with a workout that includes a 2-mile run, 40 minutes at the gym (usually on his lunch break) and 500 sit-ups. “It’s tough. I really have to prioritize my time.”

At the gym the fighters follow a routine that hardly varies from night to night. All arrive with a business-like attitude that’s relaxed enough for them to trade jibes with Wingo and company. Inside a cramped locker room they change from street clothes into assorted shorts, sweats, T-shirts and tank-tops. They wrap their hands with rolls of cloth. In the gym they stretch out on the scuffed wood floor and variously jump rope, work the Stairmaster or treadmill, ride the stationary bike and do push-ups or sit-ups.

They lace on gloves to hit the heavy bags – throwing furious combinations of straight lefts and rights, hooks, uppercuts and jabs – and drum away at the speed bags. When all the bags are going at once, the pounding, pulsing noise cascades around the room, pierced every few minutes by a ringing bell that calls time. The fighters climb in the ring to shadowbox – glancing at large mirrors propped against the windows – fighting their reflected images. And each takes turns punching bang pads (overstuffed mitts) worn by John, who exhorts them to “double up.”

Andy, a 132-pounder, is a sawed-off Andre Agassi-lookalike whose scrappiness covers limited boxing skills. Craig, a 6’4” 200-pounder, is an impulsive fighter and powerful puncher. His wicked shots rock the heavy bags and send shudders through John’s arms and shoulders. Steve, who has a model’s rakish body and classic face, and Vince, who always looks just right or as Wingo puts it – “slick” – even in sweats, are the smoothest, most stylish boxers. A blur of bobbing, weaving motion – shifting weight from hip to hip, blocking and throwing punches from different positions. What Steve (147 pounds) and Vince (125 pounds) lack in power, they make up for with quickness, precision, smarts.

On sparring nights, the guys grow tense – pacing the room, unable to keep still – just like before a fight. Wearing headgear and mouthpieces, they spar three two-minute rounds. The action’s fierce but lacks the no-holds bar fury of the real thing. Guys hold back just a little. This, after all, is “only” training. During each session a harsh rhythm and momentum builds as arms flail, gloves thump, heads butt, and feet shuffle in a muscular dance around the ring – the partners variously swinging, clinching and bounding at each other at the most unexpected angles.

Wingo, Dutch and John clamber onto the ring apron and, leaning against the frayed ropes, cajole and challenge them: “Go ahead, throw the jab…jab, jab, jab. There you go. Snap it off, that’s it. Stick with ‘em now. You need to relax – you’re stiff as a wedding cake. Think. Are you thinkin’?”

The object is to teach fighters basic boxing skills and refine these through repetition. If fighters learn their lessons well, they respond swiftly, instinctively in the ring to opponents’ tactics and coaches’ advice. It all gets back to the discipline that a taskmaster like Wingo imparts.

“Boxing teaches discipline,” Wingo explains. “A coach is like a sergeant in combat. When the sergeant hollers ‘Charge!’ everybody’s got to move. If someone hangs back, then that messes up the whole works. They’ve (fighters) got to do what you tell them without even thinking. They’ve got to have that respect for you. It takes a little more discipline than most kids have these days. When you find kids who want to do that, than you’ve got something special. If it helps the kids (outside boxing), that’s a bonus. If we win championships, that’s a bigger bonus.”

Sergeant Wingo drills his soldiers in the finer points of competition – both in and out of the ring – at his very own House of Discipline, where everyone marches to the same regimented beat. Call it the boxing rag.

Sidebar

The House of Discipline Boys at the Golden Gloves

©by Leo Adam Biga

You arrive opening night at the Midwest Golden Gloves and find the site is not some grimy, smoke-filled, boxing noir pit. Instead, the Mancuso Convention Center is a clean air-filtered, too-bright, flat, open expanse of institutional tile and plastic-chrome chairs.

A creaking wooden ring stands on risers near the back. Even when empty the severe, boundaried square seems an incongruous, slightly menacing presence in a space where trade shows and sales meetings normally unfold. And even though you know the tamer, safer brand of amateur boxing will be fought there, you can’t help but feel queasy thinking blood might splatter you at ringside.

The meager, subdued crowd is an insider’s, sportsman’s audience made up of coaches and fighters, die-hard fans and friends and relatives of competitors. The mood is expectant and convivial, with much handshaking and playful sparring. The small turnout is typical of local boxing events now, but a far cry from the days when the Gloves packed the Civic Auditorium.

Just behind the arena is a hall (complete with stage) turned assembly area, where fighters, coaches and officials mill before bouts with nervous, pent-up energy. Ken Wingo and his Downtown Boxing Club crew (save Vince Perez, who’s received a bye into the finals) hold down a corner of the stage to wait. Fighters deal differently with the waiting: Andy Schrader sits on a chair, pumping his legs to music on his Walkman’s headphones – getting “in the zone”; Steve Ray stays loose stretching; Craig Price sits and stands and paces with quiet intensity. All say they feel confident going in.

Wingo’s boys have a rough night of it. First,Schrader is retired (TKO’d) in round two after taking the second of two standing eight counts. Then the usually fluid Ray looks sloppy versus a rare left-handed foe and drops the decision. Wingo reminds both “there’s no disgrace in losing.” Finally, Price out-slugs a much shorter man to win a spirited bout that proves the crowd’s favorite. Later, Price’s red, puffy left eye is the only evidence he and the others have fought.

At ringside the fights flash by as bursts of pouncing torsos, thrashing arms and fast moving feet bouncing off the taut, worn tarp covering the floor. Many blows miss their mark, but with every solid impact a fighter’s face winces from the sting and his head whips back from the jolt – sending sweat, but thankfully not much blood, spraying over you. More than anything, each fighter tries imposing his will on his opponent inside that terribly small ring and is left spent from the effort. At the final bell – just like after sparring – men tap gloves, embrace and say “Good fight.”

Night two features the finals. The pre-fight rituals are the same. Perez and coach Kenny Friday arrive early since Perez’s 125-pound match tops the card. Even out of his policeman’s dress blues Perez carries himself with a certain aplomb. He looks every inch the fighting warrior with his grim face, swaggering walk and resplendent boxing garb – a black top and white trunks with blue trim showcasing his hard brown body.

He’s drawn the much younger, yet more experienced Rudy Mata. With Friday and Wingo in his corner and wife Heather in the crowd, Perez appears supremely confident despite this being only his fifth sanctioned fight. From the start Mata presses the action – boring in on Perez to pepper him with punches. Perez rebounds, using his mobility to escape serious trouble and his hand speed to bloody Mata’s nose, the crimson staining Perez’s white gloves. Entering the final two-minutes, it’s anybody’s fight.

Things turn quickly that last round when Mata comes out firing and traps Perez against the ropes. By the time Perez can counterattack, it’s too late. The bell sounds, ending the fight and the cop’s chance at victory. The two men fall into each other’s arms as the crowd sounds its approval. The decision, as expected, goes to Mata and the two warriors leave the ring proudly – knowing they’ve given a good effort.

Afterwards, Perez analyzes the fight: “After the first round I told Kenny (Friday), ‘I can beat this guy.’ Going into that last round I was real comfortable, but then I forgot my whole game plan. He stepped up the pressure and I stopped jabbing. I’m disappointed I lost, but I’m pretty happy I did this well.”

Later that evening Price loses the heavyweight championship to Emerson Chasing Bear who, true to his Native American name, nimbly pursues Price around the ring, slipping punches and assaulting him with jabs and crosses. It’s not even close. Afterwards, a dejected Price picks his performance apart: “My form wasn’t there. I wasn’t snapping my punches enough. I felt slow and clumsy. My head just wasn’t in it.”

Perez says his bout was probably his last, although he’ll still hit the bags and spar. He’s eying new athletic challenges now – like a triathlon (once he learns to swim). Schrader, Ray and Price plan on fighting a little while yet. Each echoes Price’s vow to get “back at the gym” and “work on what I did wrong.” None have ambitions of turning pro.

While boxing remains an avocation for these men, it’s also a way of life – just as the House of Discipline is not merely a gym, but a place for growth and self-discovery.

Related Articles

- Mike Harden commentary: Longtime love’s ring is kind boxers use (dispatch.com)

- Better boxing regulation needed: coroner (news.theage.com.au)

- Boxing: Good or Bad? (xtratime4.wordpress.com)

- When is an amateur an amateur and other such Olympic conundrums | Kevin Mitchell (guardian.co.uk)

- Canceled FX Boxing Show, ‘Lights Out,’ May Still Springboard Omahan Holt McCallany’s Career (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

RIP Preston Love Sr., 1921-2004, He Played at Everything

This is one of the last stories I wrote about Omaha jazz and blues legend Preston Love. It’s a tribute piece written in the days following his 2004 death. Trying to sum up someone as complex and multi-talented as Preston was no easy task. But I think after reading this you will have a fair appreciation for him and what was important to him. The piece originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). I actually ended up writing about him two more times, once on the occasion of the opening of the Loves Jazz & Arts Center, which is named in his honor and located in the hub of North Omaha‘s old jazz scene, and then again when profiling his daughter Laura Love, a singer–musician he fathered out of wedlock. You can find my other Preston Love stories along with my Laura Love story on this blog site.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader,com)

Lead alto sax player with Basie in the 1940s. Territory band leader in the ‘50s. Arranger, sideman, band leader for Motown headliners in the ‘60s. Studio session player. Recording artist. Music columnist. Radio host. Teacher, lecturer, author.

Until his passing from cancer at age 82, the voluble, playful, irrepressible, ingenious Preston Love wore all these hats and more during a long, versatile career. Around here, he may be best remembered for the easy way he performed at countless venues or the nostalgic, by-turns cantankerous tone of his Love Notes column or the adoring tributes and scalding rebukes he issued as host of his own jazz radio programs. Others might recall the crusading zeal he brought to his roles as college instructor, lecturer and artist-in-residence in spreading the gospel of jazz.

His curt dismissal of some local jazz musicians made him an egoist in some corners. In Europe, he was accorded the respect and adulation he never got at home. Yet, despite feeling unappeciated here, he often championed Omaha. It took the publication of his 1997 autobiography to make his resident jazz legend status resonate beyond mere courtesy to genuine recognition of his talents and credits.

For his well-received book, A Thousand Honey Creeks Later, My Life in Music from Basie to Motown (Wesleyan Press), Love drew on an uncanny memory to look back on a life and career spanning an enormous swath of American history and culture. It was a project he labored on for some 25 years and even though he still had a lot of living left in him, it served then, as it does now, as an apt summing-up and capstone for an uncommon man and his unusual path. It’s a bold, funny, smart, brutally frank work filled with the rich anecdotes of a born storyteller.

“You know how most people who write their life story have ghost writers? Well, he wrote his book. Every word,” says his son, Richie Love, with pride and awe.

The ability, with no formal training, to master writing, music and other pursuits was what Billy Melton calls his late friend’s “God-given talents. Preston just picked up everything. He had a photographic memory. He was remarkable.” Richie Love says his father’s huge curiosity and appetite for life was part of “a drive to excel” that came from being the youngest of nine in a poor, single-parent house so run down it was jokingly called the” Love Mansion.” Young Preston taught himself to play the sax, abandoning a promising career in the boxing ring for the bandstand, where the prodigy’s gift for sight reading became his forte. “Any kind of music you put in front of him, he played it,” says former Love pianist Roy Givens.

Whether indulging in food and drink, friends and family, leisure or work, Richie Love says his father lived large. “Everything he did was larger than life. He did everything with a passion. Music. Fishing. Cooking. He was just so interesting. He was an all-around person. People loved him. People flocked to him.”

“He was just a big man all the way around,” says Juanita Morrow, a lifelong friend and fishing companion who experienced his generosity when she and her late husband, Edward, fell ill and Love made frequent visits to their home, bringing them groceries. “I’ll remember him as a very dear friend. He never let my husband and I down. No matter where he went on tour…he always sent letters and pictures.”

Frank McCants, another old chum from back in the day, says even after making it big with Basie that Love “never got the big head. He stayed regular.” Melton says Love would return from the road looking for a good time. “Preston made the big bucks and when he came to town he’d look us up…and that’s when the partying would begin. We let our hair down.” On those rare occasions when the blues overtook Love, Melton says, “music was the antidote. He really loved it.”

Although he hated being apart from his wife Betty, who survives him, Love savored “the itinerant life.” Givens recalls how he made life on tour a little more enjoyable: “He was a very serious musician, but he was a joker. He kept you laughing a lot because of the things he would say and do.” Traveling by bus, the spontaneous Love often heeded the sportsman’s call en route to a gig. “He loved to hunt and he loved to fish,” Givens says, “and on the bus we had he carried his shot gun and his fishing rod. If we went across any water, he’d stop the bus and say, ‘I’m just going to see what I can catch in 15 or 20 minutes.’ He’d throw in a line. When passing by a field, if he’d see a pheasant or a rabbit, he’d stop and shoot at it out the windows. If he hit anything, he’d skin it. If he caught anything, he’d put it on ice in a cooler. A lot of times we were almost late getting to the job because he would be catching fish and he didn’t want to leave. The guys would just laugh.”

A consummate showman, Love burned with stage presence between his insouciant smile and his patter between sets that combined jive, scat and stand up. Richetta Wilson, who sang with various Love bands, recalls his ebullience. “He would talk more than he would play sometimes. He was so funny and talented. The best person you could ever want to work with.” Billy Melton recalls Love teasing audience members from the bandstand. “Almost everybody that came in the door he’d know by name and he’d call them out. He was always joking, but he could take it, too. He didn’t care what you said about him.”

Then there was his serious side. Love coaxed a smooth, sweet, plaintive tone from the sax developed over a lifetime of listening and jamming in joints like McGill’s Blue Room on north 24th Street. As a student of music, he voiced learned, militant diatribes against “the corruption of our music.” As he saw the once serious Omaha jazz scene abandon its indigenous roots, he used his newspaper columns, radio shows and college classrooms as forums for haranguing local purveyors and performers of what he considered pale imitations of the real thing.

Calling much of the white bread jazz presented here “spurious” and “synthetic,” he decried the music’s most authentic interpreters being passed over in favor of less talented, often times white, players. “My people gave this great art form for posterity and I’m not going to watch my people and our music sold down the road,” he said once. “I will fight for my people’s music and its presentation.”

He delivered his eloquent, evangelical musings in free-flowing rants that were equal parts improvisational riff, poetry slam and pulpit preaching, his mellifluous voice rising and falling, quickening and slowing in rhythmic concert with his emotions.

Love’s guardianship for the music may live on if the planned Love Jazz-Cultural Arts Center dedicated to him on 24th Street ever opens, which organizers say could happen by the end of 2004. The center’s driving force, Omaha City Councilman Frank Brown, hopes the facility can showcase the Love legacy, including his many well-reviewed recordings. “I want visitors to know here is a person who was great and touched greatness and was part of that rich jazz history,” Brown says. “People like that just don’t come along every day. And I want kids to walk away with the feeling they too can achieve like he did.” Richie Love says he wants people to know his dad was “a great man.”

Center board members plan displaying items from the mass of memorabilia the late artist collected in his collaborations with what one reviewer of a reissued Love album called a “Who’s Who of American Musicians.” The star-studded roster of artists he worked with ranged from Count Basie, Lucky Millinder and Earl Hines to Wynonie Harris, Billie Holiday and Jimmy Rushing to Aretha Franklin, The Four Tops, The Temptations, The Supremes, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Ray Charles, Marvin Gaye, Issac Hayes and Stevie Wonder.

Richie Love is sorting through the materials, including hundreds of photos, in an effort to decide what the family will donate to the center. Many photos picture Love with the Motown artists he worked with during his decade (1962 to 1972) in California. He moved his family there at the urging of friend Johnny Otis, the blues great with whom he often collaborated. Love worked as an L.A. session player and sideman and, later, as the leader of Motown’s west coast backup band, an ensemble that backed many of the label’s artists performing there.

For Richie, and siblings Norman and Portia, the L.A. years were golden. Richie recalls the high times that ensued whenever his father parked the Motown tour bus outside their rented house on West 29th Place. “The kids from the neighborhood would see that bus and we’d all get on it. I’d sit in the driver’s seat and act like I was driving and they’d be in the back singing like they were Motown. It was just the greatest.” Other times, stars arrived in style at the Love home. “We’d look out the window and see a limo coming and say, ‘Oh-oh, who’s it going to be this time?’ I think Dad liked to surprise us. It was always somebody different.” Some visitors, like Gladys Knight or Jimmy Rushing, became live-in guests, passing the time swapping stories and playing Tonk, a popular card game among blacks. “My brother, sister and I would sit in the front room and watch and listen while they were having a ball, laughing and talking all night. We’d get up in the morning, and they’d still be there.” Then there were the times when the boys accompanied their father to television tapings or live concerts and got to hang backstage with the show’s stars, including Stevie Wonder. “Oh, it was the coolest,” Richie says.

|

Having a dad who’s a kid at heart meant impulsive trips to the beach, swimming pools, fishing holes, music gigs. Sitting up with him all hours of the night as he made “elaborate dinners” – from gourmet to barbecue – and “told these great stories,” Richie says. “He was a great father…he turned us on to so many things in life.”

By all accounts, Love was a good teacher as well. Whether holding court at the Omaha Star, where he was advertising director, or from the bandstand, he shared his expertise. “He helped musicians reach their potential,” says Roy Givens. “After listening to you play, he could tell you what your weaknesses were…He would pull you aside and tell you to work on them. I know he made me a better musician.”

Melton says Love often spoke of a desire “to pass his knowledge on.” To see the results of that teaching, Givens says, one has only to look at Love’s children. “They are all exceptional musicians, and that right there’s an accomplishment.” Richie is an instrumentalist, composer and studio whiz. Norman, who resides in Denver, is widely regarded as an improvisational giant. Portia is a jazz vocalist. All performed with their father on live and recorded gigs.

If nothing else, Preston Love endured. He survived fads and changing musical tastes. He adapted from the big band swing era to the pop, soul, rhythm and blues refrains of Motown. He rose above the neglect and disdain he felt in his own hometown and kept right on playing and speaking his mind. Always, he kept his youthful enthusiasm. The eternal hipster. “I refuse to be an ancient fossil or an anachronism,” Love told an interviewer in 1997. “I am eternally vital. I am energetic, indefatigable. It’s just my credo and the way I am as a person.”

Even into his early 80s, Love could still swing. Omaha percussionist Gary Foster, who played alongside him and produced CDs featuring him, marveled at his skill and vitality. “He had a very pure, soulful sound that just isn’t heard anymore. It’s that Midwestern, Kansas City thing. He was part of that past when it was real — when the music was first coming and new. He had that still.” He says Love was not about “coasting on what he’d done in the past,” adding: “To him, that just wasn’t good enough. He still wanted to produce. He was still hungry. In the studio, he was like, ‘What are we doing today? Where are going to take the music today?’”

Love’s musical chops were such that, at only 22, he earned an audition with Basie during an appearance of the Count’s fabled band at Omaha’s Dreamland Ballroom. In the same room he grew up worshiping at the feet of his musical idol, Basie sax great Earle Warren, Love won a seat in the band as a replacement for none other than the departing Warren. “Preston Love was part of this lineage of great lead alto saxophone players. With Basie, he took over for one of the great lead alto saxophone players…and he performed that role with distinction,” Foster says.

Love once said, “Everything in my life would be an anticlimax because I realized my dream.” That dream was making it to the top with Basie. Luckily for us, he didn’t stop there. Now, he leaves behind a legacy rich in music and in Love.

Related Articles

- Leon Breeden, Jazz Educator, Dies at 88 (nytimes.com)

- International Jazz Day (beliefnet.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Big Bad Buddy Miles (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Once More With Feeling, Loves Jazz & Arts Center Back from Hiatus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Rich Music History Long Untold is Revealed and Celebrated at the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

“Omaha Blues” and “Preston Love’s Omaha Bar-B-Q”: Two scorching instrumental blues journeys by Omaha music Llgend Preston Love

This next story is actually adapted from a press release that the late Omaha jazzman and blues artist, Preston Love Sr., commissioned me to write to help promote a new CD he was releasing. I include it here as another element of putting the arc of his life and career in proper perspective.

“Omaha Blues” and “Preston Love’s Omaha Bar-B-Q’” Two scorching instrumental blues journeys by Omaha music legend Preston Love

©by Leo Adam Biga

Adapted from a press release I wrote for Preston promoting a new CD

At age 80, legendary Omaha jazz and blues musician Preston Love is enjoying the kind of renaissance few artists survive to see. It began with the 1997 publication of his autobiography, A Thousand Honey Creeks Later (Wesleyan University Press), which earned rave reviews in such prestigious pages as the New York Times Book Review. Next, came a steady stream of re-released albums on CD featuring a much younger Love playing in such distinguished company as the Count Basie and Lucky Millinder bands, just two of the classic groups he played with during this indigenous American music’s Heyday.

Now, there is the unlikely release of two albums, produced 30 years apart, each with the name Omaha in them – Omaha Blues and Preston Love’s Omaha Bar-B-Q – and each showcasing Love at his silky smooth lead alto saxophone playing best. Love has always been faithful to his hometown of Omaha where, as a kid, he first got hooked on jazz and blues by hanging on every note performed by his idols at the near northside clubs he later played too. He still makes his home in Omaha, where he lives with his wife Betty.

“What a unique thing to have two albums out with the name Omaha in them and to have them selling like hotcakes all over the country,” Love said. “What a thrill.”

Beyond the rare confluence of Omaha in their titles, the two releases cast an equally rare spotlight on an artist at two different periods in his career as a jazz-blues interpreter. A brand new release, the Omaha Blues CD presents the ever vibrant Love performing the music of his life, including a mix of standards by the likes of Duke Ellington and Count Basie and a selection of original Love tunes, including the soulful title track.

Produced by Gary Foster at Omaha’s Ware House Productions studio and distributed by North Country Distributors, Omaha Blues has received high praise from what is commonly referred to as The Bible of jazz and blues magazines for the way Love and his band perform everything from slow ballads to hot swinging numbers. Special praise is reserved for Love’s music-making.

Gregg Ottinger, a reviewer with Jazz Ambassador Magazine in Kansas City, writes that the ensemble heard on the record “is particularly good and provides an excellent surrounding for Mr. Love’s strong sound. But the highlight of the CD is Mr. Love’s playing. This is a man who is full of music – eight decades of it – and it’s still strong and fresh. It’s a joy to hear it released on this recording.” Jack Sohmer in Jazz Times describes Love as “still a masterly saxophonist,” adding, “The proof is here that Love has not lost a beat…” And Robert Spencer in Cadence writes, “Preston Love has a slippery, slithery tone that slides through the blues real easy and rings all the changes on a dime with a fine exuberance. Preston Love plays this music with superlative commitment and yes, love. Great fun.”

Producer Gary Foster, the drummer on this recording and a regular percussionist with Love’s working band, said he was drawn to the project because it provided an opportunity to bring the man he considers his mentor to the forefront, a position unfamiliar to this venerable artist who for decades toiled in relative obscurity as a highly respected if not starring sideman, session musician, contractor and band leader.

Also a flutist, Love was a fixture in the reed section of many bands and made a name for himself with his ability to sight read. In addition to playing with Basie and Millinder, he headed-up his own territory bands and led Motown’s west coast band.

“I’m really happy I was able to present Preston Love just doing what he does best and doing it as well as he can. I think in the past Preston deferred to what producers wanted and a lot of times he ended up in the background,” said Foster, who refers to Love’s many studio and live collaborations with legendary artists — ranging from Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin to longtime friend and rhythm and blues great Johnny Otis. During these gigs, Love almost always played a supporting role. But, as Foster and others see it, Love is more than deserving of his own limelight because he is a consummate artist in his own right and the genuine article to boot.

“Preston Love is part of this lineage of great lead alto saxophone players. With Basie, he took over for one of the great lead alto saxophone players — Earl Warren — and he performed that role with distinction. He did a great job,” Foster said.

The way Foster sees it, Love is still making sweet sounds some half-a-century later. “He’s got a very pure, soulful sound that just isn’t heard anymore. It’s that Midwestern, Kansas City thing. He’s part of that past when it was real — when the music was first coming and new. He’s got that still.” Despite the fact Foster has played alongside Love for years he is still amazed that a man of his age remains as sharp and vital and curious as he is. “I’m half his age and I watch this guy night after night constantly trying to improve himself. He’s 80 years old and he’s still worried about being good enough. He’s never satisfied. It’s an inspiration. That’s what I aspire to be as an artist — just constantly trying to be better.”

Foster said Love is not about “coasting on what he’s done in the past,” adding: “To him, that’s just not good enough. He still wants to produce. He’s still hungry. In the studio, he’s like, ‘What are we doing today? Where are going to take the music today?’”

The idea of resting on his laurels is anathema to Love, who dismisses the notion he is some “moldy fig” or stick in the mud. Indeed, Love feels his playing has never been better. “I reached my peak on my instruments later in life,” he said. “I wasn’t interested that much in a career as a soloist early on, but as I became more interested in that I was able to accomplish more at a time in life when most guys deteriorate. I refuse to be an ancient fossil or an anachronism. I am eternally vital. I am energetic, indefatigable. It’s just my credo and the way I am. I play my instruments as modern as anybody alive and better than I’ve ever played them. It’s helped that my health has been good too.”

For Love, Omaha Blues was a blast to make because he was working with his longtime band members Orville Johnson (piano), Nate Mickels (bass) and Foster (drums), along with his daughter Portia Love, an assured vocalist and frequent collaborator. Also heard on the disc are guitarist Jon Hudenstein, pianist Bill Erickson, bassist John Kotchain and vocalist Ansar Muhammad. Of his fellow musicians, Love said, “The guys are just miraculous on this. We didn’t get technical or anything. We just banged it out and I think we did a good job.” Love also lends his smoky voice to a few tunes.

Originally produced on Kent Records and now being re-released by Ace Records of Great Britain, Preston Love’s Omaha Bar-B-Q represents Love at a time and place in his career when he was working with some of the music industry’s strongest talents. “These were top players and all dear friends of mine. I hired them a lot for the Motown band,” Love said. “We had James Brown’s drummer and Ike and Tina Turner’s sax player. We had my dear friend Johnny Otis, who produced the album. Johnny also brought in his son, Shuggie, then a 15 year-old prodigy on the guitar.”

The recording features several different artists, but most notably Shuggie, now enjoying a revival of his own. “He played the greatest blues solos on guitar on that album that will ever be done,” Love said. “He’s a genius.” In keeping with the album’s Omaha and eating themes, the tracks feature a number of Love-penned tunes named after favorite soul food staples, including Chitlin Blues. Released in 1970, the album fared well in Europe, where, Love said, “it made me a pretty big name.” The musician has performed in Europe several times and he is preparing to play France later this year.

Not only a performing and recording artist, Love is also a noted jazz-blues columnist and historian. For years, he hosted a popular jazz program on local public radio, a forum he used as a combination stage, classroom and pulpit in presenting classic jazz in its proper aesthetic-cultural-historical context. He is clearly not done making his passionate, sometimes prickly voice heard either. From his brand new CD to classic reissues of old LPs to area gigs his band plays, his music-making continues enthralling and enchanting old and new listeners alike. With his first book, A Thousand Honey Creeks Later, now going into its second printing, Love is already planning to write another book on his eventful life inside and outside music.

NOTES: After a highly successful run at L & N Seafood in One Pacific Place, Preston Love and his band now jam Friday and Saturday nights at Tamam, 1009 Farnam-on-the-Mall, an Old Market restaurant specializing in Middle Eastern cuisine;

Love was recently a featured performer at the August 3 Blues, Jazz and Gospel Festival on the Metropolitan Community College Fort Omaha campus; Omaha Blues can be found at area record and music stores, including Homer’s. Preston Love’s Omaha Bar-B-Q will soon be available.

Related Articles

- Harlem Jazz Museum Acquires Trove By Greats (harlemworldblog.wordpress.com)

- National Jazz Museum Acquires Savory Collection (nytimes.com)

- He Keeps Discovering Who He Is (online.wsj.com)

- Gene Conners obituary (guardian.co.uk)

- Omaha Arts-Culture Scene All Grown Up and Looking Fabulous (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Tyler Owen – Man of MAHA (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Once More With Feeling, Loves Jazz & Arts Center Back from Hiatus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Big Bad Buddy Miles (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Rich Music History Long Untold is Revealed and Celebrated at the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Preston Love: His voice will not be stilled

This is one of those foundational stories I did on Omaha jazz and blues legend Preston Love. Together with my other stories on him I give you a good sense for who this passionate man was and what he was about. The piece originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). I should mention that Love’s autobiography, which is referenced in the story, was well-reviewed by the New York Times and other major national publications. Preston always wanted to leave a legacy behind, and his book, “A Thousand Honey Creeks Later,” is a fine one. The very cool Loves Jazz & Arts Center in the heart of North Omaha’s historic jazz district is named in honor of him. More stories by me about Preston Love can be found on this blog site. I also feature a profile I did on his daughter, singer-songwriter-guitarist Laura Love.

Preston Love: His voice will not be stilled

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader

One name in Omaha is synonymous with traditional jazz and blues — Preston Love Sr., the native son musician most famous for playing lead alto saxophone with the legendary Count Basie in the 1940s.

The ebullient Love, still a mean sax player at 75, fiercely champions jazz and blues as rich, expressive, singularly African-American art forms and cultural inheritances. This direct inheritor and accomplished interpreter of the music feels bound to preserve it, to protect its faithful presentation and to rail against its misrepresentation.

He has long been an outspoken critic of others appropriating the music from its black roots and reinventing it as something it’s not. Over the years he’s voiced his opinion on this and many other topics as a performer, columnist, radio host, lecturer and oft-quoted music authority. Since 1972 his Omaha World-Herald “Love Notes” column has offered candid insights into the art and business sides of music.

From 1971 until early 1996 he hosted radio programs devoted to jazz. The most recent aired on KIOS-FM, whose general manager, Will Perry, describes Love’s on-air persona: “He was fearless. He was not afraid to give his opinion, especially about what he felt was the inequality black musicians have endured in Omaha, and how black music has been taken over by white promoters and artists. Some listeners got really angry.”

With the scheduled fall publication of his autobiography “A Thousand Honey Creeks Later,” by Wesleyan University Press in Middletown, Conn., he will finally have a forum large enough to contain his fervor.

“It’s written in protest,” Love said during a recent interview at the Omaha Star, where he’s advertising manager. “I’m an angry man. I started my autobiography to a large degree in dissatisfaction with what has transpired in America in the music business and, of course, with the racial thing that’s still very prevalent. Blacks have almost been eliminated from their own art because the people presenting it know nothing about it. We’ve seen our jazz become nonexistent. Suddenly, the image no longer is black. Nearly all the people playing rhythm and blues, blues and jazz in Omaha are white. That’s unreal. False. Fraudulent.

“They’re passing it off as something it isn’t. It’s spurious jazz. Synthetic. Third-rate. Others are going to play our music, and in many cases play it very well. We don’t own any exclusivity on it. But it’s still black music, and all the great styles, all the great developments, have been black, whether they want to admit it or not. So why shouldn’t we protect our art?”

When Love gets on a roll like this, his intense speaking style belongs both to the bandstand and the pulpit. His dulcet voice carries the rhythmic inflection and intonation of an improvisational riff and the bravura of an evangelical sermon, rising in a brimstone tirade one moment and falling to a confessional whisper the next. Suzanna Tamminen, acting director of Wesleyan University Press, says, “One of the wonderful things about Preston’s book is that it’s really like listening to him talk. A lot of other publishers had asked him to cut parts out, but he felt he had things to say and didn’t want to have to change a lot of that. So we’ve tried to have his voice come through, and I think it does.”

Love pours out his discontent over what’s happened to the music in the second half of the book. Love, who’s taught courses at the University of Nebraska at Omaha on the history of jazz and the social implications of black music, says he “most certainly” sees himself as a teacher and his book as an educational document.

In his introduction to the book, George Lipsitz, an ethnic historian at the University of California-San Diego and a Wesleyan contributing editor, compares Love to the elders of the Yoruba people in West Africa” “According to tradition, elders among the Yoruba…teach younger generations how to make music, to dance, and create visual art, because they believe that artistic activity teaches us how to recognize ‘significant’ communications. Preston Love…is a man who has used the tools open to him to make great dreams come true, to experience things that others might have considered beyond his grasp.

“He is a writer who comes to us in the style of the Yoruba elders, as someone who has learned to discern the significance in things that have happened to him, and who is willing to pass along his gift, and his vision to the rest of us. His dramatic, humorous and compelling story is significant because it uses the lessons of the past to prepare is for the struggle of the future. It is up to us to pay attention and learn from his wisdom.”

Some may disagree with Love’s views, but as KIOS Perry points out, “All they can do is argue from books. None of them were there. None of them have gone through what’s he gone through. They have nothing to compare it with.” Perry says Love brings a first-hand “historical perspective” to the subject that cannot be easily dismissed.

Those who share Love’s experience and knowledge, including rhythm and blues great and longtime friend, Johnny Otis, agree with him. “Those of us who came though an earlier era are dismayed,” Otis said by phone from his home in Sebastopol, Calif., “because things have regressed artistically in our field. Preston is constantly trying to make young people understand, so they’ll do a little investigation and get more artistry in their entertainment. He’s dedicated to getting that message out.”

But Love’s book is far more than a polemic. It’s a remarkable life story whose sheer dramatic arc is daunting. It traces his deep kinship with jazz all the way back to his childhood, when his self-described “fanaticism” developed, when he haunted then flourishing North 24th Street’s popular jazz joints to glimpse the music legends who played there.

He grew up the youngest of nine in a ramshackle house in North Omaha. Love’s mother, Mexie, was widowed when he was an infant. Music was always part of his growing up. He listened to his music idols, especially Count Basie and Basie’s lead alto sax man, Earle Warren on the family radio and phonograph. He taught himself to play the sax brought home by his brother “Dude.” He learned, verbatim, Warren’s solos by listening to recordings over and over again. By his med-teens he was touring with pre-war territory bands, playing his first professional gig in 1936 at the Aeroplane Inn in Honey Creek, Iowa (hence the title of his book).

At Omaha’s Dreamland Ballroom he saw his idols in person, imagining himself on the bandstand too — hair coiffured and suit pressed — the very embodiment of black success. “We’d go to see the glamour of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. We aspired to escape the drabness and anonymity of our own town by going into show business,” Love recalls. “I dreamed of someday making it…of going to New York to play the Cotton Club and of playing the Grand Terrace in Chicago.”

He encountered both racism and kindness touring America. The road suited him and his wife Betty, whom he married in 1941.

The couple’s first child, Preston Jr., was born 54 years ago and the family grew to include three more off-spring: Norman and Richie, who are musicians, and Portia, who sings with her father’s band.